Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/odbh7y8

One of the challenges in the narration of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam is the firm delineation of identity of ancestors of Bhāratam Janam, their locus, speech forms and life-activities. One semantic cluster identifying one life-activity relates to metalwork (vessels, implements, weapons), metalcastings (using cire perdue, lost-wax techniques) as ancient people of Sarasvati-Sindhu valleys transited into the metals age.

That the language spoken by these Bhāratam Janam, metalcaster folk, was Meluhha is inferred from Shu-ilishu cylinder seal with Akkadian cuneiform text.

பாரதம்¹ pāratam , n. < Bhārata. 1. India; இந்தியா தேசம். இமயகிரிக்குந் தென்கடற்கு மிடைப் பாகம் பாரதமே (சிவதரு. கோபுர. 51). 2. The great war of Kurukṣētra; பாரதப்போர். நீயன்றி மாபாரதமகற்ற மற்றார்கொல் வல்லாரே (பாரத. கிருட் டிண. 34). 3. The Mahābhārata; மகாபாரதம். 4. A very long account; மிகவிரிவான செய்தி. பன்னி யுரைக்குங்காற் பாரதமாம் (திவ். இயற். பெரிய. ம. 72).பாரதவருடம் pārata-varuṭam, n. < id. +. A division of the earth, the country of India, one of nava-varuṭam, q.v.; நவவருடத் தொன் றாகிய இந்தியா. தென்கடற்கு மிமயமென்னுங் கிரிக்கு நடுப் பாரதமாம் (கந்தபு. அண்டகோ. 37).பாரதி¹ pārati, n. < bhāratī. 1. Sarasvatī; சரசுவதி. (பிங்.) (சிவப். பிர. வெங்கையு. 121.) 2. Goddess Bhairavī; பைரவி. பாரதி யாடிய பாரதி யரங்கத்து (சிலப். 6, 39). 3. Learned person; பண்டிதன். 4. Word; சொல். (யாழ். அக.) பாரதி² pārati , n. cf. பரதர்¹. Sailing vessel; மரக்கலம். (திவா.) பவப்புணரி நீந்தியாடப் பாரதிநூல் செய்த சிவப்பிரகாசக் குரவன் (சிவப். பிர. சோண. சிறப். பாயி.).

பரதவர் paratavar

, n. < bharata. 1. Inhabitants of maritime tract, fishing tribes; நெய்தனிலமாக்கள். மீன்விலைப் பரதவர் (சிலப். 5, 25). 2. A dynasty of rulers of the Tamil country; தென் றிசைக்கணாண்ட ஒருசார் குறுநிலமன்னர். தென்பரத வர் போரேறே (மதுரைக். 144). 3. Vaišyas; வைசி யர். பரதவர் கோத்திரத் தமைந்தான் (உபதேசகா. சிவத்துரோ. 189)

![]()

![map]()

![Image result for potsherd HARP]() Potsherd h1522 discovered in Harappa on the banks of River Ravi by archaeologists of HARP (Harvard Archaeology Project) is dated to ca. 3300 BCE. The word for the hieroglyph is: kolmo ‘rice plant, sprout’ (Santali) Rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ (Telugu) These glosses from Santali and Telugu are examples of the reconstructed lexis of Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha/Mleccha vernacular of Vedic people almost all of whom lived on the banks of Vedic Sarasvati river system or in the Saptasindhu region (sindhu‘river’).

Potsherd h1522 discovered in Harappa on the banks of River Ravi by archaeologists of HARP (Harvard Archaeology Project) is dated to ca. 3300 BCE. The word for the hieroglyph is: kolmo ‘rice plant, sprout’ (Santali) Rebus: kolimi ‘smithy, forge’ (Telugu) These glosses from Santali and Telugu are examples of the reconstructed lexis of Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha/Mleccha vernacular of Vedic people almost all of whom lived on the banks of Vedic Sarasvati river system or in the Saptasindhu region (sindhu‘river’).

![]()

In terms of chronology, it will be reasonable to date the textual evidence provided by chandas of Rigveda about two millennia prior to the earliest archaeological finds (ca. 3500 BCE) of Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization and archaeological finds in contact areas of Sumer-Mesopotamia from early Bronze Age.

A hypothesis is that the ethical duo of Dharma-Dhamma is the narrative of the Itihaasa of BharatamJanam over five millennia. The narrative has yet to be told as more researches and more archaeological explorations will continue to provide evidence to test this hypothesis.

Indus Script decipherment is, in effect, an imperative for scholars engaged in civilization studies, an essential contribution to the Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam, an expression used by Rishi Visvamitra in Rigveda (RV 3.53.12: viśvā́mitrasya rakṣati

![]()

This follows the insightful, scintillating presentation by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale which presents an exposition of art appreciation of Indus Script Corpora with particular reference to orthographic fidelity to signify hypertext components on inscriptions. A paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html In this post, it has been argued that the hypertexts of pictorial motifs on Indus Script Corpora discussed by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale should be extended to hieroglyphs as 'signs' and ligatured hieroglyphs as 'signs' on 'texts' of the Indus inscriptions. The entire Indus Script Corpora consist of hieroglyph multiplexes -- using hieroglyphs as components -- and hence, the comparison with hypertexts need not be restricted to pictorial motifs or field symbols of Indus inscriptions. See also: Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).Mirror: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/document-preview.aspx?doc_id=9163376 The use of the phrase 'hypertexts' in the context of Indus Script is apposite because, the entire Indus Script Corpora is founded on rebus-metonymy-layered representations of Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund, speech area of ancient Bhāratam Janam of the Bronze Age.

![]()

Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components. Harappan chimera and its hypertextual components. The 'expression' summarizes the syntax of Harappan chimeras within round brackets, creatures with body parts used in their correct anatomic position (tiger, unicorn, markhor goat, elephant, zebu, and human); within square brackets, creatures with body parts used to symbolize other anatomic elements (cobra snake for tail and human arm for elephant proboscis); the elephant icon as exonent out of the square brackets symbolizes the overall elephantine contour of the chimeras; out of brackes, scorpion indicates the animal automatically perceived joining the lineate horns, the human face, and the arm-like trunk of Harappan chimeras. (After Fig. 6 in: Harappan chimaeras as 'symbolic hypertexts'. Some thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization (Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale, 2012)

![Image result for 16747 ur seal impression]()

Identifying Meluhha gloss for parenthesis hieroglyph or ( ) split ellipse: குடிலம்¹ kuṭilam, n. < kuṭila. 1. Bend curve, flexure; வளைவு. (திவா.) (Tamil) In this reading, the Sign 12 signifies a specific smelter for tin metal: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/ kuṭila, 'tin (bronze)metal; kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Samskritam) See: http://download.docslide.us/uploads/check_up03/192015/5468918eb4af9f285a8b4c67.pdf

It will be seen from Sign 15 that the basic framework of a water-carrier hieroglyph (Sign 12) is superscripted with another hieroglyph component, Sign 342: 'Rim of jar' to result in Sign 15. Thus, Sign 15 is composed of two hieroglyph components: Sign 12 'water-carrier' hieroglyph; Sign 342: "rim-of-jar' hieroglyph (which constitutes the inscription on Daimabad Seal 1).

kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe'

![]() Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Each hieroglyph component of Sign 15 is read in rebus-metonymy-layered-meluhha-cipher: Hieroglyph component 1: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'. Hieroglyph component 2: kanka, kārṇī-ka 'rim-of-jar' rebus: kanka, kārṇī-ka m. ʻsupercargo of a shipʼ 'scribe'.

