https://tinyurl.com/tey8da3

This monograph presents evidence of Guild-master on Indus Script inscriptions.

This monograph presents evidence of Guild-master on Indus Script inscriptions.

Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra refers to guilds of a cooperative nature as samutthachara and notes that a Superintendent of Accounts (karanika) kept a record of the customs and transactions of corporations. समुत्थ samuttha समुत्थ a. 1 Rising, getting up. -2 Sprung or produced from, born from (at the end of comp.); इच्छाद्वेष- समुत्थेन Bg.7.27; अथ नयनसमुत्थं ज्योतिरत्रेरिव द्योः R.2.75. -3 Occurring, occasioned.समुत्थानम् samutthānam समुत्थानम् 1 Rising, getting up; ...6. Engaging in industry, active occupation; as in संभूयसमुत्थानम् Ms.8.4. -7 Increase or growth. -8 Industry; यज्ञो विद्या समुत्थानम् Mb.12.23. The Superintendent of Accounts called karanika is the most frequently deployed term to signify a professional, a scribe, a supercargo, a helmsman, who documented over 8000 inscriptions on Indus Script Corpora. The hieroglyph is a conclusive proof that the profession of a Superintendent of Accounts in the days of Kautilya is a continuum of Indus Script tradition of the scribe as a supercargo. See: kárṇaka 'helmsman' karaṇika 'scribe, accountant' of Indus Script is Kernunnos venerated, adored as Tvaṣṭṛ triśiras, a horned artisan architect, metalworker smith https://tinyurl.com/yav9oxk3 The karaṇika, 'scribe' of Indus Script days evolves into the official position of Superintendent of Accounts (karanika) in the days of Kauṭilya.

:

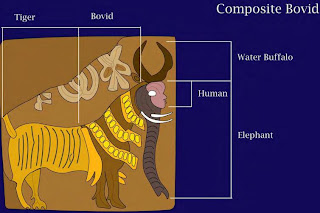

See: Tiger narratives of Indus Script document export trade. pã̄ḍyā ʻhalf-grown tiger-cub' rebus pāṇḍyā 'customs registrar' https://tinyurl.com/vcy2x4s

pāṇḍyā 'customs registrar' is traceable to the Indus Script hieroglyph pã̄ḍyā ʻhalf-grown tiger-cub and Potr̥ 'purifier priest' is a tradition continuum of poddār 'assayer of metals, silversmith; पोतदार pōtadāra m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith.पोतदारी pōtadārī f ( P) The office or business of पोतदार: also his rights or fees.पोतनिशी pōtaniśī f ( P) The office or business of पोतनीस.pōtanīsa m ( P) The treasurer or cash-keeper. The continuum of such village officials in the category of twelve artisans who are बलुतेदार or बलुता balutēdāra entitled to the share of the produce of a village or janapada is emphatic validation of the continuum of śreṇi, seṇi 'guild' dharma from the days of Tin-Bronze Revolution of Sarasvati Civilization, ca. 4th millennium BCE, into the historical periods documented in the Science of Polity, Economy & Statecraft called अर्थशास्त्र,Arthaśāstra of Kautilya dated to ca. 3rd century BCE.

A manager or president of a guild who was called a śreṣṭhin. This position is comparable to the Chairman of Board of Directors in a modern corporation. The Indus Script hieroglyph which signifies a śreṣṭhin is a squirrel. . In Gupta age (2nd century to 5th century) śreṣṭhins, sārthavahas, prathamakulikas (Head of a local guild) and prathamakāyastha (Head Accounts – Officer) figured in town and district councils. Early Buddhist texts refer to the head of a guild as the jetthaka or pamukkha e.g. 'head of garland makers' (malakara jetthaka), 'head of carpenters' guild' (vaddhaki jetthaka).

Some guilds maintained armies which accompanied trade caravans; śreṇibala or āyudha śreṇis (guilds of arms) also existed.

"The guild in ancient India was not merely the means for the development of arts and crafts. Through autonomy and freedom accorded to it by the law of the land, it became a center of strength and abode of liberal culture and progress, which truly made it a power and ornament of the society". (Majumdar, R.C.,1920, Corporate Life in Ancient India, 3rd ed., Calcutta, 1969, titled as Corporate Life).

Sangha or Gaṇa mukhya (Chief of a corporation) was responsible for implementing action approved by the Sangha (community as corporation).

The corporate form of śreṇi has clearly stipulated rules of ethical behavior. It emphasizes nihśreyas 'beatitude' and abhyudayam 'social welfare' which constitute the twin facets of dharma , the inviolate, universal, eternal ethic. Kauṭilya noted that there were two kinds of janapada ‘republics’: ayudhiya-praya, those made up mostly of soldiers, and śreṇi-praya , those comprising guilds of craftsmen, traders, and agriculturalists. (Agrawala, V.S., 1963, India as Known to Panini: A study of the cultural material in the Aṣṭādhyāyi, 2nd edn. rev. and enl. Varanasi, pp. 436-439). Rules and regulations of the corporation are called sāmayika. The rules were enforced on violators: e.g., "those who cause dissension among the members of an association shall undergo punishment of a specially severe kind; because they would prove extremely dangerous, like an (epidemic) disease, if they were allowed to go free." (cf. Nārada X.1, 6).The sippa (craftsmanship or competence), not jāti was the distinguishing determinant. Mūgapakkha jātaka refers to a ruler who assembled the four varṇas and 18 śreṇi. Such extended families of the same or different jāti included: "1. Workers in wood (carpenters, including cabinetmakers, wheel-wrights, builders of houses, builders of ships and builders of vehicles of all sorts).2. Workers in metal, including gold and silver. 3. Leather workers.4. Workers in stone.5. Ivory workers.6. Workers fabricating hydraulic engines (Odayantrika).7. Bamboo workers (vasakara)8. Braziers (kasakara).9 Jewellers.10. Weavers.11. Potters.12. Oilmillers ( Tilapiṣaka).13. Rush workers and basket makers.14. Dyers.15. Painters.16. Corn-dealers (Dhamñika).17. Cultivators.18. Fisher folk.19. Butchers. 20. Barbers and shampooers.21. Garland makers and flower sellers. 22. Mariners.23. Herdsmen.24. Traders, including caravan traders.25. Robbers and free-booters.26. Forest police who guarded the caravans. 27. Money-lenders 28. Rope and mat-makers.29. Toddy-drawers. 30.Tailors.31. Flour-makers." (opcit.Majumdar, pp.15-17). One śreṇi of vēḷaikkāra of chola agreed thus: "We protect the villages belonging to the temple, its servants' property and devotees, even though, in doing this, we lose ourselves or otherwise suffer. We provide for all the requirements of the temple so long as our community continues to exist, repairing such parts of the temple as get dilapidated in course of time and we get this, our contract, which is attested by us, engraved on stone and copper so that it may last as long as the Moon and the Sun endure." (Government Epigraphist's Report. 1913, p. 101) (p.29). Such voluntary statutes -- with perpetual endowments made by members of the guilds -- emphasizing social, ethical responsibility, explain the role played by such corporate forms for creation of the wealth of the nation and the dotting of the entire nation with thousands of public or secular and religious structures like temples, performance of samskāras (religious observances) public assembly buildings, gardens, tanks and irrigation systems.

