Ancient History of Bhāratam Janam: Journeys tossed on the waves of Indian Ocean, ēlō ! -- on the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa: Evidence of Gold disc studded with Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/10583287/Ancient_History_of_Bh%C4%81ratam_Janam_Journeys_tossed_on_the_waves_of_Indian_Ocean_%C4%93l%C5%8D_--_on_the_Tin_Road_from_Hanoi_to_Haifa_Evidence_of_Gold_disc_studded_with_Meluhha_metalwork_hieroglyphs

Westward Ho! is a familiar American idiom to denote the journeys of people during the Gold Rush into California. A Meluhha synonym is a boatman's or navigators' song refrain: ēlō ! ēlēlō !! Meluhhan journeys are westward and eastward, southward and northward moving with the waves of perennial streams of Himalaya -- a majestic, dynamic range which spans the continent from Hanoi to Teheran forming a canpoy over the Indian Ocean. This āsetu-himācalam sets the space for Meluhha pilgrims' progress which started ca. 8th millennium BCE. As the dynamic mountain range -- देवतात्मा नगाधिराजः Dēvatātmā nagādhirājaḥ --continues to uplift the Eurasian plate, the water reservoir formed by snow and ice continues to grow about 1 cm. every year in size storing -- in glaciers -- all the monsoon waters which fall at heights of above 8000 ft. This inexorable plate tectonic uplift caused by unfathomable cosmic energy, defines the History of Bhāratam Janam in their relationship with material and environmental resources.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/ancient-history-of-bharatam-janam-along.html Ancient History of Bhāratam Janam along the Ancient Tin Road, which linked abundant stanniferous ores of the Far East (Hanoi) with Haifa (shipwreck tin ingots) of ancient Near East

The name Bhārata as a group identity of people, is traceable to bharat, alloy, metalcasters, philosophers of fire. bharatiyo 'metal casters' (Gujarati) भरत [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal

[The Meluhha ēlō ! refrain is attested in the ancient text Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (lit. a prayer text of hundred paths): te 'asura attavacasa he 'alava he''alava (ŚBr.3.2.1.22-24 as detailed below].

The gods reflected, 'Verily that Vâk is a woman: (it is to be feared) that she will [or, it is to be hoped that she will not] allure him [viz. so. that Yagña also would fall to the share of the Asuras]'--Say to her, "Come hither to me where I stand!" and report to us her having come.' She then went up to where he was standing. Hence a woman goes to a man who stays in a well-trimmed (house). He reported to them her having come, saying, 'She has indeed come.'

The gods then cut her off from the Asuras; and having gained possession of her and enveloped her completely in fire, they offered her up as a holocaust, it being an offering of the gods. And in that they offered her with an anushtubh verse, thereby they made her their own; and the Asuras, being deprived of speech, were undone, crying, 'He ’lavah! he ’lavah!'

Such was the unintelligible speech which they then uttered,--and he (who speaks thus) is a Mlekkha (barbarian). Hence let no Brahman speak barbarous language, since such is the speech of the Asuras. Thus alone he deprives his spiteful enemies of speech; and whosoever knows this, his enemies, being deprived of speech, are undone.

According to Sâyana, 'He ’lavo' stands for 'He ’rayo (i.e. ho, the spiteful (enemies))!' which the Asuras were unable to pronounce correctly. The Kânva text, however, reads, te hâttavâko ’surâ hailo haila ity etâm ha vâkam vadantah parâbabhûvuh; (? i, e. He ilâ, 'ho, speech.') A third version of this passage seems to be referred to in the Mahâbhâshya (Kielhorn, p.2.)

I submit that the early linguists were enthralled by the childlike, joyous ēlō ! refrain, but struggled to fathom the semantics of boatmen's carol or song refrain or seafaring Meluhhan celebrating their maritime, metallurgical adventures, explorations and experiments with production of alloys and casting tools, weapons, metalware and pots an pans which transformed their lives beyond imagination resulting in the Bronze Age Metals revolution and new social corporate formations in an extensive playground of trans-continental Eurasia.

Carol of Śr̥ṅgāra, fun, frolic, beauty, love, passion: ఏల [ ēla ] or ఏలా ēla. [Tel.] interrogative adv. Why, how, wherefore, to what end, for what reason.వేయేల (వేయి +వేల ) why say a thousand words? ఏల [ ēla ] ēla. [Tel.] n. A hurrah, or hoop. A carol or catch used by rowers of boats శృంగారపు పాట ."ఏటికట్టగుడిసెవేతాం ఏరువస్తే కూడాపోదాం ఓ, ఓ, గొల్లభామా !"(The books named గరుడాచలము, ఆటభాగవతము, పారిజాతము , &c. contain many specimens of these carols.) Also, a chorus of applause. ఏలపాటలు a kind of play, a game played by children బాలక్రీడావిశేషము . See P. ii. 132. ఏల [ ēla ] ēla. [Tel.] n. Name of a stream in the Godavery District ఏలేరు . (Telugu) ஏலப்பாட்டு ēla-p-pāṭṭu, n. < ஏலேலோ +. Boatmen's song in which the words ēlō, ēlēlō occur again and again; கப்பற்பாட்டு. (W .) ēla- is relatable semant. to 'sea waves' the song rhymes with the tossings of the boat on the waves and the 'splendour' of navigation: Kol. (Kin.) elava a wave. Go. (A.) helva id., flood (DEDR 830) Ta. el lustre, splendour, light, sun, daytime; elli, ellai sun, daytime; ilaku (ilaki-), ilaṅku (ilaṅki-) to shine, glisten, glitter. Ma. ilakuka to shine, twinkle; ilaṅkuka to shine; el lustre, splendour, light; ella light. Te. (K.) elamu to be shiny, splendid. (DEDR 829) See: lilām लिलाम् or nilām निलाम् m. (Hindī nīlām, Portuguese leilám), an auction, public sale (Gr.M.).(Kashmiri) ஏலம்³ ēlam , n. < Port. leilàoelamu, K. elām, M. ēlam.] Auction; போட்டி யிற் பலர்முன் ஏற்றும் விலை. The Portuguese gloss may relate to competitive rowing among a convoy of boats as they set out into the waters.

The Westward Elo! is a riverine navigation on the Himalayan rivers and mariime navigation along the Persian Gulf of the Indian Ocean (and the doab of Tigris-Euphrates) in a Maritime Tin Road from the Tin Belt (Vietnam region, hence designated by the capital Hanoi) to seaport of Haifa (Israel, not far from Nahal Mishmar) across the Mediterranean, with Cyprus (Enkomi) as the transit point.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/vedic-indians-in-iraq-in-5000-bce-and.html

Vedic Indians in Iraq in 5000 BCE and the rise of Sumerian Civilization -- P Priyadaarshi. History of Bharatam Janam has to cover space-time segment of this Bronze Age Tin Road -- Kalyan

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/10583287/Ancient_History_of_Bh%C4%81ratam_Janam_Journeys_tossed_on_the_waves_of_Indian_Ocean_%C4%93l%C5%8D_--_on_the_Tin_Road_from_Hanoi_to_Haifa_Evidence_of_Gold_disc_studded_with_Meluhha_metalwork_hieroglyphs

Westward Ho! is a familiar American idiom to denote the journeys of people during the Gold Rush into California. A Meluhha synonym is a boatman's or navigators' song refrain: ēlō ! ēlēlō !! Meluhhan journeys are westward and eastward, southward and northward moving with the waves of perennial streams of Himalaya -- a majestic, dynamic range which spans the continent from Hanoi to Teheran forming a canpoy over the Indian Ocean. This āsetu-himācalam sets the space for Meluhha pilgrims' progress which started ca. 8th millennium BCE. As the dynamic mountain range -- देवतात्मा नगाधिराजः Dēvatātmā nagādhirājaḥ --continues to uplift the Eurasian plate, the water reservoir formed by snow and ice continues to grow about 1 cm. every year in size storing -- in glaciers -- all the monsoon waters which fall at heights of above 8000 ft. This inexorable plate tectonic uplift caused by unfathomable cosmic energy, defines the History of Bhāratam Janam in their relationship with material and environmental resources.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/ancient-history-of-bharatam-janam-along.html Ancient History of Bhāratam Janam along the Ancient Tin Road, which linked abundant stanniferous ores of the Far East (Hanoi) with Haifa (shipwreck tin ingots) of ancient Near East

The name Bhārata as a group identity of people, is traceable to bharat, alloy, metalcasters, philosophers of fire. bharatiyo 'metal casters' (Gujarati) भरत [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal

'bhāratam janam', of the Chandas in Rigveda can be interpreted as 'bhārata folk' as in the ṛṣi's mantra:. viśvāmitrasya rakṣati brahmedam bhāratam janam RV 3.053.12. (Trans. This prayer, brahma, of viśvāmitra protects bhārata folk'.). I suggest that this phrase of self-designation, clear identity of the people as bhāratam janam is a reference to the artisans who had invented the new techniques of alloying metals and metal casting. Archaeological evidence from Nahal Mishmar is stunning. The artifacts found in a cave there were metal castings of exquisite artistry made using cire perdue (lost-wax casting) technique.

[The Meluhha ēlō ! refrain is attested in the ancient text Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (lit. a prayer text of hundred paths): te 'asura attavacasa he 'alava he''alava (ŚBr.3.2.1.22-24 as detailed below].

The gods reflected, 'Verily that Vâk is a woman: (it is to be feared) that she will [or, it is to be hoped that she will not] allure him [viz. so. that Yagña also would fall to the share of the Asuras]'--Say to her, "Come hither to me where I stand!" and report to us her having come.' She then went up to where he was standing. Hence a woman goes to a man who stays in a well-trimmed (house). He reported to them her having come, saying, 'She has indeed come.'