![]()

![]()

Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex on m1405 is read rebus from r.: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka eraka bharata pattar'goldsmith-merchant guild -- smelting furnace account (scribe), molten cast metal infusion, alloy of copper, pewter, tin.'

![]() aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'![]() aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot'

aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot'![]() aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'![]() aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements'

aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements'![]() aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge'

aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge'![]() aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace'

aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace'![]() aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'

aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'![]() aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'![]() aya tridhAtu 'fish+three strands of rope' Rebus: aya kolom dhatu 'metal/iron , three mineral ores'

aya tridhAtu 'fish+three strands of rope' Rebus: aya kolom dhatu 'metal/iron , three mineral ores'![]() Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ See: अयस्कांत [ ayaskānta ] m S (The iron gem.) The loadstone. (Molesworth. Marathi) Fish + circumgraph of 4 (gaNDa) notches: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) The gloss kāṇḍa may also signify 'metal implements'. A cognate compound in Santali has: me~r.he~t khaNDa 'iron implements'.

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ See: अयस्कांत [ ayaskānta ] m S (The iron gem.) The loadstone. (Molesworth. Marathi) Fish + circumgraph of 4 (gaNDa) notches: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) The gloss kāṇḍa may also signify 'metal implements'. A cognate compound in Santali has: me~r.he~t khaNDa 'iron implements'.

Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032, glyphs used are: Zebu (bos taurus indicus), fish, four-strokes (allograph: arrow).ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) + kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) gaṆḌa, ‘four’ (Santali); Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’, ‘furnace’), arrow read rebus in mleccha (Meluhhan) as a reference to a guild of artisans working with ayaskāṇḍa ‘excellent quantity of iron’ (Pāṇini) is consistent with the primacy of economic activities which resulted in the invention of a writing system, now referred to as Indus Writing. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'.![]() Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl (Marathi); kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe 'young bullock' (Konda) rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) [The characteristic pannier which is ligatured to the young bull pictorial hieroglyph is a synonym खोंडा 'cowl' or 'pannier').खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) ] खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf.(Marathi) खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl.खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/excavations-at-dholavifra-1989-2005-rs.html

The intimations of a metals turner as a scribe are also gleaned from the gloss: खोडाखोड or डी [ khōḍākhōḍa or ḍī ] f (खोडणें ) Erasing, altering, interlining &c. in numerous places: also the scratched, scrawled, and disfigured state of the paper so operated upon; खोडींव [ khōḍīṃva ] p of खोडणें v c Erased or crossed out.Marathi). खोडपत्र [ khōḍapatra ] n Commonly खोटपत्र .खोटपत्र [ khōṭapatra ] n In law or in caste-adjudication. A written acknowledgment taken from an offender of his falseness or guilt: also, in disputations, from the person confuted. (Marathi) Thus, khond 'turner' is also an engraver, scribe.

That a metals turner is engaged in metal alloying is evident from the gloss: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit (as of phlegm, gore, curds, inspissated milk); any concretion or clot.खोटीचा Composed or made of खोट , as खोटीचें भांडें .![]() After Korvink Korvink, Michael. 2008. The Indus Script: A Positional Statistical Approach. Gilund Press.

After Korvink Korvink, Michael. 2008. The Indus Script: A Positional Statistical Approach. Gilund Press.![]() aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

Text: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'

Pictorial motifs or hieroglyph-multiplexes: sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace' Rebus: sangar 'fortification' sanghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira) samghAta 'collection of articles (i.e. cargo)' PLUS khōṇḍa m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe 'young bullock' (Konda)Rebus: kõdā 'to turn in a lathe' (Bengali)

![]() Seal.

Seal.![]() aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'![]() aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'![]() mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) PLUS (infixed) kolom 'sprout, rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' Thus, ingot smithy

mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) PLUS (infixed) kolom 'sprout, rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' Thus, ingot smithy ![]() kolom 'rice-plant, sprout' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Alternative: kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter')

kolom 'rice-plant, sprout' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Alternative: kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter')

kaṇḍa kanka ‘rim of jar’ Rebus: karṇīka ‘account (scribe)’karṇī‘supercargo’.

kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’.

लोह --कार [p= 908,3]

kamaṭh a crab (Skt.) kamāṭhiyo=archer;kāmaṭhum =a bow; kāmaḍī ,kāmaḍum=a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo bowman; an archer(Skt.lex.) kamaṛkom= fig leaf (Santali.lex.)kamarmaṛā(Has.), kamaṛkom(Nag.); the petiole or stalk of a leaf (Mundari.lex.)kamaṭha= fig leaf, religiosa(Skt.) dula‘tw' Rebus: dul 'cast metal ’Thus, cast loh ‘copper casting’ infurnace:baṭa= wide-mouthed pot; baṭa= kiln (Te.) kammaṭa=portable furnace(Te.) kampaṭṭam 'coiner,mint' (Tamil) kammaṭa (Malayalam) The hieroglyph-multiplex (Sign 124 Parpola conconcordance), thus orthographically signifies two ficus leaves ligatured to the top edge of a wide rimless pot and a pincers/tongs hieroglyph is inscripted. In this hieroglyph-multiplex three hieroglyph components are signified: 1. rimless pot, 2. two ficus leaves, 3. pincers. baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'; loa 'ficus' Rebus: loha 'copper, iron'; kAru 'pincers' Rebus: khAra 'blacksmith'

![]() Mohenjodaro. Tablet.

Mohenjodaro. Tablet.

![]()

![]() aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' PLUS meḍha '

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' PLUS meḍha '

![]() Santali glosses. Lexis.

Santali glosses. Lexis.

One of the challenges in the narration of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam is the firm delineation of identity of ancestors of Bhāratam Janam, their locus, speech forms and life-activities. One semantic cluster identifying one life-activity relates to metalwork (vessels, implements, weapons), metalcastings (using cire perdue, lost-wax techniques) as ancient people of Sarasvati-Sindhu valleys transited into the metals age.

That the language spoken by these Bhāratam Janam, metalcaster folk, was Meluhha is inferred from Shu-ilishu cylinder seal with Akkadian cuneiform text.

This monograph traces the roots of Bhāratam Janam on the banks of Rivers Sarasvati-Sindhu Himalayan river systems speaking a form of Proto-Prākritam which has left traces of glosses in the lexis of many languages of Indian sprachbund(speech union). Sarasvati’s children developed a unique writing system based on Proto-Prakritam called Meluhha in cuneiform texts and Mleccha in ancient Indian texts. The writing system was called mlecchita vikalpa (i.e. alternative representation of mleccha) in Vatsyayana’s treatise on Vidyāsamuddesa (ca 6th century BCE). The principal life-activity of artisan guilds of Bhāratam Janam was metalwork creating metalcastings, experimenting with creation of various forms of alloys and making metal implements which was a veritable revolution transiting from chalcolithic phase to metals age in urban settings. This archaeometallurgical legacy finds expression in the famed, non-rusting Delhi iron pillar which was originally from Vidisha (Besanagara, Sanchi).

