Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/gsmdadn

Indus Script Corpora recorded metalwork catalogues, while Egyptian hieroglyphs recorded names. Both used rebus principle, 'orthographic metaphor'.

Rebus principle in writing systems can be explained as 'orthographic metaphors' or hypertext cipher or hieroglyph-multiplex cipher key in Meluhha speech forms.

I agree with Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale who see a hypertext formation in an orthographic form of a composite animal made up of body parts. For example the hieroglyph-multiplex on Mohenjo-daro Seal m0300 which ligatures a human face to body parts of a bovine with horns and other attributes. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/itihasa-of-bharatam-janam-traced-from.html

Metaphor is a figure of speech in which a term or phrase is applied to something to which it is not literally applicable in order to

suggest a resemblance, as in “TvastA had a son called Tris'iras, 'three heads' (Rigveda)”. One possible explanation is that TvaSTA had three principal functions, as a carpenter, as a smith, as a Supercargo of a seafaring vessel.

The 'figure of speech' is for rhetorical effect signifying hidden similarities between two ideas. Bronze Age was an industrial revolution of an extraordinary order. The revolution created a demand for new metal products and supply chains were established by corporate entities called s'reni, guilds of artisans and merchants. When a catalogue had to be prepared for the resources used (mere earth and stone melted in fire, in furnaces) and products produced, words had to be conveyed. Figures of speech or metaphors were a rhetorical means to convey information of such catalogues.

A metaphor unlike a simile directly equates two or more ideas. Thus when a feeding trough is shown in front of a wild animal on Indus Script Corpora, the metaphor is a direct equation between two ideas: words associated with hieroglyphs and similar sounding words associated with metalwork. Patthar is a feeding trough. A similar sounding word pattharika is a merchant. Thus an orthographic metaphor is created in an innovative writing system using rebus, that is homonym words intended to be phonetic determinants of the Bronze Age metalwork idea sought to be conveyed.

Vasdhaiva kutumbakam is an example of a literary metaphor.This does NOT mean that the globe is literally a family. It is an expression intended to convey that the behaviour of the people within this space (globe) is such as would be seen in members of a family.

Takṣat vāk, is a Rigveda expression literally translated as ‘incised speech’. This is a literary metaphor. Such Takṣat vāk as incised hieroglyphs on Indus Script Corpora are signifiers of Meluhha speech related to metalwork. Together the incised words constitute metalwork catalogues.

In orthographic tradition of Indus Script Corpora, such metaphors are expressed as hieroglyphs read rebus to signify metalwork catalogues. A Richards (1937) in The Philosophy of Rhetoric explains that a metaphor has two parts: the tenor and the vehicle. The tenor is the subject to which attributes are ascribed. In the Vasudhaiva kutumbakam example, vasudha, 'globe' is the tenor. The vehicle is kutumbakam, 'family'. The objective is to suggest components of behaviour in a family. While a simile asserts similarity, a metaphor compared identical attributes.

Rebus is a metaphoric form. An orthographic rebus, as a writing system, uses pictures to represent words or parts of words. Thus a fish as a hieroglyph is a rebus signifier. ayo 'fish' has homonyms aya 'iron' or ayas 'metal'; khambhaṛā 'fin of fish' rebus: kammaṭa 'coiner, coinage, mint'. Thus, by signifying fin of fish, the signifier conveyed is kammaTa 'mint'. Non verbis, sed rebus, is a Latin expression which signifies "not by words but by things'. Orthographic rebus are hieroglyphs signified on Indus Script Corpora.

In a writing syste, rebus refers to the use of pictograms to represent syllabic or morphemic sounds or sounds of words themselves used in common parlance, or social conversations. This rebus method is a precursor to the use of phonographs to signify alphabets. Champollion hs demonstrated the use of rebus in Egyptian hieroglyphs. "In linguistics, the rebus principle is the use of existing symbols, such as pictograms, purely for their sounds regardless of their meaning, to represent new words. Many ancient writing systems used the rebus principle to represent abstract words, which otherwise would be hard to be represented by pictograms." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rebus

A statue of Rameses shows: Ra; the child, mes; and the sedge plant (stalk held in left hand). Read together, the sounds signified by the pictures a new word emerges to suggest the name: Ra- mes- su. Thus, what is signified is NOT the sedge plant held by a child, but by similar sounding words for the name of a person: Rameses.

![]() Ramesses II as child: Hieroglyphs:Ra-mes-su.

Ramesses II as child: Hieroglyphs:Ra-mes-su.

Executive summary

Executive summary

As Sigmund Freud noted, the dream is a rebus.

A rebus is an allusional device that uses pictures to represent words or parts of words.

So, too a Meluhha hieroglyph is a rebus, a writing system on Tin Road of Bronze Age extending from Ashur on Tigris river to Kanesh (Kultepe, Anatolia).

It is a travesty of scholarship to call such a rebus writing system as 'illiterate' or 'proto-literate' because the rebus method is made up at least two vocables: one vocable denoting the picture and the other similar sounding vocable denoting the solution to the puzzle that is, the cipher.

Works of art with picture-puzzles make Meluhha, a Visible language. Rebus, a code of literacy, yields meanings of Meluhha hieroglyphs. Such a cipher is attested by Vātsyāyana (ca. 6th century BCE work) as mlecchita vikalpa (that is, alternative rendering of Meluhha/Mleccha speech or vocables -- and listed as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth as vidyāsamuddeśa, 'chief branches of knowledge').

Vocable is a sememe or a word that is capable of being spoken and recognized meaningfully.

A vivid representation of the rebus principle of literacy is provided by Narmer Palette. (Egyptian hieroglyphs: N'r 'cuttle-fish' + m'r 'awl' Rebus: Nar-mer, name of king.)

A dream is a rebus. History of Civilizations of ancient times has a record of two remarkable dreams: the first is the dream in the Epic of Tukulti-Ninurta and the second is the dream of Māyā, mother of Gautama Buddha.

There are thousands of picture-puzzles which occur on cylinder seals of Ancient Near East which are explained on many Museum catalogs as banquet scenes or animal hunts or war scenes. Many of these picture-puzzles are indeed rebus or comparable to the interpretation of dreams and attempts have not been made to identify the possible language groups who might have deployed such picture-puzzles, principally during the Bronze Age.

Rebus signifiers and the signified relate to innovations of the Bronze Age such as: bronze/brass alloys to substitute for arsenical copper, casting methods (such as cire perdue casting), alloying ores such as tin, zinc, lead and exchanges along the Tin Road set up by Meluhha artisans/traders also called Assur as metal smelters par excellence.

It will be a leap of faith to assume that the picture-puzzles are nonsensical or belong to pro-literate cultures because a contemporary observer is unable to decipher the cipher.

While early tokens and bullae (token envelopes) were recognized as ancient accounting methods and categorisation of products, the Proto-Elamite script yet remains undeciphered.

Robert K. Englund provides a succinct state of the art report on Proto-Elamite: "(Tokens) These clay objects consist on the one hand of simple geometrical forms, for instance cones, spheres, etc. and on the other, of complex shapes or of simpler, but incised, forms. Simple, geometrically formed tokens were found encased within clay balls (usually called 'bullae') dating to the period immediately preceding that characterized by the development of the earliest proto-cuneiform texts; these tokens most certainly assumed numerical functions in emerging urban centers of the late fourth millennium BCE...a strong argument from silence can be made that Sumerian is not present in the earliest literate communities, particularly given the large numbers of sign sequences which, with high likelihood, represent personal names and thus should be amenable to grammatical and lexical analyses comparable to those made of later Sumerian onomastics...large numbers of inscribed tablets...which for purposes of graphotactical analysis and context-related semantic categorization of signs and sign combinations represents a text massof high promise...we can utilize language decipherments from texts of later periods in working hypotheses dealing with the linguistic affiliation of archaic scribes...There may, however, have been much more population movement in the area than we imagine, including early Hurrian elements and, if Whittaker, Ivanov, and others are correct, even Indo-Europeans. Fn 44. Rubio (1999: 1-16 has reviewed recent publications, and the pioneering initial work by Landsberger on possible substrate lexemes in Sumerian, and concludes that the fairly extensive list of non-Sumerian words attested in Sumerian texts did not represent a single early Mesopotamian language, but rather reflected a long history of Wanderworter from a myriad of languages, possibly including some loans from Indo-European, and many from early Semitic."

