Background

Cire perdue or lost-wax casting metallurgy spread from Meluhha into the Fertile Crescent (Nahal Mishmar). See: html http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html

Tin Road stretched from Meluhha in the east into the Fertile Crescent (Kultepe, Anatolia) defining the Bronze Age. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-and-tracking-tin-road-after-all.

Dhokra kamar as a Meluhha hieroglyph: Dholavira, Mohenjo-daro seals Rebus: lost-wax casting

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet with Meluhha hieroglyphs written on two sides. Hieroglyph: Ku. ḍokro, ḍokhro ʻ old man ʼ; B. ḍokrā ʻ old, decrepit ʼ, Or. ḍokarā; H. ḍokrā ʻ decrepit ʼ; G. ḍokɔ m. ʻ penis ʼ, ḍokrɔ m. ʻ old man ʼ, M. ḍokrā m. -- Kho. (Lor.) duk ʻ hunched up, hump of camel ʼ; K. ḍọ̆ku ʻ humpbacked ʼ perh. < *ḍōkka -- 2. Or. dhokaṛa ʻ decrepit, hanging down (of breasts) ʼ.(CDIAL 5567). M. ḍhẽg n. ʻ groin ʼ, ḍhẽgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. M. dhõgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. (CDIAL 5585). Glyph: Br. kōnḍō on all fours, bent double. (DEDR 204a) Rebus: kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner’s lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295) Tiger has head turned backwards. క్రమ్మర krammara. adv. క్రమ్మరిల్లు or క్రమరబడు Same as క్రమ్మరు (Telugu). Rebus: krəm backʼ(Kho.)(CDIAL 3145) karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-evidence-for-mleccha.htmlAncient Near East evidence for meluhha language and bronze-age metalware

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html?q=dhokraMeluhha: spread of lost-wax casting in the Fertile Crescent. Smithy is the temple. Veneration of ancestors.

The hieroglyph of an old female with breasts hanging down and ligatured to the buttock of a bovine is also deployed on a Mohenjo-daro seal:

Mohenodaro seal. Pict-103 Horned (female with breasts hanging down?) person with a tail and bovine legs standing near a tree fisting a horned tiger rearing on its hindlegs.

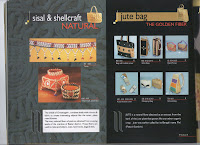

Hieroglyph: N. dhokro ʻ large jute bag ʼ, B. dhokaṛ; Or. dhokaṛa ʻ cloth bag ʼ; Bi. dhŏkrā ʻ jute bag ʼ; Mth. dhokṛā ʻ bag, vessel, receptacle ʼ; H. dhukṛīf. ʻ small bag ʼ; G. dhokṛũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- ṭṭ -- : M. dhokṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ; -- with -- n -- : G. dhokṇũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- s -- : N. (Tarai) dhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in ʼ.2. L. dhohẽ (pl. dhūhī˜) m. ʻ large thatched shed ʼ.3. M. dhõgḍā m. ʻ coarse cloth ʼ, dhõgṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ.4. L. ḍhok f. ʻ hut in the fields ʼ; Ku. ḍhwākā m. pl. ʻ gates of a city or market ʼ; N. ḍhokā (pl. of *ḍhoko) ʻ door ʼ; -- OMarw. ḍhokaro m. ʻ basket ʼ; -- N.ḍhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in, large basket ʼ.(CDIAL 6880) Rebus: dhokra ‘cire perdue’ casting metalsmith.

Plate II. Chlorite artifacts referred to as 'handbags' f-g (w 24 cm, thks 4.8 cm.); h (w 19.5 cm, h 19.4 cm, thks 4 cm); j (2 28 cm; h 24 cm, thks 3 cm); k (w 18.5, h 18.3, thks 3.2) Jiroft IV. Iconography of chlorite artifacts. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts

Mohenjo-daro, ancient Indus Valley Civilization, Dancing Girl in Pakistan

Published on May 22, 2012

Mohenjo-daro (Mound of the Dead), is an archeological site situated in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. Built around 2600 BC, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. It is in UNESCO World Heritage List. This video is from Pakistan National Art Gallery. They permorformed this dance for Turkish Culture and Tourism delegation

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR_oMwDr4Gs

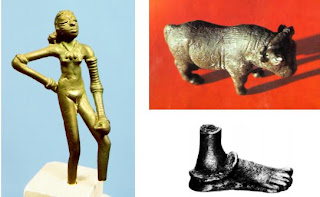

Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

Dance-step of Mohenjodaro as a hieroglyph. Rebus: metal, 'iron'

Dance-stepas hieroglyph on a potsherd, Bhirrana.