śreṇi is a distinct and unique corporate form and is quite different from the 'league' or 'federation' organizations of city-states in vogue -- often called koinon-- in Europe in centuries prior to Common Era. This monograph posits that the concept of the 'commonwealth' is the founding principle of a śreṇi where all the proceeds of trade transactions and economic production transactions are taken into the treasury and shared among the artisans of the village republic. This 'commonwealth' tradition of śreṇi as corporate form is traceable to the system of balutedar in vogue in Ancient India, ca. 4th millennium BCE. See:

While koinon are comprehensive 'state' federations, śreṇi is specific to the guild of artisans and seafaring merchants, a tradition of Ancient India which dates back to the evidence provided by Indus Script Inscriptions (from ca. 3300 BCE). It is possible that koinon form of feration or league of states is an evolution from the śreṇi corporate form of guilds of artisans and merchants. Koinon (Greek: Κοινόν, pl. Κοινά, Koina) means 'common' or 'public' roughly comparable to Latin res publica, "the public thing." The adjective also applies to "commonwealth," the government of a single state, such as the Athenian. The Greek word is relatable to, neuter of koinos common. Etymology: From Proto-Hellenic *koňňós, from Proto-Indo-European *ḱomyós, from *ḱóm (“with”) + *-yós (“adjectival suffix”), the ancestor of the suffix -ιος (-ios). Cognates include Latin cum, Gaulish com-, and Old English ge-

Ancient India had śreṇi or guild corporate form of organization for wealth-creation by functionaries and NO caste or jāti. https://tinyurl.com/y4u682xjThis provides evidence from archaeology (Indus Script). In one classification of 12 बलुतेदार, two functionaries are mentioned: 1. पोतदार and 2.कुळ- करणी. I submit that these two categories are traceable to the evidence gleaned from Rgveda and archaeology (Indus Script) of Sarasvati Civilization.

While koinon are comprehensive 'state' federations, śreṇi is specific to the guild of artisans and seafaring merchants, a tradition of Ancient India which dates back to the evidence provided by Indus Script Inscriptions (from ca. 3300 BCE). It is possible that koinon form of feration or league of states is an evolution from the śreṇi corporate form of guilds of artisans and merchants. Koinon (Greek: Κοινόν, pl. Κοινά, Koina) means 'common' or 'public' roughly comparable to Latin res publica, "the public thing." The adjective also applies to "commonwealth," the government of a single state, such as the Athenian. The Greek word is relatable to, neuter of koinos common. Etymology: From Proto-Hellenic *koňňós, from Proto-Indo-European *ḱomyós, from *ḱóm (“with”) + *-yós (“adjectival suffix”), the ancestor of the suffix -ιος (-ios). Cognates include Latin cum, Gaulish com-, and Old English ge-

κοινός , ή, όν An ancient Greek expression ἐκ κοινοῦ means: 'shared in common'. This expression is the closest to the śreṇi corporate form of social organization.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aalphabetic+letter%3D*k%3Aentry+group%3D138%3Aentry%3Dkoino%2Fs

Koinon can, in general, be called "league" or "federation" an association of distinct city-states in a sympoliteia. As government of a league, koinon comprised such functions as defense, diplomacy, economics, and religious practices among its member states. (Mackil, Emily (May 18, 2013). Creating a Common Polity. University of California Press. p. 347. Retrieved October 21, 2014.)

Some federations termed Koinon were:

- Ionian League (Koinon Ionon), formed in the 7th century BCE

- Koinon of the Aeinautae, recorded on an inscription which was found in Eretria, island Euboea, dated to the 5th century BCE

- Acarnanian League (Koinon ton Akarnanon), existing 5th century BCE to c. 30 BCE, with interruptions

- Chalcidian League ( Koinon ton Chalkideon ), existing c. 430 to 348 BCE

- Phocian League (Koinon ton Phokeon), existing 6th century BC to 3rd century CE, with interruptions

- Thessalian League (Koinon ton Thessalon), existing 363 BCE to 3rd century CE, with interruptions

- League of the Magnetes (Koinon ton Magneton), existing 197 BCE to 3rd century CE, with interruptions

- Aenianian League ( Koinon ton Ainianon )

- Arcadian League ( Koinon ton arches )

- League of the Oeteans ( Koinon ton Oitaion )

- Euboean League ( Koinon ton Euboieon )

- Epirote League (Koinon Epiroton), existing from c. 320 to c. 170 BCE

- League of the Islanders (Koinon ton Nesioton), existing from c. 314 to c. 220 BCE and 200 to 168 BCE

- Cretan League under the Roman Empire to the 4th century

- Koinon of Macedonians existing from 3rd century to Roman period

- Lycian League, founded in 168 BCE

- League of Free Laconians, a league of cities in Laconia established by Roman emperor Augustus in 21 BCE

- Koinon of the Zagorisians under the Ottoman Empire, 1670–1868

- Aetolian League (Koinon ton Aitolon), early 3rd century BCE to roughly 189 BCE when it came under Roman influence

- Achaean League (Koinon ton Achaion), 280 BCE to 146 BCE, dissolved by the Romans after the Battle of Corinth (146 BCE) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koinon

A Coin of the Cypriote League. The bronze coin from the Roman period, is donated to the Bank by a member of the Board of Directors of the Group. This coin bears the legend “ΚΟΙΝΟ(Ν) ΚΥΠΡΙΩΝ” (League of the Cypriots); it was a symbol of unity among the peoples of the island; this particular coin has been the official logo of the Bank of Cyprus since 1963.

A Coin of the Cypriote League. The bronze coin from the Roman period, is donated to the Bank by a member of the Board of Directors of the Group. This coin bears the legend “ΚΟΙΝΟ(Ν) ΚΥΠΡΙΩΝ” (League of the Cypriots); it was a symbol of unity among the peoples of the island; this particular coin has been the official logo of the Bank of Cyprus since 1963.It is remarkable that Cyprus staters of mid-5th century BCE signifies a zebu -- with a pronounced dewlap and a single horn, forward thrusting -- which is a signature tune of Indus Script inscriptions.

CYPRUS. Paphos. Onasioikos, circa 450-440 BC. Stater (Silver, 22 mm, 11.10 g, 12 h). Bull standing to left on line of pellets above a line of bead and reel decoration; above, winged solar disk; to left, ankh; dotted border. Rev. 𐠙𐠃 𐠪𐠞 ( = pa-si /o-na, 'King Onasioikos' in Cypriote syllabary). Eagle standing left; to left, ankh; all within dotted border within incuse square. BMC -. Gulbenkian 809 = Jameson 2604.

CYPRUS. Paphos. Onasioikos, circa 450-440 BC. Stater (Silver, 22 mm, 11.10 g, 12 h). Bull standing to left on line of pellets above a line of bead and reel decoration; above, winged solar disk; to left, ankh; dotted border. Rev. 𐠙𐠃 𐠪𐠞 ( = pa-si /o-na, 'King Onasioikos' in Cypriote syllabary). Eagle standing left; to left, ankh; all within dotted border within incuse square. BMC -. Gulbenkian 809 = Jameson 2604. CYPRUS, Paphos. Onasi[...]. Mid 5th century BC. AR Stater (24.5mm, 11.03 g, 5h). Bull standing left on beaded double line; winged solar disk above, ankh to left; all within dotted circular border / Eagle standing left; ankh to left, pa-si o-na (= "Basi[leos] Ona[si–]" in Cypriot) around; all in dotted square border within incuse square. Destrooper-Georgiades, p. 196, 13; Zapiti & Michaelidou –; SNG Copenhagen –; Gulbenkian 809; Jameson 2604. Toned, minor die

CYPRUS, Paphos. Onasi[...]. Mid 5th century BC. AR Stater (24.5mm, 11.03 g, 5h). Bull standing left on beaded double line; winged solar disk above, ankh to left; all within dotted circular border / Eagle standing left; ankh to left, pa-si o-na (= "Basi[leos] Ona[si–]" in Cypriot) around; all in dotted square border within incuse square. Destrooper-Georgiades, p. 196, 13; Zapiti & Michaelidou –; SNG Copenhagen –; Gulbenkian 809; Jameson 2604. Toned, minor die Corporate, ethical responsibilities of a śreṇi, 'guild'.

