Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hwkyva6

Data mining of Indus Script hieroglyph clusters names Bronze Age professionals: damgar'merchant, khār'smith', ṭhākurʻblacksmithʼ খোন্দকার 'farmer' in कोंड 'hamlets'. The composite anthropomorph of a crocodile, ram, one-horned young bull signifies this combined professionalism of farming, metalwork and seafaring trade (boatman). [A synonym for ram is meDha 'ram' rebus: med'drummer, boatman, basketmaker'; meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic languages)].mēda m. ʻ a mixed caste, any one living by a degrading occupation ʼ Mn. [→ Bal. mēd ʻ boatman, fisher- man ʼ. -- Cf. Tam. metavar ʻ basket -- maker ʼ &c. DED 4178]Pk. mēa -- m., mēī -- f. ʻ member of a non -- Aryan tribe ʼ; S. meu m. ʻ fisherman ʼ (whence miāṇī f. ʻ a fishery ʼ), L. mē m.; P. meũ m., f. meuṇī ʻ boatman ʼ. -- Prob. separate from S. muhāṇo m. ʻ member of a class of Moslem boatmen ʼ, L. mohāṇā m., °ṇī f.: see *mr̥gahanaka -- . (CDIAL 10320).

An important official named in a cuneiform text was 'chief of merchants' (LU rab tamkaru). (Jonas Carl Greenfield, Ziony Zevit, Seymour Gitin, Michael Sokoloff, 1995, Solving Riddles and Untying Knots: Biblical, Epigraphic, and Semitic Studies in Honor of Jonas C. Greenfield, Eisenbrauns, p. 527). The gloss tamkaru is cognte damgar (Akkadian) and also ṭhākur ʻblacksmithʼ.)

These professionals constitute the bhāratam janam blessed by Rishi

Visvamitra in Rigveda (RV 3.53.12). They are Sarasvati's children since 80# of the archaeological sites of the civilization which are a continuum of Vedic culture signified by yupa (see octagonal yupa found in Binjore Soma Yaga yajna kunda) are found in Vedic River Sarasvati Basin in Northwest Bharatam.

Wheat chaff on Yupa as caSAla: *kuṇḍaka ʻ husks, bran ʼ.Pa. kuṇḍaka -- m. ʻ red powder of rice husks ʼ; Pk. kuṁḍaga -- m. ʻ chaff ʼ; N. kũṛo ʻ boiled grain given as fodder to buffaloes ʼ, kunāuro ʻ husk of lentils ʼ (for ending cf.kusāuro ʻ chaff of mustard ʼ); B. kũṛā ʻ rice dust ʼ; Or. kuṇḍā ʻ rice bran ʼ; M. kũḍā, kõ° m. ʻ bran ʼ; Si. kuḍu ʻ powder of paddy &c.(CDIAL 3267) Rebus: kuṇḍa 'vedic altar, fire place, yagashala'.

Two professionals are signified by a composite hieroglyph-multiplex signified on a bronze artifact as a composite anthropomorphic metaphor with hieroglyphs: crocodile, ram, one-horned young bull. Each hieroglyph component in the multiplex has a history in Indus Script Corpora signifying metalwork catalogues.

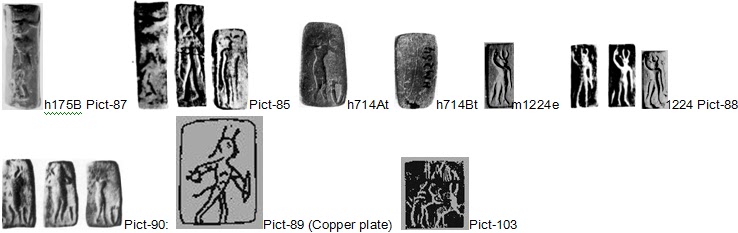

An animal-headed anthropomorph. A clipped enlargement of the Indus Script 'inscription' from the photograph.

An animal-headed anthropomorph. A clipped enlargement of the Indus Script 'inscription' from the photograph.1. Smith, turner, engraver, merchant

kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) Rebus: kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

tagara 'ram' (Kannada) Rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian) tagara 'tin' (Kannada) The semantics of damana 'blowing with bellows' links with the dam- prefix in: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian), perhaps a merchant of products out of the furnace/smelter.

2. Farmer, producer of crops, who live in circular hamlets कोंड [kōṇḍa] (Marathi) kɔṛi f. ʻ cowpenʼ (Gondi)

Hieroglyph: khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' Rebus 1: kũdār ‘turner’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) Rebus 2: kuḍu śūdra, farmer (Kannada); n crop (রবিখন্দ ). ̃ কার, খোন্দকার n. a producer of crops, a farmer; a (Mus lim) title of honour awarded to wealthy farmers.kara, khondakara n. a producer of crops, a farmer; a (Mus lim) title of honour awarded to wealthy farmers (Bengali).कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste.

