An India-Europe free trade agreement must benefit both

Madhav Nalapat

The Prime Minister needs to reverse course and defend Indian interests abroad rather than foreign interests in India.

omeone forgot to tell Manmohan Singh that the European Union is in crisis, with its banking system effectively bankrupt, and being prevented from visible collapse only by constantly feeding creditors the notion that the EU's financial worries are solvable when they are not. German banks in particular have been the victims of the country's propensity to believe that the EU offered a safety net sufficient to throw to the winds all canons of prudent lending. Their exposure to Greek and Italian debt, in particular, threatens the existence of many of them well before the next 18 months.

In such a context, to spend precious rupees on an expensive junket to Berlin would be laughable, if it were not yet another indication of the fact that time appears to have stood still for the Prime Minister and his economic team, who persist in the belief that the US and the EU are the solution to India's lack of capital, when in fact the answers are these days to be found in West and East Asia. A visit to Kuwait or Tokyo would have been much more profitable for India than the current rush to Germany. Certainly Manmohan Singh has the right to be sentimental about a continent in which he has spent so many happy years as a student, but sentiment has seldom been a sufficient foundation for sound policy.

Since his stint as Union Finance Minister during the Narasimha Rao period, Manmohan Singh has concentrated his considerable intellect on ways of making it easier for foreign businesses — predominantly those based in the member-states of NATO — to do business in India. Or, in other words, to compete with their Indian counterparts. The high bank interest rates favoured by his economic adviser, C. Rangarajan, who as RBI governor in 1994 slowed down a nascent economic boom by a similar policy has been combined with a slew of new regulations passed by the myriad arms of a government harking back to 1970s style control of private industry.

Overall, the effect has been to drain Indian industry of much of its global competitiveness during the nine years that he has been in office, with obvious consequences for the balance of payments. Given the government's penchant for unilateral (and unreciprocated) trade concessions to the EU, it is no surprise that Indian industry is looking nervously at the Prime Minister's foray into a country that has made overpriced manufactures almost an art form.

India being considerably poorer than Europe, it is only fair that the bulk of concessions ought to flow towards this country rather than away from it, as is so often the case. In particular, there needs to be tangible progress on efforts to ensure better access to Indian skill pools, IT and pharma into the European market, rather than simply industries such as textiles, which are rapidly giving way to more modern lines of manufacture. Thus far, the European side has remained committed to ensuring that its people pay extortionate prices for medicines, by blocking access to much cheaper substitutes from India. In the case of manpower flows, services and IT as well, the proffered concessions by EU negotiators have been derisory.

In exchange, what they are asking for is the destruction of the automobile industry in India through a flood of imports from Europe, mainly Germany, as well as unrestricted access to other manufactures and services, all without any corresponding benefit to India. Certainly Manmohan Singh's gesture of gifting the EU more than $10 billion via (an EU-controlled) IMF indicates the PM's generosity towards that particular entity. However, he needs to be reminded that those who voted him to office are in India, not in the EU, and that it is their interests that he has sworn to protect.

Should Manmohan Singh succeed in ensuring better access to Indian medicines — and the chances for this appear minuscle, given both the PM's propensities and the hold that Big Pharma has over EU policymaking — he can have the satisfaction of knowing that the biggest beneficiaries will be the Europeans themselves. At present, they are being forced to pay very high prices for drugs in a context where equally effective (and far cheaper) substitutes are available.

Shamefully, the EU has not merely blocked the flow of drugs from India into its own territories, but has sought through vexatious litigation and police action to stop them from going to countries in Africa, where the price of medicine is often a matter of life or death. Hopefully, someone in the PM's large delegation will whisper a complaint about this to the Germans, who have been the most aggressive in creating a Fortress Europe that demands concessions from much poorer countries such as India than it is willing to concede in return. An India-EU Free Trade Agreement (FTA) ought to be signed only if it is truly beneficial to both sides and not the one-sided agreements that policymakers in India so often return with. Rather than going about the futile task of begging the EU for capital that it does not any more have, the Prime Minister needs to reverse course and defend Indian interests abroad rather than foreign interests in India.

http://www.sunday-guardian.com/analysis/an-india-europe-free-trade-agreement-must-benefit-both#.UWoZPCyQXMk.gmail

India-EU FTA: A parting kick from UPA?

April 12, 2013 16:00 IST

Barring a few exceptions India [ Images ] has a chronic trade deficit with most of its existing FTA partners as it is with most of its proposed FTA partners, says M R Venkatesh.

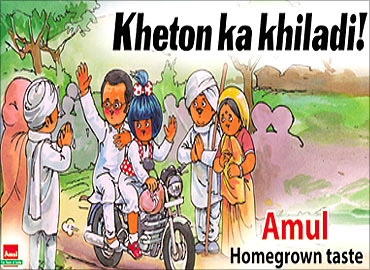

Barring a few exceptions India [ Images ] has a chronic trade deficit with most of its existing FTA partners as it is with most of its proposed FTA partners, says M R Venkatesh.In a way it is stunning, why even unprecedented. In a News Release dated 26th March 2013, the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation Limited – popularly known by its brand name Amul - requested Commerce Minister to be “careful while negotiating in the interest of farmers of India” and “strongly opposed to provide any kind of advantage in import duty on dairy products.”

Why should one of India’s most competitive, efficient and professional organization be mistrustful of the government, warn it to be careful and oppose its moves?

The answer to this question dates back to 2007 when India and EU launched negotiations for a bilateral trade agreement. Since then several rounds of negotiations have taken place covering various aspects of trade and commerce.

These negotiations are expected to be concluded soon – possibly as early as next week. Though the negotiating texts are secret, broad contours of information available raise significant concerns. That explains our paranoia in the first place.

Let us not forget that for past year or two, experts have been pointing to the debilitating impact of India’s trade deficits. This has been on a rising trend since 2003-04 and stands at a phenomenal $190 billion in 2011-12. This is approximately 11 % of the GDP and implies a growth rate of 56 percent over the previous year.

The trade deficit for 2012-13 is no better. The 2012-13 Economic Survey indicates a trade deficit of $167 billion for 2012-13 (April-January) indicating an increase of 8 percent as compared to the corresponding ten month period of 2011-12.

According to projections for 2013-14 made by the Commerce Ministry in its Report on “Strategy For Doubling Exports in Next Three Years: 2011-12 to 2013-14”, India will see a trade deficit of $282 billion under a “business-as-usual” scenario which is expected to be 11.5% of our GDP.

India’s current account deficit, which nets income from services against such trade deficit, is also rising continuously. Compared to $2.66 billion in 2000-01, it now stands at $78 billion in 2011-12. The current account deficit for 2012-13 is estimated to be in excess of 5 percent of the GDP.

This emerging scenario has belied the assumption held in higher echelons of the Indian government that we are an emerging super power in services. In my humble opinion we are not. While that may by itself be a matter of intense debate, the fact remains that service exports are unable to keep pace with our trade deficits.

This makes the government desperate. Consequently, it is constrained to allow volatile and capital flows of doubtful origin to fund current account deficit. Beggars cannot be choosers. Can they? This has added to the financial fragility of the nation and is reflected in rupee exchange rate volatility.

The only way out of the conundrum is to increase exports and simultaneously bring down our imports as a share of our GDP. Elementary economics suggest that to do either we need to improve our competitiveness. Sadly the government is missing this fundamental point. And that is the crux of the issue.

India’s Flawed FTA Policy

India’s FTA policy seems to be oblivious of this fundamental fact. Barring a few exceptions India has a chronic trade deficit with most of its existing FTA partners as it is with most of its proposed FTA partners.

With the EU, the story is no different. India has a consistent trade deficit over several years with EU. If UPA government foolishly proceeds and consummates the India-EU FTA, the trade deficit will go up significantly in agricultural, commodity and industrial segments with possibly some gains in some usual suspects like textiles, jewelry and leather.

Once the FTA becomes operational, experts opine that the EU could flood the Indian market with dairy products, poultry, farm and fisheries, some of which are of strategic importance for India. This will directly compromise India’s agricultural sovereignty and its food security.

It may be pertinent to note that as the WTO negotiations hit a road block we seemed to undertake the FTA route to our trade nirvana. However, experience of the past decade suggests that the plethora of FTAs are not reversing this deficit but in effect aggravating the situation. Needless to emphasize our FTA policy should be revisited.

But does FTA with developed countries make any economic sense? Let us examine.

The developed countries already have low tariffs in most products. To that extent FTA for India makes little or no sense. And if India can sign one, so can other countries and thereby negate the advantage.

Now let us examine the matter in greater detail. The average applied tariffs in EU range between 1.4 to 13.9 percent in agricultural products and 0.5 to 4 percent in industrial products.

In comparison, India’s average applied tariffs, even after significant reductions, are 31.4 and 9.8 percent in agricultural and non agricultural products respectively.

In short, the possibility of a gain just from tariff reduction is huge for the partner but very limited for India. Yet the UPA seems to be insisting on an FTA with EU.

Unchartered Areas

But there is another dimension to this argument. These FTAs are increasingly getting into areas of intellectual property rights commitments, government procurement, and competition policy. Interestingly, these contentious issues have stalled Doha Round of negotiations for years within the WTO.

In short, wherever WTO fails, the route seems to be FTAs. What is forgotten in the melee is that such agreements threaten policy instruments of various developing countries. This in turn erodes our sovereignty.

In contrast to this possibility, the EU is well protected from such external interventions. Let us not forget that even though the EU has low tariffs, it provides very high domestic subsidies to its agricultural producers which work both as a protective barrier in its domestic market, as well as a competitiveness enhancing instrument for its exporters.

Our negotiators fail to understand that these subsidies are trade distorting, affect international prices and thus reduce competitiveness of our producers. Indian exports also face high non-tariff barriers (NTBs) like sanitary and phyto-sanitary [read hygiene] standards as well as technical barriers in EU, making exports to EU extremely difficult.

Given the tariff and NTB structures between the two partners, the EU obviously has much more to gain in terms of tariff reduction while India’s gains lie in sorting out the NTBs and in the removal of EU subsidies – a fact lost on our negotiators.

However, EU negotiators have repeatedly argued that the issues of NTBs [being multilateral] are not to be discussed under any bilateral agreement. Consequently, they opine that these can be negotiated only at the WTO level. Interestingly, India opposes such policies at a multilateral level!

In case of manufactured products the story is no different. We will continue to be handicapped by market access into the EU – not through the tariff barriers but because of NTBs which we are incapable of even comprehending much less negotiating at a bilateral level with EU. Of course, there could be some gains, but these will be marginal. Crucially, the loss outweighs the gains.

Since infrastructure in India including that of marketing, storage and transportation are weak, entrepreneurs feel their competitors in the developed countries have huge advantage in terms of basic facilities. In addition they get significant support from the government. Unless this is set right, it is futile to talk of FTA.

And precisely to mask this failure the UPA is embarking on such adventures

There is another yet another critical point that remains unanswered. As India contemplates legislating the Food Security Act, experts point to the lack of farm production to meet its target. In such a scenario, where is the question of exporting? In the alternative is the success of this legislation depending on benevolence of Europeans to export subsidized farm products into India?

Either way, a disaster waiting to explode in our faces!

Interestingly, a Report of the European Commission on the EU-Korea FTA concludes “the first signs are promising” and “the EU has benefited significantly and its exports to Korea are on the up.” [EU Exports to Korea increased by 37 percent while EU’s imports have marginally increased by 1 percent]

Remember, Korea is no underdeveloped country. And if this can happen to Korea, what could be the fate for an underdeveloped, under prepared and under governed country like India?

Trade, as we all understand, is between equals. Put differently, if there is a theoretical chance that trade may bring in some benefits to both the parties; it is surely a worthwhile try. Unfortunately the EU-India FTA is doomed to fail even at the hypothetical level. Why then go through this elaborate charade?

Naturally questions arise. So why is India embarking on this suicidal mission? What are its compulsions? Whose interest is our government trying to protect? Is this a parting kick of a government on the way out?

Let us watch out for the next Amul advertisement.

The author is a Chennai-based Chartered Accountant. Comments can be made to mrv@mrvv.net.in

M R Venkatesh

http://www.rediff.com/business/column/column-india-eu-fta-parting-kick-from-upa/20130412.htm