Three artefacts with Indus writing are remarkable for their definitive intent to broadcast the metallurgical message: 1. Dholavira signboard on a gateway; 2. Shahdad standard; and 3. Tablets showing processions of three standards: scarf hieroglyph, one-horned young bull hieroglyph and standard-device hieroglyph. Rebus readings of the inscriptions relate to and document the metallurgical competence of Meluhhan lapidaries-artisans. Some other select set of inscriptions from the wide, expansive area stretching from Haifa to Rakhigarhi, from Altyn Depe (Caucus) to Daimabad (Maharashtra) are presented to show the area which had evidenced the use of Meluhha (Mleccha) language of Indian sprachbund.

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations, harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Hieroglyphs deployed on Indus inscriptions have had a lasting effect on the glyptic motifs used on hundreds of cylinder seals of the Meluhha contact regions. The glyptic motifs continued to be used as a logo-semantic writing system, together with cuneiform texts which used a logo-syllabic writing system, even after the use of complex tokens and bullae were discontinued to account for commodities. The Indus writing system of hieroglyphs read rebus matched the Bronze Age revolutionary imperative of minerals, metals and alloys produced as surplus to the requirements of the artisan communities and as available for the creation and sustenance of trade-networks to meet the demand for alloyed metal tools, weapons, pots and pans, apart from the supply of copper, tin metal ingots for use in the smithy of nations, harosheth hagoyim mentioned in the Old Testament (Judges). This term also explains the continuum of Aramaic script into the cognate kharoṣṭī 'blacksmith-lip' goya 'communities'.

Indus-Sarasvatī Signboard Text. Read rebus as Meluhha (Mleccha) announcement of metals repertoire of a smithy complex in the citadel. The 'spoked wheel' is the semantic divider of three segments of the broadcast message. Details of readings, from r. to l.:

Segment 1:Working in ore, molten cast copper, lathe (work)

ḍato‘claws or pincers of crab’ (Santali) rebus: dhatu‘ore’ (Santali)

eraka‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu). sangaḍa 'pair' Rebus: sangaḍa‘lathe’ (Gujarati)

Segment 2: Native metal tools, pots and pans, metalware, engraving (molten cast copper)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

aḍaren, ḍarenlid, cover (Santali) Rebus: aduru‘native metal’ (Ka.) aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Kannada) (Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ śāstri’s new interpretation of the Amarakośa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p. 330)

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu.Kōḍi corner;kōṇṭuangle, corner, crook.Nk. kōnṭacorner (DEDR 2054b) G.khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼRebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण[kōṇḍaṇa]fA fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’,kũdibā,kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur.Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295) A.kundār, B.kũdār, ri, Or.Kundāru; H.kũderā m. ‘one who works alathe, one who scrapes’,rīf.,kũdernā‘to scrape, plane, round on alathe’; kundakara—m. ‘turner’ (Skt.)(CDIAL 3297). कोंदण[ kōndaṇa ]n(कोंदणें) Setting or infixing of gems.(Marathi) খোদকার[ khōdakāra ] n an engraver; a carver.খোদকারিn. engraving; carving; interference in other’s work.খোদাই[ khōdāi ] n engraving; carving.খোদাই করাv. to engrave; to carve.খোদানোv. & n. en graving; carving.খোদিত[ khōdita ] a engraved. (Bengali) खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver. खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work. खोदणावळ [ khōdaṇāvaḷa ] f (खोदणें) The price or cost of sculpture or carving. खोदणी [ khōdaṇī ] f (Verbal of खोदणें) Digging, engraving &c. 2 fig. An exacting of money by importunity. V लाव, मांड. 3 An instrument to scoop out and cut flowers and figures from paper. 4 A goldsmith’s die. खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i ( H) To dig. 2 To engrave. खोद खोदून विचारणें or –पुसणें To question minutely and searchingly, to probe. खोदाई [ khōdāī ] f (H.) Price or cost of digging or of sculpture or carving. खोदींव [ khōdīṃva ] p of खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. (Marathi)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

loa’fig leaf; Rebus: loh ‘(copper) metal’ kamaḍha 'ficus religiosa' (Skt.); kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.); kampaṭṭam = mint (Ta.) The unique ligatures on the 'leaf' hieroglyph may be explained as a professional designation: loha-kāra 'metalsmith'; kāruvu [Skt.] n. 'An artist, artificer. An agent'.(Telugu).

khuṇṭa 'peg’; khũṭi = pin (M.) rebus: kuṭi= furnace (Santali) kūṭa ‘workshop’ kuṇḍamu ‘a pit for receiving and preserving consecrated fire’ (Te.) kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.)

eraka ‘knave of wheel’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Kannada) eraka ‘molten cast (metal)(Tulu).

Size matters. Archaeological context matters. How could one interpret the utility for the people of Dholavira, of 10 large glyphs (35 to 37 cm. high and 25 to 27 cm.wide) carefully laid out, in sequence, using gypsum pieces on an inscription which was a Signboard mounted on a gateway? Maybe, the Signboard text was visible from a distance for seafaring merchants and artisans from Dilmun or Magan or Elam. How can one assume it to be oral literature, for the guidance of tourists or merchants entering the citadel or even for the people of Dholavira (Kotda)? Why should any pundit conceive of the text, arbitrarily, to be non-linguistic? The glyphs are not randomly drawn but are repetitions from several tablets and seals which carry one or more of nearly 500 such distinct glyphs on nearly 7000 inscriptions of Indus writing. Why can't the glyphs be read rebus as hieroglyphs as a cypher code for the underlying sounds & semantics of words in Meluhha (Mleccha) language -- comparable to the rebus reading of N'r-M'r palette which used N'r 'cuttle-fish' and M'r 'awl' hieroglyphs to be read together as Narmer, the name of an Egyptian emperor?