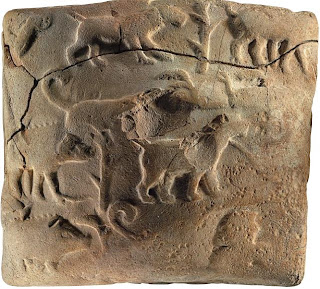

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820These inlaid mosaics, composed of figures carved in mother-of-pearl, against a background of small blocks of lapis lazuli or pink limestone, set in bitumen, are among the most original and attractive examples of Mesopotamian art. It was at Mari that a large number of these mosaic pieces were discovered. Here they depict a victory scene: soldiers lead defeated enemy captives, naked and in chains, before four dignitaries.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets of standards held up on a procession including a standard signifying a one-horned young bull. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-art-indus-writing.html

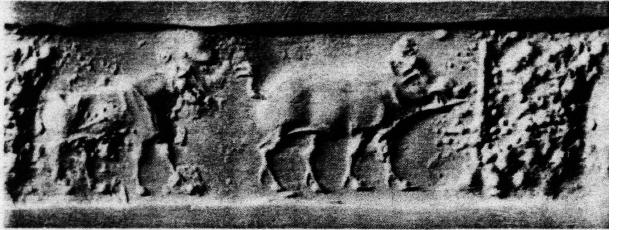

Bulls emerging out of a cowshed. This is a metaphor for a temple, a smithy: kole.l Signifiers: erava 'reed' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper'.![]() mēda

mēda 10320 mēda m. ʻ a mixed caste, any one living by a degrading occupation ʼ Mn. [→ Bal. mēd ʻ boatman, fisher- man ʼ. -- Cf. Tam. metavar ʻ basket -- maker ʼ &c. DED 4178]

Pk. mēa -- m., mēī -- f. ʻ member of a non -- Aryan tribe ʼ; S. meu m. ʻ fisherman ʼ (whence miāṇī f. ʻ a fishery ʼ), L. mē m.; P. meũ m., f. meuṇī ʻ boatman ʼ. -- Prob. separate from S. muhāṇo m. ʻ member of a class of Moslem boatmen ʼ, L. mohāṇā m., °ṇī f.: see *mr̥gahanaka -- .

mēda

mēda Pk. mēa -- m., mēī -- f. ʻ member of a non -- Aryan tribe ʼ; S. meu m. ʻ fisherman ʼ (whence miāṇī f. ʻ a fishery ʼ), L. mē m.; P. meũ m., f. meuṇī ʻ boatman ʼ. -- Prob. separate from S. muhāṇo m. ʻ member of a class of Moslem boatmen ʼ, L. mohāṇā m., °ṇī f.: see *

మేడము (p. 1034) [ mēḍamu ] mēḍamu. [Tel.] n. Joining,union, కూడిక . A fight, battle, యుద్ధము . మేడము పొడుచు mēdamu-poḍuṭsu. v. n. To fight a battle. యుద్ధముచేయు , కోడిమేడము a cock fight.

1655 Ta. kuṭi house, abode, home, family, lineage, town, tenants; kuṭikai hut made of leaves, temple; kuṭical hut; kuṭicai, kuṭiñai small hut, cottage; kuṭimai family, lineage, allegiance (as of subjects to their sovereign), servitude; kuṭiy-āḷ tenant; kuṭiyilār tenants; kuṭil hut, shed, abode; kuṭaṅkar hut, cottage; kaṭumpu relations. Ma.kuṭi house, hut, family, wife, tribe; kuṭima the body of landholders, tenantry; kuṭiyan slaves (e.g. in Coorg); kuṭiyān inhabitant, subject, tenant; kuṭiññil hut, thatch;kuṭil hut, outhouse near palace for menials. Ko. kuṛjl shed, bathroom of Kota house; kuṛm family; kuḍḷ front room of house; kuṛḷ hut; guṛy temple. To. kwïṣ shed for small calves; kuṣ room (in dairy or house); kuḍṣ outer room of dairy, in: kuḍṣ was̱ fireplace in outer room of lowest grade of dairies (cf. 2857), kuḍṣ moṇy bell(s) in outer section of ti· dairy, used on non-sacred buffaloes (cf. 4672); kuṛy Hindu temple; ? kwïḏy a family of children. Ka. kuḍiya, kuḍu śūdra, farmer; guḍi house, temple; guḍil, guḍalu, guḍisalu, guḍasalu, guḍasala, etc. hut with a thatched roof. Koḍ. kuḍi family of servants living in one hut; kuḍië man of toddy-tapper caste. Tu.guḍi small pagoda or shrine; guḍisalů, guḍisilů, guḍsilů, guḍicilů hut, shed. Te. koṭika hamlet; guḍi temple; guḍise hut, cottage, hovel. Kol. (SR) guḍī temple. Pa. guḍitemple, village resthouse. Ga. (Oll.) guḍi temple. Go. (Ko.) kuṛma hut, outhouse; (Ma.) kurma menstruation; (Grigson) kurma lon menstruation hut (Voc. 782, 800); (SR.) guḍi, (Mu.) guḍḍi, (S. Ko.) guṛi temple; guḍḍī (Ph.) temple, (Tr.) tomb (Voc. 1113). Kui guḍi central room of house, living room. / Cf. Skt. kū˘ṭa-, kuṭi-, kū˘ṭī- (whence Ga. (P.) kuṛe hut; Kui kūṛi hut made of boughs, etc.; Kur. kuṛyā small shed or outhouse; Malt. kuṛya hut in the fields; Br. kuḍ(ḍ)ī hut, small house, wife), kuṭīkā-, kuṭīra-, kuṭuṅgaka-, kuṭīcaka-, koṭa- hut;kuṭumba- household (whence Ta. Ma. kuṭumpam id.; Ko. kuṛmb [? also kuṛm above]; To. kwïḍb, kwïḍbïl [-ïl from wïkïl, s.v. 925 Ta. okkal]; Ka., Koḍ., Tu.kuṭumba; Tu. kuḍuma; Te. kuṭumbamu; ? Kui kumbu house [balance word of iḍu, see s.v. 494 Ta. il]). See Turner, CDIAL, no. 3232, kuṭī-, no. 3493, kōṭa-, no. 3233, kuṭumba-, for most of the Skt. forms; Burrow, BSOAS 11.137.