Guilds used part of their profits for preservation and maintenance of assembly halls, watersheds, shrines, tanks and gardens, as also to help those in need such as widows, the poor and destitute. Guilds loaned money to artisans and merchants. Guilds engaged in works of piety and charity and offered donations to alleviate situations of distress in the society. A Mathura Inscription (2nd century CE) refers to the two permanent endowments of 550 silver coins each with two guilds to feed Brahmins and the poor from out of the interest money. Nasik Inscription (2nd century CE) records the endowment of 2000 kārṣapaṇas at the rate of one percent (per month) with a weavers' guild for providing cloth to bhikṣus and 1000 kārṣapaṇas at the rate of 0.75 percent (per month) with another weavers' guild for serving meals to them. Megasthenes had this to say about śreṇi : "Of several remarkable customs existing among the Indians, there is one prescribed by their [sc. Indian] ancient philosophers which one may regard as truly admirable: for the law ordains that no one among them shall, under any circumstances, be a slave, but that, enjoying freedom, they shall respect the principle of equality in all persons: for those, they thought, who have learned neither to domineer over nor to cringe to others will attain the life best adapted for all vicissitudes of life: since it is silly to make laws on the basis of equality of all persons and yet to establish inequalities in social intercourse." Megasthenes (who was a contemporary of Kauṭilya) is often criticized for the good reason that slavery and other forms of inequality did indeed exist among the Indians. But perhaps he correctly presented the views of "their ancient philosophers."

śreṇi is an ancient Indian guild – a corporate form -- of community groups such as artisans, craftsmen, traders, municipal workers, para-military or political entities. Synonyms used in ancient texts are: gaṇa, paṇi, grāma, sangha, vrāta, pūga, nigama. (pāṣaṇḍa naigama śreṇi pūga, vrata, gaṇādiṣu samrakṣet samayam rāja durgam janapade tathā -- Narada Smṛti. Sacred books of the East Series: 153-2).Gautama Dharma sūtra notes: “Laws of districts, castes, and families, when not opposed to sacred texts, are an authority…Ploughmen, merchants, herdsmen, money-lenders, and artisans (are also authority) for their respective classes.” Gautama Dharma sūtra also enjoins upon the ruler to consult guild representatives while dealing with matters concerning guilds.Viṣnu-smṛti or Vaiṣṇava Dharma sâstra or Viṣṇu-sûtra refers to guilds of metal workers and smiths of silver and gold. Some specific laws may be cited. The śreṇi was a separate legal entity which had the ability to hold property separately from its owners, construct its own rules for governing the behavior of its members, and for it to contract, sue and be sued in its own name. Some sources make reference to a government official (bhāṇḍagārika) who worked as an arbitrator for disputes amongst śreṇi from at least the 6th century BCE onwards. Profits and losses were to be shared by members in proportion to their shares and severe punishment was prescribed for those who embezzle guild property (Yājñavalkya Smṛti).

cf. Hopkins, E. Washburn, 1901, ‘Ancient and Modern Hindu Guilds’, in: India Old and New, New York, Scribner’s. http://library.du.ac.in/dspace/bitstream/1/7/9/Ancient%20And%20Modern%20Hidu%20Guilds..pdf

2. Jayaswal, K.P., 1924, Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, 2nd. and enl. ed., Bangalore (1943)

3. Jolly, Julius,1880, The institutes of Vishnu, translated by Julius Jolly, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 7 Oxford, the Clarendon Press

Khanna, Vikramaditya S., 2005, The Economic History of the Corporate Form in Ancient India, University of Michigan http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=796464

*śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ] Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723)

श्रेणि f. ( L. also m. ; according to Un2. iv , 51 , fr. √ श्रि ; connected with श्रेटी above ) a line , row , range , series , succession , troop , flock , multitude , number RV. &c; a company of artisans following the same business , a guild or association of traders dealing in the same articles Mn. MBh. &c (Monier-Williams) श्रेणिः śrēṇiḥ श्रेणिः m., f., -श्रेणी f. [श्रि-णि वा ङीप् Uṇ.4.51] 1 A line, series, row; तरङ्गभ्रूभङ्गा क्षुभितविहगश्रेणिरसना V.4.28; न षट्पदश्रेणिभिरेव पङ्कजं सशैवलासंगमपि प्रकाशते Ku.5.9; Me.28,37. -2 A flock, multitude, group; U.4. -3 A guild or company of traders, artisans &c., corporate body; न त्वां प्रकृतयः सर्वाः श्रेणीमुख्याश्च भूषिताः Rām.2.26.14; Ms.8.41; Bhāg.2.8.18. -4 A bucket. -5 The fore or upper part of anything. -Comp. -धर्माः (m. pl.) the customs of trades or guilds; Ms.8.41. -बद्ध, -बन्ध a. forming a row, being in a line; श्रेणीबन्धाद्वितन्बद्भि- रस्तम्भां तोरणस्रजम् R.1.41.(Apte) śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. [Same as *śrayaṇī -- (for ʻ line ~ ladder ʼ cf. *śrēṣṭrī -- 2 )? -- √śri ]Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; S. sīṇa f. ʻ the threads of the loom between which the warp runs ʼ; Or. seṇi ʻ row of rafters in a thatched roof, the wooden plates on which the rafters are put crosswise ʼ; Bi. senī ʻ the broad flat metal plates in a tobacconist's shop ʼ. (CDIAL 12718)

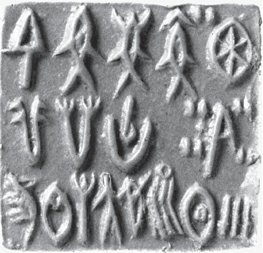

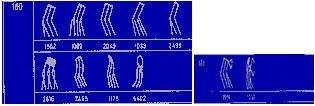

Sign 187 (Mahadevan ASI 1977 Concordance) is the 'squirrel' hieroglyph identified by Asko Parpola.

1389 Text message of m1191 A variant of a trefoil orthography: tri-dhatu'three minerals' (Alternative: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS Ta. meṭṭu mound

1389 Text message of m1191 A variant of a trefoil orthography: tri-dhatu'three minerals' (Alternative: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS Ta. meṭṭu mound'blacksmith' PLUS šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? rebus: śrēṣṭhin'guild-master'.

(Alternative reading of a hypertext: The circumfix of 'ingot' shape may have inlaid a beaded-string; the reading is: dhA 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'mineral ore' PLUS vaTa 'string' rebus: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'). Thus, the text message if from a guild-master of a smelter-guild.

Distribution of seals/tablets within House AI, Block 1, HR at Mohenjodaro (After Jansen, M., 1987, Mohenjo-daro -- a city on the Indus, in Forgotten Cities on the Indus (M. Jansen, M. Mulloy and G. Urban Eds.), Mainz, Philip Von Zabern, p. 160). Jansen speculated that the house could have been a temple.

One of the seals discovered in HR 116 which may signify a 'squirrel' hypertext.

![]() kolom 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus:khār 'blacksmith, iron worker' ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' *śrēṣṭrī

kolom 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus:khār 'blacksmith, iron worker' ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal' karNaka, kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNaka 'scribe, account' dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master khāra, 'squirrel', rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri). Thus, the inscription signifies: blacksmith guild-master working in iron in smithy/forge, metal castings handed over to Supercargo for shipment.

The glosses 1. खार [ khāra ] A squirrel, Sciurus palmarum. खारी [ khārī ] f (Usually खार ) A squirrel. (Marathi)

உறுத்தை uṟuttai, n. [T. uṟuta, K. uḍute.] Squirrel; அணில். (W .)Ta. uṟukku (uṟukki-) to jump, leap over; uṟuttai squirrel. Te. uṟu to retreat, retire, withdraw; uṟuku to jump, run away; uṟuta squirrel. Konḍa uRk- to run away. Kuwi (Isr.) urk- (-it-) to dance.(DEDR 713) Ka. uḍute squirrel. Te. uḍuta id.(DEDR 590) Ta. uruku (uruki-) to dissolve (intr.) with heat, melt, liquefy, be fused, become tender, melt (as the heart), be kind, glow with love, be emaciated; urukku (urukki-) to melt (tr.) with heat (as metals or congealed substances), dissolve, liquefy, fuse, soften (as feelings), reduce, emaciate (as the body), destroy; n. steel, anything melted, product of liquefaction; urukkam melting of heart, tenderness, compassion, love (as to a deity, friend, or child); urukkiṉam that which facilitates the fusion of metals (as borax). Ma. urukuka to melt, dissolve, be softened; urukkuka to melt (tr.); urukkam melting, anguish; urukku what is melted, fused metal, steel. Ko. uk steel. Ka. urku, ukku id. Koḍ. ur- (uri-) to melt (intr.); urïk- (urïki-) id. (tr.); ukkï steel. Te. ukku id. Go. (Mu.) urī-, (Ko.) uṛi- to be melted, dissolved; tr. (Mu.) urih-/urh- (Voc. 262). Konḍa (BB) rūg- to melt, dissolve. Kui ūra (ūri-) to be dissolved; pl. action ūrka (ūrki-); rūga (rūgi-) to be dissolved. Kuwi (Ṭ.) rūy- to be dissolved; (S.) rūkhnai to smelt; (Isr.) uku, (S.) ukku steel. (DEDR 661) Te. uḍuku to boil, seethe, bubble with heat, simmer; n. heat, boiling; uḍikincu, uḍikilu, uḍikillu to boil (tr.), cook. Go. (Koya Su.) uḍk ēru hot water. Kuwi (S.) uḍku heat. Kur. uṛturnā to be agitated by the action of heat, boil, be boiled or cooked; be tired up to excitement. Ta. (Keikádi dialect; Hislop, Papers relating to the Aboriginal Tribes of the Central Provinces, Part II, p. 19) udku (presumably uḍku) hot (< Te.) (DEDR 588)

