Inception of both the Religions

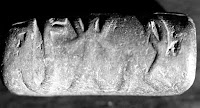

![]()

Coins issued by Hindu Kushan Dynasty's kings of ancient Afghanistan. These coins display Mazdaen-worshiped deities, because the Hindu kings were tolerant of social diversity and wanted to promote harmony between them. Even in Dunhang city of the ancient Tarim Basin one can see Zoroastrian and Hindu figures.

[1]Both

Zoroastrianism and Hinduism have similar

origins, pay homage to the same spiritual seers, venerate the same gods and even have the same verses throughout the early scriptures. Mazdaen scholars Zubin Mehta and Gulshan Majeed

[2] had noted a similarity of Kashmiri customs with Zoroastrian ones. In the modern era, some Mazdaen clerics had visited Kashmir, who include Azar Kaiwan

[3] and his dozen disciples

[4], and Mobad Zulfiqar Ardastani or Sasani

[5] who compiled the Dabistan-e Mazahib.

Zarathustra was definitely a Kashmiri Brahman from India as he was an

Atharvan[6], who called himself a zaotar

[7], manthran

[8] and

datta.

[9] He was referred to as an erishi

[10] and ratu

[11].

[12] He also wore the

sacred thread and

dressed like a traditional Kashmiri Pandit, compiled Gāthās containing Vedic verses,

worshiped Varuna (Ahura Mazda) and venerated other holy Vedic

Asuras. He

lived as an ascetic in a cave[13]for some time and also had other traits similar to that of an Indian Brahman, not to mention other customs similar to those of Kashmiri Hindus. The geographical description of his birthplace in the Mazdaen scriptures match Kashmir's

Diti (Daitya) and Indus (Veh) rivers and Urni Jabbar (Jabr) Mountain within Baramulla district. In addition, the descriptions of neighboring regions adjacent to Airyanem Vaeja, such as Ataro-Patakan, Kohistan, Kangdez and Panjistan match those of places surrounding Kashmir. Ancient scholars, such as Clement of Alexandria and Ammianus Marcellinus, connecting Zarathustra to Brahmans can definitely be seen, and even in modern times Godfrey Higgins had called him "

Zerdusht the Brahmin[14]."

Similarities

Zoroastrianism originated in India

Zarathustra's name

"Zarathustra became a generic name for 'great prophet' so several Zarathustras arose in the period 6000 to 600 BC the Avesta Y.XIX.18 named a hierarchy of five leaders, the supreme being called Zarathustrotema." - Duncan K. Malloch

[15]

Just as the pseudonyms Gautama Buddha, Vardhman Mahavira, and Guru Nanak are reflective of the sages' names and titles, so too is the case of Zarathustra Spitama. 'Zarathustra' is a name that

relates his devotion to Ahura Mazda.

| There are the master of the house, the lord of the borough, the lord of the town, the lord of the province, and the Zarathustra (the high-priest) as the fifth. | |

—Avesta Yasna 19.18.50 [16] |

There was "the Armenian Zoroaster, grandson of Zostrianus" ("Zostriani nepos"), who was the Pamphylian friend of Cyrus the Great. There was also a "Zoroaster" of Babylon whom Pythagoras had written of meeting. Further, the Changragach-Nameh and the Zarathusht-Nameh were written by Zarathusht Behrairi Pazdu, while Zaratusht Bahram was an important Mobed.

Zarathustra's surname Spitama comes from his ancestor Spiti. This name traces its roots to the Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh, just south to Kashmir. This is also supported by the fact that Zarathustra had taken solitude at age 15 to Mt. Ushidaran which the Greater Bundahishn identifies as Mt. Kāf.

[17] Today is a village in the Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh named Kāf.

Spitama itself has the Vedic Sanskrit attribute of containing 'tama', like the gotra patronyms of Gautama and Girghtama(s), as well as the titles of hiranya-vasi-mat-tama, rathi-tama, ratna-dha-tama, and sasvat-tama.

Background of erishis

Athravans were Atharvans from India

- See also: Veneration of Shukra Acharya in Mazdayasna, Shukra Acharya

"These were probably at first identical with the Vedic Atharvans (fire-priests), as indeed Zoroastrianism is merely an advanced stage of Brahmanism."[24] - Chambers' Encyclopedia

![]()

Although some western depictions falsely show him as European-looking with brown hair and eyes, and white skin, the Bahram Yasht declares Athravans are black-haired

[25].