kōṭa3 m. ʻ hut, shed ʼ lex. [← Drav. T. Burrow TPS 1945, 95: cf. kuṭī -- ]

G. kɔṛi f. ʻ cowpen ʼ.(CDIAL 3493)

G. kɔṛ

2049 Ta. koṭi banner, flag, streamer; kōṭu summit of a hill, peak, mountain; kōṭai mountain; kōṭar peak, summit of a tower; kuvaṭu mountain, hill, peak; kuṭumisummit of a mountain, top of a building, crown of the head, bird's crest, tuft of hair (esp. of men), crown, projecting corners on which a door swings. Ma. koṭi top, extremity, flag, banner, sprout; kōṭu end; kuvaṭu hill, mountain-top; kuṭuma, kuṭumma narrow point, bird's crest, pivot of door used as hinge, lock of hair worn as caste distinction; koṭṭu head of a bone. Ko. koṛy flag on temple; koṭ top tuft of hair (of Kota boy, brahman), crest of bird; kuṭ clitoris. To. kwïṭ tip, nipple, child's back lock of hair. Ka. kuḍi pointed end, point, extreme tip of a creeper, sprout, end, top, flag, banner; guḍi point, flag, banner; kuḍilu sprout, shoot; kōḍu a point, the peak or top of a hill; koṭṭu a point, nipple, crest, gold ornament worn by women in their plaited hair; koṭṭa state of being extreme; koṭṭa-kone the extreme point; (Hav.) koḍi sprout; Koḍ.koḍi top (of mountain, tree, rock, table), rim of pit or tank, flag. Tu. koḍi point, end, extremity, sprout, flag; koḍipuni to bud, germinate; (B-K.) koḍipu, koḍipelů a sprout; koḍirè the top-leaf; koṭṭu cock's comb, peacock's tuft. Te. koḍi tip, top, end or point of a flame; koṭṭa-kona the very end or extremity. Kol. (Kin.) koṛi point. Pa.kūṭor cock's comb. Go. (Tr.) koḍḍī tender tip or shoot of a plant or tree; koḍḍi (S.) end, tip, (Mu.) tip of bow; (A.) koḍi point (Voc. 891). Malt. qoṛg̣o comb of a cock; ?qóru the end, the top (as of a tree). Cf. 2081 Ta. koṇṭai and 2200 Ta. kōṭu.

2081 Ta. koṇtai tuft, dressing of hair in large coil on the head, crest of a bird, head (as of a nail), knob (as of a cane), round top. Ma. koṇṭa tuft of hair. Ko. goṇḍ knob on end of walking-stick, head of pin; koṇḍ knot of hair at back of head. To. kwïḍy Badaga woman's knot of hair at back of head (< Badaga koṇḍe). Ka. koṇḍe, goṇḍe tuft, tassel, cluster. Koḍ. koṇḍe tassels of sash, knob-like foot of cane-stem. Tu. goṇḍè topknot, tassel, cluster. Te. koṇḍe, (K. also) koṇḍi knot of hair on the crown of the head. Cf. 2049 Ta. koṭi. / Cf. Skt. kuṇḍa- clump (e.g. darbha-kuṇḍa-), Pkt. (DNM) goṇḍī- = mañjarī-; Turner, CDIAL, no. 3266; cf. also Mar. gōḍā cluster, tuft.

3266 kuṇḍa3 n. ʻ clump ʼ e.g. darbha -- kuṇḍa -- Pāṇ. [← Drav. (Tam. koṇṭai ʻ tuft of hair ʼ, Kan. goṇḍe ʻ cluster ʼ, &c.) T. Burrow BSOAS xii 374]

Pk. kuṁḍa -- n. ʻ heap of crushed sugarcane stalks ʼ; WPah. bhal. kunnū m. ʻ large heap of a mown crop ʼ; N. kunyũ ʻ large heap of grain or straw ʼ, baṛ -- kũṛo ʻ cluster of berries ʼ.

