Imprints of the Past -- an archaeological outline of Northeast India

Author : B.S.Hari Shankar

2015 Rs. 175.

Book may be obtained from:

Book may be obtained from:

| Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture, Riverside, Uzanbzar, MG Road Guwahati Assam 781001 India info@vkic.org 91-361-2510594 http://www.vkic.org The highlights of the book: The write-up with 70 tables and 12 figures situates Northeast Bharatam as an extension of eastern Ganga plains. Four Veda shakhas have been identified based on inscriptional evidence. |

Imprints of the Past explores the archaeological wealth of northeast India from Quaternary Period. It brings to focus the beginnings of agriculture and domestication, trade and technology as well as Great Buddhist Monastic complexes of eastern India and their function in the cultural synthesis of Ganga-Brahmaputra Valley. The study comprehensively incorporates Maurya, Gupta and Post Gupta sites as well as rock cut cave temples, public architecture, water management, stone and bronze images, inscriptions, coins, paintings and manuscripts supplemented with considerable tables and maps. The cultural interaction with Nepal, Tibet, Myanmar, China and southeast Asia is interesting. On a wider canvas the book discusses appoaches of colonial anthropology and agenda of their contemporary propagandists who attempt to culturally bifurcate northeast India as a separate geo-cultural entity. Extensive archaeological evidence contend that northeast India can no longer be perceived as an isolated zone detached from Greater India.

Book Released on 31st January by Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture, Guwahati

The book by Hari Shankar is a signal contribution to the imperative of studying the Ancient Tin Road traversed by Bharatam Janam.

Archaeological studies of northeast Bharat will unravel the link between the Far East and Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization of the bronze age.

Such researches will take the civilization studies forward to provide a narrative of Itihasa of Bharatam Janam (self-identification attested in the Rigveda by Viswamitra).

Such a narrative will complement George Coedes' magnum opus:Histoire ancienne desEtats hindouises

Northeast Bharatam on the Tin Road from Hanoi to Haifa is the transit point for transmission (including Bali Yatra) of Meluhha traditions to the contact area of the Far East.

Kalyanaraman

VKIC FOUNDATION DAY

01/31/2015 17:00

Asia/Calcutta

Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture

cordially invites you with family and friends

to celebrate the

cordially invites you with family and friends

to celebrate the

VKIC Foundation Day, 2015

The Chief Guest

Sri V V Bhat, IAS [Retd]

Renowned Scholar and Former Member (Finance) Space Commission,

Atomic Energy Commission and Earth Commission.

Sri V V Bhat, IAS [Retd]

Renowned Scholar and Former Member (Finance) Space Commission,

Atomic Energy Commission and Earth Commission.

Will confer

The VKIC Sanman 2015

On

Sri Ramkuiwangbe Newme

President, Zeliangrong Heraka Association, Nagaland, Manipur & Assam.

President, Zeliangrong Heraka Association, Nagaland, Manipur & Assam.

And release Two Seminal Publications

Imprints of the Past – An Archaeological Outline of Northeast India by Dr BS Harishankar

Keertanam [Translation of the Keertan Ghosa of Srimanta Sankaradeva] by Dr Maheswar Hazarika

Keertanam [Translation of the Keertan Ghosa of Srimanta Sankaradeva] by Dr Maheswar Hazarika

