December 6, 2012

Bull and horse, migrations of bos indicus and equus sivalensis into Ancient Near East

Bull and horse are two domesticated animals mentioned in the early text of Rigveda and evidenced in Indo-European language studies. Study of the migrations of these two animals may yield a pointer to the possible migrations of peoples ca. 3rd millennium BCE into Ancient Near East, thus providing clues to unravel the chronologies of ancient history.

A seal with Indus script.

A seal with Indus script.  A zebu on a plaque from the Elamite Diyala Valley (Lamberg-Karlovsky and Potts 2001: 225).

A zebu on a plaque from the Elamite Diyala Valley (Lamberg-Karlovsky and Potts 2001: 225). Tepe Hissar. Lapis lazuli stamp seal. Bronze Age, about 2400-2000 BC. From the ancient Near East. This stamp seal was originally almost square, but because of damage one corner is missing. Originally two figures faced each other. The one on the left has largely disappeared. On the right is a man with his legs folded beneath him. It is suggested that at the top are rain clouds and rain or a fenced enclosure. Behind the man are a long-horned goat above a zebu. This last animal is related in style to similar creatures depicted on seals from the Indus Valley civilization, which was thriving at this time. There were close connections between the Indus Valley civilization and eastern Iran. One of the prized materials that was traded across the region was lapis lazuli, the blue stone from which this seal is made. The Sar-i Sang mines in the region of Badakhshan in north-east Afghanistan were probably the source for all lapis lazuli used in the ancient Near East. From here it was carried across Iran, where several lapis working sites have been discovered, and on to Mesopotamia and Egypt. Another source for lapis lazuli exists in southern Pakistan (a region of the Indus Valley civilization) but it is unclear if they were mined at the time of this seal. D. Collon, 'Lapis lazuli from the east: a stamp seal in the British Museum', Ancient Civilizations from Scy, 5/1 (1998), pp. 31-39 D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern art (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

Tepe Hissar. Lapis lazuli stamp seal. Bronze Age, about 2400-2000 BC. From the ancient Near East. This stamp seal was originally almost square, but because of damage one corner is missing. Originally two figures faced each other. The one on the left has largely disappeared. On the right is a man with his legs folded beneath him. It is suggested that at the top are rain clouds and rain or a fenced enclosure. Behind the man are a long-horned goat above a zebu. This last animal is related in style to similar creatures depicted on seals from the Indus Valley civilization, which was thriving at this time. There were close connections between the Indus Valley civilization and eastern Iran. One of the prized materials that was traded across the region was lapis lazuli, the blue stone from which this seal is made. The Sar-i Sang mines in the region of Badakhshan in north-east Afghanistan were probably the source for all lapis lazuli used in the ancient Near East. From here it was carried across Iran, where several lapis working sites have been discovered, and on to Mesopotamia and Egypt. Another source for lapis lazuli exists in southern Pakistan (a region of the Indus Valley civilization) but it is unclear if they were mined at the time of this seal. D. Collon, 'Lapis lazuli from the east: a stamp seal in the British Museum', Ancient Civilizations from Scy, 5/1 (1998), pp. 31-39 D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern art (London, The British Museum Press, 1995) Figure 1. Map of Iran, with Jiroft, Konār Ṣandal, and sites of the 3rd millenium BCE with chlorite vessels.

Figure 1. Map of Iran, with Jiroft, Konār Ṣandal, and sites of the 3rd millenium BCE with chlorite vessels. Tepe Yahya/Jiroft frieze. Zebus and lions. A zebu gores a lion (the zebu seems to be then on the verge of domestication, Figure 7f.

Tepe Yahya/Jiroft frieze. Zebus and lions. A zebu gores a lion (the zebu seems to be then on the verge of domestication, Figure 7f. c. 2900 BCE. Khafajah. The best known of the chlorite bowls is from Khafajah; it is of Mesopotamian manufacture. • A man kneels upon the hindquarters of one of a pair of standing zebu bulls facing away from each other. In each hand he holds a stream of water which flows over the head and finishes in front of each bull. Plants grow from the right stream, plants grow behind the left bull, and a plant grows in front of each bull. Above the man are a rosette, a crescent and (possibly) a snake. Above the left stream is some sort of carnivore, perhaps a panther.

c. 2900 BCE. Khafajah. The best known of the chlorite bowls is from Khafajah; it is of Mesopotamian manufacture. • A man kneels upon the hindquarters of one of a pair of standing zebu bulls facing away from each other. In each hand he holds a stream of water which flows over the head and finishes in front of each bull. Plants grow from the right stream, plants grow behind the left bull, and a plant grows in front of each bull. Above the man are a rosette, a crescent and (possibly) a snake. Above the left stream is some sort of carnivore, perhaps a panther. • An identical man stands behind or between two couchant panthers, rears together and tails raised but heads turned to face each other. In each hand he holds a snake; by his head is another rosette.

