Plan: Sun Temple, Konarak

Plan: Sun Temple, KonarakKonarak temple building accounts. The palm leaf manuscripts were discovered by an scholars, Alice Boner and SR Sarma.

Madala Panji contradicts some details provided by Alice Boner and SR Sarma. The unreliability of the mss. discovered by Alice Boner and SR Sarma is discussed in detail by K.S. Behera: 'Palm-leaf manuscript on the Architecture of Konark Temple', ABORI, Vol. LVII, pts. I-IV, pp. 176-180.

In Orissa in eastern India, there is left an ancient text entitled gShilpa Prakasha,hwhich uncommonly holds the authorfs name, Ramachandra Kaulachara, architect. It was written in Sanskrit on palm leaves, providing the details about the Orissan Style...

According to the manuscripts written on palm leaves, Brahmin priests took important roles at cardinal points during the temple construction, deciding the location of the building and construction dates, performing a ceremony to remove obstructions, celebrating the installation of the Kalasha (pot-like finial) on the roof top, and so on. Their opinions were also likely to have been solicited in deciding the locations of sculptures on the walls.

http://www.kamit.jp/02_unesco/09_konarak/kon_eng.htm

See: http://ccrtindia.gov.in/templearchitecture.htm Konarak temple. The designer’s sketch of the proposed temple on 9 ola leaves.

Konarak temple. The designer’s sketch of the proposed temple on 9 ola leaves.

World Heritage Sites - Konarak - Sun Temple - Introduction

Introduction

Konarak is a village located at a distance of 66 km from Bhubaneswar, the capital of Orissa and is famous for the Sun Temple, which marks the highest point of achievement in the temple construction of Kalinga order in Orissa. The Sun Temple, even in the ruined form presents a majestic appearance in the midst of vast stretch of sand. The name is after the presiding deity Konarka, the meaning of which is Arka (Sun) of kona (corner). The European travellers called the main temple as ‘Black Pagoda’ while the Puri Temple was known as ‘White Pagoda’, probably due to the colour of these temples when viewed from a distance from the coast. The black colour of Sun Temple could be due to the accumulation of moss, lichen and other fungal growth which turned the surface of the temple into black colour.

The legends attribute the temple to the Puranic age, and references are found in the Bhavishya and Samba Purana. This tradition is carried forward in the Kapila-Samhita, the Madala-panji (chronicle of the Jagannatha temple of Puri) and the Prachi-mahatmya. The traditions attribute the construction of the temple to Samba, the son of Lord Krishna, who after a curse suffering from leprosy, did a severe penance for twelve years to get himself cured. Samba cured of his illness by the god, decided to construct the temple, and took a holy dip in Chandrabhaga and discovered the image of god, which was fashioned out of Surya’s body by Visvakarma. The tradition also attributes that Samba installed this image in the temple built by him in Mitravana.

The unpublished manuscript of Madala-panji mentions that a temple of Konarka-deva was constructed by one Purandara-kesari of Kesari dynasty in the Arka-khsetra. The Ganga dynasty, which succeeded the Kesaris and Narasimhadeva, the son of Anangabhima constructed a temple in front of the temple built by Purandara-kesari and installed the image in the new temple. Narasimhadeva caused this new temple to relieve his father’s sin by not fulfilling the promise made to the God of Puri to enlarge the temple. Even though the tradition attributed in the Matala-panji is not reliable, the ground evidence at Konarak indicates that the main temple is constructed in front of a smaller temple, which might mark the location of the temple constructed by Purandara-kesari. The copper plates of the successors of Ganga king Narasimhadeva (ca. 1238-1264) too mention Narasimha as the builder of a mahat-kutira (great cottage) of Ushnarasmi (Surya) in the corner of Trikona (Trikona-kone kutirakam-achikarad-Ushnarasmeh). The identification of Purandara-kesari is also doubtful. Some scholars feel that Purandara-kesari may be identifiable with Somavamsi Puranjaya (7th century A.D.) grandson of Udyotakesari and brother of Karna.

The reason for selection of this site is not known. The temple for Sun could have been constructed because he is believed to the healer of diseases and bestower of wishes from very early times. The temple became very much popular during later times and the Vaishnavite saint Chaitanya (1486-1533 A.D.) visited the temple. Abu’l Fazl also mentions the temple in his A’in-i-Akbari. Abu’l Fazl describes the temple in details, but not its destruction or state of preservation. It indicates that during that time the temple was in good condition and did not face any destruction. The Madala-panji also mentions that in 1628 A.D. the temple was visited by Maharaja Narasimhadeva, the third king of Bhoi dynasty of Khurda, when Bakhar Khan was ruling the suba of Orissa on behalf of Shah Jahan.