One gateway had a signboard. "It is believed that the stone signboard was hung on a wooden plank in front of the gate. This could be the oldest signboard known to us," said Bisht. http://tinyurl.com/l3cszrr

Dholavira Signboard on GatewayThe citadel had two gateways: one on the northern and the other on the eastern side. Each gateway had an elaborate staircase. The landing of the staircase was at a depth of 2.3 m. After ten steps and a further descent of 2 m., the staircase led to a passage way which was 7 m. long On either side of the passage, there was a chamber which had a roof resting on stone pillars. In one of the chambers, a unique inscription was discovered. The ten letters of the inscription had a height of about 35 to 37 cm. and a width of 25 to 27 cm. The letters wee made of sliced pieces of some 'crystalline material, maybe rock, mineral or paste'. Perhaps mounted on a wooden board, the inscription might have constituted a sign-board. Ring-stones were used to support the pillars.

Dholavira Signboard on GatewayThe citadel had two gateways: one on the northern and the other on the eastern side. Each gateway had an elaborate staircase. The landing of the staircase was at a depth of 2.3 m. After ten steps and a further descent of 2 m., the staircase led to a passage way which was 7 m. long On either side of the passage, there was a chamber which had a roof resting on stone pillars. In one of the chambers, a unique inscription was discovered. The ten letters of the inscription had a height of about 35 to 37 cm. and a width of 25 to 27 cm. The letters wee made of sliced pieces of some 'crystalline material, maybe rock, mineral or paste'. Perhaps mounted on a wooden board, the inscription might have constituted a sign-board. Ring-stones were used to support the pillars.[quote] RS Bisht opined that the Harappans were a literate people. The commanding height at which the 10-sign board had been erected showed that it was meant to be read by all people.Besides, seals with Indus signs were found everywhere in the city – in the citadel, middle town, lower town, annexe, and so on. It meant a large majority of the people knew how to read and write. The Indus script had been found on pottery as well. Even children wrote on potsherds. Bisht said: “The argument that literacy was confined to a few people is not correct. You find inscriptions on pottery, bangles and even copper tools. This is not graffiti, which is child’s play. The finest things were available even to the lowest sections of society. The same seals, beads and pottery were found everywhere in the castle, bailey, the middle town and the lower town of the settlement at Dholavira, as if the entire population had wealth. [unquote] http://varnam.nationalinterest.in/2010/06/the-sign-board-at-dholavira/

The Dholavira Gateway Signboard text is perhaps the world's first advertisement hoarding by any artisan or merchant.

