- Sit Shamshi bronze, morning libations to Sun divinity, as Meluhha metalwork with Indus writing hieroglyphs transmitted along the Tin Road of Antiquity.

- The Sit Shamshi bronze model parallels the libations practised from ancient times by Hindus, Meluhha speakers who called themselves, bharatiyo'metal casters' (Gujarati). The prayers are called sandhya vandanam which is perhaps the oldest practice among world religions. [quote]Sandhyavandanam consists of excerpts from the Vedas that are to be performed thrice daily at morning (prātaḥsaṃdhyā), at noon (mādhyānika), and in the evening (sāyaṃsaṃdhyā)...Sandhyavandanam literally means salutation to Sandhya. Sandhya literally means transition moments of the day namely the twotwilights : dawn and dusk and the solar noon. Thus Sandhyavandanam means salutation to twilight or solar noon. The term saṃdhyā is also used by itself in the sense of "daily practice" to refer to the performance of these devotions at the opening and closing of the day. For saṃdhyā as juncture of the two divisions of the day (morning and evening) and also defined as "the religious acts performed by Brahmans and twice-born men at the above three divisions of the day" see Monier-Williams, p. 1145, middle column.[unquote]

- The Middle Elamite period usually stated as between 1500 to 1100 BCE, is characterized by 1. Untash-Napirisha who founded the site at Chog Zanbil, ancient Al Untash-Napirisha, with a stepped temple tower or ziggurat; 2. Shilhak-Inshushinak's campaigns in eastern and northeastern Mesopotamia. The kingdom of lowland Susa and highland Anshan has yielded archaeological artifacts from sites such as Tal-i Malyan, Kul-e Farah, Choga Zanbil, Haft Tepe and Susa. Sit Shamshi bronze model of sunrise libations, is one such artifact.

- Rimush was the younger son of Sargon of Agade.

- Rimush refers to diorite, dushu-stone received from Barahshum. Middle Elamite Susa yielded a large cast bronzework, Napir-Asu's statue which weights 1750 kg with a solid core of 11 per cent tin-bronze and an outer shell of copper cast in the lost-wax process with 1 per cent tin and various other impurities including lead, silver, nickel, bismuth and cobalt. At Susa 1.29m high cast bronze statue of Untash-Napirisha's wife, Napir-Asu was recovered from the temple to Ninhursag founded by Shulgi in the Acropole.

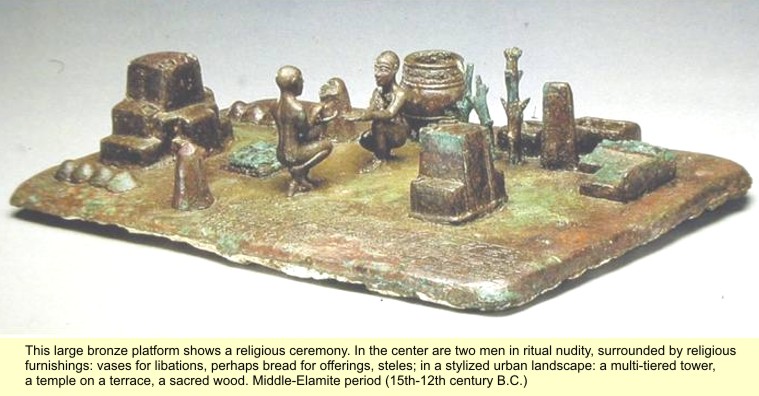

- In a Rimush royal inscription Gupin and Meuhha are mentioned after Zahara and Elam which details eastern regions.The cast bronze model of Sit Shamshi was made by Shilhak-Inshushinak, who after identifying himself giving his titles in a short inscription claims: 'I have made a bronze sunrise (sit shamshi)' (Konig 1965: 56). Potts describes the scene on the model: "Discovered in the area of the Ninhursag temple on the Acropole, the sit shamshi, as it has come to be known, is a unique representation of ritual in action. The model consists of a flat, 60X40 cm. base which supports pair of nude male figures, each of whom crouches. One holds a spouted vessel while the hands of the other's are extended flat, palms up. The figures are surrounded by various items, some of which were cast in one piece with the men and platform, while others were attached with rivets. Two stepped structures, vaguely reminiscent of the ziggurat at Choga Zanbil, flank the figures. Two rectangular basins, a large pithos, three trees, a stele-like object, an L-shaped platform, and two rows of four semi-spheres fill out the scene. The interpretation of sit shamshi is far from clear. It has been described as a model of 'a cult activity taking place at the break of day in which two persons, presumably priests, engage in ritual cleansing at the very spot where the day's sacrifices and libations will be carried out' (Harper, Aruz and Tallon 1992: 140). Alternatively, F. Malbran-Labat suggests that it may represent a funerary ceremony for kings interred nearby which was celebrated at dawn..." (Potts, DT, 1999, The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state, Cambridge University Press, p. 239 Kingdom of Susa and Anshan).

