Wall painting, fragment, found at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta in Mesopotamia, Assyrian. The hieroglyph is 'safflower'. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Assyrian_painting.JPG

Wall painting, fragment, found at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta in Mesopotamia, Assyrian. The hieroglyph is 'safflower'. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Assyrian_painting.JPGAllograph: करडी [ karaḍī ] f (See

Rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy' of arka 'copper'.

Photograph of excavation site. Shows three culd stands in situ in Room 6 of Ishtar temple of Tukulti-Ninurta I at Ashur. Courtesy: Vorderaslatisches Museum.

Andrae, 1935, 57-76, pls. 12, 30 1. Jakob-Rust, in Vorderaslatisches Museum 1992, 160, no. 103; Andrae, 1935, 16, figs. 2,3.

करंडा [karaṇḍā] A clump, chump, or block of wood. 4 The stock or fixed portion of the staff of the large leaf-covered summerhead or umbrella. करांडा [ karāṇḍā ] m C A cylindrical piece as sawn or chopped off the trunk or a bough of a tree; a clump, chump, or block.

Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda)

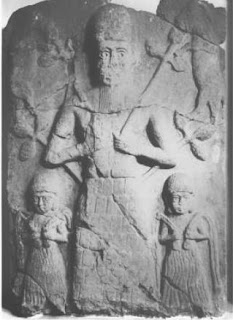

[quote]Description: Although the cult pedestal of the Middle Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta mentions in its short inscription that it is dedicated to the god Nuska, the relief on the front that depicts the king in a rare kind of narrative, standing and kneeling in front of the very same pedestal was frequently discussed by art-historians. More strikingly on top of the depicted pedestal there is not the lamp, the usual divine symbol for the god Nuska, but most likely the representation of a tablet and a stylus, symbols for the god Nabû. (Klaus Wagensonner, University of Oxford)[unquote] http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=pedestal_tukulti_ninurta

No, it is not a representation of a tablet and a stylus, but a chump, a block of wood, karaṇḍā read rebus: karandi 'fire-god' (Munda). Thus, the chump is the divine symbol of fire-god.

Another prayer by Tukulti-Ninurta on a fire-altar:

Altar, offered by Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243-1208 BC, in prayer before two deities carrying wooden standards, Assyria, Bronze AgeSource: http://www.dijitalimaj.com/alamyDetail.aspx?img=%7BA5C441A3-C178-489B-8989-887807B57344%7D

Another view of the fire-altar pedestal of Tukulti-Ninurta I, Ishtar temple, Assur. Shows the king standing flanked by two standard-bearers; the standard has a spoked-wheel hieroglyph on the top of the staffs and also on the volutes of the altar frieze.The mediation with deities by king is adopted by Assurnasirpal II.

The two standards (staffs) are topped by a spoked wheel. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'bronze'. cf. erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) Glyph: eraka

This rebus reading is consistent with the prayer offered to

the karaṇḍa 'hard alloy'.

‘alloy’. Allograph: khū̃ṭ ‘zebu’.

Glyphic element: erako nave; era = knave of wheel. Glyphic element: āra ‘spokes’. Rebus: āra ‘brass’ as in ārakūṭa (Skt.) Rebus: Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt (DEDR 866) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Glyphic element: kund opening in the nave or hub of a wheel to admit the axle (Santali) Rebus: kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295).

The same spoked-wheel hieroglyph adorns the Dholavira Sign-board.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/08/dholavira-gateway-to-meluhha-gateway-to.html?q=dholavira+sign

(After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Ashur temple at Ashur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)

(After Fig. 17. Cult relief found in a well located in the Ashur temple at Ashur. Old Assyrian period, early 2nd millennium BCE, limestone, h. 52 ½ in. (1.36in) Vorderasiatisches Museum.)lo ‘pot to overflow’ kāṇḍa ‘water’. Rebus: lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ (Marathi).

<kanda> {N} ``large earthen water ^pot kept and filled at the house''. @1507. #14261. (Munda) Rebus: khanda ‘a trench used as a fireplace when cooking has to be done for a large number of people’ (Santali) kand ‘fire-altar’ (Santali)

దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala -- n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} ``^branch, ^twig''. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen', ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig', Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree', ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it', So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch', H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala -- n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} ``^branch, ^twig''. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen', ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig', Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree', ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it', So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch', H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

Fragments from a large stone vessel dted to ca. second millennium BCE, were reconstucted. Two caprids identified as ibexes are seen eating from a three-lobed, stylized plant,

comparable to the relief shown on Fig. 17. In the second register, a bull-man and a bearded man hold a standard crowned by a crescent moon and an eight-pointed star. Behind the bull-man is a fabulous creature perhaps with a lion's head and wings.

Composite drawing of imagery on cat. no. 44. Original drawing by Katrin Hinz, redrawn by J. Ganem. (After Fig. 16 in Harper Prudence Oliver, ed., 1995, Assyrian origins: discoveries at Ashur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 63

Two ibexes read rebus: miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.)

kūdī‘twig’ Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’. The two ibexes + twig hieroglyhs, thus, connote a metal merchant/artisan with a smelter.

Lion: aryeh‘lion’ Rebus: arā‘brass’.

