Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/nnq57yg

Indus Script inscriptions, e.g. on Kalibangan terracotta cake, found in fire-altars of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization compare with Yupa inscriptions of Yajna-s.

Many inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora are found from archaeological sites which also evidenced fire-altars and metalwork, sites such as Kalibangan, Binjor, Lothal, Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi.

This monograph presents the Vedic tradition of Cosmic pillar, Atharva Veda Skambha, in the context of archaeological evidences of fire-altars of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization, Yupa inscriptions.

The significance of the yupa or yaṣṭi found in almost every fire-altar of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization is central to unraveling the worship of aniconic Siva linga, Rudra, as a cosmic dancer manifesting the transmutation of mere earth and stone into metal in smelters, furnaces and fire-altars of the civilization.

I suggest the यूप yupa inscriptions of Rajasthan found close to Binjor, Kalibangan and other archaeological sites of the civilization and Indonesia are Kāṇḍarishi काण्डर्षि tarpaṇam venerating the traditions handed down by the Vedic Rishis. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/12/binjor-seal-with-indus-script.html

The Kalibangan fire-altar had a यूप yupa; an inscription in Indus Script hieroglyphs was found in a terracotta cake found in a fire-altar (See details below). This tradition of doumenting inscriptions related to work in fire-altar continued in historical periods in yupa inscriptions documenting yajna-s performed and wealth distributed.

![]()

I do not know why BrahmaNa texts derive the word यूप yupa from the root yup, 'to efface, to scatter, debar, conceal'.. Satapatha Brahmana: By means of the sacrifice the gods gained that supreme authority which the now wield. They spake, ' How can this (world) of ours be made unattainable to men ?' They sipped the sap of the sacrifice, even as bees would suck out honey ; and having drained the sacrifice and scattered it by means of the sacrificial post, they disappeared : and because they scattered (yopaya, viz. the sacrifice) therewith, therefore it is called yupa (post) (SBr. iii KANDA, 4 ADHYAYA, III Brahmana, 14, page 101)

“...Yupa is a straight upright stone, like a truncated column. It has six or eight angles and a rounded head at the top, and represents the sacrificial post cut from the trunk of a tree to which in vedic sacrifices the victim was tied. Placed on the summit of a temple in place of the amRta kalas'a, it has a deep significance. The PuruSa has from the time of the Vedas and the BrahmaNas has been associated with the ideas of Yupa, vanaspati, yajna (sacrificial post, tree or lord of the forest and sacrifice). In the famous PuruSa sukta of the Rigveda the great PuruSa is tied to the stake by the gods, and out of the sacrifice of his person arose the entire universe. The Vedas, the Vajaseya SamhitA, the TaittirIya SamhitA, the S'atapatha BrAhmanAs, the S'rauta Sutras, all scriptures have extolled his greatness as the supreme divinity, Divinity born of sacrifice. And in subsequent times this PuruSa can still be recognized under other names, as Ekam, Sat, Atman, PuruSottama, Brahman. The yupa on the summit of a temple, which appears as an extension of the axis of the whole building speaks it out in unmistakable terms, that sacrifice not only created the world, but is that which in the form of a pillar, always upholds it. Sacrifice is the 'axis mundi'. When the yupa is installed with great ceremony by the chief architect and the offering priest, it is done under recitation of the RudAdhyAya of the White Yajurveda. This hymn is an invocation to the most terrible and destructive aspects of Rudra in terms as these: 'Loosen thy bowstring, loosen it from thy bow's two extremities and cast away, o Lord divine, the arrows that are in thy hands'.'Having unbent thy bow, o thou hundred-eyed, hundred-quivered one! And dulled thy pointed arrows' heads, be kind and gracious unto us! Behind such fervent prayers stands the knowledge that the yupa is indeed the 'axis of the universe', which, like the mast of a ship, might be endangered by the storm, but which by Rudra's grace should remain standing firm on its divine foundations and should not ever be uprooted by inimical forces.” (Alice Boner, Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā, 1966, Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture, Brill Archive, p.xlii.)

Yupa inscriptions of the historical periods from 2nd century are a continuum of the tradition of implanting a yaṣṭi in fire-altars of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. It appears that the implanting of a yaṣṭi together with terracotta cakes (one cake has been found in Kalibangan with Indus Script hieroglyphs signifying metalwork in smelters) is a proclamation of metalwork, the same way the inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora are proclamations, constituting catalogus catalogorum of metalwork.

In Kalibangan, the fire-altar revealed a Yaṣṭi which is a clearly identifiable as a yupa or skambha of Rigveda/Atharva Veda texts. The Yupa Skambha is an extraordinary metaphor used in many Vedic texts describing the sacred processes involved in a yajna. The sacred processes are a manifestation of the cosmic dance of Siva (symbolised by the Skambha as linga or stele in fire-altars like the one discovered in Kalibangan).

Indus Script inscriptions, e.g. on Kalibangan terracotta cake, found in fire-altars of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization compare with Yupa inscriptions of Yajna-s.

Many inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora are found from archaeological sites which also evidenced fire-altars and metalwork, sites such as Kalibangan, Binjor, Lothal, Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi.

This monograph presents the Vedic tradition of Cosmic pillar, Atharva Veda Skambha, in the context of archaeological evidences of fire-altars of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization, Yupa inscriptions.

The significance of the yupa or yaṣṭi found in almost every fire-altar of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization is central to unraveling the worship of aniconic Siva linga, Rudra, as a cosmic dancer manifesting the transmutation of mere earth and stone into metal in smelters, furnaces and fire-altars of the civilization.

I suggest the यूप yupa inscriptions of Rajasthan found close to Binjor, Kalibangan and other archaeological sites of the civilization and Indonesia are Kāṇḍarishi काण्डर्षि tarpaṇam venerating the traditions handed down by the Vedic Rishis. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/12/binjor-seal-with-indus-script.html

The Kalibangan fire-altar had a यूप yupa; an inscription in Indus Script hieroglyphs was found in a terracotta cake found in a fire-altar (See details below). This tradition of doumenting inscriptions related to work in fire-altar continued in historical periods in yupa inscriptions documenting yajna-s performed and wealth distributed.

The yupa or yaṣṭi of fire-altars is comparable to the three stalks shown on Sit-Shamshi Bronze which is a narrative of bronze metalwork and sun worship. Close to the three stalks are located a yupa or pillar, two water-troughs, L-shaped pITham. The three stalks are signified by the expression: kolmo kaṇḍa'three stalks' rebus: kolimi 'smithy/forge'; khaNDa 'implements'. "Sit Shamshi bronze model with a 60x40 cm base is a breathtaking narrative of an offering made at sunrise. An inscription on the model is in Akkadian while the underlying language is Elamite which refers to sit e sham. Philological links are traced to the Vedic tradition of Upakarma annual reaffirmation of the vow to protect dharma, veneration of the Sun, ancestors and sages who have shown the righteous path. Annual Kāṇḍarishi काण्डर्षि tarpaṇam is performed. I suggest that the ancestral memory of Kāṇḍa, 'metalwork' is enshrined in the Sit Shamshi model presenting Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplexes in rebus-metonymy layered cipher of Meluhha, Indian sprachbund."

