Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/ktafaud

https://www.facebook.com/srini.kalyanaraman/posts/10156239009069625?pnref=story

The priests of Mohenjo-daro and Mari (Susa) are similar in appearance, with a trimmed beard and bald hairstyle.

This monograph demonstrates that both representations of priests (guild-masters?) -- both dated to ca. 2500 BCE -- of Mohenjo-daro and Mari foundries are smelters of iron.

Three dotted circles of the trefoil hieroglyph on the shawl of the Mohenjo-daro priest statue: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi'smithy, forge' The function of the priest has been identified as

R̥gveda Potr̥ 'purifier priest', Indus Script dhāvaḍ 'smelter' See: http://tinyurl.com/llvrtwu

![Image result for mari procession susa louvre]() A soldier and a Mari dignitary who carries the standard of Mari. Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

A soldier and a Mari dignitary who carries the standard of Mari. Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum. ![]() Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 (Fig.2) Indus Script Cipher provides a clue to the standard of Mari which is signified by a young bull with one horn.

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 (Fig.2) Indus Script Cipher provides a clue to the standard of Mari which is signified by a young bull with one horn.

![Image result for culm of millet mari procession susa louvre]()

Hypertext on a procession depicted on a schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques -- in Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE. The hypertext is composed of two hieroglyphs/hypertexts: 1. culm of millet and 2. one-horned young bull (which is a common pictorial motif in Harappa (Indus) Script Corpora.

Culm of millet hieroglyph: karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

One-horned young bull hypertext/hyperimage: कोंद kōnda ‘young bull' कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, turner'. Thus, an iron turner (in smithy/forge).

The validation of the culm of millet hieroglyph comes from an archaeo-botanical study (2016).

In the article, 'Exploring crop processing northwest Bharata ca. 3200 to 1500 BCE' -- Jennifer Bates et al, 2016, make a significant observation about the cultivation of millets in Northwest Bharat, especially in the Ganga -Sarasvati River Basins. This observation underscores the importance millet and related crop images in the lives of the people of the Bronze Age of Eurasia.

![Image result for millet india]()

![Image result for millet]()

![]() Pearl millet in the field.

Pearl millet in the field.

Culm of millet should have been an object recognized by the people of the 4th millennium BCE in this region which had contacts with Susa and Mari (Sumerian/Elamite civilizations). "In the production of malted grains the culms refer to the rootlets of the germinated grains. The culms are normally removed in a process known as "deculming" after kilning when producing barley malt, but form an important part of the product when making sorghum or milletmalt."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culm_(botany)

There are three possible identifications of this image: 1. culm of millet; 2. Christ's thorn; 3. Stalk or thorny joint. In my view, the appropriate fit with the semantics of 'one-horned young bull' is its identification as a 'culm of millet'.

The procession is a proclamation and a celebration of new technological competence gained by the 'turner' artisans of the civilization.

The 'turner' (one who uses a lathe for turning) in copper/bronze/brass smithy/forge has gained the competence to work with karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

![]()

Hieroglyph: stalk, thorny

![]() Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black;

Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black;

S. kã̄ḍo ʻ thorny ʼ (CDIAL 3022).kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion withgaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Prob. ← Drav., cf. Tam. kaṇ ʻ joint of bamboo or sugarcane ʼ EWA i 197] Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, °ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, °ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ. [< IE. *kondo -- , Gk. kondu/lo s ʻ knuckle ʼ, ko/ndo s ʻ ankle ʼ T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 55] S.kcch. kāṇḍī f. ʻ lucifer match ʼ?(CDIAL 3023) *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1 ] L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ.(CDIAL 3024). 3026 kāˊṇḍīra ʻ armed with arrows ʼ Pāṇ., m. ʻ archer ʼ lex. [kāˊṇḍa -- ]H. kanīrā m. ʻ a caste (usu. of arrow -- makers) ʼ.(CDIAL 3026).