The gods then cut her off from the Asuras; and having gained possession of her and enveloped her completely in fire, they offered her up as a holocaust, it being an offering of the gods. And in that they offered her with an anushtubh verse, thereby they made her their own; and the Asuras, being deprived of speech, were undone, crying, 'He ’lavah! he ’lavah!'

Such was the unintelligible speech which they then uttered,--and he (who speaks thus) is a Mlekkha (barbarian). Hence let no Brahman speak barbarous language, since such is the speech of the Asuras. Thus alone he deprives his spiteful enemies of speech; and whosoever knows this, his enemies, being deprived of speech, are undone.

According to Sâyana, 'He ’lavo' stands for 'He ’rayo (i.e. ho, the spiteful (enemies))!' which the Asuras were unable to pronounce correctly. The Kânva text, however, reads, te hâttavâko ’surâ hailo haila ity etâm ha vâkam vadantah parâbabhûvuh; (? i, e. He ilâ, 'ho, speech.') A third version of this passage seems to be referred to in the Mahâbhâshya (Kielhorn, p.2.)

I submit that the early linguists were enthralled by the childlike, joyous ēlō ! refrain, but struggled to fathom the semantics of boatmen's carol or song refrain or seafaring Meluhhan celebrating their maritime, metallurgical adventures, explorations and experiments with production of alloys and casting tools, weapons, metalware and pots an pans which transformed their lives beyond imagination resulting in the Bronze Age Metals revolution and new social corporate formations in an extensive playground of trans-continental Eurasia.

Carol of Śr̥ṅgāra, fun, frolic, beauty, love, passion: ఏల [ ēla ] or ఏలా ēla. [Tel.] interrogative adv. Why, how, wherefore, to what end, for what reason.

The Westward Elo! is a riverine navigation on the Himalayan rivers and mariime navigation along the Persian Gulf of the Indian Ocean (and the doab of Tigris-Euphrates) in a Maritime Tin Road from the Tin Belt (Vietnam region, hence designated by the capital Hanoi) to seaport of Haifa (Israel, not far from Nahal Mishmar) across the Mediterranean, with Cyprus (Enkomi) as the transit point.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/vedic-indians-in-iraq-in-5000-bce-and.html

Vedic Indians in Iraq in 5000 BCE and the rise of Sumerian Civilization -- P Priyadaarshi. History of Bharatam Janam has to cover space-time segment of this Bronze Age Tin Road -- Kalyan

Priyadarshi has provided insights into the presence of Bharatam Janam (identified in the Rigveda) in Sumer, ca. 5000 BCE. These insights provide the imperative for narrating Itihasa of Bharatam Janam.

Given the recurrence of Indus Script hieroglyphs in Sumer/Mesopotamian sites including Jemdet-Nasr mentioned by Priyadarshi in his article (February 5, 2015 -- See Annex), it is clear that there were Meluhha settlements in Sumer/Mesopotamia. Meluhha was the spoken idiom, the lingua franca of the civilization attested by Indus Script corpora.

Mapping the Tin Road which rivaled the later-day Silk Road

See: http://bharatkalyan97.

The challenge for archaeology researchers, archaeometallurgists and students of civilization studies is to map the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa, considering that the world's largest resource for tin is the Tin Belt of Malaysian Peninsula, extending northwards into Northeast Bharatam (India) and eastwards into Vietnam. Meluhha were metalworkers of yore whose legacy is celebrated by Asur, the smelters of Bharatam and were the pioneers of cire perdue metal castingand tin-bronzes which created the Bronze Age revolution across Eurasia.

Evidence of Gold disc (Kuwait National Museum) with Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs is emphatic that Meluhha metalworkers were seafaring artisans and traders.

Evidence of Gold disc studded with Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs

The evidence is evaluated in the contexts of archaeo-metallurgy and use of Meluhha hieroglyphs in Indus writing system:

1. Processes for producing hard alloys to effectively deploy the cire perdue (lost-wax) technique of metal casting -- a multi-national enterprise which started ca. 5th millennium BCE (pace Nahal Mishmar evidence)

2. Metalwork Meluhha hieroglyphs such as ligatured eagle (pace Mesopotamia reliefs and Candi Suku reliefs), duck, pine-cone, flowering creeper, pillar/post, bucket/wallet -- to document catalogs of hard alloys (karaḍa), metal casting (dhokra) and 'fire-altar' (kaṇḍ).

See: https://www.academia.edu/8795289/Ligatured_eagle_pine-cone_and_other_metalwork_Meluhha_hieroglyphs Ligatured eagle, pine-cone and other metalwork Meluhha hieroglyphs

They had navigated the Persian Gulf during the Bronze Age cataloging their competence in metalwork and metal castings (using cire perdue or lost wax method of casting metal alloys).

The gold disc is, in effect, a catalogus catalogorum of Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs. It is a veritable mini-gallery of Meluhha hieroglyphs.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.html https://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture/photos/pb.369573056429568.-2207520000.1423199373./505466802840192/?

It will be interesting to obtain provenance information from the Museum and have experts evaluate the authenticity of the artifact.

Prima facie, the gold disk has hieroglyphs ALL of which occur on other Indus writing artifacts such as seals and tablets.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/01/stepped-socles-of-assur-meluhha.html

Stepped socles of Assur. Meluhha hieroglyphs of metalwork in Kar Tukulti Ninurta.

![]()

Gold disc. al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait National Museum. 9.6 cm diameter, which was obviously from the Indus Valley period in India. Typical of that period, it depicts zebu, bulls, human attendants, ibex, fish, partridges, bees, pipal free an animal-headed standard.

![]()

కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n.

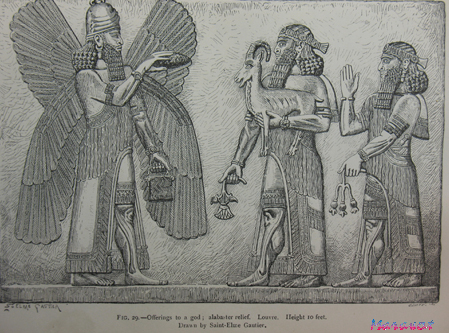

Ht. 10 feet.Alabaster relief in the Louvre. Drawing by Saint-Elme Gautier. Illustration for A History of Art in Chaldaea and Assyria by Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez (Chapman and Hall, 1884) The winged person, whose helmet has three sets of horns holds a raphia farinifera cone on his right palm. The person (perhaps a Meluhha) with antelope on his left arm appears to be holding a date cluster on his right hand; he is followed by a person holding a pomegrante cluster.

The relief presents a trade deal involving exchange of sharp metal tools with copper metal ingots from Meluhha.

mlekh 'goat' carried by him denotes the Meluhha merchant (dealing in) milakkhu 'copper'. The twig or sprig on his right hand: ḍhāḷā m. ʻsprig' meṛh 'mrchant's assistant' carries a cluster of pomegranates: ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' (Sindhi) Rebus: ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot' (Gujarati)

ḍāla1 m. ʻ branch ʼ Śīl. 2. *ṭhāla -- . 3. *ḍāḍha -- . [Poss. same as *dāla -- 1 and dāra -- 1 : √dal, √d&rcirclemacr; . But variation of form supports PMWS 64 ← Mu.]1. Pk. ḍāla -- n. ʻ branch ʼ; S. ḍ̠āru m. ʻ large branch ʼ, ḍ̠ārī f. ʻ branch ʼ; P. ḍāl m. ʻ branch ʼ, °lā m. ʻ large do. ʼ, °lī f. ʻ twig ʼ; WPah. bhal. ḍā m. ʻ branch ʼ; Ku. ḍālo m. ʻ tree ʼ; N. ḍālo ʻ branch ʼ, A. B. ḍāl, Or. ḍāḷa; Mth. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, °ri ʻ twig ʼ; Aw. lakh. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, H. ḍāl, °lā m., G. ḍāḷi , °ḷīf., °ḷũ n.2. A. ṭhāl ʻ branch ʼ, °li ʻ twig ʼ; H. ṭhāl, °lā m. ʻ leafy branch (esp. one lopped off) ʼ.3. Bhoj. ḍāṛhī ʻ branch ʼ; M. ḍāhaḷ m. ʻ loppings of trees ʼ, ḍāhḷā m. ʻ leafy branch ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ twig ʼ, ḍhāḷā m. ʻ sprig ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ branch ʼ.(CDIAL 5546). Rebus: ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā -- .1. Tir. (Leech) "dàl"ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B.ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f.. *ḍhāllā -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. -- a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f. (CDIAL 5583).

dalim 'the fruit of pomegranate, punica granatum, Linn.' (Santali) S. ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate'(CDIAL 6254). Gy. eur. darav ʻ pomegranate ʼ (GWZS 440).(CDIAL 14598). dāḍima m. ʻ pomegranate tree ʼ MBh., n. ʻ its fruit ʼ Suśr., dālima -- m. Amar., ḍālima -- lex. 1. Pa. dālima -- m., NiDoc. daḍ'ima, Pk. dāḍima -- , dālima -- n., dāḍimī -- f. ʻ the tree ʼ, Dm. dā̤ŕim, Shum. Gaw. dāˊṛim,Kal. dā̤ŕəm, Kho. dáḷum, Phal. dhe_ ṛum, S. ḍ̠āṛhū̃ m., P. dāṛū̃, °ṛū, °ṛam m., kgr. dariūṇ (= dariū̃?) m.; WPah.bhiḍ. de_ ṛũ n. ʻ sour pomegranate ʼ; (Joshi) dāṛū, OAw. dārivaṁ m., H. poet. dāriũ m., OG. dāḍimi f. ʻ the tree ʼ, G. dāṛam n., dāṛe m f. ʻ the tree ʼ, Si. deḷum.2. WPah.jaun. dāṛim, Ku. dā̆ṛim, dālim, dālimo, N. dārim, A. ḍālim, B. dāṛim, dālim, Or. dāḷimba, °ima, dāṛima,