Cultural Presentation

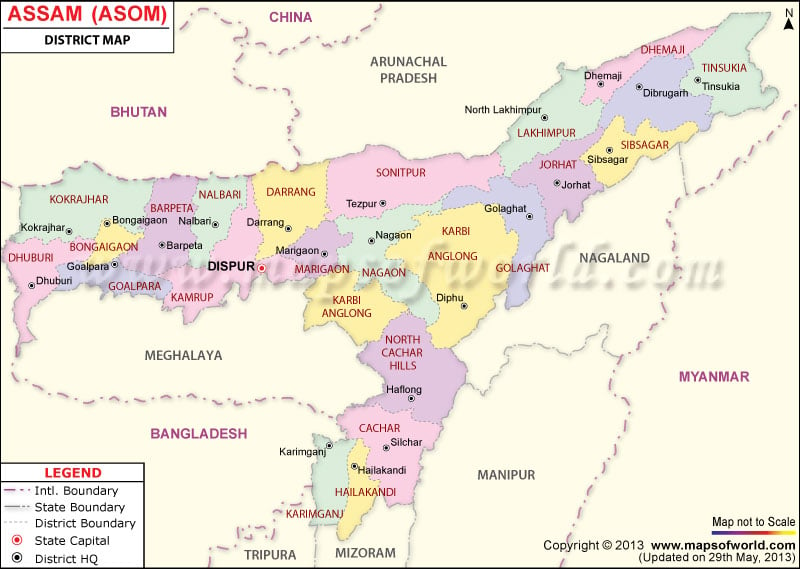

Rabha Community Manchalenka Cultural Group, Goalpara district, Assam.

Rabha Community Manchalenka Cultural Group, Goalpara district, Assam.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/02/munda-language-and-people.html

Munda: language and people

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0001141

Austro-Asiatic Tribes of Northeast India Provide Hitherto Missing Genetic Link between South and Southeast Asia

Pinnow’s map of Austro-AsiaticLanguage speakers correlates with bronze age sites. http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/faculty/stampe/aa.html See http://kalyan97.googlepages.com/mleccha1.pdf

Bronze Age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2.Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6.Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa;8. Mohenjo-daro; 9.Ahar; 10. Kayatha; 11.Navdatoli; 12.Inamgaon; 13. Non PaWai; 14. Nong Nor;15. Ban Na Di andBan Chiang; 16. NonNok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

See: Indian hieroglyphs, meluhha and archaeo-metallurgy

See: The Neolithic Cultures of Northeast India and ... Hazarika, Manjil. 2008a. ArchaeologicalResearch in Northeast India

Submitted by Daya Nath Singh on

The Archaeological Survey of India as a part of its 150th anniversary celebrations organized a two days regional conference on archaeology of North Eastern India recently in Guwahati. Scholars from Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur Meghalaya and Nagaland participated in the celebrations.

The earliest inhabitants of the northeastern region are assigned to the middle Pleistocene period as attested with the findings of paleoliths from its different arts including Daphabum area of Lohit district in Arunachal Pradesh, Khangkhui cave site, Songbu and Tharon cave of Manipur, Tilla site in Tripura, Rongram Valley of Garo Hills, Meghalaya. The region has also attested the prevalence of upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic cultures. The Mesolithic culture is not very prominent in the entire north-eastern part of the subcontinent whereas the upper Paleolithic culture is followed by occurrence of characteristic Hoabinhian culture akin to same assemblage of China and South-east Asia. The region under discussion also had a rich presence of megaliths occurring in the form of raised upright monoliths or menhirs and horizontally laid table stones. The tradition of erecting the megaliths is still continued in many parts of the region among the Naga, Khasi, Jaintia and Karbi tribes.

Since these findings occur in isolation from hilly terrain and flood plains amidst deep forest they are mostly secondary in nature and their cultural horizon is to be assessed in chronological frame work. A scientific dating is also to be probed which is the need of the hour. The data obtained by various scholars on the prehistoric researches assist in evolving a chronological frame work pertaining to the North-east region.

Since these findings occur in isolation from hilly terrain and flood plains amidst deep forest they are mostly secondary in nature and their cultural horizon is to be assessed in chronological frame work. A scientific dating is also to be probed which is the need of the hour. The data obtained by various scholars on the prehistoric researches assist in evolving a chronological frame work pertaining to the North-east region.

As far as historical archaeology is concerned, there are very few sites found excavated in this region as yet. Recently structural evidence encountered at Ambari excavation in Guwahati from the lowest level appears to be of Sunga-Kushana period. It is first time that an antiquity of the site has been pushed back to the Sunga-Kushana period in the region. However, the water logging at this level hampered further probing. Since the region is referred in epics and Purana’s as Pragjyotishpur occurrence of material culture pertaining to the much earlier period in further excavations cannot be ruled out.

The workshop aimed to delve upon the recent prehistoric and historical investigations carried out by various eminent scholars in this region. It made them to share and interact with each other their valued opinions, views and theories and also assisted in establishing well defined chorological frame work pertaining to the prehistoric and historic times prevailed upon in bygone era in this region.

