http://www.outlookindia.com/peoplehome2.aspx?pid=14974&name=Goolam%20Essaji%20Vahanvati&author=Goolam%20Essaji%20Vahanvati

COVER STORY Is the AG guilty of contempt for denying knowledge of CBI’s report when he vetted it? ANURADHA RAMANMAGAZINE | MAY 13, 2013  COVER STORY Is the AG guilty of contempt for denying knowledge of CBI’s report when he vetted it? It is bad enough for the first law officer of the land to be dubbed an “inside man” by a political and current affairs magazine. The 13th Attorney General of the country, Goolam Essaji Vahanvati, required by the professional ethics of his office to keep the government at an arm’s length, was portrayed as a man quite comfortable with blurring the boundaries with the ruling class. He is also being accused of being close to one of the most powerful business tycoons in the country. Now he faces the embarrassing charge—levelled in an April 29 letter (see full text at outlookindia.com) by his own deputy, additional solicitor general (ASG) Harin P. Raval—of having vetted the CBI status report on the coal allocation scam. Not just that, the scrutiny of the report appeared to have been done in the presence of Union law minister Ashwani Kumar and the CBI. Despite this, the AG and ASG had said that they had no knowledge whatsoever of the report. The ASG had, in fact, said so in court on March 12. Admittedly, he was following the senior attorney general’s orders till his conscience jolted him into speaking otherwise.

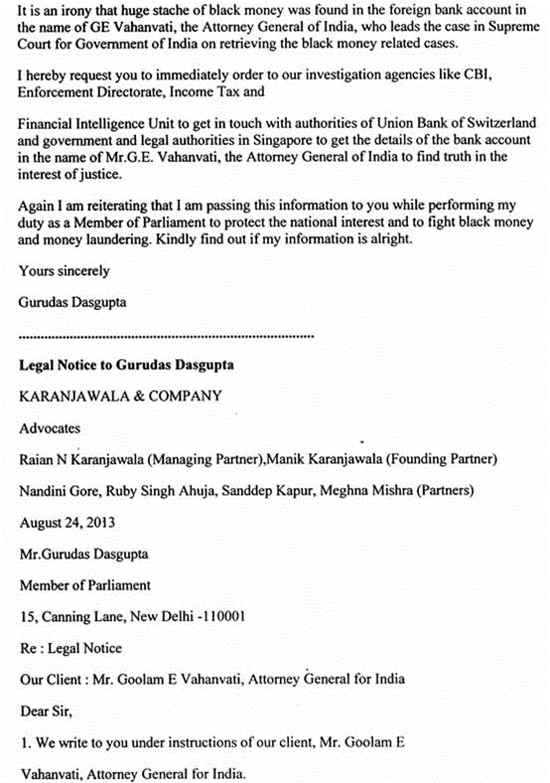

If Vahanvati did make the changes, not just once but nine times as is being alleged, and in his own handwriting, did he mislead the court when he said he had not seen the report? Media reportssuggest that Vahanvati is hurt by the allegations of his junior and continues to maintain that he does not have a copy of the status report. But if the country’s seniormost law officers are putting up untruths before a court, for whatever compelling reasons, does it not amount to perjury or contempt? Says senior advocatePrashant Bhushan, who has filed an application in court seeking an sit probe on the issue, “Both are at fault, but as Vahanvati is the senior officer, it would have been embarrassing for Raval to contradict him.” Bhushan firmly believes that what Raval has said in his letter is the closest to the truth in this unfortunate episode. For, at the heart of the matter is the fact that all the principal players—be it the CBI director, the law minister or the law officers—have admitted to having met each other. But, as a senior officer in the current regime says on condition of anonymity, it’s a disaster for the AG whose responsibility is to the court and not to the government. “It is unfortunate that the government has lowered the dignity of the office of the Attorney General of India.” Yet others point out that if the law minister summons the attorney general, he has no choice but to go under normal circumstances. In this instance, the problem lies in the fact that the AG is accused of having designed a cover-up for top members of the country’s executive. The court has now asked the CBI to file an affidavit citing the changes made in the coal allocation report. More bad news for the AG seems likely. FULL TEXT The full text of the letter by the Additional Solicitor General and CBI counsel in the coal scam case to Attorney General Goolam E Vahanvati accusing him of interfering in the CBI's case HARIN RAVALWEB | APR 29, 2013 Additional Solicitor General Shri Ghoolam E Vahanvati Esq29th April, 2013 Ld Attorney General for India 10, Motilal Nehru Marg New Delhi-110001 Learned Attorney General Sir, Sir, As a leader of Bar and our team of law officers, I had expected guidance from you sir, in discharge of my professional duties, not withstanding the fact that we deal matters entrusted to us independently. Having reflected upon what is being debated in public domain for a past couple of days and more particularly since the morning of last Friday, with a very heavy heart, I am constrained to address this letter to you to make the record straight and take the liberty of reminding you of the fact which are within your knowledge and of which the corroboration exists. The trigger point of this letter is the remark made by you to me, on Friday 26th April, 2013 inside the gentleman's cloak room of the second floor, when you asked me "Harin, why are you angry with me" and I politely replied to you. You further remarked that "You did not contradict me in court". Sir, you are aware that on the contrary, the truth is otherwise. It was I who did not contradict you in the court. You will kindly recall the sequence of facts during hearing that took place on 12th March, 2013 in respect of item No 11 in court 5. I had entered the court room little late as I was on legs before some other court. During the hearing when you were on your legs, certain queries were put to you on the basis of the facts stated in the status report filed by CBI in a sealed cover. You will also kindly recall that you had remained present even for mentioning on 8th March, 2013, when permission was sought for filing status report in a sealed cover instead of filing of an affidavit as per my statement recorded in the order dated 24 January, 2013. During the course of hearing when you are called upon to respond to certain paragraphs of the status report as regards the decision of government and the screening committee in the matter of allocation of coal blocks, you not only exhibited ignorance of facts stated in the status report which you had earlier perused, but had made a statement that what is stated in the status report was not to your knowledge and the same was not shared with the government. In fact, during the course of hearing, I was also called upon to show you those relevant paragraphs from the copy of status report that was made available to me during the course of hearing by the CBI officials instructing me in the matter. The same was shown to you in the court. The order dated 12 March, 2013 records a prayer made by you sir, for grant of some time to enable the government to file an additional affidavit on the aspects earlier not dealt with in the counter affidavit already filed. I am to further to request you to recall your memory that I was asked to attend a meeting in your presence with the Honorable Law Minister to consider whether the CBI should disclose the status of investigation on an affidavit in compliance of order dated 24 January or should a status report be filed. The meeting was attended by you sir, besides director CBI and Jt Director OP Galhotra amongst others. You will recall that I had reiterated my position namely that the statement made and recorded in the order dated 24 January to make known to the court the status of investigation through an affidavit of a competent officer was made not only after due consideration and discussion held with me by CBI officials on 23 January, 2013 prior to the hearing, but also on instruction received by me from them as well as instruction reiterated to me in the court. Having reiterated my stand, I was a silent spectator when a decision was taken to file a status report instead of an affidavit which was to be shown to you as was decided in the meeting. You will also kindly recall that on 6th March, 2013 while I was in court, I received a message from your end, asking me to see the Law Minister at 12.30 pm with the status report. The message received by me was forwarded to the Jt Director, CBI by me. You were also present when I reached slightly late. You would also kindly recall at the said meeting during the course of discussion the draft of only one of the status reports of one of the preliminary enquiry was shown to the Honorable Law Minister and was perused by him as well as by you. Certain suggestions were made, including by you, to the CBI, some of which were accepted. No suggestion emanated from me. You will kindly further recall that you wanted to leave to attend court for a mentioning matter, other status report of the investigation of 9 regular cases were requested by you to be shown to you in the evening at about 4.30 pm. I was also asked to be present at your residential office. After you left, I left shortly thereafter and I also had to attend a mentioning matter at 2 pm. In compliance of the above, the CBI officials brought the drafts which were perused and settled by you sir. I was present in your residential office. You had also asked me to mention the matter on 7th March which was not possible for me on account of personal reasons. The matter was mentioned on 8th March by me to seek permission to file status report in sealed cover. You had remained present during the mentioning. As a matter of fact, if my memory does not fail me, it was submitted by you that, the status report contains much more details than what could be known to the court by an affidavit to be filed in compliance of order dated 24 January. Despite the above facts while replying to the queries on 12 March as to what was contained in the status report, you had deemed it appropriate to take a stand that the contents of the status report were not known to you, which fact you knew to be incorrect. On account of your statement, I felt embarrassed and was forced to take a stand in the court consistent with your submission made as Attorney General for India that the contents of the status report were not known to you and that they were not shared with the government. It has constantly pained and anguished me that I have to face unnecessary indignation on account of your intolerant temperament towards conscientious discharge of duties especially in high profile cases. I have held you in high esteem as leader of our team but your flip flop attitude towards me has always put me under unnecessary pressure. I have retained a copy of this letter in my office for my record. I have also deemed it appropriate to simultaneity send a copy of this letter to Honorable Law Minister. I have a feeling that I am sought to be made scapegoat but I am confident that truth will always prevail. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, Harin P Raval | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)