Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/qgghbrd

According to Zhang Guang-da, the name Yuezhi is a transliteration of their own name for themselves, the Visha ("the tribes") or Vèsh in modern Pashto meaning "divisions", being called the Vijaya in Tibetan.(History of civilizations of Central Asia, volume III: Zhang Guang-da, The city-states of the Tarim Basin, p. 284). Visha were vessā part of the four-fold grouping of a community in ancient times and principally engaged in trading activities in Meluhha caravans or as seafaring Meluhha: khattiyā brāhmaṇā vessā suddā (Pali).

According to Zhang Guang-da, the name Yuezhi is a transliteration of their own name for themselves, the Visha ("the tribes") or Vèsh in modern Pashto meaning "divisions", being called the Vijaya in Tibetan.(History of civilizations of Central Asia, volume III: Zhang Guang-da, The city-states of the Tarim Basin, p. 284). Visha were vessā part of the four-fold grouping of a community in ancient times and principally engaged in trading activities in Meluhha caravans or as seafaring Meluhha: khattiyā brāhmaṇā vessā suddā (Pali).

Yuezhi are usually identified with the Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι), named by Greek historians among the conquerors of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in the 2nd century BCE. (Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. p. 15.)

Who were the Tókharoi? They were túṣāra, tushara. Their lineage are likely to have been involved in the dissemination of Sanghata-sutra which is a very long Bauddham text mostly dealing with the merit accruing from reciting, copying, etc., the text itself, but containing a number of interesting parables. Many complete folios and numerous fragments are extant. The gloss sanghata is instructive. This is a rebus representation of the Indus script hieroglyph: sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace' which is frequently deployed to denote metalwork catalogs in Indus Script Corpora which are Meluhha texts written in mlecchita vikalpa, 'Meluhha cipher'. Varahamihira explains the phrase Vajra sanghAta as: 'adamantine glue' in archaeometallurgical terms which is consistent with the rendering of semantics of Bhāratam Janam as 'metalcaster folk' in Rigveda.

![Image result for standard lathe indus script]()

![Image result for indus hieroglyphs lathe portable furnace]()

![]() Sangar 'fortification', Afghanistan (evoking the citadels and fortifications at hundreds of archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization).

Sangar 'fortification', Afghanistan (evoking the citadels and fortifications at hundreds of archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization).

Sanghata Sutra (Ārya Sanghāta Sūtra; Devanagari, आर्य सङ्घाट सूत्र) is a Mahāyāna Buddhist scripture widely circulated in northwest India and Central Asia. Manuscripts of the Sanghāta have been recovered in Gilgit (in 1931 and 1938), Khotan, Dunhuang, and other sites in Central Asia along the silk route. Translations appear in Khotanese, Sogdian, Chinese, Tibetan and English. "In standard Sanskrit, sanghāta is a term meaning the ‘fitting and joining of timbers’ or ‘the work done by a carpenter in joining two pieces of wood,’ and can refer to carpentry in general. It has a specialized use in a few Buddhist Sanskrit texts, where it means ‘vessel’ or ‘jar,’ and this image of ‘something that contains’ is evoked several times within the sutra, when Buddha calls the Sanghāta a ‘treasury of Dharma.’

Source: History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 BCE to 250 CE, Unesco, p.399.

Contributors: A. H. Dani, UNESCO Staff, M. S. Asimov, B. A. Litvinsky, Guang-da Zhang, R. Shabani Samghabadi, C. E. Bosworth, Unesco, 01-Jan-1994 - 574 pages. Volume II presents an account of various population movements and cultural exchanges in Central Asia between 700 B.C. and 250 A.D. Important nomadic tribal cultures such as the Kushans emerged during this period. Contacts between the Mediterranean and the Indus Valley were reinforced by the campaigns of Alexander the Great and, under his successors, the progressive syncretism between Zoroastrianism, Greek religion and Buddhism gave rise to a new civilization instituted by the Parthians, known for its artistic creations. Under Kushan rule, Central Asia became the crossroads of a prosperous trade between the Mediterranean and China along the Silk Route.

Yuezhi were Tocharian-speakers. Christopher Beckwith's narrative on Central Eurasian history begins with the chariot warriors and the Proto-Indo-Europeans in the late 3rd millennium BCE. Christopher Beckwith argues that the character 月, usually read as Old Chinese *ŋʷjat > Mod. yuè, could have been pronounced in an archaic northwestern dialect as *tokwar or *togwar, a form that resembles the Bactrian name Toχοαρ (Toχwar ~ Tuχwar) and the medieval form Toχar ~ Toχâr.(Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press, page 5, footnote #16, as well as pages 380–383 in appendix B.) Christopher Beckwith "equates the Tokharians with the Yuezhi, and the Wusun with the Asvins, as if these are established facts, and refers to his arguments in appendix B. But these identifications remain controversial, rather than established, for most scholars." As succinctly sumamrised by Doug Hitch, Christopher Beckwith proposes three migratory waves of languages from Urheimat (the PIE homeland): wave A with one set of stop consonants (Tocharian, Anatolian), wave B with three (Germanic, Italic, Greek, Indic, Armenian), and wave C with two (Celtic, Slavic, Baltic, Albanian, Iranian)(p.365).(Hitch, Doug (2010). "Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present" in: Journal of the American Oriental Society 130 (4): 654–658.)

http://www.ynlc.ca/ynlc/staff/hitch/review_of_Beckwith.pdf (Embedded) https://www.scribd.com/doc/269518451/Review-of-Christopher-Beckwith-s-Empires-of-the-Silk-Road-A-history-of-central-Eurasdia-from-th-Bronze-Age-to-the-Present-JAOS-130-4-2010-pp-65

For the pronunciation of Mod. yuè, as *togwar (cognate túṣāra) see: Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 806.

Thus, yuè-zhi were indeed Tushara of Vedic texts,

Sanghata Sutra (Ārya Sanghāta Sūtra; Devanagari, आर्य सङ्घाट सूत्र) is a Mahāyāna Buddhist scripture widely circulated in northwest India and Central Asia. Manuscripts of the Sanghāta have been recovered in Gilgit (in 1931 and 1938), Khotan, Dunhuang, and other sites in Central Asia along the silk route. Translations appear in Khotanese, Sogdian, Chinese, Tibetan and English. "In standard Sanskrit, sanghāta is a term meaning the ‘fitting and joining of timbers’ or ‘the work done by a carpenter in joining two pieces of wood,’ and can refer to carpentry in general. It has a specialized use in a few Buddhist Sanskrit texts, where it means ‘vessel’ or ‘jar,’ and this image of ‘something that contains’ is evoked several times within the sutra, when Buddha calls the Sanghāta a ‘treasury of Dharma.’

Whether we take sanghāta as having the sense of joining or connecting that it has in standard Sanskrit, or the sense of holding or containing that it can have in Buddhist Sanskrit, the question remains as to just what is connected or held. One possible interpretation is that what is connected are sentient beings, and they are joined or connected by the Sanghāta to enlightenment. This suggestion—that what the Sanghāta joins is sentient beings to enlightenment—was offered by Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche during an oral transmission of the text in 2003. In this, we find an idea that we readers and reciters are the material that the Sanghāta is working on, as it shapes us, and connects us to our enlightenment in such a way that we will never turn back. This, indeed, is what Sarvashura initially requests the Buddha to give: a teaching that can ensure that the young ones are never disconnected from their path to enlightenment." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanghata_Sutra

Source: History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 BCE to 250 CE, Unesco, p.399.

Contributors: A. H. Dani, UNESCO Staff, M. S. Asimov, B. A. Litvinsky, Guang-da Zhang, R. Shabani Samghabadi, C. E. Bosworth, Unesco, 01-Jan-1994 - 574 pages. Volume II presents an account of various population movements and cultural exchanges in Central Asia between 700 B.C. and 250 A.D. Important nomadic tribal cultures such as the Kushans emerged during this period. Contacts between the Mediterranean and the Indus Valley were reinforced by the campaigns of Alexander the Great and, under his successors, the progressive syncretism between Zoroastrianism, Greek religion and Buddhism gave rise to a new civilization instituted by the Parthians, known for its artistic creations. Under Kushan rule, Central Asia became the crossroads of a prosperous trade between the Mediterranean and China along the Silk Route.

Yuezhi were Tocharian-speakers. Christopher Beckwith's narrative on Central Eurasian history begins with the chariot warriors and the Proto-Indo-Europeans in the late 3rd millennium BCE. Christopher Beckwith argues that the character 月, usually read as Old Chinese *ŋʷjat > Mod. yuè, could have been pronounced in an archaic northwestern dialect as *tokwar or *togwar, a form that resembles the Bactrian name Toχοαρ (Toχwar ~ Tuχwar) and the medieval form Toχar ~ Toχâr.(Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press, page 5, footnote #16, as well as pages 380–383 in appendix B.) Christopher Beckwith "equates the Tokharians with the Yuezhi, and the Wusun with the Asvins, as if these are established facts, and refers to his arguments in appendix B. But these identifications remain controversial, rather than established, for most scholars." As succinctly sumamrised by Doug Hitch, Christopher Beckwith proposes three migratory waves of languages from Urheimat (the PIE homeland): wave A with one set of stop consonants (Tocharian, Anatolian), wave B with three (Germanic, Italic, Greek, Indic, Armenian), and wave C with two (Celtic, Slavic, Baltic, Albanian, Iranian)(p.365).(Hitch, Doug (2010). "Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present" in: Journal of the American Oriental Society 130 (4): 654–658.)

http://www.ynlc.ca/ynlc/staff/hitch/review_of_Beckwith.pdf (Embedded) https://www.scribd.com/doc/269518451/Review-of-Christopher-Beckwith-s-Empires-of-the-Silk-Road-A-history-of-central-Eurasdia-from-th-Bronze-Age-to-the-Present-JAOS-130-4-2010-pp-65

For the pronunciation of Mod. yuè, as *togwar (cognate túṣāra) see: Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 806.