ḍāḷimba,ḍarami ʻ tree and fruit ʼ; Mth. dāṛim ʻ pomegranate ʼ, daṛimī ʻ dried mango ʼ; H. dāṛimb, °im, dālim, ḍāṛim, ḍār°, ḍāl° m., M.dāḷĩb, °ḷīm, ḍāḷĩb n. ʻ the fruit ʼ, f. ʻ the tree ʼ.3. Sh.gil. daṇū m. ʻ pomegranate ʼ, daṇúi f. ʻ the tree ʼ, jij. ḍ*l ṇə́i, K. dönü m., P. dānū m.

dāḍima -- . 2. dāḍimba -- : Garh. dāḷimu ʻ pomegranate ʼ, A. ḍālim (phonet. d -- ).(CDIAL 6254).Ta. mātaḷai, mātuḷai, mātuḷam pomegranate. Ma. mātaḷam id. (DEDR 4809). தாதுமாதுளை tātu-mātuḷai , n. < id. +. Pomegranate, s. tr., Punica granatum; பூ மாதுளை. (யாழ். அக.)

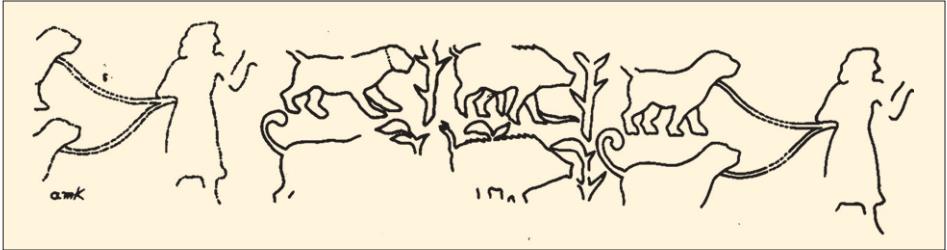

Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)![]() Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] or తంబురా tambura. [Tel. తంతి +బుర్ర .] n. A kind of stringed instrument like the guitar. A tambourine. Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.) tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'.

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of tin and copper.

![]() Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Hieroglyphs on this Dilmun seal are: star, tabernae montana flower, cock, two divided squares, two bulls, antelope, sprout (paddy plant), drinking (straw), stool, twig or tree branch. A person with upraised arm in front of the antelope. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus using lexemes (Meluhha, Mleccha) of Indiansprachbund.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

ṭagara (tagara) fragrant wood (Pkt.Skt.).tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi) dula 'pair' (Kashmiri). Rebus: dul 'cast metal' (Santali) Thus, a pair of bulls connote 'cast metal blacksmith'.

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali)

Tu. aḍaru twig. Rebus: aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal' (Kannada) Alternative reading: కండె [kaṇḍe] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Te.); eraka ‘copper’ (Te.)

Thus, the Dilmun seal is a metalware catalog of damgar 'merchant' dealing with copper and tin.

The two divided squares attached to the straws of two vases in the following seal can also be read as hieroglyphs:

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangā = small country boat, dug-out canoe (Or.); ḍõgā trough, canoe, ladle (H.)(CDIAL 5568). Rebus: ḍānro term of contempt for a blacksmith (N.); ḍangar (H.) (CDIAL 5524)

Thus, a smelting furnace for stone (ore) is connoted by the seal of a blacksmith, ḍangar

Ta. kara-tāḷam palmyra palm. Ka. kara-tāḷa fan-palm, Corypha umbraculifera Lin. Tu. karatāḷa cadjan. Te. (B.) kara-tāḷamu the small-leaved palm tree.(DEDR 1270). karukku teeth of a saw or sickle, jagged edge of palmyra leaf-stalk, sharpness (Ta.) Ka. garasu. / Cf. Skt. karaṭa- a low, unruly, difficult person; karkara- hard, firm; karkaśa- rough, harsh, hard; krakaca-, karapattra- saw; khara- hard, harsh, rough, sharp-edged; kharu- harsh, cruel; Pali kakaca- saw; khara- rough; saw; Pkt.karakaya- saw; Apabhraṃśa (Jasaharacariu) karaḍa- hard. Cf. esp. Turner, CDIAL, no. 2819. Cf. also Skt. karavāla- sword (for second element, cf. 5376 Ta. vāḷ). (DEDR 1265) Allograph: Ta. karaṭi, karuṭi, keruṭi fencing, school or gymnasium where wrestling and fencing are taught. Ka. garaḍi, garuḍi fencing school. Tu.garaḍi, garoḍi id. Te. gariḍi, gariḍī id., fencing.(DEDR 1262)

Allograph: eagle: garuḍá m. ʻ a mythical bird ʼ Mn. Pa. garuḷa -- m., Pk. garuḍa -- , °ula -- m.; P. garaṛ m. ʻ the bird Ardea argala ʼ; N. garul ʻ eagle ʼ, Bhoj. gaṛur; OAw. garura ʻ blue jay ʼ; H. garuṛ m. ʻ hornbill ʼ, garul ʻ a large vulture ʼ; Si. guruḷā ʻ bird ʼ (kurullā infl. by Tam.?). -- Kal. rumb. gōrvḗlik ʻ kite ʼ?? (CDIAL 4041). gāruḍa ʻ relating to Garuḍa ʼ MBh., n. ʻ spell against poison ʼ lex. 2. ʻ emerald (used as an antidote) ʼ Kālid. [garuḍá -- ]1. Pk. gāruḍa -- , °ula -- ʻ good as antidote to snakepoison ʼ, m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ, n. ʻ science of using such charms ʼ; H. gāṛrū, gārṛū m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ; M. gāruḍ n. ʻ juggling ʼ. 2. M. gāroḷā ʻ cat -- eyed, of the colour of cat's eyes ʼ.(CDIAL 4138). கருடக்கல் karuṭa-k-kal, n. < garuḍa. (Tamil)

Given the recurrence of Indus Script hieroglyphs in Sumer/Mesopotamian sites including Jemdet-Nasr mentioned by Priyadarshi in his article (February 5, 2015 -- See Annex), it is clear that there were Meluhha settlements in Sumer/Mesopotamia. Meluhha was the spoken idiom, the lingua franca of the civilization attested by Indus Script corpora.

The challenge for archaeology researchers, archaeometallurgists and students of civilization studies is to map the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa, considering that the world's largest resource for tin is the Tin Belt of Malaysian Peninsula, extending northwards into Northeast Bharatam (India) and eastwards into Vietnam. Meluhha were metalworkers of yore whose legacy is celebrated by Asur, the smelters of Bharatam and were the pioneers of cire perdue metal castingand tin-bronzes which created the Bronze Age revolution across Eurasia.

Evidence of Gold disc (Kuwait National Museum) with Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs is

emphatic that Meluhha metalworkers were seafaring artisans and traders.

Evidence of Gold disc studded with Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs

The evidence is evaluated in the contexts of archaeo-metallurgy and use of Meluhha hieroglyphs in Indus writing system:

1. Processes for producing hard alloys to effectively deploy the cire perdue (lost-wax) technique of metal casting -- a multi-national enterprise which started ca. 5th millennium BCE (pace Nahal Mishmar evidence)

2. Metalwork Meluhha hieroglyphs such as ligatured eagle (pace Mesopotamia reliefs and Candi Suku reliefs), duck, pine-cone, flowering creeper, pillar/post, bucket/wallet -- to document catalogs of hard alloys (karaḍa), metal casting (dhokra) and 'fire-altar' (kaṇḍ).

See: https://www.academia.edu/8795289/Ligatured_eagle_pine-cone_and_other_metalwork_Meluhha_hieroglyphs Ligatured eagle, pine-cone and other metalwork Meluhha hieroglyphs

The gold disc is, in effect, a catalogus catalogorum of Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs. It is a veritable mini-gallery of Meluhha hieroglyphs.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.html

Prima facie, the gold disk has hieroglyphs ALL of which occur on other Indus writing artifacts such as seals and tablets.

They had navigated the Persian Gulf during the Bronze Age cataloging their competence in

metalwork and metal castings (using cire perdue or lost wax method of casting metal alloys).

The gold disc is, in effect, a catalogus catalogorum of Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs. It is a veritable mini-gallery of Meluhha hieroglyphs.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.html

https://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture/photos/pb.369573056429568.-2207520000.1423199373./505466802840192/?

It will be interesting to obtain provenance information from the Museum and have experts evaluate the authenticity of the artifact.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/01/stepped-socles-of-assur-meluhha.html

Stepped socles of Assur. Meluhha hieroglyphs of metalwork in Kar Tukulti Ninurta.

Stepped socles of Assur. Meluhha hieroglyphs of metalwork in Kar Tukulti Ninurta.

Gold disc. al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait National Museum. 9.6 cm diameter, which was obviously from the Indus Valley period in India. Typical of that period, it depicts zebu, bulls, human attendants, ibex, fish, partridges, bees, pipal free an animal-headed standard.

కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n.

Ht. 10 feet.Alabaster relief in the Louvre. Drawing by Saint-Elme Gautier. Illustration for A History of Art in Chaldaea and Assyria by Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez (Chapman and Hall, 1884) The winged person, whose helmet has three sets of horns holds a raphia farinifera cone on his right palm. The person (perhaps a Meluhha) with antelope on his left arm appears to be holding a date cluster on his right hand; he is followed by a person holding a pomegrante cluster.

