Mirror:http://tinyurl.com/zt6em75

Thanks to Vipin Kumar who notes the occurrence of the expression

अष्टाश्रि ashtAshri in 3rd kanda of Shatapatha brahmana also. Consequently, his insight is that an octagonal yupa signifies any somayaga. Vajapeya is one of seven somayagas which constitute somasamsthA. See: http://bharatkalyan97.

The evidence for the performance of a somayaga in Binjor and Kalibangan dated to ca. 2500 BCE in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization is a stunning evidence of the Vedic yajna tradition. This tradition continues into the historical periods evidenced by 19 yupa inscriptions in regions such as Rajasthan and East Borneo.

It will thus be appropriate to refer to the octagonal yupa in the Binjor agnikuNDa as a signifier of a somayaga, perhaps a particular type of somayaga which was called Vājapeya Soma samsthA.

In most of the 19 yupa inscriptions, the yaga is recorded to have gone on for several days, hence may be called अहीन Soma yoga (or Soma samsthA). such a somayaga could have been a Vājapeya.

अहीन [p= 125,3] m. (fr. /अहन् Pa1n2. 6-4 , 145) "lasting several days", a sacrifice lasting several days AitBr. A1s3vS3r. &c; mfn. unimpaired , whole , entire , full S3Br. AitBr. &c.

Somayaga or soma samsthA are seven. “Agnishtoma is considered to be a prakriti soma yajna (A template based on which other six are done --Atyagnistoma, Aptoryama, Atirātra ,uktha, shodasi, Vājapeya). The Vājapeyais the highest soma yajna. The performer of the Vajapeya has to be led into the country by the king himself and anna abhishekam has to be performed by the king for the performer of Vājapeya. Then the person who has performed this is given the title Vājapeyaji. Generally based on number of days performed, soma sacrifices are split into 1. Ekaha (one day) 2. Ahina (2-12 days) and 3. Satra (12 days till one year). The agnishtoma is an example of a 1 day sacrifice. The Vajapaya is an example for Ahina and the Gavamayana is an example for a satra. Specifically it is a samvatsara satra meaning it lasts for one year. The entire 7th kanda of the Taittriya samhita deals with satra type sacrifices.”

A hieroglyph hypertext on Kalibangan terracotta cake in a yajna kuNDA is a person holding a tiger tied to a rope. This hieroglyph-multiplex has been deciphered as related to metalwork.

Hypertexts signifying a tiger or zebu tied by a rope to a post are signified on some examples from Indus Script Corpora.

Pl. XXII B. Terracotta cake with incised figures on obverse and reverse, Harappan. On one side is a human figure wearing a head-dress having two horns and a plant in the centre; on the other side is an animal-headed human figure with another animal figure, the latter being dragged by the former.

Decipherment of hieroglyphs on the Kalibangan terracotta cake:

bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

koD 'horn' rebus: koD 'workshop'

kola 'tiger' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith', kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

The tiger is being pulled to be tied to a post, pillar.

Hieroglyph: Ka. kunda a pillar of bricks, etc. Tu. kunda pillar, post. Te. kunda id. Malt. kunda block, log. ? Cf. Ta. kantu pillar, post. (DEDR 1723) Rebus: (agni)kuNDA 'fire-altar, vedi'.

Note the Isapur yupa which show ropes in the middle and on the top to tie an animal as shown on the Kaibangan terracotta cake. In the case of the Kalibangan terracotta cake, the hieroglyph shows a kola, 'tiger' tied to the rope. The rebus reading is kol 'working in iron'. The work in iron is signified by the post, yupa: meḍ(h), 'post, stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron', med 'copper' (Slavic).

Thus, the terracotta cake inscription signifies a iron workshop smelter/furnace and smithy.

Kulli. Plate. Two tigers tied to a meshed axle. Stars. Fish.

Decipherment:

dula'pair' rebus: dul'cast metal'

kola'tiger' rebus: kolhe'smelter' kol 'working in iron'kolle'blacksmith'. http://www.harappa.com/figurines/index.html kola 'tiger' kola 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.;.P.U.) konimi blacksmith

(Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge(DEDR 2133).

मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] the polar star (Phonetic determinant); meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻpost, forked stakeʼ rebus: meD'iron' (Ho.); med'copper'

kāṇḍa 'water' rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware'.

Thus, the inscription on the Kulli plate signifies iron smelting, cast iron (metal) implements.

Zebu and leaves. In front of the standard device and the stylized tree of 9 leaves, are the black buck antelopes. Black paint on red ware of Kulli style. Mehi. Second-half of 3rd millennium BCE. [After G.L. Possehl, 1986, Kulli: an exploration of an ancient civilization in South Asia, Centers of Civilization, I, Durham, NC: 46, fig. 18 (Mehi II.4.5), based on Stein 1931: pl. 30.

Zebu and leaves. In front of the standard device and the stylized tree of 9 leaves, are the black buck antelopes. Black paint on red ware of Kulli style. Mehi. Second-half of 3rd millennium BCE. [After G.L. Possehl, 1986, Kulli: an exploration of an ancient civilization in South Asia, Centers of Civilization, I, Durham, NC: 46, fig. 18 (Mehi II.4.5), based on Stein 1931: pl. 30. Decipherment:

adar ḍangra ‘zebu’ (Santali); Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.);ḍhan:gar

‘blacksmith’ (WPah.) ayir = iron dust, any ore (Ma.) aduru = gan.iyinda

tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to

melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretation

of the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native

metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron.

tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to

melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretation

of the Amarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330) DEDR 192 Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native

metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron.

Hieroglyph: lo = nine (Santali); no = nine (B.) on-patu = nine (Ta.)

[Note the count of nine fig leaves on m0296] Rebus: loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata (Santali.lex.)(Phonetic determinant)

loa = a species of fig tree, ficus glomerata, the fruit of ficus glomerata

(Santali) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali); lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali.lex.)

The hypertext signifies iron or copper metal work, with particular reference to magnetite ore: lo 'iron or copper' PLUS poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite (ferrite ore)' PLUS meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floorʼ rebus: meD 'iron', med 'copper'.

(Santali) Rebus: lo ‘iron’ (Assamese, Bengali); loa ‘iron’ (Gypsy) lauha = made of copper or iron (Gr.S'r.); metal, iron (Skt.); lo_haka_ra = coppersmith, ironsmith (Pali); lo_ha_ra = blacksmith (Pt.); lohal.a (Or.); lo_ha = metal, esp. copper or bronze (Pali); copper (VS.); loho, lo_ = metal, ore, iron (Si.) loha lut.i = iron utensils and implements (Santali.lex.)

The hypertext signifies iron or copper metal work, with particular reference to magnetite ore: lo 'iron or copper' PLUS poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite (ferrite ore)' PLUS meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floorʼ rebus: meD 'iron', med 'copper'.

Shahdad plates signifying zebu and tiger as catalogues of metalwork:

Shahdad.Plates 5 & 6. Chlorite incised vessel Grave No. 001.

Shahdad.Plates 5 & 6. Chlorite incised vessel Grave No. 001.Object No. 0004 (p.26) Hakemi, Ali, 1997, Shahdad, archaeological excavations of a bronze age center in Iran, Reports and Memoirs, Vol. XXVII, IsMEO, Rome. 766 pp.

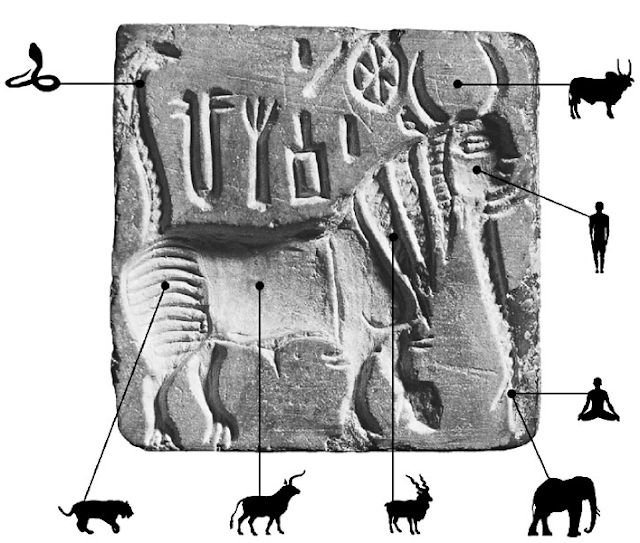

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032, glyphs used are: Zebu (bos taurus indicus), fish, four-strokes (allograph: arrow).ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) + kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) gaṆḌa, ‘four’ (Santali); Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’, ‘furnace’), arrow read rebus in mleccha (Meluhhan) as a reference to a guild of artisans working with ayaskāṇḍa ‘excellent quantity of iron’ (Pāṇini) is consistent with the primacy of economic activities which resulted in the invention of a writing system, now referred to as Indus Writing.

