The cultural trait of Seva is what is imbibed by a Swayamsevak trained by RSS. It is time that journalists like Rupa Subramanya understand this phenomenon in the context of Indian tradition without having to import some Good Samaritan Law. Law is an ass. Culture is the kamadhenu, Rupa ji. Respect that kamadhenu which has been our sustenance for generations and we seem to have lapsed into amnesia.

Kalyanaraman

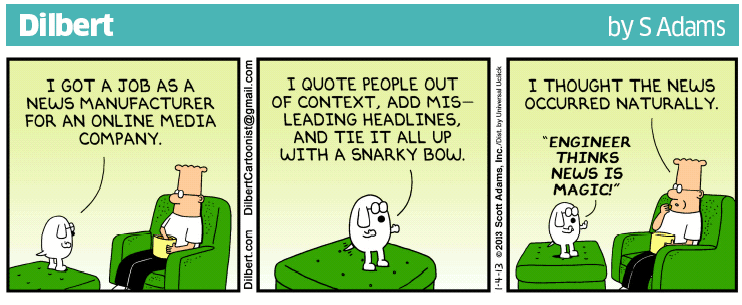

This cartoon is apt for this thread. Do not engineer convoluted law when spontaneous cultural response is the answer.

This cartoon is apt for this thread. Do not engineer convoluted law when spontaneous cultural response is the answer.k

Delhi Rape: Why Did No One Help?

By Rupa Subramanya

![]()

- Indranil Mukherjee/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

- From biology, we know that altruism — whether among humans or in the animal kingdom — is a fragile commodity, says Rupa Subramanya.

In an exclusive interview to Zee, a Hindi news channel, the male companion of the young woman who was gang-raped then succumbed to her injuries detailed what happened on that fateful night.He himself was badly beaten up during the attack, allegedly by the men charged in court Thursday. But the man, who has been previously identified as a 28-year-old software engineer, came out alive. I watched the interview in Hindi.

I was struck, as others were, that a recurring theme in his remarks was the apparent apathy of passersby and of the authorities. He describes in shocking detail how he and the young woman were brutally beaten, stripped of their clothes and possessions and thrown off the bus, the young woman bleeding profusely.

The English transcript of his comments includes statements such as:

“We tried to stop passersby. Several auto rickshaws, cars and bikes slowed down but no-one stopped for about 25 minutes. Then, someone on patrol stopped and called the police.”

“Nobody from the public helped us.”

He added poignantly: “If a single person had helped me that night, things would have been different.”

Predictably, the cries of cultural self-flagellation from many Indians, including well-known commentators, has begun.

Here are two representative examples. First from media personality Sagarika Ghose who wrote on Twitter: “We can change laws, but what about shocking apathy that not a single passer-by helps/cover a girl without clothes, bleeding in bitter cold.”

And from former senior police officer turned social activist Kiran Bedi: “Statement on Zee of the friend of brave heart has clearly exposed how we as a society have lost all humanity.”

We will see op-eds and TV commentaries fleshing out the idea that somehow Indians are just apathetic and uncaring in the face of such tragedies. I’ll also bet that you’ll be hearing about the “bystander effect,” whereby group psychology purportedly explains why people don’t step into help.

Without in any way detracting from this most recent tragedy and the understandable emotions in the reactions to it, let’s remember that we’ve seen this movie before.

In late 2011, in Mumbai, there was another high-profile case in which two young men, Keenan Santos and Reuben Fernandes, lay dying on the street while passersby did nothing to help. They both subsequently died. In the aftermath of the tragedy, Mr. Santos’s friend, Priyanka Fernandes, who was present at the scene, said: “When my friends Keenan and Reuben were being stabbed repeatedly, mercilessly, I could see at least 50 eyewitnesses who stood like stone, unmoving and unmoved, as we screamed for help. Not one came forward to join the fray, to help us fight against a reprehensible crime.”

In the aftermath, there were many who suggested that the apparent apathy of the passersby was a feature of contemporary Indian culture and represented a breakdown of traditional morals and values.Do such explanations, of either the Mumbai or Delhi tragedies, make sense?

I would suggest not.

In our recent book, “Indianomix: Making Sense of Modern India,” Vivek Dehejia, an economics professor, and I explored the Mumbai tragedy in considerable detail, looking also at a contemporary episode in China where a toddler lay dying on the street and no-one came forward to help. Our analysis in the book is equally applicable to the apparent apathy noted by the young man in Delhi.

We argue that, far from being a cultural phenomenon, basic economic concepts such as incentives, and a sophisticated understanding of altruistic behaviour coming out of evolutionary biology, can help explain why these things happen.

From biology, we know that altruism — whether among humans or in the animal kingdom — is a fragile commodity. Whatever altruistic tendencies are latent in human beings contend with the equally powerful human instinct of self-preservation. To put that in more concrete terms, any would-be “savior,” driven by an altruistic impulse, will weigh the benefit in helping someone in need against the costs to themselves.

The crux is here that the “cost” is often not a strictly economic or financial cost. Rather it represents in part the opportunity cost of time and the more direct costs that would be incurred for someone who did get involved and then would need to spend hours, days, perhaps even weeks entangled with the authorities. We document in the book cases in India and China where would-be Good Samaritans have ended up being harassed by the police, wrongly accused themselves of being the perpetrators, and, in some cases even being accused by the victims whom they’re trying to help. To put it bluntly, most people just don’t trust the authorities and aren’t willing to take the risk of getting mixed up with them for fear of any or all of these things happening.It’s not necessarily that they don’t want to help, or somehow apathy is hardwired into Indian culture, but people’s desire to help is overwhelmed understandably by their reluctance to suffer unnecessarily as a result of helping.

A crucial missing link in India compared to many Western countries is the absence of a Good Samaritan Law. Such a law protects those who help others in need from frivolous civil litigation or criminal prosecution except in cases of gross negligence. Civil law jurisdictions such as Europe or the Canadian province of Quebec have something similar whereby the law mandates a “duty to rescue,” which has a similar intention.

In the book, we speak to Piyush Tewari, who has created the “Save Life Foundation,” a Delhi-based NGO with a mission to overcome people’s natural reluctance to get involved and help victims of roadside accidents.

Mr. Tewari was inspired to create the NGO after his young nephew bled to death while passersby did nothing to intervene. The key to Mr. Tewari’s approach, which has been tested as a pilot project both in Delhi and rural Maharashtra, is to mobilize volunteers who’ve been vetted both by his organization and by the local authorities.

He and his team painstakingly train the volunteers in the basics of first aid and rescue and verify their bona fides. (This is very different from simply compiling a directory of people who’ve offered to help without vetting them, something I’ve previously criticized) This greatly reduces the possibility that they’ll face harassment if they come to the rescue.

Mr. Tewari strongly believes that India needs some version of a Good Samaritan law if there’s going to be any major improvement in people’s reluctance to help.

Mr. Tewari told me that the apparent apathy of passersby in the Delhi case, “is a clear example of the deep fear of police harassment and legalities that reside in people’s minds in India.”

He wondered ruefully whether the outcome of that night would have been different if the victims had been rushed immediately to the nearest emergency room by a helper on the scene. He concluded: “Deterrents must be removed or they will continue to overpower any sense of empathy that our society may have — be it cases like the Delhi gangrape or the murder of Keenan and Reuben in Mumbai”.

Indeed, if one looks carefully at the transcript of the young man’s comments, it’s remarkable that even in his current state of physical and emotional shock, rather than resorting to cliche, he shows a clear-headed understanding of why people didn’t help:

“People were probably afraid that if they helped us, they would become witnesses to the crime and would be asked to come to the police station and court.”

As many readers will know, in the aftermath of the Delhi tragedy, the government has set up the Verma Commission to report on how rape laws may be strengthend and judicial procedures improved to ensure that rapists are brought to justice and to help prevent such tragedies in the future. Few will likely know that the Supreme Court has set up an expert group chaired by V.S. Aggarwal, former justice of the Delhi High Court, to investigate whether India needs something like a Good Samaritan law. Mr. Tewari is part of the group.

At least two tragedies occurred in Delhi on Dec. 16. The first was what happened to those two young people on the bus. The second tragedy is that it took them so long to make it to a hospital, vital minutes which might perhaps have saved the young woman’s life.The young man himself has said that the need of the hour is not to light candles but to change mindsets: “You have to help people on the road when they need help.”

Indeed, lighting candles and decrying our apparent apathy aren’t going to change mindsets.

What’s needed is an understanding of how the deck is stacked against those who try to help and changing those odds by getting a Good Samaritan law in place and improving the creaky and dysfunctional response to crime.

Rupa Subramanya writes Economics Journal for India Real Time and is co-author of “Indianomix: Making Sense of Modern India,” published by Random House India. You can follow her on Twitter @RupaSubramanya.

http://blogs.wsj.com/indiarealtime/2013/01/05/delhi-rape-why-did-no-one-help/