Thus, yuè-zhi were indeed Tushara of Vedic texts,

túṣāra m. sg. and pl. ʻ frost, snow, mist, dew, thin rain ʼ MBh., adj. ʻ cold ʼ Kālid.

Pk. tusāra -- n. ʻ hoarfrost, snow ʼ; Ku. tusyāro, tos ʻ frost ʼ (y?); N. tusāro ʻ snow, hoarfrost, dew ʼ; B. tusār ʻ cold, dew, drizzle ʼ; H. tusār ʻ cold ʼ, m. ʻ cold, frost, snow, ice, hail, dew, mist, thin rain, blight, crop ripening in cold season ʼ, tusārā, °rū ʻ cold, frosty ʼ; M. tusār, °rā m. ʻ drizzle ʼ; Si. tusara ʻ dew, mist ʼ, adj. ʻ cold ʼ. -- K. tṳ̄run ʻ to freeze ʼ < *tuhār -- ?(CDIAL 5894). It is suggested that the Tókharoi derived their self-designation from the gloss: túṣāra, 'frost, snow' considering the snow-clad Himalayan ranges of Xinjiang they migrated to and settled in.

Pk. tusāra -- n. ʻ hoarfrost, snow ʼ; Ku. tusyāro, tos ʻ frost ʼ (y?); N. tusāro ʻ snow, hoarfrost, dew ʼ; B. tusār ʻ cold, dew, drizzle ʼ; H. tusār ʻ cold ʼ, m. ʻ cold, frost, snow, ice, hail, dew, mist, thin rain, blight, crop ripening in cold season ʼ, tusārā, °rū ʻ cold, frosty ʼ; M. tusār, °rā m. ʻ drizzle ʼ; Si. tusara ʻ dew, mist ʼ, adj. ʻ cold ʼ. -- K. tṳ̄run ʻ to freeze ʼ < *tuhār -- ?(CDIAL 5894). It is suggested that the Tókharoi derived their self-designation from the gloss: túṣāra, 'frost, snow' considering the snow-clad Himalayan ranges of Xinjiang they migrated to and settled in.

They were "...Tusharas, also known as the Tukharas or Tócharoi, were a tribe of ancient India, with a kingdom located in the north west of India, according to the epic Mahabharata. An account in Mbh 1:85 depicts the Tusharas as Mlechchas and the descendants of Anu, one of the cursed sons of king Yayati. Yayati's eldest son Yadu, gave rise to the Yadavas and youngest son Puru to the Pauravas that includes the Kurus and Panchalas. Only the fifth son of Puru's line was considered to be the successors of Yayati's throne, as he cursed the other four sons and denied them kingship. Pauravas inherited the Yayati's original empire and stayed in the Gangetic plainwho later created the Kuru and Panchala Kingdoms. They were followers of the Vedic culture. The Yadavas made central and western India their stronghold. The descendants of Anu, known as the Anavas, are said to have migrated to Iran."

Puranic traditions (Bhagavata Purana) say that Budha, the patriarchic figure the Yadu, Turvasa, Druhyu, Anu and Puru clans had come from Central Asia to Bharatkhand to perform penitential rites and he espoused Ella, the daughter of Manu, by whom was born Pururavas. Pururavas had six sons, one of whom is said to be Ayu. This Ayu or Ay is said to be the patriarch figure of the Tartars of Central Asia as well as of the first race of the kings of China. (James Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, p 172.)

Pururavas and Urvasi had two sons, Ayu and Amavasu.Referring to these sons, Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra 18.44:397.9 sqq records:

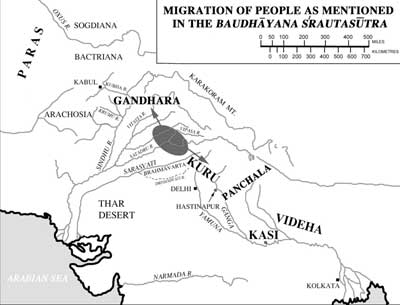

Ayu migrated eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru-Pancalas and the Kasi-Videhas. This is the Ayava (migration). Amavasu migrated westwards. His (people) are the Ghandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasu (migration).

Read with the Bhagavata Purana narrative, it is hypothesised that Ayu's people migrated to Xinjiang region and were referred to as Visha ("the tribes") or Vèsh in modern Pashto meaning "divisions" or Vijaya in Tibetan or Yuezhi in Chinese (identified with Tókharoi or Tushara). These were the people who migrated back to Gandhara and North-west India as Kushanas -- as shown in the Yuezi migration map from Tocharian-speaking region. It is notable that Tocharian records the Rigvedic word ams'u (a synonym of Soma) in a phonetic variant ancu'iron' (cf. Georges Pinault).Rigveda also records that Soma was purchased from traders from Mujavant mountain (which could be Mustagh Ata of Tocharian-seaking region).

Many theories have been propounded to identify the origin of Yuezhi people: The Rishikas are said to be same as the Yuezhis (Dr V. S. Aggarwala). The Kushanas or Kanishkas are also the same people (Dr J. C. Vidyalankara). Prof Stein says that the Tukharas were a branch of the Yue-chi or Yuezhi. Tusharas/Tukharas (Tokharois/Tokarais) and the Yuezhi are stated to be same people (Dr P.C. Bagchi).

Stein's contention that Tukharas (Tushara) were a branch of Yuezhi is consistent with Ayu peoples' migration to Xinjiang as Tartars, the first race of the kings of China. This is corroborated by the statement in Vayu Purana and Matsya Purana, that river Chakshu (Oxus) flowed through the countries of Tusharas (Rishikas?), Lampakas, Pahlavas, Paradas and Shakas etc.

These Tushara mleccha (Meluhha) were the people of Sarasvati_Sindhu Civilization who created the Indus Script Corpora.

The Chinese kept referring to the Kushans as Da Yuezhi throughout the centuries. In the Sanguozhi (三國志, chap. 3), it is recorded that in 229 CE, "The king of the Da Yuezhi, Bodiao 波調 (Vasudeva I), sent his envoy to present tribute, and His Majesty (EmperorCao Rui) granted him the title of King of the Da Yuezhi Intimate with the Wei (魏) (Ch: 親魏大月氏王, Qīn Wèi Dà Yuèzhī Wáng)."

...

In a sweeping analysis of the physical types and cultures of Central Asia that he visited in 126 BCE, Zhang Qian reports that "although the states from Dayuan west to Anxi (Parthia), speak rather different languages, their customs are generally similar and their languages mutually intelligible. The men have deep-set eyes and profuse beards and whiskers. They are skilful at commerce and will haggle over a fraction of a cent. Women are held in great respect, and the men make decisions on the advice of their women."(Shiji123)(Watson 1993, p. 245. Watson, Burton (1993), Records of the Grand Historian of China: Han Dynasty II (revised ed.)Translated from the Shiji of Sima Qian., p. 245)

"The Great Yuezhi [Kushans] is located about seven thousand li (about 3000 km) north of India. Their land is at a high altitude; the climate is dry; the region is remote. The king of the state calls himself "son of heaven". There are so many riding horses in that country that the number often reaches several hundred thousand. City layouts and palaces are quite similar to those of Daqin (the Roman empire). The skin of the people there is reddish white. People are skilful at horse archery. Local products, rarities, treasures, clothing, and upholstery are very good, and even India cannot compare with it." [Benjamin, Craig (October 2003). "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia". Transoxiana Webfestschrift (Transoxiana) 1 (Ēran ud Anērān).] Note: Craig Benjamin's article "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia"is embedded for ready reference.

These textual references indicating indicate that Yuezhi were traders, that they dealt with handicrafts and 'rarities, treasures', which was the hall-mark of Meluhha who have created metalwork catalogues as Indus Script Corpora with about 7000 inscriptions. Yuezhi were the Meluhha (mleccha). They were the vessa, vēsa, Vaiśya 'traders' (cognate Yuezhi). They could also have included the ivory-carvers of Begram who moved to Kankali-Tila, Mathura, Bharhut, Sanchi to create the architectural marvels of Stupa and Torana with Indus Script hierolyphs venerating dharma-dhamma.

Yuezhi or Rouzhi (Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: Yuèzhī, Wade–Giles Yüeh-chih) were an ancient Indo-European people. (Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88.). These were Meluhha speakers who had settled in the grasslands of Tarim Basin area which is today Xinjiang and western Gansu, in China. Yuezhi or Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι) or Tushara, migrated to Bactria and founded the Kushan Empire, which 'stretched from Turfan in the Tarim basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China."https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuezhi

In the Indian tradition, the Yuezhi can be called the chandra-vams'i since the name Yuezi in Chinese is formed with yuè (月) "moon" and shì (氏) "clan".

The Yuezhi were organized into five major tribes, each led by a yabgu, or tribal chief, and known to the Chinese as Xiūmì (休密) in Western Wakhān and Zibak, Guishuang (貴霜) in Badakhshan and the adjoining territories north of the Oxus, Shuangmi (雙靡) in the region of Shughnan, Xidun (肸頓) in the region of Balkh, and Dūmì (都密) in the region of Termez.(Hill, John E. (2003). The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation,pp. 29, 318–350).

It is notable that ancient Indian tradition also divided the community into five groups, panchal, five artisans, each guild led by a chief.There is a gloss in Sumerian and Gujarati (Indian sprachbund) denoting a pilgrim's companion: sanga 'priest'(Sumerian/Akkadian); sanghvi (Gujarati).

