Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/12845022/Bronze_Age_cire_perdue_revolution._Imperative_of_archaeometallurgical_evaluation_of_bronze_Pine_cone_and_pair_of_bronze_peacocks_in_Vatican

Writing systems of the Bronze Age deployed hieroglyphs. Many hieroglyphs are signifiers of metalwork. From among the animals available from the environment along the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa, only a select set of animals were used: for example, bull, markhor or stag, tiger, peacock, eagle. It is remarkable that such a set of signifiers signify metalwork categories in Meluhha glosses of the Bronze Age using rebus-metonymy layered cipher.

The word Meluhha itself signifies cognate milakkha'copper' (Pali).

Some objects or figurines were also deployed as hieroglyphs: for example, pine cone, decrepit woman, wallet or basket. These were also signifiers of metalwork: kaNDe'pine cone' Rebus: kANDa'metalware', kANDa 'water'; dhokra'decrepit woman', dhokra'wallet or basket' Rebus: dhokra'cire perdue metalcaster artisan'.

Imperative of archaeometallurgical evaluation of bronze Pine cone and pair of bronze peacocks in Vatican is suggested because there are indications that the objects were originally in a structure in the Pompeii temple complex of Isis who is the divinity of seafarers. It is possible that the structure displaying the bronze pine cone and bronze peacocks were erected by metalworkers who were Meluhha seafaring merchants and who venerated Isis.

Nahal Mishmar cire perdue artifacts are dated to the 4th millennium BCE which necessitate a re-evaluation of the chronology in archaeometallurgy of this significant innovation in metallurgy -- the ability to create metal castings using lost-wax or cire perdue tecnique which resulted in a veritable revolution in commmunication systems deployed by metalworkers and seafaring merchants to market the metalwork.

Bibliographical resources related to cire perdue metallurgy and other metal technologiestogether with evidences of metalwork as hieroglyphs are collated and presented.

Kenoyer, Jonathan M. & Heather ML Miller, Metal technologies of the Indus valley tradition in Pakistan and Western India, in: The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, 1999, ed. by VC Piggott, Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, pp.107-151

https://www.scribd.com/doc/267931203/Kenoyer-Jonathan-M-Heather-ML-Miller-Metal-technologies-of-the-Indus-valley-tradition-in-Pakistan-and-Western-India-in-The-Archaeometallurgy-of

https://www.academia.edu/1223547/The_Origins_of_Metallurgy_in_Prehistoric_Southeast_Asia_The_View_from_Thailand Pigott, VC and Roberto Ciarla, On the origins of metallurgy in prehistoric Southeast Asia: the view from Thailand Abstract. Research over the last 30 years has markedly improved our understanding of metallurgical developments inprehistoric Thailand. The chronology of its earliest appearance, however, remains under debate. Current evidence suggeststhat tin-bronze metallurgy appeared rather abruptly as a full-blown technology by the mid-2nd millennium BC. Questionsalso continue to arise as to the sources of the technology. Current arguments no longer favour an indigenous origin; research-ers are increasingly pointing north into what is today modern China, linking metallurgical developments to the regions of the Yangtze valley and Lingnan and their ties to sophisticated bronze-making traditions which began during the Erlitou (c.1900–1500 BC) and the Erligang (c1600–1300 BC) cultures in the Central Plain of the Huanghe. In turn, links betweenthis early 2nd-millennium BC metallurgical tradition and the easternmost extensions of Eurasian Steppe cultures to thenorth and west of China have been explored recently by a number of scholars. This paper assesses broadly the evidence for‘looking north’ into China and eventually to its Steppe borderlands as possible sources of traditions, which, over time, maybe linked to the coming of tin-bronze in Thailand/Southeast Asia.

The lost-wax method is well documented in ancient Indian literary sources. The Shilpa shastras, a text from the Gupta Period (c. 320-550 CE), contains detailed information about casting images in metal. The 5th-century CE Vishnusamhita, an appendix to the Vishnu Purana, refers directly to the modeling of wax for making metal objects in chapter XIV: "if an image is to be made of metal, it must first be made of wax." Chapter 68 of the ancient Sanskrit text Mānasāra Silpa details casting idols in wax and is entitled "Maduchchhista vidhānam", or the "lost wax method". The Mānasollāsa (also known as the Abhilasitārtha chintāmani), allegedly written by King Bhūlokamalla Somesvara of the Chalukya dynasty of Kalyāni in CE 1124–1125, also provides detail about lost-wax and other casting processes. In a 16th-century treatise, the Uttarabhaga of the Śilparatna written by Srïkumāra, verses 32 to 52 of Chapter 2 ("Linga lakshanam"), give detailed instructions on making a hollow casting. (Kuppuram, Govindarajan (1989). Ancient Indian Mining, Metallurgy, and Metal Industries. Sundeep Prakashan; Krishnan, M.V. (1976). Cire perdue casting in India. Kanak Publications.)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

June 7, 2015

Carving a global icon: The Nataraja bronze and Coomaraswamy’s legacy

![]()

![]()

![]()

Benjamin W. Roberts, Christopher Thornton, 2014, Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Syntheses, Springer Science & Business Media

Hunt, LB, 1980, The long history of lost wax casting, Springer Science, pp.63-79

https://www.scribd.com/doc/267923381/Hunt-LB-1980-The-long-history-of-lost-wax-casting-Springer-Science-pp-63-79

Casting of bronze began in Southeast Asia first in northeastern Thailand (Bon Chiang). "In the words of one writer, 'bronze casting bean in Southeast Asia and was later borrowed by the Chinese, not vice versa as the Chinese scholars have always claimed' (Neher, p.186)...bronze-casting technology spread from Southeast Asia to China rather than from China to Southeast Asia, or, at least, developed independently in Southeast Asia and in China, then the Dong-son bronze technology probably developed from local or regional industries rather than from imported Chinese skills...Vietnamese archaeologists...have found that the earliest bronze drums of Dong-son are closely related in basic structural features and in decorative design to the pottery of the Phung-nguyen culture. They further suggest that the Dong-son culture of northern Vietnam had important links with Tibeto-Burman cultures in Yun-nan, with Thai cultures in Yun-nan and Laos, and, especially, with Mon-Khmer cultures in Laos, particularly oon the Tran-ninh plateau...or 'Plan of Jars', is the most natural route from northern Vietnam to northeastern Thailand. Aside from technical aspects, Dong-son culture was strongly influenced by seaborne contacts. The distinctive features and designs on the Dong-son drums are generally believed to 'express one phase of maritime art'. Boats filled with oarsmen and warriors surrounded by seabirds and other forms of maritime life unmistakably testify to the ascendancy of sea-based power." (Taylor, Keith W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 313).

The first datings of the artifacts using the thermoluminescence technique resulted in a range from 4420 BCE to 3400 BCE which would make Ban Chiang the earliest Bronze Age culture in the world. Radiocarbon dates have revised the dates to ca. 2100 BCE of an early grave and bronze making is said to have begun ca. 2000 BCE as evidenced by crucibles and bronze fragments. The debate about the dates..."has focused on bronzes that were grave goods and has not addressed the non-burial metals and metal-related artefacts. This article summarizes the burial and non-burial contexts for early bronzes at Ban Chiang, based on the evidence recovered from excavations at the site in 1974 and 1975. New evidence, including previously unpublished AMS dates, is presented supporting the dating of early metallurgy at the site in the early second millennium B.C. (c. 2000-1700 B.C.). This dating is consistent with a source of bronze technology from outside the region. However, the earliest bronze is too old to have originated from the Shang dynasty, as some archaeologists have claimed. The confirmed dating of the earliest bronze at Ban Chiang facilitates more precise debate on the relationship between inter-regional interaction in the third and second millennia in Asia and the appearance of early metallurgy." -- EurASEAA 2006, Bougon papers ("White, J.C. 2008 Dating Early Bronze at Ban Chiang, Thailand. In From Homo erectus to the Living Traditions. Pautreau, J.-P.; Coupey, A.-S.; Zeitoun, V.; Rambault, E., editors. European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Chiang Mai, pp. 91-104.")

http://seasiabib.museum.upenn.edu:8001/pdf_articles/bookchapters/2008_White.pdf

"The Đông Sơn bronze drums exhibit the advanced techniques and the great skill in the lost-wax casting of large objects, the Co Loa drum would have required the smelting of between 1 and 7 tons of copper ore and the use of up to 10 large casting crucibles at one time." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%90%C3%B4ng_S%C6%A1n_culture

THE LOST-WAX METHOD OF BRONZE CASTING

The Dong Son craftsmen did wonderful things with bronze. Most of what they created was produced by the “lost-wax method.” In this method, an original piece (sculpture, jewelry, bowl, weapon blade, etc.) was hand-made of paraffin or other wax. Additional wax tubes were added, which serve as exits for the wax and entrances for the bronze. The entire product was covered with clay, in layers of progressively thicker consistency. The only parts that protruded from the clay mass were the wax tubes. It looked much like a potato with a few candles sticking out. When heat was applied, the protruding wax rods melted first. As it melted, the remaining wax flowed out through the channels left in the clay by the melted tubes. The piece was then repositioned and molten bronze was poured into the channels. Ideally, the bronze then flowed into all the negative space that had once been occupied by the wax. At the same time, the air that had been in those spaces was forced out. For this to occur, the number and placement of the tubes was critical. If some air became trapped in small spaces (usually at the ends of narrow segments, such as a hand or finger), the bronze would not be able to enter that space. The final product, then, would “have no hand” (or whatever). After the bronze had hardened, the clay was then cracked and removed, leaving a bronze replica of the original wax piece, including the tubes. The next step was to remove the tubes, remove extra bits of bronze and polish the surface of the piece (this last is called chasing)." http://giahoithutrang.blogspot.in/2014/02/blog-post.html

![]()

Close-up view of a Dong Son bronze drum with hieroglyphs cast using lost-wax metallurgical techniques.

