Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/12595279/Simorg_%C5%9By%C4%93n%C3%A1_anzu_patanga_m%C3%A1k%E1%B9%A3ik%C4%81_Rigveda_riddles_Meluhha_hieroglyphs_as_archaeometallurgy_metaphors

.jpg) A remarkable parallel is seen between rebus-metonymy layered cipher of Indus Script Corpora and riddles in the Rigveda. Indus Script Corpora is a compendium of metalwork catalogues. Rigveda riddles related to three birds are also rebus-metonymy layered riddles of archaeometallurgy involved in processing Soma, ams’u, ‘electrum’.

A remarkable parallel is seen between rebus-metonymy layered cipher of Indus Script Corpora and riddles in the Rigveda. Indus Script Corpora is a compendium of metalwork catalogues. Rigveda riddles related to three birds are also rebus-metonymy layered riddles of archaeometallurgy involved in processing Soma, ams’u, ‘electrum’.

“The mineral pyrite, or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula FeS2. This mineral's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue give it a superficial resemblance to gold, hence the well-known nickname of fool's gold. The color has also led to the nicknames brass, brazzle, and Brazil, primarily used to refer to pyrite found in coal.(Julia A. Jackson, James Mehl and Klaus Neuendorf, Glossary of Geology, American Geological Institute (2005) p. 82; Albert H. Fay, A Glossary of the Mining and Mineral Industry, United States Bureau of Mines (1920) pp. 103–104.) …The name pyrite is derived from the Greek πυρίτης (pyritēs), "of fire" or "in fire".. Pyrite is sometimes found in association with small quantities of gold. Gold and arsenic occur as a coupled substitution in the pyrite structure.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrite

See notes on speculative symbolism: Johnson, Willard, 1976, On the RG Vedic riddle of the two birds in the fig tree (RV 1.164.20-22), and the discovery of the Vedic speculative symposium, in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 96, No. 2 (Apr-Jun. 1976), pp. 248-258.

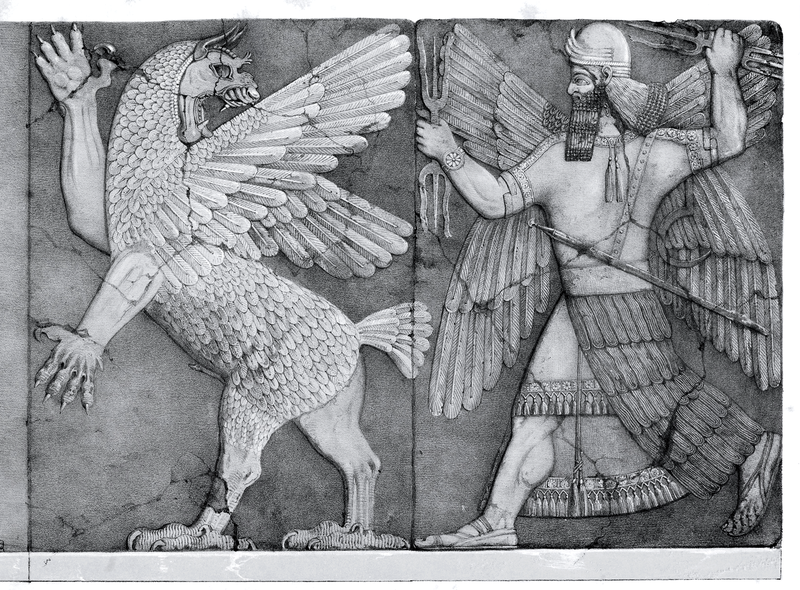

The imagery of the thunderstone or thunderbolt is linked to the metaphor of an eagle carrying away the tablets of destiny in Mesapotamian legends. This Anzu bird ligatured to a tiger is cognate Vedic śyēna. In Meluhha hieroglyphs, an abiding hieroglyph is that of a tiger. The tiger denotes a smithy, forge and smelter: kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'; kolhe 'smelters'; kolami 'smithy, forge'. The gloss Anzu is a rendering of Tocharian word Ancu, 'iron' (Rigveda ams'u, 'soma, electrum'):

Rishi: BrahmAtithih kANvah; devata: As'vinau; as'vikas'avah; cedyah kas'uh

यथोत कृत्व्ये धनेंशुम् गोष्वगस्त्यम् यथा वाजेषु सोभरिम् (RV 8.5.26)Trans. 8.005.26 And in like manner as (you protected) Ams'u when wealth was to be bestowed, and Agastya when his cattle (were to be recovered), and Sobhari when food (was to be supplied to him).

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/contributions-of-bharatam-janam-to.html Contributions of Bhāratam Janam to Archaeometallurgy: Reinterpreting Mayabheda Sukta of Rigveda (RV 10.177). This article includes a detailed unraveling of the riddles in Rigveda Sukta 1.164 as relatable to Pravargya by Jan EM Houben. (The ritual pragmatics of a Vedic hymn: The 'riddle hymn' and the Pravargya ritual by Jan EM Houben, 2000, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 120 (4), pp. 499-536.) Jan EM Houben indicates the possibility that the riddle in Rigveda Sukta 1.164 is explained as a metaphor of three birds, one of which is Suparna (garumat); the second a bird eating a sweet fig in a tree. The third bird is Patanga. The author of RV 10.177 is Rishi Patanga Prajapati and RV 10.177 is the same as RV 1.164.31. I suggest that the three birds in the Sukta RV 1.164 referred to by Houben are: śyēna, patanga, mākṣikā:

- śyēna is suprana (garutmat), falcon

- mākṣikā is the pippalam sva_du atti: 'the flying bee which eats the sweet fig' (RV 1.164.20)

- patanga is the third bird, flying insect (RV 10.177) The three flying birds (insects) are rebus-metonymy renderings as hieroglyphs signifying metalwork catalogues in archaeometallurgical transactions of Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk'

patanga, mercury or quicksilver in transmuting metal (Soma, ams'u);

mākṣikā, pyrites (which are to be oxidised to attain purified pavamAna Soma, electrum as gold-silver compound);

śyēna, anzu, ams'u (electrum ore filaments in the pyrites).

Three flying birds are abiding metaphors in Rigveda.

The glosses are: śyēna, patanga, mākṣikā. The three glosses are rebus-metonymy renderings of sena 'thunderbolt'; patanga 'mercury'; mākṣikā 'pyrites' -- three references to metalwork catalogs of Bhāratam Janam, 'lit. metalcaster folk'. A variant phonetic form of mākṣikā is makha 'fly, bee, swarm of bees' (Sindhi). The rebus-metonymy for this gloss is: makha 'the sun'. Mahavira pot is a symbol of Makha, the Sun (S'Br. 14.1.1.10).

In Vedic texts, Divinity Indra is lightning, his weapon is vajra, thunderbolt. The name "thunderbolt" or "thunderstone" -- vajrāśani (Ramayana) --has also been traditionally applied to the fossilised rostra of belemnoids. The origin of these bullet-shaped stones was not understood, and thus a mythological explanation of stones created where a lightning struck has arisen. (Vendetti, Jan (2006). "The Cephalopoda: Squids, octopuses, nautilus, and ammonites", UC Berkeley) In Malay and Sumatra they are used to sharpen the kris, are considered very lucky objects, and are credited with being touchstones for gold.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2015/05/contributions-of-bharatam-janam-to.html Contributions of Bhāratam Janam to Archaeometallurgy: Reinterpreting Mayabheda Sukta of Rigveda (RV 10.177) The metaphor of the 'thunderbolt' is depicted as Anzu bird [cognate:asaṇi 'thunderbolt' (Prakritam)] carrying away the tablets of destiny in Mesopotamian legends. A phonemic variant śyēna, 'falcon' gets deified, immortalised as a śyēnaciti 'falcon-shaped fire-altar' in Vedic tradition in Bharatam. This is mərəγō saēnō ‘the bird Saēna’ in Avestan. (See article on Simorg in Encyclopaedia Iranica, annexed. The cognate expression in Samskritam is śyēna mriga).

Bhāratam Janam, 'lit. metalcaster folk'

Hieroglyph: Ku. balad m. ʻ ox ʼ, gng. bald, N. (Tarai) barad, id. Rebus: L. bhāraṇ ʻ to spread or bring out from a kiln ʼ; M. bhārṇẽ, bhāḷṇẽ ʻ to make strong by charms (weapons, rice, water), enchant, fascinate (CDIAL 9463) Ash. barī ʻ blacksmith, artisan (CDIAL 9464).

Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) bharana id. (Bengali) bharan or toul was created by adding some brass or zinc into pure bronze. bharata = casting metals in moulds (Bengali) भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal भरत. 2 See भरिताचें भांडें.भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत.(Marathi. Molesworth)

पतं--ग m. or n. quicksilver L.

Ancient Greek tetradrachm coin from Akragas, 410 BCE, with a grasshopper on the right.

Ancient Greek tetradrachm coin from Akragas, 410 BCE, with a grasshopper on the right.पतं--ग [p= 581,1] mfn. flying RV. i , 118 , 4 any flying insect , a grasshopper , a bee , a butterfly or moth S3Br. (°त्/अंग) Up. Mn. &c ( -ता f.Prasannar. )

pataṅgá ʻ ep. of divine (flying) things ʼ RV., m. ʻ bird ʼ lex.; patáṅga -- m. ʻ (noxious) insect ʼ Br̥ĀrUp.; pataṅga<-> m. ʻ insect ʼ MBh., °gama -- m. BhP.,pataga -- m. MBh. (ʻ bird ʼ lex.). 2. *pattaṅga -- . 3. *paṭaṅga -- . 4. *paṭṭiṅga -- . 5. *phattiṅga -- . 6. *phaṭiṅga -- , phaḍiṅgā -- f. ʻ grasshopper ʼ lex. 7. *phaṭṭiṅga -- .[*patan<-> ʻ wing ʼ with suffix -- ga -- (EWA ii 198) X some nonAryan word. -- √pat] 1. Pk. payaṁga -- m. ʻ grasshopper ʼ. 2. Woṭ. patáṅg ʻ butterfly ʼ, Tor. (Biddulph) "pattang" m., Sv. pataṅg; H. patiṅgā m. ʻ grasshopper ʼ. 3. Pa. paṭaṅga -- m. ʻ grasshopper ʼ, Ku. pilaṅaṭ.4. Ku. piṭaṅo m. ʻ insect ʼ. 5. H. phatiṅgā m. ʻ grasshopper ʼ. 6. A. phariṅ ʻ any winged insect, grasshopper ʼ; B. phaṛiṅ ʻ winged insect ʼ, phaṛiṅgā ʻ cricket ʼ; Or. phaṛiṅga ʻ locust, cricket ʼ; H. phaṛiṅgā, phaṅgā m. ʻ grasshopper ʼ, Si.palan̆gā.7. N. phaṭeṅro ʻ grashopper ʼ; -- Dm. phaṭṭäi ʻ butterfly ʼ, Phal. phāṭuṛīˊ f. S.kcch. pataṅgh m. ʻ moth ʼ.(CDIAL 7721) So<pAp.pAr>//<pAr>(DL) {N} ``^grasshopper, ^locust''.

So<pAr>\\<pAp.pAr>(DL) {N} ``^grasshopper, ^locust''.<phapha>(D) {NI} ``a big green ^grasshopper''. #24801. (Munda etyma)

A tabanid from the Western Ghats, India. Hybomitra micans

Apis mellifera (Honeybee).

माक्षिकn. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

माक्षिक [p= 805,2]mfn. (fr. मक्षिका) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP.n. (scil. मधु) honey Var. Sus3r. mákṣā f., mákṣ -- m. f. ʻ fly ʼ RV., mákṣikā -- f. ʻ fly, bee ʼ RV., makṣika -- m. Mn.Pa. makkhikā -- f. ʻ fly ʼ, Pk. makkhiā -- f., macchī -- , °chiā -- f.; Gy. hung. makh ʻ fly ʼ, wel. makhī f., gr. makí f., pol. mačin, germ. mačlin, pal. mắki ʻ mosquito ʼ, măkīˊla ʻ sandfly ʼ, măkīˊli ʻ house -- fly ʼ; Ash. mačī˜ˊ ʻ bee ʼ; Paš.dar. mēček ʻ bee ʼ, weg. mečīˊk ʻ mosquito ʼ, ar. mučək, mučag ʻ fly ʼ; Mai. māc̣hī ʻ fly ʼ; Sh.gil. măṣīˊ f., (Lor.) m*lc̣ī ʻ fly ʼ (→ Ḍ. m*lc̣hi f.), gur. măc̣hīˊ ʻ fly ʼ (ʻ bee ʼ in gur. măc̣hi̯kraṇ, koh. măc̣hi -- gŭn ʻ beehive ʼ); K. mȧchi f. ʻ fly, bee, dark spot ʼ; S. makha, makhi f. ʻ fly, bee, swarm of bees, sight of gun ʼ, makho m. ʻ a kind of large fly ʼ; L. (Ju.) makhī f. ʻ fly ʼ, khet. makkīˊ; P. makkh f. ʻ horsefly, gnat, any stinging fly ʼ, m. ʻ flies ʼ, makkhī f. ʻ fly ʼ; WPah.rudh.makkhī ʻ bee ʼ, jaun. mākwā ʻ fly ʼ; Ku. mākho ʻ fly ʼ, gng. mã̄kh, N. mākho, A. mākhi, B. Or. māchi, Bi. māchī, Mth. māchī, mã̄chī, makhī (← H.?), Bhoj. māchī; OAw. mākhī, lakh. māchī ʻ fly ʼ, ma -- mākhī ʻ bee ʼ (mádhu -- ); H. māchī, mākhī, makkhī f. ʻ fly ʼ, makkhā m. ʻ large fly, gadfly ʼ; G. mākh, mākhī f. ʻ fly ʼ, mākhɔ m. ʻ large fly ʼ; M. mās f. ʻ swarm of flies ʼ, n. ʻ flies in general ʼ, māśī f. ʻ fly ʼ, Ko. māsu, māśi; Si. balu -- mäkka, st. -- mäki -- ʻ flea ʼ, mässa, st. mäsi -- ʻ fly ʼ; Md. mehi ʻ fly ʼ.S.kcch. makh f. ʻ fly ʼ; WPah.kṭg. mákkhɔ, máṅkhɔ m. ʻ fly, large fly ʼ, mákkhi (kc. makhe) f. ʻ fly, bee ʼ, máṅkhi f., J. mākhī f.pl., Garh. mākhi. (CDIAL 9696) *makṣātara ʻ rather like a fly or bee ʼ. [mákṣā -- ]Sh. (Lor.) m*lc̣hari ʻ wasp, hornet ʼ: more prob. same as m*lc̣hari ʻ bee ʼ < *mākṣikakara -- .(CDIAL 9699) *makṣikākula ʻ swarm of flies ʼ. [Cf. mākṣakulika -- . -- mákṣā -- , kúla -- ]P. makheāl m. ʻ beehive ʼ; Ku. makhyol ʻ swarm of flies ʼ.(CDIAL 9700) माशी (p. 649) [ māśī ] f (मक्षिका S) A fly मासूक (p. 649) [ māsūka ] n R (Commonly माशी) A fly. मधुमक्षिका (p. 629) [ madhumakṣikā ] f (S) pop. मधुमाशी f The honey-fly, a bee. मधुमक्षिकान्यायेंकरून (By the rule or law of the bees.) With selection, by picking and culling, by gathering from all quarters.(Marathi. Molesworth)

मखतूल [ makhatūla ] m Twisted silk.मकतूल [ makatūla ] m (Usually मखतूल) Twisted silk.

मख [ makha ] m (Commonly मोख) Kernel &c.

मखर [ makhara ] n A car or chair of state in which idols or Bráhmans are seated on great occasions and worshiped. 2 A gaily dressed up frame in which a girl under menstruation for the first time sits and receives certain honors.

मख 1 [p= 772,1] mfn. (prob. connected with √1. मह् or √ मंह्) jocund , cheerful , sprightly , vigorous , active , restless (said of the मरुत्s and other gods) RV. Br.m. a feast , festival , any occasion of joy or festivity RV. S3a1n3khGr2. m. a sacrifice , sacrificial oblation S3Br. &c ( Naigh. iii , 17)m. (prob.) N. of a mythical being (esp. in मखस्य शिरः , " मख's head ") RV. VS. S3Br. (cf. also comp.)

máhas2 n. ʻ delight in praise ʼ VS., ʻ festival, worship ʼ Pañcar., ʻ sacrifice ʼ lex., mahá -- m. ʻ festival, sacrifice ʼ MBh. [In later MIA. collides with makhá -- m. ʻ sacrifice ʼ ŚBr. -- √maṁh?]