Bull: ḍangar Rebus: dhangar‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍangar‘blacksmith’(Hindi)

![]() Drawing of a seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig. 131; After Fig. 29 in Harper opcit.)

Drawing of a seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig. 131; After Fig. 29 in Harper opcit.)

Drawing of a seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig. 131; After Fig. 29 in Harper opcit.)

Drawing of a seal impression on cat. no. 68. Reproduced from Andrae 1977, fig. 131; After Fig. 29 in Harper opcit.)Ram-fish hieroglyphs: Tagara ‘ram’ + ayo ‘fish’; rebus: tagara ‘tin’, ayo ‘metal’ (perhaps bronze formed by alloying copper mineral with tin mineral). (For the altar as a hieroglyph, see discussion on Tukulti-Ninurta fire-altar reading rebus the representation of fire-god). Thus, the composition is seen as a metallurgist's smithy viewed as a temple.

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta north of Assur had a temple complex on the left bank of River Tigris. On the wetern side was a ziggurat which had a tablet identifying the temple of Ashur with the image of the deity moved from Assur. North of the temple was a palace placed on a platform originally 18m. high. The decorated wall painting fragment is from the palace.

Stone figure of a monkey from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.

· Monkey Ta. kōṭaram monkey. Ir. kōḍa (small) monkey; kūḍag monkey. Ko. ko·ṛṇ small monkey. To. kwṛṇ monkey. Ka. kōḍaga monkey, ape. Koḍ. ko·ḍë monkey. Tu. koḍañji, koḍañja, koḍaṅgů baboon. (DEDR 2196). kuṭhāru = a monkey (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker), also an inscriber or writer.

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was first excavated from 1913 to 1914 by a German team from the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Company) led by Walter Bachmann which was working at the same time at Assur. The finds are now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, in the British Museum and in Istanbul. Bachmann did not publish his results and his field notes were lost. A full excavation report appeared only in 1985. Work at the site was resumed in 1986 with a survey by a team from the German Research Foundation led by R. Dittman. A season of excavation was conducted in 1989. (R. Dittman, Ausgrabungen der Freien Universitat Berlin in Assur und Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta in den Jahren 1986-89, MDOG, vol. 122, pp. 157-171, 1990) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kar-Tukulti-NinurtaStone statue of a monkey

Middle Assyrian, about 1243-1207 BCE

From Kar Tukulti Ninurta, northern Iraq

Monkeys were not native to Mesopotamia and would have been imported, probably from Africa or India. Mesopotamian kings prided themselves on the collections of exotic animals they acquired as booty or tribute, and the most 'exotic' were sometimes commemorated in stone. Monkeys were popular animals in Mesopotamian art; they are often depicted playing musical instruments, perhaps representing animals accompanying travelling entertainers.

This statue, broken in three pieces, was found in 1914 in a palace at the site of Kar Tukulti-Ninurta in the kingdom of Assyria. This city was a new foundation by King Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243-1207 BC) and included a number of palaces and temples decorated with elaborate wall paintings. Tukulti-Ninurta conquered Babylonia and much of north Mesopotamia, during his reign, but towards the end he was imprisoned in the new city by his son, Ashur-nadin-apli (1206-1203 BC), and all his military achievements came to nothing.

A. Khurt, The ancient Near East c. 3000- (London, Routledge, 1995)

A. Spycket, '"Le carnaval des animaux": on some musician monkeys from the ancient Near East', Iraq-8, 60 (1998), pp. 1-10

T. Eickhoff, Kar Tukulti Ninurta. Eine Mitt (Berlin, 1985)

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/s/stone_statue_of_a_monkey.aspx

See: Karen Radner, Eleanor Robson, 2011, The Oxford book of cuneiform culture, Oxford University Press http://tinyurl.com/q67vydx

Three artefacts with Indus writing are remarkable for their definitive intent to broadcast the metallurgical message: 1. Dholavira signboard on a gateway; 2. Shahdad standard; and 3. Tablets showing processions of three standards: scarf hieroglyph, one-horned young bull hieroglyph and standard-device hieroglyph. Rebus readings of the inscriptions relate to and document the metallurgical competence of Meluhhan lapidaries-artisans. Some other select set of inscriptions from the wide, expansive area stretching from Haifa to Rakhigarhi, from Altyn Depe (Caucus) to Daimabad (Maharashtra) are presented to show the area which had evidenced the use of Meluhha (Mleccha) language of Indian sprachbund.

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations,harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations,harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Segment 1: Working in ore, molten cast copper, lathe (work)

ḍato ‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu ‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍaren lid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼ Rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A. kundār, B. kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H. kũderā m. ‘one who works a lathe, one who scrapes’, rī f., kũdernā ‘to scrape, plane, round on a lathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण [ kōndaṇa ] n (कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার [ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver. খোদকারি n. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work. খোদাই [ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving. খোদাই করা v. to engrave; to carve. খোদানো v. & n. en graving; carving. খোদিত [ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

loa ’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaḍha 'ficus religiosa' (Skt.); kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

khuṇṭa 'peg’; khũṭi = pin (M.) rebus: kuṭi= furnace (Santali) kūṭa ‘workshop’ kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).