Abstract

Elaborating on Denise Schmandt-Besserat’s observation that “art became narrative and went beyond accounting to become a comprehensive medium of communication,” three artifacts discussed in this note point to the use of hieroglyphs to communicate substantive information on the life-activities of artisans of the bronze age. The literate communication occurred using the rebus renderings of select substrate meluhha words of glosses from Indian sprachbund, for select glyphs deployed in Indus writing which can be attributed to artisans of Meluhha settlements in ancient Near East. Two bowls discovered by Ernst Herzfeld in the 1911-1914 campaign at Samarra and Warka vase of ancient Sumer (one of a pair) stolen in April 2003 and recovered in June 2003 for the Iraqi museum provide the evidence for identifying hieroglyphs read rebus. Cuneiform texts attest to the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer. While cuneiform was deployed to denote names or benedictions to superiors, glyphs of Indus writing continued to be used on hundreds of cylinder seals and other artifacts such as Samarra bowls or Warka vase.

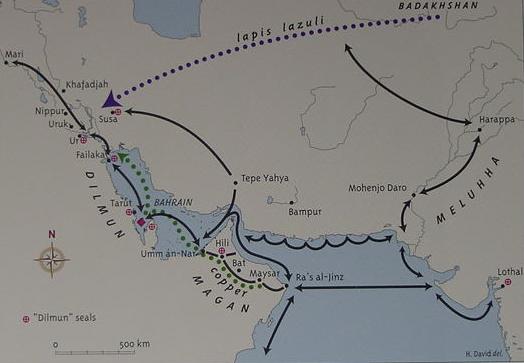

Ancient Near East and Meluhha interaction area

[quote] MAGAN and MELUHHA Geographical terms for regions in the distant south and southeast of Mesopotamia. Both names first appear in royal inscriptions of the Akkad period; “ships from Magan and Meluhha” were said to have brought goods to the quays of Akkad and other cities. It has been proposed that Magan referred to the coast of Oman along the Persian Gulf, rich in copper and dates, and Meluhha in the Indus valley. In Neo-Assyrian texts of the first millennium B.C., Magan and Meluhha probably designated the African coast of the Red Sea (Upper Egypt and Sudan). [unquote]

The major contribution made by Meluhhans in Sumer was tin and zinc as alloying minerals to create tin-, zinc-bronzes (to complement naturally-occurring copper + arsenic ores for arsenic bronzes).

Meluhhan artisans in Sumer used Indus writing to create metal-ware catalogs.

Meluhhan settlements in ancient Near East have been discussed. Rebus readings are based on substrate lexemes of Indian sprachbund, a contact region.with pronounced bronze-age contributions of creating alloys with tin and zinc.

Hieroglyphs of two Samarra bowls and Warka vase

Image 1. Eight fish, four peacocks holding four fish, slanting strokes surround

Image 1. Eight fish, four peacocks holding four fish, slanting strokes surround Image 2. Six women, curl in hair, six scorpions

Image 2. Six women, curl in hair, six scorpions

Image 3. Warka vase . Antelope, ingot tiger, ingot, face of bull, procession of bovidae, tabernae Montana stalks

Image 3. Warka vase . Antelope, ingot tiger, ingot, face of bull, procession of bovidae, tabernae Montana stalksRebus readings of hieroglyphs which also recur on Indus writing corpora :

dhāḷ ‘a slope’; ‘inclination of a plane’ (G.); dhāḷako ‘large metal ingot’ (G.)

ayo ‘fish’; rebus: ayas ‘metal’

mora peacock; morā ‘peafowl’ (Hindi); rebus: morakkhaka loha, a kind of copper, grouped with pisācaloha (Pali). moraka "a kind of steel" (Sanskrit)

gaṇḍa set of four (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali)

मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). S. mī˜ḍhī f., °ḍho m. ʻ braid in a woman's hair ʼ, L. mē̃ḍhī f.; G. mĩḍlɔ, miḍ° m. ʻbraid of hair on a girl's forehead ʼ (CDIAL 10312). Rebus: mē̃ḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.)

bicha, bichā ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) sambr.o bica = gold ore (Mundarica) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)

bhaṭa ‘six ’; rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

satthiya ‘svastika glyph’; rebus: satthiya ‘zinc’, jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri), satva, ‘zinc’ (Pkt.)

kola ‘woman’; rebus: kol ‘iron’. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); kollë ‘blacksmith’ (Koḍ)

muha -- n. ʻmouth, faceʼ (Pkt.) mũh ‘face’; rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Mu.)

kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.) कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pañcaloha’ (Tamil) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith’; kollaṉ ‘blacksmith’ (Tamil).