• An eagle and a lion attack a bull which is lying on its back. Plants grow from behind the lion. To the left of this group is a scorpion. Below the lion’s hindquarters is a scene of two bears standing about a date palm licking their paws.

"In the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., the Iranian plateau (Figure 1) was at the crossroads of trade with its neighboring regions...In the first half of the 3rd millennium, Fars appears as the development center of the first writing, called “proto-Elamite,” which was soon used throughout Iranian plateau. In its southern part of Kerman, tablets have been identified 75 km away to the west of Jiroft at the small site of Tepe Yahya (Yaḥyā), located at about 130 km north of the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf...The region of Jiroft, lying far away from the large centers of civilization, had not until now attracted the attention of researchers. It is located at a distance of 1000 km from the valley of the Euphrates in the west and from the Indus River in the east. Tepe Yahya and Shahdad (Šahdād), 200 km to the north-northeast of Kerman, were occupied at the end of the 3rd millennium and hint at a culture specific to the south of Iran."

Chlorite vessels. Plate IV. Various: miniature vessels a-b: tronconical vessels, single-horned zebu (h 8.2 cm);

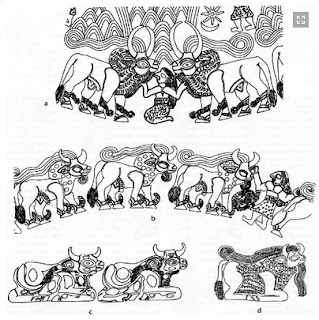

Chlorite vessels. Plate IV. Various: miniature vessels a-b: tronconical vessels, single-horned zebu (h 8.2 cm); Figure 6. Zebus: a: details of decoration on a tronconical vessel; b: line of zebus led by a man; c-d lying zebus.

Figure 6. Zebus: a: details of decoration on a tronconical vessel; b: line of zebus led by a man; c-d lying zebus.vŕ̊ṣan -- ʻ strong, great ʼ, m. ʻ male, bull ʼ RV. [√vr̥ṣ?] वृषः 1 A bull; असंपदस्तस्य वृषेण गच्छतः Ku.5.8; Me.54; R.2.35; Ms.9.123. -2 The sign Taurus of the zodiac. -3 The chief or best of a class, the best of its kind; (often at the end of comp.); मुनिवृषः, कपिवृषः &c. -इन्द्रः an excellent bull. -ध्वजः 1 an epithet of Śiva; येन बाणमसृजद्वृषध्वजः R.11.44. -2 an epithet of Gaṇeśa. -पतिः 1 an epithet of Śiva. -2 a bull set at liberty. वृषण a. 1 Sprinkling, fertilizing. -2 Strong, stout. -णः 1 The scrotum, the bag containing the testicles M. vaśẽḍ, oś°, vaśĩḍ, °śãḍ, vasãḍ, osãḍ(ẽ) n. ʻ bullock's hump ʼ.(CDIAL 12084). vr̥ṣabhá ʻ powerful ʼ, m. ʻ lord, male, bull ʼ RV. Pa. vasabha -- m. ʻ bull ʼ, Pk. vasaha -- , vis°, vus° m.; N. basāhā ʻ bull not used for ploughing ʼ; Bi. basahā ʻ bull bought by religious mendicants ʼ; Mth. basahʻ bull ʼ, Bhoj. basahā, OAw. basaha, H. basah m.; M. vasū m. ʻ bull calf, bull branded and set at liberty ʼ, vaśẽ, ośẽ n. ʻ bullock's hump ʼ; -- Si. vähäp ʻ ox, steer ʼ (EGS 162) ← Pa. -- X ukṣán -- q.v. (CDIAL 12085) ऋषभः [ऋष्-अभक्; Uṇ 3.123] 1 A bull. -2 (With names of other animals) the male animal, as अजर्षभः a goat. -3 The best or most excellent (as the last member of a comp.); as पुरुषर्षभः, भरतर्षभः &c. -4 The second of the seven notes of the gamut; (said to be uttered by cows; गावस्त्वृषभभाषिणः); श्रुतिसमधिकमुच्चैः पञ्चमं पीडयन्तः सततमृषभहीनं भिन्नकीकृत्य षड्जम् Śi.11.1; ऋषभो$त्र गीयत इति Āryā S.141 ऋषभतरः A small or young bull.