काण्डः kāṇḍḥ ण्डम् ṇḍam The portion of a plant from one knot to another. काण्डात्काण्ड- त्प्ररोहन्ती Mahānār.4.3. A stem, stock, branch; लीलोत्खातमृणाल काण्डकवलच्छेदे U.3.16; Amaru.95; Ms. 1.46,48, Māl.3.34. కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá -- : (b) ʻ water -- channel ʼ: Paš. kaṭāˊ ʻ irrigation channel ʼ, Shum. xãṭṭä. (CDIAL 14349).

A Munda gloss for fish is 'aya'. Read rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Vedic). The script inscriptions indicate a set of modifiers or ligatures to the hieroglyph indicating that the metal, aya, was worked on during the early Bronze Age metallurgical processes -- to produce aya ingots, aya metalware,aya hard alloys. Fish hieroglyph in its vivid orthographic form is shown in a Susa pot which contained metalware -- weapons and vessels.  Context for use of ‘fish’ glyph. This photograph of a fish and the ‘fish’ glyph on Susa pot are comparable to the ‘fish’ glyph on Indus inscriptions. Read on the arguments at: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2011/11/decoding-fish-and-ligatured-fish-glyphs.html The modifiers to the 'fish' hieroglyph which commonly occur together are: slanted stroke, notch, fins, lid-of-pot ligatured as superfix: Table from: The Indus Script: A Positional-statistical Approach By Michael Korvink, 2007, Gilund Press. Mahadevan notes (Para 6.5 opcit.) that ‘a unique feature of the FISH signs is their tendency to form clusters, often as pairs, and rarely as triplets also. This pattern has fascinated and baffled scholars from the days of Hunter posing problems in interpretation.’ One way to resolve the problem is to interpret the glyptic elements creating ligatured fish signs and read the glyptic elements rebus to define the semantics of the message of an inscription. karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda) Rebus:. kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati) The 'parenthesis' modifier is a circumfix for both 'fish' and 'duck' hieroglyphs, the semantics of () two parenthetical modifiers are: kuṭilá— ‘bent, crooked’ KātyŚr., °aka— Pañcat., n. ‘a partic. plant’ [√kuṭ 1] Pa. kuṭila— ‘bent’, n. ‘bend’; Pk. kuḍila— ‘crooked’, °illa— ‘humpbacked’, °illaya— ‘bent’DEDR 2054 (a) Ta. koṭu curved, bent, crooked; koṭumai crookedness, obliquity; koṭukki hooked bar for fastening doors, clasp of an ornament. A pair of curved lines: dol ‘likeness, picture, form’ [e.g., two tigers, two bulls, sign-pair.] Kashmiri. dula दुल । युग्मम् m. a pair, a couple, esp. of two similar things (Rām. 966). Rebus: dul meṛeḍ cast iron (Mundari. Santali) dul ‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali) pasra meṛed, pasāra meṛed = syn. of koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari.) Thus, dul kuṭila ‘cast bronze’. The parenthetically ligatured fish+duck hieroglyphs thus read rebus: dul kuṭila ayas karaḍā 'cast bronze ayasor cast alloy metal with ayas as component to create karaḍā ''hard alloy with ayas'. Modifier hieroglyph: 'snout' Hieroglyph: WPah.kṭg. ṭōṭ ʻ mouth ʼ.WPah.kṭg. thótti f., thótthəṛ m. ʻ snout, mouth ʼ, A. ṭhõt(phonet. thõt) (CDIAL 5853). Semantics, Rebus: tutthá n. (m. lex.), tutthaka -- n. ʻ blue vitriol (used as an eye ointment) ʼ Suśr., tūtaka -- lex. 2. *thōttha -- 4. 3. *tūtta -- . 4. *tōtta -- 2. [Prob. ← Drav. T. Burrow BSOAS xii 381; cf. dhūrta -- 2 n. ʻ iron filings ʼ lex.]1. N. tutho ʻ blue vitriol or sulphate of copper ʼ, B. tuth.2. K. thŏth, dat. °thas m., P. thothā m.3. S.tūtio m., A. tutiyā, B. tũte, Or. tutiā, H. tūtā, tūtiyā m., M. tutiyā m.4. M. totā m.(CDIAL 5855) Ka. tukku rust of iron; tutta, tuttu, tutte blue vitriol. Tu. tukků rust; mair(ů)suttu, (Eng.-Tu. Dict.) mairůtuttu blue vitriol. Te. t(r)uppu rust; (SAN) trukku id., verdigris. / Cf. Skt. tuttha- blue vitriol (DEDR 3343). Fish + corner, aya koṇḍa, ‘metal turned or forged’ Fish, aya ‘metal’ Fish + scales, aya ã̄s (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. Vikalpa: badhoṛ ‘a species of fish with many bones’ (Santali) Rebus: baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali) Fish + splinter, aya aduru ‘smelted native metal’ Fish + sloping stroke, aya ḍhāḷ ‘metal ingot’ Fish + arrow or allograph, Fish + circumscribed four short strokes This indication of the occurrence, together, of two or more 'fish' hieroglyphs with modifiers is an assurance that the modifiers ar semantic indicators of how aya 'metal' is worked on by the artisans. ayakāṇḍa ‘’large quantity of stone (ore) metal’ or aya kaṇḍa, ‘metal fire-altar’. ayo, hako 'fish'; ãs = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya ‘metal, iron’ (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) Santali lexeme, hako ‘fish’ is concordant with a proto-Indic form which can be identified as ayo in many glosses, Munda, Sora glosses in particular, of the Indian linguistic area. beḍa hako (ayo) ‘fish’ (Santali); beḍa ‘either of the sides of a hearth’ (G.) Munda: So. ayo `fish'. Go. ayu `fish'. Go <ayu> (Z), <ayu?u> (Z),, <ayu?> (A) {N} ``^fish''. Kh. kaDOG `fish'. Sa. Hako `fish'. Mu. hai (H) ~ haku(N) ~ haikO(M) `fish'. Ho haku `fish'. Bj. hai `fish'. Bh.haku `fish'. KW haiku ~ hakO |Analyzed hai-kO, ha-kO (RDM). Ku. Kaku`fish'.@(V064,M106) Mu. ha-i, haku `fish' (HJP). @(V341) ayu>(Z), <ayu?u> (Z) <ayu?>(A) {N} ``^fish''. #1370. <yO>\\<AyO>(L) {N} ``^fish''. #3612. <kukkulEyO>,,<kukkuli-yO>(LMD) {N} ``prawn''. !Serango dialect. #32612. <sArjAjyO>,,<sArjAj>(D) {N} ``prawn''. #32622. <magur-yO>(ZL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. *Or.<>. #32632. <ur+GOl-Da-yO>(LL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. #32642.<bal.bal-yO>(DL) {N} ``smoked fish''. #15163. Vikalpa: Munda: <aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.#10171. So<aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''. Indian mackerel Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma.ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach (DEDR 191) aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). Ta. ayil javelin, lance, surgical knife, lancet.Ma. ayil javelin, lance; ayiri surgical knife, lancet. (DEDR 193). aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Ta.); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Ma.) Kur. adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Malt. adru broken grain (DEDR 134). Ma. aśu thin, slender;ayir, ayiram iron dust.Ta. ayir subtlety, fineness, fine sand, candied sugar; ? atar fine sand, dust. அய.ர³ ayir, n. 1. Subtlety, fineness; நணசம. (த_வ_.) 2. [M. ayir.] Fine sand; நணமணல. (மலசலப. 92.) ayiram, n. Candied sugar; ayil, n. cf. ayas. 1. Iron; 2. Surgical knife, lancet; Javelin, lance; ayilavaṉ, Skanda, as bearing a javelin (DEDR 341).Tu. gadarů a lump (DEDR 1196) kadara— m. ‘iron goad for guiding an elephant’ lex. (CDIAL 2711). अयोगूः A blacksmith; Vāj.3.5. अयस् a. [इ-गतौ-असुन्] Going, moving; nimble. n. (-यः) 1 Iron (एति चलति अयस्कान्तसंनिकर्षं इति तथात्वम्; नायसोल्लिख्यते रत्नम् Śukra 4.169. अभितप्तमयो$पि मार्दवं भजते कैव कथा शरीरिषु R.8.43. -2 Steel. -3 Gold. -4 A metal in general. ayaskāṇḍa 1 an iron-arrow. -2 excellent iron. -3 a large quantity of iron. -क_नत_(अयसक_नत_) 1 'beloved of iron', a magnet, load-stone; 2 a precious stone; ˚मजण_ a loadstone; ayaskāra 1 an iron-smith, blacksmith (Skt.Apte) ayas-kāntamu. [Skt.] n. The load-stone, a magnet. ayaskāruḍu. n. A black smith, one who works in iron. ayassu. n. ayō-mayamu. [Skt.] adj. made of iron (Te.) áyas— n. ‘metal, iron’ RV. Pa. ayō nom. sg. n. and m., aya— n. ‘iron’, Pk. aya— n., Si. ya. AYAŚCŪRṆA—, AYASKĀṆḌA—, *AYASKŪṬA—. Addenda: áyas—: Md. da ‘iron’, dafat ‘piece of iron’. ayaskāṇḍa— m.n. ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ Pāṇ. gaṇ. viii.3.48 [ÁYAS—, KAA ́ṆḌA—]Si.yakaḍa ‘iron’.*ayaskūṭa— ‘iron hammer’. [ÁYAS—, KUU ́ṬA—1] Pa. ayōkūṭa—, ayak m.; Si. yakuḷa‘sledge —hammer’, yavuḷa (< ayōkūṭa) (CDIAL 590, 591, 592). cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa; Old Germ. e7r , iron ;Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen. Note on (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. An uncertain meaning of soma in Rigveda though the entire samhita holds the processing of soma in a nutshell, can be resolved in the context of modifers to 'fish' hieroglyph to denote 'fins or scales'. The vedic texts provide an intimation treating amśu as a synonym of soma. George Pinault has found a cognate word in Tocharian, ancu which means 'iron'. I have argued in my book, Indian alchemy, soma in the Veda, that Soma was an allegory, 'electrum' (gold-silver compound). See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/10/itihasa-and-eagle-narratives.html for Pinault's views on ancu, amśu concordance. The link with the Tocharian word is intriguing because Soma was supposed to come from Mt. Mujavant. A cognate of Mujavant is Mustagh Ata of the Himalayan ranges in Kyrgystan. Is it possible that the ancu of Tocharian from this mountain was indeed Soma? The referemces to Anzu in ancient Mesopotamian tradition parallels the legends of śyena 'falcon' which is used in Vedic tradition of Soma yajña attested archaeologically in Uttarakhand with a śyenaciti, 'falcon-shaped' fire-altar. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/11/syena-orthography.html śyena, orthography, Sasanian iconography. Continued use of Indus Script hieroglyphs. I suggest that ayas of bronze age created a revolutionary transformation in the lives of people of these bronze age times. |