![]()

![]() Ziziphus (jujube) is called कूदी कूट्/ई in Atharvaveda. It is बदरी, "Christ's thorn". Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Ziziphus (jujube) is called कूदी कूट्/ई in Atharvaveda. It is बदरी, "Christ's thorn". Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Some images related to Susa (Sumer)

Culm is the hollow stem of a grass or cereal plant, especially that bearing the flower. Sumer procession shows the banner of aone-horned bull held aloft on a culm of millet. This is unmistakable hieroglyph narrative since a banner topped by a sculpted image (young bull with one-horn) cannot be held aloft on a millet culm.

Both the sculpted image of young bull with one horn AND the millet culm are hieroglyphs.

![]() The post holding the young bull banner is signified by a culm of plant, esp. of millet. This is karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba'iron' ajirda karba 'very hard iron' (Tulu)

The post holding the young bull banner is signified by a culm of plant, esp. of millet. This is karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba'iron' ajirda karba 'very hard iron' (Tulu)

L’enseigne (M,458) (pl. LVII) est faite d’un petit taureau dresse, passant a gauche, monte sur un socle supporte par l’anneau double du type passe-guides. La hamper est ornementee d’une ligne chevronnee et on retrouve le meme theme en travers de l’anneau double.

![]() In front of a soldier, a Sumerian standard bearer holds a banner aloft signifying the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Harappa Script (Indus writing). Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

In front of a soldier, a Sumerian standard bearer holds a banner aloft signifying the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Harappa Script (Indus writing). Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

![Image result for mari mesopotamia]()

![]()

![]() This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet).koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a

This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet).koDiya ‘rings on neck’, ‘young bull’ koD ‘horn’ rebus 1: koṭiya 'dhow, seafaring vessel' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull].खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ]A variety of

kod. = place where artisans work (G.lex.) kod. = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.lex.) gor.a = a cow-shed; a cattleshed; gor.a orak = byre (Santali.lex.) कोंड (p. 180) [ kōṇḍa ] A circular hedge or field-fence. 2 A circle described around a person under adjuration. 3 The circle at marbles. 4 A circular hamlet; a division of a

The Louvre has three fragments from Sargon’s Victory Steles. The steles were discovered in the 1920’s. They were found in Susa (Iran) where they had been carried away as booty in the 12th century B.C., about a thousand years after they were constructed. The fragments are labeled Sb 1, Sb 2, and Sb 3. Fragments Sb 2 and Sb 3 are obviously from the same stele because they are carved from the same stone and the prisoners' hairstyle matches on both fragments (the hair is curly on top but short on the sides). As parts of the same monument, fragments Sb 2 and Sb 3 are displayed together in the museum.

![]()

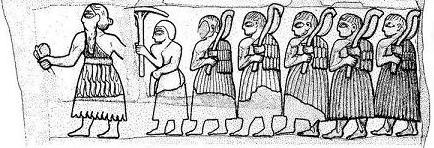

The victory procession of Sargon. (Louvre, Sb 1).

Fragment Sb 1 is different. It has the rectangular form of an obelisk rather than the rounded shape of the other fragments. The color of the stone is different and the height of the register (row) doesn't match the height of the register on Sb 3. The fragment clearly belongs to a victory stele because of the triumphal procession and the scenes of prisoners taken in battle, and it clearly belongs to Sargon because it has his name written on it, but it doesn’t belong with the other two fragments. It is part of a completely different victory stele.

The figures wrap around two sides of the stele and continue onto a third side. The fourth side is missing due to damage. The details of the stele are best seen in these drawings by Lorenzo Nigro:

![]()

Sargon leads the victory procession.

http://sumerianshakespeare.com/56801/237601.html

![]()

![]()

Source: http://sumer2sargon.blogspot.in/p/history.html![]()

![]()

Exploring Indus crop processing: combining phytolith and macrobotanical analyses to consider the organisation of agriculture in northwest India c. 3200–1500 BCE

