Maritime Meluhha Tin Road links Far East and Near East -- from Hanoi to Haifa creating the Bronze Age revolution

Note on tin-bronzes classification:

α-bronzes:10% Sn

β-bronzes: 25% Sn

γ-bronzes: 30% Sn

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. This bronze jar held cowrie shells, and is of a characteristic style of the Dian culture called tiger and bulls. Excavated from the Jinning site in Yunnan province, China.

This bronze jar held cowrie shells, and is of a characteristic style of the Dian culture called tiger and bulls. Excavated from the Jinning site in Yunnan province, China.

Clik here to view.

This bronze jar held cowrie shells, and is of a characteristic style of the Dian culture called tiger and bulls. Excavated from the Jinning site in Yunnan province, China.

This bronze jar held cowrie shells, and is of a characteristic style of the Dian culture called tiger and bulls. Excavated from the Jinning site in Yunnan province, China. Chronology

- 8th-6th centuries BC first Bronze age occupation

- 5th century BC, rise of elites at Yangfutou cemetery, Shizhaisan founded as a town

- 4th century BC, kingdom established

- 3rd century BC, Shizhaishan and Lijiashan founded as cemeteries

1. P. N. B. Or. H. M. ḍaṅkā m. ʻ drum ʼ; G. ḍaṅkɔ m. ʻ large kettledrum ʼ, M. ḍã̄kā m.

2. Pk. ḍakka -- m. ʻ a partic. musical instrument ʼ; G. ḍakkɔ m. ʻ drum ʼ; Si. ḍäkkiya ʻ tom -- tom ʼ.(CDIAL 5525) dundubhí m.f. ʻ large drum ʼ RV., °bhī -- f. MBh.

Pa. dundubhi -- , dudrabhi -- m.f. ʻ drum ʼ, Pk. duṁduhi<-> m.f., OAw. dūṁdu m.(CDIAL 6412). > Dong? (Vietnam)2. Pk. ḍakka -- m. ʻ a partic. musical instrument ʼ; G. ḍakkɔ m. ʻ drum ʼ; Si. ḍäkkiya ʻ tom -- tom ʼ.(CDIAL 5525) dundubhí m.f. ʻ large drum ʼ RV., °bhī -- f. MBh.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Bronze Drum from Dong Son Culture of Vietnam. Dated ca. 800 BC, at the Museu Guimet in Paris.

Metaphors of Dharma-Dhamma: Kubera, Nataraja...fusion of Indian and Khmer artistic cultural metaphors on lintels. Examples of Trans-Asiatic exchange network paralleling the Bronze Age exchanges along the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa

"Identifying indigenous elements in Angkorian art is not a task of subtracting the Indic iconography and appraising that which remains, but rather celebrating the creativeness of the medieval Khmer artistic process and makers." (Martin Polkinghorne, 2007, Makers and models: decorative lintels of Khmer temples, 7th to 11th centuries, University of Sydney) https://kerdomnelkhmer.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/polkinghorne-m-2007.pdf

Some Bronze Age sites, Far East. (After Fig. 2.2 in Higham, Charles, 1996, The bronze age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge Univ. Press

Tracing Southeast Asia Bronze Age to pre-Andronovo late 3rd millennium BCE

"It will be proposed on both chronological and technological grounds that the first bronze metallurgy in Southeast Asia was derived from pre-Andronovo late third millennium BC Eurasian forest-steppe metals technology, and not from the second millennium, technologically distinctive, élite-sponsored bronze metallurgy of the Chinese Erlitou or Erligang Periods." Date: 12 Nov 2009 The Transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives by Joyce C. White, Elizabeth G. Hamilton http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10963-009-9029-z

An uresolved challenge in archaeometallurgy is the source of tin for the production of Tin-Bronzes in Eurasia.

Archaeometallurgists seem to duck the question by suggesting locally panned -- from river beds -- 'small scale, labour-intensive' prospecting for tin as the source to explain the presence of tin-bronzes across Eurasia during the Early Bronze Age. Little attention has been paid to the possibility that the source of tin could simply have been the largest tin belt on the globe -- the Far East. The purport of this monograph is to draw the attention of archaeometallurgists to the major source of tin from Trans-Asiatic tin exchange along the Maritime Meluhha Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa. The central role in this Trans-Asia network for tin exchange is by Meluhha artisans and traders of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization area of Indian sprachbund, exemplified by Meluhha speakers (so-called Harappan cuture, in archaeological parlance).

Long-distance Trans-Asiatic Exchange network through Meluhha

"The possibility of a southern tin and tin-bronze trade through the Gulf is supported by the results of the present study, although the absence of analyzed third millennium BCE objects from the central Gulf is still a significant lacuna in our knowledge. As discussed above, such a trade route could explain the known distribution of tin-bronze in southern Mesopotamia and at Susa, and indeed has been proposed by TF Potts (1994: 281; Potts, TF, 1994, Mesopotamia and the East. An archaeological and history stuudy of foreign relations ca. 3400 - 2000 BCE, Oxford Committee for Archaeology Monograph 37, Oxford.) This southern maritime route was already long-estabished in the supply of copper and other goods to southern Mesopotamia and, by avoiding Iran altogether, possessed a number of advantages in cost and speed."(Weeks, Lloyd R., 2003, Early Metallurgy of the Persian Gulf, Brill Academic Publishers, Boston, Leiden, p. 193.)

Tin bronze excavated from Tilpi in lower Bengal region of eastern Bharatam Janam is a key indicator of the trans-asiatic technological traditions and archaeometallurgial networks between carnelian bead workers of Gulf of Khambat and the artisans of Khao Sam Kaeo, a coastal port site of Thailand in the Far East Tin Belt. Bali Yatra celebrated by Bharatam Janam every year on Karthik Purnima day is a remembrance of the role played by the ancestral artisan-traders in establishing archaeometallurgical and specialist lapidary networks. Meluhha seafaring artisans-merchants were the mediators in this technology exchange, the way they mediated the supply of tin to Sumer/Mesopotamia across the Persian Gulf to realize the tin-bronze revolution from ca. 5th millennium exemplified by the cire perdue alloy (arsenical-bronze?) artifacts of Nahal Mishmar..

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/gold-disc.html

Tin-Bronzes revolutionized ca. 5th millennium BCE, the creation of hard alloys replacing the scarce resource of arsenical copper used to create alloy metal castings, pots and pans, tools and weapons. The Maritime Meluhha Tin Road was the precursor of the later-day Silk Road.

The purport of this monograph is to draw the Maritime Meluhha Tin Road 1. sourcing tin from the largest tin-belt resource of the globe: Vietnam-Thai-Malay-Burma Peninsula or Far East Tin Belt; 2. identifying the transit points used by Meluhha speakers of this belt for maritime trade in tin which extended over a stunning distance of over 5000 kms. from Hanoi to Haifa; and 3. documenting archaeometallurgical insights provided by researchers using ancient text sources.

"Archaeological research in Southeast Asia is a relatively new field and there are huge gaps in our fundamental data and understanding. Large areas such as Myanmar and Laos remain little explored. Even in subregions such as Northeast Thailand, where there have been several decades of research, the data are quite thin...We argue that ... Sinocentric models are flawed for chronological, technological, and conceptual reasons ...metal technology may be one of the best media through which to explore the details of sociocultural interactions across Eurasia from the fourth thrugh to the first millennium BCE. In short, understanding the adoption of metallurgy in mainland Southeast Asia could provide important insights into the nature and events of late Holocene Eurasian technology and culture at a continental scale." (Joyce C White and Elizabeth G Hamilton, 2014, Chapter 28. The transmission of early Bronze technology to Thailand: New perspectives, in: Benjamin W Roberts, Christopher Thornton, Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: methods and syntheses, Springer Science and Business Media, ps.804-806).

Dong Soc culture of Far East is exemplified by two dominant metallurgical techniques: 1. cire perdue (lost-wax) method of casting alloy metals; and 2. production of tin-bronze alloys. This Bronze Age competence was carried through the Maritime Meluhha Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa.

A hypothesis that Meluhha speakers were involved in mediating the maritime Tin exchanges is founded on the following two correlating maps: 1. Pinnow's map of Austro-asiatic language areas in Bharatam and Far East; and 2. Higham's map of Bronze age sites in ancient India and Far East. This is complemented by philological studies evaluated by scholars in Univ. of Hawaii indicating the diffusion of Austro-asiatic from Bharatam (which is labeled Meluhha in ancient cuneiform texts of Sumer/Mesopotamia). Hence, the correlating maps of Bharatam and Far East may also be called Meluhha Tin-Bronze interaction zone which links three ports of call on the Indian Ocean rim: Khambhat (Meluhha) with Tilpi (Bengal) and Tabon Caves (Philippines). A fourth port of call which indicates the other end of the Maritime Meluhha Tin Road is Haifa where two pure tin ingots with Indus writing were discovered in a shipwreck which indicate sites like Enkomi of Cyprus as a transit port of maritime exchanges of the early Bronze Age.