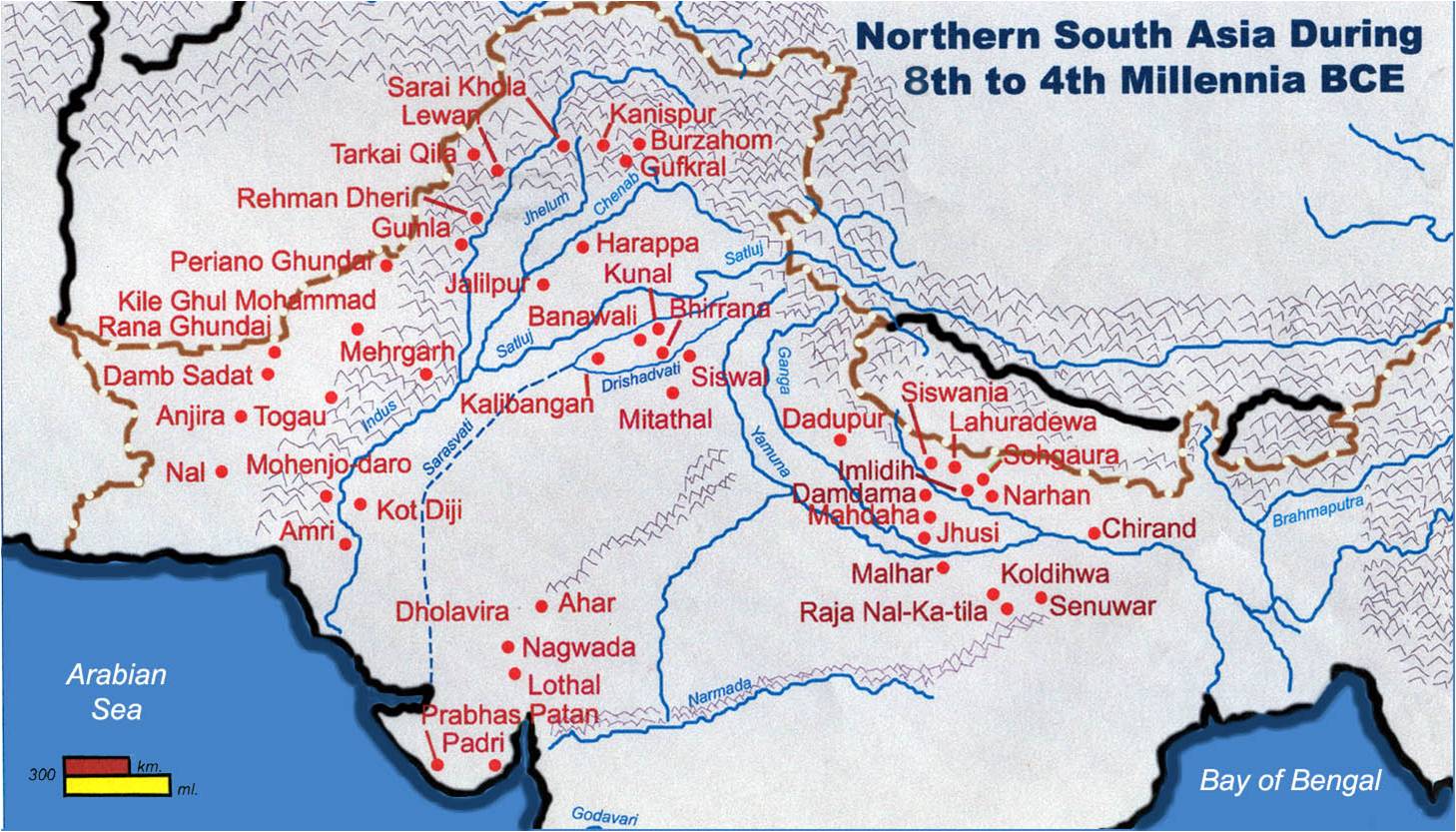

Similar is the function served by the Shahdad standard, as a Meluhha (mleccha) metalware catalog describing the repertoire of a smithy in Shahdad, Marhashi. So, it was that Chanhu-daro was ranked as Sheffied of the Ancient Near East serving a vast contact region with metalware tools, weapons, pots and pans. This regional/archaeological context matters while interpreting Meluhha writing (also called Indus writing) for the sounds of underlying words which became the lingua france of Indian sprachbund. That Meluhha is a language is recognized on a cylinder seal of Shu-Ilishu, Akkadian interpreter. That cognate Mleccha is a language is attested in the Great Epic, Mahabharata, in the episode of conversations between Yudhishthira had with Vidura and Khanaka, on the metallic weapons planted in a jatugriha (lac house) to destroy the Pandavas in exile. That Mleccha was a language is attested in an earlier text, Manusamhita as mleccha vācas. That Meluhha was a region in proximity to and that there were mleccha settlements in Mesopotamia, Dilmun, Magan, Elam, Marhashi, Susa are evidences well-attested in cuneiform texts. Lexemes 'mlecchamukha' in Sanskrit and 'milakkhu' in Pali means 'copper'. A Mleccha dynasty (c. 650 - 900) ruled Kamarupa from their capital at Hadapeshvar in the present-day Tezpur, Assam, after the fall of the Varman dynasty. It is also significant that assur who are smelters par excellence live close to Lohardiva, Malhar, Raja-nal-ki-tila on the Ganga basin, where iron smelters were discovered dated to ca. 18th century BCE. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/asur-metallurgists.html Ancient Near East: Traditions of smelters, metallurgists validate the Bronze Age Linguistic Doctrine.

Vātsyāyana used the term mlecchitavikalpa to denote cypher writing as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by the youth, including two other language-related arts: akṣaramuṣṭika kathanam 'narration using finger-wrist gestures' and deśabhāṣājñānam 'knowledge of vernacular languages'.

See for details:

1. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/shahdad-standard-meluhha-smithy-catalog.html Shahdad standard: Meluhha smithy catalog of Shahdad, Marhashi

2. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/ancient-near-east-shahdad-bronze-age.html Ancient Near East: Shahdad bronze-age inscriptional evidence, a tribute to Ali Hakemi

3. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/location-of-marhashi-and-cheetah-from.html Location of Marhashi and cheetah from Meluhha: Shahdad & Tepe Yahya are in Marhashi

3. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/07/location-of-marhashi-and-cheetah-from.html Location of Marhashi and cheetah from Meluhha: Shahdad & Tepe Yahya are in Marhashi

Chanhudaro. Sheffield of Ancient Near East. Metalware catalog in London News Illustrated, November 21, 1936.![]() A 'Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's metal working industry 10 X photos of copper knives, spears, razors, axes and dishes. The words used in the lingua franca of such tin-processing families constitute the words invented to denote the Bronze Age products and artifacts such as tin or zinc or the array of metalware discovered in the Sheffied of the Ancient East, Chanhu-daro as reported in the London News Illustrated by Ernest Mackay.

A 'Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's metal working industry 10 X photos of copper knives, spears, razors, axes and dishes. The words used in the lingua franca of such tin-processing families constitute the words invented to denote the Bronze Age products and artifacts such as tin or zinc or the array of metalware discovered in the Sheffied of the Ancient East, Chanhu-daro as reported in the London News Illustrated by Ernest Mackay.

A 'Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's metal working industry 10 X photos of copper knives, spears, razors, axes and dishes. The words used in the lingua franca of such tin-processing families constitute the words invented to denote the Bronze Age products and artifacts such as tin or zinc or the array of metalware discovered in the Sheffied of the Ancient East, Chanhu-daro as reported in the London News Illustrated by Ernest Mackay.

A 'Sheffield of Ancient India: Chanhu-Daro's metal working industry 10 X photos of copper knives, spears, razors, axes and dishes. The words used in the lingua franca of such tin-processing families constitute the words invented to denote the Bronze Age products and artifacts such as tin or zinc or the array of metalware discovered in the Sheffied of the Ancient East, Chanhu-daro as reported in the London News Illustrated by Ernest Mackay.

A bronze sculpture showing a dance-step becomes a hieroglyph of Indus writing on a Bhirrana potsherd, dance-step. meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Munda)

A bronze sculpture showing a dance-step becomes a hieroglyph of Indus writing on a Bhirrana potsherd, dance-step. meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Munda)Indus-Sarasvati valley sites

Bronze cart with canopy. 36.2237 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bronze cart with canopy. 36.2237 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston4th millennium Indus writing pre-dates all known writing.

Meluhha people who created the Sheffield of Anient Near East invented and used writing in the Indus Valley.

