Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/zat4ty2

Kudos to Archaeology team of Deccan College, Pune for unraveling the largest settlement of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization at Rakhigarhi spread over 224 hectares

Copper mirror, Rakhigarhi

Copper object, Rakhigarhi

I deem it a privilege to report on an overview report on Rakhigarhi excavations by Dr. Vasant Shinde in an article titled, 'Harappan civilization: current perspective and its contribution'.

The article appeared on Feb. 1, 2016 on sindhology.org website. I reproduce the article in full because of its importance discussing the finds from Rakhigarhi which is now the largest site of the Sarasvati-Sindhu (Indus Valley) Civilization, spread over 224 hectares.

The work of Shinde's Pune Deccan College young archaeologists' team is brilliant, by any archaeological standards, carried out in a space which merges with the present-day villages with occupied areas in a densely populated region of Hissar Dist., Haryana, near Delhi, restricting the areas allowed for digging and exploratio without upsetting the lives of the living.

The challenge to unravel the civilization of ca. 3500 BCE surrounded by people living in the area in houses which have been contructed over the ancient settlement structures is extraordinary and all credit goes to the Pune Deccan College team of young archaeologists, led by Shinde.

Indus Script inscriptions discovered in Rakhigarhi

RG1 Seal remnant. (See decipherment given below)RG2 Potsherd karNaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus supercargo of cast metal workshop. dhAu 'strands' rebus: dhAu 'element, minerals' kamaTha 'bow and arrow' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.One-horned young bull. RG3. Seal and Seal impression. Mound 4Seal. RG4 3cm.square. dhAu 'strand' rebus: dhAu 'element, mineral' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' Thus minerals smithy/forge. For decipherment of hieroglyph-multiplex of one-horned young bull PLUS standard device, see decipherment given below.Seal fragment RG6 kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' Thus, bronze workshop PLUS ayo khambhaṛā 'fish-fin', ayas 'metal' PLUS kammaTa 'mint'

Copper mirror, Rakhigarhi

Copper object, Rakhigarhi

![]() RG5 Rakhigarhi seal.

RG5 Rakhigarhi seal.

Decipherment of Seal RG5 Rakhigarhi. Note: The splitting of the ellipse 'ingot' into Right and Left parethesis and flipping the left parenthesis (as a mirror image) may be an intention to denote cire perdue casting method used to produce the metal swords and implements. The entire inscription or metalwork catalogue message on Rakhigarhi seal can be deciphered:

This circumgraph of right-curving and left-curving parentheses encloses an 'arrow' hieroglyph PLUS a 'notch'. khāṇḍā A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. Thus the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies: ingot for implements.

kaNDa 'implements/weapons' (Rhinoceros) PLUS खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'weapons' PLUS mūhā 'cast ingots'(Left and Right parentheses as split rhombus or ellipse).

Thus, the supercargo consignment documented by this metalwork catalogue on Rakhigarhi seal is: metal (alloy) swords, metal (alloy) implements, metal cast ingots.

Hieroglyph: gaṇḍá4 m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ lex., °aka -- m. lex. 2. *ga- yaṇḍa -- . [Prob. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá -- 1 : cf. gaṇōtsāha -- m. lex. as a Sanskritized form ← Mu. PMWS 138]1. Pa. gaṇḍaka -- m., Pk. gaṁḍaya -- m., A. gãr, Or. gaṇḍā.2. K. gö̃ḍ m.,S. geṇḍo m. (lw. with g -- ), P. gaĩḍā m., °ḍī f., N. gaĩṛo, H. gaĩṛā m., G. gẽḍɔ m., °ḍī f., M. gẽḍā m.Addenda: gaṇḍa -- 4 . 2. *gayaṇḍa -- : WPah.kṭg. ge ṇḍɔ mi rg m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ, Md. genḍā ← (CDIAL 4000) காண்டாமிருகம் kāṇṭā-mirukam , n. [M. kāṇṭāmṛgam.] Rhinoceros;

கல்யானை. খাঁড়া (p. 0277) [ khān̐ḍ়ā ] n a large falchion used in immolat ing beasts; a large falchion; a scimitar; the horny appendage on the nose of the rhinoceros.গণ্ডক (p. 0293) [ gaṇḍaka ] n the rhinoceros; an obstacle; a unit of counting in fours; a river of that name.গন্ডার (p. 0296) [ ganḍāra ] n the rhinoceros.(Bengali. Samsad-Bengali-English Dictionary) गेंडा [ gēṇḍā ] m (

An alternative hieroglyph is a rhombus or ellipse (created by merging the two forms: parnthesis PLUS fipped parenthesis) to signify an 'ingot': mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end (Munda).

This circumgraph of right-curving and left-curving parentheses encloses an 'arrow' hieroglyph PLUS a 'notch'.

Hieroglyph: kANDa 'arrow' Rebus: kaṇḍ '

This gloss is consistent with the Santali glosses including the word khanDa:

Here is a decipherment using the rebus-metonymy layered Indus Scipt cipher in Meluhha language of Indian sprachbund (language union):

kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Telugu)

कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi)

Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that

of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

I suggest that the language spoken by the Sarasvati's children was Meluhha

(Mleccha), a spoken, vernacular version of Vedic chandas. This may also be

called Proto-Prakritam, not unlike Ardhamaadhi identified by Jules Bloch in

his work: Formation of Marathi Language.

A three-centimetre seal with the Harappan script. It has no engraving of any animal motif.

See:

Hieroglyph: sãgaḍ, 'lathe' (Meluhha) Rebus 1: sãgaṛh , 'fortification' (Meluhha). Rebus 2:sanghAta 'adamantine glue'. Rebus 3:

sangāṭh संगाठ् 'assembly, collection'. Rebus 4: sãgaḍa 'double-canoe, catamaran'.

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull: खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf.

Rebus: कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving.

ko_d.iya, ko_d.e = young bull; ko_d.elu = plump young bull; ko_d.e = a. male as in: ko_d.e du_d.a = bull calf; young, youthful (Te.lex.)

Hieroglyph: ko_t.u = horns (Ta.) ko_r (obl. ko_t-, pl. ko_hk) horn of cattle or wild animals (Go.); ko_r (pl. ko_hk), ko_r.u (pl. ko_hku) horn (Go.); kogoo a horn (Go.); ko_ju (pl. ko_ska) horn, antler (Kui)(DEDR 2200). Homonyms: kohk (Go.), gopka_ = branches (Kui), kob = branch (Ko.) gorka, gohka spear (Go.) gorka (Go)(DEDR 2126).

खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. 2

kot.iyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; kot. = neck (G.lex.) [cf. the orthography of rings on the neck of one-horned young bull].खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ]A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडरूं (p. 216) [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl.खोंडा (p. 216) [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. 2 fig. A hollow amidst hills; a deep or a dark and retiring spot; a dell. 3 (also खोंडी & खोंडें ) A variety of जोंधळा .खोंडी (p. 216) [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

kod. = place where artisans work (G.lex.) kod. = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.lex.) gor.a = a cow-shed; a cattleshed; gor.a orak = byre (Santali.lex.) कोंड (p. 180) [ kōṇḍa ] A circular hedge or field-fence. 2 A circle described around a person under adjuration. 3 The circle at marbles. 4 A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste.कोंडडाव (p. 180) [ kōṇḍaḍāva ] m Ring taw; that form of marble-playing in which lines are drawn and divisions made:--as disting. from अगळडाव The play with holes.कोंडवाड (p. 180) [ kōṇḍavāḍa ] n f C (कोंडणें & वाडा ) A pen or fold for cattle.कोंडाळें (p. 180) [ kōṇḍāḷēṃ ] n (कुंडली S) A ring or circularly inclosed space. 2 fig. A circle made by persons sitting round.

kuṭire bica duljad.ko talkena, they were feeding the furnace with ore. In this Santali sentence bica denotes the hematite ore. For example, samṛobica, 'stones containing gold' (Mundari) meṛed-bica 'iron stone-ore' ; bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda). mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’(Munda. Ho.)

Meluhha rebus representations are: bica ‘scorpion’ bica ‘stone ore’ (hematite).

pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite). kuṇṭha munda (loha) a type of hard native metal, ferrous oxide.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/09/catalogs-of-pola-kuntha-gota-bichi.html#! Hieroglyph: pōḷī, ‘dewlap' पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large (Marathi) Rebus: pola (magnetite)

ḍaṅgra 'bull' Rebus: ḍāṅgar, ḍhaṅgar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi).

. See:http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.html Magnetite a type of iron ore is called POLA by the Asur (Meluhha).

Hieroglyph strings from l. to r.:Top line inscription on stone:कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: karNika 'helmsman, supercargo' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) koD 'one' rebus: koD 'workshop' Thus, iron workshop supercargo. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implements' kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' . Thus, bronze implements. barDo 'spine' rebus: bharata 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin' PLUS karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNi 'supercargo'. Bottom line inscription on stone: kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' PLUS eraka 'nave of wheel' PLUS arA 'spoke' rebus: Ara 'brass' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNIka 'helmsman' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' PLUS tuttha 'goat' rebus: tuttha 'zinc sulphate.

