Mirror:

https://www.academia.edu/9818724/Gondwana_Indus_script_on_19_pictographs_from_a_cave_in_Talwarghatta_Hampi_Godavari_river_basin

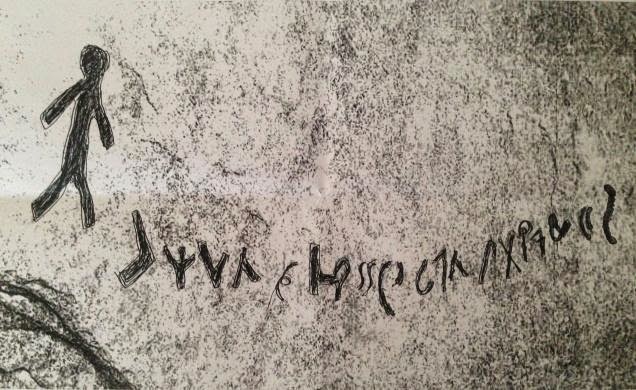

This is a photograph of the inscription with 19 pictographs.

Reference earlier post, one pictograph, 'standing person' is clearly identifiable as comparable to the Indus Script corpora of 'signs' and 'pictorial motifs'. In the corpora, the hieroglyph is read rebus as:

Reference earlier post, one pictograph, 'standing person' is clearly identifiable as comparable to the Indus Script corpora of 'signs' and 'pictorial motifs'. In the corpora, the hieroglyph is read rebus as: meḍ 'body' (Santali. Munda)Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’(Munda)kāṭi 'body stature; Rebus: fireplace trench.

Identification of other 18 pictographs of the cave inscription will help match with comparable deciphered hieroglyphs of Indus writing.

Kalyanaraman

Published: January 20, 2014 00:00 IST | Updated: January 20, 2014 08:46 IST

Gondi manuscript translation to reveal Gondwana history

A hidden, tiny and yet, extremely important part of India’s modern history will soon be revealed to the world once the translation of the Gunjala Gondi manuscripts is completed within the next week. The manuscripts, written in the extinct Gondi script, subsequently named the Gunjala Gondi script, were discovered in the sleepy village of Narnoor mandal in Adilabad district in 2011, leading to a whole range of possibilities, especially in historical research.

The Centre for Dalit and Adivasi Studies and Translation (CDAST) of the University of Hyderabad, with Professor V. Krishna as its coordinator, has undertaken translation of ten manuscripts which talk of the history of the Gond Kingdom of Chandrapur (in present day Maharashtra), besides depicting Gondi culture in the form of the Ramayana. A team from CDAST is currently translating the manuscripts dating back to 1750 at Gunjala with the help of Gondi pandits.

The manuscripts will be translated to Hindi and Telugu for the benefit of the Gond community spread across six States, as well as non-Gonds. Meanwhile, the font for the Gunjala Gondi script has already been finalised.

“The manuscripts talk about the freedom struggle of the Chandrapur Gond Kings who fought against the British, and the history of the Pardhan tribe which has an intrinsic and inseparable connection with the Gonds. One of the episodes relate to the rebellion of the legendary Ramji Gond who fought the British at Nirmal town in Adilabad district with the help of Rohillas,” said Professor Jayadheer Tirumal Rao, visiting Professor at CDAST, who was instrumental in bringing to light the discovery.

One of the important aspects in the life of Gond Kings highlighted in the manuscripts was their relationship with Myanmar (then known as Burma). The relationship was forged by people from the Pardhan community in the 6th or 7th Century CE.

“There is a record of the origins of the famous Nagoba Jatara at Keslapur in Indervelli mandal which is an important chapter in the history of Gondwana. The translation will also help us understand the relation between different communities in those times,” Mr. Rao added.

http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-andhrapradesh/gondi-manuscript-translation-to-reveal-gondwana-history/article5595317.ece

Published: December 16, 2014 23:46 IST | Updated: December 17, 2014 00:55 IST

Gonds may have migrated from Indus Valley

The Hindu

CRUCIAL LINK TO THE PAST: The photograph found in a cave in Hampi. Photo: Special Arrangement.“On the goddess Kotamma temple woollen market way there is a rocky roof shelter for shepherds and sheep to stay at night up to morning.” This innocuous sounding statement could actually be a revolutionary find linking the adivasi Gond tribe to the Indus Valley civilisation, which flourished between 2500 B.C. and 1750 BC.