The Marathas during the 18th century removed the Aruna-stambha made of chlorite and placed it in front of the Puri temple. The exact cause of the collapse of the main sikhara is also not fully understood. Various speculations have been made and various causes have been attributed to its collapse, like the damage caused due to an earthquake, loose foundation and settlement and non-completion of the temple itself. The last theory has been discarded by the scholars. Evidence for uneven settlement of plinth or sagging foundation is also not available and hence it is generally agreed that after the temple fell into disuse, the damage was caused gradually and slowly. The periodic structural repairs which were necessary could not be made after the desecration of the temple and hence the stone elements, particularly the massive amalaka and the khapura members could have created heavy load over the superstructure and caused the deterioration to advance rapidly. The fact that the decay and collapse was gradual is substantiated by A. Stirling, who visited the site in 1825 A.D. who mentions that the temple still stands, even in 1848, and a corner of the rekha sikhara remained to a considerable height.

The standing corner of the tower was further recorded by James Fergusson in 1837 A.D. who estimates its height as 140 to 150 feet (nearly 45 m) and Kittoe in 1838 A.D. who estimates its height as 80 or 100 feet (ranging between 24 and 30 m). This solitary remnant of the main temple also fell in October 1848 due to a strong gale. The visit of Rajendralala in 1868 mentions it as only an “enormous mass of stones studded with a few papal trees here and there”.

http://asi.nic.in/asi_monu_whs_konark_intro.asp

April 28, 2013

Ever learning something new

S. MUTHIAH

I’ve always maintained that I learn something new every day and never has it been truer than on one recent day when the Department of Civil Engineering, IIT-Madras, celebrated World Heritage Day. I was delighted to discover that the Department was celebrating the day with the first of what it intended to be an Annual Lecture series and that it planned to establish before long, a section that would focus on methods to conserve heritage structures. That first lecture, from which my new learning came, was delivered by Prof. R. N. Iyengar who is, appropriately, given the disastrous state our heritage structures are in, titled the Director of the Centre for Disaster Mitigation, at the Jain University, Bangalore!

What was, however, a bit sad to see on the occasion was that, given a student strength of 800 in the Department and a faculty strength of 50, there were only around 75 persons in the audience. Is that a reflection of interest (or lack of it) in heritage or learning?

But those who were fortunate enough to be present were sure to have discovered, like I did, a couple of off-repeated theories turned on their head. I had just finished repeating what I have said at various fora, namely that there has been no recording of ancient Indian engineering techniques in raising buildings such as the Brihadeeswarar Temple or of the ancient techniques of manufacturing materials used in such buildings, like what is called Madras/Chettinad ‘cement,’ when Dr. Iyengar pointed out that while this was, by and large, the case, there had, in fact, been some recording. And two of these records were the focus of his lecture.

He first presented a detailed description of the “Method of Making the Best Mortar of Madras in East India.” This was reported in an article that appeared in a publication of the Royal Society, London, in 1731-32 and had been written by Isaac Pyke, Governor of St. Helena, in a letter to Edmund Halley, ‘the comet man.’ But while the five-page letter is full of detail, it is short of quantities in some places. And this has been the problem over the years.

Artisans who have successfully plastered buildings with this mortar 100-200 years ago, have not passed down scientific formulas of its mixing. Those who have followed them to this day have only vague ideas about the formulas they had been told about and, working by trial and error, produce mortar that neither gives the same mirror-finish as in the past nor can they get it to last for more than 5-10 years. Now here at last is a recorded formula that perhaps the IIT students could, through research, get to work as Madras /Chettinad cement has in the past. In the formula is a ‘secret’ ingredient that I had not come across in other versions of it that maistries have orally spoken of or recorded in interviews and that is ‘toddy’ (presumably palmyrah toddy, but, again, fermented for how long?).

