Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/nje59kn

Set Theory in Mathematics is used to demonstrate a Venn Diagram intersection for Indus Script cipher as an intersection between a hieroglyph set signifying pictures and a set of Meluhha words signifying metalwork. The intersections subset yields Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork. This is demonstrated using examples of processions of hieroglyph-multiplexes on Mohenjo-daro tablet, Jasper Akkadian cylinder, Dholavira Sign Board.

Hieroglyphs signifying 'lathe' or 'joined animals --sãghāṛɔ (Gujarati) sãgaḍ (Marathi) linked together' are signifiers of sangara a proclamation by the artisans/traders of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization through Indus Scrip Corpora.

Such sangara'proclamations' are demonstrated using three examples from Indus Script Corpora: 1. Procession tablets of Mohenjo-daro 2. Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal procession of standard bearers 3. Dholavira Sign Board.

These three examples are proclamations of metalwork competence of Meluhha artisans presented as SETS.

The processions of hieroglyph-multiplexes are announcements of SETS which is a foundational theory of mathematics. What was achieved in mathematics by ancient Indians was also achieved in the delineation of sets on Indus Script Corpora.

The SETS of Indus Script Corpora relate to ONLY one category: metalwork.

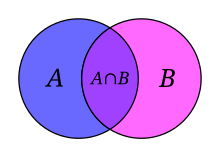

![]() Venn diagram, in mathematics, illustrating the intersection of two sets.

Venn diagram, in mathematics, illustrating the intersection of two sets.

Indian mathematics emerged in the Indian subcontinent from 1200 BCE until the end of the 18th century. In the classical period of Indian mathematics (400 CE to 1600 CE), important contributions were made by scholars like Aryabhata, Brahmagupta, Mahāvīra, Bhaskara II, Madhava of Sangamagrama and Nilakantha Somayaji....Since the 5th century BC, beginning with Greek mathematician Zeno of Elea in the West and early Indian mathematicians in the East, mathematicians had struggled with the concept of infinity. ...Set theory begins with a fundamental binary relation between an object o and a set A.If all the members of set A are also members of set B, then A is a subset of B, denoted A ⊆ B. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_mathematics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Set_theory)

Set Theory was propounded by Cantor. ( Cantor, Georg (1874), "Ueber eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen", J. Reine Angew. Math. 77: 258–262, doi:10.1515/crll.1874.77.258.) Wittgenstein critiques Set Theory as 'fictitious symbolism' and notes that it is nonsense to talk about all numbers. (Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1975). Philosophical Remarks, §129, §174. Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Cantor's proof was that there are more real numbers than integers and the 'infinity of infinities' which is explained as 'Cantor's paradise'. Cantor obtained a paradox by asking the question: 'What is the cardinal number of the set of all sets?' This was elaborated further in Russel's paradox by Bertrand Russel which noted: 'the set of all sets that are not members of themselves...leads to a paradox that it must be a member of itself, and not a member of itself.'

This paradox is resolved when a variable of language is used to describe the members of a set. This description is achieved on Indus Script Corpora. Artisans who designed the writing system chose hieroglyphs to signify 'tiger', 'elephant', 'zebu', 'crocodile' etcetera words which constituted a set of animals (both wild and domesticated). Meluhha had similar sounding words (i.e. words sounding similar to kola 'tiger'; karibha 'elephant', poLa 'zebu', karA 'crocodile'). These similar sounding words of Meluhha (Proto-Prakritam) constituted a set: metalwork set during the evolving Bronze Age: kol 'working in iron'; karba 'iron'; poLa 'magnetite'; khAr 'blacksmith'.

Thus a Venn Diagram evolves of the intersecting sets : set of animal hieroglyphs intersecting (A) with a set of metalwork semantics (B).

![]()

This intersection![]() creates the Indus Script Corpora.

creates the Indus Script Corpora.

