Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/gubk7mp

Supercargo is a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.

Cylinder seal found at Rakhigarhi

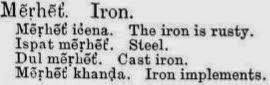

![]() Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ.kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [kā- raṇa -- ]Pa. usu -- kāraṇika -- m. ʻ arrow -- maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya -- m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ(CDIAL 3058) This Supercargo is signified by the hieroglyph कर्णक kárṇaka, kannā 'legs spread', 'person standing with spread legs'. This occurs with 48 variants. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/04/body-with-spread-legs-hypertexts-48-two.html Another hieroglyph which also signifies 'Supercargo' is 'rim-of-jar' hieroglyph', the most frequently occurring hypertext on Indus Script Corpora. See, for example, Daimabad seal. kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; Wg. kaṇə ʻ ear -- ring ʼ NTS xvii 266; S. kano m. ʻ rim, border ʼ; P. kannā m. ʻ obtuse angle of a kite ʼ (→ H. kannā m. ʻ edge, rim, handle ʼ); N. kānu ʻ end of a rope for supporting a burden ʼ; B. kāṇā ʻ brim of a cup ʼ, G. kānɔ m.; M. kānā m. ʻ touch -- hole of a gun ʼ.(CDIAL 2831)

Thus, the two hieroglyphs: 1.spread legs and 2. rim of jar are conclusive determinants signifying language used by the artisans: Prakrtam (mleccha/meluhha) and the underlying language basse for the hypertexts of Indus Script Corpora.

Supercargo is a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.

Cylinder seal found at Rakhigarhi

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.

Fish+ crocodile: aya, ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; karA 'crocodile'rebus:khAr 'blacksmith' dATu 'cross' rebus: dhAtu 'ore,mineral' śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ.rebus: seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master (Pali) sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'.Sign 186 *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul -- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ.kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [

Thus, the two hieroglyphs: 1.spread legs and 2. rim of jar are conclusive determinants signifying language used by the artisans: Prakrtam (mleccha/meluhha) and the underlying language basse for the hypertexts of Indus Script Corpora.

Rakhigarhi extending over 350 hectares is the largest site of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. Two seals with identical messages found in both Rakhigarhi and Banawali signify a karNika, Supercargo (functionary of the metalwork guild; Rebus kañi-āra '

I suggest that both Rakhigarhi seal and Banawali seal convey the identical message signifying a Supercargo (karNika), with a seafaring vessel (cargo boat), supervising the merchandise of dhAtu 'strands of rope' rebus: dhAtu 'minerals' from a fire--altar; sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' (Hieroglyph: gaNDa 'four'Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' khaNDa 'implements') PLUS ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron, ayas 'metal' PLUS adaren 'lid' rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal'.PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coin, coiner, coinage'. The tiger is horned: koD 'horn' rebus: koD 'workshop' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' kolle 'blacksmith' Thus, horned tiger signified smelter-workshop of blacksmith. The Supercargo karNika, signified with the standing person with legs spread is shown as possessing a sangaDa 'a cargo boat'. Hieroglyph: सांगड sāṅgaḍa lathe, portable furnace Rebus: sangaDa 'cargo boat'.

Banawari. Seal 17. Text 9201 Found in a gold-silversmith's residence.. Hornd tiger PLUS lathe + portable furnace. Banawali 17, Text 9201 Find spot: “The plan of ‘palatial building’ rectangular in shape (52 X 46 m) with eleven units of rooms…The discovery of a tiger seal from the sitting room and a few others from the house and its vicinity, weights ofchert, and lapis lazuli beads and deluxe Harappan pottery indicate that the house belonged to a prominent merchant.” (loc.cit. VK Agnihotri, 2005, Indian History, Delhi, Allied Publishers, p. A-60)

Message on metalwork: kol ‘tiger’ (Santali); kollan ‘blacksmith’ (Ta.) kod. ‘horn’; kod. ‘artisan’s workshop’ PLUS śagaḍī = lathe (Gujarati) san:gaḍa, ‘lathe, portable furnace’; rebus: sangath संगथ् । संयोगः f. (sg. dat. sangüʦü association, living together, partnership (e.g. of beggars, rakes, members of a caravan, and so on); (of a man or woman) copulation, sexual union.sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage, and so on. --karun -- करुन् । सामग्रीसंग्रहः m.inf. to collect the ab. (L.V. 17).(Kashmiri)

Hieroglyph multiplex: gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' aDaren 'lid' Rebus: aduru 'native metal'

Hieroglyph: sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop'

Hieroglyph: dhāˊtu 'strand' Rebus: mineral: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M.dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773).

