-- Worship of purifying power of water, mother of Hindu civilization. Indus Script Corpora nclude Dilmun/Bahrain seals

This is an addendum to:

1. Itihāsa of Assur, metalsmiths of India, Ashur Ancient Near East. Two seals of Saar, Bahrain Indus Script hypertexts wealth-accounting metalwork ledgers https://tinyurl.com/ya5nzf6k

2. Itihāsa.Dilmun armourers, آهن ګران āhan-garān 'thunderbolt makers' of Sarasvati Civiliztion, Indus Script Meluhha Part 1 to 3 https://tinyurl.com/y7vsvtdm

3. Dilmun seals should be included in Indus Script Corpora, artisans and seafaring merchants of Sarasvati Civiization in Qal'at al-Bahrain, 2050 BCE

Background

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DV_5fI_9b3M (52:19)

Directed by Serge Tigneres, Tomomi Nagazawa

Script Serge Tigneres

Narrator: Simon Chilvers

Script and subtitles: George Burchett, Keith McLennan

The Indus Valley Civilisation Mohenjodaro and Harappa

Explorations since 1872 have revealed over 2000 archaeological sites (Rakhigarhi, Ropar, Banawali, Kalibangan, Bhirrana) of this civilization on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati (also called Ghaggar-Hakra-Nara) which had later dried up due to plate tectonics, resultant river migrations.

![Image result for sarasvati civilization satellite]()

![Image result for bronze age sites persian gulf]()

![Fig 3: map of steatite objects from the third to the first millennium B.C. in the Gulf (after Al-Duweesh 2015)]()

Map of steatite objects from the third to the first millennium B.C. in the Gulf (after Al-Duweesh 2015) https://mafkf.hypotheses.org/1311

Pour citer ce billet

Sultan Duwish, « Bronze Age Archaeological Sites in the Western Arabian Gulf: Synthesis and Comparisons », Le carnet de la MAFKF. Recherches archéologiques franco-koweïtiennes de l’île de Faïlaka (Koweït), 13 février 2016. [En ligne]

Growth of Indus Script Corpora to c. 30,000 inscriptions

In 1875, one Harappa seal discovered in 1872 was published by Cunningham

In 1977, Mahadevan concordance published 2856 Indus Script inscriptions from 5 major sites, 34 from other sites and 17 from West Asian sites:

In 2010, Vol. 3 of Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions was published. See: https://tinyurl.com/yb695goq Asko Parpola, 2018, Unicorn Bull and Victory Parade, in: Dennys Frenez et al, 2018, Walking with the Unicorn'

This third volume follows CISI I (1987) and CISI 2 (2991) and includes objects with inscriptions found by the Harappa Archaeological Research Project (HARP).

I agree with Asko Parpola that the motif of ‘unicorn bull’ was perhaps adopted by the Harappans from Mesopotamia, where it was represented on seals from the Late Uruk times (c. 3400-3100 BCE onwards.

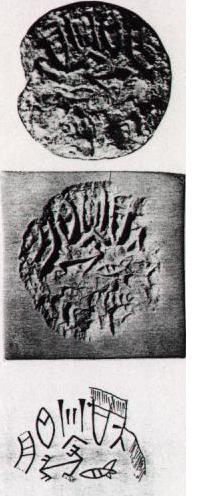

Impressions of two seals of the Proto-Elamite culture (c. 3200-2600 BCE). (After Amiet 1980: nos. 514 and 515).

Detail of the Mari Ishtar temple victory parade: thestand topped by the image of unicorn wild bull (excavationno. M-458), height 7cm. (After Parrot 1935: 134, fig. 15)

a

a)A procession of four men holding up stands topped by various things including a ‘unicorn’ bull. Terracotta tablet M-490 (HR 1443) from Mohenjo-daro; b) Terracotta tablet M-491 (HR 1546) from Mohenjo-daro; c) a unique tablet H-196 (262) from Harappa. After Asko Parpola Figure 6, 2018.