பஞ்சகம்மாளர் pañca-kammāḷar , n. < pañcantaṭṭāṉ, kaṉṉāṉ, ciṟpaṉ, taccaṉ, kollaṉ; தட்டான், கன்னான், சிற்பன், தச்சன் கொல்லன் என்ற ஐவகைப் பட்ட கம்மாளர். (சங். அக.) அஞ்சுபஞ்சலத்தார் añcu-pañcalattār , n. < அஞ்சு + பஞ்சாளத்தார். Pañca-kammāḷar, the five artisan classes; பஞ்சகம்மாளர். (I. M. P. Cg. 371.) pañcālá m. ʻ name of a tribe in North India ʼ ŚBr.

Pk. paṁcāla -- m. ʻ id. ʼ; K. panzāl m. ʻ the Pīr Panjāl range south of the valley of Kashmir ʼ.(CDIAL 7680) pāˊñcāla ʻ of the Pañcālas ʼ MBh. [

The migrations of the Yuezhi through Central Asia, from around 176 BCE to 30 CE

VIŚ ʻ enter, settle in ʼ:vēśá1 m. ʻ inhabitant (of a víś -- ), neighbour ʼ RV. [víś -- f. ʻ tribe, habitation ʼ RV. -- √viś ] Kho. Kal.rumb. gram -- bešu ʻ neighbour ʼ (< *vēśaka -- BelvalkarVol 90).(CDIAL 12124) vḗśa2 m. ʻ habitation ʼ VS. (= víś -- : VS. vḗśān dhāraya ~ RV. viśāˊṁ dhártr̥ -- ), ʻ house ʼ Daś. -- See vēśa -- 3 . [√viś ](CDIAL 12125) vēśíya metr. for vēśyà -- m. ʻ inhabitant ʼ RV. [vḗśa -- 2 ] Kt. vušī ʻ neighbour ʼ (Rep1 57 < vēśin -- ).(CDIAL 12127) vaíśya m. ʻ peasant as member of the third caste ʼ RV. adj. ʻ belonging to such ʼ MBh. (n. ʻ vassalage ʼ TS.). [vḗśa -- 1 or vēśyà --] Pa. vessa -- m., °sī -- , °sikā -- f. ʻ member of the third caste ʼ, Pk. vessa -- , vēsa -- m., vēsī -- f.; Si. vessā, st. ves<-> ʻ merchant ʼ; -- A. behā ʻ trade ʼ. vaiśyavr̥tti -- Add. 14810.(CDIAL 12150). Vessa [cp. Vedic vaiśya, a dial. (local) word] a Vaiśya, i. e. a member of the third social (i. e. lower) grade (see vaṇṇa 6), a man of the people D iii. 81, 95 (origin); Si. 102, 166; iv. 219; v. 51; A i. 162; ii. 194; iii. 214, 242; Vbh 394; DA i. 254 (origin). -- f. vesī (q. v.); vessī (as a member of that caste) D i. 193; A iii. 226, 229.Vessikā (f.) [fr. vessa] a Vaiśya woman Sn 314.(Pali)

Vaṇṇa [cp. Vedic varṇa, of vṛ: see vuṇāti. Customary definition as "vaṇṇane" at Dhtp 572] appearance etc. (lit. "cover, coating"). There is a considerable fluctuation of meaning, especially between meanings 2, 3, 4. One may group as follows. -- 1. colour Sn 447 (meda˚); Sv. 216 (chavi˚ of the skin); A iii. 324 (sankha˚); Th 1, 13 (nīl'abbha˚); Vv 4510 (danta˚=ivory white); Pv iv. 39 ; DhA ii. 3 (aruṇa˚); SnA 319 (chavi˚); VvA 2 (vicitta˚); PvA 215. Six colours are usually enumd as vaṇṇā, viz.nīla pīta lohitaka odāta mañjeṭṭha pabhassara Ps i. 126; cp. the 6 colours under rūpa at Dhs 617 (where kāḷaka for pabbassara); J i. 12 (chabbaṇṇa -- buddha -- rasmiyo). Groups of five see under pañca 3 (cp. J i. 222). -- dubbaṇṇa of bad colour, ugly S i. 94; A v. 61; Ud 76; Sn 426; It 99; Pug 33; VvA 9; PvA 32, 68. Opp.suvaṇṇa of beautiful colour, lovely A v. 61; It 99. Also as term for "silver." -- As t. t. in descriptions or analyses (perhaps better in meaning "appearance") in abl.vaṇṇato by colour, with saṇṭhānato and others: Vism 184 ("kāḷa vā odāta vā manguracchavi vā"), 243=VbhA 225; Nett 27. -- 2. appearance S i. 115 (kassaka -- vaṇṇaŋ abhinimminitvā); J i. 84 (id. with māṇavaka˚); Pv ii. 110 (=chavi -- vaṇṇa PvA 71); iii. 32 (kanakassa sannibha); VvA 16; cp. ˚dhātu. -- 3. lustre, splendour (cp. next meaning) D iii. 143 (suvaṇṇa˚, or=1); Pv ii. 962 (na koci devo vaṇṇena sambuddhaŋ atirocati); iii. 91 (suriya˚); Vv 291 (=sarīr' obhāsa VvA 122); PvA 10 (suvaṇṇa˚), 44. -- 4. beauty (cp. vaṇṇavant) D ii. 220 (abhikkanta˚); M i. 142 (id.); D iii. 68 (āyu+); Pv ii. 910 (=rūpa -- sampatti PvA 117). Sometimes combd with other ideals, as (in set of 5): āyu, sukha, yasa, sagga A iii. 47; or āyu, yasa, sukha, ādhipacca J iv. 275, or (4): āyu, sukha, bala A iii. 63. -- 5. expression, look, specified as mukha˚, e. g. S iii. 2, 235; iv. 275 sq.; A v. 342; Pv iii. 91 ; PvA 122. <-> 6. colour of skin, appearance of body, complexion M ii. 32 (parama), 84 (seṭṭha); A iii. 33 (dibba); iv. 396 (id.); Sn 610 (doubtful, more likely because of its combn with sara to below 8!), 686 (anoma˚); Vism 422 (evaŋ˚=odato vā sāmo vā). Cp.˚pokkharatā. <-> In special sense applied as distinguishing mark of race or species, thus also constituting a mark of class (caste) distinction & translatable as "(social) grade, rank, caste" (see on term Dial. i. 27, 99 sq.; cp. Vedic ārya varṇa and dāsa varṇa RV ii. 12, 9; iii. 34, 9: see Zimmer, Altind. Leben 113 and in greater detail Macdonell & Keith, Vedic Index ii. 247 sq.). The customary enumn is of 4 such grades, viz. khattiyā brāhmaṇā vessā suddā Vin ii. 239; A iv. 202; M ii. 128, but cp. Dial. i. 99 sq. -- See also Vin iv. 243 (here applied as general term of "grade" to the alms -- bowls: tayo pattassa vaṇṇā, viz. ukkaṭṭha, majjhima, omaka; cp. below 7); D i. 13, 91; J vi. 334; Miln 225 (khattiya˚, brāhmaṇa˚). -- 7. kind, sort Miln 128 (nānā˚), cp. Vin iv. 243, as mentioned under 6. -- 8. timbre (i. e. appearance) of voice, contrasted to sara intonation, accent; may occasionally be taken as "vowel." See A i. 229 (+sara); iv. 307 (id.); Sn 610 (id., but may mean "colour of skin": see 6), 1132 (giraŋ vaṇṇ' upasaŋhitaŋ, better than meaning "comment"); Miln 340 (+sara). <-> 9. constitution, likeness, property; adj. ( -- ˚) "like": aggi˚ like fire Pviii. 66 (=aggi -- sadisa PvA 203). -- 10. ("good impression") praise DhA i. 115 (magga˚); usually combd and contrasted with avaṇṇa blame, e. g. D i. 1, 117, 174; A i. 89; ii. 3; iii. 264; iv. 179, 345; DA i. 37. -- 11. reason ("outward appearance") S i. 206 (=kāraṇa K.S. i. 320); Vv 846 (=kāraṇa VvA 336); Pv iv. 16 (id. PvA 220); iv. 148 .-- āroha (large) extent of beauty Sn 420. -- kasiṇa the colour circle in the practice of meditation VbhA 251. -- kāraka (avaṇṇe) one who makes something (unsightly) appear beautiful J v. 270. -- da giving colour, i. e. beauty Sn 297. -- dada giving beauty A ii. 64. -- dasaka the ten (years) of complexion or beauty (the 3rd decade in the life of man) Vism 619; J iv. 497. -- dāsī "slave of beauty," courtezan, prostitute J i. 156 sq., 385; ii. 367, 380; iii. 463; vi. 300; DhA i. 395; iv. 88. -- dhātu composition or condition of appearance, specific form, material form, natural beauty S i. 131; Pv i. 31 ; PvA 137 (=chavivaṇṇa); DhsA 15. -- patha see vaṇṇu˚.-- pokkharatā beauty of complexion D i. 114, 115; A i. 38; ii. 203; Pug 66; VbhA 486 (defd ); DhA iii. 389; PvA 46. -- bhū place of praise J i. 84 (for ˚bhūmi: see bhū2 ). -- bhūta being of a (natural) species PvA 97. -- vādin saying praise, praising D i. 179, 206; A ii. 27; V.164 sq.; Vin ii. 197. -- sampanna endowed with beauty A i. 244 sq., 288; ii. 250 sq.(Pali)

Vaṇṇa [cp. Vedic varṇa, of vṛ: see vuṇāti. Customary definition as "vaṇṇane" at Dhtp 572] appearance etc. (lit. "cover, coating"). There is a considerable fluctuation of meaning, especially between meanings 2, 3, 4. One may group as follows. -- 1. colour Sn 447 (meda˚); S