-- The seal is of śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' who is also a ċiməkára 'coppersmith', sēṇi 'guild' khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (deploying orthography of an 'ant' hieroglyph)

The rebus readings inMeluhha (Indian sprachbund, language union) established in these annexes are:sēṇi 'ladder' rebus: sēṇi 'guild'khār 'squirrel'śrēṣṭhin 'squirrel' rebu: khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' ċima 'ant' rebus: ċiməkára 'coppersmith'

Sign ![]() on the text message on the cylinder seal could be a variant of the 'squirrel' hieroglyph, following examples from the Indus Script Corpora.

on the text message on the cylinder seal could be a variant of the 'squirrel' hieroglyph, following examples from the Indus Script Corpora.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

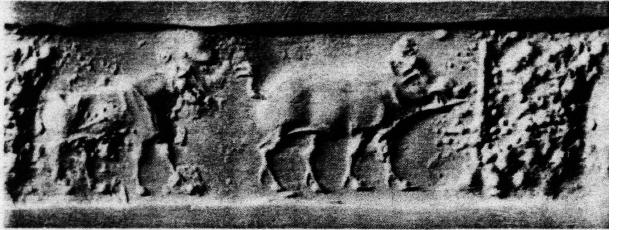

- Susa, Iran; steatite cylinder seal.Cylinder seal carved with an elongated buffalo (should read 'bull') and a Harappa inscription circa 2600-1700 BCE; Susa, Iran; Fired steatite; H. 2.3 cm; Diam. 1.6 cm; Jacques de Morgan excavations, Susa; Sb 2425; Near Eastern Antiquities; Richelieu wing; Ground floor; Iran and Susa during the 3rd millennium BC; Room 8.

- Marshall comments on a Susa cylinder seal: “…the occurrence of the same form of manger on a cylinder-seal of bone found at Susa leaves no doubt, I think, that this seal either came from India in the first instance, or, as is suggested by its very rough workmanship, was engraved for an Indian visitor to Susa by an Elamite workman…One of these five (Mesopotamian seals with Indus script) is a bone roll cylinder found at Susa, apparently in the same strata as that of the tablets in Proto-Elamitic script of the second period of painted ware. Scheil, in Delegation en Perse, vol. xvii, assigns this group of tablets and painted pottery to the period of Sargon of Agade, twenty-eighth century BCE, and some of the tablets to a period as late as the twenty-fourth century. The cylinder was first published by Scheil in Delegation en Perse ii, 129, where no precise field data by the excavator are given. The test is there given as it appears on the seal, and consequently the text is reversed. Louis Delaporte in his Catalogue des Cylindres Orientaux…du Musee du Louvre, vol. I, pl. xxv, No. 15, published this seal from an impression, which gives the proper representation of the inscription. Now, it will be noted that the style of the design is distinctly pre-Sargonic: witness the animal file and the distribution of the text around the circumference of the seal, and not parallel to its axis as on the seals of the Agade and later periods…It is certain that the design known as the animal file motif is extremely early in Sumerian and Elamitic glyptic; in fact is among the oldest known glyptic designs. But the two-horned bull standing over a manger was a design unknown in Sumerian glyptic, except on the small round press seal found by De Sarzec at Telloh and published by Heuzey, Decouvertes en Chaldee, pl. xxx, fig. 3a, and by Delaporte, Cat. I, pl. ii, t.24. The Indus seals frequently represent this same bull or bison with head bent towards a manger…Two archaeological aspects of the Susa seal are disturbing. The cylinder roll seal has not yet been found in the Indus Valley, nor does the Sumero-Elamitic animal file motif occur on any of the 530 press seals of the Indus region. It seems evident, therefore, that some trader or traveler from that country lived at Susa in the pre-Sargonic period and made a roll seal in accordance with the custom of the seal-makers of the period, inscribing it with his own native script, and working the Indian bull into a file design after the manner of the Sumero-Elamitic glyptic. The Susa seal clearly indicated a period ad quem below which this Indian culture cannot be placed, that is, about 2800 BCE. On a roll cylinder it is frequently impossible to determine where the inscription begins and ends, unless the language is known, and that is the case with the Susa seal. However, I have been able to determine a good many important features of these inscriptions and I believe that this text should be copied as follows:

- The last sign is No. 194 of my list, variant of No. 193, which is a post-fixed determinative, denoting the name of a profession, that is ‘carrier, mason, builder’, ad invariably stands at the end. (The script runs from right to left.)”[Catalogue des cylinders orient, Musee du Louvre, vol. I, pl. xxv, fig. 15. See also J. de Morgan, Prehistoric Man, p. 261, fig. 171; Mem. Del. En Perse, t.ii, p. 129.loc.cit.,John Marshall, 1931, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, Delh, AES, Repr., 2004, p.385; pp. 424-425 Note: Five cylinder seals hav since been found at Mohenjo-daro and Kalibangan.] The seal's chalky white appearance is due to the fired steatite it is made of. Craftsmen in the Indus Valley made most of their seals from this material, although square shapes were usually favored. The animal carving is similar to those found in Harappa works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger."

- Sceau-cylindre : buffle très étiré et inscription harapéenne

- (Cylinder seal with Harappan inscription, shows elongated bull, not a buffalo)

- Stéatite cuiteH. 2.3 cm; Diam. 1.6 cm

- Fouilles J. de MorganSb 2425

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 cylinder seal elongated buffalo]()

- Herbin Nancie's note on the Louvre Museum websie:This cylinder seal, carved with a Harappan inscription, originated in the Indus Valley. It is made of fired steatite, a material widely used by craftsmen in Harappa. The animal - a bull with no hump on its shoulders - is also widely attested in the region. The seal was found in Susa, reflecting the extent of commercial links between Mesopotamia, Iran, and the Indus.

A seal made in Meluhha

The language of the inscription on this cylinder seal found in Susa reveals that it was made in Harappa in the Indus Valley. In Antiquity, the valley was known as Meluhha. The seal's chalky white appearance is due to the fired steatite it is made of. Craftsmen in the Indus Valley made most of their seals from this material, although square shapes were usually favored. The animal carving is similar to those found in Harappan works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger.Trading links between the Indus, Iran, and Mesopotamia

This piece can be compared to another circular seal carved with a Harappan inscription, also found in Susa. The two seals reveal the existence of trading links between this region and the Indus valley. Other Harappan objects have likewise been found in Mesopotamia, whose sphere of influence reached as far as Susa.The manufacture and use of the seals