Hieroglyph strings from l. to r.:Top line inscription on stone:कर्णक 'spread legs' rebus: karNika 'helmsman, supercargo' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) koD 'one' rebus: koD 'workshop' Thus, iron workshop supercargo. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implements' kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' . Thus, bronze implements. barDo 'spine' rebus: bharata 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin' PLUS karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNi 'supercargo'. Bottom line inscription on stone: kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze' PLUS eraka 'nave of wheel' PLUS arA 'spoke' rebus: Ara 'brass' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNIka 'helmsman' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' PLUS tuttha 'goat' rebus: tuttha 'zinc sulphate.Reading the Indus writing inscriptions on both sides of bun-shaped lead ingots of Rakhigarhi

The Indus writing inscriptions relate to cataloging of metalwork as elaborated by the following rebus-metonymy cipher and readings in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund):

meD 'body' kATi 'body stature' Rebus: meD 'iron' kATi 'fireplace trench'. Thus, iron smelter.

koDa 'one' Rebus: koD 'workshop'

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: baTa 'furance'

kanka, karNika 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNi 'supercargo'; karNika 'account'.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; meD 'body' kATi 'body stature' Rebus: meD 'iron' kATi 'fireplace trench'. Thus, iron smelter.

A spoked wheel is ligatured within a rhombus: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast'

See many variants of 'body' hieroglyph and ligatures at

Figure 14: Side (A) and top (B) views of a lead ingot inscribed with Harappan characters. Detailed images of the top (C) and bottom (D) inscriptions.

Rakhigarhi finds including a broken seal (one-horned young bull).

Rakhi Garhi (Archeological Mound)

![]() Rakhigarhi is about to rewrite the 5000 year old history of our civilization. Recent excavations at Rakhi Garhi in Hissar district of Haryana may push the history of the civilization back by over a thousand years. It could change the commonly held view about the Indus Valley civilization, as Rakhigarhi is situated on the bank of the now dry, Saraswati river. Archaeologists and historians are excited about the findings from Rakhigarhi, the largest Indus Valley site after Mohenjodaro. Senior archaeologists consider this to be no ordinary Harappan site and say it is the most important of all the archaeological sites of India. The unearthed clues may yield answers to questions that have remained unanswered so far. Rakhigarhi findings have already started showing new civilization contours.

Rakhigarhi is about to rewrite the 5000 year old history of our civilization. Recent excavations at Rakhi Garhi in Hissar district of Haryana may push the history of the civilization back by over a thousand years. It could change the commonly held view about the Indus Valley civilization, as Rakhigarhi is situated on the bank of the now dry, Saraswati river. Archaeologists and historians are excited about the findings from Rakhigarhi, the largest Indus Valley site after Mohenjodaro. Senior archaeologists consider this to be no ordinary Harappan site and say it is the most important of all the archaeological sites of India. The unearthed clues may yield answers to questions that have remained unanswered so far. Rakhigarhi findings have already started showing new civilization contours.

The area and dimensions of the site are far wider than assessed by archaeologist Raymond and Bridget Allchin and J M Kenoyer. It is 224 hectares, the largest in the country. In size, dimensions strategic location and unique significance of the settlement, Rakhi Garhi matches Harappa and Mohenjodaro at every level. Three layers of Early, Mature and Late phases of Indus Valley civilization have been found at Rakhi Garhi. What has so far been found uncannily indicates that Rakhi Garhi settlement witnessed all the three phases.

The site has trick deposits of Hakra Ware (typical of settlements dating back before the early phases of Indus Valley). Early and Mature Harappan artifacts. The solid presence of the Hakra Ware culture raises the important question: "Did the Indus civilization come later than it is recorded?" The Hakra and the Early phases are separated by more than 500-600 years and the Hakra people are considered to be the earliest Indus inhabitants. Although the carbon-14 dating results are awaited, based on the thick layers of Hakra Ware at Rakhi Garhi, it is said that the site may date back to about 2500 BC to 3000 BC. This pushes the Indus Valley civilization history by a thousand years or more.![The lost city of Rakhigarhi Rakhigarhi, largest harappan site:]()

Rakhigarhi: Discovering India’s biggest Harappan site

GoUNESCO December 4, 2015

GoUNESCO December 4, 2015

Built, Featured, Heritage

The Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most enigmatic events in human history. It was truly a paean to the desire for human excellence, even in those times, bringing in its wake several important inventions which mankind has derived progress from.

The Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most enigmatic events in human history. It was truly a paean to the desire for human excellence, even in those times, bringing in its wake several important inventions which mankind has derived progress from.

But in 1963 when the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) discovered Rakhigarhi, a village in Hisar District in the state of Haryana, they realized what they had found was a site, more ancient and much larger than Harappa and Mohenjo-daro sites. Dr. Shinde, 59, the vice chancellor of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, a deemed university in Pune, is heading the excavation in Rakhigarhi, and is in pursuit of genetic material.

In April 2015, four complete human skeletons were excavated at Rakhigarhi. These skeletons belonged to two male adults, one female adult and one child. As the skeletons were excavated scientifically without any contamination, Dr. Shinde and his team believe that with the help of latest technology, the DNA of these skeletons can help determine how Harappans looked like 4500 years ago. He tells us more in this interview:

Rakhigarhi has the potential to open doorways to Harappan culture with the latest discovery earlier this year, any progress on this aspect so far?

With Rakhigarhi coming into the picture, Harappan culture covers the largest area compared to the others that existed around this time period. We have successfully detected DNAs and teams from India and South Korea are working on developing it further. The conclusion of this study would tell us what a Harappan man looked like: His origin, relationship with the contemporary man, whether they were indigenous or if they came from outside (descendent of some other civilization).All the remains that were excavated before this were from 4000BC or after. This has been a major breakthrough in the biggest civilization that ever existed. It traces this civilization to as early as 5500 BC. There are three stages of any civilization: Formative, Developed and Decline stage. So far only the developed stages were studied, but in this case, we are also developing new aspects of study, we are exploring the alpha: The Formative Stage – How the civilization came into being, development or changes in culture, DNA etc.

Rakhigarhi: Discovering India’s biggest Harappan site2015-12-24T11:23:12+00:00

How could the site be promoted, to ensure that the research is financially sustained?We have been receiving financial support from ASI, but with such a large scale project, it is not enough to carry out the research on such a shoestring budget. This place is of high historic significance, we are building museums at Rakhigarhi where the artifacts recovered from here can be stored and viewed by general public. It is a major breakthrough into the world history, and once people begin to understand that, the funds will flow in naturally. We are trying to spread awareness about the monumentality of this discovery. It has been proposed to be added among the likes of other civilizations that exist in the UNESCO list today.

With such a large number of ancient cities being discovered in the past decade, where can we trace the origin of Harappan culture from?

India, and specifically Maharashtra, Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, parts of Rajasthan and also a large part of Pakistan. It is the biggest civilization that ever existed and it gradually aggrandized to other areas. There are traces of this culture in Mesopotamia but it can be safely concluded that it was only on a trade basis, there is no direct supplement of this culture that associates it with likes of others.

With Rakhigarhi being nominated to be listed among the other heritage sites in UNESCO list, it is very likely to attract a lot of tourism. Is it a wise idea to open it to public without the risk of contaminating this work in progress?

On the contrary, we are looking forward to it. The on-site research takes place for only 3 months in a year. There are separate areas of sensitive excavation which will be closed to general public. Although, it will be a good idea if we let others open and the tourists witness the work in progress and observe how the work is carried out. Rakhigarhi is listed as one of the 10 most endangered heritage sites in the world, what are the threats that this site faces today? Earlier, there had been instances of looting and selling of precious artifact, parts of the sites were encroached by private houses; we tried our best to safeguard these evidences. But now, as the local authorities are beginning to understand the significance of their soil, we are receiving a lot of local support and helping hands in our project. We are talking about cities that were constructed over 4000 years ago, hypothetically do you think present day cities have any chance of surviving and being studied about 4000 years later? When our ruins are discovered, will it be of any value at all or what can we do to make it valuable? Well, we have a lot to learn from these civilizations first, Harappan civilization is the most advanced civilization to have been discovered. It has contributed immensely to present day science and technology and are the foundation stone of today’s architectural (city planning), civil engineering, agricultural (crop rotation, double cropping, water harvesting) scenario. And while we learn about them, we forget to apply those values in our lives today. So, it is very likely, that when our ruins are discovered, we may not contribute to the development in that age but just remain as a link from the past. For more pictures of the excavation site, click here. As told to: Vedika Singhania http://www.gounesco.com/rakhigarhi-discovering-indias-biggest-harappan-site/

Move Over Mohenjo-Daro, India Now Has the Biggest Harappan Site In Rakhigarhi

The discovery of two more mounds at the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana makes it the biggest excavation site of Harappan civilisation, even bigger than Mohenjo-daro (in Sindh,Pakistan). Until now, Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan was considered the largest among the 2,000 Harappan sites known to exist in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. A recent report by the Archaeological Survey of India claims that Haryana’s Bhirrana is the oldest Harappan site and Rakhigarhi the biggest Harappan site in Asia.

