An inscription upon Pompeii’s Temple of Isis, built in the second century B.C. and rebuilt following the 62 A.D. earthquake, reads (translated), “Numerius Popidius Celsinus, son of Numerius, rebuilt at his own expense from its foundations, the Temple of Isis, which had collapsed in an earthquake; because of his generosity, although he was only six years old, the town councilors nominated him into their number free of charge” (ILS 6367 2004). Pompeiians valued this civil project so greatly that they rewarded the supposedly-donating six-year-old boy, with council membership. Because this temple served the Isis cult and was not a public civil space, the Temple of Isis, or Iseum, and Isis herself must have held special meaning and value for the city of Pompeii. Pompeii’s seafaring economy and the rise of personal religion in the Roman world may explain this high value. Since Pompeii relied on commercial seafaring to support its economy, Isis’s emphasis on stable and life-giving water defeating the often treacherous, unpredictable, and sometimes-deadly water of the sea, strengthened the local cult. The confluence of architecture, art, and rituals implies why the Pompeiians so highly valued a cult sanctuary – gentle Isis, offering resurrection and regulated water, provided a comforting counterbalance to unpredictable Neptune.

Pompeii’s vital location for maritime trade established the sea’s importance in the city (Strabo 5.4.8). To the Pompeiians, a navigable sea ensured economic prosperity and the city’s survival. Its status as a port gave Pompeii economic stability and power in its surrounding area, and thus both a reliance on, and fear of, the sea naturally followed (Ling 2005, 19). They would therefore have welcomed anything controlling the sea’s power. Coupled with the rise of personal religion and mystery cults (Small 2007, 200), this combination of respect for, and fear of the sea, may have led the Pompeiians to an increased appreciation of the cult of Isis and its rituals. The publicity of its popular festivals, especially that of the Navigium Isidis, must have kept Pompeiians consistently aware of the cult and of its protective goddess. Living under the fear of Neptune, the powerful and unpredictable god of the sea, many Pompeiians turned to the gentle Isis, who offered protection in sailing, navigable seas, and an abundant life and afterlife in exchange for personal devotion (Donalson 2003, 19).

Click to enlarge

Figure 1. The Iseum at Pompeii, ground plan. Star is author’s to mark location of Nilometer building and crypt (after Wild 1981, 45).

The Navigium Isidis ritually marked the opening of the sailing season (Arney 2011, 46). Apuleius in his Metamorphosis describes a showy public processional, which, although set in Egypt, illustrates important elements of the cultic ritual and suggests how it may have appeared in Pompeii (Griffiths 1975, 5). The parade opened with comedic, theatrical-like characters followed by cult adherents and priests, the most important in the rear holding the sacred pitcher (Apuleius 1975, 79, 81, 83, 85). A trade ship, staffed with a carefully selected crew and loaded with trade goods, formed the central part of the ritual procession (Apuleius 1975, 89, 91). Despite not being the most important part of the festival, the procession was heavily attended (Griffiths 1975, 32). To the Pompeiians, the trade ship’s safety promised their annual prosperity and survival (Donalson 2003, 69). Non-initiate observers noticed the portrayal of Isis as a guide and protectress of sailors, and the safe sailing of the sacred ship and its crew ensured their confidence in the sea’s navigability. The ship, built to sail, trade, and return, offered not a ritual sacrifice to the sea, but a powerful assurance of the trade routes’ safety (Griffiths 1975, 46–47). Gentle Isis, guardian of sailors and navigable seas, bestowed continued life to the Pompeiians through safe seafaring, an assurance the state-cult Neptune, associated with sometimes stormy and unpredictable oceans, could not provide.

The cultic association of Isis with water is firmly entrenched in the Pompeiian Temple of Isis itself. Perhaps the most prominent example of water associations with the cult is the Nilometer. This simple structure housed the ritual re-creation of the Nile flood (Wild 1981, 28). Rainwater, sacred to both Pompeiians and Egyptians for its rarity (Wild 1981, 64), replaced Nile water in Iseums outside of Egypt (Wild 1981, 65). Just as the Nile flood assured Egypt’s agricultural survival, the ritual “flood” in the Nilometer symbolized the abundant life-giving waters for agriculture in the Bay of Naples (Arney 2011, 56). In addition to the ceremonial flood recreation, the collected rainwater was used in other ritual practices. Priests manually removed this water, collected in a drainless basin (Wild 1981, 47). They then carried it in a sacred cultic pitcher, an important image in the later cult and in paintings on the temple’s walls (Wild 1981, 44, 101), and used it for libation rituals, including the morning unveiling of the cultic image (Apuleius 1975, 93). At its core, the Isis cult at Pompeii celebrated its deity of life-giving waters through their collection in the Nilometer and use in sacred rituals.