The relief presents a trade deal involving exchange of sharp metal tools with copper metal ingots from Meluhha.

mlekh 'goat' carried by him denotes the Meluhha merchant (dealing in) milakkhu 'copper'. The twig or sprig on his right hand: ḍhāḷā m. ʻsprig' meṛh 'mrchant's assistant' carries a cluster of pomegranates: ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' (Sindhi) Rebus: ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot' (Gujarati)

ḍāla1 m. ʻ branch ʼ Śīl. 2. *ṭhāla -- . 3. *ḍāḍha -- . [Poss. same as *dāla -- 1 and dāra -- 1 : √dal, √d&rcirclemacr; . But variation of form supports PMWS 64 ← Mu.]1. Pk. ḍāla -- n. ʻ branch ʼ; S. ḍ̠āru m. ʻ large branch ʼ, ḍ̠ārī f. ʻ branch ʼ; P. ḍāl m. ʻ branch ʼ, °lā m. ʻ large do. ʼ, °lī f. ʻ twig ʼ; WPah. bhal. ḍā m. ʻ branch ʼ; Ku. ḍālo m. ʻ tree ʼ; N. ḍālo ʻ branch ʼ, A. B. ḍāl, Or. ḍāḷa; Mth. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, °ri ʻ twig ʼ; Aw. lakh. ḍār ʻ branch ʼ, H. ḍāl, °lā m., G. ḍāḷi , °ḷīf., °ḷũ n.2. A. ṭhāl ʻ branch ʼ, °li ʻ twig ʼ; H. ṭhāl, °lā m. ʻ leafy branch (esp. one lopped off) ʼ.3. Bhoj. ḍāṛhī ʻ branch ʼ; M. ḍāhaḷ m. ʻ loppings of trees ʼ, ḍāhḷā m. ʻ leafy branch ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ twig ʼ, ḍhāḷā m. ʻ sprig ʼ, °ḷī f. ʻ branch ʼ.(CDIAL 5546). Rebus: ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā -- .1. Tir. (Leech) "dàl"ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B.ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f.. *ḍhāllā -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. -- a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f. (CDIAL 5583).

dalim 'the fruit of pomegranate, punica granatum, Linn.' (Santali)S. ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate'(CDIAL 6254). Gy. eur. darav ʻ pomegranate ʼ (GWZS 440).(CDIAL 14598). dāḍima m. ʻ pomegranate tree ʼ MBh., n. ʻ its fruit ʼ Suśr., dālima -- m. Amar., ḍālima -- lex. 1. Pa. dālima -- m., NiDoc. daḍ'ima, Pk. dāḍima -- , dālima -- n., dāḍimī -- f. ʻ the tree ʼ, Dm. dā̤ŕim, Shum. Gaw. dāˊṛim,Kal. dā̤ŕəm, Kho. dáḷum, Phal. dhe_ ṛum, S. ḍ̠āṛhū̃ m., P. dāṛū̃, °ṛū, °ṛam m., kgr. dariūṇ (= dariū̃?) m.; WPah.bhiḍ. de_ ṛũ n. ʻ sour pomegranate ʼ; (Joshi) dāṛū, OAw. dārivaṁ m., H. poet. dāriũ m., OG. dāḍimi f. ʻ the tree ʼ, G. dāṛam n., dāṛe m f. ʻ the tree ʼ, Si. deḷum.2. WPah.jaun. dāṛim, Ku. dā̆ṛim, dālim, dālimo, N. dārim, A. ḍālim, B. dāṛim, dālim, Or. dāḷimba, °ima, dāṛima,

mlekh 'goat' carried by him denotes the Meluhha merchant (dealing in) milakkhu 'copper'. The twig or sprig on his right hand: ḍhāḷā m. ʻsprig' meṛh 'mrchant's assistant' carries a cluster of pomegranates: ḍ̠āṛhū̃ 'pomegranate' (Sindhi) Rebus: ḍhālako 'a large metal ingot' (Gujarati)

ḍāla

dalim 'the fruit of pomegranate, punica granatum, Linn.' (Santali)

ḍāḷimba,ḍarami ʻ tree and fruit ʼ; Mth. dāṛim ʻ pomegranate ʼ, daṛimī ʻ dried mango ʼ; H. dāṛimb, °im, dālim, ḍāṛim, ḍār°, ḍāl° m., M.dāḷĩb, °ḷīm, ḍāḷĩb n. ʻ the fruit ʼ, f. ʻ the tree ʼ.3. Sh.gil. daṇū m. ʻ pomegranate ʼ, daṇúi f. ʻ the tree ʼ, jij. ḍ*l ṇə́i, K. dönü m., P. dānū m.

dāḍima -- . 2. dāḍimba -- : Garh. dāḷimu ʻ pomegranate ʼ, A. ḍālim (phonet. d -- ).(CDIAL 6254).Ta. mātaḷai, mātuḷai, mātuḷam pomegranate. Ma. mātaḷam id. (DEDR 4809). தாதுமாதுளை tātu-mātuḷai , n. < id. +. Pomegranate, s. tr., Punica granatum; பூ மாதுளை. (யாழ். அக.)

Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] or

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of tin and copper.

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]Hieroglyphs on this Dilmun seal are: star, tabernae montana flower, cock, two divided squares, two bulls, antelope, sprout (paddy plant), drinking (straw), stool, twig or tree branch. A person with upraised arm in front of the antelope. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus using lexemes (Meluhha, Mleccha) of Indiansprachbund.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

ṭagara (tagara) fragrant wood (Pkt.Skt.).tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi) dula 'pair' (Kashmiri). Rebus: dul 'cast metal' (Santali) Thus, a pair of bulls connote 'cast metal blacksmith'.

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali)

Tu. aḍaru twig. Rebus: aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal' (Kannada) Alternative reading: కండె [kaṇḍe] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Te.); eraka ‘copper’ (Te.)

Thus, the Dilmun seal is a metalware catalog of damgar 'merchant' dealing with copper and tin.

The two divided squares attached to the straws of two vases in the following seal can also be read as hieroglyphs:

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangā = small country boat, dug-out canoe (Or.); ḍõgā trough, canoe, ladle (H.)(CDIAL 5568). Rebus: ḍānro term of contempt for a blacksmith (N.); ḍangar (H.) (CDIAL 5524)

Thus, a smelting furnace for stone (ore) is connoted by the seal of a blacksmith, ḍangar

Ta. kara-tāḷam palmyra palm. Ka. kara-tāḷa fan-palm, Corypha umbraculifera Lin. Tu. karatāḷa cadjan. Te. (B.) kara-tāḷamu the small-leaved palm tree.(DEDR 1270). karukku teeth of a saw or sickle, jagged edge of palmyra leaf-stalk, sharpness (Ta.) Ka. garasu. / Cf. Skt. karaṭa- a low, unruly, difficult person; karkara- hard, firm; karkaśa- rough, harsh, hard; krakaca-, karapattra- saw; khara- hard, harsh, rough, sharp-edged; kharu- harsh, cruel; Pali kakaca- saw; khara- rough; saw; Pkt.karakaya- saw; Apabhraṃśa (Jasaharacariu) karaḍa- hard. Cf. esp. Turner, CDIAL, no. 2819. Cf. also Skt. karavāla- sword (for second element, cf. 5376 Ta. vāḷ). (DEDR 1265) Allograph: Ta. karaṭi, karuṭi, keruṭi fencing, school or gymnasium where wrestling and fencing are taught. Ka. garaḍi, garuḍi fencing school. Tu.garaḍi, garoḍi id. Te. gariḍi, gariḍī id., fencing.(DEDR 1262)

Allograph: eagle: garuḍá m. ʻ a mythical bird ʼ Mn. Pa. garuḷa -- m., Pk. garuḍa -- , °ula -- m.; P. garaṛ m. ʻ the bird Ardea argala ʼ; N. garul ʻ eagle ʼ, Bhoj. gaṛur; OAw. garura ʻ blue jay ʼ; H. garuṛ m. ʻ hornbill ʼ, garul ʻ a large vulture ʼ; Si. guruḷā ʻ bird ʼ (kurullā infl. by Tam.?). -- Kal. rumb. gōrvḗlik ʻ kite ʼ?? (CDIAL 4041). gāruḍa ʻ relating to Garuḍa ʼ MBh., n. ʻ spell against poison ʼ lex. 2. ʻ emerald (used as an antidote) ʼ Kālid. [garuḍá -- ]1. Pk. gāruḍa -- , °ula -- ʻ good as antidote to snakepoison ʼ, m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ, n. ʻ science of using such charms ʼ; H. gāṛrū, gārṛū m. ʻ charm against snake -- poison ʼ; M. gāruḍ n. ʻ juggling ʼ. 2. M. gāroḷā ʻ cat -- eyed, of the colour of cat's eyes ʼ.(CDIAL 4138). கருடக்கல் karuṭa-k-kal, n. < garuḍa. (Tamil)

Depiction of an annunaki in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Hieroglyph composition of an eagle-faced winged person also carried a pine-cone in his right hand; a basket or wallet is held in the left hand. Assyrian) alabaster Height: 236.2 cm (93 in). Width: 135.9 cm (53.5 in). Depth: 15.2 cm (6 in). This relief decorated the interior wall of the northwest palace of King Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. http://www.cuttingedge.org/articles/RC125.htm

Hieroglyph: pine-cone: கண்டபலம் kaṇṭa-palam, n. < kaṇṭa கண்டம்¹ kaṇṭam

Hieroglyphs: kandə ʻpineʼ, ‘ear of maize’. Rebus: kaṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans of metal’. Rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’. Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298).

