Source: http://www.orient-gesellschaft.de/forschungen/projekt.php?p=9 Since 1898, in the service of research into the history of the ancient Near East

Abstract

Positing the presence of ancestors of Assur (Ganga valley) in Tigris-Euphrates valley, the following monograph presents rebus readings of hieroglyphs of Assur using Meluhha of Indian linguistic area (sprachbund). The locus and context are the Tin Road from Assur to Kanesh (Kultepe) and 3rd millenium BCE Bronze-age involving movement of tin from Meluhha into Ancient Near East (Fertile Crescent) to promote and sustain the tin-bronze revolution which changed the story of civilization and interaction between Meluhha and the Fertile Crescent, for millenia thereafter..

Cat. no. 68 clay tablet with cuneiform text and Meluhha hieroglyphs.Ram-fish hieroglyphs: Tagara ‘ram’ + ayo ‘fish’; rebus: tagara ‘tin’, ayo ‘metal’ (perhaps bronze formed by alloying copper mineral with tin mineral). (For the altar as a hieroglyph, see embedded discussion on Tukulti-Ninurta fire-altar reading rebus the representation of fire-god). Thus, the composition is seen as a metallurgist's smithy viewed as a temple.

In Meluhha, the same word connotes both a smithy and a temple: kole.l (Kota)

Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace.Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge (DEDR 2133).

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta north of Assur had a temple complex on the left bank of River Tigris. On the wetern side was a ziggurat which had a tablet identifying the temple of Assur with the image of the deity moved from Assur. North of the temple was a palace placed on a platform originally 18m. high. The decorated wall painting fragment is from the palace.

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was first excavated from 1913 to 1914 by a German team from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Company) led by Walter Bachmann which was working at the same time at Assur. The finds are now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, in the British Museum and in Istanbul. Bachmann did not publish his results and his field notes were lost. A full excavation report appeared only in 1985. Work at the site was resumed in 1986 with a survey by a team from the German Research Foundation led by R. Dittman. A season of excavation was conducted in 1989. (R. Dittman, Ausgrabungen der Freien Universitat Berlin in Assur und Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta in den Jahren 1986-89, MDOG, vol. 122, pp. 157-171, 1990) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.

Cognate Meluhha gloss: कारु [ kāru ] m (S) An artificer or artisan. 2 A commonterm for the twelve बलुतेदार q. v. Also कारुनारु m pl q. v. in नारुकारु . This gloss may be the substrate which explains the 'kar' as 'port' on Tigris river. The lexemes, kar, karum may thus relate to the places where artificers or artisans work and hence elaborated semantically as 'trading colonies', particularly for tin and wool.

खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार ; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन् , which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith.-më˘ʦü 1 -म्य&above;च&dotbelow;ू&below; । लोहकारमृत्तिका f., 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore.-ʦañĕ -च्&dotbelow;ञ लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि ), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil. (Kashmiri). In Kashmiri khar 1 खर् खरः m (f. khürü or khariñ खरिञ् ), a donkey, an ass. (Note: use of donkey caravans to transport tin and wool on the Tin Road; this might also explain the meaning of karum as 'trading colony').

Drawing of the seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig 131. Cat. no. 68 description: "Tablet with cylinder seal impression: temple facade. Baked clay. Middle Assyrian period reign of Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 BCE). Found in a clay jar (a) in the Assur Temple h.6.5 cm. w. 6.7 cm. VAT 15468 (Ass 18771br). This clay tablet was part of a major archive preserved in several clay vessels in a room of the Assur Temple. One group of documents could be dated to the reign of the Assyrian king Tiglath0-pileser I. This tablet lists the supplies of barley, honey, sesame, and fruit received by the temple of Assur as the standard offering from the city of Assur or the province of Talmushu, represented by the governor Sin-zera-iddina. The receipt, formulated as a contract, was executed in two copies jointly sealed by the donor of the offering and its recipient. The present tablet may bear the seal of the governor of Talmushu. The image on the seal shows a highly detailed temple facade with an entrance flanked by crenellated towers. One can clearly distinguish niches in the structure and windows above. In the centre, in front of the temple entrance, stands a cult pedestal, similar to the one shown with a depiction of Tukulti-Ninurta I (cat. no. 75). The pedestal, structured by vertical pilasters, has volutes on the upper corners. On either side of the pedestal rests a goat-fish, a mythical feture with the head and body of a goat but the tail of a fish. Streams of water flow decoratively upward behind them. It may be that these creatures, like the goat-fish in countless other depictions, on kudurru (boundary stones) for example, are to be thought of as animals sacred to the water god Ea. It is therefore tempting to see the structure itself as a temple of Ea. One could also interpret the fabulous beasts as apotropaic guardians like those of later Neo-Assyrian temples, which had no particular association with the water god. This seal image is one of the few depictions of architecture in ancient Near Eastern art and is therefore of great importance for the reconstruction of Mesopotamian templs. From it we learn of the presence of crenellations and of windows, few traces of which have survived on actual monuments. In this period gateways were apparently not vaulted. No temple of the god Ea has been identified at Assur, and therefore the seal depiction cannot be associated with a specific Assur shrine. The seal image is representative of the style of late Middle Assyrian seal carving, which tended to stree linear pattern over the three-dimensionality that was characteristic of the earlier period. In general, landscape elements are lacking, and the individual figures appear massive and strongly contoured. '(Harper, Prudence Oliver, 1995, Assyrian origins: discoveries at Assur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, New York, Metropolitcan Museum of Art, p.105.)