The sentence emerged after a set of 19 pictographs from a cave in Hampi were deciphered using root morphemes of Gondi language, considered by many eminent linguists as a proto Dravidian language. Eleven of the Hampi pictographs resemble those of the civilisation, according to Dr. K.M. Metry, Head and Dean, Social Sciences, Kannada University, Hampi; Dr. Motiravan Kangali, a linguist and expert in Gondi language and culture from Nagpur, Maharashtra; and his associate Prakash Salame, also an expert in Gondi.

They were in Utnoor to participate in the 4th National workshop on standardisation of Gondi dictionary when they spoke to The Hindu about their study of the pictographs. Though the ‘discovery’ is yet to be authenticated, Dr. Metry and his associates are very optimistic about their work.

“Instead of looking at the painting from an archaeological or purely linguistic point of view, we took the cultural way to decipher the pictographs. Gondi culture being totemic, has a lot of such symbols also associated with Ghotul schools,” said Dr. Metry.

“Gondi is a proto Dravidian language and gives enough scope for studying the pictographs though its root morphemes,” observed Dr. Kangali. “Application of the root morphemes helped us in deciphering the 19 pictographs,” he added.

If the discovery stands the scrutiny of experts in the field, it would mean that the Gonds living in central and southern India could have migrated from the Indus Valley civilisation. “Meanwhile, we will continue with our work applying it to other paintings in the Hampi area to establish a Gondi-Harappan link,” the Professor said.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/telangana/gonds-may-have-migrated-from-indus-valley/article6698419.ece

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2014

Gondi Pictographs and the Indus Valley Script

The mysterious writing left behind by the Harappan or Indus Valley civilization has frustrated every attempt at translation. In fact it has proved so difficult to extract any meaning from the brief strings of signs that are all we have of the script that some linguists have argued that it can't really be a written language at all.

Which is why people are paying attention to this obscure news itemfrom India.

Of course many people have tried before to render the Indus script into proto-Dravidian, without any success. People want the Indus script to be written Dravidian because of Indo-European linguistics. Most languages of northern India derive from Sanskrit, which is an Indo-European language related to Old Persian, and the simplest way to get Sanskrit into India is to imagine a wave of invaders from central Asia sweeping over the Hindu Kush just like the Muslim invaders of medieval times. The most sensible time for this to have happened is the second millennium BCE, that is, just after the Indus Valley civilization collapsed. If the Indus script was Dravidian, that fits perfectly with this model. On the other hand there is pretty much no archaeological evidence for such an Indo-European invasion, and these days most Indian nationalists hate it.

This may be just another crazy idea cooked up by some overly imaginative professors, but I find myself hoping that this particular crazy idea turns out to have something to it.

Which is why people are paying attention to this obscure news itemfrom India.

“On the goddess Kotamma temple woollen market way there is a rocky roof shelter for shepherds and sheep to stay at night up to morning.” This innocuous sounding statement could actually be a revolutionary find linking the adivasi Gond tribe to the Indus Valley civilisation, which flourished between 2500 B.C. and 1750 BC.The Gondi people are scattered around central India, mainly in hilly areas, and were generally considered primitive by their valley and town dwelling neighbors. While those neighbors spoke Hindi or some other Indo-European language, Gondi is a Dravidian language quite close (some say) to the root language from which the many Dravidian tongues of south India derive. One odd thing about this new story is that it says nothing about the age of the Gondi inscription; just based on the photograph I would say it can't be more than a few hundred years old. It would be quite amazing if a system of signs used by seventeenth-century shepherds provided read clues toward the translation of the Indus script, lost since 1700 BCE.