Jennifer Bates1 • Ravindra Nath Singh2 • Cameron A. Petrie1

https://www.academia.edu/29214906/Exploring_Indus_crop_processing_combining_phytolith_and_macrobotanical_analyses_to_consider_the_organisation_of_agriculture_in_northwest_India_c._3200_1500_BC

Table 4 Summary of main findings

Main conclusions

Macrobotanical – Wheat/barley showed fewer processing stages, with the main focus on mid-processing stage of fine sieving

– Millet and rice showed all processing stages were present on site with the main focus on early processing of winnowing

Phytoliths – Wheat/barley showed all stages including early processing were present

– Millet processing showed more late stage than early stage

– Little rice chaff: taphonomy? But weeds showed similar pattern to millet—late stage processing was present

Combined datasets

– Wheat/barley showed less final stage cleaning on site, but both early and mid-stage processing were present

– Millet and rice showed all stages present and carried out regularly on sites

– Macrobotanical grain analysis (Bates 2016; Bates et al. in press; Petrie et al. in press c) suggested that millets were more regularly used and in greater proportions on these sites than wheat/barley and to a lesser extent rice

The macrobotanical analysis suggests that the rabi (winter) cereals of wheat and barley consistently had fewer processing stages than kharif (summer) crops of rice and millet. The wheat and barley data suggest that fine sieving was the main stage carried out on all sites, with some hand sorting. Rare evidence for chaff in the form of rachis internodes potentially suggests that some earlier stages of processing were also being carried out. In contrast, the presence of light weed seeds in the kharif (summer) assemblage provided evidence for winnowing of summer cereals, which is a stage that can usually be carried out in bulk close to harvest. As such, it could be argued that the macrobotanical remains indicate that the kharif crops were stored at all sites closer to the harvest than the rabi (winter) crops, and that this might imply differences in labour organisation at harvest dependant on the season of cropping (Stevens 1996, 2003; Fuller et al. 2014). The different processing approaches used for the various cereals indicated by the macrobotanical remains suggest that the seasonality of cropping drove the labour division and decisions relating to labour organisation at these settlements, rather than the time period or the geographical location of the settlements. It is notable that the macrobotanical remains imply that rabi (winter) cereal processing was more centralised than kharif (summer) processing. Alternative explanations are also possible, and processing waste from these bulk stages may have been incorporated in fuel differing either in what parts of the plant were being fed to animals and thus incorporated into dung fuel at differing times of the year, perhaps through differing grazing and foddering practices dependant on season, or through what was being incorporated into dung or used as additional fuel to increase fuel potential at different seasons.

...

![]() Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]

Pk. vaggā -- f. ʻ bridle ʼ; K. wag f. ʻ rein, tether ʼ; S. vāg̠a f. ʻ rein, halter ʼ (whence vāg̠aṇu ʻ to tie up a horse ʼ); L. (Ju.) vāg̠ f. ʻ rein ʼ, awāṇ. vāg; P. vāg, bāg f. ʻ bridle ʼ, N.bāg -- ḍori; B. bāg ʻ rein ʼ; Or. bāga ʻ bridle, rein ʼ, gaja -- bāga ʻ elephant goad ʼ; Bi. bāg -- ḍor ʻ tether for horses ʼ; Mth. Bhoj. bāg ʻ rein, bridle ʼ, OAw. bāga f., H. bāg f. (→ K. bāg -- ḍora m., M. bāg -- dor); G. vāg f. ʻ rein, guiding rope of a bullock ʼ; M. vāg -- dor m. ʻ bridle ʼ.Addenda: valgā -- and *vālgā -- [Dial. a ~ ā < IE. o (Lett. valgs ʻ rope, cord ʼ) T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 72] (CDIAL 11420) valgulikā f. ʻ box, chest ʼ Kathās. 2. vāggulika -- m. ʻ betel -- bearer ʼ lex.1. Or. bāguḷi ʻ metal case for betel packets ʼ.2. Or. bāguḷī ʻ betel -- bearer to a king ʼ.(CDIAL 11422) bahulā f. pl. ʻ the Pleiades ʼ VarBr̥S., °likā -- f. pl. lex. [bahulá -- ] Kal. bahul ʻ the Pleiades ʼ, Kho. ból, (Lor.) bou l, bolh , Sh. (Lor.) b*l le . (CDIAL 9195) Rebus: A baghlah, bagala or baggala (Arabic: بغلة ) is a large deep-sea dhow, bagalo = an Arabian merchant vessel (G.) bagala = an Arab boat of a particular description (Ka.); bagalā (M.); bagarige, bagarage = a kind of vessel (Ka.)