Pk. kuṁḍa -- n. ʻ heap of crushed sugarcane stalks ʼ; WPah. bhal. kunnū m. ʻ large heap of a mown crop ʼ; N. kunyũ ʻ large heap of grain or straw ʼ, baṛ -- kũṛo ʻ cluster of berries ʼ.

Pa. kuṇḍaka -- m. ʻ red powder of rice husks ʼ; Pk. kuṁḍaga -- m. ʻ chaff ʼ; N. kũṛo ʻ boiled grain given as fodder to buffaloes ʼ, kunāuro ʻ husk of lentils ʼ (for ending cf.kusāuro ʻ chaff of mustard ʼ); B. kũṛā ʻ rice dust ʼ; Or. kuṇḍā ʻ rice bran ʼ; M. kũḍā, kõ° m. ʻ bran ʼ; Si. kuḍu ʻ powder of paddy &c. ʼ

Addenda: kuṇḍaka -- in cmpd. kaṇa -- kuṇḍaka -- Arthaś.

2199 Te. kōḍiya, kōḍe young bull; adj. male (e.g. kōḍe dūḍa bull calf), young, youthful; kōḍekã̄ḍu a young man. Kol. (Haig) kōḍē bull. Nk. khoṛe male calf. Konḍakōḍi cow; kōṛe young bullock. Pe. kōḍi cow. Manḍ. kūḍi id. Kui kōḍi id., ox. Kuwi (F.) kōdi cow; (S.) kajja kōḍi bull; (Su. P.) kōḍi cow. DED(S) 1823.

2200 Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool; kuvaṭu branch of a tree; kōṭṭāṉ, kōṭṭuvāṉrock horned-owl (cf. 1657 Ta. kuṭiñai). Ko. ko·ṛ (obl. ko·ṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kwidir (obl. kwidi-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu.kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn. Ga. (Oll.) kōr (pl. kōrgul) id. Go. (Tr.) kōr (obl. kōt-, pl. kōhk) horn of cattle or wild animals, branch of a tree; (W. Ph. A. Ch.) kōr (pl. kōhk), (S.) kōr (pl. kōhku), (Ma.) kōr̥u (pl. kōẖku) horn; (M.) kohk branch (Voc. 980); (LuS.) kogoo a horn. Kui kōju (pl. kōska) horn, antler. Cf. 2049 Ta. koṭi.

खाण्डव [p= 339,1] N. of a forest in कुरु-क्षेत्र (sacred to इन्द्र and burnt by the god of fire aided by अर्जुन and कृष्ण MBh. Hariv. BhP. i , 15 , 8 Katha1s. )Ta1n2d2yaBr. xxv , 3 TA1r.

ఖాండవము (p. 0344) [ khāṇḍavamu ] khānḍavamu. [Skt.] n. The name of a grove sacred to Indra. ఇంద్రునియొక్క ఒకానొక వనము.

n crop (রবিখন্দ ). ̃ কার, খোন্দকার n. a producer of crops, a farmer; a (Mus lim) title of honour awarded to wealthy farmers.kara, khondakara n. a producer of crops, a farmer; a (Mus lim) title of honour awarded to wealthy farmers.

khōdd 3934 *khōdd ʻ dig ʼ. 2. *khōḍḍ -- . 3. *kōḍḍ -- . 4. *gōdd -- . 5. *gōḍḍ -- . 6. *guḍḍ -- . [Poss. conn. with khudáti ʻ thrusts (penis) into ʼ RV., prákhudati ʻ futuit ʼ AV.; cf. also *khōtr -- , *kōtr -- ]

1. P. khodṇā ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, khudṇā ʻ to be dug ʼ; Ku. khodṇo ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, N. khodnu, B. khodā, khudā, Or. khodibā, khud°; Bi. mag. khudnī ʻ a kind of spade ʼ; H. khodnā ʻ to dig, carve, search ʼ, khudnā ʻ to be dug ʼ; Marw. khodṇo ʻ to dig ʼ; G. khodvũ ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, M. khodṇẽ (also X khānayati q.v.). -- N. khodalnu ʻ to search for ʼ cf. *khuddati s.v. *khōjja -- ?

2. B. khõṛā ʻ to dig ʼ or < *khōṭayati s.v. *khuṭati.

3. B. koṛā, kõṛā ʻ to dig, pierce ʼ, Or. koṛibā ʻ to cut clods of earth with a spade, beat ʼ; Mth. koṛab ʻ to dig ʼ, H. koṛnā.

4. K. godu m. ʻ hole ʼ, g° karun ʻ to pierce ʼ; N. godnu ʻ to pierce ʼ; H. godnā ʻ to pierce, hoe ʼ, gudnā ʻ to be pierced ʼ; G. godɔ m. ʻ a push ʼ; M. godṇẽ ʻ to tattoo ʼ.

5. L. goḍaṇ ʻ to hoe ʼ, P. goḍṇā, goḍḍī f. ʻ hoeings ʼ; N. goṛnu ʻ to hoe, weed ʼ; H. goṛnā ʻ to hoe up, scrape ʼ, goṛhnā (X kāṛhnā?); G. goḍvũ ʻ to loosen earth round roots of a plant ʼ.