Pa. maha -- n.m. ʻ festival ʼ; Pk. maha -- m. ʻ festival, sacrifice ʼ; OG. maha ʻ festival ʼ; Si. maha ʻ sacrifice ʼ. mahā -- in cmpds. ʻ great ʼ. [mah -- ] †indramaha (CDIAL 9937) máhas1 n. ʻ greatness, glory ʼ RV., ʻ splendour, light ʼ Inscr. [máh -- ] Pa. maha -- n.m. ʻ greatness ʼ; -- Si. maha ʻ light, brilliance ʼ (ES 66) ← Sk.? (CDIAL 9936)

Golden eagle.

<gOruDO>(P),,<gOruRO>(P) {N} ``^eagle, any big ^bird''. *Mu.<gaRur>, Ho<goruR>, H.<gArURA> `large species of heron, eagle', Sk.<gArUDA>. %11781. #11691.(Munda etyma) garuḍá m. ʻ a mythical bird ʼ Mn. Pa. garuḷa -- m., Pk. garuḍa -- , °ula -- m.; P. garaṛ m. ʻ the bird Ardea argala ʼ; N. garul ʻ eagle ʼ, Bhoj. gaṛur; OAw. garura ʻ blue jay ʼ; H. garuṛ m. ʻ hornbill ʼ, garul ʻ a large vulture ʼ; Si. guruḷā ʻ bird ʼ (kurullā infl. by Tam.?). -- Kal. rumb. gōrvḗlik ʻ kite ʼ?? (CDIAL 4041) gāruḍa ʻ relating to Garuḍa ʼ MBh., n. ʻ spell against poison ʼ lex. 2. ʻ emerald (used as an antidote) ʼ Kālid. [garuḍá -- ] 1. Pk. gāruḍa -- , °ula -- ʻ good as antidote to snakepoison ʼ, m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ, n. ʻ science of using such charms ʼ; H. gāṛrū, gārṛū m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ; M. gāruḍ n. ʻ juggling ʼ. 2. M. gāroḷā ʻ cat -- eyed, of the colour of cat's eyes ʼ.(CDIAL 4138)

G. garāḍ, °ḍɔ m. ʻ pit, ditch ʼ (< *graḍḍa -- < *garda -- ?);*gaḍḍa1 ʻ hole, pit ʼ. [G. < *garda -- ? -- Cf. *gaḍḍ -- 1 and list s.v. kartá -- 1] Pk. gaḍḍa -- m. ʻ hole ʼ; WPah. bhal. cur. gaḍḍ f., paṅ. gaḍḍṛī, pāḍ. gaḍōṛ ʻ river, stream ʼ; N. gaṛ -- tir ʻ bank of a river ʼ; A. gārā ʻ deep hole ʼ; B. gāṛ, °ṛā ʻ hollow, pit ʼ; Or.gāṛa ʻ hole, cave ʼ, gāṛiā ʻ pond ʼ; Mth. gāṛi ʻ piercing ʼ; H. gāṛā m. ʻ hole ʼ; Si. gaḍaya ʻ ditch ʼ. -- Cf. S. giḍ̠i f. ʻ hole in the ground for fire during Muharram ʼ. -- X khānĭ̄ -- : K. gān m. ʻ underground room ʼ; S. (LM 323) gāṇ f. ʻ mine, hole for keeping water ʼ; L. gāṇ m. ʻ small embanked field within a field to keep water in ʼ; G. gāṇ f. ʻ mine, cellar ʼ; M. gāṇ f. ʻ cavity containing water on a raised piece of land ʼ (LM 323 < gáhana -- ).WPah.kṭg. gāṛ ʻ hole (e.g. after a knot in wood) ʼ.(CDIAL 3981)

Pa. cēna frost, ice. Kuwi (Mah.) hennā hoar-frost. (DEDR 2823)

Si. sena, heṇa ʻ thunderbolt ʼ; aśáni f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ RV., °nī -- f. ŚBr. [Cf. áśan -- m. ʻ sling -- stone ʼ RV.]Pa. asanī -- f. ʻ thunderbolt, lightning ʼ, asana -- n. ʻ stone ʼ; Pk. asaṇi -- m.f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ; Ash. ašĩˊ ʻ hail ʼ, Wg. ašē˜ˊ, Pr. īšĩ, Bashg. "azhir", Dm. ašin, Paš. ášen, Shum.äˊšin, Gaw. išín, Bshk. ašun, Savi išin, Phal. ã̄šun, L. (Jukes) ahin, awāṇ. &circmacrepsilon;n (both with n, not ṇ), P. āhiṇ, f., āhaṇ, aihaṇ m.f., WPah. bhad. ã̄ṇ, bhal. ´tildemacrepsilon; hiṇi f., N. asino, pl. °nā; Si. sena, heṇa ʻ thunderbolt ʼ Geiger GS 34, but the expected form would be *ā̤n; -- Sh. aĩyĕˊr f. ʻ hail ʼ (X ?). -- For ʻ stone ʼ > ʻ hailstone ʼ cf. upala -- and A. xil s.v. śilāˊ -- Sh. aĩyĕˊr (Lor. aĩyār → Bur. *lhyer ʻ hail ʼ BurLg iii 17) poss. < *aśari -- from heteroclite n/r stem (cf. áśman -- : aśmará -- ʻ made of stone ʼ).(CDIAL 910) vajrāśani m. ʻ Indra's thunderbolt ʼ R. [vájra -- , aśáni -- ]Aw. bajāsani m. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ prob. ← Sk. (CDIAL 11207)

श्येन firewood laid in the shape of an eagle S3ulbas

श्येना f. a female hawk L. श्येन [p= 1095,2] m. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man) RV. &c mfn. eagle-like AitBr. mfn. coming from an eagle (as " eagle's flesh ") , Kr2ishn2aj. ?? (prob. w.r. for श्यैन). śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ. (CDIAL 12674) शेन [ śēna ] m (श्येन S) A hawk. शेनी f (श्येनी S) A female hawk.श्येन [ śyēna ] m S A hawk. श्येनी f S A female hawk. (Marathi)

Alabaster votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, showing Anzû as a lion-headed eagle, ca. 2550–2500 BC; found at Tell Telloh the ancient city of Girsu, (Louvre)

Ninurta with his thunderbolts pursues Anzû stealing the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil's sanctuary (Austen Henry Layard Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853)

śyena, orthography, Sasanian iconography. Continued use of Indus Script hieroglyphs.

Syena-citi: A Monument of Uttarkashi Distt.

EXCAVATED SITE -PUROLA

Geo-Coordinates-Lat. 30° 52’54” N Long. 77° 05’33” E

Notification No& Date;2742/-/16-09/1996

The ancient site at Purola is located on the left bank of river Kamal. The excavation yielded the remains of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) from the earliest level alongwith other associated materials include terracotta figurines, beads, potter-stamp, the dental and femur portions of domesticated horse (Equas Cabalus Linn). The most important finding from the site is a brick alter identified as Syenachiti by the excavator. The structure is in the shape of a flying eagle Garuda, head facing east with outstretched wings. In the center of the structure is the chiti is a square chamber yielded remains of pottery assignable to circa first century B.C. to second century AD. In addition copper coin of Kuninda and other material i.e. ash, bone pieces etc and a thin gold leaf impressed with a human figure tentatively identified as Agni have also been recovered from the central chamber.

Note: Many ancient metallic coins (called Kuninda copper coins) were discovered at Purola. cf. Devendra Handa, 2007, Tribal coins of ancient India, ISBN: 8173053170, Aryan Books International.

Kuninda

"In the Visnu Purana, the domain of Kunindas is especially defined as the Kulindopatyaka, i.e., the bounding foothills demarcating the Kuninda territory (NSWH, p. 71)...According to Ptolemy (McCrindle's Ptolemy, p. 110), the country of the Kulindrine, Kulindas, was located somewhere in the mountainous region around the sources of Vipasha (the Beas), the Shatadru (the Satluj), the Yamuna and the Ganga...Kulindas emerged as a powerful warrior community...upgrade them as the vratya kshatriya...(Manusmriti, 10.20.22)"(Omacanda Handa, 2004, Naga cults and traditions in the western Himalaya, Indus publishing, p.76.)

In Dyuta parva (Sabhaparva, Mahabharata) Duryodhana said: "I describe that large mass of wealth consisting of various kinds of tribute presented to Yudhishthira by the kings of the earth. They that dwell by the side of the river Sailoda flowing between the mountains of Mer and Mandara and enjoy the delicious shade of topes of the Kichaka bamboo, viz., the Khashas, Ekasanas, the Arhas, the Pradaras, the Dirghavenus, the Paradas, the Kulindas, the Tanganas, and the other Tanganas, brought as tribute heaps of gold measured in dronas (jars) and raised from underneath the earth by ants and therefore called after these creatures." [cf. Section LI, Kisari Mohan Ganguli's translation (1883-1896)].