![332px-Dancing_Girl_of_Mohenjo-daro]() Replica of Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro

Replica of Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro

Writing systems of the Bronze Age deployed hieroglyphs. Many hieroglyphs are signifiers of metalwork. From among the animals available from the environment along the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa, only a select set of animals were used: for example, bull, markhor or stag, tiger, peacock, eagle. It is remarkable that such a set of signifiers signify metalwork categories in Meluhha glosses of the Bronze Age using rebus-metonymy layered cipher.

The word Meluhha itself signifies cognate milakkha'copper' (Pali).

Some objects or figurines were also deployed as hieroglyphs: for example, pine cone, decrepit woman, wallet or basket. These were also signifiers of metalwork: kaNDe'pine cone' Rebus: kANDa'metalware', kANDa 'water'; dhokra'decrepit woman', dhokra'wallet or basket' Rebus: dhokra'cire perdue metalcaster artisan'.

Imperative of archaeometallurgical evaluation of bronze Pine cone and pair of bronze peacocks in Vatican is suggested because there are indications that the objects were originally in a structure in the Pompeii temple complex of Isis who is the divinity of seafarers. It is possible that the structure displaying the bronze pine cone and bronze peacocks were erected by metalworkers who were Meluhha seafaring merchants and who venerated Isis.

Nahal Mishmar cire perdue artifacts are dated to the 4th millennium BCE which necessitate a re-evaluation of the chronology in archaeometallurgy of this significant innovation in metallurgy -- the ability to create metal castings using lost-wax or cire perdue tecnique which resulted in a veritable revolution in commmunication systems deployed by metalworkers and seafaring merchants to market the metalwork.

Bibliographical resources related to cire perdue metallurgy and other metal technologiestogether with evidences of metalwork as hieroglyphs are collated and presented.

Kenoyer, Jonathan M. & Heather ML Miller, Metal technologies of the Indus valley tradition in Pakistan and Western India, in: The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, 1999, ed. by VC Piggott, Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, pp.107-151

https://www.scribd.com/doc/267931203/Kenoyer-Jonathan-M-Heather-ML-Miller-Metal-technologies-of-the-Indus-valley-tradition-in-Pakistan-and-Western-India-in-The-Archaeometallurgy-of

https://www.academia.edu/1223547/The_Origins_of_Metallurgy_in_Prehistoric_Southeast_Asia_The_View_from_Thailand Pigott, VC and Roberto Ciarla, On the origins of metallurgy in prehistoric Southeast Asia: the view from Thailand Abstract. Research over the last 30 years has markedly improved our understanding of metallurgical developments inprehistoric Thailand. The chronology of its earliest appearance, however, remains under debate. Current evidence suggeststhat tin-bronze metallurgy appeared rather abruptly as a full-blown technology by the mid-2nd millennium BC. Questionsalso continue to arise as to the sources of the technology. Current arguments no longer favour an indigenous origin; research-ers are increasingly pointing north into what is today modern China, linking metallurgical developments to the regions of the Yangtze valley and Lingnan and their ties to sophisticated bronze-making traditions which began during the Erlitou (c.1900–1500 BC) and the Erligang (c1600–1300 BC) cultures in the Central Plain of the Huanghe. In turn, links betweenthis early 2nd-millennium BC metallurgical tradition and the easternmost extensions of Eurasian Steppe cultures to thenorth and west of China have been explored recently by a number of scholars. This paper assesses broadly the evidence for‘looking north’ into China and eventually to its Steppe borderlands as possible sources of traditions, which, over time, maybe linked to the coming of tin-bronze in Thailand/Southeast Asia.

The lost-wax method is well documented in ancient Indian literary sources. The Shilpa shastras, a text from the Gupta Period (c. 320-550 CE), contains detailed information about casting images in metal. The 5th-century CE Vishnusamhita, an appendix to the Vishnu Purana, refers directly to the modeling of wax for making metal objects in chapter XIV: "if an image is to be made of metal, it must first be made of wax." Chapter 68 of the ancient Sanskrit text Mānasāra Silpa details casting idols in wax and is entitled "Maduchchhista vidhānam", or the "lost wax method". The Mānasollāsa (also known as the Abhilasitārtha chintāmani), allegedly written by King Bhūlokamalla Somesvara of the Chalukya dynasty of Kalyāni in CE 1124–1125, also provides detail about lost-wax and other casting processes. In a 16th-century treatise, the Uttarabhaga of the Śilparatna written by Srïkumāra, verses 32 to 52 of Chapter 2 ("Linga lakshanam"), give detailed instructions on making a hollow casting. (Kuppuram, Govindarajan (1989). Ancient Indian Mining, Metallurgy, and Metal Industries. Sundeep Prakashan; Krishnan, M.V. (1976). Cire perdue casting in India. Kanak Publications.)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

June 7, 2015

Carving a global icon: The Nataraja bronze and Coomaraswamy’s legacy

Sharada Srinivasan (2014)

This paper attempts a historiography of the Nataraja bronze which famously came to wider international attention through Ananda Coomaraswamy’s (1912) essay, ‘Dance of Siva’, and his explorations into its symbolism; for which he is arguably best known in posterity. Cast over several hundred centuries, however, with few associated inscriptions, there have been some lacunae in understanding its development in stone and bronze. There have also been debates about the actual or original significance since Coomaraswamy’s interpretations seemed to have been based on later texts. Although this bronze is almost synonymous with the Imperial Chola dynasty of Tamil Nadu, there is a certain lack of clarity on earlier and later manifestations and other regional developments in India and in spheres of interaction beyond such as Sri Lanka. Insights from archaeometallurgical and stylistic study and documentation of surviving bronze casting practices in Tanjavur district throw new light on techno-cultural aspects of south Indian bronzes and this enigmatic icon. The place the image has acquired in the global imagination through the writings of well known artists, scientists and thinkers following Coomaraswamy’s musings is briefly elucidated here, as well as his contributions to the documentation of arts and crafts and the archaeometallurgy of the southern Indian subcontinent.

‘Archaeometallurgy’ in the southern Indian subcontinent and Coomaraswamy’s role in arts and crafts awareness

In the past few decades, the discipline of archaeometallurgy has emerged as an important sub-discipline in archaeology and scientific archaeology. It is concerned with the application of scientific techniques in the study of metal artefacts, not only for understanding their methods of manufacture from related studies of mining, metal extraction or alloying but also for the implications of technical analysis in gaining further insights into issues concerning the history of art such as the source of artefacts and stylistic affiliations. The stature of Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) as a towering art historian of the twentieth century is well known through his writings integrating visual art, religion, literature and metaphysics. However, what is perhaps less well recognized is that even in terms of these recently defined fields of ‘archaeometallurgy’ and ‘ethnoarchaeology’ his contributions are equally seminal, especially concerning the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. From his education as a scientist and geologist he turned his interests towards the documentation of artisanal technologies and crafts including metalworking. In this sense, his work in some ways even anticipated that of Cyril Stanley Smith, another Renaissance personality and materials scientist and aesthetician who is recognized as a founding figure in the field of archaeometallurgy. A student of botany and geology at the London University who in fact distinguished himself by discovering Thorianite (Rangarajan 1992), Coomaraswamy took up the post of Director of the Mineralogical Survey of the island (Moore in Foreword, Coomaraswamy 1909).

Coomaraswamy’s (1951: 190-3) early documentation of finds of iron smelting slags at Tissamaharama and ethnographic studies of iron smelting and furnaces near Balagoda and of steel making by elderly artisans in Alutnuvara are pioneering in terms of early archaeometallurgical studies related to Sri Lanka and indeed South Asia.

What sets Coomaraswamy apart though, is the way in which his interests were tempered by a deeply humanistic concern for the milieu of the traditional craftsmen and artisans and his efforts to revitalize them. Through his geological and rural fieldwork experiences, from around 1902 he became much more concerned and engaged with documenting the traditional arts and crafts of Ceylon in terms of social history and social conditions. Although he was part English, he became very perceptive to the negative effects that European colonization had had on the traditional artisanal knowledge of South Asia. He founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society in 1906 which had as its aim the discouragement of ‘thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European customs’ and preservation of traditional crafts and the social values that had shaped them (Oldmeadow 2004: 194-202). He was among the leading figures who took an early interest in the Indian crafts and its revival including Sir George Birdwood and E.B. Havell. His writings about the Indian craftsman still ring true: ‘Indian society presents to us no more fascinating picture than that of the craftsman as an organic element in the national life…’ (Coomaraswamy 1909: Foreword by A. Moore). He was also involved in the Swadeshi movement promoted by key figures such as MK Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore, in terms of the need for sustaining traditional artisanship. These movements also set the stage for post-Independence developments, whereby Mangalore-born Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay almost single-handedly turned around the situation on Indian crafts with the setting up of All India Handicrafts Board and through her far reaching engagement.

