This monograph demonstrates

1) that the sacred symbol 'svastika' is traceable to Sarasvati Civilization of the Bronze Age 3rd millennium BCE attesting the production and use of zinc mineral to create metal alloys such as brass; and

2) that the svastika as Indus Script hypertext signifies a distinct composition in metalwork wealth-accounting ledgers

About 50 seals of Indus Script Corpora signify right-handed and left-handed svastika hypertexts.

In Kota language: kole.l 'smithy' is rebus kole.l 'temple'. This monograph demonstrates that the svastika hypertext is held sacred because of the association of kole.l 'smithy' with kole.l 'temple'. The word kole.l 'temple' explains the use of the hieroglyph kol 'tiger' in svastika associated indus script inscriptions.

In the historical periods, starting from ca. 3rd cent. BCE, some hieroglyphs of Indus Script get venerated as sacred symbols. This cultural phenomenon is explained by the occurrence -- in Jaina Ananta gumpha of Khandagiri caves -- of svastika hieroglyph together with 'lathe/furnace standard device' and 'mollusc' component in hieroglyph-multiplex variously designated by art historians as s'rivatsa/nandipada /triratna. Why did Indus script hieroglyphs -- e.g., svastika, portable furnace, pair of fish, fish tied to a pair of molluscs, safflower, pair of fish, fish tail -- get venerated as sacred symbols, displayed on homage tablets, say, on the Jaina AyagapaTTa अयागपट्ट of Kankali Tila, Mathura, ca. 1st or 3rd century BCE?

Khandagiri caves (2nd cent. BCE) Cave 3 (Jaina Ananta gumpha). Fire-altar?, śrivatsa, svastika (hieroglyphs) (King Kharavela, a Jaina who ruled Kalinga has an inscription dated 161 BCE) contemporaneous with Bharhut and Sanchi and early Bodhgaya.

Evolution of śrivatsa symbol variants

śrivatsa symbol [with its hundreds of stylized variants, depicted on Pl. 29 to 32] occurs in Bogazkoi (Central Anatolia) dated ca. 6th to 14th cent. BCE on inscriptions Pl. 33, Nandipāda-Triratna at: Bhimbetka, Sanchi, Sarnath and Mathura] Pl. 27, Svastika symbol: distribution in cultural periods] The association of śrivatsa with ‘fish’ is reinforced by the symbols binding fish in Jaina āyāgapaṭas (snake-hood?) of Mathura (late 1st cent. BCE). śrivatsa symbol seems to have evolved from a stylied glyph showing ‘two fishes’. In the Sanchi stupa, the fish-tails of two fishes are combined to flank the ‘śrivatsa’ glyph. In a Jaina āyāgapaṭa, a fish is ligatured within the śrivatsa glyph, emphasizing the association of the ‘fish’ glyph with śrivatsa glyph.

śrivatsa orthography evolves from a pair of fish-fins. khambhaṛā 'fish fin' rebus: kammata 'mint' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.Thus, alloy metalcasting mint.

(After Plates in: Savita Sharma, 1990, Early Indian symbols, numismatic evidence, Delhi, Agama Kala Prakashan; cf. Shah, UP., 1975, Aspects of Jain Art and Architecture, p.77)

Kushana period, 1st century C.E.From Mathura Red Sandstone 89x92cm

books.google.com/books?id=evtIAQAAIAAJ&q=In+the+image...

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.uddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet." http://www.cristoraul.com/ENGLISH/readinghall/UniversalHistory/INDIA/Cambridge/I/CHAPTER_XXVI.html

Vishnu Sandstone Relief From Meerut India Indian Civilization 10th Century Dharma chakra. Srivatsa. Gada.Rebus: dhamma 'dharma' (Pali) Hieroglyphs: dām 'garland, rope':Hieroglyphs: hangi 'mollusc' + dām 'rope, garland' dã̄u m. ʻtyingʼ; puci 'tail' Rebus: puja 'worship'

Rebus: ariya sanghika dhamma puja 'veneration of arya sangha dharma'

![]() Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

ayira 'fish' Rebus:ayira, ariya, 'person of noble character'. युगल yugala 'twin' Rebus: जुळणें (p. 323) [ juḷaṇēṃ ] v c & i (युगल S through जुंवळ ) To put together in harmonious connection or orderly disposition (Marathi). Thus an arya with orderly disposition.

sathiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus: Sacca (adj.) [cp. Sk. satya] real, true D i.182; M ii.169; iii.207; Dh 408; nt. saccaŋ truly, verily, certainly Miln 120; saccaŋ kira is it really true? D i.113; Vin i.45, 60; J (Pali)

सांगाडा [ sāṅgāḍā ] m The skeleton, box, or frame (of a building, boat, the body &c.), the hull, shell, compages. 2 Applied, as Hulk is, to any animal or thing huge and unwieldy.सांगाडी [ sāṅgāḍī ] f The machine within which a turner confines and steadies the piece he has to turn. Rebus: सांगाती [ sāṅgātī ] a (Better संगती ) A companion, associate, fellow.![]() Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

uddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet." http://www.cristoraul.com/ENGLISH/readinghall/UniversalHistory/INDIA/Cambridge/I/CHAPTER_XXVI.html

Vishnu Sandstone Relief From Meerut India Indian Civilization 10th Century Dharma chakra. Srivatsa. Gada.

Rebus: dhamma 'dharma' (Pali) Hieroglyphs: dām 'garland, rope':

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.sathiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus: Sacca (adj.) [cp. Sk. satya] real, true D i.182; M ii.169; iii.207; Dh 408; nt. saccaŋ truly, verily, certainly Miln 120; saccaŋ kira is it really true? D i.113; Vin i.45, 60; J (Pali)

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html

Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

Ayagapata (After Huntington)

Jain votive tablet from Mathurå. From Czuma 1985, catalogue number 3. Fish-tail is the hieroglyph together with svastika hieroglyph, fish-pair hieroglyph, safflower hieroglyph, cord (tying together molluscs and arrow?)hieroglyph multiplex, lathe multiplex (the standard device shown generally in front of a one-horned young bull on Indus Script corpora), flower bud (lotus) ligatured to the fish-tail. All these are venerating hieroglyphs surrounding the Tirthankara in the central medallion.

Pali etyma point to the use of 卐 with semant. 'auspicious mark'; on the Sanchi stupa; the cognate gloss is: sotthika, sotthiya 'blessed'.

Or. ṭaü ʻ zinc, pewter ʼ(CDIAL 5992). jasta 'zinc' (Hindi) sathya, satva 'zinc' (Kannada) The hieroglyph used on Indus writing consists of two forms: 卐卍. Considering the phonetic variant of Hindi gloss, it has been suggested for decipherment of Meluhha hieroglyphs in archaeometallurgical context that the early forms for both the hieroglyph and the rebus reading was: satya.

The semant. expansion relating the hieroglyph to 'welfare' may be related to the resulting alloy of brass achieved by alloying zinc with copper. The brass alloy shines like gold and was a metal of significant value, as significant as the tin (cassiterite) mineral, another alloying metal which was tin-bronze in great demand during the Bronze Age in view of the scarcity of naturally occurring copper+arsenic or arsenical bronze.

I suggest that the Meluhha gloss was a phonetic variant recorded in Pali etyma: sotthiya. This gloss was represented on Sanchi stupa inscription and also on Jaina ayagapata offerings by worshippers of ariya, ayira dhamma, by the same hieroglyph (either clockwise-twisting or anti-clockwise twisting rotatory symbol of svastika). Linguists may like to pursue this line further to suggest the semant. evolution of the hieroglyph over time, from the days of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization to the narratives of Sanchi stupa or Ayagapata of Kankali Tila.