Major sites of Late Uruk and proto-Elamite inscriptions in Persia

Examples of simple (left) and complex (right) 'tokens' from Uruk (digital images courtesy of CDLI).

Examples of sealed (top), sealed and impressed (middle) bullae, and a 'numerical' tablet (all from Susa--top: Sb 1932; middle: Sb 1940; bottom: Sb 2313; digital images courtesy of CDLI).

Development of cuneiform, after Schmandt-Besserat (1992).

At the same site of Susa a pot was discovered unambiguously defining the meaning of the hieroglyph which adorned the mouth of the pot since the pot contained metal artifacts (reported by Maurizio Tosi):

The 'fish' hieroglyph shown on this pot is a Meluhha hieroglyph ayo 'fish' (Munda) Rebus ayo 'alloy metal' (Gujarati; ayas, Sanskrit).

In this evolutionary scheme of 'writing systems' shown on the chart after Schmandt-Besserat-- call them proto-literate or illiterate -- depending upon the definitions assumed for the term 'literate' -- a parallel development ca 3500 BCE is left out: the formation and evolution of Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus writing). The date of ca 3500 BCE is related to the first evidence of writing identified in Harappa excavations by HARP with the following potsherd with a dominant hieroglyph, signifying tabernae montana fragrant wild tulip read rebus:tagaraka (hieroglyph) rebus: tagara 'tin (ore)' in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund or proto-Indian).

Bronze Age innovations created by Wanderworter --seafaring and land caravans of Meluhha artisans and merchants speaking a version of Proto-Indian --result in the messaging system using hieroglyphs of Meluhha read rebus.

Forcefully refuting claims (characterised as a hoax) of 'illiteracy', Massimo Vidale argues that it is a cop-out to avoid researches into meanings of picture-puzzles by assuming that 'signs' as distinct from 'pictorial motifs' have to be either alphabets or syllables resulting in inscriptions longer than 5 signs and assuming that such glyphs cannot be read as logographs. This is shoot-and-scoot scholarship because the claimants have not so far responded to the refutation by Massimo Vidale indicating the use of the writing system in the context of trade in an extensive contact area from the Fertile Crescent to the Ganga-Yamuna river basin.

Allegedly scholarly, but disdainful,claims of 'illiteracy' do NOT cnnstitute an advance in knowledge to promote the study of now nearly 7000 artifacts with what I have called Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus script) in Ancient Near East (not counting the Tin Road related documents). Witzel et al have erred on a simple assumption that the 'signs' of the script have to be syllabic or alphabetic. They ignored the possibility that they could be logographs including the crocodile, tiger, buffalo etc.which could have been read rebus as Meluhha hieroglyphs. I have shown that almost all the so-called 'signs' and 'pictorial motis' of Indus writing are Meluhha hieroglyphs.

The average number of hieroglyphs, about 5 or 6 are adequate to represent the vocables as pictures (hieroglyphs) to support a trading system complementing the innovations of the Bronze Age stone and metalcrafts. Most of the Meluhha hieroglyphs signify metalware and stoneware together with brief accounts of methods used to smelt or forge or cast artifacts. One most frequently deployed hieroglyph is a 'standard device' shown mostly in front of a one-horned young bull. This sangaḍa hieroglyph had rebus readings:sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ; sangara ‘fortification’; jangaḍ accounting for mercatile transactions ‘goods entrusted on approval basis’.

Take for example this cylinder seal picture-puzzle:

![Inline image 1]() Cylinder seal. Provenience: Khafaje Kh. VII 256 Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BCE) Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.

Cylinder seal. Provenience: Khafaje Kh. VII 256 Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BCE) Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

karaḍa ‘panther’ Rebus: karaḍā ‘hard alloy’.khōṇḍa A stock or stump (Marathi); ‘leafless tree’ (Marathi). Rebus: kõdār ’turner’ (Bengali); kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali).

kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’.kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.) कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kole.l 'temple, smithy' (Kota.) kol = pañcalōha, a metallic alloy containing five metals (Tamil): copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Sanskrit); an alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron (dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Mangarāja’s Nighaṇṭu. 498)(Kannada) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali)

Such rebus readings are consistent with Robert K. Englund's summing up pointing to the possibility of non-Sumerian participants in the Bronze Age stoneware, metalware repertoire which constituted a veritable multi-national, industrial revolution of those times.

Tukulti Ninurta's altar with hieroglyphs happened in a domain where cuneiform was used -- say between Assur and Kanesh on Tin Road. Do the hieroglyphs on the altar mean Tukulti was illiterate? Tukulti altar displays on one side: safflower, rod on altar and on another side 2. spoked wheel. These are hieroglyphs related to bronze age alloys and fire-god karandi in Remo language (Munda family). The identification of Meluhha hieroglyphs proceeded from DT Potts' brilliant ingisht identifying tabernae montana wild tulip glyph on Tell Abraq axe, also on a vase and on a comb. TA 1649 Tell Abraq.(D.T. Potts, South and Central Asian elements at Tell Abraq (Emirate of Umm al-Qaiwain, United Arab Emirates), c. 2200 BC—CE 400. Potts' insight is complemented by the view of an archaeometallurgist who sees a link between the evolution of Bronze Age from a chalcolithic phase and the emergence of writing systems: “The Early Bronze Age of the 3rd millennium BCE saw the first development of a truly international age of metallurgy… The question is, of course, why all this took place in the 3rd millennium BCE… It seems to me that any attempt to explain why things suddenly took off about 3000 BCE has to explain the most important development, the birth of the art of writing… As for the concept of a Bronze Age one of the most significant events in the 3rd millennium was the development of true tin-bronze alongside an arsenical alloy of copper…” (J.D. Muhly, 1973, Copper and Tin, Conn.: Archon., Hamden; Transactions of Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 43, p. 221f. ) In this context, it is apposite to underscore the use of Meluhha hieroglyphs on two pure tin ingots which were discovered in a shipwreck at Haifa. (S. Kalyanaraman, 2010, The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” - Decoding Indus script as repertoire of the mints/smithy/mine-workers of Meluhha, Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Number 11, pp. 47-74).

Potts has explained further that nomadism was a remarkable phenomenon in ancient Iran. "Although evidence of 'proto-Median' agriculture and settled life may be difficult to find outside of Iran -- particularly as their 'homeland' remains vague and ill-defined -- linguistic studies suggest that some of the earliest Iranian speakers to reach the Iranian plateau did have an agricultural background and were familiar with both ploughing ad irrigation." Potts cites J. Puhvel, 'The Indo-European and Indo-Aryan plough: A linguistic study of technological diffusion,' Technology and Culture 5/2. 1964: 184-186, the posited Indo-Iraia verb stem *karś-meaning 'to plough', may have been a loanword.' (Potts 2014 - Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 75)

This hieroglyph is central to the entire corpora; it is the rosetta stone; it is a signifier tagaraka, wild fragrant tulip and the signified word is: tagara, TIN (cassiterite ore).

Massimo's arguments are convincing in the context of Wanderworter evidence from an extensive area deploying Meluhha hieroglyphs.

Massimo Vidale provided an effective rebuttal of the claim made by Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat & Michael Witzel that Harappan civilization was illiterate. (Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).

Excerpts: “My purpose is to reply to ‘The collapse of the Indus script thesis: the myth of a literate Harappan civilization’, by Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat & Michael Witzel, in Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS), 11, 2, 2004, pp. 19-57. I actually think that the Indus script was probably a protohistoric script, somehow conveying the sounds and words of one or more still unidentified languages. Although proofs are obviously lacking (the only demonstration would be a successful translation), this is the most reasonable assumption: and I must confess that I have lived so far rather content with such uncertainty…In order to decipher a lost writing system, you have to guess the language, guess the content, and you need relevant contexts on which independently and reasonably test your ideas…Farmer, Sproat & Witzel loudly stated that they have solved the mystery, that the Indus script is not writing, and that they can read or interpret part of the signs, I disagree with their arguments and, perhaps more, with the tone and language adopted by the authors…The authors would like to throw the ball to their opponents, asking them to refute their views by providing a sound decipherment in linguistic terms. But they have raised the problem, proposing a different interpretation and the first readings, and they have to provide a demonstration of their thesis by interpreting and explaining to us the symbolic sequences following the equivalent of their condition 4 (as stated at p. 48)…(but for the moment even Farmer & others will admit that their deities on vessels and seals and the solar cult advertised at Dholavira did not cost them such an impressive outburst of imagination).”