See: http://www.iranchamber.com/history/susa/susa.php Susa, capital of Elam By: Jona Lendering

- In a lecture given at the 5th European Conference on Iranian Studies, Societas Iranologica Europea, Ravenna, on 10th October 2003, Gian Pietro Basello of Uniersita degli Studi 'L'Orientale', Napoli, Italia delivered a scintillating lecture on "Loan-words in Achaemenid Elamite: the spellings of old Persian month-names."

- The text of the lecture is mirrored and embedded.

Annex provides an overview of Sit Shamshi bronze recorded in Louvre Museum catalog description.

- Veda pathashala students doing sandhya vandanam at Nachiyar Kovil, Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu

![]() Statue from early temple at Susa, Iran, ca. 2700 - 2340 BCE (Louvre). The animal he carries on his hands is a Meluhha rebus hieroglyph: kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Hence, a blacksmith.

Statue from early temple at Susa, Iran, ca. 2700 - 2340 BCE (Louvre). The animal he carries on his hands is a Meluhha rebus hieroglyph: kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Hence, a blacksmith.- Copper statue of God Nergal riding a chariot. Susa acropolis, 1600 BCE

![]() Pointing to this photograph of an object, Gian Pietro Basello quizzes: "Do you know this object? I hope so. It is perhaps the most stimulating object found in the entire Ancient Near East, even if handbooks on Mesopotamian art do not talk much about it. It is a three-dimensional bronze model whose base measures about 60X40 cm, excavated in the 1904-1905 campaign by the French mission at Susa. The scene is focused on two squatted human figures: one stretches its hands out, the other seems to be pouring water over them from a jug. Around them, there are possibly some kinds of altars, a large vessel, two basins, a stela and three trunks of trees. This act, perhaps a cultic scene which took place in the second half of the 12th century BCE, was fixed for eternity by will of Silhak-Insusinak (1140-1120 BCE), king of Ansan and Susa, according to the short inscription in a corner of the base."

Pointing to this photograph of an object, Gian Pietro Basello quizzes: "Do you know this object? I hope so. It is perhaps the most stimulating object found in the entire Ancient Near East, even if handbooks on Mesopotamian art do not talk much about it. It is a three-dimensional bronze model whose base measures about 60X40 cm, excavated in the 1904-1905 campaign by the French mission at Susa. The scene is focused on two squatted human figures: one stretches its hands out, the other seems to be pouring water over them from a jug. Around them, there are possibly some kinds of altars, a large vessel, two basins, a stela and three trunks of trees. This act, perhaps a cultic scene which took place in the second half of the 12th century BCE, was fixed for eternity by will of Silhak-Insusinak (1140-1120 BCE), king of Ansan and Susa, according to the short inscription in a corner of the base."

This introduction provides information on the provenience of the bronze model which has been called 'Sit Shamshi Bronze', now kept in the Louvre Museum. The words 'Sit Shamshi' appear in lines 5-6 of the inscription (which is in Elamite), but the words are Akkadian meaning, "rising of the sun, sunrise."

Rutten, M., 1953, Les documents epigraphiques de Tchogha Zembil, Memoires de la Delegation archeologique en Iran, 32, p. 21, Paris.

Grillot, Francoise, 1982, 'Notes a propos des formules votives elamites', Akkadika, 27, pp. 5-15.

So, Gian Pietro Basello exclaims: "So, an Akkadian name for an Elamite object in an Elamite inscription !" And, goes on to cite a note of M. Rutten which refers to the words Sit Shamshi as middle Elamite votive formula and hence, deduces that these are Akkadian loan-words in Elamite. Not only are they loan-words but the cuneiform script is Elamite-cuneiform borrowed into Akkadian-cuneiform.

It is clear that the bronze model itself relates to activities of a date much earlier than 12th century BCE because the inscription in Elamite including an Akkadian word, 'Shamshi' is an addition made by a ruler of Ansan and Susa in the 12th century BCE.