https://www.facebook.com/srini.kalyanaraman/posts/10156239009069625?pnref=story

The priests of Mohenjo-daro and Mari (Susa) are similar in appearance, with a trimmed beard and bald hairstyle.

This monograph demonstrates that both representations of priests (guild-masters?) -- both dated to ca. 2500 BCE -- of Mohenjo-daro and Mari foundries are smelters of iron.

Three dotted circles of the trefoil hieroglyph on the shawl of the Mohenjo-daro priest statue: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi'smithy, forge' The function of the priest has been identified as

R̥gveda Potr̥ 'purifier priest', Indus Script dhāvaḍ 'smelter' See: http://tinyurl.com/llvrtwu

This identification is consistent with the trefoil expression which signifies a kole.l 'smith, forge' which is also kole.l'temple.

On a Mari mosaic panel, a similar-looking priest leads a procession with a unique flag. The flagpost is a culm of millet and at the top of the post is a rein-ring proclaiming a one-horned young bull. All these are Indus Script hieroglyphs.

The 'rein rings' are read rebus: valgā, bāg-ḍora 'bridle' rebus (metath.) bagalā 'seafaring dhow'. See Annex: Rein-rings.

A soldier and a Mari dignitary who carries the standard of Mari. Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

A soldier and a Mari dignitary who carries the standard of Mari. Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.  Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 (Fig.2) Indus Script Cipher provides a clue to the standard of Mari which is signified by a young bull with one horn.

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 (Fig.2) Indus Script Cipher provides a clue to the standard of Mari which is signified by a young bull with one horn.Hypertext on a procession depicted on a schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques -- in Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE. The hypertext is composed of two hieroglyphs/hypertexts: 1. culm of millet and 2. one-horned young bull (which is a common pictorial motif in Harappa (Indus) Script Corpora.

Culm of millet hieroglyph: karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

One-horned young bull hypertext/hyperimage: कोंद kōnda ‘young bull' कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, turner'. Thus, an iron turner (in smithy/forge).

The validation of the culm of millet hieroglyph comes from an archaeo-botanical study (2016).

In the article, 'Exploring crop processing northwest Bharata ca. 3200 to 1500 BCE' -- Jennifer Bates et al, 2016, make a significant observation about the cultivation of millets in Northwest Bharat, especially in the Ganga -Sarasvati River Basins. This observation underscores the importance millet and related crop images in the lives of the people of the Bronze Age of Eurasia.

Pearl millet in the field.

Pearl millet in the field.Culm of millet should have been an object recognized by the people of the 4th millennium BCE in this region which had contacts with Susa and Mari (Sumerian/Elamite civilizations). "In the production of malted grains the culms refer to the rootlets of the germinated grains. The culms are normally removed in a process known as "deculming" after kilning when producing barley malt, but form an important part of the product when making sorghum or milletmalt."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culm_(botany)

There are three possible identifications of this image: 1. culm of millet; 2. Christ's thorn; 3. Stalk or thorny joint. In my view, the appropriate fit with the semantics of 'one-horned young bull' is its identification as a 'culm of millet'.

The procession is a proclamation and a celebration of new technological competence gained by the 'turner' artisans of the civilization.