Stannifrous areas of the world (From RG Taylor, Geology of Tin Deposits, Amsterdam 1979, 6, fig. 2.1)

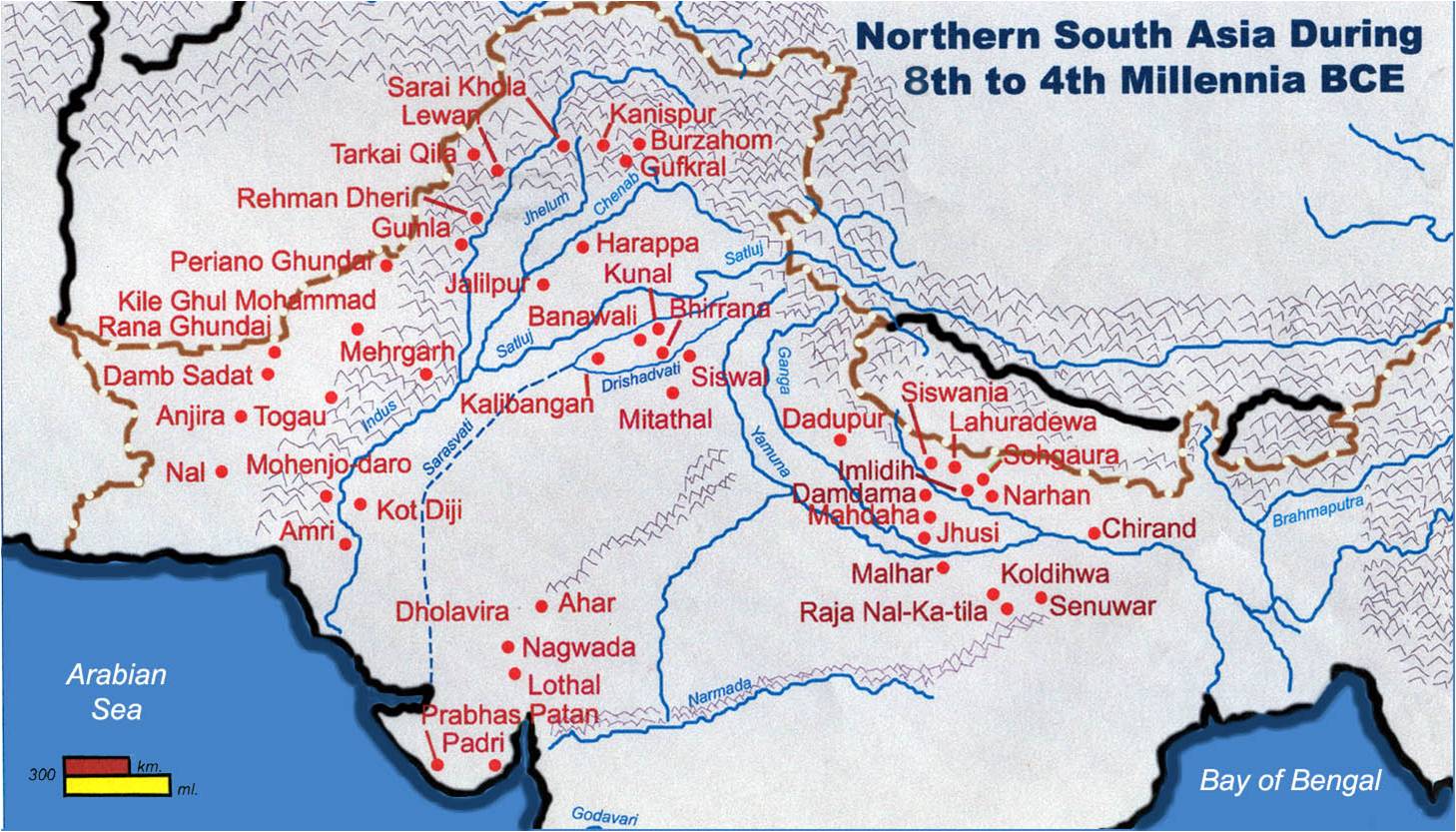

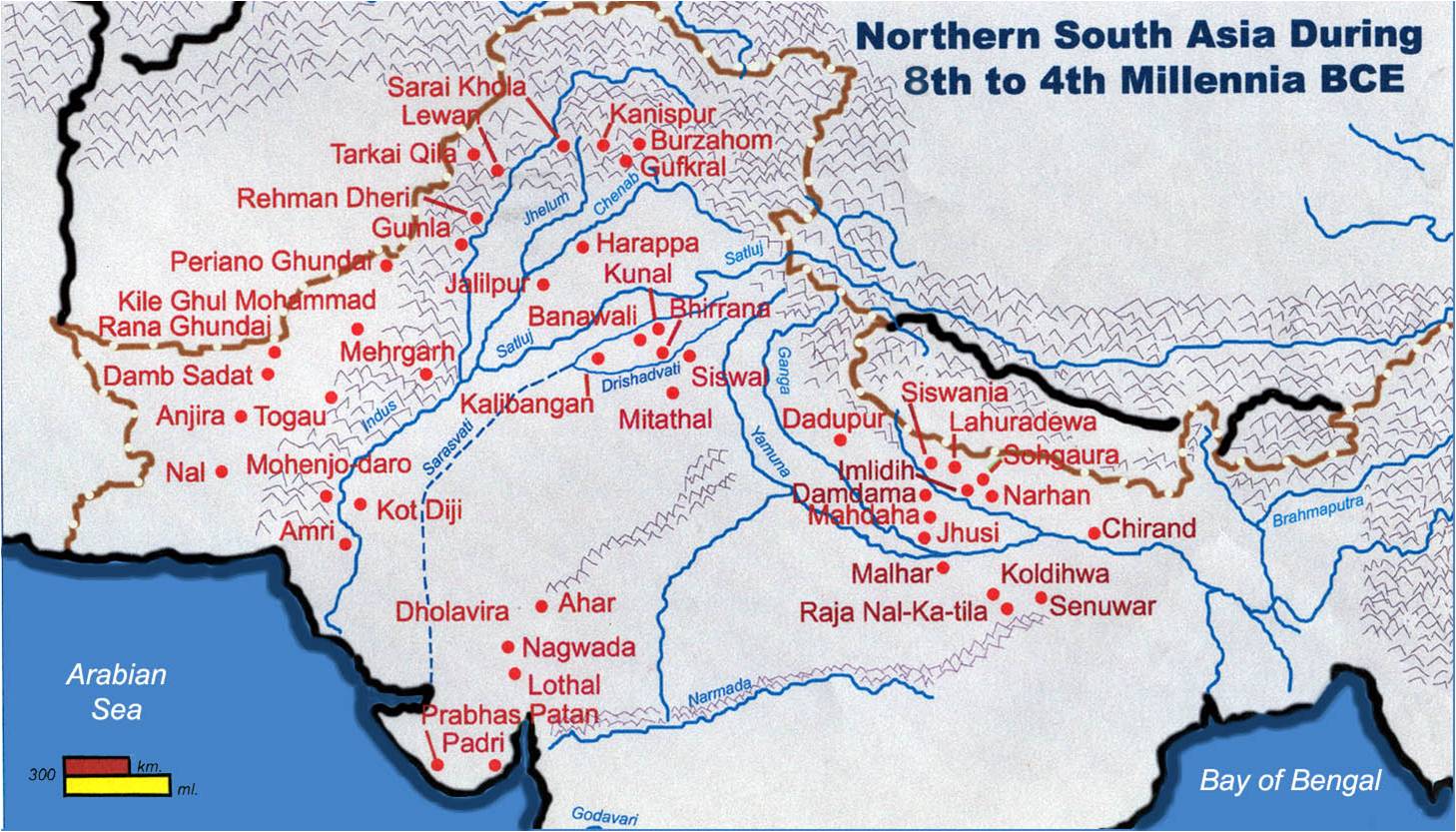

Coastal archaeological sites around Gulf of Khambat, Gulf of Kutch, close to Persian Gulf, Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization, between ca. 8th - 4th millennium BCE Proximity to the Gulf of Khambhat allowed direct access to maritime routes from Hanoi to Haifa..

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Haifa tin ingot 1: Inscribed tin ingot with a moulded head, from Haifa (Artzy, 1983: 53). The Meluhha hieroglyphs catalog and certify that this is a tin ingot: Hieroglyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) Rebus: mũh ‘ingot’ (Santali). The three hieroglyphs are: ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali) ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali). dāṭu = cross (Te.); dhatu = mineral (Santali) Hindi. dhāṭnā ‘to send out, pour out, cast (metal)’ (CDIAL 6771). [The 'cross' or X hieroglyph is incised on Haifa tin ingots 2&3.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Pinnow’s map of Austro-AsiaticLanguage speakers correlates with bronze age sites. http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/aa.html See http://kalyan97.googlepages.com/mleccha1.pdf

Bronze Age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2.Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6.Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa;8. Mohenjo-daro; 9.Ahar; 10. Kayatha; 11.Navdatoli; 12.Inamgaon; 13. Non PaWai; 14. Nong Nor;15. Ban Na Di andBan Chiang; 16. NonNok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

Cyprus castings of bronze stands with Meluhha hieroglyphs. AN391894001 AN258515001 British Museum. Bibliographic reference

Kiely 2011a M.12Macnamara & Meeks 1987 p. 58, no. 2

Catling 1964 pp. 205-207, no. 34; pl. 34

Giorgos Papassavas argues convincingly that the cyprus bronze-stands of this type were cast using the lost wax method. The Meluhha hieroglyphs (Indus writing) of reed and tambura player are read rebus.