Here are a few archaeological remains at Rakhigarhi

The excavated site

Clay toys found in rakhigarhi

The excavated grave had terracotta pots as funerary objects arranged placed around the head of the deceased, which suggest a believe in life after death.

Mud pots found in Rakhigarhi

Rakhigarhi Unearthed/FB

One of the skeletons found from Rakhigarhi is displayed in the National Museum, New Delhi.

wikimedia

Meanwhile, here's what you need to know about the Indus Valley Civilisation:

The Indus Valley civilization along with the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations are considered the earliest civilizations of the Old World. Also known as the Harappan civilization after Harappa- the first of its cities to be excavated in the 1920s in what was then Punjab province in British India. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were the two greatest cities of the civilization.

Published: May 2, 2014 00:11 IST | Updated: May 2, 2014 00:11 IST CHENNAI, May 2, 2014

Ancient granary found in Haryana

![The granary, built of mud bricks, at the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi village in Haryana. Photo: Rakhigarhi Project/Deccan College, Pune The granary, built of mud bricks, at the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi village in Haryana. Photo: Rakhigarhi Project/Deccan College, Pune]() Special ArrangementThe granary, built of mud bricks, at the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi village in Haryana. Photo: Rakhigarhi Project/Deccan College, Pune

Special ArrangementThe granary, built of mud bricks, at the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi village in Haryana. Photo: Rakhigarhi Project/Deccan College, Pune![A potsherd with a Harappan script unearthed in the excavation at the Harappan site of Rakhi Garhi in Haryana. Photo: D.Krishnan A potsherd with a Harappan script unearthed in the excavation at the Harappan site of Rakhi Garhi in Haryana. Photo: D.Krishnan]() The HinduA potsherd with a Harappan script unearthed in the excavation at the Harappan site of Rakhi Garhi in Haryana. Photo: D.Krishnan

The HinduA potsherd with a Harappan script unearthed in the excavation at the Harappan site of Rakhi Garhi in Haryana. Photo: D.Krishnan

The site belongs to the mature Harappan phase from 2600 BCE to 2000 BCE

A “beautifully made” granary, with walls of mud-bricks, which are still in a remarkably good condition, has been discovered in the just-concluded excavation at Rakhigarhi village, a Harappan civilisation site, in Haryana.

The granary has rectangular and squarish chambers. Its floor is made of ramped earth and plastered with mud.

Teachers and students of the Department of Archaeology, Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune, and Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak, Haryana, excavated at Rakhigarhi from January to April this year.

Vasant Shinde, Vice-Chancellor/Director, Deccan College, who was the Director of the excavation, said: “We excavated seven chambers in the granary. From the nature of the structure, it appears to be a big structure because it extends on all sides. We do not know whether it is a private or public granary. Considering that it extends on all sides, it could be a big public granary.” He called it “a beautifully-made structure.”

The excavating teams found several traces of lime and decomposed grass on the lower portion of the granary walls.

“This is a significant indication that it is a storehouse for storing grains because lime acts as insecticide, and grass prevents moisture from entering the grains. This is a strong proof for understanding the function of the structure,” explained Dr. Shinde, a specialist in the Harappan civilisation.

The discovery of two more mounds in Rakhigarhi in January this year led to Dr. Shinde arguing that it is the biggest Harappan civilisation site. There are about 2,000 Harappan sites in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. With the discovery of two more mounds, in addition to the seven already discovered, he estimated that the total area of Rakhigarhi was 350 hectares. It thus overtook Mohenjo-daro with about 300 hectares, in Pakistan, in laying claim to be the biggest Harappan site, he said.

The Rakhigarhi site belongs to the mature Harappan phase, which lasted from 2600 BCE to 2000 BCE. The teams have also found artefacts, including a seal and potsherd, both inscribed with the Harappan script.

In Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, granaries were found in citadels, where the ruling elite lived. So mound number four in Rakhigarhi, where the granary was found, could have been the settlement’s citadel, Dr. Shinde said.

Rakhigarhi is situated in the confluence of Ghaggar and Chautang rivers and it was a fertile area. “So Rakhigarhi must have grown a lot of food grains. They could have been stored in the granary to pay for the artisans or other sections of society or to meet any crisis,” said Dr. Shinde.

Printable version | May 3, 2016 3:11:21 PM | http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/ancient-granary-found-in-haryana/article5966952.ece

![The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early research that the Indus Valley civilization's Harappan phase originated in Sind, in present-day Pakistan. The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early research that the Indus Valley civilization's Harappan phase originated in Sind, in present-day Pakistan.]() The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early resea... Read More

The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early resea... Read More

![]()

![]()

A toy from 2300 BC. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint![photo]() Wazir Chand Saroae at his Rakhigarhi home. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintNow he can give you detailed descriptions of the various types of Harappan pottery and figurines, tell you about the great Harappan city that once stood where the village and its farmland is, down to town planning details, and walk you through the most important areas for archaeological excavations.

Wazir Chand Saroae at his Rakhigarhi home. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintNow he can give you detailed descriptions of the various types of Harappan pottery and figurines, tell you about the great Harappan city that once stood where the village and its farmland is, down to town planning details, and walk you through the most important areas for archaeological excavations.![photo]() Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintNew beginnings

Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintNew beginnings![photo]() Animal figurines from Sroae’s collection. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintEven though the Harappan or Indus Valley Civilization is one of the three oldest urban civilizations, along with Egypt and Mesopotamia, it is the least understood. Its script is yet to be deciphered, and the knowledge of social structures and life during that period is scant. Rakhigarhi promises to change this too. It is one of the few Harappan sites which has an unbroken history of settlement—Early Harappan farming communities from 6000 to 4500 BC, followed by the Early Mature Harappan urbanization phase from 4500 to 3000 BC, and then the highly urbanized Mature Harappan era from 3000 BC to the mysterious collapse of the civilization around 1800 BC. That’s more than 4,000 years of ancient human history packed into the rich soil.

Animal figurines from Sroae’s collection. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintEven though the Harappan or Indus Valley Civilization is one of the three oldest urban civilizations, along with Egypt and Mesopotamia, it is the least understood. Its script is yet to be deciphered, and the knowledge of social structures and life during that period is scant. Rakhigarhi promises to change this too. It is one of the few Harappan sites which has an unbroken history of settlement—Early Harappan farming communities from 6000 to 4500 BC, followed by the Early Mature Harappan urbanization phase from 4500 to 3000 BC, and then the highly urbanized Mature Harappan era from 3000 BC to the mysterious collapse of the civilization around 1800 BC. That’s more than 4,000 years of ancient human history packed into the rich soil.![photo]() Private collections of Harappan artefacts in the village, including fishing hooks and standardized weight measures. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintThe project aims to answer perhaps the most compelling question about the Harappan civilization—why did it disappear? The current assumption is that the shifting and dying away of ancient river systems led to the great Harappan cities to be abandoned. This is the first multidisciplinary and focused investigation into this assumption, bringing together archaeologists, historians, geographers and environmental scientists.

Private collections of Harappan artefacts in the village, including fishing hooks and standardized weight measures. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintThe project aims to answer perhaps the most compelling question about the Harappan civilization—why did it disappear? The current assumption is that the shifting and dying away of ancient river systems led to the great Harappan cities to be abandoned. This is the first multidisciplinary and focused investigation into this assumption, bringing together archaeologists, historians, geographers and environmental scientists.![photo]() The Harappan site at Rakhigarhi is used to dry cow dung. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintGround work

The Harappan site at Rakhigarhi is used to dry cow dung. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintGround work![photo]() Excavations in Rakhigarhi. Photo courtesy: Global Heritage FundThis is what the dead revealed: That burial had an important ritual significance even then, as sometimes only parts of the body were buried, the rest possibly lost in an unnatural death. A man, 35-40 years old, had only his femur and tibia interred. He was also the tallest of the lot here, at a little over 6.1ft. The largest pit (the size of the pit and the number of burial goods like pottery in it determine the socio-economic status of the person buried), had only two skulls, and a few small bones. One of those skulls, an adult male, had signs of a massive blunt object trauma on the left side of the cranial—a gaping crack that should have killed him.

