Ha-Joon Chang, one of the last surviving independent economists at Keynes's Cambridge: 'The supporters of neoclassical economics have an almost religious mentality.' Photograph: Sean Smith for the Guardian

From any rational point of view, orthodox economics is in serious trouble. Its champions not only failed to foresee the greatest crash for 80 years, but insisted such crises were a thing of the past. More than that, some of its leading lights played a key role in designing the disastrous financial derivatives that helped trigger the meltdown in the first place.

Plenty were paid propagandists for the banks and hedge funds that tipped us off their speculative cliff. Acclaimed figures in a discipline that claims to be scientific hailed a "great moderation" of market volatility in the runup to an explosion of unprecedented volatility. Others, such as the Nobel prizewinner Robert Lucas, insisted that economics had solved the "central problem of depression prevention".

Any other profession that had proved so spectacularly wrong and caused such devastation would surely be in disgrace. You might even imagine the free-market economists who dominate our universities and advise governments and banks would be rethinking their theories and considering alternatives.

After all, the large majority of economists who predicted the crisisrejected the dominant neoclassical thinking: from Dean Baker and Steve Keen to Ann Pettifor, Paul Krugman and David Harvey. Whether Keynesians, post-Keynesians or Marxists, none accepted the neoliberal ideology that had held sway for 30 years; and all understood that, contrary to orthodoxy, deregulated markets don't tend towards equilibrium but deepen the economy's tendency to systemic crisis.

Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve and high priest of deregulation, at least had the honesty to admit his view of the world had been proved "not right". The same cannot be said for others. Eugene Fama, architect of the "efficient markets hypothesis" underpinning financial deregulation, concedes he doesn't know what "causes recessions" – but insists his theory has been vindicated anyway. Most mainstream economists have carried on as if nothing had happened.

Many of their students, though, have had enough. A revolt against the orthodoxy has been smouldering for years and now seems to have gone critical. Fed up with parallel universe theories that have little to say about the world they're interested in, students at Manchester University have set up a post-crash economics society with 800 members, demanding an end to monolithic neoclassical courses and the introduction of a pluralist curriculum.

They want other schools of economic thought taught in parallel, from Keynesian to more radical theories – with a better record on predicting and connecting with the real world economy – along with green and feminist economics. The campaign is spreading fast: to Cambridge, Essex, the London School of Economics and a dozen other campuses, and linking up with university groups in France, Germany, Slovenia and Chile.

As one of the Manchester society's founders, Zach Ward-Perkins, explains, he and a fellow student agreed after a year of orthodoxy: "There must be more to it than this." Neoclassical economics is after all built on a conception of the economy as the sum of the atomised actions of millions of utility-maximising individuals, where markets are stable, information is perfect, capital and labour are equals – and the trade cycle is bolted on as an afterthought.

But even if it struggles to say anything meaningful about crises, inequality or ownership, the mathematical modelling erected on its half-baked intellectual foundations give it a veneer of scientific rigour, valued by students aiming for well-paid City jobs. Neoclassical economics has also provided the underpinning for the diet of deregulated markets, privatisation, low taxes on the wealthy and free trade we were told for 30 years was now the only route to prosperity.

Its supporters have an "almost religious mentality", as Ha-Joon Chang – one of the last surviving independent economists at Keynes's Cambridge – puts it. Although claiming to favour competition, the neoclassicals won't tolerate any themselves. Forty years ago, most economics departments were Keynesian and neoclassical economics was derided. That allchanged with the Thatcher and Reagan ascendancy.

In institutions supposed to foster debate, non-neoclassical economistshave been systematically purged from economics faculties. Some have found refuge in business schools, development studies and geography departments. In the US, corporate funding has been key. In Britain, peer review through the "research excellence framework"– which allocates public research funding – has been the main mechanism for the ideological cleansing of economics.

Paradoxically, the sharp increase in student fees and the marketisation of higher education is creating a pressure point for students out to overturn this intellectual monoculture. The free marketeers are now being market-tested, and the customers don't want their product. Some mainstream academics realise that they may have to compromise, and have been colonising a Soros-funded project to overhaul the curriculum, hoping to limit the scale of change.

But change it must. The free-market orthodoxy of the past three decades not only helped create the crisis we're living through, but gave credibility to policies that have led to slower growth, deeper inequality, greater insecurity and environmental degradation all over the world. Its continued dominance after the crash, like the neoliberal model it underpins, is about power not credibility. If we are to escape this crisis, both will have to go.

Twitter: @SeumasMilne

[quote]In one of the world's elite institutions, the elites were taking a pasting – from accountants, entrepreneurs and academics. They knew what they were on about, too. Given his turn on the mic, one biologist said: "I'll believe economists have reformed when the men behind Black and Scholes [the theory that helps traders value financial derivatives] have been stripped of their Nobel prizes." [unquote]

Options Pricing: Black-Scholes Model

The Black-Scholes model for calculating the premium of an option was introduced in 1973 in a paper entitled, "The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities" published in the Journal of Political Economy. The formula, developed by three economists – Fischer Black, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton – is perhaps the world's most well-known options pricing model. Black passed away two years before Scholes and Merton were awarded the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics for their work in finding a new method to determine the value of derivatives (the Nobel Prize is not given posthumously; however, the Nobel committee acknowledged Black's role in the Black-Scholes model).

The Black-Scholes model is used to calculate the theoretical price of European put and call options, ignoring any dividends paid during the option's lifetime. While the original Black-Scholes model did not take into consideration the effects of dividends paid during the life of the option, the model can be adapted to account for dividends by determining the ex-dividend date value of the underlying stock.

The model makes certain assumptions, including:

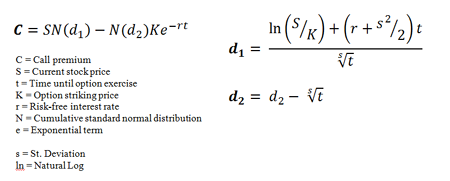

The model is essentially divided into two parts: the first part, SN(d1), multiplies the price by the change in the call premium in relation to a change in the underlying price. This part of the formula shows the expected benefit of purchasing the underlying outright. The second part, N(d2)Ke^(-rt), provides the current value of paying the exercise price upon expiration (remember, the Black-Scholes model applies to European options that are exercisable only on expiration day). The value of the option is calculated by taking the difference between the two parts, as shown in the equation.

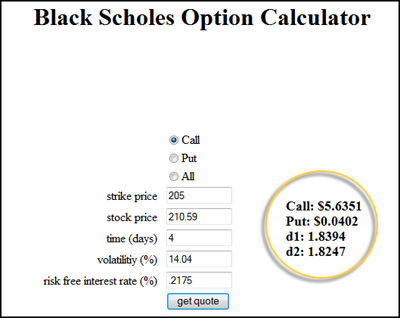

The mathematics involved in the formula is complicated and can be intimidating. Fortunately, however, traders and investors do not need to know or even understand the math to apply Black-Scholes modeling in their own strategies. As mentioned previously, options traders have access to a variety of online options calculators and many of today's trading platforms boast robust options analysis tools, including indicators and spreadsheets that perform the calculations and output the options pricing values. An example of an online Black-Scholes calculator is shown in Figure 5; the user must input all five variables (strike price, stock price, time (days), volatility and risk free interest rate).

The Black-Scholes model is used to calculate the theoretical price of European put and call options, ignoring any dividends paid during the option's lifetime. While the original Black-Scholes model did not take into consideration the effects of dividends paid during the life of the option, the model can be adapted to account for dividends by determining the ex-dividend date value of the underlying stock.

The model makes certain assumptions, including:

- The options are European and can only be exercised at expiration

- No dividends are paid out during the life of the option

- Efficient markets (i.e., market movements cannot be predicted)

- No commissions

- The risk-free rate and volatility of the underlying are known and constant

- Follows a lognormal distribution; that is, returns on the underlying are normally distributed.

- Current underlying price

- Options strike price

- Time until expiration, expressed as a percent of a year

- Implied volatility

- Risk-free interest rates

|

| Figure 4: The Black-Scholes pricing formula for call options. |

The model is essentially divided into two parts: the first part, SN(d1), multiplies the price by the change in the call premium in relation to a change in the underlying price. This part of the formula shows the expected benefit of purchasing the underlying outright. The second part, N(d2)Ke^(-rt), provides the current value of paying the exercise price upon expiration (remember, the Black-Scholes model applies to European options that are exercisable only on expiration day). The value of the option is calculated by taking the difference between the two parts, as shown in the equation.

The mathematics involved in the formula is complicated and can be intimidating. Fortunately, however, traders and investors do not need to know or even understand the math to apply Black-Scholes modeling in their own strategies. As mentioned previously, options traders have access to a variety of online options calculators and many of today's trading platforms boast robust options analysis tools, including indicators and spreadsheets that perform the calculations and output the options pricing values. An example of an online Black-Scholes calculator is shown in Figure 5; the user must input all five variables (strike price, stock price, time (days), volatility and risk free interest rate).

|

| Figure 5: An online Black-Scholes calculator can be used to get values for both calls and puts. Users must enter the required fields and the calculator does the rest. Calculator courtesy www.tradingtoday.com http://www.investopedia.com/university/options-pricing/black-scholes-model.asp |