The sentence emerged after a set of 19 pictographs from a cave in Hampi were deciphered using root morphemes of Gondi language, considered by many eminent linguists as a proto Dravidian language. Eleven of the Hampi pictographs resemble those of the civilisation, according to Dr. K.M. Metry, Head and Dean, Social Sciences, Kannada University, Hampi; Dr. Motiravan Kangali, a linguist and expert in Gondi language and culture from Nagpur, Maharashtra; and his associate Prakash Salame, also an expert in Gondi.

Of course many people have tried before to render the Indus script into proto-Dravidian, without any success. People want the Indus script to be written Dravidian because of Indo-European linguistics. Most languages of northern India derive from Sanskrit, which is an Indo-European language related to Old Persian, and the simplest way to get Sanskrit into India is to imagine a wave of invaders from central Asia sweeping over the Hindu Kush just like the Muslim invaders of medieval times. The most sensible time for this to have happened is the second millennium BCE, that is, just after the Indus Valley civilization collapsed. If the Indus script was Dravidian, that fits perfectly with this model. On the other hand there is pretty much no archaeological evidence for such an Indo-European invasion, and these days most Indian nationalists hate it.

This may be just another crazy idea cooked up by some overly imaginative professors, but I find myself hoping that this particular crazy idea turns out to have something to it.

http://benedante.blogspot.in/2014/12/gondi-pictographs-and-indus-valley.html

28 November 2014

New findings raise an old question: Do South Indians belong to the Indus Valley Civilisation?

Comment

http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/nation/the-eternal-harappan-script-tease

BALLARI, November 5, 2014

Updated: November 5, 2014 07:42 IST

Drawings of Harappan era discovered near Hampi

Pictographs of the Harappan era in Gondi dialect found near Hampi, Karnataka. Photo: Special Arrangement

As many as 20 drawings were found on a boulder on top of a hill near Talwarghatta, adjacent to river Tungabhadra.

Pictographs of the Sindu (Harappan) culture have been discovered on rocks near the world famous Hampi. As many as 20 drawings were found on a boulder on top of a hill near Talwarghatta, adjacent to river Tungabhadra.

Experts in Gondi script, including Dr. Moti Ravan Kangale and Sri Prakash Salame of Nagpur, have identified them as Sindu (Harappan) culture-based script in Gondi dialect.

Gond cultureThey also pointed out that such drawings are found in Chhattisgarh and also in interior structures of Gotuls (learning centres for youths) in Bastar region, K.M. Metry, Professor and Head Department of Tribal Studies, Hampi Kannada University told The Hindu.

“Dr. Kangale identified as many as five of the 20 pictographs of Gondi dialect – aalin (man), sary(road/way), nel (paddy), sukkum (star/dot), nooru (headman).

His observations strengthen the belief that Gond culture has been transmitted to the Tungabhadra basin,” Prof. Metry said. Prof. Metry felt that with this discovery, there was need for a thorough research to find out Gotuls in and around Hampi.

Decipherment of INDUS VALLEY script in GONDI language

Posted on November 10, 2014 by admin

Dr Motiravan Kangale who had claimed deciphering the Harappa script relating it to the ancient tribal Gondi script, are helping decipher the writing found in Hampi, Metry said. The discovery was made near Talwara Ghatta on the way to Vijaya Vittala Temple in the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“Dr Kangale and Salame were in Hampi between August 24 and 29 for a seminar on the Gondi language. I took them to these writings. On the spot, Kangale was able to decipher five of the 20 characters,” Metry said. The professor said that the symbols resemble symbols on the famous Pasupati Seal found in Mohenjo-Daro. “There are other such writings of symbols similar to these in other places in Hampi. Once all are studied, we can prove that the Harappans migrated to South India and a crucial link in our prehistory can be established.”