‘Dance of Siva’ and the world stage

Son of a Ceylonese Tamil father Muthu Coomaraswamy, a legislator and philosopher who died when he was a baby, and an English mother, Elizabeth Beeby, it seems that the languages that Coomaraswamy held mastery over, in terms of his art historical and philosophical expositions were Sanskrit and Pali, the language of the rich body of Theravada Buddhist canon followed by the Sinhalese majority of his homeland, rather than Tamil. Nevertheless, it may be fitting in the light of his ancestry that perhaps Coomaraswamy’s genius as a writer flourished most eloquently in his inspired exposition of the Nataraja bronze made famous in Chola bronzes from Tamil Nadu, of the dancing Hindu god Shiva, and based on his interpretations of Tamil Saiva Siddhanta texts. His background as scientist-aesthetican comes through in his essay ‘The Dance of Siva’ (1912), where he wrote: ‘In the night of Brahma, Nature is inert, and cannot dance till Shiva wills it. He rises from His rapture, and dancing sends through inert matter pulsing waves of awakening sound, and lo! matter also dances appearing as a glory round about Him. Dancing He sustains its manifold phenomena. In the fullness of time, still dancing, he destroys all forms and names by fire and gives now rest. This is poetry; but none the less science.’

Coomaraswamy’s (1912) interpretation of the Nataraja bronze appealed widely to leading figures of his time (Srinivasan 2010). His writings, such as the passage above, seem to be echoed in T.S. Eliot’s famous poetic lines ‘At the still point of the turning world…there the dance is…’ Celebrated French sculptor August Rodin (1913) in his essay ‘La Danse de Siva’ illustrated it with the same Nataraja bronze from the Government Museum, Chennai as did Coomaraswamy. His writings also provided something of a post-modernist metaphor for savouring the implications of modern physics. Fritjof Capra (1976: 258) further catapulted the Nataraja into the global spotlight by writing that, as envisaged through Coomaraswamy’s writings, ‘Siva’s dance is the dance of sub-atomic particles’ (Srinivasan 2003). Such writings also led astronomer Carl Sagan to state that the Nataraja bronze held out a premonition of astronomical ideas. The distance traversed by such eastern art forms onto the world stage can be gauged from the fact that the CERN Cosmic Lab, which has witnessed recent excitement over the Higgs Boson (also nicknamed the ‘God particle’), has the largest Nataraja image in the world today, installed there with plaques citing quotes from Coomaraswamy and Capra. This impressive work had been undertaken by the master craftsman Rajan with support from IGCAR Kalpakkam (Baldev Raj, pers comm.). The Nataraja bronze figured on the dust jacket of Belgian scientist Ilya Prigogine’s book (Glansdorff and Prigogine 1971) as if providing visual metaphors for abstract concepts related to thermodynamics, flux and stability. Notwithstanding the romanticism, Coomaraswamy’s writings assume significance in the ways they engaged Eurocentric western audiences in his times towards a better rapprochement of Indian thought and art. Coomaraswamy’s transcendental approach to Indian art influenced leading art historians such as Stella Kramrisch (Oldmeadow 2004), though in recent times art history has seen newer revisionist approaches.

Insights from bronze casting traditions at Swamimalai, Tanjavur district

Micro-structure of 13thSouth

Indian bronze

Images were made in southern India of Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religious affiliations. Whereas Buddhist and Jain bronzes often have donor inscriptions, Hindu images were rarely inscribed. An overwhelming majority of south Indian bronzes, especially of Hindu affiliation, are from the Tamil region and more specifically the Tanjavur region. South Indian metal Hindu icons were made as utsava murti or festival images that were taken out in rituals and festivals involving processional worship and were not generally intended for worship in the main sanctum. South Indian statuary bronze is made by a process of cire perdue or lost wax casting, a technique which has a long history in the subcontinent. The lost wax processes known as Madhuchchhisthavidhana is also described in the southern Indian text the Manasollasaattributed to the Chalukyan king Somesvara. The Kasyapa Silpasatra, a Tamil text discusses iconometric aspects of the modelling of the image including the navatala methods of proportioning the icon derived from texts such as the Brhat Samhita.

Chola inscriptions describe the image of the deity as ghanamagha or dense, i.e. solid, and the bull or rishabha as chhedya or hollow cast. As an example, a fine set of Chola bronzes from Tandanttottam is cast such that the main images of Rishabhavahana and consort are solid cast and the damaged bull is hollow cast (Sivaramamurti 1963: 14). Present day sthapatis or icon makers also maintain that the metal deities for processional worship in temples should never be hollow cast because that would be inauspicious although this rule does not apply to the vahana or the vehicles in animal forms associated with deities. According to Coomaraswamy (1956:154) and Von Schroeder (1981:19), the Sariputra, a Ceylonese text (ca 12th-15th century) based on South Indian sources warns against the making of hollow images which would lead to calamities such as famine and warfare. Interestingly, although early historic images both from southern India such as Amaravati and Sri Lanka tend to be hollow cast, from the early medieval period they are invariably solid cast, unlike northern Indian images which are most often hollow cast.

Unlike European sculptures which were usually made from physical models, South Indian icon makers in the past are thought to have not used models but were expected to memorise all thetalamana canon of measurement and then invoke the images of the deities in their minds usingdhyanaslokas or verses which were meant to help mentally visualise the qualities and attributes of a particular image to be carved in wax (Reeves 1962: 114, Gangoly 1978). Since the wax melted away each bronze was hence apparently a unique product of the craftsman’s imagination. There were also dhyanaslokas pertaining to each type of deity to visualise the qualities and attributes, associated myths and symbolism and these were recited and mentally invoked before executing the image (Rathnasabhapathy 1982). Hence, according to Reeves (1962: 115), it was by a process of dhyana-yoga defined by Coomaraswamy as ‘visual contemplative union and realisation of formal identity with an inwardly known image’, that the master craftsmen modelled images in wax.

Radhakrishna Sthapati of Swamimalai

making a wax model of a Nataraja bronze

photographed in 2003

E. B. Havell, writing perceptively in 1908 inIndian Sculpture and Painting (as cited in Coomaraswamy 1989: 183) seems to have witnessed something of the deep intellectual and spiritual tradition which must have informed the high craftsmanship of antiquity, commenting that ‘even at the present day the Indian craftsman, deeply versed in his Silpa Sastras, learned in folk-lore and in national epic literature is, though, excluded from Indian universities – or rather, on that account – far more highly cultured, intellectually and spiritually, than the average Indian graduate. In medieval times the craftsman’s intellectual influence, being creative and not merely assimilative, was at least as great as that of the priest and bookman’. Figure 1 shows the traditional master craftsman Radhakrishna Stapathy of Swamimalai, carving a wax model of a Nataraja image, which also movingly captures something of this inner meditative and contemplative spirit that underpinned the great artistic traditions of South Asian antiquity. While the preservation of crafts traditions themselves remains a challenge in the present day notwithstanding the very laudable and far reaching efforts of the Crafts Councils in India, what also remains a matter of concern is the decline in artistic standards due to the loss of the traditional aesthetic and philosophical milieu within which the crafts functioned.

The solid lost wax image casting process is still followed by traditional icon makers known asSthapatis such as at Devasenasthapati’s workshop in Swamimalai. Here, the image is made from a solid piece of wax, then covered with three layers of clay made from alluvial clay from the Kaveri to make a mould, which is then heated so that the wax is melted out and finally the molten metal is poured into the mould which solidifies into the cavity in the form of the image. The odiolai or coconut palm leaf is used to mark out the tala measurements for the dimensions of the icon. Although realistic portraiture was not common, it seems that bronzes representing important personalities were made now and then even if they were not physical portraits. For example an inscription of Rajendra I, mentions offerings for worship made to the images of the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi who was a great patroness of temples and bronzes (Balasubrahmanyam 1971: 182). It is thought that the Devi at the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery may represent the widowed queen’s portrait due to the simple yet regal bearing (Dehejia 1990: 36-8, Srinivasan 2001).

Analysis of bronzes and the enigmatic panchaloha composition of icons

South Indian metal icons are often described as panchaloha or icons made of five metals in colloquial terms. South Indian Chola inscriptions themselves only refer to cepputtirumeni or copper images (Nagaswamy 1988: 146-7). The mystique of panchaloha is captured in Parker’s (1992) quote of a traditional sthapati in Tamil Nadu that ‘Panchaloham as a material has the second greatest sakti or power, after the material stone used for the mulamurti, followed by wood and last of all cutai (brick and mortar)’. The Caraka Samhita of the 2nd or 3rd century CE speaks of the ‘pouring of the five metals of gold, silver, copper, tin and lead into various wax-moulds’ (Von Schroeder 1981: 17).

During the course of my doctoral thesis, I technically analysed 130 important South Indian metal icons from the early historic to late medieval periods sampled from collections including Government Museum, Madras or Chennai, Victoria and Albert Museum, and British Museum, London using multi-element spectro-chemical compositional analysis and lead isotope analysis (Srinivasan 1996). The results show that some 80% of the sampled images were leaded bronzes and the rest leaded brasses, so that there is no significant alloying of five metals.