ūrar (u-stem), ags. ūr, ahd. ūro, ūrohso, lat. Lw. ūrus `a kind of wild ox', schwed. mdartl. ure `randy bull, a bull in heat' (`*one that scatters, drops, one that inseminates' as Old Indian vr̥šan- etc, see under)

u̯r̥sen- `discharging semen = virile', Old Indian vr̥šán- `virile', m. `manikin, man, stallion'. thereof derived av. varǝšna- `virile', Old Indian vŕ̥ṣ̣a-, vr̥ṣabhá- `bull', vŕ̥ṣṇi- `virile', m. `Aries, ram' (= av. varǝšni- ds.), vŕ̥šaṇa- m. `testicles'

http://dnghu.org/indoeuropean.html Indo-European Language Lexicon, and an Etymological Dictionary of Early Indo-European Languages. Etymologisches Woerterbuch (JPokorny)

Some etyma for the dewlap:

S. kamari f. ʻ dewlap ʼ, M. kã̄baḷ f. kambala2 m. ʻ dewlap ʼ VarBr̥S. Pk. kaṁbala -- m. ʻ dewlap of an ox ʼ(CDIAL 2772) Pa. gala -- m. ʻ throat, dewlap (CDIAL 4070). L. galmã, (Ju.) g̠almã̄ m. ʻ dewlap of cattle ʼ through *galamalā or poss. < *kamlā X gal.(CDIAL 4071). Sh. (Lor.) grĩ ʻ dewlap(of bull), collar (of coat) ʼ, bro. grī ʻ neck ʼ; OB. gīva ʻ throat ʼ, grīvāˊ f. ʻ nape of neck ʼ RV.(CDIAL 4387). Sa. gErwEl `ring, ring-formed marking (especially on neck, on peacock's feather, on a cobra's neck), striped, speckled, vari'. (Munda etyma) दृतिः m., f. [दॄ-विदारणे तिकित् ह्रस्वश्च] 1 A leathern bag for holding water &c.; इन्द्रियाणां तु सर्वेषां यद्येकं क्षरती- न्द्रियम् । तेनास्य क्षरति प्रज्ञा दृतेः पादादिवोदकम् ॥ Ms.2.99; Y.3.268. -2 A fish. -3 A skin, hide. -4 A pair of bellows; हृतय इव श्वसन्ति Bhāg.1.87.17. -5 Ved. A cloud. - A dewlap (of cow or bull); सवत्सां पीवरीं दत्वा दृतिकण्ठामलंकृताम् Mb.13.79.18. Maṇila [cp. *Sk. maṇila dewlap?] (Pali); having fleshy excrescences (as on the dewlap &c )(TS.Skt.) Ta. aṇal neck, side of the upper jaw, chin, throat, windpipe, beard, dewlap; Ka. aṇal under part of the mouth, the mouth. (DEDR 114). मवल् । सास्ना f. the dewlap of an ox.(Kashmiri)

Archaeological and genetic studies are summarized in Section 1. Bull and Section 2. Horse:

Section 1. Bull Indo-Europeans domesticated the cow, the bull and the horse. Root? gu̯au/-gu̯ou-: Sanskrit go-, Avestan gāu-, Tocharian keu /ko, Armenian kov, Lithuanian gùovs, German Kuh, Irish bó, all for 'cow', Albanian ka/kau, Greek βοῦς, 'ox, cow', Latin bōs, bovis, Croatian and Serbian vo, 'ox'. See discussions at http://new-indology.blogspot.in/ http://www.scribd.com/doc/115702890/Ant-0760438 Ant 0760438