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ‘iron’(Munda); मेढ meḍh‘merchant’s helper’(Pkt.) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)

![]()

The ‘Dancing Girl’ (Mohenjo-daro), made by the lost-wax process; a bronze foot and anklet from Mohenjo-daro; and a bronze figurine of a bull (Kalibangan). (Courtesy: ASI) "Archaeological excavations have shown that Harappan metal smiths obtained copper ore (either directly or through local communities) from the Aravalli hills, Baluchistan or beyond. They soon discovered that adding tin to copper produced bronze, a metal harder than copper yet easier to cast, and also more resistant to corrosion.

Whether deliberately added or already present in the ore, various ‘impurities’ (such as nickel, arsenic or lead) enabled the Harappans to harden bronze further, to the point where bronze chisels could be used to dress stones! The alloying ranges have been found to be 1%–12% in tin, 1%–7% in arsenic, 1%–9% in nickel and 1%–32% in lead. Shaping copper or bronze involved techniques of fabrication such as forging, sinking, raising, cold work, annealing, riveting, lapping and joining. Among the metal artefacts produced by the Harappans, let us mention spearheads, arrowheads, axes, chisels, sickles, blades (for knives as well as razors), needles, hooks, and vessels such as jars, pots and pans, besides objects of toiletry such as bronze mirrors; those were slightly oval, with their face raised, and one side was highly polished. The Harappan craftsmen also invented the true saw, with teeth and the adjoining part of the blade set alternatively from side to side, a type of saw unknown elsewhere until Roman times. Besides, many bronze figurines or humans (the well-known ‘Dancing Girl’, for instance) and animals (rams, deer, bulls...) have been unearthed from Harappan sites. Those figurines were cast by the lost-wax process: the initial model was made of wax, then thickly coated with clay; once fired (which caused the wax to melt away or be ‘lost’), the clay hardened into a mould, into which molten bronze was later poured. Harappans also used gold and silver (as well as their joint alloy, electrum) to produce a wide variety of ornaments such as pendants, bangles, beads, rings or necklace parts, which were usually found hidden away in hoards such as ceramic or bronze pots. While gold was probably panned from the Indus waters, silver was perhaps extracted from galena, or native lead sulphide...While the Indus civilization belonged to the Bronze Age, its successor, the Ganges civilization, which emerged in the first millennium BCE, belonged to the Iron Age. But recent excavations in central parts of the Ganges valley and in the eastern Vindhya hills have shown that iron was produced there possibly as early as in 1800 BCE. Its use appears to have become widespread from about 1000 BCE, and we find in late Vedic texts mentions of a ‘dark metal’ (krṣnāyas), while earliest texts (such as the Rig-Veda) only spoke of ayas, which, it is now accepted, referred to copper or bronze.

Note:

Damaged circular clay furnace, comprising iron slag and tuyeres and other waste materials stuck with its body, exposed at lohsanwa mound, Period II, Malhar, Dist. Chandauli. http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/iron-ore.html

Uploaded on Oct 7, 2010

Meluhha: the Indus Civilization and Its Contacts with Mesopotamia

Mark Kenoyer, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Meluhha -- the name for the Indus civilization found in Mesopotamian texts -- was an important source of exotic goods, many of which are preserved in the archaeological record of Mesopotamia. The movement of people and goods between these two regions established a pattern of interaction that continued in later periods and is still seen today. This lecture presents an overview of the Indus civilization and its contact with the Mesopotamia during the forth to second millennia BCE.

Indus valley civilization(mohenjo-daro)

Uploaded on Apr 1, 2008

©http://www.hexolabs.com

e-learning research on ancient Indian civilization produced at Hexolabs,SIIC, IIT Kanpur for a better insight, visit

Kindly do not treat this video clipping as an exact archaeological reference. The idea is to make children aware/understand the whole Indus valley cultural system.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SdGbamPgf8o&list=PL01A404D5E75BB79C

The Indus Valley Civilisation of India and Pakistan (Video 52:19)

Published on May 11, 2013 (Prof. RS Bisht, Dr. KS Nauriyal, Dr. Walid Yasin, and Dr. khaled Alsendi as tour guides of Dholavira, a stretch of River Sarasvati, links with Mesopotamia)

DISCLAIMER: THIS VIDEO HAS BEEN POSTED FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND/OR EDUCATIONAL VALUE ONLY!

This channel is katy665412's alt. channel, created because katy665412 is unable to upload anymore videos due to copyright notices.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dIZWnwI47M

Glyph: araṇe 'lizard' (Tulu) Rebus: eraṇi f. ʻ anvil ʼ (Gujarati); aheraṇ, ahiraṇ, airaṇ, airṇī, haraṇ f. ‘anvil’(Marathi)

![]()

![]()

![]()

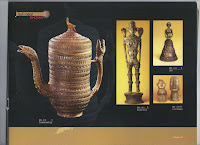

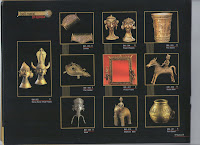

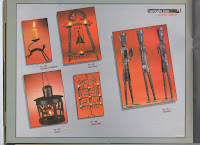

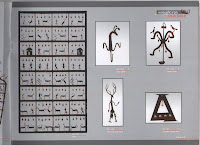

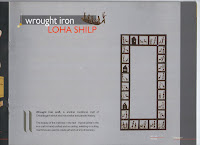

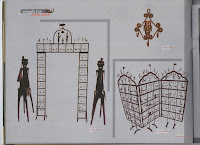

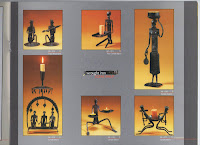

Dhokra, the tradition of making lost wax cast ritualistic and utility objects is a finely developed art of Chhattisgarh, with a large concentration of craftspersons in Bastar region. However this evolved art is practiced in many places extending from Orissa to West Bengal.

The process involves many stages: making of the core in fine sand and clay; making an armature with wax threads and strips that depict the image; encasing it with a clay mould with vents and inlet; pouring molten brass and casting; removing the cast, finishing and polishing with sandpaper. In Bastar, the Gharuas use wax for metal casting the idols, which they install in the devgudi, village shrine, of a deity under the trees. There are three variations of cast forms - two have only metal content and these are usually flat motifs or thin walled hollw containers or figurines without a clay core, while the third type includes objects of larger volumes such as animals and lamp stands, where a clay core is retained inside a thin layer of metal as an economic measure. In some cases, when the outer layer is a lattice , then this core is mechanically removed in the finishing stage. Rice husk is added to the core to reduce its weight. The decorative parts of the object are separately added with wax filled cavity. Alternately, the entire assembly is fired in an open kiln and when the heated wax starts to evaporate, the liquefied metal is poured in the central cavity.

Inset : A rare artifact from Pahad Chidwa - a lamp on a tortoise`s back. Many such artifacts come from this little known village, where one family has been producing delightful work.

http://www.cohands.in/handmadepages/book480.asp?t1=480&lang=English

A group of musicians from Bison Horn Maria tribe, Ektal

Ritualistic lamp gifted to a daughter by her father on her wedding, Ektal.

Cast figurine of a goddess.

The mahua tree depicts people celebrating the Karma festival, Ektal.

Toys form another range of products that are made in Ektal. Toys are generally small (not more than a few inches). Shown below is a bullock on wheels, the wheels are attached separately with a metal wire.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFkj6d0aN1g

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-fCL9GlVQg

Bell Metal Craft_Making Process

Uploaded on Nov 9, 2011

'Bell metal crafts of Sarthebari' is Design Resource From IIT Guwahati.

Bell Metal Craft - Sarthebari is home to the bell metal industry, the second largest handicraft of Assam. Bell metal is an alloy of copper and tin and utensils made from it are used for domestic and religious purposes.

Bell Metal Craft_ Making Process - The craftsmen in Sarthebari (also referred as Kahar or Orja) still resort to the age old tools required for burning and shaping the metal. The process is as below.

-Processing the raw material

-Solidifying the molten metal

-Filing of the rough edges

-Scraping off the burnt layer

-Carving imprints on the bell metal ware

-Bhor mara or carving rings on the bowl

For more information on resources visit http://www.dsource.in

Write to us at contact@dsource.in

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XidvVCiQsQw

Masters of Fire: Hereditary Bronze Casters of South India

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SuEzTXCk4c

Uploaded on May 27, 2010

Featuring UC San Diego archaeology professor Tom Levy, this video is based on ethnoarchaeological research in the town of Swamimalai in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. For centuries Swamimalai has been the center of bronze Hindu icon manufacturing in the region, with its workshops passed down from generation to generation of hereditary sthapathis ('artisans' in Tamil).

Imagecasting in Swamimalai

Published on Mar 12, 2013

visiting a bronze casting workshop in Swamimalai, India

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0The8sbE-0g

Casting a Metal Statue, Swamimalai

Uploaded on Feb 18, 2010

Suri Narayanan shares and demonstrates to the participants of the 2010 South Indian Odyssey about the traditional process of casting a metal statue. Suri lives in Swamimalai, South India and creates amazing metal statues for temples and homes.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoEW85KDZKQ

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

January 17, 2014

Cire perdue or lost-wax casting metallurgy spread from Meluhha into the Fertile Crescent (Nahal Mishmar). See: html http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html

Tin Road stretched from Meluhha in the east into the Fertile Crescent (Kultepe, Anatolia) defining the Bronze Age. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-and-tracking-tin-road-after-all.

Dhokra kamar as a Meluhha hieroglyph: Dholavira, Mohenjo-daro seals Rebus: lost-wax casting

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet with Meluhha hieroglyphs written on two sides. Hieroglyph: Ku. ḍokro, ḍokhro ʻ old man ʼ; B. ḍokrā ʻ old, decrepit ʼ, Or. ḍokarā; H. ḍokrā ʻ decrepit ʼ; G. ḍokɔ m. ʻ penis ʼ, ḍokrɔ m. ʻ old man ʼ, M. ḍokrā m. -- Kho. (Lor.) duk ʻ hunched up, hump of camel ʼ; K. ḍọ̆ku ʻ humpbacked ʼ perh. < *ḍōkka -- 2. Or. dhokaṛa ʻ decrepit, hanging down (of breasts) ʼ.(CDIAL 5567). M. ḍhẽg n. ʻ groin ʼ, ḍhẽgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. M. dhõgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. (CDIAL 5585). Glyph: Br. kōnḍō on all fours, bent double. (DEDR 204a) Rebus: kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner’s lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295) Tiger has head turned backwards. క్రమ్మర krammara. adv. క్రమ్మరిల్లు or క్రమరబడు Same as క్రమ్మరు (Telugu). Rebus: krəm backʼ(Kho.)(CDIAL 3145) karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali)

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-evidence-for-mleccha.htmlAncient Near East evidence for meluhha language and bronze-age metalware

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-metallurgical-roots-and-spread.html?q=dhokraMeluhha: spread of lost-wax casting in the Fertile Crescent. Smithy is the temple. Veneration of ancestors.

The hieroglyph of an old female with breasts hanging down and ligatured to the buttock of a bovine is also deployed on a Mohenjo-daro seal:

Mohenodaro seal. Pict-103 Horned (female with breasts hanging down?) person with a tail and bovine legs standing near a tree fisting a horned tiger rearing on its hindlegs.

Hieroglyph: N. dhokro ʻ large jute bag ʼ, B. dhokaṛ; Or. dhokaṛa ʻ cloth bag ʼ; Bi. dhŏkrā ʻ jute bag ʼ; Mth. dhokṛā ʻ bag, vessel, receptacle ʼ; H. dhukṛīf. ʻ small bag ʼ; G. dhokṛũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- ṭṭ -- : M. dhokṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ; -- with -- n -- : G. dhokṇũ n. ʻ bale of cotton ʼ; -- with -- s -- : N. (Tarai) dhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in ʼ.2. L. dhohẽ (pl. dhūhī˜) m. ʻ large thatched shed ʼ.3. M. dhõgḍā m. ʻ coarse cloth ʼ, dhõgṭī f. ʻ wallet ʼ.4. L. ḍhok f. ʻ hut in the fields ʼ; Ku. ḍhwākā m. pl. ʻ gates of a city or market ʼ; N. ḍhokā (pl. of *ḍhoko) ʻ door ʼ; -- OMarw. ḍhokaro m. ʻ basket ʼ; -- N.ḍhokse ʻ place covered with a mat to store rice in, large basket ʼ.(CDIAL 6880) Rebus: dhokra ‘cire perdue’ casting metalsmith.

Plate II. Chlorite artifacts referred to as 'handbags' f-g (w 24 cm, thks 4.8 cm.); h (w 19.5 cm, h 19.4 cm, thks 4 cm); j (2 28 cm; h 24 cm, thks 3 cm); k (w 18.5, h 18.3, thks 3.2) Jiroft IV. Iconography of chlorite artifacts. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jiroft-iv-iconography-of-chlorite-artifacts

Mohenjo-daro, ancient Indus Valley Civilization, Dancing Girl in Pakistan

Published on May 22, 2012

Mohenjo-daro (Mound of the Dead), is an archeological site situated in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. Built around 2600 BC, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. It is in UNESCO World Heritage List. This video is from Pakistan National Art Gallery. They permorformed this dance for Turkish Culture and Tourism delegation

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR_oMwDr4Gs

Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

Dance-step of Mohenjodaro as a hieroglyph. Rebus: metal, 'iron'

Dance-stepas hieroglyph on a potsherd, Bhirrana.

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ‘iron’(Munda); मेढ meḍh‘merchant’s helper’(Pkt.) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)

The ‘Dancing Girl’ (Mohenjo-daro), made by the lost-wax process; a bronze foot and anklet from Mohenjo-daro; and a bronze figurine of a bull (Kalibangan). (Courtesy: ASI) "Archaeological excavations have shown that Harappan metal smiths obtained copper ore (either directly or through local communities) from the Aravalli hills, Baluchistan or beyond. They soon discovered that adding tin to copper produced bronze, a metal harder than copper yet easier to cast, and also more resistant to corrosion.

Whether deliberately added or already present in the ore, various ‘impurities’ (such as nickel, arsenic or lead) enabled the Harappans to harden bronze further, to the point where bronze chisels could be used to dress stones! The alloying ranges have been found to be 1%–12% in tin, 1%–7% in arsenic, 1%–9% in nickel and 1%–32% in lead. Shaping copper or bronze involved techniques of fabrication such as forging, sinking, raising, cold work, annealing, riveting, lapping and joining. Among the metal artefacts produced by the Harappans, let us mention spearheads, arrowheads, axes, chisels, sickles, blades (for knives as well as razors), needles, hooks, and vessels such as jars, pots and pans, besides objects of toiletry such as bronze mirrors; those were slightly oval, with their face raised, and one side was highly polished. The Harappan craftsmen also invented the true saw, with teeth and the adjoining part of the blade set alternatively from side to side, a type of saw unknown elsewhere until Roman times. Besides, many bronze figurines or humans (the well-known ‘Dancing Girl’, for instance) and animals (rams, deer, bulls...) have been unearthed from Harappan sites. Those figurines were cast by the lost-wax process: the initial model was made of wax, then thickly coated with clay; once fired (which caused the wax to melt away or be ‘lost’), the clay hardened into a mould, into which molten bronze was later poured. Harappans also used gold and silver (as well as their joint alloy, electrum) to produce a wide variety of ornaments such as pendants, bangles, beads, rings or necklace parts, which were usually found hidden away in hoards such as ceramic or bronze pots. While gold was probably panned from the Indus waters, silver was perhaps extracted from galena, or native lead sulphide...While the Indus civilization belonged to the Bronze Age, its successor, the Ganges civilization, which emerged in the first millennium BCE, belonged to the Iron Age. But recent excavations in central parts of the Ganges valley and in the eastern Vindhya hills have shown that iron was produced there possibly as early as in 1800 BCE. Its use appears to have become widespread from about 1000 BCE, and we find in late Vedic texts mentions of a ‘dark metal’ (krṣnāyas), while earliest texts (such as the Rig-Veda) only spoke of ayas, which, it is now accepted, referred to copper or bronze.

Note:

Damaged circular clay furnace, comprising iron slag and tuyeres and other waste materials stuck with its body, exposed at lohsanwa mound, Period II, Malhar, Dist. Chandauli. http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/iron-ore.html

Meluhha: the Indus Civilization and Its Contacts with Mesopotamia (Oriental Institute lecture 58:48)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zcGLlLEbmIUploaded on Oct 7, 2010

Meluhha: the Indus Civilization and Its Contacts with Mesopotamia

Mark Kenoyer, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Meluhha -- the name for the Indus civilization found in Mesopotamian texts -- was an important source of exotic goods, many of which are preserved in the archaeological record of Mesopotamia. The movement of people and goods between these two regions established a pattern of interaction that continued in later periods and is still seen today. This lecture presents an overview of the Indus civilization and its contact with the Mesopotamia during the forth to second millennia BCE.

Indus valley civilization(mohenjo-daro)

Uploaded on Apr 1, 2008

©http://www.hexolabs.com

e-learning research on ancient Indian civilization produced at Hexolabs,SIIC, IIT Kanpur for a better insight, visit

Kindly do not treat this video clipping as an exact archaeological reference. The idea is to make children aware/understand the whole Indus valley cultural system.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SdGbamPgf8o&list=PL01A404D5E75BB79C

The Indus Valley Civilisation of India and Pakistan (Video 52:19)

Published on May 11, 2013 (Prof. RS Bisht, Dr. KS Nauriyal, Dr. Walid Yasin, and Dr. khaled Alsendi as tour guides of Dholavira, a stretch of River Sarasvati, links with Mesopotamia)

DISCLAIMER: THIS VIDEO HAS BEEN POSTED FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND/OR EDUCATIONAL VALUE ONLY!

This channel is katy665412's alt. channel, created because katy665412 is unable to upload anymore videos due to copyright notices.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dIZWnwI47M

Glyph: araṇe 'lizard' (Tulu) Rebus: eraṇi f. ʻ anvil ʼ (Gujarati); aheraṇ, ahiraṇ, airaṇ, airṇī, haraṇ f. ‘anvil’(Marathi)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qREtAv9hwo

![]()

http://chhattisgarhhandicrafts.blogspot.in/2010/06/bastar-art.html

DHOKRA - LOST WAX METAL CASTING

The Mother Goddess folk bronze from bastar

Published: April 6, 2010 16:01 IST | Updated: April 6, 2010 16:05 IST

Bastar art goes global, but artisans battle for survival

The intricately carved metal bell, wood and bamboo products adorn many a home in India and abroad. But the nearly 20,000 tribal families in Chhattisgarh who crafted them remain mired in poverty, with no direct access to the market that is giving increasing shelf space to the figurines and wall hangings.

“There is rising demand for our products from foreign countries as well as from various regions of India, but despite the market boom, poverty is worsening day by day,” said Sonu Mandwai, a 33-year-old artisan from the interior Abujmad area of Narayanpur district in Bastar.

The thickly forested Abujmad area is part of the 40,000 sq km tribal-dominated Bastar region, a stronghold of Maoists.

Comprising the districts of Bijapur, Kanker, Narayanpur, Bastar and Dantewada, the Bastar region is home to roughly 20,000 artisans with traditional expertise in making world-class handicraft items in bell metal, wood, wrought iron, terracotta, bamboo, leather and from horn and bone.

However, the artisans are unable to make money from their products as the middlemen or traders who supply the markets purchase the finished items from them at low cost and sell it in the market at a price twenty times higher.

The middlemen are especially active in the main artisans’ centres of Kondagaon, Keshkal, Pharasgaon, Narayanpur and Bade Dongar.

Shyamsundar Vishwakarma, a Chhattisgarh State award winner for iron craft, said, “It is not a profitable business at all. People appreciate my products, but the overall lack of direct marketing channels of Bastar handicraft items in national and international market keep the artisans battling to survive.”

Sharda Salam, another artisan in Abujmad’s Bhutakhar village who makes 15 designs of bamboo craft, said, “Rising poverty is killing the Bastar artisans despite some government support. We make items so we can prosper but the profit goes to middlemen and we continue to struggle to feed our families.

“If this trend continues, the nation will see the end of Bastar’s art,” she said.

B.K. Sahu, officer in charge of Bastar region of the State government’s Chhattisgarh Hastshilp Vikas (Handicrafts Development) Board that is assigned to launch schemes to care of artisans, admitted the artisans were still stuck in poverty though their products were selling in India and abroad.

“Their economic condition is improving with the rise in demand of their products such as the bamboo flute which are unmatched in the national and global market. They are recovering from poverty, but the recovery pace is extremely slow,” Sahu told IANS on the sidelines of a function organised by the State government to showcase tribal art in Raipur’s Guru Ghasidas Museum complex.

Dozens of Bastar artisans had put up stalls at the function, which ended Sunday.

“In a just concluded week-long fair in Raipur at ‘Chhattisgarh Haat’, the handicraft items of Bastar artisans made a sale of over Rs.1.25 million, which was much higher than my expectations. It is just an indication how perfectly they carve out their products,” Sahu said.

“In the past one year, their products made record sales in Italy, France, Britain and other European nations and now we are targeting to enter the US market,” he said, adding that the board had just launched an “Abujmad to America” campaign.

http://www.thehindu.com/arts/crafts/bastar-art-goes-global-but-artisans-battle-for-survival/article389506.ece?css=print

Bastar Art in chhattisgarh

Bastar Art in Chhattisgarh Rajyotsava 2011

Dhokra, the tradition of making lost wax cast ritualistic and utility objects is a finely developed art of Chhattisgarh, with a large concentration of craftspersons in Bastar region. However this evolved art is practiced in many places extending from Orissa to West Bengal.

The process involves many stages: making of the core in fine sand and clay; making an armature with wax threads and strips that depict the image; encasing it with a clay mould with vents and inlet; pouring molten brass and casting; removing the cast, finishing and polishing with sandpaper. In Bastar, the Gharuas use wax for metal casting the idols, which they install in the devgudi, village shrine, of a deity under the trees. There are three variations of cast forms - two have only metal content and these are usually flat motifs or thin walled hollw containers or figurines without a clay core, while the third type includes objects of larger volumes such as animals and lamp stands, where a clay core is retained inside a thin layer of metal as an economic measure. In some cases, when the outer layer is a lattice , then this core is mechanically removed in the finishing stage. Rice husk is added to the core to reduce its weight. The decorative parts of the object are separately added with wax filled cavity. Alternately, the entire assembly is fired in an open kiln and when the heated wax starts to evaporate, the liquefied metal is poured in the central cavity.

Inset : A rare artifact from Pahad Chidwa - a lamp on a tortoise`s back. Many such artifacts come from this little known village, where one family has been producing delightful work.

http://www.cohands.in/handmadepages/book480.asp?t1=480&lang=English

A group of musicians from Bison Horn Maria tribe, Ektal

Ritualistic lamp gifted to a daughter by her father on her wedding, Ektal.

Cast figurine of a goddess.

The mahua tree depicts people celebrating the Karma festival, Ektal.

Toys form another range of products that are made in Ektal. Toys are generally small (not more than a few inches). Shown below is a bullock on wheels, the wheels are attached separately with a metal wire.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Chhattisgarh: Ektaal – A crafts Village

Ektaal, a village located near Raigarh is a small and very basic village, what makes it special is the fact it is home to many national and state level award-winning artisans. The whole village is engaged in making handmade metal craft popularly known as Dokra art. They continue to use the age-old technique of Lost Wax method that was used even during the times of Indus Valley Civilization. Designs are made on a clay tablet with threads of bee wax. Wax strands are also made using a small wooden machine using simple pressing method. Another layer of clay is added to mould after the wax settles and then the molten metal is put between the two clay layers. The wax burns out and the metal settles in its place and when the clay mould is broken the shining metal comes out in the desired shape.

We found women were engaged in laying the design part on clay tablets, while men were taking care of the rest of the activities like making wax stands, putting the slay moulds on fire, breaking it, arranging the finished product and making an effort to sell it. Most of the designs revolve around tribal deities and folk characters and their stories. They are slowly trying to come up with designs on usable items like cutlery etc., though I think a lot can be done to use the same art for the changing needs of the world.

I enjoyed my small conversation with the national award winner Smt Budhiarin Devi who proudly showed us her latest creation that won her the state level award. It was interesting to hear about her travels and her impression of the places she has visited. These expert artisans travel around the country showcasing their art. From time to time they get invited to conduct workshops on their craft in other states. Their craft has in a way become their vehicle to see the world while providing the world a window into their own culture. Is that not one of the prime purposes of the art – to communicate across all man made divides.

I remember visiting the Chhattisgarh state emporium in Raipur that is run by a committee with a curious name – Jhitku Mitki. I enquired by guide about Jhitku Mitki, he said they are just a part of folklore but could not tell the story associated with the name, but something kept telling me that there must be a story associated with these names. I came back and searched on the Internet and found this story: Mitki was a young girl in a family of seven brothers that lived in the area of Bastar. As Mitki grew up her brothers brought home Jhitku, a young man to marry her, and both Jhtiku Mitki fell in love with each other. After a while the family needed someone to be sacrificed for a religious ritual and as they could not find anyone else, they sacrificed Jhitku. Mitki could not take this and she also killed herself and since then the tribes of Bastar worship them as a couple. People here believe that all your wishes come true when you worship Jhitku Mitki. They are also known by other names like Gappa Dei and Lakkad Dei, or Dokra-Dokri. They have also become an essential part of artwork that this area creates.

Most of the villagers in Ektaal belong to Jhara tribe, which is a sub-tribe of Gonds. They migrated here from Orrisa sometime back.

Published on Sep 2, 2012

For World Craft Council...This video was shot at Urban Haat Hazaribagh, We really thank The Artisans, MD Jharcraft, Munmun Biswas, Swati Mittal, Raman Poddar, Akash Mitra, Mangkhankhual for all their support.......

Mritunjay Kumar and Chirapriya Mondal

Design Programme, IITK

Mritunjay Kumar and Chirapriya Mondal

Design Programme, IITK

3

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFkj6d0aN1g

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-fCL9GlVQg

Uploaded on Dec 30, 2008

The Dokhra or Dokra group of tribal craftsmen who live in an around West Bengal, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh create wonderfully sculpted products of cast metals. What makes Dokhra metal casting unique is that it uses the lost wax process or Cire Perdue to cast brass or bronze. The word Dokhra in Bengali denotes contempt for those who are socially low and despised. Within all the social hierarchy in West Bengal, these metalworkers are the most persecuted. The Dokhras currently live in the western part of West Bengal in four districts namely, Midnapore, Purulia, Bankura and Burdwan. The metalworkers in this film are from Burdwan. These Dokhra casters make various kinds of images and figures of deities like Siva and Ganesh, and animals such as owls, horses and strangely enough (considering that they live inland) fish.

The film provides a brief context in which the Dokhra craftsmen live and then moves on to describe the casting process. A documentary by Gillian Bormann and Alex Senior.

The film provides a brief context in which the Dokhra craftsmen live and then moves on to describe the casting process. A documentary by Gillian Bormann and Alex Senior.

Bell Metal Craft_Making Process

Uploaded on Nov 9, 2011

'Bell metal crafts of Sarthebari' is Design Resource From IIT Guwahati.

Bell Metal Craft - Sarthebari is home to the bell metal industry, the second largest handicraft of Assam. Bell metal is an alloy of copper and tin and utensils made from it are used for domestic and religious purposes.

Bell Metal Craft_ Making Process - The craftsmen in Sarthebari (also referred as Kahar or Orja) still resort to the age old tools required for burning and shaping the metal. The process is as below.

-Processing the raw material

-Solidifying the molten metal

-Filing of the rough edges

-Scraping off the burnt layer

-Carving imprints on the bell metal ware

-Bhor mara or carving rings on the bowl

For more information on resources visit http://www.dsource.in

Write to us at contact@dsource.in

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XidvVCiQsQw

Masters of Fire: Hereditary Bronze Casters of South India

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SuEzTXCk4c

Uploaded on May 27, 2010

Featuring UC San Diego archaeology professor Tom Levy, this video is based on ethnoarchaeological research in the town of Swamimalai in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. For centuries Swamimalai has been the center of bronze Hindu icon manufacturing in the region, with its workshops passed down from generation to generation of hereditary sthapathis ('artisans' in Tamil).

Imagecasting in Swamimalai

Published on Mar 12, 2013

visiting a bronze casting workshop in Swamimalai, India

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0The8sbE-0g

Casting a Metal Statue, Swamimalai

Uploaded on Feb 18, 2010

Suri Narayanan shares and demonstrates to the participants of the 2010 South Indian Odyssey about the traditional process of casting a metal statue. Suri lives in Swamimalai, South India and creates amazing metal statues for temples and homes.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoEW85KDZKQ

A ‘Sheffield of Ancient India’: Chanhu-Daro’s Metal working Industry. Illustrated London News 1936 – November 21st, p.909. 10 x photos of copper knives, spears , razors, axes and dishes.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

January 17, 2014