Itihāsa. Early Islamic manufacture of crucible steel at Merv, Turkmenistan -- Dafydd Griffiths, Ann Feuerbach (1999)

Itihāsa. Kumbakonam: the ritual topography of a sacred and royal city of South India -- Vivek Nanda (1999)

Itihāsa. Indus Script metalwork hypertexts of trading civilization of Failaka, Saar & Barbar Temple, Bahrain.Dilmun revisited: excavations at Saar, Bahrain -- Harriet Crawford (1997) Excavations at Barbar Temple -- Hojlund, Flemming et al (2005)

https://tinyurl.com/ycozar7v

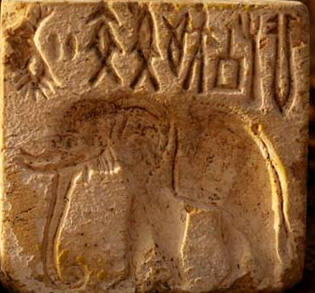

This monograph posits the presence of Meluhha artisans and seafaring merchants in Dilmun and failaka. This presence explains the decipherment of Dilmun seals, Barbar temple bronze bull's head and Failaka seals as Indus Script inscriptions constituting wealth-accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues. Dilmun and Failaka seals are archives recording trade transactions with Meluhha (Sarasvati Civilization).

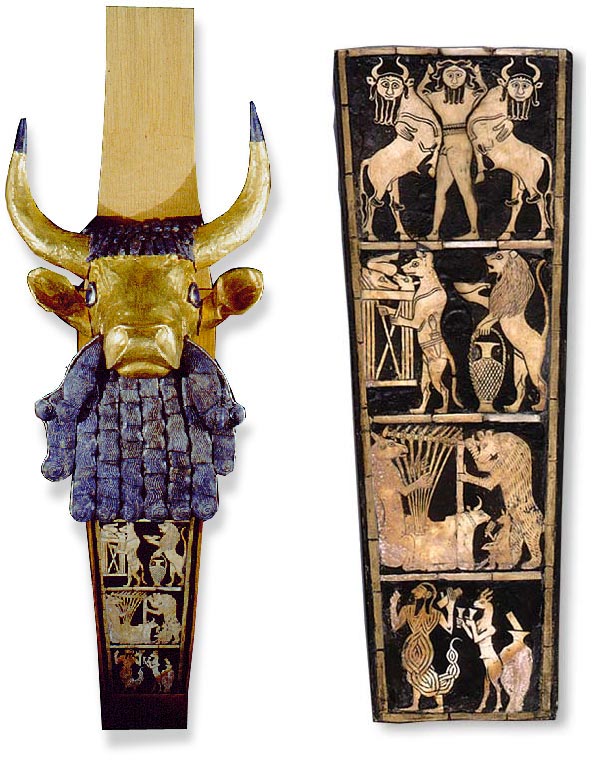

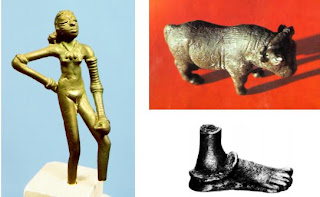

Dilmun finds mention in cuneiform texts as a trade partner and as a trading post of the Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization trade route. The bronze bull's head found in Barbar Temple of Bahrein is paralleled by the artifacts of Early Dynastic Sumer as posited by Elisabeth CL During Caspers and also by the Indus Script rebus representation of ḍhangra ‘bull’ Rebus: ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (Pkt.); Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith.ʼ Thus, the deity venerated as the bull's head is a veneration of the ancestor blacksmith who has attained divinity; hence, ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund, 'speech union'). Three temples were discovered in Barbar village, Bahrein, and the oldest is dated to 3000 BCE.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbar_Temple

Map with known natural distribution of softstone (adapted from David-Cuny, H, 2012, Introduction in: H. David-Cuny and I. Azpeitia (eds.) Failaka Seals catalogue Vol. 1, Al-Khidr, 13-27, Kuwaiti City, National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, p. 19)

![]() Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115). (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'. dhāḷ'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'large ingot'. ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'. kudi 'jump' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'

Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115). (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'. dhāḷ'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'large ingot'. ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'. kudi 'jump' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'

This monograph posits the presence of Meluhha artisans and seafaring merchants in Dilmun and failaka. This presence explains the decipherment of Dilmun seals, Barbar temple bronze bull's head and Failaka seals as Indus Script inscriptions constituting wealth-accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues. Dilmun and Failaka seals are archives recording trade transactions with Meluhha (Sarasvati Civilization).

Dilmun finds mention in cuneiform texts as a trade partner and as a trading post of the Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization trade route. The bronze bull's head found in Barbar Temple of Bahrein is paralleled by the artifacts of Early Dynastic Sumer as posited by Elisabeth CL During Caspers and also by the Indus Script rebus representation of ḍhangra ‘bull’ Rebus: ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (Pkt.); Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith.ʼ Thus, the deity venerated as the bull's head is a veneration of the ancestor blacksmith who has attained divinity; hence, ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund, 'speech union'). Three temples were discovered in Barbar village, Bahrein, and the oldest is dated to 3000 BCE.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbar_Temple

Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115). (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'. dhāḷ'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'large ingot'. ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'. kudi 'jump' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'

Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115). (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'. dhāḷ'slanted stroke' rebus: dhāḷako 'large ingot'. ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'. kudi 'jump' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' The Bull's Head from Barbar Temple II, Baḥrain A Contact with Early Dynastic Sumer

Elisabeth C. L. During CaspersEast and WestVol. 21, No. 3/4 (September-December 1971), pp. 217-223Published by: Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO)https://www.jstor.org/stable/29755698![]()

Add caption

See:Eric Olijdam and Helene David-Cuny, 2018, Dilmun-Meluhhan Relations Revisited in Light of Observations on Early Dilmun Seal Production during the City IIa-c Period (c. 2050-1800 BCE)In book: Walking with the Unicorn. Social Organization an Material Culture in Ancient South Asia. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer Felicitation Volume, Publisher: ISMEO / Archaeopress, pp. 406-432https://www.academia.edu/36750743/Dilmun-Meluhhan_Relations_Revisited_in_Light_of_Observations_on_Early_Dilmun_Seal_Production_during_the_City_IIa-c_Period_c._2050-1800_BC_ Abstract. This contribution brings together information on several aspects of early seal ownership and seal production during theCity IIa-c period. It shows that seals were common objects and that ownership was not restricted to specific professionsor socio-economic segments of society. Seals were made in small workshops, alongside other items of jewellery andpersonal ornaments. They were carved from exotic raw materials that had to be imported. Softstone was the mostcommon and there is mounting evidence that suggests a specific type of steatite was preferred by the ancient seal-cutters. Surface treatments were applied in order to achieve the desired effect of a shiny white seal. This dictated the preference for dolomitic steatite and limited the scope of possible alternative materials. It is suggested that the pyrotechniques that were employed and the choices that were made by the ancient seal-cutters form a technological style highly reminiscent of that of the Indus Civilization, including some of the important ideological associations. Thisapproach and its tentative outcomes bolster the commonly accepted theory of a westward transmission of Harappan sealing technology, which has so far been based primarily on iconographic analysis.

Dilmun seal morphology

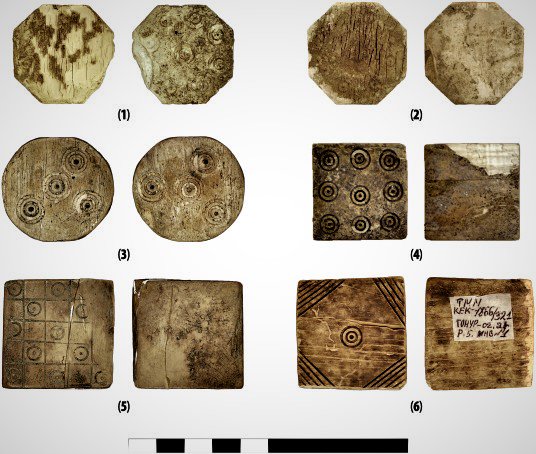

Figure 4. Eleven seals from the workshop area in Excavation 520 at Qal’at al-Bahrain (Kjærum 1994: figs.1726, 1729, 1731– 2, 1734 – 5, 1737, 1739, 1741 – 43)

![]() Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.A Stamp seal and its impression from the Harappan site of Lothal north of Bombay, of the type also found in the contemporary cultures of southern Iraq and the Persian Gulf Area. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/archaeology-in-india/

Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.A Stamp seal and its impression from the Harappan site of Lothal north of Bombay, of the type also found in the contemporary cultures of southern Iraq and the Persian Gulf Area. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/archaeology-in-india/-

- http://www.bible-history.com/sketches/assyria/assyrian_stone_altar.html “Amongst the ruins of Khorsaba were discovered two circular altars, which are so much like the Greek tripod…The altar is supposed by three lion’s paws. Round the upperpart is an inscription, in cuneiform characters, containing the name of the Korsabad king.”

- (Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1849, Nineveh and its remains: with an account of a visit to the Chaldaean christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or devil worshippers, and an enquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient Assyrians, Volume 2, J. Murray,

- The feline paws at the bottom of the altar should be noted. In Meluhha (mleccha), Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115)

Feline paws shown on the Khorsabad altar are also seen on the hieroglyphs of the Elamite spinner:Bas relief fragment, called the 'spinner'. Louvre.

Technical descriptionBitumenJ. de Morgan excavationsSb 2834Near Eastern AntiquitiesSully wingGround floorIran in the Iron Age (14th––mid-6th century BC) and during the Neo-Elamite dynastiesRoom 11Display case 6 b: Susiana in the Neo-Elamite period (8th century–middle 6th century BC). Goldwork, sculpture, and glyptics. - Decoding of hieroglyphs on spinner bas-relief:

panja 'feline paws' rebus; panja 'kiln, smelter' kātī ‘spinner’ (G.) Rebus: khati 'wheelwright' (H.) kāṭi = fireplace in the form of a long ditch (Ta.Skt.Vedic) kāṭya = being in a hole (VS. XVI.37); kāṭ a hole, depth (RV. i. 106.6) khāḍ a ditch, a trench; khāḍ o khaiyo several pits and ditches (G.) khaṇḍrun: ‘pit (furnace)’ (Santali) - Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) Grapheme as a phonetic determinant of the depiction of woman, kola; rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.)kola ‘woman’ (Nahali); Rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.); rebus: aya ‘metal’ (G.)bhaṭa ‘six’ (G.); rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (Santali) viciṟi fan; bīsāle fan (as the one made of areca spathe). Koḍ. bi·j- (bi·ji-), (Mercara dialect) bi·d- (bi·di-) to wave (tr.); (wind) blows, (tree, cloth) waves; grind with grinding stones. Cf. Skt. vīj-, vyaj- to fan; vījana-, vyajana- fanning, a fan; Turner, CDIAL, no. 12043 (DEDR 5450) Rebus: bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'. kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'.

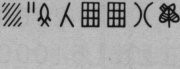

Dotted circle is Indus Script hypertext

|

| Add caption |

- http://www.bible-history.com/sketches/assyria/assyrian_stone_altar.html “Amongst the ruins of Khorsaba were discovered two circular altars, which are so much like the Greek tripod…The altar is supposed by three lion’s paws. Round the upperpart is an inscription, in cuneiform characters, containing the name of the Korsabad king.”