The epigraphs or artifacts so rendered as signifiers, as hieroglyphs are read rebus as Bronze Act metalware, stoneware repertoire. Cire perdue casting gets a name: dhokra (Meluhha) and the specialist artisans are calleddhokra kamar (Meluhha). Zinc is sattiya, jasta and the signifier is the svastika (sattiya). Pewter is tuthnag, the signifier includes a snake. Sharpness of alloyed metal derived from alloying is padm, the signifier is the snake-hood, paṭam.Meluhha artisans and traders operating along the Tin Road had carried with them the signifiers and signifieds and deployed them as epigraphs or artifacts to convey what they were specialists in. They had also produced 1. the flagposts found in Nahar Mishmar arsenical copper artifacts and 2. the leopard weights of Shahi Tump (Baluchistan).

Both the dreams are narrated in ancient texts and also on sculptures and epigraphs. The ancient texts describe the life-activities which the dreams signified. The hieroglyphs used on sculptures ad epigraphs provide for rebus representations of the dreams.

Rebus readings of the images (signifiers) yield the glosses related to life-activities (signifieds).

Both the dreams are presented in visible language of Meluhha using hieroglyphs, read rebus.

Dream of Tukulti-Ninurta and Māyā's dream are signified by visible language

"The dream is a rebus." (Freud, Sigmund, 1959, Interpretation of Dreams, p. 1).

One method of derivings meanings of the symbolism in dreams (or unconscious thought) is rebus.

Defining rebus as a picture-puzzle, Sigmund Frued elaborates the concept of displacement of emphasis and affect: "A correct judgment of the picture-puzzle results only if I make no such objections to the whole and its parts, but if, on the contrary, I take pains to replace each picture by the syllable or word which it is capable of representing by means of any sort of reference, the words which are thus brought together are no longer meaningless, but may constitute a most beautiful and sensible expression. Now the dream is a picture-puzzle of this sort, and our predecessors in the field of dream interpretation have made the mistake of judging the rebus as an artistic composition. As such it appears nonsensical and worthless." (Freud, Sigmund, 1913, Trans. by AA Brill, Interpretation of Dreams, Chapter VI, The dream-work, New York, The Macmillan Company http://www.bartleby.com/285/6.html)

The meanings of the visible images are signified by rebus readings of Meluhha language of Assur (Ancient Near East and Ancient India).The signifier of Māyā's dream is an elephant. The word which signifies an elephant is ibha(Meluhha~Sanskrit). Rebus reading provides the signified: ib 'iron'. This is a condensation of the life activities of Māyā's clan, koliya, Koliya are koles, who are iron workers of yore from several generations. Her unconscious thought conditioned by the life of iron workers and smelters who were associated with her lineage identifies them by the product of their labour, ib 'iron'. The signifier for this life-activity of working in iron isibha, 'elephant'.

The inscription on the Tukulti Ninurta altar says: god Nusku.

The image is that of an ancestor of Tukulti Ninurta -- ancestor remembered in his dream?-- kneeling before the empty throne of the fire-god Nusku, occupied by what appears to be a flame.

Interpretation of the dream as rebus yields the meaning, the prayer is to fire-god Karandi. So, what is depicted is a flame while signifying the fire-god Karandi. In Meluhha language, the rebus reading of a clump of wood is करंडा [karaṇḍā].

Tukulti Ninurta's ancestor is an Assur, yes, the Assur whose lineage continues to be called Assur in some parts of India: Chattisgarh, Bastar, Santal paraganas, speaking an Asuri language (Meluhha dialect in the Munda language traditions of Indian sprachbund). This is good evidence that Assur of India had travelled far and wide into on the banks of Tigris river establishing the Tin Road between Assur and Kanesh (Kultepe, Anatolia). So, unconscious thought relates to the life-activities of the Assur people on this Tin Road trading in bronze-age artifacts. Hence, the presence of the following hieroglyphs on the Tukulti Ninurta altar: 1. करडी [karaḍī] f करडई) 'Safflower':, 2. nave of spoked wheel eraka, arā (nave, spokes) carried aloft on flagposts as trade announcements. Two flagposts are shown signifying dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast (metal)'.

The trade announcements are comparable to the flagposts shown on Mohenjo-daro tablets (which show hieroglyphs of spoked wheel, scarf, one-horned young bull, lathe-portable furnace -- eraka 'copper', dul 'cast (metal),arā 'brass', dhatu 'ore', konda 'turner's lathe', sangada 'citadel, guild'.)

Signifier is hieroglyph: safflower करडी [karaḍī].

Signified is rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. A color of horses, iron grey.

The signifier of Tukulti-Ninurta's dream is a fire-altar. The narrative of the dream is associated with the messages of the dream signifiers of the signifieds, signifiers of spoked wheels, safflowers signified as hard metal alloys of copper of the Bronze age. The word which signifies a fire-altar is kaṇḍa (Meluhha~Santali) The narrative is a prayer to fire-god. How to represent this prayer in a visible language detailing the life-activities which have imbued the images and related meanings into the unconscious mind? kāṇḍa is a stem or stick of the sugarcane; such a stem or stick is shown in visible language as the center-piece of the nuska-Ninurta fire altar image before which he kneels down and prays in adoration. He prays to karandi, the fire-god, the signified for which the visible language uses the signified: the stick. karandi 'fire-god' (Munda, Remo). Signifier: करंडा [karaṇḍā] A clump, chump, or block of wood. 4 The stock or fixed portion of the staff of the large leaf-covered summerhead or umbrella. करांडा [ karāṇḍā ] m C A cylindrical piece as sawn or chopped off the trunk or a bough of a tree; a clump, chump, or block. (Marathi)

The apparent, underlying assumption in the two rebus readings is that the language which provides the glosses is Meluhha and that Tukulti-Ninurta's fire-altar and sculptors who narrated Māyā's elephant are rebus representations of the life activities of Tukulti-Ninurta's clan of Assur and Māyā's clan of Koliyas.

Visible images in works of art are signifiers. Associated words of the spoken language become the signifieds. This is the rebus code."In the Assyro-Babylonian tradition, visual representation was considered to be part of an extreme semantic constellation. Like the ideogram in the script, the visual sign had the potential of referring to a chain of referents, linked to it and to one another by a logic that may escape the contemporary viewer but that could be deciphered in antiquity through hermeneutic readings. Such readings were obviously not accessible to a general public, most of whom were most likely nonliterate; however, the potential of signs referring to other signs in a continuous chain of meanings was a knowledge not limited to the literate. The ominous nature of things was a subject of concern fo all in Babylonian and Assyrian society. It seems clear from numerous texts that signs in the environment could be read and deciphered by people other than the scholarly elite or the priesthood. For omens related to the destiny of king or country, court diviners and the priesthood studied the signs, using their scholarly knowledge of astronomy and hermeneutics. But the reading of omina in the environment was also a part of the daily lives of people in general, as we know from textual references to egirru (omens of chance utterances) or to dreams and dream interpretation. Like other signs in the world, visual images could never be seen as the relationship between one signified and one signifier. An image was a pluridimensional sign that carried latent meanings beyond the one manifest on the surface. Since many works of art were made without any intent of presentation to mortal viewers, the polyvalence inherent in their imagery was not always a code intended for a particular audience, whether literate or nonliterate, although one can imagine that the system was at times deliberately manipulated for the purposes of generating a required meaing...polyvalence was considered to be in the very nature of the image-sign. The audience or intended viewer was not of the greatest import in many cases because the work of art was put a position where it was only to be viewed by the king, his courtiers, or temple officials. In these cases whatever meanings were generated through the imagery had much less to do with the good opinion of the chance viewer than they did with the power of the image as a eans of creating an incessant presence. In attempting to catalog ancient Near Eastern images by means of an iconography of one-to-one relationships of signifiers and signifieds, of symbols and gods, for example, we have perhaps limited our readings unnecessarily in a way that the Babylonians and Assyrians would not have done." (Zainab Bahrani, 2011, The graven image: representation in Babylonia and Assyria, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, p. 185-186).