\ Corpus of Indus seals and inscriptions, volume 3 added 475 seals from Mohenjo-Daro and 1571 seals from Harappa.

Dilmun or Persian Gulf or Arabian Gulf seals have added to the Indus Script Corpora. In the Saar settlement, sixty five out of the ninety five retrieved seals (over 68%) were made of steatite.

Steffen Terp Laursen [Arab. arch. epig. 2010: 21: 96–134 (2010)] The westward transmission of Indus Valley sealing technology: origin and development of the ‘Gulf Type’ seal and other administrative technologies in Early Dilmun, c.2100–2000 BCE, lists 121 inscriptions of the so-called Dilmun or Gulf seals.

Elic Olijdamand Helen David-Cuny suggest that the total number of Gulf seals over a period of 250 years could have totalled over 24,000.

With these additions to Indus Script Corpora, the total number of Indus Script inscriptions now total nearly 30,000. Since all the inscrptions are wealth-acconting ledgers,metalwork catalogues, the contributions made by seafaring Meluhha merchants and artisans to the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 4th millennium BCE is significant, indeed and may explain the principal reasons for Ancient Bharat contributing to over 33% of World GDP in 1 CE (pace Angus Maddison).

a)A procession of four men holding up stands topped by various things including a ‘unicorn’ bull. Terracotta tablet M-490 (HR 1443) from Mohenjo-daro; b) Terracotta tablet M-491 (HR 1546) from Mohenjo-daro; c) a unique tablet H-196 (262) from Harappa. After Asko Parpola Figure 6, 2018.

\ Corpus of Indus seals and inscriptions, volume 3 added 475 seals from Mohenjo-Daro and 1571 seals from Harappa.

Dilmun or Persian Gulf or Arabian Gulf seals have added to the Indus Script Corpora. In the Saar settlement, sixty five out of the ninety five retrieved seals (over 68%) were made of steatite.

Steffen Terp Laursen [Arab. arch. epig. 2010: 21: 96–134 (2010)] The westward transmission of Indus Valley sealing technology: origin and development of the ‘Gulf Type’ seal and other administrative technologies in Early Dilmun, c.2100–2000 BCE, lists 121 inscriptions of the so-called Dilmun or Gulf seals.

Elic Olijdamand Helen David-Cuny suggest that the total number of Gulf seals over a period of 250 years could have totalled over 24,000.

With these additions to Indus Script Corpora, the total number of Indus Script inscriptions now total nearly 30,000. Since all the inscrptions are wealth-acconting ledgers,metalwork catalogues, the contributions made by seafaring Meluhha merchants and artisans to the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 4th millennium BCE is significant, indeed and may explain the principal reasons for Ancient Bharat contributing to over 33% of World GDP in 1 CE (pace Angus Maddison).

Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Vol. 3.1

OCLC:

Volume 3.1 Mohenjo-daro and Harappa of the most comprehensive listing of ancient Indus seals includes new material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan.

Edited by ASKO PARPOLA, B. M. PANDE, and PETTERI KOSKIKALLIO, in collaboration with RICHARD H. MEADOW and J. MARK KENOYER

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Sarja, Series B, NIDE, vol. 359

Memories of the Archaeological Survey of India, vol. 96. Helsinki, 2010.

Pp. lx + 444, photographs, line drawings, and tablets.

![Page [129] of The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late Third Millennium Mesopotamia?]()

Edited by ASKO PARPOLA, B. M. PANDE, and PETTERI KOSKIKALLIO, in collaboration with RICHARD H. MEADOW and J. MARK KENOYER

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, Sarja, Series B, NIDE, vol. 359

Memories of the Archaeological Survey of India, vol. 96. Helsinki, 2010.

Pp. lx + 444, photographs, line drawings, and tablets.

Cuneiform texts attest to the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer. [The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late ThirdMillennium Mesopotamia?Author(s): Simo Parpola, Asko Parpola, Robert H. Brunswig, Jr.Source:Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 20, No. 2 (May, 1977),pp. 129-165].