6. S. guḍ̠aṇu ʻ to pound, thrash ʼ; P. guḍḍṇā ʻ to beat, pelt, hoe, weed ʼ.

Addenda: *khōdd -- . 1. S.kcch. khodhṇū ʻ to dig ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (Wkc.) khódṇõ, J. khodṇu.

2. *khōḍḍ -- : WPah.kc. khoḍṇo ʻ to dig ʼ; -- kṭg. khoṛnõ id. see *khuṭati Add2.

1. P. khodṇā ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, khudṇā ʻ to be dug ʼ; Ku. khodṇo ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, N. khodnu, B. khodā, khudā, Or. khodibā, khud°; Bi. mag. khudnī ʻ a kind of spade ʼ; H. khodnā ʻ to dig, carve, search ʼ, khudnā ʻ to be dug ʼ; Marw. khodṇo ʻ to dig ʼ; G. khodvũ ʻ to dig, carve ʼ, M. khodṇẽ (also X khānayati q.v.). -- N. khodalnu ʻ to search for ʼ cf. *khuddati s.v. *khōjja -- ?

2. B. khõṛā ʻ to dig ʼ or < *khōṭayati s.v. *khuṭati.

3. B. koṛā, kõṛā ʻ to dig, pierce ʼ, Or. koṛibā ʻ to cut clods of earth with a spade, beat ʼ; Mth. koṛab ʻ to dig ʼ, H. koṛnā.

4. K. godu m. ʻ hole ʼ, g° karun ʻ to pierce ʼ; N. godnu ʻ to pierce ʼ; H. godnā ʻ to pierce, hoe ʼ, gudnā ʻ to be pierced ʼ; G. godɔ m. ʻ a push ʼ; M. godṇẽ ʻ to tattoo ʼ.

5. L. goḍaṇ ʻ to hoe ʼ, P. goḍṇā, goḍḍī f. ʻ hoeings ʼ; N. goṛnu ʻ to hoe, weed ʼ; H. goṛnā ʻ to hoe up, scrape ʼ, goṛhnā (X kāṛhnā?); G. goḍvũ ʻ to loosen earth round roots of a plant ʼ.

6. S. guḍ̠aṇu ʻ to pound, thrash ʼ; P. guḍḍṇā ʻ to beat, pelt, hoe, weed ʼ.

Addenda: *khōdd -- . 1. S.kcch. khodhṇū ʻ to dig ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (Wkc.) khódṇõ, J. khodṇu.

2. *khōḍḍ -- : WPah.kc. khoḍṇo ʻ to dig ʼ; -- kṭg. khoṛnõ id. see *khuṭati Add2.

Composite copper alloy anthropomorphic Meluhha hieroglyphs of Haryana and Sheorajpur: fish, markhor, crocodile, one-horned young bull

Oxford English Dictionary defines anthropomorphic: "a. treating the deity as anthropomorphous, or as having a human form and character; b. attributing a human personality to anything impersonal or irrational."

The copper anthropomorph of Haryana is comparable to and an elaboration of a copper anthropomorph of Sheorajpur, Uttar Pradesh. Both deploy Meluhha hieroglyphs using rebus-metonymy layered cipher of Indus writing.

The hieroglyhs of the anthropomorphs are a remarkable archaeological evidence attesting to the evidence of an ancient Samskritam text, Baudhāyana śrautasūtra.

Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44 which documents migrations of Āyu and Amavasu from a central region:

pran Ayuh pravavraja. tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. etad Ayavam pravrajam. pratyan amavasus. tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo ‘ratta ity. etad Amavasavam

Trans. Ayu went east, his is the Yamuna-Ganga region (Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha). Amavasu went west, his is Gandhara, Parsu and Araṭṭa.

Ayu went east from Kurukshetra to Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha. The migratory path of Meluhha artisand in the lineage of Ayu of the Rigvedic tradition, to Kasi-Videha certainly included the very ancient temple town of Sheorajpur of Dist. Etawah (Kanpur), Uttar Pradesh.

Haryana anthropormorph (in the Kurukshetra region on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati) deploys hieroglyphs of markhor (horns), crocodile and one-horned young bull together with an inscription text using Indus Script hieroglyphs. The Sheorajpur anthropomorph deploys hieroglyphs of markhor (horns) and fish. The astonishing continuity of archaeo-metallurgical tradition of Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization is evident from a temple in Sheorajpur on the banks of Sacred River Ganga. This temple dedicated to Siva has metalwork ceilings !!!

Both anthropomorph artefacts in copper alloy are metalwork catalogs of dhokara kamar 'cire perdue(lost-wax) metal casters'.