Maybe, Tocharian ancu had the same meaning as Rigvedic gloss, amśu. If so, ancu might have denoted electrum, 'gold-silver compound' which was subjected to reduction, by oxidation of impurities, by incessant firing for five days and nights to create the shining wealth of gold. The old Egyptian gloss for electrum wasassem, cognate soma.

"The earliest animal figurines from Harappa are Early Harappan (Ravi Phase, Period 1 and Kot Diji Phase, Period 2) zebu figurines. They are typically very small with joined legs and stylized humps. A few of these zebu figurines have holes through the humps that may have allowed them to be worn as amulets on a cord or a string. One Early Harappan zebu figurine was found with the remains of a copper alloy ring still in this hole. Approximate dimensions (W x H (L) x D) of the uppermost figurine: 1.2 x 3.3 x 2.8 cm." https://www.harappa.com/figurines/32.html

Chanhu-darho in Sindh in 1935-36. Steatite, Height: 3.20 Width: 3.20 cm (h:1 1/4 w:1 1/4 inches). Courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art, J. H. Wade Fund 1973.160.

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite'

kaNDa 'square/divisions' rebus: kANDa 'implements' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron or copper' Thus, metal implements.

Parenthesis may be orthographically a split rhombus, shaped like an ingot: Hieroglyph: mūhā 'ingot' rebus: mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen me~ṛhe~t mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) PLUS karaNDava 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' thus, hard alloy ingot.

khareḍo = a currycomb (Gujarati) खरारा [ kharārā ] m ( H) A currycomb. 2 Currying a horse. (Marathi) Rebus: 1. करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) 2. kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati)

The hypertext message is thus a metalwork catalogue of a metals turner working with iron, hard alloy ingots and magnetite (ferrite ore).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/01/octagonal-yupo-bhavati-satapatha.html poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite'

kaNDa 'square/divisions' rebus: kANDa 'implements' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron or copper' Thus, metal implements.

Parenthesis may be orthographically a split rhombus, shaped like an ingot: Hieroglyph: mūhā 'ingot' rebus: mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; kolhe tehen me~ṛhe~t mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) PLUS karaNDava 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' thus, hard alloy ingot.

khareḍo = a currycomb (Gujarati) खरारा [ kharārā ] m ( H) A currycomb. 2 Currying a horse. (Marathi) Rebus: 1. करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) 2. kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati)

The hypertext message is thus a metalwork catalogue of a metals turner working with iron, hard alloy ingots and magnetite (ferrite ore).

Decipherment of Sibri cylinder seal:

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ore'. Thus magnetite (iron) metal tools/implements.

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.karNIka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'.

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.karNIka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'.

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/p3n28lf

That zebu, bos indicus, is an exclusive legacy of South Asia is proven by genetic studies.

Nausharo: céramique de la période I (c. 2500 BCE) cf. Catherine Jarrige![]()

After the domestication of the zebu, bos indicus, deployment of the hierolyph of zebu on Indus Script Corpora is a significant advance in archaeometallurgy documentation.

The writing system depicting a hieroglyph multiplex of a zebu tied to a post with a bird perched on top is based on the rebus rendering of the Prakritam glosses: Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' Rebus: magnetite, citizen. baTa 'quail' Rebus: baTha 'furnace'. The messaging on Nausharo pots of a magnetite furnace for metalwork continues on seals and tablets including copper plates as metalwork catalogues.

The Prakritam gloss पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' as hieroglyph is read rebus: pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide'; poliya 'citizen, gatekeeper of town quarter'.

Zebu also signifies a native metal blacksmith: another gloss for zebu: ad.ar d.an:gra (Santali); rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) d.han:gar ‘blacksmith’ (WPah.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretation of theAmarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330). Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiramany ore. Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron. (DEDR 192). ayas 'metal' (Rigveda); aya 'iron' (Gujarati) Note: karba 'iron' is signified by hieroglyphs: karibha 'trunk of elephant' (Pali); ibha'elephant' (Samsritam). Thus, ajirda karba (Tulu) = aduru (aya) karba 'native metal iron' in semantic expansion of Prakritam in tune with archaeometallurgy advances in smelting, alloying and cire perduemetalcastings.

On a hieroglyph multiplex (hypertext), both zebu and elephant are signified by hieroglyph component: horn of zebu, trunk of elephant (together with other hieroglyph components such as tiger, snake, bovine, scarf, pannier):

![m0301 Mohenjodaro seal shows a comparable 'composite animal' glyphic ...]() m0301 Mohenjo-daro

m0301 Mohenjo-daro

Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. பொலியெருது poli-y-erutu , n. < பொலி- +. 1. Bull kept for covering; பசுக்களைச் சினையாக்குதற் பொருட்டு வளர்க்கப்படும் காளை. (பிங்.) கொடிய பொலியெருதை யிருமூக்கிலும் கயி றொன்று கோத்து (அறப். சத. 42). 2. The leading ox in treading out grain on a threshing-floor; களத்துப் பிணையல்மாடுகளில் முதற்செல்லுங் கடா. (W .) பொலி முறைநாகு poli-muṟai-nāku, n. < பொலி + முறை +. Heifer fit for covering; பொலியக்கூடிய பக்குவமுள்ள கிடாரி. (S. I. I . iv, 102.)

Rebus 1: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4'.