It is also clear from the Elamite inscription that the scene depicted on the bronze model is a water libation for the Sun divinity. The scene of action is in front of a model of a pyramid or ziggurat, which in the Sumerian context is revered as a temple.

Discovery location: Ninhursag or Nintud (Earth, Mountain and Mother Goddess)Temple, Acropole, Shūsh (Khuzestan, Iran); Repository: Musée du Louvre (Paris, France) ID: Sb 2743 width: 40 cm (15.75 inches); length: 60 cm (23.62 inches)

The stele (L) next to 3 stakes (or tree trunks, K) may denote a linga. Hieroglyph: numeral 3: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy' PLUS meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Thus, together, the three stakes or stalks + linga connote rebus representations of 'iron smithy' meḍ kolami. Another rebus reading may connote: mḗdha m. ʻ sacrificial oblation ʼ RV.Pa. mēdha -- m. ʻ sacrifice ʼ; Si. mehe, mē sb. ʻ eating ʼ mḗdhya -- ʻ full of vigour ʼ AV., ʻ fit for sacrifice ʼ Br. [mḗdha -- m. or mēdhāˊ -- f. ʻ mental vigour ʼ RV.] Pa. mejjha -- ʻ pure ʼ, Pk. mejjha -- , mijjha -- ; A. mezi ʻ a stack of straw for ceremonial burning ʼ.(CDIAL 10327). The semant. of 'pure' may also evoke the later-day reference to gangga sudhi'purification of river water' in an inscription on Candi Sukuh 1.82m tall linga ligatured with a kris sword blade, flanked by sun and moon and a Javanese inscription referring to consecration and manliness as the metaphor for cosmic essence. The semant. link with Ahura Mazda is also instructive, denoting the evolution of the gestalt relating knowledge, consciousness and cosmic effulgence/energy. That the metaphor related to metalwork is valid is indicated by a Meluhha gloss: kole.l'smithy' Rebus: kole.l 'temple.

A large stepped structure/altar/ziggurat (A) and small stepped structure/altar or temple (B) may be denoted by the gloss: kole.l. The large stepped structure (A) may be dagoba, lit. dhatu garbha'womb of minerals' evoking the smelter which transmutes earth and stones into metal and yields alloyed metal castings with working in fire-altars of smithy/forge: kolami. It is imperative that the stupa in Mohenjo-daro should be re-investigated to determine the possibility of it being a ziggurat of the bronze age, comparable to the stepped ziggurat of Chogha Zambil (and NOT a later-day Bauddham caitya as surmised by the excavator, John Marshall).

Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë

blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge.(DEDR 2133).

The pair of lingas (D and D') have indentations at the tip of the stone pillars. These indentations might have held lighted earthen lamps (deepam) to connote the lingas as pillars of light. The four hemi-spheres (C and C') linked to each stone pillar (D and D') have been explained as Meluhha hieroglyphs read rebus:

lo 'penis' Rebus: loh 'copper, metal'

Hieroglyphs: gaṇḍa 'swelling' gaṇḍa 'four' gaṇḍa 'sword' Hieroglyph: Ta. kaṇṭu ball of thread. ? To. koḍy string of cane. Ka. kaṇḍu, kaṇḍike, kaṇṭike ball of thread. Te. kaṇḍe, kaṇḍiya ball or roll of thread. (DEDR 1177)

Rebus: kanda 'fire-trench' used by metalcasters

Rebus: gaṇḍu 'manliness' (Kannada); 'bravery, strength' (Telugu)

Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’ (Marathi)

Together, hieroglyphs: lo + gaṇḍa. Rebus: लोखंड [ lōkhaṇḍa ] 'metalwork'

Metaphor: Sh. K.ḍoḍ. lō m. ʻ light, dawn ʼ; L. awāṇ. lō ʻ light ʼ; P. lo f. ʻ light, dawn, power of seeing, consideration ʼ; WPah. bhal. lo f. ʻ light (e.g. of moon) ʼ.(CDIAL 11120). + kaṇṭa 'manliness'.

Tabulation explaining the model & transcribed Elamite cuneiform inscription sourced from: Gian Pietro Basello, 2011, The 3D model from Susa called Sit-shamshi: an essay of interpretation, Rome, 2011 November 28-30 https://www.academia.edu/1706512/The_3D_Model_from_Susa_called_Sit-shamshi_An_essay_of_interpretation

Inscription of king Shilhak-Inshushinak I (1140-1120 BCE) on the three-dimensional model found in 1904-1905 campaign on the Acropois of Susa.