ṭagara = tabernae montana (Skt.) ṭagara ‘antelope’; rebus: ṭagara ‘tin’. Cf. cognate: tamkāru, damgar ‘merchant’(Sumerian).

ḍã̄gar ‘horned cattle’ (K.) rebus: ḍāṅgar ‘blacksmith’ (H.) damgar ‘merchant, trader’(Sumerian).

Sources for the images:

Image 1. The Samarra bowl (ca. 4000 BC) at on exhibit at the Pergamon museum, Berlin. The bowl was excavated as Samarra by Ernst Herzfeld in the 1911-1914 campaign, and described in a 1930 publication. The design consists of a rim, a circle of eight fish, and four fish swimming towards the center being caught by four birds. At the center is a swastika symbol. (Ernst Herzfeld, Die vorgeschichtlichen Töpfereien von Samarra, Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra 5, Berlin 1930.)

Image 2. Women with flowing hair and scorpions, Samarra, Iraq. After Ernst Herzfeld, Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra V: Die vorgeschichtischenTopfereien, Univ. of Texas Press, pl. 30. Courtesy Dietrich Reimer. This image is discussed in Denise Schmandt-Besserat, When writing met art, p.19. “The design features six humans in he center of the bowl and six scorpions around the inner rim. The six identical anthropomorphic figures, shown frontally, are generally interpreted as females because of their wide hips, large thighs, and long, flowing hair…Six identical scorpions, one following after the other in a single line, circle menacingly around the women.”

Image 3. “The Warka Vase or the Uruk Vase is a carved alabaster stone vessel found in the temple complex of the Sumerian goddess Inanna in the ruins of the ancient city of Uruk, located in the modern Al Muthanna Governorate, in southern Iraq. Like the Narmer Palette from Egypt, it is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture, dated to c. 3,200–3000 BC. The vase was discovered as a collection of fragments by German Assyriologists in their sixth excavation season at Uruk in 1933/1934. It is named after the modern village of Warka - known as Uruk to the ancient Sumerians.”

Some examples of use of comparable hieroglyphs frp, Indus writing corpora may be cited:

Chanhu-daro Seal obverse and reverse. The oval sign of this Jhukar culture seal is comparable to other inscriptions. Fig. 1 and 1a of Plate L. After Mackay, 1943. The hieroglyphs of the seal relate representations of bun ingots to two orthographic representations of ‘antelopes’: one is shown walking, the other is shown with head turned backwards. A flower is shown, perhaps, a representation of tabernae Montana.

Chanhu-daro Seal obverse and reverse. The oval sign of this Jhukar culture seal is comparable to other inscriptions. Fig. 1 and 1a of Plate L. After Mackay, 1943. The hieroglyphs of the seal relate representations of bun ingots to two orthographic representations of ‘antelopes’: one is shown walking, the other is shown with head turned backwards. A flower is shown, perhaps, a representation of tabernae Montana. Stamp seal from Susa , at Louvre Museum. “Susa is one of the oldest known settlements of the world, possibly founded about 4200 BC, although the first traces of an inhabited village have been dated to ca. 7000 BCE. The seal depicts two goat-antelopes head to tail, outside an oval.”

Stamp seal from Susa , at Louvre Museum. “Susa is one of the oldest known settlements of the world, possibly founded about 4200 BC, although the first traces of an inhabited village have been dated to ca. 7000 BCE. The seal depicts two goat-antelopes head to tail, outside an oval.”  Tin bun ingot. Late Bronze Age, 10th-9th century B.C.E. Salcombe shipwreck, 300 yards off the South Devon coast, England, 2009.

Tin bun ingot. Late Bronze Age, 10th-9th century B.C.E. Salcombe shipwreck, 300 yards off the South Devon coast, England, 2009.  Cylinder seal: lion and sphinx over an antelope

Cylinder seal: lion and sphinx over an antelope The depiction of a bull’s head together with an antelope is significant and recalls the association of bull’s head with oxhide ingots. The antelope looking backwards is flanked by a lion (with three dots at the back of the head) and a winged animal (tiger?)