The Kuninda warrior clan is mentioned in ancient texts under the different forms of its name: Kauninda, Kulinda, and Kaulinda. Their coins have been found mostly in the Himalayan foothills, between the Rivers Sutlej and Yamuna. The Kuninda were therefore neighbors of the Kuluta and Trigarta clans.

Their coins have the figure of Bhagwan Shiva holding a trident, with the legend: Bhagwatah Chatresvara-Mahatmanah, translating to Bhagwan Shiva, tutelary deity of Ahichhatra, the Kuninda capital. On the obverse the coins portray a deer, six-arched hill, and a tree-in-railing.

These coins are made of copper, silver, and bronze, and are found from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. This suggests that the Kuninda gained independence from both the Indo-Greek and Kushan invaders. A Raja named Amoghabhuti features prominently in the later coins, which bear a striking resemblance to the coinage of the Yaudheya clan. It seems that the Kunindas in alliance with the latter ejected the Kushans in the 3rd century CE.

By the 5th century the clan-state of the Kuninda disappeared, or more accurately, broke-up into tiny fragments under the families of Ranas and Thakkuras just as their neighbors the Kuluta. The region of Simla Hills, down to the 20th century, was littered with tiny entities ruled by such petty chieftains, which were grouped by the British Empire into the Simla Hill States.

Silver coin of the Kuninda Kingdom, c. 1st century BCE.

Obv: Deer standing right, crowned by two cobras, attended by Lakshmi holding a lotus flower. Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right): Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").

Rev: Stupa surmounted by the Buddhist symbol triratna, and surrounded by a swastika, a "Y" symbol, and a tree in railing. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas"). NB: Note the svastika, tree and mountain glyphs; these are Indus script hieroglyphs on the coin, attesting to the survival of the writing system in metallurgical contexts -- in this case, in the context of a mint. Note on Kuninda.

IGNCA Newsletter, 2003 Vol. III (May - June)

Syena Chiti, Garuda shaped Chiti Schematic as described by John F Price. Context: Panjal Atiratra yajnam (2011). cf.The paper of John Price: Applied geometry of śulbasūtras.

First layer of vakrapakṣa śyena altar. The wings are made from 60 bricks of type 'a', and the body, head and tail from 50 type 'b', 6 of type 'c' and 24 type 'd' bricks. Each subsequent layer was laid out using different patterns of bricks with the total number of bricks equalling 200.

"Sênmurw (Pahlavi), Sîna-Mrû (Pâzand), a fabulous, mythical bird. The name derives from Avestan mərəγô saênô 'the bird Saêna', originally a raptor, either eagle or falcon, as can be deduced from the etymologically identical Sanskrit śyena."

Senmurv on the tomb of Abbess Theodote, Pavia early 8th c. "Griffin-like .

Simurgh (Persian: سیمرغ), also spelled simorgh, simurg, simoorg or simourv, also known as Angha (Persian: عنقا), is the modern Persian name for a fabulous, benevolent, mythical flying creature. The figure can be found in all periods of Greater Iranian art and literature, and is evident also in the iconography of medieval Armenia, the Byzantine empire , and other regions that were within the sphere of Persian cultural influence. Through cultural assimilation the Simurgh was introduced to the Arabic-speaking world, where the concept was conflated with other Arabic mythical birds such as the Ghoghnus, a bird having some mythical relation with the date palm, and further developed as the Rukh (the origin of the English word "Roc")." http://www.flickr.com/photos/27305838@N04/4830444236/

See: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/simorg

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simurgh

Sassanid silk twill textile of a simurgh in a beaded surround, 6-7th c. CE

"The simurgh was considered to purify the land and waters and hence bestow fertility. The creature represented the union between the earth and the sky, serving as mediator and messenger between the two. The simurgh roosted in Gaokerena, the Hōm (Avestan: Haoma) Tree of Life, which stands in the middle of the world sea Vourukhasa. The plant is potent medicine, is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. When the simurgh took flight, the leaves of the tree of life shook making all the seeds of every plant to fall out. These seeds floated around the world on the winds of Vayu-Vata and the rains of Tishtrya, in cosmology taking root to become every type of plant that ever lived, and curing all the illnesses of mankind. The relationship between the simurgh and Hōm is extremely close. Like the simurgh, Hōm is represented as a bird, a messenger and as the essence of purity that can heal any illness or wound. Hōm - appointed as the first priest - is the essence of divinity, a property it shares with the simurgh. The Hōm is in addition the vehicle of farr(ah) (MP: khwarrah, Avestan: khvarenah, kavaēm kharēno) "[divine] glory" or "fortune". Farrah in turn represents the divine mandate that was the foundation of a king's authority."Sogdian Samarqand in the 7th century AD Archaeology in the landscapes of ancient Sogd has furnished us with a great amount of works of art, mainly from the early Middle Ages. Of highest value are the wall paintings from a palace hall (object 23, room 1) of the Sogdian ruler Varxuman at Samarqand (Afrasiab site)... The western wall is the most important one in room 23/1 due to its position opposite the entrance. This feature seems to be common in Sogdian architectural layouts both of private main halls and palace throne rooms. Who is figure no. 4 of the western wall? (page II) The following proposal for an identification of figure 4 is certainly only an attempt. As we have seen, group A2 of delegates seems to belong to nations of the west. A second hint comes from the clothes of figure 4. The delicate ornamentation depicts fabulous beasts known as "Senmurvs". Look below:

Left: The Senmurvs are set into an overall pattern of curved rhomboids.

Right: Close-up of the garment of figure 4 Originally more than hundred human figures must have been depicted on the walls of our room. Many of these persons are dressed with richly ornamented and multicoloured clothes. But it seems noteworthy that the Senmurv is, in contrary to other patterns, only to meet with figure 4 on the western wall. The reason for that must be the symbolic nature of the Senmurv. Speaking of this creature we concentrate only on the "dog-peackock" as depicted on the Afrasiab murals. Doubtless it originates from Iranian symbolism. The most spectacular examples can be seen on the late Sasanian rock reliefs of Taq-e Bustan (Iran):

Left: Senmurvs as pattern on the caftan of a Sasanian king, Taq-e Bustan, Great Ivan, left wall.

Right: Senmurv in medaillon on the clothes of the heavy-armoured rider, Taq-e Bustan, Geat Ivan. Comparing these images with the Senmurvs from Afrasiab we notice a striking similarity. Apparently the Senmurv in Sasanian iconography was a symbol with intimate connection to kingship. Images concentrate on representations of royal persons and on royal silverware. Only in post-Sasanian times, when dynastic restrictions were lost, the Senmurv spread wide as a merely ornamental motif on Near and Middle Eastern textiles, metalwork, and so on. Concerning the Afrasiab murals we have a general date within the limits of the Sasanian dynasty (i.e., before 652), as we have tried to explain on another page. Therefore, if the Senmurv (i.e., the "dog-peacock"!) was a Sasanian royal emblem, his appearance on the Afrasiab murals should point to the same symbolic value. In other words: The "owner" of the symbol should represent a Sasanian king. http://www.orientarch.uni-halle.de/ca/afras/text/w4b.htm

Wall panel with a Senmurv. Iran, Chal Tarhan. 7th-8th c. Stucco.Inv. Nr. 6642. Image of a quite similar panel which is in better condition that came from the same site, see British Museum, inv. no. ME 1973.7-25.3.

Sassanid silver plate of a simurgh (Sēnmurw), 7-8th c. CE. An exquisite and beautifully gilded Sassanid silver plate. The central creature within it is usually identified as the senmurw of Zoroastrian mythology which features the head of a snarling dog, the paws of a lion and the tail of a peacock. This object is today displayed in the Persian Empire collection of the British Museum. Peacock-dragon or peacock-griffin?