Excavations in Rakhigarhi. Photo courtesy: Global Heritage FundThis is what the dead revealed: That burial had an important ritual significance even then, as sometimes only parts of the body were buried, the rest possibly lost in an unnatural death. A man, 35-40 years old, had only his femur and tibia interred. He was also the tallest of the lot here, at a little over 6.1ft. The largest pit (the size of the pit and the number of burial goods like pottery in it determine the socio-economic status of the person buried), had only two skulls, and a few small bones. One of those skulls, an adult male, had signs of a massive blunt object trauma on the left side of the cranial—a gaping crack that should have killed him.![Indus Valley Civ Ruins]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![http://www.hindustantimes.com/Images/popup/2015/4/digginsite01.jpg]()

![http://www.hindustantimes.com/Images/popup/2015/4/Sealandsealing01.jpg]()

![http://www.hindustantimes.com/Images/popup/2015/4/bangle01.jpg]()

![http://www.hindustantimes.com/Images/popup/2015/4/burialgravepot01.jpg]()

![http://www.hindustantimes.com/Images/popup/2015/4/toysdigging01.jpg]()

![]()

(After Fig. 68. Steatite seal and terracotta seal impression from Structure No. 1)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/dna-of-a-civilisation/article7194003.ece

![]() Archaeologists and scientists of Deccan College, Pune, examining a full-length skeleton of a male excavated from a burial site in Rakhigarhi in March. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

Archaeologists and scientists of Deccan College, Pune, examining a full-length skeleton of a male excavated from a burial site in Rakhigarhi in March. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

Pottery photographed in situ from a burial site. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

The skeleton of a woman found with the customary ritual pottery. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A series of burials with pottery excavated from a mound at Rakhigarhi in the midst of a vast expanse of wheat fields. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

Pottery which was found with the remains of a skeleton in a burial pit in the Late Harappan site of Chanayan in Baghpat district, Uttar Pradesh, in December 2014. These include pots, deep bowls and flasks and might have contained cereals, milk, butter, etc., as part of some religious ceremony for the dead. Photo:Archaeological Survey of India

![]()

Remains of the Harappan grid-planned settlement at Farmana. The picture shows circular pits with post holes in which the Early Harappans lived. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

Vasant Shinde, Vice-Chancellor of Deccan College, Pune, and director of the excavations at Rakhigarhi and Farmana. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

Nilesh P. Jadhav, Research Assistant, Deccan College, and co-director of the excavation at Rakhigarhi. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A pear-shaped potter's kiln built of clay and plastered on the inner side with fine silt, at Farmana. Its flat bottom and the sides are burnt red because of prolonged usage. Inside the circular portion of the kiln is a large brick, probably meant to support pots to be fired in it. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A fire altar excavated at Farmana. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A perfectly ribbed pot belonging to the Early Harappan phase excavated from one of the trenches at RGR-6 in Rakhigarhi. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

Pottery found in profusion at Rakhigarhi. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A view of the excavated burials which are adjacent to one another at Farmana. All the 70 burials here belong to the Mature Harappan phase. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

A broken copper crown with carnelian and faience beads, found at Chandayan village, Uttar Pradesh, in August 2014. Photo:Archaeological Survey of India

![]()

Terracotta bone copper chert faience lapis lazuli toy tools beads bangle from rakhigarhi excavation

![]()

Seal and Sealing from rakhigarhi mound no 4

![]()

The burials at Farmana are divided into primary, secondary and symbolic/ceremonial. In the primary burial (above), the body was placed in the pit along with ritual pottery, tools, beads, bangles and anklets. Photo:Deccan College, Pune![]()

The secondary burial (above) contains a few human bones and burial goods. It is likely that the body was kept in the open for several days and the bones that remained were collected and buried in the pit. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

![]()

In a symbolic burial (above), there are no bones at all. This means a person whose body could not be retrieved was given a ceremonial burial. Photo:Deccan College, Pune

http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/tales-from-the-dead/article7193919.ece

![]()

Archaeologists and scientists of Deccan College, Pune, examining a full-length skeleton of a male excavated from a burial site in Rakhigarhi in March.

![]()

Pottery photographed in situ from a burial site.

![]()

The skeleton of a woman found with the customary ritual pottery.

![]()

A series of burials with pottery excavated from a mound at Rakhigarhi in the midst of a vast expanse of wheat fields.

![]()

Pottery which was found with the remains of a skeleton in a burial pit in the Late Harappan site of Chanayan in Baghpat district, Uttar Pradesh, in December 2014. These include pots, deep bowls and flasks and might have contained cereals, milk, butter, etc., as part of some religious ceremony for the dead.

![]()

Remains of the Harappan grid-planned settlement at Farmana. The picture shows circular pits with post holes in which the Early Harappans lived.

http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/new-burial-sites-at-rakhigarhi/article7197274.ece![General view of the excavation Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Beads from Rakhigarhi]()

![Toy Cart frame from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Structural evidence from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Burials from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Pottery from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Bone tools from Rakhigarhi]()

![Terra cotta object and Dice]()

![Copper spoon from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Terra cotta Bangles from Rakhigarhi]()

![Statue seal from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Sling Balls from Rakhigarhi]()

![Terra cotta animal figurines from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Sealing impression from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Seal from Rakhigarhi]()

![Pottery kiln from Harappan site of Farmana]()

![Granery from Rakhigarhi]()

Rebus: H. gaṇḍaka m. ʻ a coin worth four cowries ʼ lex., ʻ method of counting by fours ʼ W. [← Mu. Przyluski RoczOrj iv 234] S. g̠aṇḍho m. ʻ four in counting ʼ; P. gaṇḍā m. ʻ four cowries ʼ; B. Or. H. gaṇḍā m. ʻ a group of four, four cowries ʼ; M. gaṇḍā m. ʻ aggregate of four cowries or pice ʼ.Addenda: gaṇḍaka -- . -- With *du -- 2 : OP. dugāṇā m. ʻ coin worth eight cowries ʼ.(CDIAL 4001)

![]()

Haryana's Bhirrana oldest Harappan site, Rakhigarhi Asia's largest: ASI

TNN | Apr 15, 2015, 04.02 AM IST

The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early resea... Read More

The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early resea... Read MoreCHANDIGARH: Asia's largest and oldest metropolis with gateways, built-up areas, street system and wells was built at the site of Haryana's two villages, including one on the Ghaggar river, according to a new Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) report.

The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early research that the Indus Valley civilization's Harappan phase originated in Sind, in present-day Pakistan.

The report, based on C 14 radio-dating, has said the mounds at Bhirrana village, on the banks of Ghaggar river, in Fatehabad district date back to 7570-6200 BC.

The previous Pakistan-French study had put Mehrgarh site in Pakistan as the oldest in the bracket of 6400-7000 BC. Mehrgarh is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River valley and between the Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi.

"The C 14 dates of excavations at Bhirrana readily agree with the accepted chronology of the Harappan civilization starting from Pre-Harappan to Mature Harappan. But for the first time, on the basis of radio-metric dates from Bhirrana, the cultural remains go back to the time bracket of 7300 BC," said the report.

The C 14 dating was done at Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleobotany in Lucknow over last 10 years.

![]()

The ASI report also said that that excavations done by its archaeologists between 1997 and 2005 reveal that a civilization site in Rakhigarhi village in Hisar district is spread over to 240 hectares.

While ASI stopped its excavation activity in Rakhigarhi, a team from Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune, which is carrying out further research, said the site's dimensions may go beyond 350 hectares with more excavations.

At this moment, Rakhigarhi has emerged as bigger in size than even the Mohenjedaro and Harappa sites in Pakistan and Dholavira in India's Gujarat with dimensions of 200, 150 and 100 hectares.

While the 356-page research on Rakhigarhi has been authored by former ASI's archaeology director Dr Amarendra Nath, the holistic study on Bhirrana has been compiled by ASI's former joint DG K N Dikshit and addtional DG B R Mani.

The archaelological excavations at Rakhigarhi and Bhirrana have revealed all the definite features of Indus civilization such as potter's kiln, an elaborate drainage system, a granary, ritualistic platforms and terracotta figurines.

The ASI report, submitted in December 2014, a copy of which is with TOI, has now also debunked the early research that the Indus Valley civilization's Harappan phase originated in Sind, in present-day Pakistan.

The report, based on C 14 radio-dating, has said the mounds at Bhirrana village, on the banks of Ghaggar river, in Fatehabad district date back to 7570-6200 BC.

The previous Pakistan-French study had put Mehrgarh site in Pakistan as the oldest in the bracket of 6400-7000 BC. Mehrgarh is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River valley and between the Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi.

"The C 14 dates of excavations at Bhirrana readily agree with the accepted chronology of the Harappan civilization starting from Pre-Harappan to Mature Harappan. But for the first time, on the basis of radio-metric dates from Bhirrana, the cultural remains go back to the time bracket of 7300 BC," said the report.

The C 14 dating was done at Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleobotany in Lucknow over last 10 years.

The ASI report also said that that excavations done by its archaeologists between 1997 and 2005 reveal that a civilization site in Rakhigarhi village in Hisar district is spread over to 240 hectares.

While ASI stopped its excavation activity in Rakhigarhi, a team from Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, Pune, which is carrying out further research, said the site's dimensions may go beyond 350 hectares with more excavations.

At this moment, Rakhigarhi has emerged as bigger in size than even the Mohenjedaro and Harappa sites in Pakistan and Dholavira in India's Gujarat with dimensions of 200, 150 and 100 hectares.

While the 356-page research on Rakhigarhi has been authored by former ASI's archaeology director Dr Amarendra Nath, the holistic study on Bhirrana has been compiled by ASI's former joint DG K N Dikshit and addtional DG B R Mani.

