Archaeometallury and Meluhha linguistics link Ancient Far East and Ancient Near East on Tin Road

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/12254845/Archaeometallury_and_Meluhha_linguistics_link_Ancient_Far_East_and_Ancient_Near_East_on_Tin_Road

This monograph expands on Le Minh Kha's insight on the presence of unique Meluhha hieroglyphs of water buffalo, elephant and zebu in Ancient Far East (Annex A) and on Wilhelm G. Solheim's hypothesis of a trade/culturfal link between Ancient Near East and the Mediterranean (Annex B).

Two of the most significant advances in the history of metals occurred with 1. the invention of cire-perdue (lost-wax method) castings of metal alloys and 2. discovery of tin-bronzes as a deliberate alloying to replace scarce, naturally-occurring arsenical-copper. Alloys of copper such as brass (copper plus zinc) and tin-bronze (copper plus tin) resulted in marked changes to ductility and malleability of natural mineral ores and resulted in hardness and sharpness needed for using alloys to make tools and weapons. This archaeometallurgical advance was possible because of the properties of tin or zinc as mineral ores.

Embedded are Meluhha glosses related to hard alloys, metalwork and hieroglyphs which point to the selection of hieroglyphs used to denote hard alloys in Meluhha speech. Further researches will help trace the glosses into Austro-Asiatic dialects of Southeast Asia.

Michael O. Schwartz et al note in their monograph on the 'Southeast Asian Tin Belt' that the world's largest resource zone for tin is Southeast Asia: "The Southeast Asian Tin Belt is a north-south elongate zone 2800 km long and 400 km wide, extending from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand to Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian Tin Islands. Altogether 9.6 million tonnes of tin, equivalent to 54% of the world's tin production is derived from this region.Most of the granitoids in the region can be grouped geographically into elongate provinces or belts, based on petrographic and geochronological features.- The Main Range Granitoid Province in western Peninsular Malaysia, southern Peninsular Thailand and central Thailand is almost entirely made up of biotite granite (184–230 Ma). Tin deposits associated with these granites contributed 55% of the historic tin production of Southeast Asia."(Schwartz, Michael O et al., 1995, The Southeast Asian tin belt - ResearchGate. Available from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/223354060_The_Southeast_Asian_tin_belt

How did this tin reach as far as Haifa, Israel where two pure tin ingots were discovered in a shipwreck? A hypthesis is posited that there was a Tin Road which facilitated the transfer of tin mineral from the Southeast Asian Tin Belt with intermediation by seafaring Meluhha merchants who had invented the Indus Script and established their presence in Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age.

Bronze artifacts discovered in Ban Chiang, Thailand (Southeast Asia) are dated to 2100 BCE and provide the framework for further analysing the contibutions made by artisans of Southeast Asia to the spread of tin-bronzes upto the Mediterranean. ("Bronze from Ban Chiang, Thailand: A view from the Laboratory"Expedition, 43/2, pp.7-8. Museum.upenn.edu. http://penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/43-2/Science.pdf).

A development as significant as the discovery of tin-bronzes was the development of a writing system called Indus Script. This has been shown to be based on rebus-metonymy layered cipher in Meluhha language (of Indian sprachbund). The Indus Script Corpora provide an array of hieroglyphs which were used to provide inscriptions on metalwork. Some of these hieroglyphs occur in Archaeometallurgical artifacts of Southeast Asia pointing to the possibility of presence of or contacts between Southeast Asian people and Meluhha speaking people and Meluhha artisans.

Archaeometallurgy and linguistics together provide a framework

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/12254845/Archaeometallury_and_Meluhha_linguistics_link_Ancient_Far_East_and_Ancient_Near_East_on_Tin_Road

This monograph expands on Le Minh Kha's insight on the presence of unique Meluhha hieroglyphs of water buffalo, elephant and zebu in Ancient Far East (Annex A) and on Wilhelm G. Solheim's hypothesis of a trade/culturfal link between Ancient Near East and the Mediterranean (Annex B).

Two of the most significant advances in the history of metals occurred with 1. the invention of cire-perdue (lost-wax method) castings of metal alloys and 2. discovery of tin-bronzes as a deliberate alloying to replace scarce, naturally-occurring arsenical-copper. Alloys of copper such as brass (copper plus zinc) and tin-bronze (copper plus tin) resulted in marked changes to ductility and malleability of natural mineral ores and resulted in hardness and sharpness needed for using alloys to make tools and weapons. This archaeometallurgical advance was possible because of the properties of tin or zinc as mineral ores.

Embedded are Meluhha glosses related to hard alloys, metalwork and hieroglyphs which point to the selection of hieroglyphs used to denote hard alloys in Meluhha speech. Further researches will help trace the glosses into Austro-Asiatic dialects of Southeast Asia.

Michael O. Schwartz et al note in their monograph on the 'Southeast Asian Tin Belt' that the world's largest resource zone for tin is Southeast Asia: "The Southeast Asian Tin Belt is a north-south elongate zone 2800 km long and 400 km wide, extending from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand to Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian Tin Islands. Altogether 9.6 million tonnes of tin, equivalent to 54% of the world's tin production is derived from this region.Most of the granitoids in the region can be grouped geographically into elongate provinces or belts, based on petrographic and geochronological features.- The Main Range Granitoid Province in western Peninsular Malaysia, southern Peninsular Thailand and central Thailand is almost entirely made up of biotite granite (184–230 Ma). Tin deposits associated with these granites contributed 55% of the historic tin production of Southeast Asia."(Schwartz, Michael O et al., 1995, The Southeast Asian tin belt - ResearchGate. Available from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/223354060_The_Southeast_Asian_tin_belt

How did this tin reach as far as Haifa, Israel where two pure tin ingots were discovered in a shipwreck? A hypthesis is posited that there was a Tin Road which facilitated the transfer of tin mineral from the Southeast Asian Tin Belt with intermediation by seafaring Meluhha merchants who had invented the Indus Script and established their presence in Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age.

Bronze artifacts discovered in Ban Chiang, Thailand (Southeast Asia) are dated to 2100 BCE and provide the framework for further analysing the contibutions made by artisans of Southeast Asia to the spread of tin-bronzes upto the Mediterranean. ("Bronze from Ban Chiang, Thailand: A view from the Laboratory"Expedition, 43/2, pp.7-8. Museum.upenn.edu. http://penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/43-2/Science.pdf).

A development as significant as the discovery of tin-bronzes was the development of a writing system called Indus Script. This has been shown to be based on rebus-metonymy layered cipher in Meluhha language (of Indian sprachbund). The Indus Script Corpora provide an array of hieroglyphs which were used to provide inscriptions on metalwork. Some of these hieroglyphs occur in Archaeometallurgical artifacts of Southeast Asia pointing to the possibility of presence of or contacts between Southeast Asian people and Meluhha speaking people and Meluhha artisans.

Archaeometallurgy and linguistics together provide a framework

for a study of "interactions between metals and societies" -- a research discipline suggested Thornton and Roberts in the context of the 73rd meeting of the Society for American Archaeology held in Vancouver, Canada, on 26th–30th March 2008. (Thornton C, and Roberts B. 2009. Introduction: The Beginnings of Metallurgy in Global Perspective. Journal of World Prehistory 22(3):181-184.) .

Gordon Childe argued for the emergence of complex societies led by the roles of ‘itinerant metal smiths’ and bronze production in Ancient Near East and Eurasia. [Childe, V. G. (1939). The Orient and Europe. American Journal of Archaeology, 43(1), 10–26; Childe, V. G. (1944). Archaeological ages as technological stages. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 74, 7–24.)]

With the decipherment of Indus Script Corpora as metalwork catalogues, the focus shifts to the contributions made by Meluhha metalworkers to the diffusion of metallurgy to Ancient Near East -- with possible links to the Ancient Far East which has the world's largest tin belt mineral resource --, because many hieroglyphs of Indus Script continue to be used in Ancient Near East archaeological artifacts and cylinder seals and perhaps also on the Bronze Đông Sơn and Ngoc Lu drums of Vietnam of 1st millennium BCE cast by the cire perdue method and inscribed with hieroglyphs, evoking Meluhha hieroglyhph tradition of earlier millennia. [The drums, cast in tin-bronze use the lost-wax casting method are up to a meter in height and weigh up to 100 kilograms (220 lb).]

The transactions of seafaring merchants of Meluhha along the Tin Road are matched by DNA studies which point to migrations into the Ancient Far East of Austro-Asiatic speakers out of India.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

May 6, 2015

Tin provinces of the world. From Taylor (1979) (After Fig. 1 in Schwartz, Michael O. et al

Pinnow-map of Austro-Asiatic language speakershttp://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/aa.html

Some Bronze Age sites, Far East. (After Fig. 2.2 in Higham, Charles, 1996, The bronze age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge Univ. Press

Stannifrous areas of the world (From RG Taylor, Geology of Tin Deposits, Amsterdam 1979, 6, fig. 2.1)

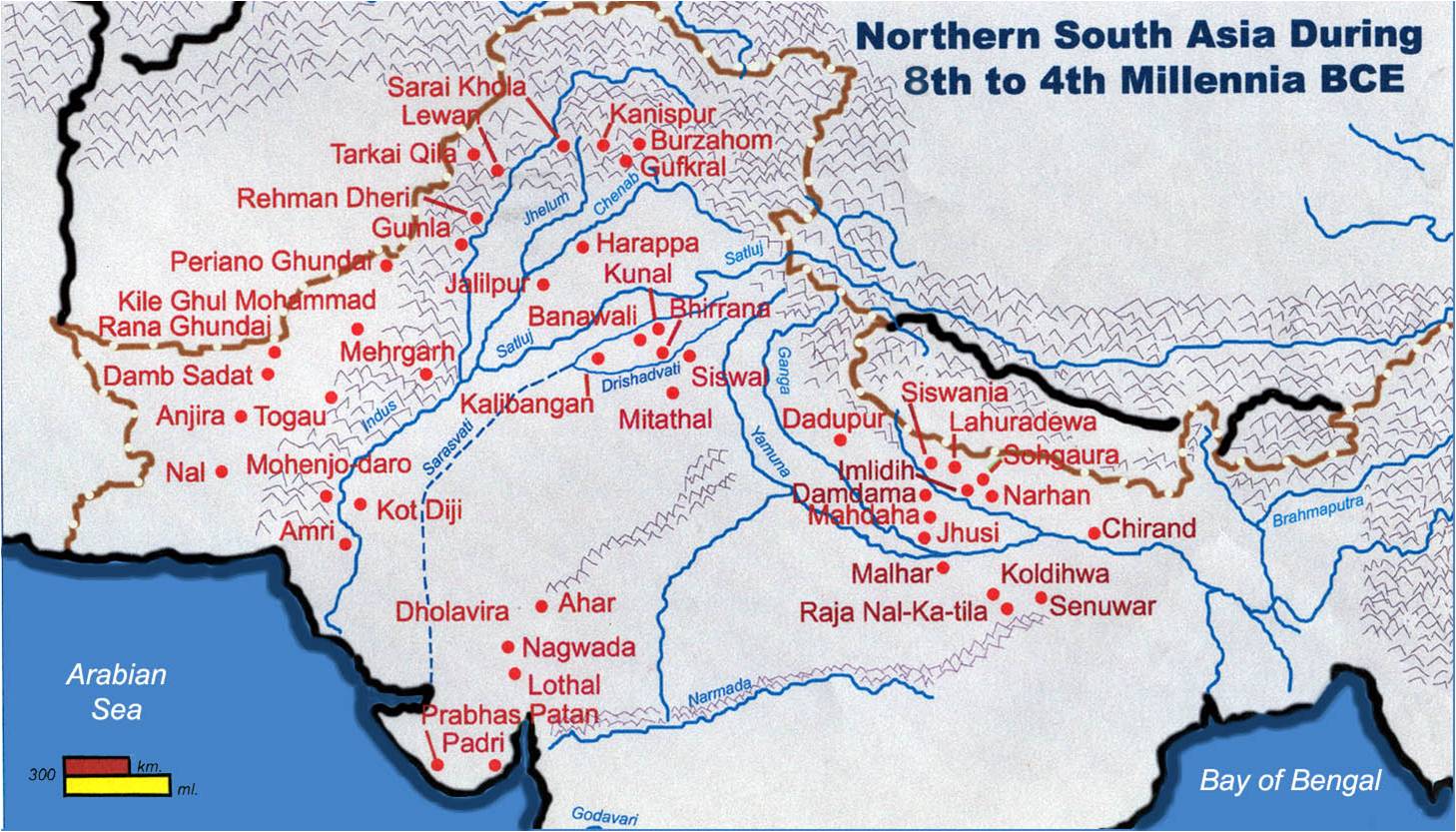

Bronze Age sites of eastern Bha_rata and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2. Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6. Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa; 8. Mohenjo-daro; 9. Ahar; 10.Kayatha; 11. Navdatoli; 12. Inamgaon; 13. Non Pa Wai; 14. Nong Nor; 15. Ban Na Di and Ban Chiang; 16. Non Nok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