Click to enlarge

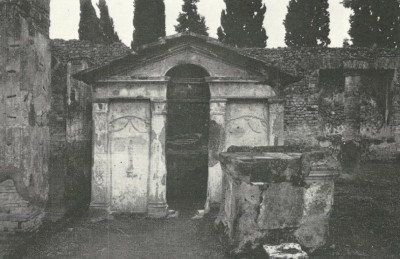

Figure 2. The Pompeiian Nilometer (after Wild 1981, Plate V.2).

The Nilometer’s design, decoration, and location convey information about its function and symbolic importance. It is in the southeastern part of the courtyard, with its entrance to the lower crypt, containing the water basin, in the southeastern corner of the structure (Figures 1 and 2) (Wild 1981, 44, 46). Since the Nile is southeast of Pompeii, this orientation connects the structure to the Nile itself, enhancing its symbolic importance. The crypt’s interior was simple yet functional. A wooden door led into a mini-vestibule, from which the entrant descended a narrow staircase. The vaulted entrance to the lower room, containing the rainwater collection basin, had a small platform structure to the right of the doorway. From here, the entrant viewed the room containing the 0.85 x 1.5 m basin that could hold 0.83 m3 water (Wild 1981, 46). This contained space conveyed mystique, a sense reoccurring throughout the architecture and rituals of the mystery cult (Arney 2011, 76). With life-giving waters at its core, the Nilometer formed a crucial center to the ritual practices of the Temple of Isis. Yet, despite its clear importance, any functions beyond the flood recreation are uncertain (Wild 1981, 51). Robert Wild has noted that ablution basins were found above ground, so the ritual occurring in the Nilometer, if any, must have been a special purification, possibly for initiates (Wild 1981, 51). During his initiation, Apuleius describes first being ritually cleansed with water and later experiencing “the boundary of death,” from which the resurrection powers of Isis save him (Apuleius 1975, 99). Regina Salditt-Trappmann, according to Wild, suggests that this may have been a ritual “drowning” in the Nilometer, an interpretation she supports by noting that the water poured in from above the basin (Wild 1981, 52).

Click to enlarge

Figure 3. Detail of the Pompeiian Nilometer's exterior: the sacred pitcher (Wild 1981, Plate VI.1).

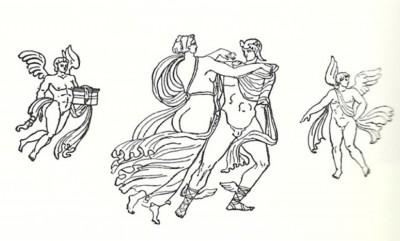

The Iseum’s decoration also emphasises water and the sea. Prominent ornamentation above the Nilometer entrance honours the sacred pitcher, figures surrounding it, and drawing attention to the important symbol (Figure 3). The sacred pitcher later replaced the Nilometer as a symbol of sacred water; at Pompeii, their juxtaposition provides insights into this transition (Wild 1981, 156). Other figures, Egyptian gods and adoring humans, interact with symbols of bountiful nature and sacred instruments of the Isis cult (Moorman 2005, 151–153). Their location in the Nilometer illustrates the connection between Isis, water, and abundance of life (Arney 2011, 66; Wild 1981, 125-126). Amongst the Egyptian symbols and decoration however, are Roman myths, such as Perseus and Andromeda (Figure 4). The inclusion of these myths suggests Pompeiian influences upon the local Isis cult. Symbolically, in the myth of Perseus and Andromeda, “when Perseus undertakes his fight against the monster, he is in actuality attacking the fundamental ruling forces of the sea,” the forces that would have been represented by the Roman cult god Neptune (Wild 1981, 81). Commemorating Perseus’s victory, in conjunction with the rising life-waters of the basin, conveyed to cult initiates that “[o]nce again the sea had been conquered, once again the forces of life had triumphed over the powers of evil and death” (Wild 1981, 83). It also exemplifies some confluence of Roman ideology and state religion with this mystery cult. Further examples appear throughout the cult, specifically in the Navigium Isidis ritual, where the processional prayers resembled state vota, prayers for the empire (Donalson 2003, 69). A contrast between Isis and Neptune would naturally have followed from an identification of the Isis mystery cult with the Roman state religion.