Alternative: Hieroglyhph: Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ Rebus: M. goṭ metal wristlet ʼ P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; (CDIAL 4271)

Hieroglyph-multiplex: body PLUS platform: meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' PLUS Hieroglyhph: pī˜ṛī ʻplatform of lingamʼ Rebus: Mth. pĩṛ, pĩṛā ʻlumpʼ Thus, the message of the hieroglyph-multiplex is: lump of iron. कर्णक kárṇaka, kannā 'legs spread', Rebus: karNika 'Supercargo'' merchant in charge of cargo of a shipment, helmsman, scribe. Rebus kañi-āra '

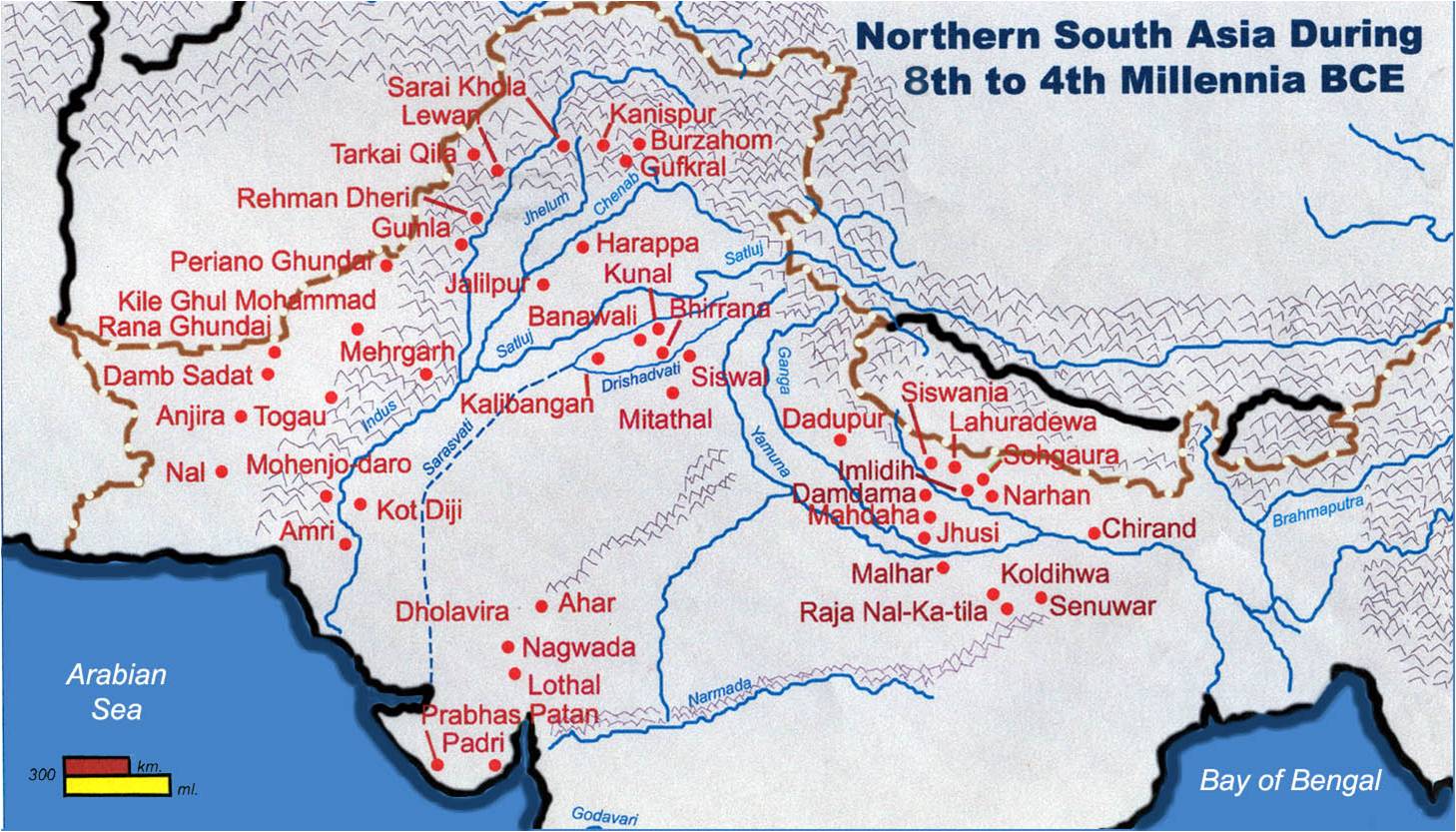

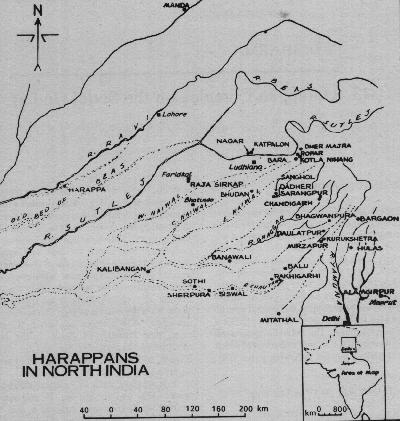

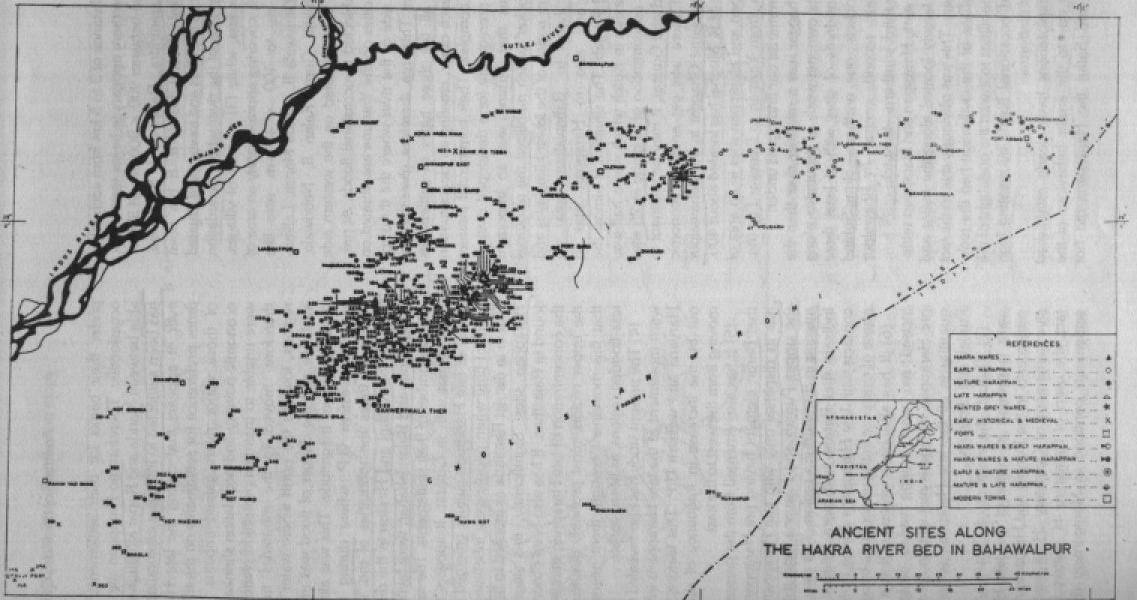

Citadel Within the citadel of Rakhigarhi (RGR-2), mud-brick podiums like those at Kalibangan have been found. Here the podium has in-built oblong pit chambers, used possibly for ritualistic purpose. These chambers have deposits of charcoal bits.and cattle bones. In another fire altar of Rakhigarhi (RGR-2) the floor and niches were coated with mud plaster. Significantly, a terracotta bull figurine has been found.on the floor near the western niche. Most likely, the structure was a place of worship, and the bull a sacred, revered animal. Next to this structure, a T-shaped fire altar with carved ends has been found. Fire altars (Rakhigarhi) To the north, in the same alignment, a brick-lined redctangular pit containing animal bones predominantly of the bovine family has been found. Almost from the same level three circular fire altars positioned in a semi-circular fashion reminiscent of those at Banawali have been excavated. Fine brushing over the surface of these altars has revealed white patches of possibly burnt hard shell of fruits offered at the fire altar. Nearest to Rakhigarhi, gold panning or washing has been known in the upper reaches of Sutlej and Beas. Published: January 7, 2016 00:00 IST | Updated: January 7, 2016 02:06 IST January 7, 2016 Rakhigarhi could unlock mystery of Indus civilisationTo the casual onlooker, Rakhigarhi is unimpressive. Yet the fields around and under this Indian village in Haryana are set to deliver the answer to one of the deepest secrets of ancient times Wazir Chand is explaining life 4,000 years ago. He points to the rocky mounds looming over a huddle of brick houses, a herd of black buffalo and a few stunted trees. A low rise was a fortification, Chand says, and a darker patch of red earth hides the site of an altar. He points to a slight depression. This, apparently, was a pit that may have been a reservoir. To the casual onlooker, Rakhigarhi is unimpressive. Yet the rubbish-strewn mounds and fields around and under this Indian village are set to deliver the answer to one of the deepest secrets of ancient times. Rakhigarhi is a key site in the Indus Valley civilisation, which ruled a more than 1m sq km swath of the Asian subcontinent during the bronze age and was as advanced and powerful as its better known contemporary counterparts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have learned much about the civilisation since it was discovered along the Indus river in present day Pakistan about a century ago. Excavations have since uncovered huge carefully designed cities with massive grain stores, metal workshops, public baths, dockyards and household plumbing, as well as stunning distinctive seals. But many perplexing questions remain unanswered. One has stood out: who exactly were the people of the Indus civilisation? A response may come within weeks. “Our research will most definitely provide an answer. This will be a major breakthrough. I am very excited,” said Vasant Shinde, the archaeologist leading the current excavations at Rakhigarhi, which was discovered in 1965. Shinde’s conclusions will be