Sigmund Freud refers to a syntax of dreams noting that the pictorial language of the dream uses what Freud explains as 'condensation and displacement' (Freud 1959).

Dream depicted on Tukulti-Ninurta altar'I have revealed to Atrahasis a dream, and it is thus that he has learned the secret of the gods.' (Epic of Gilgamesh, Ninevite version, XI, 187.)The Pedestal of Tukulti-Ninurta I![]()

As Sigmund Freud noted, the dream is a rebus.

A rebus is an allusional device that uses pictures to represent words or parts of words.

So, too a Meluhha hieroglyph is a rebus, a writing system on Tin Road of Bronze Age extending from Ashur on Tigris river to Kanesh (Kultepe, Anatolia).

It is a travesty of scholarship to call such a rebus writing system as 'illiterate' or 'proto-literate' because the rebus method is made up at least two vocables: one vocable denoting the picture and the other similar sounding vocable denoting the solution to the puzzle that is, the cipher.

Works of art with picture-puzzles make Meluhha, a Visible language. Rebus, a code of literacy, yields meanings of Meluhha hieroglyphs. Such a cipher is attested by Vātsyāyana (ca. 6th century BCE work) as mlecchita vikalpa (that is, alternative rendering of Meluhha/Mleccha speech or vocables -- and listed as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth as vidyāsamuddeśa, 'chief branches of knowledge').

Vocable is a sememe or a word that is capable of being spoken and recognized meaningfully.

A dream is a rebus. History of Civilizations of ancient times has a record of two remarkable dreams: the first is the dream in the Epic of Tukulti-Ninurta and the second is the dream of Māyā, mother of Gautama Buddha.

There are thousands of picture-puzzles which occur on cylinder seals of Ancient Near East which are explained on many Museum catalogs as banquet scenes or animal hunts or war scenes. Many of these picture-puzzles are indeed rebus or comparable to the interpretation of dreams and attempts have not been made to identify the possible language groups who might have deployed such picture-puzzles, principally during the Bronze Age.

Rebus signifiers and the signified relate to innovations of the Bronze Age such as: bronze/brass alloys to substitute for arsenical copper, casting methods (such as cire perdue casting), alloying ores such as tin, zinc, lead and exchanges along the Tin Road set up by Meluhha artisans/traders also called Assur as metal smelters par excellence.

It will be a leap of faith to assume that the picture-puzzles are nonsensical or belong to pro-literate cultures because a contemporary observer is unable to decipher the cipher.

While early tokens and bullae (token envelopes) were recognized as ancient accounting methods and categorisation of products, the Proto-Elamite script yet remains undeciphered.

Robert K. Englund provides a succinct state of the art report on Proto-Elamite: "(Tokens) These clay objects consist on the one hand of simple geometrical forms, for instance cones, spheres, etc. and on the other, of complex shapes or of simpler, but incised, forms. Simple, geometrically formed tokens were found encased within clay balls (usually called 'bullae') dating to the period immediately preceding that characterized by the development of the earliest proto-cuneiform texts; these tokens most certainly assumed numerical functions in emerging urban centers of the late fourth millennium BCE...a strong argument from silence can be made that Sumerian is not present in the earliest literate communities, particularly given the large numbers of sign sequences which, with high likelihood, represent personal names and thus should be amenable to grammatical and lexical analyses comparable to those made of later Sumerian onomastics...large numbers of inscribed tablets...which for purposes of graphotactical analysis and context-related semantic categorization of signs and sign combinations represents a text massof high promise...we can utilize language decipherments from texts of later periods in working hypotheses dealing with the linguistic affiliation of archaic scribes...There may, however, have been much more population movement in the area than we imagine, including early Hurrian elements and, if Whittaker, Ivanov, and others are correct, even Indo-Europeans. Fn 44. Rubio (1999: 1-16 has reviewed recent publications, and the pioneering initial work by Landsberger on possible substrate lexemes in Sumerian, and concludes that the fairly extensive list of non-Sumerian words attested in Sumerian texts did not represent a single early Mesopotamian language, but rather reflected a long history of Wanderworter from a myriad of languages, possibly including some loans from Indo-European, and many from early

Semitic."

Major sites of Late Uruk and proto-Elamite inscriptions in Persia

Examples of simple (left) and complex (right) 'tokens' from Uruk (digital images courtesy of CDLI).

Examples of sealed (top), sealed and impressed (middle) bullae, and a 'numerical' tablet (all from Susa--top: Sb 1932; middle: Sb 1940; bottom: Sb 2313; digital images courtesy of CDLI).

Development of cuneiform, after Schmandt-Besserat (1992).

At the same site of Susa a pot was discovered unambiguously defining the meaning of the hieroglyph which adorned the mouth of the pot since the pot contained metal artifacts (reported by Maurizio Tosi):

The 'fish' hieroglyph shown on this pot is a Meluhha hieroglyph ayo 'fish' (Munda) Rebus ayo 'alloy metal' (Gujarati; ayas, Sanskrit).

In this evolutionary scheme of 'writing systems' shown on the chart after Schmandt-Besserat-- call them proto-literate or illiterate -- depending upon the definitions assumed for the term 'literate' -- a parallel development ca 3500 BCE is left out: the formation and evolution of Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus writing). The date of ca 3500 BCE is related to the first evidence of writing identified in Harappa excavations by HARP with the following potsherd with a dominant hieroglyph, signifying tabernae montana fragrant wild tulip read rebus:tagaraka (hieroglyph) rebus: tagara 'tin (ore)' in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund or proto-Indian).

Bronze Age innovations created by Wanderworter --seafaring and land caravans of Meluhha artisans and merchants speaking a version of Proto-Indian --result in the messaging system using hieroglyphs of Meluhha read rebus.

Forcefully refuting claims (characterised as a hoax) of 'illiteracy', Massimo Vidale argues that it is a cop-out to avoid researches into meanings of picture-puzzles by assuming that 'signs' as distinct from 'pictorial motifs' have to be either alphabets or syllables resulting in inscriptions longer than 5 signs and assuming that such glyphs cannot be read as logographs. This is shoot-and-scoot scholarship because the claimants have not so far responded to the refutation by Massimo Vidale indicating the use of the writing system in the context of trade in an extensive contact area from the Fertile Crescent to the Ganga-Yamuna river basin.

Allegedly scholarly, but disdainful,claims of 'illiteracy' do NOT cnnstitute an advance in knowledge to promote the study of now nearly 7000 artifacts with what I have called Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus script) in Ancient Near East (not counting the Tin Road related documents). Witzel et al have erred on a simple assumption that the 'signs' of the script have to be syllabic or alphabetic. They ignored the possibility that they could be logographs including the crocodile, tiger, buffalo etc.which could have been read rebus as Meluhha hieroglyphs. I have shown that almost all the so-called 'signs' and 'pictorial motis' of Indus writing are Meluhha hieroglyphs.

The average number of hieroglyphs, about 5 or 6 are adequate to represent the vocables as pictures (hieroglyphs) to support a trading system complementing the innovations of the Bronze Age stone and metalcrafts. Most of the Meluhha hieroglyphs signify metalware and stoneware together with brief accounts of methods used to smelt or forge or cast artifacts. One most frequently deployed hieroglyph is a 'standard device' shown mostly in front of a one-horned young bull. This sangaḍa hieroglyph had rebus readings:sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ; sangara ‘fortification’; jangaḍ accounting for mercatile transactions ‘goods entrusted on approval basis’.