Context-specific Set Theory of hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora

The symbolism apparent in Indus Script Corpora can be seen as 'meaningful' when the symbols are made context-specific. The context is a major life-activity of the Bronze Age when many ancestors were explorers of many minerals and experimenters of creating many alloys combining many minerals and also getting involved in cire perdue (lost wax) technology of metal castings. All these life-activities of a smith-forge defined their insights into cosmic and consciousness phenomena: of infinity, of relationships of geometric forms such as hypoteneuse of a right-angled triangle which signified a pythogorean relationship used to create fire-altars of various shapes but with defined areas.

By the time of the Yajurvedasaṃhitā- (1200–900 BCE), numbers as high as 1012 were being included in the texts. For example, the mantra (sacrificial formula) at the end of the annahoma ("food-oblation rite") performed during the aśvamedha, and uttered just before-, during-, and just after sunrise, invokes powers of ten from a hundred to a trillion: "Hail to śata ("hundred," 102), hail to sahasra ("thousand," 103), hail to ayuta ("ten thousand," 104), hail to niyuta("hundred thousand," 105), hail to prayuta ("million," 106), hail to arbuda ("ten million," 107), hail to nyarbuda ("hundred million," 108), hail to samudra ("billion," 109, literally "ocean"), hail to madhya ("ten billion," 1010, literally "middle"), hail to anta ("hundred billion," 1011,lit., "end"), hail to parārdha ("one trillion," 1012 lit., "beyond parts"), hail to the dawn (us'as), hail to the twilight (vyuṣṭi), hail to the one which is going to rise (udeṣyat), hail to the one which is rising (udyat), hail to the one which has just risen (udita), hail to svarga (the heaven), hail to martya (the world), hail to all."(Hayashi, Takao,2003, "Indian Mathematics", in Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, 1, pp. 118–130, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp.360-361) Hayashi 2005, p. 363 notes that the Śulba Sūtras contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians.""The diagonal rope (akṣṇayā-rajju) of an oblong (rectangle) produces both which the flank (pārśvamāni) and the horizontal (tiryaṇmānī) <ropes> produce separately."The Śulba Sūtras (literally, "Aphorisms of the Chords" in Vedic Samskritam) (c. 700–400 BCE) list rules for the construction of sacrificial fire altars. "The rope which is stretched across the diagonal of a square produces an area double the size of the original square."Sulbasutra contain examples of pythogorean triplets: (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (8, 15, 17), (7, 24, 25), and (12, 35, 37).

Part 1: Proclamation of procession tablets of Mohenjo-daro

A procession of iron, metalcasting workers is shown on the Mohenjo-daro tablets.

![]()

![]() Hieroglyph:er-aka 'upraised hand' (Tamil) erhali to hold out the hand;(Kui) erke, erkelů rising (Tulu)(DEDR 905) Rebus: eṟaka, eraka any metal infusion (Kannada); moltencast, cast (as metal) (Tulu)(DEDR 86) ; molten state, fusion.

Hieroglyph:er-aka 'upraised hand' (Tamil) erhali to hold out the hand;(Kui) erke, erkelů rising (Tulu)(DEDR 905) Rebus: eṟaka, eraka any metal infusion (Kannada); moltencast, cast (as metal) (Tulu)(DEDR 86) ; molten state, fusion. ![Image result for standard device indus script]() m0490At m0490Bt Tablet showing Meluhha combined standard of four standards carried in a procession, comparable to Tablet m0491.

m0490At m0490Bt Tablet showing Meluhha combined standard of four standards carried in a procession, comparable to Tablet m0491. ![]() m0491 This is a report on the transition from lapidary to bronze-age metalware in ancient Near East.

m0491 This is a report on the transition from lapidary to bronze-age metalware in ancient Near East.

eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: moltencast copper

dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: mineral ore dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻa partic. soft red stoneʼ (Marathi) (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)

kōnda 'young bull' Rebus: turner

sãgaḍ 'lathe' Rebus: sangara proclamation

kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: fireplace, furnace

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/11/tukulti-ninurta-worships-fire-god-at.html The first standard in the procession may be a spoked-wheel as in Tukulti-Ninurta hieroglyph:

![]() Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BC, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze AgeSource: http://www.dijitalimaj.com/alamyDetail.aspx?img=%7BA5C441A3-C178-489B-8989-887807B57344%7D The two standards (staffs) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) Glyph: eraka

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BC, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze AgeSource: http://www.dijitalimaj.com/alamyDetail.aspx?img=%7BA5C441A3-C178-489B-8989-887807B57344%7D The two standards (staffs) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) Glyph: eraka

Glyphic element: erako nave; era = knave of wheel. Glyphic element: āra ‘spokes’. Rebus: āra ‘brass’ as in ārakūṭa (Skt.) Rebus: Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt (DEDR 866) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) The same spoked-wheel hieroglyph adorns the Dholavira Sign-board.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/dholavira-gateway-to-meluhha-gateway-to.html?q=dholavira+sign

![]()

Such proclamations occur on combinations of hieroglyph-multiplexes and on processions of hieroglyph components.

Note the doted circles on the bottom register of the hieroglyph-multiplex of the standard device. These signify the semantics: 'full of holes'. The signifier is the word: Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ full of holes ʼ, G. kāṇũ ʻ full of holes ʼ, n. ʻ hole ʼ (< ʻ empty eyehole ʼ?(CDIAL 3019)kaṇa (pl. kaṇul) hole; (Go.)(DEDR 1159) Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) eye. Rebus: kanga ' large portable brazier, fire-place' (Kashmiri). Thus, the standard device is a combination of two hieroglyh components signifying: lathe, portable brazier: sangaDa + kanga Rebus: proclamation (collected products out of)+ fireplace.

![]() 'Eye' hieroglyph shown on Kuwait gold disk signifying kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: kanga 'fireplace, furnace'

'Eye' hieroglyph shown on Kuwait gold disk signifying kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: kanga 'fireplace, furnace'

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-hieroglyph-multiplex.html

kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

Hieroglyphs: G. sãghāṛɔ m. ʻ lathe ʼ; M. sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner's apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼ (LM 417 compares saggarai at Limurike in the Periplus, Tam.śaṅgaḍam, Tu. jaṅgala ʻ double -- canoe ʼ), sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ lathe ʼ; Si. san̆gaḷa ʻ pair ʼ, han̆guḷa, an̆g° ʻ double canoe, raft ʼ.(CDIAL 12859) Pa. saṅghāta -- m. ʻ killing, knocking together ʼ; Pk. saṁghāya -- m. ʻ closeness, collection ʼ; Or. saṅghā, saṅgā ʻ bamboo scaffolding inside triangular thatch, crossbeam of thatched house, copulation (of animals) ʼ; -- adj. ʻ bulled (of a cow) ʼ < *saṁghātā -- or saṁhatā -- ?(CDIAL 12862)

Rebus: Sangara [fr. saŋ+gṛ1 to sing, proclaim, cp. gāyati & gīta] 1. a promise, agreement J iv. 105, 111, 473; v. 25, 479

Rebus: saṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. [√ghaṭ ](CDIAL 12859) संगत saṅgata Assembled, collected, convened, met together.संगतिः saṅgatiḥ Company, society, association, intercourse (Samskritam. Apte) Sangata [pp. of sangacchati] 1. come together, met Sn 807, 1102 (=samāgata samohita sannipātita Nd2 621); nt. sangataŋ association Dh 207. -- 2. compact, tightly fastened or closed, well -- joined Vv 642 (=nibbivara VvA 275).Sangati (f.) [fr. sangacchati] 1. meeting, intercourse J iv. 98; v. 78, 483. In defn of yajati (=service?) at Dhtp 62 & Dhtm 79. -- 2. union, combination M i. 111; Sii. 72; iv. 32 sq., 68 sq.; Vbh 138 (=VbhA 188). <-> 3. accidental occurrence D i. 53; DA i. 161. (Pali)

"Even from its early stages the Sanskrit poetics has recognized the close association between the word and its sound, and between speech (vak) and meaning (artha). ..The elements that go into a kavya are the words, meanings and the way in which the words have to be compounded...Chitrakāvya ... treats pictures evoked by the sound of the word and its meaning as separate figures (sabda –chitra and artha-chitra); and it also in some other ways combines the word and the meaning into a common figure or an image (ubhaya-chitra)...Through a Kuta verse Vidura successfully cautions Yudhistira that the house built for them at Varnavata by Duryodhana is actually a lac -house; and it is meant to burn them all into ashes. Vidura says “Those who live in a hole like rats will not be harmed by fire. The blind man cannot find his way. So always be vigilant. Who takes a weapon not made of steel from their foes, can escape from fire by making their abode with many escape routes. He who can keep their five under control can never be oppressed by enemies".Its inner meaning was that the rogue Purochana would set the house on fire; he is a dreadful foe; you can guard yourself only when you runaway through the underground tunnel. Yudhistira replies “I understood what you said"; and saved himself, his brothers and their mother." http://creative.sulekha.com/chitrakavya-chitrabandha_541896_blog

The reference to Vidura's statement occurs in the context of Jatugriha Parva of Mahabharata when the emissary sent by Vidura, a miner named Khanaka explains the diabolical plan of Duryodhana to eliminate the Pandavas. The conversation between Khanaka and Yudhistira takes place in Meluhha dialect, notes the Great Epic. This dialect of Proto-Prakritam as related to metalwork constitutes the lexis revealed by decipherment of Indus Script Corpora -- listing minerals, metals, alloys, metal implements, metalworking resources such as smelters, furnaces, portable braziers.

Part 2: Proclamation of procession on Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-hieroglyph-readings-on.html

Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal ca. 2220-2159 BCE

Set Theory in Mathematics is used to demonstrate a Venn Diagram intersection for Indus Script cipher as an intersection between a hieroglyph set signifying pictures and a set of Meluhha words signifying metalwork. The intersections subset yields Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork. This is demonstrated using examples of processions of hieroglyph-multiplexes on Mohenjo-daro tablet, Jasper Akkadian cylinder, Dholavira Sign Board.

Hieroglyphs signifying 'lathe' or 'joined animals --sãghāṛɔ (Gujarati) sãgaḍ (Marathi) linked together' are signifiers of sangara a proclamation by the artisans/traders of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization through Indus Scrip Corpora.

Such sangara'proclamations' are demonstrated using three examples from Indus Script Corpora: 1. Procession tablets of Mohenjo-daro 2. Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal procession of standard bearers 3. Dholavira Sign Board.

These three examples are proclamations of metalwork competence of Meluhha artisans presented as SETS.

The processions of hieroglyph-multiplexes are announcements of SETS which is a foundational theory of mathematics. What was achieved in mathematics by ancient Indians was also achieved in the delineation of sets on Indus Script Corpora.

The SETS of Indus Script Corpora relate to ONLY one category: metalwork.

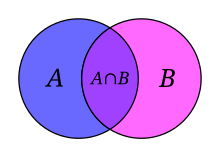

Venn diagram, in mathematics, illustrating the intersection of two sets.

Venn diagram, in mathematics, illustrating the intersection of two sets.Indian mathematics emerged in the Indian subcontinent from 1200 BCE until the end of the 18th century. In the classical period of Indian mathematics (400 CE to 1600 CE), important contributions were made by scholars like Aryabhata, Brahmagupta, Mahāvīra, Bhaskara II, Madhava of Sangamagrama and Nilakantha Somayaji....Since the 5th century BC, beginning with Greek mathematician Zeno of Elea in the West and early Indian mathematicians in the East, mathematicians had struggled with the concept of infinity. ...Set theory begins with a fundamental binary relation between an object o and a set A.If all the members of set A are also members of set B, then A is a subset of B, denoted A ⊆ B. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_mathematics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Set_theory)

Set Theory was propounded by Cantor. ( Cantor, Georg (1874), "Ueber eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen", J. Reine Angew. Math. 77: 258–262, doi:10.1515/crll.1874.77.258.) Wittgenstein critiques Set Theory as 'fictitious symbolism' and notes that it is nonsense to talk about all numbers. (Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1975). Philosophical Remarks, §129, §174. Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Cantor's proof was that there are more real numbers than integers and the 'infinity of infinities' which is explained as 'Cantor's paradise'. Cantor obtained a paradox by asking the question: 'What is the cardinal number of the set of all sets?' This was elaborated further in Russel's paradox by Bertrand Russel which noted: 'the set of all sets that are not members of themselves...leads to a paradox that it must be a member of itself, and not a member of itself.'

This paradox is resolved when a variable of language is used to describe the members of a set. This description is achieved on Indus Script Corpora. Artisans who designed the writing system chose hieroglyphs to signify 'tiger', 'elephant', 'zebu', 'crocodile' etcetera words which constituted a set of animals (both wild and domesticated). Meluhha had similar sounding words (i.e. words sounding similar to kola 'tiger'; karibha 'elephant', poLa 'zebu', karA 'crocodile'). These similar sounding words of Meluhha (Proto-Prakritam) constituted a set: metalwork set during the evolving Bronze Age: kol 'working in iron'; karba 'iron'; poLa 'magnetite'; khAr 'blacksmith'.

Thus a Venn Diagram evolves of the intersecting sets : set of animal hieroglyphs intersecting (A) with a set of metalwork semantics (B).

This intersection

creates the Indus Script Corpora.

creates the Indus Script Corpora.Context-specific Set Theory of hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora

The symbolism apparent in Indus Script Corpora can be seen as 'meaningful' when the symbols are made context-specific. The context is a major life-activity of the Bronze Age when many ancestors were explorers of many minerals and experimenters of creating many alloys combining many minerals and also getting involved in cire perdue (lost wax) technology of metal castings. All these life-activities of a smith-forge defined their insights into cosmic and consciousness phenomena: of infinity, of relationships of geometric forms such as hypoteneuse of a right-angled triangle which signified a pythogorean relationship used to create fire-altars of various shapes but with defined areas.

By the time of the Yajurvedasaṃhitā- (1200–900 BCE), numbers as high as 1012 were being included in the texts. For example, the mantra (sacrificial formula) at the end of the annahoma ("food-oblation rite") performed during the aśvamedha, and uttered just before-, during-, and just after sunrise, invokes powers of ten from a hundred to a trillion: "Hail to śata ("hundred," 102), hail to sahasra ("thousand," 103), hail to ayuta ("ten thousand," 104), hail to niyuta("hundred thousand," 105), hail to prayuta ("million," 106), hail to arbuda ("ten million," 107), hail to nyarbuda ("hundred million," 108), hail to samudra ("billion," 109, literally "ocean"), hail to madhya ("ten billion," 1010, literally "middle"), hail to anta ("hundred billion," 1011,lit., "end"), hail to parārdha ("one trillion," 1012 lit., "beyond parts"), hail to the dawn (us'as), hail to the twilight (vyuṣṭi), hail to the one which is going to rise (udeṣyat), hail to the one which is rising (udyat), hail to the one which has just risen (udita), hail to svarga (the heaven), hail to martya (the world), hail to all."(Hayashi, Takao,2003, "Indian Mathematics", in Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, 1, pp. 118–130, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp.360-361) Hayashi 2005, p. 363 notes that the Śulba Sūtras contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians.""The diagonal rope (akṣṇayā-rajju) of an oblong (rectangle) produces both which the flank (pārśvamāni) and the horizontal (tiryaṇmānī) <ropes> produce separately."The Śulba Sūtras (literally, "Aphorisms of the Chords" in Vedic Samskritam) (c. 700–400 BCE) list rules for the construction of sacrificial fire altars. "The rope which is stretched across the diagonal of a square produces an area double the size of the original square."Sulbasutra contain examples of pythogorean triplets: (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (8, 15, 17), (7, 24, 25), and (12, 35, 37).

Part 1: Proclamation of procession tablets of Mohenjo-daro

A procession of iron, metalcasting workers is shown on the Mohenjo-daro tablets.

Hieroglyph:er-aka 'upraised hand' (Tamil) erhali to hold out the hand;(Kui) erke, erkelů rising (Tulu)(DEDR 905) Rebus: eṟaka, eraka any metal infusion (Kannada); moltencast, cast (as metal) (Tulu)(DEDR 86) ; molten state, fusion.

Hieroglyph:er-aka 'upraised hand' (Tamil) erhali to hold out the hand;(Kui) erke, erkelů rising (Tulu)(DEDR 905) Rebus: eṟaka, eraka any metal infusion (Kannada); moltencast, cast (as metal) (Tulu)(DEDR 86) ; molten state, fusion.  m0491 This is a report on the transition from lapidary to bronze-age metalware in ancient Near East.

m0491 This is a report on the transition from lapidary to bronze-age metalware in ancient Near East. eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: moltencast copper

dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: mineral ore dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻa partic. soft red stoneʼ (Marathi) (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)

kōnda 'young bull' Rebus: turner

sãgaḍ 'lathe' Rebus: sangara proclamation

kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: fireplace, furnace

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/11/tukulti-ninurta-worships-fire-god-at.html The first standard in the procession may be a spoked-wheel as in Tukulti-Ninurta hieroglyph:

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BC, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze AgeSource: http://www.dijitalimaj.com/alamyDetail.aspx?img=%7BA5C441A3-C178-489B-8989-887807B57344%7D The two standards (staffs) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) Glyph: eraka

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BC, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze AgeSource: http://www.dijitalimaj.com/alamyDetail.aspx?img=%7BA5C441A3-C178-489B-8989-887807B57344%7D The two standards (staffs) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) Glyph: erakaGlyphic element: erako nave; era = knave of wheel. Glyphic element: āra ‘spokes’. Rebus: āra ‘brass’ as in ārakūṭa (Skt.) Rebus: Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt (DEDR 866) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) The same spoked-wheel hieroglyph adorns the Dholavira Sign-board.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/dholavira-gateway-to-meluhha-gateway-to.html?q=dholavira+sign

Such proclamations occur on combinations of hieroglyph-multiplexes and on processions of hieroglyph components.

Note the doted circles on the bottom register of the hieroglyph-multiplex of the standard device. These signify the semantics: 'full of holes'. The signifier is the word: Pk. kāṇa -- ʻ full of holes ʼ, G. kāṇũ ʻ full of holes ʼ, n. ʻ hole ʼ (< ʻ empty eyehole ʼ?(CDIAL 3019)kaṇa (pl. kaṇul) hole; (Go.)(DEDR 1159) Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) eye. Rebus: kanga ' large portable brazier, fire-place' (Kashmiri). Thus, the standard device is a combination of two hieroglyh components signifying: lathe, portable brazier: sangaDa + kanga Rebus: proclamation (collected products out of)+ fireplace.

'Eye' hieroglyph shown on Kuwait gold disk signifying kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: kanga 'fireplace, furnace'

'Eye' hieroglyph shown on Kuwait gold disk signifying kanga 'portable brazier' Rebus: kanga 'fireplace, furnace' See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-hieroglyph-multiplex.html

kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

Rebus: Sangara [fr. saŋ+gṛ

Rebus: saṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. [√

"Even from its early stages the Sanskrit poetics has recognized the close association between the word and its sound, and between speech (vak) and meaning (artha). ..The elements that go into a kavya are the words, meanings and the way in which the words have to be compounded...Chitrakāvya ... treats pictures evoked by the sound of the word and its meaning as separate figures (sabda –chitra and artha-chitra); and it also in some other ways combines the word and the meaning into a common figure or an image (ubhaya-chitra)...Through a Kuta verse Vidura successfully cautions Yudhistira that the house built for them at Varnavata by Duryodhana is actually a lac -house; and it is meant to burn them all into ashes. Vidura says “Those who live in a hole like rats will not be harmed by fire. The blind man cannot find his way. So always be vigilant. Who takes a weapon not made of steel from their foes, can escape from fire by making their abode with many escape routes. He who can keep their five under control can never be oppressed by enemies".Its inner meaning was that the rogue Purochana would set the house on fire; he is a dreadful foe; you can guard yourself only when you runaway through the underground tunnel. Yudhistira replies “I understood what you said"; and saved himself, his brothers and their mother." http://creative.sulekha.com/chitrakavya-chitrabandha_541896_blog

The reference to Vidura's statement occurs in the context of Jatugriha Parva of Mahabharata when the emissary sent by Vidura, a miner named Khanaka explains the diabolical plan of Duryodhana to eliminate the Pandavas. The conversation between Khanaka and Yudhistira takes place in Meluhha dialect, notes the Great Epic. This dialect of Proto-Prakritam as related to metalwork constitutes the lexis revealed by decipherment of Indus Script Corpora -- listing minerals, metals, alloys, metal implements, metalworking resources such as smelters, furnaces, portable braziers.

Part 2: Proclamation of procession on Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/indus-script-hieroglyph-readings-on.html

Jasper Akkadian cylinder seal ca. 2220-2159 BCE

![]()

Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) cylinder Seal with four hieroglyphs and four kneeling persons (with six curls on their hair) holding flagposts, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Cylinder Seal (with modern impression). The four hieroglyphs are: from l. to r. 1. crucible PLUS storage pot of ingots, 2. sun, 3. narrow-necked pot with overflowing water, 4. fish A hooded snake is on the edge of the composition. (The dark red color of jasper reinforces the semantics: eruvai 'dark red, copper' Hieroglyph: eruvai 'reed'; see four reedposts held. koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse'

If the hieroglyph on the leftmost is moon, a possible rebus reading: قمر ḳamarA قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) Rebus: kamar 'blacksmith'

Part 3: Proclamation on Dholavira Sign Board

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/dholavira-1-signboard-and-2-stone.htmlDholavira. gateway. A designer's impressions (reconstruction) of the world's first signboard on the gateway of fortification or citadel.![]() This is the huge hoarding on the northern gateway of Dholavira fortification. I call this the Bronze Age Meluhha Standard. The Standard exemplified the gateway to Bronze Age Sarasvati civilization. The Sheffield of the Ancient Near East, Chanhu-daro (River Sarasvati right-bank), is about 150 kms. to the north if a seafaring-riverine merchant from Sumer, Mesopotamia, Dilmun, or Magan moved on the navigable River Sarasvati beyond the port town of Dholavira.

This is the huge hoarding on the northern gateway of Dholavira fortification. I call this the Bronze Age Meluhha Standard. The Standard exemplified the gateway to Bronze Age Sarasvati civilization. The Sheffield of the Ancient Near East, Chanhu-daro (River Sarasvati right-bank), is about 150 kms. to the north if a seafaring-riverine merchant from Sumer, Mesopotamia, Dilmun, or Magan moved on the navigable River Sarasvati beyond the port town of Dholavira.

The signboard deciphered in three segments from r.

ḍato ‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

![]() Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍaren lid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼ Rebus:kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara— m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaḍha 'ficus religiosa' (Skt.); kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).Dholavira Signboard inscription of gypsum inlays on wood measures 3 m. long. Each of the 10 signs is 37 cm. high and 25 to 27 cm. wide and made of pieces of white gypsum inlays; the signs were apparently inlaid in a wooden plank. The conjecture is that this wooden plank was mounted on the Northern Gateway as a Signboard.

Dholavira Signboard

The Signboard which adorned the Northern Gateway of the citadel of Dholavira was an announcement of the metalwork repertoire of dhokra kamar, cire perdue metalcasters and other smiths working with metal alloys. The entire Indus Script Corpora are veritable metalwork catalogs. The phrase dhokra kamar is rendered on a tablet discovered at Dholavira presented in this monograph (earlier discussed at

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-1-dhokra-lost-wax.html ). The 10-hieroglyph inscription of Dholavira Signboard has been read rebus and presented at

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/dholavira-gateway-to-meluhha-gateway-to.html

Excerpts from Excavation Report on Dholavira released by ASI in 2015:

"8.1 Inscriptions. Literacy of the Harappans is best exemplified in their inscriptions written in a script that is unparalleled in its characters hitherto unknown and undeciphered so far. These inscriptions are best represented on their seals and seals-impressions in addition to those engraved or painted on the objects of metal, terracotta, pottery, faience, ivory, bone and stone, albeit sometimes appearing in a single sign inscription or scratching particularly on pottery or terracotta objects. 8.1.1 Signboard. One of the most prominent discoveries from the excavations at Dholavira is the find of a 10 large sized signboard presently lying in the western chamber of North Gate. This inscription was found lying in the western chamber of north gate, and the nature of find indicates that it could have been fitted on a wooden signboard, most probably fitted above the lintel of the central passageway of the gate. The central passageway of north gate itself measures 3.5 m in width and the length of the inscription along with the wooden frame impression is also more or less same thereby indicating the probable location. The inscription consists of 10 large-sized letters of the typical Harappan script, and is actually gypsum inlays cut into various sizes and shapes, which were utilized to create each size as, indicated above. The exact meaning of the inscription is not known in the absence of decipherment of script." (pp.227-229, Section 8.1.1 Signboard)

"The central passageway of north gate itself measures 3.5 m in width and the length of the inscription along with the wooden frame impression is also more or less same thereby indicating the probable location. The inscription consists of 10 large-sized letters of the typical Harappan script, and is actually gypsum inlays cut into various sizes and shapes, which were utilized to create each size as, indicated above. The exact meaning of the inscription is not known in the absence of decipherment of the script. (p.231)

Fig. 8.2: Location of ten large sized inscription in North Gate

Fig. 8.3: Close-up of inscription

Fig. 8.4: Drawing showing the ten letters of inscription

Fig. 8.5: Photograph showing the details of inscription in situ.

Fig. 8.6: Close-up of some of the letters from the inscription

Fig. 8.7: Gypsum inlays used for the inscription

Such proclamations may be noted on other examples from Indus Script Corpora:

![]() Tell Asmar Cylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri); karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' (Tulu); kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'.

Tell Asmar Cylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri); karibha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' (Tulu); kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'.![]() Dwaraka 1 seal of turbinella pyrum: Ligaturing to the body of an ox: a head of one-horned young bull, and a head of antelope. Thus, there are three hieroglyphs signifying: ox, young bull and antelope.sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together (Marathi) Rebus: sangara 'proclamation'; barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'.

Dwaraka 1 seal of turbinella pyrum: Ligaturing to the body of an ox: a head of one-horned young bull, and a head of antelope. Thus, there are three hieroglyphs signifying: ox, young bull and antelope.sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together (Marathi) Rebus: sangara 'proclamation'; barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'.

The Venn Diagram intersection of Indus Script cipher ![]() creates the Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum, metalwork catalogues.

creates the Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum, metalwork catalogues.

Since the epigraphs or inscriptions of Indus Script are sangara'proclamations' they become catalogues conveying to the receivers of the messages information on technical specifications of innovative metalwork accomplishments.These accomplishments were a life-activity of Bhāratam Janam, metalcaster people (RV 3.53.12: Visvamitra)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

September 1, 2015

khuṇṭa 'peg’; khũṭi = pin (M.) rebus: kuṭi= furnace (Santali) kūṭa ‘workshop’ kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.)