Some examples of Indus Script hieroglyphs in Jemde Nasr and other sites of Sumer/Mesopotamia are given below. Each of the hieroglyphs can also be read rebus as Meluhha metalwork catalogs.

Hieroglyphs: kandə ʻpineʼ, ‘ear of maize’. Rebus: kaṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans of metal’. Rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’. Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298).

Some examples of Indus Script hieroglyphs in Jemde Nasr and other sites of Sumer/Mesopotamia are given below. Each of the hieroglyphs can also be read rebus as Meluhha metalwork catalogs.

l![]() Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk

Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk![]()

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1999.325.4 (Bos gaurus shown with greater clarity) Sumerian (Late Uruk/Jemdet Nasr Period) Black Stetatite Cylinder Seal http://art.thewalters.org/viewwoa.aspx?id=33263 In the two scenes on this cylinder seal, a heroic figure with heavy beard and long curls holds off two roaring lions, and another hero struggles with a water buffalo. The inscription in the panel identifies the owner of this seal as "Ur-Inanna, the farmer."![]() Tailless lion or bear standing erect behind tree; two goats feeding at other side of tree; another tree, with bird in branches, behind monster; three-towered building with door at left side; watercourse along bottom of scene. Kafaje, Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BC) . Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/Images/oip72/oip72_0034l.jpg

Tailless lion or bear standing erect behind tree; two goats feeding at other side of tree; another tree, with bird in branches, behind monster; three-towered building with door at left side; watercourse along bottom of scene. Kafaje, Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BC) . Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/Images/oip72/oip72_0034l.jpg

![]() Girdled nude hero attacking water buffalo;Chlorite Bull Cup, Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr, circa 3300-2900

Girdled nude hero attacking water buffalo;Chlorite Bull Cup, Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr, circa 3300-2900![]() c.3200-3000 B.C. Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr periodMagnesite. Cylinder seal

c.3200-3000 B.C. Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr periodMagnesite. Cylinder seal![]() Tell Asmar cylinder impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE.

Tell Asmar cylinder impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE.![]() Cylinder seal impression of Ibni-Sharrum, a scribe of Shar Kalisharri, ca. 2183–2159 BCE The inscription reads “O divine Shar-kali-sharri, Ibni-sharrum the scribe is your servant.” Cylinder seal. Chlorite. AO 22303 H. 3.9 cm. Dia. 2.6 cm

Cylinder seal impression of Ibni-Sharrum, a scribe of Shar Kalisharri, ca. 2183–2159 BCE The inscription reads “O divine Shar-kali-sharri, Ibni-sharrum the scribe is your servant.” Cylinder seal. Chlorite. AO 22303 H. 3.9 cm. Dia. 2.6 cm

S. Kalyanaraman February 7, 2015 Sarasvati Research Center![]() The road between Assur and Kanesh is presented in http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/12/tin-road-between-ashur-kultepe-and.html

The road between Assur and Kanesh is presented in http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/12/tin-road-between-ashur-kultepe-and.html

l![]() Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk

Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk

Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk

Fragment of a bowl with a frieze of bulls in relief. Period: Late Uruk

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1999.325.4 (Bos gaurus shown with greater clarity) Sumerian (Late Uruk/Jemdet Nasr Period) Black Stetatite Cylinder Seal http://art.thewalters.org/viewwoa.aspx?id=33263 In the two scenes on this cylinder seal, a heroic figure with heavy beard and long curls holds off two roaring lions, and another hero struggles with a water buffalo. The inscription in the panel identifies the owner of this seal as "Ur-Inanna, the farmer."

Tailless lion or bear standing erect behind tree; two goats feeding at other side of tree; another tree, with bird in branches, behind monster; three-towered building with door at left side; watercourse along bottom of scene. Kafaje, Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BC) . Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.

Tailless lion or bear standing erect behind tree; two goats feeding at other side of tree; another tree, with bird in branches, behind monster; three-towered building with door at left side; watercourse along bottom of scene. Kafaje, Jemdet Nasr (ca. 3000 - 2800 BC) . Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 34.http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/Images/oip72/oip72_0034l.jpg

Girdled nude hero attacking water buffalo;Chlorite Bull Cup, Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr, circa 3300-2900

Girdled nude hero attacking water buffalo;Chlorite Bull Cup, Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr, circa 3300-2900Magnesite. Cylinder seal

Tell Asmar cylinder impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE.

Tell Asmar cylinder impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE.S. Kalyanaraman

February 7, 2015 Sarasvati Research Center

The road between Assur and Kanesh is presented in http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/12/tin-road-between-ashur-kultepe-and.html

n

n

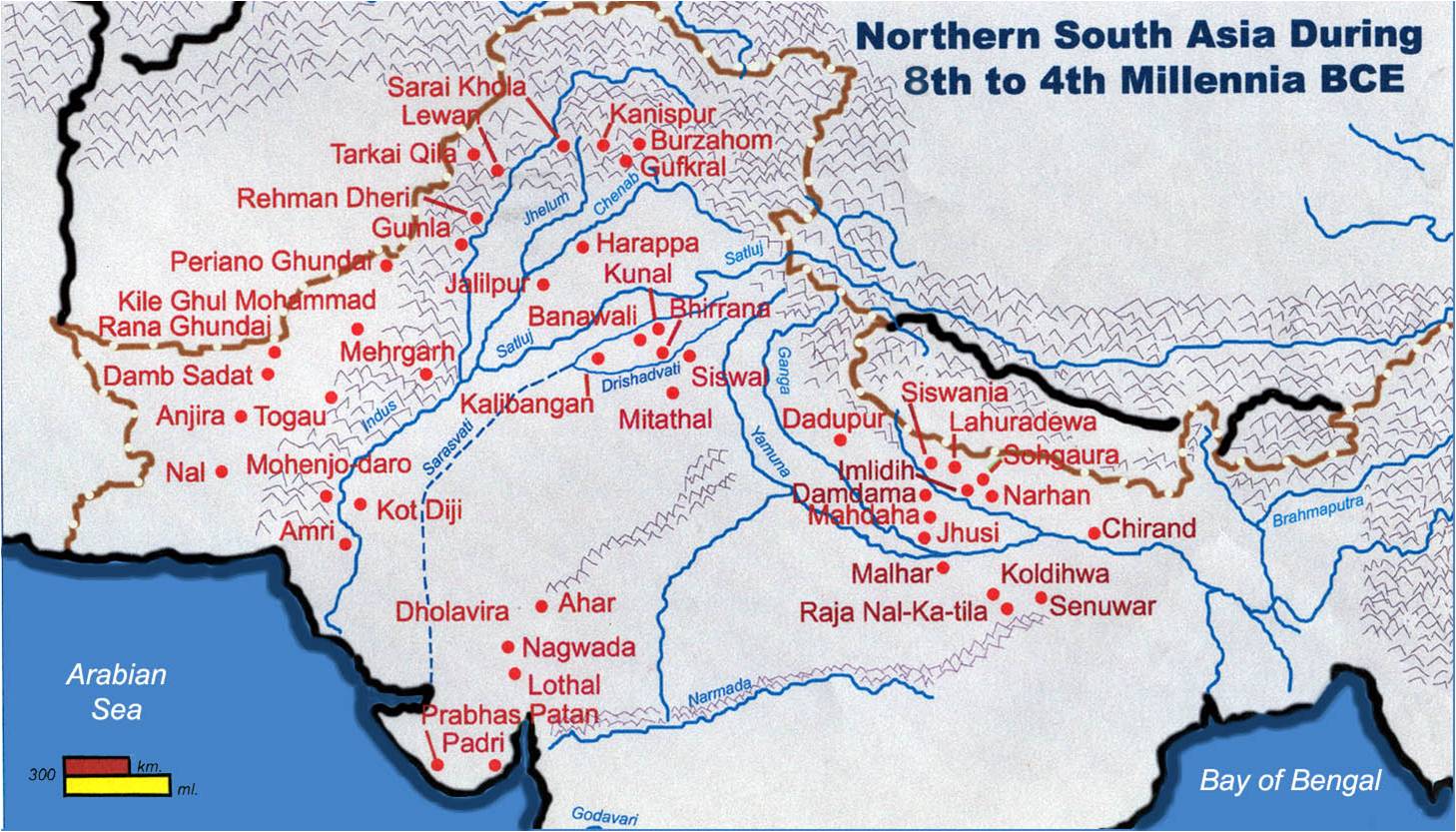

Indian Civilization emerged in the 8th millennium BCE in Ghaggar-Hakra and Baluchistan area.

The roots of the Indian Civilization in 8th millennium BCE (and cultural continuum into historical periods) was suggested by BR Mani and KN Dikshit in an International Conference held in Chandigarh from 27th to 29th October, 2012. The suggestion was based on archaeological reports and chronological dating of sites such as Mehrgarh in Baluchistan, Rehman Dheri in Gomal plains, Jalilpur and Harappa in Punjab, Bhirrana, Baror, Sothi, Nohar, Siswal, Banawali, Kalibangan, Girawad and Rakhigarhi in India.

The cultural remains of Bhirrana (a site on the Sarasvati/Ghaggar-Hakra river valley) date from 7380 BC to 6201 BCE and represent Hakra Ware Culture. Hakra Ware was also attested in the Hakra river basin of Cholistan sites by excavation of sites such as Ganweriwala and Bahawalpur.

These dates of Bhirrana are contemporaneous with C14 dates of 8th-7th millennium BCE of Mehergarh. Continuity of cultural horizon in Bhirrana has been noted upto 1800 BCE suggesting that the ‘Lost’ Sarasvati/Ghaggar-Hakra was the cradle of Indian civilization .