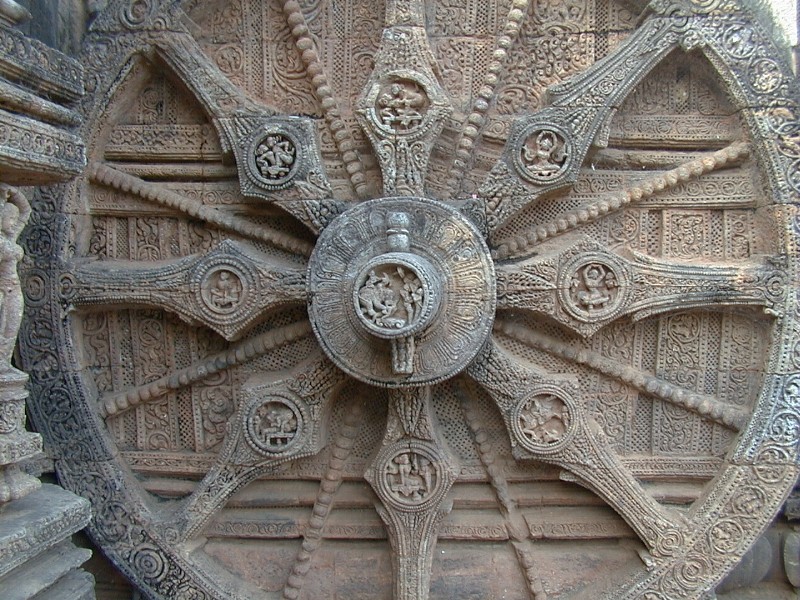

The other surprise that Dr. Iyengar sprang was the information that a Swiss Indologist-cum-researcher-cum-artist who had lived in Benaras from 1936 till 1978 had found olas (palm leaf manuscripts) with considerable details of the raising of the Konarak Sun Temple built c.1250 and records about many who worked on it, from the Superintendent of Works and Chief Sthapathi down to the humblest carpenter, mason and helper. A complete drawing of the temple has been done in NINE olas! These olas are in the Alice Boner Gallery of Benaras Hindu University’s Bharat Kala Bhavan at present.

‘Now the question arises, if such scribed recording had been done in the 13th Century, they could very well have been done for the Brihadeswara Temple, Srirangam and other major shrines. What happened to all those records? What a debate the answer to that question would make! Dr. Iyengar stated, “In India, the climate rapidly destroys anything remotely perishable, and over the course of centuries much of what did not succumb to climate was intentionally destroyed during the various foreign invasions and endless strife between local contending kingdoms.” Is that the answer?

The I.C.S. educationist

On the main highway from Madras to Calcutta, in northern Nellore District and midway between Nellore and Ongole, is a town called Kavali that I’ve just discovered is a major centre of education and a supplier to the U.S. of a considerable amount of Andhra talent. It is also a major textile centre. And Potti Sreeramulu was from the town.

Its roots in the education field were sunk, I’m told by reader S.B. Prabhakar Rao, by Alfred Tampoe (Miscellany, April 22) among others. He was a brilliant English teacher and a much-loved Principal, recalls Prabhakar Rao who had been one of his students. Tampoe was one of the founders of an NGO called Visvodaya that was established in 1952 to focus on education. Others in the founding group were Justice P.V. Rajamannar and Debi Prasad Chowdhury of the Madras School of Arts and Crafts. Chowdhury was a particular friend of Tampoe and did three ‘heads’ of him, according to my correspondent, who adds that one of them is still in the College of Arts. Visvodaya took over Kavali College, founded the year before, and named it Jawahar Bharati College. Tampoe became its Principal in 1954. He is remembered there in the college library that is called the Tampoe Library.

Tampoe, who was Principal till 1962, came to it from government service after he had resigned as Education Secretary, following differences with Chief Minister Rajaji, recalls Prabhakar Rao. He also remembers visiting Tampoe in his Rundall’s Road home and, later, Chamier’s Road flat.

I’ve also discovered that Tampoe wrote two books. Life Negation: A Study of Christ was published in the U.K. in 1939 and reprinted in 1950. The Problem of Good was published in 1961. I’m now waiting to discover what his differences with Rajaji could have been other than, possibly, two highly principled and disciplined personalities each sticking to his own convictions.