British Museum. Department: Middle East Registration number: 1922,0308.1 BM/Big number: 124095. Date 7thC-8thC (?) Description Gilded silver plate with low foot-rim and centering mark on the underside; single line engraved around the outside of the rim, with a second engraved line defining the interior; hammered and lathe-turned, then decorated; interior shows a senmurw (a legendary dog-headed bird) facing left, a leaf hanging from its mouth; neck and lower portion of the wing are punched with an imbricated design; the breast is enriched with a foliated motif; the tail feathers are conventionally rendered by punching, the lowest portion concealed by a bold scroll in relief; below the tail, a branch of foliage projects into the field; the foliate border is composed of overlapping leaves, on each of which are punched three divergent stems surmounted by berries in groups of three. Old corrosion attack on part of the underside. Condition of gilding suggests that this is re-gilding. Dimensions : Diameter: 18.8 centimetres (rim)Diameter: 6.8 centimetres (interior, foot-ring)Diameter: 7.3 centimetres (exterior, foot-ring)Height: 3.8 centimetres Volume: 450 millilitresWeight: 541.5 grammes. Hammered gilt silver plate with a low circular foot ring measuring 7.3 cm. across at the base; centering mark and extensive traces of old corrosion attack on the underside; single line engraved around the outside of the rim, with a second engraved line defining the interior. The plate was made by hammering, and decorated through a combination of chasing and punching, with thick gilding over the background. Early published references to the raised portion being embossed separately and added with solder are incorrect, and only the foot ring is soldered on. XRF analysis indicates that the body has a composition of 92% silver, 6.9% copper and 0.45% gold, and the foot has a slightly different composition of 93.4% silver, 5.4% copper and 0.5% gold. The decoration is limited to the interior and shows a composite animal with a dog's head, short erect mane, vertical tufted ears and lion's paws, facing left with a foliate spray dangling from its open mouth like a lolling tongue; a ruff-like circle of hair or fur frames its face; the neck, muscular shoulders and lower tail feathers are punched with an imbricated or overlapping wave design resembling feathers or scales; the breast is enriched with a foliated motif; a pair of wings with forward curling tips rise vertically from behind the shoulders, with a broad rounded peacock-like tail behind decorated with a bold foliate scroll and conventionally rendered by punching; below the tail, a second branch of foliage projects into the field. The foliate border is composed of overlapping leaves, on which are punched three divergent stems surmounted by berries in groups of three. This plate is said to have been obtained in India prior to 1922 when it was purchased in London by the National Art Collections Fund on behalf of the British Museum. It is usually attributed to the 7th, 8th or early 9th century, thus is post-Sasanian, Umayyad or early Abbasid in political terms. Initially described as a hippocamp, peacock-dragon or peacock-griffin, most scholars follow Trever's (1938) identification of this as a senmurw (New Persian simurgh), or Avestan Saena bird (cf. also Schmidt 1980). The iconographic features of a senmurw include the head of a snarling dog, the paws of a lion and the tail of a peacock, with the addition of the plant motifs on the tail or hanging out of the mouth being allusions to its role in regenerating plants. This bird is described in Pahlavi literature as nesting "on the tree without evil and of many seeds" (Menog-i Xrad 61.37-42), and scattering them in the rainy season to encourage future growth (Bundahišn XVI.4). For this reason it was believed to bestow khwarnah (glory and good fortune), and particularly that of the Kayanids, the legendary ancestors of the Sasanians. This motif is first attested in a datable Sasanian context on the rock-cut grotto of Khusrau II (r. 591-628) at Taq-i Bustan, when it appears within embroidered roundels decorating the royal gown. The same motif recurs within a repeating pattern of conjoined pearl roundels depicted on silks from the reliquary of St Lupus and a tomb at Mochtchevaja Balka in the north Caucasus, a press-moulded glass inlay and vessel appliqué in the Corning Museum of Glass, metalwork, Sogdian murals, and the late Umayyad palace façade at Mshatta (e.g. Harper et al. 1978: 136, no. 60; Trever & Lukonin 1987: 115, pl. 73, no. 26; Overlaet ed. 1993: 270, 275-77, nos 119, 127-28). However, there are significant differences of detail between all of these, and a little caution is necessary before making definite attributions of iconography, date or provenance. Many of the features are also repeated on the depiction of a horned quadruped depicted on a 7th century plate in the Hermitage (Trever & Lukonin 1987: 117-18, pl. 106, no. 36); most recently, Jens Kröger has reiterated the possibility of an early Abbasid date for the present plate, and observed that the distinctive decoration on the tail resembles the split palmette motifs on early Abbasid and Fatimid rock crystal. Source: http://tinyurl.com/7wbzcxgThe heroic theft: myths from Rgveda and the Ancient Near East - David M. Knipe (1967)

Annex:

SIMORḠ (Persian), Sēnmurw (Pahlavi), Sīna-Mrū (Pāzand), a fabulous, mythical bird. The name derives from Avestan mərəγō saēnō ‘the bird Saēna’, originally a raptor, either eagle or falcon, as can be deduced from the etymologically identical Sanskrit śyená.

SIMORḠ (Persian), Sēnmurw (Pahlavi), Sīna-Mrū (Pāzand), a fabulous, mythical bird. The name derives from Avestan mərəγō saēnō ‘the bird Saēna’, originally a raptor, either eagle or falcon, as can be deduced from the etymologically identical Sanskrit śyená. Saēna is also attested as a personal name which is derived from the bird name.

In the Avestan Yašt 14.41 Vərəθraγna, the deity of victory, wraps xᵛarnah, fortune, round the house of the worshipper, for wealth in cattle, like the great bird Saēna, and as the watery clouds cover the great mountains, which means that Saēna will bring rain. In Yašt 12.17 Saēna’s tree stands in the middle of the sea Vourukaša, it has good and potent medicine, is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. This scanty information is supplemented by the Pahlavi texts. In theMēnōg ī Xrad (ed. Anklesaria, 61.37-41) the Sēnmurw’s nest is on the “tree without evil and of many seeds.” When the bird rises, a thousand shoots grow from the tree, and when he (or she) alights, he breaks a thousand shoots and lets the seeds drop from them. The bird Cīnāmrōš (Camrōš) collects the seeds and disperses them where Tištar (Sirius) will seize the water with the seeds and rain them down on the earth. While here the bird breaks the branches with his weight, in Bundahišn 16.4 (tr. Anklesaria) he makes the tree wither, which seems to connect him with the scorching sun. An abbreviated form of this description is found in Zādspram 3.39; a gloss on the Pahlavi translation of Yašt 14.41 confuses the tree of many seeds with the tree of the White Hōm. Two birds are involved in the scattering of the seeds also in the New Persian Rivāyat of Dārāb Hormazyār (tr. Dhabhar, p. 99), here called Amrōš and Camrōš, Amrōš taking the place of Sēnmurw; these names derive from Avestan amru and camru, personal names taken from bird names.

The seasonal activity of the Sēnmurw in conjunction with Camrōš and Tištar can be interpreted consistently in astronomical terms. The identity of Tištar with Sirius, the brightest star of the constellation Canis Major (the Great Dog), is well established, and it can be assumed that Sēnmurw and Camrōš are stars, too. For Sēnmurw the constellation Aquila (Eagle), or its most prominent star, Altair (Ar. al-ṭayr ’the bird’), is the most likely candidate. The heliacal rise of Sirius in July corresponds to the setting of Aquila. Camrōš may be identified with Cygnus (Swan), which sets some time after Aquila. The influence of Greek astronomy and astrology is well attested in Sasanian Iran, but itself goes back to Babylonian sources, and it is quite possible that the Avestan source was dependent on them (contra Schmidt, p. 10). The assumption that the rise of Tištar signals the beginning of the rains, as it does in Egypt, and must therefore be a direct borrowing, is not compatible with the climate of most of Iran. The rise of Tištar will rather signal the beginning of his fight with Apaoša, the demon of drought. In the torrid summer months Tištar gains in strength, and it is with the defeat of Apaoša that the rains begin in late fall (cf. Forssman, p. 57 n. 9; Panaino, p. 18ff.).

In the Pahlavi Rivāyat accompanying the Dādestān ī Dēnīg (ed. Dhabhar, 31c8) the Sēnmurw makes his/her nest in the forest at the time of the resurrection when the earth becomes flat and the waters stand still. As Williams (II, p. 185) rightly remarks, this means that the Sēnmurw will retire from his/her task to distribute the seeds of the plants. In the Ayādgār-ī Zarērān (Jamasp-Asa I, 12.3) Zarēr’s horse is called sēn-i murwag, possibly because of its strength and swiftness.

The Sēnmurw has an evil counterpart in the bird Kamak, who is one of the monsters killed by Karšāsp (Mēnōg-ī Xrad 27.50). The SaddarBundahišn (20.37-43; tr. Dhabhar, p. 518) gives a description of its activities which are the exact opposite of those of the Sēnmurw: When Kamak appeared he spread his wings over the whole world, all the rain fell on his wings and back into the sea, drought struck the earth, men died, springs, rivers and wells dried up. Kamak devoured men and animals as a bird pecks grain. Karšāsp showers arrows on him day and night like rain till he succumbs. In killing men Kamak is the opposite of Camrōš, who pecks up the enemies of Iran like grain (Bundahišn 24.24).