[quote] MAGAN and MELUHHA Geographical terms for regions in the distant south and southeast of Mesopotamia. Both names first appear in royal inscriptions of the Akkad period; “ships from Magan and Meluhha” were said to have brought goods to the quays of Akkad and other cities. It has been proposed that Magan referred to the coast of Oman along the Persian Gulf, rich in copper and dates, and Meluhha in the Indus valley. In Neo-Assyrian texts of the first millennium B.C., Magan and Meluhha probably designated the African coast of the Red Sea (Upper Egypt and Sudan). --Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia[unquote]

The major contribution made by Meluhhans in Sumer was tin as an alloying mineral to create tin-bronzes (to complement naturally-occurring copper + arsenic ores for arsenic bronzes).

Meluhhan artisans in Sumer used Indus writing to create metal-ware catalogs. This is exemplified by the 'water-buffalo' glyph used on some cylinder seals. rango 'water buffalo' Rebus: rango ‘pewter’. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali). Hieroglyhph: buffalo: Ku. N. rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ (or < raṅku -- ?).(CDIAL 10538, 10559) Rebus: raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf. nāga -- 2 , vaṅga -- 1 ] Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10567)

"The adaptation of Harappan motifs and script to the Dilmun seal form may be a further indication of the acculturative phenomenon, one indicated in Mesopotamia by the adaptation of Harappan traits to the cylinder seal." (Robert H. Brunswig, Jr. et al, 1983, New Indus Type and Related Seals from the Near East, 101-115 in: Daniel T. Potts (ed.), Dilmun: New Studies in the Archaeology and Early History of Bahrain, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1983; each seal is referenced by a four-digit number which is registered in the Finnish concordance.)

The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late Third Millennium Mesopotamia?

Simo Parpola, Asko Parpola and Robert H. Brunswig, Jr.

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient

Vol. 20, No. 2 (May, 1977), pp. 129-165

Published by: Brill

DOI: 10.2307/3631775

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3631775

Thousands of seals have been found with over 400 recurring signs; discovery of the oldest signboard in the world of Dholavira; seafaring Meluhha merchants in Persian Gulf (30:23, 31:11; 31"50 to 36:10; 43:20)

Umm al-Nar (Arabic: أُمّ الـنَّـار, translit. Umm an-Nār, lit. 'Mother of the Fire') is the name given to a Bronze age culture that existed around 2600-2000 BCE in the area of modern-day United Arab Emirates and Northern Oman. The etymology derives from the island of the same name which lies adjacent to Abu Dhabi and which provided early evidence and finds attributed to the period.

117 antelope; sun motif. Dholavira seal impression. arka 'sun' Rebus: araka, eraka 'copper, moltencast' PLUS करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. Thus, together, the rebus message: hard alloy of copper.

117 antelope; sun motif. Dholavira seal impression. arka 'sun' Rebus: araka, eraka 'copper, moltencast' PLUS करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. Thus, together, the rebus message: hard alloy of copper.  Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.

Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

I suggest that this hieroglyph of a kid becomes the Dilmun standard with the kid shown with its head turned backwards to signify krammara'turn backwrds' rebus: kamar'blacksmith'.

m417 Glyph: ‘ladder’: H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ Rebus: Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. The lexeme in Tamil means: Limit, boundary; எல்லை. நளியிரு முந்நீரேணி யாக (புறநா. 35, 1). Country, territory.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work.

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjaerum, The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjaerum, The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Many of the bronze-age manufactured or industrial goods were surplus to the needs of the producing community and had to be traded, together with a record of types of goods and types of processes such as native metal or minerals, smelting of minerals, alloying of metals using two or more minerals, casting ingots, forging and turning metal into shapes such as plates or vessels, using anvils, cire perdue technique for creating bronze statues – in addition to the production of artifacts such as bangles and ornaments made of śankha or shell (turbinella pyrum), semi-precious stones, gold or silver beads. Thus writing was invented to maintain production-cum-trade accounts, to cope with the economic imperative of bronze age technological advances to take the artisans of guilds into the stage of an industrial production-cum-trading community.