This remarkable study traces the migrations out of India into the Ancient Near East: “Uncertain early occurrences of zebu depictions in Mesopotamia include a highly dubious figurine from Arpachiyah near Mosul in north Iraq, of 5th-millennium date (Mallowan & Rose 1935: figure 48:14), depictions on seals from Nineveh of about 3000 BC (Zeuner 1963: 239), a clay tablet from Larsa with seal impression showing a zebu (Epstein 1971: 508), and a marble amulet from Ur in the form of a zebu (Hornblower 1927), both the Larsa and Ur items perhaps dating to around 3000 BC. At about the same time, late 4th millennium, representations of zebu are found as figurines and painted pottery motifs at Susa in southwest Iran (Epstein 1971: 508; Zeuner 1963: 239). These often questionable occurrences suggest that zebu may have been familiar beasts to some of the inhabitants of south Mesopotamia by 3000 BC, although their physical presence there has yet to be confirmed by the scant archaeozoological evidence. Significantly, zebu are not so far attested in any form, artistic rendering or faunal remains, in regions to the west or north of Mesopotamia before 2000 BC. From 2500 BC onwards there are increasing representations of zebu in the form of figurines and motifs on seals and painted pottery in the material culture of the Indus valley and beyond, at sites such as Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, as well as the Quetta-Pishin valley and the Makran coast of Baluchistan (Epstein & Mason 1984: 15; Zeuner 1963: 236). From here zebu probably reached Oman and the head of the Persian Gulf (Potts 1997: 257), and spread to the world-view of south Mesopotamia by the 3rd millennium BC. A stone bowl sherd, of mid 3rd-millennium date, from Tell Agrab in the Diyala region northeast of Baghdad, shows an impressive zebu bull (Zeuner 1963: 217), and a well-executed sketch of a zebu head and shoulder is preserved on a clay tablet of later 3rd-millennium date from Tell Asmar, also in the Diyala region (Frankfort 1934: figure 18). In Iranian Seistan zebu bones and figurines are attested in great quantities at the site of Shahr-i Sokhta in the period c. 2900-2500 BC (Ports 1997: 255), while later, questionable, examples occur at Anau in Turkmenistan (Pumpelly 1908: plate 47:4). As to north Mesopotamia, a well-shaped and painted example of a zebu bull from level IV at Tepe Gawra (FIGURE 3:1) dates probably to the mid 2nd millennium BC but may be earlier (Speiser 1935: plate 77:5). Also in north Mesopotamia, zebu are attested at Tell Brak in the form of figurines (FIGURES 3:2, 4) and bifurcate vertebrae (FIGURE 5) from levels dating to 1700-1600 BC (Matthews 1995: 98-9), as well as figurines from mid 2nd-millennium levels (McDonald 1997: 131) (FIGURES 3:3-4). Perhaps significantly, zebu are not depicted in the glyptic art of Brak in the 3rd millennium, a rich source of depictions of domesticated and wild animals (Matthews et al. 1994), nor are they depicted on the elaborately painted ceramics of highland Anatolia and the Caucasus of the early 2nd millennium which host depictions of many other animals (Ozfirat 2001). Approximately contemporary with the Brak zebu evidence, at around 1700 BC, is a fine example of a figurine from the nearby site of Chagar Bazar, sporting a painted representation of what may be a harness (Mallowan 1937: figure 10:30). From Beydar, to the northwest of Tell Brak, comes an ivory furniture inlay with zebu in relief, dated to 1400 BC (Bretschneider 2000: 65) and a plain zebu figurine comes from mid 2nd-millennium BC levels at Tall Hamad Aga in north Iraq (Spanos 1988: Abb 18:2). An early 2nd-millennium context at Ishchali in the Diyala region yielded a fine clay plaque depicting a bull zebu ridden by a man who grasps the animal's hump in one hand while inserting his knees under a simple belt around the its waist (Frankfort 1954: plate 59:c). [FIGURES 3-5 OMITTED] A fragmentary zebu figurine comes from late 2nd-millennium levels at Tell Sabi Abyad in northwest Mesopotamia (Akkermans 1993:31, figure 23:85). Large quantities of zebu figurines, varying in their degree of elaboration, have been found in Late Bronze Age deposits at Tell Munbaqa in north Syria (Machule et al. 1986; 1990; Czichon & Werner 1998: Taf 80-5) (FIGURE 3:5). There are also zebu figurines from the Late Bronze Age site of Meskene-Emar on the north Syrian Euphrates not far from Munbaqa (Beyer 1982: 104) (FIGURE 3:6), from mid 2nd-millennium BC period II at Umm el-Marra west of the Syrian Euphrates (Curvers & Schwartz 1997: figure 21) and from level VII of Alalakh in northwest Syria, dated to early/mid 2nd millennium (Woolley 1955: plate 57:a). Cylinder seals of 13th-century BC date from Upper Mesopotamia depict humped cattle pulling ploughs (Wiggermann 2000: figure 7) and there is a zebu pendant of 13th-century BC date from Assur on the Tigris in north-central Iraq (Boehmer 1972: 168, Abb 51). Zebu figurines appear in level 3A of Haradum on the Iraqi Euphrates, dated to the mid 17th century BC (Kepinski-Lecomte 1992: figure 159:6-7). On a Kassite seal from Mesopotamia, dated to c. 1500 BC, zebu are depicted drawing ploughs (Epstein 1971: 515). A study of cattle astragali from archaeological sites of western Asia has detected the gradual development of distinctive cattle breeds throughout the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC, followed by an episode of rapid change at the end of the 2nd millennium, that is at the end of the Late Bronze Age (Buitenhuis 1984: 216). Buitenhuis connects this episode with the large-scale introduction of zebu into western Asia at this time, leading to cross-breeding of taurine and zebu stock (Buitenhuis 1984: 216). As we have seen above, it is possible that zebu had already been introduced to Mesopotamia by the mid 3rd millennium BC, but it seems that their spread into Syria and the Levant did not occur until the mid-later 2nd millennium.”

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Zebu%3a+harbingers+of+doom+in+Bronze+Age+western+Asia%3f-a089075892

Roger Matthews, 2002, Zebu: harbingers of doom in Bronze Age western Asia? Antiquity, Volume: 76 Number: 292 Page: 438–446

http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/076/Ant0760438.htm

http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/085/0544/ant0850544.pdf Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals Dorian Q Fuller, Nicole Boivin, Tom Hoogervorst & Robin Allaby Antiquity 85 (2011): 544-588

