Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/qetwb4l

I submit that Atharva Veda Skambha Sukta provides the AdhyAtmikA elaboration of the skambha as the axis mundi and the very embodiment of light in creation and all life-activities like the ones signified on Indus Script Corpora including Dholavira Signboard, two skambhas of Dholavira and six sivalingas of Harappa.

"...Chapter 5. Abyaktalingalakshana. The dimensions of the 'ummanifest (avyakta) lingas, i.e. those made of stone and other materials. Here the word linga is used in the general sense of symbol of Siva and NOT in the sense of 'phallus' See Brunner 1965,p.325." (Contents of the Pratishthalakshanasaarasamuccaya PLSS with 32 chapters cited in: compilation of Two manuscripts of the PLSS by Gudrun Buhnemann. 2003, India books, Varanasi, p. 11).

I submit that the two skambha of Dholavira have to be viewed in the context of related archaeo-architectural artefacts.

An observer standing in the middle of the two skambhas sees an 8-shaped ring of stones at a higher elevation, placed atop a pedestal.

The 8-shaped ring of stones is adjacent to another circle of stones. There is archaeological evidence that such circles of stones and 8-shaped rings of stone sometimes embedded with pillars like offering stands signify veneration of ancestors, pitr-s, departed aatman. Within the 8-shaped ring of stones two offering pedestals are seen.

The entire complex dominated by the two skambhas is accessible from two gateways: northern and eastern gateways and constitutes the center-piece of activities of the community in the settlement and could have been a ceremonial ground for community festivities as RS Bisht notes.

I submit that the two skambhas signify hieroglyph-multiplexes of the expression: dul meṛed, cast iron. This expression is contrasted with koṭe meṛed = forged iron (Mundari). The 8-shaped rings of stone and related architectural artefacts sigifies kole.l 'smithy' Rebus: kole.l 'temple'. A temple is a place where ancedstors, pitr-s are venerated. The products of the smithy are divine sparks from the khār- खार् - waṭh -वठ् । large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil or airaṇ 'anvil' in the smithy-forge.

The two skambhas signify an entry into the kole.l 'smithy-forge' where iron is cast by the artisans of Dholavira or Kotda. The metallurgical competence of Kotda or Dholavira artisans is signified by the monumental Signboard on the Northern Gateway. The decipherd Indus Script is clear and unambiguous.

The decipherment of lokhāṇḍā 'metal implements' signified by the Dholavira skambha (pillars of light) is consistent with the decipherment of Dholavira signboard as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork.

The signboard connotes in Meluhhaspeech (Pro-Prakritam language): Meluhha copper metalworking and lapidary (engraving, bead-making) complex of Bronze Age:

1. dhatu dul eraka 'mineral, cast (metal), molten cast copper

2.khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. aduru ‘native metal’ kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe' (engraving) eraka 'molten cast copper'

3. loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) eraka'molten cast copper'

1. dhatu dul eraka 'mineral, cast (metal), molten cast copper

2.khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. aduru ‘native metal’ kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe' (engraving) eraka 'molten cast copper'

3. loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) eraka'molten cast copper'

Sivalinga in Dholavira depicted as mēḍhī 'pillar, part of a stupa' (Pali. Marathi) Rebus:meḍ 'iron, metalwork, metal castings'

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.The expression dul m~r.he~t 'cast iron' is signified by a pair of pillars: dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

http://youtu.be/yurWejkT9Sc Entrance to Citadel, Dholavira

The concentric circles of timber posts found in Tarim Basin may also compare with concentric circles of stones found in Ukherda and Dholavira. See also polished stone pillars found in Dholavira and stone sivalinga found in Harappa.

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery.

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery. Barrow Cemetery in IndiaNear Nakhtarana in Kutch, Gujarat, there is a large cemetery and cremation ground called Ukherda by the locals. There are also ancient hero and Sati stones. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=26370

Barrow Cemetery in IndiaNear Nakhtarana in Kutch, Gujarat, there is a large cemetery and cremation ground called Ukherda by the locals. There are also ancient hero and Sati stones. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=26370

Remains of Circular hutments (?) joined in 8-shape with stone pillar fragments at the centre of each circle, close to the area where two polished stone pillars (sivalinga?) were found. Did these circular stone remnants, denote a smithy? In Kota language (Indian sprachbund, Mleccha-Meluhha) kole.l 'smithy, temple'.

