Celtic-Meluhha contacts during early Bronze Age: some hypotheses

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/10032403/Celtic-Meluhha_contacts_during_early_Bronze_Age_some_hypotheses

The geographic spread of ancient Celts, Hallstatt and La Tène cultures and iron age links with Britain and Ireland are unresolved controversies. (See bibliographical links at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celts).

Adding to these controversies, some hypotheses are presented:

1. Lia Fáil granite stone pillar in the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland is a Meluhhan artifact signifying copper, tamba.

2. The circular platform surrounding Lia Fáil is a Meluhhan artisan working platform and finds parallels in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization, in Harappa in particular.

3. The stone pillars of Lia Fáil and Dholavira are comparable and denote early gestalt of Meluhhans for denoting a stambha (rebus: tamba, 'copper') as a fiery pillar, a hieroglyphic metaphor for Rudra-Shiva inferred from a Skambha Sukta in Atharvaveda.

4. The Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs find echoes in hieroglyhs deployed by metalworkers on the Gundestrup silver gilded Cauldron traceable to Proto-Celtic, Hallstat and La Tene cultural traditions positing Meluhha-Celtic cultural interactions.

5. Meluhha links to the treasures of Tuatha Dé Danann of Celtic-Irish tradition are relatable to Bronze Age metalwork of Meluhha artisans and traders evidenced by the Indus script hieroglyphs and artifacts of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization.

These hypotheses are premised on the decipherment of Indus writing as Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs read rebus in Meluhha which constituted the lingua franca of the civilization in the Sarasvati-Sindhu doab with evidenced contact areas stretching along the Tin Road from Meluhha (Sarasvati-Sindhu doab) upto Haifa, Israel.

A preliminary account of the evidence is compiled in the following sections to further test these hypotheses.

Collar of stones around Lia Fáil in County Meath, Ireland, on the Hill of Tara, 25 miles north of Dublin

I love this collar of stones around the Stone of Destiny! Simply because, the platform of bricks laid out in a circular formation around the stone pillar is an exact replica of the Circular Workers' Platforms in Harappa !!

This ain't no flash in the pan. It ain't

something which disappoints by failing to deliver anything of value, despite a showy beginning.The comparable circular workers' platforms of Meluhhans in Harappa are further corroborated by narratives related to ancient Celts and Irish with overtones of metalwork, implicit in the four treasures of Tuatha De danann referring to a cauldron, spear, sword and of course, the stone of Fal as the center-piece of the circular brick platform, a legacy of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization. Four treasures of Tuatha De danann are:

Some narratives related to ancient Celts and Irish

Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland) is a collection of poems and prose narratives that purports to be a history of Ireland and the Irish from the creation of the world to the Middle Ages. This is comparable to the Old Testament as a narrative of Israelites' history or Mahabharata as a narrative of Bharatam janam (history of metalcasters) in the transition from cypro-lithic to bronze age phase of civilization).

"The first recension of Lebor Gabála describes the Tuatha Dé Danann as having resided in "the northern islands of the world", where they were instructed in the magic arts, before finally moving in dark clouds to Connaught in Ireland. It mentions only the Lia Fáil as having been imported from across the sea."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Treasures_of_the_Tuatha_De_Danann

I suggest that the polished granite pillar stone -- Lia Fáil --was brought by descendants of artisans of Meluhha.

One speculation is that Tuatha De Danann brought the techniques of making bronze to Ireland. The supernaturally gifted people were venerated and remembered as divinities in Ireland, children of Danu, the river divinity associated with the names of rivers -- Danube, Don, Dneiper, Dniestr. Dagda, son of Danu, is cognate with dagdha 'अग्निदग्ध 'burnt with fire'. This gloss means: (pl.) a class of Manes or Pitṛis who, when alive, kept up the household flame and presented oblations to fire.

"The Vedic tradition also has a goddess Danu, the daughter of Daksha, wife of kasyapa Muni, who was a goddess of the rivers. The word Danu in Samskritam means 'flowing water'. As a daughter of Daksha, her sister Sati would have been married to Lord Shiva. To practitioners of Vedic tradition the Lia Fáil matches very closely to the Shiva Linga."http://www.indiadivine.org/news/history-and-culture/ancient-shiva-linga-in-ireland-r831

From the following excerpt from an archaeological account, I guess that the circular platform surrounding the Lia Fáil, or Stone of Destiny was an exact replica of the structure as it existed in the Mound of the Hostages, before the granite pillar was relocated at the centre of the Forraid, as shown in the picture above:

"The oldest visible building at Tara is a small chambered cairn on the summit of the hill which is known as the Mound of the Hostages. The name probably comes from some of the many mythological stories associated with the monument. The mound is a chambered cairn or passage grave and was built around 3000 BCE...The mound was excavated by S. P. O'Riordan between 1955 and 1959; what you see today is the reconstruction after excavation. O'Riordan found evidence of an earlier structure under the mound...The mound produced the largest collection of burials and associated artifacts from any Irish neolithic site. These finds included a 30 cm thick layer of cremated bones and a whole range of pendants, antler pins, pottery shards, stone balls and a minature Carrowkeel ware pot. Use for burial continued throughout the Bronze age, when nearly 40 cremated burials were placed in the clay mantle of the mound. There was one inhumation, the body of a 14 year old boy, which was placed under a burial urn. Finds with this burial included fiaence beads which came from the eastern Mediterranean...The Lia Fáil, or Stone of Destiny, which now stands at the centre of a fort called the Forrad, originaly stood outside the entrance to the Mound of the Hostages. It was moved to its present location at the centre of the Forraid in 1824 to commemorate the 1798 Battle of Tara. The stone is a granite pillar, 1.5 meters tall, and is said to be one of the four treasures brought to Ireland by the Tuatha De Danann. ![]()