“...in the first millennium BC, the Indian Ocean actually began to open up in the broad sense. By Iron Age times, systematic trade between urban systems was taking place across the Bay of Bengal and between India and the Red Sea. This period also potentially provides the first evidence for Asian species introduction into the moist tropics of Africa. While this claim still rests heavily on the banana phytoliths from Nkang in Cameroon, other lines of evidence, from plant and animal genetics, and linguistics, suggest that the later centuries BC were a period of increasing flows across the Indian Ocean, mainly it appears, at least from a species point of view, from east to west. The insular Southeast Asian involvement in this is certainly clear for the period of the Malagasy peopling of Madagascar sometime in the first millennium AD, but there is a likelihood that this was only the latest of a series of such movements.” A schematic representation of some key Arabian Sea-Savannah zone biotic transfers of prehistory (the “Bronze Age horizon”). The question of how precisely African crops reached India beginning around 2000 BCE has now attracted the attention of archaeologists and botanists for decades...First, there was an earlier circum-Arabia or Arabian Sea phase of the Middle Bronze Age (from 2000 BCE), in which domesticates were transferred between the northern African savannahs and the savannah zones of India (Figure 1). Then there was a later mid-Indian Ocean phase that may be regarded as generally Iron Age (late centuries BCE to early centuries CE), which began to draw South India, South-east Asia and East Africa into the wider remit of trade/contact, setting the stage for a genuinely Indian Ocean world. In addition, we would like to draw attention to the significance of transfers of commensal animals and weeds, a largely unstudied but potentially revealing body of evidence for early human contacts across the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean." ”We will suggest that there are two broad phases and sets of processes in intercontinental transfers. First, there was an earlier circum-Arabia or Arabian Sea phase of the Middle Bronze Age (from 2000 BCE), in which domesticates were transferred between the northern African savannahs and the savannah zones of India (Figure 1). Then there was a later mid-Indian Ocean phase that may be regarded as generally Iron Age (late centuries BCE to early centuries CE), which began to draw South India, South-east Asia and East Africa into the wider remit of trade/contact, setting the stage for a genuinely Indian Ocean world.” "About twenty years ago Cleuziou and Tosi (1989: 15) referred to the prehistoric Arabian peninsula as a “conveyor belt between the two continents, channelling an early dispersal of domestic plants and animals.”

A schematic representation of some key Arabian Sea-Savannah zone biotic transfers of prehistory (the “Bronze Age horizon”). The question of how precisely African crops reached India beginning around 2000 BCE has now attracted the attention of archaeologists and botanists for decades...First, there was an earlier circum-Arabia or Arabian Sea phase of the Middle Bronze Age (from 2000 BCE), in which domesticates were transferred between the northern African savannahs and the savannah zones of India (Figure 1). Then there was a later mid-Indian Ocean phase that may be regarded as generally Iron Age (late centuries BCE to early centuries CE), which began to draw South India, South-east Asia and East Africa into the wider remit of trade/contact, setting the stage for a genuinely Indian Ocean world. In addition, we would like to draw attention to the significance of transfers of commensal animals and weeds, a largely unstudied but potentially revealing body of evidence for early human contacts across the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean." ”We will suggest that there are two broad phases and sets of processes in intercontinental transfers. First, there was an earlier circum-Arabia or Arabian Sea phase of the Middle Bronze Age (from 2000 BCE), in which domesticates were transferred between the northern African savannahs and the savannah zones of India (Figure 1). Then there was a later mid-Indian Ocean phase that may be regarded as generally Iron Age (late centuries BCE to early centuries CE), which began to draw South India, South-east Asia and East Africa into the wider remit of trade/contact, setting the stage for a genuinely Indian Ocean world.” "About twenty years ago Cleuziou and Tosi (1989: 15) referred to the prehistoric Arabian peninsula as a “conveyor belt between the two continents, channelling an early dispersal of domestic plants and animals.”

(Dorian Q. Fuller et Nicole Boivin, 2009, Crops, cattle and commensals across the Indian Ocean http://oceanindien.revues.org/698)

"Zebus are a type of domestic cattle originating in South Asia, particularly the Indian subcontinent... Zebu have humps on the shoulders, large dewlaps and droopy ears. (Definition: Zebu". Online Medical Dictionary.) ... They are classified within the species Bos primigenius, together with taurine cattle (Bos primigenius taurus) and the ancestor of both of them, the extinct aurochs (Bos primigenius). European cattle are descended from the Eurasian subspecies, while zebu are descended from the Indian subspecies. There are some 75 known breeds of zebu, split about evenly between African breeds and South Asian ones. The major zebu cattle breeds of the world include Gir, Guzerat, Kankrej, Indo-Brazilian, Brahman, Nelore, Ongole, Sahiwal, Red Sindhi, Butana, Kenana, Boran, Baggara, Tharparkar, Kangeyam, Chinese Southern Yellow, Philippine native, Kedah - Kelantan, and local Indian Dairy (LID). Other breeds of zebu are quite local, like the Hariana of Haryana and eastern Punjab or the Rath of Alwar in eastern Rajasthan.The Sanga cattle breeds originated from hybridization of zebu with indigenous humpless cattle in Africa; they include the Afrikaner, Red Fulani, Ankole-Watusi, and many other breeds of central and southern Africa. Sanga cattle can be distinguished from pure zebu by having smaller humps located farther forward on the animals. "(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zebu )

Zebu migrations, DNA studies and Aryan Invasion as an indological propaganda.