The report on excavations 1989-2005 at Dholavira (RS Bisht 2015) is a celebration. 940 pages, 120MB, the full text of the draft report will be made available for those interested: email: kalyan97@gmail.com

http://asi.nic.in/pdf_data/dholavira_excavation_report_cover.pdf

Dholavira on the Rann of Kutch (as a Gateway into the Persian Gulf) in reference to the locus of maritime sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization

Dholavira location in the Gulf of Kutch and Interaction networks (After Kenoyer, harappa.com)

It is a celebration because it helps reconstruct the worship in Skambha (Siva) temple in Dholavira in the context of the decipherment of Indus Script Corpora and the Dholavira Signboard with hieroglyph-multiplexes rendered rebus-metonymy-layer in Meluhha (Proto-Prakritam). This note 1) identifies the pitr-s of present-day Bharatam Janam with roots found on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati; 2) outlines a lexis of Meluhha, the speechform of Proro-Prakritam spoken by the pitr-s; 3) delineates the life-activity of the pitr-s involved in metalwork and cire perdue metal casting of the Bronze Age along the Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa; and 4) reconstructs an expression of cultural orientations of Sarasvati's children with the worship of Skambha (Siva) temple, apart from the evidences of Sivalingas and Pillars (skambha) found in Harappa and Dholavira respectively.

The chalcolithic nature of the site and the reasons for comparison with arsenical-copper cire perdue artefacts of Nahal Mishmar are based on a remarkable find at Dholavira of a copper alloy fragment.

Copper alloy fragment from Dholavira (After Fig. 11.77 in RS Bisht, 2015, opcit., p.810. Preliminary analysis report of Dholavira copper objects by Sharada Srinivasan presented in 11.3 of the report. This follows the identification and analysis of stones and metals by Randall W. Law presented in Chapter 11.1 of the report.

"A metallic copper waste has been studied (29830, Fig. 11.89), as well as a pin fragment (29537, Fig. 11.90). Both samples contain much arsenic (from 1 to 3 wt%. Some nickel and iron are also systematically present, and in prill 29830 some cobalt was detected." (ibid., pp.823-824)

See: http://tinyurl.com/nbjro2v Excavations at Dholavira 1989-2005 (RS Bisht, 2015) Full text including scores of Indus inscriptions announced for the first time. Report validates Indus script cipher as layered rebus-metonymy.

In continuation of this validation, the Skambha (Siva) temple in Dholavira is identified in this note and compared with Ein Gedi chalcolithic temple, not far from Nahal Mishmar.

The roots of Hindu civilization are firmly anchored in archaeo-architectural and philological terms in the cultural artefacts revealed in archaeological excavations of sites most of which (about 80%) are on the bank of Vedic River Sarasvati in Northwest Bharatam. The philological terms are apparent from the stunning enquiry in 44 inquiries in Atharva Veda Skambha Sukta.

This note recreates the Skambha (Siva) temple in Dholavira based on these evidences. A striking feature is that the 8-shaped sanctum sanctorum is comparable to the architectural outline recreated in chalcolithic temple of Ein Gedi (explaining the context of Nahal Mishmar cire perdue alloy artefacts which also signify Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplexes of antelope, aquatic bird, frame of temple and procession standards).

General view of the Tumulus. Dholavira venerating the ancestors (pitr-s)(After Fig. 9.11 RS Bisht opcit.) This compares with the general view of Ein Gedi layout.

Chalcolithic Temple above spring and modern Kibbutz Ein Gedi

Chalcolithic Temple above spring and modern Kibbutz Ein Gedi Sceptre from the Nahal Mishmar hoard (replica)

Sceptre from the Nahal Mishmar hoard (replica)See: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00438243.1988.9980066 PRS Moorey, 1988, The chalcolithic hoard from Nahal Mishmar, Israel, in context, in: World Archaeology, Vol. 20, Issue 2, 188, pp. 171-189 "Abstract. The earlier fourth millennium BC hoard of over 400 copper objects and thirteen of other materials discovered in 1961 in a cave in the Nahal Mishmar, west of the Dead Sea in Israel, is of worldwide significance for the earliest history of copper metallurgy. This paper, in seeking to make the hoard's significance more explicit, argues that it is all the product of settlements in the northern Negev of Israel probably obtaining their copper from mines in the Wadi Feinan, Jordan. It may originally have come from a local temple treasury."

A 10-lettered signboard (?) found in the western chamber of North Gate of castle. c. 2500-1900 BCE (ASI)

After Fig. 8.287 In situ location of short cylindrical element of pillars (RS Bisht, opcit., p. 581)

Pillar members found from various trenches from Dholavira. (ASI website opcit.)

Drain to the west of the ceremonial ground (ASI)

Stone drain channel (After Figs. 8.300 to 8.302 RS Bisht opcit.)

North Gate of Castle. General View. Harappan period. c. 2500-1900 BCE (ASI)

North Gate of Castle. Harappan period c. 2500-1900 BCE (ASI)

General view of the eastern arm of fortification of Castle and the East Gate in the foreground. Harappan period. c. 2500-1900 BCE (ASI)

Southern chamber of East gate with pillar members in situ. Castle. Harappan period c. 2500-1900 BCE.