Gautier, Joseph-Etienne, 1911, Le Sit Shamshi de Shilhak in Shushinak, in Recherches archeologiques (Memoires de la Delegation en Perse, 12), pp. 143-151, Paris [description of the model with plan]

Konig, Friedrich Wilhelm, 1965, Die elamischen Konigsinschriften (Archiv fur Orientforschung, Beiheft 16), p. 136, no. 56, Berlin/Graz (text of the inscription)

FW Konig, Corpus Inscriptionum Elamicarum, no. 56, Hannover 1926.

Tallon, Francoise, 1992, 'Model, called the sit-shamshi (sunrise)' [no. 87 of the exhibition catalogue] and Francoise Tallon and Loic Hurtel, 'Technical Analysis', in Prudence O. Harper, Joan Aruz & Francoise Tallon, eds., The Royal City of Susa. Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre, pp. 137-141, New York, Abrams.

- See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/01/significance-of-linga-and-4-spheres-on.html

Significance of linga and 4 spheres on Sit Shamshi bronze and Meluhha hieroglyphs on Candi Sukuh linga

There is a possibility that there was a Meluhha settlement of traders in Susa who could read the messages conveyed by Indus script inscriptions.The ziggurat shown on the Sit-Shamshi bronze compares with a ziggurat which might have existed in the Stupa mound of Mohenjodaro (lit. mound of the dead), indicating the veneration of ancestors in Susa and Meluhha in contemporaneous times.Some glyphics of the bronze model have parallels in Indian hieroglyphs. Glyph: 'stump of tree': M. khũṭ m. ʻstump of tree’; P. khuṇḍ, °ḍā m. ʻpeg, stumpʼ; G. khū̃ṭ f. ʻlandmarkʼ, khũṭɔ m., °ṭī f. ʻ peg ʼ, °ṭũ n. ʻstumpʼ (CDIAL 3893). Allograph: (Kathiawar) khũṭ m. ʻBrahmani bullʼ(G.) Rebus: khũṭ 'community, guild' (Munda)

The ceremony involved lo ‘pouring (water) oblation’ (Munda) for the setting sun. Rebus: loa ‘copper’ (Santali) The glyphic representations connote a guild of coppersmiths in front of a ziggurat, temple and is a veneration of ancestors. The authors of the bronze model seem to have interacted with the groups of artisans of Mohenjo-daro who had a ziggurat in front of the ‘great bath’.The eight knobs lining either side of the ziggurat may denote: <tamja-n+m>(L) {N} ``eight years''. #48162. <tamji>(L) {N} ``^eight''. *^V008 Kh.<tham>. #64641.Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper'. If this surmise is valid, the ziggurat might have been stupa called dhatu-garbha or dagoba or dagaba.

Glyph: मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Vikalpa: khuṇṭ ‘stump’. Rebus: khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Mu.) Thus, three jagged sticks on the Sit Shamshi bronze may be decoded as khũṭ kolami ‘smithy guild’ or, meḍ kolami 'iron (metal) smithy'. 'Iron' in such lexical entries may refer to 'metal'.After Fig. 200 in Gautier 1911:145 + FW Konig, Corpus Inscriptionum Elamicarum, no. 56, Hanover 1926 + Tallon & Hurtel 1992: 140, fig. 43. The base measures 60 X 40 cm. Sit Shamshi ‘sunrise ceremony’. Discovery location: Ninhursag Temple, Acropole, Shūsh (Khuzestan, Iran); Repository: Musée du Louvre (Paris, France) ID: Sb 2743 width: 40 cm (15.75 inches); length: 60 cm (23.62 inches)-

- Susa: sacred fire-smithy

Model of a temple, called the Sit-shamshi, made for the ceremony of the rising sun. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/sit-shamshi See the reading of the inscription at http://www.elamit.net/elam/sit_handout.pdf

Akkadian name for an Elamite object in an Elamite inscription!

Sit Shamshi an Akkadian loan-word in Elamite?