The myth of Aryan Invasion (now Tourist or Influx) Theory is the propaganda of indologists believing in Biblical creationism, Tower of Babel and eurocentric racism. A remarkable study reported in the Economist explodes the myth and propaganda.

The reporters of Economist did not realise the importance of zebu as an abiding image of Sarasvati civilization and a cultural continuum in Bharatam. Even today, people can see the zebu roaming the streets of many towns and cities of Gujarat and other states. The zebu, bos indicus, was as Bharatiya in origin as the creators of the civilization and the textual traditions exemplified by a vast library of texts, well before the other parts of the world had any domesticated cultivation together with domestication of animals apart from the use of metallurgical advances to create new modes of social organization.

http://sarasvati95.googlepages.com/home update:

Zebu migrations

Mirrored at http://sarasvati95.googlepages.com/zebumigrations.doc

http://www.mindfully.org/GE/GE2/Domestication-Not-Simple.htm

Zebu, bos indicus with a pronounced hump, are the signature tunes on many inscribed objects of Sarasvati civilization on many epigraphs.

See, foe example, http://kalyan97.googlepages.com/tabernaemontana.jpg On this seal impression with a set of hieroglyphs (epigraph), the zebu is shown together with tagaraka, tabernae Montana, hair fragrance flower (used as a homonym for tagara 'tin'). The zebu is called adar d.angra; read rebus: aduru d.angar 'native metal smith' (aduru 'native metal' – Kannada; d.angar 'smith' (Hindi).

The DNA study on domestication of cattle shows an interesting picture of migrations of zebu cattle out of Bharatam. This is evidence against the myth of the so-called Aryan invasions presented by many indologists.

Domestication's family tree

DNA is revealing that taming animals was not a simple process

The Economist 26apr01

FEW subjects, these days, can escape the embrace of genetics. That is especially true of archaeology. The study of genes has already illuminated humanity's history, showing how and when the species spread from its African roots to the farthest corners of the world. Now it is uncovering details of the most significant period of that history, the beginning of agriculture.

The latest piece of the jigsaw was published in this week's Nature by Christopher Troy of Trinity College, Dublin, and David MacHugh of University College, Dublin. They and their colleagues have been trying to work out whether modern European cattle were domesticated from the now extinct auroch ( Bos primigenius) that once roamed the continent, or are the descendants of cattle that were brought from the Middle East by the settlers who are believed to have introduced agriculture to Europe around 7,000 years ago.

To answer this question, Dr Troy and Dr MacHugh turned to mitochondrial DNA. This particular form of the genetic material is more abundant in a cell than is the familiar DNA of the cell's nucleus. That is because each cell has many mitochondria. They are the cellular components that release energy from glucose, and they have their own DNA because they were, in the distant evolutionary past, free-living bacteria. By contrast, a cell has but a single nucleus. Extracting mitochondrial DNA from old bones is therefore easier than extracting nuclear DNA.

That is what Dr Troy and Dr MacHugh did. They took mitochondrial DNA samples from four fossil aurochs found in Britain and compared them with the mitochondrial DNA of modern cattle from Europe, Africa and the Middle East . As time passes, mutations accumulate in the DNA, as one "letter" of the genetic code is replaced by another. By looking at the number of differences between the DNA-sequences of two creatures it is possible to see how closely related they are. It is also possible to estimate how much time has passed since they shared a common ancestor, since the rate at which letters are substituted usually remains constant for particular types of creature.

As the diagram shows, the aurochs, though related to Middle Eastern and European cattle, are on a branch by themselves. The aboriginal Europeans did not, it seems, have the wit to domesticate cattle. It took a bunch of immigrants to show them how.

http://mail.google.com/mail/?attid=0.1&disp=emb&view=att&th=110a377d04070bc4

That, until recently, would have been regarded as a textbook example of the way that agriculture developed. Species, it was theorised, were domesticated only once and the result "diffused" to the rest of the world. Over the past few years, though, other genetic studies have revealed a more interesting pattern.

The diagram of the cattle family tree published by Dr Troy and Dr MacHugh incorporates another branch, discovered a little while ago by Daniel Bradley, one of their collaborators who also works at Trinity College. Dr Bradley was responsible for testing the theory that modern cattle are the result of not one but two separate domestications. This theory, which predates even Charles Darwin, is based on the very different anatomies of cattle found in Europe and the Middle East, compared with those from India. In particular, the westerly cattle lack the shoulder humps of zebu, the Indian breed.

Those who support the idea of a single domestication suggest that the distinctions could be the result of subsequent selective breeding. Dr Bradley, though, used mitochondrial DNA to show that the most recent common ancestor of Bos taurus (the western cow) and Bos indicus(the zebu) may have lived as much as 1m years ago¬well before Homo sapiens existed.