"Being one among the five largest Harappan cities in the subcontinent, Dholavira has yielded many firsts in respect of Indus civilization. Fourteen field seasons of excavation through an enormous deposit caused by the successive settlements at the site for over 1500 years during all through the 3rd millennium and unto the middle of the 2nd millennium BC have revealed seven significant cultural stages documenting the rise and fall of the Indus civilization in addition to bringing to light a major, a model city which is remarkable for its exquisite planning, monumental structures, aesthetic architecture, amazing water harvesting system and a variety in funerary architecture. It also enjoys the unique distinction of yielding an inscription made up of ten large-sized signs of the Indus script and, not less in importance, is the other find of a fragment of a large slab engraved with three large signs. This paper attempts to give an account of hydro-engineering that is manifest in the structures of the Harappans at Dholavira.

The ancient site at Dholavira (230 53' 10" N; 700 13'E), taluka Bhachau, district Kachchh in state Gujarat, lies in the island of Khadir which, it turn, is surrounded by the salt waste of the Great Rann of Kachchh. The ancient settlement is embraced by two monsoon channels, namely, the Manhar and Mansar. The ruins, including the cemetery covers an area of about 100 hectares half of which is appropriated by the articulately fortified settlement of the Harappans alone.The salient components of the full-grown cityscape consisted of a bipartite 'citadel', a 'middle town' and a 'lower town', two 'stadia', an 'annexe', a series of reservoirs all set within an enormous fortification running on all four sides. Interestingly, inside the city, too, there was an intricate system of fortifications. The city was, perhaps, configured like a large parallelogram boldly outlined by massive walls with their longer axis being from the east to west. On the bases of their relative location, planning, defences and architecture, the three principal divisions are designed tentatively as 'citadel', 'middle town', and 'lower town'....

The citadel at Dholavira, unlike its counterparts at Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Kalibangan but like that at Banawali, was laid out in the south of the city area. Like Kalibangan and Surkotada it had two conjoined subdivisions, tentatively christened at Dholavira as 'castle' and 'bailey', located on the east and west respectively, both are fortified ones. The former is the most zealously guarded by impregnable defences and aesthetically furnished with impressive gates, towers, salients and drainage. To the north of the citadel a broad and long ground, probably used for multiple purposes such as community gathering on festive or ceremonial occasions, a stadium and a marketing place for exchanging merchandise during trading seasons (s). Further north, there was laid out the enwalled middle town while to its east was founded the lower town. The last -mentioned one did not have an appurtenant fortification though, it was set within the general circumvallation....

| Sl. No. | Division | Width | Length | Ratio |

| 1 | City, internal | 616.87 | 711.10 | 4 : 5 |

| 2 | Castle, internal at available top | 92 | 114 | 4 : 5 |

| 3 | Castle, external (as per present exposure) | 118 | 151 | 4 : 5 |

| 4 | Citadel (castle + bailey), external approximately (including bastions) | 140 | 280 | 1 : 2 |

| 5 | Bailey, internal | 120 | 120 | 1 : 1 |

| 6 | Middle Town + Stadium, internal | 290.45 | 340.5 | 6 : 7 |

| 7 | Middle Town, excluding Stadium, internal | 242 | 340.5 | 5 : 7 |

| 8 | Stadium, internal | 47.5 | 283 | 1 : 6 |

| 9 | Lower Town, built-up area | 300 | 300 | 1 : 1 |

We may not be elaborating on the other gates in the city. However, the east gate of the great stadium and the similarly located gate of the middle town, both intercommunicating with the lower town, were also quite elaborate and impressive. Significantly, the west gate of the same stadium was connected with a long and broad corridor with a storm water drain running underneath. The late Harappans gate openings were simple and unpretentious. They were also however using many a Harappan gates.

Very likely, the north gate and also the east gate inter alia served the purpose of royal procession on occasions and the little stadium had a role in that too.

Mohenjodaro and Kalibangan have open space between citadel and lower town. At Harappa and Rakhigarhi, it lies to the east of citadel and north of lower town. Archaeologically speaking, no convincing proof of use(s) of such space has been put forward so far. Now, Dholavira can claim a solution to the riddle. It has shown up two such open grounds which should have been put to multipurpose uses such as community gathering on festive or special occasions, royal ceremonies, sports and entertainment and commercial activities during trading season. Propositions are based on their location, architectural specialties and antiquarian tidbits that were found in course of excavation. There are two such closed arenas. One, lying between citadel and middle town and being provided with two major gates, one on each on east and west, measured 283 m E-W and 45 to 47m N.S (ratio 6:1). It was also furnished with tiered, stepped or sloping stands on all four sides. For convenience, we may refer it as stadium or rather the great stadiums while the other one, far smaller is called the little stadium. The latter that was separated by massive stand from, but connected through an opening to, the former, lay right under the shadow of the pre-eminent castle onto which it abutted at the north-western corner. Both the stadia should have been used for some common as well as some separate function. To conclude, we may add that the great stadium is perhaps the largest in length while both are the earliest so far as archaeology has evidenced. " http://asi.nic.in/asi_exca_2007_dholavira.asp

After Fig. 8.304 RS Bisht opcit. Free standing columns in situ.