- (Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1849, Nineveh and its remains: with an account of a visit to the Chaldaean christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or devil worshippers, and an enquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient Assyrians, Volume 2, J. Murray,

- The feline paws at the bottom of the altar should be noted. In Meluhha (mleccha), Stamp seal no. 693. Disc profile concave, grey steatite, while-glazed. On the reverse three lines and four circles. Dia. 25 mm. A leaping lion (?) with claws, wide-open toothed jaws and sigmoid tail, followed by an antelope. Above the scene a snake with wide-open toothless jaws. The scales of the snake are indicated with close incisions from both sides. Between the lion and the gazelle a palm front. Below the lion an angular figure -- probably a crescent. (Hojlund, Flemming et al, 2005, p.115)Feline paws shown on the Khorsabad altar are also seen on the hieroglyphs of the Elamite spinner:Bas relief fragment, called the 'spinner'. Louvre.Technical descriptionBitumenJ. de Morgan excavationsSb 2834Near Eastern AntiquitiesSully wingGround floorIran in the Iron Age (14th––mid-6th century BC) and during the Neo-Elamite dynastiesRoom 11Display case 6 b: Susiana in the Neo-Elamite period (8th century–middle 6th century BC). Goldwork, sculpture, and glyptics.

- Decoding of hieroglyphs on spinner bas-relief:panja 'feline paws' rebus; panja 'kiln, smelter' kātī ‘spinner’ (G.) Rebus: khati 'wheelwright' (H.) kāṭi = fireplace in the form of a long ditch (Ta.Skt.Vedic) kāṭya = being in a hole (VS. XVI.37); kāṭ a hole, depth (RV. i. 106.6) khāḍ a ditch, a trench; khāḍ o khaiyo several pits and ditches (G.) khaṇḍrun: ‘pit (furnace)’ (Santali)

- Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) Grapheme as a phonetic determinant of the depiction of woman, kola; rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.)kola ‘woman’ (Nahali); Rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.)ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.); rebus: aya ‘metal’ (G.)bhaṭa ‘six’ (G.); rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’ (Santali) viciṟi fan; bīsāle fan (as the one made of areca spathe). Koḍ. bi·j- (bi·ji-), (Mercara dialect) bi·d- (bi·di-) to wave (tr.); (wind) blows, (tree, cloth) waves; grind with grinding stones. Cf. Skt. vīj-, vyaj- to fan; vījana-, vyajana- fanning, a fan; Turner, CDIAL, no. 12043 (DEDR 5450) Rebus: bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'. kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' PLUS panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'furnace, kiln'.

धाव (p. 250) dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it. धवड (p. 249) dhavaḍa m (Or धावड) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.

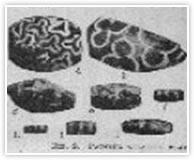

A bow compass to draw smallest possible circles. Hope archaeologists discover this in Sarasvati civilization sites. The dotted circle signifies Sindhi. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres' Hindi. dhāv 'throw of dice' rebus: dhāū, dhāv 'mineral'.

वृत्त [p= 1009,2] mfn. turned , set in motion (as a wheel) RV.; a circle; vr̥ttá ʻ turned ʼ RV., ʻ rounded ʼ ŚBr. 2. ʻ completed ʼ MaitrUp., ʻ passed, elapsed (of time) ʼ KauṣUp. 3. n. ʻ conduct, matter ʼ ŚBr., ʻ livelihood ʼ Hariv. [√vr̥t 1 ] 1. Pa. vaṭṭa -- ʻ round ʼ, n. ʻ circle ʼ; Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- ʻ round ʼ; L. (Ju.) vaṭ m. ʻ anything twisted ʼ; Si. vaṭa ʻ round ʼ, vaṭa -- ya ʻ circle, girth (esp. of trees) ʼ; Md. va'ʻ round ʼ GS 58; -- Paš.ar. waṭṭəwīˊk, waḍḍawik ʻ kidney ʼ ( -- wĭ̄k vr̥kká -- ) IIFL iii 3, 192?(CDIAL 12069) வட்டம்போர் vaṭṭam-pōr, n. < வட்டு +. Dice-play; சூதுபோர். (தொல். எழுத். 418, இளம்பூ.)வட்டச்சொச்சவியாபாரம் vaṭṭa-c-cocca-viyāpāram, n. < id. + சொச்சம் +. Money-changer's trade; நாணயமாற்று முதலிய தொழில். Pond. வட்டமணியம் vaṭṭa-maṇiyam, n. < வட் டம் +. The office of revenue collection in a division; வட்டத்து ஊர்களில் வரிவசூலிக்கும் வேலை. (R. T .) వట్ట (p. 1123) vaṭṭa vaṭṭa. [Tel.] n. The bar that turns the centre post of a sugar mill. చెరుకుగానుగ రోటినడిమిరోకలికివేయు అడ్డమాను. వట్టకాయలు or వట్టలు vaṭṭa-kāyalu. n. plu. The testicles. వృషణములు, బీజములు. వట్టలుకొట్టు to castrate. lit: to strike the (bullock's) stones, (which are crushed with a mallet, not cut out.) వట్ర (p. 1123) vaṭra or వట్రన vaṭra. [from Skt. వర్తులము.] n. Roundness. నర్తులము, గుండ్రన. వట్ర. వట్రని or వట్రముగానుండే adj. Round. గుండ్రని.

Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() m0352 cdef

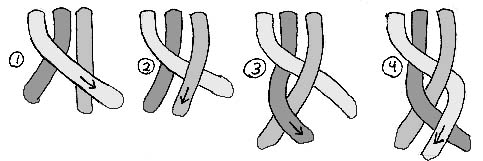

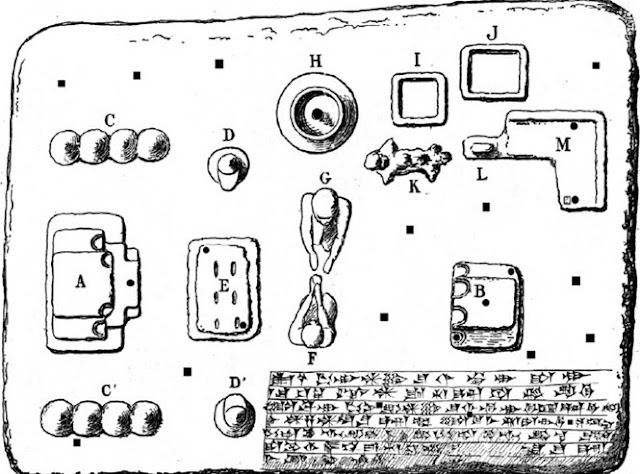

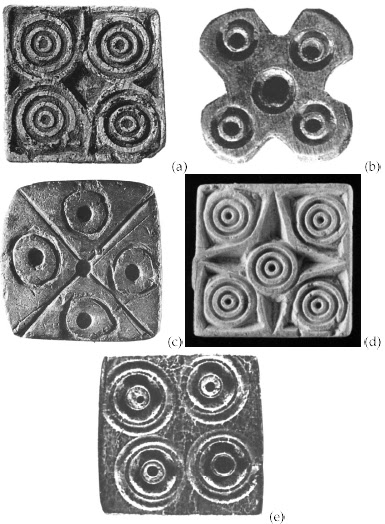

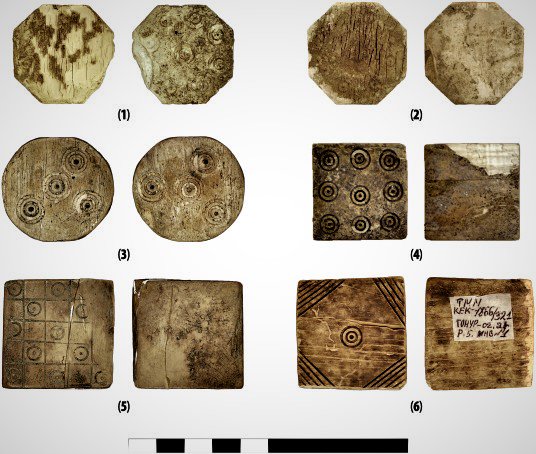

m0352 cdef![]() The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features.

The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features.

Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:

dhātu 'layer, strand'; dhāv 'strand, string' Rebus: dhāu, dhātu 'ore'

1. Round dot like a blob -- . Glyph: raised large-sized dot -- (gōṭī ‘round pebble);goTa 'laterite (ferrite ore)2. Dotted circle khaṇḍa ‘A piece, bit, fragment, portion’; kandi ‘bead’;3. A + shaped structure where the glyphs 1 and 2 are infixed. The + shaped structure is kaṇḍ ‘a fire-altar’ (which is associated with glyphs 1 and 2)..Rebus readings are: 1. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼgoTa 'laterite (ferrite ore); 2. khaṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’; 3. kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

Four ‘round spot’; glyphs around the ‘dotted circle’ in the center of the composition: gōṭī ‘round pebble; Rebus 1: goTa 'laterite (ferrite ore); Rebus 2:L. khoṭf ʻalloy, impurityʼ, °ṭā ʻalloyedʼ, awāṇ. khoṭā ʻforgedʼ; P. khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ M.khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (CDIAL 3931) Rebus 3: kōṭhī ] f (कोष्ट S) A granary, garner, storehouse, warehouse, treasury, factory, bank. khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ metal is produced from kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’ yielding khaṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’. This word khaṇḍā is denoted by the dotted circles.![ahar12]() Stepped cross seals with Indus Script hieroglyphs

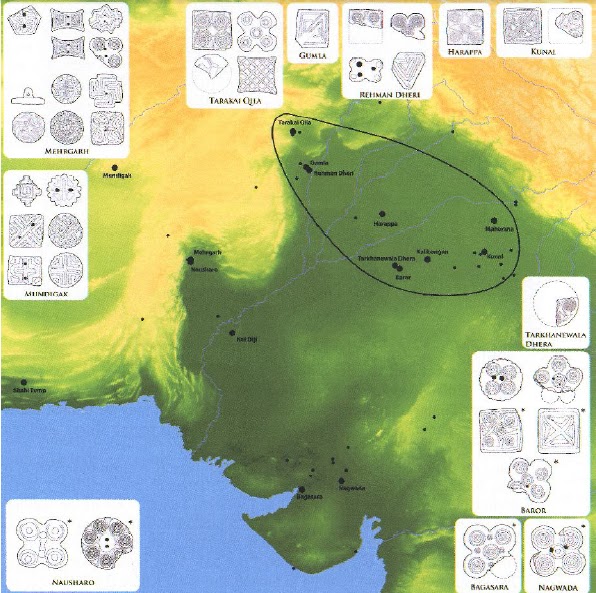

Stepped cross seals with Indus Script hieroglyphs

![ahar33]() Hieroglyph: eruvai ‘kite’ Rebus: eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.) eruvai = copper (Ta.); ere – a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.) The central dot in the cross (which signifies a fire-altar) is: goTa ’round’ Rebus: khoT ‘ingot’. gaNDA ‘four’ rebus: kanda.’fire-altar’.khamba ‘wing’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint’. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'.

Hieroglyph: eruvai ‘kite’ Rebus: eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tu.lex.) Rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.) eruvai = copper (Ta.); ere – a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.) The central dot in the cross (which signifies a fire-altar) is: goTa ’round’ Rebus: khoT ‘ingot’. gaNDA ‘four’ rebus: kanda.’fire-altar’.khamba ‘wing’ rebus: kammaTa ‘mint’. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā id. rebus: phaḍā, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory'.