Hieroglyhph: eraka 'wing' Rebus: eraka, arka 'copper'.In 2003, Paul Yule wrote a remarkable article on metallic anthropomorphic figures derived from Magan/Makkan, i.e. from an Umm an-Nar period context in al-Aqir/Bahla' in the south-western piedmont of the western Hajjar chain. "These artefacts are compared with those from northern Indian in terms of their origin and/or dating. They are particularly interesting owing to a secure provenance in middle Oman...The anthropomorphic artefacts dealt with...are all the more interesting as documents of an ever-growing body of information on prehistoric international contact/influence bridging the void between south-eastern Arabia and South Asia...Gerd Weisgerber recounts that in winter of 1983/4...al-Aqir near Bahla' in the al-Zahirah Wilaya delivered prehistoric planoconvex 'bun' ingots and other metallic artefacts from the same find complex..."

In the following plate, Figs. 1 to 5 are anthropomorphs, with 'winged' attributes. The metal finds from the al-Aqir wall include ingots, figures, an axe blade, a hoe, and a cleaver (see fig. 1, 1-8), all in copper alloy.

Fig. 1: Prehistoric metallic artefacts from the Sultanate of Oman: 1-8 al-Aqir/Bahla'; 9 Ra's al-Jins 2, building vii, room 2, period 3 (DA 11961) "The cleaver no. 8 is unparalleled in the prehistory of the entire Near East. Its form resembles an iron coco-nut knife from a reportedly subrecent context in Gudevella (near Kharligarh, Dist. Balangir, Orissa) which the author examined some years ago in India...The dating of the figures, which command our immediate attention, depends on two strands of thought. First, the Umm an-Nar Period/Culture dating mentioned above, en-compasses a time-space from 2500 to 1800 BC. In any case, the presence of “bun“ ingots among the finds by nomeans contradicts a dating for the anthropomorphic figures toward the end of the second millennium BC. Since these are a product of a simple form of copper production, they existed with the beginning of smelting in Oman. The earliest dated examples predate this, i.e. the Umm an-NarPeriod. Thereafter, copper continues to be produced intothe medieval period. Anthropomorphic figures from the Ganges-Yamuna Doab which resemble significantly theal-Aqir artefacts (fig. 2,10-15) form a second line of evidence for the dating. To date, some 21 anthropomorphsfrom northern India have been published." (p. 539; cf. Yule, 1985, 128: Yule et al. 1989 (1992) 274: Yule et al 2002. More are known to exist, particularly from a large hoard deriving from Madarpur.)

Fig. 2: Anthropomorphic figures from the Indian Subcontinent. 10 type I, Saipai, Dist. Etawah, U.P.; 11 type I, Lothal, Dist. Ahmedabad,Guj.; 12 type I variant, Madarpur, Dist. Moradabad, U.P.; 13 type II, Sheorajpur, Dist. Kanpur, U.P.; 14 miscellaneous type, Fathgarh,Dist. Farrukhabad, U.P.; 15 miscellaneous type, Dist. Manbhum, Bihar.

The anthropomorph from Lothal/Gujarat (fig. 2,11), from a layer which its excavator dates to the 19 th century BCE. Lothal, phase 4 of period A, type 1. Some anthropomorphs were found stratified together with Ochre-Coloured Pottery, dated to ca. 2nd millennium BCE. Anthropomorph of Ra's al-Jins (Fig. 1,9) clearly reinforces the fact that South Asians travelled to and stayed at the site of Ra's al-Jins. "The excavators date the context from which the Ra’s al-Jins copper artefact derived to their period III, i.e. 2300-2200 BCE (Cleuziou & Tosi 1997, 57), which falls within thesame time as at least some of the copper ingots which are represented at al-Aqir, and for example also in contextfrom al-Maysar site M01...the Franco-Italian teamhas emphasized the presence of a settled Harappan-Peri-od population and lively trade with South Asia at Ra's al-Jins in coastal Arabia. (Cleuziou, S. & Tosi, M., 1997, Evidence for the use of aromatics in the early Bronze Age of Oman, in: A. Avanzini, ed., Profumi d'Arabia, Rome 57-81)."

"In the late third-early second millennium, given the presence of a textually documented 'Meluhha village' in Lagash (southern Mesopotamia), one cannot be too surprised that such colonies existed 'east of Eden' in south-eastern Arabia juxtaposed with South Asia. In any case, here we encounter yet again evidence for contact between the two regions -- a contact of greater intimacy and importance than for the other areas of the Gulf."(Paul Yule, 2003, Beyond the pale of near Eastern Archaeology: Anthropomorphic figures from al-Aqir near Bahla' In: Stöllner, T. (Hrsg.): Mensch und Bergbau Studies in Honour of Gerd Weisgerber on Occasion of his 65th Birthday. Bochum 2003, pp. 537-542).

See: Weisgerber, G., 1988, Oman: A bronze-producing centre during the 1st half of the 1st millennium BCE, in: J. Curtis, ed., Bronze-working centres of western Asia, c. 1000-539 BCE, London, 285-295.

With curved horns, the ’anthropomorph’ is a ligature of a mountain goat or markhor (makara) and a fish incised between the horns. Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. At Sheorajpur, three anthropomorphs in metal were found. (Sheorajpur, Dt. Kanpur. Three anthropomorphic figures of copper. AI, 7, 1951, pp. 20, 29).