The archaelological excavations at Rakhigarhi and Bhirrana have revealed all the definite features of Indus civilization such as potter's kiln, an elaborate drainage system, a granary, ritualistic platforms and terracotta figurines.

Fri, Jan 04 2013. 05 18 PM IST

History | What their lives reveal

Haryana’s Rakhigarhi, where individuals possess ancient, priceless treasures, will soon be on the world heritage map

Rudraneil Sengupta

A toy from 2300 BC. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Wazir Chand Saroae is a slight, nearsighted man with a shuffling gait, the go-to man when electrical appliances in the village need fixing. His house is like any other here—compact, two-storeyed, neat. There are no signs at all to suggest that in a small room on the first floor of this house, Saroae is sitting on a treasure trove that is both priceless and timeless.

Displayed in rickety cabinets with glass fronts, Saroae’s treasure does not look like much—bits of pottery, beads of various sizes, a few clay figurines and toys—but their antiquity is stunning. The oldest things here date back to between 5000 BC and 4500 BC, the early phase of Harappan civilization. The most recent ones are from 2300 BC.

This is not entirely surprising in Rakhigarhi, a cluster of two sprawling villages—Rakhikhas and Rakhi Shahpur—in Haryana, around 170km from Delhi. People living here are used to finding little bits and pieces of ancient history—even 10 years ago, the villagers will tell you, you could not plough your field without unearthing a potsherd (bits of pottery—ceramic is exceptionally durable).

“When I was a child, I found particular pleasure in finding these pots and vases,” Saroae, 52, says. “And then dropping them from a height and breaking them.”

Wazir Chand Saroae at his Rakhigarhi home. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Wazir Chand Saroae at his Rakhigarhi home. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintThat Rakhigarhi was a large Harappan town was known in 1963, when the area was first surveyed. What archaeologists are finding out now is that it is the biggest ever Harappan city, larger and more extensive than the massive Mohenjo Daro.

“The whole site is around 400 hectares, which is nearly double that of Mohenjo Daro,” says Vasant Shivram Shinde, professor of archaeology and joint director of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Pune. “It’s in critical condition because of encroachment and construction.”

About 40% of the Rakhigarhi site is protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)—which translates to a fenced boundary wall and a guardroom with no guard. The wall is broken in several places, and the protected area is used by the villagers as a place to dry cow dung. The unprotected areas have houses and farmland. The ancient Harappan city lies buried under.

“People pick up Harappan objects from their fields and sell them for as little as `100,” says Saroae. “They don’t mean to do anything illegal; it’s just that they have little awareness about it.”

Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintAll of this is set to change. The Global Heritage Fund (GHF), a non-profit organization based in the US that works to preserve the world’s most endangered heritage sites, put Rakhigarhi on its project in 2012. This makes the Harappan site one of GHF's 13 projects worldwide, which include Ping Yao Ancient City in China and Ur in Iraq.

“The scope of this site should be emphasized,” says Dan Thompson, director, global projects, Global Heritage Network. “It is large and was occupied for a long period. The potential for research and knowledge is amazing, and I think that with skilled archaeologists, historians and designers, you can craft that knowledge into a compelling narrative that people will want to see.”

GHF will not only coordinate an ambitious excavation and conservation project at the site, led by Prof. Shinde, beginning this month, it will also work with the local community to develop home stays, train tour guides, and establish an on-site lab and museum with the help of the ASI, Deccan College, and other government agencies to turn Rakhigarhi into a heritage tourism hot spot.

“In our experience around the world, local communities are eager to cooperate and preserve the cultural heritage in their midst when they are included in the discussion and their concerns are addressed,” Thompson says. “The economic benefits that can come from heritage preservation are a great incentive to save these sites, as is the pride that communities derive from saving their past.”

For the few villagers in the know, like Saroae, this is a dream come true.

“I have been hoping for something like this from the time I began to understand the importance of this place,” says Saroae. “This work can’t come soon enough.”

Digging Haryana

Animal figurines from Sroae’s collection. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Animal figurines from Sroae’s collection. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintThat’s not all—intensive excavations in the last decade have revealed hundreds of Harappan sites all over Haryana. “Rakhigarhi was probably the centre of this vast collection of towns, villages and cities in the Haryana region,” says Prof. Shinde.

A collaborative project between Banaras Hindu University (BHU) and Cambridge University, which began in 2008, has been central to unearthing this trellis of Harappan towns. Their surveys uncovered 127 sites that spanned an incredible timeline from Early Harappan to early medieval (13th century) in the vicinity of Rakhigarhi, a majority of them unknown before; 182 sites spread across the area through which Haryana’s largest seasonal stream, Ghaggar, flows, 125 of which were unknown, and many more.

“In 2009, we excavated at Masudpur, which is 12km from Rakhigarhi, and discovered 13 sites that date back to the Early Harappan phase,” says Ravindra Nath Singh, from the department of ancient Indian history, culture and archaeology at BHU, and one of the leaders of the project. “It is highly likely that these sites fell under the socio-economic and political catchment area of Rakhigarhi.”

Private collections of Harappan artefacts in the village, including fishing hooks and standardized weight measures. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Private collections of Harappan artefacts in the village, including fishing hooks and standardized weight measures. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintEven though in archaeological terms the probe has just begun, the sheer number of discoveries is turning previous beliefs about the Harappan civilization on its head. Till recently, there was little evidence in India of a gradually developing civilization through the Harappan era. Most discoveries were from the Mature phase only, while in Pakistan, there was plenty of evidence of the earliest years of the culture. This led to the belief that the civilization took root in the regions now in Pakistan before gradually spreading eastward as it developed.

“Now the evidence suggests possibly the opposite,” says Prof. Shinde. “We’ve got a few sites now in Haryana which date all the way back to 6000 BC and it’s evident that this area was one of the first places in the world where humans graduated from a nomadic hunting-gathering lifestyle to settled agricultural communities.”

New carbon-dating tests on material found at an extensive Harappan site in Bhirrana, Haryana, have also thrown up some startling dates. In research led by B.R. Mani, ASI joint director-general, and K.N. Dikshit, former ASI joint director-general, charcoal and shell bangles found at Bhirrana date back to as early as 7380 BC. Like Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana was occupied from the earliest to the last dates of the Harappan era.

The Harappan site at Rakhigarhi is used to dry cow dung. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

The Harappan site at Rakhigarhi is used to dry cow dung. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/MintYet another site with the same epoch-bridging characteristic is Farmana, less than 50km from Rakhigarhi. Prof. Shinde and a team from Deccan College and Maharshi Dayanand University in Rohtak excavated this site from 2008-11. As they uncovered layer after layer of evidence, an extraordinary tableau was revealed.

First, a Harappan town with a population of around 3,000 and all the characteristics of the Mature phase—mud brick houses set in chessboard patterns, an elite central part of town, fortifications and industrial areas for potteries and copper and bronze artisans on the outskirts. In the layer below this, more modest, rectangular complexes of houses. Finally, buried deep, the first settlers, in circular pit dwellings dug into the earth.

“It’s such clear phases of development,” says Prof. Shinde, “that we are finally in a position to understand the progress of the civilization in some detail.”

There were more startling discoveries. Burnt rice found near the site dated back to 4000 BC, even though it is widely believed that rice only came to India from China in 2500 BC.

Then, on a winter afternoon in January 2008, as the archaeologists at Farmana were about to break for lunch, a farmer came and told them that he had found something while ploughing his field, a kilometre from the excavation site. What he had stumbled upon is one of the biggest Harappan burial sites ever discovered.

In all 71 burial pits and the skeletal remains of 35 individuals were found. These people died between 2400 and 2100 BC, at the height of the civilization. They were a diverse lot—adults, adolescents, children, men, women, rich and poor. The bones went to Veena Mushrif Tripathy, assistant professor of physical anthropology at the archaeology department at Deccan College, and an expert in the forensic study of ancient diseases.

Excavations in Rakhigarhi. Photo courtesy: Global Heritage Fund

Excavations in Rakhigarhi. Photo courtesy: Global Heritage Fund“But he lived for almost two months with that injury,” says Tripathy. “We can see the stages of healing. The only way he could have survived this is if he had some kind of medical attention and medication. He died only of secondary infections later.”

Tripathy, who is at the last stage of interpreting the data, says there is close resemblance in both bone and muscle structure between the 4,000-year-old citizens of Farmana and its current inhabitants. “They were big-boned, had big muscles, a healthy population, with no signs of infectious diseases or malnourishment,” she says.

Genome sequencing to compare DNA with Haryanvis now has so far been impossible because the wet, acidic earth destroys all DNA. Tripathy hopes that in the next three-four years she will be able to collect enough data from other sites, including Rakhigarhi, to be able to compare and find patterns.

“The Haryana region is fantastic if we do systematic scientific analysis,” she says. “Because it has everything when it comes to the Harappan civilization. We can reconstruct our early history with great accuracy, especially with a multidisciplinary approach.”