Tablets and seals inscribed with hieroglyphs, together with the process of creating seal impressions took inventory lists to the next stage of trading property items using bills of lading of trade loads of industrial goods. Such bills of lading describing trade loads were created using tablets and seals with the invention of writing based on phonetics and semantics of language – the hallmark of Indian hieroglyphs.

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Many of the bronze-age manufactured or industrial goods were surplus to the needs of the producing community and had to be traded, together with a record of types of goods and types of processes such as native metal or minerals, smelting of minerals, alloying of metals using two or more minerals, casting ingots, forging and turning metal into shapes such as plates or vessels, using anvils, cire perdue technique for creating bronze statues – in addition to the production of artifacts such as bangles and ornaments made of śankha or shell (turbinella pyrum), semi-precious stones, gold or silver beads. Thus writing was invented to maintain production-cum-trade accounts, to cope with the economic imperative of bronze age technological advances to take the artisans of guilds into the stage of an industrial production-cum-trading community.

Tablets and seals inscribed with hieroglyphs, together with the process of creating seal impressions took inventory lists to the next stage of trading property items using bills of lading of trade loads of industrial goods. Such bills of lading describing trade loads were created using tablets and seals with the invention of writing based on phonetics and semantics of language – the hallmark of Indian hieroglyphs.

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy).

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy). 9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'. Thus, cast metal ingot. (Next two hieroglyhphs not legible).![]()

![]() 9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' PLUS kANDa 'notch' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; ayas 'fish' aduru' native metal' (unsmelted) eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast' arA 'spokes' Rebus: Ara 'brass'.![]() Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'![]() 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.![]()

![]() 9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

![]() 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'![]() 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

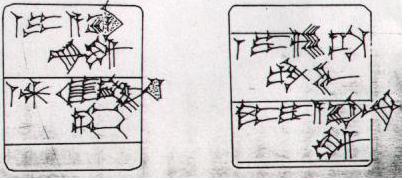

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.![]() Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

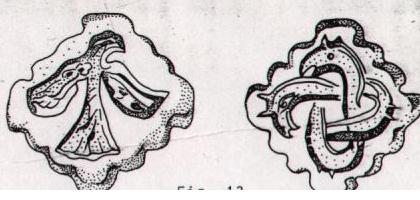

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)![]() Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

![]() 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'![]() Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron' 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'. 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze' 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim) Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.Hieroglyph: meṇḍā ʻlump, clotʼ (Oriya)

On mED 'copper' in Eurasian languages:

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

Meluhha acculturation in Ancient Near East

Many scholars have noted the contacts between the Mesopotamian and Sarasvati-Sindhu (Indus, Hindu) Civilizations, in terms of cultural history, chronology, artefacts (beads, jewellery), pottery and seals found from archaeological sites in the two areas.

"...the four examples of round seals found in Mohenjodaro show well-supported sequences, whereas the three from Mesopotamia show sequences of signs not paralleled elsewhere in the Indus Script. But the ordinary square seals found in Mesopotamia show the normal Mohenjodaro sequences. In other words, the square seals are in the Indian language, and were probably imported in the course of trade; while the circular seals, although in the Indus script, are in a different language, and were probably manufactured in Mesopotamia for a Sumerian- or Semitic-speaking person of Indian descent..." [G.R. Hunter,1932. Mohenjodaro--Indus Epigraphy, JRAS: 466-503]

The acculturation of Meluhhans (probably, Indus people) residing in Mesopotamia in the late third and early second millennium BC, is noted by their adoption of Sumerian names (Parpola, Parpola and Brunswig 1977: 155-159).

Image 2 below: Right: A single Seal from Falaika Bears an Inscription in the Unread Indus Script. Left: From one of the Falaika Seals. A Man Holds a Monkey at Arm's Length; Monkeys were Imported as Pets from Meluha. (Bibby, pp. 253, 211).

