Rearranging the United Indian Ocean States in relation to the European Community

Thanks to Robert D. Kaplan for drawing attention to the power shift which occurs with United States getting out its global cop war machine from Afghanistan.

It is time to rethink the region south of the Himalayan ranges, on the lines of European Union which was the sequel to the war-ravaged Europe after the Second World War.

It is good to pay attention to the world map which is dynamically shifting with the upliftment of the dynamic Himalayas 1 cm every year thanks to the continental drift and resultant plate tectonics in a mind-boggling range of glacial heights stretching from Teheran in the West to Hanoi in the East.

The glacial heights with accumulating glaciers above the height of 8000 ft. from sea level constitute the dynamically growing largest water tower of the world, yielding five perennial river systems: Brahmaputra, Sindhu, Ganga, Yangtse, Huanghe, Irawaddy, Salween, Mekong watering the areal plains south of Himalayas and skirting the Indian Ocean Rim and stretches east of the Gobi desert in China.

The geostrategic geographical reality of the Indian Ocean as it meets the Pacific Ocean is a community whose historical evolution is titled by the great French Epigraphist, George Coedes as: Histoire ancienne des États hindouisés d'Extrême-Orient, 1944? (Translation: Ancient History of Hinduised States of the Great Orient). This historical, civilization reality of United Indian Ocean States (UIOS) has to be formed in relation to the European Community.

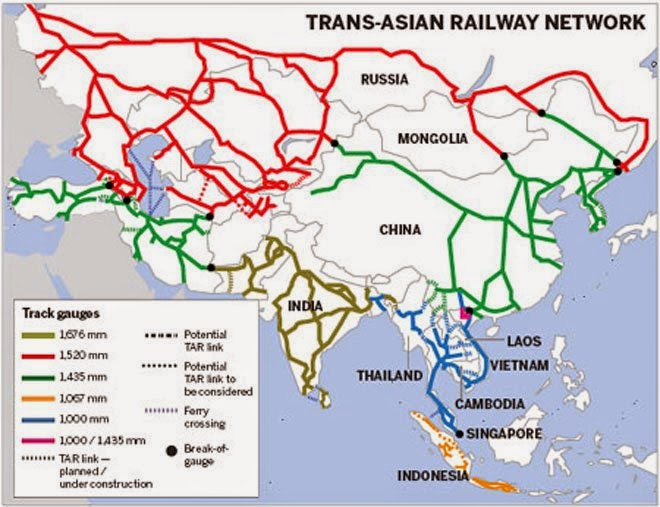

Projects are ready to take off to firm up this relationship of UIOS with the European Community:1. Trans-Asian Railway; and 2. Trans-Asian Highway. Another major project relates to the replication of the Himalayan Mekong River Delta projects for other River systems which are sourced from the Himalayan ranges.

Obama who has been invited by Narendra Modi to be present on the Republic Day of India on 26 January 2015 should seize the moment and together, Obama-Modi declaration should be a clarion call to make United Indian Ocean States a reality. This UIOS will be a culmination of the cultural confluence achieved by the inviolate founding principles of Dharma-Dhamma. The largest Vishnu mandiram for Narayana is in Angkor Wat, Nagara Vatika in Cambodia. The Meluhha/Mleccha Bharatam Janam exemplified by the Verman and rashtrakuta leaders who set up the Ananthasayanam in Thiruvananthapuram also set up this temple under the Pancharatra Agama tradition of Bharatam. Bharatam Janam is not a construction, it is a self-identity narrated by Viswamitra in Rigveda. Bharatiyo in Gujarati means 'casters of metal'; bharath in Marathi means alloy of copper, tin, zinc, pewter. These were the Bharatam Janam, pitr-s -- ancestors -- of the over 2 billion people of the region, who transited the chalcolithic phase of technology into the Bronze-Metals Age of circa 5th millennium BCE. The Rigveda is a narrative of this millennium. The Indian Ocean Community through the state apparatus of UIOS is the well-watered,, well-lighted path, the Rashtram राष्ट्रं . Meluhha, mleccha constituted the lingua francaof the sprachbund, the language union binding the regions of this nation, which used to be referred to in the colonial periods as 'Greater India'.

The term aasetu himachalam has to be rearranged as the UIOS bounded by the Himalayas on the north and the Indian Ocean -- Hindumahasagar -- stretching from South Africa and Madagascar in the West to Fiji and Tasmania in the East, till the boundaries of the Pacific Ocean.

The choke points of maritime network of the globe are Straits of Hormuz and Straits of Malacca, both in the Indian Ocean. Guarding the sealanes can be done effectively only by the UIOS as a joint enterprise. In this enterprise, a stellar beginning has been made by Modionoz after signing strategic defence partnership with Australia which spans the waters where Indian Ocean joins the Pacific Ocean.![]()

This ain't NO maritime silk road, but the lifeline of United Indian Ocean States.

UIOS will be a 10 trillion-dollar combined GDP powerhouse which is the potential answer to the recurring world financial crises by taking the globe on a development path of a magnitude unprecedented in the five millennia story of civilizations.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

December 28, 2014

WASHINGTON 43,736 views

Rearranging the Subcontinent

Robert D. Kaplan is the author of Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific, which was published by Random House in March 2014. In 2012, he published The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us about Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate, and in 2010, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power. In both 2011 and 2012, he was chosen by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the world's "Top 100 Global Thinkers."

Robert D. Kaplan is the author of Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific, which was published by Random House in March 2014. In 2012, he published The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us about Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate, and in 2010, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power. In both 2011 and 2012, he was chosen by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the world's "Top 100 Global Thinkers."The division of the Indian subcontinent between two major states, India and Pakistan (as well as a minor one, Bangladesh), may not be history’s last word in political geography there. For, as I have previously observed, history is a record of many different spatial arrangements between the Central Asian plateau and the Burmese jungles.

For example, Pakistan can only be considered artificial if one is ignorant of the past in the region. Pakistan is merely the latest of various states and civilizations anchored either in the Indus River valley or in that of the Ganges. The chieftaincies of the late fourth to mid-second millennium B.C., comprising the Harappan civilization, stretched from Balochistan northeast up to Kashmir and southeast almost to Delhi and Mumbai — that is, greatly overlapping both present-day Pakistan and India. From the fourth to the second century B.C., large areas of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India all fell under Mauryan rule. There was, too, the Kushan Empire, whose Indo-European rulers governed at times from what used to be Soviet Central Asia all the way to Bihar in northeastern India. And so it goes: For so much of history, there was simply no border between Afghanistan, Pakistan and the northern third of India — the heart of the Gangetic state.

And whereas the geography between Afghanistan and northern India was often politically united, the geography between today’s northern India and southern India was often divided. The point is, nothing we see on the current map should be taken for granted or, for that matter, is particularly anchored in history.

It was the British who actually created what in logistical terms is the subcontinent, uniting what is now India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in the late 19th century through a massive railway grid that stretched from the Afghan border in the northwest to the Palk Strait near Sri Lanka in the deep south, and from Karachi in Pakistan to Chittagong in Bangladesh. (The Mughals and the Delhi sultanate also unified many of these areas, but through a looser system of control.) Because Afghanistan was ultimately unconquerable by British forces in the 19th century and also had a difficult terrain, it was left out of this modern railway civilization. But don’t assume that this particular British paradigm will last forever.

In fact, it has been crumbling for decades decades already. Pakistan’s de facto separation from Afghanistan began to end somewhat with the Soviet invasion of the latter country in December 1979, which ignited a refugee exodus down the Khyber and other passes that disrupted Pakistani politics and worked to further erode the frontier between the Pashtuns in southern and eastern Afghanistan and the Pashtuns in western Pakistan. By serving as a rear base for the Afghan mujahideen fighting the Soviets during that decadelong war, which I covered first hand, the Soviet-Afghan war helped radicalize politics inside Pakistan itself. Johns Hopkins University Professor Jakub Grygiel observes that when states involve themselves for years on end in irregular, decentralized warfare, central control weakens. For a concentrated and conventional threat creates the need to match it with a central authority of its own. But the opposite kind of threat can lead to the opposite kind of result. And because of the anarchy in Afghanistan in the 1990s following the Soviet departure and the continuation of fighting and chaos in the decade following 9/11, Pakistan has had to deal with irregular, decentralizing warfare across a very porous border for more than a third of a century now. Moreover, with American troops reducing their footprint in Afghanistan, the viability of Afghanistan could possibly weaken further, with a deleterious effect on Pakistan.

This raises the question of the viability of Pakistan itself and, by association, the continued existence of the current hard-and-fast borders of India, especially given that Bangladesh as well is, in relative terms, a weak and artificially conceived state in almost never-ending turmoil.

Pakistan is not necessarily artificial, of course. As Stratfor has written, Pakistan is the demographic and national embodiment of all the Muslim invasions that have passed down into India through much of history. It is artificial only to the extent that this vast Muslim demography, rather than configuring with a state, extends all the way from Anatolia to central India, and thus the specific borders of Pakistan only work to the extent that Pakistan is reasonably well governed, with responsive bureaucratic institutions, and possesses a civil society that reaches into the tribal hinterlands. But that is demonstrably not the case.

So Afghanistan truly matters, if not necessarily to American grand strategy than to the political destiny of Pakistan and thus to the Greater Indian subcontinent.

A post-American Afghanistan means a number of things. It means some further consolidation of Iranian influence in the western and central parts of the country and an extension of some Iranian influence in eastern Afghanistan as well. This is because Pakistan will be frustrated in projecting even more influence into eastern and southern Afghanistan because of its own Taliban problem on its side of the border. In the 1990s, Pakistan could simply provide logistical and other means of support to the Afghan Taliban; now it is not so easy. At the same time, though, the Saudis will work through the Pakistanis to project whatever influence they can in Afghanistan. And Russia, through the Central Asian republics — whose ethnic groups have compatriots inside northern Afghanistan — might exert more influence, too. India will work with both the Iranians and the Russians to exert its own influence as a limiting factor to that of the Pakistanis and the Saudis, even as the Pakistanis lately try to balance between the Iranians and the Saudis. Such competing outside influences and interferences may tend to work against central control from Kabul rather than in support of it. And an Afghanistan in partial chaos — let alone a complete state breakdown — may work over time to further destabilize Pakistan.

Of course, Pakistan would not suddenly collapse in this scenario. But it could decay in an exceedingly gradual way that its supporters and attendant area experts might at first be able to deny, even as the evolving mundane facts on the ground would be undeniable. The signs of decay are electricity outages, water shortages, a further deterioration of the urban environment, the inability to travel here and there in outlying areas because of security issues, the inability to get much done at a government office without a bribe or a fixer. Pakistan has experienced such phenomena for decades already; the key will be the increase or decrease in their intensity. A state that cannot monopolize the use of force and cannot supply adequate public services is weak. Pakistan we know is weak, despite the strengthening of its democracy and civil society in recent years. It already has ongoing insurgencies in the tribal areas, in Balochistan and in Karachi. But will it become steadily weaker? Because prime ministers and presidents come and go, I am thinking beyond the high politics in Islamabad, New Delhi and Kabul and am more concerned with the granular, ground level reality in places such as Karachi or Quetta, or in the other parts of Sind and Balochistan.

What would a terminally diseased Pakistani state come to look like? It might see more feisty regionalism in the southern provinces of Balochistan and Sind, whose leaders told me on a trip through the area some years ago that they would prefer over time a closer relationship with New Delhi than with Islamabad. These are people who never accepted a strong Pakistani state to begin with and always advocated more federalism. With Balochistan and Sind moving closer to India, and the Afghanistan-Pakistan Pashtun border area in permanent disarray because of turmoil inside Afghanistan according to such a scenario, then a rump state of Greater Punjab might begin to emerge — again, denied for years by officials up until the point that it is undeniable.

India, of course, would not like any of this. Top officials of responsible states — which India certainly is — prefer the status quo and quiescent borders, not their opposite. But India might at some point in the 21st century have no choice but to confront Pakistan’s partial dissolution, and that would irrevocably change India.

Because geopolitics values not the ceremonial statements of leaders but the reality of control on the ground, the Indian subcontinent will continue to fascinate. It is important to note here Henry Kissinger’s view on India in his latest book, World Order: “India will be a fulcrum of twenty-first-century order: an indispensable element, based on its geography, resources, and tradition of sophisticated leadership, in the strategic and ideological evolution of the regions and the concepts of order at whose intersection it stands.

Power Shifts

By ANNE-MARIE SLAUGHTER

October 7, 2012

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Illustration by MoMA Design Studio

October 7, 2012 |

Illustration by MoMA Design Studio

THE REVENGE OF GEOGRAPHY

What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate

By Robert D. Kaplan

Illustrated. 403 pp. Random House. $28.

Those who forget geography can never defeat it. That is the mantra of Robert D. Kaplan’s new book, “The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate.”Each chapter begins with a reading of the lineaments of territory in the way a fortuneteller reads the lines on a palm, a mapping of mountains, rivers and plains as determinants of destiny. But just as the text starts to teeter under the weight of geographical determinism, Kaplan quickly shifts ground, arguing for “the partial determinism we all need” (italics in the original). He retreats to the far more moderate view that geography is an indispensable “backdrop” to the human drama of ideas, will and chance.

Kaplan, a correspondent for The Atlantic and a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, resurrects 19th- and early-20th-century thinkers like Halford J. Mackinder, whose 1904 article “The Geographical Pivot of History” argued that control of the Eurasian “Heartland” would determine the fate of empires. Similarly, other contemporaneous strategists like Alfred Thayer Mahan and Nicholas J. Spykman may have favored sea power over land power, but they still described world history in terms of the eternal clash between the two (Sparta versus Athens, Venice versus Prussia). Spykman also answered Mackinder’s Heartland obsession with a focus on European, Indian and Pacific “Rimlands.”

Most of what these authors proposed would sound politically incorrect today — imperialist and racist. Mackinder’s theories were appropriated (misappropriated, according to Kaplan) by the Nazis. Still, these geostrategists saw past the ritualized etiquette of diplomacy and the embedded expectations of law to the stark and enduring struggle for survival — tribe against tribe, invaders against inhabitants. Their strength lies in their appreciation of the ways in which the fixed elements of geography and climate shaped the more variable element of human choice — the story Jared Diamond tells today in his classic “Guns, Germs, and Steel.”

Perhaps the best test of their value is the quality of Kaplan’s own geopolitical analysis in their wake. He applies his geography-first approach to different regions of the world, yielding a number of predictions that upend conventional wisdom. On Europe, he sees — accurately, in my view — that the Mediterranean will once again “become a connector,” linking southern Europe and northern Africa as it did in the ancient world, rather than continuing to be the dividing line between former imperial powers and their former colonies. The lands of olive and vine are likely once again to become an economic and cultural community, powered perhaps by the enormous reserves of natural gas and oil under the northern and eastern Mediterranean seabed. More generally, the sheer demographic and economic size of the European Union, notwithstanding gloomy projections on both counts, leads Kaplan to conclude that it “will remain one of the world’s great postindustrial hubs.” The shift from Brussels to Berlin as the center of gravity for European politics will thus have global implications.

Moving east, Kaplan renders a verdict on Russia that again undercuts the determinism of his title. Vladimir Putin and Dmitri Medvedev, he writes, “have had no uplifting ideas to offer, no ideology of any kind, in fact: what they do have in their favor is only geography. And that is not enough.” That same geography “commands a perennially tense relationship between Russia and China,” even as a shared commitment to authoritarian government and sovereign prerogatives pushes their regimes together.

In the Middle East and Southwest Asia, Kaplan’s geographic lens uncovers an unexpected similarity between Iran and Saudi Arabia. He describes them both as loose aggregations of tribes, peoples, and lands — centers that often cannot hold their far-flung dominions together. Saudi history is a seesaw back and forth between the Wahhabi “heartland of Najd” and “the peripheries of the Arabian Peninsula.” And Iran “has often been less a state than an amorphous, multinational empire.” The suffix “istan” is Persian for “place,” meaning that the “stans” of Central Asia — Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and the rest — reflect a map drawn in Tehran.

Moving away from the heartland, it is in the Western Hemisphere that Kaplan’s framework yields the most surprising results — an unusual amalgam of Samuel Huntington and Fernand Braudel: “America, I believe, will actually emerge in the course of the 21st century as a Polynesian-cum-mestizo civilization, oriented from north to south, from Canada to Mexico, rather than as an east to west, racially lighter-skinned island in the temperate zone stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific.” He is right to concentrate on the intersection of demographics and hemispheric geography, but the pressure for greater hemispheric integration is as likely to come from economic competition with Asia and Europe as from demography. And indeed, Kaplan himself concedes part of the point: he sees a world in which an “organic and united Eurasia” will demand an “organic and united North America” as a “balancer.”

This geographic tour of the world rests on a very 19th-century concept of what a map is.Kaplan defines it as “the spatial representation of humanity’s divisions,” by which he means not just a representation of physical territory, but of topography. He sees the world as a relief map, one defined by the sharp peaks and narrow valleys that trap populations and the open plains and broad waterways that impel and allow them to move. His emphasis on humanity’s “divisions” is telling, leading directly to his embrace of realism in foreign policy. Kaplan assumes that humankind is in essence divided rather than connected, even though an objective view of the landscape would allow for either. His geopolitical outlook is reinforced by his reliance on the Thucydidean trilogy of “fear, self-interest and honor” as basic human motivations — a take on human nature that is both old-fashioned (at least in the era of neuroscience and cognitive psychology) and very male.

Besides, why is the true map a map of land rather than of people? Social media and mass data flows of all kinds now give us the ability to see and represent human interactions as never before, mapping emotions, desires, aspirations and connections. The intersection of millions of small worlds can now be tracked and visualized: human galaxies every bit as dense and complex as the stars above. The program Google Flu Trends allows us to map disease outbreaks by tracking when and where incipient sufferers enter a search for flu symptoms. Financial transactions can be mapped through banks; in the coming age of mobile money, they will be mappable through GPS and cellphones.

The result will be a new discipline of sociography. Kaplan himself describes the less-developed megacities of the 21st century as vast citadels of solitary striving, creating a “new urban geography . . . of intense, personal longing.” This section is tantalizing but all too brief, particularly since the maps of that longing will soon be as detailed as the depictions of the cities themselves.

At the same time, we will increasingly understand just how subjective our physical maps are. Google Earth and Google Maps make it possible for people to become their own cartographers, literally putting themselves on the map. Kaplan may argue that the brightly colored patches of sovereign territory on a two-dimensional map obscure Nature’s primordial blueprint, but citizens now have incentives to obscure the lines of their governments with the demarcations of their own communities, imagined and real.

In the end, the revenge of geography will be the revenge of human as well as physical geography: a world much more, and much more democratically, of our making.

.jpg)