Rebus 2: pol m. ʻgate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate': Ka. por̤al town, city. Te. prōlu, (inscr.) pr̤ōl(u) city. ? (DEDR 4555) पोवळ or पोंवळ [ pōvaḷa or pōṃvaḷa ] f पोवळी or पोंवळी f The court-wall of a temple. (Marathi) *pratōlika ʻ gatekeeper ʼ. [pratōlī -- ] H. pauliyā, pol°, pauriyā m. ʻ gatekeeper ʼ, G. poḷiyɔ m.(CDIAL 8632) pratōlī f. ʻ gate of town or fort, main street ʼ MBh. [Cf. tōlikā -- . -- Perh. conn. with tōraṇa -- EWA ii 361, less likely with *ṭōla -- ] Pk. paōlī -- f. ʻ city gate, main street ʼ; WPah. (Joshi) prauḷ m., °ḷi f., pauḷ m., °ḷi f. ʻ gateway of a chief ʼ, proḷ ʻ village ward ʼ; H. paul, pol m. ʻ gate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate ʼ, paulī f. ʻ gate ʼ; OG. poli f. ʻ door ʼ; G. poḷi f. ʻ street ʼ; M. pauḷ, poḷ f. ʻ wall of loose stones ʼ. -- Forms with -- r -- poss. < *pradura -- : OAw. paüri ʻ gatepost ʼ; H. paur, °rī, pãwar, °rī f. ʻ gate, door ʼ.WPah.poet. prɔ̈̄ḷ m., prɔḷo m., prɔḷe f. ʻ gate of palace or temple ʼ.(CDIAL 8633) Porin (adj.) [fr. pora=Epic Sk. paura citizen, see pura. Semantically cp. urbane>urbanus>urbs; polite= poli/ths>po/lis. For pop. etym. see DA i.73 & 282] belonging to a citizen, i. e. citizenlike, urbane, polite, usually in phrase porī vācā polite speech D i.4, 114; S i.189; ii.280=A ii.51; A iii.114; Pug 57; Dhs 1344; DA i.75, 282; DhsA 397. Cp. BSk. paurī vācā MVastu iii.322. Porisa2 (nt.) [abstr. fr. purisa, *pauruṣyaŋ, cp. porisiya and poroseyya] 1. business, doing of a man (or servant, cp. purisa 2), service, occupation; human doing, activity M i.85 (rāja˚); Vv 6311 (=purisa -- kicca VvA 263); Pv iv.324 (uṭṭhāna˚=purisa -- viriya, purisa -- kāra PvA 252). -- 2. height of a man M. i.74, 187, 365.(Pali) పౌరము [ pauramu ] pauramu. [Skt. from పుర.] adj. Belonging to a city or town (పురము.) పౌరసతులు the ladies of the place: citizens' wives. పౌరలోకము paura-lōkamu. n. The townsfolk, a body of citizens. పౌరుడు pauruḍu. n. A citizen. పౌరులు citizens, townsfolk.(Telugu)

वृषः 1 A bull; असंपदस्तस्य वृषेण गच्छतः Ku.5.8; Me.54; R.2.35; Ms.9.123. -2 The sign Taurus of the zodiac. -3 The chief or best of a class, the best of its kind; (often at the end of comp.); मुनिवृषः, कपिवृषः &c. -उत्सर्गः setting free a bull on the occasion of a funeral rite, or as a religious act generally; एकादशाहे प्रेतस्य यस्य चोत्सृज्यते वृषः । प्रेतलोकं परित्यज्य स्वर्गलोकं च गच्छति (Samskritam. Apte)

"The letting loose of a bull (vRshotsarga) stamped with Siva's trident -- in cities like Benares and Gaya is fraught with the highest merit. This setting free of a bull to roam about at will often takes place at zrAddhas." (Monier Monier-Williams, 1891, Brahmanism and Hinduism: or religious thought and life in Asia, Macmillan, p.319). In Hindu tradition, GRhyasUtra prescribe procedures for vRshotsarga.

"It is note-worthy that the details of the ceremony of setting a bull at liberty viz. the 'Vrshotsarga' in the Grhya-Sutras viz. S & P, in which it is described are almost identical (mutual borrowing or a common source are possibilities). On the Karttika full-moon day or on the day of the Asvayuja month falling under the Nakshtra RevatI, the fire is made to blaze in the midst of cows and Ajya oblations are sacrificed with ap propriate Mantras. Then he sacrifices from the Sthalipaka be longing to Pushan with an invocation to Pushan. Then he selects a bull of one, two or three colours or a red bull or one that leads the herd or is loved by the herd, perfect in all limbs and the finest in the herd, mumuring the Rudra-hymns. Then that bull is adorned, as also four of the finest young cows of the herd and then he says "This young bull, I give you as your husband; sporting with him, your lover, walk about etc." When the bull is in the midst of the cows, he recites over them the Rig-Verses X, 169. With the milk of all those cows he should cook milk-rice and feed the Brahmins with it. In the opinion of some (P) an animal is sacrificed in this rite, in which case the ritual is the same as that of the *sula-gava*." http://dli.gov.in/rawdataupload/upload/0113/986/RTF/00000141.rtf

Hieroglyph: eagle పోలడు [ pōlaḍu ] , పోలిగాడు or దూడలపోలడు pōlaḍu. [Tel.] n. An eagle. పసులపోలిగాడు the bird called the Black Drongo. Dicrurus ater. (F.B.I.)(Telugu)

Rebus: पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'magnetite', ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4 (Asuri)

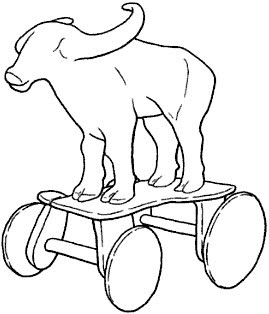

Rebus: cattle festival: पोळा [ pōḷā ] m (पोळ ) A festive day for cattle,--the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद . Bullocks are exempted from labor; variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship. "Pola is a bull-worshipping festival celebrated by farmers mainly in the Indian state of Maharashtra (especially among the Kunbis). On the day of Pola, the farmers decorate and worship their bulls. Pola falls on the day of the Pithori Amavasya (the new moon day) in the month of Shravana (usually in August)." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pola_(festival) Festival held on the day after Sankranti ( = kANum) is called pōlāla paNDaga (Telugu).![]() Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

Some artifacts of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization point to the possibility that the celebration of pola cattle festival may be traced to the cultural practices of 3rd millennium BCE.![]() Oxen pulled Bronze chariot found at Daimabad in MaharshtraDaimabad bronze chariot. c. 1500 BCE. 22X52X17.5 cm.Buffalo. Daimabad bronze. Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai.Daimabad bronzes. Buffalo on four-legged platform attached to four solid wheels 31X25 cm.; elephanton four-legged platform with axles 25 cm.; rhinoceros on axles of four solid wheels 25X19 cm. (MK Dhavalikar, 'Daimabad bronzes' in: Harappan civilization, ed. by GL Possehl, New Delhi, 1982, pp. 361-6; SA Sali, Daimabad 1976-1979, New Delhi, 1986).

Oxen pulled Bronze chariot found at Daimabad in MaharshtraDaimabad bronze chariot. c. 1500 BCE. 22X52X17.5 cm.Buffalo. Daimabad bronze. Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai.Daimabad bronzes. Buffalo on four-legged platform attached to four solid wheels 31X25 cm.; elephanton four-legged platform with axles 25 cm.; rhinoceros on axles of four solid wheels 25X19 cm. (MK Dhavalikar, 'Daimabad bronzes' in: Harappan civilization, ed. by GL Possehl, New Delhi, 1982, pp. 361-6; SA Sali, Daimabad 1976-1979, New Delhi, 1986).

Hieroglyph: पोळ [ pōḷa ]n C (Or पोळें ) A honeycomb. (Marathi)

पोळा [ pōḷā ]The cake-form portion of a honeycomb. A kindled portion flying up from a burning mass, a flake. पोळींव [ pōḷīṃva ] p of पोळणें Burned, scorched, singed, seared.पोळणें [ pōḷaṇēṃ ] v i To catch, burn, singe; to be seared or scorched.

This note demonstrates that the hieroglyph read rebus in Meluhha signifies a unique archaeometallurgy legacy of ancient India and Ancient Near East including the Levant.

Zebu when deployed as a hieroglyph multiplex on Indus Script corpora signifies magnetite Fe3O4 metalwork catalogues.

"Magnetite is a mineral, ferrous-ferric oxide, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism...Magnetite reacts with oxygen to produce hematite, and the mineral pair forms a buffer that can control oxygen fugacity."

"Magnetite is a mineral, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[ Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561. ] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism." http://www.pnas.org/content/99/26/16556.full.pdf loc.cit. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetite

Nausharo: céramique de la période I (c. 2500 BCE) cf. Catherine Jarrige![]()

After the domestication of the zebu, bos indicus, deployment of the hierolyph of zebu on Indus Script Corpora is a significant advance in archaeometallurgy documentation.

The writing system depicting a hieroglyph multiplex of a zebu tied to a post with a bird perched on top is based on the rebus rendering of the Prakritam glosses: Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' Rebus: magnetite, citizen. baTa 'quail' Rebus: baTha 'furnace'. The messaging on Nausharo pots of a magnetite furnace for metalwork continues on seals and tablets including copper plates as metalwork catalogues.

The Prakritam gloss पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' as hieroglyph is read rebus: pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide'; poliya 'citizen, gatekeeper of town quarter'.

Zebu also signifies a native metal blacksmith: another gloss for zebu: ad.ar d.an:gra (Santali); rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) d.han:gar ‘blacksmith’ (WPah.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada. Siddha_nti Subrahman.ya’ S’astri’s new interpretation of theAmarakos’a, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330). Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiramany ore. Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron. (DEDR 192). ayas 'metal' (Rigveda); aya 'iron' (Gujarati) Note: karba 'iron' is signified by hieroglyphs: karibha 'trunk of elephant' (Pali); ibha'elephant' (Samsritam). Thus, ajirda karba (Tulu) = aduru (aya) karba 'native metal iron' in semantic expansion of Prakritam in tune with archaeometallurgy advances in smelting, alloying and cire perduemetalcastings.

