It is time to restate Economics in the Hindu dharma tradition -- not as a mere science but Arthaśāstrá, wealth next only to dharma as a life imperative for abhyudayam, 'welfare'. See notes on Guilds in Ancient India and śrēṇidharma

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/08/guilds-in-ancient-india-jeannine.html Elimination of greed in social transactions, for instance, is a step in avoiding accumulation of kaalaadhan.

Some select anecdotes on the foibles of economist ideologues and the slippery nature of Economics Science follows.

Kalyanaraman

'It is high time to jettison Sen'

Last updated on: July 26, 2013 21:47 IST

Sheela Bhatt

Jagdish Bhagwati keeps the debate with the Nobel Laureate raging in this interview with Sheela Bhatt

Do you think the so-called Gujarat model or Professor Sen’s idea of growth and development has some meeting point? Can you elaborate?

How can one reconcile Sen’s vacuous arguments with the growth strategy, which our leaders like Pandit Nehru and the planners I worked with, like Pitambar Pant in the

Planning Commission, (drew up), and which has transformed India since the 1991 reforms and has thence reduced poverty remarkably?

Indians often have a habit of reconciling the irreconcilables: Asti Nasti (in some ways it is and it is not)! That way is confusion and muddled policymaking, which we suffered from prior to the 1991 reforms.

It is high time to jettison Sen and carry on with our historic task of deepening and broadening what I and Professor (Arvind) Panagariya call ‘growth-enhancing’ Track I reforms, and cleaning up the revenues-spending reforms for the poor, which we call Track II reforms, where also Sen has ideas that are harmful to the poor.

Which model of development is best-suited for India?

Certainly not the Kerala model or the Bangladesh model, which Sen has successively advocated without any compelling analysis.

There are aspects of Gujarat development in the post-1991 period, including Modi’s recently, which I admire, as I pointed out in my article on the differences between me and Sen, especially how Gujaratis believe in accumulating wealth, but spending it on social good rather than on themselves.

This is our Vaishnav and Jain tradition; and it is an ideal model.

Modi also has written a book on the environment. He is also totally corruption-free. Gujarat’s social indicators, traditionally on the low side, have also registered remarkable improvement. All this must be applauded.

http://www.rediff.com/money/slide-show/slide-show-1-exclusive-bhagwati-says-sen-is-politicising-the-development-debate/20130726.htm#1 WEDNESDAY, FEB 20, 2013 03:54 AM IST

How Paul Krugman broke a Wikipedia page on economics

An "edit war" breaks out over the Nobel Prize-winner's critique of ultra-conservative Austrian economics

Enlarge(Credit: Reuters/Brendan Mcdermid)

Enlarge(Credit: Reuters/Brendan Mcdermid)There’s a lockdown on the Wikipedia page for Austrian economics and wouldn’t you know it, one or way or another, it all seems to be Paul Krugman’s fault.

Broadly speaking, Austrian economics, for those who have not yet had the pleasure of being introduced, are characterized by an extreme distrust of state intervention in markets, a distaste for statistical modeling and a general confidence that markets, left to their own devices, will avoid booms and busts and nasty things like inflation. From a political perspective, Austrian economics tends to lurk to the right of even such conservative icons as Milton Friedman.

For more detail, you can go, of course, to the Wikipedia page for Austrian economics. But until at least Feb. 28, if you do so, you will find that the page “is currently protected from editing.” An “edit war” has been raging behind the scenes. Two factions were repeatedly deleting and replacing a section of text that had to do with a description of a critique of Austrian economics made by economist Paul Krugman.

The closer you look, the more the whole affair appears at first to be a demonstration ofSayre’s Law, which holds that “in any dispute the intensity of feeling is inversely proportional to the value of the issues at stake.” One side, which seems from the Talk page chronicling the argument to be just one very stubborn person, is objecting to the inclusion of Krugman’s critique on the grounds that what Krugman describes as Austrian economics doesn’t actually represent the reality of Austrian economics. In other words, it’s as if Krugman was saying “the problem with blue is that it is red.” Therefore, his views should not be included as an example of a valid critique. The other side is basically saying that Krugman is Nobel Prize-winning economist whose opinion is well worth including according to the standards of Wikipedia. So there. And back and forth the argument went, with lots of torturous discursions into the process weeds of Wikipedia editing policies, until it got too heated and provoked a lockdown.

30 October 2013

The Nobel Prize and the reproduction of economics orthodoxy

This year’s economics laureates reflect the narrow purview of the prize and the entrenchment of familiar but limited ways of thinking about economic life

It is reasonably well known that the Nobel Prize in Economics is not a real Nobel Prize, being funded not by the original legacy but by the Swedish central bank. Yet only real sticklers for detail ever bother to spell out the full name: the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The popular name of the Nobel Prize in Economics usually suffices.

However, all the evidence suggests that the Nobel Committee takes very seriously the difference between the ‘Economics’ of the popular name and the ‘Economic Sciences’ of the actual name. As a consequence, the most likely recipients are not those whose flashes of insight have done most to challenge conventional wisdoms, nor those whose work has added cumulatively to the stock of knowledge about how the economy is experienced in everyday life. They are much more likely to be those people who have set down footsteps in which other economists have followed. The Sveriges Riksbank Prize is therefore a means of signalling the power of orthodoxy within economics.

The whole notion of being involved in a genuinely scientific endeavour is an extremely important aspect of what economists think that they do. Professional self-image, self-esteem and self-assurance are all intimately bound to this view. But it is a curious conception of science – one that routinely draws criticism from methodologists of the discipline for the way in which it sidesteps proper empirical testing of models in favour of selective data-fitting approaches. The econometric models used in this way suit only the type of quasi-experimental data that is unavailable in relation to the social world.

The decisions of the Nobel Committee have upheld this conception of economic science and continue to bestow legitimacy on the worldview it sustains.

The appeal to economic science separates the allegedly ‘serious’ economist from everyone else who might want to comment on matters relating to the economy. Very little has changed in this respect since 1932, when Lionel Robbins first popularised the capitalisation of the ‘E’ and the ‘S’ in his hugely influential Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. Robbins used this book to delineate not only what economists should be studying, but also how they should be studying it.

He narrowed the supposedly authoritative remit of economic science to choice problems, highlighting the conditions under which an abstract individual enters an equally abstract market environment to manage their relationship with the contextual factor of scarcity. Every other aspect of everyday economic life was exiled from economic science and forcibly located into some other area of study.

The Robbins definition of ‘choice amidst scarcity’ had elbowed aside all other potential definitions of the scope of economics by the 1960s. It is what today’s Nobel laureates learnt was economics when they were students; what their prize-winning acceptance speeches reaffirm is stilleconomics today; what they teach their own students as the way to practise economic science; and what anyone who follows in their post-Nobel footsteps will assume counts as the outer limits of the subject field. The Robbins definition continues to provide economists with the inbuilt assumption that market institutions will always be best at offering relief from scarcity constraints, and the decisions of the Nobel Committee continue to place this vision of the subject field on a pedestal.

And what of this year’s winners announced in mid-October: Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Robert Shiller? They were awarded the prize ‘for their empirical analysis of asset prices’.

Hansen was honoured for his econometric work, in particular for devising a method that allows asset pricing to be understood in its own terms, unaffected by macroeconomic influences. The surrounding context of the consumption-fuelled credit bubble experienced before 2007, say, or the protracted financial crisis that has followed since that time, do not therefore have to intervene in the serious economics study of asset price fundamentals and their relationship to the market environment.

Shiller, by contrast – feted in the broadsheet press at the time of the Nobel Committee’s announcement for his supposedly radical rejection of orthodox market logic – was honoured for his work in behavioural economics which suggests that things are more complicated than the search for fundamental prices alone. Humans, he has shown, do not always behave in the way predicted by market theory. Nevertheless, in his most recent book he still makes the case for re-empowering financial innovators to make from scratch new markets in the image of that theory if the lingering crisis tendencies are ever to be fully resolved.

Fama is likely to prove the most controversial selection, having been widely tipped but then overlooked for the award last year. He has been honoured for his work establishing the efficient markets hypothesis: the view that financial markets are best governed unencumbered by external regulation, because in that state financial prices always reflect all relevant information. Yet the efficient markets hypothesis has been loudly denounced in the wake of the global financial crisis, which has exposed it as an exceptionally poor template for how to construct real-life markets.

The Nobel Committee has trumpeted its decisions as an indication of the breadth of economics opinion. It is certainly true that disagreement would ensue if the three new laureates – all exceptionally capable scholars at the forefront of what they do – were to be placed in the same room and asked to debate just how closely actual financial markets correspond to the teachings of basic market theory. However, the belief that this represents breadth is itself a prime example of the narrowness of economics and of how the Nobel Prize reinforces that narrowness around a specific conception of orthodoxy.

Why must it be that the experience of everyday economic life necessarily maps onto the market form? And why must it be that economics limits itself to descriptions of this elision?

A genuinely broad-based economics should be able to discuss alternatives to the simplified market abstraction just as readily as that abstraction itself. That it cannot but still clings to the notion of ‘serious’ science is a cause for regret. That the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences now only ever honours people whose worldview is deeply influenced by the market abstraction is likewise an issue for lament. The truth is that the Nobel Committee repeatedly acts in the interests of reproducing an orthodoxy that limits what economists can be expected to say about the world in which they live.

August 23, 2013

How socialists and Keynesians use their Nobel prize as a weapon of mass destruction

The economics Nobel prize is not a "real" Nobel prize but a NobelMEMORIAL prize. Unlike the original Nobel prizes, the economics prize is given by the Sweden's central bank in the memory of Nobel. This is not a major issue, though. The real issue is that in economics, the Committee has picked a NUMBER of undeserving economists.

Arvind Panagariya recently narrated the Jagdish Bhagwati frustration with the socialist and interventionist policy prescriptions of Joseph Stiglitz:

"In one debate, Jagdish Bhagwati went in and told him, Joe, don't use your Nobel prize as a weapon of mass destruction."

Unlike evil dictators like Hitler who directly kill, the ideas and theories of bad economists can end up indirectly killing ten times millions – through bad policy prescriptions. No one has killed more people (through bad ideas) than Karl Marx. In BFN I argue that Nehru was responsible for the loss of millions of lives and shortening of the lives of millions more due to his socialist policies.

Similarly, a number of "Nobelists" in economics have used the platform accorded to them by their "Nobel" to promote the destructive socialist/Keynesian policies.

In the case of India, Amartya Sen should be signed out for using his Nobel as a weapon of mass destruction against the poor people of India.

But the list of bad Nobelists should include others as well, such as Paul Samuelson (for his Keynesian indoctrination of millions of economics students for five decades) and Paul Krugman. Such "economists" don't understand that it is impossible for bureaucrats and politicians to spend our money better than we can do ourselves. Their economics is pseudo-economics.

I do not intend to imply that there were no contributions made by such economists. Far from that. I value their technical contributions. But they were NOT economists. An economist is not just a technician.

Unlike the physical sciences in which the number of citations is a meaningful indicator of quality, in economics more basic questions need to be asked:

- Does this economist recommend government intervention in business, 'fine-tuning' of the economy or big government?

- Does he understand the price system and the way investors actually think?

- Does he understand basic cost-benefit analysis?

If the economist fails the above questions or displays a belief that bureaucrats can second guess our choices as citizens, he should NEVER be eligible to receive the prize. Just because bad economics is widely prevalent and 'cited', doesn't mean these people deserve any 'prize'.

Fortunately, the committee did redeem itself by awarding the prize to really sensible economists as well, such as FA Hayek, Milton Friedman and James Buchanan. Many other good economists have not yet received a prize, such as Harold Demsetz, Deirdre Mccloskey or Jagdish Bhagwati.

The key message here is: DO NOT TRUST IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN ECONOMICS. Use your own analysis and judgement to distinguish good from the bad.

THOMAS PIKETTY: C’EST SA MÈRE UN HAMSTER?

The macro-economists are being bitchy again over the Golden Globe.

Chris Giles from the Financial Times, Federico Sturzenegger and Ricardo Hausmann [Harvard] and Per Krusell [Stockholm University] with Tony Smith [Yale], have got stuck into the recent mega-tome ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’ by French Economist Thomas Piketty, basically concluding that it is a shonky-wonky block-buster.

On the other hand, Tom has received a glowing accolade from Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, who commented with respect to detractors of Tom’s thesis:

"Anyone imagining that the whole notion of rising wealth inequality has been refuted is almost surely going to be disappointed".

And as Paul himself has commented enigmatically: 'Saying “Professor X has made basic errors” is not at all the same thing as saying that his mother was a hamster'.

And as Paul himself has commented enigmatically: 'Saying “Professor X has made basic errors” is not at all the same thing as saying that his mother was a hamster'.

As for me, I am not keen on time series Econometrics. Many of these exercises marshal, calibrate and cross-reference reams of historic statistics, folding away their attendant gaps, inconsistencies and systemic weaknesses. It is hardly surprising then that Piketty’s critics don’t like his data and don’t like what he has done with it.

But there is a much more basic flaw in time series analysis of this type – it assumes that you can swim in the same river twice – or more particularly that if you have identified statistics for something called the United Kingdom in 1913, these can be directly compared with those of the modern entity bearing the same name.

In the latter case, comparisons have to proceed regardless that the country accumulated massive overseas debts and incurred enormous losses of physical and human capital in two World Wars, whilst losing an empire that spanned the world.

Have a look at the following tables [data drawn from Maddison et al]:

Populations of Key Countries in Piketty’s Thesis [millions]

Country | 1913 | 1998 |

Australia | 4.821 | 18.751 |

New Zealand | 1.122 | 3.811 |

Canada | 7.852 | 30.297 |

USA | 97.606 | 270.561 |

UK | 45.649 | 59.237 |

Sweden | 5.621 | 8.851 |

GDP per capita of Key Countries [Geary-Khamis 1990 $]

Country | 1913 | 1998 |

Australia | 5,715 | 20,390 |

New Zealand | 5,512 | 14,779 |

Canada | 4,447 | 20,559 |

USA | 5,301 | 27,331 |

UK | 4,921 | 18,714 |

Sweden | 3,096 | 18.685 |

In the period in question, Sweden is the only ‘normal’ country, in that it in that it had long closed its frontier of settlement and that it passed through the period without any major wars. Its population grew by 60 percent. In the same period, Canada’s population rose by a multiple of 3.86 and Australia’s by a multiple of 3.89.

And New Zealand’s population has remained under 1.5 percent of that of the USA over the entire period.

And New Zealand’s population has remained under 1.5 percent of that of the USA over the entire period.

Clearly size matters with respect to GDP in Advanced Economies. In the case of the USA its population provides a vast internal market but when a country is small and dependent on externally-determined terms of trade, as in the case of New Zealand, growth is much more problematic.

As a very ‘micro’ transport economist, I worry that this kind of analysis is like trying to formulate and prove a law linking investment in public and private transport to the value of time savings, using data from a motley sample of settlements that covers villages and large cities over the period 1910-2010, taking in horse manure collection at one end and electric self-drive cars at the other – without any consideration of context or hierarchy.

Of course this does not mean that Piketty’s conclusions are necessarily wrong. Though it is a big stretch to build and prove an Economic Law out of the data rubble.

As ‘SH’ in The Economist has recently explained:

‘Mr Piketty defines his second fundamental law of capitalism as β = s/g, where β is the ratio of national capital to national income, s indicates the savings rate net of depreciation and g denotes the growth rate of the economy. For example, if the savings rate is 6% and the economy grows by 2% every year, the country is predicted to, in the long run, accumulate a stock of wealth which approaches 300% of GDP.

‘Employing his law, Mr Piketty predicts that the future world capital/income ratio will increase and approach 600% in less than fifty years. Since capital tends to be unequally distributed, this implies higher inequality. This forecast is based on two assumptions: that global growth will fall from 3% per year today to 1.5% in the second half of the century and that the global savings rate will stabilise at 10%.

‘The second assumption is what troubles Messrs Krusell and Smith. While they do not dispute the risk of falling growth, they take issue with the notion that the future savings rate will be constant at around 10%’.

Well, there are lots of other factors that may also influence the outcome in 2064. I seem to remember, for example, that the Bolsheviks abolished private property in Russia at one point in the 1920s. This is another perennial problem with economists like Piketty, they abstract their analyses from politics - on an ‘other things being equal basis’. In fact as we all know from real life, generally ‘other things are unequal’.

And The Economist seems to take my drift on generalization and the need for qualitative judgments rather than quantitative ‘proofs’, in its conclusion that:

‘The latest critique against the French economist’s magnum opus notwithstanding, inequality may still rise rapidly in the future. But rather than by the quotient of the net savings rate over the growth rate, future inequality could be driven by an increasingly unequal distribution of income.

‘Both demographic shifts and technological progress, for example, could favour the well-educated over the less-skilled, causing a much greater concentration of economic resources. Mr Piketty may therefore turn out to be right in predicting increasing economic inequality, but it does not have to be because of the implications of his second 'fundamental' law of capitalism’.

THE GETs AND THE OUTs

The article in the Economist hints at the real drivers of increasing income and wealth inequality in the modern world – in terms of the endemic skewing of economic opportunities towards the ‘haves’ and away from the ‘have-nots’, from whom even that which they have may be taken away.

As you see from my graphs, the top 0.1% [i.e. the top 1 in 1,000] earners do pretty well in income terms - and are accruing wealth hand over fist.

In this Web magazine, I have characterized the uneven tussle as one between the GETs [‘Gone-tomorrow Elite Transnationals’] and the OUTs [‘Old Underclass Traditionals’] and marked its primary drivers as: the growth of World Cities through accelerating urban agglomeration; the economic dominance of tradable activities that involve cross-border exchanges of highly valued services and innovation-laden goods; and an increasing tendency towards oligarchy in which the few manipulate the playing field, screw the game and spin the many spectators in collusion with Establishment politicians.

This is a hierarchy game in which the gradients of economic rent that support ‘hives of innovation and idea-exchange’ become ever steeper and, as they become more concentrated, more open to capture and subversion by the super-rich who are in the right place at the right time.

I am not at all surprised that someone will snap up a single room home in London for a rent of £170 per week where you have to cook off the top of the bed and sleep with your head on the sink bench. Even 40 years ago, the ground rent of the space taken by the Emperor’s camphor chest in the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth more than the combined rateable values of Rawtenstall or the local tax base of Waukegan.

When I started work on this article, I wanted to write something that had specific resonance to the situations that we find ourselves in Australia and New Zealand. And as you can see, I produced some graphs of my own which include NZ. Unfortunately, New Zealand's recent data on income and wealth inequality are incomplete. [The first of the three graphs above is from Piketty's technical appendix, and my graphs use the associated data that the provides.]

And the exercise turned out to be a bit of a waste of time anyway because there is a comprehensive assessment in a paper that is available online with the title ‘The Income Distribution of Top Incomes in Five Anglo-Saxon Countries Over the Long Run’, by A.B. Atkinson and Andrew Leigh [Economic Record 2013].

This article is not afraid to bring in considerations of political economy and it concludes that:

‘... top income shares are highly correlated across Anglo-Saxon Countries. The share of the very rich appears to be extremely responsive to changes in marginal tax rates. Over the period 1970-2000, we estimate that reductions in tax rates can explain between one third and one half of the rise in the income share of the richest percentile group’.

So What Happened in the period 1979-89 that made such a big difference?

Well, you can note, for example, that:

- Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980

- Margaret Thatcher was elected 1979

- The Washington Consensus was promulgated in 1989.

And regardless of whether or not Tom is a Wonder Pet, who is spinning his wheel and whose Mum is a hamster, one has some sympathies with his policy prescriptions which include a progressive global tax on capital (an annual levy that could start at 0.1% and hits a maximum of perhaps 10% on the greatest fortunes) – and a punitive 80% tax rate on incomes above $500,000 or so.

But the policy recommendations are fanciful. Believe me they won’t get past the seed tray or up the ladder to the toilet roll tunnel. The best we can do is work towards reducing tax relief to the levels evident in the 1960s [as you can see this will make diddly swat difference to growth rates], improving international cooperation on taxation avoidance - and making sure as hell that we don’t let the Establishment Oligarchies get a firmer grip.

As Primo Levi said:

“It is our duty to make war on all undeserved privilege, but one must not forget that this is a war without end”.

SEE ALSO [for example]:

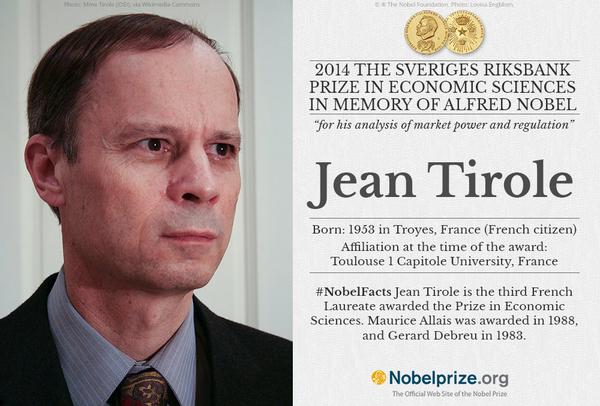

Jean Tirole wins Nobel prize for economics 2014

French economics professor wins for his work on market power and regulation, and his work taming powerful firms

• Jean Tirole wins – live analysis and reaction

• Nobel prizes 2014 – the winners

• Analysis: Why Tirole’s work matters in the Age of Google

• Jean Tirole wins – live analysis and reaction

• Nobel prizes 2014 – the winners

• Analysis: Why Tirole’s work matters in the Age of Google

A French economist who has been working since the 1980s on ways to curb the dominance of major companies has won the Nobel prize for economics.

Praising Jean Tirole’s attempts to “tame powerful firms”, the committee awarding the 8m kronor (£750,000) prize said the University of Toulouse professor was “one of the most influential economists of our time”. The committee chose an area of economics that has become increasingly important as governments have privatised former public monopolies such as water, electricity and telecoms and Tirole’s work has been adopted by competition regulators around the world.

Tirole, 61, has covered a wide range of areas including pay, the banking industry and credit card fees. In a paper last year he scrutinised, with Roland Bénabou, a “bonus culture that takes over the workplace, generating distorted decisions and significant efficiency losses, particularly in the long run”.

He is known for his collaboration with the late Jean-Jacques Laffont. After winning the award, Tirole described Laffont, who died 10 years ago, as “my mentor and dear friend” and said his former colleague “probably would have deserved to be with me today in this prize for regulation and competition policy”.

The judges said: “[Tirole] has made important theoretical research contributions in a number of areas, but most of all he has clarified how to understand and regulate industries with a few powerful firms.” The panel said Tirole had shown the “deep and essential differences” between regulating companies in different sectors, such as telecoms companies or banks. Imposing caps on prices could reduce the influence of monopolies in some sectors, but not in others, the judges said, pointing to Tirole’s use of game theory and contract theory to develop competition analysis.

Announcing the winner, Staffan Normark, permanent secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said: “This year’s prize in economic sciences is about taming powerful firms”.

Joaquín Almunia, the EU commissioner in charge of competition policy, said Tirole’s work “has been central to the economic analysis underpinning many of our instruments in competition policy and beyond”. The economics award is technically in the name of the Swedish central bank in the memory of Alfred Nobel, as the field was not stipulated as one of the five areas for awards by the Swedish inventor of dynamite, who set up the Nobel prizes in his will.

After receiving the award, Tirole took questions on topics including Google and the banking sector, welcoming attempts to create a banking union in the eurozone but acknowledging banking was hard to regulate. He said: “Banking is a very hard thing to regulate and we economists, academics, have to do more work on this.”

Tirole said he felt proud but added: “It’s also being with the right people, in the right place, at the right moment. And, you know, it’s team work too.” He told his 90-year-old mother, who used to teach French, Latin and Greek, to sit down before telling her the news.

Economists said his selection was not controversial. “Most people thought he’d get it at some point,” said Mark Armstrong, professor at All Souls College, Oxford. Armstrong described Tirole as “a theorist, but someone who’s very much interested in real-world problems”.

Referring to Tirole’s work with Laffont, Armstrong said: “While much regulation of monopolies used simple schemes such as rate of return regulation and price cap regulation, their contribution was to show how to move beyond these to forms of regulation which were more sensitive to the details of the market, including the scope to introduce competition into monopoly markets.”

Oxford University economics professor Paul Klemperer told Reuters: “He has been the dominant figure in industrial organisation. It was not a question of whether but when he would be awarded the prize. “It has given us understanding of how to think about regulating firms, that there is not one size fits all.”

However, David Blanchflower of Dartmouth Colleague in the US tweeted “about time the Nobel (economics) committee started to award prizes to people who discover empirical facts about how the world works”.

Tirole is the second Frenchman to win a Nobel prize this year – Patrick Modiano won the literature award – which prompted Manuel Valls, the French prime minister, to tweet: “After Patrick Modiano, another Frenchman in the stars: congratulations to Jean Tirole. It makes a mockery of French-bashing”.

It is 25 years since a French economist last received the award, which was first handed out in 1969. It has been won by 74 individuals, some of whom have become familiar names, such as Joseph Stiglitz – with whom Tirole has worked in the past – James Tobin and Milton Friedman.

Only one woman has ever won, Elinor Ostrom, in 2009. The last French economist to win was Maurice Allais.

Last year, the prize went to three economists, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen and Robert Shiller for their work on predictions in financial markets.

| ||||

| ||||