பரதவர் paratavar

, n. < bharata. 1. Inhabitants of maritime tract, fishing tribes; நெய்தனிலமாக்கள். மீன்விலைப் பரதவர் (சிலப். 5, 25). 2. A dynasty of rulers of the Tamil country; தென் றிசைக்கணாண்ட ஒருசார் குறுநிலமன்னர். தென்பரத வர் போரேறே (மதுரைக். 144). 3. Vaišyas; வைசி யர். பரதவர் கோத்திரத் தமைந்தான் (உபதேசகா. சிவத்துரோ. 189)

The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. A Mesopotamian cylinder seal referring to the personal translator of the ancient Indus or Meluhan language, Shu-ilishu, who lived around 2020 BCE during the late Akkadian period. The late Dr. Gregory L. Possehl, a leading Indus scholar, tells the story of getting a fresh rollout of the seal during its visit to the Ancient Cities Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2004.

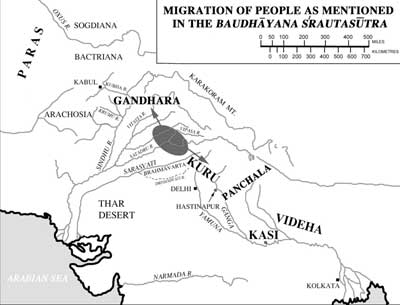

Decipherment of Indus Script Corpora based on an Indo-European language may lead to redefining the Proto-Indo-European studies. Baudhāyana-Śrautasūtra provides indications of movements of Bhāratam Janam out of Sarasvati river valley eastwards towards Kashi and westwards towards Sumer/Mesopotamia.

BB Lal provides evidences of migrations of Proto-Indo-Aryans out of India in this map citing Baudhayana Srautasutra evidence. Parpola has ignored this evidence from a primary source. Thus, all the arguments he provides about BMAC and other Eurasian cultures with exquisite pictures of horses and wheeled vehicles are empty and based on a faith in what Emeneau referred to as 'the linguistic doctrine' of Aryan invasion/migration to explain the peopling and languages of India. The directions of movements of Proto-Indo-Aryans could have been OUT OF India and NEED NOT be construed as movements INTO India.

See: Inaugural Address delivered by BB Lal at the 19th International Conference on South Asian Archaeology at University of Bologna, Ravenna, Italy on July 2–6, 2007 'Let not the 19th century paradigms continue to haunt us!' http://archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/19th-century-paradigms.html

Baudhāyana-Śrautasūtra 18.44 :397.9 sqq. notes:

pran ayuh pravavraja. tasyaite kuru-pancalah kasi-videha ity. etad Ayavam pravrajam. pratyan amavasus. tasyaite gandharvarayas parsavo‘ratta ity. etad Amavasavam. “Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru-Pancala and the Kasi Videha. This is the Ayava migration. (His other people) stayed at home in the West. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group)...”

That the original location of these peole (who split into two groups and migrated) was in Sarasvati river valley is proved by the next sutra which identifies Kurukshetra. Ayu went eastwards, Amavasu went westwards towards Parsava. So begins the journey of Indo-Europeans into Proto-Indo-Aryan, Proto-Indo-Iranian language forms. This framework demolishes the Aryan invasion/migration theories based on textual evidence which is attested by archaeological evidence. Just as it is impossible to delineate directions of borrowings of words in languages, it is also impossible to delineate directions of movements of people. It appears that the presence of Indus Script hieroglyphs in Ancient Near East and the gloss ancu in Tocharian attest the movement of Proto-Prakritam speaking Bhāratam Janam into Bactria-Margiana Cultural Complex and into Tushara (Tocharian speaking region of Kyrgystan on the Silk Road).

The imperative of decipherment of Indus Script Corpora or mlecchita vikalpais not merely to fill out a cross-word puzzle but to understand the roots of Indian civilization, the language the people spoke (ca. 3300 BCE when the potsherd with writing was created) and the messages documented with extraordinary fidelity in the Corpora.

Roots of Bhāratam Janam have to be the mission, focus of attention of archaeological researches. The roots have to be found by delineating the cultural mores of the people as they evolved over time and tracing the formation and evolution of ancient Indian languages. Indus Script Corpora are an essential primary resource for this mission.

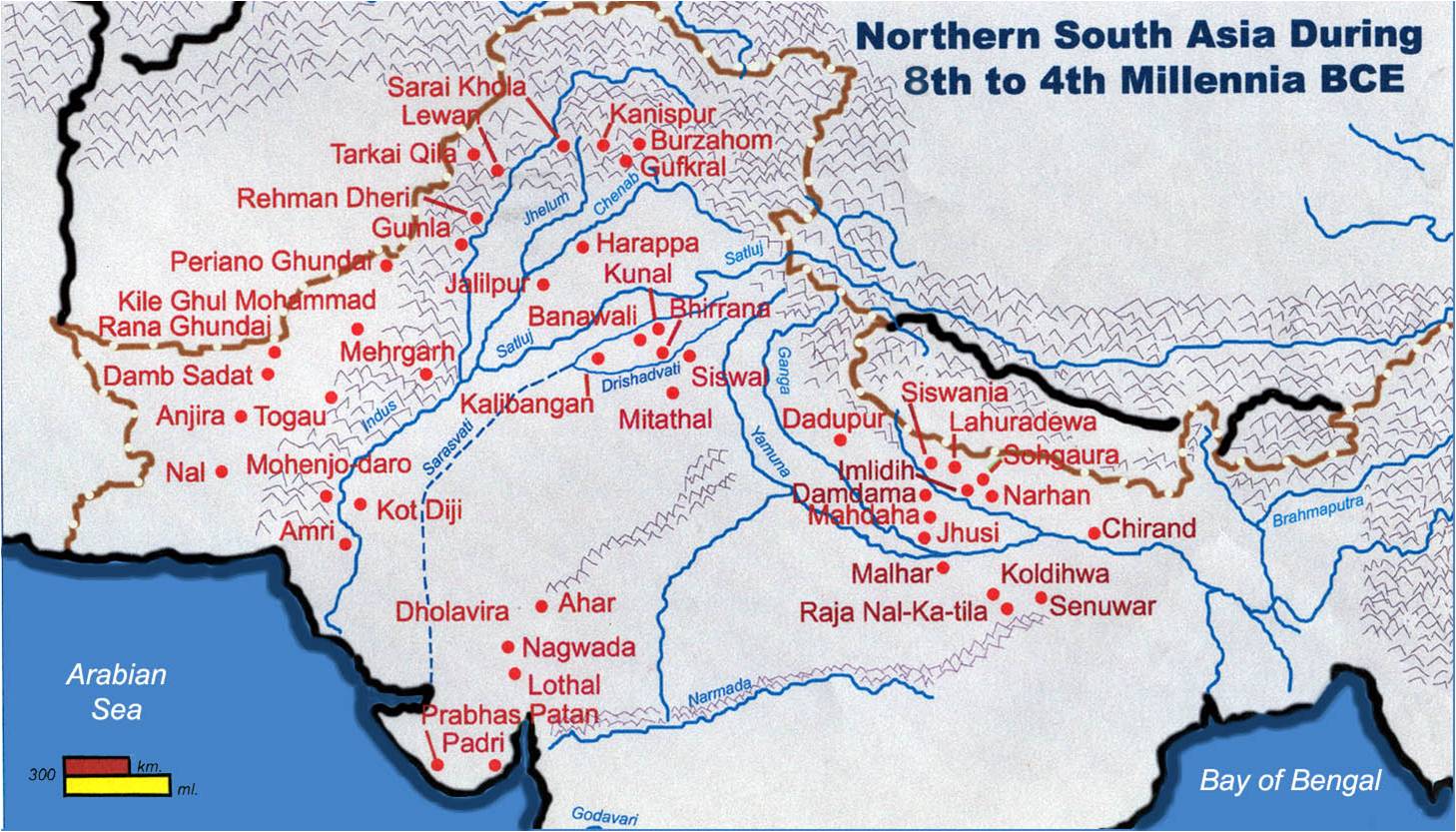

Dr. BR Mani and Dr. KN Dikshit have provided (2013) this illustration of the map of Indian civilization with archaeological evidences tracing back to the 8th millennium BCE. This provides a spatial framework for analysing the formation of all ancient Indian languages.