On a hieroglyph multiplex (hypertext), both zebu and elephant are signified by hieroglyph component: horn of zebu, trunk of elephant (together with other hieroglyph components such as tiger, snake, bovine, scarf, pannier):

Hieroglyph: पोळ [pōḷa] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. பொலியெருது poli-y-erutu , n. < பொலி- +. 1. Bull kept for covering; பசுக்களைச் சினையாக்குதற் பொருட்டு வளர்க்கப்படும் காளை. (பிங்.) கொடிய பொலியெருதை யிருமூக்கிலும் கயி றொன்று கோத்து (அறப். சத. 42). 2. The leading ox in treading out grain on a threshing-floor; களத்துப் பிணையல்மாடுகளில் முதற்செல்லுங் கடா. (W .) பொலி முறைநாகு poli-muṟai-nāku, n. < பொலி + முறை +. Heifer fit for covering; பொலியக்கூடிய பக்குவமுள்ள கிடாரி. (S. I. I . iv, 102.)

Rebus 1: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4'.

Rebus 2: pol m. ʻgate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate': Ka. por̤al town, city. Te. prōlu, (inscr.) pr̤ōl(u) city. ? (DEDR 4555) पोवळ or पोंवळ [ pōvaḷa or pōṃvaḷa ] f पोवळी or पोंवळी f The court-wall of a temple. (Marathi) *pratōlika ʻ gatekeeper ʼ. [pratōlī -- ] H. pauliyā, pol°, pauriyā m. ʻ gatekeeper ʼ, G. poḷiyɔ m.(CDIAL 8632) pratōlī f. ʻ gate of town or fort, main street ʼ MBh. [Cf. tōlikā -- . -- Perh. conn. with tōraṇa -- EWA ii 361, less likely with *ṭōla -- ] Pk. paōlī -- f. ʻ city gate, main street ʼ; WPah. (Joshi) prauḷ m., °ḷi f., pauḷ m., °ḷi f. ʻ gateway of a chief ʼ, proḷ ʻ village ward ʼ; H. paul, pol m. ʻ gate, courtyard, town quarter with its own gate ʼ, paulī f. ʻ gate ʼ; OG. poli f. ʻ door ʼ; G. poḷi f. ʻ street ʼ; M. pauḷ, poḷ f. ʻ wall of loose stones ʼ. -- Forms with -- r -- poss. < *pradura -- : OAw. paüri ʻ gatepost ʼ; H. paur, °rī, pãwar, °rī f. ʻ gate, door ʼ.WPah.poet. prɔ̈̄ḷ m., prɔḷo m., prɔḷe f. ʻ gate of palace or temple ʼ.(CDIAL 8633) Porin (adj.) [fr. pora=Epic Sk. paura citizen, see pura. Semantically cp. urbane>urbanus>urbs; polite= poli/ths>po/lis. For pop. etym. see DA i.73 & 282] belonging to a citizen, i. e. citizenlike, urbane, polite, usually in phrase porī vācā polite speech D i.4, 114; S i.189; ii.280=A ii.51; A iii.114; Pug 57; Dhs 1344; DA i.75, 282; DhsA 397. Cp. BSk. paurī vācā MVastu iii.322. Porisa2 (nt.) [abstr. fr. purisa, *pauruṣyaŋ, cp. porisiya and poroseyya] 1. business, doing of a man (or servant, cp. purisa 2), service, occupation; human doing, activity M i.85 (rāja˚); Vv 6311 (=purisa -- kicca VvA 263); Pv iv.324 (uṭṭhāna˚=purisa -- viriya, purisa -- kāra PvA 252). -- 2. height of a man M. i.74, 187, 365.(Pali) పౌరము [ pauramu ] pauramu. [Skt. from పుర.] adj. Belonging to a city or town (పురము.) పౌరసతులు the ladies of the place: citizens' wives. పౌరలోకము paura-lōkamu. n. The townsfolk, a body of citizens. పౌరుడు pauruḍu. n. A citizen. పౌరులు citizens, townsfolk.(Telugu)

वृषः 1 A bull; असंपदस्तस्य वृषेण गच्छतः Ku.5.8; Me.54; R.2.35; Ms.9.123. -2 The sign Taurus of the zodiac. -3 The chief or best of a class, the best of its kind; (often at the end of comp.); मुनिवृषः, कपिवृषः &c. -उत्सर्गः setting free a bull on the occasion of a funeral rite, or as a religious act generally; एकादशाहे प्रेतस्य यस्य चोत्सृज्यते वृषः । प्रेतलोकं परित्यज्य स्वर्गलोकं च गच्छति (Samskritam. Apte)

"The letting loose of a bull (vRshotsarga) stamped with Siva's trident -- in cities like Benares and Gaya is fraught with the highest merit. This setting free of a bull to roam about at will often takes place at zrAddhas." (Monier Monier-Williams, 1891, Brahmanism and Hinduism: or religious thought and life in Asia, Macmillan, p.319). In Hindu tradition, GRhyasUtra prescribe procedures for vRshotsarga.

"It is note-worthy that the details of the ceremony of setting a bull at liberty viz. the 'Vrshotsarga' in the Grhya-Sutras viz. S & P, in which it is described are almost identical (mutual borrowing or a common source are possibilities). On the Karttika full-moon day or on the day of the Asvayuja month falling under the Nakshtra RevatI, the fire is made to blaze in the midst of cows and Ajya oblations are sacrificed with ap propriate Mantras. Then he sacrifices from the Sthalipaka be longing to Pushan with an invocation to Pushan. Then he selects a bull of one, two or three colours or a red bull or one that leads the herd or is loved by the herd, perfect in all limbs and the finest in the herd, mumuring the Rudra-hymns. Then that bull is adorned, as also four of the finest young cows of the herd and then he says "This young bull, I give you as your husband; sporting with him, your lover, walk about etc." When the bull is in the midst of the cows, he recites over them the Rig-Verses X, 169. With the milk of all those cows he should cook milk-rice and feed the Brahmins with it. In the opinion of some (P) an animal is sacrificed in this rite, in which case the ritual is the same as that of the *sula-gava*." http://dli.gov.in/rawdataupload/upload/0113/986/RTF/00000141.rtf

Hieroglyph: eagle పోలడు [ pōlaḍu ] , పోలిగాడు or దూడలపోలడు pōlaḍu. [Tel.] n. An eagle. పసులపోలిగాడు the bird called the Black Drongo. Dicrurus ater. (F.B.I.)(Telugu)

Rebus: पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'magnetite', ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4 (Asuri)

Rebus: cattle festival: पोळा [ pōḷā ] m (पोळ ) A festive day for cattle,--the day of new moon of श्रावण or of भाद्रपद . Bullocks are exempted from labor; variously daubed and decorated; and paraded about in worship. "Pola is a bull-worshipping festival celebrated by farmers mainly in the Indian state of Maharashtra (especially among the Kunbis). On the day of Pola, the farmers decorate and worship their bulls. Pola falls on the day of the Pithori Amavasya (the new moon day) in the month of Shravana (usually in August)." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pola_(festival) Festival held on the day after Sankranti ( = kANum) is called pōlāla paNDaga (Telugu).

Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).

Toy animals made for the Pola festival especially celebrated by the Dhanoje Kunbis. (Bemrose, Colo. Derby - Russell, Robert Vane (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: volume IV. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. London: Macmillan and Co., limited. p. 40).Some artifacts of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization point to the possibility that the celebration of pola cattle festival may be traced to the cultural practices of 3rd millennium BCE.

Oxen pulled Bronze chariot found at Daimabad in Maharshtra

Daimabad bronze chariot. c. 1500 BCE. 22X52X17.5 cm.

Buffalo. Daimabad bronze. Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai.

Daimabad bronzes. Buffalo on four-legged platform attached to four solid wheels 31X25 cm.; elephanton four-legged platform with axles 25 cm.; rhinoceros on axles of four solid wheels 25X19 cm. (MK Dhavalikar, 'Daimabad bronzes' in: Harappan civilization, ed. by GL Possehl, New Delhi, 1982, pp. 361-6; SA Sali, Daimabad 1976-1979, New Delhi, 1986).

Hieroglyph: पोळ [ pōḷa ]n C (Or पोळें ) A honeycomb. (Marathi)

पोळा [ pōḷā ]The cake-form portion of a honeycomb. A kindled portion flying up from a burning mass, a flake. पोळींव [ pōḷīṃva ] p of पोळणें Burned, scorched, singed, seared.पोळणें [ pōḷaṇēṃ ] v i To catch, burn, singe; to be seared or scorched.

This note demonstrates that the hieroglyph read rebus in Meluhha signifies a unique archaeometallurgy legacy of ancient India and Ancient Near East including the Levant.