Haifa tin ingot 1: Inscribed tin ingot with a moulded head, from Haifa (Artzy, 1983: 53). The Meluhha hieroglyphs catalog and certify that this is a tin ingot: Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) Rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Santali). The three hieroglyphs are: ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali) ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali). dāṭu = cross (Te.); dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā ‘to send out, pour out, cast (metal)’ (CDIAL 6771). [The 'cross' or X hieroglyph is incised on Haifa tin ingots 2&3.]

Migration of Haplogroup O-M175 (~35,000 years ago) explains 1) the Tin Road transactions of tin-bronzes between Vietnam and the Mediterranean and 2) spread of some glosses of Indian sprachbund languages into Southeast Asia (Northern Vietnam)

The archaeometallurgical revolution created by tin-bronzes and other metal alloys in the Levant and Ancient Near East points to an area which constitutes the largest tin-belt of the world: Southeast Asia (Ancient Far East) and zawar zinc mines. Tin plus copper alloy yielded bronze; zinc plus copper alloy yielded brass. These alloys together with the archaeometallurgical invention of cire perdue (lost-wax) method of alloy metal castings revolutionized the Bronze Age. It is notable that almost all the Dong Son bronze drums are made using the cire perdue (lost-wax) method of alloy casting together with inscription on the drums and other artifacts of hieroglyphs commonly deployed on Indus Script Corpora to signify metalwork.

The migration of Haplogroup O-M175 may explain the link between Dong Son culture of Vietnam and Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization studies which point to a Tin Road linking Hanoi, Vietnam and Haifa, Israel during the Bronze Age. This explanation is consistent with the possible occurrence of Meluhha hieroglyphs (of Indus Script Corpora) on Dong Son Culture artifacts. The typical hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora which also occur on Dong Son culture artifacts and Dong Son Bronze drums are: tiger, elephant, peacock, zebu, buffalo, fish, frog, sun. These hieroglyphs have been read as descriptive elements of metalwork catalogues, using rebus-metonymy layered cipher. It is likely that the same readings may be applied to the Dong Son culture artifacts with such hieroglyphs, ASSUMING that the Meluhha metalwork artisans had migrated to northern Vietnam. Such an assumption is consistent with the new light of October 2007, focussed on Southeast Asia archaeology studies by Wilhelm G. Solhem II (Annex B)

In molecular evolution, a haplogroup (from the Greek: ἁπλούς, haploûs, "onefold, single, simple") is a group of similar haplotypes that share a common ancestor having the same single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation in all haplotypes. Haplogroup O-M175 is a Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup of Southeast Asian and East Asian lineage. It descends from Haplogroup NO.

| Possible time of origin | 28,000-41,000 years BP (Scheinfeldt 2006) |

|---|---|

| Possible place of origin | Southeast or East Asia |

| Ancestor | NO |

| Descendants | O-MSY2.2, O-M268, O-M122 |

| Defining mutations | M175, P186, P191, P196 |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_O-M175

These contributions by Meluhha metalworkers -- in terms of new metal alloys, includin tin-bronzes, evolved and methods of metalcastings using cire perdue (lost-wax) methods -- are seen by matching archaeometallurgical studies with studies of Meluhha linguistics.

"Archaeometallurgy is an interdisciplinary and international field of study that examines all aspects of the production, use, and consumption of metals from ∼8000 BCE to the present..." (Killick D, and Fenn T. 2012. Archaeometallurgy: The Study of Preindustrial Mining and Metallurgy. Annual Review of Anthropology 41(1):559-575

).

Archaeometallurgy is essentially metals history which recounts human exploration of the earth's resources triggered by attractions to metals such as gold and silver. Long-distance trade in such metals is a record of such metals history.. Evidence is provided by archaeometallurgical studies related to metals trade along the Tin Road from Hanoi, Vietnam to Haifa, Israel.

Archaeometallurgy is an "interdisciplinary endeavor in which soft science scholars such as archaeologists, historians, numismatists, and philologists find themselves consorting with hard scientists such as geologists, materials scientists, chemists, physicists, botanists and toxicologists, as well as mining engineers, blacksmiths, and goldsmiths." (Hirst, K. Kris, 2012, Archaeometallurgy) http://archaeology.about.com/od/metallurgy/tp/Metal-History.htm

Cyril Stanley Smith, a historian of science and technology noted that the first properties of metals which were most relevant to their users were color, luster, ductility and tonality; it was not until the metals were treated (cast, alloyed and/or exposed to heat) that metals became suitable as tools and weapons.

"Cyril Stanley Smith retired from MIT in 1969, as professor emeritus of the History of Science and Technology, professor emeritus of Metallurgy and Humanities and Institute Professor Emeritus (“a title reserved for only a few whose work transcends the boundaries of traditional departments and disciplines”). His three emeritus titles “reflected the facets of his rich and varied career in science, technology, history and the arts.” He was “recognized as an authority on the historical relationships between people from the beginning of human history and the materials they came to understand and use. Smith was a pioneer in the application of materials science and engineering to the study of archaeological artifacts."

Sequential elements of Dong Son tradition multiple pictorial band drums (After Fig. 3, Kouko, 2010)

![Dong Son bronze axe (2) Rìu đồng Đông Sơn Dong Son bronze axe (2) Rìu đồng Đông Sơn]()

The comon hieroglyphs on Dong Son bronzes are:

Dong Son bronze axe (2) Rìu đồng Đông Sơn

The comon hieroglyphs on Dong Son bronzes are:

- peacocks

- feathered dancers, some shown as seafaring merchants on boats

- cranes (egrets, herons) in flight

- fish

- sun (with 12 point emanating rays)

- warriors wielding swords,spears and shields

- aquatic birds

- round and flat roofed houses

- pairs of standing figures pounding rice

- platforms containing drummers beating time with sticks and

- parading musicians

- frogs surrounding the tympanum

- zebu

- frogs

- elephant

- tiger

Rebus: pola (magnetite)

Hieroglyph of a worshipper kneeling: Konḍa (BB) meḍa, meṇḍa id. Pe. menḍa id. Manḍ. menḍe id. Kui menḍa id. Kuwi (F.) menda, (S. Su. P.) menḍa, (Isr.) meṇḍa id. Ta. maṇṭi kneeling, kneeling on one knee as an archer. Ma.maṇṭuka to be seated on the heels. Ka. maṇḍi what is bent, the knee. Tu. maṇḍi knee. Te. maṇḍĭ̄ kneeling on one knee. Pa.maḍtel knee; maḍi kuḍtel kneeling position. Go. (L.) meṇḍā, (G. Mu. Ma.) Cf. 4645 Ta.maṭaṅku (maṇi-forms). / ? Cf. Skt. maṇḍūkī- (DEDR 4677)

Hieroglyph: frog: maṇḍa -- 5 m. ʻ frog ʼ .<menDaka>(A) {N} ``^frog''. *Hi.<mE~dhak>, Skt.<maNDu:kam>. #21820. <poto menDka>(Z) {N} ``^toad''. |<poto> `?'. ^frog (which lives out of water). *Loan?. #27302. <o~ia mendka>(Z),,<oJa mendka>(Z) {N} ``^bullfrog''. |<o~ia> `id.'. ??RECTE D? #24562 (Gorum)

Rebus: meḍ 'iron, metalwork, metal castings'(Ho.Mu.)

Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'kolhe, smelters'; 'working in iron'

Hieroglyph: ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron' (Santali) ibbo 'merchant' (Des'i)

Hình thuyền trên một trống đồng Điền (nguồn 1).

Dong Son Bronze artiface. Zebu and a rider.

Elephant + riders.Den Dong.

Bronze cross bow in Vietnam (nỏ đồng)

Bronze bell with elephant hieroglyph. Hieroglyph: ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant' (Des'i)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/doremon360/3677153606/in/photostream/

Dong Son weapons (Vũ khí)

Bronze dagger collection

Dong Son bronze axe

Một vật đựng vỏ ốc sứ diễn tả một cảnh hiến tế người có ba trống đồng nhỏ chồng lên nhau diễn tả Trục Thế Giới thân trống nối dài (nguồn 1).

Một trống đồng Điền trưng bầy cảnh nhẩy múa hát ca. Mặt trống không có các trang trí và mặt trời thường thấy (nguồn 1).

Một vật đựng vỏ ốc sứ trên nắp diễn tả một cảnh tế lễ phóng lớn, Viện Bảo Tàng Tỉnh Vân Nam (ảnh của Michelle Mai Nguyễn).

Left to right: house depicted on a Dongson drum, Toraja houses in Sulawesi, depiction of a Tien house in Yunnan

Vật đựng vỏ ốc sứ hình thạp trụ tròn hay trống đồng hình trụ ống Nguyễn Xuân Quang II, Bảo Tàng Viện Tỉnh Vân Nam (ảnh của tác giả).

Vật đựng vỏ ốc sứ trên nắp có các hình tượng diễn tả một cảnh hiến tế (206 BC-25 AD, khu mộ Số 20, Trại Thạch Sơn) (1).

Vật đựng vỏ ốc sứ do hai trống đồng Cây Nấm Vũ Trụ chồng lên nhau, Bảo Tàng Viện Tỉnh Vân Nam (nguồn 1).

Trang trí hình người mang âm tính (có thể là Mẹ Đời sinh tạo hay âm thần sinh tử) (1 và ảnh của tác giả).

Cán kiếm thờ mạ vàng đầu rắn (nguồn 1).

Figure II: Dong Son Drum (left) and ShizhaishanDrum (right)[28]

Bronze bell. TRAN VAN TOT; Introduction a l'Art ancien du VietNam, in Bulletin

Artifacts. Dong Son culture.

What was the bronze drum called in ancient times? Tanbur?

Tanbur, a long-necked, string instrument originating in the Southern or Central Asia (Mesopotamia and Persia/Iran)

Iranian tanbur (Kurdish tanbur), used in Yarsan rituals

Turkish tambur, instrument played in Turkey

Yaylı tambur, also played in Turkey

Tanpura, a drone instrument played in India

Tambura (instrument), played in Balkan peninsula

Tamburica, any member of a family of long-necked lutes popular in Eastern and Central Europe

Tambouras, played in Greece

Tanbūra (lyre), played in East Africa and the Middle East

Dombra, instrument in Kazakhstan, Siberia, and Mongolia

Domra, Russian instrument

Cyprus castings of bronze stands with Meluhha hieroglyphs. AN391894001 AN258515001 British Museum. Bibliographic reference

Kiely 2011a M.12Macnamara & Meeks 1987 p. 58, no. 2

Catling 1964 pp. 205-207, no. 34; pl. 34

Giorgos Papassavas argues convincingly that the cyprus bronze-stands of this type were cast using the lost wax method. The Meluhha hieroglyphs (Indus writing) of reed and tambura player are read rebus.