Hieroglyph: kã̄ḍ reed Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hieroglyph: tanbūra 'lyre' Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper'.

Tanbur, a long-necked, string instrument originating in the Southern or Central Asia (Mesopotamia and Persia/Iran)

Iranian tanbur (Kurdish tanbur), used in Yarsan rituals

Turkish tambur, instrument played in Turkey

Yaylı tambur, also played in Turkey

Tanpura, a drone instrument played in India

Tambura (instrument), played in Balkan peninsula

Tamburica, any member of a family of long-necked lutes popular in Eastern and Central Europe

Tambouras, played in Greece

Tanbūra (lyre), played in East Africa and the Middle East

Dombra, instrument in Kazakhstan, Siberia, and Mongolia

Domra, Russian instrument

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Plate 65. Fig. 701 in: Frankfort, H., Univ. of Chicago, Oriental Institute, Vol. LXXII, Stratified cylinder seals from the Diyala Region, Illinoi, Univ. of Chicago Press.

Plate 65. Fig. 701 in: Frankfort, H., Univ. of Chicago, Oriental Institute, Vol. LXXII, Stratified cylinder seals from the Diyala Region, Illinoi, Univ. of Chicago Press.

Clik here to view.

Plate 65. Fig. 701 in: Frankfort, H., Univ. of Chicago, Oriental Institute, Vol. LXXII, Stratified cylinder seals from the Diyala Region, Illinoi, Univ. of Chicago Press.

Plate 65. Fig. 701 in: Frankfort, H., Univ. of Chicago, Oriental Institute, Vol. LXXII, Stratified cylinder seals from the Diyala Region, Illinoi, Univ. of Chicago Press.barad 'bull' Rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, tin, pewter'

There are also other objects (Sit Shamshi bronze, Indus seals, Gold dish of al-Sabah Iraq National Museum) which depict hieroglyphs for rebus reading of the gloss for an ingot:

దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala -- n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} ``^branch, ^twig''. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen', ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig', Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree', ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it', So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch', H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (Gujarati.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati).

It is possible that the ox-hide ingot carried by the bearer on the cyprus bronze stands is a hieroglyph denoting the gloss: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() See:

See:

Clik here to view.

See:

See: Tin belts on a reconstruction of continents (After Fig. 3 in: Jesus, Prentiss S., 1978, Considerations on the occurrence and exploitation of tin sources in the ancient near East, in: AD Franklin, JS Olin & TA Wertime, (eds), The search for Ancient Tin, Seminar papers held at the Smithsonian Institution, March 14-15, 1977, Washington DC, 1978, pp. 33-38; https://www.academia.edu/1088441/Considerations_on_the_Occurrence_and_Exploitation_of_Tin_Sources_in_the_Ancient_Near_East Drawn after Schuiling, R.D., 1967, Tin belts on the continents around the Atlantic ocean: Economic Geology, 62: 540-50).

Schuiling defines ten belts: "The boundaries of the belts have been drawn in such a way that at least all the productive localities are included in the belts....[The] density of tin occurrences within the belts is...20 times the density of tin occurrences outside the belts...[The latter] are usually isolated points; mineralogical curiosities in some...deposit of other minerals." (Schuiling, RD, 1967, Tin belts around the Atlantic Ocean: some aspects of the Geochemistry of Tin. In A Technical conference on Tin. London: Tin Research Institute, pp. 531-47).

From this map, it is clear that the only workable or marginal deposits of Tin belts in Eurasia are in: Cornwall, England and Thai-Malay Peninsula (Far East). The search for ancient tin which resulted in the creation of tin-bronzes and hence, the revolution of the Bronze Age of 5th millennium BCE has, therefore, to focus on these two tin belts. Muhly has demonstrated based on cuneiform texts that the source for tin in Sumer/Mesopotamia was NOT Cornwall, England BUT from a region called Meluhha.

Did this region called Meluhha extend from Afghanistan to Far East (Hanoi, Vietnam)?

Analysing the possible sources of tin, Jesus makes an insightful comment: "Although the list of sites which were acquainted with tin-bronze is rather short, they all have one feature in common, which may provide our clue to their metal source: they are all coastal sites, or they had access to maritime trade. Could this early source of tin have been exploited for the purpose of providing tin metal to influential Anatolian settlements and island towns of the Eastern Aegean?" (Jesus, Prentiss S., 1978, Considerations on the occurrence and exploitation of tin sources in the ancient near East, in: AD Franklin, JS Olin & TA Wertime, (eds), The search fo Ancient Tin, Seminar papers held at the Smithsonian Institution, March 14-15, 1977, Washington DC, 1978, p.37).

This means that tin was brought in by seafaring merchants.

I suggest that the seafaring merchants were from Meluhha.

One coast in Thailand provides indication of tin-bronze working: Khao Sam Kaeo.

Searching for coastal sites in the tin belt of Far East, that is, in Thai-Malay Peninsula, the site of Khao Sam Kaeo (KSK) stands out. [Murillo-Barroso, Mercedes, Thomas Oliver Pryce, Berenice Bellina, Marcos Martinon-Torres, Khao Sam Kaeo -- an archaeometallurgical crossroads for trans-asiatic technological traditions, Journal of Archaeological Science, 37 (2010), 1761-1772].

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/people/staff/martinon_torres/usercontent_profile/Murillo_Barroso_et_al_2010_KSK

Mirror: https://www.scribd.com/doc/255140390/Khao-Sam-Kaeo-an-archaeometallurgical-crossroads-for-trans-asiatic-technological-traditions-Murillo-Barroso-Et-Al-2010

Technical ceramics from KSK [After Fig. 10 in Murillo-Barroso et al (2010)]

Archaeometallurgical trans-asiatic networks in Khao Sam Kaeo

"In this paper we have shown that Khao Sam Kaeo has a number of metallurgy-related technologies and behaviours attested archaeologically, the consumption of gold ornaments, perhaps in burial contexts, the smithing of iron artefacts, probably copper-alloy founding, and possible involvement in tin exchange. Iron-smithing is the only technology indisputably evidenced on site, but the 2007 excavation of copper-bearing slag and a number of ceramic crucibles increase our confidence that copper-alloy casting was practiced on site. The efforts of the Thai-French mission have born much fruit for our understanding of the technical practice and social significance of metal technologies on site. We have used archaeometallurgical artefacts to provide further evidence for Khao Sam Kaeo's participation in Trans-Asiatic networks, with possible links to material culture from late prehistoric sites in Vietnam, and the Philippines, and early historical sites in South Vietam, the Indian subcontinent, and for the time to Han China." (Anna TN Bennett, Berenice Bellina-Pryce, Thomas Oliver Pryce, The development of metal technologies in the Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula: initial interpretation of the archaeometallurgical evidence from Khao Sam Kaeo, in: Bulletin de l'Ecole francaise d'Extreme-Orient, Year 2006, Vol. 93, p. 311).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Wrought and quenched high-tin bronze bowl from Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu of the early to mid first millennium BCE in Govt. Museum, Madras.

"Although it is difficult to speculate about origins, a long standing practice of using binary tin-bronzes (i.e. only copper-tin alloys) can be detected going back to Harappan bronzes which also seem to be predominantly binary bronzes with not much lead added to them. Though most of them seem to be low-tin bronze, the presence of a couple with higher tin of about 20% is also notable...4 Indus Valley Finds of High-Tin Bronzes and CopperBased

Metallurgy When one tries to trace back the antiquity of the Indian hightin bronzes, the analyses from the Indus Valley site of Mohenjo-daro of a few bronzes of the composition of binary high-tin bronze would surely rank amongst the earliest in the world, although without metallurgical study it cannot be established if these were beta bronzes, i.e. with the quenched beta phase, or merely as-cast bronzes of this composition. These are reported from corroded samples from deep digging in Block 7 of the DK area and Mackay’s notes suggests that he did not doubt that these were from an Indus valley context (c. 2000 BCE). Sample DK 9722 at 30 feet below datum had 22.2 % tin, with scarcely any lead at 0.86 %, typically matching the composition of high-tin beta bronze; sample DK 9567 had 26.9 % tin with no lead found at 26.8 feet below datum, while two more samples had 19 % tin with no lead. In fact if we look at a compilation of some 140 analyses of objects from Indus Valley contexts in and in a noticeable trend is that although about 30 objects from Mohenjo daro have tin contents over 5 % and contain no lead, and about 24 have more than 8 % tin and no lead while only 4–5 objects have more than 2 % lead. Indeed overall, out of 30 % bronze objects from different Indus sites with over 8 % tin, only one sample from Mohenjo daro had any substantial lead, of 14.9 % and that is in fact a beta bronze with 22.1 % tin. The addition of such high amounts of lead would have improved the castability and reduced brittleness

although this would not be a beta bronze but more of a bell metal alloy which has a good tonality. This might suggest that, rather than being accidental, lead could have been

deliberately added with the intention of experimenting to overcome the brittleness of the binary beta bronze alloy in the as-cast state. However the use of lead metal is also seen in