Cylinder seals were used mainly to protect sealed vessels and even doors to storage spaces against tampering. The surface of the seal was carved. Because the seals were so small, the artists had to carve tiny scenes on a material that allowed for fine detail. The seal was then rolled over clay to produce a reverse print of the carving. Some cylinder seals also had handles. Bibliography Amiet Pierre, L'Âge des échanges inter-iraniens : 3500-1700 av. J.-C., Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1986, coll. "Notes et documents des musées de France", p. 143 et p. 280, fig. 93. Borne interactive du département des Antiquités orientales. Les cités oubliées de l'Indus : archéologie du Pakistan, cat. exp. Paris, Musée national des arts asiatiques, Guimet, 16 novembre 1988-30 janvier 1989, sous la dir. de Jean-François Jarrige, Paris, Association française d'action artistique, 1988, pp. 194-195, fig. A5. http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-carved-elongated-buffalo-and-harappan-inscriptionGensheimer, TR, 1984, The role of shell in Mesopotamia: evidence for trfade exxchange with Oman and the Indus Valley, in: Paleorient, Vol. 10, Numero 1, pp. 65-73 http://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1984_num_10_1_4350http://www.archive.org/ Annex A Decipherment of 'ladder' hieroglyph See: Indus script seals (5) with 5 hypertext narratives signify metal Guild-master, helmsman, supercargo's in charge of products out of smelter/furnace//smithy/forge http://tinyurl.com/hrud9v4

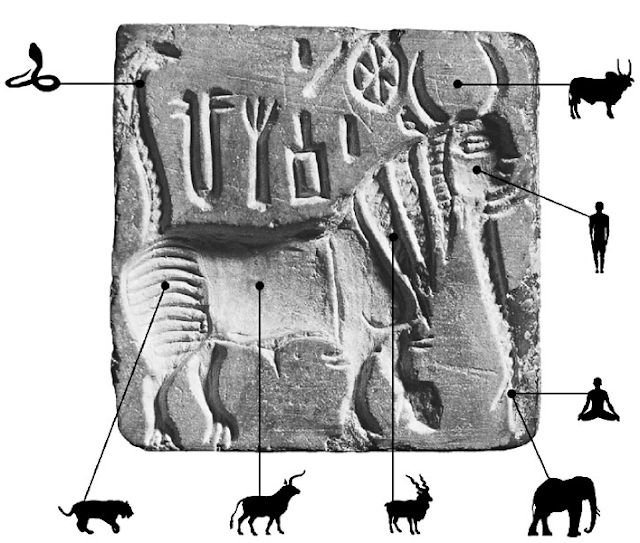

sãgaḍ f. ʻa body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together' (Marathi). This gloss sãgaḍ as a body of written or pictorial material of hieroglyphs (voiced in Meluhha speech) can be used to create a ciphertext with elements of enhanced cyber-security encryptions. This ciphertext can be called: Hieroglyphmultiplextext. Rebus 1: sãgaḍ māṇi 'alloying adamantine glue, सं-घात caravan standard' -- vajra saṁghāṭa in archaeometallurgy, deciphered in Indus Script Corpora. Enhanced encryption cyber-security. Rebus 2: जांगड [jāṅgaḍa] ad Without definitive settlement of purchase--goods taken from a shop. जांगड [ jāṅgaḍa ] f ( H) Goods taken from a shop, to be retained or returned as may suit: also articles of apparel taken from a tailor or clothier to sell for him. 2 or जांगड वही The account or account-book of goods so taken.Rebud 3: sangaDa 'a cargo boat'. Rebus 4: sangaRh 'proclamation'. சிரேணி cirēṇi தெரு. (பிங்.) 2. Herdsmen's street; இடையர் வீதி. (சூடா.) 3. Line, row, series; வரிசை. (சங். அக.) śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2 , *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri ] H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) ஏணி¹ ēṇi எண்- . cf. šrēṇi. 1. Number; எண். ஏணிபோகிய கீழ்நிலைப்படலமும் (ஞானா . 54, 1). 2. Tier; அடுக்கு. அண்டத்தேணியின் பரப்பும் (கந்தபு. சூரன்வதை . 485). 3. [K. M. Tu. ēṇi.] cf. niššrēṇī. Ladder; ஏறுதற்கருவி. மண்டலத்தூ டேற் றிவைத் தேணிவாங்கி (திவ். பெரியாழ் . 4, 9, 3).

- Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali) *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See

śrití -- . -- √śri ]

Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720) आ-श्रेतृ mfn. leaning on, resorting to (gen.), MBh.(Monier-Williams) śrití f. ʻ entrance ʼ RV. [Cf. other words for ʻ ladder ʼ conn. with √śri, √śriṣ2 (√*śliṣ2 ): śrayaṇī -- , niśrayaṇīˊ -- , *śrayantī -- , *śritrā -- , *śrētrī -- ; *śriṣṭrā -- , *śrīḍhi -- , *śrēṣṭrī -- 2 , *śliṣaṇa -- , *ślēṣṭrī -- : see also niḥsaraṇa -- , niyāˊna -- . -- √śri ]Pk. sii -- f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Ash. istrīˊ ʻ ladder made of a single log ʼ (str < ċr as in istrūˊ ~ áśru -- ); Wg. c̣ī, c̣iŕ ʻ ladder ʼ, Kt. c̣īk, Pr. čīk, ċīx (NTS xvii 245 < *ċrita -- = śritá -- ). Addenda: śrití -- [Cf. Ir. *sritā -- (cf. *śritrā -- ), Yid. x̌ad ʻ ladder ʼ, Psht. x̌əl EVSh 101]12704 *śritrā ʻ ladder ʼ. [See śrití -- . -- √śri ]Sh. (Lor.) c̣ic̣ ʻ ladder ʼ, (Grahame Bailey) c̣hĭc̣, c̣hĭc̣h f. (if aspiration is genuine, poss. < *śriṣṭrā -- ?).ŚRIṢ1 ʻ stick to ʼ: *śriṣati, *śriṣṭa -- 1 , *śrēṣita -- , *śrēṣṭrī -- 1 , *śrēṣman -- , *śrēṣmara -- ; -- √śliṣ 1 .ŚRIṢ2 ʻ be in, enter ʼ. [Cf. (hr̥dí) śrēṣāma ʻ we shall cause to enter ʼ RV., hr̥daya -- śríṣ -- ʻ entering the heart ʼ AV. -- s -- enlargement of √śri ]*śriṣṭa -- 2 , *śriṣṭrā -- , *śrīḍhi -- , *śrēṣṭrī -- 2 .12705 *śriṣati ʻ embraces ʼ. [Cf. abhiśríṣ -- f. ʻ binding together ʼ RV. ~ ā -- śliṣati ʻ embraces ʼ R., ślíṣyati. <-> √śriṣ 1 ]Pk. sisaï ʻ embraces ʼ. 12706 *śriṣṭa1 ʻ clinging to ʼ. [~ śliṣṭa -- . -- √śriṣ 1 ]Pk. siṭṭha -- ʻ joined ʼ. 12707 *śriṣṭa2 ʻ entered, resting on ʼ. [For ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in Dard. cf. *śrīḍhi -- and śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. ~ niśrēṇi<-> ʻ ladder ʼ (nisrayaṇīˊ -- , *śrayaṇī -- ). -- See śrití -- . <-> √śriṣ 2 ]Bshk. šiṭh, šiṭ ʻ house ʼ; Phal. šīṭi ʻ inside ʼ; Bi. sīṭhā ʻ cushion of straw or rushes on mouth of well on which bucket rests as water is discharged ʼ. -- With unexpl. š -- for ṣ -- : Kal.rumb. šīṭ ʻ ladder ʼ (urt. šīt < *śrayantī -- ? ). -- Tor. šīr ʻ house ʼ (AO viii 309 < śliṣṭa<-> with -- r -- < -- ṣṭ -- unexpl.) rather <(CDIAL 12703 to 12707)*śrīḍhi ʻ resting -- place, ladder ʼ. [< *śriẓ -- dhi -- ? <-> For ʻ ladder ~ house ʼ see *śriṣṭa -- 2 . -- √śriṣ 2 ]Pk. siḍḍhi -- f. ʻ ladder ʼ, Woṭ. šiṛ f.; Tor. šīr f. ʻ house ʼ (AO viii 109 < śliṣṭa -- without explanation of r, see *śriṣṭa -- 2 ); L. sīṛh f. ʻ rapids in a stream ʼ; P. sīṛhī f. ʻ ladder ʼ (PhonPj 131 < śrēḍhi -- ); B. siṛi, sĩṛi ʻ ladder, staircase, flight of steps ʼ, Or. siṛhi, siṛi; Bi. Aw.lakh. H. sīṛhī f. ʻ ladder ʼ, G. sīḍī f., M. śiḍhī, śiḍī f. -- With unexpl. o/u (cf. śrōṇī -- f. ʻ path ʼ lex. ~ niśrēṇi -- f. ʻ ladder ʼ?): Paš.laur. ṣuṛ, nir. dar. weg. ṣuṛīˊ ʻ ladder ʼ (→ Par. šoṛ ʻ stair, ladder ʼ IIFL iii 3, 172), Phal. šū˘ṛi.Addenda: *śrīḍhi -- : WPah.kṭg. śíṛh f. (obl. -- i ) ʻ ladder ʼ, śíṛhɔ m. ʻ ladder, big staircase ʼ, śíṛhi f. ʻ small do. ʼ. (CDIAL 12709) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M.śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2 ?)(CDIAL 12726)This denotes a mason (artisan) guild -- seni -- of 1. brass-workers; 2. blacksmiths; 3. iron-workers; 4. copper-workers; 5. native metal workers; 6. workers in alloys.The core is a glyphic ‘chain’ or ‘ladder’. Glyph: kaḍī a chain; a hook; a link (G.); kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason; kaḍiyaṇa, kaḍiyeṇa a woman of the bricklayer caste; a wife of a bricklayer (G.) The glyphics are:1. Glyph: ‘one-horned young bull’: kondh ‘heifer’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’.konda 'fire-altar, kiln, furnace'; kunda 'fine gold' singhin 'spiny-horned, thrusting forward horn' rebus: singi 'ornament gold'2. Glyph: ‘bull’: ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’. koD 'horns' rebus: koD 'workshop'3. Glyph: ‘ram’: meḍh ‘ram’. Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’4. Glyph: ‘antelope’: mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’. Vikalpa 1: meluhha ‘mleccha’ ‘copper worker’. Vikalpa 2: meṛh ‘helper of merchant’.5. Glyph: ‘zebu’: khũṭ ‘zebu’. Rebus: khũṭ ‘guild, community’ (Semantic determinant of the ‘jointed animals’ glyphic composition). kūṭa joining, connexion, assembly, crowd, fellowship (DEDR 1882) Pa. gotta ‘clan’; Pk. gotta, gōya id. (CDIAL 4279) Semantics of Pkt. lexeme gōya is concordant with Hebrew ‘goy’ in ha-goy-im (lit. the-nation-s). Pa. gotta -- n. ʻ clan ʼ, Pk. gotta -- , gutta -- , amg. gōya -- n.; Gau. gū ʻ house ʼ (in Kaf. and Dard. several other words for ʻ cowpen ʼ > ʻ house ʼ: gōṣṭhá -- , Pr. gūˊṭu ʻ cow ʼ; S. g̠oṭru m. ʻ parentage ʼ, L. got f. ʻ clan ʼ, P. gotar, got f.; Ku. N. got ʻ family ʼ; A. got -- nāti ʻ relatives ʼ; B. got ʻ clan ʼ; Or. gota ʻ family, relative ʼ; Bhoj. H. got m. ʻ family, clan ʼ, G. got n.; M. got ʻ clan, relatives ʼ; -- Si. gota ʻ clan, family ʼ ← Pa. (CDIAL 4279). Alternative: adar ḍangra ‘zebu or humped bull’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.); ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)6. The sixth animal can only be guessed. Perhaps, a tiger (A reasonable inference, because the glyph ’tiger’ appears in a procession on some Indus script inscriptions. Glyph: ‘tiger?’: kol ‘tiger’.Rebus: kol ’worker in iron’. Vikalpa (alternative): perhaps, rhinoceros. gaṇḍa ‘rhinoceros’; rebus:khaṇḍ ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’. Thus, the entire glyphic composition of six animals on the Mohenjodaro seal m417 is semantically a representation of a śrḗṇi, ’guild’, a khũṭ , ‘community’ of smiths and masons. bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' Also, baTa 'six' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'.- Annex B Decipherment of 'squirrel' hieroglyph

Guild-master’s Indus Script Inscription (m304) deciphered. Hypertext khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ 'squirrel’ is plaintext khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) https://tinyurl.com/y9ug5h9y

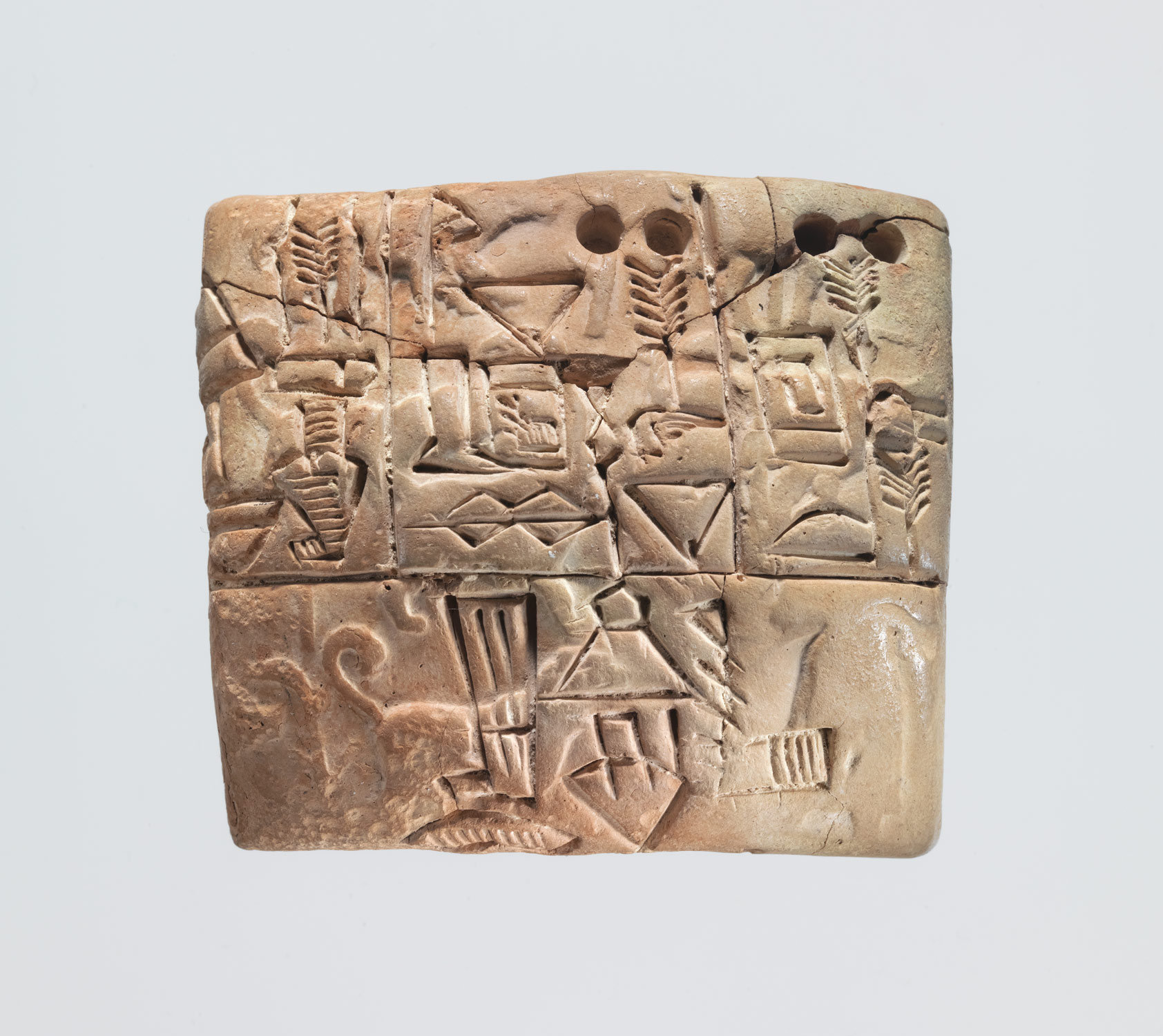

Longest inscription m0314 of Indus Script Corpora is catalogue of a guild-master. The guild master is signified by Indus Script hypertext 'squirrel' hieroglyph 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Rebus: plaintext: khār 'blacksmith' śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa).palm squirrel,Sciurus palmarum'This is perhaps the longest inscriptionof Indus Script Corpora.m0314 The indus script inscription is a detailed account of the metal work engaged in by the Indus artisans. It is a professional calling card of the metalsmiths' guild of Mohenjodaro used to affix a sealing on packages of metal artefacts traded by Meluhha (mleccha)speakers.![]() The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is ![]() Squirrel as shown on Seal impression

Squirrel as shown on Seal impression![]() Flipped vertically is likey to signify 'squirrel' as on Nindowari-damb seal 01All hieroglyphs are read from r. to l. Line 1:

Flipped vertically is likey to signify 'squirrel' as on Nindowari-damb seal 01All hieroglyphs are read from r. to l. Line 1: ![]() eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop. Fish + lid: aya dhakka,Rebus: aya dhakka 'bright iron/alloy metal'.Fish + fin: aya khambhaṛā rebus: aya kammaṭa 'alloy metal mint, coiner, coinage'

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop. Fish + lid: aya dhakka,Rebus: aya dhakka 'bright iron/alloy metal'.Fish + fin: aya khambhaṛā rebus: aya kammaṭa 'alloy metal mint, coiner, coinage'

Fish + sloping stroke, aya dhāḷ ‘metal ingot’ (Vikalpa: ḍhāḷ = a slope; the inclination of a plane (G.) Rebus: : ḍhāḷako = a large metal ingot (G.)khaṇḍa 'arrow' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements' Thus, line 1 reads: bright iron/alloy metal, alloy metal mint, large metal ingot (ox-hide)

Line 2:मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) The circumscript is composed of four 'splinters': gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements', kanda 'fire-altar' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: iron implements workshop.S. baṭhu m. ‘large pot in which grain is parched, Rebus; bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’ (P.) baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) Vikalpa: meṛgo = rimless vessels (Santali) bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (G.) baṭa = kiln (Santali); baṭa = a kind of iron (G.) bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron (Pkt.) baṭhu large cooking fire’ baṭhī f. ‘distilling furnace’; L. bhaṭṭh m. ‘grain—parcher's oven’, bhaṭṭhī f. ‘kiln, distillery’, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭh m., ṭhī f. ‘furnace’, bhaṭṭhā m. ‘kiln’; S. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ‘distil (spirits)’. (CDIAL 9656) Rebus: meḍ iron (Ho.) PLUS muka 'ladle' rebus; mū̃h 'ingot', quantity of metal got out of a smelter furnace (Santali).Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex (hypertext) signifies: iron ingot.kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy/forge.kanka, karṇaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo', 'engraver, scribe, account'Thus line 2 signifies metal products -- iron ingots, metalcastings (of smithy/forge iron metals workshop) handed over to Supercargo, (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale). Line 3:

kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Telugu)A. goṭ ‘a fruit, whole piece’, °ṭā ‘globular, solid’, guṭi ‘small ball, seed, kernel’; B. goṭā ‘seed, bean, whole’; Or. goṭā ‘whole, undivided’, goṭi ‘small ball, cocoon’, goṭāli ‘small round piece of chalk’; Bi. goṭā ‘seed’; Mth. goṭa ‘numerative particle’ (CDIAL 4271) Rebus: koṭe ‘forging (metal)(Mu.) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.) PLUS infix of sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: forged silver workshop.

Hieroglyph is a loop of threads formed on a loom or loose fringes of a garment. This may be seen from the seal M-9 which contains the sign:

धातु [p= 513,3] m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3. constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf.त्रिविष्टि- , सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &c (Monier-Williams) dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.).; S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)Rebus: M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; (CDIAL 6773) धातु primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral, ore (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of words i.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relics L. [cf. -गर्भ]) (Monier-Williams. Samskritam)Thus, this hieroglyph signifies three types of ferrite ore: magnetite, hematite and laterite (poLa, bicha, goTa). Vikalpa: Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Rebus: goṭī f. ʻlump of silver' (G.)Hieroglyph: Archer with bow and arrow on one hand: kamāṭhiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; kāmaḍ, kāmaḍum = a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.lex.) Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.)kolom 'rice plant' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge'.kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bronze' Vikalpa: (A.) kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner's lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295).Hieroglyph: squirrel: *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master khāra, 'squirrel', rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri). *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ] Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? (CDIAL 12723) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ] Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ,seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2 ?) (CDIAL 12726) I suggest that the šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? is read rebus: śeṭhī, śeṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ (Marathi) or eṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ(Prakrtam)Thus, line 3 signifies: bronze guild master of smithy/forge, mint for three types of ferrite mineral (magnetite, hematite, laterite)The three lines together, the engtire inscription of m0314 is a metalwork cagtalogue of a guild-master of workshops working in: (1) native unsmelted metal, metal mint, large metal ingot (oxhide)(2) metal products -- iron ingots, metalcastings (of smithy/forge iron metals workshop) handed over to Supercargo, (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale)(3)smithy/forge, mint for three types of ferrite mineral (magnetite, hematite, laterite)

![]() Source: Collections in Pakistan http://ignca.gov.in/Asi_data/81453.pdfLong Indus Script inscription compares with Nindowari0-damb seal 01 which also shows 'squirrel'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

Source: Collections in Pakistan http://ignca.gov.in/Asi_data/81453.pdfLong Indus Script inscription compares with Nindowari0-damb seal 01 which also shows 'squirrel'šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrelʼ,'guild master'.

kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bronze'

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) The circumscript is composed of four 'splinters': gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements', kanda 'fire-altar' खााडा [ kāṇḍā ] 'A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon)' Rebus: kaNDa 'implements' (Santali).kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy/forge.kanka, karNaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo', 'engraver, scribe, account'Hieroglyph: 8 short strokes: gaNDa 'four' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, this hieroglyph-multiplex or hypertext signifies: iron implements workshop.Hieroglyph: squirrel: *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master khāra, 'squirrel', rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri). *śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ] Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? (CDIAL 12723) Rebus: śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ] Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ,seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2 ?) (CDIAL 12726) I suggest that the šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ? is read rebus: śeṭhī, śeṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ (Marathi) or eṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ(Prakrtam) Hypertext of Indus Script: šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ 'flying squirrel' rebus: śrēṣṭhin 'foreman of a guild'. ![]()

![Image result for palm squirrel]() Indian palm squirrel, Funambulus Palmarum There are also other seals with signify the 'squirrel' hieroglyph.

Indian palm squirrel, Funambulus Palmarum There are also other seals with signify the 'squirrel' hieroglyph. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Nindowari-damb seal Nd0-1; Mohenjo-daro seal m-1202; Harappa tablet h-771; Harappa tablet h-419

Nindowari-damb seal Nd0-1; Mohenjo-daro seal m-1202; Harappa tablet h-771; Harappa tablet h-419

![]() m1634 ceramic stoneware bangle (badge)

m1634 ceramic stoneware bangle (badge)![]() Read from r. to l.:

Read from r. to l.: Vikalpa: The prefix![]() Sign 403: Hieroglyph: bārī , 'small ear-ring': H. bālā m. ʻbraceletʼ (→ S. ḇālo m. ʻbracelet worn by Hindusʼ), bālī, bārī f. ʻsmall ear -- ringʼ, OMārw. bālī f.; G. vāḷɔ m. ʻ wire ʼ, pl. ʻ ear ornament made of gold wire ʼ; M. vāḷā m. ʻ ring ʼ, vāḷī f. ʻ nose -- ring ʼ.(CDIAL 11573) Rebus: bārī 'merchant' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'. If the duplication of the 'bangle' on Sign 403 signifies a plural, the reading could be: karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār 'blacksmith, iron worker'.

Sign 403: Hieroglyph: bārī , 'small ear-ring': H. bālā m. ʻbraceletʼ (→ S. ḇālo m. ʻbracelet worn by Hindusʼ), bālī, bārī f. ʻsmall ear -- ringʼ, OMārw. bālī f.; G. vāḷɔ m. ʻ wire ʼ, pl. ʻ ear ornament made of gold wire ʼ; M. vāḷā m. ʻ ring ʼ, vāḷī f. ʻ nose -- ring ʼ.(CDIAL 11573) Rebus: bārī 'merchant' vāḍhī, bari, barea 'merchant' bārakaśa 'seafaring vessel'. If the duplication of the 'bangle' on Sign 403 signifies a plural, the reading could be: karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles Rebus: khār 'blacksmith, iron worker'.

![]() Sign 403 is a duplication of

Sign 403 is a duplication of ![]() bun-ingot shape. This shape is signified on a zebu terracotta pratimā found at Harappa and is consistent with mūhā mẽṛhẽt process of making unique bun-shaped ingots (See Santali expression and meaning described below):

bun-ingot shape. This shape is signified on a zebu terracotta pratimā found at Harappa and is consistent with mūhā mẽṛhẽt process of making unique bun-shaped ingots (See Santali expression and meaning described below):

1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt uṟukku 'cast iron ingot,steel' or 2. khār uṟukku 'blacksmith, steel'.

If he squirrel is read as šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻflying squirrel' rebus: śrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa), the reading of the hypertext ![]() is:

is:

1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt śrēṣṭhin 'cast iron ingot, guild-master' or 2. khār śrēṣṭhin 'blacksmith, guild-master'.

![]() Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots from Harappa.पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' Rebus: magnetite, citizen.(See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/zebu-archaeometallurgy-legacy-of-india.html )

Slide 33. Early Harappan zebu figurine with incised spots from Harappa.पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu' Rebus: magnetite, citizen.(See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/zebu-archaeometallurgy-legacy-of-india.html )

mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali) खोट (p. 212) [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. (Marathi)

An alternative reading for 'squirrel' hieroglyph is also suggested:

The sequence of hieroglyphs![]() Squirrel + Sign 403 signifies two professional responsibilities/functions

Squirrel + Sign 403 signifies two professional responsibilities/functions 1. khār 'blacksmith'; 2. seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi).

Alternatively, 1. dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt 'cast iron ingot'; 2. khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) or seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi) or śrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa).

Thus, two readings are possible for the 'squirrel' hieroglyph: khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) and/or seṭhi ʻwholesale merchant' (Sindhi) orśrēṣṭhin 'guild master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa)

Hieroglyph: squirrel (phonetic determinant): खार [ khāra ] A squirrel, Sciurus palmarum. खारी [ khārī ] f (Usually खार ) A squirrel. (Marathi)

A homonymous hieroglyph or allograph: arms with bangles: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, banglesʼ.(Gujarati)(CDIAL 2779) Rebus: khār खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b,l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta 'bellows of blacksmith'.with inscription.

*śrēṣṭrī1 ʻ clinger ʼ. [√śriṣ 1 ]Phal. šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄ ʻ flying squirrel ʼ?(CDIAL 12723) Rebus: guild master:*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ 2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ 2 ]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) Rebus: śrḗṣṭha ʻ most splendid, best ʼ RV. [śrīˊ -- ]Pa. seṭṭha -- ʻ best ʼ, Aś.shah. man. sreṭha -- , gir. sesṭa -- , kāl. seṭha -- , Dhp. śeṭha -- , Pk. seṭṭha -- , siṭṭha -- ; N. seṭh ʻ great, noble, superior ʼ; Or. seṭha ʻ chief, principal ʼ; Si. seṭa, °ṭu ʻ noble, excellent ʼ. śrēṣṭhin m. ʻ distinguished man ʼ AitBr., ʻ foreman of a guild ʼ, °nī -- f. ʻ his wife ʼ Hariv. [śrḗṣṭha -- ]Pa. seṭṭhin -- m. ʻ guild -- master ʼ, Dhp. śeṭhi, Pk. seṭṭhi -- , siṭṭhi -- m., °iṇī -- f.; S. seṭhi m. ʻ wholesale merchant ʼ; P. seṭh m. ʻ head of a guild, banker ʼ, seṭhaṇ, °ṇī f.; Ku.gng. śēṭh ʻ rich man ʼ; N. seṭh ʻ banker ʼ; B. seṭh ʻ head of a guild, merchant ʼ; Or. seṭhi ʻ caste of washermen ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. sēṭhi ʻ merchant, banker ʼ, H. seṭh m., °ṭhan f.; G. śeṭh, śeṭhiyɔ m. ʻ wholesale merchant, employer, master ʼ; M. śeṭh, °ṭhī, śeṭ, °ṭī m. ʻ respectful term for banker or merchant ʼ; Si. siṭu, hi° ʻ banker, nobleman ʼ H. Smith JA 1950, 208 (or < śiṣṭá -- 2 ?)(CDIAL 12725, 12726)

![]()

![]() Nindowari seal Nd-1

Nindowari seal Nd-1From l. to r.:Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa)Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; dhAL 'slanted stroke'Rebus: dhALako 'large ingot' khANDa 'notch' Rebus: khANDa 'metal implements'; kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; dula 'two, pair'Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements'karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani); koDa 'one'Rebus: koD 'workshop'; aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'; kanac 'corner'Rebus: kancu 'bronze'. konda 'young bull' Rebus: kondar 'turner' koD 'horn'Rebus: koD 'workshop' sangaDa 'lathe, portable furnace'Rebus: sangar 'fortification' sanghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)Mohenjo-daro seal m1202m1202 1325From r. to l.:barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'goldsmith guild'muhA 'ingot'; dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot');Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy';

kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; aduru 'harrow' Rebus: aduru 'native unsmelted metal';bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'; kanda kanka 'rim of pot' Rebus: khaNDa 'implements' karNI 'supercargo, scribe'; muhA 'ingot, quantity of iron ore smelted out of the smelter'.dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' muhA 'ingot' (Together, dul muhA 'cast iron ingot'); Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; dula 'two' Rebus: dul 'cast metal or casting'. Thus, the epigraph with three hieroglyph-multiplexes read rebus: metal castings, cast metal ingot, guild-master (pewter-zinc alloy.)![]() h419

h419Squirrel 'khāra, šē̃ṣṭrĭ̄' Indus Script hypertext is khār 'blacksmith'śrēṣṭhin 'guild-master' (Aitareya Brāhmaṇa) Vikalpa: tuttha 'squirrel' Rebus: tuttha 'pewter, zinc alloy'; maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani). Thus, guild-master's warehouse.

m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm)

m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm)  The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is  eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop. Fish + lid:

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop. Fish + lid:

Source: Collections in Pakistan

Source: Collections in Pakistan

h419

h419

L

L

Karen

Karen

aspirate ‘tha’ sound, signifies ‘tha’ phoneme in

aspirate ‘tha’ sound, signifies ‘tha’ phoneme in

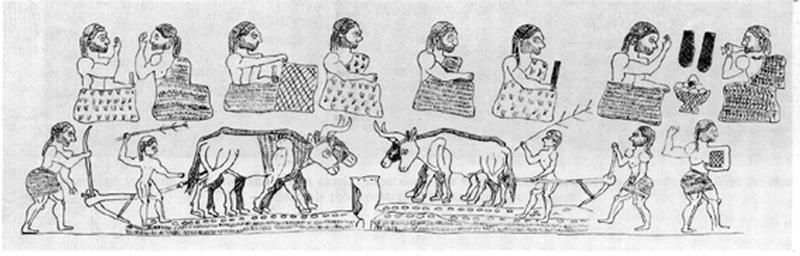

Cylindrical Cup with Agricultural and Ceremonial Scene

Cylindrical Cup with Agricultural and Ceremonial Scene

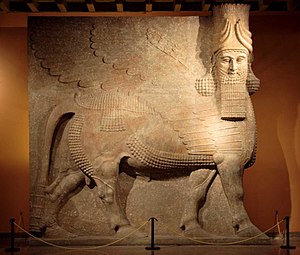

Lamassu

Lamassu

Bull-man in Citragupta temple, Khajuraho

Bull-man in Citragupta temple, Khajuraho

m-1199

m-1199