The 'turner' (one who uses a lathe for turning) in copper/bronze/brass smithy/forge has gained the competence to work with karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

Hieroglyph on an Elamite cylinder seal (See illustration embedded)

Hieroglyph: stalk, thorny

Seal published: The Elamite Cylinder seal corpus: c. 3500-1000 BCE.karba 'millet culm' rebus: karba 'iron'. krammara 'look back' rebus: kamar'artisan' karaDa 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' mlekh 'goat' (Br.);mr̤eka (Te.); mēṭam 'ram, antelope' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' (Pali)mlecchamukha 'copper' (Samskrtam)

Tubular stalk: karb (Punjabi) kaḍambá, kalamba -- 1 , m. ʻ end, point, stalk of a pot- herb ʼ lex. [See kadambá -- ] B. kaṛamba ʻ stalk of greens ʼ; Or. kaṛambā, °mā stalks and plants among stubble of a reaped field ʼ; H. kaṛbī, karbī f. ʻ tubular stalk or culm of a plant, esp. of millet ʼ (→ P. karb m.); M. kaḍbā m. ʻ the culm of millet ʼ. -- Or. kaḷama ʻ a kind of firm -- stemmed reed from which pens are made ʼ infl. by H. kalam ʻ pen ʼ ← Ar.?(CDIAL 2653) See: Ta. kāmpu flower-stalk, flowering branch, handle, shaft, haft. Ma. kāmpu stem, stalk, stick of umbrella. Ko. ka·v handle. To. ko·f hollow stem, handle of tool. Ka. kāmu, kāvu stalk, culm, stem, handle. Te. kāma stem, stalk, stick, handle (of axe, hoe, umbrella, etc.), shaft. Ga. (S.3) kāŋ butt of axe. Go. (Tr.) kāmē stalk of a spoon; (Mu.) kāme handle of ladle (Voc. 640)(DEDR1454). Ka. kAvu is cognate with karb 'culm of millet' and kharva 'nidhi'.

Hieroglyph 1: H. kaṛbī, karbī f. ʻ tubular stalk or culm of a plant, esp. of millet ʼ (→ P. karb m.); M. kaḍbā m. ʻ the culm of millet ʼ. (CDIAL 2653) Mar. karvā a bit of sugarcane.(DEDR 1288) Culm, in botanical context, originally referred to a stem of any type of plant. It is derived from the Latin word for 'stalk' (culmus) and now specifically refers to the above-ground or aerial stems of grasses and sedges. Proso millet, common millet, broomtail millet, hog millet, white millet, broomcorn millet Panicum miliaceum L. [Poaceae]Leptoloma miliacea (L.) Smyth; Milium esculentum Moench; Milium paniceum Mill.; Panicum asperrimum Fischer ex Jacq.;Panicum densepilosum Steud.; Panicum miliaceum Blanco, nom. illeg., non Panicum miliaceum L.; Panicum miliaceumWalter, nom. illeg., non Panicum miliaceum L.; Panicum miliaceum var. miliaceum; Panicum milium Pers. (Quattrocchi, 2006) Proso millet is an erect annual grass up to 1.2-1.5 m tall, usually free-tillering and tufted, with a rather shallow root system. Its stems are cylindrical, simple or sparingly branched, with simple alternate and hairy leaves. The inflorescence is a slender panicle with solitary spikelets. The fruit is a small caryopsis (grain), broadly ovoid, up to 3×2 mm, smooth, variously coloured but often white, shedding easily (Kaume, 2006).Panicum miliaceum has been cultivated in eastern and central Asia for more than 5000 years. It later spread into Europe and has been found in agricultural settlements dating back about 3000 years. http://www.feedipedia.org/node/722 Ta. varaku common millet, Paspalum scrobiculatum; poor man's millet, P. crusgalli. Ma. varaku P. frumentaceum; a grass Panicum. Ka. baraga, baragu P. frumentaceum; Indian millet; a kind of hill grass of which writing pens are made. Te. varaga, (Inscr.) varuvu Panicum miliaceum. / Cf. Mar. barag millet, P. miliaceum; Skt. varuka- a kind of inferior grain. [Paspalum scrobiculatum Linn. = P. frumentaceum Rottb. P. crusgalli is not identified in Hooker.] (DEDR 5260)