However the Swamimalai sthapati interviewed in 1990 mentioned that the images are known aspanchaloha icons because in addition to three metals of copper, lead and zinc or tin, very minor amounts of silver and gold were added more as a shastra or ritual. Analyses support the notion of the addition of traces of gold and silver to some medieval images (Srinivasan 1999). We commissioned and documented the making of a panchaloha icon in 1990. About 100 mg. of gold and silver was melted in a ladle by the artisans. My husband Digvijay was invited to pour the gold and silver into the crucible together with the sthapati before casting as it is considered auspicious. In this light, it is interesting to note also some of Coomaraswamy’s (1951: 205) observations related to five-metalled alloys of ‘pas-lo’ which he mentions in the context of Sri Lanka was used too make ‘certain small articles such as nails used in superstitious ceremonies’. This suggests too that this alloy if it was used had more of a ceremonial or ritualistic purpose than practical utility.

From about the 8th century AD large solid castings up to 1 metre high began to be made in the region of Tamil Nadu with images such as the Nataraja images of Siva as cosmic dancer (Fig 2) weighing up to 200 kg. From the author’s analyses it seems that some 80% of 130 south Indian images from the early historic to late medieval period were leaded bronzes with tin contents up to 15%, at the limit of solid solubility of tin in copper, with lead up to 25%. The rest were leaded brasses with up to 25% zinc. None of these images had tin exceeding 15%, which is the limit of solid solubility of tin in copper. This ensured that the bronzes were solid, as cast bronzes with a tin content of over 15% are breakable. The average tin content in icons of the Chola period (c. 850-1070 A.D) was the highest at around seven percent. The tin content was less in later Chola and Vijayanagara and Nayaka bronzes. Lead isotope analysis of an early historic zinc ingot with a Brahmi inscription suggests an attribution to the Andhra region and it also matched a votive brass lamp with 14% zinc from the Andhra Krishna valley region. The highest average amounts of zinc were found in the bronzes of the later Chalukya period of 2.5 percent. Fig 2 shows a Nataraja bronze from Kankoduvanithavam with 8 percent tin and 8 percent lead and finger-printed to about the mid 11th century. Fig. 3 is a microstructure of a 13th century South Indian image of leaded bronze studied by the author at the Institute of Archaeology, London.

The mastery of solid cast bronze casting by South Indian and also Sri Lankan sculptors is something remarkable in the history of art. As implied by materials scientist V.S. Arunachalam (Nehru Centre lecture, 1993) in the title of his lectures ‘From Temples to Turbines’, the modern technology of investment casting used to make turbines has an illustrious history rooted in the subcontinent’s sacred past. Indeed, Chola bronzes bring together metallurgy and aesthetics, and the sensuous and the sacred in a remarkable fashion (Srinivasan and Ranganathan 2006).

Interpretations of the Nataraja and insights on dating from technical studies and questions about the ‘cosmic’ dimension

Nataraja bronze,c 1050 CE,

from Kankoduvanithavam in Government

Museum, Chennai

As reported in the author’s doctoral thesis and papers (Srinivasan 1996, 1999, 2004), 130 representative south Indian metal icons from museums including the Government Museum, Chennai, Victoria and Albert Museum, London and British Museum, London were compositionally analysed for 18 elements, and sixty of these images were analysed for lead isotope ratios. The lead isotope ratios and trace elements of a control group of images were calibrated against the stylistic and inscriptional evidence to yield characteristic finger-prints for different groups of images as Pre-Pallava (c. 200-600 C.E) [8], Pallava (c. 600-875 C.E) [17], Vijayalaya Chola (c. 850-1070 C.E) [31], Early Chalukya-Chola (c. 1070-1125 C.E) [12], Later Chalukya-Chola (c. 1125-1279 C.E) [17], Later Pandya (c. 1279-1336 C.E) [15], Vijayanagara and Early Nayaka (c. 1336-1565 C.E) [20] and Later Nayaka and Maratha (c. 1565-1800 C.E) [12]. Using these calibrations, images of uncertain attributions could be stylistically re-assessed (Srinivasan 1996).

This exercise of archaeometallurgical finger-printing suggested that the classic Nataraja metal icon of Siva dancing with an extended right leg in bhujangatrasita karana originated in the Pallava period (c. 800-850 C.E.) rather than the 10th century Chola period (Srinivasan 2001, Srinivasan 2004). Two Nataraja images, one from the British Museum and one from the Government Museum, Chennai which were thought to have been of the Chola period, had lead isotope ratio and trace element finger-prints that better matched the Pallava group. No Nataraja bronzes could be identified datable to the Vijayanagara period (c 14th-16th century) which was predominantly a Vaishnava dynasty. It is generally thought that stone Nataraja images in the round come more into prominence during the patronage of Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi (c. 940 CE) at temples such as Kailasanathaswami. However, the studies mentioned before suggest that bronze Nataraja images may have preceded stone ones. Bennink et al. (2012) have pointed to free standing stone Nataraja images with consort Sivakami or Parvati akin to the bronze forms represented in Chola utsava murtis which may have copied the bronze versions.

Citing the 13th century Tamil text Unmai Vilakkam (verse 36) thought to have been composed around Chidambaram, Coomaraswamy (1912: 87) explained the significance of the dance as ‘Creation arises from the drum: protection proceeds from the hand of hope; from fire proceeds destruction: the foot held aloft gives release’. He added that the dance represented the five activities (pancakritya) of Shrishti (creation), Sthiti (preservation), Samhara (destruction),Tirobhava (illusion), and Anugraha (salvation). As such, we may note that Coomaraswamy does not in his own essay actually use the term ‘Cosmic Dance of Siva’, the phrase by which the Nataraja is often popularly described the world over at various museums, although he does mention that the above ‘cosmic activity is the central motif of the dance’. Furthermore, although Coomarawasmy (ibid.) mentions the ‘tandava’ mode of dance of Shiva performed in cemeteries and burning grounds, he does not in his essay actually use the term ‘ananda-tandava’. As mentioned in Zvelebil (1985: 2) it was K.V. Soundara Rajan who vigorously highlighted the identification of the Nataraja bronze with the extended leg with the ‘ananda-tandava’ murti or ‘awesome dance of bliss’, while Zvelebil (ibid.) opines that the word ‘tantu’ is derived from the Tamil/Dravidian word for leaping over.

Some of the problems in only relying on Coomaraswamy’s metaphysical interpretations of the Nataraja bronze which seem to have been based on later 13th century texts were highlighted by various scholars. As Zvelebil (1998:8) put it insightfully, both in praise and criticism, that the essay ‘quotes in somewhat haphazard fashion a number of Tamil texts without much respect for their dating and historical sequence’, adding that ‘the essay is beautiful and has contributed in a very important manner to Western understanding of Indian art..’. In a thought provoking paper Padma Kaimal (1999) suggests alternate shades of meaning to the Shiva Nataraja bronze, somewhat removed from Coomaraswamy’s mystical approach. She argues that the cult of Nataraja may have been strategically propagated by the Imperial Cholas due to the martial implications associated with the dance of destruction, as a symbol of power and their expansionist agenda. Indeed, many early Tamil hymns also invoke Nataraja as the dark lord wandering around cremation grounds. In a similar vein, it is no doubt pertinent to query the extent to which there really had been a ‘cosmic’ dimension associated with the actual visualization of the icon by its makers.

Nevertheless, this author would like to reiterate that the comment of Zvelebil (1985: 8 ) that Coomaraswamy had ‘…with tremendous intuition…foreseen the results of later research’ has a ring of truth in that the ‘cosmic’ dimensions that his writings hinted at, cannot be dismissed as being totally removed from the subtext of the conceptualization of this bronze. The author has thus argued that the dating of the Nataraja bronze to the Pallava period based on the technical finger-printing evidence (Srinivasan 2004), predating the Chola period, raises new possibilities of making connections with some of the mystical references to be found in the writings of Tamil poet saints from the 7th-9th century, suggesting a nascent ‘cosmic’ comprehension.

The temple of Chidambaram dated to the 12th-13th century, is the only shrine where the Nataraja metal icon of dancing Siva is worshipped in the inner sanctum or garbhagriha in place of the aniconic lingam or cosmic pillar (Younger 1995). In all other Siva temples elsewhere in Tamil Nadu, metal Nataraja icons are only processional images for festivals or the utsava murti. Within the Chidambaram temple, the Nataraja image is worshipped inside the golden roofed structure called the ‘chit sabha’, i.e. ‘hall of consciousness’. Exploring the etymology of the word Chidambaram itself, one of its meanings could be as follows: chit translates as the consciousness and ambaram the cosmos, so in that sense Chidambaram itself could signify the cosmic consciousness. In a hymn to Nataraja ‘Kunchitanghrim bhaje’ composed by the 13th Tamil poet Umapati Sivacarya of Chidambaram (Smith 1998: 21), Siva as Nataraja performs theanandatandava or dance of bliss and is also described as sacchidananda or the one whose mind or consciousness is in a state of the dance of blissful equilibrium. The ‘Chidambaram Rahasya’ or secret of Chidambaram relates to the worship of Nataraja also in the form of ‘akasa’ or the element sky or ether. Sivaramamurti (1974: 147) mentions that the Sanskrit Vadnagar Prasasti of Kumarapala describes Siva as playing with crystal balls as if they were newly created planets.

At the same time, there are already references in the pre-Sanskritic poetic corpus of devotional poetry to Nataraja worshipped at Tillai (the old name for Chidambaram) by Tamil saints such as Manikavachakar and Appar using the Tamil words of ‘unarve’ (consciousness) and ‘nilavu’ (sky). This suggests that such ‘abstract’ notions need not have been later Sanskritised introductions but could have also formed a part of the general ways in the icon was understood in this earlier period from about the 7th-9th century when so much of the Tamil devotional poetry related to the icon was actually compiled.

For example, a verse by Manikavachakar goes, ‘He who creates, protects, and destroys the verdant world…’ (Mowry 1983: 53). Another verse by Manikavachakar cited in Yocum (1983: 20) describes Nataraja as ‘Him who is fire, water, wind, earth and ether’. Yet another 9th century verse by Manikkavachakar (Yocum 1983: 24) cited below already suggests a mystical comprehension of the Nataraja bronze in terms of ‘consciousness’ as suggested by the Tamil word (unarve), preceding the use of the Sanskritic term chit as consciousness.:

O unique consciousness (or unarve),

which is realised (unarvatu) as standing firm,

transcending words and (ordinary) consciousness (unarvu),

O let me know a way to tell of You. (22:3)

A ‘cosmic’ sense of nature mysticism also permeates a Tamil verse to Nataraja composed by the 7th century saint Appar (Handelman and Shulman 2004), referring to sky as the Tamil ‘nilavu’, prior to 12th-13th century usage of the Sanskrit ‘akasa’:

The Lord of the Little Chamber,

filled with honey,

will fill me with sky (nilavu)

and make me be. [5.1.5]

In Srinivasan (2011) the author has also suggested that this ‘cosmic’ sensibility may also hark back to the nature imagery that pervades the earlier classical Tamil Sangam poetic tradition with its sense of traversing from the inner space (akam) to the outer space (puram). This sensibility is captured in A.K. Ramanujan’s fine commentaries on early Sangam poetry, himself an exceptional scholar-literateur who in this author’s opinion evokes something of the linguistic finesse of Coomarasamy’s academic prose. For example, the following verse from A. K. Ramanujan’s translation (1980: 108-9) conveys the creative tension generated by the juxtaposition of akamwith puram genres, of outer with inner space:

‘Bigger than earth, certainly,

higher than the sky,

more unfathomable than the waters

is this love for this man…’

In this context too, Coomaraswamy’s writings pointing to such ‘cosmic’ elements have resonance, such as the following verse he sites from Tirukuttu Darsharna (‘Vision of the sacred dance’) from Tirumular’s Tirumantiram, ‘He dances with water, fire, wind and ether, his body is Akash, the dark cloud therein is Muyalaka (the dwarf demon below Siva’s foot)’. Dates for Tirumular vary from the 8th century to as late as the 11th-12th century.

Finally, the author would also like to allude to preliminary archaeoastronomical studies made by her with late astrophysicist Nirupama Raghavan which point to the connections of the Nataraja imagery with the star positions in and around the Orion constellation and the possible inspiration also drawn in aspects of Nataraja worship from a postulated sighting of the 1054 supernova explosion (Srinivasan 2006). Although these are preliminary findings, there is some tentative evidence in the worship of the Nataraja in a chariot processional festival Chidambaram in the month of Margazhi around December known as Tiruvadurai. The ardra tandava darshanam at Chidambaram is related to the sighting of ardra or the reddish star Betelguese in the constellation Orion who is associated with Nataraja. The constellation of Orion appears at the zenith at this time of the year and as witnessed also by the author, some of the star positions and Orion seem to broadly correlate with some of the body parts of Siva Nataraja, for example the Orion belt falls along his belt and the lifted leg pointing towards Syrius. A Tamil text by A. Cokkalinkam identified by the late Raja Deekshitar (pers. comm.) of Chidambaram showed some of the star positions of Orion around the Nataraja bronze entitled ‘ardra tandava darsanam’. This implies the sighting of the tandava dance performed by Shiva Nataraja as ardra or arudra, the wrathful one, hence associated with the reddish star Betelguese.

Conclusion

The above paper summarises some of the new trends or insights that art historical studies combined with archaeometallurgical, ethnoarchaeological, crafts documentation and archaeoastronomical studies yields in terms of an understanding of the enigmatic Nataraja bronze and the milieu of south Indian and South Asian bronzes. The ground breaking legacy of Coomaraswamy in contributing to this overall understanding is highlighted.

(This article was earlier published in Asian Art and Culture: A Research Volume in Honour of Ananda Coomaraswamy, Kelaniya: Centre for Asian Studies, pp. 245-256)

(Professor Sharada Srinivasan, of the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, works in the areas of archaeological sciences, archaeometallurgy, art history and performance studies. A PhD in archaeometallurgy, Institute of Archaeology, University College, London, she is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain, and the World Academy of Art and Science. As an exponent of Bharatanatyam she has given several lecture-demonstrations including one at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, for their exhibition ‘Chola: Sacred Bronzes from Southern India’ (2007))

References

Balasubrahmanyam, S. R. 1971. Early Chola temples Parantaka I to Rajaraja I (A.D. 907-985). New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Bennink L.P., K. Deekshitar, J. Deekshitar, and Sankar Deekshitar, 2012, ‘Shiva’s Dance in Stone: Ananda Tandava, Bhujangalalita, Bhujangatrasita’,http://www.asianart.com/articles/shivadance/pop1.html

Capra, F. 1976. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. London: Fontana, p. 258.

Coomaraswamy, A. K., 1909, The Indian craftsmen, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Coomaraswamy, A.K. 1956. Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. New York.

Dehejia, V. 1990. Art of the Imperial Cholas. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gangoly, O.C., 1978, South Indian Bronzes, Calcutta.

Glansdorff, A. and Prigogine, I. 1971. Thermodynamic theory of structure, stability and fluctuations. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Handelman, D. and Shulman, D. 2004. Siva in the Forest of Pines: An Essay on Sorcery and Self-Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaimal, P. 1999. Shiva Nataraja: Shifting meanings of an icon, Art Bulletin, Vol. LXXXI, 3, 390-420.

Mowry, L. “The theory of the phenomenal world in Manikkavachakar’s Tiruvachakam”. In: Clothey, F. and Long. B. (eds.). Experiencing Siva: Encounters with a Hindu Deity. New Delhi: Manohar Publications, pp. 37-59.

Oldmeadow, H. 2004, Journeys East: 20th century western encounters with eastern religious traditions, Bloomington: World Wisdom.

Parker, S. 1992. The matter of value inside and out: aesthetic categories in contemporary Hindu temple arts. Ars Orientalis 22: 98-109.

Ramanujan, A.K. 1980, The Interior Landscape: Love poems from a classical Tamil Anthology, Clarion Books.

Rangarajan, A. 1992. ‘A confluence of East and West: Ananda Coomaraswamy’.

Reeves, R. 1962. Cire Perdue Casting in India. New Delhi: Crafts Museum.

Rodin, A, ‘La Danse de Siva’, Ars Asiatica, 3:7-13.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1963, South Indian Bronzes, New Delhi: Lalit Kala Academy.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1974. Nataraja in Art, Thought and Literature. New Delhi: National Museum

Smith, D. 1998. The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India. Cambridge: University Press

Srinivasan, S. 1996. The enigma of the dancing ‘pancha-loha’ (five-metalled) icons: archaeometallurgical and art historical investigations of south Indian bronzes. Unpublished Phd. Thesis. Institute of Archaeology, University of London.

Srinivasan, S. 1999. Lead isotope and trace element analysis in the study of over a hundred south Indian metal icons. Archaeometry 41(1).

Srinivasan, S. 2001. ‘Dating the Nataraja dance icon: Technical insights’. Marg-A Magazine of the Arts, 52(4): 54-69.

Srinivasan, S, 22 June 2003, ‘Heritage: The Nataraja catapulted onto the global stage from sacred environs’, The Week, Vol. 21, No. 29: 60-2. http://www.the-week.com/23jun22/life2.htm

Srinivasan, S. 2004. ‘Siva as cosmic dancer: On Pallava origins for the Nataraja bronze’. World Archaeology. Vol. 36(3): 432-450. Special Issue on ‘Archaeology of Hinduism.

Srinivasan, S. 2006. ‘Art and Science of Chola Bronzes’. Orientations, 37 (8): 46-55.

Srinivasan, S. and Ranganathan, S. 2006, ‘Nonferrous materials heritage of mankind,’ Transactions of Indian Institute of Metals, Vol. 59, 6, pp. 829-846.

Srinivasan, S. 2010, ‘Cosmic inspiration & art in relation to dancing Shiva Nataraja bronze’, Published abstract, INSAP VII, (Seventh international conference on inspiration from astronomical phenomena), Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution.

Srinivasan, S. 2011, ‘Nataraja and Cosmic Space: Nature and Culture intertwinings in the early Tamil tradition’, In Nature and Culture, ed. R. Narasimha, History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, PHISPC Series and Centre for Studies in Civilisation, pp. 271-291.

Von Schroeder, U. 1981. Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma.

Younger, P. 1995. ‘The Home of Dancing Sivan: Traditions of the Hindu Temple in Citamparam’, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 112.