Bhirrana

BhirranaAllograph: Kur. xolā tail. Malt. qoli id. (DEDR 2135). [The ‘short-tail’ is a hieroglyph which is ligatured to an ‘antelope’ – as a hieroglyph read rebus. Such a ligatured-tail evolved into a ‘sign’ of the Indus script which appears on inscribed copper-tablets.] Rebus: kol ‘working in iron (metal), blacksmith (in this case, tin-smith)’. baṭa ‘six’ (hence six short strokes)(G.); rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace, smelter’ (Santali). The stalk in front of the antelope is explained rebus: kolmo ‘rice-plant’(Santali); rebus: kolami ‘smithy/forge’ (Te.) The antelope orthography shows a ‘ram’: tagara ‘ram’; if the plant is tabernae montana, tagaraka ‘tabernae montana’; rebus: tagara ‘tin’. The seal shows an artisan-merchant who has a smelter to produce tin ingots.Antelope: meḷh ‘goat’ (Br.) Rebus: meṛha, meḍhi ‘merchant’s clerk; (G.) meḍho ‘one who helps a merchant’ vi.138 ‘vaṇiksahāyah’ (deśi. Hemachandra). Cf. meluhha-mũh > mleccha-mukha ‘copper (ingot)’.

“The earliest (Indus) inscriptions date back to 3500 BC.” h1522A sherd. Slide 124. Inscribed Ravi sherd. The origins of Indus writing can now be traced to the Ravi Phase (c. 3300-2800 BCE) at Harappa. Some inscriptions were made on the bottom of the pottery before firing. Other inscriptions such as this one were made after firing. This inscription (c. 3300 BCE) appears to be three plant symbols arranged to appear almost anthropomorphic. The trident looking projections on these symbols seem to set the foundation for later symbols…

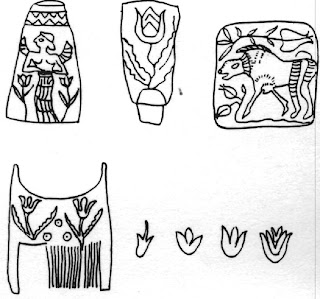

“The earliest (Indus) inscriptions date back to 3500 BC.” h1522A sherd. Slide 124. Inscribed Ravi sherd. The origins of Indus writing can now be traced to the Ravi Phase (c. 3300-2800 BCE) at Harappa. Some inscriptions were made on the bottom of the pottery before firing. Other inscriptions such as this one were made after firing. This inscription (c. 3300 BCE) appears to be three plant symbols arranged to appear almost anthropomorphic. The trident looking projections on these symbols seem to set the foundation for later symbols… The glyph is tabernae montana, ‘mountain tulip’. A soft-stone flask, 6 cm. tall, from Bactria (northern Afghanistan) showing a winged female deity (?) flanked by two flowers similar to those shown on the comb from Tell Abraq. Ivory comb with Mountain Tulip motif and dotted circles. TA 1649 Tell Abraq.

The glyph is tabernae montana, ‘mountain tulip’. A soft-stone flask, 6 cm. tall, from Bactria (northern Afghanistan) showing a winged female deity (?) flanked by two flowers similar to those shown on the comb from Tell Abraq. Ivory comb with Mountain Tulip motif and dotted circles. TA 1649 Tell Abraq.  Susa pot, from Meluhha, with metal artifacts. The pot has an inscription, painted with ‘fish’ hieroglyph.

Susa pot, from Meluhha, with metal artifacts. The pot has an inscription, painted with ‘fish’ hieroglyph. Meluhha and contributions to tin and zinc alloys