Rebus 1:

Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black;

Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron; Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal (DEDR 192) Tu. kari soot, charcoal; kariya black; Rebus 2: karvata [ karvata ] n. market-place. (Skt.lex.) கர்

Rebus 3: खर्व (-र्ब) a. [खर्व्-अच्] 1

Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

S. kã̄ḍo ʻ thorny ʼ (CDIAL 3022).kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion with

Ziziphus (jujube) is called कूदी कूट्/ई in Atharvaveda. It is बदरी, "Christ's thorn". Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Ziziphus (jujube) is called कूदी कूट्/ई in Atharvaveda. It is बदरी, "Christ's thorn". Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'Some images related to Susa (Sumer)

Culm is the hollow stem of a grass or cereal plant, especially that bearing the flower. Sumer procession shows the banner of aone-horned bull held aloft on a culm of millet. This is unmistakable hieroglyph narrative since a banner topped by a sculpted image (young bull with one-horn) cannot be held aloft on a millet culm.

Both the sculpted image of young bull with one horn AND the millet culm are hieroglyphs.

M.458 H. 0.070 m. (totale); h. 0, 026 m. (taureau sur socle); l. 0,018m.

Translation

The sign (M, 458) (pl. LVII) is made of a young bull stand, from left, mounted on a base supports the double ring-pass type guides. The hamper is decorated with a line and the same theme is found across the double ring.

M.458 H. 0.070 m. (Total); h. 0, 026 m. (Bull on base); l. 0,018m.

Source: http://digital.library.stonybrook.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/amar/id/48366/rec/2 (Parrot, Andre, Mission archéologique de Mari. V. I: Le temple d'Ishtar, p.161)

- Frise d'un panneau de mosaïqueVers 2500 - 2400 avant J.-C.Mari, temple d'Ishtar

- Coquille, schiste

- Fouilles Parrot, 1934 - 1936AO 19820 Louvre reference

In front of a soldier, a Sumerian standard bearer holds a banner aloft signifying the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Harappa Script (Indus writing). Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

In front of a soldier, a Sumerian standard bearer holds a banner aloft signifying the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Harappa Script (Indus writing). Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques. Louvre Museum.

Location of Mari.

This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet).

This shell plaque was found in the palace of Mari. It is dated circa 2500 B.C.E. Sumerian soldier carrying weapons, implements (armour, battle-axe, helmet). khOnda ‘young bull’ rebus 2: kOnda ‘lapidary, engraver’ rebus 3: kundAr ‘turner’ कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. खोट [khōṭa] Alloyed--a metal bullcalf. Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f. Sculpture, carving, engraving.

kōḍiya, kōḍe = young bull; kōḍelu = plump young bull; kōḍe = a. male as in:kōḍe du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

ko_t.u = horns (Ta.) ko_r (obl. ko_t-, pl. ko_hk) horn of cattle or wild animals (Go.); ko_r (pl. ko_hk), ko_r.u (pl. ko_hku) horn (Go.); kogoo a horn (Go.); ko_ju (pl. ko_ska) horn, antler (Kui)(DEDR 2200). Homonyms: kohk (Go.), gopka_ = branches (Kui), kob = branch (Ko.) gorka, gohka spear (Go.) gorka (Go)(DEDR 2126).

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull].खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ]A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडरूं (p. 216) [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl.खोंडा (p. 216) [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. 2 fig. A hollow amidst hills; a deep or a dark and retiring spot; a dell. 3 (also खोंडी & खोंडें ) A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

kod. = place where artisans work (G.lex.) kod. = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.lex.) gor.a = a cow-shed; a cattleshed; gor.a orak = byre (Santali.lex.) कोंड (p. 180) [ kōṇḍa ] A circular hedge or field-fence. 2 A circle described around a person under adjuration. 3 The circle at marbles. 4 A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste.कोंडडाव (p. 180) [ kōṇḍaḍāva ] m Ring taw; that form of marble-playing in which lines are drawn and divisions made:--as disting. from अगळडाव The play with holes.कोंडवाड (p. 180) [ kōṇḍavāḍa ] n f C (कोंडणें & वाडा ) A pen or fold for cattle.कोंडाळें (p. 180) [ kōṇḍāḷēṃ ] n (कुंडली S) A ring or circularly inclosed space. 2 fig. A circle made by persons sitting round.