I do not know why BrahmaNa texts derive the word यूप yupa from the root yup, 'to efface, to scatter, debar, conceal'.. Satapatha Brahmana: By means of the sacrifice the gods gained that supreme authority which the now wield. They spake, ' How can this (world) of ours be made unattainable to men ?' They sipped the sap of the sacrifice, even as bees would suck out honey ; and having drained the sacrifice and scattered it by means of the sacrificial post, they disappeared : and because they scattered (yopaya, viz. the sacrifice) therewith, therefore it is called yupa (post) (SBr. iii KANDA, 4 ADHYAYA, III Brahmana, 14, page 101)

https://ia802704.us.archive.org/9/items/satapathabrahman02egge/satapathabrahman02egge_bw.pdf यूप [p=856,1] m. (prob. fr. √ युप् ; but according to Un2. iii , 27 , fr. √2. यु) a post , beam , pillar , (esp.) a smooth post or stake to which the sacrificial victim is fastened , any sacrificial post or stake (usually made of bamboos or खदिर wood ; in R. i , 13 , 24 ; 25, where the horse sacrifice is described , 21 of these posts are set up , 6 made of बिल्व , 6 of खदिर , 6 ofपलाश , one of उडुम्बर , one of श्लेष्मातक , and one of देव-दारु) RV. &c; a column erected in honour of victory , a trophy (= जय-स्तम्भ) L.

यूपं कृत्वा तु मलयमवनाहं च तक्षकम् Mb.7.22.73. Binding, girding, putting on.-

antahpAtah'a post fixed in the middle of the sacrificial ground (used in ritual works); अन्तःपूर्वेण यूपं परीत्यान्तःपात्यदेशे स्थापयति Kāty'.

Satapatha Brahmana III.7.1.4 seems to refer to the Yupa as a cosmic tree.

See also: Sbr. V.2.1.9: While setting up the ladder, the yajnika says to his wife, 'Come, let us go up to Heaven'. She answers, 'Let us go up'. (Sbr V.2.1.9) and they begin to mount the ladder. At the top, while touching the head of the post, the yajnika says: 'We have reached Heaven' (Taittiriya Samhita, SBr. Etc.) 'I have attained to heaven, to the gods, I have become immortal' (Taittiriya samhita 1.7.9) 'In truth, the yajnika makes himself a ladder and a bridge to reach the celestial world' (Taittiriya Samhita VI.6.4.2)

Eggeling' translation of Sbr. Pt III, Vol. XLI, Oxford, 1894, p.31 says:

“The post is either wrapped up or bound up in 17 cloths for Prajapati is 17-fold.' The top of the Yupa carries a wheel called cas'Ala in a horizontal position. The indrakila too is adorned with a wheel-ike object made of white cloth, but it is placed in a vertical position.

Notes taken from 'The symbolism of the Indrakila' Senarat Paranavitana, Leelananda Prematilleka, Johanna Engelberta van Lohulzen-De Leeuw, 1978, Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume, BRILL 1978, p.247)

Yupa is axis mundi, axis of the Universe, Rudra's grace

“...Yupa is a straight upright stone, like a truncated column. It has six or eight angles and a rounded head at the top, and represents the sacrificial post cut from the trunk of a tree to which in vedic sacrifices the victim was tied. Placed on the summit of a temple in place of the amRta kalas'a, it has a deep significance. The PuruSa has from the time of the Vedas and the BrahmaNas has been associated with the ideas of Yupa, vanaspati, yajna (sacrificial post, tree or lord of the forest and sacrifice). In the famous PuruSa sukta of the Rigveda the great PuruSa is tied to the stake by the gods, and out of the sacrifice of his person arose the entire universe. The Vedas, the Vajaseya SamhitA, the TaittirIya SamhitA, the S'atapatha BrAhmanAs, the S'rauta Sutras, all scriptures have extolled his greatness as the supreme divinity, Divinity born of sacrifice. And in subsequent times this PuruSa can still be recognized under other names, as Ekam, Sat, Atman, PuruSottama, Brahman. The yupa on the summit of a temple, which appears as an extension of the axis of the whole building speaks it out in unmistakable terms, that sacrifice not only created the world, but is that which in the form of a pillar, always upholds it. Sacrifice is the 'axis mundi'. When the yupa is installed with great ceremony by the chief architect and the offering priest, it is done under recitation of the RudAdhyAya of the White Yajurveda. This hymn is an invocation to the most terrible and destructive aspects of Rudra in terms as these: 'Loosen thy bowstring, loosen it from thy bow's two extremities and cast away, o Lord divine, the arrows that are in thy hands'.'Having unbent thy bow, o thou hundred-eyed, hundred-quivered one! And dulled thy pointed arrows' heads, be kind and gracious unto us! Behind such fervent prayers stands the knowledge that the yupa is indeed the 'axis of the universe', which, like the mast of a ship, might be endangered by the storm, but which by Rudra's grace should remain standing firm on its divine foundations and should not ever be uprooted by inimical forces.” (Alice Boner, Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā, 1966, Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture, Brill Archive, p.xlii.)

Yaṣṭi is a yupa or skambha which signifies a baton of divine authority impacting metalwork of Bharatam Janam. Similarly, the yupa inscriptions of historical periods are proclamations of commemoration, of fire-worship such as AgniSToma or As'vamedha. The inscriptions also detail sharing of wealth.

See: Pages 160-161 of Satapatha Brahmana text SBr I.6.2.4

http://tinyurl.com/phj2eae The metaphor of the yupa is the extraordinarily complex and it is virtually impossible to unravel the details of the metalwork/fire-work processes signified by the skambha as a hieroglyph, a baton of divine authority to explain the phenomena of mere earth and stone getting transformed into metal in smelters/furnaces/fire-altars as a manifestation of divine dispensation.