Hieroglyph: kã̄ḍ reed Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hieroglyph: tanbūra 'lyre' Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper'.

Dao Thinh bronze jar dated back to 2.500 years ago. It is the largest ever known jar in Viet Nam, using an enormous amount of bronze of up to 760 kg. This jar is a typical object in domestic utensils, with mainly functioning as food container. The jar is a unique ancient art object bearing decorative carvings carrying a message of the material life and sexual reproduction conception of the Dong Son people in the past.

Hieroglyph: Ko.geṇḍ kaṭ - (kac-) dog's penis becomes stuck in copulation. Ka.geṇḍe penis Go. (Tr. Ph.) geṭānā, (Mu.) gēṭ to have sexual intercourse; (Mu.) gēṭ sexual intercourse (Voc. 1181).(DEDR 1949). Rebus: khāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans, metalware' (Marathi) kāṇḍa id. (Gujarati)

http://www.vietnamheritage.com.vn/pages/en/1351381034968-When-making-l-ove-was-exalted.html

Quote

On the cover of a bronze jar excavated in Đào Thịnh Village, Yen Bai Province and dated 500 BCE, there is the design of the sun radiating its rays from the centre and four figurines of human couples in the position of intercourse in the four directions; at the bottom of the jar there is a bas-relief with a circle of interlinking boats with the bow of the following one touching the stern of the preceding one and the dragons-crocodiles on them are also locked into a mating posture. Images of birds, animals, and toads in intercourse are also present. We should take notice of the symbolism of the toad as a form of prayer for rainfall and good harvest and the intercourse image of toads is clearly significant in fertility cults.

People on Dong Son bronze jar

People on Dong Son bronze drum

Frog Drum detail. Trống đồng tượng cóc

Dong Son drum from selayar? Note: hieroglyphs of elephant, trees and peacocks

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/doremon360/1528885793/in/album-72157621598852916/

Hieroglyph: mora 'peacock' moraa 'peafowl' (Hindi) Rebus: morakkhaka loha 'a kind of coper, grouped with pis'aacaloha' (Pali); moraka 'a kind of steel' (Samskritam)

See: https://www.academia.edu/10153387/Meluhha_hieroglyphs_and_Candi_Sukuh_hieroglyphs_related_to_metalwork

Dong Son bronze drums, Dong Son culture, Bao Thinh jar

Cambodian bronze drum

Boat people and fishes

Song Da Drum (known as he Moulie Drum) Vietnam, Song Da basin

Song Dong Son II culture, 1st millennium BCE (mid) Bronze 61 x 78 cm Former Moulié collection P 243

"This drum is composed of a resonant top resting on a flared torus, a cylindrical case, and a sawn-off cone base; four double handles link the upper part to the central section. The whole instrument has a plane decoration of alternating geometrical motifs and stylized figurative images. The top is embellished with a central star around which are disposed various concentrically arranged scenes, no doubt related to long vanished fertility rites. These depict feather-decked warriors marching towards the dwelling of the deceased: a house on piles with a platform on which other figures are pounding grains of rice into drums. On the case, "ships of the dead", decorated with heads and tails of birds, carry away warrior-spirits while similar warrior-spirits alternate with geometrical motifs on the vertical body of the instrument.

Large bronze objects occupy a particularly significant place in Dong Son art and their style, essentially featuring geometric and animal motifs, displays great homogeneity. This culture, the name of which derives from the eponymous Dong Son site, emerged during the late Bronze and early Iron Age and its powerful influence extended as far as the Indonesian archipelago. Its social organization was based around large, rice-growing, village communities, apparently linked together in a tribal confederation. These drums attest to well-organized trade and political networks enabling the chiefs to procure the necessary materials involved in their making.

...

Dong Son culture and Cuu Chan districts in Hung Kings time:

Dong Son relics of the Bronze age in the present-day Ham Rong precinct, Thanh Hoa city, is the most important site in Vietnam archeology and well-known in the world.Vietnam Vietnam South Vietnam Vietnam

...

Historians agree in the point that Vietnam possesses an extensive culture community, which back-stretches itself up to the center of the Millenniums before Christus. This culture community, which is called Dong Son culture, reached its high point in the middle centuries of the Millenniums A.D. Different trends, which were conditioned locally (delta of the Red River, the Ma and Ca River), united to the community of the Dong Son culture. The Dong Son culture was more developed than the others in the region at this time. It possessed still also thing in common with them, which is characterized as the Austro-Mongolian and water rice culture. This was also the time, in which the primitive nation form formed from communities of villages and/or village combinations, together with it and in order to repel itself against the hostile attacks both the intruders and nature."

| Dong Son Editions, 1989 |

The Bronze Dong Son Drums |

Nguyen van Huyen |

|

Description | |

| Dong Son Culture, which lasted about 1000 years from the 7th to 2nd centuries BC, is considered the peak of metallurgical technique in the Vietnam history. Dong Son Drums, or the Heger I Bronze Drum according to the classification of the Austrian archaeologist, Franz Heger, are divided into three parts: a bulging shoulder, a slim body, and an expanding base. This volume is the first extensive compilation of surveys on this bronze drum, the symbol of the roots of the Vietnamese people. This publication includes clear illustrations of each item, along with a full analysis by well-known Vietnamese scholars. |

Height 22.5 cm. (25 cm. with frogs). Diameter 33 cm.

This bronze item, called Bao Thinh Jar, is a national treasure. It was discovered in the town of Yen (Yen Bai Province).

This bronze item, called Bao Thinh Jar, is a national treasure. It was discovered in the town of Yen (Yen Bai Province).

A bronze drum named Lac, which was discovered in Lac Village, Nghe An Province.

Subtle patterns on the surface of a bronze drum discovered in Coc Leu, Lao Cai Province.

Tung Lam bronze drum found in Chuong My, Ha Noi.

Motifs on the bronze drum found in Dong Xa, Hung Yen Province.

A ceramic vase.

Floral motifs on a bronze bell discovered in Moc Son, Thanh Hoa.

Source: http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/art-entertainment/116959/11-dong-son-bronze-drums--vietnam-treasures.html 11 Dong Son bronze drums: Vietnam treasures

VietNamNet Bridge – Ancient drums and hundreds of antiques of the Dong Son culture were on display at the National History Museum in Hanoi in November 2014.

Trống đồng Sông Đà (Song Da bronze drum)

The early production of bronze drums was in Yunnan, Guangxi and Northern Vietnam. There was a southward expansion of the distribution indicating long distance trade of bronze drums. It is possible that one drum was cast by the lost-wax method in Thailand. Extremely large drums also came from Burma and from small islands of Eastern Indonesia such as Sangeang, Salayar, Alor, Roti, Leti and Kur and as artifacts of exquisite artisanship and in some cases show feathered dancers arranged in double rows. What languages or dialects did the hieroglyphs represent?

Kouko notes: 'The changes in the distribution of bronze drums reveal that prehistoric and early historic Southeast Asia and Southern China was not a mere agglomeration of isolated small worlds but a network linked areas more or less in unison.'

400+ examples of drums have been reported from Burma, Cambodia, southern China, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Thailand, central and southern Vietnam, thus covering an interaction area of 10 million square kms. These finds are matched by other artifacts such as high-tin bronze bowls, leaded high tin-bronze mirrors, agate, carnelian, glass and nephrite ornaments and distinctive regional pottery types, all of which point to a trade interaction area from mid-1st millennium BCE.

I suggest that Meluhha seafaring merchants accounted for this distribution activity of Dong Son bronze drums and other metalwork, lapidary crafts of semiprecious stones.

The hieroglyphs are: solar representations, naturalistic amphibian figurines on the tympanum, stylized human dancers, birds, musical instruments, ships or boats on the mantle. The key in validating this hypothesis is to decipher the hieroglyphs on Dong Son bronze drums so vividly displayed.

Vietnamese antiques on display

Updated 15:59, Friday, 27/07/2012 (GMT+7)

The National Museum of History coordinated with the Thang Long Antique Association and antique collectors to co-organize an exhibition named “Vietnamese antiques” on July 25.

In recent years, many associations of antique collectors have been formed in various localities, which opens a legal playground for those who have compassion for antiques. Their activities also help preserve and promote Vietnam’s cultural values.

Over 50 special items were selected for display from members of the Thang Long Antique Association. The following are some of them.

| Wooden Buddha Statute of 4-6th century |

| Buddha and Hindo statutes |

| Vishnu Statute of 12-13th century |

http://english.baoquangninh.com.vn/photo-news/201207/Vietnamese-antiques-on-display-2172924/

Meluhha glosses related to hard alloys, metalwork and hieroglyphs

करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ]Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c (Marathi)करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] m The arrangement of bars or embossed lines (plain or fretted with little knobs) raised upon a तार of gold by pressing and driving it upon the अवटी or grooved stamp. Such तार is used for the ornament बुगडी , for the hilt of a पट्टा or other sword &c. Applied also to any similar barform or line-form arrangement (pectination) whether embossed or indented; as the edging of a rupee &c. करड्याची अवटी (p. 137) [ karaḍyācī avaṭī ] f An implement of the goldsmith. A stamp for forming the bars or raised lines called करडा . It is channeled or grooved with (or without) little cavities. खरडबरड (p. 197) [ kharaḍabaraḍa ] a Stony and sterile--land.(Marathi) கரடு¹ karaṭu, n. [K. M. karaḍu.] 1. Roughness, ruggedness, unevenness; முருடு. ஈண்டுரு காக் கரடு (அருட்பா, iv, பத்தி. 6). 2. Churlish temper முருட்டுக்குணம். (Tamil)

காரடையாநோன்பு kāraṭaiyā-nōṉpu, n. < காரடை + ஆம் +. A ceremonial fast observed by women when the sun passes from Aquarius to Pisces, praying for the longevity of their husbands; மாசியும் பங்குனியும் கூடும்நாளில் தம் கணவ ரின் தீர்க்காயுளைக் கருதிக் காரடையை உணவாகக் கொண்டு மகளிர் கைக்கொள்ளும் ஒரு விரதம். (Tamil)

खरड्या (p. 197) [ kharaḍyā ] m or खरड्यावाघ m A leopard.(Marathi. Molesworth)

Ta. karaṭi, karuṭi, keruṭi fencing, school or gymnasium where wrestling and fencing are taught. Ka. garaḍi, garuḍi fencing school. Tu. garaḍi, garoḍi id. Te. gariḍi, gariḍī id., fencing. (DEDR 1262)

Ta. karaṭi, karaṭi-ppaṟai, karaṭikai a kind of drum (said to sound like a bear, karaṭi). Ka. karaḍi, karaḍe an oblong drum beaten on both sides, a sort of double drum. / Cf. Skt. karaṭa- a kind of drum.(DEDR 1264)

Ta. karaṭu ankle, knot in wood. Ma. karaṇa knot of sugar-cane; kuraṭṭa knuckle of hand or foot. Ka. karaṇe, kaṇṇe clot, lump. Te. karuḍu lump, mass, clot. (DEDR 1266)

Ta. karaṇṭi spoon or ladle. Ma. karaṇṭi spoon. Te. garĩṭe, gaṇṭe, geṇṭe spoon, ladle. Kol. (SR.) gāṭe spoon; (Kamaleswaran). Kuwi (S.) garti (brass) spoon.(DEDR 1267)

<kakOrO>(MP) {N} ``^dew''. {ADJ} `` ^cold''. *O.<kakOrO>P, L.<kAkkAr> `ice', Sk.<kArkArA> `hard, firm'. %15901. #15791.