'Til the cows come home

In Africa, the story is more confusing. African cattle have features of both Bos taurus and Bos indicus, but their mitochondrial DNA suggests that, despite this apparently intermediate nature, they all belong to Bos taurus. Mitochondrial DNA, however, is unusual in being passed down only from mothers to offspring (sperm leave their mitochondria behind when they fertilise an egg). When Dr Bradley examined the nuclear DNA of cattle, and in particular that of their Y chromosomes, which confer maleness, he found a different picture.

Zebu-like cattle in Africa did, indeed, turn out to have Indian genes in them. But those genes have come, overwhelmingly, from male Indian cattle. That suggests cattle originally came to Africa from the Middle East , as geography might predict. But it also suggests that, when trade eventually brought Indian cattle to Africa, the zebu took the fancy of African stock-breeders, who deliberately studded their females with Indian males. That explains the mixture of characteristics, and also why the female-linked DNA looks Middle Eastern and the male-linked DNA looks Indian.

Cattle are not the only animals to have been domesticated on more than one occasion. Mitochondrial DNA suggests that goats, sheep, pigs, yaks and buffalo were each domesticated at least twice. Dogs were domesticated at least four times. And the mitochondrial tree for horses is so tangled that it is impossible to say exactly how many times people first slung themselves into the saddle.

That is intriguing for two reasons. First, it suggests that lots of people had the idea of domesticating animals independently, rather than the process being tried out only once for each species. Second, it adds weight to the idea that the reason such a limited number of animals has been domesticated is not because people stopped when they felt they had enough species for their needs, but rather because they tried many times and frequently failed. It was only with the ancestors of the species that now grace farmyards that they got results.

Melinda Zeder of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, who studies the process by which goats were domesticated, observes that the wild forms of those species that have been domesticated tend to live in groups and have fairly clear dominance hierarchies. This makes it easy for them to fit in with humanity. Animals such as gazelles, which would, on the face of things, be good candidates for domestication, do not have such hierarchies, so they would not easily submit to the discipline that the farmyard requires. Whether the free-spirited gazelle is better off than the cosseted goat, cow or sheep is an open question.

source: http://www.economist.com/science/PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story_ID=587270

http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/150/3/1169

“…CATTLE have had an important but incompletely understood association with early human civilization, and study of their origins may enlighten us on hitherto unknown aspects of prehistory. All modern cattle have been considered to have the same roots in captured aurochsen from the primary domestication centers of Anatolia and the Fertile Crescent (PERKINS 1969; EPSTEIN 1971; EPSTEIN and MASON 1984; PAYNE 1991). However, this is an opinion that may be an artifact of the history of archaeology (MEADOW 1993). For example, LOFTUS et al. (1994) have provided molecular evidence for a predomestic divergence between zebu, or humped cattle (Bos indicus), and taurine, or humpless cattle (B. taurus), using mtDNA displacement loop (D-loop) variation. A subsequent study has also argued that modern mtDNA sequence distributions are suggestive of biologically distinct origins for the indigenous B. taurus populations of Africa and Europe (BRADLEYet al. 1996)…”

The Indian cattle is a separate branch (Fig.)

The Indian cattle is a separate branch (Fig.)

—Phylogenetic relationships among bison, Indian, African, European, and Japanese cattle populations constructed using pairwise FST distances and the neighbor-joining method.

"The earliest remains of cattle in a domestic context occur in Anatolia from at least 8000 YBP (PERKINS 1969 Down). The site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan shows evidence for cattle herding as early as 7000 YBP, and the earliest securely identified African domestic cow dates to only 500 yr later (MEADOW 1993 Down; ROUBET 1978 Down)"

"http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/master.html?http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/0\

203/0203_feature.html>

"But there is evidence that cattle were also brought under domestication farther east, in what are now Pakistan and India."

"According to our genetic analyses, African cattle originated neither from Indian humped cattle nor from Near Eastern cattle. Those findings support the separate-origins theory of cattle domestication favored by

archaeologists, who had maintained that in Africa, too, cattle domestication was local."

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/2004/4/kidsfarmside.cfm

"However, recent DNA evidence suggests that cattle evolved into different types before they were domesticated. The authors of 1994 and 1996 papers in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences believe Indian cattle diverged about 200,000 years ago and formed a genetically distinct group (B. indicus). Long before Near Eastern cattle were domesticated, the remaining group split again about 25,000 years ago into two groups that are the forebears of African and European cattle."

