Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah (the Sabah Collection of Islamic Art)

The al-Sabah Collection contains almost two thousand items of metalwork ranging from elaborately worked vessels inlaid with precious metals to simply cast bronze finials in the form of animals. Islamic metalworkers, whether in Cairo or Herat, often fashioned relatively simple forms covered the surface in dazzling engraved or precious metal-inlaid patterns of arabesque interlace, processions of animals or long benedictory inscriptions. Objects with calligraphy as decoration occur more frequently in metalwork than any other medium used for objects of utility. These range from benedictory inscriptions to verses from the Qur’an to lines of poetry, and sometimes include the signatures of the artists.

The ancient Near East has a long history of working in copper alloy and bronzes and brasses (copper alloyed with other metals) became the most important material in the mediaeval period. Objects are almost invariably sculpturally powerful, and examples of everyday objects such as oil lamps or incense burners became works of art. Brass was especially popular in the Mamluk domains. In the later period, especially in Iran and India, steel was used for decorative purposes; despite its hardness, it could be cut in openwork patterns, such as arabesques and calligraphic compositions as delicate as lace. View some of the collections at: http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/the-collections/metals/

![]() Gold disc. Kuwait Museum. Source: http://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture

Gold disc. Kuwait Museum. Source: http://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture

It will be interesting to obtain provenance information from the Museum and have experts evaluate the authenticity of the artifact.

Primafacie, the gold disc has hieroglyphs ALL OF which occur on other Indus writing artifacts such as seals and tablets.

In the context of the bronze-age, the hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha) speech as metalware catalogs.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-as-metalware-catalogs-and_21.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/tokens-and-bullae-evolve-into-indus.html

See examples of Dilmun seal readings at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html

See examples of Sumer Samarra bowls: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-writing-in-ancient-near-east.html

4. A pair of bulls tethered to the tree branch: ḍhangar 'bull'; rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith'

Why are animals shown in pairs?

dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Mu.)

Kalyanaraman

May 31, 2013

PS: Further links.

The al-Sabah Collection is regarded by international authorities as one of a small handful of the most comprehensive collections of Islamic art in the world. It has continued to grow since its inception increasing its strengths in all categories.

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/

Excerpts from brochure 'Splendors of the Ancient East':

![]() Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. L. 47 cm. w. 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical coper and then joined by casting; left eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forehead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern). Inv. no. LNS 1653M

Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. L. 47 cm. w. 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical coper and then joined by casting; left eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forehead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern). Inv. no. LNS 1653M

![]() Copper alloy and silver standing nude male supporting openwork basket. Mesopotami, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE Ht. 115 cm. width 33 cm. Figure of arsenical copper with silver head, lost-wax cast, with engraved details; with attached silver sidelocks; inlaid shell eye In. no. LNS 1654M

Copper alloy and silver standing nude male supporting openwork basket. Mesopotami, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE Ht. 115 cm. width 33 cm. Figure of arsenical copper with silver head, lost-wax cast, with engraved details; with attached silver sidelocks; inlaid shell eye In. no. LNS 1654M

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Splendour-Exhibition-Brochure.pdf![]() http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/loans-from-the-kuwait-national-museum/Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/loans-from-the-kuwait-national-museum/Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Failaka Island is located approximately 20 km northeast of Kuwait City. The island has a shallow surface measuring 12 km in length and 6 km width. The island proved to be an ideal location for human settlements, because of the wealth of natural resources, including harbours, fresh water, and fertile soil. It was also a strategic maritime commercial route that linked the northern side of the Gulf to the southern side. Studies show that traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC and extended through most of the 20th century CE.

Failaka was first known as Agarum, the land of Enzak, the great god of Dilmun civilisation according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island. Dilmun was the leading commercial hub for its powerful neighbours in their need to exchange processed goods for raw materials. Sailing the Arabian Gulf was by far the most convenient trade route at a time as transportation over land meant a much longer and more hazardous journey. As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the activities which radiated around Dilmun (Bahrain) from the end of the 3rd millennium to the mid-1st millennium BCE.

The cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Harappan people from the Indus Valley, the inhabitants of Magan and the Iranian hinterland have left many archaeological traces of their encounters on Failaka Island. More speculative is the ongoing debate among academics on whether Failaka might be the mythical Eden: the place where Sumerian hero Gilgamesh almost unraveled the secret of immortality; the paradise later described in the Bible.

As a result of changes in the balance of political powers in the region towards the end of the 2nd millennium BCE and beginning of 1st millennium BCE, the importance of Failaka began to decline.

Studies indicate that Alexander the Great received reports from missions sent to explore the Arabian shoreline of the Gulf. The reports referenced two islands, one located approximately 120 stadia (almost 19 km) from an estuary; the second island located a complete day and night sailing journey with proper climate conditions. As the historian Aryan stated, “Alexander the Great ordered that the nearer island be named “Ikaros” (now Failaka) and the distant island as “Tylos” (now the Kingdom of Bahrain). Ikaros was described by the explorers as an island covered with rich vegetation and a shelter for numerous wild animals, considered sacred by the inhabitants who dedicate them to their local goddess.

After the collapse of the great empires in western Asia (Greek, Persian, Roman), the first centuries of the Christian era brought new settlers to Failaka. The island became a secure home for a Christian community, possibly Nestorian, until the 9th century CE. At Al- Qusur, in the centre of the island, archaeologists have uncovered two churches, built at an undetermined date, around which a large settlement grew. Its name may have changed again at that time, to Ramatha.

Failaka was continuously inhabited throughout the Islamic period until the 1990s. Excavations on the Island began in 1958 and continue today. Many archaeological expeditions have worked on Failaka and it is considered one of the key sources of knowledge about civilisations emerging from within the Gulf region.

Brochure at http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Loans-From-KNM-Brochure.pdf

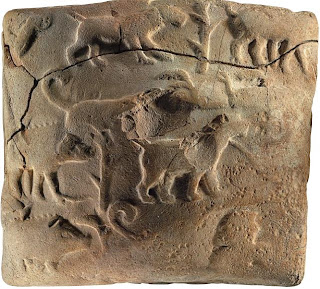

Pre-cuneiform tablet with seal impressions

![]() The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru= ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been:

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru= ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been:

Fig. 24 Line drawing showing the seal impression on this tablet. Illustration by Abdallah Kahil.

Proto-Cuneiform tablet with seal impressions. Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3100-2900 BCE. Mesopotamia. Clay H. 5.5 cm; W.7 cm.

Source: Kim Benzel, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic and Edith W. Watts, 2010, Art of the Ancient Near East, a resource for educators, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

http://www.metmuseum.org/~/media/Files/Learn/For%20Educators/Publications%20for%20Educators/Art%20of%20the%20Ancient%20Near%20East.pdf

The al-Sabah Collection contains almost two thousand items of metalwork ranging from elaborately worked vessels inlaid with precious metals to simply cast bronze finials in the form of animals. Islamic metalworkers, whether in Cairo or Herat, often fashioned relatively simple forms covered the surface in dazzling engraved or precious metal-inlaid patterns of arabesque interlace, processions of animals or long benedictory inscriptions. Objects with calligraphy as decoration occur more frequently in metalwork than any other medium used for objects of utility. These range from benedictory inscriptions to verses from the Qur’an to lines of poetry, and sometimes include the signatures of the artists.

The ancient Near East has a long history of working in copper alloy and bronzes and brasses (copper alloyed with other metals) became the most important material in the mediaeval period. Objects are almost invariably sculpturally powerful, and examples of everyday objects such as oil lamps or incense burners became works of art. Brass was especially popular in the Mamluk domains. In the later period, especially in Iran and India, steel was used for decorative purposes; despite its hardness, it could be cut in openwork patterns, such as arabesques and calligraphic compositions as delicate as lace. View some of the collections at: http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/the-collections/metals/

Gold disc. Kuwait Museum. Source: http://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture

Gold disc. Kuwait Museum. Source: http://www.facebook.com/BenoyKBehlArtCulture- Indus Valley trade with Mesopotamia 5,000 years ago.

The most wonderful and exciting part of my trip to Kuwait was my visit to see the al-Sabah Collection of antiquities. It was a marvelous collection of ancient art.