Lost and found

But this great Harappan network of towns and cities, buried for so many thousands of years, is in danger of being forgotten entirely. Much of the areas excavated in Farmana, Bhirrana, in and around Rakhigarhi are quickly being converted into farmland or land for housing, destroying the chances of preserving these sites. There are few preserved Harappan sites in India—Dholavira and Lothal in Gujarat, and Kalibangan in Rajasthan—none in Haryana.

Prof. Shinde says villagers are reluctant to let archaeologists even work in their areas because of the fear that a discovery will be made and the government will throw them out of their land.

“It’s difficult,” Prof. Shinde says. “The land is precious, and there is no clear, transparent procedure to acquire land for these purposes.” The excavated sites in Farmana, for example, have been turned into farmland, despite the ASI trying to enlist it as a nominee for the Unesco World Heritage list.

Only Rakhigarhi seems to be escaping this fate. It makes Saroae happy, even if that means his private collection might not remain with him much longer. “When the ancient city rises here, next to my house,” Saroae says, “I will go myself and put these things where they belong.”

http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/ljfXtPZHUSi5eG8Di1n9YO/History--What-their-lives-reveal.html

http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/ljfXtPZHUSi5eG8Di1n9YO/History--What-their-lives-reveal.html

Bhirrana. Oldest site of the civilization.http://www.mysteryofindia.com/2015/04/haryanas-bhirrana-oldest-harappan-site.html

"The report states that while the c 14 radio-dating of the excavations at the Mehrgarh site in Pakistan puts it in the 6400-7000 BC bracket while the latest study has revealed that the cultural remains at the Bhirrana village go back to the time bracket of 7300 BC. It is situated on the banks of Ghaggar river, in Fatehabad district of Haryana."

Rakhi Garhi – Cow Dung Cakes Stored on the 5000 year old site

http://www.sonalika.net/blog/?p=679

https://friendsofasi.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/picture1.jpg

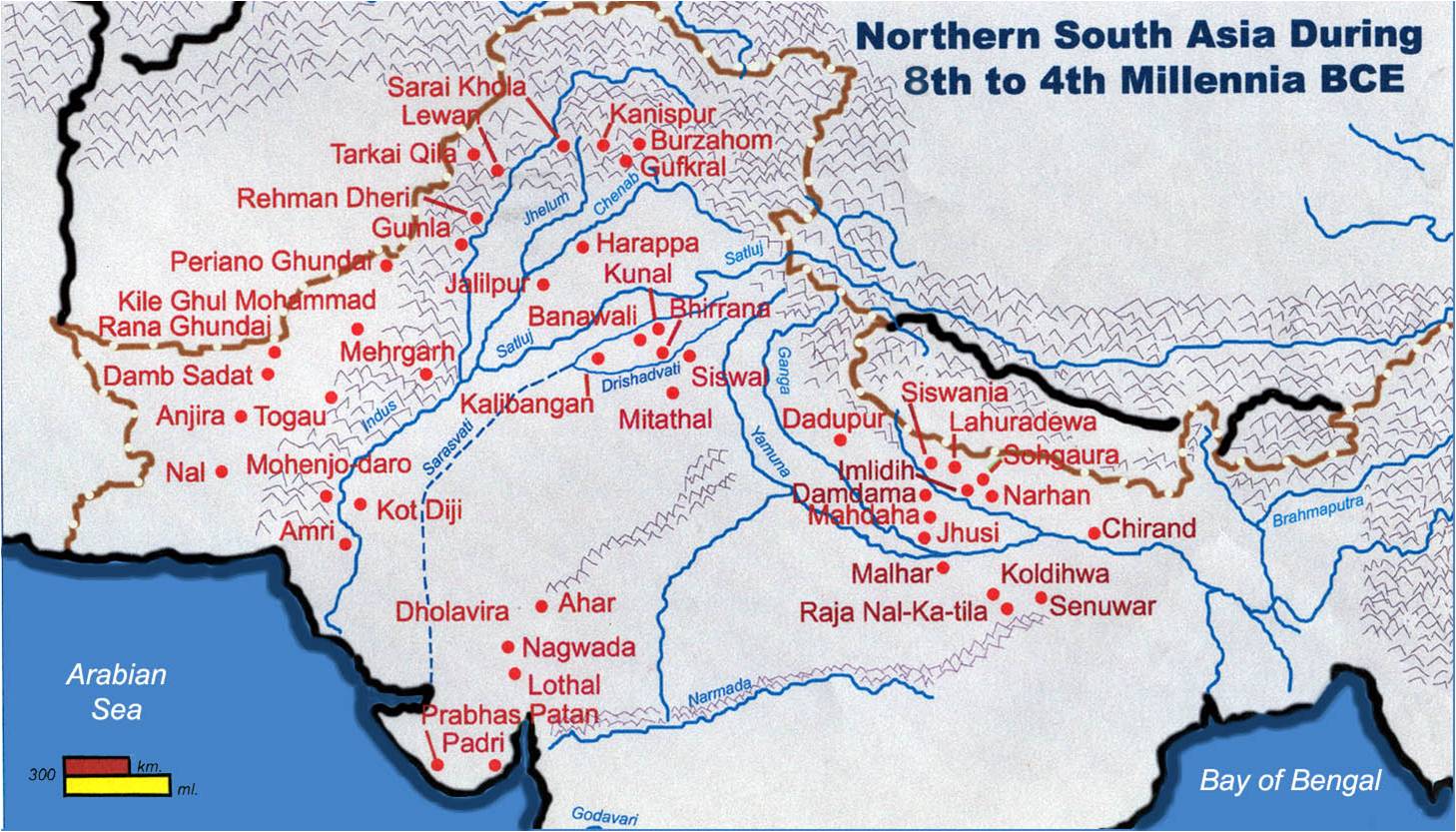

NOTE: There are no archaeological sites on the Sutlej course (present-day) west of Ropar, but there are sites south of Ropar proving the flow of Vedic River Sutlej into Vedic River Sarasvati to join the latter at Shatrana (width of paleochannel here is 20 kms.)

Can 'national heritage' Rakhigarhi survive for long

- Ishtiyaq Sibtian Joo, Hindustan Times, Rakhigarhi (Hisar) |

- Updated: Apr 18, 2015 17:02 IST

- With no landmarks or any sign boards to guide you, there is every possibility that you may miss one of the most archeologically important places in India-Rakhigarhi, a collective name given to the twin Haryana villages of Rakhi-khas and Rakhi-shahpur.

Spread over 350 acres of land Rakhigarhi is the biggest Harappan cities all across the world and it also the most important site of the Harappan civilization outside Mohenjodaro.

With less than 160 kms away from the country’s capital, the site has already made it to 10 most endangered heritage sites in Asia by the watchdog Global Heritage Fund due to official apathy.

The place which is attracting national as well as international tourists from all across the world could easily be misconstrued for business centre of dung cakes as ziggurats of dung cakes are found all across Rakhigarhi.

Guided by the locals you may end up at a digging site if you are visiting in between January and April. The digging in absence of any sign board appears like any other regular digging. However, on inquiring one gets briefed that it is an annual digging that Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, a deemed-to-be university in Pune is doing in collaboration with State Department of Archaeology Haryana.

This ancient city has nine localities which archeologists refer as mounds. The mounds are numerically named mound 1,2,3…and all have their significance in revealing various aspects of Harappan culture and civilization. Besides, they are also important from both historically as well as archaeologically point of view.

Presently digging is going on at mound 4. But even here piles of dung cakes are found.

Although, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is protecting Rakhigarhi as the national monument of the country, however, so far only 60 per cent of land is fenced by them.

Even the present digging site of mound 4 is fenced from one side only, while the villagers easily cross over the seat of old Harappan culture from the other three open sides.

Ironically mounds found in the private property of some villagers are at land owner’s mercy.

The callousness towards preserving national heritage is brazenly seen on mound 6. The mound which bears witness to how Harappans used to live is yet to be bought from the private owner of the land.

“Mound 6 is quite significant. Here we have found four different structures, which are made of mud, and mud bricks. Inside, them there is typical evidence of fire-place, which Harappans might have been using for cooking. Then we also found various pots there, which gives us impression that they were used for storage purposes,” informs Professor Vasant Shinde, Vice-Chancellor, Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute, a deemed-to-be university in Pune, and also director of the current project team.

Ask the professor what if the owner of the land decides to demolish the site and wants to do farming or construct some structure there, optimistic Shinde says, “For first two years before starting this project, we were just meeting villagers to educate them about the importance of preserving the sites. Now they are convinced that land should be preserved,” the director said.

He even believes that farmers are ready to leave the land if given proper compensation.

There are reasons to believe the director project’s words, as it is the village panchayat which has come forward to donate the land of more than six acres of their land for the construction of museum here.

But then there are also instances where villagers or their children are still selling whatever, antiquates they find in the fields to the visitors at dirt price of Rs 100- Rs 200.