"Rather, cattle were independently domesticated in what are now India and Pakistan, in the Fertile Crescent, and possibly in Africa."

http://www.eva.mpg.de/evolution/staff/c_smith/pdf/Gotherstrom_et_alAurochs05.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=1\

6243693&dopt=Abstract>

J Kantanen et al., 2009, Maternal and paternal genealogy of Eurasian taurine cattle (Bos taurus), Heredity (2009) 103, 404–415; doi:10.1038/hdy.2009.68; published online 15 July 2009 http://www.nature.com/hdy/journal/v103/n5/full/hdy200968a.html “Maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has been used extensively to determine origin and diversity of taurine cattle (Bos taurus) but global surveys of paternally inherited Y-chromosome diversity are lacking. Here, we provide mtDNA information on previously uncharacterised Eurasian breeds and present the most comprehensive Y-chromosomal microsatellite data on domestic cattle to date. The mitochondrial haplogroup T3 was the most frequent, whereas T4 was detected only in the Yakutian cattle from Siberia. The mtDNA data indicates that the Ukrainian and Central Asian regions are zones where hybrids between taurine and zebu (B. indicus) cattle have existed. This zebu influence appears to have subsequently spread into southern and southeastern European breeds. The most common Y-chromosomal microsatellite haplotype, termed here as H11, showed an elevated frequency in the Eurasian sample set compared with that detected in Near Eastern and Anatolian breeds. The taurine Y-chromosomal microsatellite haplotypes were found to be structured in a network according to the Y-haplogroups Y1 and Y2. These data do not support the recent hypothesis on the origin of Y1 from the local European hybridization of cattle with male aurochsen. Compared with mtDNA, the intensive culling of breeding males and male-mediated crossbreeding of locally raised native breeds has accelerated loss of Y-chromosomal variation in domestic cattle, and affected the contribution of genetic drift to diversity. In conclusion, to maintain diversity, breeds showing rare Y-haplotypes should be prioritised in the conservation of cattle genetic resources.”

Section 2. Horse

Origin of the Light Sivalensis type Horse from India - Premendra Priyadarshi. Demolishing the Aryan Invasion theories. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2012/12/origin-of-light-sivalensis-type-horse.html

Notes on rebus readings

1. K. ḍangur m. ʻbullockʼ, L. ḍaṅgur, (Ju.) ḍã_gar m. ʻhorned cattleʼ; P. ḍaṅgar m. ʻcattleʼ, Or. ḍaṅgara; Bi. ḍã̄gar ʻold worn -- out beast, dead cattleʼ, dhūr ḍã̄gar ʻcattle in generalʼ; Bhoj. ḍāṅgar ʻcattleʼ; H. ḍã_gar, ḍã̄grā m. 'horned cattleʼ.2. H. ḍã_gar m. = prec.(CDIAL 5526). dāntá ʻ tamed ʼ TBr., m. ʻ tamed ox ʼ Rājat. [√dam]Pa. danta -- ʻ tamed ʼ, Pk. daṁta -- ; Gy. as. danda ʻ bull ʼ; Ḍ. dōn, pl. dāna m. ʻ castrated bullock ʼ (← Sh.?); Dm. dân ʻ bull ʼ, Kal. dōn, obl. dōndas; Sh.gil. gur. dōnṷ m. ʻ bull ʼ (Lor. ʻ castrated bullock ʼ), jij. dɔ̈̄du; K. dã̄d m. ʻ bull, bullock ʼ, kash. dānd, rām. pog. ḍoḍ. dānt, S. ḍ̠ã̄du m.; L. dã̄d, mult. ḍã̄d m. ʻ bullock fit for the plough ʼ, awāṇ. dã̄d ʻ bull ʼ, WPah. cam. dānd, bhad. bhal. cur. khaś. dānt.(CDIAL 6273).

Ka. aduru native metal. Tu. ajirda karba very hard iron.Ta. ayil iron. Ma. ayir, ayiram any ore. (DEDR 272).

Brahmiṇi or Brahmaṇi bull is also called the zebu. It has a pronounced hump, long horns, droopy ears and a large dewlap. Scientific name was originally bos indicus; it is called bos taurus indicus adapted to tropical environments, domesticated in Bharat over 10,000 years ago. It is allowed to roam free in many parts of Bharat, considered a sacred bull; this may have led to the name Brahmani. adar, adar ḍangra a brahmini bull, a bull kept for breeding purposes and not put to work (Santali) It is also called khunt, khūṭ Brahmani bull (Kathiawar G.); khūṭṛo entire bull used for agriculture, not for breeding (G.)(CDIAL 3899). Decoded rebus: khūṭ ˜community (Guild). Cf. khūṭ a community, sect, society, division, clique, schism, stock (Santali) The zebu (Brahmaṇi bull) is: aḍar ḍangra (Santali); rebus: aduru = gaṇiyinda tegadukaragade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka.) ḍhangar ˜blacksmith (Mth.)

Decoding epigraphs on seals, Mohenjodaro1118 and Kalibangan 032 : ayaskāṇḍa (of) aḍar ḍangra khūṭ ˜native-metal-blacksmith (making) excellent metal. kamari 'dewlap'; rebus: kamar 'artisan'.

Read on...http://www.docstoc.com/docs/16253614/ayas1