In Kalibangan, the fire-altar revealed a Yaṣṭi which is a clearly identifiable as a yupa or skambha of Rigveda/Atharva Veda texts. The Yupa Skambha is an extraordinary metaphor used in many Vedic texts describing the sacred processes involved in a yajna. The sacred processes are a manifestation of the cosmic dance of Siva (symbolised by the Skambha as linga or stele in fire-altars like the one discovered in Kalibangan).![]() Kalibangan. Fire-altar with stele 'linga' and terracotta cakes. Plate XXA. "Within one of the rooms of amost each house was found the curious 'fire-altar', sometimes also in successive levels, indicating their recurrent function." (p.31)

Kalibangan. Fire-altar with stele 'linga' and terracotta cakes. Plate XXA. "Within one of the rooms of amost each house was found the curious 'fire-altar', sometimes also in successive levels, indicating their recurrent function." (p.31)

The stele found in Kalibangan fire-altar is comarable to the Yupa of historical periods from ca. 2nd century found in Rajasthan and Indonesia. These Yupa detail inscriptions of yajna-s and distribution of wealth, the way the terracotta cake found in Kalibangan fire-altar in Indus Script hieroglyphs signified the metal work or creation of wealth with a smelter.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/12/yastifound-in-fire-altars-of-sarasvati.html

[quote] Anthropologist Christopher John Fuller conveys that although most sculpted images (murtis) are anthropomorphic, the aniconic Shiva Linga is an important exception.( The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and society in India, pg. 58). There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda which praises a pillar (Sanskrit: stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga-worship.(N. K. Singh, Encyclopaedia of Hinduism p. 1567.

The Hindu scripture, Shiva Purana, describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (Stambha) of fire, the cause of all causes. ( Chaturvedi. Shiv Purana (2006 ed.). Diamond Pocket Books. p. 11) Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the Lingam – the cosmic pillar of fire – proving his superiority over gods Brahma and Vishnu.This is known as Lingodbhava. The Linga Purana also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva. According to Linga Purana, the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer - the oval shaped stone is resembling mark of the Universe and bottom base as the Supreme Power holding the entire Universe in it. (" It was almost as if the linga had emerged to settle Brahma and Vishnu’s dispute. The linga rose way up into the sky and it seemed to have no beginning or end.") Similar interpretation is also found in the Skanda Purana: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself."(http://is1.mum.edu/vedicreserve/skanda.htm)In yogic lore, the linga is considered the first form to arise when creation occurs, and also the last form before the dissolution of creation. It is therefore seen as an access to Shiva or that which lies beyond physical creation.

Sources: Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157

Vivekananda, Swami."The Paris Congress of the History of Religions".The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol.4.

Blurton, T. R. (1992). "Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava". Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press). British Museum site. Retrieved 2 July 2010. [unquote]

https://www.scribd.com/doc/293482764/Skanda-Purana-maheshvara-kaumari-kandam

![Inline image 1]() Kalibangan. Mature Indus period: terracotta cake incised with horned deity. Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India See notes at http://bharatkalyan97.

Kalibangan. Mature Indus period: terracotta cake incised with horned deity. Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India See notes at http://bharatkalyan97.bakura <-> ʻ bellows ʼ ~ bākurá -- dŕ̊ti -- ʻ goat's skin ʼ), der. from bastá -- m. ʻ goat ʼ RV. (cf.bastājina -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ MaitrS. = bāstaṁ carma Mn.); with bh -- (and unexpl. -- st -- ) in Pa. bhasta -- m. ʻ goat ʼ, bhastacamma -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ. Phonet. Pa. and all NIA. (except S. with a) may be < *bhāsta -- , cf. bāsta -- above (J. C. W.)]With unexpl. retention of -- st -- : Pa. bhastā -- f. ʻ bellows ʼ (cf. vāta -- puṇṇa -- bhasta -- camma -- n. ʻ goat's skin full ofwind ʼ), biḷāra -- bhastā -- f. ʻ catskin bag ʼ, bhasta -- n. ʻ leather sack (for flour) ʼ; K. khāra -- basta f. ʻ blacksmith's skin bellows ʼ; -- S. bathī f. ʻ quiver ʼ (< *bhathī); A. Or. bhāti ʻ bellows ʼ, Bi. bhāthī, (S of Ganges) bhã̄thī; OAw. bhāthā̆ ʻ quiver ʼ; H. bhāthā m. ʻ quiver ʼ, bhāthī f. ʻ bellows ʼ; G. bhāthɔ,bhātɔ, bhāthṛɔ m. ʻ quiver ʼ (whence bhāthī m. ʻ warrior ʼ); M. bhātā m. ʻ leathern bag, bellows, quiver ʼ, bhātaḍ n. ʻ bellows, quiver ʼ; <-> (X bhráṣṭra -- ?) N. bhã̄ṭi ʻ bellows ʼ, H. bhāṭhī f.*khallabhastrā -- .Addenda: bhástrā -- : OA. bhāthi ʻ bellows ʼ .(CDIAL 9424) bhráṣṭra n. ʻ frying pan, gridiron ʼ MaitrS. [√bhrajj ]

Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭhü f. ʻ level surface by kitchen fireplace on which vessels are put when taken off fire ʼ; S. baṭhu m. ʻ large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire ʼ, baṭhī f. ʻ distilling furnace ʼ; L. bhaṭṭh m. ʻ grain -- parcher's oven ʼ, bhaṭṭhī f. ʻ kiln, distillery ʼ, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭhm., °ṭhī f. ʻ furnace ʼ, bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ; N. bhāṭi ʻ oven or vessel in which clothes are steamed for washing ʼ; A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v.bhrāṣṭra -- ; *bhraṣṭrapūra -- , *bhraṣṭrāgāra -- .Addenda: bhráṣṭra -- : S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ.*bhraṣṭrāgāra ʻ grain parching house ʼ. [bhráṣṭra -- , agāra -- ]P. bhaṭhiār, °ālā m. ʻ grainparcher's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 9656, 9658)

![]()

![]()

![]() Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2).This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2).This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually मेढ q. v.) मेडका m A stake, esp. as bifurcated. मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. मेढा (p. 665) [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. मेढी (p. 665) [ mēḍhī ] f (Dim. of मेढ ) A small bifurcated stake: also a small stake, with or without furcation, used as a post to support a cross piece. मेढ्या (p. 665) [ mēḍhyā ] a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. मेढेजोशी (p. 665) [ mēḍhējōśī ] m A stake-जोशी ; a जोशी who keeps account of the तिथि &c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village.मेंधला (p. 665) [ mēndhalā ] m In architecture. A common term for the two upper arms of a double चौकठ (door-frame) connecting the two. Called also मेंढरी & घोडा . It answers to छिली the name of the two lower arms or connections. (Marathi)![]() Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE shows a gaNa, dwarf with tuft of hair in front, a unique tradition followed by Dikshitar in Chidambaram. The gaNa is next to the smelter kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' which is identified by the ekamukha sivalinga. mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). kharva is a dwarf; kharva is a nidhi of Kubera. karba'iron' (Tulu) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/09/indus-script-corpora-muha-metal-from.html

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE shows a gaNa, dwarf with tuft of hair in front, a unique tradition followed by Dikshitar in Chidambaram. The gaNa is next to the smelter kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' which is identified by the ekamukha sivalinga. mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). kharva is a dwarf; kharva is a nidhi of Kubera. karba'iron' (Tulu) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/09/indus-script-corpora-muha-metal-from.html![]()

![]()

Worship of linga by Gandharva, Shunga period (ca. 2nd cent. BCE), ACCN 3625, Mathura Museum. Worship signified by dwarfs, Gaṇa (hence Gaṇeśa = Gaṇa + īśa).