Image 2 below: Right: A single Seal from Falaika Bears an Inscription in the Unread Indus Script. Left: From one of the Falaika Seals. A Man Holds a Monkey at Arm's Length; Monkeys were Imported as Pets from Meluha. (Bibby, pp. 253, 211).  Failaka seal; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

Failaka seal; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'. This is the image of the first seal and a seal impression which has stimulated the spectacular discoveries of the roots of Hindu Civilization along the banks of River Sarasvati adored in 72 r̥ca-s in the R̥gveda spanning an contact area from Hanoi (Vietnam) to Haifa (Israel), along an ancient Maritime Tin Route which powered the Tin-Bronze Revolution from ca. 5th millennium BCE.

This is the image of the first seal and a seal impression which has stimulated the spectacular discoveries of the roots of Hindu Civilization along the banks of River Sarasvati adored in 72 r̥ca-s in the R̥gveda spanning an contact area from Hanoi (Vietnam) to Haifa (Israel), along an ancient Maritime Tin Route which powered the Tin-Bronze Revolution from ca. 5th millennium BCE.Seal discovered in Harappa by Major Clarke before 1872; given to the British Museum in 1886.

[quote]Sir Alexander Cunningham, who led the first excavations there in 1872-73 and published news of the seal, wrote 50 years before we understood that the Indus civilization had existed: "The most curious object discovered at Harappa is a seal, ... The seal is a smooth black stone without polish. On it is engraved very deeply a bull, without a hump, looking to the right, with two stars under the neck. Above the bull there is an inscription in six characters, which are quite unknown to me. They are certainly not Indian letters; and as the bull which accompanies them is without a hump, I conclude that the seal is foreign to India." How wrong Cunningham was about the seal! Still, as Neil MacGregor writes, "it was this seal that stimulated the discovery of the entire Indus civilization." (A History of the World in 100 Objects, p. 80). It was left to a successor, John Marshall, to announce the discovery of the ancient Indus civilization. [unquote] https://www.harappa.com/blog/first-seal

One house in Mohenjo-daro, said to be a temple, revealed 12 objects with Indus Script Inscriptions.

Michael Jansen’s analysis of house 1 in the HR-A area of Mohenjo-daro.. After Jansen 1986:200:91, fig. 125; a) isometry; (b) distribution of the seal finds, Courtesy: Michael Jansen.

Twelve Indus Script imetalwork catalogues from one Mohenjo-daro house -- kole.l 'smithy/forge' guild artisans of kole.l 'temple' http://tinyurl.com/glaltdl

All seven seals out of the 12 inscriptions depicted the same animal 'one-horned young bull in front of a standard device'

Hieroglyph: sãgaḍ, 'lathe' (Meluhha) Rebus 1: sãgaṛh , 'fortification' (Meluhha). Rebus 2:sanghAta 'adamantine glue'. Rebus 3:

sangāṭh संगाठ् 'assembly, collection'. Rebus 4: sãgaḍa 'double-canoe, catamaran'.

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf.

Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving.

The inscriptions on the seven seals and five tablets are:

khaNDa 'arrow' rebus:khaNDa 'implements'

muka 'ladle' rebus:muhA 'quantity of smelted metal produced from a furnace' PLUS baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' PLUS aDaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'unsmelte metal' muh 'ingot' PLUS kolom 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' muh 'ingot' PLUS baTa 'quail' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'. Thus, the inscription on the seal signifies: workshop smithy/forge with furnace working to produce metal castings, ingots, implements, iron, unsmelted ore.

karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl 'curve' kuṭila 'bent' CDIAL 3230 Rebus: kuTila 'bronze' (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin).. Thus, a bronze worker handing over produce to the Supercargo as shipment.

karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' kole.l 'temple' rebus:kole.l 'smithy, forge' kaNDa 'backbone' rebus:khaNDa 'implements' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge' muh 'ingot' Thus, Supercargo from smithy, forge, implements, ingots workshop of smithy/forge.

karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' muh 'ingot' PLUS khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. Thus, Supercargo of metal ingots, implements.