In the inaugural session Regional Director (Eastern region),T J Baidya welcomed the participants. Dr Gautam Sengupta, DG,ASI, New Delhi stressed on need to improve the coordination with the local communities and research scholars towards better preservation of the historical monuments situated in various parts of the northeastern region. Addressing the participants as the chief guest Prof J N Phukan of Gauhati University suggested for the need of taking aggressive and affirmative action from the side of Archaeological Survey of India to stop encroachments near the centrally protected monuments. In the presidential address, ASI, New Delhi, Director A K Sinha emphasized the need of including more monuments/sites from the NE region in the centrally protected list.

On the first day of workshop ten papers were presented. A K Sharma, Archaeological Adviser, in culture department, Govt of Chhattisgarh presented his paper titled Heritage of North East India which highlighted the rich archaeological heritage of NE India as evident from the excavations at Sekta in Manipur, Bhaitbari in West Garo Hills district of Meghalaya and explorations conducted in Nagaland. Dr Promita Das of Gauhati University in her paper Historical archaeology of Kaili-Jamuna valley of Assam presented a glimpse of the material remains I the form of temple ruins, stone and terracotta sculptures of an ancient flourishing kingdom in the Kapili- Jamuna valley. Dr Projit Kumar Palit of Assam University, Silchar described the inscriptional evidences regarding the patronage of Buddhism in early North East India in his paper Inscriptions of Tripura: a Root of Buddhism in Early North-East India. Dr Watijungshi Jamir, of Kohima Science College , Nagaland in his paper Megalithic Monuments of the Angami Nagas presented the living megalithic traditions among the Angami Nagas. Dr M Manibabu, of Manipur University in his paper Pottery making ceramic ecology and system paradigm; an example of Processual.

Archaeological study from Manipur attempted to identify a series of feedback mechanisms related with the culture as well as the environment that favors or limits to the origin, development and continuity of the craft of pot making among an indigenous mongoloid population inhabited in the valley of Manipur, the Andro. A search for recurrent associated elements within the structured symbolic practice of erecting megaliths in Cherrapunjee in relation to their contextual meaning was presented by Dr Sukanya Sharma, of IIT, Guwahati in her paper Megaliths of Cherrapunjee. In his paper Some collections of

Terracotta Plaques, panels and art Motifs in the archeological museum, Sri Suryapahar, Bimal Sinha of Sri Suryapahar Archaeological Museum showed the terracotta plaques and art motifs preserved in the Archaeological Museum, Sri Suryapahar in Goalpara district of Assam which throw light on different cultural aspects of life as depicted in these plaques during the historical past in the region. Dr Aokumla Walling, of Nagaland university highlighted the relationship between oral tradition and archaeology in Nagaland in identification of archaeological sites.. Arup Bordoloi of Srimanta Shankardev Kalakshetra presented a paper on Buddhism in north east India and a few significant monuments from Assam. Dr Ceicil Mawlong, of NEHU, Shillong highlighted different types of Khasi Megaliths I her paper Khasi Megaliths: Problems and Prospects.

In the second day of academic session eleven papers were presented. Prof Alok Tripathi of Assam University, Silchar presented a paper on Archaeological Excavations in northeast India in twentieth century. Prof L Kunjeswori Devi of Manipur University presented the prehistoric archaeological remain in her paper recent discoveries of stone age culture of Kathong Hill Range, Chandel, Manipur. Dr Vinay Kumar of ASI, New Delhi presented his paper on Megalithic Culture of Northeast India. Dr H N Dutta, director, directorate of Archaeology, Assam gave a brief outline of the rock-cut caves excavated along the course of the river Brahmaputra in Assam in his paper rock-cut caves along the River Brahmaputra. Dr Tiatoshi Jamir, highlighted the potential of a community based archaeology in Nagaland from his recent work at Chungliyimit in Tuensang district of Nagaland in his paper ancestral sites, Local communities and Archaeology in Nagaland: Towards a collaborative Archaeology at Chungliyimit. The other papers presented were A Preliminary investigation at Tiyi Longchum Wokha, Nagaland by Dr R Chumbeno Nagullie, Japfu Christian College, Kohima, Stone age culture of Arunachal Pradesh by Dr Tage Tada, of Arunachal Pradesh Nayarit Deori of Arunachal Pradesh Megalithic Tradition in Nagaland: A study among the Lotha Nagas of Wokha district by Dr Jonali Devi of Cotton College, Guwahati Ethno-Archaeology of Shell fishing and Lime Production :Prospect for North-East by Dr Tilok Thakuria of NEHU, Archaeology of the Sacred contextualizing Ganesha in early Assam by Dr Rena Laisram of Gauhati University. The two day conference concluded with valedictory function chaired by Dr R D Choudhury, former DG, National Museum, New Delhi