"Do you know this object? I hope so. It is perhaps the most stimulating object found in the entire Ancient Near East, even if handbooks on Mesopotamian art do not talk much about it. It is a three-dimensional bronze model whose base measures 60 X 40 cm, excavated in the 1904-05 campaign by the French Mission at Susa. The scene is focused on two squatted human figures: one stretches its hands out, the other seems to be pouring water over them from a jug. Around them, there are possibly some kinds of altars, a large vessel, two basins, a stela and three trunks of trees. This act, perhaps a cultic scene which took place in the second half of the 12th century BCE, was fixed for eternity by will of Shilhak-Inshushinak (1140-1120 BCE), king of Anshan and Susa, according to the short inscription in a corner of the base. If you are so lucky as to run into a picture of it (unless you are directly visiting the Louvre Museum), looking at the caption you would learn that the name commonly given to this object is sit shamshi. Actually , this name, meaning 'the rising of the sun, sunrise' in Akkadian, appears in lines 5-6 of the inscription. But only in the unlikely event that you are both in front of the Louvre showcase with the sit shamshi in and an 'Elamist', i.e. a specialist in Elamite studies, you could go further in reading the inscription, though even an Elamist, having been ready to interpret the most stereotyped Akkadian inscription -- you know, Akkadian was very spread in Susiana --, so even an Elamist will jolt becoming aware of the language of the text. Apart from brushing up the revered edition by Scheil (1909) or Konig (1965), this is the only way to learn that the inscription is compiled in Elamite language. So, an Akkadian name for an Elamite object in an Elamite inscription!" (Gian Pietro Basello, 2003, Loan-words in Achaemenid Elamite: the spelling of old Persian Month-names, in: 5th European Conf. of Iranian Studies, October 10th 2003 http://digilander.libero.it/elam2/elam/basello_sie2003.pdf )

"Sit shamshi is the name used in an inscription of the Middle Elamite king Shilhak-Inshushinak (ca. 1150-1120 BC) to refer to its textual support, a bronze model (base 60 × 40 cm) representing in three dimensions two squatted individuals, one pouring a liquid over the hands of the other, in an open space with buildings, trees and other installations. The common interpretation of this name (meaning ‘sunrise’ in Akkadian) has become also the key for the understanding of the whole scene, supposedly a ritual ceremony to be performed at the sunrise in a sacred precint.

From one hand, I would like to discuss the interpretation of sit shamshi as an Akkadian syntagm, considering that the inscription is written in Elamite and that sit e sham- are also known as Elamite terms. On the other hand, I would like to have feedback from scholars skilled in ritual texts from Mesopotamia, trying also to understand if there is some further element in support of the sunrise ritual interpretation.

12th century BC Tell of the Acropolis, Susa J. de Morgan excavations, 1904-05 Sb 2743 Louvre.

This large piece of bronze shows a religious ceremony. In the center are two men in ritual nudity surrounded by religious furnishings - vases for libations, perhaps bread for offerings, steles - in a stylized urban landscape: a multi-tiered tower, a temple on a terrace, a sacred wood. In the Middle-Elamite period (15th-12th century BC), Elamite craftsmen acquired new metallurgical techniques for the execution of large monuments, statues and reliefs.

A ceremony

Two nude figures squat on the bronze slab, one knee bent to the ground. One of the figures holds out open hands to his companion who prepares to pour the contents of a lipped vase onto them. The scene takes place in a stylized urban landscape, with reduced-scale architectural features: a tiered tower or ziggurat flanked with pillars, a temple on a high terrace. There is also a large jar resembling the ceramic pithoi decorated with rope motifs that were used to store water and liquid foodstuffs. An arched stele stands by some rectangular basins. Rows of dots in relief may represent solid foodstuffs on altars, and jagged sticks represent trees. The men's bodies are delicately modeled, their faces clean-shaven, and their shaved heads speckled with the shadow of the hair. Their facial expression is serene, their eyes open, the hint of a smile on their lips. An inscription tells us the name of the piece's royal dedicator and its meaning in part: "I Shilhak-Inshushinak, son of Shutruk-Nahhunte, beloved servant of Inshushinak, king of Anshan and Susa [...], I made a bronze sunrise."

Chogha Zambil: a religious capital

The context of this work found on the Susa acropolis is unclear. It may have been reused in the masonry of a tomb, or associated with a funerary sanctuary. It appears to be related to Elamite practices that were brought to light by excavations at Chogha Zambil. This site houses the remains of a secondary capital founded by the Untash-Napirisha dynasty in the 14th century BC, some ten kilometers east of Susa (toward the rising sun). The sacred complex, including a ziggurat and temples enclosed within a precinct, featured elements on the esplanade, rows of pillars and altars. A "funerary palace," with vaulted tombs, has also been found there.

The royal art of the Middle-Elamite period

Shilhak-Inshushinak was one of the most brilliant sovereigns of the dynasty founded by Shutruk-Nahhunte in the early 12th century BC. Numerous foundation bricks attest to his policy of construction. He built many monuments in honor of the great god of Susa, Inshushinak. The artists of Susa in the Middle-Elamite period were particularly skilled in making large bronze pieces. Other than the Sit Shamshi, which illustrates the complex technique of casting separate elements joined together with rivets, the excavations at Susa have produced one of the largest bronze statues of Antiquity: dating from the 14th century BC, the effigy of "Napirasu, wife of Untash-Napirisha," the head of which is missing, is 1.29 m high and weighs 1,750 kg. It was made using the solid-core casting method. Other bronze monuments underscore the mastery of the Susa metallurgists: for example, an altar table surrounded by snakes borne by divinities holding vases with gushing waters, and a relief depicting a procession of warriors set above a anel decorated with engravings of birds pecking under trees. These works, today mutilated, are technical feats. They prove, in their use of large quantities of metal, that the Susians had access to the principal copper mines situated in Oman and eastern Anatolia. This shows that Susa was located at the heart of a network of circulating goods and long-distance exchange. Authors: Caubet Annie, Prévotat Arnaud

Sit Shamshi

Model of a place of worship, known as the Sit Shamshi, or "Sunrise (ceremony)" Middle-Elamite period, toward the 12th century BC Acropolis mound, Susa, Iran; Bronze; H. 60 cm; W. 40 cm Excavations led by Jacques de Morgan, 1904-5; Sb 2743; Near Eastern Antiquities, Musée du Louvre/C. Larrieu. Two nude figures squat on the bronze slab, one knee bent to the ground. One of the figures holds out open hands to his companion who prepares to pour the contents of a lipped vase onto them.The scene takes place in a stylized urban landscape, with reduced-scale architectural features: a tiered tower or ziggurat flanked with pillars, a temple on a high terrace. There is also a large jar resembling the ceramic pithoi decorated with rope motifs that were used to store water and liquid foodstuffs. An arched stele stands by some rectangular basins. Rows of 8 dots in relief flank the ziggurat; jagged sticks represent trees.An inscription tells us the name of the piece's royal dedicator and its meaning in part: "I Shilhak-Inshushinak, son of Shutruk-Nahhunte, beloved servant of Inshushinak, king of Anshan and Susa [...], I made a bronze sunrise." (http://www.louvre.fr/en/recherche-globale?f_search_cles=sit+shamshi )

Three jagged sticks on the Sit Shamshi bronze, in front of the water tank (Great Bath replica?) If the sticks are orthographic representations of 'forked sticks' and if the underlying language is Meluhha (mleccha), the borrowed or substratum lexemes which may provide a rebus reading are:

kolmo 'three'; rebus; kolami 'smithy' (Telugu)

kolmo 'three'; rebus; kolami 'smithy' (Telugu)

Glyph: मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Vikalpa: P. khuṇḍ, °ḍā m. ʻ peg, stump ʼ; khuṇṭ ‘stump’. Rebus: 1. khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Mu.) 2. Skt. kuṇḍa- round hole in ground (for water or sacred fire).

Thus, three jagged sticks on the Sit Shamshi bronze may be decoded as khũṭ kolami ‘smithy guild’ or, kuṇḍa kollami ‘sacred fire smithy’ or, meḍ kolami 'iron (metal) smithy'. 'Iron' in such lexical entries may refer to 'metal'.

Sit Shamshi bronze illustrates the complex technique of casting separate elements joined together with rivets, the excavations at Susa have produced one of the largest bronze statues of Antiquity: dating from the 14th century BC, the effigy of "Napirasu, wife of Untash-Napirisha," the head of which is missing, is 1.29 m high and weighs 1,750 kg. It was made using the solid-core casting method.

S. kuṇḍa f. ʻcornerʼ; P. kū̃ṭ f. ʻcorner, sideʼ (← H.). (CDIAL 3898) Rebus 1: kundār turner (A.) kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295). Rebus 2: khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Mundari)

Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali) bharaḍo = cross-beam in the roof of a house (G.lex.) bhāraṭiyum, bhārvaṭiyo, bhāroṭiyo = a beam (G.lex.) bāri = bamboo splits fastened lengthwise to the rafters of a roof from both sides (Tu.lex.) bārapaṭṭe = chief beam lying on pillars (Te.lex.) bharaṇum a piece in architecture; placed at the top of a pillar to support a beam (G.) Rebus: bharatiyo = a caster of metals; a brazier; bharatar, bharatal, bharataḷ = moulded; an article made in a mould; bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (G.lex.) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhartīyā = a barzier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Skt.) Thus, the glyph ‘roof + cross-beam’ may read: bharaḍo šen; rebus: bharatiyo seṇi ‘guild of casters of metal’.

Annex

Annex

Sit Shamshi. Model of a place of worship, known as the Sit Shamshi, or "Sunrise (ceremony)" Middle-Elamite period, toward the 12th century BC Acropolis mound, Susa, Iran; Bronze; H. 60 cm; W. 40 cm Excavations led by Jacques de Morgan, 1904-5; Sb 2743; Near Eastern Antiquities, Musée du Louvre/C. Larrieu. Two nude figures squat on the bronze slab, one knee bent to the ground. One of the figures holds out open hands to his companion who prepares to pour the contents of a lipped vase onto them.The scene takes place in a stylized urban landscape, with reduced-scale architectural features: a tiered tower or ziggurat flanked with pillars, a temple on a high terrace. There is also a large jar resembling the ceramic pithoi decorated with rope motifs that were used to store water and liquid foodstuffs. An arched stele stands by some rectangular basins. Rows of 8 dots in relief flank the ziggurat; jagged sticks represent trees.An inscription tells us the name of the piece's royal dedicator and its meaning in part: "I Shilhak-Inshushinak, son of Shutruk-Nahhunte, beloved servant of Inshushinak, king of Anshan and Susa [...], I made a bronze sunrise."

This table, edged with serpents and resting on deities carrying vessels spouting streams of water, was doubtless originally a sacrificial altar. The holes meant the blood would drain away as water flowed from the vessels. Water was an important theme in Mesopotamian mythology, represented particularly by the god Enki and his acolytes. This table also displays the remarkable skills of Elamite metalworkers.

A sacrificial table

The table, edged with two serpents, rested on three sides on five figures that were probably female deities. Only the busts and arms of the figures survive. The fourth side of the table had an extension, which must have been used to slot the table into a wall. The five busts are realistic in style. Each of the deities was holding an object, since lost, which was probably a water vessel, cast separately and attached by a tenon joint. Water played a major role in such ceremonies and probably gushed forth from the vessels. Along the sides of the table are sloping surfaces leading down to holes, allowing liquid to drain away. This suggests that the table was used for ritual sacrifices to appease a god. It was believed that men were created by the gods and were responsible for keeping their temples stocked and providing them with food. The sinuous lines of the two serpents along the edge of the table mark off holes where the blood of the animals, sacrificed to assuage the hunger of the gods, would have drained away.

The importance of water in Mesopotamian mythology

In Mesopotamia, spirits bearing vessels spouting streams of water were the acolytes of Enki/Ea, the god of the Abyss and of fresh water. The fact that they figure in this work reflects the extent of the influence of Mesopotamian mythology in Susa. Here, they are associated with another Chtonian symbol, the snake, often found in Iranian iconography. The sinuous lines of the serpents resemble the winding course of a stream. It is thought that temples imitated the way streams well up from underground springs by the clever use of underground channels. Water - the precious liquid - was at the heart of Mesopotamian religious practice, being poured out in libations or used in purification rites.

Objects made for a new religious capital

Under Untash-Napirisha, the founder of the Igihalkid Dynasty, the Elamite kingdom flourished. He founded a new religious capital, Al-Untash - modern-day Chogha Zambil - some 40 kilometers southeast of Susa. However, the project was short-lived. His successors soon brought large numbers of religious objects back to Susa, the former capital. This table was certainly among them. Its large size and clever drainage system reflect the remarkable achievements of metalworking at the time.

Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, Suse 6000 ans d'histoire, Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1988, pp.98-99 ; fig. 57.

Miroschedji Pierre de, "Le dieu élamite au serpent", in : Iranica antiqua, vol.16, 1981, Gand, Ministère de l'Éducation et de la Culture, 1989, pp.16-17, pl. 10, fig.3.Author: Herbin Nancie

Basello, Gian Pietro, 2003, Loan-words in Achaemenid Elamite: the spellings of old Persian month-names