![]()

A mural of Zarathustra in a Tehran temple. Unlike his western depictions, here his skin is depicted dark brown like many Indians.

Zarathustra was of the Athravan (

Atharvan) priestly caste. The Avesta declares that Zarathustra was an Athravan.

| Hail to us! for he is born, the Athravan Spitama Zarathustra. Zarathustra will offer us sacrifices with libations and bundles of baresma with libations and bundles of baresma and there will be the good Law of the worshipers of Mazda come and spread through all the seven Karshvares of the earth. | |

|

The Atharvans are as ancient as the Rig Veda. It mentions that Brahmā taught the knowledge of Brahman to his eldest son Atharvan.

[27] Further, the Atharvans are associated with fire symbolizing it to be as sacred to them as it was to the later Athravans. Bharadvaja says to

Agni that Atharvan has churned Agni out from the lotus, from the head of everything.

[28]Vitahavya also says that the Atharvans have brought Agni from the "

dark-ones" (i.e., nights.)

[29]Angras are Angirasas

Further, Zarathustra in his Gāthās alludes to "

old revelations"

[30], and praises the Saoshyants

[31] (fire-priests), and even exhorts his party of attendees to praise the Angras

[32]. Hindu scriptures know the Angirasas (descendants of Rṣi Angiras) as the composers of the

Atharva Veda, or as the "Atharvangirasa" and the Veda is also known as the Angiras Veda. (Angras are in no way connected to Angra Mainyu, the opposer of Ahura Mazda whose name means

Dark Spirit.) Hence, those Angras mentioned by Zarathustra are also Vedic rṣis. He is referred to by some rṣis in the Rig Veda as their "

father".

[33] Angira is a son of

Varuna, as are Bhargava and Vasiśṭha. Angirasas are sacerdotal families with ceremonial practices in the Atharva Veda.

[34] Their connection to the sacred fire is such that the Rig Veda also names Agni as Angiras

[35], and that the sons of Angiras were born of Agni

[36]. In the RV, Angirasas were called "

Sons of Heaven, Heroes of the Asura."

[37]The fact that Bhargavas are, like their subgroup Angirasas and the Athravans, also descendants of Vasiśṭha is established in Puranas.

[38] Hence, Kava Uṣan (Shukra Acharya the Bhargava) is venerated and included as one of the holiest sages in Mazdayasna because he was also from Vahiśta (Vasiśṭha.)

[39]Sraosha of the Avesta is

Bṛhasa (Bṛhaspati) of the Vedas who was the son of Angiras

[40], so Sraosha is also of the category of Angras mentioned in the Avesta.

Zarathustra was of Vasiśṭha Gotra

The Denkard scripture specifically mentions that Zarathustra was a descendant of the law-giving immortals (Amesha Spentas, to which the Vahiśtas belong), as well as of "King Jam"

[41] Mazdaen scriptures mention Vahiśta (Vasiśṭha) within the Avesta, wherein he is an Amesha Spenta

[42] mentioned as Asha Vahiśta. In Mazdayasna, Asha Vahiśta is a divine lawgiver

[43] and guardian of the Asha.

[44]Vasiśṭha is a law-giver sage in many instances within the scriptures and is even quoted by other rṣis, such as Bhṛgu and

Manu, when they prescribe societal laws.

[45] Asha Vahiśta is also closely associated with the sacred fire in several Avestan passages

[46][47], just as Vasiśṭha is.

The Atharvans are descended from Vasiśṭha Rṣi.

[48] Vasiśṭha's dedication to Atharvan is demonstrated in the Rig Veda wherein after being filled with anger, he calms himself by reading the Atharva Mantra.

[49]Vedic scholar Mallinatha writes in his commentary of the Kiratarjunya that the

Śāstras declare that the mantras of Atharva Rṣi are preserved by Vaśiśṭha.

[50] Just as there are several Vaśiśṭhas

[51] within the community, the Avesta acknowledges that there are several Vahiśtas,

[52] and refers to them as the "

Lords of Asha." Even in the Vahistoistri Gāthā,

[53] Francois De Blois notices that it consists of verses with a variable number of unstressed syllables.