However, historians are calling for caution. Eminent historian Dr S Shettar said, “Recently there were claims of a Harappan engraving on a piece of stone in Tamil Nadu. But unlike a rock face, stone pieces and seals can travel long distances. In this case too, we need very solid evidence. If the discovery is true, it is wonderful. But it has to be viewed very carefully. From about 2000 BCE when the Harappan/Indus civilisation ended and the times of Ashoka in the 3rd Century BCE, we do not have clarity of the continuity in Indian history. The Indus civilisation has been demarcated as Early, Mature and Late Harappan.

“But the writings found there are not as clearly demarcated. Even the true nature of the Harappan writings is in question. So if you find a discovery beyond the conventional Indus Civilisation area, you have to be very careful while making any claims. You need to say which language was used, which script was used and the continuity. A language or script cannot remain stagnant for 1,000 years. This cannot happen with a single find. Let there not be empty speculation,” he said.

http://jayseva.com/decipherment-of-indus-valley-script-in-gondi-language/

Prof sees Harappan script in Hampi

One of the paintings seen on a wall near Talwara Ghatta at Hampi, which Prof. KM Metry (inset) claims to be Late Harappan writing

Historians call for caution in reading too much into hilltop paintings near heritage site

This could turn out to be one of the biggest archaeological finds in South India. Dr KM Metry, professor of tribal studies at the Kannada University, Hampi, has found prehistoric paintings on a hilltop in Hampi, which he claims is Late Harappan writing.

The series of 20 characters found resembles the Late Harappan writing of the Indus Valley Civilisation, says Metry. The professor claims that this shows that after the collapse of the civilisation situated in North-West India, the Harappans moved to other parts of the country including the Deccan.

Speaking to Mirror, Metry said, "There is a direct link between the Late Harappan and the writings that have been discovered. This proves that the people of Indus Valley Civilisation moved to South India after the collapse of the Late Harappan stage."

Dr Motiravan Kangale and Prakash Kalame, who had claimed deciphering the Harappa script relating it to the ancient tribal Gondi script, are helping decipher the writing found in Hampi, Metry said. The discovery was made near Talwara Ghatta on the way to Vijaya Vittala Temple in the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

"Dr Kangale and Kalame were in Hampi between August 24 and 29 for a seminar on the Gondi language. I took them to these writings. On the spot, Kangale was able to decipher five of the 20 characters," Metry said. The professor said that the symbols resemble symbols on the famous Pasupati Seal found in Mohenjo-Daro. "There are other such writings of symbols similar to these in other places in Hampi. Once all are studied, we can prove that the Harappans migrated to South India and a crucial link in our prehistory can be established."

However, historians are calling for caution. Eminent historian Dr S Shettar said, "Recently there were claims of a Harappan engraving on a piece of stone in Tamil Nadu. But unlike a rock face, stone pieces and seals can travel long distances. In this case too, we need very solid evidence. If the discovery is true, it is wonderful. But it has to be viewed very carefully. From about 2000 BCE when the Harappan/Indus civilisation ended and the times of Ashoka in the 3rd Century BCE, we do not have clarity of the continuity in Indian history. The Indus civilisation has been demarcated as Early, Mature and Late Harappan.

This could turn out to be one of the biggest archaeological finds in South India. Dr KM Metry, professor of tribal studies at the Kannada University, Hampi, has found prehistoric paintings on a hilltop in Hampi, which he claims is Late Harappan writing.

The series of 20 characters found resembles the Late Harappan writing of the Indus Valley Civilisation, says Metry. The professor claims that this shows that after the collapse of the civilisation situated in North-West India, the Harappans moved to other parts of the country including the Deccan.

Speaking to Mirror, Metry said, "There is a direct link between the Late Harappan and the writings that have been discovered. This proves that the people of Indus Valley Civilisation moved to South India after the collapse of the Late Harappan stage."

Dr Motiravan Kangale and Prakash Kalame, who had claimed deciphering the Harappa script relating it to the ancient tribal Gondi script, are helping decipher the writing found in Hampi, Metry said. The discovery was made near Talwara Ghatta on the way to Vijaya Vittala Temple in the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

"Dr Kangale and Kalame were in Hampi between August 24 and 29 for a seminar on the Gondi language. I took them to these writings. On the spot, Kangale was able to decipher five of the 20 characters," Metry said. The professor said that the symbols resemble symbols on the famous Pasupati Seal found in Mohenjo-Daro. "There are other such writings of symbols similar to these in other places in Hampi. Once all are studied, we can prove that the Harappans migrated to South India and a crucial link in our prehistory can be established."

However, historians are calling for caution. Eminent historian Dr S Shettar said, "Recently there were claims of a Harappan engraving on a piece of stone in Tamil Nadu. But unlike a rock face, stone pieces and seals can travel long distances. In this case too, we need very solid evidence. If the discovery is true, it is wonderful. But it has to be viewed very carefully. From about 2000 BCE when the Harappan/Indus civilisation ended and the times of Ashoka in the 3rd Century BCE, we do not have clarity of the continuity in Indian history. The Indus civilisation has been demarcated as Early, Mature and Late Harappan.

"But the writings found there are not as clearly demarcated. Even the true nature of the Harappan writings is in question. So if you find a discovery beyond the conventional Indus Civilisation area, you have to be very careful while making any claims. You need to say which language was used, which script was used and the continuity. A language or script cannot remain stagnant for 1,000 years. This cannot happen with a single find. Let there not be empty speculation," he said.

A BYGONE ERA

Out of the 20 symbols, Kangale and Kalame were able to immediately decipher five, says Metry. "They are: Sl No 1, which means aalin in Gondi,manava in Kannada, and man in English; Sl No 3, nel in Gondi, nela/nellu in Kannada, paddy field in English; Sl No 8, sary in Gondi, sari/daari inKannada, way/path in English; Sl No 15, sukkum in Gondi, chukke in Kannada, star/dot in English; and Sl No 16, nooru in Gondi, nara manava/mukhanda in Kannada, headman in English.

Note: From the photograph which appeared in Bangalore Mirror , it is possible to identify clearly, "standing person' symbol which is an Indus script sign.

It will be necessary to get from Prof. KM Metry, the complete set of symbols and specific symbols he sees as comparable to signs of Indus script.

From my decipherment, the 'standing person' symbol has two rebus readings: See http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/09/stature-of-body-meluhha-hieroglyphs-48.html

Stature of body Meluhha hieroglyphs (48) in Indus writing: Catalogs of Metalwork processes

meḍ 'body' (Santali. Munda) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’(Munda); मेढ meḍh‘merchant’s helper’(Pkt.) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)

kāṭi 'body stature; Rebus: fireplace trench.

काठी [ kāṭhī ] f (काष्ट S) (or शरीराची काठी ) The frame or structure of the body: also (viewed by some as arising from the preceding sense, Measuring rod) stature (Marathi) B. kāṭhā ʻ measure of length ʼ(CDIAL 3120).

Rebus: G. kāṭɔṛɔ m. ʻ dross left in the furnace after smelting iron ore ʼ.(CDIAL 2646)

Rebus: kāṭi , n. < U. ghāṭī. 1. Trench of a fort; அகழி. 2. A fireplace in the form of a long ditch; கோட்டையடுப்பு காடியடுப்பு kāṭi-y-aṭuppu , n. < காடி; +. A fireplace in the form of a long ditch used for cooking on a large scale; கோட்டையடுப்பு.

Rebus: kāṭi , n. < U. ghāṭī. 1. Trench of a fort; அகழி. 2. A fireplace in the form of a long ditch; கோட்டையடுப்பு காடியடுப்பு kāṭi-y-aṭuppu , n. < காடி; +. A fireplace in the form of a long ditch used for cooking on a large scale; கோட்டையடுப்பு.

The transcription of other symbols on the Rock inscription of Hampi and possible comparison with Indus Script sign or pictorial motif sets have to be further analysed and investigated.

Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Centre

December 18, 2014

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/11/the-eternal-harappan-script-tease.html