Zebu when deployed as a hieroglyph multiplex on Indus Script corpora signifies magnetite Fe3O4 metalwork catalogues.

"Magnetite is a mineral, ferrous-ferric oxide, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism...Magnetite reacts with oxygen to produce hematite, and the mineral pair forms a buffer that can control oxygen fugacity."

"Magnetite is a mineral, one of the three common naturally occurring iron oxides (chemical formula Fe3O4) and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth.[ Harrison, R. J.; Dunin-Borkowski, RE; Putnis, A (2002). "Direct imaging of nanoscale magnetic interactions in minerals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (26): 16556–16561. ] Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient people first noticed the property of magnetism."

http://www.pnas.org/content/99/26/16556.full.pdf loc.cit. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetite

Magnetite and pyrite from Piedmont, Italy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetite

Magnetite is a common mineral, an important ore of iron, ferromagnetic, that is, it is a natural magnet strongly attracted to magnetic fields. Heavily striated crystals with growth layers come from Parachinar, Pakistan. http://www.minerals.net/mineral/magnetite.aspx

"The process by which lodestone is created has long been an open question in geology. Only a small amount of the magnetite on Earth is found magnetized as lodestone. Ordinary magnetite is attracted to a magnetic field like iron and steel is, but does not tend to become magnetized itself; it has too low a magnetic coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) to stay magnetized for long...The leading theory suggests that lodestones are magnetized by the strong magnetic fields surrounding lightning bolts."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lodestone See: http://www.phy6.org/earthmag/lodeston.htm

[quote] Magnetite, a ferrimagnetic mineral with chemical formula Fe3O4, one of several iron oxides, is one of the more common meteor-wrongs. Magnetite displays a black exterior and magnetic properties.

![]()

magnetite

Magnetite can be a found in a meteorite's crust. When a meteor enters the earth's atmosphere the rock's surface is ablated by ultra high temperatures. Before it hits the ground, the molten surface solidifies into a thin glassy coating, called fusion crust. Crystals of magnetite color the thin fusion crust black. (Magnetite streaks black - see photo below)

![lodestone]()

lodestone

A piece of intensely magnetic magnetite was used as an early form of magnetic compass. Iron, steel and ordinary magnetite are attracted to a magnetic field, including the Earth's magnetic field. Only magnetite with a particular crystalline structure, lodestone, can act as a natural magnet and attract and magnetize iron. The name "magnet" comes from lodestones found in a place called Magnesia. [unquote] http://meteorite-identification.com/Hot%20Rocks/magnetite.html

Ancient Blacksmiths: ukku pola (steel from magnetite)?![]()

Magnetite var. lodestone 5.0x4.5x3.5cm With nails and metal dust attached to it.![]() Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku). "In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe." http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.html Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n (

Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku). "In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe." http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.html Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n (पोलादी 'steel'.पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n (पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

The Marathi gloss pōlāda may be formed with pōḷa+hlād = magnetite ore + rejoice.

pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri)

Magnetite is a common mineral, an important ore of iron, ferromagnetic, that is, it is a natural magnet strongly attracted to magnetic fields. Heavily striated crystals with growth layers come from Parachinar, Pakistan. http://www.minerals.net/mineral/magnetite.aspx

"The process by which lodestone is created has long been an open question in geology. Only a small amount of the magnetite on Earth is found magnetized as lodestone. Ordinary magnetite is attracted to a magnetic field like iron and steel is, but does not tend to become magnetized itself; it has too low a magnetic coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) to stay magnetized for long...The leading theory suggests that lodestones are magnetized by the strong magnetic fields surrounding lightning bolts."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lodestone See: http://www.phy6.org/earthmag/lodeston.htm

[quote] Magnetite, a ferrimagnetic mineral with chemical formula Fe3O4, one of several iron oxides, is one of the more common meteor-wrongs. Magnetite displays a black exterior and magnetic properties.

![]()

magnetite

Magnetite can be a found in a meteorite's crust. When a meteor enters the earth's atmosphere the rock's surface is ablated by ultra high temperatures. Before it hits the ground, the molten surface solidifies into a thin glassy coating, called fusion crust. Crystals of magnetite color the thin fusion crust black. (Magnetite streaks black - see photo below)

![lodestone]()

lodestone

A piece of intensely magnetic magnetite was used as an early form of magnetic compass. Iron, steel and ordinary magnetite are attracted to a magnetic field, including the Earth's magnetic field. Only magnetite with a particular crystalline structure, lodestone, can act as a natural magnet and attract and magnetize iron. The name "magnet" comes from lodestones found in a place called Magnesia. [unquote] http://meteorite-identification.com/Hot%20Rocks/magnetite.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lodestone See: http://www.phy6.org/earthmag/lodeston.htm

[quote] Magnetite, a ferrimagnetic mineral with chemical formula Fe3O4, one of several iron oxides, is one of the more common meteor-wrongs. Magnetite displays a black exterior and magnetic properties.

magnetite

Magnetite can be a found in a meteorite's crust. When a meteor enters the earth's atmosphere the rock's surface is ablated by ultra high temperatures. Before it hits the ground, the molten surface solidifies into a thin glassy coating, called fusion crust. Crystals of magnetite color the thin fusion crust black. (Magnetite streaks black - see photo below)

lodestone

A piece of intensely magnetic magnetite was used as an early form of magnetic compass. Iron, steel and ordinary magnetite are attracted to a magnetic field, including the Earth's magnetic field. Only magnetite with a particular crystalline structure, lodestone, can act as a natural magnet and attract and magnetize iron. The name "magnet" comes from lodestones found in a place called Magnesia. [unquote] http://meteorite-identification.com/Hot%20Rocks/magnetite.html

Ancient Blacksmiths: ukku pola (steel from magnetite)?

Magnetite var. lodestone 5.0x4.5x3.5cm With nails and metal dust attached to it.

Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku). "In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe." http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.html Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n (

Superb, mirror-like crystals of lustrous Magnetite covering one side of block of matrix. These Magnetite crystals are exceptionally sharp and well formed. 5 x 4 x 2 cm.A tool to use the magnetic qualities of iron is a lodestone (which is a natural magnetic iron oxide mineral). Such a tool could have enabled ancient blacksmiths to identify and distinguish a type if iron ore called ‘magnetite’ called in Meluhha: pola (which yields the Russian bulat steel) made from Latin wootz (Meluhha ukku). "In the Muslim world of the 9th-12th centuries CE, the production of fuladh, a Persian word, has been described by Al-Kindi, Al-Biruni and Al-Tarsusi, from narm-ahanand shaburqan, two other Persian words representing iron products obtained by direct reduction of the ore. Ahan means iron. Narm-ahan is a soft iron and shaburqan a harder one or able to be quench-hardened. Old nails and horse-shoes were also used as base for fuladh preparation. It must be noticed that, according to Hammer- Purgstall, there was no Arab word for steel, which explain the use of Persian words. Fuladh prepared by melting in small crucibles can be considered as a steel in our modem classification, due to its properties (hardness, quench hardened ability, etc.). The word fuladh means "the purified" as explained by Al-Kindi. This word can be found as puladh, for instance in Chardin (1711 AD) who called this product; poulad jauherder, acier onde, which means "watering steel", a characteristic of what was called Damascene steel in Europe." http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.html Known to ancient Greeks, magnetite was so-called because it was found in the lands of the Magnetes (Magnesia) in Thessaly. Ancient Indians (Bharatam Janam) called it पोळ [pōḷa] which gave the root for the famed crucible wootz steel called पोलाद [pōlāda] n (पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n (पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

The Marathi gloss pōlāda may be formed with pōḷa+hlād = magnetite ore + rejoice.

pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/ancient-blacksmiths.html Three mineral ores: pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite) -- all three Meluhha glosses -- are three varieties of minerals with sources for alloying metals. The importance of bichi (hematite) as a hieroglyph has been detailed.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/09/catalogs-of-pola-kuntha-gota-bichi.html Catalogs of pola, kuṇṭha, goṭa, bichi native metalwork in Meluhha Indus script hieroglyphs

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/09/catalogs-of-pola-kuntha-gota-bichi.html Catalogs of pola, kuṇṭha, goṭa, bichi native metalwork in Meluhha Indus script hieroglyphs

Socio-cultural context in which pola and gota were recognized by early metalworkers (blacksmiths):

While we do not know where this piece was found, the zebu bull motif ("the essence of civilization" according to the Italian exhibitors) is similar to a pot found at Nausharo in Balochistan and dated to roughly 2600-2500 BCE. The archaeologist Ute-Franke-Vogt writes about the Kulli culture from which it may stem "This late Kulli occupation to which the largest number of sites in southern Balochistan belong, co-existed with the Indus Civilization (Kanri Buthi). http://balochhistory11.blogspot.in/2014/12/brilliantly-painted-pottery-vessels.html![]()

Nausharo, Mehrgarh: ceramique c. 2500 BCE, C. Jarrige. Nausharo was inhabited later than Mehrgarh, probably first from about 2800 BCE C. Jarrige ![]()

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above.

Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo,

ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.

Bos indicus motif on a pot from the Mehrgarh period (ca. 7000-5500 BCE)

Hieroglyph: baṭa 'quail'; bhaṭa 'furnace' (G.); baṭa 'a kind of iron' (Gujarati.)

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite'.

meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻpost, forked stakeʼ rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.); med 'copper'

![]()

![]() Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli.

Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli. ![Click to view original image.]() Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329

Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329

Origin: Pakistan/Western India

Circa: 3500 BC to 2000 BC Dimensions: 11.1" (28.2cm) high x 12.9" (32.8cm) wide

Collection: Asian Art

Medium: Terracotta

http://barakatgallery.com/store/Index.cfm/FuseAction/ItemDetails/UserID/catalogue/ItemID/23292/CFID/9319250/CFTOKEN/12663335.htmkuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'.

![]() Nausharo. Pot

Nausharo. Pot

![Diversity 06 00705 g001 1024]()

![]()

"Slide 32. Three Early Harappan zebu figurines from Harappa. The earliest animal figurines from Harappa are Early Harappan (Ravi Phase, Period 1 and Kot Diji Phase, Period 2) zebu figurines. They are typically very small with joined legs and stylized humps. A few of these zebu figurines have holes through the humps that may have allowed them to be worn as amulets on a cord or a string. One Early Harappan zebu figurine was found with the remains of a copper alloy ring still in this hole. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D) of the uppermost figurine: 1.2 x 3.3 x 2.8 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)."http://www.harappa.com/figurines/32.html![]()

"Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots from Harappa. Some of the Early Harappan zebu figurines were decorated. One example has incised oval spots. It is also stained a deep red, an extreme example of the types of stains often found on figurines that are usually found in trash and waste deposits. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 1.8 x 4.6 x 3.5 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/33.html![]()

"Slide 68. Wheeled zebu figurine from Harappa. A small subset of the figurines from Harappa originally had wheels. Of the many small terracotta wheels found at Harappa, at least some must have been intended for these wheeled objects. One style of wheeled figurine has lateral holes for the axles through the bottom of the torso. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 5.9 x 6.2 x 8.7 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/68.html![]()

"Slide 34. Zebu figurine with painted designs from Harappa. Other animal and sometimes anthropomorphic figurines are decorated with black stripes and other patterns, and features such as eyes are also sometimes rendered in pigment. Figurines of cattle with and without humps are found at Indus sites, possibly indicating that multiple breeds of cattle were in use. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 3.9 x 8.5 x 5.5 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/34.html![]()

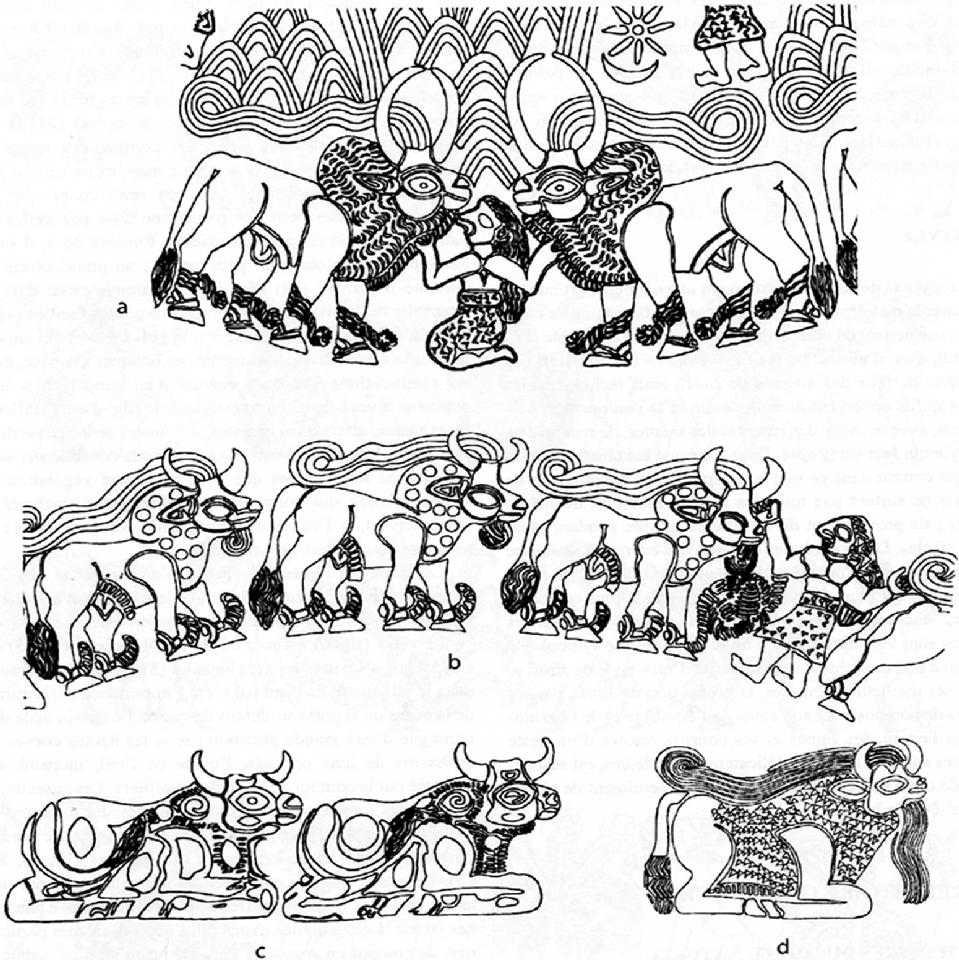

http://www.harappa.com/indus/27.html "Bull seal, Harappa. The majestic zebu bull, with its heavy dewlap and wide curving horns is perhaps the most impressive motif found on the Indus seals. Generally carved on large seals with relatively short inscriptions, the zebu motif is found almost exclusively at the largest cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. The rarity of zebu seals is curious because the humped bull is a recurring theme in many of the ritual and decorative arts of the Indus region, appearing on painted pottery and as figurines long before the rise of cities and continuing on into later historical times. The zebu bull may symbolize the leader of the herd, whose strength and virility protects the herd and ensures the procreation of the species or it stands for a sacrificial animal. When carved in stone, the zebu bull probably represents the most powerful clan or top officials of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa Archaeological Research Project."![]() After Figure 1. Major domestic cattle species: (a) Spanish Tudanca taurine and (b) Pullikulam zebu bull (photographs by Marleen Felius and Anno Fokkinga, 2008, 2005). After Fig. 7 Pictorial evidence of the origin and dispersal of zebu. (a) Harappa seal (National Museum, India, [70]), 5000–3500 BP; (b) detail of cylindrical chlorite vessel (Mesopotamia (mid-5th millennium BP, The British Museum, London); (c) detail of conic object from Tarut Island near the Eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula (Metropolitan Museum, NY) and (d) detail of a painting: inspection of cattle belonging to Nebamun, Thebes,ca. 3400 BP, The British Museum, London). http://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/6/4/705/htm Marleen Felius et al, 2014, On the history of cattle genetic resources, Diversity 2014, 6(4), 705-750 "Around 2000 years after the taurine domestication, zebu was domesticated in the Indus Valley at the edge of the Indian Desert. Fossil remains attributed to zebu have been found in Mehrgarh, a proto-Indus culture site in Baluchistan in southwest Pakistan and were dated at 8000 BP."

After Figure 1. Major domestic cattle species: (a) Spanish Tudanca taurine and (b) Pullikulam zebu bull (photographs by Marleen Felius and Anno Fokkinga, 2008, 2005). After Fig. 7 Pictorial evidence of the origin and dispersal of zebu. (a) Harappa seal (National Museum, India, [70]), 5000–3500 BP; (b) detail of cylindrical chlorite vessel (Mesopotamia (mid-5th millennium BP, The British Museum, London); (c) detail of conic object from Tarut Island near the Eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula (Metropolitan Museum, NY) and (d) detail of a painting: inspection of cattle belonging to Nebamun, Thebes,ca. 3400 BP, The British Museum, London). http://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/6/4/705/htm Marleen Felius et al, 2014, On the history of cattle genetic resources, Diversity 2014, 6(4), 705-750 "Around 2000 years after the taurine domestication, zebu was domesticated in the Indus Valley at the edge of the Indian Desert. Fossil remains attributed to zebu have been found in Mehrgarh, a proto-Indus culture site in Baluchistan in southwest Pakistan and were dated at 8000 BP."

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/bronze-zebu-figurine-in-samaria-meluhha.html

![]()

![]()

After Figure 11: a. mountains landscape and waers; (upper part) a man under an arch with sun and crescent moon symbols; (lower part) man seated on his heels holding zebus; b. man holding a snake; c. two men (drinking) and zebus, on a small cylindrical vessel; d. Head of woman protruding from jar, and snakes; 3. man falling from a tree to the trunk of which a zebu is tied; f. man with clas and bull-man playing with cheetahs, and a scorpion in the center (on a cylindrical vessel). http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts.![]()

![]() http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts![]()

While we do not know where this piece was found, the zebu bull motif ("the essence of civilization" according to the Italian exhibitors) is similar to a pot found at Nausharo in Balochistan and dated to roughly 2600-2500 BCE. The archaeologist Ute-Franke-Vogt writes about the Kulli culture from which it may stem "This late Kulli occupation to which the largest number of sites in southern Balochistan belong, co-existed with the Indus Civilization (Kanri Buthi). http://balochhistory11.blogspot.in/2014/12/brilliantly-painted-pottery-vessels.html

Nausharo, Mehrgarh: ceramique c. 2500 BCE, C. Jarrige. Nausharo was inhabited later than Mehrgarh, probably first from about 2800 BCE C. Jarrige

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above.

Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo,

ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.

Bos indicus motif on a pot from the Mehrgarh period (ca. 7000-5500 BCE)

Hieroglyph: baṭa 'quail'; bhaṭa 'furnace' (G.); baṭa 'a kind of iron' (Gujarati.)

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite'.

meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻpost, forked stakeʼ

rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.); med 'copper'

Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli.

Slippainted cylindrical jar. Kulli.  Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329

Indus Valley Terracotta Vessel - LO.1329Origin: Pakistan/Western India

Circa: 3500 BC to 2000 BC Dimensions: 11.1" (28.2cm) high x 12.9" (32.8cm) wide

Collection: Asian Art

Medium: Terracotta

http://barakatgallery.com/store/Index.cfm/FuseAction/ItemDetails/UserID/catalogue/ItemID/23292/CFID/9319250/CFTOKEN/12663335.htm

kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'.

![]() Nausharo. Pot

Nausharo. Pot

"Slide 32. Three Early Harappan zebu figurines from Harappa. The earliest animal figurines from Harappa are Early Harappan (Ravi Phase, Period 1 and Kot Diji Phase, Period 2) zebu figurines. They are typically very small with joined legs and stylized humps. A few of these zebu figurines have holes through the humps that may have allowed them to be worn as amulets on a cord or a string. One Early Harappan zebu figurine was found with the remains of a copper alloy ring still in this hole. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D) of the uppermost figurine: 1.2 x 3.3 x 2.8 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)."http://www.harappa.com/figurines/32.html

"Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots from Harappa. Some of the Early Harappan zebu figurines were decorated. One example has incised oval spots. It is also stained a deep red, an extreme example of the types of stains often found on figurines that are usually found in trash and waste deposits. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 1.8 x 4.6 x 3.5 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/33.html

"Slide 68. Wheeled zebu figurine from Harappa. A small subset of the figurines from Harappa originally had wheels. Of the many small terracotta wheels found at Harappa, at least some must have been intended for these wheeled objects. One style of wheeled figurine has lateral holes for the axles through the bottom of the torso. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 5.9 x 6.2 x 8.7 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/68.html

"Slide 34. Zebu figurine with painted designs from Harappa. Other animal and sometimes anthropomorphic figurines are decorated with black stripes and other patterns, and features such as eyes are also sometimes rendered in pigment. Figurines of cattle with and without humps are found at Indus sites, possibly indicating that multiple breeds of cattle were in use. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 3.9 x 8.5 x 5.5 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)." http://www.harappa.com/figurines/34.html

http://www.harappa.com/indus/27.html "Bull seal, Harappa. The majestic zebu bull, with its heavy dewlap and wide curving horns is perhaps the most impressive motif found on the Indus seals. Generally carved on large seals with relatively short inscriptions, the zebu motif is found almost exclusively at the largest cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. The rarity of zebu seals is curious because the humped bull is a recurring theme in many of the ritual and decorative arts of the Indus region, appearing on painted pottery and as figurines long before the rise of cities and continuing on into later historical times. The zebu bull may symbolize the leader of the herd, whose strength and virility protects the herd and ensures the procreation of the species or it stands for a sacrificial animal. When carved in stone, the zebu bull probably represents the most powerful clan or top officials of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa. Harappa Archaeological Research Project."

After Figure 1. Major domestic cattle species: (a) Spanish Tudanca taurine and (b) Pullikulam zebu bull (photographs by Marleen Felius and Anno Fokkinga, 2008, 2005). After Fig. 7 Pictorial evidence of the origin and dispersal of zebu. (a) Harappa seal (National Museum, India, [70]), 5000–3500 BP; (b) detail of cylindrical chlorite vessel (Mesopotamia (mid-5th millennium BP, The British Museum, London); (c) detail of conic object from Tarut Island near the Eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula (Metropolitan Museum, NY) and (d) detail of a painting: inspection of cattle belonging to Nebamun, Thebes,ca. 3400 BP, The British Museum, London). http://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/6/4/705/htm Marleen Felius et al, 2014, On the history of cattle genetic resources, Diversity 2014, 6(4), 705-750 "Around 2000 years after the taurine domestication, zebu was domesticated in the Indus Valley at the edge of the Indian Desert. Fossil remains attributed to zebu have been found in Mehrgarh, a proto-Indus culture site in Baluchistan in southwest Pakistan and were dated at 8000 BP."

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/bronze-zebu-figurine-in-samaria-meluhha.html

![]()

![]()

After Figure 11: a. mountains landscape and waers; (upper part) a man under an arch with sun and crescent moon symbols; (lower part) man seated on his heels holding zebus; b. man holding a snake; c. two men (drinking) and zebus, on a small cylindrical vessel; d. Head of woman protruding from jar, and snakes; 3. man falling from a tree to the trunk of which a zebu is tied; f. man with clas and bull-man playing with cheetahs, and a scorpion in the center (on a cylindrical vessel). http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/bronze-zebu-figurine-in-samaria-meluhha.html

After Figure 11: a. mountains landscape and waers; (upper part) a man under an arch with sun and crescent moon symbols; (lower part) man seated on his heels holding zebus; b. man holding a snake; c. two men (drinking) and zebus, on a small cylindrical vessel; d. Head of woman protruding from jar, and snakes; 3. man falling from a tree to the trunk of which a zebu is tied; f. man with clas and bull-man playing with cheetahs, and a scorpion in the center (on a cylindrical vessel). http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts.

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts

Lapis lazuli stamp seal. Behind the man, drummer, are a stream, a long-horned, bearded goat above a zebu. Mountain range with a line of over 15 notches and a circle on top register. Bronze Age, about 2400-2000 BCE From the ancient Near East British Museum.Height: 3.100 cm Thickness: 2.500 cm Width: 4.000 cm ME 1992-10-7,1 mē d 'drummer' rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron (metal) poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite' Hieroglyph: miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.Munda) meTTu 'range' rebus: meD 'iron' khareḍo = a currycomb (Gujarati) खरारा [ kharārā ] m ( H) A currycomb. 2 Currying a horse. (Marathi) Rebus: 1. करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) 2. kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati)

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'. ~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.KW <i>mENhEd</i>@(V168,M080) http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/austroasiatic/AA/Munda/ETYM/Pinnow&Munda— Slavic glosses for 'copper' Мед [Med]Bulgarian Bakar Bosnian Медзь [medz']Belarusian Měď Czech Bakar oatian KòperKashubian Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian Miedź Polish Медь [Med']Russian Meď Slovak BakerSlovenian Бакар [Bakar]Serbian Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote] http://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element.php?sym=Cu Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'. One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

![]() In this hieroglyph multiplex on the lapis-lazuli stamp seal, there are three hieroglyph components: 1. roundish ball; 2. notches (over 15 short strokes down a line); 3. mountain range.Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry(DEDR 069) N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ (CDIAL 4271) <gOTa>(P) {ADJ} ``^whole''. {SX} ``^numeral ^intensive suffix''. *Kh., Sa., Mu., Ho<goTA>,B.<goTa> `undivided'; Kh.<goThaG>(P), Sa.<goTAG>,~<gOTe'j>, Mu.<goTo>; Sad.<goT>, O., Bh.<goTa>; cf.Ju.<goTo> `piece', O.<goTa> `one'. %11811. #11721. <goTa>(BD) {NI} ``the ^whole''. *@. #10971. (Munda etyma)Rebus: <gota> {N} ``^stone''. @3014. #10171. Note: The stone may be gota, laterite mineral ore stone. khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ (Punjabi) Rebus: koṭe ‘forging (metal)(Mu.) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.) goṭi = silver (G.) koḍ ‘workshop’ (Gujarati).bus: P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ(CDIAL 4271)