[54]Avestan as a dialect of Sanskrit

"Slowly and gradually, it dawned upon them that the language of the

Gathaand Zendavesta has very great kinship with the Sanskrta language; when the grammar of Panini, Katyayana, and Patanjali was applied then the Gatha and Zendavesta came to be understood by the westerners. The lesson from this amazing fact is clear that once the Iranians of the

Gatha and

Zendavesta and the Indo-Aryans of the Vedas formed one single race, speaking language akin to Samskrta." - Yaqub Masih

[55]

It is known that both Vedic Sanskrit and the Zhand Avestan languages were very close. In fact, some scholars have even stated that "

the Parsi was derived from the language of the Brahmans"

[56] like various Indian dialects. This view point was supported by "

Zend language was at least a dialect of the Sanskrit."

[57] Max Muller, William Jones

[58] and Nathaniel Brassey Halhed

[59] put forward this viewpoint.

Erskine Perry also was in the view that Avestan was a dialect of Sanskrit and was exported to ancient Persia from India but was never spoken there and his reasoning for this is that of the seven languages of ancient Persia mentioned in the Farhang-i-Jehangiri, none of them is referring Avestan language. Another scholar perpetuating the viewpoint of Avestan being a Sanskritic/Prakritic dialect was John Leyden.

[60]- List of some Sanskrit and Avestan words

![]()

Zarathustra portrayed on a pillar of the Shakta-Vaishnava Birla Mandir, Jaipur, Rajasthan. Hinduism's pluralistic tradition recognizes the pious sage as a saint in the list of the world's spiritual gurus.

![]()

Zarathustra portrayed on a mural of the Shree Saibaba Satsang Mandal, Surat, Gujarat. He is shown next to Jalaram (left) and Vivekananda.

|

| gold | hiranya | zaranya |

| army | séna | haena |

| spear | rsti | arsti |

| sovereignty | ksatra | khshathra |

| lord | ásura | ahura |

| sacrifice | yajñá | yasna |

| sacrificing priest | hótar | zaotar |

| worship | stotra | zaothra |

| sacrificing drink | sóma | haoma |

| member of religious community | aryamán | airyaman |

| god | deva | deva |

| demon | rákshas | rakhshas[61] |

| cosmic order | rta | arstat/arta |

- List of some Sanskrit and Avestan names for gods

|

| Apām Napāt | Apam Napat | Yazata | Son of water, a god |

| Aramati | Armaiti | Amesha Spenta | Archangel of immortality |

| Baga | Bagha | Yazata | A sun god |

| Ila | Iza | Yazata | Goddess of sacrifice |

| Manu | Manu(shchihr) | Ancestor | Son of Vivanhvant |

| Marut | Marut | Yazata | Cloud god |

| Mitra | Mithra | Yazata | A sun god |

| Nābhānedista | Nabanazdishta | Ancestor | Name of Manu |

| Narasansa | Nairyosangha | Yazata | A fire god |

| Surya | Hvara | Yazata | A sun god |

| Trita | Thrita | Yazata | God of healing |

| Twastra | Thworesta | Yazata | Artificer of the gods |

| Usha | Ushah | Yazata | The Goddess Dawn |

| Varuna | Varuna | Ahura Mazda (one of his 101 names[62]) | The Wise Lord, creator of all |

| Vayu | Vayu | Yazata | A wind god |

| Vivasvant | Vivanhvant | Yazata | A sun god |

| Vritrahan | Verethragna | Yazata | Slayer of Verethra |

| Vasiśṭha | Vahiśta | Amesha Spenta | Archangel and lawgiver to humanity |

| Yama | Yima | King | A pious king of Airyanem Vaeja |

Apart from the gods that are common to both

Zoroastrianism and Hinduism, names of some other

Hindu gods are carried by even modern day Persian speakers. For example, the names '

Śiva' (

Charming) and variations of '

Rāma' (

Black)

[63] are used by Iranic speakers, such as Persians and Pashtuns.

King Ram is also added in names such as 'Shahram' (

King Rām) and 'Vahram'/Bahram' (

Virtuous Rām), which was the other name of Verethragna mentioned in the Bahram Yasht of the Avesta. The Sassanian kings took the Vahram title, such "Vahram I" (ab. AD 273-276.)