विश्[p= 732,2] (or बिश्) cl.1 P. बेशति , to go Dha1tup. xvii , 71 (= √ पिस् q.v.) to enter , enter in or settle down on , go into to enter (a house &c ) Hariv. ; f. (m. only L. ; nom. sg. व्/इट् ; loc. pl. विक्ष्/उ) a settlement , homestead , house , dwelling (विश्/अस् प्/अति " lord of the house " applied to अग्नि and इन्द्र) RV.(sg. and pl.) the people καÏá¾½ , á¼Î¾Î¿Ïήν , (in the sense of those who settle on the soil ; sg. also " a man of the third caste " , a वैश्य ; विशाम् with पतिः or नाथः or ईश्वरः &c , " lord of the people " , a king , sovereign) S3Br. &c(pl.) property , wealth BhP.mf. a man in general , person L.

viṣaya m. ʻ scope ʼ ŚāṅkhŚr., ʻ sphere, region ʼ MBh. [√viṣ ] Pa. Pk. visaya -- m. ʻ sphere, locality ʼ; -- Si. visā ʻ district ʼ (EGS 166) ← Pa.?(CDIAL 11973) vḗṣa -- 1 m. ʻ work, activity ʼ VS. [√viṣ ]

विषय[p= 997,1] a country with more than 100 villages L.; m. (ifc. f(आ). ; prob. either fr √1. विष् , " to act " , or fr. वि + √ सि , " to extend " cf. Pa1n2. 8-3 , 70 Sch.) sphere (of influence or activity) , dominion , kingdom , territory , region , district , country , abode (pl. = lands , possessions) Mn. MBh. &c; special sphere or department , peculiar province or field of action , peculiar element , concern (ifc. = " concerned with , belonging to , intently engaged on " ; विषये , with gen. or ifc. = " in the sphere of , with regard or reference to " ; अत्र विषये , " with regard to this object ") MBh. Ka1v. &c; a symbolical N. of the number " five " VarBr2S.anything perceptible by the senses , any object of affection or concern or attention , any special worldly object or aim or matter or business , (pl.) sensual enjoyments , sensuality Kat2hUp. Mn. MBh. &c

कौश kauśaकौश a. (-शी f.) [कुश-अण्] 1 Silken; Bhāg.3.4.7.-2 Made of Kuśa grass.-शम् An epithet of Kānya- kubja.द्वीपः पम् [द्विर्गता द्वयोर्दिशोर्वा गता आपो यत्र; द्वि-अप्, अप ईप्] 1 An island. -2 A place of refuge, shelter, pro- tection. -3 A division of the terrestrial world; (the number of these divisions varies according to different authorities, being four, seven, nine or thirteen, all situated round the mountain Meru like the petals of a lotus flower, and each being separated from the other by a distinct ocean. [In N. 1.5 the Dvīpas are said to be eighteen; but seven appears to be the usual number :- जम्बु, प्लक्ष, शाल्मलि, कुश, क्रौञ्च, शाक and पुष्कर; cf. Bhāg.5.1.32; R.1.65; and पुरा सप्तदीपां जयति वसुधामप्रतिरथः Ś.7.33. The central one is जम्बुद्वीप in which is included भरतखण्ड or India.] कुश [p= 296,3] m. grass S3Br. S3a1n3khS3r. Ka1tyS3r. A1s3vGr2. the sacred grass used at certain religious ceremonies (Poa cynosuroides , a grass with long pointed stalks) Mn. Ya1jn5. MBh. &cf. a rope (made of कुश grass) used for connecting the yoke of a plough with the pole L. कुशी (= कुशा) a small pin (used as a mark in recitation and consisting of wood [ MaitrS. iv] or of metal [TBr. i S3Br. iii]) f. a ploughshare L. कुशा f. ( Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46) a small pin or piece of wood (used as a mark in recitation) La1t2y. ii , 6 , 1 and 4 (Monier-Williams)

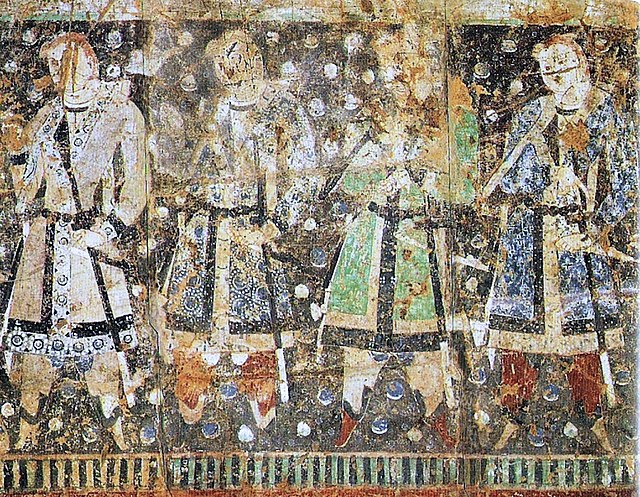

![QizilDonors.jpg]()

Wall painting of "Tocharian Princes" from Cave of the Sixteen Sword-Bearers (no. 8), Qizil, Tarim Basin, Xinjiang, China. Carbon 14 date: 432–538 CE. Original in Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin.

Wall painting of "Tocharian Princes" from Cave of the Sixteen Sword-Bearers (no. 8), Qizil, Tarim Basin, Xinjiang, China. Carbon 14 date: 432–538 CE. Original in Museum für Indische Kunst, Berlin.

Possible Yuezhi king and attendants, Gandhara stone palette, 1st century CE

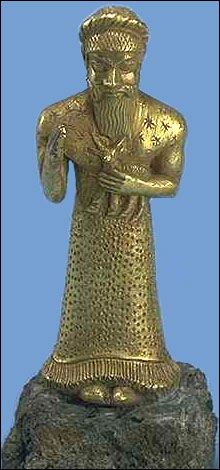

Shu-ilishu cylinder seal of eme-bal, interpreter. Akkadian. Cylinder seal Impression. Inscription records that it belongs to ‘S’u-ilis’u, Meluhha interpreter’, i.e., translator of the Meluhhan language (EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI) The Meluhhan being introduced carries an goat on his arm. Musee du Louvre. Ao 22 310, Collection De Clercq 3rd millennium BCE. The Meluhhan is accompanied by a lady carrying a kamaṇḍalu. The goat on the trader's hand is a phonetic determinant -- that he is Meluhha. This is decrypted based on the word for the goat: mlekh 'goat' (Brahui); mr..eka 'goat' (Telugu) Rebus: mleccha'copper' (Samskritam); milakkhu 'copper' (Pali) Thus the sea-faring merchant carrying the goat is a copper (and tin) trader from Meluhha. The jar carried by the accompanying person is a liquid measure:ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. A hieroglyph used to denote ranku may be seen on the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa. See Annex on Tarim Basin mummies and Meluhha speakers.

Elamite, holding a goat (Gold, silver cire perduestatues) ca. 1400 BCE. mlekh, mr..eka 'goat' (Brahui.Telugu) Rebus: milakkhu 'Meluhha, mleccha''copper' (Pali)

Head of a warrior. Khalchayan. Painted clay. (Photo: © Vladimir Terebenin.)

Meluhha (Bhāratam Janam) trade routes 1. From Hanoi to West of Sindhu to Haifa (assur meluhha)and 2. Eurasia (túṣāra meluhha)

[quote]From the sixth century BCE, land and river routes criss-crossed the subcontinent and extended in various directions – overland into Central Asia and beyond, and overseas, from ports that dotted the coastline – extending across the Arabian Sea to East and North Africa and West Asia, and through the Bay of Bengal to Southeast Asia and China. Rulers often attempted to control these routes, possibly by offering protection for a price.

Those who traversed these routes included peddlers who probably travelled on foot and merchants who travelled with caravans of bullock carts and pack-animals. Also, there were seafarers, whose ventures were risky but highly profitable. Successful merchants, designated as masattuvan

in Tamil and setthisand satthavahasin Prakrit, could become enormously rich. A wide range of goods were carried from one place to another – salt,

grain, cloth, metal ores and finished products, stone, timber, medicinal plants, to name a few. Spices, especially pepper, were in high demand in

the Roman Empire, as were textiles and medicinal plants, and these were all transported across the Arabian Sea to the Mediterranean.

Items traded

Recent archaeological finds suggest that copper was also probably brought from Oman, on the southeastern tip of the Arabian peninsula. Chemical

analyses have shown that both the Omani copper and Harappan artefacts have traces of nickel, suggesting a common origin.

There are other traces of contact as well. A distinctive type of vessel, a large Harappan jar coated with a thick layer of black clay has been found at Omani sites. Such thick coatings prevent the percolation of liquids. We do not know what was carried in these vessels, but it is possible that the Harappans exchanged the contents of these vessels for Omani copper. Mesopotamian texts datable to the third millennium BCE refer to copper coming from a region called Magan, perhaps a name for Oman, and interestingly enough copper found at Mesopotamian sites also contains traces of nickel.

Other archaeological finds suggestive of long distance contacts include Harappan seals, weights, dice and beads. In this context, it is worth noting that Mesopotamian texts mention contact with regions named Dilmun (probably the island of Bahrain), Magan and Meluhha, possibly the Harappan region. They mention the products from Meluhha: carnelian, lapis lazuli, copper, gold, and varieties of wood.

A Mesopotamian myth says of Meluhha: “May your bird be the haja-bird, may its call be heard in the royal palace.” Some archaeologists think the

haja-bird was the peacock. Did it get this name from its call? It is likely that

communication with Oman, Bahrain or Mesopotamia was by sea. Mesopotamian texts refer to Meluhha as a land of seafarers. Besides,we find depictions of ships and boats on seals. [unquote]

Annex: Tarim Basin mummies and Meluhha speakers

Some Tarim mummies on trade caravans spoke Mleccha (Meluhha) before they were mummies

This hypothesis needs to be tested by archaeometallurgical and historical linguistic studies from an extended area from Ancient Far East to Ancient Near East. This is also an imperative in the context of a new start for Vedic and IE studies. Evidence of contact between Vedic and Tocharian has already been attested in the cognate expressions: ams'u (Vedic), ancu (Tocharian). The circular stones in funerary practices unite Tocharian and Dholavira. By the 6th century CE, the Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira also locates the Tusharas with Barukachcha (Bhroach) and Barbaricum (on the IndusDelta) near the sea in western India: bharukaccha.samudra.romaka.tushrah.. :(BrhatsamhitaXVI.6). If contacts with area lived in by speakers of Kafiri (Nuristani) was a transit point, Tushara could also have arrived to settle in Barukachcha from this detour from Kyrgystan (Muztagh Ata), taking a caravan route south of the Oxus (Amu Darya) river. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tushara_Kingdom

What language did the people of Sarasvati-Sindhu doab river basins (with about 2,600 archaeological sites) speak? Given the evidence of Buddhist Hybrid Samskritam (BHS) in the Tarim Basin documents and the links between Rigvedic people and Tushara (Tocharian) in trade transactions of Soma (synonyms, metaphors: ams'u, ancu), a proto-BHS, or Proto-Indo-Aryan, or Early Indo-European, Mleccha (Meluhha) is suggested as the language of the metalworkers of the Bronze Age. Mleccha, 'copper' (Samskritam) provides the profession of Mleccha-speakers, 'metal workers', also referred to by cognate expressions: Milakkha (Pali), Meluhha (Akkadian on a Shu-ilishu cylinder seal). A reference to the metalworkers is contained in the expression used in Rigveda to denote the people in general by Rigveda Rishi Visvamitra: Bharatam Janam, 'lit. metalworker people'. Chandas, 'prosody' represented the liturgical version of an Indo-European language and Mleccha/Meluhha 'parole or speech' represented the administrative version of the language used predominantly by trader caravans (as attested by Tarim Mummies and the Tin Road from Asshur to Kanesh in Ancient Near East), by metalworkers, in general and by specialist cire perdue metalcasters,dhokra kamar, in particular. The expression, kamar is an Indo-European gloss: karmāˊra m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ RV. [EWA i 176 < stem *karmar -- ~ karman -- , but perh. with ODBL 668 ← Drav. cf. Tam. karumā ʻ smith, smelter ʼ whence meaning ʻ smith ʼ was transferred also to

Md. kan̆buru ʻ blacksmith ʼ.(CDIAL 2898). kamar 'artisan, smith, smelter' (Santali) karum (Akkadian: kārum "quay, port, commercial district", plural kārū, from Sumerian kar "fortification (of a harbor), break-water" is also perhaps an expression related to karumā 'smith, smelter' or khārun, 'the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting' (Kashmiri, see below) of this Indian sprachbund.

The roots of the expression are found in Kashmiri where a number of compounds are attested and hence provide the trade route across Karakoram and Pamir, from Muztagh Ata through Kashmir to Sarasvati-Sindhu river basins: khār 1

"Early references to karū come from the Ebla tablets; in particular, a vizier known as Ebrium concluded the earliest treaty fully known to archaeology, known variously as the "Treaty between Ebla and Aššur" or the "Treaty with Abarsal" (scholars have disputed whether the text refers to Aššur or to Abarsal, an unknown location). In either case, the other city contracted to establish karū in Eblaite territory (Syria), among other things... By 1960 BC, Assyrian merchants had established the karū,[5] small colonial settlements next to Anatolian cities which paid taxes to the rulers of the cities.[6] There were also smaller trade stations which were called mabartū (singular mabartum). The number of karū and mabartū was probably around twenty. Among them were Kültepe (Kanesh in antiquity) in modern Kayseri Province; Alişar Hüyük (Ankuva (?) in antiquity) in modern Yozgat Province; and Boğazköy (Hattusa in antiquity) in modern Çorum Province. (However, Alişar Hüyük was probably a mabartum.)(a metal in trade transactions)... amutum, was even more valuable than gold. Amutum is thought to be the newly discovered iron and was forty times more valuable than silver. The most important Anatolian export was copper, and the Assyrian merchants sold tin and clothing to Anatolia." (Ekrem Akurgal: Anadolu Kültür Tarihi, Tubitak, Ankara, 2000, pp. 40-41). It is possible that amutum also relates to Vedic-Tocharian ams'u-ancu.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karum_(trade_post)

Letter from Assyria to karum Kanesh concerning the trade in precious metals. 1850–1700 BC. Walters Museum (click on image for more info).

Letter from Assyria to karum Kanesh concerning the trade in precious metals. 1850–1700 BC. Walters Museum (click on image for more info).Tracing the Tarim mummies to the traditions associated with the veneration of the departed aatman, we find a remarkable parallel in Dholavira and Harappa of stone circles associated with death ceremonies. It is not unlikely that some of the mummies before they were mummies spoke Mleccha (Meluhha) language, not far from Kafiri (Nuristani) which was attested as a possible candidate by Frits Staal.(http://bharatkalyan97.

According to Louis Renou, the immense Rigvedic collection is present in nuce in the themes related toSoma. Rigveda mentions amśu as a synonym of soma. The possibility of a link with Indus writing corpora which is essentially a catalog of stone-, mineral-, metalware, cannot be ruled out.

George Pinault has found a cognate word in Tocharian, ancu which means 'iron'. I have argued in my book, Indian alchemy, soma in the Veda, that Soma was an allegory, 'electrum' (gold-silver compound). See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/10/itihasa-and-eagle-narratives.html for Pinault's views on ancu, amśu concordance.

The link with the Tocharian word is intriguing because Soma was supposed to come from Mt. Mujavant. A cognate of Mujavant is Mustagh Ata of the Himalayan ranges in Kyrgystan.

Is it possible that the ancu of Tocharian from this mountain was indeed Soma?

The referemces to Anzu in ancient Mesopotamian tradition parallels the legends of śyena 'falcon' which is used in Vedic tradition of Soma yajña attested archaeologically in Uttarakhand with a śyenaciti, 'falcon-shaped' fire-altar.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/11/syena-orthography.html śyena, orthography, Sasanian iconography. Continued use of Indus Script hieroglyphs.

Comparing the allegory of soma and the legend of Anzu, the bird which stole the tablets of destiny, I posit a hypothesis that the tablets of destiny are paralleled by the Indus writing corpora which constitute a veritable catalog of stone-, mineral- and metal-ware in the bronze age evolving from the chalcolithic phase of what constituted an 'industrial' revolution of ancient times creating ingots of metal alloys and weapons and tools using metal alloys which transformed the relation of communities with nature and resulted in the life-activities of lapidaries transforming into miners, smiths and traders of metal artefacts.

I suggest that ayas of bronze age created a revolutionary transformation in the lives of people of these bronze age times.

Comparing the allegory of soma and the legend of Anzu, the bird which stole the tablets of destiny, I posit a hypothesis that the tablets of destiny are paralleled by the Indus writing corpora which constitute a veritable catalog of stone-, mineral- and metal-ware in the bronze age evolving from the chalcolithic phase of what constituted an 'industrial' revolution of ancient times creating ingots of metal alloys and weapons and tools using metal alloys which transformed the relation of communities with nature and resulted in the life-activities of lapidaries transforming into miners, smiths and traders of metal artefacts.

I suggest that ayas of bronze age created a revolutionary transformation in the lives of people of these bronze age times.

"The Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, which date from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE. Many centuries separate these mummies from the first attestation of the Tocharian languages in writing. A 2008 study by Jilin University that the Yuansha population has relatively close relationships with the modern populations of South Central Asia and Indus Valley, as well as with the ancient population of Chawuhu. (Mitochondrial DNA analysis of human remains from the Yuansha site in Xinjiang Science in China Series C: Life Sciences Volume 51, Number 3 / March, 2008). The scientists extracted enough material to suggest the Tarim Basin was continually inhabited from 2000 BCE to 300 BCE and preliminary results indicate the people, rather than having a single origin, originated from Europe, Mesopotamia, Indus Valley and other regions yet to be determined.(Amanda Huang https://archive.today/bK4h)."

http://bharatkalyan97.

"Buddhist missionaries possesed liturgical texts in what is known as Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, a language originating in northern India...Whether from India or greater Iran, all of these languages were carried into the Tarim basin by religious communities or merchants from outside the region during the 1st millennium CE. A second group of languags are associated with documents that were not exclusively religious, but also adminsitrative. This may indicate that the languages were spoken by considerable numbers of the local population. Buddhists in the region of Kroran (Chinese Loulan), for example, employed an Indic language, Prakrit, in administration. Tocharian was used both to translate Buddhist texts and as an administrative language, which suggests that it was spoken by a wider range of people than exclusively monks. Another major language was Khotanese Saka, the language spoken in the south of the Tarim Basin at th site of Khotan as well as at northern sites suh as Tumshuq and Murtuq and possibly Qashgar, the western gateway into the Tarim Basin...And unlike Tocharian, which became extinct, there were small pockets of Saka speakers who survived in the Pamir Mountains...two main languages in the Tarim Basin that might be associated with at least some of the Tarim mummies of the Bronze Age and Iron Age: Khotanese Saka (or any other remnant of the Scythians or the Eurasian steppe) and Tocharian...Saka belongs to the eastern branch of the Iranian languages, which was one of he most widespread of the Indo-European family of languages spoken in most of Europe, Iran, India, and other parts of Asia...The sub-branch to which Saka belongs also included Sogdian, Bactrian and Avestan. Most archaeologists believe that the Iranian languages appeared earliest in the steppelands and only later moved southward through the agricultural oases of Central Asia into the region of modern Iran. The Iranian language group is very closely related to Indo-Aryan, the branch of Indo-European that occupies the northern two-thirds of India; these language groups presumably shared a common origin in the steppe region during the Bronze Age, perhaps about 2500 BCE." (Mallory, 2010, JP, Bronze Age languages of the Tarim Basin, Expedition, Volume 52, Number 3

http://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/pdfs/52-3/mallory.pdf pp.45-47)

Mallory goes on t provide select glosses comparing Saka with Tocharian B:

duva - wi (two)

drai - trai (three)

tcahora - s'twer (four)

hauda - sukt (seven)

sata - kante (hundre)

pate - pAcer (father)

mAta - mAcer (mother)

brAte - procer (brother)

ass- - yakwe (horse)

gguhi - keu (cow)

bar- - par- (bear, carry)

puls- - park- (ask)

In the Tarim Basin, in addition to Tocharian, administrative texts in Prakrit have been discovered; this is an Indian language from the terroritory of Kroran; the Kroranian documents date to ca. 300 CE providing the earliest evidence of spoken Tocharian.

Mallory continues: "From a linguistic point of view, we need to explain how languages from two major Indo-European language groups managed to spread into the Tarim Basin, and evaluate as far as possible whether they were the language spoken by those Bronze Age individuals whose remains were mummified...We also know that the Saka were known to the ancient Greeks as Scythians, and were clearly a people of the northern steppes, famous as horse-riding nomads who periodically challenged the civilizations to their south. They are attested in historical and archaeological sources from about the 8th century BCE...The one language group that is most clearly anchored in the Tarim, Tocharian, lacks any obvious external source..." (ibid., pp.49-50).

The search is on to trace the movements from Andronovo or Afanasievo cultures, the way the search is on for the Urheimat of PIE. Based on what Nicholas Kazanas has pointed out and argued, the search for Urheimat for PIE may lie closer to the river basin where most of Rigveda was composed and chanted: Sarasvati River Basin. This river basin attests a spoken, administrative language: Mleccha (Meluhha) which may include many mispronunciations of reconstructed IE glosses and expressions and closely associated with the Prakrits which may also be termed Proto-Indo-Aryan. Tocharian speakers got isolated from the rest of the Indo-Europeans but had apparent trade contacts with the Rigvedic people for exchanges of Soma (ancu) from Mount Mujavant (Muztagh Ata) of the Tarim Basin as argued with the evidence of cognates (Soma syonym) ams'u~~ancu pointed out by Georges Pinault.

So, with Frits Staal, Mallory and Mair have to answer the question posed earlier, why Mleccha (Meluhha) could not be the candidate among the IE languages to explain Tocharian languages.

The concentric circles of timber posts found in Tarim Basin may also compare with concentric circles of stones found in Ukherda and Dholavira. See also polished stone pillars found in Dholavira and stone sivalinga found in Harappa.

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ancient graveyard, near Nakhtarna, Kutch: anthropomorphic menhirs

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery.

Ukherda burial ground, cemetery.

Barrow Cemetery in IndiaNear Nakhtarana in Kutch, Gujarat, there is a large cemetery and cremation ground called Ukherda by the locals. There are also ancient hero and Sati stones. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=26370

Circle of stones at Dholavira.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Remains of Circular hutments (?) joined in 8-shape with stone pillar fragments at the centre of each circle, close to the area where two polished stone pillars (sivalinga?) were found. Did these circular stone remnants, denote a smithy? In Kota language (Indian sprachbund, Mleccha-Meluhha) kole.l 'smithy, temple'.

Remains of Circular hutments (?) joined in 8-shape with stone pillar fragments at the centre of each circle, close to the area where two polished stone pillars (sivalinga?) were found. Did these circular stone remnants, denote a smithy? In Kota language (Indian sprachbund, Mleccha-Meluhha) kole.l 'smithy, temple'.

Three stone Siva Lingas found in Harappa. Plate X [c] Lingam in situ in Trench Ai (MS Vats, 1940, Excavations at Harappa, Vol. II, Calcutta): ‘In the adjoining Trench Ai, 5 ft. 6 in. below the surface, was found a stone lingam [Since then I have found two stone lingams of a larger size from Trenches III and IV in this mound. Both of them are smoothed all over]. It measures 11 in. high and 7 3/8 in. diameter at the base and is rough all over.’ (Vol. I, pp. 51-52)."

Using stone slabs in cremation samskara in Vedic tradition is attested from the days of Rigveda. "When the body is almost consumed by the fire the chief mourner carries an earthen pot (the one in which fire was brought) filled with water on his shoulders and walks thrice round the burning pyre. A man walks with him piercing with a stone called the ashma or life-stone a hole in the jar out of which water spouts round the burning corpse. He finally throws the trickling water pot backwards over the shoulders spilling the water over the ground. Then, he pours libations of water mixed with sesamum on the ashma to cool the spirit of the dead which has been heated by the fire. The ashma is carefully preserved for ten days. The mourners also pour such water on the ashma. When the body is completely consumed, the party returns. During the first ten days, all closely related persons belonging to the family observe mourning called sutak." http://akola.nic.in/gazetteers/maharashtra/people_rituals.html As'ma is the symbolic stone of the departed aatman which is used during the samskara performances lasting upto 13 days after the cremation. अश्म 1 [p = 114 , 1] ifc. for. 2 / अश्मन् , a stone Pa1n2. 5-4, 94th as'man *= 2 %{A} m. (once %{azma4n} S3Br. iii), a stone, rock RV. &c.; a precious stone RV. v, 47, 3 S3Br. vi; any instrument made of stone (as a hammer &c.) RV. &c.; thunderbolt RV. &c.; a cloud Naigh.; the firmament RV. v, 30, 8; 56, 4; vii, 88, 2 [cf. Zd. {asman}; Pers. {as2ma1n}; Lith. {akmu}; Slav. {kamy}].

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-ziggurat-and-related.html

![]()

The salty sands and freeze-drying climate of the Tarim Basin, where the mummies were found, are highly conducive to preservation. http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0111/feature2_1.html

![]()

http://atlantisonline.smfforfree2.com/index.php?topic=14315.0

![]()

A Tarim Mummy and a reconstruction.

http://dienekes.blogspot.in/2011/05/on-tocharian-origins.html

Using stone slabs in cremation samskara in Vedic tradition is attested from the days of Rigveda. "When the body is almost consumed by the fire the chief mourner carries an earthen pot (the one in which fire was brought) filled with water on his shoulders and walks thrice round the burning pyre. A man walks with him piercing with a stone called the ashma or life-stone a hole in the jar out of which water spouts round the burning corpse. He finally throws the trickling water pot backwards over the shoulders spilling the water over the ground. Then, he pours libations of water mixed with sesamum on the ashma to cool the spirit of the dead which has been heated by the fire. The ashma is carefully preserved for ten days. The mourners also pour such water on the ashma. When the body is completely consumed, the party returns. During the first ten days, all closely related persons belonging to the family observe mourning called sutak." http://akola.nic.in/gazetteers/maharashtra/people_rituals.html As'ma is the symbolic stone of the departed aatman which is used during the samskara performances lasting upto 13 days after the cremation. अश्म 1 [p = 114 , 1] ifc. for. 2 / अश्मन् , a stone Pa1n2. 5-4, 94th as'man *= 2 %{A} m. (once %{azma4n} S3Br. iii), a stone, rock RV. &c.; a precious stone RV. v, 47, 3 S3Br. vi; any instrument made of stone (as a hammer &c.) RV. &c.; thunderbolt RV. &c.; a cloud Naigh.; the firmament RV. v, 30, 8; 56, 4; vii, 88, 2 [cf. Zd. {asman}; Pers. {as2ma1n}; Lith. {akmu}; Slav. {kamy}].

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-ziggurat-and-related.html

The salty sands and freeze-drying climate of the Tarim Basin, where the mummies were found, are highly conducive to preservation. http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0111/feature2_1.html

http://atlantisonline.smfforfree2.com/index.php?topic=14315.0

A Tarim Mummy and a reconstruction.

http://dienekes.blogspot.in/2011/05/on-tocharian-origins.html

Ērān ud Anērān Webfestschrift Marshak 2003

The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia

Craig Benjamin

Introduction

Following the defeat of the formerly powerful Yuezhi confederation by the Xiongnu near Dunhuang in c.162 BCE, the Yuezhi dynasty and those tribes that remained loyal to it commenced a migration away from the Gansu that was destined to completely reshape the geopolitics of ancient Inner Asia. Both the Han Shu and Shi Ji provide evidence of their departure: "the Yuezhi had fled furious with the Xiongnu"1, the 'Yuezhi had fled and bore a constant grudge against the Xiongnu'2. The decision to migrate, despite still having a force of perhaps 100,000 armed archer warriors at their disposal is indicative of the severity of the defeat, and also of the steadily increasing power of the Xiongnu under Maodun and Jizhu during the preceding decades. The Yuezhi dynasty may in fact have considered such a move several times during the fourteen years between Maodun's initial raid against them in 176, and their ultimate defeat in 162.Indeed, the fact that the migration seems to have been conducted in an orderly fashion suggests something of a planned strategic relocation rather than a rout. The Yuezhi's original intention was to move some 2000 kilometres to the northwest and resettle in the valley of the Ili River, a region occupied by a group of Sakas (or Scythians). They had no intention, nor any idea, that this journey would only be the first stage of a migration that ultimately would take them half away across Central Asia, until thirty years later they would find themselves in secure occupation of the fertile river valleys north of the Amu Darya, and masters of the former Greek kingdom of Bactria.

Leaving the Gansu in 162 the Yuezhi headed northwest towards the Ili Valley, settling near Ysyk Kul in present-day Kazakhstan. Corroborative evidence for this new location is provided by the Greek geographer Ptolemy who mentions a group called the Tagouraioi (clearly a variation on Tocharian, the Indo-European language spoken by the core Yuezhi) dwelling near Ysyk Kul3. Russian archaeologist Yu Zadneprovsky has noted a substantial number of podboy sites in the region, which he has tentatively identified as Yuezhi on the basis of their similarity to other podboy tombs discovered at the Haladun site near Minqin in the Central Gansu, which he also argues are Yuezhi. The Ysyk Kul region is rich in nomadic burial sites and some 370 tombs had been noted by as early as 1960. Of these, 80% were in pits, and attributed to the autonomous Sakas, and 17% in podboys, tentatively attributable to the Yuezhi4.