स्वस्ति [ svasti ] ind S A particle of benediction. Ex.राजा तुला स्वस्ति असो O king! may it be well with thee!; रामाय स्वस्ति रावणाय स्वस्ति ! 2 An auspicious particle. 3 A term of sanction or approbation (so be it, amen &c.) 4 Used as s n Welfare, weal, happiness.स्वस्तिक [ svastika ] n m S A mystical figure the inscription of which upon any person or thing is considered to be lucky. It is, amongst the जैन , the emblem of the seventh deified teacher of the present era. It consists of 卍. 2 A temple of a particular form with a portico in front. 3 Any auspicious or lucky object.(Marathi)

svasti f. ʻ good fortune ʼ RV. [su -- 2 , √as 1 ]Pa. suvatthi -- , sotthi -- f. ʻ well -- being ʼ, NiDoc. śvasti; Pk. satthi -- , sotthi -- f. ʻ blessing, welfare ʼ; Si. seta ʻ good fortune ʼ < *soti (H. Smith EGS 185 < sustha -- ). svastika ʻ *auspicious ʼ, m. ʻ auspicious mark ʼ R. [svastí -- ]Pa. sotthika -- , °iya -- ʻ auspicious ʼ; Pk. satthia -- , sot° m. ʻ auspicious mark ʼ; H. sathiyā, sati° m. ʻ mystical mark of good luck ʼ; G. sāthiyɔ m. ʻ auspicious mark painted on the front of a house ʼ.(CDIAL 13915, 13916)

iii. 38=iv. 266 ("brings future happiness"); J i. 335; s. hotu hail! D i. 96; sotthiŋ in safety, safely Dh 219 (=anupaddavena DhA iii. 293); Pv iv. 64 (=nirupaddava PvA 262); Sn 269; sotthinā safely, prosperously D i. 72, 96; ii. 346; M i. 135; J ii. 87; iii. 201. suvatthi the same J iv. 32. See sotthika & sovatthika. -- kamma a blessing J i. 343. -- kāra an utterer of blessings, a herald J vi. 43. -- gata safe wandering, prosperous journey Mhvs 8, 10; sotthigamana the same J i. 272. -- bhāva well -- being, prosperity, safety J i. 209; iii. 44; DhA ii. 58; PvA 250. -- vācaka utterer of blessings, a herald Miln 359. -- sālā a hospital Mhvs 10, 101.Sotthika (& ˚iya) (adj.) [fr. sotthi] happy, auspicious, blessed, safe VvA 95; DhA ii. 227 (˚iya; in phrase dīgha˚ one who is happy for long [?]).Sotthivant (adj.) [sotthi+vant] lucky, happy, safe Vv 8452 .Sovatthika (adj.) [either fr. sotthi with diaeresis, or fr. su+atthi+ka=Sk. svastika] safe M i. 117; Vv 187 (=sotthika VvA 95); J vi. 339 (in the shape of a svastika?); Pv iv. 33 (=sotthi -- bhāva -- vāha PvA 250). -- âlankāra a kind of auspicious mark J vi. 488. (Pali)

...

[quote]Cunningham, later the first director of the Archaeological Survey of India, makes the claim in: The Bhilsa Topes (1854). Cunningham, surveyed the great stupa complex at Sanchi in 1851, where he famously found caskets of relics labelled 'Sāriputta' and 'Mahā Mogallāna'. [1] The Bhilsa Topes records the features, contents, artwork and inscriptions found in and around these stupas. All of the inscriptions he records are in Brāhmī script. What he says, in a note on p.18, is: "The swasti of Sanskrit is the suti of Pali; the mystic cross, or swastika is only a monogrammatic symbol formed by the combination of the two syllables, su + ti = suti." There are two problems with this. While there is a word suti in Pali it is equivalent to Sanskrit śruti'hearing'. The Pali equivalent ofsvasti is sotthi; and svastika is either sotthiya or sotthika. Cunningham is simply mistaken about this. The two letters su + ti in Brāhmī script are not much like thesvastika. This can easily been seen in the accompanying image on the right, where I have written the word in the Brāhmī script. I've included the Sanskrit and Pali words for comparison. Cunningham's imagination has run away with him. Below are two examples of donation inscriptions from the south gate of the Sanchi stupa complex taken from Cunningham's book (plate XLX, p.449).

![]()

"Note that both begin with a lucky svastika. The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions...Müller [in Schliemann(2), p.346-7] notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.[unquote]

1. Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

2. Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

http://jayarava.blogspot.in/2011/05/svastika.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/deciphering-indus-script-meluhha.html

The semant. expansion relating the hieroglyph to 'welfare' may be related to the resulting alloy of brass achieved by alloying zinc with copper. The brass alloy shines like gold and was a metal of significant value, as significant as the tin (cassiterite) mineral, another alloying metal which was tin-bronze in great demand during the Bronze Age in view of the scarcity of naturally occurring copper+arsenic or arsenical bronze.

I suggest that the Meluhha gloss was a phonetic variant recorded in Pali etyma: sotthiya. This gloss was represented on Sanchi stupa inscription and also on Jaina ayagapata offerings by worshippers of ariya, ayira dhamma, by the same hieroglyph (either clockwise-twisting or anti-clockwise twisting rotatory symbol of svastika). Linguists may like to pursue this line further to suggest the semant. evolution of the hieroglyph over time, from the days of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization to the narratives of Sanchi stupa or Ayagapata of Kankali Tila.

स्वस्ति [ svasti ] ind S A particle of benediction. Ex.

svasti f. ʻ good fortune ʼ RV. [

Nibbānasotthi (welfare). saccena suvatthi hotu nibbānaŋ Sn 235.Sotthi (f.) [Sk. svasti=su+asti] well -- being, safety, bless ing A...

[quote]Cunningham, later the first director of the Archaeological Survey of India, makes the claim in: The Bhilsa Topes (1854). Cunningham, surveyed the great stupa complex at Sanchi in 1851, where he famously found caskets of relics labelled 'Sāriputta' and 'Mahā Mogallāna'. [1] The Bhilsa Topes records the features, contents, artwork and inscriptions found in and around these stupas. All of the inscriptions he records are in Brāhmī script. What he says, in a note on p.18, is: "The swasti of Sanskrit is the suti of Pali; the mystic cross, or swastika is only a monogrammatic symbol formed by the combination of the two syllables, su + ti = suti." There are two problems with this. While there is a word suti in Pali it is equivalent to Sanskrit śruti'hearing'. The Pali equivalent ofsvasti is sotthi; and svastika is either sotthiya or sotthika. Cunningham is simply mistaken about this. The two letters su + ti in Brāhmī script are not much like thesvastika. This can easily been seen in the accompanying image on the right, where I have written the word in the Brāhmī script. I've included the Sanskrit and Pali words for comparison. Cunningham's imagination has run away with him. Below are two examples of donation inscriptions from the south gate of the Sanchi stupa complex taken from Cunningham's book (plate XLX, p.449).

"Note that both begin with a lucky svastika. The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions...Müller [in Schliemann(2), p.346-7] notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.[unquote]

1. Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

2. Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

http://jayarava.blogspot.in/2011/05/svastika.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/deciphering-indus-script-meluhha.html

Views of Koenraad Elst and Carl Sagan on Svastika symbol

"Koenraad Elst points out that swastika had been a fairly prevalent symbol of the pre-Christian Europe and remained pretty much in vogue even until the 20th century. British troops preparing to help Finland in the war of winter 1939-40 against Soviet aggression painted swastikas, then a common Finnish symbol, on their airplanes. It was also a symbol of Austrian and German völkisch subculture where it was associated with the celebration of the summer solstice. In 1919, the dentist Friedrich Krohn adopted it as the symbol of the DAP because it was understood as the symbol of the Nordic culture. Hitler adopted a variant of the DAP symbol and added the three color scheme of the Second Reich to rival the Communist hammer and sickle as a psychological weapon of propaganda (Elst, Koenraad: The Saffron Swastika, Volume 1, pp. 31-32)...Besides pre-Christian and Christian Europe, the swastika has been depicted across many ancient cultures over several millennia. Carl Sagan infers that it was inspired by the sightings of comets by the ancients. In India, it was marked on doorsteps as it was believed to bring good fortune. It was prevalent worldwide by the second millennium as Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, found. It was depicted in Buddhist caverns in Afghanistan. Jaina, who emphasize on avoidance of harm, have considered it a sign of benediction. The indigenous peoples of North America depicted it in their pottery, blankets, and beadwork. It was widely used in Hellenic Europe and Brazil. One also finds depictions of the swastika, turning both ways, from the seals of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) dating back to 2,500 BCE, as well as on coins in the 6th century BCE Greece (Sagan, Carl and Druyan, Ann: Comet, pp. 181-186)" loc.cit.: http://indiafacts.co.in/the-swastika-is-not-a-symbol-of-hatred/

"Koenraad Elst points out that swastika had been a fairly prevalent symbol of the pre-Christian Europe and remained pretty much in vogue even until the 20th century. British troops preparing to help Finland in the war of winter 1939-40 against Soviet aggression painted swastikas, then a common Finnish symbol, on their airplanes. It was also a symbol of Austrian and German völkisch subculture where it was associated with the celebration of the summer solstice. In 1919, the dentist Friedrich Krohn adopted it as the symbol of the DAP because it was understood as the symbol of the Nordic culture. Hitler adopted a variant of the DAP symbol and added the three color scheme of the Second Reich to rival the Communist hammer and sickle as a psychological weapon of propaganda (Elst, Koenraad: The Saffron Swastika, Volume 1, pp. 31-32)...Besides pre-Christian and Christian Europe, the swastika has been depicted across many ancient cultures over several millennia. Carl Sagan infers that it was inspired by the sightings of comets by the ancients. In India, it was marked on doorsteps as it was believed to bring good fortune. It was prevalent worldwide by the second millennium as Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, found. It was depicted in Buddhist caverns in Afghanistan. Jaina, who emphasize on avoidance of harm, have considered it a sign of benediction. The indigenous peoples of North America depicted it in their pottery, blankets, and beadwork. It was widely used in Hellenic Europe and Brazil. One also finds depictions of the swastika, turning both ways, from the seals of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) dating back to 2,500 BCE, as well as on coins in the 6th century BCE Greece (Sagan, Carl and Druyan, Ann: Comet, pp. 181-186)" loc.cit.: http://indiafacts.co.in/the-swastika-is-not-a-symbol-of-hatred/

Indus script hieroglyphs which signified products and resources of a smithy (e.g., minerals, metals, alloys, smelters, furnaces, supercargo) also signified the cosmic phenomenon held in awe by the Bharatam Janam, metlcaster folk that mere dhatu 'minerals or earth stones or sand' could upon smelting yield metal implements, and weapons. The operations in a smithy/forge became a representation of a cosmic dance. Hence, kole.l signified both a smithy and a temple.

"Spelter, while sometimes used merely as a synonym for zinc, is often used to identify a zinc alloy. In this sense it might be an alloy of equal parts copper and zinc, i.e. a brass, used for hard soldering and brazing, or as an alloy, containing lead, that is used instead of bronze."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spelter zastas 'spelter or sphalerite or sulphate of zinc.' Zinc occurs in sphalerite, or sulphate of zinc in five colours.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spelter zastas 'spelter or sphalerite or sulphate of zinc.' Zinc occurs in sphalerite, or sulphate of zinc in five colours.

Sphalerite or zinc sulfide

Its color is usually yellow, brown, or gray to gray-black, and it may be shiny or dull. Itsluster is adamantine, resinous to submetallic for high iron varieties. It has a yellow or light brown streak, a Mohs hardness of 3.5–4, and a specific gravity of 3.9–4.1. Some specimens have a red iridescence within the gray-black crystals; these are called "ruby sphalerite." The pale yellow and red varieties have very little iron and are translucent. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sphalerite

Svastika signifies zinc metal, spelter. This validates Thomas Wilson's indication --after a wide-ranging survey of migrations of the hieroglyph across Eurasia and across continents -- that svastika symbol connoted a commodity, apart from its being a hieroglyph, a sacred symbol in many cultures.

Two Samarra bowls are metalwork catalogues:

The Samarra bowl, at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction. The civilization flourished alongside the Ubaid period, as one of the first town states in the Near East. It lasted from 5,500 BCE and eventually collapsed in 3,900 BCE.

The Samarra bowl, at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction. The civilization flourished alongside the Ubaid period, as one of the first town states in the Near East. It lasted from 5,500 BCE and eventually collapsed in 3,900 BCE.Eight fish, four peacocks holding four fish, slanting strokes surround. Decipherment: ayo ‘fish’; rebus: ayas ‘metal’

satthiya ‘svastika glyph’; rebus: satthiya ‘zinc’, jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri), satva, ‘zinc’ (Pkt.)

mora peacock; morā ‘peafowl’ (Hindi); rebus: morakkhaka loha, a kind of copper, grouped with pisācaloha (Pali). moraka "a kind of steel" (Sanskrit)

gaṇḍa set of four (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali)

मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻbraid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ (CDIAL 10312). Rebus: mē̃ḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.) meṛha M. meṛhi F.’twisted, crumpled, as a horn’; meṛha deren ‘a crumpled horn’ (Santali) मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl.

Samarra, Iraq, circa 5000 bce. Six women, curl in hair, six scorpions. This Samarra bowl also signifies Indus Script hypertexts. bicha 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'; bicha, bichā ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) sambr.o bica = gold ore (Mundarica) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)

Samarra, Iraq, circa 5000 bce. Six women, curl in hair, six scorpions. This Samarra bowl also signifies Indus Script hypertexts. bicha 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'; bicha, bichā ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) sambr.o bica = gold ore (Mundarica) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)bhaṭa ‘six ’; rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. kola ‘woman’; rebus: kol ‘iron’. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); kollë ‘blacksmith’ (Koḍ)

The petroglyph with swastikas, Gegham mountains, Armenia (Tokhatyan, K.S. "Rock Carvings of Armenia, Fundamental Armenology, v. 2, 2015, pp. 1-22". Institute of History of NAS RA.)

The petroglyph with swastikas, Gegham mountains, Armenia (Tokhatyan, K.S. "Rock Carvings of Armenia, Fundamental Armenology, v. 2, 2015, pp. 1-22". Institute of History of NAS RA.) Greek helmet with swastika marks on the top part (circled), 350–325 BCE from Taranto, found at Herculanum. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris.

Greek helmet with swastika marks on the top part (circled), 350–325 BCE from Taranto, found at Herculanum. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris.

Khachkar with swastikas Sanahin, Armenia. "In Armenia the swastika is called the "arevakhach" and "kerkhach" (Armenian: կեռխաչ) and is the ancient symbol of eternity and eternal light (i.e. God). Swastikas in Armenia were founded on petroglyphs from the copper age, predating the Bronze Age. During the Bronze Age it was depicted on cauldrons, belts, medallions and other items. Among the oldest petroglyphs is the seventh letter of the Armenian alphabet – "E" (which means "is" or "to be") – depicted as a half-swastika. Swastikas can also be seen on early Medieval churches and fortresses,

including the principal tower in Armenia's historical capital city of Ani.The same symbol can be found on

Hands of Svarog (Polish: Ręce Swaroga) with swastikas; Thunder Cross or Cross of Perun, clockwise and counterclockwise (Grzegorzewic, Ziemisław (2016). O Bogach i ludziach. Praktyka i teoria Rodzimowierstwa Słowiańskiego [About the Gods and people. Practice and theory of Slavic Heathenism] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Stowarzyszenie "Kołomir". p. 57)

Hands of Svarog (Polish: Ręce Swaroga) with swastikas; Thunder Cross or Cross of Perun, clockwise and counterclockwise (Grzegorzewic, Ziemisław (2016). O Bogach i ludziach. Praktyka i teoria Rodzimowierstwa Słowiańskiego [About the Gods and people. Practice and theory of Slavic Heathenism] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Stowarzyszenie "Kołomir". p. 57)Detail of Astrology Manuscript, ink on silk, BCE 2th century, Han, unearthed from Mawangdui tomb 3rd, Chansha, Hunan Province, China.

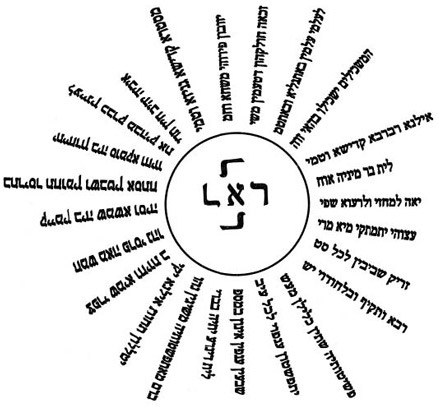

A svastika composed of Hebrew letters as a mystical symbol from the Jewish Kabbalistic work "Parashat Eliezer"

A svastika composed of Hebrew letters as a mystical symbol from the Jewish Kabbalistic work "Parashat Eliezer" Mongolian shamanism"Khas" symbol. The use of the swastika by the Bön faith of Tibet, as well as Chinese Taoism, can also be traced to Buddhist influence. In Thailand, the word Sawaddi is normally used as a greeting that simply means "hello"; Sawaddi-ka (feminine) and Sawaddi-krup (masculine).

Mongolian shamanism"Khas" symbol. The use of the swastika by the Bön faith of Tibet, as well as Chinese Taoism, can also be traced to Buddhist influence. In Thailand, the word Sawaddi is normally used as a greeting that simply means "hello"; Sawaddi-ka (feminine) and Sawaddi-krup (masculine).The magnum opus by Thomas Wilson, Curator, Department of Prehistoric Anthropology, U.S. National Museum. reviewed the history of this glyph and concluded that it represented an object. This work is unsurpassed in the history of anthropological and prehistoric studies. He conclusively demonstrates that the 'symbol' is relatable to the Bronze Age. Wilson concludes that the symbol in ancient times, in Eurasia, signified a commodity.

Wilson, Thomas, 1896, The swastika, the earliest known symbol, and its migrations : with observations on the migration of certain industries in prehistoric times Links to full text of the book:

See: A tribute to Thomas Wilson. Svastika is zinc in Indus Script, added to copper to harden it and produce brass https://tinyurl.com/ycyjhdzj

The glyph has been decoded rebus as representing zinc ore (zinc sulphide or zinc oxide) of 3rd millennium BCE Sarasvati Civilization Bronze Age. As an alloying mineral ore, zinc added luster and shine to the brass alloy giving it the hardness of an alloy and a golden appearance.

Alfta Svani Lothursdottirwho transcribed the work in 2003 as a reprint added the following ‘Transcribers Note’:

“This report presented by Thomas Wilson Curator, Department of Prehistoric Anthropology, US National Museum, in 1894, is here reproduced in the hope of educating our fellow Heathens as well as the general public about the Swastika, one of Heathenism’s oldest and most holy of symbols. Since this report was made long before the misuse of this holy symbol by the Nazi’s you will find an unprejudiced presentation of the Swastika and its history. Read on and learn the true history of this holy symbol.”

Fig. 183. (After T. Wilson opcit)

HUT URN IN THE VATICAN MUSEUM.

“Burning altar” mark associated with

Swastikas. Etruria (Bronze Age). "They belonged to the Bronze Age, and antedated the Etruscan civilization. This was demonstrated by the finds at Corneto-Tarquinii. Tombs to the number of about 300, containing them, were found, mostly in 1880-81, at a lower level than, and were superseded by, the Etruscan tombs. They contained the weapons, tools, and ornaments peculiar to the Bronze Age—swords, hatchets, pins, fibulæ, bronze and pottery vases, etc., the characteristics of which were different from Etruscan objects of similar purpose, so they could be satisfactorily identified and segregated. The hut urns were receptacles for the ashes of the cremated dead, which, undisturbed, are to be seen in the museum. The vases forming part of this grave furniture bore the Swastika mark; three have two Swastikas, one three, one four, and another no less than eight." (T. Wilson opcit p.857)

Fig. 175. (After T Wilson opcit)

DETAIL OF ARCHAIC

BŒOTIAN VASE.

Serpents, crosses, and

Swastikas (normal, right,

left, and meander).

Goodyear, “Grammar of

the Lotus,” pl. 60, fig. 9

Fig. 174. (After T Wilson opcit)

ARCHAIC GREEK VASE WITH FIVE SWASTIKAS OF FOUR DIFFERENT FORMS.

Athens. Birch, “History of Ancient Pottery,” quoted by Waring in

“Ceramic Art in Remote Ages,” pl. 41, fig. 15; Dennis, “The

Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria,” i, p. 91. "The Swastika comes from India as an ornament in form of a cone (conique) of metal, gold, silver, or bronze gilt, worn on the ears (see G. Perrot: “Histoire de l’Art,” iii, p. 562 et fig. 384), and nose-rings (see S. Reinach: “Chronique d’Orient,” 3e série, t. iv, 1886). I was the first to make known the nose-ring worn by the goddess Aphrodite-Astarte, even at Cyprus. In the Indies the women still wear these ornaments in their nostrils and ears. The fellahin of Egypt also wear similar jewelry; but as Egyptian art gives us no example of the usage of these ornaments in antiquity, it is only from the Indies that the Phenicians could have borrowed them. The nose-ring is unknown in the antiquity of all countries which surrounded the island of Cyprus." (p.851, T Wildon opcit)

"The Swastika has been discovered in Greece and in the islands of the Archipelago on objects of bronze and gold, but the principal vehicle was pottery; and of these the greatest number were the painted vases. It is remarkable that the vases on which the Swastika appears in the largest proportion should be the oldest, those belonging to the Archaic period. Those already shown as having been found at Naukratis, in Egypt, are assigned by Mr. Flinders Petrie to the sixth and fifth centuries B. C., and their presence is accounted for by migrations from Greece." (p.839 T Wilson opcit)

"Whatever else the sign Swastika may have stood for, and however many meanings it may have had, it was always ornamental. It may have been used with any or all the above significations, but it was always ornamental as well. The Swastika sign had great extension and spread itself practically over the world, largely, if not entirely, in prehistoric times, though its use in some countries has continued into modern times." (T. Wilson, p.772)

Fig. 166. (After T Wilson opcit)

CYPRIAN VASE WITH SWASTIKAS AND FIGURES OF BIRDS.

Perrot and Chipiez, “History of Art in Phenicia and Cyprus,” II, p. 300, fig. 237;

Goodyear, “Grammar of the Lotus,” pl. 48, figs. 6, 12; Cesnola, “Cyprus, its

Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples,” Appendix by Murray, p. 412, pl. 44, fig. 34.

Fig. 178.(After T Wilson opcit) CYPRIAN VASE WITH FIGURES OF

BIRDS AND SWASTIKA IN PANEL. Musée St. Germain. Ohnefalsch-Richter, Bull.

Soc. d’Anthrop., Paris, 1888, p. 674, fig. 6.

When zinc is added to copper, the mineral is hardened and becomes copper. This is signified by this hypertext.

Two geese are shown to signify hardened alloy by metal casting:

dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.

kāraṁḍa 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy' of brass is produced.

kāraṇḍava m. ʻ a kind of duck ʼ MBh. [Cf. kāraṇḍa- m. ʻ id. ʼ R., karēṭu -- m. ʻ Numidian crane ʼ lex.: see karaṭa -- 1] Pa. kāraṇḍava -- m. ʻ a kind of duck ʼ; Pk. kāraṁḍa -- , °ḍaga -- , °ḍava -- m. ʻ a partic. kind of bird ʼ; S. kānero m. ʻ a partic. kind of water bird ʼ< *kāreno.(CDIAL 3059) Rebus: करडा karaḍā Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/images/img214.jpg (After Fig. 201, T. Wilson, p.864)Spearhed with svastika (croix swasticale) and triskelion. Brandenburg. Germany. Waring, 'Ceramic art in remote age,' p. 44. fig. 21 and 'Viking age' I, fig. 336

Fig. 202 (T. Wilson opcit).

BRONZE PIN WITH SWASTIKA, POINTILLÉ,

FROM MOUND IN BAVARIA.

Chantre, Matériaux pour l’Histoire Primitive

et Naturelle de l’Homme, 1854, pp. 14, 120.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/images/img228.jpg After Fig. 220 (T. Wilson opcit.) Stone altar with svastika on pedestal. France museum of Toulouse De Mortillet. 'Musee Prehistorique', fig. 1267.

(After a Plate in: Savita Sharma, 1990, Early Indian symbols, numismatic evidence, Delhi, Agama Kala Prakashan; cf. Shah, UP., 1975, Aspects of Jain Art and Architecture, p.77)

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/images/img240.jpg After Fig. 235 (T. Wilson opcit). Ancient coin with svastika. Gaza. Palestine. Waring 'Ceramic art in remote ages,' pl. 42, fig.6

Fig. 32. (After T Wilson opcit)

FOOTPRINT OF BUDDHA WITH SWASTIKA, FROM AMARAVATI TOPE.

From a figure by Fergusson and Schliemann.

Plate 5. Buffalo with Swastika on Forehead. (After T. Wilson opcit)

Presented to Emperor of Sung Dynasty.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U. S. National

Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D. C. "In the Chinese language the sign of the Swastika is pronounced wan, and stands for “many,” “a great number,” “ten thousand,” “infinity,” and by a synecdoche is construed to mean “long life, a multitude of blessings, great happiness,” etc.; as is said in French, “mille pardons,” “mille remercîments,” a thousand thanks, etc." (T. Wilson opcit, p.800)

The possible migrations of the Swastika, and its appearance in widely separated countries and among differently cultured peoples, afford the principal interest in this subject to archæologists and anthropologists...The Swastika was certainly prehistoric in its origin. It was in extensive use during the existence of the third, fourth, and fifth cities of the site of ancient Troy, of the hill of Hissarlik; so also in the Bronze Age, apparently during its entire existence, throughout western Europe from the Mediterranean Sea to the Arctic Ocean...Professor Sayce is of the opinion that the Swastika was a Hittite symbol and passed by communication to the Aryans or some of their important branches before their final dispersion took place, but he agrees that it was unknown in Assyria, Babylonia, Phenicia, or among the Egyptians...Whether the Swastika was in use among the Chaldeans, Hittites, or the Aryans before or during their dispersion, or whether it was used by the Brahmins before the Buddhists came to India is, after all, but a matter of detail of its migrations; for it may be fairly contended that the Swastika was in use, more or less common among the people of the Bronze Age anterior to either the Chaldeans, Hittites, or the Aryans...Looking over the entire prehistoric world, we find the Swastika used on small and comparatively insignificant objects, those in common use, such as vases, pots, jugs, implements, tools, household goods and utensils, objects of the toilet, ornaments, etc., and infrequently on statues, altars, and the like. In Armenia it was found on bronze pins and buttons; in the Trojan cities on spindle-whorls; in Greece on pottery, on gold and bronze ornaments, and fibulæ. In the Bronze Age in western Europe, including Etruria, it is found on the common objects of life, such as pottery, the bronze fibulæ, ceintures, spindle-whorls, etc. (pp. 950, 951)

Source: Wilson, Thomas, 1894, The Swastika, the earliest known symbol and its migration. Annual Report, US National Museum, pages 757-1011. Washington, DC. Govt. Printing Office. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/40812-h.htm

Thomas Wilson, Curator, Prehistoric Anthropology, US National Museum. His work on the Svastika (spelt swastika) presented in Annual Report 1894 (pp. 763 to 1011) is available at

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/40812-h.htm (Photo from an obituary written by OT Mason, 1902. After Fig. 10 in:

http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/Anthropology/pdf_hi/SCtA-0048.pdf

Thomas Wilson notes in the Preface: "The principal object of this paper has been to gather and put in a compact form such information as is obtainable concerning the Swastika, leaving to others the task of adjustment of these facts and their[Pg 764] arrangement into an harmonious theory. The only conclusion sought to be deduced from the facts stated is as to the possible migration in prehistoric times of the Swastika and similar objects. No conclusion is attempted as to the time or place of origin, or the primitive meaning of the Swastika, because these are considered to be lost in antiquity. The straight line, the circle, the cross, the triangle, are simple forms, easily made, and might have been invented and re-invented in every age of primitive man and in every quarter of the globe, each time being an independent invention, meaning much or little, meaning different things among different peoples or at different times among the same people; or they may have had no settled or definite meaning. But the Swastika was probably the first to be made with a definite intention and a continuous or consecutive meaning, the knowledge of which passed from person to person, from tribe to tribe, from people to people, and from nation to nation, until, with possibly changed meanings, it has finally circled the globe." (ibid., p. 764)

Source: Wilson, Thomas, 1894, The Swastika, the earliest known symbol and its migration. Annual Report, US National Museum, pages 757-1011. Washington, DC. Govt. Printing Office. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/40812-h.htm

Thomas Wilson, Curator, Prehistoric Anthropology, US National Museum. His work on the Svastika (spelt swastika) presented in Annual Report 1894 (pp. 763 to 1011) is available at

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40812/40812-h/40812-h.htm (Photo from an obituary written by OT Mason, 1902. After Fig. 10 in:

http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/Anthropology/pdf_hi/SCtA-0048.pdf

Thomas Wilson notes in the Preface: "The principal object of this paper has been to gather and put in a compact form such information as is obtainable concerning the Swastika, leaving to others the task of adjustment of these facts and their[Pg 764] arrangement into an harmonious theory. The only conclusion sought to be deduced from the facts stated is as to the possible migration in prehistoric times of the Swastika and similar objects. No conclusion is attempted as to the time or place of origin, or the primitive meaning of the Swastika, because these are considered to be lost in antiquity. The straight line, the circle, the cross, the triangle, are simple forms, easily made, and might have been invented and re-invented in every age of primitive man and in every quarter of the globe, each time being an independent invention, meaning much or little, meaning different things among different peoples or at different times among the same people; or they may have had no settled or definite meaning. But the Swastika was probably the first to be made with a definite intention and a continuous or consecutive meaning, the knowledge of which passed from person to person, from tribe to tribe, from people to people, and from nation to nation, until, with possibly changed meanings, it has finally circled the globe." (ibid., p. 764)

Thomas Wilson’s work was written 1894, well before the discoveries reported from Mohenjo-daro and Harappa announcing a civilization of 3rd millennium BCE in ancient India.

"Yolamira, silver drachm, early type.....c. 125-150 AD......Diademed bust right, dotted border /Swastika right, Brahmi legend ..... Yolamirasa Bagarevaputasa Pāratarāja ......(Of Yolamira, son of Bagareva, Pārata King).....The names Yolamira and Bagareva betray the Iranian origin of this dynasty. The suffix Mira refers to the Iranian deity Mithra. Yolamira means "Warrior Mithra." Bagareva means "rich God." "The Pāratarājas are identified as such by their coins: two series of coins, one mostly in copper bearing legends in Kharoshthi and the other mostly in silver bearing legends in Brahmi. Among coins known so far, there has been no overlap between the two series, which appear to be quite separate from one another, despite commonalities of content. The notable feature of both series is that almost all of the coins bear the name ‘Pāratarāja’ as part of the legend, and they nearly always bear a swastika on the reverse (the exceptions being some very small fractions that seem to eliminate the swastika and/or the long legend, including the words ‘Pāratarāja’, for lack of space). The coins are very rare and, when found, are discovered almost exclusively in the Pakistani province of Baluchistan, reportedly mostly in the area of Loralai..."......NEW LIGHT ON THE PĀRATARĀJAS by PANKAJ TANDON.......http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf http://balkhandshambhala.blogspot.in/

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

Many coins and seals of ancient India carry the Swastika symbol.

Satavahana coin, Copper, die-struck symbol of lion standing to right and a bigSwastika above on obverse, tree on reverse with a counter mark. As these coins are un-inscribed their issues cannot be ascertained with certainty. They ae actually regarded as the earliest coins of India.

Yolamira, silver drachm, early type c. 125-150 CE. Legend around Swastika is inBrahmi lipi (script).

Kuninda, an ancient central Himalayan kingdom, c. 1st century BCE, silver coin. Rev: Stupa surmounted by the Buddhist symbols triratna, surrounded by a Swastika, a "Y" symbol, and a tree in railing. Legend in Kharosthi script.

Corinthia, Circa 550-500 BC. Stater (Silver). Pegasos, with curved wing, flying to left; below, koppa. Reverse. Incuse in the form of a Swastika to left. (Source: Wikipedia)

Bharhut

"According to Bon tradition, the founder of the orthodox Bon doctrine was Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche of Tagzig...... some writers identify the region with Balkh/Bactria. The name Shenrab has an Iranian sound to it.....One of the most powerful and resonant words in pre-Buddhist Tibet was yungdrung (g.yung drung). It was a the key terms for the old royal religion, the mythological backdrop to the kingly lineage of the Tibetan Empire. For example, the inscription of the tomb of Trisong Detsen has the line: “In accord with the eternal (yungdrung) customs (tsuglag), the Emperor and Divine Son Trisong Detsen was made the ruler of men.” I discussed how to translate that term tsuglag in an earlier post. Here, as you no doubt noticed, I have translated yungdrung here as “eternal”. Eternity seems to be the general meaning of yungdrung in the early religion. In addition, the word was associated with the ancient Indo-European swastika design, which in Tibet was the graphic symbol of the eternal...what did the early Buddhist writers and translators do with this term? Many of them just attached it to the word “dharma” (i.e. Buddhism), no doubt in an attempt to transfer its prestige from the earlier religion to Buddhism. Thus we see “the eternal dharma” (g.yung drung chos) in many Dunhuang manuscripts.".....http://earlytibet.com/2008/04/30/buddhism-and-bon-iii-what-is-yungdrung/

"the Pāradas of the Mahabharata, the Puranas and other Indian sources........

"...coins of Yolamira is in itself a breakthrough, as this is one king for whom we have independent evidence. Konow reports on some pottery fragments from Tor Dherai in the Loralai district that carry an inscription relating to one Shahi Yolamira. Konow says the name Yolamira is not known to us. These coins, found in the same area, provide further evidence of the existence of this king, and can place him in some historical context.....Once again, the validity of this reading is buttressed by examining the meaning of the name. In Bactrian, the name Yola-mira means ‘warrior Mithra’....http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"...Of the Shahi Yola Mira, the master of the vihara, this water hall (is) the religious gift, in his own Yola-Mira-shahi-Vihara, to the order of the four quarters, in the acceptance of the Sarvastivadin teachers. And from this right donation may there be in future a share for (his) mother and father, in future a share for all beings and long life for the master of the law’ .......Sten Konow, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. II pt. I, pp. 173

"....As permanent monasteries became established, the name "Vihara" was kept. Some Viharas became extremely important institutions, some of them evolving into major Buddhist Universities with thousands of students, such as Nalanda."

"fixing the reign of this dynasty in the interior of Baluchistan during the second and perhaps the third centuries AD fills an important gap in the history of the region. Very little has hitherto been known of the politics of this area from the time of Alexander’s departure to the arrival of Islamic invaders in the early eighth century. Some historians have tended to assume that the Kushans must have held sway over this region, but that hypothesis does not appear to be correct, as the Pāratarājas appear to have been ruling precisely at the time when the Kushan empire was at its zenith...".......http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"Given Konow’s suggestion that Kanishka began the use of the term Shahi, a suggested date for the Pāratarājas would be around the middle of the second century, give or take a quarter century or so."........http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"The swastika mark is not encountered on Kushan coins, but it is an element on Kushanshah coins.."..http://www.academia.edu/2078818/The_Mint_Cities_of_the_Kushan_Empire

"The Kabul Shahi also called Shahiya dynasties ruled one of the Middle kingdoms of India which included portions of the Kabulistan and the old province of Gandhara (now in northern Pakistan), from the decline of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century to the early 9th century. The kingdom was known as Kabul Shahi (Kabul-shāhān or Ratbél-shāhān in Persian کابلشاهان یا رتبیل شاهان) between 565 and 879 when they had Kapisa and Kabul as their capitals, and later as Hindu Shahi.....The Shahis of Kabul/Gandhara are generally divided into the two eras of the "Buddhist Shahis" and the "Hindu Shahis", with the change-over thought to have occurred sometime around 870 AD with the Arab conquest....."....Sehrai, Fidaullah (1979). Hund: The Forgotten City of Gandhara,

"The mountainous region of Central Asia comprising the eastern parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan and northwest India has always known war. Even now, the area, high in the Hindu Kush mountains, proves difficult to hold......In the sixth century C.E., the place was known as Gondhara, and nominally controlled by the Huns—a people famed for being great horsemen and even greater warriors. Some 200 years later, Gondhara was ruled by a succession of kings called the Hindu Shahi.....It was the Hindu Shahi kings who first minted these silver coins—a simple and elegant representation of the diversity of the region. On one side is the Hun soldier on horseback; on the reverse, the bull that is so sacred to the Hindus."....http://www2.educationalcoin.com/2012/12/21/bull-horse/

Charles Frederick Oldham The Sun and the Serpent: A Contribution to the History of Serpent-worship, 1905..Serpent worship; The Shahis of Afghanistan

"King standing facing, head turned to right, Brāhmi legend at left: Koziya....Koziya issued several differnt types of copper drachms, some of very fine style, such as this one. So Koziya must have risen to the throne as a teenager and probably had quite a long reign, given the wide variety of types he issued."....http://coinindia.com/galleries-parata-rajas.html

"the Pāradas of the Mahabharata, the Puranas and other Indian sources........

"...coins of Yolamira is in itself a breakthrough, as this is one king for whom we have independent evidence. Konow reports on some pottery fragments from Tor Dherai in the Loralai district that carry an inscription relating to one Shahi Yolamira. Konow says the name Yolamira is not known to us. These coins, found in the same area, provide further evidence of the existence of this king, and can place him in some historical context.....Once again, the validity of this reading is buttressed by examining the meaning of the name. In Bactrian, the name Yola-mira means ‘warrior Mithra’....http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"...Of the Shahi Yola Mira, the master of the vihara, this water hall (is) the religious gift, in his own Yola-Mira-shahi-Vihara, to the order of the four quarters, in the acceptance of the Sarvastivadin teachers. And from this right donation may there be in future a share for (his) mother and father, in future a share for all beings and long life for the master of the law’ .......Sten Konow, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. II pt. I, pp. 173

"....As permanent monasteries became established, the name "Vihara" was kept. Some Viharas became extremely important institutions, some of them evolving into major Buddhist Universities with thousands of students, such as Nalanda."

"fixing the reign of this dynasty in the interior of Baluchistan during the second and perhaps the third centuries AD fills an important gap in the history of the region. Very little has hitherto been known of the politics of this area from the time of Alexander’s departure to the arrival of Islamic invaders in the early eighth century. Some historians have tended to assume that the Kushans must have held sway over this region, but that hypothesis does not appear to be correct, as the Pāratarājas appear to have been ruling precisely at the time when the Kushan empire was at its zenith...".......http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"Given Konow’s suggestion that Kanishka began the use of the term Shahi, a suggested date for the Pāratarājas would be around the middle of the second century, give or take a quarter century or so."........http://people.bu.edu/ptandon/Paratarajas.pdf

"The swastika mark is not encountered on Kushan coins, but it is an element on Kushanshah coins.."..http://www.academia.edu/2078818/The_Mint_Cities_of_the_Kushan_Empire

"The Kabul Shahi also called Shahiya dynasties ruled one of the Middle kingdoms of India which included portions of the Kabulistan and the old province of Gandhara (now in northern Pakistan), from the decline of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century to the early 9th century. The kingdom was known as Kabul Shahi (Kabul-shāhān or Ratbél-shāhān in Persian کابلشاهان یا رتبیل شاهان) between 565 and 879 when they had Kapisa and Kabul as their capitals, and later as Hindu Shahi.....The Shahis of Kabul/Gandhara are generally divided into the two eras of the "Buddhist Shahis" and the "Hindu Shahis", with the change-over thought to have occurred sometime around 870 AD with the Arab conquest....."....Sehrai, Fidaullah (1979). Hund: The Forgotten City of Gandhara,

"The mountainous region of Central Asia comprising the eastern parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan and northwest India has always known war. Even now, the area, high in the Hindu Kush mountains, proves difficult to hold......In the sixth century C.E., the place was known as Gondhara, and nominally controlled by the Huns—a people famed for being great horsemen and even greater warriors. Some 200 years later, Gondhara was ruled by a succession of kings called the Hindu Shahi.....It was the Hindu Shahi kings who first minted these silver coins—a simple and elegant representation of the diversity of the region. On one side is the Hun soldier on horseback; on the reverse, the bull that is so sacred to the Hindus."....http://www2.educationalcoin.com/2012/12/21/bull-horse/

Charles Frederick Oldham The Sun and the Serpent: A Contribution to the History of Serpent-worship, 1905..Serpent worship; The Shahis of Afghanistan

"King standing facing, head turned to right, Brāhmi legend at left: Koziya....Koziya issued several differnt types of copper drachms, some of very fine style, such as this one. So Koziya must have risen to the throne as a teenager and probably had quite a long reign, given the wide variety of types he issued."....http://coinindia.com/galleries-parata-rajas.html

"Bagolago is a Bactrian term.....the Bagolago at Mat (Mathura)......equivalent Prakit term 'devakula' appears in the inscriptions....the Mat site is one of three certain complexes (others are Surkh Khotal and Rabat) which are part of the same sort of ritual activity....There may be many more similar sites....as many as eight sites.......There is no way for certain what a Bagolago was....The sites have several features in common. They are not public spaces...have an association with water...had erections of both Kings and Gods....unclear if the kings attended the gods or vice-versa......there served some dynastic purpose but terms such as 'dynastic shrine' or 'dynastic cult' may be too strong....the presence of the Bagolago at Mat emphasizes the importance of Mathura....Mathura was the capital of Surasena which the Kushans ruled....http://www.academia.edu/2078818/The_Mint_Cities_of_the_Kushan_Empire

" The meager remains of Bactrian so far described are usefully supplemented by some identifiable Bactrian loanwords in other, better-known languages. As well as words already attested in Bactrian (e.g., Pers, xidēv < Bactr. xoadēo “lord,” Kroraina Prakrit personal name Vaǵamareǵa < bago “god” plus marēgo “servant”) these include some new vocabulary".....bagolaggo [-ŋg] “temple”),..... most of the “Bactrian” legends are virtually identical in vocabulary and phraseology to their Pahlavi equivalents. A legend such as bago pirōzo oazarko košano šauo “Lord Pērōz, great Kušānšāh” may be compared with the Pahl.....http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bactrian-language

"..... 'devakula' in Mathura we will return to this type of site later. ..... the only Jain Stupa known from the period; and most important, the Bagolago at Mat."

Kula-Deva (Sanskrit) ......Domestic god

कुल ...kula: chief ...family ...inhabited country ...residence of a family ...seat of a community ...lineage [ family ] ...clan ...high station ...caste ...race ...noble or eminent family or race ...tribe

"Kanishka...........SHAR had many meanings in the ancient cultures of the Near East, it meant both celestial bodies and master. UONONKCHE, which can be also read as VONONTE, was the name of a number of historical personalities - for example the Parphian king Vonones, its successor Vonones, the second name or more exactly - the title of the conqueror of Bactria - the Kushan ruler Kanishka, called Uanando Bagolago. All names stem from the epithet Vanand ('victorious, presented with the grace of the Gods'), which is of very ancient origin with roots in the Sumero-Accadian and from there in the Sanskrit culture. Since the eastern Iranian languages replaced "o" with "a" (which is also characteristic to the modern Mundjan and Tadjik languages), in Old Parphian this epithet was pronounced as VONONES, while for the Kushans - as UANAND.. ".....http://ashrafonline.net/vb/showthread.php?p=316003

Канишки (Канишка) звучало Uanando Bagolago

نصف الأبجدية الهركليفية 14/28 اكتشفت من طرف العلماء العرب في ... ......The best example is a stamp of Tervel, where next to the face of the ruler are ... the conqueror of Bactria - the Kushan Ruler Kanishka, called Uanando Bagolago....http://ar.cyclopaedia.net/wiki/Kushan_Ruler

"Kanishka I (Sanskrit: कनिष्क; Bactrian: Κανηϸκι, Kaneshki; Middle Chinese: 迦腻色伽 (Ka-ni-sak-ka > New Chinese: Jianisejia), or Kanishka the Great, was the emperor of the Kushan dynasty in 127–151 AD.....famous for his military, political, and spiritual achievements. A descendant of Kushan empire founder Kujula Kadphises, Kanishka came to rule an empire in Bactria extending from Turfan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain during the Golden Age of the Kushanas. The main capital of his empire was located at Puruṣapura in Gandhara (Peshawar in present Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan), with two other major capitals at ancient Kapisa (present Bagram, Afghanistan) and Mathura, India. His conequests and patronage of Buddhism played an important role in the development of the Silk Road, and the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism from Gandhara across the Karakoram range to China."

Iranian/Indic phase.....Following the transition to the Bactrian language on coins, Iranian and Indic divinities replace the Greek ones: ΜΑΝΑΟΒΑΓΟ (manaobago, Vohu Manah ).......Vohu Manah is the Avestan language term for a Zoroastrian concept, generally translated as "Good Purpose" or "Good Mind" (cognate with Sanskrit vasu manas), referring to the good moral state of mind that enables an individual to accomplish his duties.

Surkh Kotal...... 36.03N, 68.55E......."That Surkh Kotal was a major site of direct importance to the Kushan dynasty is beyond doubt. It is the site of a bagolago, a dynastic shrine associated with the period from Wima Kadphises to Huvishka........http://www.kushan.org/sources/coin/sites.htm......Ball, 1982: no.1123 ....Ball, W (1982) Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Catalogue des Sites Archaeologiques D'Afghanistan. 2 Volumes.

"The Rabatak inscription is an inscription written on a rock in the Bactrian language and the Greek script, which was found in 1993 at the site of Rabatak, near Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan. The inscription relates to the rule of the Kushan emperor Kanishka, and gives remarkable clues on the genealogy of the Kushan dynasty."

"Jamal Garhai is ancient Gandharan site located 13 kilometers from Mardan in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in northern Pakistan. Jamal Garhi was a Buddhist monastery from the first until the fifth century AD at a time when Buddhism flourished.....The most remarkable find in Jamal Garhi is the circular stupa situated on high ground to the west of the main clump of edifices. The stupa is surrounded by a ring of cubicles that may have either served as shrines housing images of Buddha or prayer chambers for the devout. The superior stonework and symmetry of the stupa are notable..... The Central Asiatic Kushans, originally fire worshippers, had embraced Buddhism and followed their new faith with the customary zeal of recent converts. In fact, Huvishka’s predecessor, the great Kanishka, is commemorated to this day for his ardent pursuit of ordering some of the most monumental stupas ever to be raised...........http://odysseuslahori.blogspot.com/2014/10/Jamal-Garhi.html

"The Kushan empire emerged as one of the most powerful empire empire during first century A.D. in central Asia.....Kushanas had very unique system of administrative system. King was highest level of administration. King and kingship was linked with divine rule.The Kushana kings generally used exalted titles like maharajadhiraja (king of kings), daivaputra (son of heaven), soter (Saviour) and kaisara (Caesar). The Kushans had appointed ksatrapas and mahaksatrapas for different units of the empire. There were other officials performing both civil and military functions, called dandanayaka and mahadandanayaka.......The Kushans seem to have followed the earlier existing pattern of the Indo-Greeks and Parthians by appointing ksatrapas and mahaksatrapas for different units of the empire. There were other officials performing both civil and military functions, called dandanayaka and mahadandanayaka. At village level, gramika and padrapala– both signifying ‘village headman’, who collected the king’s dues and took cognizance of crimes in his area."......

"It seems that the Kushans, upon becoming masters of Bactria, at first continued the traditional use of Greek as a medium of written communication. As a spoken language they had adopted Bactrian, the native idiom of the country, which they afterwards elevated to the status of a written language and employed for official purposes, perhaps as a result of increasing national or dynastic pride. The earliest known inscriptions in Bactrian (the “unfinished inscription” from Surkh Kotal, cf. A. D. H. Bivar, BSOAS 26, 1963, pp. 498-502, and the Dašt-e Nāvūr trilingual) belong to the reign of Vima Kadphises. A few decades later, early in the reign of Kanishka I, Bactrian replaced Greek on the Kushan coins. After this period Greek ceased to be used as an official language in Bactria (although later instances of its use by Greek settlers are known, cf. P. M. Fraser, Afghan Studies 3-4, 1982, pp. 77f.)."....http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bactrian-language

Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress.....Page 138 ...By John R. Hinnells

Necklaces with a number of pendants

aṣṭamangalaka hāra

aṣṭamangalaka hāra depicted on a pillar of a gateway(toran.a) at the stupa of Sanchi, Central India, 1st century BCE. [After VS Agrawala, 1969, Thedeeds of Harsha (being a cultural study of Bāṇa’s Harṣacarita, ed. By PK Agrawala, Varanasi:fig. 62] The hāra or necklace shows a pair of fish signs together with a number of motifsindicating weapons (cakra, paraśu,an:kuśa), including a device that parallels the standard device normally shown in many inscribed objects of SSVC in front of the one-horned bull.

•

(cf. Marshall, J. and Foucher,The Monuments of Sanchi, 3 vols., Callcutta, 1936, repr. 1982, pl. 27).The first necklace has eleven and the second one has thirteen pendants (cf. V.S. Agrawala,1977, Bhāratīya Kalā , Varanasi, p. 169); he notes the eleven pendants as:sun,śukra, padmasara,an:kuśa, vaijayanti, pan:kaja,mīna-mithuna,śrīvatsa, paraśu,

darpaṇa and kamala. "The axe (paraśu) and an:kuśa pendants are common at sites of north India and some oftheir finest specimens from Kausambi are in the collection of Dr. MC Dikshit of Nagpur."(Dhavalikar, M.K., 1965, Sanchi: A cultural Study , Poona, p. 44; loc.cit. Dr.Mohini Verma,1989, Dress and Ornaments in Ancient India: The Maurya and S'un:ga Periods,Varanasi, Indological Book House, p. 125).

Svastika glyph: sattva 'svastika' glyph సత్తుతపెల a vessel made of pewter त्रपुधातुविशेषनिर्मितम्

Glosses for zinc are: sattu (Tamil), satta, sattva (Kannada) jasth जसथ् त्रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas ज्तस), zinc, spelter; pewter; zasath ्ज़स््थ््or zasuth ज़सुथ्।रप m. (sg. dat. zastas ुज़्तस),् zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast). jastuvu; ।त्रपूद्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter.(Kashmiri).

The cognate word satuvu has the semantics, 'strength, hardness'. This means, that zinc has the chemical characteristic of hardening soft copper when alloyed with copper to produce brass. So, the ancient word for zinc is likely to be sattva.

Or. ṭaü ʻ zinc, pewter ʼ(CDIAL 5992). jasta 'zinc' (Hindi) sathya, satva 'zinc' (Kannada) The hieroglyph used on Indus writing consists of two forms: 卐卍. Considering the phonetic variant of Hindi gloss, it has been suggested for decipherment of Meluhha hieroglyphs in archaeometallurgical context that the early forms for both the hieroglyph and the rebus reading was: sattvaa. trápu n. ʻ tin ʼ AV.Pa. tipu -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; Pk. taü -- , taüa -- n. ʻ lead ʼ; P. tū̃ m. ʻ tin ʼ; Or. ṭaü ʻ zinc, pewter ʼ; OG. tarūaüṁ n. ʻ lead ʼ, G. tarvũ n. -- Si. tum̆ba ʻ lead ʼ GS74, but rather X tam̆ba < tāmrá --(CDIAL 5992)

sattu (Tamil), satta, sattva (Kannada) jasth जसथ् ।रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas ज्तस), zinc, spelter; pewter; zasath ् ज़स््थ् ्or zasuth ज़सुथ ्। रप m. (sg. dat. zastas ु ज़्तस),् zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast). jastuvu; । रपू्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter.(Kashmiri). Hence the hieroglyph: svastika repeated five times. Five svastika are thus read: taṭṭal sattva Rebus: zinc (for) brass (or pewter). *ṭhaṭṭha1 ʻbrassʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass?]N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 1.Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H.ṭhaṭherā m.(CDIAL 5491, 5493).

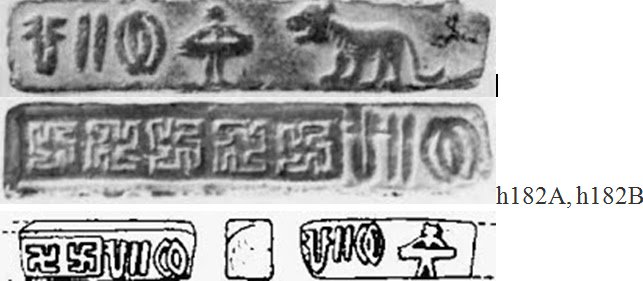

The hieroglyph: svastika repeated five times on h182. Five svastika are thus read: taṭṭal sattva Rebus: zinc (for) brass (or pewter).See five svastika on Mohenjodaro prism tablet (m488)

The drummer hieroglyph is associated with svastika glyph on this tablet (har609) and also on h182A tablet of Harappa with an identical text.

dhollu ‘drummer’ (Western Pahari) Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. The 'drummer' hieroglyph thus announces a cast metal. The technical specifications of the cast metal are further described by other hieroglyphs on side B and on the text of inscription (the text is repeated on both sides of Harappa tablet 182).

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'alloy of five metals, pancaloha' (Tamil). kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.) कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil) kōla1 m. ʻ name of a degraded tribe ʼ Hariv.

Pk. kōla -- m.; B. kol ʻ name of a Muṇḍā tribe ʼ.(CDIAL 3532)

Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith.

Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith(Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.)kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge.(DEDR 2133)

ḍhol ‘drum’ (Gujarati.Marathi)(CDIAL 5608) Rebus: large stone; dul ‘to cast in a mould’. Kanac ‘corner’ Rebus: kancu ‘bronze’. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. kanka ‘Rim of jar’ (Santali); karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus:karṇaka ‘scribe’ (Telugu); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) Thus, the tablets denote blacksmith's alloy cast metal accounting including the use of alloying mineral zinc -- satthiya 'svastika' glyph.

The Meluhha gloss for 'five' is: taṭṭal Homonym is: ṭhaṭṭha brass (i.e. alloy of copper + zinc). Glosses for zinc are: sattu (Tamil), satta, sattva (Kannada) jasth जसथ् ।रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas ज्तस), zinc, spelter; pewter; zasath ् ज़स््थ् ्or zasuth ज़सुथ ्। रप m. (sg. dat. zastas ु ज़्तस),् zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast). jastuvu; । रपू्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter.(Kashmiri). Hence the hieroglyph: svastika repeated five times. Five svastika are thus read: taṭṭal sattva Rebus: zinc (for) brass (or pewter). jasta = zinc (Hindi) yasada (Jaina Pkt.)

*ṭhaṭṭha1 ʻbrassʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass?]N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 1.Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H.ṭhaṭherā m.(CDIAL 5491, 5493).

Hence, the gloss to denote sulphate of zinc: తుత్తము [ tuttamu ] orతుత్తరము tuttamu. [Tel.] n. Vitriol.పాకతుత్తము white vitriol, sulphate of zinc.మైలతుత్తము sulphate of copper, blue-stone. తుత్తినాగము [ tuttināgamu ] tutti-nāgamu. [Chinese.] n. Pewter. Zinc.లోహవిశేషము .துத்தம்² tuttam, n. < tuttha. 1. A prepared arsenic, vitriol, sulphate of zinc or copper; வைப்புப்பாஷாணவகை. (சூடா.) 2. Tutty, blue or white vitriol used as collyrium; கண் மருந்தாக உதவும் துரிசு. (தைலவ. தைல. 69.)

சத்து³ cattu, n. prob. šilā-jatu. 1. A variety of gypsum; கர்ப்பூரசிலாசத்து. (சங். அக.) 2. Sulphate of zinc; துத்தம். (பைஷஜ. 86.)

Hieroglyphs, allographs:

தட்டல் taṭṭal Five, a slang term; ஐந்து என்பதன் குழூஉக்குறி. (J .) Rebus: தட்டான்¹ taṭṭāṉ, n. < தட்டு-. [M. taṭṭān.] Gold or silver smith, one of 18 kuṭimakkaḷ, q. v.; பொற்கொல்லன். (திவா.) Te. taṭravã̄ḍu goldsmith or silversmith. Cf. Turner,CDIAL, no. 5490, *ṭhaṭṭh- to strike; no. 5493, *ṭhaṭṭhakāra- brassworker; √ taḍ, no. 5748, tāˊḍa- a blow; no. 5752, tāḍáyati strikes.

*ṭhaṭṭha ʻ brass ʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass? --N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 2. *ṭhaṭṭhakara -- 1. Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H. ṭhaṭherā m. (CDIAL 5491, 5493).