[64] Toponyms as well include 'Ram'/'Raman' in their syntax, such as Ramsar in Iran.

- Daēvā does not mean Deva

Whereas the root of the Avestan word 'daēvā' is "

daē" meaning

god, of 'deva' it is "

div", which means

light. Zarathustra wrote in his Gāthās, "

daēnāe paouruyae dae ahura!"

[65] Hence, the word for religion in Avestan is daēnā.

[66]That deva carries positive connotations is seen in

Gāthā 17.4 Yasna 53.4 wherein Ahura Mazda is said to be a "devaav ahuraaha."

As Airyanem Vaeja is in Kashmiri, the Avestan and Kashmiri vocabulary are similar. Dai is still used by Kashmiris to refer as god.

Many Avestan verses are from Vedas

The

Rig Veda is believed to have been the oldest scripture in the world. In it are verses that are identical to ones within the Zhand Avesta, except the dialect of the Avesta is in Avestan. Ahura Mazda, whom the Mazdaens

worship as the Supreme Lord is the

Avestan equivalent to

Vedic Sanskrit's Asura Medhira or Asura Mada. These terms mean "Wise Lord" and in the

Rig Veda this phrase appears in a few places, in one verse being "

kṣayannasmabhyamasura".

| With bending down, oblations, sacrifices, O Varuna, we deprecate thine anger:Wise Asura, thou King of wide dominion, loosen the bonds of sins by us committed. [67] | |

—Rig Veda 24.14 |

There are several passages in the

Vedas (especially the

Atharva Veda) and Avesta that are identical, with the only difference that they are in the different dialects of Avestan and Vedic Sanskrit.

There are two sets of Mazdaen scriptures; the Zhand Avesta

[68] and the Khorda-Avesta.

[69] The Zhand contains 3 further sets of writings, known as the Gāthās

[70] compiled by Zarathustra, and the Vendidad, and Vispered. (Not surprisingly, Hindu scriptures also have collections known as Gāthas, such as the

Vasant Gātha and

Theragātha.) The Khorda contains short prayers known as

Yashts. They are written in a metre much like the

Vedas. Normally they contain 15 syllables known in Sanskrit as Gayatri

asuri) like hymns of the Rig Veda, or Ushnih

asuri such as in the Gāthā Vohu Khshathrem

[71] or of 11 syllables in the Pankti asuri form, such as in the Ustavaiti Gātha.

Some scholars also note that there is a connection between Bhargava Rṣi and Zoroastrianism, as the Atharva Veda portion composed by him is known as Bhargava Upastha and the latter word is the Sanskrit version of the term 'Avesta'.

[72]"The Avesta is nearer the Veda than the Veda to its own epic Sanskrit." - Dr. L. H. Mills

- Some identical verses from Vedas and the Avesta

|

Rig Veda (10.87.21) /

Zhand Avesta (Gāthā 17.4 Yasna 53.4) | mahaantaa mitraa varunaa samraajaa devaav asuraaha sakhe sakhaayaam ajaro jarimne agne martyaan amartyas tvam nah | mahaantaa mitraa varunaa devaav ahuraaha sakhe ya fedroi vidaat patyaye caa vaastrevyo at caa khatratave ashaauno ashavavyo | O Ahura Mazda, you appear as the father, the ruler, the friend, the worker and as knowledge. It is your immense mercy that has given a mortal the fortune to stay at your feet. |

|---|

Atharva Veda 7.66 /

Zhand Avesta (Prishni, Chapter 8, Gāthā 12) | yadi antareekshe yadi vaate aasa yadi vriksheshu yadi bolapashu yad ashravan pashava ud-yamaanam tad braahmanam punar asmaan upaitu | yadi antareekshe yadi vaate aasa yadi vriksheshu yadi bolapashu yad ashravan pashava ud-yamaanam tad braahmanam punar asmaan upaitu | O Lord! Whether you be in the sky or in the wind, in the forest or in the waves. No matter where you are, come to us once. All living beings restlessly await the sound of your footsteps. |

|---|

Rig Veda /

Zhand Avesta (Gāthā 17.4, Yasna 29) | majadaah sakritva smarishthah | madaatta sakhaare marharinto | Only that supreme being is worthy of worship. |