Tara from the air taken from an old postcard. The view is looking north. The Forrad and Teach Cormac are the double ringforts at the centre, and the Lia Fáil stands in the Forrad, the left-most monument...It is said that there were four standing stones at Tara: the Lia Fail, Bolcc and Bluigne, which are located in the graveyard, and a stone known as Moel which has dissappeared. They are said to have been placed on the cardinal directions around Tara...Rath na Rig, the Fort of the Kings is a huge oval enclosure running around the top of the hill; it measures 320 x 260 meters and has a circumfrance of 1 km...The name, Rath na Rig is medieval, and indicates that the royal residence was in the inner monuments, the Forrad and Teach Cormac. The Forrad and Teach Cormac are a pair of cojoined ringforts at the centre of Rath na Rig."

The Rath of the Synods, onr of only three sites in Ireland with four encircling banks. This site was damaged by the British Israelites during their search for the Ark of the Covenant. Beyond is the Mound of the Hostages.

It is unclear if the four encircling banks around the Mound of the Hostages is a pre-existing layout of the site. If so, the encircling banks may compare with the fortifications -- so-called 'citadels' - reported from many archaeological sites of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization such as Surkotada, Chanhu-daro, Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Kalibangan.

Two architectural features related to Lia Fáil compare with the following artifacts of Dholavira and Harappa (pictures appended):

1. The double ringforts of Forrad and Teach compare with the 8-shaped stone structures found in Dholavira in front of two polished pillar stones.

2. The circular platform surrounding the granite pillar evokes the workers' platforms found in Harappa of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

3. Shivalinga stones have been found in Harappa. Polished pillar stones have been found in Dholavira.

8-shaped structural remains at Dholavira.

Close-by th 8-shaped strucure are two polished pillars, stambhas at Dholavira.

Close-by th 8-shaped strucure are two polished pillars, stambhas at Dholavira.Dholavira (Kotda).The two 'sthambs', or polished pillars, which are claimed to resemble Sivalingas, in the citadel.

Two linga skambhas of Dholavira (ca. 2500 BCE); skambha as fulcrum of all existence: Atharva Veda

Dholavira. Stone pillars, ring-stones.

Dholavira. Stone pillars, ring-stones.Evidence for Sivalinga is provided in other sites (Mohenjodaro and Harappa) of the civilization:

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.Lingam, grey sandstone in situ, Harappa, Trench Ai, Mound F, Pl. X (c) (After Vats). "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I... in this jar, six lingams were found along with some tiny pieces of shell, a unicorn seal, an oblong grey sandstone block with polished surface, five stone pestles, a stone palette, and a block of chalcedony..." (Vats,MS, Excavations at Harappa, p. 370)

These pillars evoke the imageries of a festival which is celebrated even today by Lingavantas, particularly in Karnataka.

These pillars at Dholavira could be a depiction of pillars of flame as Sivalinga.

This remarkable discovery of a set of shivalingas in Bhaitbari-Tikrikilla area in Meghalaya's West Garo Hills district of Assam point to the possibility that the circular platforms found in large numbers in Harappa could have held such shivalingas at the centre of the platforms. What could the polished stone pillars have signified, assuming that the circular platforms were workers' artisans' platforms of metal and stone artifacts produced by them?

One hypothesis is that the stone pillar, shivalinga denoted Stambha as described metaphorically in Atharvaveda. The Meluhha gloss is tamba.Read rebus: it denotes tamba, tamb(r)a'copper'.

Hieroglyph: 'pillar post' thambā ʻ

stambha m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ Kāṭh., °aka -- m. Mahāvy. [√stambh ] Pa. thambha -- m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Aś.rum. thabhe loc., top. thaṁbhe, ru. ṭha(ṁ)bhasi, Pk. thaṁbha -- , °aya -- , taṁbha -- , ṭhaṁbha -- m.; Wg. štɔ̈̄ma ʻ stem, tree ʼ, Kt. štom, Pr. üštyobu; Bshk. "ṭam"ʻ tree ʼ NTS xviii 124, Tor. thām; K. tham m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ, S. thambhu m.; L. thamm, thammā m. ʻ prop ʼ, (Ju.) tham, °mā, awāṇ. tham, khet. thambā; P. thamb(h),thamm(h) ʻ pillar, post ʼ, Ku. N. B. thām, Or. thamba; Bi. mar -- thamh ʻ upright post of oil -- mill ʼ; H. thã̄bh, thām, thambā ʻ prop, pillar, stem of plantain tree ʼ; OMarw. thāma m. ʻ pillar ʼ, Si. ṭäm̆ba; Md. tambu, tabu ʻ pillar, post ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : S. thambhiṛī f. ʻ inside peg of yoke ʼ; N. thāṅro ʻ prop ʼ; Aw.lakh. thãbharā ʻ post ʼ; H. thamṛā ʻ thick, corpulent ʼ; -- -- ll -- ; G. thã̄bhlɔ, thã̄blɔ m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ. -- X sthūˊṇā -- q.v. S.kcch. thambhlo m. ʻ pillar ʼ, A. thām, Md. tan̆bu. (CDIAL 13682)

Rebus: tāmbā 'copper'

Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. l ām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.) tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth.cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō, Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or. tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m., G. trã̄bũ, tã̄bũ n.;M. tã̄bẽ n. ʻ copper ʼ, tã̄b f. ʻ rust, redness of sky ʼ; Ko. tāmbe n. ʻ copper ʼ; Si. tam̆ba adj. ʻ reddish ʼ, sb. ʻ copper ʼ, (SigGr) tam, tama. -- Ext. -- ira -- : Pk. taṁbira-- ʻ coppercoloured, red ʼ, L. tāmrā ʻ copper -- coloured (of pigeons) ʼ; -- with -- ḍa -- : S. ṭrāmiṛo m. ʻ a kind of cooking pot ʼ, ṭrāmiṛī ʻ sunburnt, red with anger ʼ, f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; Bhoj. tāmrā ʻ copper vessel ʼ; H. tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā ʻ coppercoloured, dark red ʼ, m. ʻ stone resembling a ruby ʼ; G. tã̄baṛ n., trã̄bṛī, tã̄bṛī f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; OM. tāṁbaḍā ʻ red ʼS.kcch. trāmo, tām(b)o m. ʻ copper ʼ, trāmbhyo m. ʻ an old copper coin ʼ; WPah.kc. cambo m. ʻ copper ʼ, J. cāmbā m., kṭg. (kc.) tambɔ m. (← P. or H. Him.I 89), Garh. tāmu, tã̄bu. (CDIAL 5779). Pk. taṁbiya -- n. ʻ an article of an ascetic's equipment (a copper vessel?) ʼ; L. trāmī f. ʻ large open vessel for kneading bread ʼ, poṭh. trāmbī f. ʻ brass plate for kneading on ʼ; Ku.gng.tāmi ʻ copper plate ʼ; A. tāmi ʻ copper vessel used in worship ʼ; B. tāmī, tamiyā ʻ large brass vessel for cooking pulses at marriages and other ceremonies ʼ; H. tambiyā m. ʻ copper or brass vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 5792).

Harappa: reconstructed platform close-up (white colouring is caused by salt seepage)

Harappa: reconstructed platform close-up (white colouring is caused by salt seepage)

Harappa platforms.

Harappa platforms.Slide 336 harappa.com Overview of Trench 43 in 2000 looking north, showing the HARP-exposed circular platform in the foreground and the "granary" area in the background. Note the wall voids to the west, south, and east of the circular platform (see also image 356).Slide 356.Detail view of the HARP-excavated platform in Trench 43 with Wheeler's platform to the east (toward the top of the image). Note the mud-brick wall foundations that surround each platform to the east, south, and west (the north walls remain unexposed). Traces of baked brick thresholds can be seen on the right (south).158. Circular platform. In 1998, the circular platform first exposed by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in 1946 was re-exposed and the area around the platform was expanded to reveal the presence of the room in which it was enclosed. The brick walls had been removed by brick robbers and only the mud brick foundations were preserved along with a few tell-tale baked bricks. This particular platform seeems to date to the beginning of the Harappa Phase Period 3C (c. 2200 BC).

159. New circular platform. To the west of Wheeler's circular platform a new platform was discovered. This platform was excavated using modern stratigraphic procedures and detailed documentation. Charcoal, sediment, animal bone, charred plant and other botanical samples were collected from each stratum to complement the other artifacts such as pottery, seals and domestic debris. These samples should allow a more precise reconstruction of the function of these enigmatic structures. harappa.com

Slide 353. harappa.com Circular platforms in the southwestern part of Mound F excavated by M.S. Vats in the 1920s and 1930s, as conserved by the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan.

Slide 355. harappa.com The circular platform excavated by Wheeler in 1946 (left) and the one excavated by HARP in 1998 (right). Both of these platforms were found inside small square rooms that originally had baked brick walls, subsequently removed by brick robbers (Trench 43).Circular platforms in the southwestern part of Mound F excavated by M.S. Vats in the 1920s and 1930s.

Indus valley mystery. Archaeology and language: Archaeological context of Indus script cipher.

The Tuatha Dé Danann also brought four magical treasures with them to Ireland, one apiece from their Four Cities:

Lugh is a hero skilled in the use of spear.

Claíomh Solais means in Irish, 'sword of light' held by Nuada or Nuadu (modern spelling: Nuadha), known by the epithet Airgetlám (modern spelling: Airgeadlámh, meaning "silver hand/arm"), who was the first king of the Tuatha Dé Danann,"people(s)/tribe(s) of the goddess Danu".

Dagda's cauldron. "The name Dagda may ultimately be derived from the Proto-Indo-European *Dhagho-deiwos "shining divinity", the first element being cognate with the English word "day", and possibly a byword for a deification of a notion such as "splendour". This etymology would tie in well with Dagda's mythic association with the sun and the earth, with kingship and excellence in general. *Dhago-deiwos would have been inherited into Proto-Celtic as *Dago-deiwos, thereby punning with the Proto-Celtic word *dago-s "good".http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dagda In some texts, Dagda is a father-figure and a protector of the tribe; his mother is Danu.

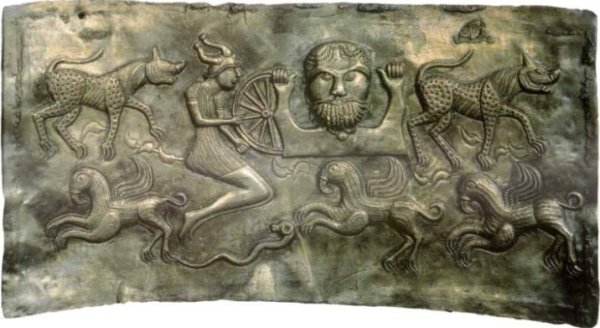

This is an inner plate of the Gundestrup cauldron.