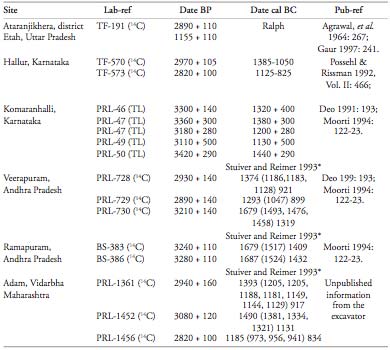

The date 1800 BCE is significant in the context of the Ganga River valley of Indian civilization. In the sites of Dadupur, Lahuradewa, Malhar, Raja Nal-ka-tila, iron smelting activities have been attested with the remains of a smelter discovered, dated to ca. 1800 BCE. (Rakesh Tewari, 2003,The origins of iron-working in India: new evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and the Eastern Vindhyas

http://antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/tewari/tewari.pdf

Tewari, R., RK Srivastava & KK Singh, 2002, Excavation at Lahuradewa, Dist. Sant Kabir Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, Puratattva 32: 54-62).

http://antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/tewari/tewari.pdf

Tewari, R., RK Srivastava & KK Singh, 2002, Excavation at Lahuradewa, Dist. Sant Kabir Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, Puratattva 32: 54-62).

Dates for early iron use from Indian sites (After Table 1. Rakesh Sinha opcit.)

Technologies used in Mehergarh (5500 - 3500 BCE) included stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns and copper melting crucibles.

Nageshwar: Fire altar (After Fig. 3 in Nagaraja Rao, MS, 1986).

Large updraft kiln of the Harappan period (ca. 2400 BCE) found during excavations on Mound E Harappa, 1989 (After Fig. 8.8, Kenoyer, 2000). See: Discussion on stone structures in Dholavira: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html

Large updraft kiln of the Harappan period (ca. 2400 BCE) found during excavations on Mound E Harappa, 1989 (After Fig. 8.8, Kenoyer, 2000). See: Discussion on stone structures in Dholavira: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html Lothal. Bead-making kiln. Rao,S.R. 1979. Lothal--A Harappan Port Town 1955-62, Vol. I. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.; Rao, S.R. 1985. Lothal--A Harapan Port Town 1955-62. Vol. II. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Lothal. Bead-making kiln. Rao,S.R. 1979. Lothal--A Harappan Port Town 1955-62, Vol. I. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.; Rao, S.R. 1985. Lothal--A Harapan Port Town 1955-62. Vol. II. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Harappa. Bead makers' kiln where the heat was distributed equally to all the holes. The 8-shaped stone structure indicates that this is a bead-maker's kiln. The 8-shaped stone structures with an altar or stone stool in the middle can thus be explained functionally as an anvil used by the bead makers to drill holes through beads and to forge material including metal artifacts.

Harappa. Bead makers' kiln where the heat was distributed equally to all the holes. The 8-shaped stone structure indicates that this is a bead-maker's kiln. The 8-shaped stone structures with an altar or stone stool in the middle can thus be explained functionally as an anvil used by the bead makers to drill holes through beads and to forge material including metal artifacts.Vitrified kiln walls were discovered in Harappa.

Harappa. Kiln (furnace) 1999, Mound F, Trench 43: Period 5 kiln, plan and section views.

Damaged circular clay furnace, comprising iron slag and tuyeres and other waste materials stuck with its body, exposed at lohsanwa mound, Period II, Malhar, Dist. Chandauli. (After Rakesh Sinha opcit.)

Damaged circular clay furnace, comprising iron slag and tuyeres and other waste materials stuck with its body, exposed at lohsanwa mound, Period II, Malhar, Dist. Chandauli. (After Rakesh Sinha opcit.)The Sindhu-Sarasvati river valley Indian civilization life-activities of metalwork thus continues into the Ganga river valley. The extension of the civilization into the third river valley of Brahmaputra (another perennial Himalayan river system) is as yet an open question subject to archaeological confirmation. The mapping of bronze age sites along the eastern and northeastern parts of India and extending into the Burma, Malay Peninsula and eastwards upto Vietnam (coterminus with the Austro-Asiatic language speaking communities along the Himalayan rivers of Irrawaddy, Salween and Mekong) point to the possibility that the transition of chalco-lithic cultures into the Bronze-iron age (or Metal Alloys age) was a continuum traceable from Mehergarh to Hanoi (Vietnam).

This continuum of metalwork as a principal life-activity (and trade) may also explain the remarkable discovery of the Bronze Age site of Ban Chiang in Thailand (dated to early 2nd millennium BCE). It should be noted that the site of Ban Chiang is proximate to the largest reserves of Tin (cassiterite) ore in the world which stretched along a massive mineral resource belt in Malay Peninsula into the Northeast India (Brahmaputra river valley). The chronological sequencing of metalworking with tin is an archaeometallurgical challenge which archaeologists and metallurgicals have to unravel in a multi-disciplinary endeavour.

The exploration metalwork in the in Northeastern India, in Brahmaputra river valley can relate to the remarkable fire-altar discovered in Uttarakashi:

Syena-citi: A Monument of Uttarkashi Distt. Fire-altar shaped like a falcon.

Excavated site (1996): Purola Geo-Coordinates-Lat. 30° 52’54” N Long. 77° 05’33” E "The ancient site at Purola is located on the left bank of river Kamal. The excavation yielded the remains of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) from the earliest level alongwith other associated materials include terracotta figurines, beads, potter-stamp, the dental and femur portions of domesticated horse (Equas Cabalus Linn). The most important finding from the site is a brick alter identified as Syenachiti by the excavator. The structure is in the shape of a flying eagle Garuda, head facing east with outstretched wings. In the center of the structure is the chiti is a square chamber yielded remains of pottery assignable to circa first century B.C. to second century AD. In addition copper coin of Kuninda and other material i.e. ash, bone pieces etc and a thin gold leaf impressed with a human figure tentatively identified as Agni have also been recovered from the central chamber.Note: Many ancient metallic coins (called Kuninda copper coins) were discovered at Purola. cf. Devendra Handa, 2007, Tribal coins of ancient India, ISBN: 8173053170, Aryan Books International."

Excavated site (1996): Purola Geo-Coordinates-Lat. 30° 52’54” N Long. 77° 05’33” E "The ancient site at Purola is located on the left bank of river Kamal. The excavation yielded the remains of Painted Grey Ware (PGW) from the earliest level alongwith other associated materials include terracotta figurines, beads, potter-stamp, the dental and femur portions of domesticated horse (Equas Cabalus Linn). The most important finding from the site is a brick alter identified as Syenachiti by the excavator. The structure is in the shape of a flying eagle Garuda, head facing east with outstretched wings. In the center of the structure is the chiti is a square chamber yielded remains of pottery assignable to circa first century B.C. to second century AD. In addition copper coin of Kuninda and other material i.e. ash, bone pieces etc and a thin gold leaf impressed with a human figure tentatively identified as Agni have also been recovered from the central chamber.Note: Many ancient metallic coins (called Kuninda copper coins) were discovered at Purola. cf. Devendra Handa, 2007, Tribal coins of ancient India, ISBN: 8173053170, Aryan Books International."

Cauldron Protome of Winged Ibexes. Bronze, Almaty Region, 5th - 3rd century B.C.E. CEntral State Museum, Almaty. Courtesy Central State Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Almaty.

Cauldron Fragment Depicting Saiga Antelope in Relief. Copper Alloy, Almaty, 5th - 3rd century B.C.E. Central State Museum, Almaty. Courtesy Central State Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Almaty.

Feline Face and Stylized Wood, and Tin and Gold Foil, H. 9.0; W. 6.0; D. 1.6 cm Berel, Kurgan 11, late 4th–early 3rd century bce Presidential Center of Culture, Astana: 5581. Almaty Museum, Kazakhstan.

http://mongolschinaandthesilkroad.blogspot.in/2012/02/nomads-and-networks-in-kazakhstan.html

![Splendors of the Ancient East]()

![]()

Gold cylinder seal. Mid 3rdmillennium BCE. Height 2.21 cm. dia 2.74 cm. Gold shee with chased decoration. Inv. No. LNS 4517J. “…two scenes: the first depicts a bull-headed god with huge inward curving horns, large ears, massive biceps and a long beard facing forward with an eight-petal rosette between his horns. On either side is a human-headed bird, walking towards the god but its head facing away. Flanking both birds are undulating open-mouthed snakes and scorpions. The second scene is arranged around a vegetation goddess with long hair. Bare-chested but wearing a flounced skirt, she sits with her legs tucked under her skirt on the backs of two addorsed ibexes that turn back to look at each other. Between the rumps of the ibexes below the goddess is a pile of lozenges perhaps representing a mountain. Heavy foliage of branches and leaves springs from her sides and fills the upper register, and to her upper left is a crescent moon. The elements depicted reflect mythological figures seen on chlorite vessels from Bactria-Margiana in northern central Asia to Tepe Yahya, Jiroft and other sites in southeastern Iran and down to the Gulf.”