The Chinese sources show that the Ili/Ysyk Kul region was already populated by the Sai people, an eastern concentration of Sakas or Scythians who probably spoke an Indo-Iranian language. Upon arriving at the Ili, the Yuezhi quickly displaced them: (The Yuezhi) 'attacked the king of the Sai (who) moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands'5. Most of the displaced Sakas subsequently undertook their own substantial migration, moving west and then south through the western Tarim Basin, crossing the so-called 'Suspended Crossing' (probably the Khunjerab Pass or similar, between present-day Xinjiang and northern Pakistan) before ultimately settling in Kashmir6.

The Yuezhi confederation occupied the former Sakan lands in the hope of permanently resettling there, and remained in residence for almost three decades. They no doubt felt they had successfully relocated, having escaped the Xiongnu menace and reestablished themselves in the fertile Ili Valley. They returned to their previous semi-nomadic, semi-sedentary lifeway and probably began to lose interest in Chinese/nomadic politics. But the Kunmo of the Wusun, the former neighbours of the Yuezhi in the Gansu, could not forget the ill treatment his people had suffered as a result of a Yuezhi attack upon them in 1737. Eventually he sought permission from his Xiongnu overlord (the new ShanyuJunchen, successor to Jizhu who had died in 158) to pursue the Yuezhi into the Ili and 'avenge his father's wrongs'8. In 132 BCE the Kunmo led a powerful force of mounted Wusun archers into the region which attacked and routed the no doubt surprised and dismayed Yuezhi, forcing them to once again uproot and resume their long march to the west.

The sources indicate that within a short space of time the Yuezhi passed through a region called Dayuan 'The Yuezhi thereupon went far away, passing Dayuan and proceeding west'9 and then through a land to the southwest called Kangju. Although the exact route remains a matter of some conjecture, the evidence of both the Chinese annals, and of Russian and Central Asian archaeology, leaves little doubt that the Dayuan through which the migrating horde passed can only be identified with the Ferghana Valley10. The Yuezhi apparently met with little resistance from the urbanised Dayuans/Ferghanese, and after perhaps spending some months (the winter of 132/1?) in southwestern Ferghana, they passed on unmolested. Zadneprovsky has also noted several single podboy burials that have been unearthed in the southwestern, northern and eastern parts of the Ferghana Valley, most concentrated in the Lyailyaka-Isfara-Sokha interfluve in southern Kyrgyzstan where over 300 podboy burials have been located. Although originally attributed to a separate culture by Baruzdin in 1960, Zadneprovsky argues for their re-attribution to the migrating Yuezhi, on the basis of their similarity to podboy sites also tentatively attributable to the Yuezhi in both the Gansu and Ysyk Kul region11.

Perhaps in the spring of 131 BCE then, the Yuezhi most probably moved from Ferghana into the 'state' of Kangju, probably the Zeravshan Valley in the heart of Sogdia. Some four or five years later they were followed through the region by Han envoy Zhang Qian, who was led there by guides and interpreters provided for him by the king of Dayuan. It is references to Kangju in the Han Shu and Shi Ji (and by Ptolemy in his Geographica), as well as the discoveries of Soviet and Russian archaeologists, that has provided evidence identifying Kangju with Sogdia, and thus of the role of Sogdia in both the migration of the Yuezhi and the mission of Zhang Qian. The intention of this paper is to consider the origins of the relationship that developed between the Kangju and Yuezhi dynasties, a relationship that subsequently evolved to provide vital political and military stability in the region throughout the Kushan Era. The initial task is to consider evidence that allows for the conclusive identification of Kangju as Sogdia.

References to Kangju and the Yuezhi in the Han Annals

Kangju Sogdia: Location and Lifeway

Location'The seat of the king's government in winter is in Leyuenidi to the town of Beitian. It is distant by 12,300 li from Xian. One reaches (Le)yuenidi after a journey of seven days on horseback, and it is a distance of 9,104 li within the realm to the king's summer residence. To the east it is a distance of 5,500 li to the Seat of the Protector General'12.

'It is said: Some 2000 li to the northwest from Kangju is the state of Yancai. The trained bowmen number 100,000. It has the same way of life as Kangju. It is situated on the Great Marsh, which has no further shore and which is presumably the Northern Sea'13.

'Kangju is situated some 2,000 li northwest of Dayuan. The country is small and borders Dayuan. It acknowledges nominal sovereignty to the Yuezhi people in the south and the Xiongnu in the east'14

'(Wusun) adjoins Kangju in the northwest'15

'(The State of Wusun) and 5000 li to the west, to land within the realm of Kangju'16Attempts by scholars over several centuries to geographically locate and delineate Kangju have not been helped by textual corruption in both the Han Shu and Shi Ji. And yet, although several words and even whole sentences are missing, the information provided is still in the same order as that for the other 'western states', so that any gaps cannot be substantial. Certainly the distances between Xian and Beitian are not quite reconciled, and the distance from Beitian and the king's summer capital (9104 li or 3641 kms) is surely corrupt. Hulsewe and Loewe suggest that the text may originally have read 'ninety one li' (or 36 kilometres, although this seems too low),17 while Pelliot noted Wang Kuowei's suggestion of 1104 li (441 kms)18 which is a more viable figure within a country described as 'small'.

The identities of both Beitian and (Le)yueni(di) are almost impossible to determine, however, Wang Kuowei identified the former (impossibly) with Ysyk Kul19 while Pulleyblank has argued that the latter might 'represent some form of the name Jaxartes'20. The distance between Beitian and (Le)yueni(di) is described as 'seven days on horseback' in the Han Shu, which Hulsewe and Loewe suggest equals about 500 li i.e. marches of seventy lior 28 kilometres per day through the mountainous country of the region21. The identification of these two principal settlements with Samarkand and Bukhara is one obvious possibility, although the distance between the two cities by road is about 200 or so kilometres which does not reconcile with any of the given statistics.

Pulleyblank discusses the possible Tokharian philological origin of the name 'Kangju', in his reconstruction of 'Old Chinese' *khan-kiah. In the Tokharian vocabulary (Tokharian 1A) there is the word kank, which means 'stone'. Thus Kangju could mean the 'Stone Country', i.e. Samarkand (or equally Tashkend as 'Stone City')22. A.K. Narain offers a precise geographical location for Kangju: 'the northeastern wedge of modern Uzbekistan into Kirghiziya and Kazakhstan; the eastern part of this wedge formed part of Dayuan'23. This description, however, does not allow for the inclusion of any lands south of the Syr Darya, thus excluding the entire Zeravshan Valley, the cultural heart and population centre of Sogdia.

The information provided by the texts is hardly ambiguous, however, and clearly suggests the identification of the 'state' of Kangju with ancient Sogdia. Kangju is to the north of the Amu Darya and the Yuezhi's principal city of Jianshi (Khalchayan in the Surkhan Darya valley?); to the west and northwest of the Ferghana Valley (where it also apparently adjoined the clearly very substantial, post-132 realm of the Wusun); and southeast of the western realms of the Xiongnu (which must therefore have included the steppes of present-day Kazakhstan). Kangju incorporated lands on either side of the middle Syr Darya, particularly the densely occupied Zeravshan Valley south of the Syr Darya, and must surely have included Samarkand and Bukhara (as Shishkina also argues below). Hence, according to the textual evidence at least, Kangju can only convincingly be located within the general geographical region of ancient Sogdia.

Population/Size

Households: 120,000 Individuals: 600,00024

'The country is small'25

The physical dimensions of the Kangju realm may not have been vast, but the population was substantial, which allowed the ruling dynasty to maintain a formidable military force.

Military Strength

Persons able to bear arms: 120,00026

'They have 80,000 or 90,000 skilled archer warriors'27

'(it) is not subject to the Protector General'28

'In the east (the inhabitants) were constrained to serve the Xiongnu'29

'It acknowledges nominal sovereignty to (Zurcher translates as 'it is subservient to')30 the Yuezhi people in the south and the Xiongnu in the east'31

'However, Kangju felt that it was separated (from Han) by a long distance, and alone in its arrogance it was not willing to be considered on the same terms as the various other states'32

'(He Wudi - heard that) to the north, there were (people or places) such as the Da Yuezhi and Kangju, whose forces were strong; it would be possible to present them with gifts and hold out advantages with which to bring them to court'33

The Chinese were clearly impressed by the strength of Kangju, finding them arrogant and militarily self-confident. The military resources of Kangju (120,000 armed men, 80,000 - 90,000 of which were skilled and presumably mounted archers) were substantial, and would not easily be defeated by the Han. Presumably the ruling Kangju dynasty and its pastoralist allies provided the bulk of the mounted archer warriors, while the sedentised agriculturists of the river valleys could be relied upon to provide the remainder. Eschewing any military option then, Zhang Qian argued instead (in his report to Wudi) that the Kangjuans could be persuaded by Han gifts and favours to consider becoming subjects (or at least allies) of the Chinese. In short, Kangju was powerful and remote enough to resist Han attempts to join their tributary confederacy by military means, but was clearly under some sort of sovereignty obligation to both the Yuezhi and the Xiongnu.