The Louvre has three fragments from Sargon’s Victory Steles. The steles were discovered in the 1920’s. They were found in Susa (Iran) where they had been carried away as booty in the 12th century B.C., about a thousand years after they were constructed. The fragments are labeled Sb 1, Sb 2, and Sb 3. Fragments Sb 2 and Sb 3 are obviously from the same stele because they are carved from the same stone and the prisoners' hairstyle matches on both fragments (the hair is curly on top but short on the sides). As parts of the same monument, fragments Sb 2 and Sb 3 are displayed together in the museum.

The victory procession of Sargon. (Louvre, Sb 1).

Fragment Sb 1 is different. It has the rectangular form of an obelisk rather than the rounded shape of the other fragments. The color of the stone is different and the height of the register (row) doesn't match the height of the register on Sb 3. The fragment clearly belongs to a victory stele because of the triumphal procession and the scenes of prisoners taken in battle, and it clearly belongs to Sargon because it has his name written on it, but it doesn’t belong with the other two fragments. It is part of a completely different victory stele.

The figures wrap around two sides of the stele and continue onto a third side. The fourth side is missing due to damage. The details of the stele are best seen in these drawings by Lorenzo Nigro:

Sargon leads the victory procession.

http://sumerianshakespeare.com/56801/237601.html

Source: http://sumer2sargon.blogspot.in/p/history.html

Exploring Indus crop processing: combining phytolith and macrobotanical analyses to consider the organisation of agriculture in northwest India c. 3200–1500 BCE

Jennifer Bates1 • Ravindra Nath Singh2 • Cameron A. Petrie1

https://www.academia.edu/29214906/Exploring_Indus_crop_processing_combining_phytolith_and_macrobotanical_analyses_to_consider_the_organisation_of_agriculture_in_northwest_India_c._3200_1500_BC

[quote] Abstract This paper presents a preliminary study combining macrobotanical and phytolith analyses to explore crop processing at archaeological sites in Haryana and Rajasthan, northwest India. Current understanding of the agricultural strategies in use by populations associated with South Asia’s Indus Civilisation (3200–1900 BC) has been derived from a small number of systematic macrobotanical studies focusing on a small number of sites, with little use of multi-proxy analysis. In this study both phytolith and macrobotanical analyses are used to explore the organisation of crop processing at five small Indus settlements with a view to understanding the impact of urban development and decline on village agriculture. The differing preservation potential of the two proxies has allowed for greater insights into the different stages of processing represented at these sites: with macrobotanical remains allowing for more species-level specific analysis, though due to poor chaff presentation the early stages of processing were missed; however these early stages of processing were evident in the less highly resolved but better preserved phytolith remains. The combined analyses suggests that crop processing aims and organisation differed according to the season of cereal growth, contrary to current models of Indus Civilisation labour organisation that suggest change over time. The study shows that the agricultural strategies of these frequently overlooked smaller sites question the simplistic models that have traditionally been assumed for the time period, and that both multi-proxy analysis and rural settlements are deserving of further

exploration.

...