Roots of Bhāratam Janam have to be traced from the banks of Rivers Sarasvati and Sindhu identifying their life-activity as metalworkers, metalcasters who made भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal भरत. 2 See भरिताचें भांडें.भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत. (Marathi. Moleworth).

It should be underscored that भारतम् जनम् Bhāratam janam is the self-designation in Rigveda RV 3.53.12 indicating the life activities of the people as they were transiting from chalcolithic phase to metals age in urban living.

Roots of Bhāratam Janam and Hindu civilization have to be understood from Gautama Buddha's Dhammapada Verse 5 Kalayakkhini Vatthu on the gestalt of the people, Indus civilization thought about dharma, derived from the Vedic pramANa:

न हि वेरेण वेराणि

सम्मन्तिद कदाचनं

अवेरेण च संमन्ति

एष धम्मो सनन्तणो

Na hi verena verani

sammantidha kudacanam

averena ca sammanti

esa dhammo sanantano.

Verse 5: Hatred is, indeed, never appeased by hatred in this world. It is appeased only by loving-kindness. This is an ancient law सनातनधर्म Sanātana dharma, dharma eternal.

sammantidha kudacanam

averena ca sammanti

esa dhammo sanantano.

Verse 5: Hatred is, indeed, never appeased by hatred in this world. It is appeased only by loving-kindness. This is an ancient law सनातनधर्म Sanātana dharma, dharma eternal.

Intimations of religious practices of Bharatam Janam

There are markers from which hypotheses can be formulated as regards the religious practices of the people of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The most emphatic artefacts are the architectural features unearthed in Dholavira showing a pair of polished pillars and an 8-shaped stone structure with stone-altars. These finds have to be seen in the context of five s'iva-linga stones found in Harappa and a terracotta s'iva-linga found in Kalibangan. These evidences have to be re-evaluated in the context of the continuing religious and cultural practices in adoration of Agni as the flaming pillar, S'iva and forms of cosmic dancer all over Bharatam or ಕೊಂಡಹಬ್ಬ fire-walking celebrations of lingayata-s ಲಿಂಗಾಯತ.

We do not know if the the pair of polished stone pillars were part of such celebrations or the representation of cosmic metaphors of Skambha Sukta स्कम्भसूक्तम् (Atharva veda Book 10 Hymn 7).

Profound evidences of religious/cultural continuum continuum is provided by the following:

1. the practice of wearing sindhur by married women. Two terracotta toys found in Nausharo (Mehergarh) showed two women wearing red vermilion (sindhur) at the parting of the black hair, a practice which continues even today in Bharatam.

2. the veneration of s'ankha (turbinella pyrum) as a pancajanya of Sri Krishna to call Bharatam Janam to arms. A burial of a woman in Nausharo showed her wearing s'ankha bangles and jewellery; the burial was dated to ca. 6500 BCE. Turbinella Pyrum shells used as trumpets were are discovered as archaeological artifacts.

It will be an error to reconstruct the ancient cultural mores of Bharatam Janam based on pre-judged categories such as Aryan or Dravidian or Munda (Austro-Asiatic) given the overwhelming evidence of an Indian sprachbund, a language union which united the three main language streams and the overwhelming legacy of Prakrit words, many with Samskritam/Chandas (Vedic) cognates, in all present-day languages of Bharatam. For example, 90% of the glosses in Tamil Lexicon (Madras University) contain Samskritam tatsama (cognate) or tadbhava (etyma). Over 11% Sanskrit glosses trace their links to Munda. (pace FBJ Kuipter). There is now sufficient evidence to prove the reality of the Indian sprachbundin an Indian Lexicon with over 8000 semantic clusters including Aryan-Dravidian-Munda glosses, thus questioning the rationale for separating the trio into separate etymological dictionaries.

Vedic River Sarasvati is also mentioned in the two Great Epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata. Mahabharata provides details of pariyatra of Sri Balarama along the River Sarasvati from Dwaraka to the origin in Plaksha Prasravana in Himalayan glaciers. The channels of this river also account for 80% of archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization on the banks of the two rivers: Sindhu and Sarasvati.

Hopefully, excavations of all the 2,500+ sites of the civilization will help unravel the cultural/religious practices of Bharatam Janam (Mleccha, Hindu) as the practices evolved over time from ca 5th millennium BCE of the Bronze Age. Further researches will unravel the links with the Kirata (Mleccha) janapada and Asura on Ganga basin and the evolution of technologies related to metalwork exemplified by the iron smelters found in Malhar, Raja-nal-ki-tila, Lohardiwa; the non-rusting iron pillar of Vidisha (Sanchi) now in Delhi; the cire perdue alloy metalcastings by dhokra kamar of Bastar or vis'vakarma artisans of Swamimalai in Tamil Nadu evoking the tradition which dates back to ca. 2500 BCE when the dancing girl bronze statue was cast or earlier to ca. 5th millennium BEC when the Nahal Mishmar cire perdue bronze castings were carried aloft in processions by artisans of the Bronze Age across Eurasia along the Tin Road from Meluhha to Mishmar.

It will also be an error to separate Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization and Vedic cuture, premised on erroneous pre-judged chronological sequencing. Sarasvati-Sindhu and Vedic cultures are two sides of the same cultural coin: one dominated by mleccha/meluhha people transacting in the lingua franca, working as Fire workers, excelling in metalcasting work and the other by Philosophers of Fire or Knowledge Explorers, engaged in tapasya and yoga on the links between Being and Becoming. The narrative, the Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam will provide a united narrative of the two converging streams of civilizational and technological advances, both related to enquiries into knowledge systems which found eternal expression in the twin founding ethical principles of Dharma-Dhamma.

There are markers from which hypotheses can be formulated as regards the religious practices of the people of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The most emphatic artefacts are the architectural features unearthed in Dholavira showing a pair of polished pillars and an 8-shaped stone structure with stone-altars. These finds have to be seen in the context of five s'iva-linga stones found in Harappa and a terracotta s'iva-linga found in Kalibangan. These evidences have to be re-evaluated in the context of the continuing religious and cultural practices in adoration of Agni as the flaming pillar, S'iva and forms of cosmic dancer all over Bharatam or ಕೊಂಡಹಬ್ಬ fire-walking celebrations of lingayata-s ಲಿಂಗಾಯತ.

We do not know if the the pair of polished stone pillars were part of such celebrations or the representation of cosmic metaphors of Skambha Sukta स्कम्भसूक्तम् (Atharva veda Book 10 Hymn 7).

Profound evidences of religious/cultural continuum continuum is provided by the following:

1. the practice of wearing sindhur by married women. Two terracotta toys found in Nausharo (Mehergarh) showed two women wearing red vermilion (sindhur) at the parting of the black hair, a practice which continues even today in Bharatam.