Source: http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Splendour-Exhibition-Brochure.pdf

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-legacy_6.htmlAncient Near East bronze-age legacy: Processions depicted on Narmer palette, Indus writing denote artisan guilds

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-scarf-hieroglyph-on.html Ancient Near East 'scarf' hieroglyph on Warka vase, cyprus bronze stand and on Indus writing

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-evidence-for-mleccha.htmlAncient Near East evidence for meluhha language and bronze-age metalware

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-indus-writing-lokhad.html Ancient near East Gudea statue hieroglyph (Indus writing): lokhãḍ, 'copper tools, pots and pans' Rebus: lo 'overflow', kāṇḍa 'sacred water'.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-ziggurat-and-related.htmlAncient Near East ziggurat and related hieroglyphs in writing systems

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.htmlAncient Near East: Traditions of smelters, metallurgists validate the Bronze Age Linguistic Doctrine.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/ancient-near-east-transition-fro-bullae.htmlAncient Near East archaeological context: transition to Bronze Age. Indus writing is for trade in this transition.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/ancient-near-east-shahdad-bronze-age.htmlAncient Near East: Shahdad bronze-age inscriptional evidence, a tribute to Ali Hakemi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/bhirrana-8th-millennium-bce-on-river.htmlBhirrana & Rakhigarhi: From 8th millennium BCE. Archaeological sites linked by River Sarasvati.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/location-of-marhashi-and-cheetah-from.htmlLocation of Marhashi and cheetah from Meluhha: Shahdad & Tepe Yahya are in Marhashi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/shahdad-standard-meluhha-smithy-catalog.htmlShahdad standard: Meluhha smithy catalog of Shahdad, Marhashi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-heralded.htmlAncient Near East Bronze Age -- heralded by Meluhha writing

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/bronze-age-kanmer-bagasra.htmlBronze Age Meluhha, smithy/lapidary documents, takṣat vāk, incised speech

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-overflowing-pot-hieroglyph.htmlMeluhha 'overflowing pot' hieroglyph. Meluhha-Susa-Marhashi interconnections

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.htmlMeluhha: spread of lost-wax casting in the Fertile Crescent. Smithy is the temple. Veneration of ancestors.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-dhokra-art-from-5th-millennium.htmlMeluhha dhokra art from 5th millennium BCE at Nahal (Nachal) Mishmar, transiting into Bronze Age

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-standard-compares-with-nahal.htmlMeluhha standard compares with Nahal Mishmar standard. Meluhha (Asur) guild processions.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/susa-pot-meluhha-hieroglyph-indian.htmlSusa pot, 'fish' Meluhha hieroglyph, metalware contents and the Tin Road reinforce Indian sprachbund of proto-Prākṛts

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-snarling-iron-of.htmlSnarling iron, fish, crocodile and anthropomorph Meluhha hieroglyphs of Bronze Age

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/assur-as-meluhha-speakers-asura-some.htmlAssur as Meluhha speakers, Asura, some divinities venerated in Rigveda.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.htmlIdentity of Ancient Meluhha blacksmiths, using archaeometallurgy and cryptography in a socio-cultural context

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/meluhha-metallurgy-hieroglyphs-of.htmlMeluhha metallurgy: hieroglyphs of pomegranate, mangrove date-palm cone (raphia farinifera), an elephant's head terracotta Nausharo, Sarasvati civilization

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/tin-road-assur-kanesh-trade.htmlTin road -- Assur-Kanesh -- trade transactions and Meluhha hieroglyphs

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/continuity-in-hieroglyph-motifs-from.htmlContinuity in hieroglyph motifs from Meluhha to Ancient Near East

Copper alloy and silver standing nude male supporting openwork basket. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 115 cm. width 33 cm. Figure of arsenical copper with silver head, lost-wax cast, with engraved details; with attached silver sidelocks; inlaid shell eye. Inv. No LNS 1654 M.

Gold cylinder seal. Mid 3rdmillennium BCE. Height 2.21 cm. dia 2.74 cm. Gold shee with chased decoration. Inv. No. LNS 4517J. “…two scenes: the first depicts a bull-headed god with huge inward curving horns, large ears, massive biceps and a long beard facing forward with an eight-petal rosette between his horns. On either side is a human-headed bird, walking towards the god but its head facing away. Flanking both birds are undulating open-mouthed snakes and scorpions. The second scene is arranged around a vegetation goddess with long hair. Bare-chested but wearing a flounced skirt, she sits with her legs tucked under her skirt on the backs of two addorsed ibexes that turn back to look at each other. Between the rumps of the ibexes below the goddess is a pile of lozenges perhaps representing a mountain. Heavy foliage of branches and leaves springs from her sides and fills the upper register, and to her upper left is a crescent moon. The elements depicted reflect mythological figures seen on chlorite vessels from Bactria-Margiana in northern central Asia to Tepe Yahya, Jiroft and other sites in southeastern Iran and down to the Gulf.”

Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. l. 47 cm. width 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical copper and then joined by casting; left-eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forhead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern) Inv. No. LNS 1653 M. Splendour Exhibition Brochure. Kuwaiti Museum.

Source: http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Splendour-Exhibition-Brochure.pdf

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/indus-writing-on-dilmun-type-seals.htmlIndus writing in ancient Near East (Failaka seal readings)

sal ‘bos gaurus’; rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali) Vikalpa 1: ran:gā ‘buffalo’; ran:ga ‘pewter or alloy of tin (ran:ku), lead (nāga) and antimony (añjana)’(Santali) Vikalpa 2: kaṭamā ‘bison’ (Ta.)(DEDR 1114) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. Kaḍa-i-o = (Skt. Sthapati, a mason) a bricklayer, mason (G.)]

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-legacy_6.htmlAncient Near East bronze-age legacy: Processions depicted on Narmer palette, Indus writing denote artisan guilds

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-scarf-hieroglyph-on.html Ancient Near East 'scarf' hieroglyph on Warka vase, cyprus bronze stand and on Indus writing

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-evidence-for-mleccha.htmlAncient Near East evidence for meluhha language and bronze-age metalware

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-indus-writing-lokhad.html Ancient near East Gudea statue hieroglyph (Indus writing): lokhãḍ, 'copper tools, pots and pans' Rebus: lo 'overflow', kāṇḍa 'sacred water'.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-ziggurat-and-related.htmlAncient Near East ziggurat and related hieroglyphs in writing systems

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.htmlAncient Near East: Traditions of smelters, metallurgists validate the Bronze Age Linguistic Doctrine.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/ancient-near-east-transition-fro-bullae.htmlAncient Near East archaeological context: transition to Bronze Age. Indus writing is for trade in this transition.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/ancient-near-east-shahdad-bronze-age.htmlAncient Near East: Shahdad bronze-age inscriptional evidence, a tribute to Ali Hakemi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/bhirrana-8th-millennium-bce-on-river.htmlBhirrana & Rakhigarhi: From 8th millennium BCE. Archaeological sites linked by River Sarasvati.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/location-of-marhashi-and-cheetah-from.htmlLocation of Marhashi and cheetah from Meluhha: Shahdad & Tepe Yahya are in Marhashi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/shahdad-standard-meluhha-smithy-catalog.htmlShahdad standard: Meluhha smithy catalog of Shahdad, Marhashi

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-heralded.htmlAncient Near East Bronze Age -- heralded by Meluhha writing

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/bronze-age-kanmer-bagasra.htmlBronze Age Meluhha, smithy/lapidary documents, takṣat vāk, incised speech

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-overflowing-pot-hieroglyph.htmlMeluhha 'overflowing pot' hieroglyph. Meluhha-Susa-Marhashi interconnections

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.htmlMeluhha: spread of lost-wax casting in the Fertile Crescent. Smithy is the temple. Veneration of ancestors.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-dhokra-art-from-5th-millennium.htmlMeluhha dhokra art from 5th millennium BCE at Nahal (Nachal) Mishmar, transiting into Bronze Age

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-standard-compares-with-nahal.htmlMeluhha standard compares with Nahal Mishmar standard. Meluhha (Asur) guild processions.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/susa-pot-meluhha-hieroglyph-indian.htmlSusa pot, 'fish' Meluhha hieroglyph, metalware contents and the Tin Road reinforce Indian sprachbund of proto-Prākṛts

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-snarling-iron-of.htmlSnarling iron, fish, crocodile and anthropomorph Meluhha hieroglyphs of Bronze Age

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/assur-as-meluhha-speakers-asura-some.htmlAssur as Meluhha speakers, Asura, some divinities venerated in Rigveda.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/identity-of-ancient-meluhha-blacksmiths.htmlIdentity of Ancient Meluhha blacksmiths, using archaeometallurgy and cryptography in a socio-cultural context

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/meluhha-metallurgy-hieroglyphs-of.htmlMeluhha metallurgy: hieroglyphs of pomegranate, mangrove date-palm cone (raphia farinifera), an elephant's head terracotta Nausharo, Sarasvati civilization

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/tin-road-assur-kanesh-trade.htmlTin road -- Assur-Kanesh -- trade transactions and Meluhha hieroglyphs

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/continuity-in-hieroglyph-motifs-from.htmlContinuity in hieroglyph motifs from Meluhha to Ancient Near East

Rebus readings of Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs on Kuwait Museum gold disc

In the context of the bronze-age, the hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha) speech as metalware catalogs.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-as-metalware-catalogs-and_21.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/tokens-and-bullae-evolve-into-indus.html

See examples of Dilmun seal readings at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html

See examples of Sumer Samarra bowls: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-writing-in-ancient-near-east.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-as-metalware-catalogs-and_21.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/tokens-and-bullae-evolve-into-indus.html

See examples of Dilmun seal readings at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html

See examples of Sumer Samarra bowls: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-writing-in-ancient-near-east.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.html

Failaka/Dilmun seals with Meluhha hieroglyphs

Failaka/Dilmun seals with Meluhha hieroglyphs

Inventory No. 8480 A seal from Dilmun, soft stone, Failaka Island. 0.16x4.8 cm. ca. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/04/revisiting-ayo-ayas-barbar-temple-seals.htmlRevisiting ayo, ayas, Barbar temple seals, dhokra kamar, 'cire perdue' specialists and Meluhha hieroglyphs

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-glyphs-and-writing-in.htmlBronze-age glyphs and writing in ancient Near East: Two cylinder seals from Sumer

kaṇḍ ‘buffalo’; rebus: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore)’. Meluhha was the habitat for the water-buffalo.