In the chapter on the classification of animals of the Bundahišn the three-fingered Sēn is called the largest of the birds (13.10), and also the Sēnmurw is of the species of birds (13.22); they are obviously identical. The three-fingered Sēn was created first among the birds, but is not the chief, a position held by the Karšipt (according to the Indian Bundahišn 24.11 a carg, falcon or hawk), the bird that brought the religion to the enclosure (var) of Jamšēd (cf. Vd. 2.42) (17.11). In 13.34-35 the Sēnmurw has come to the sea Frāxkard (Vourukaša) before all the other birds. In Zādspram 23.2 the Karšipt and the Sēnmurw are singled out among the birds to attend the conference with Ōhrmazd on the animals, the creatures protected by Wahman. Bundahišn 13 contains serious contradictions. While in 10 and 22 the Sēnmurw is a bird, in 23 it is one of the species of bats: they are of the genera of the dog, the bird, and the muskrat because they fly like a bird, have teeth like a dog and a cave for dwelling like the muskrat. Zādspram 3.65 does not make the bats a separate genus, but counts them and the Sēnmurw among the birds, though they are of a different nature, having teeth and feeding their young with milk from their breasts.Bundahišn 13.23 contradicts not only 10 and 22 but also 15.13, where the Sēnmurw is counted among the oviparous birds. From this stare of affairs it can be inferred that there was an older version, in which the Sēnmurw was a bird pure and simple as in the Avesta, and a later one, in which she was a bat, and that the compiler of theBundahišn has confused them. With the change to a bat the Sēnmurw changed gender from male to female.

An identification of the original Sēnmurw with a known bird is difficult. The Sēn’s being called three-fingered is puzzling, since most birds have four claws. Herzfeld (1930, pp. 142-43) suggested the ostrich, which has only three claws, but this is impossible because the ostrich is an African flightless bird. The epithet may then be based on the observation of the bird when perching on the branch of a tree when only three claws are visible. The Sēnmurw in representative art also has only three claws but, contrary to my earlier opinion (Schmidt, p. 59), it is hardly the source of the description. The three-fingered Sēn is the largest bird (Bundahišn 13.10) mentioned among the large birds, side by side with the eagle (āluh) and the lammergeier (dālman); this excludes the falcon, which is much smaller than either of them. In size and habitat the closest possibility would be the black vulture (Aigypius monachus), which nests mostly in trees, but as a scavenger does not hunt live prey. Therefore I would suggest the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), particularly if the identification with the constellation Aquila is correct. That the Simorḡ was not known solely as a mythological being, but also as a real bird, can be inferred from the fact that in Judeo-Persian the word translates the Hebrew näšär ‘eagle’ (cf. Asmussen).

In post-Sasanian times the Simorḡ occurs in the epic, folktales, and mystical literature (cf. PLATE I, a medieval representation [see IL-KHANIDS iii. BOOK ILLUSTRATION). In Ferdowsi’s Šāh-nāma Simorḡ is the savior, tutor and guardian of Zāl-e zar. This motif is attested first in Iran for Achaemenes, who was reared by an eagle according to Aelian (De natura animalium XII, 2). Because Zāl was born an albino, his father Sām considered him to be of demonic origin and exposed him in the Alburz mountains. The female bird Simorḡ found the child when she was searching for food for her young. God gave the bird the feeling of love (mehr) for the child. Seeing that the child was crying for milk, she took him to her nest to rear him with her own young, which also showed love for the boy. She chose the most tender meat for him so that he could suck the blood as a substitute for the milk he lacked. When Zāl was grown up, Sām had a dream that made him repent his sin, and set out in search of his son. He found him with the Simorḡ, who returned the young man to his father. Before letting him go, she gave him one of her feathers: by burning it he would be able to call her for help (Šāh-nāma, ed. Mohl, I, p. 217ff.). The first time she was called for assistance was at the birth of Zāl’s son, Rostam. The bird suggested they anaesthetize the mother with wine before opening up her side and also prescribed the herbs for healing the wound; the healing was completed by touching the wound with the bird’s feather (I, p. 351ff.). For the second and last time the Simorḡ was called when Rostam and his horse Raḵš were wounded by the arrows of Esfandiār; she extracted the arrows and healed the wounds. Knowing the secrets of fate (rāz-e sepehr) she warned that whoever killed Esfandiār would be damned in this and the next world. Finally, however, she took Rostam in a single night to the tamarisk tree from which the fatal arrow was cut (IV, p. 665ff.). Zāl called the wings of the Simorḡ fortune and grace (farr), and she offered him the feather with the words: “be always in the shadow of my fortune and grace (sāya-ye farr-e man)” (I, p. 226 lines 175, 181). Metaphorically this conveys the sense of protection and the granting of boons and powers. It is similar to the wrapping of fortune round the house in Yašt 14.41. When coming down from the mountain, the Simorḡ is compared to a cloud, a comparison also implied in the Yašt. She presses Zāl’s body against her breast and thereby fills the world with the smell of musk. This may be a reflex of the muskrat nature of the Sēnmurw in the Bundahišn .

The Simorḡ, protector of Zāl and Rostam, has an evil counterpart called by the same name. She lives on a mountain and looks like a mountain or a black cloud; she can carry off crocodiles, panthers and elephants. She has two young ones as big as herself. This Simorḡ is one of the adversaries Esfandiār kills in the course of his seven exploits on the way to the castle of Arjāsp. To overcome the huge monster Esfandiār constructs a large chariot spiked all over with swords which cut the bird to pieces (IV, p. 509f.). It is not impossible that both birds are originally identical and the Simorḡ is ambivalent. Her benevolent behavior towards Zāl was due to God’s intervention, and went against her nature as a raptor. In the contemptuous description of Zāl’s origin it is said that the Simorḡ spared the child because she could not stomach him (IV, p. 612).

Trever (pp. 20-21) quotes two Kurdish folktales about a bird called Sīmīr, the Kurdish reflex of Simorḡ. In one of them the hero rescues the young of the birds by killing a snake that is crawling up the tree to devour them. As a reward Sīmīr gives him three of her feathers; by burning them he can call her for help. Later he calls her, and she carries him to a distant land. In the other tale she carries the hero out of the netherworld; here she feeds her young with her teats, a trait which agrees with the description of the Sēnmurw by Zādspram. The bird also feeds the hero on the journey while he feeds her with pieces of sheep’s fat and water. Similar is an Armenian folktale (Trever, p. 21-22) in which the hero is lost in the netherworld and only the bird Sīnam can carry him out. The young of Sīnam are regularly eaten by the serpent Višap. The hero kills the snake and goes to sleep under the tree. The returning bird spreads her wings to shield him from the sun. As reward she takes him to the world of light. He must feed her with sheep’s fat and wine. When the fat is eaten up the hero cuts a piece of flesh from his leg and gives it to the bird. She recognizes that it is human flesh and does not swallow it, but restores it to the hero’s leg at the end of the journey, a deed consonant with the curative powers of the Simorḡ. These versions obviously go back to the common stock of Iranian Simorḡ stories (see Marzolph, Types 301, 301E*, 449, 550(8), 707(1)). Similar tales are widely attested in Eurasian folklore (cf. Ruben, pp. 511ff.).

In classical and modern Persian literature the Simorḡ is frequently mentioned, particularly as a metaphor for God in Sufi mysticism. In this context the bird is probably understood as male. The most famous example is Farid-al-Din ʿAṭṭār’sManṭeq al-ṭayr ‘The parliament of the birds’ (cf. Ritter, p. 11ff., Bürgel, pp. 5-6). The Simorḡ is the king of the birds; he is close to them, but they are far from him, he lives behind the mountains called Kāf, his dwelling is inaccessible, no tongue can utter his name. Before him hang a hundred thousand veils of light and darkness. “Once, Simorḡ unveiled his face like the sun and cast his shadow over the earth...Every garment covering the fields is a shadow of the beautiful Simorḡ.” Fauth (p. 128) sees in this a memory of the Sēnmurw dispersing the seeds. Thirty birds (si morḡ) that have survived the hard and perilous quest for their king reach his palace. Coming face to face with the sun of his majesty they realize that they, the thirty birds of the outer world, are one with the Simorḡ of the inner world. Finally the birds lose themselves forever in the Simorḡ they, the shadows, are lost in him, the sun.