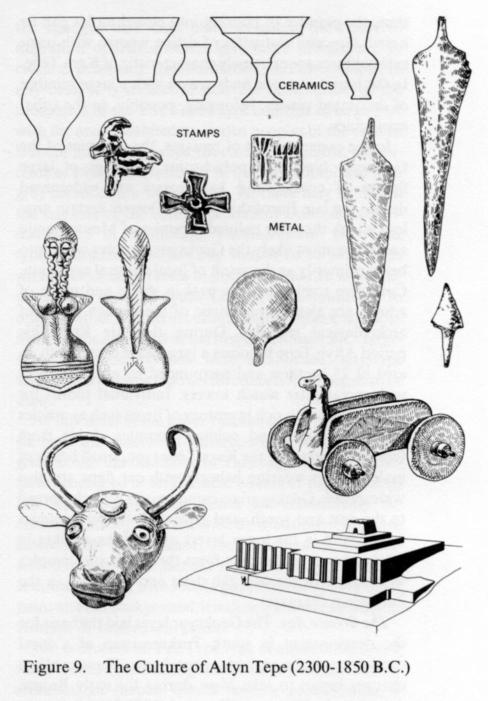

![]() Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

![]()

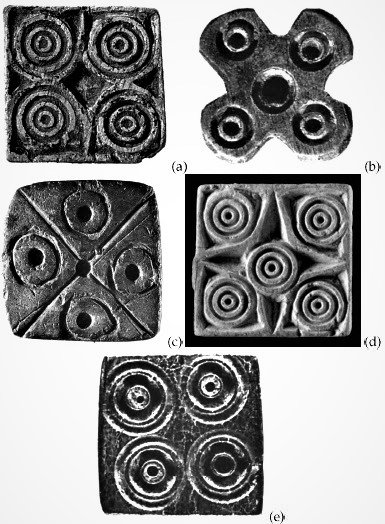

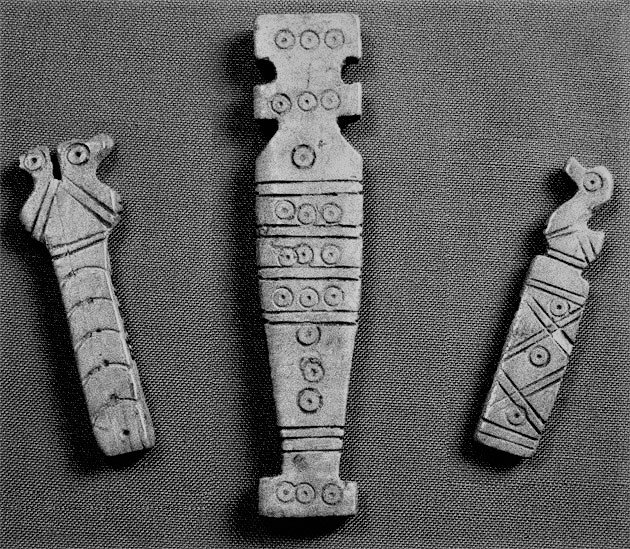

Ivory combs. Turkmenistan.

![]()

![]()

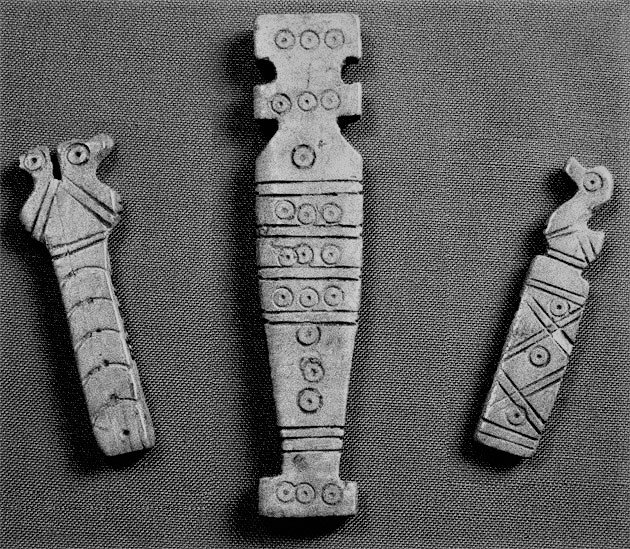

Ivory objects. Sarasvati Civilization

![]()

![]()

Tablets.Ivory objects. Mohenjo-daro.

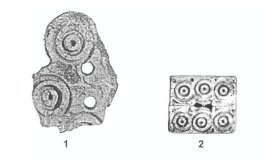

Ivory rod, ivory plaques with dotted circles. Mohenjo-daro (Musee National De Arts Asiatiques, Guimet, 1988-1989, , Les cites oubliees de l’Indus Archeologie du Pakistan.] dhātu '

![]()

Button seal. Baror, Rajasthan.![]()

Button tablet. Harappa. Dotted circles.

![File:Musée GR de Saint-Romain-en-Gal 27 07 2011 13 Des et jetons.jpg]() Dices and chips in bone, Roman time. Gallo-Roman Museum of Saint-Romain-en-Gal-Vienne.

Dices and chips in bone, Roman time. Gallo-Roman Museum of Saint-Romain-en-Gal-Vienne.

Indus Script hypertext/hieroglyph: Dotted circle: दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

தாயம் tāyam :Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻrelic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) धाव (p. 250) dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it. धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. In these parts they are Muhammadans. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron. (Marathi).

PLUS

Hieroglyph: vaṭṭa 'circle'.

Thus, together, the hypertext reads rebus dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'

The dotted circle hypertexts link with 1. iron workers called धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa and 2. miners of Mosonszentjános, Hungary; 3. Gonur Tepe metalworkers, metal traders and 4. the tradition of अक्ष-- पटल [p= 3,2] n. court of law; depository of legal document Ra1jat. Thus, अक्ष on Indus Script Corpora signify documents, wealth accounting ledgers of metal work with three red ores. Akkha2 [Vedic akṣa, prob. to akṣi & Lat. oculus, "that which has eyes" i. e. a die; cp. also Lat. ālea game at dice (fr.* asclea?)] a die D i. 6 (but expld at DA i. 86 as ball -- game: guḷakīḷa); S i. 149 = A v. 171 = Sn 659 (appamatto ayaŋ kali yo akkhesu dhanaparājayo); J i. 379 (kūṭ˚ a false player, sharper, cheat) anakkha one who is not a gambler J v. 116 (C.: ajūtakara). Cp. also accha3 . -- dassa (cp. Sk. akṣadarśaka) one who looks at (i. e. examines) the dice, an umpire, a judge Vin iii. 47; Miln 114, 327, 343 (dhamma -- nagare). -- dhutta one who has the vice of gambling D ii. 348; iii. 183; M iii. 170; Sn 106 (+ itthidhutta & surādhutta). -- vāṭa fence round an arena for wrestling J iv. 81. (? read akka -- ).

దాయము (p. 588) dāyamu dāyamu. [Skt.] n. Heritage. పంచుకొనదగినతంత్రిసొమ్ము. Kinship, heirsh జ్ఞాతిత్వము. A gift, ఈవి. దాయము, దాయలు or దాయాలు dāyamu. [Tel.] n. A certain game among girls. గవ్వలాట; గవ్వలు పాచికలు మొదలగువాని సంఖ్య. (Telugu)

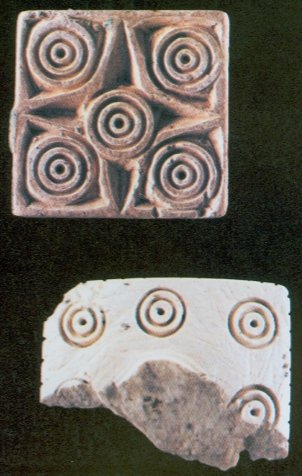

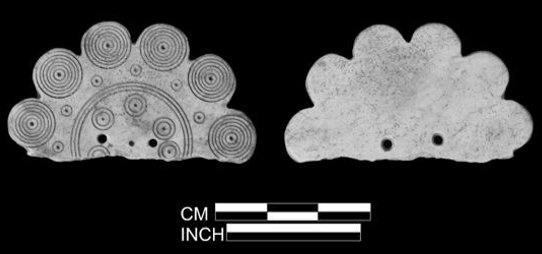

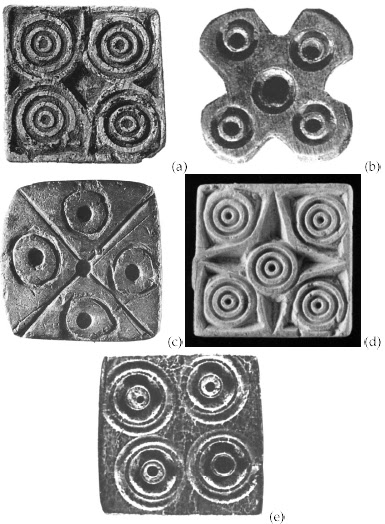

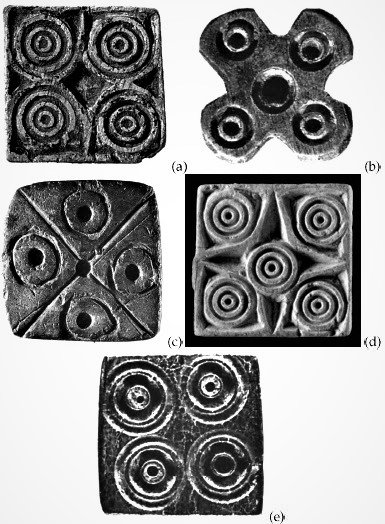

ஏர்த்தாயம் ēr-t-tāyam , n. < id. +. Ploughing in season; பருவகாலத்துழவு. (W.)காணித்தாயவழக்கு kāṇi-t-tāya-vaḻakku, n. < id. +. Dispute between coparceners about hereditary land; பங்காளிகளின் நிலவழக்கு. (J.)தர்மதாயம் tarma-tāyam , n. < id. + dāya. Charitable inams; தருமத்துக்கு விடப்பட்ட மானியம். (G. Sm. D. I, ii, 55.)தாயம் tāyam ![]() Kot Diji type seals with concentric circles from (a,b) Taraqai Qila (Trq-2 &3, after CISI 2: 414), (c,d) Harappa(H-638 after CISI 2: 304, H-1535 after CISI 3.1:211), and (e) Mohenjo-daro (M-1259, aftr CISI 2: 158). (From Fig. 7 Parpola, 2013).

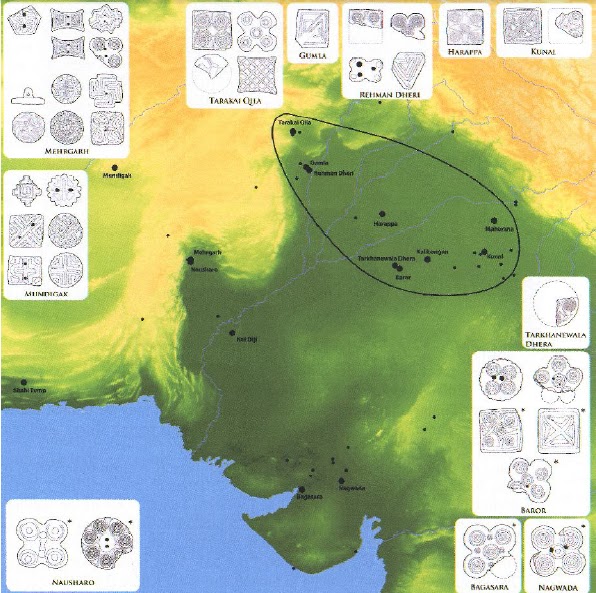

Kot Diji type seals with concentric circles from (a,b) Taraqai Qila (Trq-2 &3, after CISI 2: 414), (c,d) Harappa(H-638 after CISI 2: 304, H-1535 after CISI 3.1:211), and (e) Mohenjo-daro (M-1259, aftr CISI 2: 158). (From Fig. 7 Parpola, 2013).![]() Distribution of geometrical seals in Greater Indus Valley during the early and *Mature Harappan periods (c. 3000 - 2000 BCE). After Uesugi 2011, Development of the Inter-regional interaction system in the Indus valley and beyond: a hypothetical view towards the formation of the urban society' in: Cultural relagions betwen the Indus and the Iranian plateau during the 3rd millennium BCE, ed. Toshiki Osada & Michael Witzel. Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 7. Pp. 359-380. Cambridge, MA: Dept of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University: fig.7

Distribution of geometrical seals in Greater Indus Valley during the early and *Mature Harappan periods (c. 3000 - 2000 BCE). After Uesugi 2011, Development of the Inter-regional interaction system in the Indus valley and beyond: a hypothetical view towards the formation of the urban society' in: Cultural relagions betwen the Indus and the Iranian plateau during the 3rd millennium BCE, ed. Toshiki Osada & Michael Witzel. Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 7. Pp. 359-380. Cambridge, MA: Dept of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University: fig.7![]() Dotted circles and three lines on the obverse of many Failaka/Dilmun seals are read rebus as hieroglyphs: Hieroglyph: ḍāv m. ʻdice-throwʼ rebus: dhāu 'ore'; dã̄u ʻtyingʼ, ḍāv m. ʻdice-throwʼ read rebus: dhāu 'ore' in the context of glosses: dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -smelters', dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ. Thus, three dotted circles signify: tri-dhāu, tri-dhātu 'three ores' (copper, tin, iron).