Click to enlarge

Figure 4. Drawing of Perseus and Andromeda, based on the painting found on the Pompeiian Nilometer (Wild 1981, Plate VI.1).

Artwork elsewhere in the temple complex similarly illustrates connections between Isis and the sea. The portico contained elaborate images of sea monsters and naval battles, contrasted with the pious decoration of the sacred pitcher and white-dressed cult members, alluding to both the initiates and outsiders of the cult, and the power of Isis over the sea (Moorman 2005, 143; Arney 2011, 59–60). Images of boats in the portico may relate to Isis’s patronage of, and worship by, sea merchants (Moorman 2005, 150). This decoration conveys that worship of Isis grants naval traders and warriors success (Donalson 2003, 19).

Frescos in the ekklesiasterion, which both the general populace and the cult used, further unite Roman mythology to the Isis cult (Arney 2011, 61). They depict scenes from the myths of Io and Jupiter, alongside traditional Egyptian paintings of Osiris’s resurrection through Isis’s devotion and magic (Moorman 2005, 146; Arney 2011, 66). Together with the portico and Nilometer paintings, they illustrate “salvation through the powers of Isis and the life-giving properties of the waters of the Nile” for the initiate (Arney 2011, 66).

The connections made between Egyptian and Roman mythology suggest an intentional link between the two cultures and their mythology, which provides a foundation for the comparison between Isis and Neptune.

The cult of Isis in Pompeii provided the Pompeiians with something the state religion could not: a personal protectress who offered life through water. With its trading economy, the sea was a foundation of Pompeiian life, and the assured success of the sea traders allowed the city to survive. As the Roman world shifted from public, imperial religion to private, personal cults, the focus of the Isis cult on controlled water, providing abundant life and navigable seas, appealed to the Pompeiian people. Public displays of the goddess’s power, such as the Navigidium Isidis festival, aided the Pompeiians’ formation of a strong connection between successful sailing and the worship of this mysterious, life-giving Egyptian goddess. The Iseum’s wall decorations likewise illustrate this relationship. This firmly entrenched correlation in the Pompeiian perception between this particular cult and the success of their sea-based economy may help explain the eagerness of the council to reward a six-year-old boy for the rebuilding of a mystery cult’s temple.

Bibliography

- Apuleius of Madauros. (1975). The Isis-book (Metamorphoses, book XI). Translated and edited by J. G. Griffiths. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Arney, J.K. (2011). Expecting epiphany: performative ritual and Roman cultural space. Unpublished: University of Texas at Austin. M.A.

- Donalson, M.D. (2003). The cult of Isis in the Roman Empire. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellon Press

- ILS 6367. (2004). Translated from the Latin by Cooley, A.E. and Cooley, M.G.L. (eds.) Pompeii: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge.

- Griffiths, J.G. (1975). ‘Introduction’, in Griffiths, J.G. (ed.) The Isis-book (Metamorphoses, book XI). Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Ling, R. (2005). Pompeii: history, life & afterlife. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

- Moorman, E.M. (2005). ‘The temple of Isis at Pompeii’, in Bricault, L., Versluys, M.J. and Meyboom, P.G.P (eds.). Nile into Tiber; Egypt in the Roman World; Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Isis Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 137-155.

- Small, A.M. (2007). ‘Urban, suburban, and rural religion in the Roman period’ in Dobbins, J.J. and Foss, P.W. (eds.) The world of Pompeii. New York: Routledge, pp. 184–211.

- Strabo. Geography 5.4.8. Pompeiana.org. [Online] Available at:http://www.pompeiana.org/Resources/Ancient/Strabo%20Geography%205.4.8.htm [Accessed 6 December 2012].

- Wild, R.A. (1981). Water in the cultic worship of Isis and Sarapis. Leiden: E.J. Brill

The Author

Inside of bracelet showing reverse of Julia Domna coin depicting Juno Regina with a peacock.

Inside of bracelet showing reverse of Julia Domna coin depicting Juno Regina with a peacock.