Environment/Lifeways

'The way of life is identical with that of the Da Yuezhi'34

'Its people likewise are nomads and resemble the Yuezhi in their customs'35

'In Kangju there are five lesser kings all the five kings are subject to Kangju'36

The last reference clearly indicates that 'Kangju' should be considered both as the Han name of the 'state' (that is the realm or region) of Kangju/Sogdia, but also of the dominant faction or dynasty which was controlling that realm at the time (i.e. the Kangju dynasty). Shishkina agrees, and argues that geo-political changes in Sogdia that became apparent towards the end of the second century BCE must have been as a result of Kangju hegemony:

'The historical situation of the first century BC suggests that these changes were related to the spread of the power of the Kangju, when this dynasty controlled Samarkand and Bukhara'37

The five lesser kings noted in the Han Shu were probably subordinate tribal groups within the realm of 'greater Kangju', and given that all are listed as having specific 'seats of government' (different to the two principal settlements named as belonging to the Kangju proper), may represent sedentised, agrarian-based 'peoples' living under Kangju hegemony38

The way of life of the dominant Kangju faction was probably that of semi-nomadic militarised pastoral nomadism, similar to the assessment of the lifeway of the Yuezhi soon after their arrival north of the Amu Darya that Zhang Qian provided to the Han court. If the Kangju state is thus to be identified with ancient Sogdia under Kangju dynastic hegemony, then a brief account of Sogdian history prior to the arrival of the Yuezhi is required to identify the probable date of the establishment of Kangju power, and also to clarify the archaeological and textual evidence of subsequent Yuezhi/Kangju interaction.

Sogdian Historical Framework Prior to the Arrival of the Yuezhi

Between 553 and 550 BCE, Cyrus II (r. 559-529), a leader of the Persian Achaemenid family, overthrew Astyages, King of the Medes, and brought Mesopotamia, Parthia and Anatolia under his control. By 539 he had conquered Bactria and much of Sogdia as well, where he established a line of fortresses on the Syr Darya. Sogdia was made the thirteenth satrapy of the Achaemenids, and paid tribute to Cyrus' successors. The oldest layers of Afrasiab, the ancient site of Samarkand, date from this Achaemenid period. But, whilst the city states of Sogdia and Bactria gained considerably through their incorporation into the Achaemenid Empire, they remained intent upon regaining their independence, which parts of Sogdia may have done by c. 400 BCE39Some two centuries after Cyrus' death, Alexander of Macedon reconquered much of Central Asia, following his arrival in Bactria in 329 BCE. Alexander's principal opponent in the region was the Achaemenid ruler Darius' former satrap, Bessus, who had Darius murdered in modern-day Shahr-I Qumis before proclaiming himself as his successor. Bessus' troops consisted of armoured cavalry from Bactria and Sogdia, which, following their defeat at Gaugemela, he took back across the Amu Darya after destroying its bridges. Alexander led his troops on forced marches through the desert, crossed the Amu Darya on inflated hide rafts, and confronted his opponents who immediately sued for peace.

Bessus was executed; the Macedonians installed themselves in the satrapal palace at Maracanda (Samarkand) and Sogdia, following some seventy years of independence, found itself incorporated into the new Macedonian Empire. But while Alexander campaigned further north along the Syr Darya, the Sogdians, under the leadership of Spitamenes, rose in his rear and massacred a garrison of Macedonians, inflicting arguably the worst defeat of Alexander's career40. Over the course of the ensuing eighteen months Alexander gained his revenge by reducing the fortified towns of Sogdia one by one, starting in the Hissar Mountains and moving along the Zaravshan Valley41.

At the heart of ancient Soghd were the valleys of the Zeravshan and Kashkadarya, and in his vengeful campaign along these densely occupied valleys the Macedonians may have killed up to 120,000 Sogdians42.

Amongst the many prisoners captured during the Sogdian campaign was the Princess Roxanne, daughter of another Sogdian opponent, Oxyartes. Alexander's subsequent decision to marry Roxanne was due partly to her exceptional beauty, but was also intended as a gesture to appease the rebellious Sogdians. After Alexander's death in Babylon in 323, Bactria and Sogdia immediately rebelled but were reconquered in c. 305 by his successor Seleucus Nicator (r. 311-281 BCE). However under Seleucus' son Antiochus I (r. 281-261), Bactria and (probably) Sogdia broke away again from Seleucid hegemony. None the less, Sogdia, along with much of Central Asia, was brought into the orbit of Hellenistic influence during its brief period of Macedonian conquest.

Antiochus I minted an extensive local coinage in the region, probably at Balkh (the 'capital' of Bactria). These were coins of large denominations: staters, tetradrachms and drachms. During the last two centuries before the Common Era, several series of diverse denominations and types were struck at Sogdian mints, and coins were widely used in Sogdia and Bactria, although perhaps only by the Greek population43

None the less the native population of Sogdia became used to Greek coinage during the Seleucid period, and when the inflow of Greek coins stopped following their independence from Antiochus I, local rulers began to mint their own. As Nymark has pointed out, however, these local issues were highly debased, and in fact were 'mere imitations of the most widespread Greek coins'44.

Yet these imitations remain as crucial (and often the only) evidence of political, economic and social developments in Sogdia during the first century BCE. Furthermore, both Sogdian and Bactrian imitation issues also constitute potential evidence for the Yuezhi during the 'five-yabghu period'.

In the mid-third century (c. 250) the Seleucid Governor of Bactria, Diodotus, established an independent Graeco-Bactrian kingdom, which may also have exercised a degree of control over Sogdia. In c. 230 Diodotus' son was overthrown by one of his satraps, a Greek settler called Euthydemus, who then ruled Graeco-Bactria for about forty years until c. 190 BCE. If Sogdia was indeed part of the incipient Graeco-Bactrian state, then the evidence of the Euthydemus imitation coinage indicates that some time late in the third century, during the lifetime of Euthydemus, Sogdia became an independent entity once more45.

Euthydemus concluded a peace treaty with the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III in 206, but did not attempt to reconquer Sogdia. Instead the Graeco-Bactrians expanded south into India, establishing the Indo-Greek kingdoms. If the 'state' of Kangju is indeed to be identified as Sogdia, then it was during this period of post-Seleucid independence, i.e. from c. 210 BCE, that the region came under the hegemony of the Kangju dynasty, which then continued to rule an independent Sogdia until it came under Kushan political influence early in the first century CE. As Bopearachchi concludes, under the Kangju dynasty 'Sogdiana probably remained free at least until the arrival of the Yuezhi in c. 130 BC'46.

The Passage of the Yuezhi through Kangju/Sogdia

Although neither of the Chinese sources categorically states that the Yuezhi horde passed through Kangju, the only logical inference to be drawn from the texts is that they did. In addition, Ptolemy continued to unknowingly chart the course of the Yuezhi migration by noting a group he this time called the Tachoroi (surely another variant of Tocharian) dwelling in Sogdia47.The conclusion that the Yuezhi must have passed through the region is further strengthened by the fact that the Han sources do unequivocally show that Zhang Qian passed through Kangju during his search for the Yuezhi. The Han envoy was obviously well informed by the rulers of Dayuan as to the route followed by the Yuezhi who provided him with guides to lead him to the Yuezhi, unless they knew the migrants' route and probable whereabouts? And thus is likely to have followed closely in the original footsteps of his quarry. The chronology is straightforward enough.

C. 132/1 BCE: The Yuezhi depart Dayuan and continue their migration to the west

That the Yuezhi continued westwards in their migration following their passage through (and possibly winter residency in) Dayuan is implicit in the key Han Shu passage: 'passing Dayuan (and) proceeding west to subjugate Daxia'48.There are three feasible route options west from Ferghana, whether starting from present-day Kukon in the centre of the valley, or Isfara in the southwest. The first is due north and then west, across the 2267 metre Kamcik Pass and through Angren into Tashkent, thence southwest to Samarkand. A second and more direct route is due west through present-day Chugand and Zizzach, thence southwest into Samarkand. However, given that the Zeravshan Valley was the agricultural and population heartland of Sogdia/Kangju (information probably given to the Yuezhi by the rulers of Dayuan who were no doubt anxious to encourage the Yuezhi to move on and seek suitable settlement lands elsewhere), the migrating horde may have chosen to follow a third route option from Chugand, south over the 3378 metre Sahristan Pass, then down into the upper Zeravshan Valley. If the Yuezhi leadership decided upon this latter route, then it would indeed have been necessary for them to winter in southern Ferghana before attempting the crossing of this high pass in the spring.

The Shi Ji also implies this in noting (in Watson's translation) that the Yuezhi 'moved far to the west, beyond Dayuan'49, which Zurcher reads as: 'They passed through Dayuan and to the west of thatcountry'50. Between Dayuan and Daxia (Bactria) lay only Kangju/Sogdia; anyone moving to the west, beyond Dayuan (or to the west of that country) and heading for northern Bactria would have to have passed through Sogdia. This probability is then strengthened by the unambiguous statement that Zhang Qian was taken to Kangju by his Dayuan guides and interpreters, and from there proceeded directly to the realm of the Da Yuezhi in northern Bactria.

129/128 BCE: Zhang Qian also passes through Kangju

The Han Shu notes that:'(the king of Dayuan) sent off (Zhang) Qian, providing him with interpreters and guides. He reached Kangju who passed him on to the Da Yuezhi'51.Or as Sima Qian puts it:

'The king of Dayuan trusted his words and sent him on his way, giving him guides and interpreters to take him to the state of Kangju. From there he was able to make his way to the land of the Great Yuezhi'52.Despite its obvious military strength, Kangju (like Dayuan) also apparently facilitated (or at least did not hinder) the passage through its territory of both the migrating Yuezhi horde in c. 131 and the Han envoy in c. 128 BCE. Given the size of its military resources, Kangju was powerful enough to be not 'easily defeated by Han forces',53 although it was 'constrained to serve the Xiongnu' in the east,54 and (later) would acknowledge 'nominal sovereignty' (or even become 'subservient to') the Yuezhi in the south'55.

Does this acknowledgement suggest that parts of Sogdia (and the most populous parts at the Zeravshan valley and Samarkand) were actually invaded and defeated by the migrating Yuezhi, and then forced into a subordinate relationship thereafter? Certainly Torday is prepared to argue that not only did the Yuezhi defeat the Kangju dynasty in Sogdia, but in northern Bactria as well where he suggests the Kangju were also ruling: