Kashmir’s geographical location partly explains its cultural history. It may be that its natural beauty and temperate climate are the reasons that Kashmiris have a strong tradition in the arts, literature, painting, drama, and dance. Its relative isolation, the security provided by the ring of mountains around it, and its distance from the heartland of Indian culture in the plains of North India, might explain the originality of Kashmiri thought. Its climate and the long winters may explain the Kashmiri fascination for philosophical speculation.

Kashmir is at the centre of the Puranic geography. In the Puranic conception, the earth's continents are arranged in the form of a lotus flower. Mt. Meru stands at the center of the world, the pericarp or seed-vessel of the flower, as it were, surrounded by circular ranges of mountains. Around Mt. Meru, like the petals of the lotus, are arranged four island continents (dvipas), aligned to the four points of the compass: Uttarakuru to the north, Ketumala to the west, Bhadrashva to the east, and Bharata or Jambudvipa to the south. The meeting point of the continents is the Meru mountain, which is the high Himalayan region around Kashmir, Uttarakuru represents Central Asia including Tocharia, Ketumala is Iran and lands beyond, Bhadrashva is China and the Far East. Kashmir’s centrality in this scheme was the recognition that it was a meeting ground for trade and ideas for the four main parts of the Old World. In fact it became more than a meeting ground, it was the land where an attempt was made to reconcile opposites by deeper analysis and bold conception.

Kashmir’s nearness to rich trade routes brought it considerable wealth and emboldened Kashmiris to take Sanskrit culture out of the country as missionaries. Kashmiris also became interpreters of the Indian civilization and they authored many fundamental synthesizing and expository works. Some of these works are anonymous encyclopedias, for many other works the author’s name is known but the details of the life and circumstances in Kashmir are hardly remembered.

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini (River of Kings), written in about 1150, provides a narrative of successive dynasties that ruled Kashmir. Kalhana claimed to have used eleven earlier works as well the Nilamata Purana. Of these earlier books only the Nilamata Purana survives. The narrative in the Rajatarangini becomes more than mere names with the accession of the Karkota dynasty in the early seventh century.

The political boundaries of Kashmir have on occasion extended much beyond the valley and the adjoining regions. According to Hiuen Tsang, the Chinese traveler, the adjacent territories to the west and south down to the plains were also under the direct control of the king of Kashmir. With Durlabhavardhana of the Karkota dynasty, the power of Kashmir extended to parts of Punjab and Afghanistan. It appears that during this period of Kashmiri expansion, the ruling elite, if not the general population, of Gilgit, Baltistan, and West Tibet spoke Kashmiri-related languages. Later, as Kashmir’s political power declined, these groups were displaced by Tibetan-speaking people.

In the eighth century, Lalitaditya (reigned 725-761), conquered most of north India, Central Asia and Tibet. His vision and exertions mark a new phase of Indian empire-building. Kashmir had become an important player in the rivalries amongst the various kingdoms of north India.

The jostling of the Kashmiri State within the circle of the north Indian powers led to an important political innovation. The important Vishnudharmottara Purana, believed to have been written in Kashmir of the Karkota kings, recommends innovations regarding the rajasuya and the ashvamedha sacrifices, of which the latter in its medieval interpretations was responsible for much warfare amongst kings. In the medieval times the horse was left free to roam for a year and the king’s soldiers tried to establish the rule of their king in all regions visited by the horse, leading to fighting. The Vishnudharmottara Purana replaced these ancient rites by the rajyabhisheka (royal consecration) and surapratishtha (the fixing of the divine abode) rites.

This essay presents an overview of the most important Kashmiri contributions to Indian culture, emphasizing some of the lesser known aspects of these contributions. Specifically, we consider the contributions to the arts, sciences, literature, and philosophy. Our historical assessment of Kashmiri culture is hampered by the nature of our records. The texts and objects of art do not always indicate their provenance and the connections with Kashmir emerge only from indirect evidence. We are on sure ground when we come to Buddhist sources, the texts of the Kashmir Shaivism, and the names mentioned in the Rajatarangini and other early narratives.

Early Period

During the Vedic period, Kashmir appears to be an important region because it appears that the Mujavant mountain, the region where Soma grew, was located there. It is possible that in the Vedic era a large part of the valley was still under a lake. Kalhana’s history begins with the Mahabharata War, but it is very hazy with regard to the events prior to the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka.

The great grammarian Panini lived in northwest Punjab not too far from Kashmir and the university at Taxila (Takshashila) was also close to the valley. At the time of Hiuen Tsang, Takshashila was a tributary to Kashmir. It is generally accepted that Patanjali, the great author of the Mahabhashya commentary on Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, was a Kashmiri, as were a host of other grammarians like Chandra. According to Bhartrihari and other early scholars, Patanjali also made contributions to Yoga (the yoga-sutras) and to Ayurveda. It is believed that Patanjali's mother was named Gorika and he was born in Gonarda. He was educated in Takshashila and he taught in Pataliputra. From the textual references in his works, it can be safely said that he belonged to 2nd century BC.

The Charaka Samhita of Ayurveda that has come down to us is due to the editing of Dridhabala from Kashmir, who also added seventeen chapters to the sixth section and the whole of the eighth section. Patanjali may have been involved in this editing process. But it is likely that the identity of the Kashmiris as a distinct group had not solidified in the Vedic period and to speak of ethnicity at that time is meaningless.

In any event, Kashmir of these early times was a part of the larger northwest Indian region of which Takshashila was a center of learning. The early levels of buildings in Takshashila have been traced to 800 BC. The first millennium BC was a period of great intellectual activity in this part of India and attitudes that later came to be termed Kashmiri were an important element of this activity. Amongst these attitudes was a characteristic approach to classification in the arts and the interest in grammar.

Panini’s grammar remains one of the greatest achievements of the human intellect. It described the grammar of the Sanskrit language by a system of 4,000 algebraic rules, a feat that has not been equaled for any other language to this day. It also set the tone for scientific studies in India with their emphasis on algorithmic explanations. Patanjali’s commentary on the Panini grammar was responsible for the exaltation of its reputation. It appears that Panini arose in the same intellectual climate that characterized Kashmir during its Classical period.

Drama and Music: The Natya Shastra

An early name seen as belonging to Kashmir is Bharata Muni of the Natyashastra. The indirect reasons for this identification are that the rasa idea of the Natyashastra was discussed by many scholars in Kashmir. Another reason is that the Natyashastra has a total of 36 chapters and it is suggested that this number may have been deliberately chosen to conform to the theory of 36 tattvas which is a part of the later Shaivite system of Kashmir. Many descriptions in this book seem especially true for Kashmir. The bhana, a one-actor play described by Bharata is still performed in Kashmir by groups called bhand pather (bhana patra, in Sanskrit).

All Indian classical danceforms are heavily influenced by the principles of Natyashastra

It should be mentioned here parenthetically that a few scholars take Bharata to be a Southerner. It is also interesting that there exist some very close connections between Kashmir and South India in the cultural tradition like the worship of Shiva, Pancharatra, Tantra, and the arts. Recently, when I pointed this out to Vasundhara Filliozat, the art historian who has worked on Karnataka, she said that the inscriptional evidence indicates a continuing movement of teachers from Kashmir to the South and that Kashmir is likely to have been the original source of many of the early Shaivite, Tantric, and Sthapatya Agamas.

Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra not only presents the language of creative expression, it is the world's first book on stagecraft. It is so comprehensive that it lists 108 different postures that can be combined to give the various movements of dance. Bharata's ideas are the key to proper understanding of Indian arts, music and sculpture. They provide an insight into how different Indian arts are expressions of a celebratory attitude to the universe. Manomohan Ghosh, the modern translator of the Natya Shastra, believes that it belongs to the 5th century BC. He bases his assessment on the archaic pre-Paninian features of the language and the fact that Bharata mentions the arthashastra of Brihaspati and not that of the 4th century BC Kautilya.

The term natya is synonymous with drama. According to Bharata, the natya was created by taking elements from each of the four Vedas: recitation (pathya) from the Rigveda, song or melody (gita) from the Samaveda, acting (abhinaya) from the Yajurveda, and sentiments (rasa) from the Atharvaveda. By this synthesis, the Natya Shastrabecame the fifth Veda, meant to take the spirit of the Vedic vision to the common man. Elsewhere, Bharata says: “The entire nature of human beings as connected with the experiences of happiness and misery, and joy and sorrow, when presented through the process of histrionics (abhinaya) is called natya.”

Five of the thirty-six chapters of the Natya Shastra are devoted to music. Bharata speaks of the 22 shrutis of the octave, the seven notes and the number of shrutis in each of them. He explains how the vina is to be tuned. He also describes the dhruvapada songs that were part of musical performances.

The concept of rasa, enduring sentiment, lies behind the aesthetics of the Natya Shastra. There are eight rasas: heroism, fury, wonder, love, mirth, compassion, disgust and terror. Bharata lists another 33 less permanent sentiments. The artist, through movement, voice, music or any other creative act, attempts to evoke them in the listener and the spectator. This evocation helps to plumb the depths of the soul, thereby facilitating self-knowledge.

The algorithmic approach to knowledge became the model for scientific theories in the Indic world, extending from India to the east and Southeast Asia. The ideas of the Natya Shastra were in consonance with this tradition and they provided an overarching comprehensiveness to sculpture, temple architecture, performance, dance and story-telling. But unlike other technical shastras that were written for the scholar, Bharata's work influenced millions directly. For these reasons alone, the Natya Shastra is one of the most important books ever written.

To appreciate the pervasive influence of the Natya Shastra, just consider music. The comprehensiveness of the Natya Shastra forged a tradition of tremendous pride and resilience that survived the westward movement of Indian musical imagination through the agency of itinerant musicians. Several thousand Indian musicians, of which Kashmiri musicians are likely to have been a part, were invited by the fifth century Persian king Behram Gaur. Turkish armies used Indians as professional musicians.

Bharata stresses the transformative power of creative art. He says, “It teaches duty to those who have no sense of duty, love to those who are eager for its fulfillment, and it chastises those who are ill-bred or unruly, promotes self-restraint in those who are disciplined, gives courage to cowards, energy to heroic persons, enlightens men of poor intellect and gives wisdom to the learned.”

Our life is spent learning one language or another. Words in themselves are not enough, we must learn the languages of relationships, ideas, music, games, business, power, and nature. There are some languages that one wishes did not exist, like that of evil. But evil, resulting from ignorance that makes one act like an animal, is a part of nature and it is best to recognize it so that one knows how to confront it. Creative art show us a way to transcend evil because of its ability to transform. This is why religious fanatics hate art.

Cosmology and Science: The Yoga Vasishtha

Another book from Kashmir which has had enduring influence over Indian thought is the Yoga Vasishtha (YV). Professing to be a book of instruction on the nature of consciousness, it has many fascinating passages on time, space, matter and cognition. They are significant not only in telling us about thinking in Kashmir, they summarize Indian ideas of physics, available to us through a variety of sources that are not widely known outside scholarly circles. Starting with a position that seeks to unify space, time, matter, and consciousness, an argument is made for relativity of space and time, cyclic and recursively defined universes, and a non-anthropocentric view.

Within the Indian tradition it is believed that reality transcends the separate categories of space, time, matter, and observation. In this function, called Brahman, inhere all categories including knowledge. The conditioned mind can, by “tuning” in to Brahman, obtain knowledge, although it can only be expressed in terms of the associations already experienced by the mind. In this tradition, scientific knowledge describes as much aspects of outer reality as the topography of the mindscape. Connections (bandhu) between the outer and the inner are assumed: we can comprehend reality only because we are already equipped to do so. In other words, innate, primitive, a priori ideas give rational organization to our fragmentary sensations.

The Yoga-Vasishtha (YV) is over 29,000 verses long, and it is traditionally attributed to Valmiki, author of the epic Ramayana, which is over two thousand years old. But scholars believe it was composed in the early centuries in Kashmir. The historian of philosophy Dasgupta dated it about the sixth century AD on the basis that one of its verses appears to be copied from one of Kalidasa’s plays, considering Kalidasa to have lived around the fifth century. But new theories support the view that the traditional date of Kalidasa is 50 BC. This means that the estimates regarding the age of YV are further muddled and it is possible that this text could be 2000 years old.

YV may be viewed as a book of philosophy or as a philosophical novel. It describes the instruction given by Vasishtha to Rama of the Ramayana. Its premise may be termed radical idealism and it is couched in a fashion that has many parallels with the notion of a participatory universe, where the actions of the conscious agents have a bearing on future evolution.

Its most interesting passages from the scientific point of view relate to the description of the nature of space, time, matter, and consciousness. It should be emphasized that the YV ideas do not stand in isolation. Similar ideas are to be found in the earlier Vedic books. At its deepest level the Vedic conception is to view reality in a unitary manner; at the next level one may speak of the dichotomy of mind and matter. Ideas similar to those found in YV are also encountered in the Puranic and Tantric literature. But the clarity and directness with which these ideas are described in YV is unique.

Roughly speaking, the Vedic system speaks of interconnectedness between the observer and the observed. The Vedic system of knowledge is based on a tripartite approach to the universe where connections exist in triples in categories of one group and across groups: sky, atmosphere, earth; object, medium, subject; future, present, past; and so on. Beyond the triples lies the transcendental ``fourth''. Three kinds of motion are alluded to in the Vedic books: these are the translational motion, sound, and light which are taken to be ``equivalent'' to earth, air, and sky. The fourth motion is assigned to consciousness; and this is considered to be infinite in speed. It is most interesting that the books in this Indian tradition speak about the relativity of time and space in a variety of ways. The Puranas speak of countless universes, time flowing at different rates for different observers and so on.

Universes defined recursively are described in the famous episode of Indra and the ants in Brahmavaivarta Purana, the Mahabharata, and elsewhere. These flights of imagination are to be traced to more than a straightforward generalization of the motions of the planets into a cyclic universe. They must be viewed in the background of an amazingly sophisticated tradition of cognitive and analytical thought. The YV argues that whereas physical nature is taken to be analyzable it is defined only in relation to observers. Consciousness is considered a more fundamental category. But YV is not written as a systematic text. Its narrative jumps between various levels: psychological, biological, and physical, as is traditional in Indian texts. Not surprisingly, given the Vedic emphasis on rta, YV accepts the idea that laws are intrinsic to the universe. But do these laws remain constant? There is some suggestion that the laws of nature in an unfolding universe also evolve.

According to YV, new information does not emerge out of the inanimate world but it is a result of the exchange between mind and matter. It accepts consciousness as a kind of fundamental field that pervades the whole universe. One might speculate that the parallels between YV and some recent ideas of physics are a result of the degree of abstraction that is common to both; or one might assert that the parallels are a reflection of the inherent structure of the mind.

It appears that the Kashmiri understanding of physics was informed not only by astronomy and terrestrial experiments but also by speculative thought and by meditation on the nature of consciousness. Unfettered by either geocentric or anthropocentric views, this understanding unified the physics of the small with that of the large within a framework that included metaphysics. YV ideas do not represent a break with the older Vedic thought; they are an amplification of the basic themes informed by advances in the unfolding understanding of the astronomy and other physical sciences.

This was a framework consisting of innumerable worlds (solar systems), where time and space were continuous, matter was atomic, and consciousness was atomic, yet derived from an all-pervasive unity. The material atoms were defined first by their subtle form, called tanmatra, which was visualized as a potential, from which emerged the gross atoms. A central notion in this system was that all descriptions of reality are circumscribed by paradox. The universe was seen as dynamic, going through ceaseless change.

Tantra: Shaivism and Vaishnavism

The Kashmiri approach to the world is uniquely positive. There is a celebration of nature and beauty for the objective world is also a representation of Brahman (Lord). This approach is part of the Kashmiri tantric thought in both its strands of Shaivism and Vaishnavism. The Tantras stress the equivalence of the universe and the body and look for divinity within the person.

Although the Vaishnavite Panchratra now survives only in South India, the earliest teachers looked to Kashmir as the seat of learning and spiritual culture. The Pancharatra ontology and ritual are described in the Kashmirian Vishnudharmotta Purana. According to this theology, the king was enjoined to build a temple for the rites to be performed to celebrate his victory over his opponents. These rites marked his union with Vishnu. This represented an important milestone in the conceptualization of the role of the king in Indic thought.

According to Kalhana, the worship of Shiva in Kashmir dates prior to the Mauryan King Ashoka. The Tantras were enshrined in texts known as the Agamas, most of which are now lost. The pinnacle of the Tantric Shaiva tradition is the Trika system. The great spiritual master and scholar Abhinavagupta (c. 975-1025) describes the goal of the Shaiva discipline is to find freedom. In this freedom, the adept becomes one with Shiva, transcending all oppositions and polarities. The jivanamukta (the liberated person) experiences the freedom of Shiva in a blissful and unitary vision of the all-pervasiveness of the Absolute.

Two very interesting ideas in Kashmir Shaivism are that of recognition and of vibration. In the philosophy of Recognition, it is proposed that the ultimate experience of enlightenment consists of a profound and irreversible recognition that one’s own true identity is Shiva himself. The doctrine of Vibration speaks of the importance of experiencing spanda, the vibration or pulse of consciousness. Every activity in the universe, as well as sensations, cognitions, emotions ebbs and flows as part of the universal rhythm of the one reality, Shiva.

Contributions to Buddhism

Kashmir became an early centre of Buddhist scholarship. In the first century, the Kushan emperor Kanishka chose Kashmir as the venue of a major Buddhist Council comprising of over 500 monks and scholars. At this meeting the previously not-codified portions of Buddha’s discourses and the theoretical portions of the canon were codified. The entire canon (the Tripitaka) was inscribed on copper plates and deposited in a stupa. The Buddhist schools of Sarvastivada, Mahayana, Madhyamika, and Yogachara were all well developed in Kashmir. It also produced famous Buddhist logicians such as Dinnaga, Dharmakirti, Vinitadeva, and Dharmottara.

Kashmiris were tireless in the spread of Buddhist ideas to Central Asia. Attracted by Kashmir’s reputation as a great centre of scholarship, many Buddhists came from distant lands to learn Sanskrit and train as translators and teachers. Amongst these was Kumarajiva (344-413), the son of the Kuchean princess who, when his mother became a nun, followed her into monastic life at the age of seven. He came to Kashmir in his youth to learn the Mahayana scriptures from Bandhudatta. Later he became a specialist in Madhyamika philosophy. In 383, Chinese forces seized Kucha and carried Kumarajiva off to China. From 401 he was at the Ch'in court in the capital Chang'an (the modern Xi'an), where he taught and translated Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. More than 100 translations are attributed to him. His works include some of the most important titles in the Chinese Buddhist canon. Kumarajiva's career had an epoch-making influence on Chinese Buddhist thought, not only because he translated important texts that were previously unknown, but also because he did much to clarify Buddhist terminology and philosophical concepts. He and his disciples established the Chinese branch of the Madhyamika, known as the San-lun, or "Three Treatises school."

Kumarajiva’s contemporary, the Kashmiri Buddhabhadra also went to China to translate the Buddhist texts. The Kashmiri Buddhasena translated a major Yogachara text into Chinese. Hiuen Tsang, the famous Chinese pilgrim, came to Kashmir in 631, staying for two years. Many famous Buddhist Tantric teachers were associated with Kashmir. According to some Tibetan sources, Naropa and Padmasambhava (who introduced Tantric Buddhism into Tibet) were Kashmiris. The Tibetan script is derived from the Kashmiri Sharada script, It was brought into Tibet by Thonmi-Sambhota, who was sent to Kashmir during the reign of Duralabhavardhana (seventh century) to study with Devatitasimha.

Architecture and Painting

The uniqueness of the Kashmiri idiom in artistic expression has been recognized by historians. The ancient temple ruins in Kashmir are some of the oldest standing temples in India today (7th – 9th Centuries) and would have been among the most magnificent temples ever made in India. The sculptures found here are significant and exquisite.

The Martanda temple, built by Lalitaditya, is one of the earliest and yet largest stone temples to have been built in Kashmir. The temple is rectangular in plan, consisting of a mandapa and a shrine. Two other shrines flank the mandapa. It is enclosed by a vast courtyard by a peristyle wall with 84 secondary shrines in it. The columns of the peristyle are fluted. Each of the 84 niches originally contained an image of a form of Surya. The number 84, as 21x4, appears to have been derived from the numerical association of 21 with the sun.

Lalitaditya also built a huge chaitya in the town of Parihasapura which housed an enormous Buddha. Only the plinth of this huge monument survives, although one of the paintings at Alchi is believed to be its representation. There was also an enormous stupa in Parihasapura built by Lalitaditya’s minister Chankuna, which may have even been larger than the chaitya. The Parihasapura monuments became models for Buddhist architecture from Afghanistan to Japan.

Ruins of Avantipura (Creative Commons License)

The Pandrethan temple, as well as the Avantipur complex, provide us further examples of the excellence of Kashmiri architecture and art. Kashmiri ivories and metal images are also outstanding and are generally considered to be among the best anywhere in the world.

Kashmir also had a flourishing tradition of painting, which must have been used to decorate the temples walls. The earliest surviving examples of these paintings come from Gilgit and date from about 8th century. Representing a highly developed style, these paintings must be seen as belonging to a very old tradition. Kashmiri craftsmen were long famed for their work and their hand can be seen in many works of art in Central Asia and Tibet.

Although references to paintings in ancient Kashmiri literature are scattered, and because all records of painting in the Valley were destroyed after the advent of Islam, it is possible to piece together this tradition from the paintings that are preserved in the Buddhist temples of Ladakh and Tibet. The Tibetan scholar Rinchen Sangpo (950 - 1055) claimed to have visited Kashmir thrice to obtain the services of 75 Kashmiri craftsmen, painters and teachers to build and decorate one hundred and eight temples in Western Tibet. According to the 16th century Tibetan scholar Lama Taranath, author of a history of Buddhism in India, there existed in the 9th century India four principal school of art: eastern, middle country, Marwar, and the Kashmiri.

Boddhisattva Padmapani at Ajanta

The discovery of Gilgit manuscript paintings has deepened our understanding of Kashmiri painting. Although usually assigned to the Kashmir school of the 9th century, on stylistic grounds they may date even earlier as their nearest parallels are found in the 8th century stone sculpture of Pandrethan. Painted figures of Boddhisattva Padmapani from Gilgit demonstrates the mingling of the Gandharan and the Gupta Indian conventions with local elements. The faces are typical Gandharan while the iconography and spirit is purely Indian. After Lalitaditya, Kashmiri style appears to have changed somewhat and it endured till 10-11th century. This phase is the most developed stage of Kashmiri art with its fame spreading into the remote Himalayas.

The 9th century complex of Avantipura built by King Avantivarman (855-883 AD) is an amalgam of various earlier prevalent forms of India and regions beyond. The best example of this style is found in the bronzes dated to 9th to 11th century cast by Kashmiri craftsmen for Tibetan patrons. The style of such bronzes presents a remarkable affinity to the wall-paintings dating to 10-11th century decorated in the Buddhist temples of Western Tibet.

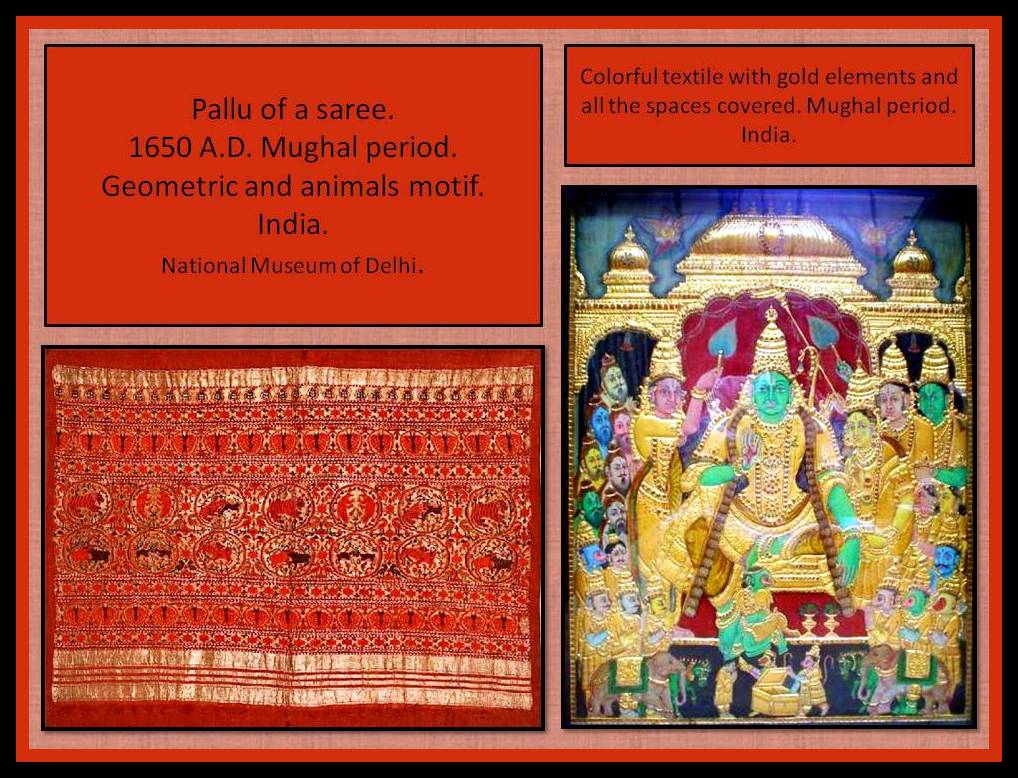

The wall paintings of Mang nang and manuscript painting of Thaling discovered in Western Tibet are generally accepted to have been created by Kashmiri painters. Stylistically, they are a pictorial translation of contemporary Kashmiri bronzes. In the treatment of costumes and ornaments, the artists have meticulously executed the finest details of diaphanous and embroidered garments and intricate design. These wall paintings present a final stage of progression of the Kashmiri style which reminds something related to the distant Ajanta.

One of the best sites to see the Kashmiri painting style is in the five temples comprising the dharma-mandala at Alchi in Ladakh, which escaped destruction that other Ladakhi temples suffered at the hands of a Ladakhi king who embraced Islam. The earliest of these buildings is the ‘Du-khang where one can see astonishingly well preserved mandalas that document the Kashmiri Buddhist pantheon as well as the Buddhist representation of the Hindu pantheon.

The Sum-tsek, a three-level building next to the ‘Du-khang presents the native architectural tradition, characterized by piled-up rock walls faced with mud plaster, decorated with delicate wood carvings of the Kashmiri style. Triangular forms are a part of the pillars and other architectural elements in a style that corresponds to the motifs found on the stone monuments of Kashmir. The plan of the building contains three extensions on the east, north, and west where gigantic two-storied images of Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya and Manjushri to remove impurities in speech, mind, and body were situated. Elsewhere in the building is a most interesting painting of Prajnaparamita, identified by the book and the rosary she holds. A tall structure depicted on her sides appears to be the famous chaitya built by Lalitaditya at Parihasapura.

According to the historian of art Susan Huntington,

“Kashmir served as a source of imagery and influence for the northern and eastern movements of Buddhist art. The Yunkang caves in China, the wall paintings from several sites in Inner Asia, especially Qizil and Tun-huang, the paintings from the cache at Tun-huang, and some iconographic manuscripts from Japan, for example, should be evaluated with Kashmir in mind as a possible source. A full understanding of the transmission of Buddhist art through Asia is dependent on developing a greater knowledge of Kashmiri art.”

Dance and Music

Kalhana, while speaking of Lalitaditya, narrates a charming story of how the king discovered the ruins of an old temple where he had a new temple built. While exercising his horse, Lalitaditya saw two beautiful , gazelle-eyed girls sing and dance every day at the same time. Upon questioning they told him that they were dancing girls who danced at the spot on the instructions of their mothers. Lalitaditya had the place dug up and he found two decayed temples with closed doors. Inside were images of Rama and Lakshmana. Clearly the tradition of temple dancing was an old one.

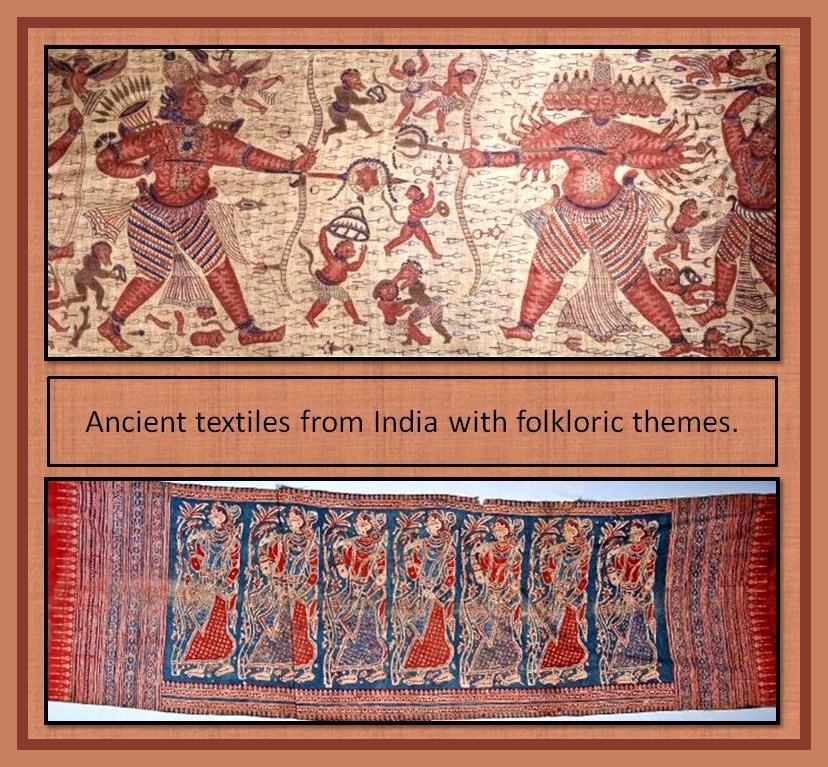

The paintings in Kashmiri style bring to us a clear idea of the temple dances which prevailed in Kashmir at the time when these paintings were made (10th–11th Centuries). Indian classical dance in its different forms was born out of the tradition of dancing before the Lord in the temples. This representation of the dance forms enriches our knowledge of the culture of Kashmir and its close integrity to the rest of India. Kalhana mentions many kings who were interested in dance and music.

The only extant complete commentary on the Natya Shastra is the one by Abhinavagupta. The massive thirteenth-century text Sangitaratnakara ("Ocean of Music and Dance"), composed by the Kashmiri theorist Sharngadeva, is one of the most important landmarks in Indian music history. It was composed in south-central India shortly before the conquest of this region by the Muslims and thus gives an account of Indian music before the full impact of Muslim influence. A large part of this work is devoted to marga, that is, the ancient music that includes the system of jatis and grama-ragas. Sharngadeva mentions a total of 264 ragas.

Literature

We return to rasa, mentioned by Bharata Muni as the essence of artistic expression. In the poetic tradition, it is mentioned by Bhatta Lollata of the 9th century, the oldest commentator on the Natya Shastra whose views have come down to us. Other authors such as Shankuka, Bhatta Nayaka, Bhatta Udbhatta, Rudratta, Vamana also wrote on rasa. Kshemendra, the polymath, had his own theory of poetics. Abhinavagupta speaks of nine rasas, where rasaof peace represents the addition to the eight enumerated by Bharata.

The 9th century scholar Anandavardhana wrote the Dhvanyaloka, the “Light of Suggestion”, which is a world-class masterpiece of aesthetic theory. He rejected the earlier theories of alankara and guna by Bhamaha and Dandin according to which ornamental qualities and figures of speech distinguished poetry from ordinary speech. Anandavardhana said that the difference was a quality called dhvani which communicates meaning by suggestion indirectly. Anandavardhana was a member of the court of the king Avantivarman.

Anandavardhana was the first to note that rasa cannot be communicated directly. If one were to say that “so-and-so and his wife are very much in love,” we fail to express the nature of the love. This can be done only by dhvani, or suggestion. Abhinavagupta, who lived about a hundred years after Anandavardhana, added important elements to the dhvani theory. His famous commentary on the Dhvanyaloka is called the Lochana.

The Western classical tradition of criticism has nothing equivalent to the concepts of rasa and dhvani. These ideas provide unique insights into Indic literature and they can also be useful in the appreciation of non-Indic literatures. Abhinavagupta, wrote on philosophy, poetry, tantra, as well as aesthetics. His book Tantraloka (Light of the Tantras) is one of the most important on the subject. In all, he wrote more than sixty works. Kshemendra was a philosopher, poet, and a pupil of Abhinavagupta. Among his books is the Brihatkathamanjari which is a summary of Gunadhya’s Brihatkatha in 7,500 stanzas. Somadeva’s Kathasaritasagara is another version of Gunadhya’s Brihatkatha. Somadeva’s collection of stories has influenced the birth of fiction elsewhere. These stories were written for the queen Suryamati, the wife of king Ananta (1028-1063). The number of stanzas, not counting the prose passages, exceeds 22,000.

Sharda Peeth in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (Creative Commons License)

The classic arts and the sciences of Kashmir came to an abrupt end when Islam became the dominant force in Kashmir in the fourteenth century. Sculpture, painting, dance, music could no longer be practiced. After the political situation had become stable, the subsequent centuries saw emphasis on devotion and its expression through the Kashmiri language as in the poetry of Lalleshvari. The creative urges at the folk level found expression in the works of the craftsmen of wood and textiles.

But Kashmiri ideas lived on through the arts that transformed expression in Central and East Asia, and through Tantra and aesthetics that shaped attitudes in the rest of India. Many Kashmiris emigrated to other parts; the musicologist Sharngadeva and the poet Bilhana being just two such people. Although Kashmir had sunk to a state of misery, outsiders continued to pay homage to the memory of Kashmir as the land of learning, and Sharada, the presiding goddess of Kashmir became synonymous with Sarasvati.

Banner Image: Pahalgam Valley (Courtesy: Ankur P | Flickr)

http://www.pragyata.com/mag/the-wonder-that-was-kashmir-217

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.

![Proving the form and function of Indus Script Hypertexts: Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP) of ca. 3300 BCE rebus Meluhha spoken metaphor is the cipher by [Kalyanaraman, S]](http://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51zReNe0QdL.jpg)

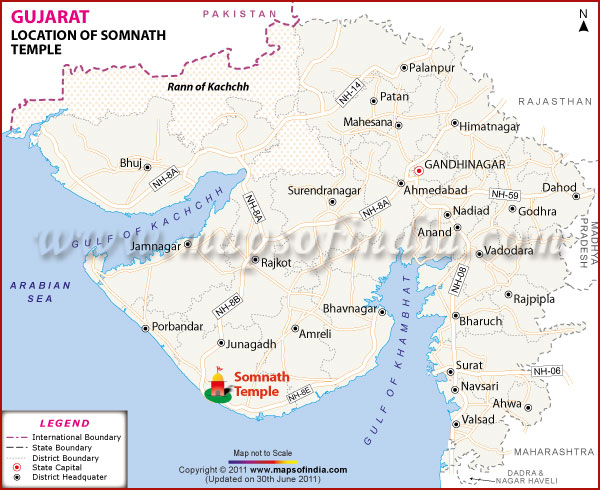

Gates of Somnath

Gates of Somnath

.jpg)