|---|

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta (Yasna 31.8) | vishva duraksho jinavati | vispa drakshu janaiti | All (every) evil spirit is slain. |

|---|

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta | vishva duraksho nashyati | vispa drakshu naashaiti | All (every) evil spirit goes away. |

|---|

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta | yadaa shrinoti etaam vaacaam | yathaa hanoti aisham vaacam | When he hears these words. |

|---|

Why Zarathustra's teachings are called Zhand Avesta

The Avesta is also known as the Zhand Avesta. Zhand is the Avestan equivalent of Chhand.

| O Kshatriya, the verses that were recited by Atharvan to a conclave of great sages, in days of old, are known by the name of Chhandas. They are not be regarded as acquainted with the Chhandas who have only read through the Vedas, without having attained to the knowledge of Him who is known through the Vedas. The Chhandas, O best of men, become the means of obtaining Brahm(Moksha) independently and without the necessity of anything foreign. | |

—Mahabharata Udyoga Parva Chapter 43:4[73] |

The word Avesta comes from Sanskrit 'Abhyasta', which means Repeated. Hence, the Avesta (Abhyasta) is basically a repetition of Zarathustra's teachings.

Zarathustra was born in Kashmir

![]()

Zarathustra is always shown wearing a dhoti, (Indian-fashioned garment), unlike the Balkhans to whom he preaches.

The birthplace of Zarathustra has been a subject of dispute ever since the Greek, Latin and later the Muslim writers came to know of him and his teachings. Cephalion, Eusebius, and Justin believed it was either in Balkh (Greek: Bactria) or the eastern Iranian Plateau, while Pliny and Origen thought Media or the western Iranian Plateau, and Muslim authors like Shahrastani and al-Tuabari believed it was western Iran.

[74]While Zarathustra's place of birth has been postulated in various places even in modern times, including within areas not historically included by authors, such as in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, a few scholars have believed that he was born in Kashmir. Shrikant G. Talageri

[75] and T. Lloyd Stanley

[76] were proponents of this Kashmiri Airyanem Vaeja viewpoint. Mazdaen scriptures

[77] mention repeatedly that Zarathustra was born in Airyanem Vaeja, also known as

Airyanam Dakhyunam. However, Zarathustra moved from there to Balkh, where he was given sanctuary by its king and he had become a royal sage. The Mazdaen scriptures further say that many other people of Airyanem Vaeja had moved out with the dramatic climate change whereby snow and cold weather became much more frequent. Zarathustra was regarded as a pious Godman for the Balkhan administrators of his time and India was recognized as a center of spiritual and scientific wisdom. This is why Mazdaean scriptures show that King Vishtaspa's court was already familiar with the Indian Brahman adviser Changragach who was teacher to minister Jamaspa, even before Zarathustra's arrival to Balkh. The Brahman Byas was also welcome in King Vishtaspa's court and met and had become a disciple of Zarathustra. King Vishtaspa (Greek: Hystaspes) was the father of King Darius I of the Balkh Kingdom and he had studied

astronomy amongst the Brahmans of India.

[78]There are similarities noticed by scholars such as Subhash Kak and Zubin Mehta which are described by them between Mazdaen practices of Kashmiri Hindus. These include the sacred thread for

women (called

aetapan in Kashmiri) and the sacred shirt (

sadr.) The festival of Nuvruz

[79] in commemoration of King Yima is known as Navreh in Kashmir which is celebrated by Kashmiri Hindus. Furthermore, the folklore of Kashmir too has many tales where devas

[80] are antagonists to both

devas and asuras. As the title Zarathustra has many variations, such as 'Zartust' and 'Zardost', the Sanskrit equivalent of his title is 'Haritustra Svitma'. The 'p' in 'Spitama' corresponds to a 'v' in Sanskrit just as Avestan 'Pourusarpa' is 'Purusarva' is Sanskrit. Whereas the consonant 's' of many Sanskrit words becomes 'h' in Avestan, 'Svitama' maintains its letter because it is followed by a 'v', just as how the 's' in Sanskrit '

asva' (

horse) becomes 'aspa' (i.e., 'Dhruwaspa' means

She who possesses strong horses, and

animals within nameswere more common, such as Yuvanasva and Vindhyasva.) As 'Spitama' means

white, the Sanskrit word for the color-based name is 'Svitama'. Svita is a metaphorical characteristic associated with purity and normally associated with Brahmans in the Vedas. For example, the Rig Veda

[81] describes the Vasiśṭha ṛṣis as 'svityam' (

white), 'svityanco' (

dressed in white)

[82] and

white-robed. Zarathustra dresses in white as well Mazdaen priests also dress up in white. The connection between Vasiśṭha ṛṣi with Atharvan Rṣi is a very close one.