Base plate

The circular base plate depicts a bull. Above the back of the bull is a female figure wielding a sword, as well as two dogs, one over the bull's head and another under its hooves.

Exterior plates

Each of the seven exterior plates centrally depicts a bust. Plates a, b, c, and d show bearded male figures, and the remaining three are female.

- On plate a, the bearded man holds in each hand a much smaller figure by the arm. Each of those two reach upward toward a small boar. Under the feet of the figures (on the shoulders of the larger man) are a dog on the left side and a winged horse on the right side.

- The figure on plate b holds in each hand a sea-horse or dragon.

- On plate c, a male figure raises his empty fists. On his right shoulder is a man in a "boxing" position, and on his left shoulder, there is a leaping figure with a small horseman underneath.

- Plate d shows a bearded figure holding a stag by the hind quarters in each hand.

- The female figure on plate e is flanked by two smaller male busts.

- A female figure holds a bird in her upraised right hand on plate f. Her left arm is horizontal, supporting a man and a dog lying on its back. Two birds of prey are situated on either side of her head. Her hair is being plaited by a small woman on the right.

- On plate g, the female figure has her arms crossed. On her right shoulder, a scene of a man fighting a lion is shown. On her left shoulder is a leaping figure similar to the one on plate c.

Interior plates

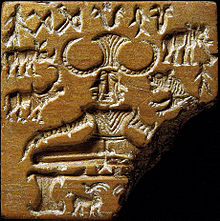

- Plate A shows an antlered male figure seated in a central position, likely Cernunnos. In his right hand, the figure is holding a torc, and with his left hand, he grips a horned serpent by the head. To the left is a stag with antlers that are very similar to the humanoid. Surrounding the scene are other canine, feline, and bovine figures, as well as a human figure riding a fish or a dolphin. Between his antlers, is an unknown image, possibly a plant or a tree, the identity of which is currently disputed.

- On plate B, the bust of a female is flanked by two six-spoked wheels, two elephant-like creatures, and two griffins. A large hound resides underneath the bust.

- The bust of a bearded figure holding on to a broken wheel is the main constituent of plate C. A smaller, leaping figure with a horned helmet is also holding the rim of the wheel. Under the leaping figure is a horned serpent. The group is surrounded by griffins and other creatures, some similar to those on plate B. The wheel's spokes are rendered asymmetrical, but judging from the lower half, the wheel may have had twelve spokes.

- Plate D depicts a bull-slaying scene. Three bulls are arranged in a row, facing right, and each of them is attacked by a man with a sword. A cat and a dog, both running to the left, appear respectively over and below each bull.

- On the lower half of plate E, a line of warriors bearing spears and shields march to the left accompanied by carnyx players. On the left side, a large figure is immersing a smaller man in a cauldron. On the upper half, facing away from the cauldron are warriors on horseback.

"For many years, scholars have interpreted the cauldron's images in terms of the Celtic pantheon. The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as Cernunnos, and the figure holding the broken wheel in plate C is more tentatively thought to be Taranis. There is no consensus regarding the other figures. Some Celticists have explained the elephants depicted on plate B as a reference to Hannibal's crossing of the Alps"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gundestrup_cauldron

"This seal from the Indus Valley Civilization. is remarkably similar to the antlered figure of plate A."

(Taylor, Timothy (1992), “The Gundestrup cauldron”, Scientific American, 266: 84-89; Ross, Ann (1967), “The Horned God in Britain ”, Pagan Celtic Britain.)

See: http://www.hindunet.org/saraswati/gundestrup1.pdf for a bibliographical account of sources related to hieroglyphs on the gundestrup cauldron compared with Indus writing hieroglyphs. The comparable hieroglyphs could not have occurred merely by chance. It is reasonable to hypothesize 1. that Meluhhan artisans and traders of the Bronze Age had contacts with ancient Celts who created the hieroglyphs on the Gundestrup cauldron and 2. that these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha with glosses related to metalwork.

Old Ireland narratives document that the supernaturally-gifted Tuatha Dé Danann (or Tuath Dé) represent the main pagan gods of Ireland. They come to Ireland in dark clouds and land on a mountain in the west.

Dana [ˈd̪ˠanˠə]) is a hypothetical mother goddess of the Tuatha Dé Danann. "The etymology of the name has been a matter of much debate since the 19th century, with some earlier scholars favoring a link with the Vedic water goddess Danu, whose name is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *dhenh2- "to run, to flow", which may also lie behind the ancient name for the river Danube, Danuuius (perhaps of Celtic origin, though it is also possible that it is an early Scythian loanword in Celtic)."

(Koch, John (ed.), Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 569)

Bas-relief of triple Coventina, associated with water. Mother goddess (e.g. Danu) is revered in Celtic tradition.

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann is usually translated as "people(s)/tribe(s) of the goddess Danu". The Old Irish word tuath (plural tuatha) means "people, tribe, nation"; dé is the genitive case of día and, depending on context, can mean "god, gods, goddess" or more broadly "supernatural being, object of worship"

Tuath Dé also referred to the Israelites. "Danann is generally believed to be the genitive of a female name, for which the nominative case is not attested. It has been reconstructed as Danu, of which Anu (genitiveAnann) may be an alternative form.[1] Anu is called "mother of the Irish gods" by Cormac mac Cuilennáin.[1] This may be linked to the Welsh mythical figure Dôn.[1] Hindu mythology also has a goddess called Danu, who may be an Indo-European parallel. However, this reconstruction is not universally accepted.[4] It has also been suggested thatDanann is a conflation of dán ("skill, craft") and the goddess name Anann.[1] The name is also found as Donann and Domnann,[5] which may point to the origin being proto-Celtic*don, meaning "earth"[1] (compare the Old Irish word for earth, doman)."

(Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2006. pp.1693-1694.)

Tuath Dé brought in this Stone of Destiny. "Nuada, king of the Tuath Dé, loses his hand or arm in the battle and is thus no longer fit to be their king. He is replaced by Bres (a half-Fomorian), who becomes High King of Ireland, but he neglects his duties and mistreats his people. After seven years, Dian Cecht the physician andCredne the metalsmith replace Nuada's hand/arm with a working silver one, and he re-takes the kingship. The Tuath Dé then fight the Fomorians in the Second Battle of Moytura. Balor the Fomorian kills Nuada, but Balor's (half-Fomorian) grandson Lugh kills him and becomes king. The Tuatha Dé enjoy 150 years of unbroken rule."

"The Lebor Gabala, dating to the eleventh century, states that it was brought in antiquity by the semi-divine race known as the Tuatha Dé Danann. The Tuatha Dé Danann had travelled to the "Northern Isles" where they learned many skills and magic in its four cities Falias, Gorias, Murias and Findias. From there they travelled to Ireland bringing with them a treasure from each city – the four legendary treasures of Ireland. From Falias came the Lia Fáil. The other three treasures are the Claíomh Solais or Sword of Victory, the Sleá Bua or Spear of Lugh and the Coire Dagdae or The Dagda's Cauldron...Drawing upon the pagan myths of Celtic Ireland – both Gaelic and pre-Gaelic – but reinterpreting them in the light of Judaeo-Christian theology and historiography, it describes how the island was subjected to a succession of invasions, each one adding a new chapter to the nation's history." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lia_F%C3%A1il

http://www.megalithic.co.uk/modules.phpop=modload&name=a312&file=index&do=showpic&pid=23878

The Stone of Destiny at Tara Early morning sun casting long shadows from the Stone of Destiny. This view is looking roughly northwards.

The Lia Fáil and the eclipsed moon 4/3/07. Though the moon was fully in shadow and a blood red colour, the long exposure renders it a glowing orb (and also luckily renders the people walking in and out during the exposure invisible!).

| AngieLake (2007-03-06) | Another Wow-factor pic, but I still hate that collar of stones around Lia Fail! |

Standing Stone in Co. Meath. Atop the hill of Tara stands a stone pillar that was the Irish Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) on which the High Kings of Ireland were crowned; legends suggest that the stone was required to roar three times if the chosen one was a true king.

A theory that may predate the Hill of Tara's splendor before Celtic times is the legendary story naming the Hill of Tara as the capital of the Tuatha Dé Danann, pre-Celtic dwellers of Ireland. When the Celts established a seat in the hill, the hill became the place from which the kings of Mide ruled Ireland. There is much debate among historians as to how far the King's influence spread; it may have been as little as the middle of Ireland, or may have been all the northern half.

The Stone of Destiny |

| Sitting on top of the King's Seat (Forradh) of Temair is the most famous of Tara's monuments - Ireland's ancient coronation stone - the Lia Fail or "Stone of Destiny", which was brought here according to mythology by the godlike people, the Tuatha Dé Danann, as one of their sacred objects. It was said to roar when touched by the rightful king of Tara. WHICH STONE? Formerly located just north of the Mound of the Hostages (see map), it was moved to its current site after the Battle of Tara during the Irish revolution of 1798 to mark the graves of 400 rebels who died here. Some say the true Stone of Destiny was formerly the Pillow of Jacob from the Old Testament. They also claim it was flat and that it was moved from Tara by King Fergus of Scotland and was named the Stone of Scone which then became the coronation stone of British kings at Westminster Cathedral. Many historians accept that the present granite pillar at Tara is the true Stone of Destiny, but a number of people have argued that the Stone of Scone is in fact the real thing. One legend states that it was only one of four stones positioned at the cardinal directions on Tara - and it is interesting to note that the Hall of Tara, the ancient political centre of Ireland, is aligned North-South. |

|

Map of the Hill of Tara (Temair) This map of the monuments on the Hill of Tara is based on an old map drawn in the 1830s. It shows just how many monuments are situated in the area. Some areas of the map are clickable and will open up pictures of the various monuments.A number of ancient stories relate how five great roadways radiated from Tara. One story names them - Slige Midlúachra, Slige Asail, Slige Chualann, Slige Dala and Slige Mór. One of these, Slige Chualann, is shown on the map above. There are a number of disused roads which converge at Tara, but it is not known if these are the same routes mentioned in antiquity. NOTE: This map was used as the label illustration on the 2003 CD album "Two Horizons", by Moya Brennan.The map was used with permission of www.mythicalireland.com, and credited in the inlay card. |

Some links related to Gundestrup cauldron:

http://jblstatue.com/gundstrup/home.html

http://www.abaxion.com/jbgcaul.htm

http://www.traditionalwitchcraft.org/celtic/gundestrup.html

http://www.aboutulverston.co.uk/celts/gundestrupbuddha.htm

http://aolsearch.aol.com/aol/search?query=Gundestrup%20cauldron

http://www.abaxion.com/jbgcaul.htm

http://www.traditionalwitchcraft.org/celtic/gundestrup.html

http://www.aboutulverston.co.uk/celts/gundestrupbuddha.htm

http://aolsearch.aol.com/aol/search?query=Gundestrup%20cauldron

'Thracian Tales on the Gundestrup Cauldron', Flemming Kaul, Ivan

Marazov, Jan Best, Nanny deVries. Najade Press, Amsterdam, 1991.

http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/g/gundestrup_cauldron.html

http://www.cyberwitch.com/wychwood/Temple/kernunnos.htm

http://www.sniffout.net/home/simontodd/herne.htm

http://www.realtime.com/~gunnora/vik_pets.htm

http://www.swampfox.demon.co.uk/utlah/shift/wolfbane.html

http://www.csp.org/chrestomathy/hallucinations2.htm

http://www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/bdogs.htm

http://www.collect.com.au/_numismatics/00000016.htm

http://sacredsource.com/gundestrup/

http://www.djames.demon.co.uk/celtic/cr01.htm

http://www.celtic-cauldron.com/images/gcauld.jpg

http://www.realtime.net/~gunnora/graphics/gundstrp.gif

http://www.celtica.wales.com/arddangosfa/gof/index.english.html

http://www47.pair.com/lindo/Classical.htm

http://www.britannica.com/bcom/eb/article/4/0,5716,119804+5,00.html

http://en2.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_mythology

http://www.celtic-cauldron.com/

http://jamesmdeem.com/bogphotos.htm

http://www.angelfire.com/me/ik/pics.html

Celtic Art - A Brief Overview by Tara

NicScothach bean MacAnTsaoir http://clannada.org/docs/art.html

Marazov, Jan Best, Nanny deVries. Najade Press, Amsterdam, 1991.

http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/g/gundestrup_cauldron.html

http://www.cyberwitch.com/wychwood/Temple/kernunnos.htm

http://www.sniffout.net/home/simontodd/herne.htm

http://www.realtime.com/~gunnora/vik_pets.htm

http://www.swampfox.demon.co.uk/utlah/shift/wolfbane.html

http://www.csp.org/chrestomathy/hallucinations2.htm

http://www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/bdogs.htm

http://www.collect.com.au/_numismatics/00000016.htm

http://sacredsource.com/gundestrup/

http://www.djames.demon.co.uk/celtic/cr01.htm

http://www.celtic-cauldron.com/images/gcauld.jpg

http://www.realtime.net/~gunnora/graphics/gundstrp.gif

http://www.celtica.wales.com/arddangosfa/gof/index.english.html

http://www47.pair.com/lindo/Classical.htm

http://www.britannica.com/bcom/eb/article/4/0,5716,119804+5,00.html

http://en2.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_mythology

http://www.celtic-cauldron.com/

http://jamesmdeem.com/bogphotos.htm

http://www.angelfire.com/me/ik/pics.html

Celtic Art - A Brief Overview by Tara

NicScothach bean MacAnTsaoir http://clannada.org/docs/art.html

Gundestrup Cauldron (La Tene Style)

...

Where Did the Gundestrup Cauldron Come From? Who Made It?

Scholastic opinion is divided on who made the cauldron and how it came to be found in Jutland. For although the Celts reached Britain and Ireland before the fourth century BCE as part of their expansion westwards, they never reached Denmark, which was occupied at the time by a people of Teutonic stock. (See also: History of Art Timeline.)

The Gundrestrup Cauldron Was Made in Gaul

Some scholars believe that the cauldron was made by Celtic craftsmen in Northern Gaul. In support of this view, they claim that the figures of gods on the walls of the vessel represent Celtic deities - for example, one antlered or horned figure is identified as Cernunnos, while the figure holding a broken wheel is believed to represent Taranis. Another Celtic scholar identifies the horned figure as Cú Chulainn, interpreting the entire tableaux of Gundestrup Cauldron as a precursor to the Irish myth of Táin Bó Cúailnge. In any event, all say that the appearance of torcs (neck bands) on some of the figures suggests a clear connection with Celtic culture.

Proponents of this theory date the cauldron to the final stage of late La Tene period (1st century BCE), as by this time, non-traditional Celtic images like fantastic animals start to appear on Celtic coins. In addition, they point to similarities between the Gundestrup and other bronze cauldrons of Late La Tène, made in central and western Europe. A case in point is the Rynkeby Cauldron, also discovered in Danish bogland, which is almost identical in size with similar decorative plates and some commonality of motifs.

The Gundrestrup Cauldron Was Made in Thrace

Opposing scholars, who claim that the cauldron is of Middle Danubian Thracian origin, date the vessel to the late 2nd century BCE, and base their case on the cauldron's construction technolgy (unknown in Gaul at the time), and point to the similarity between its animal imagery and that of other Thracian metalwork, as in the use of hatching lines and dot-punching to decorate animal bodies.

The dating of the cauldron is critical. If it really was constructed during the late 2nd century BCE, it cannot have originated in Gaul, because silver-smithing techniques like high repoussé, partial gilding, pattern punching and glass-insets - all of which were employed to make the cauldron - were not known by Gaulish craftsmen. Unfortunately, no precise dating or provenance of the cauldron can be established, as the silver used cannot be traced to a precise mine: however, the actual weight of silver used has been calculated to be the same as the weight of a standard number of Persian siglos, a coin commonly used in Thrace in the 2nd century BCE. The debate continues.

Whether made in Gaul or Thrace, how did the vessel arrive in Denmark? Several explanations have been mooted. Either it was imported into Denmark; or it was one of the spoils of war acquired by German cavalrymen from Denmark, employed by Roman commanders in Gaul. A more complex account has it being made by a silversmith in Thrace where it was looted by the Germanic Cimbri tribe - who had strong connections with Denmark - when they invaded the area in 120 BCE.

Art historian Timothy Taylor (1992) notes about the glyptics of the Gundestrup cauldron: "A shared pictorial and technical tradition stretched from India to Thrace, where the cauldron was made, and thence to Denmark. Yogic rituals, for example, can be inferred from the poses of an antler-bearing man on the cauldron and of an ox-headed figure on a seal impress from the Indian city of Mohenjo-Daro…Three other Indian links: ritual baths of goddesses with elephants (the Indian goddess is Lakshmi); wheel gods (the Indian is Vishnu); the goddesses with braided hair and paired birds (the Indian is Hariti).” He further speculates that members of an Indian itinerant artisan class, not unlike the later Gypsies in Europe who also originate in India, must have been the creators of the cauldron. (Taylor, T. 1992. "The Gundestrup cauldron.” Scientific American 266(March): 84-89.) Hindu Deities in Iron Age Denmark: The Religious Iconography and Ritual Context of the Gundestrup Cauldron This paper considers aspects of the second century BCE iconography of the Gundestrup cauldron in relation to the idea of death in various frameworks of thought and belief: Shamanistic, Mithraic, Pythagorean, Hindu, Celtic, Orphic, and Christian. Following from this, some general theoretical considerations about the relationship of iconographic, ritual, textual, and oral religious modes are presented. In the light of this, a precise context for the cauldron’s production and use is suggested. [Dr. Tim Taylor (University of Bradford). Univ. of Birmingham, Archaeology and World Religions, Session held on 19 December 1998]. http://www.bham.ac.uk/TAG98/pages/abs

Gundestrup Cauldron

Gundestrup Cauldron

Peat bog, Gundestrup (Denmark)

First century B.C.E.

Silver partially gilded

Diameter 69cm., Height 42cm.

Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet

The Gundestrup Cauldron is a religious vessel found in Himmerland, Denmark, 1891. It was deposited in a dry section of a peat bog, dismantled with its five long rectangular plates, seven short ones and one round plate. Each plate is made of 97.0% pure silver and filled with various motifs of animals, plants and pagan deities. Sophius Müller(1892) reconstructed these plates into the present form of the cauldron: five rectangular plates are placed in the inside of the cauldron leaving 2cm of space between each, and the seven (originally eight) plates form the outside of the cauldron. The round plate is assumed as the base of the cauldron. The reconstructed cauldron with its spherical base and cylindrical side is 69cm. in diameter and 42cm. high; both the inner and outer plates are almost of the same height ( about 21cm) forming the cylindrical side of the cauldron.

As the largest surviving piece of Europian Iron Age silver work, the Gundestrup Cauldron has been given a special interest by many scholars. Especially, its high quality workmanship and iconographic variety have generated an incessant inquiry into the origin of the cauldron. Though the date of the cauldron is generally attributed to the 2nd or 1st century BCE (La Tène III), there still remains much room for controversy concerning the place of its manufacture. The main problem comes from the fact that its style and workmanship is Thracian rather than Celtic despite its decorative motifs manifestly Celtic. So far, scholastic opinions have been largely divided into two groups: those who argue for the Gaulish origin and those who argue for the Thracian origin. The former locate the manufacture of the cauldron in the Celtic west while the latter opt for the Lower Danube in southeastern Europe.

Those who argue for the Gaulish origin usually locate the cauldron in the final stage of late La tène period, because by this time, such non Celtic elements as fantastic animals began to appear in the diverse representations on the Celtic coinage. They also draw analogy with other bronze cauldrons of Late La Tène period from central and western Europe. The Rynkeby Cauldron which also comes from a Danish bog is the closest example to the Gundestrup Cauldron: they are almost of the same size; both have decorative plaques forming the interior of the upper cylindrical wall; they share some motifs such as a human bust on the outer plates. Since the Rynkeby Cauldron is assumed to be made around 1st century BC, in northern or central Europe, Olmsted argues that the Gundestrup Cauldron, like the Rynkeby Cauldron, has a La Tène III origin.

On the other hand, proponents of the eastern view base their arguments on the cauldron’s silver smithing techniques and its portrayal offantastic animals which are commonly observed in Thracian metal work. Powell(1971) claims the Thracian heritage by demonstrating a strong stylistic analogy between the Gundestrup Cauldron and Thracian phalerae. The techniques of decorating bodies of animals with hatching lines and punched dots are common in both. Most recently, Bergquist and Taylor further developed his argument. By locating the cauldron in late 2ndcentury BC, they claimed that silver-smithing techniques used for the cauldron such as high repoussé, pattern punches and tracers, partial gilding, and insetting of glass are as yet unknown from the Celtic West. Bergquist and Taylor divide the Thracian style into two periods: earlier style by the fourth century BC when, after Persian invasion, distinctive and original animal style art had emerged in Thracia, and later style at the turn of the 2nd and 1st century when the hoards of silver vessels reappeared after two hundred years of absence. They consider that the two styles are basically homogeneous except that in the later style, human figures are emphasized and usually rendered in high repoussé and they conclude that the Gundestrup Cauldron shows the traits of both styles.

If the Cauldron was made elsewhere than Denmark, then how did it make its way north to Jutland ? To explain its discovery in Denmark, several options are brought up. Klindt Jensen assumes that the cauldron was a Celtic object imported into Denmark. Olmsted suggests that it was a war booty because the Romans employed Germanic cavalry in Gaul. Bergquist and Taylor propose that it was made in southeast Europe by a Thracian silver smith, possibly commissioned by Celts (Scordisci)and transported by Cimbri who invaded the Middle lower Danube in 120 BC and looted the Scordisci. They make conjecture that since the cauldron takes the 4th century BC Thracian style and lacks the Roman tradition, it was made between fourth and first century BC.

(base) | Each plate of the cauldron is labeled after Klindt-Jensen whose labeling is generally adopted by the other scholars. Five inner plates are labeled in capitalized letters, and seven outer plates are labeled in small letters. |

(A) (B) (C) (D) (E)

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g)

Bibliography

- Arbman, H., "Gundestrupkitteln- ett galliskt arbete?," Tor 20, 1948, pp.109-116.

- Bémont, C., "Le Bassin de Gundestrup: remarques sur les décors végétaux, Etudes Celtiques, vol. 16, Paris, 1979, pp. 69-99.

- Benner Larsen, E., "The Gundestrup Cauldron, Identification of Tool Traces," Iskos, vol. 5, 1985, pp. 561-74.

- Berciu, D., Arta traco-getica, Editura Aacademiei, Bucharest, 1969.

- Bergquist, A. K., and T. F. Taylor, "Thrace and Gundestrup Reconsidered," Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Celtic Studies, Oxford: D. Ellis Evans, 1983, pp.268-9.

- ------------------------------, "The origin of the Gundestrup Cauldron," Antiquity, vol. 61, 1987, pp. 10-24.

- Bober, J.J., "Cernunnos: Origin and Transformation of a Celtic Divinity," American Journal of Archeaology 55, 1951, pp13-51.

- Davidson, H. E., The Lost Belief of Northern Europe, 1993.

- -------------------, "Mithraism and the Gundestrup bowl," Mithraic Studies Vol. II (edited by John R. Hinnells), Rowman and Littlefield, Manchester, 1975.

- Drexel, F., "Über den Silberkessel von Gundestrup," Jahrbuch des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 30, 1915, pp.1-36.

- Grosse, R., Der Silberkessel von Gundestrup, ein Ratsel keltische Kunst, Goetheanum, Dornach, 1963.

Hawkes, C. F. C., " Continental and British Anthropoid Weapons", Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, XXI, 1955, pp. 198-227. - Hawkes, C.F.C., and M.A. Smith, "On Some Buckets and Cauldrons of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages," Antiquity XXXVII, 1957, pp.131-98.

- Jacobsthal, P., Early Celtic Art, Oxford, 1944.

- Kimmig, W., "Zur Interpretation der Opferszene auf den Gundestrup-Kessel," Fundberichte aus Schwaben, N.S. xvii, 1965, pp.135-43.

- Klindt-Jensen, O., "The Gundestrup Bowl-a reassessment," Antiquity, vol.33, pp.161-9.

- ---------------------, Gundestrupkedelen, Copenhagen, 1979

- Laet, S. J. and P. Lambrechts, "Traces du culte de Mithra sur le chaudron de Gundestrup," Actes du troisième Congrès International des sociétés pré- et protohistoriques, Zurich: City-Druck, 1950, pp. 304-6.

- Megaw, J. V. S., Art of the European Iron Age, Adams & Dart, Bath, 1970.

- Meyers, p., "Three silver objects from Thrace: a technical examination," Metropolitan Museum Journal 16, 1981, pp.49-54.

- Müller, Sophus, "Det store Slvkar fra Gundestrup i Jylland," Nordiske Frotidsminder, I, 1892, pp.35-68.

- -------------------, Nordische Altertumskunde, vol. 2, Strasburg, 1898.

- Nylen, E., "Gundestrupkitlen och den thrakiska konsten," Tor 12, Uppsala, 1967, pp. 133-73.

- Olmsted, G.S., "The Gundestrup version of Táin Bó Cuailnge," Antiquity, vol.50, pp.95-103.

- -----------------, The Gundestrup Cauldron, Collection Latomus, No. 162, Brussels, 1979.

- Petersen, E., "A Gundestrup edény és a Csórai dombormu," Archeologiai Ertesito 13, pp.199-202.

- Piggott, S., "The Carnyx in Early Iron Age Britain," The Antiquaries Journal XXXIX, 1959, pp.19-32.

- -------------, "Supplementary notes on the illustrations," The Celts (T.G.E. Powell, 2nd ed), London: Thames & Hudson, 1980, pp.210-217.

- Pittioni, R., Wer hat wann und wo den Silberkessel von Gundestrup angefertigt? Veröffentilichungen der keltischen

- Akademie der Wissenschaften 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Asademia der Wissenschaften, 1984.

- Powell, T.G.E., "From Urartu to Gundestrup: the agency of Thracian metal-work," The European Community in LaterPrehistory, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1971.

- Ramskou, T., "Gundestrupterrinen," Skalk 4, 1977, p.32.

- Reinach, S., "À propos du vase de Gundestrup," L’Anthropologie 5, 1894, pp.456-8.

- --------------, "Zagreus, le serpent cornu," Revue Archéologique, XXXV, 1899, pp.210-217.

- --------------, "Les Carnassiers androphages dans l’art gallo-romain," Revue Celtique 25, 1904, pp.207-24.

- Reinecke, P., "Autremont und Gundestrup," Praehistorische Zeitschrift 34-5 (1), 1950, pp.361-72.

- Rusu, M., "Das Keltische Fürstengrab von Ciumesti in Rumänien, Bericht der Römisch-germanischen Kommission 50, 1969, pp.267-300.

- Sandars, N. K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Bartimore, 1968.

- ------------------, "Orient and Orientalizing in Early Celtic Art," Antiquity XLV( no.178, 1971), pp.103-112.

- ------------------, "Orient and Orientalizing: recent thoughts reviewed," Celtic Art in Ancient Europe (C.F.C. Hawkes and

P.M. Duval ed.), London, 1976, pp.41-57. - Willemoes, A., Hvad nyt om Gundestrupkarret, Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark, Copenhagen, 1978.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

January 6, 2015