the form of what is described as a plumb bob, a lead ball of about an inch in diameter so that it appears that the alloying of tin and lead would have been intentional with some knowledge of the properties. As for other examples of bronzes of a high tin content, bangle piece from Kuntasi reported in Rajam Seshadri’s thesis ‘The Metal Technology of the Harappans and the Copper Hoard Culture-A Comparative Study’ had a composition of Cu 69.34 %, Pb 6.67 %, Sn 22.57 %. All of the above suggests that the Mohenjo daro craftsmen may have gone some way towards experimenting with the use of unleaded tin bronze and high-tin bronze. It must also be pointed out that, given the developed system of chert weights and measures from in the Indus Valley it would have been possible to measure out the fairly precise amounts of tin for high-tin bronze. Kenoyer points out that complete sets of smaller weights were found even at rural Indus Valley settlements, apart from major trading centres. As such, the rather tiny lost wax castings of the Harappan

era, although skilled (as exemplified by the famous Mohenjo daro dancing girl), and the relatively limited finds militate against the Indus Valley finds representing perhaps a fullblown copper–bronze tradition when compared to West Asia or China where large bronze castings had already come into vogue at a comparable period. However, it must be said that it would not have been easy to make large castings of bronze without the prevalence of liberal amounts of lead, due to shrinkage, porosities and brittleness in the casting of tin bronze which the addition of lead greatly minimise. It’s a matter for conjecture whether the restricted use of lead compared to tin detected by the author in the Harappan period was due to its scarcity and whether this contributed to the tinier sizes of Harappan bronzeware. As for the Daimabad bronzes, it is interesting that they are also consistent

with this trend noted in this paper of Harappan bronzes generally having not much lead. Some aspects of the Harappan finds seem distinctive and not entirely derivative when compared to coeval ones from West Asia; for instance, the flat circular mirrors. Indeed as excavator also comments that the Indus Valley mirrors were different from those from

Egypt, Sumer or Elam. However their shapes do recall to the flat Kerala mirror blanks...in connection with the making of the Aranmula high-tin bronzes." (Sharada Srinivasan, 2013, Megalithic and continuing peninsular high-tin binary bronzes: possible roots in Harappan binary bronze usage? in: Trans Indian Inst. Met (October-December 2013), p.735). http://www.nias.res.in/docs/sharada%20bronze%202013.pdf metalart96@gmail.com

Mirror: https://www.scribd.com/doc/255153849/Megalithic-and-Continuing-Peninsular-High-Tin-Binary-Bronzes-Possible-Roots-in-Harappan-Binary-Bronze-Usage-Sharada-Srinivasan-2013

Sharada Srinivasan continues her discussions suggesting the the sources of tin used in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization might have been local 'small scale, labor intensive mining', while noting that placer mining of tin leaves no traces. She does not discuss the possibility of a trans-Asiatic network from the world's largest tin belt: Thai-Vietnam-Burma-Malay Peninsula Tin belt along the Himalayan rivers of Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween and other local river systems in the Granite belt overlapping the Tin belt. Sharada Srinivasan simply concludes:"...Indus archaeologists such as Jarrige J-F, Arts Asiatiques 50 (1995) , p.5, who also effectively comments that the hiatus between the eclipse of the Indus civilization and later periods is now filled by archaeological finds demonstrating perhaps some threads of continuity in the material culture of the subcontinent."

In my view, the leads provided by Praon Silapanth and Berenice Bellina for analysing the Trans-Asiatic maritime exchange networks hold the promise of establishing how the rich resources of the Far East tin-belt could have reached the Ancient Near East, through a Maritime Meluhha Tin Road. It is an archaeometallurgical challenge to firmly delineate this maritime trade route for tin.

"Khao Sam Kaeo is located at the end of several possible trans-peninsular routes, forming a node that could have facilitated the control of upstream and downstream (river or sea) interactions. Some of these routes link tin-rich areas to sites yielding early evidence of trans-Asiatic interaction, such as Phu Khao Thong."(p.281) (Silapanth, Praon, Berenice Bellina-Pryce, 2006, Weaving cultural identities on trans-Asiatic networks: Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula – an early socio-political landscape, in: Bulletin de l'Ecole francaise d'Extreme-Orient, Vol. 93, Issue 93, pp. 257-293).

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/befeo_0336-1519_2006_num_93_1_6039

Datta, P.K., Chattopadhyay, P.K., Ray, A., 2007. New evidence for high-tin bronze in ancient Bengal. SAS Bulletin 30, 13–16.

"Metallurgy began in Bengal -- comprising both Bangladesh and West Bengal of India as early as 1500 BCE in the Chalcolithic Age. The recent nomenclature of this culture is known as black-and-red ware culture by the archaeologists and which evolved after the Neolithic Age. Copper has been used from the early part of this culture and the use of alloy has also been traced from objects attributed to the late phase of this period...The analyzed bronze specimens with more or less 9-11% tin belonging to this period was found in Bahiri, Bharatpur, Dihar, Mangalkot and Pandu Rajar Dhibi. The Alpha-bronze objects in this category mostly found are bangles, beads, earrings, finger rings, fish-hooks etc......High tin bronze (kansa) vessels of Bengal origin have been discovered at Ban Don Ta Phet, Thailand. The water bowls made of this material in cast form were brittle but its golden-white appearance was highly esteemed in society. High tin bronze mirrors, having over 30% Sn belong to Gamma-bronze have also been found at Chandraketugar and Mahasthan. Till to-day the use of kansar (gong) or kartal (cymbols) is continuing in the society at large...The site Tilpi (22.15'N, 88.38'E) is located in the coastal district of South 24-Parganas, West Bengal, India. The excavation was simultaneously conducted in the nearby village Dhosa...At Dhosa, it was suggested that a stupa existed there during th 2nd and 1st century BCE. Excavations have unearthed a wealth of proof that it was once thickly populated by industrious and self-sufficient people. The unearthed furnace and few other analyzed materials are shown at Figs. 1(a) and 2...Number of hearths at the site: 8. " (Prasanta K. Datta, Pranab K. Chattopadhyay, Barnali Mandal, 2008, Investigations on ancient high-tin bronze excavated from lower Bengal region of Tilpi, Indian Journal of History of Science, 43.3 (2008), pp. 381-382).

http://www.insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol43_3_3_PKDatta.pdf

Fig. 1(a) Excavation at Tilpi, showing the formation of a hearth for metal processing, probably of non-ferrous metals like copper, bronze, brass etc. The discontinuity at the foundation indicates the portion of the ash-pit door, for removal of cinder. The door was also used (like 'chulas' of sub-continental variety) for passing air blast under natural draft or forced draft, by winnowing fan, to generate het by the combustion of fuel.

Clik here to view.![]()

FIg. 2. Analyzed objects recovered at Tilpi, (1) Slag, (2) Metal ingot, (3) and (4) Broken crucible fragments.

| Sunday, March 19, 2006 |

"Although we have compared KSK's technical ceramics to others elsewhere in Thailand, there has been no convincing analogy for the particularly distinctive nippled wares. However, strikingly similar ceramics have recently been reported along with a high-tin bronze ingot from the broadly contemporary site of Tilpi in West Bengal (Datta et al., 2007). Given that high-tin bronzes probably date from at least the early 1st millennium BCE in South Asia, it is conceivable that KSK high-ton bronze production technologies were transmitted by some means across the Bay of Bengal. Such a possibility is in accordance with Bellina's original (2001) model of South Asian artisans settling at KSK and using South Asian techniques to produce 'South Asian' material culture (Belina, 2003, 207, 2008). However, it must be emphasised that KSK's metallurgical and glass industries lack the rigorously quantitative skill-based ethnoarchaeological studies that structure the hardstone ornament artisan 'limited migration' hypothesis." (Murillo-Barroso et al., opcit., pp.3770-3771,)

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/people/staff/martinon_torres/usercontent_profile/Murillo_Barroso_et_al_2010_KSK

Mirror: https://www.scribd.com/doc/255140390/Khao-Sam-Kaeo-an-archaeometallurgical-crossroads-for-trans-asiatic-technological-traditions-Murillo-Barroso-Et-Al-2010

Technical ceramics from KSK [After Fig. 10 in Murillo-Barroso et al (2010)]

Archaeometallurgical trans-asiatic networks in Khao Sam Kaeo

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Distribution of economic tin deposits located in Thailand (After Fig. 13 in Anna TN Bennett et al, 2006, opcit.) Archaeometallurgical challenge is to evaluate the possible exploitation of thie Tin belt resource in Trans-Asiatic tin exchange along a Maritime Tin Road of ca. 5th millennium BCE.

Distribution of economic tin deposits located in Thailand (After Fig. 13 in Anna TN Bennett et al, 2006, opcit.) Archaeometallurgical challenge is to evaluate the possible exploitation of thie Tin belt resource in Trans-Asiatic tin exchange along a Maritime Tin Road of ca. 5th millennium BCE.

Clik here to view.

Distribution of economic tin deposits located in Thailand (After Fig. 13 in Anna TN Bennett et al, 2006, opcit.) Archaeometallurgical challenge is to evaluate the possible exploitation of thie Tin belt resource in Trans-Asiatic tin exchange along a Maritime Tin Road of ca. 5th millennium BCE.