Rakhigarhi is a treasure trove of Harappan pottery, antiquities, terracotta bangles, various exotic stones, and different sizes of beads, figurines, toys, and now with the discovery of cemetery on mound 7, its significance has increased manifolds.

The latest finding of four 5000-year-old complete human skeletons which were found this year, has excited the Shinde and his team, and now they are in pursuit to extract DNA from them to unfold the mystery surrounding Harappans.

“These are some exciting times. The skeletons found out here have given us a new hope to decipher the mystery surrounding Harappans. Our preliminary observation has revealed that we may get DNA samples from the skeletons. If it happens, we can shed more light on physical appearance of Harappans by doing their 3-D reconstruction. We can figure out the colour of their skin, their eyes and other things,” says, Professor Shinde.

People have built houses over archaeological remains as much of the Harappan site at Rakhigarhi lies buried under the present-day village.

The director also along with this team is trying hard to make the Rakhigarhi significant on world map.

“Once the significance of site is recognized, which if all goes as per the plan may be next year, then, we can post it for candidature of world heritage site,” reveals the director.

However, to do that the site needs to be protected. Although ASI has posted two guards at one of the mounds, however, their existence also seems to be like a mystery as no one ever knows where they are, even when you look for them.

The Rakhigarhi has two Harappan stages, early Harappan phase, also called as Harappan culture stage dating back to 5500 BC- 2700 BC, and mature stage, also referred as stage of civilization dating from 2600 BC-2000 BC.

According to Dr. Shinde Harappan were very intelligent people as they were the pioneers to develop basic sciences and technologies.

“Traditional knowledge was developed by them and it continued till modern times, and is still relevant,” says, the archaeologist.

However, little did Harappans know that the place they lived and thrived for so many years, would fail to keep their remains.

With no state museum to hold the excavations from here, Deccan College Poona would keep Haryana’s treasure till the state will built one of its own.

“Whatever, remains extracted from here should remain here in the museum. However, till it is constructed, Deccan College will keep hold of the excavation products,” says, Shinde, who informs that the aim of the project was to develop the site into a tourism place of visitors from all over world to see.

Shinde and his team are planning to excavate a part of city like an open air museum and preserve it for general public. However, the big question that needs to be answered is if Rakhigarhi with no government support will survive that long.

Farmana, Rakhigarhi in Ghaggar basin yield inscribed potsherd, seals, seal impression: Meluhha metalwork catalogues

Following the Rakhigarhi Excavation Report of 1997-2000 by Amarendra Nath, an archaeological team of Deccan College, Pune led by Vasant Shinde has reportedly submitted a report of excavations 2014-15 at Rakhigarhi.

Links:

This note highlights this report of May 2015 in the context of other excavations at Farmana which is also, like Rakhigarhi, an archaeological site in Ghaggar river basin.

One view is that this Ghaggar river basin was in fact the Sarasvati River basin of Vedic times when Vedic Sutlej was a tributary of Sarasvati River flowing southwards from Ropar. The present-day Sutlej river channel is seen to take a U-turn at Ropar to flow westwards to join Sindhu River. This westward migration of River Sutlej abandoning River Sarasvati is explained as caused by plate tectonics which is an ongoing seismotectonic feature of continental drift and ongoing formation of dynamic Himalayas as the Indian Plate juts into and lifts up the Eurasian Plate.

The finds of potsherd and seals with with inscription at Rakhigarhi and Farmana are metalwork catalogues; the inscriptions deploy Indus Script. The artisans were metalcaster folk, designated as Bharatam Janam in Rigveda which adores the River Sarasvati in 72 rica-s as the best of rivers, नदीतमे nadItame.

The following inscribed potsherd, seals and seal impressions from Farmana and Rakhigarhi are deciphered using rebus-metonymy layered cipher of Indus Script. They are documents which constitute metalwork catalogues like all other inscriptions in Indus Script Corpora.

A potsherd with a Harappan script unearthed in the excavation at the Harappan site of Rakhi Garhi in Haryana. Photo: D.Krishnan http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/ancient-granary-found-in-haryana/article5966952.ece

Hieroglyph: 'rim-of-jar': Phonetic forms: kan-ka (Santali) karṇika (Sanskrit) Rebus: karṇī, supercargo for a boat shipment. karṇīka ‘account (scribe)’.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal + ()kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) Thus, bronze casting.

sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop'

ayo 'fish' Rebus: ayo 'iron, metal'

kamaDha 'bow' Rebus: kampaTTa 'mint' kANDa 'arrow'; ..kANDa 'tools, pots and pans, metalware'

Seal and sealing fom Mound No. 4, Rakhigarhi http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/dna-of-a-civilisation/article7194003.ece

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull

kõdā खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) Rebus 1: kọ̆nḍu or konḍu । कुण्डम् m. a hole dug in the ground for receiving consecrated fire (Kashmiri) Rebus 2: A. kundār, B. kũdār, °ri, Or. kundāru; H. kũderā m. ʻ one who works a lathe, one who scrapes ʼ, °rī f., kũdernā ʻ to scrape, plane, round on a lathe ʼ.(CDIAL 3297).

Hieroglyph: rāngo ‘water buffalo bull’ (Ku.N.)(CDIAL 10559) Rebus: rango ‘pewter’. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali)

Hieroglyphs: dul 'two'; ayo 'fish'; kANDa 'arrow': dula 'cast' ayo 'iron, metal' (Gujarati. Rigveda); kANDa 'metalware, pots and pans, tools' (Marathi) Hieroglyph: Rings on neck: koDiyum (Gujarati) koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (Gujarati)Rebus: koD 'artisan's workshop'(Kuwi) koD = place where artisans work (Gujarati) koṭe 'forge' (Mu.) koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari)

Hieroglyph: one-horned young bull

kõdā खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) Rebus 1: kọ̆nḍu or konḍu । कुण्डम् m. a hole dug in the ground for receiving consecrated fire (Kashmiri) Rebus 2: A. kundār, B. kũdār, °ri, Or. kundāru; H. kũderā m. ʻ one who works a lathe, one who scrapes ʼ, °rī f., kũdernā ʻ to scrape, plane, round on a lathe ʼ.(CDIAL 3297).

Hieroglyph: 'rim-of-jar': Phonetic forms: kan-ka (Santali) karṇika (Sanskrit) Rebus: karṇī, supercargo for a boat shipment. karṇīka ‘account (scribe)’.

Hieroglyph: sprout ligatured to rimless pot: baṭa = rimless pot (Kannada) Rebus: baṭa = a kind of iron; bhaṭa 'furnace; dul 'pair' Rebus: dula 'cast (metal) kolmo 'sprout' Rebus: kolami 'smithy/forge' Thus the composite hieroglyph: furnace, metalcaster smithy-forge

Hieroglyph:मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick) Rebus: meḍ 'iron'.

(After Fig. 68. Steatite seal and terracotta seal impression from Structure No. 1)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

May 18, 2015

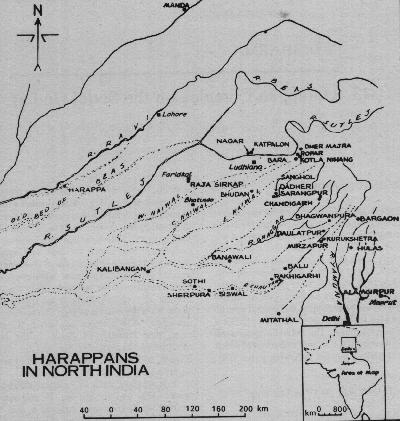

Location of archaeological sites: Farmana, Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana, Mitathal, Kalibangan between present-day Sutlej and Yamuna Rivers south of Siwalik ranges (After Fig. 1 in: Shinde, Vasant, et al., Exploration in the Ghaggar basin and excavations at Girawad, Farmana (Rohtak Dist.) and Mitathal (Bhiwani Dist.), Haryana, India, pp. 77-158 in: Osada Toshiki, Akinori Uesugi, 2008, Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past, Kyoto, Japan, Indus Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Naturehttp://southasia.world.coocan.jp/Shinde_et_al_2008a.pdf )