After Fig. 8.305 RS Bisht opcit. Details of free standing columns.

After Fig. 8.303 RS Bisht opcit. Free standing columns in situ.

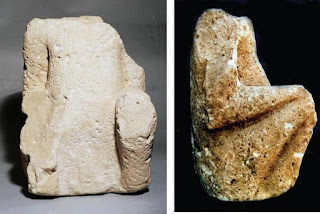

'Section 8.9.2.2 Free standing columns. At least six examples of freestanding columns were discovered from the excavations. These freestanding columns are tall and slender pillaqrs with circular cross-section and with a top resembling a phallus or they are phallic in nature. That is why most of them were found in an intentionally damaged and smashed condition. The phallus is depicted realistically with even the drawing of foreskin shown clearly. Two of these freestanding columns are found near eastern end of high street of Castle. These columns measure nearly 1.5 m in height and are found at the strategic location of entering into the high street from the east gate of Castle. These two columns are placed in such a manner at the beginning of high street that it divides the street into three equal parts. The other freestanding columns of the same variety and typology, numbering into four was found in a completely smashed and broken condition. Two of such columns were found in a secondary condition, fittes as a masonry subsequent structure. One such column was found embedded in a masonry of Tank A while the other one was found in a masonry in a later period structure near the western fortification of Castle. Two more examples, completely smashed and destroyed one were also found, one near the western end of Ceremonial Ground and the second one near the north gate of Castle. The destruction and desecration of these columns can be equated with that of the damage caused to the stone statue, which clearly indicates a change in ideology and traditions, customs after the Harappanphase. The exact nature of the two free standing columns to the east of high street is also not ascertainable and it is also difficult to determine whether they are in their primary or secondary context. Interestingly, all these stone columns have a roughened and irregularly chipped bottom which is a clear indication of burying them up to the irregular portion so that polished and highly finished upper portion can remain above the ground." (RS Bisht, opcit., pp.589-591)

"8.9.3 Stone statue. The Dholavira statue is perhaps the largest that Harappans ever attempted. It was found placed upside down as a building block of a wall that was raised by the late Harappans to retain the tilting and bulging northern wall of the passageway of east gate of Castle. It is made of porous limy sandstone with weak matrix. It was in a seating position with a flat base, arms resting on the knees, with both the knees drawn up and kept apart as if to show the genitals as the sculpture has shown no feature of clothing. The statue depicts a male individual and its execution is close to realistic. The belly is shown protruding. The rear portion of the statue also shows evidence of depiction of hair lots falling down, which is also damaged. It was certainly vandalised, possibly just like all the statues, which were found in Mohenjo-daro. The genitals were intentionally rubbed off and damaged. A mould was prepared of this tatue and a cast was prepared which clearly indicated the closure details of even the genitals. It also clearly indicated the rubbing off of the genitals intentionally while the other details of genitals were clearly visible. It suggests that it was related to phallus worship, which is nicely corroborated by quite a few finials of pillars with carving in the shape of phallus." (RS Bisht, opcit., pp. 591-592)

Seated posture of a 'priest' signified by this stone image is comparable to other artefacts of the civilization.

Mohenjo-daro, Seated male figure with head missing. On the back of the figure, the hair style can be partially reconstructed by a wide swath of hair and a braided lock of hair. A cloak is draped over the edge of the left shoulder and covers the folded legs and lower body, leaving the right shoulder and chest bare. The left arm is clasping the left knee and the hand is visible peeking out from underneath the cloak. The right hand is resting on the right knee which is folded beneath the body.

Mohenjo-daro, Seated male figure with head missing. On the back of the figure, the hair style can be partially reconstructed by a wide swath of hair and a braided lock of hair. A cloak is draped over the edge of the left shoulder and covers the folded legs and lower body, leaving the right shoulder and chest bare. The left arm is clasping the left knee and the hand is visible peeking out from underneath the cloak. The right hand is resting on the right knee which is folded beneath the body.

harappa.com One ancient priest is called PotR 'purifier' The cognate glosses also refer to an ancestral figure, a grandfather,a venerated person. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/dotted-circle-fillet-trefoil-robe.html पोतृ pōtṛ " Purifier " , Name of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman (Rigveda) pōtrá

harappa.com One ancient priest is called PotR 'purifier' The cognate glosses also refer to an ancestral figure, a grandfather,a venerated person. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/dotted-circle-fillet-trefoil-robe.html पोतृ pōtṛ " Purifier " , Name of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman (Rigveda) pōtráபோத்தி pōtti , n. < போற்றி. 1. Grandfather; பாட்டன். Tinn. 2. Brahman temple- priest in Malabar; மலையாளத்திலுள்ள கோயிலருச் சகன். पोतृ [p= 650,1] प्/ओतृ or पोतृ, m. " Purifier " , N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman ; = यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि Sa1y. ) RV. Br. S3rS. Hariv.

Like TA Gopinatha Rao, RS Bisht has erred in jumping to the suggestion of 'phallus worship' based on the iconograhic analyses presented.

I submit that an alternative explanation is offered by the Candi Sukuh evidence of the rebus reading of the hieroglyph-multiplexes as lokhāṇḍā 'metal implements'. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/09/cipher-of-indus-script-corpora-explains.html

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/dholavira-1-signboard-and-2-stone.html

The signboard deciphered in three segments from r.

ḍato ‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍaren lid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼ Rebus:kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara— m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaḍha 'ficus religiosa' (Skt.); kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

khuṇṭa 'peg’; khũṭi = pin (M.) rebus: kuṭi= furnace (Santali) kūṭa ‘workshop’ kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

Dholavira Signboard inscription of gypsum inlays on wood measures 3 m. long. Each of the 10 signs is 37 cm. high and 25 to 27 cm. wide and made of pieces of white gypsum inlays; the signs were apparently inlaid in a wooden plank. The conjecture is that this wooden plank was mounted on the Northern Gateway as a Signboard.

Dholavira Signboard

The Signboard which adorned the Northern Gateway of the citadel of Dholavira was an announcement of the metalwork repertoire of dhokra kamar, cire perdue metalcasters and other smiths working with metal alloys. The entire Indus Script Corpora are veritable metalwork catalogs. The phrase dhokra kamar is rendered on a tablet discovered at Dholavira presented in this monograph (earlier discussed at

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-1-dhokra-lost-wax.html ). The 10-hieroglyph inscription of Dholavira Signboard has been read rebus and presented at

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/dholavira-gateway-to-meluhha-gateway-to.html

Excerpts from Excavation Report on Dholavira released by ASI in 2015:

"8.1 Inscriptions. Literacy of the Harappans is best exemplified in their inscriptions written in a script that is unparalleled in its characters hitherto unknown and undeciphered so far. These inscriptions are best represented on their seals and seals-impressions in addition to those engraved or painted on the objects of metal, terracotta, pottery, faience, ivory, bone and stone, albeit sometimes appearing in a single sign inscription or scratching particularly on pottery or terracotta objects. 8.1.1 Signboard. One of the most prominent discoveries from the excavations at Dholavira is the find of a 10 large sized signboard presently lying in the western chamber of North Gate. This inscription was found lying in the western chamber of north gate, and the nature of find indicates that it could have been fitted on a wooden signboard, most probably fitted above the lintel of the central passageway of the gate. The central passageway of north gate itself measures 3.5 m in width and the length of the inscription along with the wooden frame impression is also more or less same thereby indicating the probable location. The inscription consists of 10 large-sized letters of the typical Harappan script, and is actually gypsum inlays cut into various sizes and shapes, which were utilized to create each size as, indicated above. The exact meaning of the inscription is not known in the absence of decipherment of script." (pp.227-229, Section 8.1.1 Signboard)

"The central passageway of north gate itself measures 3.5 m in width and the length of the inscription along with the wooden frame impression is also more or less same thereby indicating the probable location. The inscription consists of 10 large-sized letters of the typical Harappan script, and is actually gypsum inlays cut into various sizes and shapes, which were utilized to create each size as, indicated above. The exact meaning of the inscription is not known in the absence of decipherment of the script. (p.231)

Fig. 8.2: Location of ten large sized inscription in North Gate

Fig. 8.3: Close-up of inscription

Fig. 8.4: Drawing showing the ten letters of inscription

Fig. 8.5: Photograph showing the details of inscription in situ.

Fig. 8.6: Close-up of some of the letters from the inscription

Fig. 8.7: Gypsum inlays used for the inscription

"The stone block is badly eroded and peeling off in layers could be noticed. The inscription consists of four letters partially preserved due to the eroding nature of the stone. As the stone member was found fixed in masonry of the square underground chambers, it can be deduced that it could have been damaged and hence used as part of a masonry as its original meaning might have been lost. The extant length of the inscription is 16.5 cm while the width is 8 cm. The inscription consists of four letters, while three letters are clearly visible, the fourth one towards the left end is not clearly visible." (p.230, Section 8.1.2 Inscription on a stone block) This stone block was found at the southern portion of Bailey. "The inscription was found on the shorter face of a portion of what could be a larger rectangular slab, originally a lintel of a doorway." (p.229)

Fig. 8.8: Inscription on a stone block from Bailey, Dholavira.

The cumulative readings of inscriptions found in Dholavira and in the entire Indus Script Corpora -- which constitute a catalogus catalogorum of metalwork by Meluhha-Mleccha artisans -- attest to the possible role of Signboard and Stone inscriptions as Dwaraka (gateway) of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization announcing to seafaring merchants from Ancient Near East the competence of dhokra kamar artisans of ancient Bharatam Janam. The glosses realized to denote the hieroglyphs and their rebus-metonymy layered renderings point to the lexical repertoire of the artisans denoting Meluhha/Mleccha parole as Prakritam of Indian sprachbund.

Dholavira Stone inscription measures 16.5 cm l. x 8 cm.w. The inscription is deciphered as metalwork catalog:

1. Hieroglyph: aduru 'harrow' rebus: aduru 'native metal';

2. Hieroglyph: kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze';

3. Hieroglyph: eraka 'nave of wheel'āra 'spoke' Rebus: eraka 'molten cast' (Tulu); arka 'copper' (Samskritam) ara 'brass'.ārakUTa id. (Samskritam) 4.Hieroglpy ligature: A spoked wheel is ligatured within a rhombus: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast'

See:

1. https://www.academia.edu/12012020/Excavations_at_Dholavira_1989-2005_RS_Bisht_2015_Full_text_including_scores_of_Indus_inscriptions_announced_for_the_first_time._Report_validates_Indus_script_cipher_as_layered_rebus-metonymy

Hieroglyphs on Dholavira stone inscription (four hieroglyphs from r.)

Hieroglyph: aḍar ‘harrow’Rebus: Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron.(DEDR 192)

kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

The fourth sign can be compared with the ligatured hieroglyph inscribed on a Rakhigarhi lead ingot.

Hieroglpy ligature: A spoked wheel is ligatured within a rhombus: kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast'

A ‘harrow’ hieroglyph is shown on one of the two seals found at Altyn-depe (Excavation 9 and 7) found in the shrine and in the 'elite quarter’.( Masson, VM, Seals of a Proto-Indian Type from Altyn-depe, pp. 149-162; V.M. Masson, Urban Centers of Early Class Society, pp. 135-148; I.N. Khlopin, The Early bronze age cemetery in Parkhai II: The first two seasons of excavations, 1977-78, pp. 3-34 in: Philip L. Kohl (ed.), 1981, The Bronze Age Civilization in Central Asia, Armonk, NY, ME Sharpe, Inc.)

The hieroglyphs on Altyn-depe seals have been read using rebus-metonymy layere cipher in Meluhha:aḍar ‘harrow’; aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali); rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Te.) sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) svastikā sign Rebus: Kashmiri: zasath ज़स््थ् or zasuth ज़सुथ् । त्रपु m. (sg. dat.zastas ज़स्तस्), zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast). jasti jasti; त्रपुधातुविशेषनिर्मितम् adj. c.g. made of zinc or pewter. jasthजस्थ । त्रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas जस्तस्), zinc, spelter; pewter. jastuvu जस्तुवु त्रपूद्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter. Thus, the three hieroglyphs of Altyn Depe seals refer to jastuvu 'zinc' (for zinc-copper alloy of bronze), aduru 'native metal' (unalloyed) and kolmo 'smithy'. Alternative vernacular forms of 'zinc' in Indian sprachbund: satthiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus satthiya, jasta 'zinc' (Kashmiri. Kannada); sattva 'zinc' (Prakrit).

Hieroglyph: aḍar ‘harrow’ Rebus: aduru = gaṇiyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Tamil); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Malayalam) Kurku.adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Maltese. adru broken grain (DEDR 134).

Alternative: H. dãtāwlī f. ʻ rake, harrow ʼ. (CDIAL 6162). Ku. danīṛo m. ʻ harrow ʼ; N. dãde ʻ toothed ʼ sb. ʻ harrow ʼ; A. dãtīyā ʻ having new teeth in place of the first ʼ, dãtinī ʻ woman with projecting teeth ʼ; Or. dāntiā ʻ toothed ʼ; H. dãtī f. ʻ harrow ʼ; G. dã̄tiyɔ m. ʻ semicircular comb ʼ, dãtiyɔ m. ʻ harrow ʼ. (CDIAL 6163). G. dã̄tɔ m. ʻ a kind of rake or harrow ʼ(CDIAL 6153). Pk. daṁtāla -- m., °lī -- f. ʻ grass -- cutting instrument ʼ; S. ḍ̠andārī f. ʻ rake ʼ, L. (Ju.) ḍ̠ãdāl m., °lī f.; Ku. danyālo m. ʻharrowʼ danyāw (y from danīṛo < dantín -- ); N.dãtār ʻ tusked ʼ (← a Bi. form); A. dãtāl adj. ʻ tusked ʼ, sb. ʻ spade ʼ; B. dãtāl ʻ toothed ʼ; G. dãtāḷ n., °ḷī f. ʻ harrow ʼ; M. dã̄tāḷ ʻ having projecting teeth ʼ, dã̄tāḷ, °ḷē, dãtāḷ n. ʻ harrow, rake ʼ.Garh. dãdāḷu ʻ forked implement ʼ, Brj. dãtāl, dãtāro ʻ toothed ʼ, m. ʻ elephant ʼ. (CDIAL 6160). On a Mohenjo-daro seal, ayo 'fish' read rebus ayas 'metal'; Allograph: ḍangar 'bull' Rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith' (Hindi) ṭhākur ʻblacksmithʼ (Maithili) Rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

Alternative: H. dãtāwlī f. ʻ rake, harrow ʼ. (CDIAL 6162). Ku. danīṛo m. ʻ harrow ʼ; N. dãde ʻ toothed ʼ sb. ʻ harrow ʼ; A. dãtīyā ʻ having new teeth in place of the first ʼ, dãtinī ʻ woman with projecting teeth ʼ; Or. dāntiā ʻ toothed ʼ; H. dãtī f. ʻ harrow ʼ; G. dã̄tiyɔ m. ʻ semicircular comb ʼ, dãtiyɔ m. ʻ harrow ʼ. (CDIAL 6163). G. dã̄tɔ m. ʻ a kind of rake or harrow ʼ(CDIAL 6153). Pk. daṁtāla -- m., °lī -- f. ʻ grass -- cutting instrument ʼ; S. ḍ̠andārī f. ʻ rake ʼ, L. (Ju.) ḍ̠ãdāl m., °lī f.; Ku. danyālo m. ʻharrowʼ danyāw (y from danīṛo < dantín -- ); N.dãtār ʻ tusked ʼ (← a Bi. form); A. dãtāl adj. ʻ tusked ʼ, sb. ʻ spade ʼ; B. dãtāl ʻ toothed ʼ; G. dãtāḷ n., °ḷī f. ʻ harrow ʼ; M. dã̄tāḷ ʻ having projecting teeth ʼ, dã̄tāḷ, °ḷē, dãtāḷ n. ʻ harrow, rake ʼ.Garh. dãdāḷu ʻ forked implement ʼ, Brj. dãtāl, dãtāro ʻ toothed ʼ, m. ʻ elephant ʼ. (CDIAL 6160). On a Mohenjo-daro seal, ayo 'fish' read rebus ayas 'metal'; Allograph: ḍangar 'bull' Rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith' (Hindi) ṭhākur ʻblacksmithʼ (Maithili) Rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

The name of the Dholavira village is koTDa. Sign 244 and variants could be a representation of a warehouse (granary) with three rows of pillars to hold storage planks to stock metal/stone artefacts. See the photos of a number of warehouses in Harappa; and of what is called a "granary room" in Mohenjodaro. These structures compare with the Sign 244. These structural remains have also been interpreted by many archaeologists as a granary.

Dholavira. gateway. A designer's impressions (reconstruction) of the world's first signboard on the gateway of fortification or citadel.

Dholavira (Kotda) on Kadir island, Kutch, Gujarat; 10 signs inscription found near the western chamber of the northern gate of the citadel high mound (Bisht, 1991: 81, Pl. IX); each sign is 37 cm. high and 25 to 27 cm. wide and made of pieces of white crystalline rock; the signs were apparently inlaid in a wooden plank ca. 3 m. long; maybe, the plank was mounted on the facade of the gate to command the view of the entire cityscape. Ten signs are read from left to right. The 'spoked circle' sign seems to be the divider of the three-part message. (Bisht, R.S., 1991, Dholavira: a new horizon of the Indus Civilization. Puratattva, Bulletin of Indian Archaeological Society, 20: 81; now also Parpola 1994: 113).

This first sign board of the world verily constitutes the Bronze Age Standard of Eurasia -- not merely a Meluhha Standard.Ancient Near East Bronze Age Meluhha, smithy/lapidary documents, takṣat vāk, incised speech [Evidence from sites surrounding Bhuj in Kutch: Kanmer, Dholavira, Gola Dhoro (Bagasra), Shikarpur, Khirsara, Surkotada, Desalpur, Konda Bhadli, Juni Kuran, Narapa]

The Northern Gateway signboard has invited visiting seafaring merchants into a Bronze Age smithy-forge complex. The centre-piece is the ceremonial stadium which displays the artifacts of metallurgical competence of Dholavira or Kotda artisans. The two skambhas and the entry into the pedestal with the kole.l 'temple' which is also a 'smithy-forge' is a celebration of the production of alloys of metal and castings of metalwork.

The skambhas as sivalinga are like the ekamukha linga on Bhuteswar and Mathura sculptural friezes the lokhāṇḍā 'metal implements' and dul meṛed, 'cast iron' inviting the visiting seafaring merchants into kole.l 'temple' which is kole.l 'smithy-forge' with a kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'.

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CEThese pillars evoke the imageries of a festival which is celebrated even today by Lingavantas, particularly in Karnataka.

These pillars at Dholavira could be a depiction of pillars of flame as Sivalinga.

Etyma from Meluhha (Mleccha) point to khoṇḍ as a square (Santali) , the type of square on which two pillars are found in Dholavira. Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali). kũdar ‘brass-worker, turner’. Thus, koṇḍ habba is a celebration of the life-activity of the lapidaries/smiths of the civilization: kõdā meaning 'lathe-turning' for making perforated beads or for turning/forging metalware..This may explain why in the tablets showing procession as a festival ceremony, two hieroglyphs are carried as standards: both hieroglyphs relate to the one-horned young bull and the standard device (lathe). The related words reading hieroglyphs rebus from Meluhha (Mleccha) speech are: kõdā sã̄gāḍī Rebus words denote: ‘metals turner-joiner (forge); worker on a lathe’ – associates (guild)'.

This khoṇḍ 'square' could have been used to celebrate a festival which is called koṇḍahabba. The adorants walk on a bed of burning embers in fulfilment of their vows. Sucha bed of burning embers might have been laid on the square linking these two pillars of Dholavira shaped like sivalingas, symbolising pillars of fire. The significance attached to th word khoṇḍ may explain the local name for Dholavira: Kotḍa.

It is notable that a smithy was a temple for Meluhhans (Mlecchas). This is evidenced by the lexeme kole.l of Kota language which means 'smithy' and also 'temple'. Thus, a smithy is a temple -- kole.l Such a gestalt relatable to the lapidaries and smiths -- miners/metalworkers may explain why the agamas prescribe the procedures for invoking divinities in sculptures in a sanctum of a temple, adorned with metallic weapons on their multiple hands.

It is, thus, possible to hypothesise that the religious practices of the people of the civilization at Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kalibangan (where a terracotta Sivalinga has been found) and Dholavira are represented by the continuum of koṇḍahabba festivals celebrated by Lingavantas.

Turner

kundau, kundhi corner (Santali) kuṇḍa corner (S.): khoṇḍ square (Santali) *khuṇṭa2 ʻ corner ʼ. 2. *kuṇṭa -- 2 . [Cf. *khōñca -- ] 1. Phal. khun ʻ corner ʼ; H. khū̃ṭ m. ʻ corner, direction ʼ (→ P. khũṭ f. ʻ corner, side ʼ); G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻ angle ʼ. <-> X kōṇa -- : G. khuṇ f., khū˘ṇɔ m. ʻ corner ʼ. 2. S. kuṇḍa f. ʻ corner ʼ; P. kū̃ṭ f. ʻ corner, side ʼ (← H.).(CDIAL 3898).

Evidence for Sivalinga is provided in other sites (Mohenjodaro and Harappa) of the civilization:

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218. Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro.

Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro. Lingam, grey sandstone in situ, Harappa, Trench Ai, Mound F, Pl. X (c) (After Vats). "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I... in this jar, six lingams were found along with some tiny pieces of shell, a unicorn seal, an oblong grey sandstone block with polished surface, five stone pestles, a stone palette, and a block of chalcedony..." (Vats,MS, Excavations at Harappa, p. 370)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/sivalinga-in-dholavira-depicted-as.html

![Inline image 1]() The shape of the sivalinga in Harappa and the skambhas in Dholavira is like the Mount Kailas summit. In every Jyotirlinga temple (that is, a temple venerating Siva as a Fiery Pillar of Light), the sivalinga in the sanctum sanctorum is continuously bathed with dripping water from a vase kept atop the linga. This is a veneration of the Himalayas (Mt. Kailas) as the water-giving divinity with gllacial, perennial waters flowing from the greatest water tower of the world.

The shape of the sivalinga in Harappa and the skambhas in Dholavira is like the Mount Kailas summit. In every Jyotirlinga temple (that is, a temple venerating Siva as a Fiery Pillar of Light), the sivalinga in the sanctum sanctorum is continuously bathed with dripping water from a vase kept atop the linga. This is a veneration of the Himalayas (Mt. Kailas) as the water-giving divinity with gllacial, perennial waters flowing from the greatest water tower of the world.

![Inline image 2]()

![]() Naga worshippers of fiery pillar, Amaravati stup Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

Naga worshippers of fiery pillar, Amaravati stup Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

![Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha, , Great Stupa of Amaravati]()

http://bharatkalyan97.

Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha,

Iconography provides freedom to the artisan. The two lingas in Dholavira have NO base.

Naga worshippers of fiery pillar, Amaravati stup Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

Naga worshippers of fiery pillar, Amaravati stup Smithy is the temple of Bronze Age: stambha, thãbharā fiery pillar of light, Sivalinga. Rebus-metonymy layered Indus script cipher signifies: tamba, tã̄bṛā, tambira 'copper'

http://bharatkalyan97.

Railing crossbar with monks worshiping a fiery pillar, a symbol of the Buddha,

Atharva Veda Skambha Sukta predates archaeology of Sarasvati Sindhu civilization. The civilization dates from ca. 8th millennium BCE (pace BR Mani's article) https://friendsofasi.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

September 25, 2015