Here, there was a Gold disc of 9.6 cm diameter, which was obviously from the Indus Valley period in India. Typical of that period, it depicts zebu, bulls, human attendants, ibex, fish, partridges, bees, an animal-headed standard and, best of all, a Pipal tree (also known as the Bodhi Tree, as Gautama Siddhartha attained enlightenment under such a tree. Buddhists believe that all the previous Buddhas found enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree and so will all future Buddhas). This would be of the 3rd Millennium BCE. The National Museum in New Delhi also has an Indus Valley seal, which depicts the Pipal tree.8 people like this. - Premola Ghose terrific!!Like · Reply · 17 hours ago

- Benoy K Behl: Art & Culture Premola Ghose, I could hardly believe it when I saw it!Like · Reply · 16 hours ago

- Come Carpentier de Gourdon Thank you. This is almost identical to teh Scythian/Saka art I admired at the Museum of Almaty in Kazakhstan recently. The Sakas were an "Indo-European" people which in turns supports the view that the Saeaswati-Indus Harappan culture was also "Indo-European" and Vedic.Like · Reply · 1 · 14 hours ago

- Shailesh Nayak Very interesting.Like · Reply · 13 hours ago

- Kailash Chaurasia 5000 ago! Beyond comprehension, mind boggling, they did have the tools, the skill, culture and creativity!Like · Reply · 13 hours ago

- Shonaleeka Kaul has it been dated? where was it found and with what else? am trying to think of ways, beyond the mere fact of animals or the ficus tree being depicted, to be sure it's Indus Valley.Like · Reply · 8 hours ago

It will be interesting to obtain provenance information from the Museum and have experts evaluate the authenticity of the artifact.

Primafacie, the gold disc has hieroglyphs ALL OF which occur on other Indus writing artifacts such as seals and tablets.

In the context of the bronze-age, the hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha) speech as metalware catalogs.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-as-metalware-catalogs-and_21.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/tokens-and-bullae-evolve-into-indus.html

See examples of Dilmun seal readings at http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html

See examples of Sumer Samarra bowls: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-writing-in-ancient-near-east.html

In this perspective, the hieroglyphs on the Kuwait Museum gold disc can be read rebus:

1. A pair of tabernae montana flowers tagara 'tabernae montana' flower; rebus: tagara 'tin'

2. A pair of rams tagara 'ram'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

3. Ficus religiosa leaves on a tree branch (5) loa 'ficus leaf'; rebus: loh 'metal'. kol in Tamil means pancaloha 'alloy of five metals'.

4. A pair of bulls tethered to the tree branch: ḍhangar 'bull'; rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith'

Two persons touch the two bulls: meḍ ‘body’ (Mu.) Rebus: meḍ‘iron’ (Ho.) Thus, the hieroglyph composition denotes ironsmiths.

5. A pair of antelopes looking back: krammara 'look back'; rebus: kamar 'smith' (Santali); tagara 'antelope'; rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

6. A pair of antelopes mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Mu.)

7. A pair of combs kã̄gsī f. ʻcombʼ (Gujarati); rebus 1: kangar ‘portable furnace’ (Kashmiri); rebus 2: kamsa 'bronze'.

8. A pair of fishes ayo 'fish' (Mu.); rebus: ayo 'metal, iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Sanskrit)

9.A pair of buffaloes tethered to a post-standard kāṛā ‘buffalo’ கண்டி kaṇṭi buffalo bull (Tamil); rebus: kaṇḍ 'stone ore'; kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

ṭhaṭera ‘buffalo horns’. ṭhaṭerā ‘brass worker’ (Punjabi)

dol‘eye’; Rebus: dul‘to cast metal in a mould’ (Santali)

kandi‘hole, opening’ (Ka.)[Note the eye shown as a dotted circle on many Dilmun seals.]; kan‘eye’ (Ka.); rebus: kandi (pl. –l) necklace, beads (Pa.); kaṇḍ 'stone ore'

khuṇḍʻtethering peg or post' (Western Pahari) Rebus: kūṭa‘workshop’; kuṭi= smelter furnace (Santali); Rebus 2: kuṇḍ 'fire-altar'

Why are animals shown in pairs?

dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul ‘cast metal’ (Mu.)

Thus, all the hieroglyphs on the gold disc can be read as Indus writing related to one bronze-age artifact category: metalware catalog entries.

Most of the inscriptions have been listed in the book available through flipkart.com: http://tinyurl.com/c3q4pmj

Kalyanaraman

May 31, 2013

PS: Further links.The al-Sabah Collection is regarded by international authorities as one of a small handful of the most comprehensive collections of Islamic art in the world. It has continued to grow since its inception increasing its strengths in all categories.

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/

Excerpts from brochure 'Splendors of the Ancient East':

Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. L. 47 cm. w. 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical coper and then joined by casting; left eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forehead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern). Inv. no. LNS 1653M

Copper alloy stand in the form of a Markhor goat supporting an elaborate superstructure. Mesopotamia, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE. Ht. 67 cm. L. 47 cm. w. 33 cm. Body cast from speiss alloy (iron-arsenic-copper); all other parts separately lost-wax cast from arsenical coper and then joined by casting; left eye retaining shell inlay; triangular forehead depression inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (probably modern). Inv. no. LNS 1653MMiṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)

Iron age? Silver pouring vessel with handle and double spout in the form of two bulls. Elamite, southern Iran. 7th to 6th cent. BCE or earlier. Ht. 28.4 cm to top of handle; depth 24.7 cm including spouts. Raised from silver sheet, hammered, engraves and chased. Long votive inscription in Elamite in the name of King Shutur-Nahhunte-Inshushinak (rad by WG Lambert and R. Kovacs). Inv. no. LNS 1276M

'The Ancient Near East encompasing modern-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq, the whole of the Arabian Peninsula, and the Levant, is an enormous area that was connected by an extraordinary degree of contact. Other areas further east were also of great importance in the thre millennia before Islam, particularly the Bronze Age civilizations of the Indus Valley in modern-day India and Pakistan, and the culture in Central Asia referred to as Bactria-Margiana in what is now eastern Turkmenistan, western Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan. In the first millennium BCE most of these areas continued to flourish as dynasties rose and fell, and waves of Central Asian nomads brought their own cultural contribution to the arts of the region. These cross-cultural influences are apparent in many of the objects presented here.'

Splendour Exhibition Brochure, Amricani Cultural Centre, Gulf Road, across the street from the National Assembly (the Historic American Hospital Buildings). email: info@darmuseum.org.kw friends@darmuseum.org.kw

Copper alloy and silver standing nude male supporting openwork basket. Mesopotami, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE Ht. 115 cm. width 33 cm. Figure of arsenical copper with silver head, lost-wax cast, with engraved details; with attached silver sidelocks; inlaid shell eye In. no. LNS 1654M

Copper alloy and silver standing nude male supporting openwork basket. Mesopotami, Early Dynastic I, 2900 to 2700 BCE Ht. 115 cm. width 33 cm. Figure of arsenical copper with silver head, lost-wax cast, with engraved details; with attached silver sidelocks; inlaid shell eye In. no. LNS 1654MGold cylinder seal depicting complex mythological scenes. Possibly southeastern Iran, mid 3rd millennium BCE. Ht. 2.21 cm. dia. 2.74 cm. Fabricated from gold sheet with chased decoration. Inv. No. LNS 4517J

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/loans-from-the-kuwait-national-museum/Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/loans-from-the-kuwait-national-museum/Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]Failaka Island is located approximately 20 km northeast of Kuwait City. The island has a shallow surface measuring 12 km in length and 6 km width. The island proved to be an ideal location for human settlements, because of the wealth of natural resources, including harbours, fresh water, and fertile soil. It was also a strategic maritime commercial route that linked the northern side of the Gulf to the southern side. Studies show that traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC and extended through most of the 20th century CE.

Failaka was first known as Agarum, the land of Enzak, the great god of Dilmun civilisation according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island. Dilmun was the leading commercial hub for its powerful neighbours in their need to exchange processed goods for raw materials. Sailing the Arabian Gulf was by far the most convenient trade route at a time as transportation over land meant a much longer and more hazardous journey. As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the activities which radiated around Dilmun (Bahrain) from the end of the 3rd millennium to the mid-1st millennium BCE.

The cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Harappan people from the Indus Valley, the inhabitants of Magan and the Iranian hinterland have left many archaeological traces of their encounters on Failaka Island. More speculative is the ongoing debate among academics on whether Failaka might be the mythical Eden: the place where Sumerian hero Gilgamesh almost unraveled the secret of immortality; the paradise later described in the Bible.

As a result of changes in the balance of political powers in the region towards the end of the 2nd millennium BCE and beginning of 1st millennium BCE, the importance of Failaka began to decline.

Studies indicate that Alexander the Great received reports from missions sent to explore the Arabian shoreline of the Gulf. The reports referenced two islands, one located approximately 120 stadia (almost 19 km) from an estuary; the second island located a complete day and night sailing journey with proper climate conditions. As the historian Aryan stated, “Alexander the Great ordered that the nearer island be named “Ikaros” (now Failaka) and the distant island as “Tylos” (now the Kingdom of Bahrain). Ikaros was described by the explorers as an island covered with rich vegetation and a shelter for numerous wild animals, considered sacred by the inhabitants who dedicate them to their local goddess.

After the collapse of the great empires in western Asia (Greek, Persian, Roman), the first centuries of the Christian era brought new settlers to Failaka. The island became a secure home for a Christian community, possibly Nestorian, until the 9th century CE. At Al- Qusur, in the centre of the island, archaeologists have uncovered two churches, built at an undetermined date, around which a large settlement grew. Its name may have changed again at that time, to Ramatha.

Failaka was continuously inhabited throughout the Islamic period until the 1990s. Excavations on the Island began in 1958 and continue today. Many archaeological expeditions have worked on Failaka and it is considered one of the key sources of knowledge about civilisations emerging from within the Gulf region.

Brochure at http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Loans-From-KNM-Brochure.pdf

Pre-cuneiform tablet with seal impressions

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru= ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been:

The imagery of the cylinder seal records information. A male figure is guiding dogs (?Tigers) and herding boars in a reed marsh. Both tiger and boar are Indus writing hieroglyphs, together with the imagery of a grain stalk. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha (mleccha),of Indian sprachbund in the context of metalware catalogs of bronze age. kola 'tiger'; rebus: kol 'iron'; kāṇḍa 'rhino'; rebus: kāṇḍa 'metalware tools, pots and pans'. Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru= ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330) Alternative rebus: If the imagery of stalk connoted a palm-frond, the rebus readings could have been: Ku. N. tāmo (pl. ʻ young bamboo shoots ʼ), A. tām, B. tã̄bā, tāmā, Or. tambā, Bi tã̄bā, Mth. tām, tāmā, Bhoj. tāmā, H. tām in cmpds., tã̄bā, tāmā m. (CDIAL 5779) Rebus: tāmrá ʻ dark red, copper -- coloured ʼ VS., n. ʻ copper ʼ Kauś., tāmraka -- n. Yājñ. [Cf. tamrá -- . -- √tam?] Pa. tamba -- ʻ red ʼ, n. ʻ copper ʼ, Pk. taṁba -- adj. and n.; Dm. trāmba -- ʻ red ʼ (in trāmba -- lac̣uk ʻ raspberry ʼ NTS xii 192); Bshk. lām ʻ copper, piece of bad pine -- wood (< ʻ *red wood ʼ?); Phal. tāmba ʻ copper ʼ (→ Sh.koh. tāmbā), K. trām m. (→ Sh.gil. gur. trām m.), S. ṭrāmo m., L. trāmā, (Ju.) tarāmã̄ m., P. tāmbā m., WPah. bhad. ṭḷām n., kiũth. cāmbā, sod. cambo, jaun. tã̄bō (CDIAL 5779) tabāshīr तबाशीर् । त्वक््क्षीरी f. the sugar of the bamboo, bamboo-manna (a siliceous deposit on the joints of the bamboo) (Kashmiri)

Proto-Cuneiform tablet with seal impressions. Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3100-2900 BCE. Mesopotamia. Clay H. 5.5 cm; W.7 cm.

Source: Kim Benzel, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic and Edith W. Watts, 2010, Art of the Ancient Near East, a resource for educators, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

http://www.metmuseum.org/~/media/Files/Learn/For%20Educators/Publications%20for%20Educators/Art%20of%20the%20Ancient%20Near%20East.pdf