Genetic watersheds on the Great Himalayas

One of the great geological landmarks on earth are the Himalayas. Not only are the Himalayas of importance in the domain of physical geography, but they are important in human geography as well. Just as South Asians and non-South Asians agree that the valley of the Indus and its tributaries bound the west of the Indian cultural world, so the Himalayas bound it on the north. Unlike many pre-modern constructions, such as the eastern boundaryof Europe, the northern limit of South Asia is relatively clear and distinct. It is stark on a relief map; the flat Gangetic plain gives way to mountains. And it is stark a cultural map, the languages of northern India give way to those of the world of Tibet. The religion of northern India gives way to the Buddhism of Tibet. In terms of human geography I believe that one can argue that the Himalayan fringe around South Asia exhibits the greatest change of ancestrally informative gene frequencies over the smallest distance when you exclude those regions separated by water barriers. Unlike the Sahara the transect from the northern India to Chinese Tibet at any given point along the border is permanently inhabited, albeit sparsely at the heights.

From the above figure it’s clear that there is considerable admixture among the Indo-European populations of Nepal with a Tibetan element. The Magar are a tribe which is representative of Tibet, with little South Asian genetic input presumably. The Newar are the Nepalese hybrids par excellence. To a great extent they can be viewed as the indigenous peoples of the Kathmandu region at the heart of modern Nepal. Their language is of Tibetan affinity, and yet it is heavily overlain with an Indo-Aryan aspect, and seems to have within it an ancient Austro-Asiatic substrate. Though predominantly Hindu today, the Newar have a substantial Buddhist minority whose roots may go back to the original Mahayana traditions which were once prominent in northern India. The Brahmin and Chetri groups are upper caste communities who claim provenance from the north Indian plain. Some of these upper caste groups in Nepal are of recent vintage, having fled the Islamic conquests of the Gangetic plain within the last 1,000 years. And yet even they have obvious Tibetan admixture.This should make one cautious about the excessive claims to genetic purity which South Asian caste groups make.

From the above figure it’s clear that there is considerable admixture among the Indo-European populations of Nepal with a Tibetan element. The Magar are a tribe which is representative of Tibet, with little South Asian genetic input presumably. The Newar are the Nepalese hybrids par excellence. To a great extent they can be viewed as the indigenous peoples of the Kathmandu region at the heart of modern Nepal. Their language is of Tibetan affinity, and yet it is heavily overlain with an Indo-Aryan aspect, and seems to have within it an ancient Austro-Asiatic substrate. Though predominantly Hindu today, the Newar have a substantial Buddhist minority whose roots may go back to the original Mahayana traditions which were once prominent in northern India. The Brahmin and Chetri groups are upper caste communities who claim provenance from the north Indian plain. Some of these upper caste groups in Nepal are of recent vintage, having fled the Islamic conquests of the Gangetic plain within the last 1,000 years. And yet even they have obvious Tibetan admixture.This should make one cautious about the excessive claims to genetic purity which South Asian caste groups make.But admixture of a Tibetan or East Asian component in South Asia is not limited to Nepal. I have reedited a figure from a 2006 paper on Indian Americans which shows the inferred components of ancestry of various language-groups. It is clear that the northeastern groups, Bengalis, Assamese, and Oriya, have an affinity to East Asians. This is not just ancient east Eurasian ancestry, the “Ancestral South Indians” hypothesized in Reich et al.. The South Indian groups (which I have excised from the figure) do not exhibit the same level of elevation of the ancestral quantum dominant among the Han Chinese in the bar plot. In fact the Reich et al. paper also reported evidence of an eastern ancestral element in some of the Munda speaking groups of northeast India. This stands to reason as the Munda are a South Asian branch of the Austro-Asiatic family of Southeast Asia. But much of it may also be more recent, as groups such as the Ahom of Assam and the Chakma of Bangladesh seem to have arrived from Burma of late.