The potsherd h1522 discovered in Harappa on the banks of River Ravi by archaeologists of HARP (Harvard Archaeology Project) is dated to ca. 3500 BCE. Citing this find, the report quoted one of the excavators, Richard Meadow: "...these primitive inscriptions found on pottery may pre-date all other known writing." As the hieroglyphic writing system evolved, the impact was also evidenced in Susa, with the foundation of a settlement on the banks of Karkheh and Dez Rivers dated to 5th millennium BCE. The interactions between Elamite, Persian and Parthian empires of Iran and seafaring merchants of Meluhha can be re-evaluated in the context of the evidence provided by Indus writing. Discussing 3rd millennium BCE cultural relationships of Indus valley with the Helmand and Baluchistan, Cortesi et al refer to artifacts found at Shahr-I Sokhta and nearby sites (Iranian Seistan) presumably imported from Baluchistan, Mundigak (Kandahar, Afghanistan) and the Indus domain and indicating local adaptation of south-eastern manufactures and practices.

tagaraka ‘tabernae montana’. Rebus: tagara ‘tin’. Mineral tin alloyed with mineral copper yields bronze metal. One variant glyphic is an Indus script glyph (Sign 162) found on a potsherd dated to c. 3500 BCE.

The tabernae montana glyph characteristically depicted with five petals gains currency where Meluhha settlements existed or where Meluhha traders had contacts:

Cylinder seal showing tabernae montana. bicha ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) . ran:ga ron:ga, ran:ga con:ga = thorny, spikey, armed with thorns; (Santali) Rebus: ran:ga, ran: pewter is an alloy of tin lead and antimony (añjana) (Santali). Glyph: ‘bush, thorn’: Pk. kaṁṭiya -- ʻ thorny ʼ; S. kaṇḍī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ; N. kã̄ṛe ʻ thorny ʼ; A. kã̄ṭi ʻ point of an oxgoad ʼ, kã̄iṭīyā ʻ thorny ʼ; H. kã̄ṭī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ; G.kã̄ṭī f. ʻ a kind of fish ʼ; M. kã̄ṭī, kāṭī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ. -- Ext. with -- la -- : S. kaṇḍiru ʻ thorny, bony ʼ; -- with -- lla -- : Gy. pal. ḳăndīˊla ʻ prickly pear ʼ; H. kãṭīlā, kaṭ° ʻ thorny ʼ.(CDIAL 2679). kāṇṭaka -- ĀpŚr.1. Paš. kã̄ṛ ʻ porcupine ʼ (cf. kaṇṭakaśrēṇi -- , kaṇṭakāgāra -- ). 2. S. kã̄ḍo ʻ thorny ʼ, Si. kaṭu. -- Deriv.: S. kã̄ḍero m. ʻ camel -- thorn ʼ, °rī f. ʻ a kind of thistle ʼ(CDIAL 3022). Rebus: Tu. kandůka, kandaka ditch, trench. Te. kandakamu id. Konḍa kanda trench made as a fireplace during weddings. Pe. Kanda fire trench. Kui kanda small trench for fireplace. Malt. kandri a pit.(DEDR 1214). Rebus: kaṇḍ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

Cylinder seal showing tabernae montana. bicha ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’ (Mu.) . ran:ga ron:ga, ran:ga con:ga = thorny, spikey, armed with thorns; (Santali) Rebus: ran:ga, ran: pewter is an alloy of tin lead and antimony (añjana) (Santali). Glyph: ‘bush, thorn’: Pk. kaṁṭiya -- ʻ thorny ʼ; S. kaṇḍī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ; N. kã̄ṛe ʻ thorny ʼ; A. kã̄ṭi ʻ point of an oxgoad ʼ, kã̄iṭīyā ʻ thorny ʼ; H. kã̄ṭī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ; G.kã̄ṭī f. ʻ a kind of fish ʼ; M. kã̄ṭī, kāṭī f. ʻ thorn bush ʼ. -- Ext. with -- la -- : S. kaṇḍiru ʻ thorny, bony ʼ; -- with -- lla -- : Gy. pal. ḳăndīˊla ʻ prickly pear ʼ; H. kãṭīlā, kaṭ° ʻ thorny ʼ.(CDIAL 2679). kāṇṭaka -- ĀpŚr.1. Paš. kã̄ṛ ʻ porcupine ʼ (cf. kaṇṭakaśrēṇi -- , kaṇṭakāgāra -- ). 2. S. kã̄ḍo ʻ thorny ʼ, Si. kaṭu. -- Deriv.: S. kã̄ḍero m. ʻ camel -- thorn ʼ, °rī f. ʻ a kind of thistle ʼ(CDIAL 3022). Rebus: Tu. kandůka, kandaka ditch, trench. Te. kandakamu id. Konḍa kanda trench made as a fireplace during weddings. Pe. Kanda fire trench. Kui kanda small trench for fireplace. Malt. kandri a pit.(DEDR 1214). Rebus: kaṇḍ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.tampur ‘long-legged’ (Santali) Rebus: Pa. Pkt. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻcopperʼ, Pk. taṁbira -- ʻcoppercoloured, redʼ; S.kcch. trāmo, tām(b)o m. ʻcopperʼ; G.tã̄baṛ n., trã̄bṛī, tã̄bṛī f. ʻ copper pot ʼ; Pa. Pkt. tamba -- ʻred ʼ, n. ʻcopperʼ (CDIAL 5779).