Ta. karaṭu roughness, unevenness, churlish temper; karaṭṭu rugged, uneven, unpolished; karaṇ uneven surface in vegetables and fruits, scar; karuprong, barb, spike; karumai, karil severity, cruelty; karukku teeth of a saw or sickle, jagged edge of palmyra leaf-stalk, sharpness. Ma. karaṭu what is rough or uneven; kaṟu rough; kaṟuppu roughness; karuma

sharpness of sword; karukku teeth of a saw or file, thorns of a palmyra branch, irregular surface; karukarukka to be harsh, sharp, rough, irritating; karikku edge of teeth; kari-muḷ hard thorn; projecting parts of the skin of custard-apples, jack-fruits, etc.; kari-maṭal rind of jack-fruits. Ko. karp keenness or harshness (of wind); ? kako·ṭ hoe with sharp, broad blade (for -ko·ṭ, see 2064). Ka.karaḍu that is rough, uneven, unpolished, hard, or waste, useless, or wicked; kaṟaku, karku, kakku, gaṟaku, garaku, garku, garasu a jag, notch, dent, toothed part of a file or saw, rough part of a millstone, irregular surface, sharpness. Tu. karaḍů, karaḍu rough, coarse, worn out; wastage, loss, wear;kargōṭa hardness, hard-heartedness; hard, hard-hearted; garu rough; garime severity, strictness; gargāsů a saw. Te. kara sharp; karagasamu a saw;karakasa roughness; karusu rough, harsh; harsh words; kaṟaku, kaṟuku harshness, roughness, sharpness; rough, harsh, sharp; gari hardness, stiffness, sharpness; (B.) karaṭi stubborn, brutish, villainous; kakku a notch or dent, toothed part of a saw, file, or sickle, roughness of a millstone. Go. (Ma.)karkara sharp (Voc. 543). Kur. karcnā to be tough, (Hahn) be hardened. ? Cf. 1260 Ka. garasu. / Cf. Skt. karaṭa- a low, unruly, difficult person;karkara- hard, firm; karkaśa- rough, harsh, hard; krakaca-, karapattra- saw; khara- hard, harsh, rough, sharp-edged; kharu- harsh, cruel; Pali kakaca-saw; khara- rough; saw; Pkt. karakaya- saw; Apabhraṃśa (Jasaharacariu) karaḍa- hard. Cf. esp. Turner, CDIAL, no. 2819. Cf. also Skt. karavāla-sword (for second element, cf. 5376 Ta. vāḷ) (DEDR 1265) khára2 ʻ hard, sharp, pungent ʼ MBh., ʻ solid ʼ Pān., ʻ hot (of wind) ʼ Suśr. [Cf. karkara -- 1 , karkaśá -- , kakkhaṭa -- ]Pa. Pk. khara -- ʻ hard, rough, cruel, sharp ʼ; K. khoru ʻ pure, genuine ʼ, S. kharo, L. P. kharā (P. also ʻ good of weather ʼ); WPah. bhad. kharo ʻ good ʼ, paṅ. cur. cam. kharā ʻ good, clean ʼ; Ku. kharo ʻ honest ʼ; N. kharo ʻ real, keen ʼ; A. khar ʻ quick, nimble ʼ, m. ʻ dry weather ʼ, kharā ʻ dry, infertile ʼ,khariba ʻ to become dry ʼ; B. kharā ʻ hot, dry ʼ, vb. ʻ to overparch ʼ; Or. kharā ʻ sunshine ʼ; OAw. khara ʻ sharp, notched ʼ; H. kharā ʻ sharp, pure, good ʼ; G. khar ʻ sharp, hot ʼ, °rũ ʻ real, good, well parched or baked, well learnt ʼ; M. khar ʻ sharp, biting, thick (of consistency) ʼ, °rā ʻ pure, good, firm ʼ; Ko.kharo ʻ true ʼ; Si. kara -- räs ʻ hot -- rayed, i.e. sun ʼ. -- Ext. Pk. kharaḍia -- ʻ rough ʼ; Or. kharaṛā ʻ slightly parched ʼ. <-> X kṣārá -- 1 : Or. khārā ʻ very sharp, pure, true ʼ. <-> X paruṣá -- 1 : Bshk. khärúṣ ʻ rough, rugged ʼ; Si. karahu ʻ hard ʼ.kharapattrā -- , kharayaṣṭikā -- , *kharasrōtas -- .WPah.kṭg. (kc.) khɔ́rɔ ʻ great, good, excessive ʼ; J. kharā ʻ good, well ʼ; OMarw. kharaü ʻ extreme ʼ.(CDIAL 3819) karkara1 ʻ hard, firm ʼ Mālatīm. [Prob. same as karkara -- 2 ; cf. karkaśá -- , kakkhaṭa -- , *kakkaṭa -- 2 , khára -- 2 ]Pa. kakkaratā -- f., °riya -- n. ʻ roughness, harshness ʼ; Pk. kakkara -- ʻ hard, firm ʼ; Tir. kaṅgará, Paš. kaṅgarāˊ m. ʻ ice ʼ (→ Psht. kaṅgal, karaṅg ʻ ice ʼ IIFL iii 3, 95); K. trakoru ʻ hard, rough ʼ < *krak -- FestskrBroch 149; L. kakkar m. ʻ frost, raw thong ʼ; P. kakkar m. ʻ frost ʼ; WPah. khaś. kakru ʻ ice ʼ; Or.kākara, kã̄k° ʻ dew ʼ; G. kakrũ ʻ rough ʼ.(CDIAL 2819)

kṣará ʻ melting away ʼ ŚvetUp., m. ʻ cloud ʼ, n. ʻ water ʼ lex. 2. *kṣarā -- f. (after sarāˊ -- ?). [~ jhara -- . -- √kṣar ]1. Pa. khara -- m. ʻ water ʼ; Pk. khara -- ʻ wasting away ʼ; Dm. c̣har ʻ rapids in a stream ʼ, Gaw. c̣hār NTS xii 165, čhār (c̣h?) NOGaw 33; Phal. c̣hār ʻ waterfall ʼ, Sh. c̣har m.; A. khar ʻ dysentery ʼ.2. K. char f. ʻ a sprinkle of water etc. from the fingers ʼ; S. chara f. ʻ an expanse of water ʼ.(CDIAL 3662).

karaka2 m., °kā -- f. ʻ hail ʼ lex. Pa. karaka -- m., °kā -- f., Pk. kara -- , °raya -- m., °raā -- f.; Or. karā ʻ hailstone ʼ; G. karā m. pl. ʻ hail ʼ. Ko. karo ʻ hail ʼ, cf. M. gārā ʻ hail ʼ?(CDIAL 2782) *gaḍa3 ʻ dropping ʼ. [√gaḍ ]Pa. gaḷa -- m. ʻ a drop ʼ, gaḷāgalaṁ gacchati ʻ goes from fall to fall ʼ; S. g̠aṛo m. ʻ hail ʼ, L. (Ju.) g̠aṛā m., P. gaṛā m. (cf. galā < gala -- 1 ); -- Pk. gaḍa -- n. ʻ large stone ʼ?(CDIAL 3969)

kaṇṭa1 m. ʻ thorn ʼ BhP. 2. káṇṭaka -- m. ʻ thorn ʼ ŚBr., ʻ anything pointed ʼ R.

1. Pa. kaṇṭa -- m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Gy. pal. ḳand, Sh. koh. gur. kōṇ m., Ku. gng. kã̄ṇ, A. kāĩṭ (< nom. *kaṇṭē?), Mth. Bhoj. kã̄ṭ, OH. kã̄ṭa. 2. Pa. kaṇṭaka -- m. ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ; Pk. kaṁṭaya<-> m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Gy. eur. kanro m., SEeur. kai̦o, Dm. kãṭa, Phal. kāṇḍu, kã̄ṛo, Sh. gil. kóṇŭ m., K. konḍu m., S. kaṇḍo m., L. P. kaṇḍā m., WPah. khaś. kaṇṭā m., bhal. kaṇṭo m., jaun. kã̄ḍā, Ku. kāno; N. kã̄ṛo ʻ thorn, afterbirth ʼ (semant. cf. śalyá -- ); B. kã̄ṭā ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ, Or. kaṇṭā; Aw. lakh. H. kã̄ṭā m.; G. kã̄ṭɔ ʻ thorn, fishbone ʼ; M. kã̄ṭā, kāṭā m. ʻ thorn ʼ, Ko. kāṇṭo, Si. kaṭuva.1. A. also kã̄iṭ; Md. kaři ʻ thorn, bone ʼ.2. káṇṭaka -- : S.kcch. kaṇḍho m. ʻ thorn ʼ; WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kaṇḍɔ m. ʻ thorn, mountain peak ʼ, J. kã̄ḍā m.; Garh. kã̄ḍu ʻ thorn ʼ.(CDIAL 2668) கரடு¹ karaṭuHillock, low hill (Tamil)

karkara2 m.n. ʻ stone ʼ, m. ʻ bone ʼ lex. [Prob. same as karkara -- 1 : for semant. development ʻ ice ~ hail ~ stone ʼ cf. aśáni -- , úpala -- ]Pk. kakkara -- m. ʻ stone, pebble ʼ; S. kakiro m. ʻ stone ʼ, °rī f. ʻ stone in the bladder ʼ; L. kakrā m. ʻ gravel ʼ; A. kã̄kar ʻ stone, pebble ʼ; B. kã̄kar ʻ gravel ʼ, Or. kāṅkara, kaṅ°; Bi. kãkrāhī ʻ gravelly soil ʼ; OAw. kāṁkara ʻ gravel ʼ; H. kã̄kar, kaṅkar, °krā m. ʻ nodule of limestone ʼ, kã̄krī, kaṅk° f. ʻ gravel ʼ; G.kã̄krɔ m. ʻ pebble ʼ, °rī f. ʻ small pebble, sand ʼ, kākriyũ ʻ abounding in pebbles ʼ, n. ʻ stony field ʼ; M. kaṅkar m. ʻ pebble, gravel' S.kcch. kakro m. ʻ pebble ʼ.(CDIAL 2820).

<taTia>(M),,<tatia>(P) {N} ``metal ^cup, ^frying_^pan''. *Ho<cele>, H.<kARahi>, Sa.<tutiA> `blue vitriol, bluestone, sulphate of copper', H.<tutIya>. %31451. #31231.

<kaDamaru uDaG>(Z) [kaRamaru uRaG] {N} ``^eagle, ^White-bellied_Sea-eagle''. |<kaDamaru> `?', <uDaG> `a large bird'. ^bird. #15420.

garuḍá m. ʻ a mythical bird ʼ Mn.Pa. garuḷa -- m., Pk. garuḍa -- , °ula -- m.; P. garaṛ m. ʻ the bird Ardea argala ʼ; N. garul ʻ eagle ʼ, Bhoj. gaṛur; OAw. garura ʻ blue jay ʼ; H. garuṛ m. ʻ hornbill ʼ, garul ʻ a large vulture ʼ; Si. guruḷā ʻ bird ʼ (kurullā infl. by Tam.?). -- Kal. rumb. gōrvḗlik ʻ kite ʼ??(CDIAL 4041)

suparṇá ʻ having beautiful wings ʼ, m. ʻ any large bird of prey, a mythical bird ʼ RV. [su -- 2 , parṇá -- ]Pa. supaṇṇa -- m. ʻ the bird Garuḍa ʼ, Si. suvan.(CDIAL 13476) Rebus: suvárṇa 'gold' 13519 suvárṇa ʻ of bright colour, golden ʼ RV., n. ʻ gold ʼ AV., suvarṇaka -- ʻ golden ʼ Hariv. 2. saúvarṇa- ʻ golden ʼ ŚrS., n. ʻ gold ʼ MBh. -- In many cases it is impossible to distinguish whether a NIA. form is derived from suvárṇa -- or saúvarṇa -- : they are therefore listed below together. [su --2 , várṇa -- 1 ]1. Pa. suvaṇṇa -- ʻ of good colour ʼ, n. ʻ gold ʼ, soṇṇa<-> ʻ golden ʼ, n. ʻ gold ʼ; NiDoc. suv́arna ʻ gold ʼ; Pk. su(v)aṇṇa -- , soṇṇa -- n. ʻ gold ʼ, suvaṇṇia -- ʻ golden ʼ.