2. the veneration of s'ankha (turbinella pyrum) as a pancajanya of Sri Krishna to call Bharatam Janam to arms. A burial of a woman in Nausharo showed her wearing s'ankha bangles and jewellery; the burial was dated to ca. 6500 BCE. Turbinella Pyrum shells used as trumpets were are discovered as archaeological artifacts.

It will be an error to reconstruct the ancient cultural mores of Bharatam Janam based on pre-judged categories such as Aryan or Dravidian or Munda (Austro-Asiatic) given the overwhelming evidence of an Indian sprachbund, a language union which united the three main language streams and the overwhelming legacy of Prakrit words, many with Samskritam/Chandas (Vedic) cognates, in all present-day languages of Bharatam. For example, 90% of the glosses in Tamil Lexicon (Madras University) contain Samskritam tatsama (cognate) or tadbhava (etyma). Over 11% Sanskrit glosses trace their links to Munda. (pace FBJ Kuipter). There is now sufficient evidence to prove the reality of the Indian sprachbundin an Indian Lexicon with over 8000 semantic clusters including Aryan-Dravidian-Munda glosses, thus questioning the rationale for separating the trio into separate etymological dictionaries.

Vedic River Sarasvati is also mentioned in the two Great Epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata. Mahabharata provides details of pariyatra of Sri Balarama along the River Sarasvati from Dwaraka to the origin in Plaksha Prasravana in Himalayan glaciers. The channels of this river also account for 80% of archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization on the banks of the two rivers: Sindhu and Sarasvati.

Hopefully, excavations of all the 2,500+ sites of the civilization will help unravel the cultural/religious practices of Bharatam Janam (Mleccha, Hindu) as the practices evolved over time from ca 5th millennium BCE of the Bronze Age. Further researches will unravel the links with the Kirata (Mleccha) janapada and Asura on Ganga basin and the evolution of technologies related to metalwork exemplified by the iron smelters found in Malhar, Raja-nal-ki-tila, Lohardiwa; the non-rusting iron pillar of Vidisha (Sanchi) now in Delhi; the cire perdue alloy metalcastings by dhokra kamar of Bastar or vis'vakarma artisans of Swamimalai in Tamil Nadu evoking the tradition which dates back to ca. 2500 BCE when the dancing girl bronze statue was cast or earlier to ca. 5th millennium BEC when the Nahal Mishmar cire perdue bronze castings were carried aloft in processions by artisans of the Bronze Age across Eurasia along the Tin Road from Meluhha to Mishmar.

It will also be an error to separate Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization and Vedic cuture, premised on erroneous pre-judged chronological sequencing. Sarasvati-Sindhu and Vedic cultures are two sides of the same cultural coin: one dominated by mleccha/meluhha people transacting in the lingua franca, working as Fire workers, excelling in metalcasting work and the other by Philosophers of Fire or Knowledge Explorers, engaged in tapasya and yoga on the links between Being and Becoming. The narrative, the Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam will provide a united narrative of the two converging streams of civilizational and technological advances, both related to enquiries into knowledge systems which found eternal expression in the twin founding ethical principles of Dharma-Dhamma.

In terms of chronology, it will be reasonable to date the textual evidence provided by chandas of Rigveda about two millennia prior to the earliest archaeological finds (ca. 3500 BCE) of Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization and archaeological finds in contact areas of Sumer-Mesopotamia from early Bronze Age.

A hypothesis is that the ethical duo of Dharma-Dhamma is the narrative of the Itihaasa of BharatamJanam over five millennia. The narrative has yet to be told as more researches and more archaeological explorations will continue to provide evidence to test this hypothesis.

Indus Script decipherment is, in effect, an imperative for scholars engaged in civilization studies, an essential contribution to the Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam, an expression used by Rishi Visvamitra in Rigveda (RV 3.53.12: viśvā́mitrasya rakṣati

My hypothesis is that Indus Script was a writing system based on Proto-Prakritam (called Meluhha/mleccha) to create Indus Script Corpora of about 7000 inscriptions as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork.

A remarkable corroborating evidence is provided by 342 symbols identified by W. Theobald on punch-marked coins, many of which are based on Indus Script prototypes. Many of these symbols are a continuum of the mint work which started and got documented on Indus Script Corpora which now includes over 7000 inscriptions spread over an extensive civilizational contact area in Eurasia.

Monographs of Theobald (1890, 1901) list 342 symbols deployed on punch-marked coins. These symbols also survive on later coinages of Ujjain or Eran or of many janapadas. One view is that early punch-marked coinage in Bharatam is datable to 10th century BCE, predating Lydia's electrum coin of 7th cent. BCE. “The coins to which these notes refer, though presenting neither king’s names, dates of inscription of any sort, are nevertheless very interesting not only from their being the earliest money coined in India, and of a purely indigenous character, but from their being stamped with a number of symbols, some of which we can, with the utmost confidence, declare to have originated in distant lands and inthe remotest antiquity…The coins to which I shall confine my remarks are those to which the term ‘punch -marked’ properly applies. The ‘punch’ used to produce these coins differed from the ordinary dies which subsequently came into use, in that they covered only a portion of the surface of the coin or ‘blank’, and impressed only one, of the many symbols usually seen on their pieces…One thing which is specially striking about most of the symbols representing animals is, the fidelity and spirit with which certain portions of it may be of an animal, or certain attitudes are represented…Man, Woman, the Elephant, Bull, Dog, Rhinoceros,Goat, Hare, Peacock, Turtle, Snake, Fish, Frog, are all recognizable at a glance…First, there is the historical record of Quintus Curtius, who describes the Raja of Taxila (the modern Shahdheri, 20miles north-west from Rawal Pindi) as offering Alexander 80 talents of coined silver (‘signati argenti’). Now what other, except these punch-marked coins could these pieces of coined silver have been? Again, the name by which these coins are spoken of in the Buddhist sutras, about 200 BCE was ‘purana’, which simply signies ‘old’, whence the General argunes that the word ‘old as applied to the indigenous ‘karsha’,was used to distinguish it from the new and more recent issues of the Greeks. Then again a mere comparison of the two classes of coins almost itself suffices to refute the idea of the Indian coins being derived from the Greek. The Greek coins present us with a portrait of the king, with his name and titles in two languages together with a great number and variety of monograms indicating, in many instances where they have been deciphered by the ingenuity and perseverance of General Cunningham and others, the names of the mint cities where the coins were struck, and it is our ignorance of the geographical names of the period that probably has prevented the whole of them receiving their proper attribution; but with the indigenous coins it is far otherwise, as they display neither king’s head, neame, titles or mongrams of any description…It is true that General Cunningham considers that many of these symbols, though not monograms in a strict sense, are nevertheless marks which indicate the mints where the coins were struck or the tribes among whom they were current, and this contention in no wise invalidates the supposition contended for by me either that the majority of them possess an esoteric meaning or have originated in other lands at a period anterior to the

ir adoption for the purpose they fulfil on the coins in Hindustan.”

ir adoption for the purpose they fulfil on the coins in Hindustan.”

(W. Theobald, 1890, Notes on some of the symbols found on the punch-marked coins of Hindustan, and on their relationship to the archaic symbolism of other races and distant lands, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Bombay Branch (JASB), Part 1. History , Literature etc., Nos. III & IV, 1890, pp. 181 to 184) W. Theobald, Symbols on punch-marked coins of Hindustan (1890,1901).

Many hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora continue to be used in historical periods:

[Pl. 39, Tree symbol (often on a platform) on punch-marked coins; a symbol recurring on many Indus script tablets and seals.] Source for the tables of symbols on punchmarked coins: Savita Sharma, 1990, Early Indian Symbols, Numismatic Evidence, Delhi, Agam Kala Prakashan.

Tree shown on a tablet from Harappa. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

From a review of Indus Script Corpora of nearly 7000 inscriptions, the nature of Indus writing system is defined, while validating decipherment as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork by Bronze Age artisans of Indian sprachbund.

From a review of Indus Script Corpora of nearly 7000 inscriptions, the nature of Indus writing system is defined, while validating decipherment as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork by Bronze Age artisans of Indian sprachbund.

See: Fabri, CL, The punch-marked coins: a survival of the Indus Civilization, 1935, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press. pp.307-318. A comparison of Punch-marked hieroglyphs with Indus Script inscriptions:

This follows the insightful, scintillating presentation by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale which presents an exposition of art appreciation of Indus Script Corpora with particular reference to orthographic fidelity to signify hypertext components on inscriptions. A paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html In this post, it has been argued that the hypertexts of pictorial motifs on Indus Script Corpora discussed by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale should be extended to hieroglyphs as 'signs' and ligatured hieroglyphs as 'signs' on 'texts' of the Indus inscriptions. The entire Indus Script Corpora consist of hieroglyph multiplexes -- using hieroglyphs as components -- and hence, the comparison with hypertexts need not be restricted to pictorial motifs or field symbols of Indus inscriptions. See also: Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).Mirror: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/document-preview.aspx?doc_id=9163376 The use of the phrase 'hypertexts' in the context of Indus Script is apposite because, the entire Indus Script Corpora is founded on rebus-metonymy-layered representations of Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund, speech area of ancient Bhāratam Janam of the Bronze Age.

Arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale

The arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale are framed taking the example of a Mohenjo-daro seal m0300 with what they call 'symbolic hypertext' or, 'Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components':

The arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale are framed taking the example of a Mohenjo-daro seal m0300 with what they call 'symbolic hypertext' or, 'Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components':

m0300. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components. Harappan chimera and its hypertextual components. The 'expression' summarizes the syntax of Harappan chimeras within round brackets, creatures with body parts used in their correct anatomic position (tiger, unicorn, markhor goat, elephant, zebu, and human); within square brackets, creatures with body parts used to symbolize other anatomic elements (cobra snake for tail and human arm for elephant proboscis); the elephant icon as exonent out of the square brackets symbolizes the overall elephantine contour of the chimeras; out of brackes, scorpion indicates the animal automatically perceived joining the lineate horns, the human face, and the arm-like trunk of Harappan chimeras. (After Fig. 6 in: Harappan chimaeras as 'symbolic hypertexts'. Some thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization (Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale, 2012)

Framework and Functions of Indus Script

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

The framework of Indus Script has two structures: 1) pictorial motifs as hieroglyph-multiplexes; and 2) text lines as hieroglyph-multiplexes

Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale focus attention on pictorial motifs and on m0300 seal, identify a number of hieroglyph components constituting the hieroglyph-multiplex -- on the pictorial motif of 'composite animal', seen are hieroglyph components (which they call hypertextual components): serpent (tail), scorpion, tiger, one-horned young bull, markhor, elephant, zebu, standing man (human face), man seated in penance (yogi).

The yogi seated in penance and other hieroglyphs are read rebus in archaeometallurgical terms: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) rebus: kampaTTa 'mint'. Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger', xolA 'tail' rebus:kol 'working in iron'; kolle 'blacksmith'; kolhe 'smelter'; kole.l 'smithy'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'. खोड [khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) rebus: khond 'turner'. dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'minerals'.bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'stone ore'. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus:meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛhet iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) kara'elephant's trunk' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith'; ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'. Together: karaibā 'maker, builder'.

Use of such glosses in Meluhha speech can be explained by the following examples of vAkyam or speech expressions as hieroglyph signifiers and rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher yielding signified metalwork:

Examples: Hieroglyph-multiplexes as hypertexts

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

Example 1: mũh ‘face’ in almost all languageds of Indian sprachbund Rebus: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali)mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt= iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Samskritam) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam glossmleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

The framework of Indus Script has two structures: 1) pictorial motifs as hieroglyph-multiplexes; and 2) text lines as hieroglyph-multiplexes

Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale focus attention on pictorial motifs and on m0300 seal, identify a number of hieroglyph components constituting the hieroglyph-multiplex -- on the pictorial motif of 'composite animal', seen are hieroglyph components (which they call hypertextual components): serpent (tail), scorpion, tiger, one-horned young bull, markhor, elephant, zebu, standing man (human face), man seated in penance (yogi).

The yogi seated in penance and other hieroglyphs are read rebus in archaeometallurgical terms: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) rebus: kampaTTa 'mint'. Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger', xolA 'tail' rebus:kol 'working in iron'; kolle 'blacksmith'; kolhe 'smelter'; kole.l 'smithy'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'. खोड [khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) rebus: khond 'turner'. dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'minerals'.bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'stone ore'. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus:meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛhet iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) kara'elephant's trunk' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith'; ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'. Together: karaibā 'maker, builder'.

Use of such glosses in Meluhha speech can be explained by the following examples of vAkyam or speech expressions as hieroglyph signifiers and rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher yielding signified metalwork:

Examples: Hieroglyph-multiplexes as hypertexts

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

Example 1: mũh ‘face’ in almost all languageds of Indian sprachbund Rebus: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali)mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt= iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends;kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Samskritam) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam glossmleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

1. A good example of constructed orthography of hieroglyph multiplex is a seal impression from Ur identified by CJ Gadd and interpreted by GR Hunter:

Seal impression, Ur (Upenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6, ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5; Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the head (denoting supernatural?). The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. The parenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse (Hunter, G.R.,JRAS, 1932, 476). An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal. Hieroglyph: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron' (Santali) Hieroglyph: meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.) Thus, meḍ kuṭhi 'iron smelter'. (Parenthesis kuṭila is a phonetic determinan of the substantive gloss: kuṭhi 'smelter'. It could also denote a smelter for kuṭila, 'tin metal').

kuṭi కుటి : శంకరనారాయణతెలుగు-ఇంగ్లీష్నిఘంటువు 1953 a woman water-carrier.

Splitting the ellipse () results in the parenthesis, ( ) within which the hieroglyph multiplex (in this case of Ur Seal Impression, a water-carrier with stars flanking her head) is infixed, as noted by Hunter.

The ellipse is signified by Meluhha gloss with rebus reading indicating the artisan's competence as a professional: kōnṭa 'corner' (Nk.); kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Alternative reading; kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

kõdā is a metals turner, a mixer of metals to create alloys in smelters.

The signifiers are the hieroglyph components: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'; meḍha ‘polar star’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’; kōnṭa 'corner' rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal').

The entire hieroglyph multiplex stands deciphered: kõdā, 'metals turner' (with) meḍ ‘iron’ kuṭhi '

smelter', kuṭila, 'tin metal'.

2. This hieroglyph multiplex of the Ur Seal Impression confirms the rebus-metonymy-layered cipher of Meluhha glosses related to metalwork.

3. A characteristic feature of Indus writing system unravels from this example: what is orthographically constructed as a pictorial motif can also be deployed as a 'sign' on texts of inscriptions. This is achieved by a stylized reconstruction of the pictorial motif as a 'sign' which occurs with notable frequency on Indus Script Corpora -- with orthographic variants (Signs 12, 13, 14).

The ellipse is signified by Meluhha gloss with rebus reading indicating the artisan's competence as a professional: kōnṭa 'corner' (Nk.); kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Alternative reading; kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

kõdā is a metals turner, a mixer of metals to create alloys in smelters.

The signifiers are the hieroglyph components: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'; meḍha ‘polar star’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’; kōnṭa 'corner' rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal').

The entire hieroglyph multiplex stands deciphered: kõdā, 'metals turner' (with) meḍ ‘iron’ kuṭhi '

smelter', kuṭila, 'tin metal'.

2. This hieroglyph multiplex of the Ur Seal Impression confirms the rebus-metonymy-layered cipher of Meluhha glosses related to metalwork.

3. A characteristic feature of Indus writing system unravels from this example: what is orthographically constructed as a pictorial motif can also be deployed as a 'sign' on texts of inscriptions. This is achieved by a stylized reconstruction of the pictorial motif as a 'sign' which occurs with notable frequency on Indus Script Corpora -- with orthographic variants (Signs 12, 13, 14).

Signs 12 to 15. Indus script:![]()

Identifying Meluhha gloss for parenthesis hieroglyph or ( ) split ellipse: குடிலம்¹ kuṭilam, n. < kuṭila. 1. Bend curve, flexure; வளைவு. (திவா.) (Tamil) In this reading, the Sign 12 signifies a specific smelter for tin metal: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/ kuṭila, 'tin (bronze)metal; kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Samskritam) See: http://download.docslide.us/uploads/check_up03/192015/5468918eb4af9f285a8b4c67.pdf

It will be seen from Sign 15 that the basic framework of a water-carrier hieroglyph (Sign 12) is superscripted with another hieroglyph component, Sign 342: 'Rim of jar' to result in Sign 15. Thus, Sign 15 is composed of two hieroglyph components: Sign 12 'water-carrier' hieroglyph; Sign 342: "rim-of-jar' hieroglyph (which constitutes the inscription on Daimabad Seal 1).

kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe'

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.Each hieroglyph component of Sign 15 is read in rebus-metonymy-layered-meluhha-cipher: Hieroglyph component 1: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'. Hieroglyph component 2: kanka, kārṇī-ka 'rim-of-jar' rebus: kanka, kārṇī-ka m. ʻsupercargo of a shipʼ 'scribe'.

Ligatured hieroglyph 15 using two ligaturing components: 1. water-carrier; 2. rim-of-jar. The ‘rim-of-jar’ glyph connotes: furnace account (scribe). Together with the glyph showing ‘water-carrier’, the ligatured glyphs of kuṭi ‘water-carrier’ + ‘rim-of-jar’ can thus be read as: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka ‘smelting furnace account (scribe)’.

m1405 Pict-97 Person standing at the centre pointing with his right hand at a bison facing a trough, and with his left hand pointing to the Sign 15.

This tablet is a clear and unambiguous example of the fundamental orthographic style of Indus Script inscriptions that: both signs and pictorial motifs are integral components of the message conveyed by the inscriptions. Attempts at 'deciphering' only what is called a 'sign' in Parpola or Mahadevan corpuses will result in an incomplete decoding of the complete message of the inscribed object.

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.(Marathi)

pattar 'trough'; rebus pattar, vartaka 'merchant, goldsmith' (Tamil) பத்தர்² pattar

, n. < T. battuḍu. A caste title of goldsmiths; தட்டார் பட்டப்பெயருள் ஒன்று.

eraka 'raised arm' Rebus: eraka 'metal infusion' (Kannada. Tulu)

Sign 15: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka ‘smelting furnace account (scribe)’.

Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex on m1405 is read rebus from r.: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka eraka bharata pattar'goldsmith-merchant guild -- smelting furnace account (scribe), molten cast metal infusion, alloy of copper, pewter, tin.'

That a catalogue is a writing system should be obvious in the context of the story of evolution of writing during the Bronze Age in various cultures.

Some metalwork catalogue entries in Proto-Prakritam with hieroglyph-multiplexes as hypertexts are presented. It is essential to note that not merely ‘signs’ of texts but ‘pictorial motifs’ of inscriptions should be deciphered.

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot'

aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot' aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal' aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements'

aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements' aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge'

aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge' aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace'

aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace' aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'

aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge' aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting' aya tridhAtu 'fish+three strands of rope' Rebus: aya kolom dhatu 'metal/iron , three mineral ores'

aya tridhAtu 'fish+three strands of rope' Rebus: aya kolom dhatu 'metal/iron , three mineral ores' Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ See: अयस्कांत [ ayaskānta ] m S (The iron gem.) The loadstone. (Molesworth. Marathi) Fish + circumgraph of 4 (gaNDa) notches: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) The gloss kāṇḍa may also signify 'metal implements'. A cognate compound in Santali has: me~r.he~t khaNDa 'iron implements'.

Ayo ‘fish’; kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ See: अयस्कांत [ ayaskānta ] m S (The iron gem.) The loadstone. (Molesworth. Marathi) Fish + circumgraph of 4 (gaNDa) notches: ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) The gloss kāṇḍa may also signify 'metal implements'. A cognate compound in Santali has: me~r.he~t khaNDa 'iron implements'.Mohenjo-daro Seals m1118 and Kalibangan 032, glyphs used are: Zebu (bos taurus indicus), fish, four-strokes (allograph: arrow).ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) + kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) gaṆḌa, ‘four’ (Santali); Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’, ‘furnace’), arrow read rebus in mleccha (Meluhhan) as a reference to a guild of artisans working with ayaskāṇḍa ‘excellent quantity of iron’ (Pāṇini) is consistent with the primacy of economic activities which resulted in the invention of a writing system, now referred to as Indus Writing. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'.

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A Hieroglyph: kōḍ 'horn' Rebus: kōḍ 'place where artisans work, workshop' কুঁদন, কোঁদন [ kun̐dana, kōn̐dana ] n act of turning (a thing) on a lathe; act of carving (Bengali) कातारी or कांतारी (p. 154) [ kātārī or kāntārī ] m (कातणें ) A turner.(Marathi)

Rebus: खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver.

खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work.खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i (The intimations of a metals turner as a scribe are also gleaned from the gloss: खोडाखोड or डी [ khōḍākhōḍa or ḍī ] f (

That a metals turner is engaged in metal alloying is evident from the gloss: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit (as of phlegm, gore, curds, inspissated milk); any concretion or clot.

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'Sheorajpur, Dt. Kanpur. Three anthropomorphic figures of copper.

One anthropomorph had fish hieroglyph incised on the chest of the copper object, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

Text: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'

Pictorial motifs or hieroglyph-multiplexes: sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace' Rebus: sangar 'fortification' sanghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira) samghAta 'collection of articles (i.e. cargo)' PLUS khōṇḍa m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe 'young bullock' (Konda)Rebus: kõdā 'to turn in a lathe' (Bengali)

Text: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace' kaNDa 'arrow' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' kuTi 'curve' Rebus: kuTila 'bronze' kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

Pictorial motif or hieroglyph-multiplex: sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace' Rebus: sangar 'fortification' sanghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira) samghAta 'collection of articles (i.e. cargo)'

Seal.