When the postman knocked

Bharati's complete works (Miscellany, April 15) were published in three volumes in January 2004, reader K.V. Ramanathan tells me. Varadhamanan Padippagam of T.Nagar issued them as Bharati’s stories, Bharati’s essays/articles and Bharati’s poetry, pricing each volume at Rs.60. A companion volume published at the time was Va Raa’s Mahakavi Bharatiar, a biographypriced at Rs.20. Even at those prices, I wonder how many copies sold in this State where politicians daily sing of pride in the language. Adding a footnote to my wondering how many really remember the great poet and patriot, reader Mani Nataraajan tells me a senior advocate of the Madras High Court, K. Ravi, has, for the past 15 years, been organising a three-day meet every December to keep alive the memory of Bharati. The meet is held under the aegis of Vanavil Panpaattu Maiyam, a cultural group started by Ravi. And so we find one more in the city trying to keep the memory of Bharati and his work alive. I wonder how many others there are.

Reader T.M. Sundararaman tells me that Kalki had in Ponniyin Selvan written all about the grant of the village of Anaimangalam for the upkeep of the Buddhist vihara in Nagapattinam and mentioned the copper plates recording the grant (Miscellany, April 15). All this, however, sheds no light on how these plates got to Leiden in Holland. Did the Dutch find them in Nagapattinam, which was capital of the Dutch Coromandel from 1660 to 1781?

There have been several calls and letters wondering whether Shobhaa Dé had been fair by the Seths of the world in titling her latest novel Sethji (Miscellany, April 15). But the most anguished letter has come from Umrao Singh Sethia who writes, “My family bears the title ‘Sethia’ which was bestowed on our ancestors by Akbar the Great and my great-great-grandfather was titled ‘Sethji’ by Maharajah Takat Singhji of Marwar (Jodhpur).” He wants to, therefore, protest against the way Shobhaa Dé has used the name ‘Sethji.’ “May our voice (a family website is to be started shortly, he tells me) not remain a voice in the wilderness.”

http://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/ever-learning-something-new/article4663237.ece?homepage=true

Architectural Description of Konark Sun-Temple

Debaprasad Bandyopadhyay

Indian Statistical Institute

October 1, 2011

Loukik, IV:1-2, pp.111-121, Sumahan Bandyopadhyay, ed., ISSN 2230-780X

Abstract:

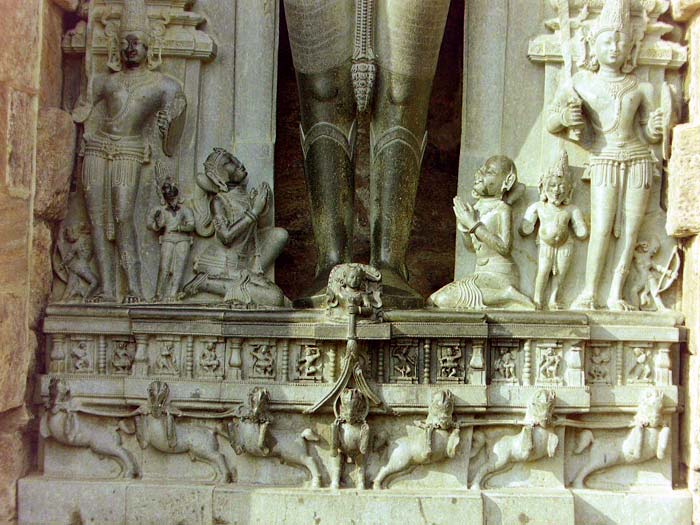

In case of interpreting the Konark sun temple’s architecture (Orissa, India), there are two divergent as well as antithetical views. Nirmal kumar Bose (1926, 1932) interpreted the outer body of this temple and Stella Kramrisch (1946) was searching the inner body. The main point of their disagreement might be posed as : Were the bodies of the Hindu temples constructed on the basis of physiological corporeal or meta- physiological conjecture of body? Bose reviewed Kramrisch’s book (1947) and alleged that Stella was too metaphysical and illiterate artisans are ignorant about the intricacies of the inner body as they did not have the access to the scriptures. However, Mira Mukherjee(1993) showed the path when she introduced so-called illiterate sons of Visvakarma. The author of this paper showed the evidences of inner corporeal of the temple-architecture by re-surveying the temple and taking cue from sub-altern artisans’ world-views as well as from Mandukyoponisad, Vakyapadiya and Tantraloka.

Note: Downloadable Document is in Arabic.

Number of Pages in PDF File: 7

Keywords: episteme, discourse, inner and outer corporeal, orientalism, Indian philosophy, sons of Visvakarma

Accepted Paper Series

Date posted: April 3, 2012

Suggested Citation