Cognate Meluhha gloss: कारु [ kāru ] m (S) An artificer or artisan. 2 A common

Drawing of the seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig 131. Cat. no. 68 description: "Tablet with cylinder seal impression: temple facade. Baked clay. Middle Assyrian period reign of Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 BCE). Found in a clay jar (a) in the Assur Temple h.6.5 cm. w. 6.7 cm. VAT 15468 (Ass 18771br). This clay tablet was part of a major archive preserved in several clay vessels in a room of the Assur Temple. One group of documents could be dated to the reign of the Assyrian king Tiglath0-pileser I. This tablet lists the supplies of barley, honey, sesame, and fruit received by the temple of Assur as the standard offering from the city of Assur or the province of Talmushu, represented by the governor Sin-zera-iddina. The receipt, formulated as a contract, was executed in two copies jointly sealed by the donor of the offering and its recipient. The present tablet may bear the seal of the governor of Talmushu. The image on the seal shows a highly detailed temple facade with an entrance flanked by crenellated towers. One can clearly distinguish niches in the structure and windows above. In the centre, in front of the temple entrance, stands a cult pedestal, similar to the one shown with a depiction of Tukulti-Ninurta I (cat. no. 75). The pedestal, structured by vertical pilasters, has volutes on the upper corners. On either side of the pedestal rests a goat-fish, a mythical feture with the head and body of a goat but the tail of a fish. Streams of water flow decoratively upward behind them. It may be that these creatures, like the goat-fish in countless other depictions, on kudurru (boundary stones) for example, are to be thought of as animals sacred to the water god Ea. It is therefore tempting to see the structure itself as a temple of Ea. One could also interpret the fabulous beasts as apotropaic guardians like those of later Neo-Assyrian temples, which had no particular association with the water god. This seal image is one of the few depictions of architecture in ancient Near Eastern art and is therefore of great importance for the reconstruction of Mesopotamian templs. From it we learn of the presence of crenellations and of windows, few traces of which have survived on actual monuments. In this period gateways were apparently not vaulted. No temple of the god Ea has been identified at Assur, and therefore the seal depiction cannot be associated with a specific Assur shrine. The seal image is representative of the style of late Middle Assyrian seal carving, which tended to stree linear pattern over the three-dimensionality that was characteristic of the earlier period. In general, landscape elements are lacking, and the individual figures appear massive and strongly contoured. '(Harper, Prudence Oliver, 1995, Assyrian origins: discoveries at Assur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, New York, Metropolitcan Museum of Art, p.105.)

"...More strikingly on top of the depicted pedestal there is not the lamp, the usual divine symbol for the god Nuska, but most likely the representation of a tablet and a stylus, symbols for the god Nabû. (Klaus Wagensonner, University of Oxford)..." http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=pedestal_tukulti_ninurta Editions: Grayson, A.K. 1987. The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Period, I: Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia B.C. (to 1115 B.C.), Toronto, p. 279ff.; Bahrani, Z. 2003. The Graven Image. Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia, 192ff.

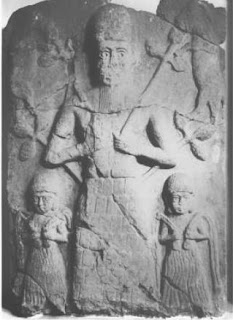

"...More strikingly on top of the depicted pedestal there is not the lamp, the usual divine symbol for the god Nuska, but most likely the representation of a tablet and a stylus, symbols for the god Nabû. (Klaus Wagensonner, University of Oxford)..." http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=pedestal_tukulti_ninurta Editions: Grayson, A.K. 1987. The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Period, I: Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia B.C. (to 1115 B.C.), Toronto, p. 279ff.; Bahrani, Z. 2003. The Graven Image. Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia, 192ff.Cat. no. 75 Cult pedestal of the god Nusku. Alabaster Middle Assyrian period, reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243-1207BCE). Found in the Ishtar temple, in the debris of Room 6. H. 57.7 c. w. 57.7 cm. VAT 8146 (Ass 19869). "These stone socles, each of the same shape, were found in Room 6 of the Ishtar temple, established by inscribed bricks to have been built by the king Tukulti-Ninurta I. One example is decorated with a worship scene; the other two bear no figures and are essentially plain. While the first was recovered resting, slightly askew on a low level of debris, the latter two socles were set into the brick pavement. The excavator Walter Andraw argued convincingly that the socled were not recovered in their original position. Their backs were left undecorated, indicating that they were designed to be placed against a wall, which was not their position in Room 6; the decorated socle was manifestly in a secondary position; and, finally, sometime after the deposition of the socles the door of Room 6 was sealed off. Andrae suggested that the three socles were originally placed in the main Cult Room, that at some time they were no longer needed there and subsequently were moved for safe storage. The sealed room was interpreted as a ritual 'burial' needed to enclose and ptotect the sacred objects. Andrae also assigned another decorated socle (Ass 20069, now in the archaeological museum in Istanbul), which was recovered to the side of the temple's door, to an original position in the Cult Room. The present decorated socle is sculpted in one piece in the form of a base consisting of two plinths of different heights, above which is a bordered rectangular area that has a semicircular projection at each upper end; a thirteen-petal rosette fills the corner spaces. Andrae noted that the full height to the top of the swellings is the same as that of tull width measured from both the plinth and the swellings and thus the socile is essentially a square. On the plinths is an incomplete cuneiform inscription, which preserves enough to inform us that the socle belongs to Nusku, the deity of light, who intercedes with the higher deities Assur and Enlil for Tukulti-Ninurta I and who prays for him daily. The scene represented above is extraordinary and sensitive. Two male figures, one kneeling, the other walking, move from the left toward a socle that is exactly the same in form as the one that bears the scene. Depicted above the relief socle is a rectangular form behind a tapering rod. The human figures make it clear that the socle or what rests on it, or possibly the ensemble, is being worshipped. But it remains unclear just what is depicted on the socle. Interpretations suggest that a door of a temple is represented, or that the rod is the bright rod of Nusku, or that, inasmuch as something about fate is preserved in the inscription, the rod is a stylus, the rectangle a tablet, and thus it is there to record the king's fate. Whatever is represented, however, is not a deity itself but rather a symbol. The two human figures are depicted exactly the same in all details of physiognomy and dress, which consists of an undergarment and covering mantle, the same worn in later centuries by Neo-Assyrian kings. They also both carry a mace, a sign of royal power, in the left hand, and from a clenched fist they extend their right forefinger toward the object of veneration, the typical Assyrian gesture of prayer. All scholars agree that the best interpretation here is that the two figures ar Tukulti-Ninurta I represented twice, in a sequential action of approaching and then kneeling before the socle. The narrative form is an innovation of the Middle Assyrian period, but it is not the only extraordinary feature of the socle. Previously a king in prayer before a deity depicted on a relief on a cylinder seal was shown walking, and this is the first time in such a portrayal that he is represented kneeling. Moreover, representation of the symbol of a deity, rather than the deity itself, as the object of worship seems to occur first in this period. Supporting this view are two contemporary Assyrian seal impressions from Assur that depict socles exactly like the present example (see cat. no. 68).

Depicted above the socle on one of the seals is a seated dog, the symbol of the goddess Gula, and flanking the other are symbols of Ea. While similarly shaped socles were recovered in Assyria from the ninth century BCE, they were recovered out of original contexts, so we do not know whether at that time they held symbols or deities. We are fortunate that enough of the inscription survives to establish a date both for creation of this fine work and for the innovative features that it reveals." (Harper, Prudence Oliver, 1995, Assyrian origins: discoveries at Assur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, New York, Metropolitcan Museum of Art, p.113).