Take for example this cylinder seal picture-puzzle:

Cylinder seal. Provenience: Khafaje Kh. VII 256 Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BCE) Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

karaḍa ‘panther’ Rebus: karaḍā ‘hard alloy’.

khōṇḍa A stock or stump (Marathi); ‘leafless tree’ (Marathi). Rebus: kõdār ’turner’ (Bengali); kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali).

kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’.

kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.) कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kole.l 'temple, smithy' (Kota.) kol = pañcalōha, a metallic alloy containing five metals (Tamil): copper, brass, tin, lead and iron (Sanskrit); an alternative list of five metals: gold, silver, copper, tin (lead), and iron (dhātu; Nānārtharatnākara. 82; Mangarāja’s Nighaṇṭu. 498)(Kannada) kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali)

Such rebus readings are consistent with Robert K. Englund's summing up pointing to the possibility of non-Sumerian participants in the Bronze Age stoneware, metalware repertoire which constituted a veritable multi-national, industrial revolution of those times.

Tukulti Ninurta's altar with hieroglyphs happened in a domain where cuneiform was used -- say between Assur and Kanesh on Tin Road. Do the hieroglyphs on the altar mean Tukulti was illiterate? Tukulti altar displays on one side: safflower, rod on altar and on another side 2. spoked wheel. These are hieroglyphs related to bronze age alloys and fire-god karandi in Remo language (Munda family). The identification of Meluhha hieroglyphs proceeded from DT Potts' brilliant ingisht identifying tabernae montana wild tulip glyph on Tell Abraq axe, also on a vase and on a comb. TA 1649 Tell Abraq.(D.T. Potts, South and Central Asian elements at Tell Abraq (Emirate of Umm al-Qaiwain, United Arab Emirates), c. 2200 BC—CE 400. Potts' insight is complemented by the view of an archaeometallurgist who sees a link between the evolution of Bronze Age from a chalcolithic phase and the emergence of writing systems: “The Early Bronze Age of the 3rd millennium BCE saw the first development of a truly international age of metallurgy… The question is, of course, why all this took place in the 3rd millennium BCE… It seems to me that any attempt to explain why things suddenly took off about 3000 BCE has to explain the most important development, the birth of the art of writing… As for the concept of a Bronze Age one of the most significant events in the 3rd millennium was the development of true tin-bronze alongside an arsenical alloy of copper…” (J.D. Muhly, 1973, Copper and Tin, Conn.: Archon., Hamden; Transactions of Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 43, p. 221f. ) In this context, it is apposite to underscore the use of Meluhha hieroglyphs on two pure tin ingots which were discovered in a shipwreck at Haifa. (S. Kalyanaraman, 2010, The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” - Decoding Indus script as repertoire of the mints/smithy/mine-workers of Meluhha, Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Number 11, pp. 47-74).

Potts has explained further that nomadism was a remarkable phenomenon in ancient Iran. "Although evidence of 'proto-Median' agriculture and settled life may be difficult to find outside of Iran -- particularly as their 'homeland' remains vague and ill-defined -- linguistic studies suggest that some of the earliest Iranian speakers to reach the Iranian plateau did have an agricultural background and were familiar with both ploughing ad irrigation." Potts cites J. Puhvel, 'The Indo-European and Indo-Aryan plough: A linguistic study of technological diffusion,' Technology and Culture 5/2. 1964: 184-186, the posited Indo-Iraia verb stem *karś-meaning 'to plough', may have been a loanword.' (Potts 2014 - Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 75)

This hieroglyph is central to the entire corpora; it is the rosetta stone; it is a signifier tagaraka, wild fragrant tulip and the signified word is: tagara, TIN (cassiterite ore).

Massimo's arguments are convincing in the context of Wanderworter evidence from an extensive area deploying Meluhha hieroglyphs.

Massimo Vidale provided an effective rebuttal of the claim made by Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat & Michael Witzel that Harappan civilization was illiterate. (Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).

Excerpts: “My purpose is to reply to ‘The collapse of the Indus script thesis: the myth of a literate Harappan civilization’, by Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat & Michael Witzel, in Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS), 11, 2, 2004, pp. 19-57. I actually think that the Indus script was probably a protohistoric script, somehow conveying the sounds and words of one or more still unidentified languages. Although proofs are obviously lacking (the only demonstration would be a successful translation), this is the most reasonable assumption: and I must confess that I have lived so far rather content with such uncertainty…In order to decipher a lost writing system, you have to guess the language, guess the content, and you need relevant contexts on which independently and reasonably test your ideas…Farmer, Sproat & Witzel loudly stated that they have solved the mystery, that the Indus script is not writing, and that they can read or interpret part of the signs, I disagree with their arguments and, perhaps more, with the tone and language adopted by the authors…The authors would like to throw the ball to their opponents, asking them to refute their views by providing a sound decipherment in linguistic terms. But they have raised the problem, proposing a different interpretation and the first readings, and they have to provide a demonstration of their thesis by interpreting and explaining to us the symbolic sequences following the equivalent of their condition 4 (as stated at p. 48)…(but for the moment even Farmer & others will admit that their deities on vessels and seals and the solar cult advertised at Dholavira did not cost them such an impressive outburst of imagination).”

The epigraphs or artifacts so rendered as signifiers, as hieroglyphs are read rebus as Bronze Act metalware, stoneware repertoire. Cire perdue casting gets a name: dhokra (Meluhha) and the specialist artisans are calleddhokra kamar (Meluhha). Zinc is sattiya, jasta and the signifier is the svastika (sattiya). Pewter is tuthnag, the signifier includes a snake. Sharpness of alloyed metal derived from alloying is padm, the signifier is the snake-hood, paṭam.

The epigraphs or artifacts so rendered as signifiers, as hieroglyphs are read rebus as Bronze Act metalware, stoneware repertoire. Cire perdue casting gets a name: dhokra (Meluhha) and the specialist artisans are calleddhokra kamar (Meluhha). Zinc is sattiya, jasta and the signifier is the svastika (sattiya). Pewter is tuthnag, the signifier includes a snake. Sharpness of alloyed metal derived from alloying is padm, the signifier is the snake-hood, paṭam.

Meluhha artisans and traders operating along the Tin Road had carried with them the signifiers and signifieds and deployed them as epigraphs or artifacts to convey what they were specialists in. They had also produced 1. the flagposts found in Nahar Mishmar arsenical copper artifacts and 2. the leopard weights of Shahi Tump (Baluchistan).

Both the dreams are narrated in ancient texts and also on sculptures and epigraphs. The ancient texts describe the life-activities which the dreams signified. The hieroglyphs used on sculptures ad epigraphs provide for rebus representations of the dreams.

Rebus readings of the images (signifiers) yield the glosses related to life-activities (signifieds).

Both the dreams are presented in visible language of Meluhha using hieroglyphs, read rebus.

Dream of Tukulti-Ninurta and Māyā's dream are signified by visible language

"The dream is a rebus." (Freud, Sigmund, 1959, Interpretation of Dreams, p. 1).

One method of derivings meanings of the symbolism in dreams (or unconscious thought) is rebus.

Defining rebus as a picture-puzzle, Sigmund Frued elaborates the concept of displacement of emphasis and affect: "A correct judgment of the picture-puzzle results only if I make no such objections to the whole and its parts, but if, on the contrary, I take pains to replace each picture by the syllable or word which it is capable of representing by means of any sort of reference, the words which are thus brought together are no longer meaningless, but may constitute a most beautiful and sensible expression. Now the dream is a picture-puzzle of this sort, and our predecessors in the field of dream interpretation have made the mistake of judging the rebus as an artistic composition. As such it appears nonsensical and worthless." (Freud, Sigmund, 1913, Trans. by AA Brill, Interpretation of Dreams, Chapter VI, The dream-work, New York, The Macmillan Company http://www.bartleby.com/285/6.html)

The meanings of the visible images are signified by rebus readings of Meluhha language of Assur (Ancient Near East and Ancient India).

The signifier of Māyā's dream is an elephant. The word which signifies an elephant is ibha(Meluhha~Sanskrit). Rebus reading provides the signified: ib 'iron'. This is a condensation of the life activities of Māyā's clan, koliya, Koliya are koles, who are iron workers of yore from several generations. Her unconscious thought conditioned by the life of iron workers and smelters who were associated with her lineage identifies them by the product of their labour, ib 'iron'. The signifier for this life-activity of working in iron isibha, 'elephant'.

The inscription on the Tukulti Ninurta altar says: god Nusku.