One anthropomorph had fish hieroglyph incised on the chest of the copper object, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

A remarkable legacy of the civilization occurs in the use of ‘fish‘ sign on a copper anthropomorph found in a copper hoard. This is an apparent link of the ‘fish’ broadly with the profession of ‘metal-work’. The ‘fish’ sign is apparently related to the copper object which seems to depict a ‘fighting ram’ symbolized by its in-curving horns. The ‘fish’ sign may relate to a copper furnace. The underlying imagery defined by the style of the copper casting is the pair of curving horns of a fighting ram ligatured into the outspread legs (of a warrior).

The center-piece of the makara symbolism is that it is a big jhasa, big fish, but with ligatured components (alligator snout, elephant trunk, elephant legs and antelope face). Each of these components can be explained (alligator: manger; elephant trunk: sunda; elephant: ibha; antelope: ranku; rebus: mangar ‘smith’; sunda ‘furnace’; ib ‘iron’; ranku ‘tin’); thus the makara jhasa or the big composite fish is a complex of metallurgical repertoire.)

One nidhi was makara (syn. Kohl, antimony); the second was makara (or, jhasa, fish) [bed.a hako (ayo)(syn. bhed.a ‘furnace’; med. ‘iron’; ayas ‘metal’)]; the third was kharva (syn. karba, iron).

| Title / Object: | anthropomorphic sheorajpur |

|---|---|

| Fund context: | Saipai, Dist. Kanpur |

| Time of admission: | 1981 |

| Pool: | SAI South Asian Archaeology |

| Image ID: | 213 101 |

| Copyright: | Dr Paul Yule, Heidelberg |

| Photo credit: | Yule, Metalwork of the Bronze in India, Pl 23 348 (dwg) |

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)The extraordinary presence of a Lothal anthropomorph of the type found on the banks of River Ganga in Sheorajpur (Uttar Pradesh) makes it apposite to discuss the anthropomorph as a Meluhha hieroglyph, since Lothal is reportedly a mature site of the civilization which has produced nearly 7000 inscriptions (what may be called Meluhha epigraphs, almost all of which are relatable to the bronze age metalwork of India).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-snarling-iron-of.html

"Anthropomorphs occur in a variety of shapes and sizes (Plate A). The two basic types dominate, as defined by the proportions in combination with certain morphological features. All show processes suggestive of a human head, arms and legs. With one exception (no. 539) all are highly geometricising and flat. Fashioned from thick metal sheeting, these artifacts have stocky proportions and are patterned on both sides with elongated gouches or dents which usually are lengthwise oriented. Sometimes, however, the patterning is chevroned or cross-hatched. Significantly, the upper edge of the 'head' shows no thickening, as is the case of type H anthropomorphs. Examples have come to light at mid doab and a broken anthropomorph from distant Lothal as well. The only stratified example derives from Lothal, level IV. height range. 23.2-24.1cm; L/W: 0.65 - 0.88: 1; weight mean: 1260 gm." (Yule, Paul, pp.51-52).

"Conclusions..."To the west at Harappa Lothal in Gujarat the presence of a fragmentary import type I anthropomorph suggests contact with the doab." "(p.92)

Hieroglyphs: tagara ‘ram’ (Kannada) Rebus: damgar ‘merchant’ (Akk.) Rebus: tagara ‘tin’ (Kannada)

ṭhākur ʻblacksmithʼ: ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (cf. ḍhakkārī -- ), ʼ lex., ʻ title ʼ Rājat. [Dis- cussion with lit. by W. Wüst RM 3, 13 ff. Prob. orig. a tribal name EWA i 459, which Wüst considers nonAryan borrowing of śākvará -- : very doubtful]Pk. ṭhakkura -- m. ʻ Rajput, chief man of a village ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) takur ʻ barber ʼ (= ṭ° ← Ind.?), Sh. ṭhăkŭr m.; K. ṭhôkur m. ʻ idol ʼ ( ← Ind.?); S. ṭhakuru m. ʻ fakir, term of address between fathers of a husband and wife ʼ; P. ṭhākar m. ʻ landholder ʼ, ludh. ṭhaukar m. ʻ lord ʼ; Ku. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, title of a Rajput ʼ; N. ṭhākur ʻ term of address from slave to master ʼ (f. ṭhakurāni), ṭhakuri ʻ a clan of Chetris ʼ (f. ṭhakurni); A. ṭhākur ʻ a Brahman ʼ, ṭhākurānī ʻ goddess ʼ; B. ṭhākurāni, ṭhākrān, °run ʻ honoured lady, goddess ʼ; Or. ṭhākura ʻ term of address to a Brahman, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāṇī ʻ goddess ʼ; Bi. ṭhākur ʻ barber ʼ; Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh.ṭhākur ʻ lord, master ʼ; H. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, landlord, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāin, ṭhā̆kurānī f. ʻ mistress, goddess ʼ; G. ṭhākor, °kar m. ʻ member of a clan of Rajputs ʼ,ṭhakrāṇī f. ʻ his wife ʼ, ṭhākor ʻ god, idol ʼ; M. ṭhākur m. ʻ jungle tribe in North Konkan, family priest, god, idol ʼ; Si. mald. "tacourou"ʻ title added to names of noblemen ʼ (HJ 915) prob. ← Ind.

"Conclusions..."To the west at Harappa Lothal in Gujarat the presence of a fragmentary import type I anthropomorph suggests contact with the doab." "(p.92)

The Sheorajpur anthropomorph (348 on Plate A) has a 'fish' hieroglyph incised on the chest

Hieroglyphs: tagara ‘ram’ (Kannada) Rebus: damgar ‘merchant’ (Akk.) Rebus: tagara ‘tin’ (Kannada)

Ta. takar sheep, ram, goat, male of certain other animals (yāḷi, elephant, shark). பொருநகர் தாக்கற்குப் பேருந் தகைத்து (குறள், 486).Ma. takaran huge, powerful as a man, bear, etc. Ka. tagar, ṭagaru, ṭagara, ṭegaru ram. Tu. tagaru, ṭagarů id. Te. tagaramu, tagaru id. / Cf. Mar. tagar id. (DEDR 3000). Rebus 1:tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) takaram tin, white lead, metal sheet, coated with tin (Ta.); tin, tinned iron plate (Ma.); tagarm tin (Ko.); tagara, tamara, tavara id. (Ka.) tamaru, tamara, tavara id. (Ta.): tagaramu, tamaramu, tavaramu id. (Te.); ṭagromi tin metal, alloy (Kuwi); tamara id. (Skt.)(DEDR 3001). trapu tin (AV.); tipu (Pali); tau, taua lead (Pkt.); tū̃ tin (P.); ṭau zinc, pewter (Or.); tarūaum lead (OG.);tarvũ (G.); tumba lead (Si.)(CDIAL 5992). Rebus 2: damgar ‘merchant’.

Addenda: ṭhakkura -- : Garh. ṭhākur ʻ master ʼ; A. ṭhākur also ʻ idol ʼ

Hieroglyphs, allographs: ram, tabernae montana coronaria flower: तगर [ tagara ] f A flowering shrub, Tabernæ montana coronaria. 2 n C The flower of it. 3 m P A ram. (Marathi)

*tagga ʻ mud ʼ. [Cf. Bur. t*lg*l ỵ ʻ mud ʼ] Kho. (Lor.) toq ʻ mud, quagmire ʼ; Sh. tăgāˊ ʻ mud ʼ; K. tagöri m. ʻ a man who makes mud or plaster ʼ; Ku. tāgaṛ ʻ mortar ʼ; B. tāgāṛ ʻ mortar, pit in which it is prepared ʼ.(CDIAL 5626). (Note: making of mud or plaster is a key step in dhokra kamar's work of cire perdue (lost-wax) casting.)

Hieroglyphs, allographs: ram, tabernae montana coronaria flower: तगर [ tagara ] f A flowering shrub, Tabernæ montana coronaria. 2 n C The flower of it. 3 m P A ram. (Marathi)

*tagga ʻ mud ʼ. [Cf. Bur. t

krəm backʼ(Kho.) karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali)

It appears that the inscription is composed of Indus Script hieroglyphs and no Brahmi letters can be discerned. Hopefully, Prof. Naman Ahuja's response to my request will provide for a transcript with sharper visibility.

According to the curaorf, Naman Ahuja, the inscription in Brahmi reads “King/Ki Ma Jhi [name of king]/ Sha Da Ya [form of god]” and according to the curator, “looks unmistakably like the Hindu god Varaha”. The Uttar Pradesh archaeological department has accepted this as an antique piece and dates it to the second to the first millennium BCE.

The hieroglyphs of the inscription include the following, possible metalwork catalog:

Hieroglyph: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

.jpg)

Nahal Mishmar hoard also had a copper alloy U-shaped vessel comparable in shape to the one shown on Meluhha standard as a crucible or portable furnace. The zig-zag shaped decoration on the copper vessel is comparable to the zig-zag shape shown on the 'gimlet' ligature on Meluhha standard (Mohenjo-dao seal m008). The zig-zag pattern shows the circular motion of the lathe --

Nahal Mishmar hoard also had a copper alloy U-shaped vessel comparable in shape to the one shown on Meluhha standard as a crucible or portable furnace. The zig-zag shaped decoration on the copper vessel is comparable to the zig-zag shape shown on the 'gimlet' ligature on Meluhha standard (Mohenjo-dao seal m008). The zig-zag pattern shows the circular motion of the lathe --

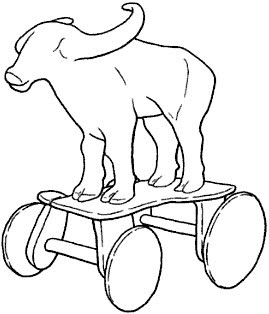

Harappa.

Harappa.

Buffalo. Mohenjo-daro.

Buffalo. Mohenjo-daro.

Text 1330

Text 1330