Distribution of economic tin deposits located in Thailand (After Fig. 13 in Anna TN Bennett et al, 2006, opcit.) Archaeometallurgical challenge is to evaluate the possible exploitation of thie Tin belt resource in Trans-Asiatic tin exchange along a Maritime Tin Road of ca. 5th millennium BCE."In this paper we have shown that Khao Sam Kaeo has a number of metallurgy-related technologies and behaviours attested archaeologically, the consumption of gold ornaments, perhaps in burial contexts, the smithing of iron artefacts, probably copper-alloy founding, and possible involvement in tin exchange. Iron-smithing is the only technology indisputably evidenced on site, but the 2007 excavation of copper-bearing slag and a number of ceramic crucibles increase our confidence that copper-alloy casting was practiced on site. The efforts of the Thai-French mission have born much fruit for our understanding of the technical practice and social significance of metal technologies on site. We have used archaeometallurgical artefacts to provide further evidence for Khao Sam Kaeo's participation in Trans-Asiatic networks, with possible links to material culture from late prehistoric sites in Vietnam, and the Philippines, and early historical sites in South Vietam, the Indian subcontinent, and for the time to Han China." (Anna TN Bennett, Berenice Bellina-Pryce, Thomas Oliver Pryce, The development of metal technologies in the Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula: initial interpretation of the archaeometallurgical evidence from Khao Sam Kaeo, in: Bulletin de l'Ecole francaise d'Extreme-Orient, Year 2006, Vol. 93, p. 311).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Wrought and quenched high-tin bronze bowl from Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu of the early to mid first millennium BCE in Govt. Museum, Madras.

Metallurgy When one tries to trace back the antiquity of the Indian hightin bronzes, the analyses from the Indus Valley site of Mohenjo-daro of a few bronzes of the composition of binary high-tin bronze would surely rank amongst the earliest in the world, although without metallurgical study it cannot be established if these were beta bronzes, i.e. with the quenched beta phase, or merely as-cast bronzes of this composition. These are reported from corroded samples from deep digging in Block 7 of the DK area and Mackay’s notes suggests that he did not doubt that these were from an Indus valley context (c. 2000 BCE). Sample DK 9722 at 30 feet below datum had 22.2 % tin, with scarcely any lead at 0.86 %, typically matching the composition of high-tin beta bronze; sample DK 9567 had 26.9 % tin with no lead found at 26.8 feet below datum, while two more samples had 19 % tin with no lead. In fact if we look at a compilation of some 140 analyses of objects from Indus Valley contexts in and in a noticeable trend is that although about 30 objects from Mohenjo daro have tin contents over 5 % and contain no lead, and about 24 have more than 8 % tin and no lead while only 4–5 objects have more than 2 % lead. Indeed overall, out of 30 % bronze objects from different Indus sites with over 8 % tin, only one sample from Mohenjo daro had any substantial lead, of 14.9 % and that is in fact a beta bronze with 22.1 % tin. The addition of such high amounts of lead would have improved the castability and reduced brittleness

although this would not be a beta bronze but more of a bell metal alloy which has a good tonality. This might suggest that, rather than being accidental, lead could have been

deliberately added with the intention of experimenting to overcome the brittleness of the binary beta bronze alloy in the as-cast state. However the use of lead metal is also seen in

the form of what is described as a plumb bob, a lead ball of about an inch in diameter so that it appears that the alloying of tin and lead would have been intentional with some knowledge of the properties. As for other examples of bronzes of a high tin content, bangle piece from Kuntasi reported in Rajam Seshadri’s thesis ‘The Metal Technology of the Harappans and the Copper Hoard Culture-A Comparative Study’ had a composition of Cu 69.34 %, Pb 6.67 %, Sn 22.57 %. All of the above suggests that the Mohenjo daro craftsmen may have gone some way towards experimenting with the use of unleaded tin bronze and high-tin bronze. It must also be pointed out that, given the developed system of chert weights and measures from in the Indus Valley it would have been possible to measure out the fairly precise amounts of tin for high-tin bronze. Kenoyer points out that complete sets of smaller weights were found even at rural Indus Valley settlements, apart from major trading centres. As such, the rather tiny lost wax castings of the Harappan

era, although skilled (as exemplified by the famous Mohenjo daro dancing girl), and the relatively limited finds militate against the Indus Valley finds representing perhaps a fullblown copper–bronze tradition when compared to West Asia or China where large bronze castings had already come into vogue at a comparable period. However, it must be said that it would not have been easy to make large castings of bronze without the prevalence of liberal amounts of lead, due to shrinkage, porosities and brittleness in the casting of tin bronze which the addition of lead greatly minimise. It’s a matter for conjecture whether the restricted use of lead compared to tin detected by the author in the Harappan period was due to its scarcity and whether this contributed to the tinier sizes of Harappan bronzeware. As for the Daimabad bronzes, it is interesting that they are also consistent

with this trend noted in this paper of Harappan bronzes generally having not much lead. Some aspects of the Harappan finds seem distinctive and not entirely derivative when compared to coeval ones from West Asia; for instance, the flat circular mirrors. Indeed as excavator also comments that the Indus Valley mirrors were different from those from

Egypt, Sumer or Elam. However their shapes do recall to the flat Kerala mirror blanks...in connection with the making of the Aranmula high-tin bronzes." (Sharada Srinivasan, 2013, Megalithic and continuing peninsular high-tin binary bronzes: possible roots in Harappan binary bronze usage? in: Trans Indian Inst. Met (October-December 2013), p.735). http://www.nias.res.in/docs/sharada%20bronze%202013.pdf metalart96@gmail.com

Mirror: https://www.scribd.com/doc/255153849/Megalithic-and-Continuing-Peninsular-High-Tin-Binary-Bronzes-Possible-Roots-in-Harappan-Binary-Bronze-Usage-Sharada-Srinivasan-2013

Sharada Srinivasan continues her discussions suggesting the the sources of tin used in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization might have been local 'small scale, labor intensive mining', while noting that placer mining of tin leaves no traces. She does not discuss the possibility of a trans-Asiatic network from the world's largest tin belt: Thai-Vietnam-Burma-Malay Peninsula Tin belt along the Himalayan rivers of Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween and other local river systems in the Granite belt overlapping the Tin belt. Sharada Srinivasan simply concludes:"...Indus archaeologists such as Jarrige J-F, Arts Asiatiques 50 (1995) , p.5, who also effectively comments that the hiatus between the eclipse of the Indus civilization and later periods is now filled by archaeological finds demonstrating perhaps some threads of continuity in the material culture of the subcontinent."

In my view, the leads provided by Praon Silapanth and Berenice Bellina for analysing the Trans-Asiatic maritime exchange networks hold the promise of establishing how the rich resources of the Far East tin-belt could have reached the Ancient Near East, through a Maritime Meluhha Tin Road. It is an archaeometallurgical challenge to firmly delineate this maritime trade route for tin.

"Khao Sam Kaeo is located at the end of several possible trans-peninsular routes, forming a node that could have facilitated the control of upstream and downstream (river or sea) interactions. Some of these routes link tin-rich areas to sites yielding early evidence of trans-Asiatic interaction, such as Phu Khao Thong."(p.281) (Silapanth, Praon, Berenice Bellina-Pryce, 2006, Weaving cultural identities on trans-Asiatic networks: Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula – an early socio-political landscape, in: Bulletin de l'Ecole francaise d'Extreme-Orient, Vol. 93, Issue 93, pp. 257-293).

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/befeo_0336-1519_2006_num_93_1_6039

Datta, P.K., Chattopadhyay, P.K., Ray, A., 2007. New evidence for high-tin bronze in ancient Bengal. SAS Bulletin 30, 13–16.

"Metallurgy began in Bengal -- comprising both Bangladesh and West Bengal of India as early as 1500 BCE in the Chalcolithic Age. The recent nomenclature of this culture is known as black-and-red ware culture by the archaeologists and which evolved after the Neolithic Age. Copper has been used from the early part of this culture and the use of alloy has also been traced from objects attributed to the late phase of this period...The analyzed bronze specimens with more or less 9-11% tin belonging to this period was found in Bahiri, Bharatpur, Dihar, Mangalkot and Pandu Rajar Dhibi. The Alpha-bronze objects in this category mostly found are bangles, beads, earrings, finger rings, fish-hooks etc......High tin bronze (kansa) vessels of Bengal origin have been discovered at Ban Don Ta Phet, Thailand. The water bowls made of this material in cast form were brittle but its golden-white appearance was highly esteemed in society. High tin bronze mirrors, having over 30% Sn belong to Gamma-bronze have also been found at Chandraketugar and Mahasthan. Till to-day the use of kansar (gong) or kartal (cymbols) is continuing in the society at large...The site Tilpi (22.15'N, 88.38'E) is located in the coastal district of South 24-Parganas, West Bengal, India. The excavation was simultaneously conducted in the nearby village Dhosa...At Dhosa, it was suggested that a stupa existed there during th 2nd and 1st century BCE. Excavations have unearthed a wealth of proof that it was once thickly populated by industrious and self-sufficient people. The unearthed furnace and few other analyzed materials are shown at Figs. 1(a) and 2...Number of hearths at the site: 8. " (Prasanta K. Datta, Pranab K. Chattopadhyay, Barnali Mandal, 2008, Investigations on ancient high-tin bronze excavated from lower Bengal region of Tilpi, Indian Journal of History of Science, 43.3 (2008), pp. 381-382).

http://www.insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol43_3_3_PKDatta.pdf

External surface of the Tilpi crucible. (which compares with the shape of the KSK crucible). "Similar shaped crucibles were detected in contemporary Senuwar, Bihar in Kushana Period 1st-3rd century CE."