2. Pa. sōvaṇṇa -- , °aya -- ʻ golden ʼ; Pk. sō(v)aṇṇa -- n. ʻ gold ʼ, Ap. sōvaṇa -- n.1 or 2. Gy. gr. sovnakáy, wel. sōnakai, rum. somnakáy m. ʻ gold ʼ, Ḍ. son m.; -- (Kaf. forms ← Ind. NTS ii 276) Ash. sun, Wg. sū̃n, Kt. sun f., Pr. sü; <-> Dm. sōn, Paš.lauṛ. sū˘wan, Gmb. sōʻ n, Gaw. sōṇ, sūṇ, (→ Sv. son NOPhal 47), Kal. sū̃ṛa, sū̃ŕä, Phal. suāṇ, Sh.gil. so̯n m., koh. sonŭ m., gur. son m., dr. jij.sōṇ m., pales. lēlo swã̄ṛə ʻ gold ʼ, gil. (Lor.) sōno ʻ golden ʼ, koh. gur. sōṇṷ ʻ beautiful ʼ; K. sŏn m. ʻ gold ʼ, rām. sōnu, kash. pog. sŏnn, ḍoḍ. sŏṇṇā, S. sõnum. ʻ gold ʼ (sõnõ ʻ golden ʼ), L. sonā m., P. sonā, soinā, seonā, siūnā m., WPah.bhad. sunnō, khaś. sɔnnu n., jaun. sūnō, Ku. suno, gng. sun, N. sun, A. xon,xonā, B. sonā, Or. sunā, Mth. son, sonā, Aw.lakh. son

gāruḍa ʻ relating to Garuḍa ʼ MBh., n. ʻ spell against poison ʼ lex. 2. ʻ emerald (used as an antidote) ʼ Kālid. [garuḍá -- ]1. Pk. gāruḍa -- , °ula -- ʻ good as antidote to snakepoison ʼ, m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ, n. ʻ science of using such charms ʼ; H. gāṛrū, gārṛū m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ; M. gāruḍ n. ʻ juggling ʼ.2. M. gāroḷā ʻ cat -- eyed, of the colour of cat's eyes ʼ.(CDIAL 4138)

<karaD>(Z),,<kanaD>(Z) {N} ``^sheaf of ^straw''. #16160.

*gaḍḍa2 ʻ bundle, sheaf ʼ. 2. *giḍḍa -- .1. S. gaḏo m. ʻ bundle of grass &c. ʼ, °ḍ̠ī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; L. gaḍḍā m. ʻ armful of straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ sheaf ʼ; P. gaḍḍā m. ʻ handful of sticks ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ load of rice in straw ʼ, WPah. bhal. gaḍḍi f.(CDIAL 3982)

करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid.कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ n (Commonly करडूं ) A kid. (Marathi. Molesworth) Phal. grhēmiṇo m.,°ṇi f. ʻ kid one year old ʼ(CDIAL 4398) Or. gāraṛa, gaṛera, °ṛarā ʻ ram ʼ,gāraṛi ʻ ewe ʼ, garaṛa ʻ sheep ʼ;*gaḍḍa4 ʻ sheep ʼ. 2. gaḍḍara -- , °ḍala -- m. Apte. [Cf. gaḍḍārikā -- f. ʻ ewe in front of a flock ʼ lex., gaḍḍālikā<-> f. ʻ sheep ʼ → Psht.gaḍūrai ʻ lamb ʼ NTS ii 256]1. Ash. gaḍewä m. ʻ sheep ʼ, °wī f.; Wg. gáḍawā, goḍṓ ʻ ram ʼ, guḍsok ʻ lamb ʼ; Paš. giḍīˊ f. ʻ sheep ʼ; L. gaḍ m. ʻ wild sheep ʼ.2. Pk. gaḍḍarī -- f. ʻ goat, ewe ʼ, °riyā -- f. ʻ ewe ʼ; Woṭ. gaḍūre ʻ lamb ʼ; B. gāṛal, °ṛar ʻ the long -- legged sheep ʼ; H. gāḍar f. ʻ ewe ʼ; G. gāḍar, °ḍrũ n. ʻ sheep ʼ. -- Deriv. B. gāṛle ʻ shepherd ʼ, H. gaḍariyā m.gaḍḍara -- : S.kcch. gāḍar m. ʻ sheep ʼ.(CDIAL 3983) ګډوريَ gœḏḏo-raey, s.m. (1st) A lamb. Pl. يِ ī. ګډورئِي gœḏḏo-raʿī, s.f. (6th) An ewe lamb. Sing. and Pl. (Pushto)

<gaDra>(ZA) [gaDra],[gaDRa] {N} ``male ^goat(Z), male ^kid(A)''. *Des. #10090.

<lupu gadra>(A) {N} ``^billy ^goat''. |<lupu> `big'. ??d/D (cf. D below). #21082.

<kara beLO>(M) {N} ``^noon''. |<kara> `sunshine, heat of the sun'. %3812. #3772.

<hanuN>(P),,<aNu>(MP) {N} ``the Langur or Hanuman ^monkey''. *Sa.<hAR~u>, H.<henUmanA>, O.<hOnUmanO>; cf. So.<karu:-n>, Rog.<kra>, Mal.<kAra>. %12551. #12451.

<-kaD>(:) {NCF of <kaRaD>(P), <kaLaD>(M)} ``^crab''. *Kh.<khaGkRa>(B), ~<khaGkhaRa>(A), Sa.<kaTkom>, MuN<kaTkOm>, MuH<kaRkOm>, Ho<kaTkom>, ~<kaTO'b>, So.<k+nad/kad>; O.<kO~kOra>, ~<kOrkOTO>, H.<kekARa>, Sk.<kArkATA>; cf. <karOG> `fish', Kh.<kaDoG>, So.<Oyo:-n>, Sa.<hako>, MuN, Ho<haku>, MuH<hai>, Ku.<kaku>, cf. Pal.<ka:>, Nic.<ka:A>, Nic.Car<ka:'>. %15611. #15501.

Kh. kaGkaRa `crab'.Sa. kaTkOm `crab'.Mu. kaTkOm ~ kaRkOm `crab'.Ho kaTkom ~ kakom `crab'.Ku. katkom ~ kekade `crab'.@(V059a)<kara~it>(B) {NA} ``the ^krait, a kind of poisonous ^snake''. #15541.

<kaLasamOGgO>(M) {N} ``^lizard''. !But cf. <karsa mOGgO> !. %16400. #16280.

<kaLa-tutu-kaD>(M) {N} ``^scorpion''. |. %15635. #15525.+<-kaD>(:) {NCF of <kaRaD>(P), <kaLaD>(M)} ``^crab''. *Kh.<khaGkRa>(B), ~<khaGkhaRa>(A), Sa.<kaTkom>, MuN<kaTkOm>, MuH<kaRkOm>, Ho<kaTkom>, ~<kaTO'b>, So.<k+nad/kad>; O.<kO~kOra>, ~<kOrkOTO>, H.<kekARa>, Sk.<kArkATA>; cf. Ju.<tutukaD>; cf. <karOG> `fish', Kh.<kaDoG>, So.<Oyo:-n>, Sa.<hako>, MuN, Ho<haku>, MuH<hai>, Ku.<kaku>, cf. Pal.<ka:>, Nic.<ka:A>, Nic.Car<ka:'>. ??#.

<tutu-kaD>(P) {N} ``^crab''. |. %15624. #15514.

<kaLa-tutu-kaD>(M) {N} ``^scorpion''. |. %15636. #15526.

<kaDu>(MP),,<kODu>(:) {N} ``^bracelet, ^wristlet, ^bangle''. Cf. <gaDua>. *So.<kaddu:-n>, Kh.<karam>(D), ~<kaRam>(AB) `wrist [D], bracelet [ABD]', H.<kARa> `bangle', O.<kORa>, Guj.<kADU~>, cf. Kh.<kaDu'-> `to embrace'. %15721. #15611. <kaDu iti>(P) {N} ``^wrist''. |<iti> `hand'. *$So.<kaddu-si>. %13843. #13743. <kODu>(:),,<kaDu>(MP) {N} ``^bracelet, ^wristlet, ^bangle''. Cf. <gaDua>. *So.<kaddu:-n>, Kh.<karam>(D), ~<kaRam>(AB) `wrist [D], bracelet [ABD]', H.<kARa> `bangle', O.<kORa>, Guj.<kADU~>, cf. Kh.<kaDu'-> `to embrace'. %17781. #17651. <kaDu iti>(P) {N} ``^wrist''. |<iti> `hand'. *$So.<kaddu-si>. %13844. #13744. <kODu maLi>(M) {N} ``^ornaments, lit. ^bracelet (and) ^necklace''. |<maLi> `necklace'. %15733. #15623.<karam>(D),,<kaRam>(AB) {NI} ``^bangle, wrist or ankle ^bracelet''. *@. ??VAR. #15571.

kará1 ʻ doing, causing ʼ AV., m. ʻ hand ʼ RV. [√kr̥ 1 ] Pa. Pk. kara -- m. ʻ hand ʼ; S. karu m. ʻ arm ʼ; Mth. kar m. ʻ hand ʼ (prob. ← Sk.); Si. kara ʻ hand, shoulder ʼ, inscr. karā ʻ to ʼ < karāya. -- Deriv. S. karāī f. ʻ wrist ʼ; G. karã̄ n. pl. ʻ wristlets, bangles ʼ.(CDIAL 2779).

<kOrOtO>(P),,<kOrta>(K) {N} ``^saw''. *Sa., Ho, Sad., ~<kOrOt>, H.<kAra~tA>, B.<kOratO>, O.<kOrOtO>, Sk.<kArApAttrA>. %18951. #18811.

<kaRasa>(P) {N} ``an earthen ^pot, a small earthen ^pitcher''. *H.<kArAcha> `a large-bowled spoon or ladle', O.<kOLOsI> `pitcher'. %16431. #16311.

karaka1 m. ʻ water vessel ʼ MBh.Pa. karaka -- m., Pk. karaya -- m., kariā -- f. ʻ cup for serving spirituous liquor ʼ; Paš. karā ʻ a well ʼ IIFL iii 3, 96; Bi. karaī ʻ spouted water vessel ʼ; H. karaīf. ʻ small earthen pipkin ʼ. -- With -- uka -- (cf. gaḍḍuka -- ): P. Ku. karuā ʻ spouted water vessel ʼ; N. karuwā ʻ small brass waterpot with a spout ʼ; Bi. karwāʻ pot for pouring water on plaster ʼ; Mth. karwā ʻ waterpot with a spout ʼ, H. karuā. -- Bi. Mth. karnā ʻ earthen vessel for milk or curds ʼ; -- M. karhā m. ʻ waterpot (esp. that used in the marriage ceremony) ʼ.(CDIAL 2781)

<karahi>(B),,<kaRahi>(B) {NI} ``^frying_^pan''. *@. ??VAR. #15491.