Thus, it is seen that all the 12 inscriptions are metalwork catalogues of artisans of the guild preparing products (ingots, implements) for shipment to be handed to Supercargo responsible for the cargo.

The building HR1 was thus a smithy, forge. kole.l signified 'smithy/forge'. The same word kole.l also signified 'temple'. Thus, all the artisans at work documenting 12 inscriptions were members of the smithy/forge guild which was the temple.

"Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was an officer of the Royal engineers. He came to India in 1831. Since his arrival in the country, he devoted his time to the study of the ancient remains of Indian history. Alexander Cunningham recorded the existence of a series of mounds after visiting Harappan site. He is credited to have conducted a limited excavation of the Harappan site. He published a few Objects (such as seals) as well as the site-plan. He was appointed Archeological Surveyor in 1861." http://deepak-indianhistory.blogspot.com/2011/05/sir-alexander-cunningham-father-of.html The position was terminated in 1865 due to lack of funds. (Cotton, J. S. & James Lunt (reviser) (2004). "Cunningham, Sir Alexander (1814–1893)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.)

"Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was an officer of the Royal engineers. He came to India in 1831. Since his arrival in the country, he devoted his time to the study of the ancient remains of Indian history. Alexander Cunningham recorded the existence of a series of mounds after visiting Harappan site. He is credited to have conducted a limited excavation of the Harappan site. He published a few Objects (such as seals) as well as the site-plan. He was appointed Archeological Surveyor in 1861." http://deepak-indianhistory.blogspot.com/2011/05/sir-alexander-cunningham-father-of.html The position was terminated in 1865 due to lack of funds. (Cotton, J. S. & James Lunt (reviser) (2004). "Cunningham, Sir Alexander (1814–1893)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.) ""Since the first publication of material in 1872, the site of Harappa has provided focus for protohistoric archaeological investigations in the Punjab region of northwestern South Asia. The current University of California, Berkeley, project us here put into context of earlier work at the site and into the context of the history of archaeology in the Greater Indus Valley as a whole.""(Gregory L. Possehl, A short history of archaeological discovery at Harappa, in: Richard H. Meadow (ed.), Harappa Excavations 1986-1990 – a multidisciplinary approach to third millennium urbanism, Madison, Wisconsin, Prehistory Press, pp. 5 to 12)

""Since the first publication of material in 1872, the site of Harappa has provided focus for protohistoric archaeological investigations in the Punjab region of northwestern South Asia. The current University of California, Berkeley, project us here put into context of earlier work at the site and into the context of the history of archaeology in the Greater Indus Valley as a whole.""(Gregory L. Possehl, A short history of archaeological discovery at Harappa, in: Richard H. Meadow (ed.), Harappa Excavations 1986-1990 – a multidisciplinary approach to third millennium urbanism, Madison, Wisconsin, Prehistory Press, pp. 5 to 12) [quote]In 1924 the objects found at Mohenjo-daro were compared with some found at Harappa. Many objects were so similar in material and construction that the archaeologists believed they might have been made by people sharing the same culture.

The work at Mohenjo-daro was successful. The possibility that objects from the site might be related to those from Harappa was exciting for the archaeologists. The next step was to explore the site more completely. So large-scale excavations were planned for Mohenjo-daro under the guidance of Sir John Marshall who was the Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Excavations continued throughout the 1920s and 1930s with several teams of excavators. During this period, the site was divided into different areas. Each area was given a 'title' based on the name of the archaeologist working there.

HR Area = Harold Hargreaves

DK Area = Kashinath Narayan Dikshit

L Area = Ernest J.H. Mackay

VS Area = Madho Sarup Vats

SD Area = A.D. Siddiqi [unquote] http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/time/explore/iv_discseal.html