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

FIg. 2. Analyzed objects recovered at Tilpi, (1) Slag, (2) Metal ingot, (3) and (4) Broken crucible fragments.

| Sunday, March 19, 2006 |

Furnace find near stupa site | ||

| SEBANTI SARKAR | ||

Calcutta, March 18: Excavations at Tilpi in South 24-Parganas have unearthed a wealth of proof that it was once thickly populated by industrious and self-sufficient people. Tilpi is the twin site of Dhosa in Joynagar, around 50 km from Calcutta. Artefacts and structural evidences found during excavations at Dhosa suggest that a stupa existed there in the 2nd and 1st century BCE. Goutam Sengupta, Bengal’s director of archaeology and museums, said eight hearths for smelting metals have been found in Tilpi. Speaking from the site, state archaeology department supervisor Amal Roy added that the four hearths discovered on March 18 were at a slightly lower level than the four found on the surface level. The trenches have now reached a depth of almost 2 metres. The hearths measure between 50 cm and 80 cm and are around 30 cm high. These hearths “are typical of the early historic era, roughly 2nd century BCE, and strewn around them are crucibles, charcoal fragments, copper ingots and punchmarked and cast-copper coins. The small crucibles, measuring 2.5 cm, may have been used to melt metals like silver and copper while the larger ones (8 cm) for iron.” A large clay jar fixed to the ground near a hearth was probably used to store water used by the smiths, said Roy. Archaeo-metallurgist Pranab K. Chattopadhyay of the Centre for Archaeological Studies and Training, eastern India, confirmed the importance of the Tilpi find as the single instance in the region where all evidences of the indigenous smelting and casting processes are seen together. The coins are being tested for bronze, which would prove that the residents of Tilpi knew how to combine metals in various proportions. “High-tin-bronze or kansha was in use between the 2nd century BC and 2nd century CE as evident from Chandraketugarh,” said Chattopadhyay. The source of raw material can be found only after further analysis but scholars feel the metals were brought from areas like Midnapore or Jharkhand. |

"Although we have compared KSK's technical ceramics to others elsewhere in Thailand, there has been no convincing analogy for the particularly distinctive nippled wares. However, strikingly similar ceramics have recently been reported along with a high-tin bronze ingot from the broadly contemporary site of Tilpi in West Bengal (Datta et al., 2007). Given that high-tin bronzes probably date from at least the early 1st millennium BCE in South Asia, it is conceivable that KSK high-ton bronze production technologies were transmitted by some means across the Bay of Bengal. Such a possibility is in accordance with Bellina's original (2001) model of South Asian artisans settling at KSK and using South Asian techniques to produce 'South Asian' material culture (Belina, 2003, 207, 2008). However, it must be emphasised that KSK's metallurgical and glass industries lack the rigorously quantitative skill-based ethnoarchaeological studies that structure the hardstone ornament artisan 'limited migration' hypothesis." (Murillo-Barroso et al., opcit., pp.3770-3771,)

Mercedes Murillo-Barroso et al note: "Recent archaeological investigations at Khao Sam Kaeo, on the Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula, have furnished evidence for a mid/late 1st millennium BCE cultural exchange network stretching from the Indian subcontinent to Taiwan. Typological, compositional and technological study of Khao Sam Kaeo’s copperbase artefacts has identified three distinct copper-alloy metallurgical traditions, with reasonable analogies in South Asian, Vietnamese, and Western Han material culture. Furthermore, analyses of technical ceramic and slag suggest that Khao Sam Kaeo metalworkers may have been using a cassiterite cementation process to produce high-tin bronze ingots for export or onsite casting/forging. Not only would this industry constitute the earliest evidence for the exploitation of Peninsula tin resources, but we also offer a speculative argument for the source of Khao Sam Kaeo’s copper-base production technology."

Situating Khao Sam Kaeo within the contact area of Meluhha trans-Asiatic maritime exchange zone extending from Khambat to Tabon Caves (After Fig. 1 Austronesian groups’ circulation and/or exchange networks. Relief map of the Bay of Bengal and South China Sea theatre of prehistoric maritime exchange, with major sites...Khambat is the location of Roux et a's (1995) ethnoarchaeological hard-stone study...; these locales are shown to show the potential extent of trans-Asiatic interactions. Courtesy of ESRI, elevation data derived from SRTM).

Khao Sam Kaeo and other pre-historic sites of Far East in the Tin belt (After Fig. 2(a) in: Murillo-Barroso, Mercedes et al, opcit.)

Were there other coastal sites in the Far East tin belt, with evidence of tin-bronzes earlier than 1st millennium BCE?

Papagudem boy wearing a bangle of tin

“Bronze articles such as ornamental mirrors, arrowheads, pins, bangles and chisels, of both low tin and high tin content, have been recovered from Lothal, the Harappn port on the Gujarat coast, which has been dated earlier than 2200 BCE. The tin content in these articles range from 2.27% to 11.82%; however, some of the articles contain no tin. Tin is said to have been brought as tablets from Babylon and mixed with copper to make an alloy of more pleasing colour and luster, a bright golden yellow. The utilization of bronze is essential only for certain articles and tools, requiring sharp cutting edges, such as axes, arrowheads or chisels. The selection of bronze for these items indicates the presence of tin was intentional…Recent discoveries of tin occurrences in India are shown in…Fig. 11.2. However, none of these occurrences shows evidences of ancient mining activity. This is because, unlike copper ores, the mining and metallurgy of the tin ore cassiterite is simple, and leaves little permanent trace…tin ore is usually recovered by simple panning of surface deposits, often contained in gravel, which soon collapse, leaving little evidence of having once been worked. Cassiterite is highly resistant to weathering, and with its high specific gravity, it can be easily separated from the waste minerals. The simple mining and metallurgical methods followed even now by Bastar and Koraput tribals in Chattisgarh and Orissa, central India, could be an indication of the methods used in the past. These tribal people produce considerable quantities of tin without any external help, electric power or chemical agents, enough to make a modern metallurgist, used to high technology, wonder almost in disbelief. Clearly though, the technology practiced has a considerable importance for those studying early smelting practices. The history of this process is poorly known. Back in the 1880s Ball (1881) related the story of a Bastar tribal from the village of Papagudem, who was observed to be wearing a bangle of tin. When questioned as to where the metal had come from, he replied that black sands, resembling gunpowder were dug in his village and smelted there. Thus it is very likely that the present industry is indigenous, and may have a long history. That being said, neither the industry or its products appear in any historical document of any period, and thus is unlikey to have been a significant supplier of metal…The tin content of cassiterite ranges from 74.94% (mean 64.2%), showing that pebbles contain about 70% to 90% of the tin oxide, cassiterite…The ore is localized in gravel beds of the black pebbles of cassiterite which outcrop in stream beds etc. and there are other indicators, in the vegetation. The leaves of the Sarai tree (Shoria robusta) growing on tin-rich ground are often covered in yellow spots, as if suffering from a disease. (The leaves were found to contain 700 ppm of tin on analysis!) Wherever the tribals find concentrations of ore in the top soil, the ground all around the area is dug up and transported to nearby streams, rivers or ponts…The loose gravelly soil containing the tin ore is dug with pick and shovel, and carried to the washing sites in large, shoulder-strung bamboo baskets. The panning or washing of the ore is carrie out using round shallow pans of bamboo. The soil is washed out, leaving the dense casiterite ore at the bottom of the pan…The ore is smelted in small clay shaft furnaces, heating and reducing the ore using charcoal as the fuel…The shft furnaces are square at the base and of brick surmounted by a clay cylindrical shaft…The charcoal acts as both the heating and reducing agent, reducing the black cassiterite mineral into bright, white tin metal…a crude refining is carried out by remelting the metal in an iron pan at about 250 degrees C. The molten tin is then poured into the stone-carved moulds to make square- or rectangular-shaped tin ingots for easy transportation.” (Babu, TM, opcit., pp.176-179)

Panning for cassiterite using bamboo pans in a pond in Orissa. The ore is carried to the water pond or stream for washing in bamboo baskets.

The tin is refined by remelting the pieces recovered from the furnace in an iron pan. The molten tin is poured into stone-carved moulds to make square- or rectangular-ingots.

As the pictorial gallery demonstrates, the entire tin processing industry is a family-based or extended-family-based industry. The historical traditions point to the formation of artisan guilds to exchange surplus cassiterite in trade transactions of the type evidenced by the seals and tablets, tokens and bullae found in the civilization-interaction area of the Bronze Age.