So we see that genes do flow around the margins of South Asia, and into it. And yet Tibet seems oddly insulated. Why? Because of adaptation. Like water, it seems in this case genes tend to flow downhill, not up, and the reason is likely the fitness differentials between lowland and highland populations along the slope of the Great Himalayas. A new paper in PNASexplores the issue by examining genetic variation among Indians, Tibetans, and worldwide populations, in relation to hypoxia implicated loci. EGLN1involvement in high-altitude adaptation revealed through genetic analysis of extreme constitution types defined in Ayurveda:

It is being realized that identification of subgroups within normal controls corresponding to contrasting disease susceptibility is likely to lead to more effective predictive marker discovery. We have previously used the Ayurvedic concept of Prakriti, which relates to phenotypic differences in normal individuals, including response to external environment as well as susceptibility to diseases, to explore molecular differences between three contrasting Prakrititypes: Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. EGLN1 was one among 251 differentially expressed genes between the Prakriti types. In the present study, we report a link between high-altitude adaptation and common variations rs479200 (C/T) and rs480902 (T/C) in the EGLN1 gene. Furthermore, the TT genotype of rs479200, which was more frequent in Kaphatypes and correlated with higher expression of EGLN1, was associated with patients suffering from high-altitude pulmonary edema, whereas it was present at a significantly lower frequency in Pitta and nearly absent in natives of high altitude. Analysis of Human Genome Diversity Panel-Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (HGDP-CEPH) and Indian Genome Variation Consortium panels showed that disparate genetic lineages at high altitudes share the same ancestral allele (T) of rs480902 that is overrepresented in Pitta and positively correlated with altitude globally (P< 0.001), including in India. Thus, EGLN1polymorphisms are associated with high-altitude adaptation, and a genotype rare in highlanders but overrepresented in a subgroup of normal lowlanders discernable by Ayurveda may confer increased risk for high-altitude pulmonary edema.

The paper itself is a follow up to a previous work attempting to see if there was a sense to the classification of constitutions found within Ayurvedic medicine. Like Chinese medicine this is a non-Western tradition which has different philosophical roots and axioms (Galenic medicine might be analogous). But in theory all medical traditions emerged to battle illness, so their target was unitary, the ailments which plague the human body. Therefore one might suppose that in fact there would be some sense in any long-standing medical tradition which has any empirical grounding, because human biology is relatively invariant. It is the relative clause which is of interest for the purposes of this paper, because the authors show how the classifications of Ayurvedic medicine seem to comport with the recent genetic evidence of high altitude adaptation! Specifically they found that particular Ayurvedic classes of individuals who seem to have negative reactions to high altitude exposure in the form of hypoxia tend to be carriers of particular EGLN1 genotypes.

I will at this point observe that since I don’t know much about Ayurveda I won’t address or cover that issue in detail. The paper is Open Access so you can read it yourself. So let’s move to the genetics. EGLN1 should be familiar to you by now. It’s cropped up repeatedly over the past year in studies ofhigh altitude adaptation. It is a locus which seems to be a target of selection in both the peoples of the Andes and Tibet. Additionally, it has a peculiar aspect where the ancestral variant, the one found most frequently within Africa, seems to be the target of selection for altitude adaptation outside of Africa.

The slideshow below is an overview of the primary figures within this paper.

What do we take away from this? Well, one aspect which I think is important to emphasize is that genetic background matters, and there’s much we don’t know. In the conclusion the authors note that the altitude adaptation papers which I alluded to above were not published when the manuscript was being written, so they were not privy to the rather repeated robust evidence that EGLN1 has been the target of natural selection, and that variation on the locus is correlated with variation in adaptation to higher altitudes. The widespread coverage of populations in this paper seems to almost obscure as much as highlight. What has African variation to do with this after all? Additionally one must always remember that one given marker on a gene which shows a correlation does not entail functional causation. We saw this with the markers which seemed to predict the odds of an individual of European ancestry having blue eyes; it turned out that the markers themselves were simply strongly associated with another SNP which was probably the real functional root behind the difference in phenotype.

Due to the replication of EGLN1 in both Andeans and Tibetans I am moderately confident that variation on this gene does have something to due with high altitude adaptation. What I am curious about is the fact that the ancestral alleles in many cases seem to be driven up on frequency. Is there an interaction between the genetic background of non-Africans and the SNPs in question which make it beneficial toward altitude adaptation? Was there an initial relaxation of function as human populations moved out of Africa, which was slammed back on at high altitudes? There does seem a correlation within South Asian populations between hypoxia and high altitudes and particular variants on EGLN1. Focusing just on this region we can draw some reasonable inferences, but taking a bigger picture view and encompassing the whole world we’re confronted with a rather more confused, and perhaps more interesting, picture.

Back to the specific issue of the lack of South Asian imprint on the genes of Tibetan peoples, I think one can chalk this up to the fact that humans are animals, and so we’re constrained by geography and biology. Tibetans can operate efficiently at lower altitudes, and so have mixed with South Asians in these regions. In contrast, South Asians can not operate at higher altitudes, and so the impact on Tibetans was purely cultural, and not genetic. More broadly this may also point to long term geopolitical implications: the Han Chinese demographic domination of Tibet is always going to be a matter of water flowing uphill. Unless of course we flesh out the genetic architecture of these traits well enough that the Chinese government knows exactly which individuals among the 1.2 billion Han population would be most biologically prepared to reside in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, and so can proactively recruit them to settle in Lhasa and other strategic locations.

Citation: Shilpi Aggarwal, Sapna Negi, Pankaj Jha, Prashant K. Singh, Tsering Stobdan, M. A. Qadar Pasha, Saurabh Ghosh, Anurag Agrawal, Indian Genome Variation Consortium, Bhavana Prasher, & Mitali Mukerji (2010). EGLN1 involvement in high-altitude adaptation revealed through genetic analysis of extreme constitution types defined in Ayurveda PNAS :10.1073/pnas.1006108107

Who said the Meitei lon is Tibeto-Burman? Dr GRIERSON, but he was wrong

By Dr. Irengbam Mohendra Singh

March 22, 2011 03:56

By: Dr. Irengbam Mohendra Singh

![]() Who’s this Dr Grierson?

Who’s this Dr Grierson?

George Abraham Grierson, an Irish linguist from Dublin, was an official of the Indian Civil Service. He conducted between 1894 and 1928 for the British Raj, “The Linguistic Survey of India” (LSI). He described 364 languages and dialects. He included the “Meitheis” (ignorantly using the name of the people instead of the language), now “Meitei” as a Tibeto-Burman language.

Who’s this Dr Grierson?

Who’s this Dr Grierson?George Abraham Grierson, an Irish linguist from Dublin, was an official of the Indian Civil Service. He conducted between 1894 and 1928 for the British Raj, “The Linguistic Survey of India” (LSI). He described 364 languages and dialects. He included the “Meitheis” (ignorantly using the name of the people instead of the language), now “Meitei” as a Tibeto-Burman language.

In 1898 he was appointed Superintendent of the newly formed ‘Linguistic Survey of India’ and moved to England “for convenience of consulting libraries and scholars”. Before that he was an Opium Agent for Bihar. He wrote ‘Seven grammars of the dialects and sub-dialects of the Bihari language (1883-87), and Bihari Peasant Life (1885). He was not very popular there.

He did a remarkable job with the linguistic survey, considering what he did. Sitting in an office in Calcutta, between drinking pink gin at the Calcutta Club in Chowringhee at lunch time, and Jamieson Irish whisky before dinner, he used untrained field workers to collect information.

Grierson never came to Manipur or near abouts during those years. He collected information from Wahengbam Yumjao (no disrespect to him), an amateur archaeologist and member of the Manipur State Durbar, who advised Christopher Gimson about the Meitei script as well as many other aspects of Meitei lon for the Linguistic Survey of India.

Quoting Hodson (The Meiteis p12) – In discussing the origin of the Loi communities, he could not add very much to Dr Grierson’s remarks on the paucity of linguistic evidence: “None of these dialects has been returned for the survey, and they have probably all disappeared.”

Having discovered that Grierson’s LSI is untrustworthy, an India Government census in 1991

found 1,576 “mother tongues” with separate grammatical structure, and 1,796 languages classified as “other mother tongues”. It was realised that south India such as Madras, Hyderabad and Mysore as well as many princely states were neglected and thus under represented.

found 1,576 “mother tongues” with separate grammatical structure, and 1,796 languages classified as “other mother tongues”. It was realised that south India such as Madras, Hyderabad and Mysore as well as many princely states were neglected and thus under represented.

Grierson’s survey is now only useful as an aid-memoir. It is practically unreliable and conceptually clouded as data gathering was hampered by untrained field workers.

I had a gut-feeling that Meitei lon is not a Tibeto-Burman language as I had been sceptical that the Meitei migrated from China. I did my own research.

My critical intent is to counterpoise the over-determined received “academic” notion that the 2,000-year old Meitei lon is a Tibeto-Burman language and that the Meitei migrated to Manipur from somewhere in Southeast Asia, by presenting balanced multiple points of view, and by opposing obscurely described claims against modern established views.

The inclusion of Meitei lon in the Tibeto-Burman family, which incorporates a world view of population dispersal and language diffusion without any historical facts, based on the central theory of human migration/invasion models, kept alive erroneously by Dr Grierson and Dr Konov is dangerously undermining the real identity of Meitei lon.

This brings me to my hypothetical condition for the purpose of discussion that the Meitei language was a self-generated and self–organised in the long Meitei evolutionary process, once a communication was intended among the many clans who spoke different dialects. Eventually it evolved into a rule-governed system. The understanding is based on the ‘overview of the approach’ by Briscoe (2002) and Herford (1999). There is parallelism between the development of species and language (Sir C. Lyell, 1863).

During the late Last Ice Age about 25,000-20,000 years ago, a group separated from the main body of early humans in India, expanding to the east through the northeast corridor and settled in Manipur, as the Austroasiatic speaking Khasis did in Meghalaya. This was the time when the anatomical changes from the original dark African ancestors to the Mongolic phenotype occurred because of ‘drift’ or by Natural Selection, as adaptation to cold.

These Meitei ancestors were a small population and thus quite favourable to the force of drift. Manipur in the Pleistocene Age (extreme fluctuation of temperature) was a distant cold country and within the range of “Last Glaciations”.

According to Richard Dawkins, language seems to ‘evolve’ at a much faster rate than genetic evolution, and seem to evolve by non-genetic means.

This might have happened to Meitei lon that developed as a regional language under pressure for communication and it evolved much faster than the Tibeto-Burman language. Impetus for better communication led to the development of its own archaic indigenous alphabet – Meitei mayek, while the Tibetans borrowed Devnagri script and the Burmese acquired the Tamil alphabet. The Chinese used pictograms and they still use them.

Current research in genetics, archaeology and anthropology all over the world, has shown no invasion or migration of people from Southeast Asia to Manipur. There are no facts of invariable connection between Meitei lon and the Tibeto-Burman language family. There is no proto-Tibeto-Burman speaking homeland anywhere in Southeast and East Asia.

The old Meitei language of the Poireiton group such as Andro, Sekmai, and Chairel etc is a tonal language like the languages of the northeast India, but it has some similarities only with the Kachin language spoken in the Kachin state of Myanmar, and Bodo in Assam.

In Meitei lon, tone is phonemic with three tones. That is the meaning of the word changes in accordance with the tone viz., rising, falling and level. For example, masi yamna phate (this is very bad); masi yaaamna phate (this is awfully bad); and masi aduk yamna phataba nateda (this is not that bad).

Typologically, Meitei lon is an agglutinating language and there are some similarities in vocabulary at the morphological level with the Tibeto-Burman language. Languages do assimilate one from the other.

Meitei lon is not related to either in he roots of verbs or in the form of grammar to any Tibeto-Burman language. It has only language affinity ie similar in structure which may suggest a common origin. There are however various “doubtful cognates” ie possible chance similarities. There are also “False friends” (or faux amis). These are pairs of words in two languages or dialects (or letters in two alphabets) that look similar but differ in meaning.

There are vast theories of the myths of languages. The Tibeto-Burman origin of Meite lon is a myth. The Meitei language is unique, as are the Meitei people and Meitei alphabet.

Traditional techniques can be used to construct evolutionary trees of languages by comparing their vocabularies. The trouble is the speed at which word-use changes means that this approach is not much good at looking further back than 10,000 years. The etymology of the Meitei ancestors is 20,000 years old.

Still, ancient European anthropologists interpreted Meithei (Meitei lon) as a Tibeto-Burman language simply because the Meitei look Mongoloid.

There are now many studies that point out the derogatory nature of grouping all Mongoloid people of northeast India as Tibeto-Burman speakers as mere European ethnocentrism and supermacism.

Even now, many Indian researchers and the government of India recognise castes and tribals and usually state that “Most people from northeast India are classified as tribals and speak one of the Tibeto-Burman languages”. Quite a few research projects have been undertaken in India eg by Analabha Basu et al, among the tribals of northeast India, but the Meitei were never included, having been presumed to be just another similar tribe.

In modernity, the existence of an Indo-Aryan language is questionable as there is no archaeological evidence of a people known as Aryans invading India. Even the long-accepted genetic relationship of the hypothetical Sino-Tibetan family remains disputed but accepted without question by non-specialists, as in the case of Meitei lon.

Really, Meitei lon is an Indian language in Southeast Asia, surviving with a number of Tibeto-Burman languages like Naga languages in the northern region, Myanmarese in the east and Mizo in the southeastern region.

Without fluffing my lines because of lack of space I will let three super-specialists play their part.

Three of the world’s leading authorities on Tibeto-Burman language – James A Matisoff, Professor Emeritus, University of California (2003), George Van Driem, a Dutch linguist at Leiden University (2001) and David Bradley, Prof. at La Trobe University, Australia (1997) have independently re-classified Tibeto-Burman languages in which Meithei, now Meitei, is not included anymore. They have left Meitei lon as unclassified.

But as will been seen in Matisoff’s classification below, Kuki-Chin-Naga only are in the Tibeto-Burman family instead of Grierson’s ‘Northeast India’ that includes Meitei (Manipuri) and Austroasiatic speaking Khasis whose language later dispersed to Southeast Asia.

Matissof makes no claim that the families in the Kamarupan or Himalayish branches have a special relationship to one another than a geographical area, pending more detailed comparative work.

The individuality of Manipuri (Meitei lon) is now indisputable. It awaits classification in the modern language tree. The classification of languages is a matter of considerable disagreement, because the languages change so fast and are mutable. Many linguists are sceptical of attempts to find ancient relationship between living languages.

CLASSIFICATION

James Matisoff’s widely accepted classification is as follows:

James Matisoff’s widely accepted classification is as follows:

TIBETO-BURMAN

(a) Kamarupan

~ Kuki-Chin-Naga

~ Abor-Miri-Dafla

~ Bodo-Garo

~ Kuki-Chin-Naga

~ Abor-Miri-Dafla

~ Bodo-Garo

(b) Himalayish

~ Maha-Kiranti (includes Nepal Bhasa, Magar, Rai)

~ Maha-Kiranti (includes Nepal Bhasa, Magar, Rai)

(c) Qiangic

~ Jingpho-Nungish-Luish

~ Kachinic (jingpho)

~ Nungish

~ Luish

~ Jingpho-Nungish-Luish

~ Kachinic (jingpho)

~ Nungish

~ Luish

(d) Lolo-Burmese-Naxi

(e) Karanic

(f) Baic

(e) Karanic

(f) Baic

OLD GRIERSON’S CLASSIFICATION

Photo: Map of population dispersion & archaic European

Meiteilon is no more a skeleton in the cupboard.

The writer is based in the UK

Email: imsingh@onetel.com Website: drimsingh@onetel.co.uk

Email: imsingh@onetel.com Website: drimsingh@onetel.co.uk