Dotted circles and three lines on the obverse of many Failaka/Dilmun seals are read rebus as hieroglyphs: Hieroglyph: ḍāv m. ʻdice-throwʼ rebus: dhāu 'ore'; dã̄u ʻtyingʼ, ḍāv m. ʻdice-throwʼ read rebus: dhāu 'ore' in the context of glosses: dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -smelters', dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ. Thus, three dotted circles signify: tri-dhāu, tri-dhātu 'three ores' (copper, tin, iron).![]() A (गोटा) gōṭā Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Rebus: khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (metal) (Marathi) खोट [khōṭa] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ (CDIAL 3931) goTa 'laterite ferrite ore'.

A (गोटा) gōṭā Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Rebus: khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (metal) (Marathi) खोट [khōṭa] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ (CDIAL 3931) goTa 'laterite ferrite ore'.

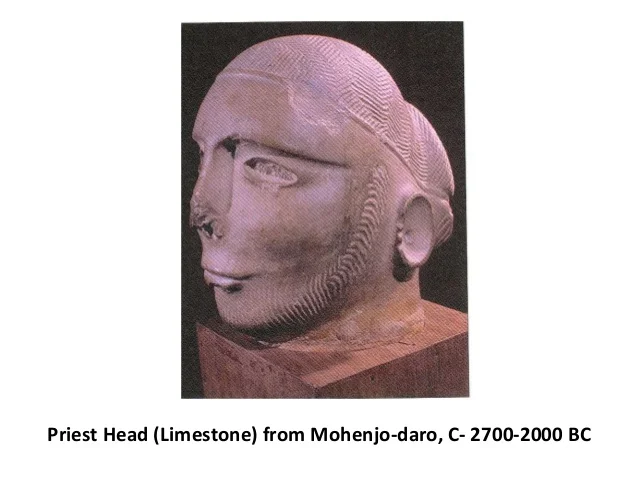

![]() Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.A Stamp seal and its impression from the Harappan site of Lothal north of Bombay, of the type also found in the contemporary cultures of southern Iraq and the Persian Gulf Area. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/archaeology-in-india/These powerful narratives are also validated -- archaeologically attested -- by the discovery of Mohenjo-daro priest wearing (on his forehead and on the right shoulder) fillets of a dotted circle tied to a string and with a uttarīyam decorated with one, two, three dotted circles. The fillet is an Indus Script hypertext which reads: dhã̄i 'strand' PLUS vaṭa 'string' rebus: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'. The same dotted circles enseemble is also shown as a sacred hieroglyph on the bases of Śivalingas found in Mohenjo-dar. The dotted circles are painted with red pigment, the same way as Mosonszentjanos dice are painted with red iron oxide pigment.

Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.A Stamp seal and its impression from the Harappan site of Lothal north of Bombay, of the type also found in the contemporary cultures of southern Iraq and the Persian Gulf Area. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/archaeology-in-india/These powerful narratives are also validated -- archaeologically attested -- by the discovery of Mohenjo-daro priest wearing (on his forehead and on the right shoulder) fillets of a dotted circle tied to a string and with a uttarīyam decorated with one, two, three dotted circles. The fillet is an Indus Script hypertext which reads: dhã̄i 'strand' PLUS vaṭa 'string' rebus: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'. The same dotted circles enseemble is also shown as a sacred hieroglyph on the bases of Śivalingas found in Mohenjo-dar. The dotted circles are painted with red pigment, the same way as Mosonszentjanos dice are painted with red iron oxide pigment.

वट [p= 914,3] m. (perhaps Prakrit for वृत , " surrounded , covered " ; cf. न्यग्-रोध) the Banyan or Indian fig. tree (Ficus Indica) MBh.Ka1v. &c RTL. 337 (also said to be n.); a pawn (in chess) L. (Monier-Williams) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord,string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212. (CDIAL 5220)vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ. (CDIAL 11212).

See: https://tinyurl.com/y85goask Wealth of a nation...

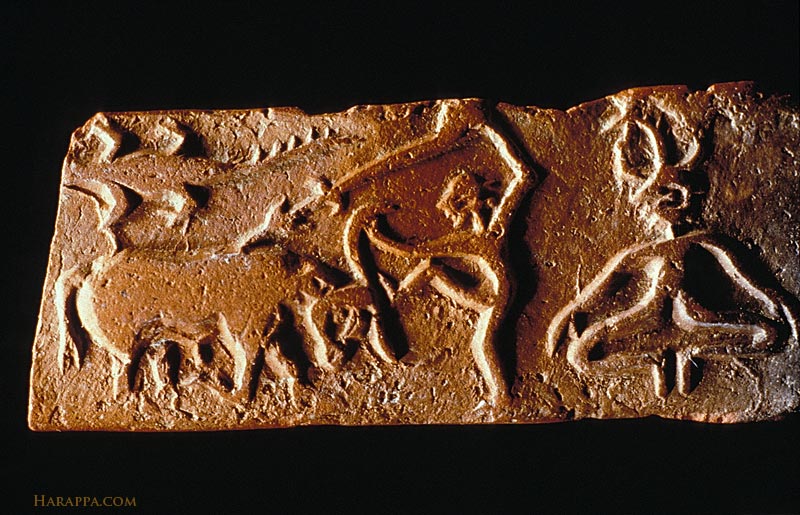

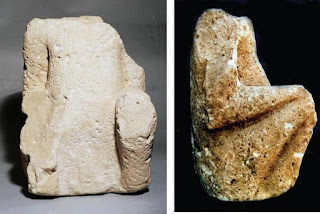

Trefoil decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. Steatite statue fragment. Mohenjo-daro (Sd 767). After Ardeleanu-Jansen, 1989: 196, fig. 1; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 213. Trefoils painted on steatite beads. Harappa (After Vats. Pl. CXXXIII, Fig. 2) Trefoil on the shawl of the priest. Mohenjodaro. The discovery of the King Priest acclaimed by Sir John Marshall as “the finest piece of statuary that has been found at Moenjodaro….draped in an elaborate shawl with corded or rolled over edge, worn over the left shoulder and under the right arm. This shawl is decorated all over with a design of trefoils in relief interspersed occasionally with small circles, the interiors of which are filled with a red pigment “. Gold fillet with ‘standard device’ hieroglyph. Glyph ‘hole’: pottar, பொத்தல் pottal, n. < id. [Ka.poṭṭare, Ma. pottu, Tu.potre.] trika, a group of three (Skt.) The occurrence of a three-fold depiction on a trefoil may thus be a phonetic determinant, a suffix to potṛ as in potṛka.

Rebus reading of the hieroglyph: potti ‘temple-priest’ (Ma.) potr̥ "Purifier"'N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman), यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि (Vedic) Rebus reading is: potri ‘priest’; poTri ‘worship, venerate’. Language is Meluhha (Mleccha) an integral component of Indian sprachbund (linguistic area or language union). The trefoil is decoded and read as: potr(i).

Steatite statue fragment; Mohenjodaro (Sd 767); trefoil-decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989: 196, fig. 1; Parpola, 1994, p. 213.

m0352 cdef

m0352 cdef The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features.

The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Ivory combs. Turkmenistan.

Ivory objects. Sarasvati Civilization

Tablets.Ivory objects. Mohenjo-daro.

Button seal. Baror, Rajasthan.

Button tablet. Harappa. Dotted circles.

தாயம் tāyam:Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

ஏர்த்தாயம் ēr-t-tāyam , n. < id. +. Ploughing in season; பருவகாலத்துழவு. (W.)காணித்தாயவழக்கு kāṇi-t-tāya-vaḻakku, n. < id. +. Dispute between coparceners about hereditary land; பங்காளிகளின் நிலவழக்கு. (J.)தர்மதாயம் tarma-tāyam , n. < id. + dāya. Charitable inams; தருமத்துக்கு விடப்பட்ட மானியம். (G. Sm. D. I, ii, 55.)தாயம் tāyam

वट [p= 914,3] m. (perhaps Prakrit for वृत , " surrounded , covered " ; cf. न्यग्-रोध) the Banyan or Indian fig. tree (Ficus Indica) MBh.Ka1v. &c RTL. 337 (also said to be n.); a pawn (in chess) L. (Monier-Williams) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord,string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212. (CDIAL 5220)vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ. (CDIAL 11212).

See: https://tinyurl.com/y85goask Wealth of a nation...

Trefoil decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. Steatite statue fragment. Mohenjo-daro (Sd 767). After Ardeleanu-Jansen, 1989: 196, fig. 1; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 213. Trefoils painted on steatite beads. Harappa (After Vats. Pl. CXXXIII, Fig. 2) Trefoil on the shawl of the priest. Mohenjodaro. The discovery of the King Priest acclaimed by Sir John Marshall as “the finest piece of statuary that has been found at Moenjodaro….draped in an elaborate shawl with corded or rolled over edge, worn over the left shoulder and under the right arm. This shawl is decorated all over with a design of trefoils in relief interspersed occasionally with small circles, the interiors of which are filled with a red pigment “. Gold fillet with ‘standard device’ hieroglyph. Glyph ‘hole’: pottar, பொத்தல் pottal, n. < id. [Ka.poṭṭare, Ma. pottu, Tu.potre.] trika, a group of three (Skt.) The occurrence of a three-fold depiction on a trefoil may thus be a phonetic determinant, a suffix to potṛ as in potṛka.

Role of dice in Bhāratīya Itihāsa, dotted circle Indus Script hypertexts on ivory game pieces of ANE miners and a tribute to Dennys Frenez, István Koncz and Zsuzsanna Tóth for their brilliant archaeological insights and riveting, logically argued archeo-metallurgical analyses.

![terracotta-dice-ashmolean-museum]()

![]()

![Image result for dice mohenjodaro one]() Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

தாயம் tāyam :Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)தாயம் tāyam:Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

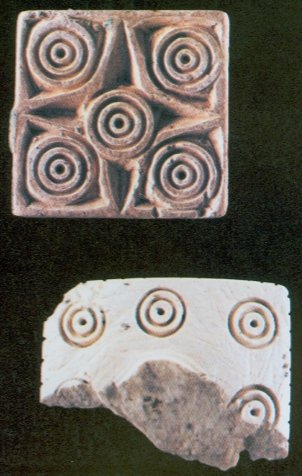

Dotted circles, tulips on ivory combs signify dāntā 'ivory' rebus dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (Rigveda) tagaraka 'tulip' rebus tagara 'tin'![]() Discovery of tin-bronzes was momentous in progressing the Bronze Age Revolution of 4th millennium BCE. This discovery created hard alloys combining copper and tin. This discovery was also complemented by the discovery of writing systems to trade in the newly-produced hard alloys.The discovery found substitute hard alloys, to overcome the scarcity of naturally occurring arsenical copper or arsenical bronzes. The early hieroglyph signifiers of tin and copper on an ivory comb made by Meluhha artisans & seafaring merchants point to the contributions made by Bhāratam Janam (RV), ca. 3300 BCE to produce tin-bronzes. The abiding significance of the 'dotted circle' is noted in the continued use on early Punch-marked coins. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/10/vajra-six-angled-hypertext-of-punch.html Vajra षट्--कोण 'six-angled' hypertext of Punch-marked coins khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint'. A hypertext is orthographed with three arrows emanating from the dotted circle and three ‘twists’ emanating from the dotted circle, thus signifying six-armed semantic extensions. baṭa ‘six’ rebus:baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa ‘furnce’. kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ rebus: khaṇḍa ‘implements’ मेढा mēḍhā ‘twist’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ med ‘copper’ (Slavic languages) medha ‘yajna, dhanam, wealth’.

Discovery of tin-bronzes was momentous in progressing the Bronze Age Revolution of 4th millennium BCE. This discovery created hard alloys combining copper and tin. This discovery was also complemented by the discovery of writing systems to trade in the newly-produced hard alloys.The discovery found substitute hard alloys, to overcome the scarcity of naturally occurring arsenical copper or arsenical bronzes. The early hieroglyph signifiers of tin and copper on an ivory comb made by Meluhha artisans & seafaring merchants point to the contributions made by Bhāratam Janam (RV), ca. 3300 BCE to produce tin-bronzes. The abiding significance of the 'dotted circle' is noted in the continued use on early Punch-marked coins. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/10/vajra-six-angled-hypertext-of-punch.html Vajra षट्--कोण 'six-angled' hypertext of Punch-marked coins khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint'. A hypertext is orthographed with three arrows emanating from the dotted circle and three ‘twists’ emanating from the dotted circle, thus signifying six-armed semantic extensions. baṭa ‘six’ rebus:baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa ‘furnce’. kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ rebus: khaṇḍa ‘implements’ मेढा mēḍhā ‘twist’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ med ‘copper’ (Slavic languages) medha ‘yajna, dhanam, wealth’.

Harappan male ornament styles. After Fig.6.7 in Kenoyer, JM, 1991, Ornament styles of the Indus valley tradition: evidence from recent excavations at Harappa, Pakistan in: Paleorient, vol. 17/2 -1991, p.93 Source: Marshall, 1931: Pl. CXVIII

http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/Kenoyer1992_Ornament%20Styles%20of%20the%20Indus%20Valley%20Tradition%20Ev.pdfClearly, the wearing a fillet on the shoulder and wearing a dress with trefoil hieroglyphs made the figure of some significance to the community.

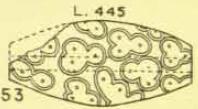

"Inlaid bead. No. 53 (L445). (See also Pl. CLII,17) Steatite. An exceptionally fine bead. The interiors of the trefoils were probably filled in with either paste or colour. The former is the more probable, for in the base of each foil there is a small pitting that may been used for keying a coloured paste. The depth of the cutting is 0.05 inch. Level, 3 feet below surface. late Period. Found in Chamber 27, Block 4, L Area. The most interesting of these beads are those with the trefoil pattern, which also occurs on the robe worn by the statue pictured in Pl. XCVIII. The trefoils on both the beads and statue are irregular in shape and in this respect differ from the pattern as we ordinarily know it. (For another example of this ornamentation, see the bull illustrated in Jastrow, Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria, pl. liii, and the Sumerian bull from Warka shown in Evans, Palace of Minos, vol. ii, pt. 1, p.261, fig. 156. Sir Arthus Evans has justly compared the trefoil markings on this latter bull with the quatrefoil markings of Minoan 'rytons', and also with the star-crosses on Hathor's cow. Ibid., vol. i, p.513. Again, the same trefoil motif is perhaps represented on a painted sherd from Tchechme-Ali in the environs of Teheran. Mem. Del. en Perse, t.XX, p. 118, fig. 6)."(John Marshall, opcit., p.517)

Trefoil Decorated bead. Pl. CXLVI, 53 (Marshall, opcit.)

Hieroglyph-multiplex of dotted circles as 'beads': kandi 'bead' Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' khaNDa 'metal implements'. Alternative: dotted circles as dice: dhāv, dāya 'one in dice' + vaṭṭa 'circle' rebus धावड dhāvaḍa 'red ferrite ore smelter'

Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'. Alternative: kole.l धावड dhāvaḍa 'temple PLUS red ferrite ore smelter'.

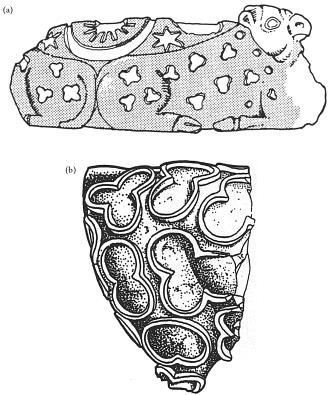

(After Fig. 18.10 Parpola, 2015, p. 232) (a) Neo-Sumerian steatite bowl from Ur (U.239), bearing symbols of the sun, the moon (crucible), stars and trefoils (b) Fragmentary steatite statuette from Mohenjo-daro. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989-205, fig. 19 and 196, fig. 1a. koṭhārī ʻ

A finely polished pedestal. Dark red stone. Trefoils. (DK 4480, cf. Mackay 1938: I, 412 and II, pl. 107.35). National Museum, Karachi.

Hieroglyph: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy'; kolle 'blacksmith'; kole.l 'smithy, temple' (Kota) Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'. Alternative: kole.l धावड dhāvaḍa 'temple PLUS red ferrite ore smelter'.

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)![]() Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.com

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.comHieroglyph markhor, ram: mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m.,°ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M.mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ (CDIAL 10310). Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.)Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'. Alternative: kole.l धावड dhāvaḍa 'temple PLUS red ferrite ore smelter'.![]() Trefoil inlay decorated on a bull calf. Uruk (W.16017) ca. 3000 BCE. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge); kundaṇa 'fine gold'.

Trefoil inlay decorated on a bull calf. Uruk (W.16017) ca. 3000 BCE. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge); kundaṇa 'fine gold'.

damkom = a bull calf (Santali) Rebus: damha = a fireplace; dumhe = to heap, to collect together (Santali)Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'. Alternative: kole.l धावड dhāvaḍa 'temple PLUS red ferrite ore smelter'.

http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/Kenoyer1992_Ornament%20Styles%20of%20the%20Indus%20Valley%20Tradition%20Ev.pdf

"Inlaid bead. No. 53 (L445). (See also Pl. CLII,17) Steatite. An exceptionally fine bead. The interiors of the trefoils were probably filled in with either paste or colour. The former is the more probable, for in the base of each foil there is a small pitting that may been used for keying a coloured paste. The depth of the cutting is 0.05 inch. Level, 3 feet below surface. late Period. Found in Chamber 27, Block 4, L Area. The most interesting of these beads are those with the trefoil pattern, which also occurs on the robe worn by the statue pictured in Pl. XCVIII. The trefoils on both the beads and statue are irregular in shape and in this respect differ from the pattern as we ordinarily know it. (For another example of this ornamentation, see the bull illustrated in Jastrow, Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria, pl. liii, and the Sumerian bull from Warka shown in Evans, Palace of Minos, vol. ii, pt. 1, p.261, fig. 156. Sir Arthus Evans has justly compared the trefoil markings on this latter bull with the quatrefoil markings of Minoan 'rytons', and also with the star-crosses on Hathor's cow. Ibid., vol. i, p.513. Again, the same trefoil motif is perhaps represented on a painted sherd from Tchechme-Ali in the environs of Teheran. Mem. Del. en Perse, t.XX, p. 118, fig. 6)."(John Marshall, opcit., p.517)

Trefoil Decorated bead. Pl. CXLVI, 53 (Marshall, opcit.)

Hieroglyph-multiplex of dotted circles as 'beads': kandi 'bead' Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' khaNDa 'metal implements'. Alternative: dotted circles as dice: dhāv, dāya 'one in dice' + vaṭṭa 'circle' rebus धावड dhāvaḍa 'red ferrite ore smelter'

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.com

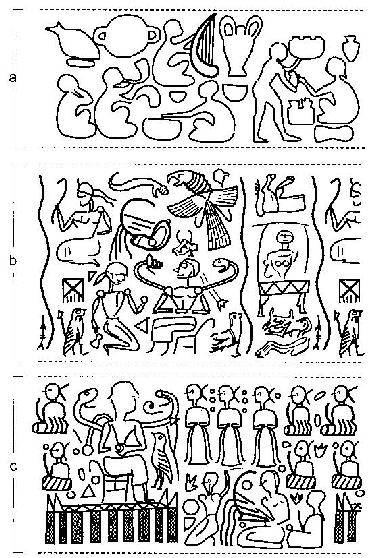

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.comHieroglyph markhor, ram: mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m.,°ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M.mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ (CDIAL 10310). Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.)Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'. Alternative: kole.l धावड dhāvaḍa 'temple PLUS red ferrite ore smelter'.a. Symmetry of tigers, scorpions, lizards (KK Hall, Catalogue of Egyptian scarabs in the British Museum, Royal scarabs, British Museum, London, 1902)

![]() b. Seal with lion and antelope; c. Two crocodiles, two scorpions. (J. Ward, 1902, The sacred beetle a popular treatise on Egyptian scarabs in art and history, John Murray, London, 1902).Two seals of the Egyptian Museum Collection, Torino with bilateral and rotational symmetries.

b. Seal with lion and antelope; c. Two crocodiles, two scorpions. (J. Ward, 1902, The sacred beetle a popular treatise on Egyptian scarabs in art and history, John Murray, London, 1902).Two seals of the Egyptian Museum Collection, Torino with bilateral and rotational symmetries.

From the Egyptian Museum of Torino. A cowroid seal with lentoid shape, like a cowrie shell. Dated to ca. 2200=2040 BCE.

Symmetries on seals parallel symmetries in patterns woven into textiles. Symmetries are orthographic rebus representations achieved by Indus Script Cipher with the underlying Meluhha words (of Indian sparchbund, 'speech union').Scarab is a representation of the image of a beetle. Scarabs are a gem hut, a common type of amulet, seal or ring bezel found in Egypt, Nubia and Syria from the 6th Dynasty until the Ptolemaih Period (2345-30 BC). The earliest were purely amulet and uninscribed: it was only during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BC) that they were used as seals. The scarab seal is so called because it was made in the shape of the sacred scarab beetle (scarabaeus sacer), which was personified by Khepri, a sun god associated with resurrection. The flat underside of the scarab, carved in stone or moulded in faience or glass, was usually decorated with designs or inscriptions, sometimes incorporating a royal name. "Finely carved scarabs were used as seals; inscribed scarabs were issued to commemorate important events or buried with mummies. Lapis Luzauli was a mineral often used... Over the ages, they have been used to symbolise wealth, used as currency, fashion accessory and also to serve as a form of artistic expression. Precious metals and stones were used from very earl ages as a sign of wealth and opulence. Royalty have always used Scarabs as a means for securing and consolidating wealth and even to the present day, some of the most precious pieces of jewelry are antiques. Royal jewels rank among the most expensive and luxurious assets of all times. " https://www.gemrockauctions.com/fr/learn/did-you-know/what-is-the-meaning-of-scarab

![Related image]()

![Image result for scarabs]()

Stamp seal. Dilmun. http://www.uaeinteract.com Mirror symmetry is achieved in two parts flanking the crucible+Sun pictograph. The antelope looking backward is clearly influenced by the Indus Script orthography. Four of two pairs of almost identical aquatic birds are shown.

“One of the biggest surprises of the excavations at Saar has been the enormous amount of glyptic material present. We have now more than 80 round stamp seals made of chlorite steatite and 300-400 fragments of seal impressions, all in the local Early Dilmun style…The seals were apparently mainly used for economic purposes, implying that much of the Saar population was actively engaged in the exchange of goods, and perhaps in their manufacture. Because all the seals and seal impressions are in the native Early Dilmun style, it also shows that most of the commerce for which we have evidence was taking place within the Dilmun polity itself. The limited range of foreign goods for which we have evidence were probably redistributed from their port of entry.” -- Harriet Crawford (1997, ibid.)

The earliest evidence of impressing carved stones into clay to seal containers is from Syria dated to 7th millennium BCE.During the Ubaid period, designs of geometric forms expanded to include animals and human images, snakes and birds.Stamp seal from the region North Syria, Iraq (image redrawn from M. Schoyen, Seals, at www.schoyencollection.com/index.html), dated 5th-4thmillennium BCE. A standing male figure is seen between two horned quadrupeds back to back and head to tail. The rotational symmetry of the animals is two-fold.![]() Stamp seal from Susa (image redrawn from www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/sarasvati/lapis_lazuli.htm, at the Louvre Museum). Susa is the oldest known settlement of the world, founded ca. 4200 BCE; inhabited villages of Susa have been dated to 7000 BCE. The seal depicts two goat-antelopes head to tail, and an oval at the centre. The two antelopes seem to be running on the rim of the seal. (http://www.ijSciences.com Intl Journal of Sciences, Volume 2, Issue August 2013.)

Stamp seal from Susa (image redrawn from www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/sarasvati/lapis_lazuli.htm, at the Louvre Museum). Susa is the oldest known settlement of the world, founded ca. 4200 BCE; inhabited villages of Susa have been dated to 7000 BCE. The seal depicts two goat-antelopes head to tail, and an oval at the centre. The two antelopes seem to be running on the rim of the seal. (http://www.ijSciences.com Intl Journal of Sciences, Volume 2, Issue August 2013.)

Indus writing in ancient Near East (Failaka seal readings)

Dotted circles and three lines on the obverse of many Failaka/Dilmun seals are read rebus as hieroglyphs:

![]()

A (गोटा) gōṭā Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Rebus: khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (metal) (Marathi) खोट [khōṭa] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ (CDIAL 3931)

kolom ‘three’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Thus, the seals are intended to serve as metalware catalogs from the smithy/forge. Details of the alloyed metalware are provided by the hieroglyphs of Indus writing on the reverse of the seal.

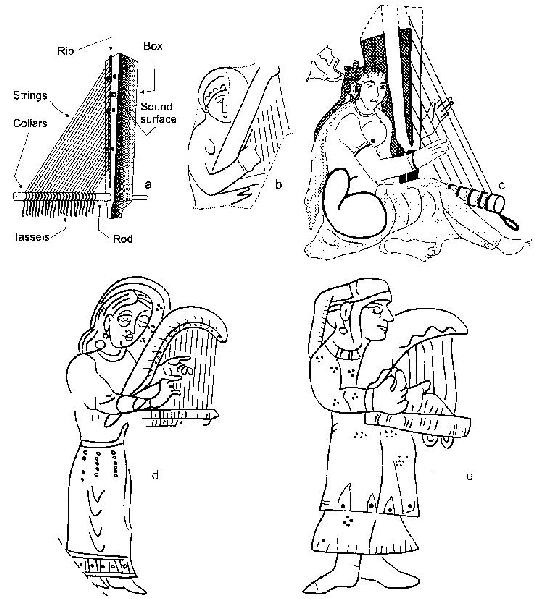

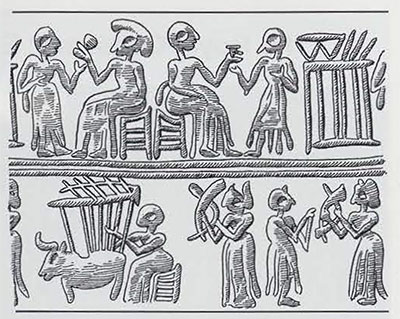

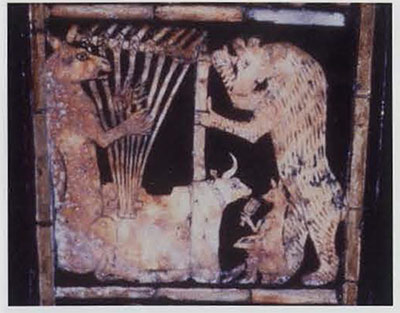

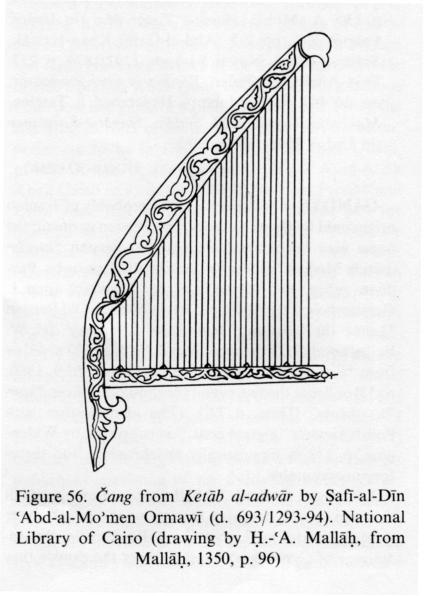

![]() Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] or తంబురా tambura. [Tel. తంతి +బుర్ర .] n. A kind of stringed instrument like the guitar. A tambourine. Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.) tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'.

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of tin and copper.

![]() Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Hieroglyphs on this Dilmun seal are: star, tabernae montana flower, cock, two divided squares, two bulls, antelope, sprout (paddy plant), drinking (straw), stool, twig or tree branch. A person with upraised arm in front of the antelope. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus using lexemes (Meluhha, Mleccha) of Indiansprachbund.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

ṭagara (tagara) fragrant wood (Pkt.Skt.).tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi) dula 'pair' (Kashmiri). Rebus: dul 'cast metal' (Santali) Thus, a pair of bulls connote 'cast metal blacksmith'.

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali)

Tu. aḍaru twig. Rebus: aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal' (Kannada) Alternative reading: కండె [kaṇḍe] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Te.); eraka ‘copper’ (Te.)

Thus, the Dilmun seal is a metalware catalog of damgar 'merchant' dealing with copper and tin.

The two divided squares attached to the straws of two vases in the following seal can also be read as hieroglyphs:

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangā = small country boat, dug-out canoe (Or.); ḍõgā trough, canoe, ladle (H.)(CDIAL 5568). Rebus: ḍānro term of contempt for a blacksmith (N.); ḍangar (H.) (CDIAL 5524)

Thus, a smelting furnace for stone (ore) is connoted by the seal of a blacksmith, ḍangar :

Stamp seal with a boat scene. Steatite. L. 2 cm. Gulf regio, Failaka, F6 758. Early Dilmun, ca. 2000-1800 BCE. Ntional Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum, 1129 ADY. The subject is a nude male figure standing in the middle of a flat-bottomed boat, facing right. The man's arms are bent at the elbow, perpendicular to his torso. Beside him are two jars stand on the deck of the boat, each containing a long pole to which is attached a hatched square that perhaps represents a banner. Six square stamp seals from Failaka have been published...It is unlikely that the hatched squares represent sails, since the poles to which they are attached emerge from vases. The two diagonal lines on the body of the boat may represent the reed bundles from which these craft were buit. See Kjaerum 1983, seal nos. 192, 234, 254, 266, 335, 367. Source: Source: Joan Aruz et al., 2003, Art of the First cities: the third millennium BCE from the Mediterranean to the Indus, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (Pages 320, 322).See also: http://ancientworldonline.blogspot.in/2012/10/kuwaiti-slovak-archaeological-mission.html

Similar readings are suggested for all hieroglyphs on Failaka seals treating them as evidences of Indus writing in ancient Near East. The suggested rebus readings for specific hieroglyphs of Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings) are listed in the following section.

Note: What is shown like the phase of a moon may not denote a moon but the shape of a bun-ingot. ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’. Alternative reading: mū̃h 'ingot'. Read together with the polar star, the rebus reading is: meḍ mū̃h 'iron ingot'. [meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)] The antelope + divided square is read rebus: eraka tagara kaṇḍ 'tin furnace' (merchant, damgar). The upraised arm indicates eraka 'copper': eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Telugu); eraka ‘copper’ (Telugu) Thus, the seal denotes a merchant dealing in iron, tin and copper ingots.

Rebus readings of hieroglyphs on Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings):

తంబుర [tambura] or తంబురా tambura. [Tel. తంతి +బుర్ర .] n. A kind of stringed instrument like the guitar. A tambourine. Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.)

Skt. kuṭī- intoxicating liquor. Ta. kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale; n. drinking, beverage (DEDR 1654). Rebus: kuṭhi‘smelting furnace’.

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali); kolom = cutting, graft; to graft, engraft, prune; kolma hoṛo = a variety of the paddy plant (Desi)(Santali.) kolom ‘three’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298). खडा (Marathi) is ‘metal, nodule, stone, lump’. kaṇi ‘stone’ (Kannada) with Tadbhava khaḍu. khaḍu, kaṇ ‘stone/nodule (metal)’. Rebus: khaṇḍaran, khaṇḍrun ‘pit furnace’ (Santali) kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Skt.) लोहकारकन्दुः f. a blacksmith's smelting furnace (Grierson Kashmiri lex.) [khaṇḍa] A piece, bit, fragment, portion.(Marathi) Rebus: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

Allographs: Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) खंड [ khaṇḍa ] A piece, bit, fragment, portion.(Marathi) khaṇḍ ‘ivory’ (H.) jaṇḍ khaṇḍ = ivory (Jaṭkī) khaṇḍ ī = ivory in rough (Jaṭkī) kandhi = a lump, a piece (Santali.lex.) kandi (pl. -l) beads, necklace (Pa.); kanti (pl. -l) bead, (pl.) necklace; kandit. bead (Ga.)(DEDR 1215).

Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. (DEDR 1159a) Rebus ‘brazier, bell-metal worker’: கன்னான் kaṉṉāṉ , n. < கன்¹. [M. kannān.] Brazier, bell-metal worker, one of the divisions of the Kammāḷa caste; செம்புகொட்டி. (திவா.) కండె [ kaṇḍe ] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. జొన్నకంకి (Telugu) kã̄ṛ ʻstack of stalks of large milletʼ(Maithili) kã̄ḍ 2 काँड् m. a section, part in general; a cluster, bundle, multitude (Śiv. 32). kã̄ḍ 1 काँड् । काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed, grass, or the like, straw. In the compound with dan 5 (p. 221a, l. 13) the word is spelt kāḍ.

Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330).

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.) Allograph: meḍh ‘ram’.

satthiya ‘svastika glyph’; rebus: satthiya ‘pewter’.

Skt. kuṭī- intoxicating liquor. (DEDR 1654) Ta. kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale; n. drinking, beverage,drunkenness; kuṭiyaṉ drunkard. Rebus: kuṭi= smelter furnace (Santali)

gaṇḍ 'four'. kaṇḍ 'bit'. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar'. kolmo 'three'. Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

tagara 'antelope'; rebus 1: tagara 'tin'; rebus 2: tamkāru, damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

The bamboo-shoot is tã̄bā read rebus: tamba 'copper'.

B. Or. bichā 'scorpion', Mth. bīch (CDIAL 12081) Rebus: meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.) bica, bica-diri (Sad. bicā; Or. bicī) stone ore; meṛeḍ bica, stones containing iron; tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.)

kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) Rebus:kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire altar, consecrated fire’.

mūxā ‘frog’. Rebus: mũh ‘(copper) ingot’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end (Santali) Allographs: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) मोख [ mōkha ] . Add:--3 Sprout or shoot. (Marathi) Kuwi (Su.) mṛogla shoot of bamboo; (P.) moko sprout (DEDR 4997) Tu. mugiyuni to close, contract, shut up; muguru sprout, shoot, bud; tender, delicate; muguruni, mukuruni to bud, sprout; muggè, moggè flower-bud, germ; (BRR; Bhattacharya, non-brahmin informant) mukkè bud. Kor. (O.) mūke flower-bud. (DEDR 4893)

pajhar. = to sprout from a root (Santali) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi)

ḍumgara ‘mountain’ (Pkt.)(CDIAL 5423). Rebus: damgar ‘merchant’.

kangha (IL 1333) kãgherā comb-maker (H.) Rebus: kangar ‘portable furnace’

गोदा [ gōdā ] m A circular brand or mark made by actual cautery (Marathi) गोटा [ gōṭā ] m A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble (of stone, lac, wood &c.) 2 A marble. 3 A large lifting stone. Used in trials of strength among the Athletæ. 4 A stone in temples described at length underउचला 5 fig. A term for a round, fleshy, well-filled body. 6 A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe. गोटुळा or गोटोळा [ gōṭuḷā or gōṭōḷā ] a (गोटा) Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Allographs: Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool (DEDR 2200) Koḍ. ko·ḷi fowl. Tu. kōri, (B-K. also) kōḷi id. Te. kōḍi id. Nk. (Ch.) gogoḍi, gogoṛi cock (< Go.). Go. (Tr.) gōgōṛi, (Ph.)gugoṛī, (Y.) ghogṛi, (Mu. Ma. S. Ko.) gogoṛ id. (Voc. 1184). Cf. Apabhraṃśa (Jasaharacariu) koḍi- id., fowl. (DEDR 2248). Rebus: khoṭ ‘alloy’ (Marathi). खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ M.khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ, (CDIAL 3931) Rebus: khoṭ ‘alloy’ (Marathi). खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ M.khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ, (CDIAL 3931)

தமரூசி tamar-ūci, n. < தமர்² +. 1. See தமர்², 2. 2. Bits of a brace; தமரில் மாட்டும் ஆணி. தமர்² tamar , n. [M. tamar.] 1. Hole, as in a plank, commonly bored or cut; கருவியால் அமைத்த துளை. தமரிடு கருவியாம் (திருவிளை. மாணிக்க. 61). 2. Gimlet, spring awl, boring instrument; துளையிடுங் கருவி. Ta. tamar hole in a plank, commonly bored or cut; gimlet, spring awl, boring instrument; tavar (-v-, -nt-) to bore a hole; n. hole in a board. Ma. tamar hole made by a gimlet; a borer, gimlet, drill. ? Ko. tav- (tavd-) to butt with both horns, gore. Tu. tamirů gimlet. Te. tamire, (VPK) tagire the pin in the middle of a yoke. (DEDR 3078) āˊrā f. ʻ shoemaker's awl ʼ RV. Pa. Pk. ārā -- f. ʻ awl ʼ; Ash. arċūˊċ ʻ needle ʼ; K. örü f. ʻ shoemaker's awl ʼ, S. āra f., L. ār f.; P. ār f. ʻ awl, point of a goad ʼ; N. āro ʻ awl ʼ; A. āl ʻ sharp point, spur ʼ; B. ārā ʻ awl ʼ, Or. āra, āri, Bi. ār, araī, aruā, (Patna) arauā ʻ spike at the end of a driving stick ʼ, Mth. aruā, (SETirhut) ār ʻ cobbler's awl ʼ; H. ār f. ʻ awl, goad ʼ, ārī f. ʻ awl ʼ, araī ʻ goad ʼ, ārā m. ʻ shoemaker's awl or knife ʼ; G. M. ār f. ʻ pointed iron spike ʼ; M. ārī, arī ʻ cobbler's awl ʼ.Addenda: āˊrā -- : S.kcch. ār f. ʻpointed iron spikeʼ.(CDIAL 1313) Rebus: ताम्रिकः A brazier coppersmith (Sanskrit)

ayo ‘fish’(Mu.); ayas ‘iron’ (Skt.) Rebus: ayas ‘metal’

ḍato ‘claws or pincers (chelae) of crabs’; ḍaṭom, ḍiṭom to seize with the claws or pincers, as crabs, scorpions; ḍaṭkop = to pinch, nip (only of crabs) (Santali) Rebus: dhātu ‘mineral’ (Vedic); dhatu ‘a mineral, metal’ (Santali)

Allographs:1. aru m. ʻ sun ʼ lex. Kho. yor Morgenstierne NTS ii 276 with ? <-> Whence y -- ? (CDIAL 612)2. aru(m), eru(m), harum "branch, frond " of date palm (Akkadian) Akkadian aru/eru may be equivalent of the Hebrew 'rh 'eagle'. The concise dictionary of Akkadian (Jeremy A. Black, 2000) notes: eru, aru, also ru 'eagle'. aru 'granary, storehouse' OA, jB lex. aru(m) 'warrior'.

Rebus: eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.) eruvai ‘copper’ (Ta.); ere dark red (Ka.)(DEDR 446). eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.) Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt (DEDR 866)

Ta. kara-tāḷam palmyra palm. Ka. kara-tāḷa fan-palm, Corypha umbraculifera Lin. Tu. karatāḷa cadjan. Te. (B.) kara-tāḷamu the small-leaved palm tree.(DEDR 1270). karukku teeth of a saw or sickle, jagged edge of palmyra leaf-stalk, sharpness (Ta.) Ka. garasu. / Cf. Skt. karaṭa- a low, unruly, difficult person; karkara- hard, firm; karkaśa- rough, harsh, hard; krakaca-, karapattra- saw; khara- hard, harsh, rough, sharp-edged; kharu- harsh, cruel; Pali kakaca- saw; khara- rough; saw; Pkt.karakaya- saw; Apabhraṃśa (Jasaharacariu) karaḍa- hard. Cf. esp. Turner, CDIAL, no. 2819. Cf. also Skt. karavāla- sword (for second element, cf. 5376 Ta. vāḷ). (DEDR 1265) Allograph: Ta. karaṭi, karuṭi, keruṭi fencing, school or gymnasium where wrestling and fencing are taught. Ka. garaḍi, garuḍi fencing school. Tu.garaḍi, garoḍi id. Te. gariḍi, gariḍī id., fencing.(DEDR 1262)

Ko. meṭ- (mec-) to trample on, tread on; meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (DEDR 5057). Allograph: meḍ ‘dance’ (Santali). mēḍamu. A fight, battle, యుద్ధము. మేడము పొడుచు mēdamu-poḍuṭsu. v. n. To fight a battle. M. meḍhā m. ʻ curl, snarl, twist or tangle in cord or thread ʼ (CDIAL 10312) మేడెము [ mēḍemu ] or మేడియము mēḍemu. [Tel.] n. A spear or dagger. ఈటె, బాకు. mēḍha The polar star. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ, mẽṛhẽt 'iron'(Mu.Ho.)

ḍabe, ḍabea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali)

See:http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/indus-writing-on-gold-disc-kuwait.html Indus writing on gold disc, Kuwait Museum al-Sabah collection: An Indus metalware cataloghttp://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/see-httpbharatkalyan97.html Indus writing in ancient Near East (Dilmun seal readings)

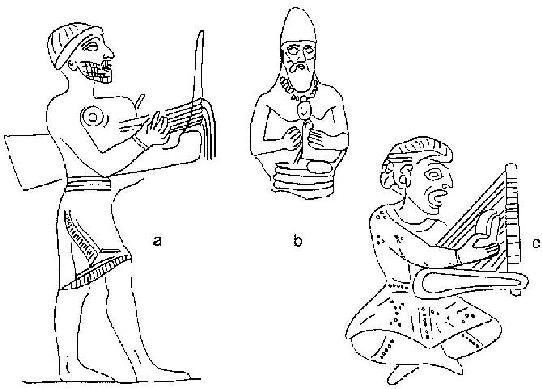

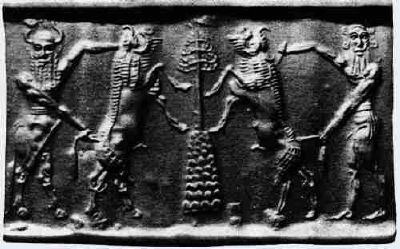

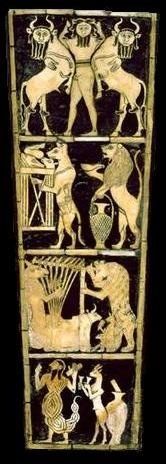

Stamp seal with figures and animals. Steatite. Early Dilmun, ca. 2000-1800 BCE. Dia. 2.9 cm. Gulf region, Bahrain, Karrana, Bahrain National Museum, Manama![]() Designs of stamp seals from Al-Khidr are composed of characteristic Early Dilmun stamp seal motifs. This stamp seal depicts human and half-human-half-animal horned figures, monkeys, serpents and birds on either side of a central motif of a standard and a podium at the bottom (drawing of stamp seal impression).

Designs of stamp seals from Al-Khidr are composed of characteristic Early Dilmun stamp seal motifs. This stamp seal depicts human and half-human-half-animal horned figures, monkeys, serpents and birds on either side of a central motif of a standard and a podium at the bottom (drawing of stamp seal impression).![]() On the obverse of Dilmun seals from Al-Khidr are depicted human or divine figures, half human-half animal creatures, animal figures (such as gazelles, bulls, scorpions, and snakes), celestial bodies (star or sun and moon), sometimes drinking scenes and also other activities (playing musical instruments). Composition of these motifs varies from formal (with ordering the figures and symbols to clear scenes) to chaotic.

On the obverse of Dilmun seals from Al-Khidr are depicted human or divine figures, half human-half animal creatures, animal figures (such as gazelles, bulls, scorpions, and snakes), celestial bodies (star or sun and moon), sometimes drinking scenes and also other activities (playing musical instruments). Composition of these motifs varies from formal (with ordering the figures and symbols to clear scenes) to chaotic. ![]()

![]()

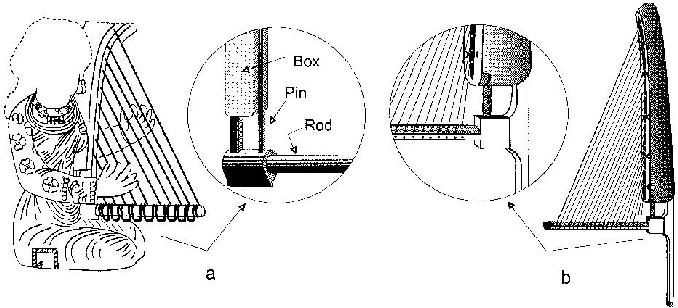

![]() Seals with rotating designs usually bear pure plant, animal or geometric motifs.

Seals with rotating designs usually bear pure plant, animal or geometric motifs.

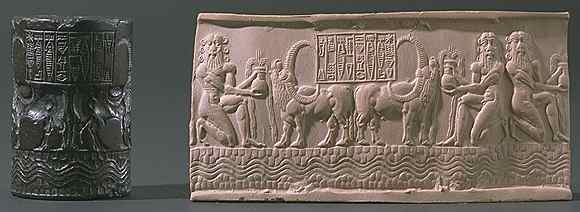

![]() Until now only one single seaal has been discovered (in 2004) which comes from a non-Dilmun cultural environment. It is a cylinder seal with a cuneiform inscription that refers to "Ab-gina, sailor from a huge ship, the son of Ur-Abba" (F. Rahman). This seal provides further evidence of the existing contacts between Dilmun and ancient Mesopotamia at the end of the 3rd- beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Until now only one single seaal has been discovered (in 2004) which comes from a non-Dilmun cultural environment. It is a cylinder seal with a cuneiform inscription that refers to "Ab-gina, sailor from a huge ship, the son of Ur-Abba" (F. Rahman). This seal provides further evidence of the existing contacts between Dilmun and ancient Mesopotamia at the end of the 3rd- beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE.

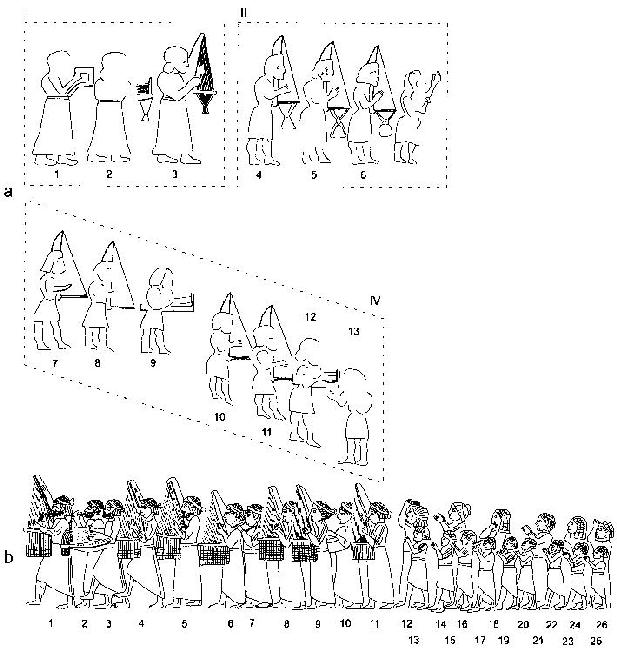

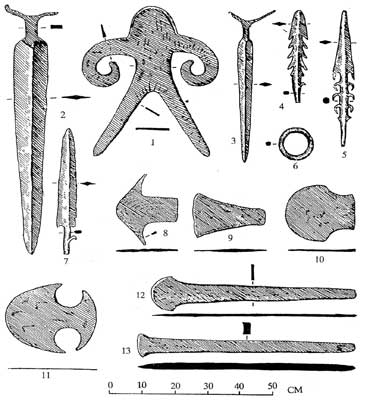

![]() A minor fragment of a globularly shaped metal sheet may represent a fragment of a vessel.

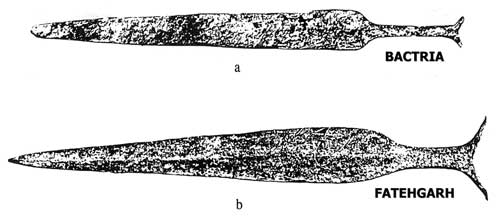

A minor fragment of a globularly shaped metal sheet may represent a fragment of a vessel. ![]() Blades are technologically more demanding than awls and fish-hooks. A few complete pieces and some major fragments seem to represent knives and perhaps razors.

Blades are technologically more demanding than awls and fish-hooks. A few complete pieces and some major fragments seem to represent knives and perhaps razors.![]() Metal awls are made from thin copper rods of circular or rectangular section. Most of them have both ends pointed. A handful of pieces have simple handles from bird and mammal bones. These awls may have been used for various purposes. Large amounts of shells at the site may indicate that the awls could have served to open and take out the flesh from the shells of bivalves and gastropods.

Metal awls are made from thin copper rods of circular or rectangular section. Most of them have both ends pointed. A handful of pieces have simple handles from bird and mammal bones. These awls may have been used for various purposes. Large amounts of shells at the site may indicate that the awls could have served to open and take out the flesh from the shells of bivalves and gastropods.

![]() Two tanged arrowheads have been found.

Two tanged arrowheads have been found. ![]() From among other utensils, needles with eyes and a pair of tweezers have been uncovered.

From among other utensils, needles with eyes and a pair of tweezers have been uncovered. ![]() Collection of copper fish-hooks.

Collection of copper fish-hooks.![]() Besides vessels, steatite was used for the production of stamp seals and small personal ornaments (pendants). Sherds of broken vessels were further used also as tools (e.g. polishers).

Besides vessels, steatite was used for the production of stamp seals and small personal ornaments (pendants). Sherds of broken vessels were further used also as tools (e.g. polishers).![]()

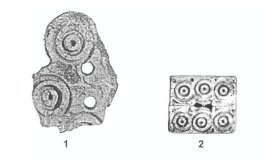

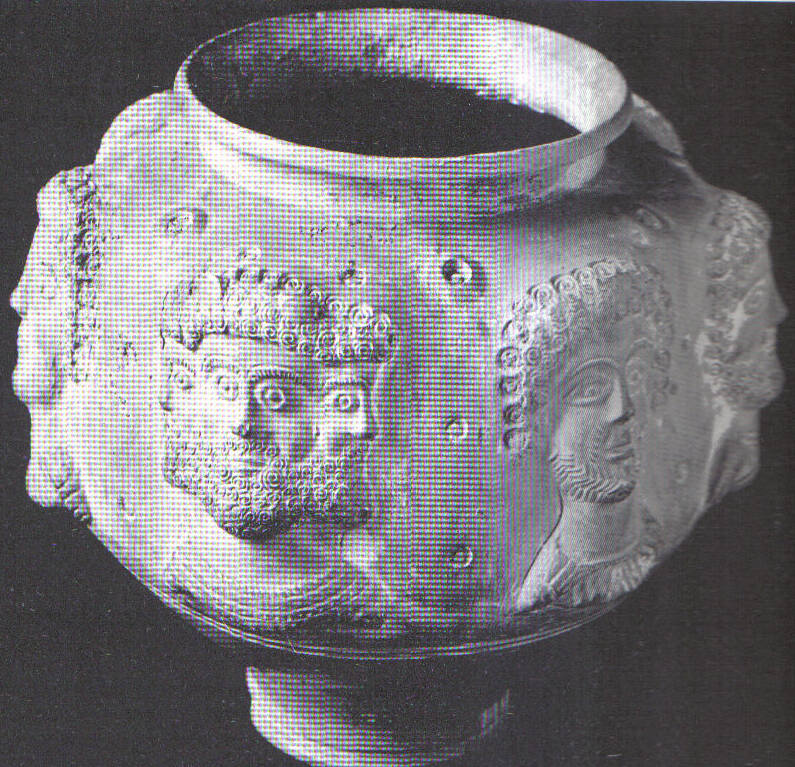

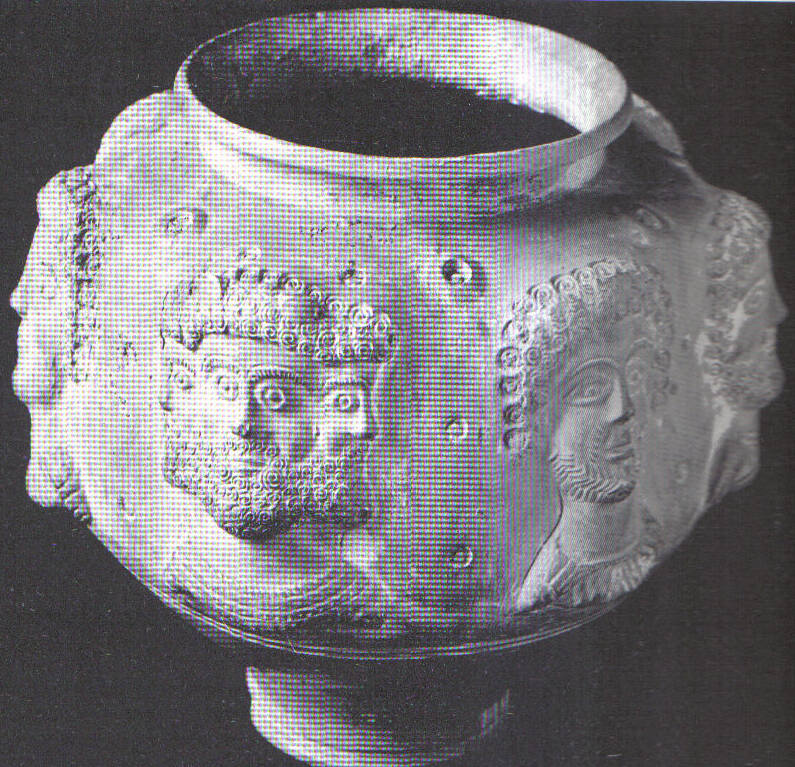

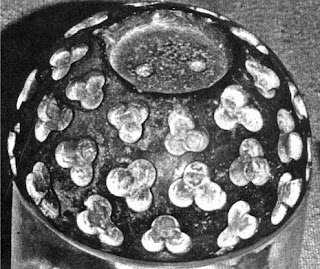

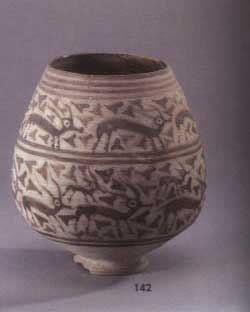

![]() Typical globular bowl with incised decoration (dotted-circles).

Typical globular bowl with incised decoration (dotted-circles).![]() Small carnelian bead (pointing to link with Gujarat as the possible source of carnelian).

Small carnelian bead (pointing to link with Gujarat as the possible source of carnelian).![]() Net sinker (left) and limestone lid (above). The local limestone was also used for the production of working slabs, grinders and grindstones (below).Pearls were recovered from heavy residue fractions of the soil samples processed by water flotation. They almost exclusively occur in contexts dominated by mother-of-pearl shells.

Net sinker (left) and limestone lid (above). The local limestone was also used for the production of working slabs, grinders and grindstones (below).Pearls were recovered from heavy residue fractions of the soil samples processed by water flotation. They almost exclusively occur in contexts dominated by mother-of-pearl shells.![]() Stamp seal cut from shell nacre layers (above). Pendant made from a strombus shell (left). Semi-product made from an oyster shell (right).

Stamp seal cut from shell nacre layers (above). Pendant made from a strombus shell (left). Semi-product made from an oyster shell (right).

Source. http://www.kuwaitarchaeology.org/gallery/al-khidr-finds-2.html Kuwaiti-Slovak Archaeological Mission

Failaka Island is located approximately 20 km northeast of Kuwait City. The island has a shallow surface measuring 12 km in length and 6 km width. The island proved to be an ideal location for human settlements, because of the wealth of natural resources, including harbours, fresh water, and fertile soil. It was also a strategic maritime commercial route that linked the northern side of the Gulf to the southern side. Studies show that traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC and extended through most of the 20th century CE.

Failaka was first known as Agarum, the land of Enzak, the great god of Dilmun civilisation according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island. Dilmun was the leading commercial hub for its powerful neighbours in their need to exchange processed goods for raw materials. Sailing the Arabian Gulf was by far the most convenient trade route at a time as transportation over land meant a much longer and more hazardous journey. As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the activities which radiated around Dilmun (Bahrain) from the end of the 3rd millennium to the mid-1st millennium BCE.

The cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Harappan people from the Indus Valley, the inhabitants of Magan and the Iranian hinterland have left many archaeological traces of their encounters on Failaka Island. More speculative is the ongoing debate among academics on whether Failaka might be the mythical Eden: the place where Sumerian hero Gilgamesh almost unraveled the secret of immortality; the paradise later described in the Bible.

As a result of changes in the balance of political powers in the region towards the end of the 2nd millennium BCE and beginning of 1st millennium BCE, the importance of Failaka began to decline.

Studies indicate that Alexander the Great received reports from missions sent to explore the Arabian shoreline of the Gulf. The reports referenced two islands, one located approximately 120 stadia (almost 19 km) from an estuary; the second island located a complete day and night sailing journey with proper climate conditions. As the historian Aryan stated, “Alexander the Great ordered that the nearer island be named “Ikaros” (now Failaka) and the distant island as “Tylos” (now the Kingdom of Bahrain). Ikaros was described by the explorers as an island covered with rich vegetation and a shelter for numerous wild animals, considered sacred by the inhabitants who dedicate them to their local goddess.

After the collapse of the great empires in western Asia (Greek, Persian, Roman), the first centuries of the Christian era brought new settlers to Failaka. The island became a secure home for a Christian community, possibly Nestorian, until the 9th century CE. At Al- Qusur, in the centre of the island, archaeologists have uncovered two churches, built at an undetermined date, around which a large settlement grew. Its name may have changed again at that time, to Ramatha.