The image is that of an ancestor of Tukulti Ninurta -- ancestor remembered in his dream?-- kneeling before the empty throne of the fire-god Nusku, occupied by what appears to be a flame.

Interpretation of the dream as rebus yields the meaning, the prayer is to fire-god Karandi. So, what is depicted is a flame while signifying the fire-god Karandi. In Meluhha language, the rebus reading of a clump of wood is करंडा [karaṇḍā].

Tukulti Ninurta's ancestor is an Assur, yes, the Assur whose lineage continues to be called Assur in some parts of India: Chattisgarh, Bastar, Santal paraganas, speaking an Asuri language (Meluhha dialect in the Munda language traditions of Indian sprachbund). This is good evidence that Assur of India had travelled far and wide into on the banks of Tigris river establishing the Tin Road between Assur and Kanesh (Kultepe, Anatolia). So, unconscious thought relates to the life-activities of the Assur people on this Tin Road trading in bronze-age artifacts. Hence, the presence of the following hieroglyphs on the Tukulti Ninurta altar: 1. करडी [karaḍī] f करडई) 'Safflower':, 2. nave of spoked wheel eraka, arā (nave, spokes) carried aloft on flagposts as trade announcements. Two flagposts are shown signifying dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast (metal)'.

The trade announcements are comparable to the flagposts shown on Mohenjo-daro tablets (which show hieroglyphs of spoked wheel, scarf, one-horned young bull, lathe-portable furnace -- eraka 'copper', dul 'cast (metal),arā 'brass', dhatu 'ore', konda 'turner's lathe', sangada 'citadel, guild'.)

Signifier is hieroglyph: safflower करडी [karaḍī].

Signified is rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. A color of horses, iron grey.

The signifier of Tukulti-Ninurta's dream is a fire-altar. The narrative of the dream is associated with the messages of the dream signifiers of the signifieds, signifiers of spoked wheels, safflowers signified as hard metal alloys of copper of the Bronze age. The word which signifies a fire-altar is kaṇḍa (Meluhha~Santali) The narrative is a prayer to fire-god. How to represent this prayer in a visible language detailing the life-activities which have imbued the images and related meanings into the unconscious mind? kāṇḍa is a stem or stick of the sugarcane; such a stem or stick is shown in visible language as the center-piece of the nuska-Ninurta fire altar image before which he kneels down and prays in adoration. He prays to karandi, the fire-god, the signified for which the visible language uses the signified: the stick. karandi 'fire-god' (Munda, Remo). Signifier: करंडा [karaṇḍā] A clump, chump, or block of wood. 4 The stock or fixed portion of the staff of the large leaf-covered summerhead or umbrella. करांडा [ karāṇḍā ] m C A cylindrical piece as sawn or chopped off the trunk or a bough of a tree; a clump, chump, or block. (Marathi)

The apparent, underlying assumption in the two rebus readings is that the language which provides the glosses is Meluhha and that Tukulti-Ninurta's fire-altar and sculptors who narrated Māyā's elephant are rebus representations of the life activities of Tukulti-Ninurta's clan of Assur and Māyā's clan of Koliyas.

Visible images in works of art are signifiers. Associated words of the spoken language become the signifieds. This is the rebus code.

"In the Assyro-Babylonian tradition, visual representation was considered to be part of an extreme semantic constellation. Like the ideogram in the script, the visual sign had the potential of referring to a chain of referents, linked to it and to one another by a logic that may escape the contemporary viewer but that could be deciphered in antiquity through hermeneutic readings. Such readings were obviously not accessible to a general public, most of whom were most likely nonliterate; however, the potential of signs referring to other signs in a continuous chain of meanings was a knowledge not limited to the literate. The ominous nature of things was a subject of concern fo all in Babylonian and Assyrian society. It seems clear from numerous texts that signs in the environment could be read and deciphered by people other than the scholarly elite or the priesthood. For omens related to the destiny of king or country, court diviners and the priesthood studied the signs, using their scholarly knowledge of astronomy and hermeneutics. But the reading of omina in the environment was also a part of the daily lives of people in general, as we know from textual references to egirru (omens of chance utterances) or to dreams and dream interpretation. Like other signs in the world, visual images could never be seen as the relationship between one signified and one signifier. An image was a pluridimensional sign that carried latent meanings beyond the one manifest on the surface. Since many works of art were made without any intent of presentation to mortal viewers, the polyvalence inherent in their imagery was not always a code intended for a particular audience, whether literate or nonliterate, although one can imagine that the system was at times deliberately manipulated for the purposes of generating a required meaing...polyvalence was considered to be in the very nature of the image-sign. The audience or intended viewer was not of the greatest import in many cases because the work of art was put a position where it was only to be viewed by the king, his courtiers, or temple officials. In these cases whatever meanings were generated through the imagery had much less to do with the good opinion of the chance viewer than they did with the power of the image as a eans of creating an incessant presence. In attempting to catalog ancient Near Eastern images by means of an iconography of one-to-one relationships of signifiers and signifieds, of symbols and gods, for example, we have perhaps limited our readings unnecessarily in a way that the Babylonians and Assyrians would not have done." (Zainab Bahrani, 2011, The graven image: representation in Babylonia and Assyria, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, p. 185-186).

Sigmund Freud refers to a syntax of dreams noting that the pictorial language of the dream uses what Freud explains as 'condensation and displacement' (Freud 1959).

Dream depicted on Tukulti-Ninurta altar

'I have revealed to Atrahasis a dream, and it is thus that he has learned the secret of the gods.' (Epic of Gilgamesh, Ninevite version, XI, 187.)

The Pedestal of Tukulti-Ninurta I

![]() Artifact: Stone monumentProvenience: Assur

Artifact: Stone monumentProvenience: Assur

Period: Middle Assyrian period (ca. 1400-1000 BC)

Current location: Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

Text genre, language: Royal inscription; Akkadian

Description: Although the cult pedestal of the Middle Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta mentions in its short inscription that it is dedicated to the god Nuska, the relief on the front that depicts the king in a rare kind of narrative, standing and kneeling in front of the very same pedestal was frequently discussed by art-historians. More strikingly on top of the depicted pedestal there is not the lamp, the usual divine symbol for the god Nuska, but most likely the representation of a tablet and a stylus, symbols for the god Nabû. (Klaus Wagensonner, University of Oxford) Editions: Grayson, A.K. 1987. The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Period, I: Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia B.C. (to 1115 B.C.), Toronto, p. 279ff.An inscription of Gudea of Lagash (2143-2124 BCE) narrates that he had a dream. He describes the dream to goddess Nina: "In the dream a man, whose stature reached up to heaven (and) reached down to earth, who according to the tiara around his head was a god...at whose feet was a storm, to whose right and left a lion ws at rest, commanded me to built his house (i.e., temple)...a second (man), like a warrior...held in his hand a tablet of lapus-lazuli, (and) outlined the pattern of a temple." (Thureau-Dangin, Die Sumerischen und Akkadischen Konigsinschriften, 94-95 Cylinder A, 4, 14--5,4).

A similar dream is explained on the Tukulti-Ninurta altar. The kneeling adorant prays in front of the altar. The visible image of this prayer is presented on one of the altar. The image on the altar is a rebus.

Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244-1208 BCE) of Assur, narrates the dreams which led to his conquests of Babylon in his epic, a lengthy poem of about 750 to 800 lines. (Lambert, WG, 1957, Three unpublished fragments of the Tukulti-Ninurta Epic, Archiv fur Orientforschung 18, Bd, 1957-1958, pp. 38-51).

Narratives from the dream are visible on the hieroglyphs presented on the altar.

Dream of Māyā, mother of Gautama Buddha details ancient texts and sculptural representations providing signifiers of the dream: in particular, the descent of an elephant which is a hieroglyph read rebus, consistent with the dream as a rebus. The narrative is accompanied by Meluhha hieroglyphs which include a scribe of the guild of metal-/stone-work artisans who might have been involved in the construction of the monuments in Bharhut and Nagarjunakonda -- commemorative pilgrimages of Bauddham. Māyā's dream is a sacred, hallowed tradition in Bauddham and the narrative is revered in ancient sculptures and ancient texts. This tradition is further elaborated by the use of Meluhha hieroglyphs which are read rebus, validating the Meluhha hieroglyph cipher for the ancient, unambiguous vernacular of Indian sprachbund.