Zvelebil, K., 1985, Ananda-Tandava of Siva-Sadanrttamurti, Institute of Asian Studies, Madras.

Benjamin W. Roberts, Christopher Thornton, 2014, Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Syntheses, Springer Science & Business Media

Hunt, LB, 1980, The long history of lost wax casting, Springer Science, pp.63-79

https://www.scribd.com/doc/267923381/Hunt-LB-1980-The-long-history-of-lost-wax-casting-Springer-Science-pp-63-79

Casting of bronze began in Southeast Asia first in northeastern Thailand (Bon Chiang). "In the words of one writer, 'bronze casting bean in Southeast Asia and was later borrowed by the Chinese, not vice versa as the Chinese scholars have always claimed' (Neher, p.186)...bronze-casting technology spread from Southeast Asia to China rather than from China to Southeast Asia, or, at least, developed independently in Southeast Asia and in China, then the Dong-son bronze technology probably developed from local or regional industries rather than from imported Chinese skills...Vietnamese archaeologists...have found that the earliest bronze drums of Dong-son are closely related in basic structural features and in decorative design to the pottery of the Phung-nguyen culture. They further suggest that the Dong-son culture of northern Vietnam had important links with Tibeto-Burman cultures in Yun-nan, with Thai cultures in Yun-nan and Laos, and, especially, with Mon-Khmer cultures in Laos, particularly oon the Tran-ninh plateau...or 'Plan of Jars', is the most natural route from northern Vietnam to northeastern Thailand. Aside from technical aspects, Dong-son culture was strongly influenced by seaborne contacts. The distinctive features and designs on the Dong-son drums are generally believed to 'express one phase of maritime art'. Boats filled with oarsmen and warriors surrounded by seabirds and other forms of maritime life unmistakably testify to the ascendancy of sea-based power." (Taylor, Keith W. (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. p. 313).

The first datings of the artifacts using the thermoluminescence technique resulted in a range from 4420 BCE to 3400 BCE which would make Ban Chiang the earliest Bronze Age culture in the world. Radiocarbon dates have revised the dates to ca. 2100 BCE of an early grave and bronze making is said to have begun ca. 2000 BCE as evidenced by crucibles and bronze fragments. The debate about the dates..."has focused on bronzes that were grave goods and has not addressed the non-burial metals and metal-related artefacts. This article summarizes the burial and non-burial contexts for early bronzes at Ban Chiang, based on the evidence recovered from excavations at the site in 1974 and 1975. New evidence, including previously unpublished AMS dates, is presented supporting the dating of early metallurgy at the site in the early second millennium B.C. (c. 2000-1700 B.C.). This dating is consistent with a source of bronze technology from outside the region. However, the earliest bronze is too old to have originated from the Shang dynasty, as some archaeologists have claimed. The confirmed dating of the earliest bronze at Ban Chiang facilitates more precise debate on the relationship between inter-regional interaction in the third and second millennia in Asia and the appearance of early metallurgy." -- EurASEAA 2006, Bougon papers ("White, J.C. 2008 Dating Early Bronze at Ban Chiang, Thailand. In From Homo erectus to the Living Traditions. Pautreau, J.-P.; Coupey, A.-S.; Zeitoun, V.; Rambault, E., editors. European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Chiang Mai, pp. 91-104.")

http://seasiabib.museum.upenn.edu:8001/pdf_articles/bookchapters/2008_White.pdf

"The Đông Sơn bronze drums exhibit the advanced techniques and the great skill in the lost-wax casting of large objects, the Co Loa drum would have required the smelting of between 1 and 7 tons of copper ore and the use of up to 10 large casting crucibles at one time." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%90%C3%B4ng_S%C6%A1n_culture

The bronze drum from Co Loa, weighs 159 pounds (72 kg) and would have required the smelting of between 1 and 7 tons of copper ore).

"The Dong Son civilization cast bronze primarily by two methods: “lost-wax” method and “puddle casting.” The first is much more common than second.THE LOST-WAX METHOD OF BRONZE CASTING

The Dong Son craftsmen did wonderful things with bronze. Most of what they created was produced by the “lost-wax method.” In this method, an original piece (sculpture, jewelry, bowl, weapon blade, etc.) was hand-made of paraffin or other wax. Additional wax tubes were added, which serve as exits for the wax and entrances for the bronze. The entire product was covered with clay, in layers of progressively thicker consistency. The only parts that protruded from the clay mass were the wax tubes. It looked much like a potato with a few candles sticking out. When heat was applied, the protruding wax rods melted first. As it melted, the remaining wax flowed out through the channels left in the clay by the melted tubes. The piece was then repositioned and molten bronze was poured into the channels. Ideally, the bronze then flowed into all the negative space that had once been occupied by the wax. At the same time, the air that had been in those spaces was forced out. For this to occur, the number and placement of the tubes was critical. If some air became trapped in small spaces (usually at the ends of narrow segments, such as a hand or finger), the bronze would not be able to enter that space. The final product, then, would “have no hand” (or whatever). After the bronze had hardened, the clay was then cracked and removed, leaving a bronze replica of the original wax piece, including the tubes. The next step was to remove the tubes, remove extra bits of bronze and polish the surface of the piece (this last is called chasing)." http://giahoithutrang.blogspot.in/2014/02/blog-post.html

Close-up view of a Dong Son bronze drum with hieroglyphs cast using lost-wax metallurgical techniques.

Replica of Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro

Replica of Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daroChhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, India. The statue was made using cire perdue method of metal casting

Trundholm sun chariot. Gilded side. Side with no traces of gilding. Dated to between 1800 to 1600 BCE. Copenhagen, Denmark National Museum. w54 × h35 × d29 cm (21 × 14 × 11 in)

Trundholm sun chariot. Gilded side. Side with no traces of gilding. Dated to between 1800 to 1600 BCE. Copenhagen, Denmark National Museum. w54 × h35 × d29 cm (21 × 14 × 11 in) Bronze statue. Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan Province ca 1200 BCE. 262 cm. tall.Sanxingdui Museum.

Bronze statue. Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan Province ca 1200 BCE. 262 cm. tall.Sanxingdui Museum.

Bronze Figurine, Dong Son Culture, 500 BCE East Asian Art Museum, Berlin.

Charioteer of Delphi, 570 BCE, Delphi Museum.

"The Sanskrit Shilpa Shastra texts mention the lost-wax process and call it the Madhucchishta Vidhana. The Chola dynasty from the mid-9th to the mid-13th century is renowned for the casting of bronze statues and produced some of India’s greatest bronzes, with the pinnacle reached during the first 120 years of this period, Chola period bronzes were created using the lost wax technique. The culture spread out through South-east Asia including Indonesia and had a lot of influence in the art of these regions." Nguyễn Thiên Thụ, Documents of Vietnamese ancient culture, 24 Feb. 2014

Shiva Nataraja, Chola dynasty 950 to 1000. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

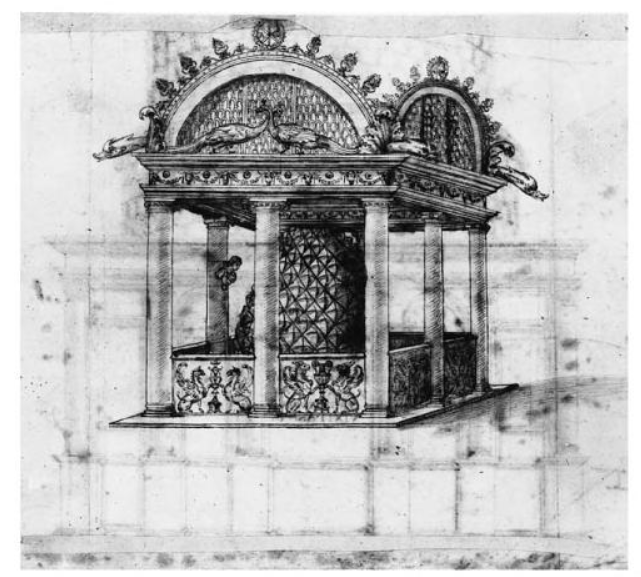

Water installation with bronze pine-cone in the atrium of Old St Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Drawing by Cronaca (1457-1505). Uffizi, Florence, 1572. This was a structure in front of the Temple of Isis, Pompeii.

Water installation with bronze pine-cone in the atrium of Old St Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Drawing by Cronaca (1457-1505). Uffizi, Florence, 1572. This was a structure in front of the Temple of Isis, Pompeii.[quote]“Bronze Pine Cone” signed Publius Cincius Salvio from the area of the Baths of Agrippa, maybe fountain in the Temple of Isis (Note: Possible location discussed in Annex A).

It was eventually placed in the atrium of the old Basilica of St. Peter.

It gave the name to the central neighborhood called Rione Pigna, where the Temple of Isis was originally located. [unquote]

The pine cone PLUS the pair of peacocks are likely to be originally from the Temple of Isis, Pompeii and relocated in the Baths of Agrippa and later in Basilica of St. Peter and now, Pine Cone is seen in Rione Pigna PLUS the pair of peacocks are kept in Braccio Nuovo Museum, Vatican. (Replicas flank the Pine Cone in Rione Pigna).

The Pine Cone and pair of peacocks are monumental bronze cire perdue castings and Vatican should organize for archaeometallurgical evalution of these superb specimens of Bronze Age artisanal competence clearly related to the times when Isis was venerated in Rome.