published in the new year. They are based on DNA sequences derived from four skeletons — of two men, a woman and a child — excavated eight months ago and checked against DNA data from tens of thousands of people from all across the subcontinent, central Asia and Iran. “The DNA is likely to be incredibly interesting and it has the potential to address all sorts of challenging questions about the population history of the people of the Indus civilisation,” said Dr. Cameron Petrie, an expert in south Asian and Iranian archaeology at the University of Cambridge. The origins of the people of the Indus Valley civilisation has prompted a long-running argument that has lasted for more than five decades. Some scholars have suggested that they were originally migrants from upland plateaux to the west. Others have maintained the civilisation was made up of indigenous local groups, while some have said it was a mixture of both, and part of a network of different communities in the region. Experts have also debated whether the civilisation succumbed to a traumatic invasion by so-called “Aryans” whose chariots they were unable to resist, or in fact peaceably assimilated a series of waves of migration over many decades or centuries. The new data will provide definitive answers, at least for the population of Rakhigarhi. Shinde said Rakhigarhi was a bigger city than either Mohenjo-daro or Harrapa, two sites in Pakistan previously considered the centre of the Indus civilisation. Disappearance The Indus Valley civilisation flourished for three thousand years before disappearing suddenly around 1500 BC. Theories range from the drying up of local rivers to an epidemic. Recently, research has focused on climate change undermining the irrigation-based agriculture on which an advanced urban society was ultimately dependent. Soil samples around the skeletons from which samples were sent for DNA analysis have also been despatched. Traces of parasites may tell archaeologists what the people of the Indus Valley civilisation ate. Three-dimensional modelling technology will also allow a reconstruction of the physical appearance of the dead. “For the first time we will see the face of these people,” Shinde said. In Rakhigarhi village, there are mixed emotions about the forthcoming revelations about the site. Chand, the self-appointed guide and amateur expert, hopes the local government will finally fulfil longstanding promises to build a museum, an auditorium and hotel for tourists there. “This is a neglected site and now that will change. This place should be as popular as the Taj Mahal. There should be hundreds, thousands of visitors coming,” Chand told the Guardian. The inhabitants of today’s Rakhigarhi lack many of the facilities enjoyed by those who lived there in the bronze age. Raj Bhi Malik, the village head, sees an opportunity to develop more than the site’s ancient heritage. “We want a museum and all that certainly, but also clean drinking water, proper sanitation, an animal hospital, a clinic too,” Malik said.— © Guardian Newspapers Limited, 2016 At a glance Rakhigarhi in Haryana is a key site in the Indus Valley civilisation. The civilisation ruled more than 1m sq km swath of the Asian subcontinent during the bronze age. It was as advanced and powerful as its better known contemporary counterparts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have learned much about the Indus Valley civilisation since it was discovered along the Indus river in present day Pakistan about a century ago. Excavations have since uncovered huge carefully designed cities with massive grain stores, metal workshops, public baths, dockyards and household plumbing, as well as stunning distinctive seals. But many perplexing questions remain unanswered. Printable