<kaRia>(K),,<kaLia>(MP) {ADJ} ``^black; ^dirty''. *Sad.<kArIya>, H.<kala>, O.<kOLa>, Sk.<kalA>. %16461. #16341. <kaLia-rai>(P) {ADJ} ``^spotted''. |<-rai> ??. %15982. #15872.

<kaLia-mOD>(M) {NB} ``^pupil (of ^eye)''. |<-moD> `eye'. %10174. #10094.

káraṇḍa1 m.n. ʻ basket ʼ BhP., °ḍaka -- m., °ḍī -- f. lex.Pa. karaṇḍa -- m.n., °aka -- m. ʻ wickerwork box ʼ, Pk. karaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m. ʻ basket ʼ, °ḍī -- , °ḍiyā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; K. kranḍa m. ʻ large covered trunk ʼ, kronḍu m. ʻ basket of withies for grain ʼ, krünḍü f. ʻ large basket of withies ʼ; Ku. kaṇḍo ʻ basket ʼ; N. kaṇḍi ʻ basket -- like conveyance ʼ; A. karṇi ʻ open clothes basket ʼ; H. kaṇḍī f. ʻ long deep basket ʼ; G. karãḍɔ m. ʻ wicker or metal box ʼ, kãḍiyɔ m. ʻ cane or bamboo box ʼ; M. karãḍ m. ʻ bamboo basket ʼ,°ḍā m. ʻ covered bamboo basket, metal box ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Si. karan̆ḍuva ʻ small box or casket ʼ. -- Deriv. G. kãḍī m. ʻ snake -- charmer who carries his snakes in a wicker basket ʼ.(CDIAL 2792)

Pk. karaḍa -- m. ʻ crow ʼ, °ḍā -- f. ʻ a partic. kind of bird ʼ; S. karaṛa -- ḍhī˜gu m. ʻ a very large aquatic bird ʼ; L. karṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ the common teal ʼ.(CDIAL 2787)

, n. < karaṭa. 1. Crow; காக்கை. (பிங்.)கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n. < karaṇḍa. 1. Water-crow, coot; நீர்க்காக்கை. கரண்டமாடு பொய் கை (திவ். திருச்சந்த. 62)(Tamil)

*karaṭataila ʻ oil of safflower ʼ. [

करडणें or करंडणें (p. 137) [ karaḍaṇē or ṅkaraṇḍaṇēṃ ] v c To gnaw or nibble; to wear away by biting.(Marathi)

Pa. karaṇīya -- n. ʻ duty, business ʼ, Pk. karaṇīa -- , °ṇijja -- ; S. karṇī f. ʻ work, act ʼ, P. karnī f., Ku. karṇī; N. karni ʻ act, exp. the sexual act ʼ; Or. karaṇī ʻ work, authority ʼ; H. karnī f. ʻ act ʼ, G. karṇī f.; M. karṇī f. ʻ incantation ʼ.

Addenda: karaṇīya -- : WPak.kṭg. kɔrn

Pa. karaṇḍa -- m.n., °aka -- m. ʻ wickerwork box ʼ, Pk. karaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m. ʻ basket ʼ, °ḍī -- , °ḍiyā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; K. kranḍa m. ʻ large covered trunk ʼ,kronḍ

karaṇḍa --

கரண்டை¹ karaṇṭai. A mode in the flight of birds; பறவையின் கதிவிசேடம். (காசிக. திரிலோ. 6.).(Tamil)

M. karaḍ āḍuḷsā m. ʻ a species of Justicia picta ʼ.

Pa. karapālikā -- f. ʻ wooden sword, cudgel ʼ; Pk. karavāla -- m. ʻ sword ʼ; Bi. karuār ʻ paddle ʼ; H. karwāl, karuār, karwār, °rā m. ʻ oar, rudder, sword ʼ; G.karvāl f., °lũ n. ʻ sword ʼ with l, not ḷ.

kárṇa m. ʻ ear, handle of a vessel ʼ RV., ʻ end, tip (?) ʼ RV. ii 34, 3. [Cf. *kāra -- 6 ]

Pa. kaṇṇa -- m. ʻ ear, angle, tip ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇa -- , °aḍaya<-> m. ʻ ear ʼ, Gy. as. pal. eur. kan m., Ash. (Trumpp) karna NTS ii 261, Niṅg. kō̃, Woṭ. kanə, Tir.kana; Paš. kan, kaṇ(ḍ) -- ʻ orifice of ear ʼ IIFL iii 3, 93; Shum. kō̃ṛ ʻ ear ʼ, Woṭ. kan m., Kal. (LSI) kuṛō̃, rumb. ku ŕũ, urt. kŕãdotdot; (< *kaṇ), Bshk. kan, Tor.k*l ṇ, Kand. kōṇi, Mai. kaṇa, ky. kān, Phal. kāṇ, Sh. gil. ko̯n pl. ko̯ṇí m. (→ Ḍ kon pl. k*l ṇa), koh. kuṇ, pales. kuāṇə, K. kan m., kash. pog. ḍoḍ. kann, S. kanum., L. kann m., awāṇ. khet. kan, P. WPah. bhad. bhal. cam. kann m., Ku. gng. N. kān; A. kāṇ ʻ ear, rim of vessel, edge of river ʼ; B. kāṇ ʻ ear ʼ, Or. kāna, Mth. Bhoj. Aw. lakh. H. kān m., OMarw. kāna m., G. M. kān m., Ko. kānu m., Si. kaṇa, kana. -- As adverb and postposition (ápi kárṇē ʻ from behind ʼ RV.,karṇē ʻ aside ʼ Kālid.): Pa. kaṇṇē ʻ at one's ear, in a whisper ʼ; Wg. ken ʻ to ʼ NTS ii 279; Tir. kõ ʻ on ʼ AO xii 181 with (?); Paš. kan ʻ to ʼ; K. kȧni with abl. ʻ at, near, through ʼ, kani with abl. or dat. ʻ on ʼ, kun with dat. ʻ toward ʼ; S. kani ʻ near ʼ, kanã̄ ʻ from ʼ; L. kan ʻ toward ʼ, kannũ ʻ from ʼ, kanne ʻ with ʼ, khet.kan, P. ḍog. kanē ʻ with, near ʼ; WPah. bhal. k*l ṇ, °ṇi, ke ṇ, °ṇi with obl. ʻ with, near ʼ, kiṇ, °ṇiã̄, k*l ṇiã̄, ke ṇ° with obl. ʻ from ʼ; Ku. kan ʻ to, for ʼ; N. kana ʻ for, to, with ʼ; H.kane, °ni, kan with ke ʻ near ʼ; OMarw. kanai ʻ near ʼ, kanã̄ sā ʻ from near ʼ, kã̄nī˜ ʻ towards ʼ; G. kane ʻ beside ʼ.kárṇaka -- , kárṇikā -- , karṇín -- ; karṇakaṇḍū -- , *karṇakāṣṭhaka -- , *karṇakīla -- , karṇadhāra -- , karṇapattraka -- , karṇapuṭa -- , *karṇapuṣya -- , *karṇamarda -- , karṇamūla -- , *karṇavaṭikā -- , karṇavēdha -- , *karṇavyādhikā -- , karṇaśūlá -- , *karṇasphōṭikā -- , *karṇākṣi -- ; ākarṇayati, utkarṇa -- ; ajakarṇa -- , gōkarṇa -- , catuṣkarṇa -- , lambakarṇa -- . S.kcch. kann m. ʻ ear ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) kān, poet. kanṛu m. ʻ ear ʼ, kṭg. kanni f. ʻ pounding -- hole in barn floor ʼ; J. kā'n m. ʻ ear ʼ, Garh. kān; Md. kan -- in kan -- fat ʻ ear ʼ (CDIAL 2830)

Pa. kaṇṇa -- m. ʻ ear, angle, tip ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇa -- , °aḍaya<-> m. ʻ ear ʼ, Gy. as. pal. eur. kan m., Ash. (Trumpp) karna NTS ii 261, Niṅg. kō̃, Woṭ. kanə, Tir.kana; Paš. kan, kaṇ(ḍ) -- ʻ orifice of ear ʼ IIFL iii 3, 93; Shum. kō̃ṛ ʻ ear ʼ, Woṭ. kan m., Kal. (LSI) kuṛō̃, rumb. k

kárṇikā f. ʻ round protuberance ʼ Suśr., ʻ pericarp of a lotus ʼ MBh., ʻ ear -- ring ʼ Kathās. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇikā -- f. ʻ ear ornament, pericarp of lotus, corner of upper story, sheaf in form of a pinnacle ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇiā -- f. ʻ corner, pericarp of lotus ʼ; Paš. kanīˊ ʻ corner ʼ; S. kanī f. ʻ border ʼ, L. P. kannī f. (→ H. kannī f.); WPah. bhal. kanni f. ʻ yarn used for the border of cloth in weaving ʼ; B. kāṇī ʻ ornamental swelling out in a vessel ʼ, Or. kānī ʻ corner of a cloth ʼ; H. kaniyã̄ f. ʻ lap ʼ; G. kānī f. ʻ border of a garment tucked up ʼ; M. kānī f. ʻ loop of a tie -- rope ʼ; Si.käni, kän ʻ sheaf in the form of a pinnacle, housetop ʼ.(CDIAL 2849)

karṇadhāra m. ʻ helmsman ʼ Suśr. [kárṇa -- , dhāra -- 1 ]Pa. kaṇṇadhāra -- m. ʻ helmsman ʼ; Pk. kaṇṇahāra -- m. ʻ helmsman, sailor ʼ; H. kanahār m. ʻ helmsman, fisherman ʼ.(CDIAL 2836)

kṣārá1 ʻ corrosive ʼ R., m. ʻ alkali ʼ Yājñ., n. ʻ any cor- rosive substance ʼ lex. [NIA. ch forms mean ʻ ashes ʼ, kh forms mostly ʻ alkali ʼ. -- ~jhāla -- 2 : √kṣai ]Pa. khāra -- m. ʻ alkali, potash ʼ, °raka -- ʻ sharp or dry ʼ, °rika -- ʻ alkaline ʼ; Pk. khāra -- ʻ biting, alkaline ʼ, khāra -- , chāra -- , °aya m. ʻ alkali, ashes ʼ; Gy. eur. čar, SEeur. čhar ʻ ashes ʼ, rum. čar ʻ sand ʼ, as. čar ʻ dust ʼ; Tir. čār ʻ earth, dust ʼ, K. khāra ʻ saline ʼ ← Ind.; S. khāru f. ʻ alkali ʼ, °ro ʻ brackish ʼ,chāru f. ʻ ashes ʼ (gender after vārī ʻ sand ʼ?); L. khār f. ʻ potash, the plant Salsola griffithsii (from which it is made) ʼ, °rā ʻ brackish ʼ; P. khār m. ʻ alkali ʼ,°rā ʻ brackish ʼ; P. WPah. jaun. Ku. chār m. ʻ ashes ʼ; Ku. gng. khār ʻ anger, ashes ʼ; N. khār ʻ alkali, pungent fumes from burning ghee ʼ, chār ʻ pungent fumes ʼ; A. khār ʻ potash ʼ, sār -- khār ʻ destroyed ʼ; B. khālāṛi ʻ salt factory ʼ, chār ʻ ashes ʼ, chār -- khār ʻ reduced to ashes, destroyed ʼ; Or. khāra ʻ potash, ashes of dried bark, ashes ʼ, khāri, °riā ʻ saline ʼ, chāra -- khāra ʻ reduced to ashes ʼ; Bi. khārī ʻ land impregnated with sodium sulphate ʼ, Mth. kharwā ʻ id. ʼ, khariā ʻ saline ʼ, chāro ʻ weeds burnt as manure ʼ; Bhoj. khār ʻ caustic alkali ʼ, chār ʻ ashes ʼ; OAw. khārā ʻ bitter ʼ, chāra f. ʻ ashes ʼ; H. khār m. ʻ alkali, saltness ʼ, °rā, °rī, °rū ʻ alkaline ʼ, °rī f. ʻ salt water ʼ, chār ʻ caustic ʼ, f. ʻ alkali, ashes ʼ, chārā m. ʻ id. ʼ, non -- chār m. ʻ brine ʼ; Marw. khāro ʻ bitter ʼ; OG.khāra m. ʻ envy ʼ, G. khār m. ʻ salt ʼ, °rũ ʻ saline ʼ, °rɔ m. ʻ carbonate of soda ʼ, °rī f. ʻ salt (from boiling sea -- water) ʼ; M. khār m. ʻ alkali ʼ, °rā ʻ saline ʼ; Ko. khāru ʻ salt ʼ; Si. kara ʻ salt (of water), infertile (of land) ʼ. -- X khára -- 2 q.v.

*kṣārakūṭa -- , *kṣāradhānikā -- , *kṣāramr̥tti -- ; *utkṣāra -- ; ṭaṅkaṇakṣāra -- , yavakṣāra -- .

Addenda: kṣārá --1 : S.kcch. khāro m. ʻ saline earth (for washing clothes) ʼ, adj. ʻ salty, pungent, bitter ʼ; WPah.kṭg. ċhāˊr m. ʻ ashes ʼ, J. chā'r f., Garh.khāru, chār ← H.; <-> OP. pāchāru m. ʻ dust under the feet ʼ (< *pādakṣāra -- ) C. Shackle.(CDIAL 3674).

*

Addenda: kṣārá --

khaḍaka ʻ *erect ʼ, m. ʻ bolt, post ʼ KātyŚr. 2. *khaḍati ʻ stands ʼ. 3. *khāḍayati ʻ makes stand ʼ. [Cf. khadáti ʻ is firm ʼ Dhātup.] and *khalati 2 1. K. khoru ʻ standing ʼ, ḍoḍ. khaṛo ʻ up ʼ, pog. khaṛkhuṛ ʻ erect ʼ; S. khaṛo ʻ standing erect ʼ, P. khaṛā, WPah. paṅ. khaṛā, bhad. khaṛo, Or. B. khāṛā, H.khaṛā (→ N. khaṛā), Marw. khaṛo, G. khaṛũ; M. khaḍā ʻ standing, constant ʼ.

2. K. pog. khaṛnu ʻ to stand ʼ, rām. khaṛōnu, ḍoḍ. khaṛōnō; WPah. bhal. caus. khaṛēṇu ʻ to fix ʼ; -- G. khaṛakvũ ʻ to make a heap ʼ. 3. K. khārun ʻ to make ascend, lift up ʼ.*khaḍati ʻ stands ʼ see khaḍaka -- .Addenda: khaḍaka -- : WPah.kṭg. khɔ́ṛɔ ʻ erect, upright ʼ; khɔ́ṛhnõ, kc. khɔṛiṇo ʻ to stand, rise ʼ, J. khaṛuwṇu.(CDIAL 3784)

khaḍū1 m. ʻ bier ʼ lex. 2. khaṭṭi -- m. lex. [Cf. kháṭvā -- ] 1. B. khaṛu ʻ bier ʼ.2. B. khāṭi ʻ bier ʼ, Or. khāṭa.(CDIAL 3785)

*pratikkhara ʻ harsh against ʼ. [khara -- 2 with anal. -- kkh -]

Pk. paḍikkhara -- ʻ cruel ʼ; M. paḍkhar ʻ rude ʼ (LM 361 with misprint paḍikkhāra

wrongly < *pratikṣāra -- ).(CDIAL 8549) prakṣara m. ʻ iron armour for horse or elephant ʼ lex., pra(k) khara -- m. lex. [Sanskritization of MIA. pakkhara<-> < *praskara -- , cf.prakīrṇa -- m. ʻ horse ʼ lex. (< ʻ saddled, accoutred ʼ?); LM 364 < upaskara -- . -- √kr̥ 1 ]Pa. pakkhara -- m. ʻ bordering or trimming (of a carriage) ʼ; Pk. pakkhara -- m., °rā -- f. ʻ horse -- armour ʼ; S. pakhara f. ʻ dress given by faqir to layman ʼ; H. pākhar m. ʻ armour for elephant or horse ʼ (→ P. L. pākhar m. ʻ saddle with its gear ʼ); G. pākhar f. ʻ net of flowers for bed -- cover, horse -- armour ʼ (whence pākhariyɔ m. ʻ a species of horse ʼ); M. pākhar f. ʻ caparison of a horse ʼ.(CDIAL 8452)

*kharabhaka ʻ hare ʼ. [ʻ longeared like a donkey ʼ: khara -- 1 ?]N. kharāyo ʻ hare ʼ, Or. kharā, °riā, kherihā, Mth. kharehā, H. kharahā m(CDIAL 3823) ``^rabbit'':Sa. kulai `rabbit'.Mu. kulai `rabbit'.KW kulai @(M063)

The casting of the bronze drums of Dong Son is a complex process requiring high order of techniques and artistic skills.

![]() It was first necessary to produce a hollow clay core to minimise weight and ease its manipulation.

It was first necessary to produce a hollow clay core to minimise weight and ease its manipulation.

![]() Separate clay pattern moulds would then be prepared, circular for the tympanum and rectangular for sections of the mantle.

Separate clay pattern moulds would then be prepared, circular for the tympanum and rectangular for sections of the mantle. ![]()

![]() The surface of the clay received ornamentation in more than one way. It could be impressed with a patterned old to create the panels of geometric ornament, or for more individual motifs or decorative elements, it could be incised with a stylus.

The surface of the clay received ornamentation in more than one way. It could be impressed with a patterned old to create the panels of geometric ornament, or for more individual motifs or decorative elements, it could be incised with a stylus.

![]() This pattern old would then have been filled with molten wax, such that the wax filled and duplicated the chosen decor.

This pattern old would then have been filled with molten wax, such that the wax filled and duplicated the chosen decor.

![]() It would then have been necessary to transfer the sheets of cooled wax to the clay core, having first place the bronze spacers strategically into the wax until they reach the surface of the pattern old.

It would then have been necessary to transfer the sheets of cooled wax to the clay core, having first place the bronze spacers strategically into the wax until they reach the surface of the pattern old.

![]() This procedure resulted, in effect, a wax drum over a clay core.

This procedure resulted, in effect, a wax drum over a clay core.

![]() Investment of the wax in a layer of very fine clay followed before the assemblage was covered in a coarse clay coat. It was then necessary to melt out the wax, and preheat the clay old. The critical point was then reached for the pour, in the case of larger examples, of nearly 100 kg of molten bronze into the conduits to reproduce in metal the wax image of the drum.

Investment of the wax in a layer of very fine clay followed before the assemblage was covered in a coarse clay coat. It was then necessary to melt out the wax, and preheat the clay old. The critical point was then reached for the pour, in the case of larger examples, of nearly 100 kg of molten bronze into the conduits to reproduce in metal the wax image of the drum.

References: The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Charles Higham, 1996

It was first necessary to produce a hollow clay core to minimise weight and ease its manipulation.

It was first necessary to produce a hollow clay core to minimise weight and ease its manipulation.  Separate clay pattern moulds would then be prepared, circular for the tympanum and rectangular for sections of the mantle.

Separate clay pattern moulds would then be prepared, circular for the tympanum and rectangular for sections of the mantle.

The surface of the clay received ornamentation in more than one way. It could be impressed with a patterned old to create the panels of geometric ornament, or for more individual motifs or decorative elements, it could be incised with a stylus.

The surface of the clay received ornamentation in more than one way. It could be impressed with a patterned old to create the panels of geometric ornament, or for more individual motifs or decorative elements, it could be incised with a stylus.  This pattern old would then have been filled with molten wax, such that the wax filled and duplicated the chosen decor.

This pattern old would then have been filled with molten wax, such that the wax filled and duplicated the chosen decor.  It would then have been necessary to transfer the sheets of cooled wax to the clay core, having first place the bronze spacers strategically into the wax until they reach the surface of the pattern old.

It would then have been necessary to transfer the sheets of cooled wax to the clay core, having first place the bronze spacers strategically into the wax until they reach the surface of the pattern old.  This procedure resulted, in effect, a wax drum over a clay core.

This procedure resulted, in effect, a wax drum over a clay core.  Investment of the wax in a layer of very fine clay followed before the assemblage was covered in a coarse clay coat. It was then necessary to melt out the wax, and preheat the clay old. The critical point was then reached for the pour, in the case of larger examples, of nearly 100 kg of molten bronze into the conduits to reproduce in metal the wax image of the drum.

Investment of the wax in a layer of very fine clay followed before the assemblage was covered in a coarse clay coat. It was then necessary to melt out the wax, and preheat the clay old. The critical point was then reached for the pour, in the case of larger examples, of nearly 100 kg of molten bronze into the conduits to reproduce in metal the wax image of the drum. References: The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Charles Higham, 1996

In contrast to most other drums of the Dong Son, the tympanum bears three concentric panels, which depict animals or humans, interleaved with bands of geometric or circular patterns. The innermost panel appears to be a self-referencing depiction, as it is decorated with pictures of humans who appear to be performing a ceremony involving the drums themselves. Other musical instruments and rice growing and harvesting activities are also shown. The two outer panels are decorated with scenes of deer, hornbills and crane egrets.

The inner panel repeats itself, despite the presence of minor variations. The scenes are the subject of multiple interpretations, but a prominent motif is that of a row of figures who appear to be male. They are plumed, and led by a man holding a spear that is directed towards the ground. He is followed in the line by five more men, at least two of whom appear to playing musical instruments. One appears to be playing a khen and either cymbals or bells, while another holds a wand-like object in his left hand. The men are wearing a type of kilt and highly feathered headgear, which includes a figure in the shape of a bird's head.

There is also a scene where one standing person and three seated people are brandishing long poles that appear to be used to strike a row of drums placed in front of them. This scene is repeated with a few variations. In one scene the drums are all of identical size, while in the others their sizes are sequenced. One percussionist uses one striking device, while another uses two for each hand. There are further variations of this scene with seated and standing percussionists.Ahead of the leader, there is some sort of a structure that is supported by stilts with either decorated timber walls or some sort of streamers held at the eaves. A board of gongs is being percussed by a person wearing a kilt, but is not wearing a feathered headdress. Three people depicted beyond the house also do not have any headwear, with two having long hair and another with bun-tied hair. Two of the people are depicted threshing rice with a pole ornamented with feathers, while the other is shooing away a hornbill. A house is depicted beyond them which has decorated posts erected at a sharp angle, close to vertical, which is decorated with what appears to be feathers or streamers. The ends of the gables are further decorated with birds' heads. There are three people depicted inside the house, possibly playing percussion instruments.

Archaeologists are agreed that the scene is likely to depict a festival or ritual of some kind, with the musicians appearing to be part of a parade. The feathered men contrast with those depicted in the house, who have unkempt hair and appear to be female. The decoration on the mantle of the drum depicts plumed warriors in a procession of elegant pirogues with decorated timbers. Birds' heads are found on their headgear, the ends of their water transport vessels and even the rudder. (Higham, Charles (1996). The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia. Cambridge World Archaeology, p.124)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%E1%BB%8Dc_L%C5%A9_drum

Annex A: Excerpt from Le Minh Kha's SE Asian History Blog

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2015/01/10/sexual-intercourse-water-buffalos-elephants-daggers-and-dong-son-culture/

Annex B: New Light On A Forgotten Past By Wilhelm G. Solheim II, Ph.D. Professor Of Anthropology, University Of Hawaii Posted on 25 Oct 2007

For purposes of prehistory, what we usually think of as Southeast Asia must be expanded somewhat to include related cultures. Prehistoric Southeast Asia, as I use the term, consists of two parts. The first is "Mainland Southeast Asia," which extends from the Ch'in Ling Mountains, north of the Yangtze River in China, to Singapore, and from the South China Sea westward through Burma into Assam. The other I call "Island Southeast Asia," an are from the Andaman Islands, south of Burma, around to Taiwan, including Indonesia and the Philippines...