Papagudem boy wearing a bangle of tin

“Bronze articles such as ornamental mirrors, arrowheads, pins, bangles and chisels, of both low tin and high tin content, have been recovered from Lothal, the Harappn port on the Gujarat coast, which has been dated earlier than 2200 BCE. The tin content in these articles range from 2.27% to 11.82%; however, some of the articles contain no tin. Tin is said to have been brought as tablets from Babylon and mixed with copper to make an alloy of more pleasing colour and luster, a bright golden yellow. The utilization of bronze is essential only for certain articles and tools, requiring sharp cutting edges, such as axes, arrowheads or chisels. The selection of bronze for these items indicates the presence of tin was intentional…Recent discoveries of tin occurrences in India are shown in…Fig. 11.2. However, none of these occurrences shows evidences of ancient mining activity. This is because, unlike copper ores, the mining and metallurgy of the tin ore cassiterite is simple, and leaves little permanent trace…tin ore is usually recovered by simple panning of surface deposits, often contained in gravel, which soon collapse, leaving little evidence of having once been worked. Cassiterite is highly resistant to weathering, and with its high specific gravity, it can be easily separated from the waste minerals. The simple mining and metallurgical methods followed even now by Bastar and Koraput tribals in Chattisgarh and Orissa, central India, could be an indication of the methods used in the past. These tribal people produce considerable quantities of tin without any external help, electric power or chemical agents, enough to make a modern metallurgist, used to high technology, wonder almost in disbelief. Clearly though, the technology practiced has a considerable importance for those studying early smelting practices. The history of this process is poorly known. Back in the 1880s Ball (1881) related the story of a Bastar tribal from the village of Papagudem, who was observed to be wearing a bangle of tin. When questioned as to where the metal had come from, he replied that black sands, resembling gunpowder were dug in his village and smelted there. Thus it is very likely that the present industry is indigenous, and may have a long history. That being said, neither the industry or its products appear in any historical document of any period, and thus is unlikey to have been a significant supplier of metal…The tin content of cassiterite ranges from 74.94% (mean 64.2%), showing that pebbles contain about 70% to 90% of the tin oxide, cassiterite…The ore is localized in gravel beds of the black pebbles of cassiterite which outcrop in stream beds etc. and there are other indicators, in the vegetation. The leaves of the Sarai tree (Shoria robusta) growing on tin-rich ground are often covered in yellow spots, as if suffering from a disease. (The leaves were found to contain 700 ppm of tin on analysis!) Wherever the tribals find concentrations of ore in the top soil, the ground all around the area is dug up and transported to nearby streams, rivers or ponts…The loose gravelly soil containing the tin ore is dug with pick and shovel, and carried to the washing sites in large, shoulder-strung bamboo baskets. The panning or washing of the ore is carrie out using round shallow pans of bamboo. The soil is washed out, leaving the dense casiterite ore at the bottom of the pan…The ore is smelted in small clay shaft furnaces, heating and reducing the ore using charcoal as the fuel…The shft furnaces are square at the base and of brick surmounted by a clay cylindrical shaft…The charcoal acts as both the heating and reducing agent, reducing the black cassiterite mineral into bright, white tin metal…a crude refining is carried out by remelting the metal in an iron pan at about 250 degrees C. The molten tin is then poured into the stone-carved moulds to make square- or rectangular-shaped tin ingots for easy transportation.” (Babu, TM, opcit., pp.176-179)

Here is a pictorial gallery:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Bihar, India | Massive anklets with ball decoration | Brass with tin | ca. prior to 1867]() Bihar, India | Massive anklets with ball decoration | Brass with tin | ca. prior to 1867

Bihar, India | Massive anklets with ball decoration | Brass with tin | ca. prior to 1867

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Pictorial gallery of panning for Tin

Clik here to view.

Bihar, India | Massive anklets with ball decoration | Brass with tin | ca. prior to 1867

Bihar, India | Massive anklets with ball decoration | Brass with tin | ca. prior to 1867Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Pictorial gallery of panning for Tin

Panning for cassiterite using bamboo pans in a pond in Orissa. The ore is carried to the water pond or stream for washing in bamboo baskets.

People panning for cassiterite mineral in the remote jungles of central India.

The ore is washed to concentrate the cassiterite mineral using bamboo pans. Base of small brick and mud furnace for smelting tin.

The tin is refined by remelting the pieces recovered from the furnace in an iron pan. The molten tin is poured into stone-carved moulds to make square- or rectangular-ingots.

As the pictorial gallery demonstrates, the entire tin processing industry is a family-based or extended-family-based industry. The historical traditions point to the formation of artisan guilds to exchange surplus cassiterite in trade transactions of the type evidenced by the seals and tablets, tokens and bullae found in the civilization-interaction area of the Bronze Age.

It is possible that many goblins shown on many sculptural friezes of ancient India denote people engaged in placer mining for tin and creating tin-bronzes: gaṇá m. ʻ troop, flock ʼ RV. [Poss. (despite doubts in EWA i 316) < *gr̥ṇa -- ʻ telling ʼ (cf. *gr̥nti -- and esp. gaṇáyati ʻ tells one's number (of troop of flock) ʼ Kāś.Pa. Pk. gaṇa -- m. ʻ troop, flock ʼ; Tor. (Biddulph) gan m. ʻ herd ʼ; K. gan m. ʻ beehive ʼ = mã̄cha -- gan m.; WPah. bhal. gaṇ m. pl. ʻ bees ʼ; Si. gaṇaya ʻ company ʼ (CDIAL 3988). Thus, hatabā kāk-a, O father (familiarly), hatau Gana (for Gana + a), O Gana. When a woman addresses a man or a woman by his or her proper name we may use-a bāyĕ or-a bāyau. Thus, hatabā Mahādēv-a bāyĕ, hatabā Mahādēv-a bayau, or hatau Mahādēv-a bāyau, O Mahādēv. This cannot be used with words which are not proper names. (Kashmiri). Ta. kaṇakaṇa (-pp-, -tt-) to sound, rattle, jingle, tinkle; kaṇakaṇ-eṉal tintinnabulation, tinkling as of bells. Ka. kaṇa an imitative sound; kaṇakaṇa the ringing sound of unbroken earthen or metal vessels, bells, etc., when struck with the knuckles; gaṇa, gaṇagaṇa, gaṇal, gaṇil imitative sound of the ringing of bells.Tu. gaṇilů tinkling; gaṇaṅṅů a tinkling sound. Te. gaṇagaṇa the ringing or tinkling of bells. / MBE 1969, p. 289, no. 3, for areal etymology, with reference to Turner, CDIAL, no. 3791, khaṇakhaṇāyate, and no. 4425, *ghanaghana- (or *ghaṇaghaṇa-). (DEDR1162)3791 khaṇakhaṇāyatē ʻ cracks, tinkles ʼ BhP., khaṇat- khaṇīkr̥ta -- Mcar.

Pk. khaṇakhaṇaï ʻ tinkles ʼ; M. khaṇāṇṇẽ ʻ to clank ʼ, khaṇāṇ m. ʻ loud clanking ʼ; -- Pk. khaṇakkhaṇaï; N. khankhan ʻ jingle ʼ, khankhanāunu ʻ to jingle ʼ; B.khankhan ʻ ringing ʼ; Or. khaṇkhaṇ ʻ a sound produced in the nose when coughing ʼ; H. khankhan f. ʻ tinkling ʼ, khankhanānā ʻ to tinkle ʼ, G. khaṇkɔ m.,khaṇkhaṇvũ; M. khaṇkhaṇ ʻ with a clang ʼ, khaṇkhaṇṇẽ ʻ to clang ʼ.KHAṆḌ ʻ break ʼ. [Of non -- Aryan origin, perh. Mu. EWA i 300: cf. √Hoabinhian stone tool industry, Far East.

Đông Sơn culture (literally "East Mountain culture") and presents a remarkable example of the use of tin-bronze for making drums. The literal meaning of 'Dong Son' as 'east mountain' compares with the following Meluhha etyma:

Đông Sơn culture (literally "East Mountain culture") and presents a remarkable example of the use of tin-bronze for making drums. The literal meaning of 'Dong Son' as 'east mountain' compares with the following Meluhha etyma:

Hieroglyphs, rebus readings:

*ḍhōkka2 ʻ rock ʼ. 2. *ḍhōṅka -- . [Perh. belongs to same group as *ḍōṅga -- 2 s.v. *ṭakka -- 3 ]1. Kho. (Lor.) ḍok ʻ high ground, hillock, heap ʼ; H. ḍhok m. ʻ large piece of broken stone ʼ. 2. Ku. ḍhũgo ʻ stone ʼ, N. ḍhuṅgo. WPah.kc. ḍhōk m. ʻ mountain slope, peak ʼ.(CDIAL 5603).

*ḍhōkka

Ku. ḍã̄g, ḍã̄k ʻ stony land ʼ; B. ḍāṅ ʻ heap ʼ, ḍāṅgā ʻ hill, dry upland ʼ; H. ḍã̄g f. ʻ mountain-- ridge ʼ; M. ḍã̄g m.n., ḍã̄gaṇ, °gāṇ, ḍãgāṇ n. ʻ hill-- tract ʼ. -- Ext. -- r--: N. ḍaṅgur ʻ heap ʼ(CDIAL 5423) Rebus: ḍhaṅgar 'blacksmith'

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.

Clik here to view.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Dong Song drum findings, Vietnam. Dong Song is a pre-historic Bronze Age culture which dominated the Far East as a continuum of the neolithic Hoabinhian stone tool industry of the Far East..

Dong Song drum findings, Vietnam. Dong Song is a pre-historic Bronze Age culture which dominated the Far East as a continuum of the neolithic Hoabinhian stone tool industry of the Far East..

Clik here to view.

Regional concentrations of early Dong Son bronze drums and main river routes on the mainland and in western Indonesia. https://www.flickr.com/photos/doremon360/3772864141/in/set-72157602097553987/

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum's surface, Vietnam.

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum's surface, Vietnam.

Four frogs as hieroglyphs on the top surface of a Dong Son drum.Clik here to view.

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum's surface, Vietnam.

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum's surface, Vietnam.The dominant hieroglyphs are: sun, frog and markhor.

Hieroglyph: arka 'sun' Rebus: eraka 'copper'. cf. agasale 'coppersmith, goldsmith'.

Hieroglyph: frog: <menDaka>(A) {N} ``^frog''. *Hi.<mE~dhak>, Skt.<maNDu:kam>. #21820.<poto menDka>(Z) {N} ``^toad''. |<poto> `?'. ^frog (which lives out of water). *Loan?. #27302.<o~ia mendka>(Z),,<oJa mendka>(Z) {N} ``^bullfrog''. |<o~ia> `id.'. ??RECTE D? #24562. Rebus: meṛed-bica 'iron stone-ore' ; bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda). mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’(Munda. Ho.) (Source: Munda etyma)

The Dong Son culture is a celebration of the use of metal for a drum. "The discovery of Đông Sơn drums in New Guinea, is seen as proof of trade connections - spanning at least the past thousand years - between this region and the technologically advanced societies of Java and China." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%90%C3%B4ng_S%C6%A1n_drums

Or. meñcaṛā ʻ dwarfish ʼ.(CDIAL 10306).

Rebus: meṛed-bica 'iron stone-ore' ; bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda). mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’(Munda. Ho.)

Hieroglyph: mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ,*mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra --]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb.amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., °ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H.meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ AFD 235.(CDIAL 10310).

Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. l. 47 cm. width 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical copper and then joined by casting; left-eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forhead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern) Inv. No. LNS 1653 M. Splendour Exhibition Brochure. Kuwaiti Museum.

Unresolved questions on the role of Chandraketugarh in archaeometallurgical explorations, and of the writing system used in Chandraketugarh inscriptions

Located on Bidyadhari river (35 km. northeast of Kolkata), near Berachampa town, the archaeological site of Chandraketugarh is to be re-evaluated for chronological classification, but the indications that the finds of Northern Black Polished Ware relics date the site from ca. 400 BCE.

Two views are presented: 1. Views of DK Chakrabarti and 2. Views of Harry Falk with particular reference to BN Mukherjee's claim of Kharosti-Brahmi Mixed script.

Ambarish Goswami presents DK Chakrabarti's comments (ca. 2001) on Chandraketugarh archaeology:

The Historical and Archaeological Context of Chandraketugarh

Dr. Dilip K. Chakrabarti

University Lecturer of South Asian Archaeology

University of Cambridge

Chandraketugarh is the modern name of the site. We do not know its ancient name. The reason is that there is no clear textual reference to a city in this part of Bengal. Whether it was Gange, the capital of a kingdom called Gangaridai in the Graeco-Roman sources can always be debated, but there cannot be any positive conclusion. There is nothing in the records to indicate a specific location of either the capital or the kingdom. There is also no inscription from the site, which gives the ancient name of the place. There are, of course, inscriptions on pots, potsherds and round seals with designs, but the way they have been read does not make any sense. These inscriptions have been considered by a scholar as evidence of a mixed script in which the letters of both the major scripts of ancient India Brahmi and Kharosthi were used to write a single inscription. On modern analogy, this would be equivalent to writing a word or sentence in which the individual letters of two modern Indian scripts say, Bengali and Tamil would be used. This is a silly notion. Sillier still are attempts to reconstruct the history of this site on the basis of readings based on this method of reading.

So, if written history does not tell us anything about the site, how can we know about it? We can certainly know a lot about it by extensively excavating it and undertaking other types of field-studies including remote-sensing and geophysical surveys. No such work has yet been done. Whatever excavations were undertaken here in the 1950s and 1960s remained basically unpublished. We do not know precisely even about the total area of the site; there is a large fortified area and there is perhaps a larger unfortified area. Do we really know that it was located on the bank of a river? It was likely to have stood on a riverbank, but even this simple proposition remains to be worked out in the field. It thus appears that neither written history nor archaeology has told us much about Chandraketugarh.

Our knowledge of this site is based almost entirely on the antiquities found here by the local people. Chronologically these antiquities belong to a long period from the third century B.C. to about 10th-12th centuries A.D. These antiquities are of various kinds: coins, beads of semi-precious stones, terracottas, stone sculptures, ivories, and so on. They occur in varying quantities at all the contemporary settlements of the subcontinent, but there is a very special thing about Chandraketugarh. The sheer number and diversity of its early historic terracottas is unmatched at any other site. Some of them are also very beautiful and sophisticated.

One must also consider ivories along with the terracottas. Chandraketugarh is one of the major centres of ancient Indian ivory objects, as the increasing number of such objects found by the villagers indicates. Those who have seen the Chandraketugarh terracottas and ivories and can also think of such finds from other sites will not have a moment¹s hesitation to claim that Chandraketugarh must have been a very elegant and sophisticated urban centre of ancient India.

How did such an urban centre come to grow here? Was it an isolated place or a part of a wider network? The date of the early historic urban growth in Bengal is not yet decided. The reason is that there is no run of radiocarbon dates from the relevant levels which have also not been reached at places like Chandraketugarh in the Bengal delta. Generally it is put around 300 B.C. on the assumption that the growth of early historical cities began in this area only after it came under the control of the Mauryas. There is nothing definitive about this assumption. What we know is that the pre-300 B.C. context in the whole area from Birbhum to Medinipur on the western bank of the Bhagirathi was marked by a village economy which was characterized, among other things, by Black-and-Red plain and painted pottery, small stone tools called microliths, a limited use of copper and tin, cultivation of rice, and from about 1200 B.C. onwards, by the use of iron as well.

This village phase began in West Bengal about 1600/1800 B.C. In its turn this village phase is linked to the corresponding village growth throughout the Ganga valley. It is these "Black-and-Red Ware people" who settled in the Bhagirathi-Rupnarayan delta. There is evidence from Harinarayanpur south of Diamond Harbour and Tamluk on the Rupnarayan, although not from Chandraketugarh itself. We do not know when this settling process began. I shall not be surprised if it goes back to c.1000 B.C.

How many early historic cities were there in ancient Bengal? Among the front-rank places one has to mention the following: ancient Pundranagara or modern Mahasthangarh on the bank of the Karatoya near the Bangladeshi district town of Bagura; Wari Bateshwar (ancient name unknown) on the bank of an old channel of the Brahmaputra near Bhairavbazar/ Narsingdi in Bangladesh; Kotasur (ancient name unknown) on the bank of the Mayurakshi near Sainthia in Birbhum; Mangalkot (ancient name unknown, but possibly the ancient city of Barddhamana mentioned in a Jain source) near the junction of the Kunur and the Ajay in Barddhaman; Pokharna (ancient Pushkarana) on the south bank of the Damodar in Bankura opposite Panagarh in Barddhaman; Tamluk (ancient Tamralipta) on the bank of the Rupnarayan in Medinipur; Bangarh (ancient Bannagara) in the outskirts of Gangarampur bazar in West Dinajpur; and finally, Chandraketugarh, between Deganga and Basirhat in North Twentyfour Parganas. There were other places but one cannot count them among the frontrank centres.

Mahasthangarh was the capital of the ancient Pundra territory. Bangarh was the centre of a sub-division of the Pundra kingdom in the later inscriptions, but it could also be the capital of an independent kingdom in its early phase. Wari-Bateshwar is possibly Souanagoura of the Graeco-Roman sources and could be the centre of Samatata territory. Kotasur was the first capital of Gauda and Mangalkot was the capital of the northern part of Rarh. Pokharna was the centre of the southern Rarh and Tamluk was the capital of the Suhma territory. I believe Chandraketugarh to have been the capital of the ancient geographical territory of Vanga which was focussed on the eastern side of the Bhagirathi. I cannot foresee any other geographical explanation. Interestingly, Kotasur, Mangalkot, Pokharna and Tamluk were linked by an arterial route of Bengal linking the Bengal coast with north Bengal, Bihar and further north. However, the densest concentration of early historic sites in Bengal was in the Bhagirathi-Rupnarayan delta, especially in the Bhagirathi delta along the course of the Adi Ganga which can even now be traced up to the Sagar island which itself has a major early historic site. On Medinipur coast one can trace sites between Tamluk and Bahiri (near Kanthi). The total number of sites is about 15 or more. Excavations have been conducted marginally at 3/4 sites but the results lie unpublished. We know about them mostly through their antiquities found by the local people.

Why was there such a concentration of sites on the Bengal coast? A large part of the maritime trade of the Ganga plain used to pass through them. This trade was with southeast Asia and the Mediterranean. There is no archaeological object showing contact with southeast Asia, but in view of India's traditional links with the region, this can be inferred. The element of Mediterranean contact is far more visible, mainly in the terracottas showing Roman influence and in a complete amphora which I noted in a village near Kanthi. Chandraketugarh was connected with the flow of the sea-going traffic by a channel/river which joined the Adi Ganga near modern Sonarpur.

I do not expect people to agree with me on all points, but this is hopefully a coherent outline of the historical and archaeological context of Chandraketugarh.

htthttps://www.academia.edu/8133704/The_alleged_Kharosthi-Brahmi_mixed_script Harry Falk, 2013. “The Alleged Kharoṣṭhī‐Brāhmī Mixed Script and Some New Seals from Bengal.” Zeitschrift für Indologie und Südasienstudien 30: 105–24.

A bibliography on Chandraketugarh (Thanks to Ambarish Goswami)

|