Seal.kuTi 'curve' Rebus: kuTila 'bronze' (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin)

dATu 'cross' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral ore'

aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting' aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal' mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) PLUS (infixed) kolom 'sprout, rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' Thus, ingot smithy

mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) PLUS (infixed) kolom 'sprout, rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' Thus, ingot smithy kuTi 'curve' Rebus: kuTila 'bronze'

ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali)

kolom 'rice-plant, sprout' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Alternative: kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter')

kolom 'rice-plant, sprout' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Alternative: kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter')kaṇḍa kanka ‘rim of jar’ Rebus: karṇīka ‘account (scribe)’karṇī‘supercargo’.

kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’.

A painted goblet. Ficus leaves. Nausharo ID. c. 2600-2550 BCE (After Samzun. Anaick, 1992, Observations on the characteristisc of the Pre-Harappan remains, pottery, and artifacts at Nausharo, Pakistan (2700-2500 BCE), pp. 245-252 in: Catherine Jarrige ed. South Asian Archaeology 1989 (Monographs in World Archaeology 14, Madison, Wisconsin, Prehistory Press: 250, fig. 29.4 no.2)

Inscribed pots. Mundigak IV, 1 (eastern Afghanistan), after Casal 1961: II, fig. 64, nos. 167, 169, 172. Courtesy: Delegation archeologique francaise en Afghanistan. Ficus leaves.

Harappa seal. Harappa excavation no. 13751. Harappa museum. Courtesy: Dept. of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of Pakistan

rimless pot: baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

tri-dhAtu, three minerals: tridhAtu 'three strands of rope' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral ore' (three ores)

oval ingot: DhALako 'large ingot'

Mohenjo-daro. Copper plate. obverse. Excavation no. E 214-215. Courtesy. ASI. Purana Qila, New Delhi.

rimless pot: baTa 'rimless pot' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

tri-dhAtu, three minerals: tridhAtu 'three strands of rope' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral ore' (three ores)

kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Mohenjodaro. Tablet. Crocodile + fish DK 8037. E 2500 Purana Qila, New Delhi. ASI.

Mohenjodaro. Tablet.

Mohenjodaro. Tablet.

Mohenjodaro. Tablet. Crocodile + fish. ASI. National Museum, New Delhi.

Hieroglyph-multiplex: aya 'fish' + kara 'crocodile' Rebus: ayakara 'metalsmith'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' PLUS meḍha '

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' PLUS meḍha 'Cylinder seal. Water flowing from the shoulder. Stars.

Santali glosses. Lexis.

Santali glosses. Lexis.meḍha '

m 305 Seal. Mohenjo-daro.

Fish + scales, aya ã̄s (amśu) ‘metallic stalks of stone ore’. Vikalpa: badhoṛ ‘a species of fish with many bones’ (Santali) Rebus: baḍhoe ‘a carpenter, worker in wood’; badhoria ‘expert in working in wood’(Santali)

gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' Together with cognate ancu 'iron' the message is: native metal implements.

Pictorial hieroglyph-multiplex: kuThi 'twig' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter' thattAr 'buffalo horn' Rebus: taTThAr 'brass worker' meḍha '

Indian mackerel Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai 'loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayila 'a kind of fish'. Ma. ayala 'a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish' ayira a kind of small fish, loach (DEDR 191) Munda: So. Ayo `fish'. Go. ayu `fish'. Go <ayu> (Z), <ayu?u> (Z),, <ayu?> (A) {N} ``^fish''. Kh. kaDOG `fish'. Sa. Hako `fish'. Mu. hai(H) ~ haku(N) ~ haikO(M) `fish'. Ho haku `fish'. Bj. hai `fish'. Bh.haku `fish'. KW haiku ~ hakO |Analyzed hai-kO, ha-kO (RDM). Ku. Kaku`fish'.@(V064,M106) Mu. ha-i, haku `fish' (HJP). @(V341) ayu>(Z), <ayu?u> (Z) <ayu?>(A) {N} ``^fish''. #1370. <yO>\\<AyO>(L) {N} ``^fish''. #3612. <kukkulEyO>,,<kukkuli-yO>(LMD) {N} ``prawn''. !Serango dialect. #32612. <sArjAjyO>,,<sArjAj>(D) {N} ``prawn''. #32622. <magur-yO>(ZL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. *Or.<>. #32632. <ur+GOl-Da-yO>(LL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. #32642.<bal.bal-yO>(DL) {N} ``smoked fish''. #15163. Vikalpa: Munda: <aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.#10171. So<aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.

aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.) aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). Ta. ayil javelin, lance, surgical knife, lancet.Ma. ayil javelin, lance; ayiri surgical knife, lancet. (DEDR 193). aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Ta.); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Ma.) Kur. adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Malt. adru broken grain (DEDR 134). Ma. aśu thin, slender;ayir, ayiram iron dust.Ta. ayir subtlety, fineness, fine sand, candied sugar; ? atar fine sand, dust. அய.ர³ ayir, n. 1. Subtlety, fineness; நணசம. (த_வ_.) 2. [M. ayir.] Fine sand; நணமணல. (மலசலப. 92.) ayiram, n. Candied sugar; ayil, n. cf. ayas. 1. Iron; 2. Surgical knife, lancet; Javelin, lance; ayilavaṉ, Skanda, as bearing a javelin (DEDR 341).Tu. gadarů a lump (DEDR 1196) kadara— m. ‘iron goad for guiding an elephant’ lex. (CDIAL 2711). অয়সঠন [ aẏaskaṭhina ] a as hard as iron; extremely hard (Bengali) अयोगूः A blacksmith; Vāj.3.5. अयस् a. [इ-गतौ-असुन्] Going, moving; nimble. n. (-यः) 1 Iron (एतिचलतिअयस्कान्तसंनिकर्षंइतितथात्वम्; नायसोल्लिख्यतेरत्नम् Śukra 4.169.अभितप्तमयो$पिमार्दवंभजतेकैवकथाशरीरिषु R.8.43. -2 Steel. -3 Gold. -4 A metal in general. ayaskāṇḍa 1 an iron-arrow. -2 excellent iron. -3 a large quantity of iron. -क_नत_(अयसक_नत_) 1 'beloved of iron', a magnet, load-stone; 2 a precious stone; ˚मजण_ a loadstone; ayaskāra 1 an iron-smith, blacksmith (Skt.Apte) ayas-kāntamu. [Skt.] n. The load-stone, a magnet. ayaskāruḍu. n. A black smith, one who works in iron. ayassu. n. ayō-mayamu. [Skt.] adj. made of iron (Te.) áyas— n. ‘metal, iron’ RV. Pa. ayō nom. sg. n. and m., aya— n. ‘iron’, Pk. aya— n., Si. ya. AYAŚCŪRṆA—, AYASKĀṆḌA—, *AYASKŪṬA—. Addenda: áyas—: Md. da ‘iron’, dafat ‘piece of iron’. ayaskāṇḍa— m.n. ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ Pāṇ. gaṇ. viii.3.48 [ÁYAS—, KAA ́ṆḌA—]Si.yakaḍa ‘iron’.*ayaskūṭa— ‘iron hammer’. [ÁYAS—, KUU ́ṬA—1] Pa. ayōkūṭa—, ayak m.; Si. yakuḷa‘sledge —hammer’, yavuḷa (< ayōkūṭa) (CDIAL 590, 591, 592). cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa; Old Germ. e7r , iron ;Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.

S. Kalyanaraman, Sarasvati Research Centre

August 27, 2015