One of the original peacocks now in Braccacio Museum. Two bronze peacocks are from Hadrian’s Mausoleum (tomb).

mora peacock; morā ‘peafowl’ (Hindi); rebus: morakkhaka loha, a kind of copper, grouped with pisācaloha (Pali). [Perhaps an intimation of the color of the metal produced which shines like a peacock blue feather.] moraka "a kind of steel" (Samskritam)

1. Hieroglyph, signifier: kandə 'pine cone' Rebus, signified metalwork: khaṇḍa. A portion of the front hall, in a temple; kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Marathi)

2. Hieroglyph, signifier: mora, 'peacock' Rebus signified metalwork: morakkhaka loha, 'a kind of copper';moraka 'a kind of steel'.

Tōdai-ji Daibutsu, Nara, Japan. Statue of the Vairocana Buddha. The 15 metre high statue was made from eight castings over three years, the head and neck being cast separately. The casting of the statue was started in Shigaraki in 742, completed in Nara in 745 and finally finished in 751 weighing 500 tonnes.

Tōdai-ji Daibutsu, Nara, Japan. Statue of the Vairocana Buddha. The 15 metre high statue was made from eight castings over three years, the head and neck being cast separately. The casting of the statue was started in Shigaraki in 742, completed in Nara in 745 and finally finished in 751 weighing 500 tonnes.Source: http://giahoithutrang.blogspot.in/2014/02/blog-post.html

Mirror: http://apsara.transapex.com/history-bronze-casting/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROtGHT3A1sg Todaiji Home of the Great Buddha Tōdai-ji (東大寺 Tōdai-ji or Eastern Great Temple), is a Buddhist temple located in the city of Nara, Japan. Its Great Buddha Hall (大仏殿 Daibutsuden) is the largest wooden building in the world, and houses Japan's largest statue of the Buddha Vairocana, known in Japanese simply as Daibutsu (大仏) or Big Buddha.

The Buddha was completed in 751 but has been rebuilt over history. The present day buddha has parts from different periods, including the hands which were made in the Momoyama Period (15681615), and the head, which was made in Edo period (16151867).

Dimensions of the Daibutsu:

Height: 14.98 m (49.1 ft)

Face: 5.33 m (17.5 ft)

Eyes: 1.02 m (3.3 ft)

Nose: 0.5 m (1.6 ft)

Ears: 2.54 m (8.3 ft)

The statue weighs 500 metric tons (550 short tons)

Cire perdue. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjodaro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

Cire perdue. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjodaro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11) Cire perdue.

Cire perdue.ลายรูปนกยางหรือกระสา (Herons)? บนหน้ากลองมโหร Pattern or heron birds (Herons, storks)? On drums found at Co Lau, Hanoi in Vietnam was about 2,500 years ago (Dong Son Drum in Vietnam: 1990)

Bronze deity oil lamp, pre-1900

Bronze deity oil lamp, pre-1900Le bronze et les méthodes de coulées

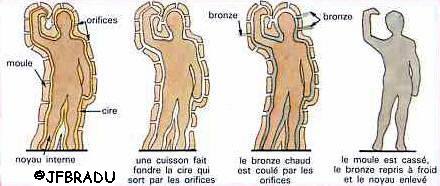

Le bronze est un alliage de cuivre et d'étain, il permet aux hommes de fabriquer des armes plus efficaces que celles en silex. L'étain vient d'Armorique ou de Grande Bretagne et le cuivre des Alpes ou d'Europe de l'est. D'importants courants d'échanges vont ainsi se constituer pour se procurer ces deux matières premières nécessaires à la fabrication du bronze. Outre les armes, le bronze va être utilisé pour fabriquer des outils (haches, marteaux, faux, enclumes, roues...) et des statuettes.

On peut fabriquer un objet en bronze de deux façons :

- soit en façonnant le métal par martelage : le métal est rougi dans une flamme pour le rendre plus malléable et le marteler sur l'enclume. Lorsque le métal durcit en se refroidissant il faut le remettre dans la forge pour pouvoir à nouveau le marteler jusqu'à obtenir la forme désirée.

- soit en coulant le bronze dans un moule (bronze coulé). Le moule, en argile, est en général fait de deux parties (2 valves) pour pouvoir extraire l'objet après refroidissement. Dans ce cas, on peut réutiliser le moule.

La technique "à la cire perdue" a été inventée par les Gaulois. Le modèle à reproduire est façonné en cire puis recouvert d'argile (le moule). Pendant la cuisson, la cire fond et s'échappe par des trous (évents) qu'on a aménagés. Le métal en fusion est alors versé dans le moule d'argile où il occupe la place laissée libre par la cire. Après refroidissement, on casse le moule d'argile pour extraire l'objet fondu. On ne peut donc couler qu'un seul exemplaire de chaque modèle avec cette technique. L'objet démoulé peut alors être repris pour le limer, le marteler, le recuire si nécessaire. Ensuite, on peut décorer l'objet en le gravant, le ciselant ou l'émaillant.

Pour les objets importants (grandes statues), afin d'éviter de grosses coulées de bronze, la forme n'est pas faite entièrement en cire mais d'abord en argile qui est, elle même, recouverte d'une couche de cire. La coulée de bronze va ainsi s'effectuer à la place de la cire, entre la forme en argile de l'objet et le moule en argile.

.Les Gaulois apprécient beaucoup le bronze car à l'état neuf il prend la couleur de l'or. Le bronze reste très utilisé à l'âge du fer pour fabriquer les fibules, les bracelets, les broches, les éléments de char. Les Gaulois pratiquent aussi l'étamage qui consiste à recouvrir un métal d'une couche d'étain pour empêcher l'oxydation.

Translation:

Bronze and methods flows

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, it allows men to make more effective weapons than flint. Tin comes Armorique or Great Britain and copper Alps or Eastern Europe. Major trade flows will thus be to procure these raw materials needed for the manufacture of bronze. Besides the weapons, the bronze going to be used for making tools (axes, hammers, fake, anvils, wheels ...) and statuettes.

You can produce a bronze object in two ways:

- Either by shaping the metal by hammering: the metal is flushed into a flame to make it more malleable and hammering on the anvil. When the metal hardens as it cools it must be viewed in the forge for hammering power again until the desired shape.

- Either by pouring the bronze into a mold (cast bronze). The mold, clay, is usually made of two parts (2 valves) to be able to extract the subject after cooling. In this case, the mold can be reused.

The technique "lost wax" was invented by the Gauls. The model to be reproduced is shaped wax then covered with clay (the mold). During cooking, the wax melts and escapes through holes (vents) that were set. The molten metal is then poured into the clay mold where it occupies the place left vacant by the wax. After cooling, the clay mold is broken to extract the molten object. One can not run a single copy of each model with this technique. The unmolded object can then be repeated for the file, the pound, the annealing if necessary. Then you can decorate the object by etching the chiseling or peppering.

For large objects (large statues), to avoid large cast bronze, the shape is not made entirely of wax but first clay which is, itself, covered with a layer of wax. The bronze casting will thus be carried out instead of wax, between the clay in the form of the object and the clay mold.

.The Gauls appreciative bronze because when new it takes the color of gold. The bronze is very used to the Iron Age to make brooches, bracelets, brooches, char elements. Gaul also practice the tinning which consists of covering a metal with a tin layer to prevent oxidation.

Technologie : La Cire Perdue version 3D Printing

Aujourd’hui, je vais vous expliquer une technique hybride pour faire des pièces métalliques grace à l’impression 3D. Cette méthode est la combinaison de l’impression 3D d’un modèle en cire, et la réalisation d’une pièce en bronze, en argent ou en or, via la coulée d’une pièce.

Technique de la cire perdue

La méthode de la cire perdue est une méthode qui permet le tirage d’un certain nombre de pièces sur base d’un même modèle. Cette technique se réalise en plusieurs étapes :

- la réalisation d’un moule en silicone basée sur le modèle

- la réalisation d’une ou plusieurs copies du modèle en cire

- la réalisation d’un moule en céramique (plâtre, céramiques spéciales, …) autour des modèles en cire auxquels ont a ajouté des alimentations et évents

- une fois la céramique solidifiée, on évacue les modèles en cire en chauffant les moules.

- le bronze est coulé dans le moule en céramique

- le moule en céramique est détruit

Présentation des étapes de réalisation d’une pièce en bronze dans un moule réalisé via la méthode de la cire perdue.

Présentation des étapes de réalisation d’une pièce en bronze dans un moule réalisé via la méthode de la cire perdue.Les avantages de cette technique sont nombreux. Tout d’abord, il est possible pour l’auteur de réaliser plusieurs multiples d’une pièce existante, ou de réaliser une pièce unique en modelant directement la cire. Ensuite, cette technique permet d’obtenir des pièces très détaillées.

Cette technique est la plus largement utilisée actuellement pour les pièces de taille moyenne à petite. En Afrique, le moule en céramique est remplacé par de la terre cuite et du crottin d’âne.

Et l’impression 3D dans tout ça ?

Plutôt que de partir d’un modèle et de faire un moule en silicone (ce qui impose pas mal de contraintes), il est désormais possible d’imprimer sur les imprimantes 3D directement la cire qui définit le modèle. Ensuite, on passe au moule en céramique et à l’injection de bronze.