Santali dictionary lexemes: ran(g) 'pewter'. ranga conga 'thorny, spikey, armed with spikes or thorns; ranga conga janumana 'it is armed with thorns'; ranga hari 'the name of a Santal godlet'. rangaini 'a common prickly plant, solanum xanthocarpum, schrad et Wendl.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.htmlIndus writing on gold disc, Kuwait Museum al-Sabah collection: An Indus metalware catalog

The hieroglyphs on the Kuwait Museum gold disc can be read rebus:

1. A pair of tabernae montana flowers tagara 'tabernae montana' flower; rebus: tagara 'tin'

2. A pair of rams tagara 'ram'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

3. Ficus religiosa leaves on a tree branch (5) loa 'ficus leaf'; rebus: loh 'metal'. kol in Tamil meanspancaloha 'alloy of five metals'.

4. A pair of bulls tethered to the tree branch: ḍhangar 'bull'; rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith'

Two persons touch the two bulls: meḍ ‘body’ (Mu.) Rebus: meḍ‘iron’ (Ho.) Thus, the hieroglyph composition denotes ironsmiths.

5. A pair of antelopes looking back: krammara 'look back'; rebus: kamar 'smith' (Santali); tagara 'antelope'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

6. A pair of antelopes mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Mu.)

7. A pair of combs kã̄gsī f. ʻcombʼ (Gujarati); rebus 1: kangar ‘portable furnace’ (Kashmiri); rebus 2: kamsa 'bronze'.

8. A pair of fishes ayo 'fish' (Mu.); rebus: ayo 'metal, iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Sanskrit)

9.A pair of buffaloes tethered to a post-standard: ran:gā ‘buffalo’; ran:ga ‘pewter or alloy of tin (ran:ku), lead (nāga) and antimony (añjana)’(Santali) AN.NAKU 'tin' (Akkadian) Alternative: kāṛā ‘buffalo’ கண்டி kaṇṭi buffalo bull (Tamil); rebus: kaṇḍ 'stone ore'; kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

10. A pair of birds కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n. Alternative: कोळी kōḷī 'an aquatic bird' (Marathi) Rebus: kol 'working in iron' (Tamil) Hieroglyph 1: kōḍi. [Tel.] n. A fowl, a bird. (Telugu) Rebus: khōṭ ‘alloyed ingots’. Rebus 2: kol ‘the name of a bird, the Indian cuckoo’ (Santali) kol 'iron, smithy, forge'. Rebus 3: baṭa = quail (Santali) Rebus: baṭa = furnace, kiln (Santali) bhrāṣṭra = furnace (Skt.) baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (G.)

11. A post-standard with curved horns on top of a stylized 'eye' with one-horn on either side of two faces

A segment from the bottom register of the gold disc which creates a stylized 'eye' atop a stand or flagstaff with two ligatured 'faces' back-to-back and adorned by curling horns (of a ram or markhor). The stand is flanked by two buffaloes and two birds.

A segment from the bottom register of the gold disc which creates a stylized 'eye' atop a stand or flagstaff with two ligatured 'faces' back-to-back and adorned by curling horns (of a ram or markhor). The stand is flanked by two buffaloes and two birds.mũh‘face’; rebus: mũh‘ingot’ (Mu.)

ṭhaṭera ‘buffalo horns’. ṭhaṭerā ‘brass worker’ (Punjabi)

dol‘eye’; Rebus: dul‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali)

kandi‘hole, opening’ (Ka.)[Note the eye shown as a dotted circle on many Dilmun seals.]; kan‘eye’ (Ka.); rebus: kandi (pl. –l) necklace, beads (Pa.);kaṇḍ 'stone ore'

khuṇḍʻtethering peg or post' (Western Pahari) Rebus: kūṭa‘workshop’; kuṭi= smelter furnace (Santali); Rebus 2: kuṇḍ 'fire-altar'

Why are animals shown in pairs?

dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Mu.)

Thus, all the hieroglyphs on the gold disc can be read as Indus writing related to one bronze-age artifact category: metalware catalog entries.

Pre-cuneiform tablet with seal impressions

Fig. 24 Line drawing showing the seal impression on this tablet. Illustration by Abdallah Kahil.Proto-Cuneiform tablet with seal impressions. Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3100-2900 BCE. Mesopotamia. Clay H. 5.5 cm; W.7 cm.

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been:

Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or. tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m. (CDIAL 5779) Rebus: tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?] Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.) tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō (CDIAL 5779) tabāshīr तबाशीर् ।त्वक््क्षीरी f. the sugar of the bamboo, bamboo-manna (a siliceous deposit on the joints of the bamboo) (Kashmiri)

Source: Kim Benzel, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic and Edith W. Watts, 2010, Art of the Ancient Near East, a resource for educators, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

http://www.metmuseum.org/~/media/Files/Learn/For%20Educators/Publications%20for%20Educators/Art%20of%20the%20Ancient%20Near%20East.pdf

http://www.metmuseum.org/~/media/Files/Learn/For%20Educators/Publications%20for%20Educators/Art%20of%20the%20Ancient%20Near%20East.pdf

Annex

Vedic Indians in Iraq in 5000 BCE and the rise of Sumerian Civilization

by P Priyadaarshi 5 February 2015

Sumer was located in South Iraq where the rivers Tigris and Euphrates produce marshland in the region just before the delta. The region was dry and hot yet usually got flooded by the end of the harvesting season from the water coming down both the rivers. The catchment area of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were fed by the winter monsoon, usually leaving snow on the mountains to melt at spring season. Hence the floods came just about the end of the winter or beginning of the summer, when barley was due to be harvested, and destroyed the crops. This had kept the region in perpetual the economic darkness, until some new technology appropriate to the climate arrived here.

Before 4000 BC, the people were hunter-gatherers in this fish, bird and small game rich region. Uruk was one of the oldest cities of Sumer, which suddenly emerged about 4000 BC (radiocarbon-14 date; Crawford 2004:23). There is evidence that the Sumerian Civilization at this time with the help of an agro-pastoral economy which relied heavily on the domestic water-buffaloes and Indian cattle for the cultivation of rice in the marshy lands and water logged areas. Aquatic breeds of rice grow well in the water-logged lands of the marshes, and they are harvested in autumn, i.e. much before the winter monsoon. Water-buffaloes are happy to live in the marshes and their bulls pull the ploughs and the carts well.

Indian Buffalo in Sumer

While the linguistic comparisons had not thrown any light on this Indo-Sumerian connection, recent DNA studies have clarified a lot. The three viz. the buffalo, the cattle and rice had migrated to Sumer from northwest India between 5000 BC and 4000 BC, giving rise to a new economy which led the region into the earliest phase of urbanization and subsequently larger state formation. Marshall identified the water-buffalo in many Sumerian pictographs and texts, and also the Indian wild bull Bos gaurus in a tablet (No. 312) excavated from Jemdet Nasr near Kish (Marshall 1996:453). These tablets also clarified that the Sumerians used horse at least since 2600 BC as has been depicted in the pictograms (anšu-kur, the mountain-ass, or ‘Iranian ass’; because mountain = Zagros of Iran in Sumer). Sir John Marshall mentions that the water-buffalo disappeared from Sumer at about 2300 BC, during the period of the King Sargon of Akkad (Marshall 1996:453). This can be expected because there had been a general trend of aridity in the third millennium reaching its peak at 2200 BC (4.2 Kilo Event). Water buffaloes cannot survive dry hot climates.

While the linguistic comparisons had not thrown any light on this Indo-Sumerian connection, recent DNA studies have clarified a lot. The three viz. the buffalo, the cattle and rice had migrated to Sumer from northwest India between 5000 BC and 4000 BC, giving rise to a new economy which led the region into the earliest phase of urbanization and subsequently larger state formation. Marshall identified the water-buffalo in many Sumerian pictographs and texts, and also the Indian wild bull Bos gaurus in a tablet (No. 312) excavated from Jemdet Nasr near Kish (Marshall 1996:453). These tablets also clarified that the Sumerians used horse at least since 2600 BC as has been depicted in the pictograms (anšu-kur, the mountain-ass, or ‘Iranian ass’; because mountain = Zagros of Iran in Sumer). Sir John Marshall mentions that the water-buffalo disappeared from Sumer at about 2300 BC, during the period of the King Sargon of Akkad (Marshall 1996:453). This can be expected because there had been a general trend of aridity in the third millennium reaching its peak at 2200 BC (4.2 Kilo Event). Water buffaloes cannot survive dry hot climates.

It is known by now that the water-buffalo was domesticated in India in the eastern part of the country which was kept wetter by the Bay of Bengal monsoon and the winter monsoon during the Early Holocene (Satish Kumar 2007; Pal 2008:275; Thomas 1995:31-2; Groves 2006). In fact there is “evidence that both river and swamp buffaloes decent from one domestication event, probably in the Indian subcontinent.” (Kierstein 2004). It is at the very earliest Neolithic period that the water-buffalo had reached Mehrgarh as domestic animal (Possehl 202:27; J.F. Jarrige 2008:143; Costantini 2008:168). In northwest India, Mehrgarh received most of its rains from northern monsoon called the winter monsoon, which was strong then and hence the buffaloes could thrive at Mehrgarh as evident from the archaeology. In fact the Mehrgarh region was wet enough to support not only the water-buffalo, but also elephant, rhinoceros, swamp-deer and wild pig which prefer to live in the wetlands (Costantini 2008:168).