Prof Asko Parpola (Helsinki University) argues that the mirror was not known in Vedic India until it was introduced by the Persians in 600 BCE. offering a histo.basis to study the Vedic literature. Studia Orientalia Electronica vol. 7 (2019): 1-29.

This argument of Asko Parpola is countered in this monograph.

There are two Indo-European root words which link to the semantics of 'mirror': der(ep)- 'to see, mirror'; drych m. (*dr̥ksos) sight, mirror'. Cognate Meluhha pronunciation variants include:

Set 1: Pa. dappana -- m. ʻ mirror ʼ, Pk. dappaṇa -- m.; A. dāpan ʻ mirror ʼ, dāpani ʻ a bellmetal utensil used by groom in marriage ceremony ʼ; Si. dapaṇa, däp˚ ʻmirrorʼ. Addenda: darpaṇa -- : A. also spel. dāpon ʻ mirror ʼ.

Set 2: Pa. ādāsa -- , ˚aka -- m., Pk. ādaṁsa -- , ˚aga -- , āyaṁsa -- , ˚aga -- , āyāsa -- ; -- MIA. *ādariśa -- : Pk. ādarisa -- , āya˚ m.; Paš. rešó, Shum. reṣe (ṣ!), S. āhirī f., L. ārhī, a˚ f., WPah. jaun. ārśī

Archaeological evidence attests the production of high-tin-bronze mirrors, using cire perdue (lost-wax casting) technique in many parts of Eurasia including Sarasvati Civiization, dated to ca. 4th millennium BCE.

It is extraordinary that Asko Parpola makes a fallacious statement that the mirror was not known in Vedic India until it was introduced by the Persians in 600 BCE. The existence of a bronze mirror is attested from Balochistan and from sites such as Rakhigarhi and Dholavira.

Bronze mirror. Dholavira. Courtesy: ASI

Bronze mirror. Dholavira. Courtesy: ASIAttested techniques of Aranmula high-tin-bronze mirror can certainly be traced to the Sarasvati Civilization tradition of creating metal alloys. In this context, I cite the work of Jainagesh Sekhar, et al, 2015, Ancient Metal Mirror Alloy Revisited: Quasicrystalline Nanoparticles Observed in JOM: the journal of the Minerals, Metals & Materials Society 67(12) · July 2015

DOI: 10.1007/s11837-015-1524-3 Ta. kaṇṇāṭi, kaṇṇaṭi mirror of metal or glass, glass things, spectacles (< kaṇ eye + āṭi mirror, crystal). Ma. kaṇṇāṭimirror, glass; kaṇṇaṭa spectacles. To. koṇoḍy mirror, spectacles. Ka. kannaḍi, kanaḍi mirror, pane of glass, lens of spectacles, pair of spectacles; kanaḍaka pair of spectacles; kannaḍisu to mirror, appear. Koḍ. kannaḍi glass, mirror. Tu. kaṇṇaḍi, kannaḍi glass, mirror, pair of spectacles; kannaḍaka pair of spectacles, eye-glass. (DEDR 1182).

See: Interactions between Meluhha metalsmiths and Barbar temple artisans evidenced by high-tin bronze mirror handles https://tinyurl.com/y6weq27o This link provides evidence of a bronze mirror discovered in Barbar temple, concordant with Kulli culture.The Barbar Temple is an archaeological site located in the village of Barbar, Bahrain, and considered to be part of the Dilmun culture. The most recent of the three Barbar temples was rediscovered by a Danish archaeological team in 1954. A further two temples were discovered on the site with the oldest dating back to 3000 BCE.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbar_TempleA tribute to the inventive genius of the Baluchistan metal-smiths of the period

Piggott, 1961, Prehistoric India, Harmondsworth, p. 112. Female figure with breasts, with arms akimbo. Compares with the handle of bronze mirror found in Barbar temple whish shows a male figure with arms joined on the chest in a worshipful pose.

Nagaraja Rao notes that this handle resembles a mirror from the Kulli site of Mehi in Baluchistan.

(Stein, A., 1931, An archaeological tour in Gedrosia,Memoirs of ASI 43,: pi.32. Mehi II, 1.2.a; Possehl 1986: 48, Mehi II.1.2.a). These objects are similar to the head of the figure handle in the Mehi example is actually the face of the mirror itself. (Julian Reade, 2013, Indian Ocean in Antiquity, Routledge, p.26). These comments of Julian Reade have to be seen in the context of the artifacts with Indus Script hypertexts discovered in Kulli culture (Mehi). Kulli culture provides indication of working with magnetite, ferrite ore and with alloys of copper with high tin content resulting in the bronze mirrors. At Mehi were found several decorated chlorite vessels, imported from Tepe Yahya and attesting trade contacts with the Eastern Iran. Copper and bronze was known. These are indications that Kulli culture artisans were trade partners with Sarasvati Civilization.

Nagaraja Rao notes that this handle resembles a mirror from the Kulli site of Mehi in Baluchistan.

(Stein, A., 1931, An archaeological tour in Gedrosia,Memoirs of ASI 43,: pi.32. Mehi II, 1.2.a; Possehl 1986: 48, Mehi II.1.2.a). These objects are similar to the head of the figure handle in the Mehi example is actually the face of the mirror itself. (Julian Reade, 2013, Indian Ocean in Antiquity, Routledge, p.26). These comments of Julian Reade have to be seen in the context of the artifacts with Indus Script hypertexts discovered in Kulli culture (Mehi). Kulli culture provides indication of working with magnetite, ferrite ore and with alloys of copper with high tin content resulting in the bronze mirrors. At Mehi were found several decorated chlorite vessels, imported from Tepe Yahya and attesting trade contacts with the Eastern Iran. Copper and bronze was known. These are indications that Kulli culture artisans were trade partners with Sarasvati Civilization.

अरसा arasā m (तव्याचा जातां बुरसा ॥ मग तोचि होय सहज अ0 ॥ अरशापुढें कोळसा Used where a thing remarkably foul, vile, base, or bad is compared with a thing remarkably bright, pure, fine, or good. अर- शा सारखा Bright and clear as a mirror;--used lit. fig. of houses, rooms, accounts, handwriting, business. अरशासारखें तोंड-मुख-चेहरा A clear complexion or beautiful countenance. (Marathi) आ-दर्श a looking-glass , mirror S3Br. Br2A1rUp. MBh.

&c ifc. " Mirror " (in names of works) e.g. आतङ्क- , दान- , साहित्य- (Monier-Williams) dárpaṇa m. ʻ mirror ʼ Hariv. [√dr̥p ?]Pa. dappana -- m. ʻ mirror ʼ, Pk. dappaṇa -- m.; A. dāpan ʻ mirror ʼ, dāpani ʻ a bellmetal utensil used by groom in marriage ceremony ʼ; Si. dapaṇa, däp˚ ʻmirrorʼ. Addenda: darpaṇa -- : A. also spel. dāpon ʻ mirror ʼ.(CDIAL 6201) آرسئِي ār-saʿī, s.f. (6th) (HI. ارسي ) A mirror, a small mirror for the thumb worn by women. Sing. and Pl.; آهنه āhinaʿh, s.f. (3rd) A mirror, a looking- glass. Pl. يْ ey.See آهينه and آئينه (Pashto) aina ऐन

or öna आ॑न (=आदर्शः m. a mirror, a looking-glass (Śiv. 500, 558, 1547). K.Pr. spells this word āīnah, transliterating the Pers. -दा॑रू॒ । आदर्शकवाटः a door ornamented with mirrors. -goru -ग॑रु॒ । दर्पणसम्पादकः m. a mirror-maker; a seller of mirrors. -khünḍü -ख॑ण्डू॒ । आदर्शखण्डः f. a piece of a mirror. -khạpüṭü -ख॑प॒॑टू॒ । सूक्ष्मतुच्छ आदर्शः f. a small mirror, of no value or use. -khôṭu -खोँटु॒ । आदर्शपिधानम् m. a mirror-cover, or mirror-case. -phuṭu -फुटू॒ । भग्नलघुदर्पणः f. a broken piece of looking-glass. -wöjü -वा॑जू॒ । सादर्शोर्मिका f. a kind of finger-ring, fitted with a tiny mirror. -zömpāna -ज़ा॑म्पान । आदर्शमयशिबिका m. a palanquin, the doors and other parts of which are made of mirrors of glass, crystal, or the like; hence, met., a very fragile conveyance.(Kashmiri)

Root / lemma: der(ep)-

English meaning: to see, *mirror

German meaning: `sehen'ö

Material: Old Indian dárpana- m. `mirror'; gr. δρωπάζειν, δρώπτειν `see' (with lengthened grade 2. syllableöö).

Note:

The Root / lemma: der(ep)- : `to see, *mirror' could have derived from Root / lemma: derbh- : `to wind, put together, *scratch, scrape, rub, polish'

References: WP. I 803; to forms -ep- compare Kuiper Nasalpras. 60 f.

See also: compare also δράω `sehe' and derk̂-`see'.

Page(s): 212

ādarśá m. ʻ mirror ʼ ŚBr., ˚aka -- m. R. [√dr̥ś ] Pa. ādāsa -- , ˚aka -- m., Pk. ādaṁsa -- , ˚aga -- , āyaṁsa -- , ˚aga -- , āyāsa -- ; -- MIA. *ādariśa -- : Pk. ādarisa -- , āya˚ m.; Paš. rešó, Shum. reṣe (ṣ!), S. āhirī f., L. ārhī, a˚ f., WPah. jaun. ārśī, Ku. N. ārsi; A. ārhi ʻ likeness ʼ; B. ārsi ʻ mirror ʼ (→ A. ārsi), Or. ārisi, ˚asi, Bhoj. Aw. lakh. ārasī, H. ārsī f.; OG. ārīsaü (< MIA. *āarissa-- ?), G. ārīsɔ, ar˚, ārsɔ m. ʻ large mirror ʼ, ārsī f. ʻ small do. ʼ, (→)P. ārsī f., S. ārisī, ārsī f.); M. ārsā, ar˚ m. ʻ small mirror ʼ, ārśī, ar˚ f. ʻ mirror ʼ.Addenda: ādarśá -- : S.kcch. ārīso m. ʻmirrorʼ, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) arśu m., J. ārśu.(CDIAL 1143) Ādāsa [Sk. ādarśa, ā + dṛś, P. dass, of dassati1 2] a mir- ror Vin ii. 107; D i. 7, 11 (˚pañha mirror -- questioning, cp. DA i. 97: "ādāse devataŋ otaretvā pañha -- pucchanaŋ"), 80; ii. 93 (dhamnaɔ -- ādāsaŋ nāma dhamma -- pariyāyaŋ desessāmi); S v. 357 (id.); A v. 92, 97 sq., 103; J i. 504; Dhs 617 (˚maṇḍala); Vism 591 (in simile); KhA 50 (˚daṇḍa) 237; DhA i. 226. -- tala the surface of the mirror, in similes at Vism 450, 456, 489(Pali) Ta. attam mirror (< Te.). Te. addamu mirror, pane of lass. Ga. (S.3 ) addam mirror. Go. (Ko.) addam id (Voc. 49). Konḍa adam id. Kuwi(F.) ademi id. / Cf. Pkt. addāa- mirror. (DEDR 147)

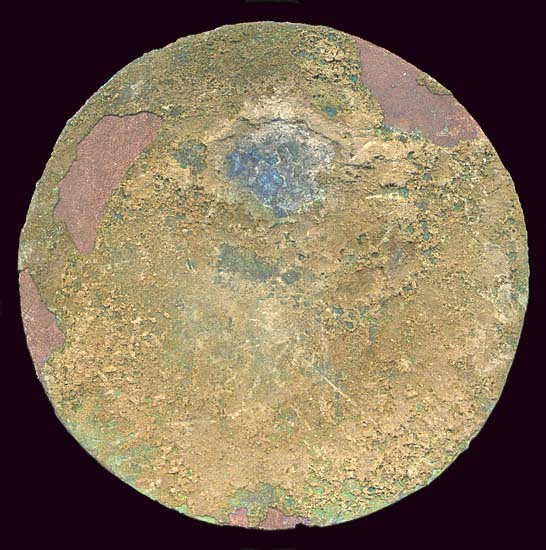

INDUS CULTURE, c. 2000-1000 BC, bronze mirror, 104mm dia., round, slightly dished, loop rivetted on on one side, hole for another rivet on the other, bull's eyes border on convex side, from Baluchistan,

INDUS or later, c. 1800-500 BC, bronze mirror, 93mm diameter, from Mehargarh, Balochistan, thin, corroded, bent.

INDUS CULTURE, c. 2000-1000 BC, bronze spoon or mirror, 85mm dia., 22x13mm tab for handle pierced with 2 holes, slightly dished ~4mm deep, from Loralai, cracked, tiny hole.

British Museum. Bronze mirror. ca. 300 BCE.

British Museum. Bronze mirror. ca. 300 BCE.https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/arth-2300-study-guide-2014-15-smith/deck/14134529

Sources of tin from Ancient Far East, the largest tin belt of the globe created the Tin-Bronze revolution

Lloyd R. Weeks presents a detailed and cogently argued thesis that tin bronzes of the third and second millennia in the early metallurgy of Persian Gulf points to sources of tin from the East. He posits possible sources from north and east in Afghanistan or Central Asia. However, he fails to resolve the archaeological fact that not many tin-bronzes have been found in Central Asia where there is predominant presence of tin-bronzes in sites such as Tell Abraq (Persian Gulf). (Weeks, Lloyd R., 2003,Early metallurgy of the Persian Gulf, Boston, Brill Academic Publishers Embedded for ready reference.)

https://www.scribd.com/document/363093182/Early-Metallurgy-of-the-Persian-Gulf-Lloyd-R-Weeks-2003

I agree with the analysis of TE Potts (Potts, TF, 1994, Mesopotamia and the East. An archaeological and historical stuydy of foreign relations ca. 3400-2000 BCE, Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 37, Oxford) that the tin for the tin-bronzes of ANE was sourced from the East. I further venture to posit that the tin came from the largest tin belt of the globe, through seafaring merchants of Ancient Far East (the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween) mediated by Ancient India trade guilds of 4th to 2nd millennia BCE. See. Maritime Meluhha Tin Road links Far East and Near East -- from Hanoi to Haifa creating the Bronze Age revolution https://tinyurl.com/y9sfw4f8 This hypothesis is a work in process.

https://www.scribd.com/document/363093182/Early-Metallurgy-of-the-Persian-Gulf-Lloyd-R-Weeks-2003

I agree with the analysis of TE Potts (Potts, TF, 1994, Mesopotamia and the East. An archaeological and historical stuydy of foreign relations ca. 3400-2000 BCE, Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 37, Oxford) that the tin for the tin-bronzes of ANE was sourced from the East. I further venture to posit that the tin came from the largest tin belt of the globe, through seafaring merchants of Ancient Far East (the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween) mediated by Ancient India trade guilds of 4th to 2nd millennia BCE. See. Maritime Meluhha Tin Road links Far East and Near East -- from Hanoi to Haifa creating the Bronze Age revolution https://tinyurl.com/y9sfw4f8 This hypothesis is a work in process.

Here is a small argument about the high tin-bronze of mirrors found in Barbar temple and in Sarasvati civilization areas mediated by the brilliant metalwmithy work of artisans from Mehi of Kulli Culture.

A bronze mirror is among the aṣṭamangala-s अष्ट-मङ्गलम् [अष्ट- गुणितं मङ्गलं शा. क. त.] a collection of eight auspicious things; according to some they are:-- मृगराजो वृषो नागः कलशो व्यञ्जनं तथा । वैजयन्ती तथा भेरी दीप इत्यष्टमङ्गलम् ॥ according to others लोके$स्मिन्मङ्गलान्यष्टौ ब्राह्मणो गौर्हुताशनः । हिरण्यं सर्पि- रादित्य आपो राजा तथाष्टमः ॥

Aranmuḷa metalwork by artisans are exemplified in high tin-bronze mirrors produced by Vishwakarma

വിശ്വകർമ്മജർ Using the cire perdue or lost-wax casting technique, a Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization tradition continues in a village of Kerala, Aranmula, by Visvakarma sthapatis who make high-tin bronze mirrors which are patented as Geographical Indicators and called āṟanmuḷakkaṇṇāṭi.

A tribute to the inventive genius of the Baluchistan metal-smiths of the period

Piggott, 1961, Prehistoric India, Harmondsworth, p. 112. Female figure with breasts, with arms akimbo. Compares with the handle of bronze mirror found in Barbar temple whish shows a male figure with arms joined on the chest in a worshipful pose.

Bronze mirror handle from Barbar Temple, Bahrain (After illustration by Glob, PV, 1954, Temples at Barbar, Kuml 4:142- 53, fig. 6) Another remarkable figure in bronze is a bird (After fig. 7 ibid.)

Kuml: Journal of the Jutland Archaeological Society

Nagaraja Rao notes that this handle resembles a mirror from the Kulli site of Mehi in Baluchistan.

(Stein, A., 1931, An archaeological tour in Gedrosia,Memoirs of ASI 43,: pi.32. Mehi II, 1.2.a; Possehl 1986: 48, Mehi II.1.2.a). These objects are similar to the head of the figure handle in the Mehi example is actually the face of the mirror itself. (Julian Reade, 2013, Indian Ocean in Antiquity, Routledge, p.26). These comments of Julian Reade have to be seen in the context of the artifacts with Indus Script hypertexts discovered in Kulli culture (Mehi). Kulli culture provides indication of working with magnetite, ferrite ore and with alloys of copper with high tin content resulting in the bronze mirrors. At Mehi were found several decorated chlorite vessels, imported from Tepe Yahya and attesting trade contacts with the Eastern Iran.[5]Copper and bronze was known. These are indications that Kulli culture artisans were trade partners with Sarasvati Civilization.

Source:

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280309195_Ancient_Metal_Mirror_Alloy_Revisited_Quasicrystalline_Nanoparticles_Observed

Metal mirror in casing

Optical micrograph revealing the microstructure to be composed of features at two different length scales: larger cells/dendrites with feature size > 70 nm (boundaries indicated by short arrows), and smaller rosette-shaped dendrites (centers indicatd y long arrows) contained within the larger features.

Ancient Metal Mirror Alloy Revisited: Quasicrystalline Nanoparticles Observed

Abstract

This article presents, for the first time, evidence of nanocrystalline structure, through direct transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations, in a Cu- 32 wt.% Sn alloy that has been made by an age-old, uniquely crafted casting process. This alloy has been used as a metal mirror for centuries. The TEM images also reveal five-sided projections of nano-particles. The convergent beam nano-diffraction patterns obtained from the nano-particles point to the nanophase being quasicrystalline, a feature that has never before been reported for a copper alloy, although there have been reports of the presence of icosahedral ‘clusters’ within large unit cell intermetallic phases. This observation has been substantiated by x-ray diffraction, wherein the observed peaks could be indexed to an icosahedral quasi-crystalline phase. The mirror alloy casting has been valued for its high hardness and high reflectance properties, both of which result from its unique internal microstructure that include nano-grains as well as quasi-crystallinity. We further postulate that this microstructure is a consequence of the raw materials used and the manufacturing process, including the choice of mold material. While the alloy consists primarily of copper and tin, impurity elements such as zinc, iron, sulfur, aluminum and nickel are also present, in individual amounts not exceeding one wt.%. It is believed that these trace impurities could have influenced the microstructure and, consequently, the properties of the metal mirror alloy.