Exemple en vidéo :

Impressionnant n’est-ce pas ?

Pleins de bijoux sont faits avec cette technologie que j’appelle "hybride" car elle utilise à la fois les avantages de l’impression 3D et les méthodes plus "ancestrales" !

Vous aimez l’impression 3D ? Vu que je suis désormais sur Twitter, je vous invite à me suivre, je partage beaucoup d’actualité sur ce sujet !

Translation:

Technology: The 3D version of Lost Wax Printing

Posted on 1 April 2014 by alicesalmon

The pieces in silver, gold and bronze are often performed by the technique of lost wax assisted by 3D printing.

The pieces in silver, gold and bronze are often performed by the technique of lost wax assisted by 3D printing.

Today, I'll explain a hybrid technique for making metal parts thanks to 3D printing. This method is the combination of 3D printing a wax model, and the realization of a bronze piece, silver or gold, via casting a piece.

Technique of lost wax

The lost wax method is a method that allows the drawing of a number of pieces based on the same model. This technique is done in several steps:

making a silicone mold based on the model

producing one or more copies of the wax pattern

the achievement of a ceramic mold (plaster, special ceramics, ...) around the wax patterns which have added power supplies and vents

once the solidified ceramic is discharged the wax models by heating the molds.

bronze is poured into the ceramic mold

the ceramic mold is destroyed

perduePrésentation wax casting steps in manufacturing of a bronze piece in a mold is made via the method of lost wax.

The advantages of this technique are numerous. First, it is possible for the author to make several multiples of an existing part, or make a single piece of direct modeling wax. Then, this technique allows to obtain very detailed pieces.

This technique is currently the most widely used for medium small pieces. In Africa, the ceramic mold is replaced with clay and donkey dung.

And 3D printing in?

Rather than from a template and make a silicone mold (which not require a lot of constraints), it is now possible to print directly on 3D printers wax that defines the model. Then they move on to the ceramic mold and bronze injection.

3D printing and Lost Wax / www.i.materialise.com

3D printing and Lost Wax / http://www.i.materialise.com

Example video:

Impressive is not it?

Full of jewelry is made with this technology that I call "hybrid" because it uses both the advantages of 3D printing and more "traditional" methods!

Like 3D printing? Since I'm now on Twitter, I invite you to follow me, I share a lot of news on it!

A Cire Perdue

A Cire Perdue is a bronze-making techniques beginning with the making of metal objects from wax, which contains clay as its core. candle shape is decorated with various ornamental patterns. form a complete candle wrapped again with the soft clay. at the top and bottom of a hole. from the hole above the liquid bronze is poured, and from the bottom hole of melted wax flows. when the bronze is poured cool,

the mold is broken down to pick up the finished object. Prints like these can only be used once only.

the mold is broken down to pick up the finished object. Prints like these can only be used once only.

*gaṭhati ʻ makes, forms ʼ. [√*gaṭh ] Pk. gaḍhaï ʻ forms ʼ; L. gaṛhāvaṇ ʻ to bring buffalocow to bull ʼ; P. gaṛhṇā ʻ to copulate with (of bull or buffalo) ʼ; A. gariba ʻ to mould, form ʼ; B.gaṛā ʻ to hammer into shape, form ʼ; Or. gaṛhibā ʻ to mould, build ʼ, gaṛhaṇa ʻ building ʼ; Mth. gaṛhāī ʻ wages for making gold or silver ornaments ʼ; OAw. gaḍhāi ʻ makes ʼ; H. gaṛhnā ʻ to form by hammering ʼ, G. gaḍhvũ. -- Altern. < gháṭatē : Wg. gaṛawun ʻ to form, produce ʼ; K. garun, vill.gaḍun ʻ to hammer into shape, forge, put together (CDIAL 3966)

H. gāṛhnā ʻ to form by hammering ʼ.

ʼ.

*gaḍḍa1 ʻ hole, pit ʼ. [G. < *garda -- ? -- Cf. *gaḍḍ -- 1 and list s.v. kartá -- 1 ]

Pk. gaḍḍa -- m. ʻ hole ʼ; WPah. bhal. cur. gaḍḍ f., paṅ. gaḍḍṛī, pāḍ. gaḍōṛ ʻ river, stream ʼ; N. gaṛ -- tir ʻ bank of a river ʼ; A. gārā ʻ deep hole ʼ; B.gāṛ, °ṛā ʻ hollow, pit ʼ; Or. gāṛa ʻ hole, cave ʼ, gāṛiā ʻ pond ʼ; Mth. gāṛi ʻ piercing ʼ; H. gāṛā m. ʻ hole ʼ; G. garāḍ, °ḍɔ m. ʻ pit, ditch ʼ (< *graḍḍa -- < *garda -- ?); Si. gaḍaya ʻ ditch ʼ. -- Cf. S. giḍ̠i f. ʻ hole in the ground for fire during Muharram ʼ. -- Xkhānĭ̄ -- : K. gān m. ʻ underground room ʼ; S. (LM 323) gāṇ f. ʻ mine, hole for keeping water ʼ; L. gāṇ m. ʻ small embanked field within a field to keep water in ʼ; G. gāṇ f. ʻ mine, cellar ʼ; M. gāṇ f. ʻ cavity containing water on a raised piece of land ʼ (LM 323 < gáhana -- ). WPah.kṭg. gāṛ ʻ hole (e.g. after a knot in wood) ʼ.(CDIAL 3981)

Pk. gaḍḍa -- m. ʻ hole ʼ; WPah. bhal. cur. gaḍḍ f., paṅ. gaḍḍṛī, pāḍ. gaḍōṛ ʻ river, stream ʼ; N. gaṛ -- tir ʻ bank of a river ʼ; A. gārā ʻ deep hole ʼ; B.gāṛ, °ṛā ʻ hollow, pit ʼ; Or. gāṛa ʻ hole, cave ʼ, gāṛiā ʻ pond ʼ; Mth. gāṛi ʻ piercing ʼ; H. gāṛā m. ʻ hole ʼ; G. garāḍ, °ḍɔ m. ʻ pit, ditch ʼ (< *graḍḍa -- < *garda -- ?); Si. gaḍaya ʻ ditch ʼ. -- Cf. S. giḍ̠i f. ʻ hole in the ground for fire during Muharram ʼ. -- X

Pa. gaḷa -- m. ʻ a drop ʼ, gaḷāgalaṁ gacchati ʻ goes from fall to fall ʼ; S. g̠aṛo m. ʻ hail ʼ, L. (Ju.) g̠aṛā m., P. gaṛā m. (cf. galā <

*gadda2 ʻ spotted, mottled ʼ. 2. *gaddara -- .L. gadrā ʻ piebald, spotted, leprous ʼ(CDIAL 4012)

Archaeometallurgy of cire perdue (lost-wax) metal castings links Ancient Near East and Ancient Far East

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/archaeometallurgy-of-cire-perdue-lost.htmlIn reconstructing proto-history, hieroglyphs, cultural metaphors and artistic expressions intersect. This is evident in the expansion of cire perdue (lost-wax) casting of metal alloys practised by Dhokra kamar of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. The gloss dhokra kamar 'cire perdue caster of metal alloys' is attested in Indus Script corpora.

The unique arhaeometallurgical method of casting exquisite arsenical and tin-bronze artifacts holds the key to evaluate links between the Ancient Far East and Ancient Near East during the early Bronze Age.

Evaluating bronze age metalwork exemplified by 'Ram in the Thicket' and 'Maikop gold bull' and placing the art works in the context of a universal art idiom -- across time and space --, Editors, Neil Collins and Áine Ni Muireadhaigh present a veritable Encyclopaedia of Visual Arts. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/site/about.htm In the context of this universal art idiom, it is apposite to trace the roots of Dian Bronze Art, starting with an evaluation presented by TzeHuey Chiou-Peng. In an archaeometallurgical framework, Dian culture is dated to ca. 4th century BCE and located not far from the famed Dong Son culture famed for the bronze drums of Ancient Vietnam which were cast using thecire perdue (lost-wax) method.

I suggest that the art idiom of Dian culture (Yunnan) and Dong Son culture (Vietnam) are a Meluhha metalwork hieroglyph continuum. The hieroglyphs used such as humped bull, tiger, multi-pointed star (sun), rhinoceros are read rebus, related to Meluhha metalwork, with particular reference to tin-bronzes which were produced in the world's larges Tin Belt of the Far East (Vietnam-Thai-Malay Peninsula). This indicates that Meluhha speakers from the Indiansprachbund had established a Trans-Asiatic network to spread 1) cire perdue (lost-wax) casting methods and 2) tin-bronzes as the contributory material resources which made the Bronze Age revolution possible in an extended Eurasian zone extending from Hanoi to Haifa. These are evidenced by the metaphors of Nahal Mishmar cire perdue metal castings (using arsenical copper) and by the presence of Indus writing on pure tin ingots discovered in a shipwreck at Haifa.

Risley defines 'Dhokra' as: "A sub-caste of kamars or blacksmiths in Western Bengal, who make brass idols." (Risley, HH ,1891, The Tribes and Castes of Bengal. Government of Bengal, Calcutta Vol. 1, p. 236)

Meluhha metallurgy to Bronze Age civilizations

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet with Meluhha hieroglyhphs written on two sides.

Some readings: