Image may be NSFW.

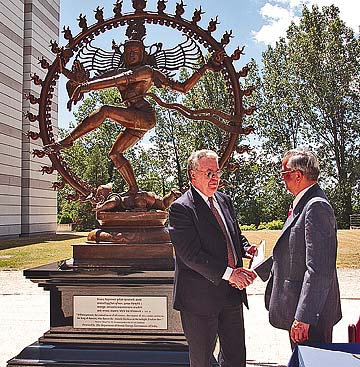

Clik here to view. Nataraja at CERN, European Organization for Nuclear Research, Switzerland’s pre-eminent center of research into energy, the “world’s largest particle physics laboratory” and the place where core technologies of the internet were first conceived — “where the web was born.”

Nataraja at CERN, European Organization for Nuclear Research, Switzerland’s pre-eminent center of research into energy, the “world’s largest particle physics laboratory” and the place where core technologies of the internet were first conceived — “where the web was born.”

Clik here to view.

Nataraja at CERN, European Organization for Nuclear Research, Switzerland’s pre-eminent center of research into energy, the “world’s largest particle physics laboratory” and the place where core technologies of the internet were first conceived — “where the web was born.”

Nataraja at CERN, European Organization for Nuclear Research, Switzerland’s pre-eminent center of research into energy, the “world’s largest particle physics laboratory” and the place where core technologies of the internet were first conceived — “where the web was born.”Brilliant, scintillating arguments by Dr. Subramanian Swamy; a significant contribution to Indian jurisprudence -- in.the cosmic dance, Tandava nrityam of Tillai Nataraja.

Kalyanaraman

WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS:IN NATARAJA TEMPLE CASE

SLP(C) No.30278 of 2009 on November 28, 2013

I. PRELIMINARIES

1. This SLP No. 30278 of 2009 [Vol I, p.56-75] is against the 2009 DB judgment of MHC dt.15.09.09 [Vol I, p. 214-68] on Writ Appeal WA No.181 filed by Respondent 3 [Sri Sabhanayagar Temple] was dismissed. I was an Impleaded Party in the said WA.

2. The Counter of the State of Tamil Nadu, i.e., Respondent No. 1, is on p. 280-347. My Rejoinder Affidavit is on p.394-448 [the nature of the temple is at p 396, para 3].

3. Prayer is on p.7. I submit for your Lordships two propositions for allowing my SLP and quashing the G.O. issued in 2006 by the Government of Tamil Nadu [Respondent] for the take over the administration of the Sri Sabhanayagar Temple, otherwise known as Nataraja Temple in the town of Chidambaram.

II. CAUSE OF ACTION

1. Respondent No.1 had issued a G.O. No. 168 in 2006 approving Commissioner’s earlier Orders dated 5.8.87[p.124] and 31.07.1987{Hand in Commissioner’s Order}.

2. This G.O. notified the approval of TN government of the appointment of an E.O. u/s 45(2) of HR&CE Act (1959) [ Vol II, p.126-32] to “go and takeover the temple”

3. In the those orders, Section 45 of the re-enacted HR&CE Act of 1959 was invoked, and because of alleged [and admittedlyunproven mismanagement] of the Podu Dikshidars, an E.O. appointed and asked to “proceed to Chidambaram at once to take charge of the temple and its properties etc. without any delay” [SLP Vol., p.124].

4. Presently [vide Counter of Respondent No.1 at p.303], the “Arulmigu Sabhanayagar Temple, Chidambaram, is under the control of the HR&CE Department.”

5. But this exercise of “control” is now subject to an interim Order of this Hon’ble Court passed on March 15, 2010 wherein the EO is restrained from carrying out any major construction, barring simple repairs, or demolition work.

4. First proposition is that the impugned G.O. is completely vitiated by Res Judicata and hence is null and void.

5. Second proposition is that Section 45 of the TN HR&CE Act under which the Respondent No.1 claims authority to issue the G.O. is ultra vires Article 31A(1) (b) of the Constitution[ Rejoinder of this Petitioner p. 412-13].

III. RES JUDICATA ARGUMENT

1. The first attempt after Independence to bring the temple administration under State control was vide Notification No. G.O. Ms. 894 dated 28-8-1951 in which G.O. several charges of mismanagement and misappropriation were made against the PDs.

2. This G.O. was challenged by the PDs before the DB of MHC and a judgment was delivered on the matter in the Shirur Mutt case [CV-I, p. 1-50].

3. The Hon’ble DB quashed the said G.O. holding the PDs to be a “religious denomination” [Vol-II, p.94&118] and hence as laid down under Article 26 of the Constitution, have a fundamental right to administer such property in accordance with law.

4. Such a law cannot be TN HR&CE Act vide Section 107 of the said Act.

5. It is an admitted position [e.g., in WP 544 of 2009 in this Hon’ble Court, para 12 states that “ …Section 107 of the [HR&CE] Act specifically bars the application of the Act to institutions coming under the purview of or enjoying the protection of Article 26 of the Constitution of India.”

6. It further adds for emphasis that: “In all cases where

Article 26 comes in, Section 45 would automatically go out”. This is repeated in Counter to an IA in the same WP.

7. At present in fact there is no law other than the IPC to address misappropriation of funds of a temple administered by a denomination.

8. Hence, the crucial question is if Article 26 can be invoked for the PDs and the temple. It can as I will show that it became a settled issue that the Podu Dikshidars are a religious denomination.

9. In 1953, this judgment was challenged by the same Respondents herein, by way of a SLP filed in this Hon’ble Court, and was heard before a Constitutional Bench as CA No.39 of 1953. HAND IT STATEMENT OF CASE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT

10. In para 33.1& 33.2 of the said Appeal, the Appellant TN Government, had challenged the Shirur Mutt case Division Bench judgment of the MHC.

11. TheCA was dismissed by a Speaking Order of the Hon’ble Constitutional Bench [Vol II, p.119-23]. The Respondent herein as Appellant earlier had given an undertaking to withdraw the impugned G.O.

12. The said DB judgment of the Madras High Court [V-II, p.76-95; and 119] thus became final in 1954 when the CA No.39 of 1953 filed by the Madras government against the DB judgment, was dismissed by a Constitutional Bench of this Hon’ble Court [Vol-II, p.119-123].

13. TheCA was dismissed by a Speaking Order of the Hon’ble Constitutional Bench [Vol II, p.119-23]. The Respondent herein as Appellant earlier had given an undertaking to withdraw the impugned G.O.

14. The said DB judgment of the Madras High Court [V-II, p.76-95; and 119] thus became final in 1954 when the CA No.39 of 1953 filed by the Madras government against the DB judgment, was dismissed by a Constitutional Bench of this Hon’ble Court [Vol-II, p.119-123].

15. Hence any legal challenge to the denominational status of the PDs, since then, is ab initio void and barred as Res Judicata.

16. However, disregarding the bar of Res Judicata, the TN government made a second attempt after 52 years, and issued G.O. 168 of 2006 to take-over temple administration [Vol II, p.133-50].

17. This G.O. was challenged by the PDs inter alia, on the ground of Res judicata in Writ Petition WP No. 18248 of 2006, and heard by a Single Judge Bench[Vol II p. 162, paras 8, 9-14; PDs logic on p. 166 paras 20&24].

18. In that WP it was prayed that G.O.168 of 2006 [Vol II p.133-50] be quashed. The WP was dismissed.

19. This order of dismissal of the Hon’ble Single Judge was challenged before the Division Bench in a WA [SLP No.32111 of 2009 (SLP-2, p.300-16)].

20. In 2009, the Division Bench of the MHC in [Vol-I, p.1-55, p.241-42 at para 44-47] dismissed the WA.

21. Against this Order, SLP No. 30278 of 2009 [Vol I, p.56-75] has been filed by this Petitioner.

IV. TWO CONCEPTS

22. The first concept is of religious denomination.

23. The word “religious denomination” occurs in the Constitution [Article 26] but it is not defined therein.

24. In two HR&CE Acts of 1951 and 1959, and in subsequent amendments enacted by the TN Legislature, we also do not find any definition of “denomination”.

25. Religious denomination was defined in the said 1951 Shirur Mutt case [(1952) 1 MLJ 557; SLP p. 76-118; Citation Volume (CV)-I p. 1-50 at p.34-35] which draws on the Oxford Dictionary to define it as “a collection of individuals classed together under the same name: a religious sect or body having a common faith and organization and designated by a distinctive name”.

26. The Division Bench then held the Podhu Dikshidars [p. 601; CV-I p. 45] to be a ‘Religious Denomination’ with a clear finding that: “Looking at from the point of view, whether Podhu Dikshidars are a denomination and whether their right as a denomination is to any extent infringed within the meaning of Article 26 it seems to us that it is a clear case in which it can be safely said that the PDs who are Smartha Brahmins, form and constitute a religious denomination, or in any event, a section thereof.”

27. In a catena of judgments delivered after the Shirur Mutt judgment [e.g., Durgah Committee vs. Hussain Ali (1962) 1 SCR 383 at p. 410-412 para 3; Citation Vol I p.89-127], the definition of a religious denomination followed has remained the same.

28. In fact these judgments cite the Shirur Mutt case, covering the three main parameters: common faith, common organization, and a designation by a distinctive name. There is no difference therefore in the definition of denomination followed contrary to the view of the Hon’ble Single Judge in 2009.

29. Since the landmark MHC 1952 DB judgment in the Shirur Mutt case, and which was upheld by a constitutional bench of this Hon’ble Court, the Respondents Nos 1 and 2 herein have been respondents in a plethora of litigations against this temple in which this question arose, but they have always held, till 2009, that the PDs have been found by the Hon’ble Supreme Court to be a religious denomination.

30. In a writ petition filed by the Podu Dikshidars [WP 616/ 1981] against a fresh order of the Commissioner, HR&CE, Justice Mohan observed that the Respondents herein, did not pursue [in this Hon’ble Court] their averment against the denomination status of the PDs, which had been decided in favour of the PDs by the Hon’ble Division Bench in the Shirur Mutt case.

31. In the Counter filed in the Hon’ble MHC by the Respondent 2 [in W.P. 7843 of 1987], it is admitted in more than one place on oath that the Supreme Court “has found the Podhu Dikshidars at Chidambaram constitute a religious denomination”.

32. Hence judicially there can be no doubt whatsoever that PDs constitute a religious denomination to attract the protection of Article 26 of the Constitution.

33. We may refer to the SLP [in Vol.I at p.56; Grounds on p. 59-68] for this Hon’ble Court’s judgment in the Shirur Mutt’s case [p. 61-64 Ground B] wherein three paras of the Shirur Mutt’s judgment [1954) SCR 1005 at 1023-24] are extracted.

34. in the impugned MHC Single Judge and Division Bench judgments a bald and untenable distinction was made between the concepts of “religious denomination” and “denominational temple”.

35. This is without any precedent or merit. The former concept in fact encompasses the latter. The Respondents appear to have adopted this presumed erroneous dichotomy before Your Lordships here, as a desperate and futile attempt to circumvent the bar of res judicata.

36. Thus the Hon’ble Division Bench in 2009 wrongly held that [ SLP p.237, para 37]: “This observation [of the PDs being a religious denomination], by itself, cannot be regarded as a finding recorded on the issue as to whether the temple is a denominational temple. That issue was not directly and substantially in issue in the Shirur Mutt case”.

37. Respondent No.1 in the Counter in my SLP herein for the first time [starts at p.280; then p.282-83 p. 399-403] has stated that: “Hon’ble High Court has decided the religious denomination of Podhu Dikshidars alone in the above case in (1952) 1 MLJ 557[p. 399 SLP].Read my reply SLP p. 394-448 esp. p.399.

38. In may be noted at this stage that the PDs are held not only as a mere ‘denomination’ but in fact a ‘religious denomination’ because they not only satisfy the criteria of the Oxford dictionary to be a denomination, but a close reading of the Shirur Mutt judgment points to their founding and managing of the Sri Sabhanayagar temple.

39. In the said impugned judgment, the Hon’ble Division Bench had also examined the question of founding and management of the Sri Sabhanayagar Temple [CV-I p.41-2] which are relevant here for notice. It is an admitted position that the SST is a hoary temple whose origin is lost in antiquity.

40. Under the HRE Act of 1927, under which Act there was a proviso for a Board which was empowered to appoint a E.O. subject, of course, to Government approval.

41. The President of the Board, Mr. T.M.Chinnaiya Pillai, in his Inspection Note dated March 31, 1946 for the Board Meeting held on 19.12.1946, stated [see lines 35, 36 &37 of the Note]: “I have no quarrel on the claim of the Podu Dikshidars that they are hereditary trustees of this temple and that the temple came into existence because of the efforts of their ancestors.”

42. This Note and subsequent developments are referred to in para 11 of CA 39 of 1953 of the Respondent No.1 herein.

43. The Notification of the temple by the said Board, vide Notice No. 5 of 1947 u/s 65A of the 1927 Act dated 11.8.47 though issued, was withdrawn by G.O. No.440 dated 7.2.48 by the government.

44. Even if there is no written document proving that the temple was established by the Dikshidars, with Lord Nataraja as one of the Dikshidars, it nevertheless stands as an undisputed article of faith with the Hindus. No other group in Chidambaram or elsewhere has laid claim to the temple.

45. In the Constitutional Bench judgment in Venkataramana Devaru v. State of Mysore [(1958) SCR 895; CV-II p. 221-48 at p. 232] this Hon’ble Court specifically defined a religious denomination of the Gowda Saraswat Brahmins “not as a mere denomination”, but “a sect associated with the foundation and maintenance of the Sri Venkataramana Temple.”

46. Consequently, a temple founded and managed by a religious denomination is by definition a denominational temple. The Respondents thus are making a distinction that is absurd.

47. Such a temple may or not be a public temple, or vice versa. In the Madurai Sourashtra Sabha case [(1971) 84 Law Weekly 86; SLP p.402-03] a DB of the MHC held: “Admittedly, there is no direct evidence that the temple in question belongs to the Sourashtra Hindu Community at Madurai as to when and by whom the said temple was constructed. It is significant that none of the other communities living in Madurai town had at any time chosen to lay claim to the suit temple as their own. It was also the case that the said temple was throughout maintained by the Sourashtra community. Under such circumstances, it is held that the suit temple must be held to be belonging to said community.”

48. The same view was expressed in the case of the Vellalar Samudaya temple [(1980) 2 MLJ 358: see my SLP p.399] herein it was held that: “Where there is no direct evidence…. The suit temple belongs to the said community”

49. In any case, Article 25(2)(b) requires every temple to be “substantially” open to the general Hindu public i.e., subject only to reasonable restrictions on the access permitted [Devaru case, op.cit.].

50. The Hon’ble Division Bench of the MHC also referred to a new HR&CE Act having being enacted in 1959 repealing the 1951 Act and hence, the Hon’ble Bench opined[p. 241-44; at para 46 p.242] that the matter of denomination has to be denovoconsidered.

51. This is contradicted by a Constitutional Bench judgment of this Hon’ble Court in the Pathak’s case [AIR 1978 SC 803 paras 24- 26, p. 815, CV-II at 342] . The Hon’ble Division Bench of MHC has not referred to as to why this judgment would not be applicable or binding or relevant in this matter.

52. I had filed Written Submissions before the Division Bench after my impleadment in which I had brought the Pathak judgment to the Hon’ble Bench’s attention. But I could not lead oral arguments because of the violence directed against me by sympathisers of the LTTE in open court while arguing the matter before their Lordships of the Hon’ble Division Bench.

53. The Report of Justice Sri Krishna Committee gives full facts of those sordid events.

54. This makes it necessary for this Petitioner to elaborate on the second concept --that of Res Judicata.

55. In [Gangai Vinayagar Temple v. Meenakashi Ammal [(2009) 9 SCC 757 at page 768 in para 81]it is held:

“81. Res judicata is an ancient doctrine of universal application and permeates every civilised system of jurisprudence. This doctrine encapsulates the basic principles in all judicial systems which provide that an earlier adjudication is conclusive on the same subject-matter between the same parties. The principles of res judicata reflect a wisdom that is for all time”].

56. The principle of Res Judicata has been further re-iterated by this Hon’ble Court [in (2010) 3 SCC 353 at 376 para 60].

57. In the classic: The Doctrine of Res Judicata [Butterworth, London, 1996]originally authored by G.Spencer Bower in 1924 and revised by Hon’ble Justice Handley of Australia, after a review of all English law cases, it is re-iterated that a final decision even if subsequently proven wrong is binding on the same issues and same parties, as Res Judicata [p.14].

58. Thus, the Hon’ble DB of the MHC in the Shirur Mutt case finding that the PDs are a religious denomination and entitled to the protection of Article 26, acts a bar of res judicata in all subsequent litigation between the same parties on the same issue, even if the laws have changed since, or the finding of the Court was erroneous.

59. I submit, in view of the cited judgments of this Hon’ble Court, any proceedings herein between the same parties and same issues under the HR&CE Act, is hit and barred by Res Judicata and the Sri Sabhanayagar Temple is protected by Article 26(c)&(d) of the Constitution because the PDs are a religious denomination.

V. THE CONCLUDING ARGUMENTS FOR THE TWO PROPOSITIONS

My submissions before Your Lordships are:

First, it is settled law since 1953, that the Podu Dikshidars constitute a religious denomination within the meaning and of Article 26 of the Constitution and hence entitled to the protection of the said fundamental right.

The impugned DB judgment of 2009 of the Hon’ble the Madras High Court, upholding the said G.O. 106, is therefore vitiated by Res Judicata and thus and ought to be set aside.

This prayer is further fortified since admittedly Section 45 is barred from application vide Section 107 of the HR&CE Act for a religious denomination protected by Article 26.

Under Article 26 [(2005) 6 SCC 166 at 171 para 19; CV-II p. 317-23 at p.322], the invoking of Section 45 against the Podhu Dikshidars and the Sri Sabanayagar Temple is thus not valid in law.

The G.O.No. 168 is sourced to the power vested in the Respondents vide Section 45, and hence it is infructuous. Thus the Notification is to be quashed.

Second, the take-over of temple properties comes under the purview of Article 31(A)(1)(b).

A judgment of a Seven Judge Constitutional Bench of this Hon’ble Court [reported in AIR 1969 SC 168 at 176, CV-II p. 388 at p. 400-01] and Karnataka [(1998) 2 Kar L.J 587 [DB] at p.609, para 38], Kerala, Punjab, and AP High Courts have clarified that the scope of “property” in that Article covers other items than estate or land. Temple lands and properties thus would come within the ambit of Art.31A(1)(b).

Period limitation was incorporated in Article 31A(1)(b) of the Constitution by way of the First Amendment in 1951, and before the HRE Act 1951, which therefore contained the five year limitation.

Significantly, the 1951 HRE Act in Section 64(4) [p. 454 in the Brief] had placed a limit of 5 years for a notification for take-over, to remain valid.

But for inexplicable reasons, in the 1959 HR&CE Act, it was replaced by Section 72 [p. 449-453] after deleting the period limitation.

Thus Section 45 acquisition besides being impermissible for Denominations vide Section 107 of the HR&CE Act of 1959, is also ultra vires Article 31A(1)(b) of the Constitution.

Third, it also is ultra vires Article 27 since the State is not constitutionally empowered to further or to derogate any religion, as well as the Preamble regarding state commitment to secularism.

Prolonged take-over of temples will for example require paying salaries and stipend to priests and archakas from State funds.

Since 1959, there is not a single instance of the Respondents returning to the trustees a taken over temple.

After an amendment to the Act in 1965, take-over and retention of a temple became a discretionary open-ended option for the Government vide Section 72(6) [p. 450] for to rescind or not to, the G.O..

The 1965 amendment now empowers the government to take-over temples even if there is no prima facie evidence of mismanagement. This is against case laws.

In fact it has been brazenly disclosed by the authorities that it is government policy to take-over temples [in Jyotiramalingam case, AIR 1985 Mad 341; CV-I p.69 at p.72-74].

There are today about 45,000 temples in the Respondents’ control most for over several decades, with no oversight agency to monitor the use or misuse of temple funds. Hand over a list.

In any case as held by the Constitutional Bench [op.cit.,], a mere discretion of the Government to return the property is not an acceptable answer.

Thus, if any take-over by government is without a period limit then it becomes ultra vires Art 31A(1)(b), if challenged as infringing Article 14 and/or 19 [here it can be under 19(g)].

The impugned G.O. No.168 is therefore not only ultra vires Article 26 which protects denominations, but also Article 31 A(1)(b) of the Constitution, since there is no indication in the text of the said G.O. that the acquisition of the management of the resources and properties of the said temple, is only for a limited period .

Fourth, the said G.O. has been issued without a completing a proper inquiry, in accordance with the judicially canonized rule of audi alteram partem. It is thus in violation of the principles of natural justice and therefore fit for quashing[p..].

Fifth,that the aforesaid G.O. was issued on the directions of political authorities, who are known for their bias against the Hindu religion in general and this temple in particular. Hence the said G.O. is vitiated as being malafide thus invalid.

Sixth, on grounds of natural justice. The impugned G.O. represents a gross non application of mind resulting in a failure of natural justice.

This Hon’ble Court has made clear [(2010) 7 SCC 678, para 23; CV-I 51 at p. 59-60] that application of mind is best demonstrated by disclosure of mind by the authority recording the reasons for making the order.

It is admitted by Respondent No.2 that the Commissioner’s order of 31.07.87 is based on allegations without proving their veracity beyond doubt [ Para 12 ].

In fact, the said order was issued even as the inquiry was ongoing. The impugned G.O. No. 168 of 2006 thus has been issued without application of mind.

In the counter-affidavit, the Respondent has stated [p.14 ] that “.. the legal position was that the Commissioner was at liberty to pass an order appointing an Executive Officer without a prior notice to anybody who may be interested in the temple.”

The 31.07.87 order of the Commissioner was the consequence of proceedings in WP 5638 of 1982 challenging the first Commissioner’s Order of 1982 to appoint an E.O..

Justice Mohan had explicitly directed that the 1982 Order would be treated just as a ‘Show Cause’ Notice of the Commissioner to the PDs, but that the final “orders of the Commissioner will be passed on merits.”

The specific direction of the Hon’ble Court to pass orders on merits was however recklessly flouted.

To do so, the Commissioner appears to have relied on a decision of Single Judge [reported in AIR 1976 Mad 264; CV-II p. 63-5].

This decision was however subsequently overruled by a Division Bench [reported in (1995) 2 LW 213; CV-II 102 at p. 106], but after the issuance of the Commissioner’s 1987 Order.

The Hon’ble Single Judge in 2009 therefore had upheld the order of appointment of an EO dated 31.07.87 by the Commissioner because 1976 decision was not overruled till 1995, and hence presumed to have held the ground in 1987.

But even if so, the 1995 Division Bench judgment was well before the impugned G.O. issued in 2006 by Respondent No. 1 herein in this SLP, approving the order of the Commissioner. But the government took no cognizance of the High Court order.

The Hon’ble Single Judge ought therefore have taken cognizance of this, and set aside the impugned G.O.

Moreover, even prior to 1995, there were two Division Bench judgments of the Madras High Court [AIR 1971 Mad 295; CV- I, p.66-68 at p.67—even prior to 1976 !] and [AIR 1985 Mad 341; CV- I, p.69-74 at p.71 ], and a Constitutional Bench judgment of this Hon’ble Court [(1965) 2 SCR 934; CV-I, p.75-88 at p. 85] that in ratio went against the cited 1976 decision of the Single Judge.

In the said Constitutional Bench it was held that in view of the finding that the Commissioner failed to establish any of the allegations against the trustees, hence no case was made out for the appointment of the EO.

This natural justice principle has been re-affirmed in another case by a Bench of Justices Sinha and Bhandari [(2007) 2 SCC 181 at 191; CV-II p. 411-32 at p.421] which squarely applies here.

Hence, both the HR&CE Commissioner and the Secretary of the Department of the TN government have shown a reckless disregard for legal precedents as also for Article 141 of the Constitution, and thus passed an order without application of mind-- thus vitiated by arbitrariness.

The impugned Division Bench judgment of 2009 thus also suffers a fatal infirmity on this score.

Seventh, this Hon’ble Court had already cautioned the HR&CE Department that to invoke the power under Article 25 and 26 of the Constitution, there have to be grave and substantive allegations of mismanagement by the temple trustees which are proven in an legally tenable procedure established on the principle of audi alteram partem.

Even today after this Hon’ble Court is seized of the matter this kind of atmosphere prevails as evidenced by the recent physical attempts by atheists such as Communists to storm the temple [see cuttings].

The G.O. No.53 of 2008 is another example of gross interference in religious affairs by the TN Government.

Finally, the eighthsubmission is of malafide. The prima facie basis for malafide can be discerned from the list of dates from which it can be seen that the HR&CE Dept, or its predecessors of the TN government, have been trying since 1931 to take over this temple.

This leads this petitioner to lead the argument of malafide intention of the Respondents, who are admittedly the representatives of atheists who are in the political authority, and hence answerable to them.

This authority has publicly declared that physical destruction of this temple in particular is an essential part of atheism and Tamil liberation to which the said authority publicly subscribes.

The Dravidian Movement which was originally inspired by British imperialists to oppose the Freedom movement adopted the British nefarious goal set by Macaulay to rubbish India’s ancient culture and religion. Atheism became the easy route to do so.

Thus blowing up temples was a central call of the movement and destroying of Hindu idols was another [see AIR 1958 SC 1032]. The Sri Sabhanayagar temple was singled out for blowing up by cannon firing to signal “Tamil liberation”.

Sanskrit slokas were another target and were placed against Tamil language. The singing of Tevaram and Tamil songs in the sanctum sanctorum[ see G.O.No.53 of 2008…] was a strategy for it

Physical threats to the Podu Dikshitars such as laying a siege [see enclosed Times of India cutting] was yet another way. Earlier their sacred thread by the cadres of the Dravidar Kazhagam[ a DMK ally] was another method to harass and demean the PDs.