[quote] “...the earliest brass in the world was in the Harappan site of Lothal and then in the early PGW site of Atranjikhera. The primacy of zinc metallurgy in India is established by three kinds of evidences: (a) second millennium BCE radiocarbon dating of zinc ore mine in Southern Rajasthan, (b) fourth century BCE brass vase in Taxila assaying 34% zinc, and (c) second century AD literature of Nagarjuna describing distillation of zinc…(paper) details…large scale zinc manufacture in medieval Zawar and the unique phenomenon of a technology transfer from India to the western world…The earliest method of making brass was possibly the cementation process in which finely divided copper fragments were intimately mixed with roasted zinc ore (oxide) and reducing agent, such as charcoal, and heated to 1000 degrees C in a sealed crucible. Zinc vapour formed dissolved into the copper fragments yielding a poor quality brazz, zinc percentage of which could not be easily controlled. Fusion of zinc with copper increases the strength, hardness and toughness of the latter. When the alloy is composed of 10-18% zinc, it has a pleasing golden yellow colour. It can also take very high polish and literally glitter like gold. For this property, brass has been widely used for casting statuary, covering temple roofs, fabricating vessels, etc…Lothal (2200-1500 BCE) showed one highly oxidized antiquity (No. 4189), which assayed 70.7# copper, 6.04# zinc, 0.9% Fe and 6.04% acid-soluble component (probably carbonate, a product of atmospheric corrosion)…Most of the brass samples in ancient India contained variable proportions of Zn, Sn and Pb…During the Harappan era, copper used to be alloyed with tin and arsenic; since these were scarce commodities, alternative alloying elements had to be looked for. Artisans in the Rajasthan-Gujarat region might have stumbled on to zinc ore deposit as a new source of alloying element…(Taxila vase BM 215-284)…dated to the 4th century BCE. This brass sample contains 34.34% zinc, 4.25% Sn, 3.0% Pb, 1.77% and 0.4% nickel. This is very strong evidence for the availability of metallic sinc in the 4th century BCE. Possibly India was the first to make this metal zinc (rasaka) by the distillation process, as practiced for other metal mercury (rasa)...The pseudo-Aristotelian work, ‘On marvelous things heard’ mentioned: “They also say that amongst the Indians the bronze is so bright, clean and free from corrosion that it is indistinguishable from gold, but that amongst the cups of Darius there is a considerable number that could not be distinguished from gold or bronze except by color.”...The Indian emphasis was on the ‘gold-like’ brass and not on the zinc metal…The discovery of three important hoards of metallic art objects at Mahudi of north Gujarat, Lilvadeva (north-east) and Akota of central Gujarat, dated between 6th and 11th centuries AD, proved that the artisans there had developed four varieties of alloys: (a) bronze, (b) zinc-bronze, (c) lead brass, and (d) conventional brass…The technical term ārakūṭa for brass persisted through centuries and we find this mentioned in the 4th century AD Jaina text Angavijja (as hārakūḍa) and also in Amarakośa (450 AD)…Pliny mentioned the Latin term aurichalcum (golden copper), made in India from cadmia, identified as calamine or the zinc ore. Samuel Beal suggested that the name cadmia came from Calamina, a port at the mouth of the Indus, which negotiated the export of the ore or the alloy of zinc. Ball, however, suggested that the port was Calliana or Kalyan near Bombay. The sixth century AD traveler Sopater had mentioned Calliana exporting brass…The earliest reference to zinc as a metl is found in Nagarjuna’s Rasa-Ratnākara. In one passage (RR 3) it was mentioned: “What wonder is that rasaka (zinc or zinc ore) roasted with three parts of śulva (copper) converts the latter into gold”. Actually, this was gold-coloured 25% zinc-brass, also known as pīta-tāla (pitala) or yellow alloy.”…jast (derived from Sanskrit jaśada or zinc)…On brass and zinc metallurgy, the primacy of India in the ancient and medieval world is now beyond any dispute.” [unquote]

[quote] "The first smelting of iron [ore] may have taken place as early as 5000 BC" at Samarra, Mesopotamia, but more commonly early iron was recovered from fallen meteors (yielding iron with a characteristic 4+% nickel content). By the middle of the fourth millennium BC, "both texts and objects reveal the presence of iron" in Mesopotamia, from where the Jaredites departed. Just possibly they brought with them to the New World technical knowledge of that metallurgy. Sporadically throughout the Bronze Age (about 3500 BC–1000 BC) in the Near East, wrought (nonmeteoric) iron objects were being produced, along with continued use of the meteoric type. Yet details of the history at that time are poorly known. The find of an iron artifact from Slovakia dated to the 17th century BC leads one researcher to lament "how little we actually know about the use of iron during the second millennium BCE." Steel is "iron that has been combined with carbon atoms through a controlled treatment of heating and cooling." Yet "the ancients possessed in the natural (meteoric) nickel-iron alloy a type of steel that was not manufactured by mankind before 1890." (It has been estimated that 50,000 tons of meteoritic material falls on the earth each day, although only a fraction of that is recoverable.) By 1400 BC, smiths in Armenia had discovered how to carburize iron by prolonged heating in contact with carbon (derived from the charcoal in their forges). This produced martensite, which forms a thin layer of steel on the exterior of the object (commonly a sword) being manufactured. Iron/steel jewelry, weapons, and tools (including tempered steel) were definitely made as early as 1300 BC (and perhaps earlier), as attested by excavations in present-day Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and Jordan. "Smiths were carburizing [i.e., making steel] intentionally on a fairly large scale by at least 1000 BC in the Eastern Mediterranean area." [unquote]

Conclusions

The continued use of hieroglyphs of Indus writing together with cuneiform texts is a characteristic feature of the evolution of writing in ancient Near East as it progressed from the use of tokens and bullae to the use of glyphs to denote many metallurgical categories. A method of rebus readings evidenced for Narmer palette in Egypt applied to the Indus writing glyphs reveals Meluhha (mleccha) substrate lexemes from Indian sprachbund.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/137862462/Bronze-Age-Writing-in-Ancient-Near-East