Rakhigarhi kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) Rebus: khār a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār) (Kashmiri)

Rakhigarhi kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) Rebus: khār a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār) (Kashmiri)Wādī Salūt, Oman

Reading of the inscription of text:

ran:ku = liquid measure (Santali) rebus: ran:ku = tin (Santali)

kōnṭa corner (Nk.); tu. kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (B.)

dāmṛa, damrā ʻ young bull (A.)(CDIAL 6184). glyph: *ḍaṅgara1 ʻ cattle ʼrebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m a jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali)

ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali)

kōnṭa corner (Nk.); tu. kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (B.)

dāmṛa, damrā ʻ young bull (A.)(CDIAL 6184). glyph: *ḍaṅgara1 ʻ cattle ʼrebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m a jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali)

ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali)

baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched, rebus; bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’ (P.) baṭa = a kind of iron (G.)

Glyph: svastika; rebus: jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri). Svastika: sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) Rebus: svastika pewter (Kannada)

Glyph: svastika; rebus: jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri). Svastika: sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) Rebus: svastika pewter (Kannada)Tell Asmar

kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) Rebus: khār a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār) (Kashmiri)

· ibha (glyph). Rebus: ibbo (merchant of ib ‘iron’)

Ur. Seal impression. kuṭi ‘water-carrier’ (Te.); Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’ (Santali) meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) m1429C

ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.); rebus: aya ‘(alloyed) metal’ (G.) kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) Rebus: khār a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār) (Kashmiri) ayakāra ‘blacksmith’ (Pali)

m417 Glyph: ‘ladder’: H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ Rebus: Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. The lexeme in Tamil means: Limit, boundary; எல்லை. நளியிரு முந்நீரேணி யாக (புறநா. 35, 1). Country, territory.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work.

There are other seals/tablets which depict 5 or 6 animals surrounding a crocodile glyph. [The examples are nine inscribed objects: m02015 A,B, m2016, m1393, m1394, m1395, m0295, m0439, m440, m0441 A,B]. On some tablets, such a glyphic composition is also accompanied (on obverse side, for example, cf. m2015A and m0295) with a glyphic of two joined tiger heads to a single body. In one inscription (m0295), the text inscriptions are also read. The animals shown are: composite animal of three tigers, crocodile, heifer, tiger-looking-back, elephant, rhinoceros, zebu (bos indicus), a pair of bulls, monkey(?).

It is a reasonable inference that these glyphics are related to the community, or guild of artisans. This gets confirmed and unraveled as decipherment provides for rebus readings of all the clearly identifiable glyphic elements.

The identifiable joined animals on m0417 may relate to the lexeme sangaḍa ‘joined animals’ (Marathi). Rebus: sangāta ‘association, guild’.

1.Glyph: ‘one-horned heifer’: kondh ‘heifer’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’.

2.Glyph: ‘bull’: ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’. Pair of bulls: dula ‘pair’. Rebus: dul ‘casting (metal)’.

3.Glyph: ‘ram’: meḍh ‘ram’. Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

4.Glyph: ‘antelope’: mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’. Vikalpa 1: meluhha ‘mleccha’ ‘copper worker’. Vikalpa 2: meṛh ‘helper of merchant’.

5.Glyph: ‘zebu’: khũṭ ‘zebu’. Rebus: khũṭ ‘guild, community’ (Semantic determinant of the ‘jointed animals’ glyphic composition). kūṭa joining, connexion, assembly, crowd, fellowship (DEDR 1882) Pa. gotta ‘clan’; Pk. gotta, gōya id. (CDIAL 4279) Semantics of Pkt. lexeme gōya is concordant with Hebrew ‘goy’ in ha-goy-im (lit. the-nation-s).

6.The sixth animal can only be guessed. Perhaps, a monkey, a tiger, or a rhinoceros

Glyph: ‘monkey’: kuṭhāru = a monkey (Skt.lex.) Ta. kōṭaram monkey. Ir. kōḍa (small) monkey; kūḍag monkey. Ko. koṛṇ small monkey. To. kwṛṇ monkey. Ka. kōḍaga monkey, ape. Koḍ. koḍë monkey. Tu. koḍañji, koḍañja, koḍaṅ baboon (DEDR 2196) Konḍa (BB) kōnza red-faced monkey. Kui kōnja black-faced monkey. Kuwi (F.) kōnja monkey (small); (S.) konja ape; konzu monkey; (P.) kōnja black-faced monkey. (DEDR 2194) Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker), also an inscriber or writer.

Glyph: ‘tiger?’: kol ‘tiger’. Rebus: kol ’worker in iron’. Vikalpa (alternative): perhaps, rhinoceros. Glyph: baḍhi ‘castrated boar’. Rebus: baḍhoe ‘worker in wood and iron’.

Thus, the entire glyphic composition of six animals on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417 is semantically a representation of a śrḗṇi, ’guild’, a khũṭ , ‘community’ of smiths and masons.

Pa. gotta -- n. ʻ clan ʼ, Pk. gotta -- , gutta -- , amg. gōya -- n.; Gau. gū ʻ house ʼ (in Kaf. and Dard. several other words for ʻ cowpen ʼ > ʻ house ʼ: gōṣṭhá -- , Pr. gūˊṭu ʻ cow ʼ; S. g̠oṭru m. ʻ parentage ʼ, L. got f. ʻ clan ʼ, P. gotar, got f.; Ku. N. got ʻ family ʼ; A. got -- nāti ʻ relatives ʼ; B. got ʻ clan ʼ; Or. gota ʻ family, relative ʼ; Bhoj. H. got m. ʻ family, clan ʼ, G. got n.; M. got ʻ clan, relatives ʼ; -- Si. gota ʻ clan, family ʼ ← Pa. (CDIAL 4279).

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjaerum, The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Many of the bronze-age manufactured or industrial goods were surplus to the needs of the producing community and had to be traded, together with a record of types of goods and types of processes such as native metal or minerals, smelting of minerals, alloying of metals using two or more minerals, casting ingots, forging and turning metal into shapes such as plates or vessels, using anvils, cire perdue technique for creating bronze statues – in addition to the production of artifacts such as bangles and ornaments made of śankha or shell (turbinella pyrum), semi-precious stones, gold or silver beads. Thus writing was invented to maintain production-cum-trade accounts, to cope with the economic imperative of bronze age technological advances to take the artisans of guilds into the stage of an industrial production-cum-trading community.

Tablets and seals inscribed with hieroglyphs, together with the process of creating seal impressions took inventory lists to the next stage of trading property items using bills of lading of trade loads of industrial goods. Such bills of lading describing trade loads were created using tablets and seals with the invention of writing based on phonetics and semantics of language – the hallmark of Indian hieroglyphs.

m0491 Tablet. Line drawing (right)

Dawn of the bronze age is best exemplified by a Mohenjo-daro tablet which shows a procession of three hieroglyphs carried on the shoulders of three persons. The hieroglyphs are: 1. Scarf carried on a pole; 2. A heifer carried on a stand; 3. Portable standard device (lathe-gimlet).

Three professions are described by the three hieroglyphs: dhatu kõdā sã̄gāḍī ‘Associates (guild): mineral worker; metals turner-joiner (forge); worker on a lathe’.

The rebus readings are:

1.WPah.kṭg. dhàṭṭu m. ʻ woman's headgear, kerchief ʼ, kc. dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu m. ʻ scarf ʼ, J. dhāṭ(h)u m. Him.I 105). dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu) m. ‘scarf’ (WPah.) (CDIAL 6707) Rebus: dhatu = mineral (Santali) dhātu ‘mineral (Pali) dhātu ‘mineral’ (Vedic); a mineral, metal (Santali); dhāta id. (G.) H. dhāṛnā ‘to send out, pour out, cast (metal)’ (CDIAL 6771).

2.koḍiyum ‘heifer’ (G.) [ kōḍiya ] kōḍe, kōḍiya. [Tel.] n. A bullcalf. . k* దూడA young bull. Plumpness, prime. తరుణము. జోడుకోడయలు a pair of bullocks. kōḍe adj. Young. kōḍe-kāḍu. n. A young man.పడుచువాడు. [ kārukōḍe ] kāru-kōḍe. [Tel.] n. A bull in its prime. खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) గోద [ gōda ] gōda. [Tel.] n. An ox. A beast. kine, cattle.(Telugu) koḍiyum (G.) Rebus: koḍ artisan’s workshop (Kuwi); B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or. kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ‘lathe’) (CDIAL 3295)

3.Drawing. Reconstruction of the glyphic elements in ‘standard device’ shown in front of a heifer on many Indus inscriptions.

san:gaḍa, ‘lathe, portable furnace’; śagaḍī (G.) = lathe san:gāḍo a lathe; sãghāḍiyo a worker on a lathe (G.lex.) sãgaḍ part of a turner's apparatus (M.); sم̄gāḍī lathe (Tu.)(CDIAL 12859). sāṅgaḍa That member of a turner's apparatus by which the piece to be turned is confined and steadied. सांगडीस धरणें To take into linkedness or close connection with, lit. fig. (Marathi) सांगाडी [ sāṅgāḍī ] f The machine within which a turner confines and steadies the piece he has to turn. (Marathi) सगडी [ sagaḍī ] f (Commonly शेगडी) A pan of live coals or embers. (Marathi) san:ghāḍo, saghaḍī (G.) = firepan; saghaḍī, śaghaḍi = a pot for holding fire (G.)[culā sagaḍī portable hearth (G.)] Rebus 1: Guild. सांगडणी [ sāṅgaḍaṇī ] f (Verbal of सांगडणें) Linking or joining together (Marathi). संगति [ saṅgati ] f (S) pop. संगत f Union, junction, connection, association. संगति [ saṅgati ] c (S) pop. संगती c or संगत c A companion, associate, comrade, fellow. संगतीसोबती [ saṅgatīsōbatī ] m (संगती & सोबती) A comprehensive or general term for Companions or associates. संग [ saṅga ] m (S) Union, junction, connection, association, companionship, society. संगें [ saṅgēṃ ] prep (संग S) With, together with, in company or connection with. संघात [ saṅghāta ] m S Assembly or assemblage; multitude or heap; a collection together (of things animate or inanimate). संघट्टणें [ saṅghaṭṭaṇēṃ ] v i (Poetry. संघट्टन) To come into contact or meeting; to meet or encounter. (Marathi) G. sãghāṛɔ m. ʻ lathe ʼ; M. sãgaḍ f. part of a turner's apparatus ʼ (CDIAL 12859) Rebus 2: stone-cutting. sanghāḍo (G.) cutting stone, gilding (G.); san:gatarāśū = stone cutter; san:gatarāśi = stone-cutting; san:gsāru karan.u = to stone (S.) san:ghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (G.) Rebus 3: saṁghaṭayati ʻ strikes (a musical instrument) ʼ R., ʻ joins together ʼ Kathās. [√ghaṭ]Pa. saṅghaṭita -- ʻ pegged together ʼ; Pk. saṁghaḍia<-> ʻ joined ʼ, caus. saṁghaḍāvēi; M. sم̄gaḍṇẽ ʻ to link together ʼ. (CDIAL 12855). Rebus 3: battle. jangaḍiyo ‘military guard who accompanies treasure into the treasury’ (G.)

Glyph: ‘dotted circles’: kaṇḍ ‘eye’. Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’.

A cult object in the Temple of Inanna?