The classification of the Sēnmurw as a bat belonging to three genera in theBundahišn has led Camilla Trever to identify a composite animal in Sasanian art as the Sēnmurw. This animal has the head of a dog, the wings and—in most examples—the tail of a peacock. It has precursors in Scythian art of a millennium earlier, one example of which shows a striking resemblance to the Sasanian representation (Schmidt, fig. 2); it cannot be established what they were called nor can a historical connection be made, because composite animals of similar type are found in the Near East, Central Asia, and China. Various forerunners have been claimed as a model, such as the lion-griffin of Mesopotamia (Harper, 1961, pp. 95-101) and the Hellenistic hippocampus (Herzfeld, 1920, p. 134), but it is unlikely that one single source can be identified. In Sasanian art the image is clearly attested in the 6th-7th century, the most famous examples being those shown on the garments of King Ḵosrow II Parvēz (r. 591-628) on the rock reliefs of Ṭāq-e Bustān (Schmidt, figs. 4 and 5). The animal is depicted with the head of a snarling dog. The two paws, one raised above the other in a posture of attack, are those of a beast of prey with only three claws. The wing feathers, which rise from a circular base, are curled towards the front. The long, raised, oval-shaped, curved tail is that of a peacock, not showing individual feathers but a highly stylized foliage pattern. The other examples agree to a large extent; many, however, show individual tail feathers. The Sēnmurw is attested in reliefs, metalware and textiles (representative examples can be seen in Schmidt, plates VI, VII, X, XI). It spread all over Eurasia with other motifs of Sasanian art and was used for many centuries after the fall of the Persian Empire. In early Islamic art it is found in Iran at Čāl Tarḵān Ashkhabad (Harper, 1978, p. 118), in Syria at Qaṣr al-Ḵayr al-Ḡarbi (Schlumberger, p. 355), in Jordan at Mshatta (Creswell, 1932, p. 404 with pl. 66), and at Ḵerbat al-Mafjar (Hamilton, figs. 118a, 253). It is also found in a Christian context in Georgia, Armenia and Byzantium (cf., e.g., Grabar pls. XV 2, XX 3, XXII 1, XXIII 3, XXVII 1, XXVIII 2; Trever, fig. 7; Chubinashvili, pls. 23, 26, 27).

The canine heads on headdresses of the queen and a prince on coins of Warahrān II (r. 276-293) have been interpreted as Sēnmurw, but this is a matter of debate (Schmidt, p. 24ff.). The Sēnmurw is very prominent on the coinage of the Hephthalites in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. It is distinguished from the standard Sasanian form by having rather a cock’s than a peacock’s tail and also frequently showing reptilian features, which are rare in the Sasanian form. Its head occurs as a crown-emblem in several issues (nos. 208-10, 241-243, 246, 254-255 in Göbl I, cf. the drawings in IV, pls. 6-7); in one issue (no. 259) the whole animal appears on the top of the crown. The head and neck, or the complete animal, are also used as countermarks (KM 102, 106, 107, 101, 106, 107, 101, 105, 3a-d, 11A-K, 1, 10 in Göbl II, 141ff., IV pl. 10). When carrying a pearl necklace in its mouth (Issue 255.1), the Sēnmurw is probably the conveyer of the investiture (Göbl, p. 156), whether the necklace can be identified with the xᵛarnah or not. Göbl also sees a proof for the Sēnmurw’s association with the xᵛarnah in the fact that the countermark is in all cases stamped at least approximately on the inscription GDH ʾpzwtˈ "[may] farrah [be] increased” or on the Sēnmurw of the coin; this, however, remains doubtful.

Nevertheless, the relation of the Sēnmurw to the xᵛarnah is undeniable. It is already present in the Avesta, and it is so in the Šāh-nāma. The feather is offered to Zāl as a token of the Simorḡ’s farr: since in Ṭāq-e Bustān the Sēnmurw does not occur in the investiture scene, it was probably not an exclusively royal symbol, but a more general one of good fortune.

We do not know how Ferdowsi, ʿAṭṭār and other Islamic authors visualized the Simorḡ. In the much later manuscript illustrations he/she is not a composite animal, but a fantastic bird (cf., e.g., Welch, pp. 125, 127).

It is rather obvious that the classification of the Sēnmurw as a bat is a rationalization, as Trever (p. 17) has pointed out, and that it derives from the representation in art. Once this image was adopted there arose the desire to find a model for it in nature, and the bat offered itself because of its resemblance to a dog and a bird. However, the images do not show the wings of a bat, but those of a feathered bird, and the peacock-tail does not fit either. We may speculate about the elements of this rationalization as follows.

The dispersal of the seeds of plants is characteristic of the fruit-bats (cf. van der Pijl), indigenous to the south of Iran: they carry the fruits some distances from the trees, chew them up and spit out the seeds. They generally live in trees, but one species, Rousettus, dwells in caves like the more common insectivorous bats (Slaughter and Walton, p. 163). Some species of bats have scent glands (Yalden and Morris, p. 200), which may have led to the connection of the Sēnmurw with the muskrat.

The dog component could be interpreted by the Sēnmurw’s close relationship to the “Dog star” Sirius, i.e., Tištar, the brightest star of the constellation Canis Major, assuming that the Latin name was known. In support of this may be quoted theRivāyat of Hormazyar Framarz (Dhabhar, p. 259) where the dog Zarrīnḡoš ‘Yellow-Ear’, who is obviously identical with the dawn-yellow-haired chief of the dog species (Bundahišn XVII 9), chases away demons and is the guardian of the body of Gayōmard. He keeps watch near the bridge of Činvat that leads to paradise. He who feeds dogs will be protected by Zarrīngōš from the demons even if he is otherwise fit for hell. The demons will not punish him, out of fear of Haftōrang, Ursa Major (the Great Bear), who guards souls fit for hell. Thus the whole scene is projected to the firmament, and Zarrīngōš will represent Canis Major. The source is late (17th century), but the function of Haftōrang is attested much earlier (Mēnōg-ī Xrad 48.15), and the whole may well represent an old tradition. On a Sasanian stamp we possibly have Gayōmard=Orion with a dog=Canis Major (Brunner apud Noveck, no. 61). When the Simorḡ carries her protégé to the netherworld and back, this is related to the well-known function of the dog as psychopompos.

The peacock, a bird native to India, not only lends itself to expressing beauty and splendor but is auspicious (Nair, 1977, p. 71) and a harbinger of the rainy season (pp. 13, 26, 40, 77, 91ff., 103), a characteristic it shares with the Sēnmurw. In the Indus Civilization the peacock seems to have been a psychopompos (Vats, 1940: I, p. 207f., II, pl. LVII 2). In the Buddhist Mora Jataka a king wants to eat the flesh of the golden peacock because it confers youth and immortality (Nair, pp. 210-11). Peacock and Simorḡ have closely related functions in the Tāriḵ-e moʿjam of Fażl-Allāh al-Ḥosayni, a fourteenth-century text that amalgamates the Old Iranian religion and its legends with Islamic Persian mysticism: When King Siyāmak is killed, Ṭāʾus (the peacock) carries his spirit (ruḥ) and Simorḡ his soul (ravān) to the height of the eight paradises (Hartman, 168, XXXIX).

Dog and peacock have a common connection with the rainy season, a feature which the Sēnmurw has had since its earliest attestation in the Avesta. It seems possible that this feature was one of the reasons behind the creation of the composite representation. The composite animals of earlier art will have contributed to the creation of the Sēnmurw image. If the above interpretations are correct, the astral connection was the decisive motive. It then follows that the Sasanian Sēnmurw was a conscious creation. The identification as a bat in the Bundahišn and in Zādspram was an afterthought.