No, it is not a representation of a tablet and a stylus, but a chump, a block of wood, karaṇḍā read rebus: karandi 'fire-god' (Munda). Thus, the chump is the divine symbol of fire-god.

करंडा [karaṇḍā] A clump, chump, or block of wood. 4 The stock or fixed portion of the staff of the large leaf-covered summerhead or umbrella. करांडा [ karāṇḍā ] m C A cylindrical piece as sawn or chopped off the trunk or a bough of a tree; a clump, chump, or block.

Allograph: करडी [ karaḍī ] f (See

Rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy' of arka 'copper'.

Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda)

The hieroglyphs on the fire-altar confirm the link to metallurgy with the use of 'spoked-wheel' banner carried on one side of the altar and the 'safflower' hieroglyph flanking the altar worshipped by Tukulti-Ninurta. It is rebus, as Sigmund Freud noted in reference to the dream. 'I have revealed to Atrahasis a dream, and it is thus that he has learned the secret of the gods.' (Epic of Gilgamesh, Ninevite version, XI, 187.)(Zainab Bahrani, 2011, The graven image: representation in Babylonia and Assyria, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, p. 185)

Tukulti-Ninurta I (meaning: "my trust is in [the warrior god] Ninurta"; reigned 1243–1207 BCE) was a king of Assyria (Sumer-Akkad) during the Middle Assyrian Empire (1366 - 1050 BCE). He built a ziggurat for Ishtar-Dinitu (Ishtar of the Dawn).

Kar Tukulti-Ninurta means 'Port (of) Tukulti-Ninurta', the name of what was perhaps the capital city built by Tukulti-Ninurta I on the left bank of River Tigris.

karrum is a trading colony centered around the port, kar. The trading colonies mostly traded in tin and woollen textiles. The karrums linked Assur and Kultepe (Anatolia) on the now famously called 'Tin Road' since over 20,000 tablets with cuneiform texts have been found in Kultepe.

Assur from ca. 2600 BCE

'The earliest traces of settlement in Assur can be found in layer H of the Ishtar temple, but also in the oldest layers beneath the Old Palace, dating to the late Early Dynastic period (in the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE).'http://www.assur.de/Themen/Stadtgeschichte_Engl/body_stadtgeschichte_engl.html

Assur from ca. 2600 BCE

'The earliest traces of settlement in Assur can be found in layer H of the Ishtar temple, but also in the oldest layers beneath the Old Palace, dating to the late Early Dynastic period (in the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE).'http://www.assur.de/Themen/Stadtgeschichte_Engl/body_stadtgeschichte_engl.html

Kar Tukulti-Ninurta is located about 3 kms. north of Assur, Aššûr; Arabic: آشور / ALA-LC: Āshūr, a remnant of the last Ashurite kingdom. Assur was occupied from ca. 2600 BCE through 14th century CE. Aššur is the name of the chief deity of the city. At this site, over 16,000 tablets with cuneiform texts were discovered most of which are now in Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Ca. 2000 BCE Puzur-Ashur I founded a dynasty whose successors included Ilushuma, Erishum I and Sargon I who had built temples for Assur, Adad and Ishtar. The name of king Shamshi-Adad I (1813-1781 BCE) is a combination of 'shamash' meaning 'sun' and Adad 'divinity Adad'; during his reign, a ziggurat was built in Assur expanding the Aššur temple.

Temples to the moon god Sin (Nanna) and the sun god Shamash were built in the 15th century BC.

Mitanni empire was conquered by Ashur-ubalit in 1365 BCE. Later Hittite, Babylonian, Amorite and Hurrian territories were also annexed. Tukulti-Ninurta I's reign saw the building of temple for Ishtar. Tiglath-Pileser I (1115-1075BCE) built the Anu-Adad temple.

The hieroglyph of 'rosette' on the altar adorns the wrists of Assurnasirpal (ca. 911-612 BCE) "1. _e2-gal_ {disz}asz-szur-pab-a _sanga_ asz-szur ni-szit {d}be u {d}masz na-ra-am {d}a-nim u {d}da-gan ka-szu-usz _dingir-mesz gal-mesz man_ dan-nu _man szu2 man kur_ asz-szur _a_ tukul-masz _man gal_-e _man_ dan-ni _man szu2_ (Property of) the palace of Assurnasirpal (II), vice-regent of Assur, chosen of the gods Enlil and Ninurta, beloved of the gods Anu and Dagan, destructive weapon of the great gods, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta (II), great king, strong king, king of the universe...21. {gesz}dap-ra-ni {gesz}mes-kan-ni ina _ka2-mesz_-sza2 u2-re-ti _ku3-babbar-mesz ku3-sig17-mesz an-na-mesz zabar-mesz an-bar-mesz szu2_-ti _szu_-ia sza2 _kur-kur-mesz_ daprāni-juniper, (and) meskannu-wood, I hung in its doorways. Silver, gold, tin, bronze, iron, booty from the lands

The hieroglyph of 'rosette' on the altar adorns the wrists of Assurnasirpal (ca. 911-612 BCE) "1. _e2-gal_ {disz}asz-szur-pab-a _sanga_ asz-szur ni-szit {d}be u {d}masz na-ra-am {d}a-nim u {d}da-gan ka-szu-usz _dingir-mesz gal-mesz man_ dan-nu _man szu2 man kur_ asz-szur _a_ tukul-masz _man gal_-e _man_ dan-ni _man szu2_ (Property of) the palace of Assurnasirpal (II), vice-regent of Assur, chosen of the gods Enlil and Ninurta, beloved of the gods Anu and Dagan, destructive weapon of the great gods, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta (II), great king, strong king, king of the universe...21. {gesz}dap-ra-ni {gesz}mes-kan-ni ina _ka2-mesz_-sza2 u2-re-ti _ku3-babbar-mesz ku3-sig17-mesz an-na-mesz zabar-mesz an-bar-mesz szu2_-ti _szu_-ia sza2 _kur-kur-mesz_ daprāni-juniper, (and) meskannu-wood, I hung in its doorways. Silver, gold, tin, bronze, iron, booty from the lands 22. sza2 a-pe-lu-szi-na-ni a-na ma-a'-disz al-qa-a ina lib3-bi u2-kin2 over which I gained dominion, I took in great quantities and puttherein."http://cdli.ucla.edu/cdlisearch/search/index.php?SearchMode=Text&ResultCount=1000&txtContent=&requestFrm=Search&txtPrimaryPublication=G-02&order=primary_publication

Cult pedestal of Tukulti-Ninurta I, Ishtar Temple, Assur, Middle Assyrian Period.

Socle is a short plinth used to support a pedestal. Two socles depict Tukulti-Ninurta I. On one socle, he is shown kneeling in veneration before an altar with a central spike-rod. On another socle, he is standing between two standard-bearers. One one socle, the volutes show hieroglyphs of 'safflower'. On another socle, the volutes show hieroglphs of 'spoked-wheel'. The hieroglyph of 'spoked-wheel' recurs four times on Dholavira sign-board with a total of 10 Meluhha hieroglyphs.

A designer's impression (reconstruction) of how the Dholavira Signboard might have been mounted on a gateway to the citadel.

A designer's impression (reconstruction) of how the Dholavira Signboard might have been mounted on a gateway to the citadel.See:

Tin Road between Ashur-Kultepe and Meluhha hieroglyphs

Tukulti-Ninurta worships fire-god at the fire altar of Assur

The two standards (flagpoles) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal);

crystal (Kannada) Glyph: eraka

![]()

![]() Sign 391 which occurs 4 times on Dholavira Signboard.

Sign 391 which occurs 4 times on Dholavira Signboard.

Glyphic element: erako nave; era = knave of wheel. Glyphic element: āra ‘spokes’. Rebus: āra ‘brass’ as in ārakūṭa (Skt.) Rebus: Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt (DEDR 866) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.)

Glyphic element: kund opening in the nave or hub of a wheel to admit the axle (Santali) Rebus: kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295).

![]() (After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Assur temple at Assur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)

(After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Assur temple at Assur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)

lo ‘pot to overflow’ kāṇḍa ‘water’. Rebus: lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ (Marathi).

దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala -- n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} ``^branch, ^twig''. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen', ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig', Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree', ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it', So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch', H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/11/assur-asur-and-their-meluhha-speech-in.htmlFragments from a large stone vessel dted to ca. second millennium BCE, were reconstucted. Two caprids identified as ibexes are seen eating from a three-lobed, stylized plant,

comparable to the relief shown on Fig. 17. In the second register, a bull-man and a bearded man hold a standard crowned by a crescent moon and an eight-pointed star. Behind the bull-man is a fabulous creature perhaps with a lion's head and wings.

Note the hieroglyph of a 'tiger' to the right of a pair of antelopes. kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron' (Tamil)

Composite drawing of imagery on cat. no. 44. Original drawing by Katrin Hinz, redrawn by J. Ganem. (After Fig. 16 in Harper Prudence Oliver, ed., 1995, Assyrian origins: discoveries at Assur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 63

Two ibexes read rebus: miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.)

kūdī ‘twig’ Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’. The two ibexes + twig hieroglyhs, thus, connote a metal merchant/artisan with a smelter.

Lion: aryeh ‘lion’ Rebus: arā ‘brass’.

Bull: ḍangar Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi)

Three artefacts with Indus writing are remarkable for their definitive intent to broadcast the metallurgical message: 1. Dholavira signboard on a gateway; 2. Shahdad standard; and 3. Tablets showing processions of three standards: scarf hieroglyph, one-horned young bull hieroglyph and standard-device hieroglyph. Rebus readings of the inscriptions relate to and document the metallurgical competence of Meluhhan lapidaries-artisans. Some other select set of inscriptions from the wide, expansive area stretching from Haifa to Rakhigarhi, from Altyn Depe (Caucus) to Daimabad (Maharashtra) are presented to show the area which had evidenced the use of Meluhha (Mleccha) language of Indian sprachbund.

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations,harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Segment 1: Working in ore, molten cast copper, lathe (work)

ḍato ‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍaren lid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼ Rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaḍha 'ficus religiosa' (Skt.); kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-heralded.html?q=dholavira+sign

Die europäischen Forschungsreisenden und Ausgräber des 19. Jhs. hatten Tulül al-cAqar, der 3 km oberhalb von As sur auf dem jenseitigen, östlichen Ufer des Tigris gelegenen Ruinenstätte, keine nennenswerte Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Als jedoch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft von 1903-1914 ihre Ausgrabungen in Assur durchführte, gehörte auch Tulül al-cAqar zum Grabungsgebiet. Die osmanische Regierung hatte, wie Walter Andrae berichtet, eine Genehmigung zur Untersuchung auch dieser benachbarten Stadtanlage bereitwilligst erteilt. So wurde es möglich, in einer vom Oktober 1913 bis März 1914 stattfindenden Kampagne, die unter der Leitung des Architekten Walter Bachmann stand, auf einem 62 ha großen, etwa rechteckigen Gelände die wichtigsten öffentlichen Gebäude auszugraben oder ihre Grundpläne im wesentlichen aufzunehmen (Abb. 81).

Das geschah unter Einsatz von zeitweise bis zu 270 Arbeitern, die an der Wallanlage und den im Stadtgebiet anstehenden Kuppen tätig wurden. Sie legten zunächst eine Toranlage (D) mit einem Teil der Stadtmauer frei, sodann den u. a. wegen seiner Wandmalereien erwähnenswerten Assur-Tempel (B) mit der -anders als in Assur - unmittelbar anschließenden Ziqqurrat sowie im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes den am Ufer des Tigris gelegenen Bereich des Nord- und des Südpalastes (M u. A). Ferner wandte man sich Teilen der inneren Stadtmauer (C u. L) zu, der Binnenmauer, die das Areal in eine Weststadt und eine Oststadt teilte. Außerdem kamen eine turmartige Anlage (K) unbekannter Bestimmung und ein Wohnhaus (J) zutage (Abb. 80a.b).

Durch den Fund einer Alabasterinschrift Tukulti-Ninurtas I. (1233-1197 v. Chr.) im Gebiet des Assur-Tempels erlangten Bachmann und Andrae sehr bald Gewißheit, daß in Tulül al-cAqar das antike Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (kār Tukultï-Ninurta: «Kai des Tukulti-Ninurta») vor ihnen lag. Von der Gründung und Ausstattung der zur Residenz und zum Kultmittelpunkt bestimmten neuen Stadt hatte man bereits aus einer in Assur gefundenen Inschrift des Königs erfahren. Tukulti-Ninurta I. stand am Ende einer

Reihe bedeutender Herrscher des späten 14. und des 13. Jhs. v. Chr., die Assyrien in zahlreichen Eroberungszügen zu dem mächtigsten Staat Vorderasiens gemacht hatten. Der Bedeutung der anscheinend unmittelbar nach dem gewaltsamen Tod Tukulti-Ninurtas I. wieder aufgegebenen Anlage waren sich die Ausgräber nur zu bewußt, als sie Walter Andrae «für die Datierung aller Einzelfunde ganz unschätzbar» nannten.

Obgleich es bisher zu keiner Gesamtpublikation jener ersten Kampagne in Tulül al-cAqar gekommen ist, sind wichtige Grabungsergebnisse sowohl in die Fachliteratur eingegangen als auch im Vorderasiatischen Museum zu Berlin für jedermann sichtbar geworden. Nach den ersten zusammenfassenden Berichten der Ausgräber, die in den Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft publiziert worden waren, hatte auch Walter Andrae in seinem Buch «Das wiedererstandene Assur» die Grabungsbefunde aus Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta resümiert. Bachmann, der später nicht mehr in der vorderasiatischen Archäologie arbeitete, war schließlich, von Andrae gedrängt, noch in seinen letzten Lebensjahren - er starb 1958 -bemüht, eine Endpublikation fertigzustellen.

Ohne einen Zugang zu diesem Manuskript und zum Grabungstagebuch wie auch Gewißheit über den Verbleib der Materialien erlangen' zu können, unter-

nahm es Tilman Eickhoff zu Beginn der 80er Jahre, die Dokumentation der Grabung, soweit sie im Archiv der DOG vorhanden war, aufzuarbeiten. Das Ergebnis liegt in monographischer Form vor.41

Erst im Jahre 1992 gelang es, im Landesarchiv Dresden den Nachlaß W. Bachmanns ausfindig zu machen und darin erwartungsgemäß umfangreiche Aufzeichnungen über die Grabungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta festzustellen. Deren weitere Bearbeitung hat R. Dittmann übernommen, der im Oktober und November 1986, also 72 Jahre nach jener ersten Untersuchung, eine weitere Grabungskampagne in Tulül al-cAqar geleitet hatte.

Diese sowohl personell als auch zeitlich vergleichsweise begrenzte Unternehmung hatte sich zum Ziel gesetzt, durch Oberflächenuntersuchungen und Testschnitte nach Möglichkeit einige der von der ersten Grabung gestellten Fragen zu beantworten. Zu diesen gehörte z.B. der Verlauf der nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung, das Ausmaß der Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes und die Struktur des Palastbereiches und des Wohnhauses. Ferner sollte ein topographischer Plan des Geländes angefertigt und ein Keramik-Corpus für das ausgehende 13. und beginnende 12. Jh. ermittelt werden.

Im Ergebnis der Untersuchungen ließ sich Klarheit darüber gewinnen, daß das Areal der Weststadt auch außerhalb der öffentlichen Bauten in bestimmten Sektoren besiedelt war und die Siedlungsspuren bis in die nachassyrische Zeit reichen. Zudem ergab der Survey, daß die Stadt erheblich umfangreicher war, als Bachmann angenommen hatte. Klar ist aber auch, daß nicht von einer dichten Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes gesprochen werden kann. Anders als in Assur sah man sich dank reichlich vorhandener freier Flächen nicht gezwungen, über älteren Bauresten zu siedeln.

Schon 1988 zeichnete sich die Möglichkeit ab, eine weitere Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta durchzuführen. Die Archäologen der Freien Universität Berlin unter der Leitung von Reinhard Ditt-mann sahen sich aber veranlaßt, in diesem Jahr in Assur zu arbeiten, da zu der Zeit das Ostufer des Tigris vom Grabungshaus in Assur her nicht erreichbar war. Erst 1989 konnten sie wieder in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta tätig werden.

Diese nächste und bisher letzte Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta führte zu weiteren überraschenden Ergebnissen. So konnten z.B. überwiegend mittelassyrische Siedlungsspuren noch 1,5 km südlich des Tores D festgestellt werden, womit inzwischen für diese Zeit eine Besiedlung auf mindestens 240 ha nachgewiesen ist. Eine sichere Aussage über die Ausdehnung der Stadt kann somit weiterhin nicht getroffen werden. Nach den Befunden aus den im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes in Flußnähe gelegenen Grabungsarealen A-F liegt unter einem spätassyrischen ein mittelassyrischer Komplex, der verschiedenen Anzeichen zufolge zum Palast Tukulti-Ninurtas I. zu gehören scheint. Er spricht dafür, daß sich die Anlagen des Nordpalastes in nördlicher Richtung wesentlich weiter ausdehnten, als man bisher annahm. Ferner wurde weit außerhalb der vermuteten nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung eine Erhebung (Teil O) untersucht, in der ein kleiner assyrischer Langraumtempel nachgewiesen werden konnte.

Nach den Ergebnissen der letzten beiden Kampagnen formulierten die Ausgräber ihre Vorstellungen von den noch zu

leistenden Untersuchungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta: «Problematisch, aber nicht uninteressant wäre eine partielle Freilegung des Hauptraumes des Nordpalastes, der noch unergraben und massiv ansteht, denn in diesem Teil sind vielleicht nicht nur Wandmalereien zu erwarten. Der Südpalastteil dagegen ist nur schwer anzugehen, da der gesamte Komplex stark erodiert ist.»42 Ähnlich skeptisch in Hinsicht auf den gegenwärtigen Zustand der Stadtanlage äußert sich Dittmann in einem weiteren Vorbericht: «Obgleich Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta flächenmäßig immer größer wird, ist das, was die rezenten landwirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten von der Ruine übriggelassen haben, erschütternd gering. Dies wenige in repräsentativem Umfang auszugraben, wird die Aufgabe der nächsten Kampagnen sein.»43

Unberührt von dem Befund, daß in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta auch reichliche neu-und nachassyrische Besiedlungsspuren vorliegen und sich dieser Sachverhalt für die neuassyrische Zeit in den keilschriftlichen Quellen zu bestätigen scheint, bleibt die Tatsache, daß der Ort nur während jener einen Regierungszeit Residenz war. Das verleiht ihm seine historische Bedeutung, während das schon von Walter Bachmann festgestellte nahezu völlige Fehlen von Kleinfunden im Assur-Tem-pel und auch dessen zugemauerte Türen deutlich auf eine bewußte Auflassung der offiziellen Gebäude hinzuweisen scheinen. Nicht zuletzt daher rührt das spezielle archäologische Interesse, das diese Stadtanlage nach wie vor erweckt.

http://www.orient-gesellschaft.de/forschungen/projekt.php?p=9

(After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Assur temple at Assur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)

(After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Assur temple at Assur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)lo ‘pot to overflow’ kāṇḍa ‘water’. Rebus: lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ (Marathi).

దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala -- n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} ``^branch, ^twig''. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen', ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig', Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree', ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it', So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch', H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

Three artefacts with Indus writing are remarkable for their definitive intent to broadcast the metallurgical message: 1. Dholavira signboard on a gateway; 2. Shahdad standard; and 3. Tablets showing processions of three standards: scarf hieroglyph, one-horned young bull hieroglyph and standard-device hieroglyph. Rebus readings of the inscriptions relate to and document the metallurgical competence of Meluhhan lapidaries-artisans. Some other select set of inscriptions from the wide, expansive area stretching from Haifa to Rakhigarhi, from Altyn Depe (Caucus) to Daimabad (Maharashtra) are presented to show the area which had evidenced the use of Meluhha (Mleccha) language of Indian sprachbund.

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations,harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations,harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Segment 1: Working in ore, molten cast copper, lathe (work)

ḍato ‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍaren lid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼ Rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

khuṇṭa 'peg’; khũṭi = pin (M.) rebus: kuṭi= furnace (Santali) kūṭa ‘workshop’ kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-heralded.html?q=dholavira+sign

Die europäischen Forschungsreisenden und Ausgräber des 19. Jhs. hatten Tulül al-cAqar, der 3 km oberhalb von As sur auf dem jenseitigen, östlichen Ufer des Tigris gelegenen Ruinenstätte, keine nennenswerte Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Als jedoch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft von 1903-1914 ihre Ausgrabungen in Assur durchführte, gehörte auch Tulül al-cAqar zum Grabungsgebiet. Die osmanische Regierung hatte, wie Walter Andrae berichtet, eine Genehmigung zur Untersuchung auch dieser benachbarten Stadtanlage bereitwilligst erteilt. So wurde es möglich, in einer vom Oktober 1913 bis März 1914 stattfindenden Kampagne, die unter der Leitung des Architekten Walter Bachmann stand, auf einem 62 ha großen, etwa rechteckigen Gelände die wichtigsten öffentlichen Gebäude auszugraben oder ihre Grundpläne im wesentlichen aufzunehmen (Abb. 81).

Das geschah unter Einsatz von zeitweise bis zu 270 Arbeitern, die an der Wallanlage und den im Stadtgebiet anstehenden Kuppen tätig wurden. Sie legten zunächst eine Toranlage (D) mit einem Teil der Stadtmauer frei, sodann den u. a. wegen seiner Wandmalereien erwähnenswerten Assur-Tempel (B) mit der -anders als in Assur - unmittelbar anschließenden Ziqqurrat sowie im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes den am Ufer des Tigris gelegenen Bereich des Nord- und des Südpalastes (M u. A). Ferner wandte man sich Teilen der inneren Stadtmauer (C u. L) zu, der Binnenmauer, die das Areal in eine Weststadt und eine Oststadt teilte. Außerdem kamen eine turmartige Anlage (K) unbekannter Bestimmung und ein Wohnhaus (J) zutage (Abb. 80a.b).

Durch den Fund einer Alabasterinschrift Tukulti-Ninurtas I. (1233-1197 v. Chr.) im Gebiet des Assur-Tempels erlangten Bachmann und Andrae sehr bald Gewißheit, daß in Tulül al-cAqar das antike Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (kār Tukultï-Ninurta: «Kai des Tukulti-Ninurta») vor ihnen lag. Von der Gründung und Ausstattung der zur Residenz und zum Kultmittelpunkt bestimmten neuen Stadt hatte man bereits aus einer in Assur gefundenen Inschrift des Königs erfahren. Tukulti-Ninurta I. stand am Ende einer

Reihe bedeutender Herrscher des späten 14. und des 13. Jhs. v. Chr., die Assyrien in zahlreichen Eroberungszügen zu dem mächtigsten Staat Vorderasiens gemacht hatten. Der Bedeutung der anscheinend unmittelbar nach dem gewaltsamen Tod Tukulti-Ninurtas I. wieder aufgegebenen Anlage waren sich die Ausgräber nur zu bewußt, als sie Walter Andrae «für die Datierung aller Einzelfunde ganz unschätzbar» nannten.

Obgleich es bisher zu keiner Gesamtpublikation jener ersten Kampagne in Tulül al-cAqar gekommen ist, sind wichtige Grabungsergebnisse sowohl in die Fachliteratur eingegangen als auch im Vorderasiatischen Museum zu Berlin für jedermann sichtbar geworden. Nach den ersten zusammenfassenden Berichten der Ausgräber, die in den Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft publiziert worden waren, hatte auch Walter Andrae in seinem Buch «Das wiedererstandene Assur» die Grabungsbefunde aus Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta resümiert. Bachmann, der später nicht mehr in der vorderasiatischen Archäologie arbeitete, war schließlich, von Andrae gedrängt, noch in seinen letzten Lebensjahren - er starb 1958 -bemüht, eine Endpublikation fertigzustellen.

Ohne einen Zugang zu diesem Manuskript und zum Grabungstagebuch wie auch Gewißheit über den Verbleib der Materialien erlangen' zu können, unter-

nahm es Tilman Eickhoff zu Beginn der 80er Jahre, die Dokumentation der Grabung, soweit sie im Archiv der DOG vorhanden war, aufzuarbeiten. Das Ergebnis liegt in monographischer Form vor.41

Erst im Jahre 1992 gelang es, im Landesarchiv Dresden den Nachlaß W. Bachmanns ausfindig zu machen und darin erwartungsgemäß umfangreiche Aufzeichnungen über die Grabungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta festzustellen. Deren weitere Bearbeitung hat R. Dittmann übernommen, der im Oktober und November 1986, also 72 Jahre nach jener ersten Untersuchung, eine weitere Grabungskampagne in Tulül al-cAqar geleitet hatte.

Diese sowohl personell als auch zeitlich vergleichsweise begrenzte Unternehmung hatte sich zum Ziel gesetzt, durch Oberflächenuntersuchungen und Testschnitte nach Möglichkeit einige der von der ersten Grabung gestellten Fragen zu beantworten. Zu diesen gehörte z.B. der Verlauf der nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung, das Ausmaß der Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes und die Struktur des Palastbereiches und des Wohnhauses. Ferner sollte ein topographischer Plan des Geländes angefertigt und ein Keramik-Corpus für das ausgehende 13. und beginnende 12. Jh. ermittelt werden.

Im Ergebnis der Untersuchungen ließ sich Klarheit darüber gewinnen, daß das Areal der Weststadt auch außerhalb der öffentlichen Bauten in bestimmten Sektoren besiedelt war und die Siedlungsspuren bis in die nachassyrische Zeit reichen. Zudem ergab der Survey, daß die Stadt erheblich umfangreicher war, als Bachmann angenommen hatte. Klar ist aber auch, daß nicht von einer dichten Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes gesprochen werden kann. Anders als in Assur sah man sich dank reichlich vorhandener freier Flächen nicht gezwungen, über älteren Bauresten zu siedeln.

Schon 1988 zeichnete sich die Möglichkeit ab, eine weitere Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta durchzuführen. Die Archäologen der Freien Universität Berlin unter der Leitung von Reinhard Ditt-mann sahen sich aber veranlaßt, in diesem Jahr in Assur zu arbeiten, da zu der Zeit das Ostufer des Tigris vom Grabungshaus in Assur her nicht erreichbar war. Erst 1989 konnten sie wieder in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta tätig werden.

Diese nächste und bisher letzte Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta führte zu weiteren überraschenden Ergebnissen. So konnten z.B. überwiegend mittelassyrische Siedlungsspuren noch 1,5 km südlich des Tores D festgestellt werden, womit inzwischen für diese Zeit eine Besiedlung auf mindestens 240 ha nachgewiesen ist. Eine sichere Aussage über die Ausdehnung der Stadt kann somit weiterhin nicht getroffen werden. Nach den Befunden aus den im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes in Flußnähe gelegenen Grabungsarealen A-F liegt unter einem spätassyrischen ein mittelassyrischer Komplex, der verschiedenen Anzeichen zufolge zum Palast Tukulti-Ninurtas I. zu gehören scheint. Er spricht dafür, daß sich die Anlagen des Nordpalastes in nördlicher Richtung wesentlich weiter ausdehnten, als man bisher annahm. Ferner wurde weit außerhalb der vermuteten nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung eine Erhebung (Teil O) untersucht, in der ein kleiner assyrischer Langraumtempel nachgewiesen werden konnte.

Nach den Ergebnissen der letzten beiden Kampagnen formulierten die Ausgräber ihre Vorstellungen von den noch zu

leistenden Untersuchungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta: «Problematisch, aber nicht uninteressant wäre eine partielle Freilegung des Hauptraumes des Nordpalastes, der noch unergraben und massiv ansteht, denn in diesem Teil sind vielleicht nicht nur Wandmalereien zu erwarten. Der Südpalastteil dagegen ist nur schwer anzugehen, da der gesamte Komplex stark erodiert ist.»42 Ähnlich skeptisch in Hinsicht auf den gegenwärtigen Zustand der Stadtanlage äußert sich Dittmann in einem weiteren Vorbericht: «Obgleich Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta flächenmäßig immer größer wird, ist das, was die rezenten landwirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten von der Ruine übriggelassen haben, erschütternd gering. Dies wenige in repräsentativem Umfang auszugraben, wird die Aufgabe der nächsten Kampagnen sein.»43

Unberührt von dem Befund, daß in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta auch reichliche neu-und nachassyrische Besiedlungsspuren vorliegen und sich dieser Sachverhalt für die neuassyrische Zeit in den keilschriftlichen Quellen zu bestätigen scheint, bleibt die Tatsache, daß der Ort nur während jener einen Regierungszeit Residenz war. Das verleiht ihm seine historische Bedeutung, während das schon von Walter Bachmann festgestellte nahezu völlige Fehlen von Kleinfunden im Assur-Tem-pel und auch dessen zugemauerte Türen deutlich auf eine bewußte Auflassung der offiziellen Gebäude hinzuweisen scheinen. Nicht zuletzt daher rührt das spezielle archäologische Interesse, das diese Stadtanlage nach wie vor erweckt.

http://www.orient-gesellschaft.de/forschungen/projekt.php?p=9

Das geschah unter Einsatz von zeitweise bis zu 270 Arbeitern, die an der Wallanlage und den im Stadtgebiet anstehenden Kuppen tätig wurden. Sie legten zunächst eine Toranlage (D) mit einem Teil der Stadtmauer frei, sodann den u. a. wegen seiner Wandmalereien erwähnenswerten Assur-Tempel (B) mit der -anders als in Assur - unmittelbar anschließenden Ziqqurrat sowie im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes den am Ufer des Tigris gelegenen Bereich des Nord- und des Südpalastes (M u. A). Ferner wandte man sich Teilen der inneren Stadtmauer (C u. L) zu, der Binnenmauer, die das Areal in eine Weststadt und eine Oststadt teilte. Außerdem kamen eine turmartige Anlage (K) unbekannter Bestimmung und ein Wohnhaus (J) zutage (Abb. 80a.b).

Durch den Fund einer Alabasterinschrift Tukulti-Ninurtas I. (1233-1197 v. Chr.) im Gebiet des Assur-Tempels erlangten Bachmann und Andrae sehr bald Gewißheit, daß in Tulül al-cAqar das antike Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (kār Tukultï-Ninurta: «Kai des Tukulti-Ninurta») vor ihnen lag. Von der Gründung und Ausstattung der zur Residenz und zum Kultmittelpunkt bestimmten neuen Stadt hatte man bereits aus einer in Assur gefundenen Inschrift des Königs erfahren. Tukulti-Ninurta I. stand am Ende einer

Reihe bedeutender Herrscher des späten 14. und des 13. Jhs. v. Chr., die Assyrien in zahlreichen Eroberungszügen zu dem mächtigsten Staat Vorderasiens gemacht hatten. Der Bedeutung der anscheinend unmittelbar nach dem gewaltsamen Tod Tukulti-Ninurtas I. wieder aufgegebenen Anlage waren sich die Ausgräber nur zu bewußt, als sie Walter Andrae «für die Datierung aller Einzelfunde ganz unschätzbar» nannten.

Obgleich es bisher zu keiner Gesamtpublikation jener ersten Kampagne in Tulül al-cAqar gekommen ist, sind wichtige Grabungsergebnisse sowohl in die Fachliteratur eingegangen als auch im Vorderasiatischen Museum zu Berlin für jedermann sichtbar geworden. Nach den ersten zusammenfassenden Berichten der Ausgräber, die in den Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft publiziert worden waren, hatte auch Walter Andrae in seinem Buch «Das wiedererstandene Assur» die Grabungsbefunde aus Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta resümiert. Bachmann, der später nicht mehr in der vorderasiatischen Archäologie arbeitete, war schließlich, von Andrae gedrängt, noch in seinen letzten Lebensjahren - er starb 1958 -bemüht, eine Endpublikation fertigzustellen.

Ohne einen Zugang zu diesem Manuskript und zum Grabungstagebuch wie auch Gewißheit über den Verbleib der Materialien erlangen' zu können, unter-

nahm es Tilman Eickhoff zu Beginn der 80er Jahre, die Dokumentation der Grabung, soweit sie im Archiv der DOG vorhanden war, aufzuarbeiten. Das Ergebnis liegt in monographischer Form vor.41

Erst im Jahre 1992 gelang es, im Landesarchiv Dresden den Nachlaß W. Bachmanns ausfindig zu machen und darin erwartungsgemäß umfangreiche Aufzeichnungen über die Grabungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta festzustellen. Deren weitere Bearbeitung hat R. Dittmann übernommen, der im Oktober und November 1986, also 72 Jahre nach jener ersten Untersuchung, eine weitere Grabungskampagne in Tulül al-cAqar geleitet hatte.

Diese sowohl personell als auch zeitlich vergleichsweise begrenzte Unternehmung hatte sich zum Ziel gesetzt, durch Oberflächenuntersuchungen und Testschnitte nach Möglichkeit einige der von der ersten Grabung gestellten Fragen zu beantworten. Zu diesen gehörte z.B. der Verlauf der nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung, das Ausmaß der Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes und die Struktur des Palastbereiches und des Wohnhauses. Ferner sollte ein topographischer Plan des Geländes angefertigt und ein Keramik-Corpus für das ausgehende 13. und beginnende 12. Jh. ermittelt werden.

Im Ergebnis der Untersuchungen ließ sich Klarheit darüber gewinnen, daß das Areal der Weststadt auch außerhalb der öffentlichen Bauten in bestimmten Sektoren besiedelt war und die Siedlungsspuren bis in die nachassyrische Zeit reichen. Zudem ergab der Survey, daß die Stadt erheblich umfangreicher war, als Bachmann angenommen hatte. Klar ist aber auch, daß nicht von einer dichten Besiedlung des Stadtgebietes gesprochen werden kann. Anders als in Assur sah man sich dank reichlich vorhandener freier Flächen nicht gezwungen, über älteren Bauresten zu siedeln.

Schon 1988 zeichnete sich die Möglichkeit ab, eine weitere Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta durchzuführen. Die Archäologen der Freien Universität Berlin unter der Leitung von Reinhard Ditt-mann sahen sich aber veranlaßt, in diesem Jahr in Assur zu arbeiten, da zu der Zeit das Ostufer des Tigris vom Grabungshaus in Assur her nicht erreichbar war. Erst 1989 konnten sie wieder in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta tätig werden.

Diese nächste und bisher letzte Kampagne in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta führte zu weiteren überraschenden Ergebnissen. So konnten z.B. überwiegend mittelassyrische Siedlungsspuren noch 1,5 km südlich des Tores D festgestellt werden, womit inzwischen für diese Zeit eine Besiedlung auf mindestens 240 ha nachgewiesen ist. Eine sichere Aussage über die Ausdehnung der Stadt kann somit weiterhin nicht getroffen werden. Nach den Befunden aus den im Nordwesten des Stadtgebietes in Flußnähe gelegenen Grabungsarealen A-F liegt unter einem spätassyrischen ein mittelassyrischer Komplex, der verschiedenen Anzeichen zufolge zum Palast Tukulti-Ninurtas I. zu gehören scheint. Er spricht dafür, daß sich die Anlagen des Nordpalastes in nördlicher Richtung wesentlich weiter ausdehnten, als man bisher annahm. Ferner wurde weit außerhalb der vermuteten nördlichen Stadtbegrenzung eine Erhebung (Teil O) untersucht, in der ein kleiner assyrischer Langraumtempel nachgewiesen werden konnte.

Nach den Ergebnissen der letzten beiden Kampagnen formulierten die Ausgräber ihre Vorstellungen von den noch zu

leistenden Untersuchungen in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta: «Problematisch, aber nicht uninteressant wäre eine partielle Freilegung des Hauptraumes des Nordpalastes, der noch unergraben und massiv ansteht, denn in diesem Teil sind vielleicht nicht nur Wandmalereien zu erwarten. Der Südpalastteil dagegen ist nur schwer anzugehen, da der gesamte Komplex stark erodiert ist.»42 Ähnlich skeptisch in Hinsicht auf den gegenwärtigen Zustand der Stadtanlage äußert sich Dittmann in einem weiteren Vorbericht: «Obgleich Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta flächenmäßig immer größer wird, ist das, was die rezenten landwirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten von der Ruine übriggelassen haben, erschütternd gering. Dies wenige in repräsentativem Umfang auszugraben, wird die Aufgabe der nächsten Kampagnen sein.»43

Unberührt von dem Befund, daß in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta auch reichliche neu-und nachassyrische Besiedlungsspuren vorliegen und sich dieser Sachverhalt für die neuassyrische Zeit in den keilschriftlichen Quellen zu bestätigen scheint, bleibt die Tatsache, daß der Ort nur während jener einen Regierungszeit Residenz war. Das verleiht ihm seine historische Bedeutung, während das schon von Walter Bachmann festgestellte nahezu völlige Fehlen von Kleinfunden im Assur-Tem-pel und auch dessen zugemauerte Türen deutlich auf eine bewußte Auflassung der offiziellen Gebäude hinzuweisen scheinen. Nicht zuletzt daher rührt das spezielle archäologische Interesse, das diese Stadtanlage nach wie vor erweckt.

http://www.orient-gesellschaft.de/forschungen/projekt.php?p=9

Photographs presented by Prof. Pittman: http://www.arthistory.upenn.edu/spr03/422/April3/422April3.html

S. Kalyanaraman, Ph.D.

Sarasvati Research Center

December 26, 2013

.jpg/285px-Flickr_-_The_U.S._Army_-_www.Army.mil_(218).jpg)