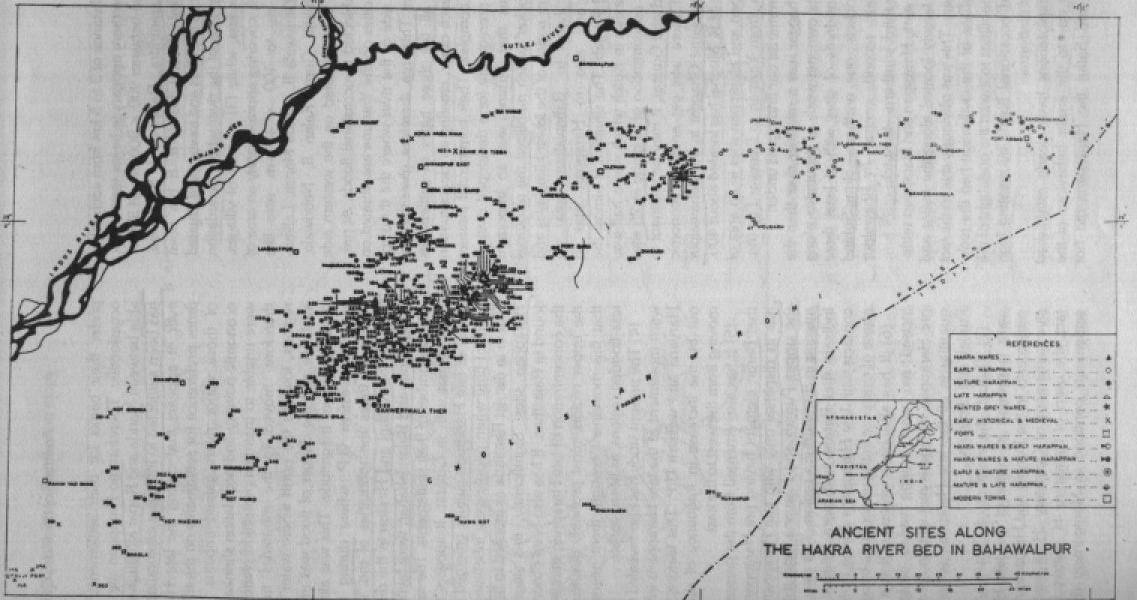

A reconstruction of palaeochannels including flows from tributary Sutlej south of Ropar (where Sutlej had taken a U-turn to abandon Sarasvati river and migrate westwards to join Sindhu river)

An extension of Sarasvati River into Cholistan. Diverted Sutlej river joining Panjnad which joins Sindhu river. There are NO archaeological sites on this Sutlej basin, but there are over 400 sites on Sarasvati River basin (present-day names: Ghaggar-Hakra-Nara)

Palaeo-drainage map of Thar desert region using IRS P3 WiFS satellite image

Published: May 13, 2015 12:30 IST | Updated: May 13, 2015 12:00 IST

DNA of a civilisation

BY T. S. SUBRAMANIANletal remains excavated from Rakhigarhi in Haryana will prove useful in understanding the Harappans’ features, lifestyle and culture. By T.S. WHAT did the Harappan man look like? Was he well built? How tall was he? What were his facial features? What was the colour of his skin, eyes and hair? What were the dietary habits of the Harappans?The answers to these questions, which have been puzzling archaeologists for several decades, lie in the DNA test results of four skeletons excavated from Rakhigarhi, a Harappan site in Haryana. The results are expected in July. The tests are jointly conducted by archaeologists of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute in Pune and forensic scientists from Seoul National University, South Korea. Two of the skeletons, belonging to the Mature Harappan period (2600-1900 BCE), are of adult males, one is of an adult female, and the fourth is of a child.

The growth and development of the Harappan civilisation can be divided into Early Harappan (3000-2600 BCE), Mature Harappan (2600-1900 BCE) and Late Harappan (1900-1500 BCE) phases. “For the first time, we are going to show the world what the Harappan man looked like. It will be a breakthrough in Harappan studies,” said Vasant Shinde, director of the excavation at Rakhigarhi and a specialist on Harappan civilisation. He is the Vice-Chancellor of Deccan College, a deemed university.

The excavation at Rakhigarhi, 25 kilometres from Jind town in Haryana’s Hisar district, is conducted jointly by Deccan College and the Haryana Department of Archaeology. Twenty-one trenches, besides the four burials, were dug during the excavation which began on January 23 and ended in the third week of April.

“We excavated the burials scientifically at Rakhigarhi. If you want to study the DNA, you have to avoid contamination. So we took precautions. We wore suits, gloves and masks. All four skeletons were in good condition,” said Shinde.

The facial bones of two skeletons are intact. Shinde said software developed by forensic scientists of Seoul National University to reconstruct facial features from skeletons would come in handy to reconstruct the Harappan man. “With the help of this software, we can analyse the height of the Harappan person, his facial and body features, and the colour of his skin, eyes and hair. The skeletal remains will be subjected to chemical tests to find the health status of the Harappan people and the diet they had,” he said. It will give insights into whether they preferred a vegetarian diet or not and whether malnutrition was a cause of death among them.

The six months of excavation from November 2014 in Rakhigarhi, the 4MSR site in Rajasthan and Chandayan in Uttar Pradesh revealed a lot of burials with Harappan skeletons. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) excavated one skeleton at 4MSR in March (“Harappan surprise”, Frontline, April 17). Its archaeologists, led by A.K. Pandey, found a copper crown on the skull of a skeleton at Chandayan in Baghpat district in November. This belongs to the Late Harappan period.

However, what was astounding was the discovery of a cemetery with 70 burials, most of them with skeletons, at the site at Farmana in Haryana. Spread over 3.5 hectares, it is the largest cemetery found in any of the Harappan sites in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Most of the skeletons in the 70 burials were found adjacent to one another. Some were found below others, signifying that they belonged to an earlier period. Archaeologists belonging to Deccan College, the Research Institute of Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan, and Maharshi Dayanad University, Rohtak, Haryana, discovered the Farmana cemetery in 2007-08 in their second field season of excavation.

The aim of the excavation at Rakhigarhi was not merely to understand the burial customs of the time, which earlier excavations at Farmana had revealed, but “to study the socio-economic conditions of the Harappans from the size of the burial pits, and the quality and quantity of the burial goods kept along with the dead body,” said Shinde. “Secondly, and more importantly, we want to find out from the DNA testing of the skeletons who the Harappans were, how they looked, what their build was, and so on.”

A lot of broken pottery and charred animal bones were found outside the burial pits at Rakhigarhi. This points to some rituals that had taken place before a body was placed inside the pit. The pots were perhaps broken after the body was placed inside it. Evidence of this kind of ritual was not available at other Harappan sites. Burial customs would have differed from one Harappan site to another.

There are about 2,000 Harappan sites in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. In India, they are situated in Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Haryana. The civilisation’s southern-most outpost was at Daimabad in Maharashtra. In Haryana alone, there are more than 100 Harappan sites. They include Adi-Badri, Balu, Banawali, Bhagwanpura, Daulatpur, Farmana, Girawad, Mirzapur, Rakhigarhi and Shamlo Kalan, all situated on the banks of the Ghaggar, which is the modern name for the Saraswati river.

Rakhigarhi is situated in the valley falling between the Ghaggar and Drishadvati rivers, a fertile region with large expanses of wheat fields. Excavation at Rakhigarhi is challenging because the ancient Harappan site lies buried under several hundred houses and lanes and alleys teeming with life.

However, there are seven mounds, numbered RGR-1 to RGR-7, that lend themselves to excavation. While the first six have hidden in their innards Harappan habitational sites, RGR-7 is a burial mound belonging to the Mature Harappan phase. R.S. Bisht, former Joint Director General of the ASI, had identified two mounds besides these seven in the late 1970s. They are locally called Arada mounds and are reportedly older than the Harappan civilisation.

The ASI began excavation at Rakhigarhi in 1998 and continued it in the next two years; Amarendra Nath was the director of excavations for all the three years. Teachers and students of Deccan College and the Haryana State Department of Archaeology came together to dig RGR-4 and RGR-6 and the burial site near Arada mounds from January to April this year. Nilesh P. Jadhav, Research Assistant at Deccan College, and Ranvir Shastry of the Haryana State Department of Archaeology, were the co-directors of the excavation. While A. Deshpande and Pankaj Goyal did specialised scientific studies of the artefacts and the animal bones found in the trenches, Satish Nayak investigated the botanical remains. Others who took part in the excavation were Deccan College’s Yogesh Yadhav, Shalmali Mali, Malvika Chatterjee and Nagaraja Rao.

Mature Harappan deposits

RGR-4 is the biggest mound at Rakhigarhi. “The aim of our work here was to go down to the natural soil level from the top of the mound. We have gone to a depth of 18 metres. It is going deeper,” said Shinde. The Mature Harappan deposits were found above 7.5 metres, which indicates a very long period of habitation at the same site. Typical Mature Harappan pottery of different kinds was found at the site. What surprised excavators was a large number of goblets of various varieties. An extension of the granary, which had been uncovered last year in RGR-4, was found this year.

Along with the Early Harappan pottery was found pottery used by local people, indicating “the assemblage or regional cultures”.

Significantly, Harappan pottery found in the Ghaggar basin was not profusely painted. “But at Rakhigarhi,” Shinde said, “we do get a large amount of profusely painted Harappan pottery. This indicates the status of the site in the Saraswati basin. Perhaps, important people were living there. This site obviously controlled small and medium-sized sites in the Saraswati basin. So Rakhigarhi can be called a type site in the entire basin. That is why we are getting so much of classical pottery of the Mature Harappan phase,” he said.

Surprisingly, hundreds of perfectly turned-out idli-shaped terracotta cakes were found in the trenches at Rakhigarhi. (A similar cache of pottery was found during the excavation at 4MSR from January to April.) In comparison, not so many idli-shaped terracotta cakes were found at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, both in Pakistan now. It is surmised that these cakes could have gone from Rakhigarhi to Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.