Table 4 Summary of main findings

Main conclusions

Macrobotanical – Wheat/barley showed fewer processing stages, with the main focus on mid-processing stage of fine sieving

– Millet and rice showed all processing stages were present on site with the main focus on early processing of winnowing

Phytoliths – Wheat/barley showed all stages including early processing were present

– Millet processing showed more late stage than early stage

– Little rice chaff: taphonomy? But weeds showed similar pattern to millet—late stage processing was present

Combined datasets

– Wheat/barley showed less final stage cleaning on site, but both early and mid-stage processing were present

– Millet and rice showed all stages present and carried out regularly on sites

– Macrobotanical grain analysis (Bates 2016; Bates et al. in press; Petrie et al. in press c) suggested that millets were more regularly used and in greater proportions on these sites than wheat/barley and to a lesser extent rice

The macrobotanical analysis suggests that the rabi (winter) cereals of wheat and barley consistently had fewer processing stages than kharif (summer) crops of rice and millet. The wheat and barley data suggest that fine sieving was the main stage carried out on all sites, with some hand sorting. Rare evidence for chaff in the form of rachis internodes potentially suggests that some earlier stages of processing were also being carried out. In contrast, the presence of light weed seeds in the kharif (summer) assemblage provided evidence for winnowing of summer cereals, which is a stage that can usually be carried out in bulk close to harvest. As such, it could be argued that the macrobotanical remains indicate that the kharif crops were stored at all sites closer to the harvest than the rabi (winter) crops, and that this might imply differences in labour organisation at harvest dependant on the season of cropping (Stevens 1996, 2003; Fuller et al. 2014). The different processing approaches used for the various cereals indicated by the macrobotanical remains suggest that the seasonality of cropping drove the labour division and decisions relating to labour organisation at these settlements, rather than the time period or the geographical location of the settlements. It is notable that the macrobotanical remains imply that rabi (winter) cereal processing was more centralised than kharif (summer) processing. Alternative explanations are also possible, and processing waste from these bulk stages may have been incorporated in fuel differing either in what parts of the plant were being fed to animals and thus incorporated into dung fuel at differing times of the year, perhaps through differing grazing and foddering practices dependant on season, or through what was being incorporated into dung or used as additional fuel to increase fuel potential at different seasons.

...

The role of millets and also rice, as well as wheat and barley as regular parts of both the annual cropping cycle and the daily lives of people at these settlements implies that the inhabitants were well adapted to a variable environment (Petrie et al. in press a, b, c). Evidence for preurban adaptation to local climatic and environmental variability also suggests that a hypothetical switch towards millets as a possible precursor to urban decline (Madella and Fuller 2006) is not applicable in this region. he stability in the processing strategies for all cereals at these settlements is indicated by the fact that there was little variation over time, and implies that as cities rose and fell around these villages, the rural agricultural strategies continued as before, with household-scale processing being the norm.[unquote]

Annex Rein-rings

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]Pk. vaggā -- f. ʻ bridle ʼ; K. wag f. ʻ rein, tether ʼ; S. vāg̠a f. ʻ rein, halter ʼ (whence vāg̠aṇu ʻ to tie up a horse ʼ); L. (Ju.) vāg̠ f. ʻ rein ʼ, awāṇ. vāg; P. vāg, bāg f. ʻ bridle ʼ, N.bāg -- ḍori; B. bāg ʻ rein ʼ; Or. bāga ʻ bridle, rein ʼ, gaja -- bāga ʻ elephant goad ʼ; Bi. bāg -- ḍor ʻ tether for horses ʼ; Mth. Bhoj. bāg ʻ rein, bridle ʼ, OAw. bāga f., H. bāg f. (→ K. bāg -- ḍora m., M. bāg -- dor); G. vāg f. ʻ rein, guiding rope of a bullock ʼ; M. vāg -- dor m. ʻ bridle ʼ.Addenda: valgā -- and *vālgā -- [Dial. a ~ ā < IE. o (Lett. valgs ʻ rope, cord ʼ) T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 72] (CDIAL 11420) valgulikā f. ʻ box, chest ʼ Kathās. 2. vāggulika -- m. ʻ betel -- bearer ʼ lex.1. Or. bāguḷi ʻ metal case for betel packets ʼ.2. Or. bāguḷī ʻ betel -- bearer to a king ʼ.(CDIAL 11422) bahulā f. pl. ʻ the Pleiades ʼ VarBr̥S., °likā -- f. pl. lex. [

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

Sarasvati Research Center

May 19, 2017