![]() Robert Heine-Geldern, an Austrian anthropologist, published in 1932 the traditional outline of Southeast Asian prehistory. He suggested a series of "waves of culture" that is, human migrations--which brought to Southeast Asia the major peoples who are found there today.

Robert Heine-Geldern, an Austrian anthropologist, published in 1932 the traditional outline of Southeast Asian prehistory. He suggested a series of "waves of culture" that is, human migrations--which brought to Southeast Asia the major peoples who are found there today.

His most important wave --people who made a rectangular stone tool called an adz-- came from northern China into Southeast Asia, he said, and spread from there through the Malay Peninsula into Sumatra and Java, and then to Borneo, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan.

Later, Heine-Geldern dealt with the coming of bronze to Southeast Asia. He theorized that the original source of the Southeast Asian Bronze Age was a migration from eastern Europe about 1000 B.C. The people in this migration, he believed, moved east and south, entering China during the Western Chou Dynasty (1122-771 B.C.). They carried with them not only a knowledge of bronze working but also a new art form. That is, they decorated their bronze with geometric patterns, spirals, triangles, and rectangles, as well as with scenes or pictures of people and animals.

As applied to Southeast Asia, both Heine-Geldern and Bernhard Karlgren, a Swedish scholar, called this culture Dong Son, after Dong Son, a site in North Viet Nam south of Hanoi, where large bronze drums and other artifacts had been unearthed. Both men felt that the Dong Son people brought bronze and the geometric art style into Southeast Asia.

Prehistorians, for the most part, have followed this traditional reconstruction, but there were some facts that did not quite jibe. A few botanists who studied the origins of domesticated plants, for example, suggested that Southeast Asia had been a center of very early plant domestication.

In 1952 Carl Sauer, a U.S. geographer, went a step further. He hypothesized that the first plant domestication in the world took place in Southeast Asia. He speculated that it was brought about by people much earlier than the Dong Son period, people whose primitive culture was known as Hoabinhian. Archeologists did not immediately take up Sauer's theory.

Dams Add an Element of Urgency

The existence of a Hoabinhian culture had first been proposed in the 1920's by Madeleine Colani, a French botanist turned paleontologist and then archeologist. She based the idea on excavations of several cave and rock-shelter sites in North Viet Nam, the first of which was found near the village of Hoa Binh.

Typical artifacts in these sites included oval, circular, or roughly triangular stone tools flaked on only one side, leaving the original surface of the rock on the other. Neat grinding stones were found in most sites, and many stone flakes. Upper levels usually held pottery and a few somewhat different stone tools, with the working end ground to a sharp edge. Animal bones and large quantities of shell were usually present.

Archeologists felt that the pottery was associated accidentally with the Hoabinhian tools and had been made by more advanced people living nearby, possibly farmers who had migrated from the north. They also felt that the edge grinding of the stone tools had been learned from these outsiders. But no sites of tile northern farmers have ever been found.

...

Puzzle Begins to Fit Together

In view of the new excavations and dates I have summarized here, and others, perhaps equally important, that I have not, it is interesting to speculate on how the prehistory of Southeast Asia may someday be reconstructed. In a number of published papers I have made a start on this. Most of the ideas I have proposed must be labeled as hypothesis or conjecture. They need a great deal more research to bear them out--or refute them. Among them are these:

* I agree with Sauer that the first domestication of plants in the world was done by people of the Hoabinhian culture, somewhere in Southeast Asia. It would not surprise me if this had begun as early as 15,000 B.C.E

* I suggest that the earliest dated edge-ground stone tools, found in northern Australia and dated by carbon 14 at about 20,000 B.C.E, are of Hoabinhian origin.

* While the earliest dates for pottery now known are from Japan at about 10,000 B.C., I expect that when more of the Hoabinhian sites with cord-marked pottery are dated, we will find that pottery was being made by these people well before 10,000 B.C.E, and was possibly invented by them.

* The traditional reconstruction of Southeast Asian prehistory has had migrations from the north bringing important developments in technology to Southeast Asia. I suggest instead that the first neolithic (that is, late Stone Age) culture of North China, known as the Yangshao, developed out of a Hoabinhian subculture that moved north from northern Southeast Asia about the sixth or seventh millennium B.C.E

* I suggest that the later so-called Lungshan culture, which supposedly grew from the Yangshao in North China and then exploded to the east and southeast, instead developed in South China and moved northward. Both of these cultures developed out of a Hoabinhian base.

* Dugout canoes had probably been used on the rivers of Southeast Asia long before the fifth millennium B.C. Probably not long before 4000 B.C. the outrigger was invented in Southeast Asia, adding the stability needed to move by sea. I believe that movement out of the area by boat, beginning about 4000 B.C., led to accidental voyages from Southeast Asia to Taiwan and Japan, bringing to Japan tare cultivation and perhaps other crops.

* Sometime during the third millennium B.C. the now-expert boat-using peoples of Southeast Asia were entering the islands of Indonesia and the Philippines. 'They brought with them a geometric art style--spirals and triangles and rectangles in band patterns-that was used in pottery, wood carvings, tattoos, bark cloth, and later woven textiles. These are the same geometric art motifs that were found on Dong Son bronzes and hypothesized to have come from eastern Europe. ? The Southeast Asians also moved west, reaching Madagascar probably around 2,000 years ago. It would appear that they contributed a number of important domesticated plants to the economy of eastern Africa.

* At about the same time, contact began between Viet Nam and the Mediterranean, probably by sea as a result of developing trade. Several unusual bronzes, strongly suggesting eastern Mediterranean origins, have been found at the Dong Son site.

Past May Help to Light Up the Present

The new reconstruction of Southeast Asian prehistory I have presented here is based on data from only a very few sites and a reinterpretation of old data. Other interpretations are possible. Many more well-excavated, welldated sites are needed just to see if this general framework is any closer to what happened than is Heine-Geldern's reconstruction. Burma and Assam are virtually unknown prehistorically, and I suspect that they are of great importance in Southeast Asian prehistory.

Most needed are many more details about small, definable areas. By intensive investigation in a small area, it will be possible to work out the local cultural development and ecological adaptation to see how living people fit in with the framework of prehistory. After all, it is people we want to understand, and this information may give us some insight into their interaction with each other and with their changing world in Southeast Asia.[unquote]

https://www.scribd.com/doc/264221581/Distribution-of-bronze-drums-of-the-Heger-I-and-Pre-I-types-temporal-changes-and-historical-background-Keiji-Imamura-2010

Bronze figurine, Đông Sơn culture, 500 BC-300 AD. Thailand.

Annex A: Excerpt from Le Minh Kha's SE Asian History Blog

Sexual Intercourse, Water Buffalos, Elephants, Daggers

and Đông Sơn Culture

10 jan 15

So I visited the History Museum in Hanoi a few weeks ago where they currently have a small (but wonderful) exhibit marking 70 years since the discovery of the first Đông Sơn artifacts.

On the one hand, it was fantastic to be able to stand next to a bronze drum and to examine it closely.

On the other hand, as I looked closely at some of the artifacts on display, I felt as if I had been betrayed by the scholars who have written about Đông Sơn culture, as there is obviously so much more to say about Đông Sơn culture than scholars have discussed to date.

For instance, while apparently some scholars have noted that there are images of people engaging in sexual intercourse on some Đông Sơn bronze artifacts, I never realized that those images were on burial jars.

This is incredibly significant because this links the Đông Sơn culture to a larger (non-Việt) world, as in as late as the twentieth century (and perhaps today as well) Austronesian-language speakers like the Jarai placed similar images on their tombs.

Another image that surprised me was the presence of water buffalo on bronze drums.

A great deal has been written about the images of birds on bronze drums, and numerous Vietnamese scholars have argued that these birds represent the “totem” of the “Lạc” people, a people whom Vietnamese scholars claim were the original inhabitants of the Red River delta. But there are water buffalo on bronze drums too, so why don’t people talk about the water buffalo as a totem of the “Lạc” people?

I was also surprised to find beautiful bells.

The elephant image on this bell is exquisite.

The Chinese characters on this bell, meanwhile, lead to interesting questions.

As Han Xiaorong pointed out years ago, Vietnamese and Chinese scholars have spent much of the past half century claiming that the bronze drums (and by extension, Đông Sơn culture) were “Vietnamese” or “Chinese” (“Who Invented the Bronze Drum? Nationalism, Politics, and a Sino-Vietnamese Archaeological Debate of the 1970s and 1980s,” Asian Perspectives, 43.1 (2004): 7-33.). The historical reality, however does not match current national borders.

The couple engaging in sexual intercourse on a funerary jar, the water buffalo, the elephant, and Chinese writing all indicate this. Instead, what we find on bronze objects in the area stretching from the Yangzi to the Cả River is evidence of an elite cultural world where members of the elite across this vast region interacted and exchanged objects (and perhaps ideas) with each other.

This article by Wei Weiyan, Shiung Chung-Ching- “Viet Khe Burial 2: Identifying the Exotic Bronze Wares and Assessing Cultural Contact between the Dong Son and Yue Cultures,” Asian Archaeology 2 (2014): 77-92 – makes this point.

These authors find that there are objects in a tomb in an area near what is today Hải Phòng that clearly came from areas to the north, but that one can also find a dagger like those in the images above and below that was representative of the Đông Sơn culture that has been found in a tomb in Hunan.

So what all of this indicates is that there was a world in the first millennium BC that was sophisticated, but which was neither “Vietnamese” nor “Chinese” and which was not the “origin” of “Vietnamese” or “Chinese” history.

It is a past world that has disappeared. While we can never fully recover that past world, we can still learn a lot about it if we put aside the need to find “Vietnamese” or “Chinese” history at this time, and if we just look at the water buffalos, the elephants, the daggers and the people engaging in sexual intercourse on their own terms. See Annex A: Excerpt from Le Minh Kha's SE Asian History Blog which discusses the presence of buffalo, elephant and explicit sexual intercourse hieroglyphs which are also explained in the context of Meluhha metalwork catalogs of Indus Script Corpora.

Annex B: New Light On A Forgotten Past By Wilhelm G. Solheim II, Ph.D. Professor Of Anthropology, University Of Hawaii Posted on 25 Oct 2007

[quote]Migrating Peoples and "Waves of Culture"

For purposes of prehistory, what we usually think of as Southeast Asia must be expanded somewhat to include related cultures. Prehistoric Southeast Asia, as I use the term, consists of two parts. The first is "Mainland Southeast Asia," which extends from the Ch'in Ling Mountains, north of the Yangtze River in China, to Singapore, and from the South China Sea westward through Burma into Assam. The other I call "Island Southeast Asia," an are from the Andaman Islands, south of Burma, around to Taiwan, including Indonesia and the Philippines...

Robert Heine-Geldern, an Austrian anthropologist, published in 1932 the traditional outline of Southeast Asian prehistory. He suggested a series of "waves of culture" that is, human migrations--which brought to Southeast Asia the major peoples who are found there today.

Robert Heine-Geldern, an Austrian anthropologist, published in 1932 the traditional outline of Southeast Asian prehistory. He suggested a series of "waves of culture" that is, human migrations--which brought to Southeast Asia the major peoples who are found there today.His most important wave --people who made a rectangular stone tool called an adz-- came from northern China into Southeast Asia, he said, and spread from there through the Malay Peninsula into Sumatra and Java, and then to Borneo, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan.