Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/nq5fgsx

Supercargo, signified by multiple seal impressions on claytags: evidence from Lothal and Kalibangan

This note demonstrate the statistical fallacy and negation of the rules of grammar suggesting a count of number of 'signs' on an Indus inscription and offer a prize for the discoverer of more than 50 signs to prove that the inscription is a writing system of a language.

The archaeological finds of claytags with seal impressions at Lothal are enough to disprove the statistical fallacy of the proponents of Sarasvati-Sindhu as an illiterate civilization. A combination of claytags produce more than a hundred 'signs', without even reckoning the meaning of the hieroglyph-multiplexes of one-horned young bull PLUS standard device..

The occurrence of a claytag with multiple seal impressions in itself does not justify treating that particular claytag as a unit of meaning. It is possible that the archaeological evidence has failed to reckong other related claytags with similar multiple seal impressions to comprehend the purport of the messaging system of claytags for parts of supercargo or shipment as trans-border consignment taken by a seafaring merchant, say, from Lothal or Kalibangan to Ur or Susa in Ancient Near East, across the Persian Gulf.

The comprehension of meaning of a set of inscriptions is comparable to the postulates of Bhartrhari in VAkyapadIya for sentence of a language as a unit of meaning and not merely a set of words in the sentence:

"A word consists of its phonetic-part and its meaning-part. The speaker's mind first chooses the phonetic element and then employs it to convey a meaning. The listener also first takes in the phonetic element and then passes on the meaning part. (I.50-53). A word has to be first heard, before it can convey a meaning (I.55-57)...The meaning of the sentence comes as a flash of insight (pratibhA). In it individual word-meanings appear as parts, but the whole is simply not a sum-total of the parts. This pratibhA or flash of insight is not a mere piece of knowledge, it is wisdom which guides man to right conduct (itikartavyatA) (II.144-152). The ultimate source of all word-meaning, primary, secondary or incidental is the sentence, it is derived and abstracted from the sentence. (344-351)...The component clauses (of compound sentence) are recognised only after the compound sentenced is totally uttered and comprehended, the meaning of the component sentence is a subsequent abstraction following the comprehension of the meanin of the compound sentence (389-390)...language cannot describe the intrinsic nature of things, although we know things only in the form in which words describe them (431-437)..."

K. Raghavan Pillai, 1971, The VAkyapadIya, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass

I suggest that the 100+ claytags found at a burnt-down warehouse at Lothal should be taken as a composite unit of meaning: the inscriptions on the tags conveyed 'lists' of supercargo items of trade, describing the metalwork or technical specifications of the bill of lading. If the claytag information is truncated to each line of a seal impression as a unit of meaning, the message is likely to be decoded erroneously with incomplete details of the message intended by the originator of the ciphertext using hypertexts of hieroglyph-multiplexes -- a signature tune of the Indus Script writing system.

How does a compiler of Indus Script Corpora reckon the number of 'signs' on an Indus Script inscription? What is an inscription? Is it restricted only to hieroglyphs or hieroglyph-multiplexes on a seal or a tablet?

Why not a combination of seals or tablets or clay tags with seal impression/s to reconstruct the message conveyed by the artisan who originated the message?

The ultimate objective is to decipher the contents of the supercargo described by the writing system and NOT to prove or disprove if the writing system displayed literacy or illiteracy (i.e. if the writing system was founded on the sounds or speech form of a language).

If one reckons all the hieroglyph-multiplexes of the clay tags of Lothal warehouse, the number of 'signs' will total hundreds.

"More than a hundred clay tags with ancient seal impressions come from a burnt-down grain warehouse at the Harappan port town of Lothal. Many of these tags also bear impressions of woven cloth, reed matting or other packing material. This shows that the tags were once attached to bales of goods, and that the seals were used, as in ancient West Asia, for controlling economic transactions." Asko Parpola http://www.harappa.com/script/parpola16.html

"Lothal. As many as 65 terracotta sealings recovered from the warehouse bore impressions of Indus seals on the obverse and of packing material such as bamboo matting, reed, woven cloth and cord on the reverse. substantial part of the warehouse was destroyed in P,III and was never rebuilt. All this elaborate infrastructure for external trade amply reflected in other finds from Lothal. A circular steatite seal of the class known as Persian Gulf seal (Bibby, 1958, pp. 243-4; Wheeler, 1958, p. 246; Rao 1963, p. 37), found aqundantly at Failaka and Rasal Qaila (Bahrain) on the Persian Gillf, is a surface find at Lothal, evidently the Persain Gulf sites were inter mediary in the Indus trade with Mesopotamia. Conversely some of the Indus-like seals found it Mesopotamia may have been imports from Lothal. A bun-shaped copper ingot, weighing 1.438 kg follows the shape, size and weight of Susa ingots, with which tht Lothal specimen shares the lack of arsenic in its composition. In addition to the Indus stone cubes of standard weights. Lothal had another series of weights conforming to the Heavy Assyrian standard for international trade." http://asi.nic.in/asi_exca_imp_gujarat.asp

One interpretation for seal impressions on clay tags of packages is that they constitute segments of messages related to bills of lading of traded goods.

Assuming that seal impressions were authentication of packages of consignments, part of supercargo, of a trade transaction, how to identify the message and decipher the meaning from a set of multiple seal impressions?

The basic unit of information in Indus Script inscriptions is a hieroglyph.

Hieroglyph-multiplexes are combined units of information, combining meanings of hieroglyph components.

Information can be conveyed by more than one hieroglyph on more than one Indus Script seal or tablet, though each seal or tablet may carry an average of 5 or 6 signs, often together with a pictorial hieroglyh-multiplex (such as a young bull in front of a standard device).

Similarly, more than one seal impression may signify a supercargo, karNI, signified by the semantic determinative hieroglyph: rim of narrow-necked jar.

Such seal impression messages may be restricted, containing only descriptions of the trade goods. Such messages may not not indicate names of trading partners or destinations of the packages.

Lothal has yielded 27 such multiple impressions, perhaps, on one package. These are examples which demonstrate that long texts of inscriptions can be created by combining texts from multiple seals even though the average number of hieroglyphs is about 5 or 6 per inscribed object. It all depends on the multiplicity of the contents of the package described by the seal impressions as bills of lading.

Should each line be reckoned and read as a disinct text unit? Or, should all the lines of a seal impression on all clay tags of a warehouse be reckoned as the message?

The answer to these questions are crucial to determine the length of 'hieroglyhs' deployed for a message.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

m0425 Seal impression with three 'tags' from three seals is an example of such assemblage of messages to complete the detailed description of goods in a trade package.

Thus, it is clear that the seal impressions are likely to be more complete assemblage of messages for preparing bills of lading. This assemblage uses the descriptions of goods achieved through multiple tablets used as tallies for compiling the bill of lading.

It is clear that multiple seal impressions complete the process of compiling the details needed for a bill of lading and contain complete descriptions of the trade consignments loads since the compilation is an assemblage of inscriptions of individual seals.

The Indus writing was mainly used to provide a detailed description of the goods in packages and seal impressions served as parts of bills of lading.

Use of seals to create sealings: context trade with interaction areas such as Mesopotamia

Archaeological finds of tablets (sometimes called bas-relief tablets or incised miniature tablets) and seals are in association with kilns and working platforms. Metallurgical context is shown by the use of copper to create tablets with Indus script hieroglyphs. Archaeological finds of seal impressions used as tags on chunks of burnt clay for sealing packages (since textile or reed impressions have been found on the obverse of such tags) show the trade context in which these examples of Indus writing have been used. About 32% of all Indus inscriptions found at Lothal are on such tags (seal impressions).

Lothal seal impression created by inscriptions from three seals. L211. Fifteen hieroglyphs

Line 1: Turner's workshop, metal ingot, metal (iron) workshop, furnace scribe (account)

Line 2: (...)workshop, cast metal, copper (metal), furnace scribe (account)

Line 3: (...), furnace scribe account - native metal, metal ingot, warehouse, casting smithy/forge, furnace scribe account

Detailed decoding rebus readings:

Line 1

koḍi ‘flag’ (Ta.)(DEDR 2049). Rebus: koḍ, ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi.) kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.)

sal ‘splinter’; rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali)

Fish + sloping stroke, aya dhāḷ ‘metal ingot’ (Vikalpa: ḍhāḷ = a slope; the inclination of a plane (G.) Rebus: : ḍhāḷako = a large metal ingot (G.)

meḍ 'body' (Mu.); rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Ho.)ḍabe, ḍabea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) Thus, horned body hieroglyph decodes rebus: ḍab meḍ 'iron (metal) ingot'.

kaṇḍa kanka ‘furnace scribe (account)’ kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured sign is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe

Line 2

aya 'fish' (Mu.); rebus: aya 'metal' (G.)

dula 'pair' (Kashmiri); rebus: dul 'cast (metal)'

loa ‘ficus religiosa’ (Santali) rebus: loh ‘metal’ (Skt.) Rebus: lo ‘copper’. Thus, dul loh ‘cast copper’

kaṇḍa kanka ‘furnace scribe (account)’kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured sign is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe

Line 3

kaṇḍa kanka ‘furnace scribe (account)’ kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured sign is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe

aṭar ‘a splinter’; aṭaruka ‘to burst, crack, sli off,fly open; aṭarcca ’ splitting, a crack’; aṭar ttuka ‘to split, tear off, open (an oyster) (Ma.); aḍaruni ‘to crack’ (Tu.) (DEDR 66)

Rebus: aduru ‘native, unsmelted metal’ (Kannada)

Fish + scales aya ãs (amśu) ‘metllic stalks of stone ore

Kalibangan seal impression multiplex created by inscriptions from five seals Kalibangan089

Kalibangan089. Multiple seal impression. 17 hieroglyphs are recognized in the impressions created by multiple (perhaps four or five) seals.

An example of 'sealing' is presented by Mackay. Mackay, EJH, 1938, Further Excavations at Mohenjodaro, Vol. II, New Delhi, Government of India, Pl. XC, no. 17. Note: "No. 17 in Pl. XC is certainly a true sealing (i.e. a clay seal impression) and it owes its preservation to having been slightly burnt; it was once fastened to some such object as a smooth wooden rod." (Mackay,ibid.,1938, Vol. I, p. 349). One can only conjecture as to the reason why a pair of seal impressions were created on clay around a wooden rod: perhaps, the rod served as the bill of lading for a particular category of goods/artifacts. The three hieroglyphs can be read rebus. The set of three hieroglyphs is read rebus as: bhaṭa ḍab ranku ‘furnace ingot tin’. Hieroglyph 1: A hieroglyphic ligature is the ‘ladle or spoon’ hieroglyph (ligatured to the ‘pot’ hieroglyph). ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched (S.) Rebus: baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (G.) baṭa = kiln (Santali). Thus the ligatured glyph of ‘pot + spoon’ reads rebus: ḍab ‘(furnace) ingot’. Hieroglyph 2: Hieroglyph of rectangle with divisions: baṭai = to divide, share (Santali) [Note the hieroglyphs of nine rectangles divided.] Rebus: bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace (Santali) baṭhi furnace for smelting ore (the same as kuṭhi) (Santali) bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace; make an oven, a furnace; iṭa bhaṭa = a brick kiln; kun:kal bhaṭa a potter's kiln; cun bhaṭa = a lime kiln; cun tehen dobon bhaṭaea = we shall prepare the lime kiln today (Santali); bhaṭṭhā (H.) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhart-īyā = a barzier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Skt.) me~r.he~t bat.i = iron (Ore) furnaces. [Synonyms are: mẽt = the eye, rebus for: the dotted circle (Santali.lex) baṭha [H. baṭṭhī (Sad.)] any kiln, except a potter’s kiln, which is called coa; there are four kinds of kiln: cunabat.ha, a lime-kin, iṭabaṭha, a brick-kiln, ērēbaṭha, a lac kiln, kuilabaṭha, a charcoal kiln; trs. Or intrs., to make a kiln; cuna rapamente ciminaupe baṭhakeda? How many limekilns did you make? baṭha-sen:gel = the fire of a kiln; baṭi [H. Sad. baṭṭhi, a furnace for distilling) used alone or in the cmpds. Arkibut.i and bat.iora, all meaning a grog-shop; occurs also in ilibaṭi, a (licensed) rice-beer shop (Mundari.lex.) bhaṭi = liquor from mohwa flowers (Santali) Hieroglyph 3: ranku ‘liquid measure’; rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

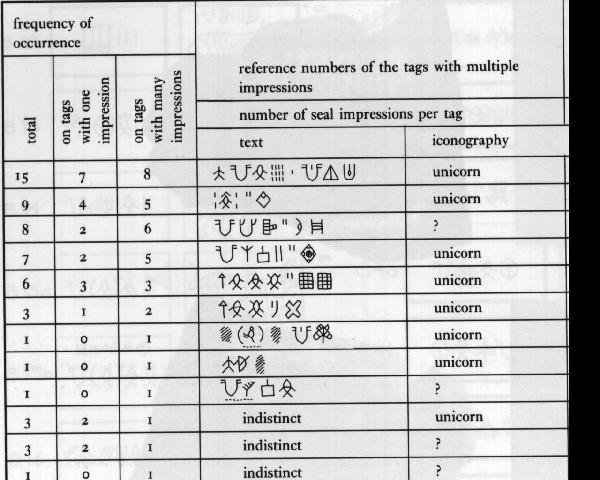

Analysis of clay tags with seal impressions at a burnt-down warehouse in Lothal; of the 77 tags, 21 bear 2, 3 or 4 seal impressions; nine seal texts can be read on 14 of these 21 tags which share seal impressions. Parpola, 1994, p. 114.Image may be NSFW.

Analysis of clay tags with seal impressions at a burnt-down warehouse in Lothal; of the 77 tags, 21 bear 2, 3 or 4 seal impressions; nine seal texts can be read on 14 of these 21 tags which share seal impressions. Parpola, 1994, p. 114.Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Group of incised baked steatite tablets. A group of 16 three-sided incised baked steatite tablets, all with the same inscriptions, were uncovered in mid- to late Period 3B debris outside of the curtain wall. (See 146). These tablets may originally been enclosed in a perishable container such as a small bag of cloth or leather.Image may be NSFW.

Group of incised baked steatite tablets. A group of 16 three-sided incised baked steatite tablets, all with the same inscriptions, were uncovered in mid- to late Period 3B debris outside of the curtain wall. (See 146). These tablets may originally been enclosed in a perishable container such as a small bag of cloth or leather.Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Life and death of Harappan seals and tablets. An additional six copies of these tablets, again all with the same inscriptions, were found elsewhere in the debris outside of perimeter wall [250] including two near the group of 16 and two in debris between the perimeter and curtain walls. Here all 22 tablets are displayed together with a unicorn intaglio seal from the Period 3B street inside the perimeter wall, which has two of the same signs as those found on the tablets. (See also145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150). Quoting from R.H. Meadow and J.M. Kenoyer's article in South Asian Archaeology 1997 (Rome, 2001): "It is tempting to think that the evident loss of utility and subsequent discard of the tablets is related to the “death” of the seal. Seals are almost always found in trash or street deposits (and never yet in a grave) indicating that they were either lost or intentionally discarded, the latter seeming the more likely in most instances. The end of the utility of a seal must relate to some life event of its owner, whether change of status, or death, or the passing of an amount of time during which the seal was considered current. A related consideration is that apparently neither seals nor tablets could be used by just anyone or for any length of time because otherwise they would not have fallen out of circulation. Thus the use of seals -- and of tablets -- was possible only if they were known to be current. Once they were no longer current, they were discarded. This would help explain why a group of 16 (or 18) tablets with the same inscriptions, kept together perhaps in a cloth or leather pouch, could have been deposited with other trash outside of the perimeter wall of Mound E."Period 3B debris related to: c. 2450 BCE - c. 2200 BCE.Examples of 31 duplicates, double-sided terracotta tabletsImage may be NSFW.

Life and death of Harappan seals and tablets. An additional six copies of these tablets, again all with the same inscriptions, were found elsewhere in the debris outside of perimeter wall [250] including two near the group of 16 and two in debris between the perimeter and curtain walls. Here all 22 tablets are displayed together with a unicorn intaglio seal from the Period 3B street inside the perimeter wall, which has two of the same signs as those found on the tablets. (See also145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150). Quoting from R.H. Meadow and J.M. Kenoyer's article in South Asian Archaeology 1997 (Rome, 2001): "It is tempting to think that the evident loss of utility and subsequent discard of the tablets is related to the “death” of the seal. Seals are almost always found in trash or street deposits (and never yet in a grave) indicating that they were either lost or intentionally discarded, the latter seeming the more likely in most instances. The end of the utility of a seal must relate to some life event of its owner, whether change of status, or death, or the passing of an amount of time during which the seal was considered current. A related consideration is that apparently neither seals nor tablets could be used by just anyone or for any length of time because otherwise they would not have fallen out of circulation. Thus the use of seals -- and of tablets -- was possible only if they were known to be current. Once they were no longer current, they were discarded. This would help explain why a group of 16 (or 18) tablets with the same inscriptions, kept together perhaps in a cloth or leather pouch, could have been deposited with other trash outside of the perimeter wall of Mound E."Period 3B debris related to: c. 2450 BCE - c. 2200 BCE.Examples of 31 duplicates, double-sided terracotta tabletsImage may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h252A Inscription on one side of the 2-sided tablet (in bas relief). The other side shows a one-horned heifer (as in h254B).Image may be NSFW.

h252A Inscription on one side of the 2-sided tablet (in bas relief). The other side shows a one-horned heifer (as in h254B).Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h254B. Two-sided tablet. The other side shows an inscription as in h252A.Examples of 22 duplicates steatite triangular tablets h-2218 to h-2239Image may be NSFW.

h254B. Two-sided tablet. The other side shows an inscription as in h252A.Examples of 22 duplicates steatite triangular tablets h-2218 to h-2239Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h2219A First side of three-sided tabletImage may be NSFW.

h2219A First side of three-sided tabletImage may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h2219B Second side of three-sided tabletImage may be NSFW.

h2219B Second side of three-sided tabletImage may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h2219C Third side of three-sided tabletThe two hieroglyphs which appear on the h2219A example also appear on a seal. "In a street deposit of similar age just inside the wall, a seal was found with two of the same characters as seen on one side of the tablets."While the 22 tablets were meant to help in 'tallying' the products produced by the artisans, the seal was meant to be used in preparing a bill of lading for the 'consignment or cargo' of products to be couriered through containers.Image may be NSFW.

h2219C Third side of three-sided tabletThe two hieroglyphs which appear on the h2219A example also appear on a seal. "In a street deposit of similar age just inside the wall, a seal was found with two of the same characters as seen on one side of the tablets."While the 22 tablets were meant to help in 'tallying' the products produced by the artisans, the seal was meant to be used in preparing a bill of lading for the 'consignment or cargo' of products to be couriered through containers.Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

h1682A. The seal which contained the two hieroglyphs used on the 'tally' three-sided tablets. The seal showed a one-horned heifer + standard device and two segments of inscriptions: one segment showing the two hieroglyphs shown on one side of the 'tally' tablet; the other segment showing hieroglyphs of a pair of 'rectangle with divisions' + 'three long linear strokes'.Decoding a pair of hieroglyphs, a pair of 'rectangle with divisions': khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.); Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Skt.) Thus, reduplicated hieroglyph connotes dul kaṇḍ ‘casting furnace’. Vikalpa: khonḍu ‘divided into parts’ (Kashmiri)khonḍu । खण्डितः, विकलावयवः adj. (f. khünḍü 1, sg. dat. khanjĕ 1 खंज्य), broken, divided into parts; hence, deprived of a part or limb or member, maimed, mutilated; unevenly formed, irregularly angled. (Kashmiri) A pair of such hieroglyphs divided into parts, may thus be decoded as: dul kaṇḍ khonḍu khonḍ ‘casting furnace workshop’. Vikalpa 1: jaṇḍ khaṇḍ = ivory (Jat.ki) khaṇḍi_ = ivory in rough (Jat.ki_); gaṭī = piece of elephant's tusk (S.) Vikalpa 2: Pa.kandi (pl. -l) necklace, beads. Ga. (P.) kandi (pl. -l) bead, (pl.) necklace; (S.2)kandiṭ bead (DEDR 1215). kandil, kandīl = a globe of glass, a lantern (Ka.lex.) The pair of hieroglyphs 'rectangle with divisions' may thus also connote 'cast beads'. If so, the seal text inscription connotes two sets of products assembled for despatched through a courier: furnace metal products + furnace bead products.Both sets of products are from the sanga turner's workshop.Decoding the hieroglyph, 'three long linear strokes': ‘three’; rebus: ‘smithy’ (Santali)Hierolyph of standard device in front of the one-horned heifer: sā~gāḍī lathe (Tu.)(CDIAL 12859). sāṅgaḍa That member of a turner's apparatus by which the piece to be turned is confined and steadied. सांगडीस धरणें To take into linkedness or close connection with, lit. fig. (Marathi) सांगाडी [ sāṅgāḍī ] f The machine within which a turner confines and steadies the piece he has to turn. (Marathi)सगडी [ sagaḍī ] f (Commonly शेगडी) A pan of live coals or embers. (Marathi) san:ghāḍo, saghaḍī (G.) = firepan; saghaḍī, śaghaḍi = a pot for holding fire (G.)[culā sagaḍī portable hearth (G.)] sanghar 'fortification' samghAta 'adamantine glue (metal)'(Varahamihira)Thus, the entire set of hieroglyphs on the h1682A seal [denoting the heifer + standard device] can be decoded: koḍiyum 'heifer'; [ kōḍiya ] kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. . k* దూడA young bull. Plumpness, prime. తరుణము. జోడుకోడయలు a pair of bullocks. kōḍe adj. Young. kōḍe-kāḍu. n. A young man.పడుచువాడు. [ kārukōḍe ] kāru-kōḍe. [Tel.] n. A bull in its prime. खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) గోద [ gōda ] gōda. [Tel.] n. An ox. A beast. kine, cattle.(Telugu) koḍiyum (G.) rebus: koḍ ‘workshop’ (G.) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or. kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ‘lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) The two hieroglyphs (heifer + lathe) together thus refer to a turner's workshop with a portable hearth. The two sets of the text of the inscription refer to the products assembled together (perhaps on the circular working platforms) by this workshop of the guild. The sets of products denoted by the two sets of hieroglyphic sequences can be exlained rebus:kuṭi ‘water carrier’ (Te.) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛI f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) kuṭi ‘hut made of boughs’ (Skt.) guḍi temple (Telugu) kaṇḍa kanka 'rim of jar' (Santali); rebus: furnace scribe. kaṇḍa kanka may be a dimunitive form of *kan-khār ‘copper smith’ comparable to the cognate gloss: kaṉṉār ‘coppersmiths, blacksmiths’ (Tamil) If so, kaṇḍa kan-khār connotes: ‘copper-smith furnace.’kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.) kanka ‘Rim of jar’ (Santali); karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus: karNI 'supercargo', karṇaka ‘scribe’ (Te.); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) Thus, the 'rim-of-jar' hieroglyph connotes: furnace account (scribe). Together with the hieroglyph showing 'water-carrier', the ligatured hieroglyphs of 'water-carrier' + 'rim-of-jar' can thus be read as: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka 'smelting furnace account (scribe)'.Thus, the inscription on seal h1682A can be explained in the context of the tablets used as tally tokens to account for the despatch of the assembled products (delivered by the guild artisans) using the impression of the seal as a bill of lading. The use of tablets in conjunction with the seal has been elaborated. Once the accounting is completed using the seal and the seal impression on the package to be couriered, the tablets used as tallying instruments by the guild helper of merchant have served their purpose and can be disposed of in the debris.See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/12/indus-valley-mystery-and-use-of-tablets.html

h1682A. The seal which contained the two hieroglyphs used on the 'tally' three-sided tablets. The seal showed a one-horned heifer + standard device and two segments of inscriptions: one segment showing the two hieroglyphs shown on one side of the 'tally' tablet; the other segment showing hieroglyphs of a pair of 'rectangle with divisions' + 'three long linear strokes'.Decoding a pair of hieroglyphs, a pair of 'rectangle with divisions': khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.); Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Skt.) Thus, reduplicated hieroglyph connotes dul kaṇḍ ‘casting furnace’. Vikalpa: khonḍu ‘divided into parts’ (Kashmiri)khonḍu । खण्डितः, विकलावयवः adj. (f. khünḍü 1, sg. dat. khanjĕ 1 खंज्य), broken, divided into parts; hence, deprived of a part or limb or member, maimed, mutilated; unevenly formed, irregularly angled. (Kashmiri) A pair of such hieroglyphs divided into parts, may thus be decoded as: dul kaṇḍ khonḍu khonḍ ‘casting furnace workshop’. Vikalpa 1: jaṇḍ khaṇḍ = ivory (Jat.ki) khaṇḍi_ = ivory in rough (Jat.ki_); gaṭī = piece of elephant's tusk (S.) Vikalpa 2: Pa.kandi (pl. -l) necklace, beads. Ga. (P.) kandi (pl. -l) bead, (pl.) necklace; (S.2)kandiṭ bead (DEDR 1215). kandil, kandīl = a globe of glass, a lantern (Ka.lex.) The pair of hieroglyphs 'rectangle with divisions' may thus also connote 'cast beads'. If so, the seal text inscription connotes two sets of products assembled for despatched through a courier: furnace metal products + furnace bead products.Both sets of products are from the sanga turner's workshop.Decoding the hieroglyph, 'three long linear strokes': ‘three’; rebus: ‘smithy’ (Santali)Hierolyph of standard device in front of the one-horned heifer: sā~gāḍī lathe (Tu.)(CDIAL 12859). sāṅgaḍa That member of a turner's apparatus by which the piece to be turned is confined and steadied. सांगडीस धरणें To take into linkedness or close connection with, lit. fig. (Marathi) सांगाडी [ sāṅgāḍī ] f The machine within which a turner confines and steadies the piece he has to turn. (Marathi)सगडी [ sagaḍī ] f (Commonly शेगडी) A pan of live coals or embers. (Marathi) san:ghāḍo, saghaḍī (G.) = firepan; saghaḍī, śaghaḍi = a pot for holding fire (G.)[culā sagaḍī portable hearth (G.)] sanghar 'fortification' samghAta 'adamantine glue (metal)'(Varahamihira)Thus, the entire set of hieroglyphs on the h1682A seal [denoting the heifer + standard device] can be decoded: koḍiyum 'heifer'; [ kōḍiya ] kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. . k* దూడA young bull. Plumpness, prime. తరుణము. జోడుకోడయలు a pair of bullocks. kōḍe adj. Young. kōḍe-kāḍu. n. A young man.పడుచువాడు. [ kārukōḍe ] kāru-kōḍe. [Tel.] n. A bull in its prime. खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) గోద [ gōda ] gōda. [Tel.] n. An ox. A beast. kine, cattle.(Telugu) koḍiyum (G.) rebus: koḍ ‘workshop’ (G.) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or. kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ‘lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) The two hieroglyphs (heifer + lathe) together thus refer to a turner's workshop with a portable hearth. The two sets of the text of the inscription refer to the products assembled together (perhaps on the circular working platforms) by this workshop of the guild. The sets of products denoted by the two sets of hieroglyphic sequences can be exlained rebus:kuṭi ‘water carrier’ (Te.) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛI f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) kuṭi ‘hut made of boughs’ (Skt.) guḍi temple (Telugu) kaṇḍa kanka 'rim of jar' (Santali); rebus: furnace scribe. kaṇḍa kanka may be a dimunitive form of *kan-khār ‘copper smith’ comparable to the cognate gloss: kaṉṉār ‘coppersmiths, blacksmiths’ (Tamil) If so, kaṇḍa kan-khār connotes: ‘copper-smith furnace.’kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.) kanka ‘Rim of jar’ (Santali); karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus: karNI 'supercargo', karṇaka ‘scribe’ (Te.); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) Thus, the 'rim-of-jar' hieroglyph connotes: furnace account (scribe). Together with the hieroglyph showing 'water-carrier', the ligatured hieroglyphs of 'water-carrier' + 'rim-of-jar' can thus be read as: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka 'smelting furnace account (scribe)'.Thus, the inscription on seal h1682A can be explained in the context of the tablets used as tally tokens to account for the despatch of the assembled products (delivered by the guild artisans) using the impression of the seal as a bill of lading. The use of tablets in conjunction with the seal has been elaborated. Once the accounting is completed using the seal and the seal impression on the package to be couriered, the tablets used as tallying instruments by the guild helper of merchant have served their purpose and can be disposed of in the debris.See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/12/indus-valley-mystery-and-use-of-tablets.htmlS. KalyanaramanSarasvati Research CenterAugust 14, 2015