This trough was found at Uruk, the largest city so far known in southern Mesopotamia in the late prehistoric period (3300-3000 BC). The carving on the side shows a procession of sheep (a goat and a ram) approaching a reed hut (of a type still found in southern Iraq) and two lambs emerging. The decoration is only visible if the trough is raised above the level at which it could be conveniently used, suggesting that it was probably a cult object, rather than of practical use. It may have been a cult object in the Temple of Inana (Ishtar), the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility; a bundle of reeds (Inanna’s symbol) can be seen projecting from the hut and at the edges of the scene. Later documents make it clear that Inanna was the supreme goddess of Uruk. Many finely-modelled representations of animals and humans made of clay and stone have been found in what were once enormous buildings in the center of Uruk, which were probably temples. Cylinder seals of the period also depict sheep, cattle, processions of people and possibly rituals. Part of the right-hand scene is cast from the original fragment now in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

melh, mr̤eka ‘goat’; rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali). pasara ’domestic animals’. pasra ‘smithy, forge’.

Tabernae Montana, a flowering plant of the family Apocynaceae.

Glyphs on the bottom register of Uruk vase.

On the top register right corner, two animal glyphs are shown;: goat and tiger. mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper. kola ‘tiger’. Rebus: kol ‘pañcaloha, alloy of five metals’, ‘working in iron’. The pots are shown to contain stone ore ingots. below these animals two fire-altars with metal ingots (sometimes called ‘bun ingots’) are shown: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’. These glyphs recur on Indus script inscriptions.

Another line drawing of top register of the Uruk vase. The head of a bull is shown between two pots containing copper ingots. This is a semantic determinant of the contents of the pots. The bull, glyphic: adar ḍangra. Rebus: aduru ḍhangar ‘native metalsmith’. That is, the pots contain aduru ‘unsmelted native metal’.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia. Limestone 16 X 22.5 cm. AO 8842, Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France. Six circles decorated on the reed post are semantic determinants of Glyph: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

The following glyphics of m1431 prism tablet show the association between the tiger + person on tree glyphic set and crocile + 3 animal glyphic set.

m0489A One side of a prism tablet shows: crocodile + fish glyphic above: elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, tiger looking back and up.

m1431A m1431B Crocodile+ three animal glyphs: rhinoceros, elephant, tiger

It is possible that the broken portions of set 2 (h1973B and h1974B) showed three animals in procession: tiger looking back and up + rhinoceros + tiger.

Reverse side glyphs:

eraka ‘nave of wheel’. Rebus: era ‘copper’.

Animal glyph: elephant ‘ibha’. Rebus ibbo, ‘merchant’.

Composition of glyphics: Woman with six locks of hair + one eye + thwarting + two pouncing tigers + nave with six spokes. Rebus: kola ‘woman’ + kaṇga ‘eye’ (Pego.), bhaṭa ‘six’+ dul ‘casting (metal)’ + kũdā kol (tiger jumping) + era āra (nave of wheel, six spokes), ibha (elephant). Rebus: era ‘copper’; kũdār dul kol ‘turner, casting, working in iron’; kan ‘brazier, bell-metal worker’;

The glyphic composition read rebus: copper, iron merchant with taṭu kanḍ kol bhaṭa ‘iron stone (ore) mineral ‘furnace’.

Glypg: ‘woman’: kola ‘woman’ (Nahali). Rebus kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

Glyph: ‘impeding, hindering’: taṭu (Ta.) Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral’ (Santali) Ta. taṭu (-pp-, -tt) to hinder, stop, obstruct, forbid, prohibit, resist, dam, block up, partition off, curb, check, restrain, control, ward off, avert; n. hindering, checking, resisting; taṭuppu hindering, obstructing, resisting, restraint; Kur. ṭaṇḍnā to prevent, hinder, impede. Br. taḍ power to resist. (DEDR 3031)

Altyn depe seals

Glyph: svastika; rebus: jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri). Svastika: sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) Rebus: svastika pewter (Kannada)

खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi).kōḍiya, kōḍe young bull (Telugu) Rebus: kọ̆nḍu or konḍu । कुण्डम् m. a hole dug in the ground for receiving consecrated fire (Kashmiri) koḍ ‘workshop’ (Kuwi) mẽḍha ‘antelope’; rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) ḍangar ‘bull’ Rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’.

Haifa tin ingots

ranku 'liquid measure'; ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali)

Or. ḍagara ʻ footstep, road ʼ; Mth. ḍagar ʻ road ʼ, H. ḍagar f., ḍagrā m., G. ḍagar f. 2. P. ḍĩgh f. ʻ foot, step ʼ; N. ḍeg, ḍek ʻ pace ʼ; Mth. ḍeg ʻ footstep ʼ; H. ḍig, ḍeg f. ʻ pace ʼ. 3. L. dagg m. ʻ road ʼ, daggaṛ rāh m. ʻ wide road ʼ (mult. ḍaggar rāh < daggaṛ?); P. dagaṛ m. ʻ road ʼ, H. dagṛā m.(CDIAL 5523). Rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

Tin-copper alloy called tin-bronze or zinc-copper alloy called brass, were innovations that allowed for the much more complex shapes cast in closed moulds of the Bronze Age. Arsenical bronze objects appear first in the Near East where arsenic is commonly found in association with copper ore, but the health risks were quickly realized and the quest for sources of the much less hazardous tin ores began early in the Bronze Age. (Charles, J.A. (1979). "The development of the usage of tin and tin-bronze: some problems". In Franklin, A.D.; Olin, J.S.; Wertime, T.A. The Search for Ancient Tin. Washington D.C.: A seminar organized by Theodore A. Wertime and held at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Bureau of Standards, Washington D.C. March 14–15, 1977. pp. 25–32.)

Thus was created the demand for tin metal. This demand led to a trade network which linked distant sources of tin to the markets of Bronze Age.

Zinc added to copper produces a bright gold-like appearance to the alloy called brass. Brass has been used from prehistoric times. ( Thornton, C. P. (2007) "Of brass and bronze in prehistoric southwest Asia" in La Niece, S. Hook, D. and Craddock, P.T. (eds.) Metals and mines: Studies in archaeometallurgy London: Archetype Publications) The earliest brasses may have been natural alloys made by smelting zinc-rich copper ores. (Craddock, P.T. and Eckstein, K (2003) "Production of Brass in Antiquity by Direct Reduction" in Craddock, P.T. and Lang, J. (eds) Mining and Metal Production Through the Ages London: British Museum pp. 226–7.)

Zinc is a metallic chemical element; the most common zinc ore is sphalerite (zinc blende), a zinc sulfide mineral. Brass, which is an alloy of copper and zinc has been used for vessels. The mines of Rajasthan have given definite evidence of zinc production going back to 6th Century BCE.

http://www.infinityfoundation.com/mandala/t_es/t_es_agraw_zinc_frameset.htm Ornaments made of alloys that contain 80–90% zinc with lead, iron, antimony, and other metals making up the remainder, have been found that are 2500 years old. (Lehto, R. S. (1968). "Zinc". In Clifford A. Hampel. The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. New York: Reinhold Book Corporation. pp. 822–830.) An estimated million tonnes of metallic zinc and zinc oxide from the 12th to 16th centuries were produced from Zawar mines. (Emsley, John (2001). "Zinc". Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 499–505.)

The addition of a second metal to copper increases its hardness, lowers the melting temperature, and improves the casting process by producing a more fluid melt that cools to a denser, less spongy metal. ( Penhallurick, R.D. (1986). Tin in Antiquity: its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall. London: The Institute of Metals.)

Tin extraction and use can be dated to the beginnings of the Bronze Age around 3000 BC, when it was observed that copper objects formed of polymetallic ores with different metal contents had different physical properties. (Cierny, J.; Weisgerber, G. (2003). "The "Bronze Age tin mines in Central Asia". In Giumlia-Mair, A.; Lo Schiavo, F. The Problem of Early Tin. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 23–31.)

Tin is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, where it occurs as tin dioxide, SnO2.The first alloy, used in large scale since 3000 BC, was bronze, an alloy of tin and copper. Cassiterite often accumulates in alluvial channels as placer deposits due to the fact that it is harder, heavier, and more chemically resistant than the granite in which it typically forms. Early Bronze Age prospectors could easily identify the purple or dark stones of cassiterite from alluvial sources and could be obtained the same way gold was obtained by panning in placer deposits.

Pewter, which is an alloy of 85–90% tin with the remainder commonly consisting of copper, antimony and lead, was used for flatware.

Here is a pictorial gallery:

Panning for cassiterite using bamboo pans in a pond in Orissa. The ore is carried to the water pond or stream for washing in bamboo baskets.

People panning for cassiterite mineral in the remote jungles of central India.

The ore is washed to concentrate the cassiterite mineral using bamboo pans. Base of small brick and mud furnace for smelting tin.

The tin is refined by remelting the pieces recovered from the furnace in an iron pan. The molten tin is poured into stone-carved moulds to make square- or rectangular-ingots.

As the pictorial gallery demonstrates, the entire tin processing industry is a family-based or extended-family-based industry. The historical traditions point to the formation of artisan guilds to exchange surplus cassiterite in trade transactions of the type evidenced by the seals and tablets, tokens and bullae found in the civilization-interaction area of the Bronze Age.

Daimabad seal. Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka, kaṇḍ kan-ka 'rim of jar'. Rebus: ‘furnace scribe'.

![]() m1656 The glyphics of ‘water-overflow’ from the ‘rim’ of the ‘short-necked jar’ completes the semantic rendering by the lo ‘overflow’. Rebus readings: <lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).

m1656 The glyphics of ‘water-overflow’ from the ‘rim’ of the ‘short-necked jar’ completes the semantic rendering by the lo ‘overflow’. Rebus readings: <lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).

m1656 The glyphics of ‘water-overflow’ from the ‘rim’ of the ‘short-necked jar’ completes the semantic rendering by the lo ‘overflow’. Rebus readings: <lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).

m1656 The glyphics of ‘water-overflow’ from the ‘rim’ of the ‘short-necked jar’ completes the semantic rendering by the lo ‘overflow’. Rebus readings: <lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).Cylinder seal impression of Ibni-sharrum, a scribe of Shar-kalisharri ca. 2183–2159 BCE The inscription reads “O divine Shar-kali-sharri, Ibni-sharrum the scribe is your servant.”Cylinder seal. Chlorite. AO 22303 H. 3.9 cm. Dia. 2.6 cm.[i] khaṇṭi‘buffalo bull’ (Tamil) kaṭā, kaṭamā ‘bison’ (Tamil)(DEDR 1114) (glyph). Rebus: khaṇḍ ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’; kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍa-i-o = (Skt. Sthapati, a mason) a bricklayer, mason (G.)] <lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. @B24310. #20851. Re<lo->(B) {V} ``(pot, etc.) to ^overflow''. See <lo-> `to be left over'. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) Glyph of flowing water in the second register: காண்டம் kāṇṭam , n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர்; kāṇṭam ‘ewer, pot’ கமண்டலம். (Tamil) Thus the combined rebus reading: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171). The kneeling person’s hairstyle has six curls. bhaṭa ‘six’; rebus: bhaṭa‘furnace’. मेढा mēḍhā A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) Thus, the orthography denotes meḍ bhaṭa‘iron furnace’.