Detail of the top of the sandstone Vedica pillar, half-roundel at top of vedika pillar with composite creatures in relief:

The top register o this relief shows ligatured antelopes back-to-back; the next register from the top shows a bull ligatured to a makara (crocodile with curved fish tail).

![half-roundel at top of vedika pillar with composite creatures in relief]()

Detail of the roundel:

![vedika roundel with image of Maya's Dream in relief]()

![]()

Segments of the sculpture showing: 1. scribe; 2. stacks of straw asociated with epigraphs (incribed ovals -- cartouches -- atop the stacks) and the row of seated artisans. There are two hieroglyphs on these segments: 1. scribe; 2. straw-stacks. Both can be read as Meluhha hieroglyphs.

The scribe shown on Nagarjunakonda sculpture is kaṇḍa kanka 'stone scribe'.

The gloss is reinforced by the hieroglyph: stack of straw: kaṇḍa (See Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund appended).

Māyā is a Koliya, i.e. she is a kole, a community working in iron. kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil).

Koles are the outstanding smelters of iron.

There is an article by Suniti Kumar Chatterjee explaining that the word 'kol' meant 'man' in general.

An old Munda word, kol means ‘man’. S. K. Chatterjee called the Munda family of languages as Kol, as the word, according to him, is (in the Sanskrit-Prākṛt form Kolia) an early Aryan modification of an old Munda word meaning ‘man’.[i] Przyluski accepts this explanation.[ii]

[i] Chatterjee, SK, The study of kol, Calcutta Review, 1923, p. 455[ii] Przyluski, Non-aryan loans in Indo-Aryan, in: Bagchi, PC, Pre-aryan and pre-dravidian, pp.28-29

The crocodile ligatured to the bull is: kāru ‘crocodile’ Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) ayakara'fish+crocodile' rebus: 'metal-smith'. adar 'zebu' rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal or ore' (Kannada) aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). aduru =gaṇiyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace.[i]

[i] Kannada. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore,Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330.

Note: In this remarkable ligature, the crocodile+fish hieroglyphs are NOT ligatured to the trunk of an elephant because the scribe wants to precisely communicate the nature of the profession of the artisan guild involved with the prayer to the Buddha narrating his birth. If the elephant was intended, the rebus readings would have included: ibha 'elephant' (Samskrtam) ibbo 'merchant' (Hemacandra Desināmamāla -Gujarati) ib 'iron' (Santali).

Vikalpa: the bull is: ḍangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi).

The two antelopes joined back-to-back: pusht ‘back’; rebus: pusht ‘ancestor’. pus̱ẖt bah pus̱ẖt ‘generation to generation.’ The ram could also be denoted by ṭagara ‘antelope’; takar, n. [தகர் T. tagaru, K. tagar.] 1. Sheep; ஆட்டின்பொது. (திவா.) 2. Ram; செம் மறியாட்டுக்கடா. (திவா.) பொருநகர் தாக்கற்குப் பேருந் தகைத்து (குறள், 486). Rebus: ṭagara ‘tin’. dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul 'cast metal’ (Munda). Thus the pair of antelopes on the top register denotes: tin smith artisan, dul ṭagara 'cast tin'.

The associated hieroglyphs, in the context of depicting the narratives of Māyā's dream, in particular (and their rebus readings) which are elaborated further in this monograph pointing to a continuum of writing systems from the days of Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus writing) are:

- stack of straw

- scribe

- bull ligatured to makara (crocodile + fish tail)

- antelopes ligatured back-to-back

Māyā had a dream in which she saw an elephant (ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'). King Śuddhodana and his soothsayers interpreted the dream that she would bear a son who with detached passion would satisfy the world with sweetness of his ambrosia.

Artifact: Stone monument

Provenience: Assur

Period: Middle Assyrian period (ca. 1400-1000 BC)

Current location: Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

Text genre, language: Royal inscription; Akkadian

Description: Although the cult pedestal of the Middle Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta mentions in its short inscription that it is dedicated to the god Nuska, the relief on the front that depicts the king in a rare kind of narrative, standing and kneeling in front of the very same pedestal was frequently discussed by art-historians. More strikingly on top of the depicted pedestal there is not the lamp, the usual divine symbol for the god Nuska, but most likely the representation of a tablet and a stylus, symbols for the god Nabû. (Klaus Wagensonner, University of Oxford) Editions: Grayson, A.K. 1987. The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Period, I: Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia B.C. (to 1115 B.C.), Toronto, p. 279ff.

An inscription of Gudea of Lagash (2143-2124 BCE) narrates that he had a dream. He describes the dream to goddess Nina: "In the dream a man, whose stature reached up to heaven (and) reached down to earth, who according to the tiara around his head was a god...at whose feet was a storm, to whose right and left a lion ws at rest, commanded me to built his house (i.e., temple)...a second (man), like a warrior...held in his hand a tablet of lapus-lazuli, (and) outlined the pattern of a temple." (Thureau-Dangin, Die Sumerischen und Akkadischen Konigsinschriften, 94-95 Cylinder A, 4, 14--5,4).

A similar dream is explained on the Tukulti-Ninurta altar. The kneeling adorant prays in front of the altar. The visible image of this prayer is presented on one of the altar. The image on the altar is a rebus.

Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244-1208 BCE) of Assur, narrates the dreams which led to his conquests of Babylon in his epic, a lengthy poem of about 750 to 800 lines. (Lambert, WG, 1957, Three unpublished fragments of the Tukulti-Ninurta Epic, Archiv fur Orientforschung 18, Bd, 1957-1958, pp. 38-51).

Narratives from the dream are visible on the hieroglyphs presented on the altar.

Dream of Māyā, mother of Gautama Buddha details ancient texts and sculptural representations providing signifiers of the dream: in particular, the descent of an elephant which is a hieroglyph read rebus, consistent with the dream as a rebus. The narrative is accompanied by Meluhha hieroglyphs which include a scribe of the guild of metal-/stone-work artisans who might have been involved in the construction of the monuments in Bharhut and Nagarjunakonda -- commemorative pilgrimages of Bauddham. Māyā's dream is a sacred, hallowed tradition in Bauddham and the narrative is revered in ancient sculptures and ancient texts. This tradition is further elaborated by the use of Meluhha hieroglyphs which are read rebus, validating the Meluhha hieroglyph cipher for the ancient, unambiguous vernacular of Indian sprachbund.

Detail of the top of the sandstone Vedica pillar, half-roundel at top of vedika pillar with composite creatures in relief:

The top register o this relief shows ligatured antelopes back-to-back; the next register from the top shows a bull ligatured to a makara (crocodile with curved fish tail).

![half-roundel at top of vedika pillar with composite creatures in relief]()

Detail of the roundel:

![vedika roundel with image of Maya's Dream in relief]()

Detail of the roundel:

Segments of the sculpture showing: 1. scribe; 2. stacks of straw asociated with epigraphs (incribed ovals -- cartouches -- atop the stacks) and the row of seated artisans. There are two hieroglyphs on these segments: 1. scribe; 2. straw-stacks. Both can be read as Meluhha hieroglyphs.

The scribe shown on Nagarjunakonda sculpture is kaṇḍa kanka 'stone scribe'.

The gloss is reinforced by the hieroglyph: stack of straw: kaṇḍa (See Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund appended).

Māyā is a Koliya, i.e. she is a kole, a community working in iron. kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil).

Koles are the outstanding smelters of iron.

There is an article by Suniti Kumar Chatterjee explaining that the word 'kol' meant 'man' in general.

An old Munda word, kol means ‘man’. S. K. Chatterjee called the Munda family of languages as Kol, as the word, according to him, is (in the Sanskrit-Prākṛt form Kolia) an early Aryan modification of an old Munda word meaning ‘man’.[i] Przyluski accepts this explanation.[ii]

[i] Chatterjee, SK, The study of kol, Calcutta Review, 1923, p. 455

[ii] Przyluski, Non-aryan loans in Indo-Aryan, in: Bagchi, PC, Pre-aryan and pre-dravidian, pp.28-29

The crocodile ligatured to the bull is: kāru ‘crocodile’ Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) ayakara'fish+crocodile' rebus: 'metal-smith'. adar 'zebu' rebus: aduru 'unsmelted metal or ore' (Kannada) aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). aduru =gaṇiyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace.[i]

[i] Kannada. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore,Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330.

Note: In this remarkable ligature, the crocodile+fish hieroglyphs are NOT ligatured to the trunk of an elephant because the scribe wants to precisely communicate the nature of the profession of the artisan guild involved with the prayer to the Buddha narrating his birth. If the elephant was intended, the rebus readings would have included: ibha 'elephant' (Samskrtam) ibbo 'merchant' (Hemacandra Desināmamāla -Gujarati) ib 'iron' (Santali).

Note: In this remarkable ligature, the crocodile+fish hieroglyphs are NOT ligatured to the trunk of an elephant because the scribe wants to precisely communicate the nature of the profession of the artisan guild involved with the prayer to the Buddha narrating his birth. If the elephant was intended, the rebus readings would have included: ibha 'elephant' (Samskrtam) ibbo 'merchant' (Hemacandra Desināmamāla -Gujarati) ib 'iron' (Santali).

Vikalpa: the bull is: ḍangar 'bull' Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi).

The two antelopes joined back-to-back: pusht ‘back’; rebus: pusht ‘ancestor’. pus̱ẖt bah pus̱ẖt ‘generation to generation.’ The ram could also be denoted by ṭagara ‘antelope’; takar, n. [தகர் T. tagaru, K. tagar.] 1. Sheep; ஆட்டின்பொது. (திவா.) 2. Ram; செம் மறியாட்டுக்கடா. (திவா.) பொருநகர் தாக்கற்குப் பேருந் தகைத்து (குறள், 486). Rebus: ṭagara ‘tin’. dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul 'cast metal’ (Munda). Thus the pair of antelopes on the top register denotes: tin smith artisan, dul ṭagara 'cast tin'.

The associated hieroglyphs, in the context of depicting the narratives of Māyā's dream, in particular (and their rebus readings) which are elaborated further in this monograph pointing to a continuum of writing systems from the days of Meluhha hieroglyphs (aka Indus writing) are:

- stack of straw

- scribe

- bull ligatured to makara (crocodile + fish tail)

- antelopes ligatured back-to-back

Takṣat vāk, ‘incised speech’ -- Evidence of Indus writing of Meluhha language in Ancient Near East

Procession on Narmer palette. An artistic deployment of Egyptian hieroglyphs on a procession is seen on one side of Narmer palette. The name Nar-mer is shown as rebus reading of n’r ‘cuttle-fish’ + m’r ‘awl’. Both these hieroglyphs are depicted in front of the Emperor Narmer who follows the procession.

Similar is the logo-semantic cipher method used on Indus writing, to write ayakara ‘metalsmith’.

Glosses of Indian sprachbund used on Indus writing to encode speech:

ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) aya = iron (Gujarati);

ayah, ayas = metal (Sanskrit.)

kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) ghariyal id. (Hindi)

khār a blacksmith, an iron worker (Kashmiri)

ayakāra ‘iron-smith’ (Pali)

Proto-phonetic forms of these lexemes which constitute the substrates of Meluhha (Mleccha) language and are likely to yield the glosses of Meluhha (Mleccha) speech of 3rd millennium BCE. Aya ‘fish’ + karā ‘crocodile, ghariyal’ as hieroglyphs are depicted to be read rebus as aya ‘metal’ + khara ‘smith’ (in mlecccha/meluhha language). The sounds of words of mleccha/meluhha language are the speech foundations of the Indus writing system. Many inscriptions of Indus writing are read as metalware catalogs – like this ayakara ‘metalsmith’ catalog item shown on one side of a Mohenjo-daro prism tablet (Corpora reference: m1429C).

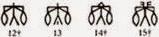

Another example may be cited of a Seal impression, Ur (UPenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6, ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5; Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the head (denoting supernatural?). “The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. Theparenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse. An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal.” (Hunter, G.R.,JRAS, 1932, 476). This ‘water-carrier’ hieroglyph is normalized as a ‘sign’ (Glyph 12) on Indus Writing corpora. The seal impression is read rebus as composed of three hieroglyphs:

[i] Verma, TP, Writing in the Vedic Age, Harappan and As’okan Writing, in: Itihas Darpan XVIII (1), 2013 Research Journal of Akhila Bhāratiya Itihāsa Sankalana Yojanā, New Delhi, pp. 40-59.http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/writing-in-vedic-age-prof-tp-verma.html Writing in Vedic Age by Prof. TP Verma. Three frustrated scholars' dogma on illiteracy.

Another example may be cited of a Seal impression, Ur (UPenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6, ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5; Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the head (denoting supernatural?). “The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. Theparenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse. An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal.” (Hunter, G.R.,JRAS, 1932, 476). This ‘water-carrier’ hieroglyph is normalized as a ‘sign’ (Glyph 12) on Indus Writing corpora. The seal impression is read rebus as composed of three hieroglyphs:

[i] Verma, TP, Writing in the Vedic Age, Harappan and As’okan Writing, in: Itihas Darpan XVIII (1), 2013 Research Journal of Akhila Bhāratiya Itihāsa Sankalana Yojanā, New Delhi, pp. 40-59.http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/writing-in-vedic-age-prof-tp-verma.html Writing in Vedic Age by Prof. TP Verma. Three frustrated scholars' dogma on illiteracy.

[ii] Sproat, Richard, 2013, ‘Written language vs. non-linguistic symbol systems’ mirrored in a blogpost:http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/written-language-vs-non-linguistic.html

[iii] Rao, Rajesh, 2010. Probabilistic analysis of an ancient undeciphered script. IEEE Computer. 43~(3), 76–80. Rajesh PN Rao, Nisha Yadav, Mayank N. Vahia, Hrishikesh Joglekar, R. Adhikari and Iravatham Mahadevan, A Markov model of the Indus Script, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,, Vol. 106 no. 33, 13685-13690.

A reconstructed drawing of 'standard device' generally shown in front of a one-horned young bull and also on a procession of hieroglyphs or on a gold pectoral or of ivory in the round.Mohenjo-daro pectoral m1656. The pectoral shows hieroglyphs: rim of jar, jar, overflowing (liquid), one-horned young bull, pannier on bull's shoulder, standard device in front composed of: gimlet, portable furnace as top part of the device and sometimes dotted circles are shown on the bottom part of the device. All glyphics read rebus denote the pectoral owners calling or profession. In this case, a smith working with furnace (smelting copper) workshop.

Rebus readings:

Hieroglyphs young bull, rings on neck, pannier: gōta ‘sack’.kŏthul, lu m. ʻlarge bag or parcelʼ(Kashmiri) (CDIAL 3511)kṓṣṭha1 m. ʻ any one of the large viscera ʼ MBh. [Same as kṓṣṭha -- 2? Cf. *kōttha -- ] Pa. koṭṭha -- m. ʻ stomach ʼ, Pk. koṭṭha -- , kuṭ° m.; L. (Shahpur) koṭhī f. ʻ heart, breast ʼ; P. koṭṭhā, koṭhā m. ʻ belly ʼ, G. koṭhɔ m., M. koṭhā m. (CDIAL 3545).koḍiyum ‘rings on neck’. kāru-kōḍe. [Tel.] n. A bull in its prime. खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) గోద [ gōda ] gōda. [Tel.] n. An ox. A beast. kine, cattle.(Telugu) Rebus : B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or. kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ‘lathe’) (CDIAL 3295). koḍ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi.G.)Rebus: S. koṭāru m. ʻ district officer who watches crops, police officer ʼ (CDIAL 3501). Cf. kṓṣṭhaka ‘treasury’ (Skt.); kóṭṭhi ’temple treasury’ (WPah.); koṭho ‘warehouse’ (G.)(CDIAL 3546). Rebus: khoṭa ʻingot forged, alloyʼ(Marathi)Allograph: kōṭu summit of a hill(Tamil). Rebus: khoṭf. ʻalloy, impurityʼ, °ṭā ʻalloyed’.