![]()

यष्टि 1 [p=840,3] f. (for 2. » [p= 848,3]) sacrificing Pa1n2. 3-3 , 110 Sch. (prob. w.r. for इष्टि).यष्टि 2 [p=848,3]n. (only L. )or f. (also यष्टी cf. g. बह्व्-ादि ; prob. fr. √ यछ् = यम् ; for 1. यष्टि » [p=840,3]) " any support " , a staff , stick , wand , rod , mace , club , cudgel; pole , pillar , perch S3Br. &c; a flag-staff (» ध्वज-य्°; a stalk , stem , branch , twig Hariv. Ka1v.

ஈட்டி īṭṭi, n. cf. yaṣṭi. [T. īṭe, K. īṭi, M. īṭṭi.] 1. Lance, spear, pike; குந்தம். செறியிலை யீட்டியும் (பரிபா. 5, 66). 2. Black wood. See தோதகத்தி. (L .)

इष्टि 1 [p=169,1] f. impulse , acceleration , hurry; despatch RV.f. seeking , going after RV.f. sacrificing , sacrifice.

ఇటిక (p. 0134) [ iṭika ] or ఇటికె or ఇటుక iṭika. [Tel.] n. Brick.ఇటికెలు కోయు or ఇటుకచేయు to make bricks. వెయ్యి యిటుక కాల్చిరి they burnt 1000 bricks. ఇష్టక (p. 0141) [ iṣṭaka ] ishṭaka. [Skt. derived from ఇటుక .] n. A brick. ఇటుక రాయి .इष्टका [p= 169,3] f. a brick in general; a brick used in building the sacrificial altar VS. AitBr. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r.Mr2icch. &c (Monier-Williams); iṣṭakā इष्टका [इष्-तकन् टाप् Uṇ.3.148] 1 A brick; Mk.3. -2 A brick used in preparing the sacrificial altar &c. लोकादिमग्निं तमुवाच तस्मै या इष्टकी यावतार्वा यथा वा Kaṭh.1.15. -Comp. -गृहम् a brick-house. -चयनम् collecting fire by means of a brick. -चित a. made of bricks; Dk.84; also इष्टकचित; cf. P.VI.3.35. -न्यासः laying the founda- tion of a house. -पथः a road made of bricks. -मात्रा size of the bricks. -राशिः a pile of bricks.इष्टिका iṣṭikā इष्टिका A brick &c.; see इष्टका. (Apte. Samskritam) íṣṭakā f. ʻ brick ʼ VS., iṣṭikā -- f. MBh., iṣṭā -- f. BHSk. [Av. ištya -- n. Mayrhofer EWA i 94 and 557 with lit. <-> Pk. has disyllabic iṭṭā -- and no aspiration like most Ind. lggs.]

Pa. iṭṭhakā -- f. ʻ burnt brick ʼ, Pk. iṭṭagā -- , iṭṭā -- f.; Kho. uṣṭū ʻ sun -- dried brick, large clod of earth ʼ (→ Phal.iṣṭūˊ m. NOPhal 27); L. iṭṭ, pl. iṭṭã f. ʻ brick ʼ, P. iṭṭ f., N. ĩṭ, A. iṭā, B. iṭ, ĩṭ, Or. iṭā, Bi. ī˜ṭ, ī˜ṭā, Mth. ī˜ṭā, Bhoj.ī˜ṭi , H. ī˜ṭh, īṭ, ī˜ṭ, īṭā f., G. ĩṭi f., M. īṭ, vīṭ f., Ko. īṭ f. -- Deriv. Pk. iṭṭāla -- n. ʻ piece of brick ʼ; B. iṭāl, °al ʻ brick ʼ, M. iṭhāḷ f. ʻ a piece of brick heated red over which buttermilk is poured to be flavoured ʼ. -- Si. uḷu ʻ tile ʼ seeuṭa -- .

*iṣṭakālaya -- .Addenda: íṣṭakā -- : S.kcch. eṭṭ f. ʻ brick ʼ, Garh. ī˜ṭ; -- Md. īṭ ʻ tile ʼ ← Ind. (cf. H. M. īṭ). *iṣṭakālaya ʻ brick -- mould ʼ. [íṣṭakā -- , ālaya -- ]

M. iṭāḷẽ n. (CDIAL 1600, 1601)

![]() A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal. The 'mukha' or face on the linga is a hieroglyph read rebus muh 'ingot'. Hieroglyph: mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) muhA 'the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace' (Santali. Campbell)

A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal. The 'mukha' or face on the linga is a hieroglyph read rebus muh 'ingot'. Hieroglyph: mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) muhA 'the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace' (Santali. Campbell)

Binjor seal with Indus Script deciphered. Binjor attests Vedic River Sarasvati as a Himalayan navigable channel en route to Persian Gulf

Naga worshippers of fiery pillar, Amaravati stup Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

![Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha, , Great Stupa of Amaravati]()

![]()

![]() Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha,

Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha,![20130501-075358.jpg]()

![2004092]()

![[prasati%2520mulawarman%255B3%255D.jpg]]() praśasti प्रशस्ति Yūpa यूप Indonesia:

praśasti प्रशस्ति Yūpa यूप Indonesia:

![]()

![]()

![*]()

![*]()

![]()

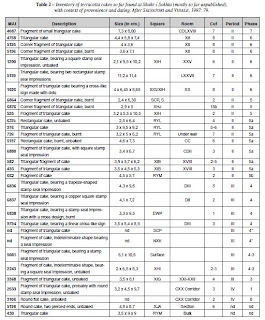

![]() Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)

Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)

![]() Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008).

Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008).

![]() Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls."

Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls."![]() Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.html

Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.html

![]() Harppa. Two sides of a fish-shaped, incised tablet with Indus writing. Hundreds of inscribed texts on tablets are repetitions; it is, therefore, unlikely that hundreds of such inscribed tablets just contained the same ‘names’ composed of just five ‘alphabets’ or ‘syllables’, even after the direction of writing is firmed up as from right to left.

Harppa. Two sides of a fish-shaped, incised tablet with Indus writing. Hundreds of inscribed texts on tablets are repetitions; it is, therefore, unlikely that hundreds of such inscribed tablets just contained the same ‘names’ composed of just five ‘alphabets’ or ‘syllables’, even after the direction of writing is firmed up as from right to left.

A remarkable discovery is the octoganal brick which is a yaṣṭi.in a fire-altar of Bijnor site on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati. Thi yaṣṭi attests to the continuum of the Vedic tradition of fire-altars venerating the yaṣṭi as a baton, skambha of divine authority which transforms mere stone and earth into metal ingots, a manifestation of the cosmic dance enacted in the furnace/smelter of a smith. Bhuteswar sculptural friezes provide evidence to reinforce this divine dispensation by describing the nature of the smelting process displaying a tree to signify kuTi rebus: kuThi 'smelter' with kharva 'dwarf' adorning the structure with a garland to signify kharva 'a nidhi or wealth' of Kubera. A Bhutesvar frieze also indicates the skambha with face signifying ekamukha linga rebus:

mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali).

Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭh

The fire altar, with a yasti made of an octagonal brick. Bijnor (4MSR) near Anupgarh, Rajasthan. Photo:Subhash Chandel, ASI

"(Archaeologist) Pandey said fire altars had been found in Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi, and the yastis were octagonal or cylindrical bricks. There were “signatures” indicating that worship of some kind had taken place at the fire altar here." http://www.frontline.in/arts-and-culture/heritage/harappan-surprise/article7053030.ece Amarendra Nath, archaeologist who excavated Rakhigarhi also noted: “Mature Period II is marked by a fortification wall and fire altars with yaSTi and yonipITha, with muSTikA offerings.”(Puratattgva: Bulletin of the Indian Archaeological Society 29 (1998-1999): 46-49).

Compare these 'shafts' in fire-altars with the pillars or cylindrical offering bases in Dholavira within an 8-shaped stone-wall enclosure:

Also comparable are the skambha pillar atop a smelter in Bhutesvar friezes:

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2).This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2).This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually  Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE shows a gaNa, dwarf with tuft of hair in front, a unique tradition followed by Dikshitar in Chidambaram. The gaNa is next to the smelter kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' which is identified by the ekamukha sivalinga. mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). kharva is a dwarf; kharva is a nidhi of Kubera. karba'iron' (Tulu) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/09/indus-script-corpora-muha-metal-from.html

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE shows a gaNa, dwarf with tuft of hair in front, a unique tradition followed by Dikshitar in Chidambaram. The gaNa is next to the smelter kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' which is identified by the ekamukha sivalinga. mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). kharva is a dwarf; kharva is a nidhi of Kubera. karba'iron' (Tulu) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/09/indus-script-corpora-muha-metal-from.html

Worship of linga by Gandharva, Shunga period (ca. 2nd cent. BCE), ACCN 3625, Mathura Museum. Worship signified by dwarfs, Gaṇa (hence Gaṇeśa = Gaṇa + īśa).

A tree associated with smelter and linga from Bhuteshwar, Mathura Museum.

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE. Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228).

In Atharva Veda stambha is a celestial scaffold, supporting the cosmos and material creation.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/12/skambha-sukta-atharva-veda-x-7-pair-of.html Full text of Atharva Veda ( X - 7,8) --- Stambha Suktam with translation (with variant pronunciation as skambha). See Annex A List of occurrences of gloss in Atharva Veda.

| avs.8.6 | [0800605] The black and hairy Asura, and Stambaja and Tundika, Arayas from this girl we drive, from bosom, waist, and parts below. |

Archaeological finds: cylindrical stele in Kalibangan, a pair of polished stone pillars in Dholavira, s'ivalinga in Harappa, Kalibangan

यष्टि 1 [p=840,3] f. (for 2. » [p= 848,3]) sacrificing Pa1n2. 3-3 , 110 Sch. (prob. w.r. for इष्टि).यष्टि 2 [p=848,3]n. (only L. )or f. (also यष्टी cf. g. बह्व्-ादि ; prob. fr. √ यछ् = यम् ; for 1. यष्टि » [p=840,3]) " any support " , a staff , stick , wand , rod , mace , club , cudgel; pole , pillar , perch S3Br. &c; a flag-staff (» ध्वज-य्°; a stalk , stem , branch , twig Hariv. Ka1v.

ஈட்டி īṭṭi, n. cf. yaṣṭi. [T. īṭe, K. īṭi, M. īṭṭi.] 1. Lance, spear, pike; குந்தம். செறியிலை யீட்டியும் (பரிபா. 5, 66). 2. Black wood. See தோதகத்தி. (

इष्टि 1 [p=169,1] f. impulse , acceleration , hurry; despatch RV.f. seeking , going after RV.f. sacrificing , sacrifice.

ఇటిక (p. 0134) [ iṭika ] or ఇటికె or ఇటుక iṭika. [Tel.] n. Brick.

*

M. iṭāḷẽ n. (CDIAL 1600, 1601)

shrI-sUktam of Rigveda explains the purport of the yaSTi to signify a baton of divine authority:

ArdrAm yaHkariNIm yaShTim suvarNAm padmamAlinIm |

sUryAm hiraNmayIm lakSmIm jAtavedo ma Avaha || 14

Trans. Oh, Ritual-fire, I pray you to invite shrI-devi to me, an alter-ego of everyone, who makes the environ holy let alone worship-environ, wielder of a baton symbolizing divine authority, brilliant in her hue, adorned with golden garlands, motivator of everybody to their respective duties like dawning sun, and who is manifestly self-resplendent in her mien.

Indus Script Corpora and archaeological excavations of 'fir-altars' provide evidence for continuity of Vedic religion of fire-worship in many sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization.

The metalwork catalogues of deciphered Indus Script Corpora are consistent with the fire-altars found in almost every single site of the civilization consistent with the documentation of yajna, fire-worship, in ancient texts of the Veda. The continuity of Vedic religion, veneration of Ruda-Siva among Bronze Age Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk' is firmly anchored.

kole.l signified 'smithy'. The same word kole.l also signified ' temple' (Kota)

In Hindu civilization tradition, yupa associated with smelter/furnace operations in fire-altars as evidenced in Bijnor, Kalibangan, Lothal and in many yupa pillars of Rajasthan of the historical periods, assume the aniconic form of linga venerated as Jyotirlinga, fierly pillars of light.

A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal. The 'mukha' or face on the linga is a hieroglyph read rebus muh 'ingot'. Hieroglyph: mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) muhA 'the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace' (Santali. Campbell)

A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal. The 'mukha' or face on the linga is a hieroglyph read rebus muh 'ingot'. Hieroglyph: mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) muhA 'the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace' (Santali. Campbell)"The worship of the lingam originated from the famous hymn in the Atharva-Veda Samhitâ sung in praise of the Yupa-Skambha, the sacrificial post. In that hymn, a description is found of the beginningless and endless Stambha or Skambha, and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. Just as the Yajna (sacrificial) fire, its smoke, ashes, and flames, the Soma , and the ox that used to carry on its back the wood for the Vedic sacrifice gave place to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted hair, his blue throat, and the riding on the bull of the Shiva, the Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga. In the text Linga Purana, the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories, meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the superiority of Shiva as Mahadeva. Jyotirlinga means "The Radiant sign of The Almighty". The Jyotirlingas are mentioned in the Shiva Purana." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shiva

Sources: Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157

Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions" The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda 4.

Pl. XXII B. Terracotta cake with incised figures on obverse and reverse, Harappan. On one side is a human figure wearing a head-dress having two horns and a plant in the centre; on the other side is an animal-headed human figure with another animal figure, the latter being dragged by the former.

Decipherment of hieroglyphs on the Kalibangan terracotta cake:

bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

koD 'horn' rebus: koD 'workshop'

kola 'tiger' rebus: kolle 'blacksmith', kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron'

Thus, the terracotta cake inscription signifies a iron workshop smelter/furnace and smithy.

The recording of an inscription on a terracotta cake used in a fire-altar continues as a tradition with inscriptions recorded on Yupa, 'pillars' of Rajasthan indicating the type of yajna's performed using those Yupa.

Binjor seal with Indus Script deciphered. Binjor attests Vedic River Sarasvati as a Himalayan navigable channel en route to Persian Gulf

![]()

The fire altar, with a yasti made of an octagonal brick. Photo:Subhash Chandel, ASI

Binjor seal

Binjor (4MSR) seal.Binjor Seal Text.Fish + scales, aya ã̄s (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. Vikalpa: badhoṛ ‘a species of fish with many bones’ (Santali) Rebus: baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali)

gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' Together with cognate ancu 'iron' the message is: native metal implements.

Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex reads: aya ancu khaNDa 'metallic iron alloy implements'.

koḍi ‘flag’ (Ta.)(DEDR 2049). Rebus 1: koḍ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi) Rebus 2: khŏḍ m. ‘pit’, khö̆ḍü f. ‘small pit’ (Kashmiri. CDIAL 3947)

The bird hieroglyph: karaḍa

करण्ड m. a sort of duck L. కారండవము (p. 0274) [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. (Telugu) karaṭa1 m. ʻ crow ʼ BhP., °aka -- m. lex. [Cf. karaṭu -- , karkaṭu -- m. ʻ Numidian crane ʼ, karēṭu -- , °ēṭavya -- , °ēḍuka -- m. lex., karaṇḍa2 -- m. ʻ duck ʼ lex: see kāraṇḍava -- ]Pk. karaḍa -- m. ʻ crow ʼ, °ḍā -- f. ʻ a partic. kind of bird ʼ; S. karaṛa -- ḍhī˜gu m. ʻ a very large aquatic bird ʼ; L. karṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ the common teal ʼ.(CDIAL 2787) Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'

Thus, the text of Indus Script inscription on the Binjor Seal reads: 'metallic iron alloy implements, hard alloy workshop' PLUSthe hieroglyphs of one-horned young bull PLUS standard device in front read rebus:

kõda 'young bull, bull-calf' rebus: kõdā 'to turn in a lathe'; kōnda 'engraver, lapidary'; kundār 'turner'.

Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ 'lathe'.(Gujarati) Rebus: sangara 'proclamation.Together, the message of the Binjor Seal with inscribed text is a proclamation, a metalwork catalogue (of) 'metallic iron alloy implements, hard alloy workshop'

करण्ड m. a sort of duck L. కారండవము (p. 0274) [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. (Telugu) karaṭa

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html

Yupa. Yupa from 4th century. Kutai Kingdom. Inscription in Samskritam.

Badwa Yupa. "It is one of the four places in Rajasthan where such inscribed stone pillars were erected during the third century CE. which signifies the revival of the Vedic religion. The Badva stone pillar inscription informs that the Maukharis performed a triratra sacrifice in CE. 239. It is probable that these Maukharis owed allegiance to the Malava Republic. Four pillars have been shifted to the State Archaeology Museum at Kota and only one remains at the site." http://asijaipurcircle.com/badva_baran.php#

"

![[prasati%2520mulawarman%255B3%255D.jpg]](http://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-L7CZvk8_Iys/ToIb1RXc2QI/AAAAAAAAAR0/aPzxQNQq0Tg/s1600/prasati%252520mulawarman%25255B3%25255D.jpg) praśasti प्रशस्ति Yūpa यूप Indonesia:

praśasti प्रशस्ति Yūpa यूप Indonesia:kuṇḍuṅgasya mahātmanaḥ;

putro śvavarmmo vikhyātah;

vaṅśakarttā yathāṅśumān;

tasya putrā mahātmānaḥ;

trayas traya ivāgnayaḥ;

teṣān trayāṇām pravaraḥ;

tapo-bala-damānvitaḥ;

śrī mūlavarmmā rājendro;

yaṣṭvā bahusuvarṇnakam;

tasya yajñasya yūpo ‘yam;

dvijendrais samprakalpitaḥ.

Yupa Inscriptions The Kutei Stone

.jpg)

.jpg)

YUPA PILLARS IN BICHPURIA TEMPLE

"The inscribed stone is a sacrificial pillar, commemorating revival of the rituals during third century A.D. by the Malava Republic. The inscription records the erection of the pillar by Ahisarman, son of Dharaka who was Agnihotri. Ahisarman seems to be a Malava chief.."

“…Malavas, Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas, Rajanyas etc...seem to have been patrons of Vedic sacrifices and rituals. Rajasthan witnessed the revival of Vedic religion under these people in the early centuries of the Common era and thus it was natural to get the largest number of inscribed yupa pillars (sacrificial posts) in various parts of Rajasthan. Dr. Satya Prakash discovered as early as in 1952, a yupa pillar inscribed in Brahmi script and dated Krita (Vikram) Samvat 321 (CD 264) from the village Bichpuria near Nagar (district Tonk) which records the performance of some sacrifice (name not specified) by Dharaka, who is styled as agnihotri. He brought to light this important epigraph and edited the same (Maru Bharti, Pilani, Vol. I, No. 2, February 1953). Rajasthan has provided the largest number of yupa pillars in the country of SaSthi-rAtra sacrifice, two pillars (now in Amber Museum) from Barnala (Jaipur) dated v.s. 284 (CE 227) recording the installation of seven yupa pillars by Vardhana and the second dated v.s. 335 (CE 278) referring to the TrirAtra sacrifice, four yupa pillars from Badva (now in Kotah Museum) three of them of the Maukhari dynasty ruling the area. The three inscribed yupa pillars record the performance of TrirAtr yajnas by Balavardhana, Somadeva and Bala Singh, the three sons of the commander-in-chief of the Maukhari kings. Each of them gave one hundred cows in gift on the occasion and installed sacrificial posts. The undated pillar belongs to DhanutrAta of the same dynasty who is credited with the performance of the AstoyAma yajna and putting up a yupa pillar in commemoration thereof. Sri ViSNuvardhana, son of the celebrated Yas'ovarman, performed puNdarIka yajna in the Malava era 428 (CE 371) and installed a yupa pillar at Vijaigarh (Bayana in Bharatpur region). Dr. Prakash studied in detail these incontrovertible evidences in his interesting paper 'Yupa pillars of Rajasthan' (JRIHR, Vol. IV, No. 2, April-June 1968) and evaluated their contribution in Rajasthan Through the Ages (Vol. 1, Chapter IV, 1966).” (Sharma, RG, 'History and Culture' in: Vijai Shankar Srivastava, ed., Abhinav Publications, 1981, Cultural Contours of India: Dr Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume, pp.81-82).

“The new light that the excavations at Kalibangan have shed on the religious aspects are discovery of the 'fire-places' and the terracotta cakes...The oval fire pits were observed as early as 1960-61, but these could not be then properly understood. Their importance was realised in the subsequent field-seasons. The occurrence of oval, round or rectangular 'fire-altars' has been observed on all the three mounds at Kalibangan in the Harappan context. On the western mound (KLB-1) over a platform was found a rectangular 'fire-altar' of baked bricks. It contained the 'bones of a bovine and antlers, representing perhaps a sacrifice'. Atop another platform were unearthed a row of seven rectangular mud enclosures with varying sizes approximately 50x45 cm, with walls about 10 cm high from the ground surface. These lay by the side of a well. In the centre of each enclosure was placed a cylindrical terracotta phallus-like object. 'The remains of th fire are indicated by ash. The walls of these enclosures are also burnt. All these 'fire-altars' were situated in a room. In the 'city mound' (KLB-2) a room almost in every house contained such fire-altars and they continued to occur in successive levels (Pl. XX, A in Ind. Arch. 1963-64—A review). A shallow pit, oval or rectangular in shape was first excavated. In this pit fire was made and in the centre a cylindrical sun-dried or pre-fired rectangular block or baked brick was fixed. The presene of charcoal lumps suggest that the fire was 'put out in situ'. The occurrence of the triangular or circular terracotta cakes, in these 'fire-altars', suggests that these were used as offerings, baked or unbaked. About the 'fire-altars' found in the citadel-complex it has been suggested that these may have been used for ongregational rituals, whereas in the 'city mound' these were for the individuals. The low mound (KLB-3) towards the eas of the 'city mound', has laid bare very significant data about the religion. This mound is not a habitation site. Here the remains of a huge mud-brick structure, possibly enclosing a smaller one, have come to light. Within this inner structure are several 'fire-altars' containing terracotta cakes, ash and the cylindrical objects. The circumstantial and environmental evidences added together suggest that this low mound is exclusively of religious significance where a temporal edifice existed, which, however, stratigraphically has been equated with the Harappan habitational phase at the site. The cylindrical columns are rectangular, round or fluted. The complete specimens on average are 20-25 cm. High. The terracotta cakes of several forms have been found at the site. But as pointed out earlier only the triangular or discular types have been found in the 'fire-altars'. It may not be out of place to mention that both at Bara and Chandigarh, phallus-shaped rectangular but slightly tapering terracotta objects have been recovered. These, of course, have no association with 'fire-altars' or terracotta cakes. In the light of evidence from Kalibangan and Lothal, it may be surmised that they are aniconic representations of S'iva, as we have today. This tends to be a mutually corroborative phenomenon at these sites which are more or less contemporary. The triangular terracotta cakes had been reported from Mohenjodaro and Harappa. Their proper significance was evaded, for want of a convincing explanation, by a passing remark that these may have some ritualistic use. This glib remark has, of late, come true. On one side is a human figure wearing a head-dress having two horns and a plant in the centre; on the other side is an animal-headed human figure with another animal figure, the latter being dragged by the former. The horned head-gear reminds of the horned deity on the Mohenjodaro seal and the other motif seems to have little significance without the religious affiliation...The cylindrical objects in the 'fire-altars' found at Kalibangan may have been aniconic representation of S'iva. Their association with fire may suggest the earlier manifestation of Jyotirlinga. Agarwala has pointed out that Rudra himself is the Fire-God. He has further elucidated that water and fire are the two parents of the universe – water being the female and fire the male form respectively. It is very interesting to note that in such 'fire-altars' lumps of charcoal have been discovered which are the outcome of the putting out in situ of the blazing embers. It is difficult to deny that these burning pieces of charcoal were extinguished with the use of water as a part of the ritual. If this is true, then we have at Kalibangan the elements of Purusha and Prakriti. As shown by Agarwala, with which the present writer concurs, the cylindrical objects and fire represent the male element (what in later days is reognised as Jyotirlinga) and water represents the female element. This also explains the absense of the terracotta female figurines representing the earth or mother-goddess at Kalibangan, Banawali (Haryana) and Lothal (Gujarat). At both Kalibangan and Lothal, the 'fire-altrs' with their contents described above have been found. Broadly speaking the religious beliefs of the Harappans through both time and space do not differ much as revealed by their homogeneous remains. But local variations did exist as discussed above. Certain new features have also come to light regarding the funerary customs both at Kalibangan and Lothal, which differ from those at other sites. It seems the strong strains of local elements could not be subduded and were rather adopted by the Harappans.” (JS Nigam, 'The religion of the Harapans in Rajasthan' in: Vijai Shankar Srivastava, ed., Abhinav Publications, 1981, Cultural Contours of India: Dr Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume, p.33-34).

Kalibangan. Fire-altar with stele 'linga' and terracotta cakes. Plate XXA. "Within one of the rooms of amost each house was found the curious 'fire-altar', sometimes also in successive levels, indicating their recurrent function." (p.31)

Shahr-i Sokhta, terracotta cakes, Periods II and III, I, MAI 1026 (front and rear); 2. MAI 376 (front and rear); 3. MAI 9794 (3a, photograph of front and read; 3b, drawing -- After Fig. 12 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)

Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)

Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008) Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008).

Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)."Terracotta cakes. Variously called 'terracotta tablets', 'triangular plaques' or 'triangular terracotta cakes' these artifacts (fig. 12, tables 2 and 3), made of coarse chaff-tempered clay, are a very common find in several protohistoric sites of the Subcontinent from the late Regionalization Era (2800-2600 BCE) to the Localization Er (1900-1700 BCE). In this latter time0-span they frequently assume irregular round shapes, to finally retain the form of a lump of clay squeezed in the hand. Despite abudant and often unnecessary speculation, archaeological evidence demonstrates tht they were used in pyrotechnological activities, both in domestic and industrial contexts. The most likely hypothesis is tht these objets, in the common kitchen areas, were heated to boil water, and used as kiln setters in other contexts. Shahr-i Sokhta is the only site in the eastern Iranian plateau where such terracotta cakes, triangular or more rarely rectangular, are found in great quantity. Their use, perhaps by families or individuals having special ties with the Indus region, might have been part of simple domestic activities, but this conclusion is questioned by the fact that several terracotta cakes, at Shahr-i Sokhta, bear stamp seal impressions or other graphic signs (in more than 30% of the total cases). In many cases the actual impressions are poorly preserved, and require detailed study. Perhaps these objects used in some form of administrative practice. Although many specimens are fired or burnt, a small percentge of the 'cakes' found at Shahr-i Sokhta is unfired (table 2). On the other hand, their modification in the frame of one or more unknown semantic contexts is not unknown in the Indus valley. At Kalibangan (Haryana, India), for example, two terracotta cake fragments respectively bear a cluster of signs of the Indus writing system and a possible scene of animal sacrifice in front of a possible divinity. While a terracotta cake found at Chanhu-Daro (Sindh, Pakistan) bears a star-like design, anothr has three central depressions. The most important group of incised terracotta cakes comes from Lothal, where the record includes specimens with vertical strokes, central depressions, a V-shaped sign, a triangle, and a cross-like sign identical to those found at Shahr-i Sokhta. Tables 2 and 3 shows a complete inventory of these objects (most so far unpublished), their provenience and proposed dating, and finally summarize their frequencies across the Shahr-i Sokhta sequence. The data suggest that terracotta cakes are absent from Period I. This might be due to the very small amount of excavated deposits in the earliest settlement layers, but the almost total absence of terracotta cakes in layers dtable to phases 8-7, exposed in some extension both in the Eastern Residential Area and in the Centrl Quarter, is remarkable. The majority of the finds belong to Period II, phases 6 and 5 (mount together to about 60% of the cases). As the amount of sediments investigated for Period III in the settlement areas, for various reasons, is much less than what was done for Period II, the percentage of about 40% obtained for Period III (which, we believe, dates to the second hald of the 3rd millennium BCE) actually demonstrates that the use of terracotta cakes at Shahr-i Sokht continued to increase." (E. Cortesi, M. Tosi, A. Lazzari and M. Vidale, 2008, Cultural relationships beyond the Iranian plateau: the Helmand Civilization, Baluchistan and the Indus Valley in the 3rd millennium, pp. 17-18)

Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls."

Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls." Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.html

Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.htmlThese terracotta cakes are like Ancient Near East tokens used for accounting, as elaborated by Denise Schmandt-Besserat in her pioneering researches.

The context in which an incised terracotta cake was found at Kalibangan is instructive. I suggest that terracotta cakes were tokens to count the ingots produced in a 'fire-altar' and crucibles, by metallurgists of Sarasvati civilization. This system of incising is found in scores of miniature incised tablets of Harappa, incised with Indus writing. Some of these tablets are shaped like bun ingots, some are triangular and some are shaped like fish. Each shape should have had some semantic significance, e.g., fish may have connoted ayo 'fish' as a glyph; read rebus: ayas 'metal (alloy)'. A horned person on the Kalibangan terracotta cake described herein might have connoted: kōṭu 'horn'; rebus: खोट khōṭa 'A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit'; खोटसाळ khōṭasāḷa 'Alloyed--a metal'(Marathi) A stake associated with the fire-altar was ढांगर [ ḍhāṅgara ] n 'A stout stake or stick as a prop to a Vine or scandent shrub]' (Marathi); rebus:ḍhaṅgar 'smith' (Maithili. Hindi)

At Kalibangan, fire Vedic altars have been discovered, similar to those found at Lothal which S.R. Rao thinks could have served no other purpose than a ritualistic one.[18] These altars suggest fire worship or worship of Agni, the Hindu god of fire. It is the only Indus Valley Civilization site where there is no evidence to suggest the worship of the "mother goddess".

Within the fortified citadel complex, the southern half contained many (five or six) raised platforms of mud bricks, mutually separated by corridors. Stairs were attached to these platforms. Vandalism of these platforms by brick robbers makes it difficult to reconstruct the original shape of structures above them but unmistakable remnants of rectangular or oval kuṇḍas or fire-pits of burnt bricks for Vedi (altar)s have been found, with a yūpa or sacrificial post (cylindrical or with rectangular cross-section, sometimes bricks were laid upon each other to construct such a post) in the middle of each kuṇḍa and sacrificial terracotta cakes (piṇḍa) in all these fire-pits. Houses in the lower town also contain similar altars. Burnt charcoals have been found in these fire-pits. The structure of these fire-altars is reminiscent of (Vedic) fire-altars, but the analogy may be coincidental, and these altars are perhaps intended for some specific (perhaps religious) purpose by the community as a whole. In some fire-altars remnants of animals have been found, which suggest a possibility of animal-sacrifice." Source: Elements of Indian Archaeology (Bharatiya Puratatva,in Hindi) by Shri Krishna Ojha, published by Research Publications in Social Sciences, 2/44 Ansari Riad, Daryaganj, New Delhi-2, pp.119-120. (The fifth chapter summarizes the excavation report of Kalibangan in 11 pages).

Tu. kandůka, kandaka ditch, trench. Te. kandakamu id. Konḍa kanda trench made as a fireplace during weddings. Pe. kanda fire trench. Kui kanda small trench for fireplace. Malt. kandri a pit. (DEDR 1214)

Ka. kunda a pillar of bricks, etc. Tu. kunda pillar, post. Te. kunda id. Malt.

kunda block, log. ? Cf. Ta. kantu pillar, post. (DEDR 1723)

kándu f. ʻ iron pot ʼ Suśr., °uka -- m. ʻ saucepan ʼ.Pk. kaṁdu -- , kaṁḍu -- m.f. ʻ cooking pot ʼ; K. kō̃da f. ʻ potter's kiln, lime or brick kiln ʼ; -- ext. with -- ḍa -- : K. kã̄dur m. ʻ oven ʼ. -- Deriv. Pk.kaṁḍua -- ʻ sweetseller ʼ (< *kānduka -- ?); H. kã̄dū m. ʻ a caste that makes sweetmeats ʼ. (CDIAL 2726) *kandukara ʻ worker with pans ʼ. [kándu -- , kará -- 1]

K. kã̄dar, kã̄duru dat. °daris m. ʻ baker ʼ.(CDIAL 2728)

Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans,metal-