In Armenia and the Caucasus the Simorḡ has a counterpart in Paskuč (and related forms of the name). This same name occurs in Manichaean Middle Persian (Henning, II, p. 274), where the spirit of fever, called Idra, has three forms and wings like a pšqwc and settles in the bones and skull of humans. In the Mēnōg-ī Xrad (26. 49-50) Sām Keršāsp is said to have slain the horned serpent and the grey-blue wolf called pašgunǰ; the wolf may be a winged one. The Armenian paskuc and the Georgian p’asgunǰi both translate the Greek gryps ‘gryphon, griffin’ in the Septuagint (Marr, p. 2083). It is also glossed as ‘bone-swallower’ (ossifrage, osprey) (Marr, p. 2087 n. 2), but also mentioned as a kind of eagle native to India. In Modern Armenian paskuč is the griffin vulture (Gyps fulvus). In Georgian sources a p’asgunǰiis described as having a body like that of a lion, head, beak, wings and feet like those of an eagle, and covered in down; some have four legs, some two; it carries off elephants and injures horses; others are like a very large eagle (Marr, p. 2083). In late mediaeval Georgian translations of the Šāh-nāma, Georgian p’asgunǰi renders the Persian simorḡ (Marr, p. 2085f.). In a Georgian parallel to the Armenian and Kurdish tales quoted earlier, the bird there called Sīnam and Sīmīr is replaced byp’asgunǰi (Levin-Schenkowitz, p. 1ff.). In a Talmudic tale a giant bird pwšqnṣʾswallows the giant serpent that has swallowed a giant toad and settles on a very strong tree; Daniel Gershenson (personal communication) interprets this as a metaphor for the coming of the rainy season: the frog represents water, the snake drought, and the Pušqanṣā the rainy season. The tale is thus a reworking of the Sēnmurw story. Talmudic commentators identify the bird as a gigantic raven. In an illustration in the Gerona manuscript of Beatus’s commentary on the Book of Revelation, the picture of the Sēnmurw opposite that of an eagle is found with the subscript coreus (read corvus) et aquila in venatione “raven and eagle on the hunt” (Grabar, pl. XXVIII fig. 2). This evidence shows that the Sēnmurw took different shapes in different cultures and that the same name was used for real birds and fabulous composites as well as for benevolent and malevolent beasts.

The Simorḡ’s equivalent in Arabic sources is the ʿAnqāʾ. The ambivalent nature of this bird is attested in the Hadith: the bird was created by God with all perfections, but became a plague, and a prophet put an end to the havoc it wrought by exterminating the species (Pellat, p. 509). In the Sumerian Lugalbanda Epic the mythical bird Anzu is a benevolent being. The hero frees the young of the bird, which in return blesses him. In the Sumerian Lugal-e and the Akkadian Anzu Epic the bird represents demonic powers and is vanquished by the god Ninurta. In the Akkadian Etana Epic the hero is carried by the eagle to the heaven of Anu. The correspondence of these motifs with the Simorḡ stories in the Šāhnāma and the Kurdish folktales is obvious, showing that they are of common Near Eastern heritage (Aro, p. 25ff.). In an illustration of a manuscript of the Thousand and One Nights the Simorḡ is identified with the monstrous bird Roḵ (cf. Casartellli, p. 82f.).

The Sēnmurw has many traits in common with the Indian Garuḍa, the steed of the god Viṣṇu (cf. Reuben, pp. 489ff., 495, 506f., 510, 515, 517). It is of particular interest that the comparison was made already in Sasanian times. In the first book of the Sanskrit Pañcatantra (the cognate of Kalila and Dimna) is a story of the birds of the shore who complain to their king Garuḍa. In Sogdian, synmrγ is used to translate garuḍa (see Utz, p. 14); and in the old Syriac translation of the Middle Persian original of Kalila and Dimna, Garuḍa is rendered by Simorḡ (cf. de Blois). Fauth (p. 125ff.) has argued that all the mythical giant birds—such as Simorḡ, Phoenix, Garuḍa, the Tibetan Khyuṅ, and also the Melek Ṭāʾus of the Yezidis—are offshoots of an archaic, primordial bird that created the world. Thus Simorḡ as God in Persian mysticism would, curiously, represent a return to the original meaning.

Bibliography:

This article is based mainly on the author’s "The Sēmurw. Of Birds and Dogs and Bats,” Persica 9, 1980, pp. 1-85.

An extensive collection of the pertinent literary material from the Avesta to the present is found in ʿAli Solṭāni Gord-Farāmarzi, Simorḡ dar qalamraw-i farhang-e Irān, Tehran, 1993.

B. T. Anklesaria, ed. and tr., Zand-Ākāsīh, Iranian or Greater Bundahišn, Bombay, 1956.

T. D. Anklesaria, Dânâk-u Mainyô-i Khard, Bombay, 1913.

J. Aro, “Anzu and Sīmurgh,” in Barry L. Eichler , ed., Kramer Anniversary Volume: Cuneiform studies in honor of Samuel Noah Kramer, Kevelar, 1976, pp. 25-28.

Jes P. Asmussen, “Sīmurγ in Judeo-Persian translations of the Hebrew Bible,” Acta Iranica 30, 1990, pp. 1-5.

V. F. Büchner, “Sīmurgh,” in EI ¹; F. C. de Blois, “Sīmurgh,” in EI ². J. C. Bürgel, The Feather of Simurgh, New York, 1988.

L. C. Casartelli, “Çyena—Simrgh—Roc,” in Congrès scientifique international des Catholiques, Paris, 1891, VI, pp. 79-86.

G. Chubinashvili, Gruzinskaya srednevekovaya khudozhestvennaya rez’ba po derevu, Tbilisi, 1958. A. C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture I, Oxford, 1932.

B. N. Dhabhar, The Persian Rivayats of Hormazyar Framarz, Bombay, 1932.

W. Fauth, “Der persische Simurġ und der Gabriel-Melek Ṭāʾūs der Jeziden,” Persica12, 1987, pp. 123-147.

B. Forssman, “Apaoša, der Gegner des Tištriia,” ZVS 82, 1968, pp. 37-61.

Ph. Gignoux and A. Tafazzoli, Anthologie de Zādspram, Paris, 1993.

R. Göbl, Dokumente zur Geschichte der Iranischen Hunnen in Baktrien und Indien I-IV, Wiesbaden, 1967.

A. Grabar, “Le rayonnement de l’art sassanide dans le monde chrétien,” in Atti del convegno interzionale sul Tema: La Persia nel Medioevo, Accademia dei Lincei, Rome, 1971, pp. 679-707.

R. W. Hamilton, Khirbat al Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley, Oxford, 1959.

P. O. Harper, “The Sēnmurw,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Series 2, 20, 1961.

Idem, The Royal Hunter. Art of the Sasanian Empire, New York, 1978.

S. Hartman, Gayomart, Uppsala, 1953.

W. B. Henning, Selected Papers II, Acta Iranica 15, Leiden, 1977.

Ernst Herzfeld, Am Tor von Asien, Berlin, 1920. Idem, “Zarathustra, Teil II: Die Heroogonie,” AMI I, Berlin, 1930, pp. 125-68.

J. M. Jamasp-Asana, The Pahlavi Texts I-II, Bombay, pp. 1897-1913.

I. Levin and G. Schenkowitz, Märchen aus dem Kaukasus, Düsseldorf, 1978.

N. Ya. Marr, “Ossetica-Japhetica,” in Izvestiya Rossiskoi Akademii Nauk 1918, pp. 2069-2100, 2307-2310.

Ulrich Marzolph, Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens, Beirut and Wiesbaden, 1984.

P. Th. Nair, The Peacock. The National Bird of India, Calcutta, 1977.

M. Noveck, The Mark of Ancient Man. Ancient Near Eastern Stamp Seals and Cylinder Seals: The Gorelick Collection, New York, 1975.

A. Panaino, Tištrya. Part II, The Iranian Myth of the Star Sirius, Rome, 1995. Ch. Pellat, “ʿAnqāʾ,” EI ². H. Ritter, Das Meer der Seele, Leiden, 1978.

W. Ruben, “On Garuḍa,” The Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society 27, 1941, pp. 485-520.

D. Schlumberger, “Les fouilles de Qasr el-Ḫeir el-Garbi (1936-38),” Syria 20, 1939, pp. 195-238, 324-373.

B. H. Slaughter and Dan W. Walton, eds., About Bats. A Chiropteran Biology Symposium, Dallas, 1970.

C. V. Trever, The Dog-Bird. Senmurw-Paskudj, Leningrad, 1938.

D. A. Utz, “An Unpublished Sogdiam Version of the Mahāyāna Manāparinirvāṇasutra in the German Turfan Collection,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1976.

L. van der Pijl, “The Dispersal of Plants by Bats,” Acta Botanica Neerlandica 6, 1957 pp. 291-315.

M. S. Vats, Excavations at Harappa I-II, Delhi, 1940.

S. C. Welch, A King’s Book of Kings, New York, 1972.

A. V. Williams, The Pahlavi Rivayat Accompanying the Dādestān ī Dēnīg I-II, Copenhagen, 1990.

D. W. Yalden and P. A. Morris, The Lives of Bats, Newton Abbot, London, and Vancouver, 1975.

(Hanns-Peter Schmidt)

Originally Published: July 20, 2002