version | May 29, 2016 8:02:07 PM | http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-in-school/rakhigarhi-could-unlock-mystery-of-indus-civilisation/article8073884.ece Haryana discovery that promises to challenge our ancient historyMAJID SHEIKH — UPDATED MAY 05, 2015 09:18AM  -Flickr What do you think our forefathers – the Harappans — looked like? A group of Indian archaeologists who are looking to answer this intriguing question are increasingly assuming that the people of the Indus Valley came from India. This assumption, as any serious archaeologist will tell you, flies in the face of current archaeological evidence. The discovery of a Harappan site at Rakhigarhi in Haryana, India, by archaeologists of the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, Pune, has set the Indian academic world alight. This has been classified as a ‘Mature Harappan Period’ find, dating 4,000 to 4,500 years old. The excitement is over the announced discovery of four skeletons, two men, a woman and a child. Dr Vasant Shinde, vice-chancellor of the college and director of the Rakhigarhi excavation, on Saturday announced and as reported by Indian newspaper: “We want to study the DNA of the Harappan people and try to find out who they were. So we excavated the skeletons scientifically at Rakhigarhi. There was no contamination. All the four skeletons are in good condition. The facial bones of two skeletons are intact. We are going to show the world how the Harappan man looked like. This will happen in July. It will be a breakthrough in Harappan studies.” “…using the DNA to be extracted from the four full-sized skeletons excavated… and a novel software developed in South Korea, archaeologists of the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, Pune, are confident of projecting, in a few months, how the Harappans looked like 4,500 years ago — their build, the colour of their skin or hair, their facial features and so on”. The archaeologists of the Deccan institute, and Haryana’s Department of Archaeology, have stated that the skeletons belonged to the Mature Harappan period (2600 BCE-1900 BCE). The tests will be done by the college staff and forensic scientists of Seoul National University, South Korea. Rakhigarhi is in Hisar district. The site has 21 trenches and four burial pits. Dr Shinde, a specialist in Harappan civilisation has excavated Harappan sites at Farmana, Girawad and Mitathal, all in Haryana. He says: “The 21 trenches yielded typical Harappan painted pottery, including goblets, terracotta figurines of wild boar and dogs, and furnaces and hearths that provided evidence of a bangle- and bead-making industry”. The Indians have announced to the academic world that the latest Rakhigarhi finds establish it as the biggest Harappan civilisation site. Until now Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan was the largest among the 2,000 Harappan sites known to exist in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The archaeological remains at Mohenjo-daro extend around 300 hectares. Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and Ganweriwala (all in Pakistan) and Rakhigarhi and Dholavira (both in India) are ranked as the first to the fifth biggest Harappan sites. With the discovery of two additional mounds, the total area of the Rakhigarhi site is 350 hectares, making it the largest. Dr Shinde says: “It was earlier thought that the origin of the early Harappan phase took place in Sind, in present-day Pakistan, because many sites had not been discovered then. In the last ten years, we have discovered many sites in Haryana, and there are at least five Harappan sites such as Kunal, Bhirrana, Farmana, Girawad and Mitathal, which are producing early dates and where the early Harappan phase could go back to 5000 BCE. We want to confirm it. “Rakhigarhi is an ideal candidate to believe that the beginning of the Harappan civilisation took place in the Ghaggar basin in Haryana and it gradually grew from here. If we get the confirmation, it will be interesting because the origin would have taken place in the Ghaggar basin in India and slowly moved to the Indus valley. That is one of the important aims of our current excavation at Rakhigarhi.” This in a nutshell is what the Indian scientists working at Rakhigarhi are saying about their finds. My view is that when scientists have pre-determined aims in matters of archaeology, then it is suspect. The declarations will have to wait until ‘verifiable’ findings. That is only fair. Scientists, archaeologists and early period historians in Lahore, where a considerable amount of Harappan period work has taken place and materials exist, as well as experts working in the University of Cambridge in England one has come in contact with in the purse of a research, take a sedate view of the theory that is being proposed by the Indians. So where does the problem lie? First, is the accepted theory: This states that the two major migrations in history, the Mediterranean-Australiods (Dravidians) migrations almost 20,000 years ago, and the Aryan movement of people almost 7,000-4,000 years ago, were both eastward movement of populations under varying circumstances. The entire work by all the ‘greats’ of Harappan archaeology have stated this. No evidence, so far, including massive amounts of very recent research work using, among other techniques, DNA technology, has suggested a westward movement. If anything they have confirmed the eastward drift. Even the classic epics of the sub-continent clearly suggest an eastward movement. Secondly, there is the irrefutable evidence of excavated sites in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Take Mehrgarh in Balochistan as an example. This site is clearly 9,500 years old. New carbon-dating technology has suggested a 12,000-10,000 year timeline for Mehrgarh. Did Mehrgarh and Mohenjo Daro come after Rakhigarhi? Surely no one is going to buy such an assumption in a hurry. Harappa itself is an early period find, that being 3,000 BCE or 5,000 years plus old. The other finds in Pakistan, and more recently in Afghanistan, point to a stable agro-based settlement people 4,500 BCE or 6,500 years ago. This is irrefutable work by internationally-recognised scientists. So though the Haryana finds are exciting, just how this point to a westward drift of populations is beyond comprehension. Let me make it very clear that this piece is not about disproving or challenging the new theories. It must be said that some of the latest assertions about ‘Hindu inventions and discoveries’ thousands of years ago are best left alone. Scientific verification will take care of them. Then why this westward drift of populations theory being proposed by Dr Shinde? Is it to disprove the irrefutable fact that the Hindu religion was born in the lands that today make up Pakistan? Is it to dispute the irrefutable fact that all the holy books of the Hindu religion were based and written in the lands of Pakistan? Is it to disprove the irrefutable fact that almost all the people of India, thousands of years ago, came from the lands that are today Pakistan? The lack of excavation work in Pakistan, the dearth of credible archaeologists working in Pakistan, the security situation restricting scientists from all over the world from working in Pakistan, and the lack of a knowledge-based environment, has created a vacuum in rational scientific thinking. Narrow ‘belief-based’ thinking by alleged scientists and intellectuals has narrowed the world of Pakistani scholarship. We must accept this shortcoming of ours. But then we must all accept that over the eons the subcontinent was an island that crashed into Asia, creating the Himalayas and providing the homo-erectus with fertile grounds to move eastwards, and that the melting of the ices meant our ancestors from Africa coming to possess the empty lands as they existed, followed much later by the Slavic peoples, who overwhelming them pushed them eastwards. We must surely consider that religions are beliefs which are not verifiable. We must accept that our history is a continuum and does not end or start in any timeframe. What evidence Haryana provides we must consider dispassionately. At the moment, it seems and I can be wrong, that this find at Rakhigarhi is providing the rising power of revisionist Hinduism with a chance to alter the very assumptions on which scientific verifiable research about our collective past takes place. It is a short-term success that might grip a few. In the end truth has to prevail, as it has to prevail in Pakistan. Published in Dawn, May 5th, 2015 Published: May 3, 2015 00:00 IST | Updated: May 3, 2015 05:53 IST CHENNAI, May 3, 2015 Virtual Harappans to come alive Two of the four skeletons — dating back to the 4500-year-old Harappan era — found recently in a burial mound at Rakhigarhi village in Haryana.— Photo: AFP Marriage of genetic and software tech to project their likenessUsing the DNA to be extracted from the four full-sized skeletons excavated from a Harappan site at Rakhigarhi in Haryana and a novel software developed in South Korea, archaeologists of the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, Pune, are confident of projecting, in a few months, how the Harappans looked like 4,500 years ago — their build, the colour of their skin or hair, their facial features and so on. In a joint excavation, archaeologists of the Deccan College, a deemed university, and Haryana’s Department of Archaeology excavated the skeletons in March. They belonged to the Mature Harappan period (2600 BCE-1900 BCE). The skeletons were those of two men, one woman and a child. The tests will be done by the college staff and forensic scientists of Seoul National University, South Korea. Vasant Shinde, Vice-Chancellor of the college and director of the Rakhigarhi excavation, said: “We want to study the DNA of the Harappan people and try to find out who they were. So we excavated the skeletons scientifically at Rakhigarhi … There was no contamination. All the four skeletons are in good condition. The facial bones of two skeletons are intact. We are going to show the world how the Harappan man looked like. This will happen in July. It will be a breakthrough in Harappan studies.” Rakhigarhi is a big Harappan site, 25 km from Jind in Hisar district. Twenty-one trenches, besides four burial pits, were dug during the excavation that began on January 23 and lasted till April-end. Dr. Shinde, who is a specialist in Harappan civilisation and has excavated Harappan sites at Farmana, Girawad and Mitathal, all in Haryana, said the chemical tests would be done on the bones to find out what kind of health the Harappans enjoyed, the diet they had and the causes of their death. The four burial pits with the skeletons had a variety of ritual pottery. The 21 trenches yielded typical Harappan painted pottery, including goblets, terracotta figurines of wild boar and dogs, and furnaces and hearths that provided evidence of a bangle- and bead-making industry. Printable version | May 29, 2016 4:04:03 PM | http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/virtual-harappans-to-come-alive/article7165745.ece http://haryanasamvad.gov.in/store/document/HR%20%20Review%20JUNE%202015.pdf Harappa’s greatest centre sheds light on our today |

Vasant Shinde, Professor of Archaeology at Deccan College, Pune, speaks to Pawanpreet Kaur about Rakhigarhi, conceivably the largest centre of the Harappan civilisation. |

PAWANPREET KAUR 16th Sep 2012 |

|  The excavated site at Rakhigarhi hat can you tell us about Rakhigarhi? Rakhigarhi is a village in Hisar district, Haryana, around 150 kilometres from Delhi. Our excavations have revealed it is the largest Harappan Civilisation site in the Indian subcontinent, with an estimated area of 400 hectares, which is 100 hectares more than any other known site. It is situated near the dry bed of Ghaggar (a section of Saraswati), which once flowed here. What led to its discovery? After the Partition, archaeologists began a systematic survey for Harappan sites along the Indo-Pak border. Archaeologists like J.P. Joshi, B.B. Lal, B. K. Thapa and A. Ghosh were convinced that sites like Mohanjodaro and Harappa were to be found here. Around 1963, Suraj Bhan, who was doing his PhD then, discovered that the village of Rakhigarhi was the site of an extensive Harappan city, in fact it was one of the early Harappan settlements. At first, no one was ready to accept its size, but after excavations were carried out between 1997 and 2000, people began to believe. How were scholars able to determine the extent of the site at Rakhigarhi? In addition to traditional methods of excavation, we used ground penetration radar (GPR), which uses electromagnetic radiation to image upto 20 metres of the subsurface. The digging has been followed up with scientific analysis of data and artefacts in the Deccan College laboratories. What have excavations in the region revealed? We have found typical Harappan features: town planning, wide roads (wider than Kalibangan), brick lined drains for sewage, pits that were used for sacrificial or religious purposes, a gold foundry and furnace, thousands of semi-precious stones and tools and a burial site with skeletons and their belongings. What makes you sure that Rakhigarhi belongs to the early Harappan phase? The artefacts we found point to Early and Mature Harappan phases, especially the pottery. We found deposits of Hakra ware, which is typically found in the Early Harappan phase. As against this, the pottery from the Mature phase has painting, Harappan motifs and even some letters from its script. In addition to this, the impressive number of pottery pieces, terracotta statues and seals, needles, fish hooks, weights and bronze artefacts that we have found all point to this particular phase. In fact, some major discoveries from the Harappan period have pushed back its antiquity by several hundred years.

Have excavations in Rakhigarhi shed light on other discoveries made at Mohanjodaro and Harappa? There is a misconception that the Harappan civilisation was homogenous. That is far from the truth. There are distinct signs of regional diversity, especially in town planning, disposal of the dead, in artefacts and so on. For instance, the skeletons we found at Rakhigarhi's burial ground all had their heads turned to the north. And, in the seals, the animals' faces are turned to the right instead of the left, as seen in the seals found in Mohanjodaro and Harappa. Each region had distinct features but these need to be studied more extensively. What is significance of Rakhigarhi in the study of the Harappan Civilisation?  While most Western scholars think that Harappan civilisation originated in Sindh, we are increasingly discovering that there could have been important sites that not just predate these but could have existed around the same time as Mohanjodaro and Harappa. So, Rakhigarhi is an important site to study the evolution of the Harappan civilisation itself. Also, given its size, strategic location and proximity to the Khetri belt in Rajasthan, which has a rich reserve of copper, Rakhigarhi may well have been an important trade centre, especially of semi-precious stones or at least a significant trade route. Also, I feel it may have also been an important point of contact with the contemporaneous non-Harappan, non-urban cultures. What is the condition of the site today? Of the seven mounds at the site, three have been fenced and security arrangements put in place. One is under occupation (people are living there and it is impossible to move them), one is under cultivation and one is quite intact. We are trying to stop encroachments from the village, which is the single biggest threat to this site. And instead of using formulaic methods of Western laboratories, we are trying to determine indigenous methods to ensure the preservation of these structures using locally available material. But, I think at one level archaeological research has been flawed because scholars tend to focus only on the bigger sites. For instance, of the 2000 Harappan sites we have discovered so far, only five are cities. And yet, they have hogged all the limelight. There are other industrial and rural allied centres that deserve as much attention. Has Rakhigarhi been able to shed any light on the theory of the origin and history of Aryans? It is an intriguing question, one that can be understood only by identifying the actual cultural sequence of the Ghaggar/Saraswati. There are different hypotheses as regards the identity of the people who thrived on the banks of the Saraswati. Some people believe these were Aryans while others insist they were non-Aryans. My argument is that from 7000 BC onwards, we don't have any evidence of people migrating. If we say the Aryans came from outside, it should reflect in their lifestyle. From 7000 BC onwards, we have been able to observe that they are the same people. Studying Rakhigarhi has been a study of their legacy. The model Haryana household today is exactly how the households of people must have been thousands and thousands of years ago. There are too many similarities between modern day and ancient Rakhigarhi to ignore. What future works do you plan to undertake in Rakhigarhi? Aside from the excavations and analysis, we are trying to stop encroachments and trespassing by involving the villagers. You know, in 1965, 250 sites were identified in the basin. Today, only one or two of those are left. At first the villagers viewed us with suspicion. They thought if we found something the government would take away their land. Or that we were after the treasures buried in the ground. But when they saw us collecting bones and pieces of pottery, they were convinced we were doing serious work. Once they realised what the excavation meant, they took immense pride in the history of their village. So, we are now trying to promote Rakhigarhi as a historical tourism destination and for this we are involving villagers in activities like artefact-replica production, training as guides and so on. We are also trying to build an onsite museum and a research facility with an extensive training programme for students. Former Archaeological Survey director sentenced to jail for fraud