Identification of Avestan sacred places in Kashmir

- See also: King Yama's Kingdom was in Kashmir, Rig Vedic rivers, India is the homeland of Indo-Europeans

Kashmir itself has taken on various endonyms and exonymns, which can make pinpointing whether an author is talking about the region. In this case, the Mazdaen scriptures refer to it as Airyanem Vaeja and Anu-Varshte. In addition to these, the region has been called Kashmar, Kashir, Kasherumana, Katche-yul, Kasperia, and Kipin, and it together with Balawaristan is known as

Hari-varṣa, Naishadha-varṣa, Uttara-Patha, and Deva-Kuru. It has symbolic and historic association with rishis, and has been known as Rishivaer/Rishi-wara (

Land of Rishis.) Even Persian literature has mentioned the words Reshi, Reshout, and Rea-Shivat when speaking about Kashmir.

[83] Firdaus (

Paradise) is another Persian word that has been used to describe Kashmir. The word Airyanem within the phrase Airyanem Vaeja means

Of the Aryans. Jain mantras use the term in the salutations, such as "Namo Airiyanam" in the Namokar Mantra, and "Om Hreem Namo Airiyanam" as an astrological mantra for Jupiter.

- Why Airyanem Vaeja is also called Anu-Varshte

The Avesta mentions 'Anu-varshte daēnāyai'

[84], meaning "

religion of Anu-land." This prayer requests the help of Ardvisura to help Zarathustra able to convince King Vishtaspa to accept the 'religion of Anu-Varshte.' The Anu tribe, also known as Anavas in many Hindu scriptures, were based in Kashmir. There's even a village called Ainu Brai after them within Pahalgam tehsil of Anantanag in Kashmir. That they later annexed nearby lands, including Balkh in Afghanistan, is evident from scriptures such as that of Panani's that tells us of Anava settlements.

In the Anava lineage, 7th in descent from Anu were brothers Usinara and Titikshu. The territories gained by the Anavas was split by these brothers wherein Usinara had grasped Kashmir and the Punjab

[85] while Titikshu gained rulership over eastern territories of Anga (Bihar), Vanga (Bengal), Suhma, Pundra, and Kalinga (Orissa.)

Because Kashmir has prehistorically been the Anava stronghold, even during the

Dasarajna War as the Rig Veda mentions, it is acknowledged as such both in Hindu scriptures such as the Atharva Veda

[86] and in the Mazdaen Avesta.

One of the reasons why historically Balkh and some other regions of modern Afghanistan were Indianized (and hence, referred to as Ariana) is because the Anavas also held areas of Afghanistan under their suzerainty. In Vrtlikara

[87],

Sage Panini (from Afghanistan himself) mentions that there are 2 Anava settlements of the Usinara called Ahvajala and Saudarsana. Even scholarly Chinese visitors to ancient India, Fa Hien and Yuan Chwang describe the story of a certain King Usinara told at Udyana (modern Swat Valley where people are mostly ethnically Afghans) that sacrificed his life to save that of a dove's.

To little surprise the Kurma Purana

[88] mentions Anava being 1 of the 7 sons (

Saprtarṣis) of Vasiśṭha, meaning that Vasiśṭha had married within the royal family. Within the same

Manavatara era another son of Vasiśṭha was Shukra, meaning that Vasiśṭha had likely married multiple women.

- Jabr Mountain is Urni Jabbar Mountain

![]()

Zarathustra's birthplace Urni Jabbar (Avesta's Jabr Mountain) and his city of residence Raihan Bag (Avesta's Rai.)

Zarathustra was said to have been born in the village of Raji

[89] by the Dareja

[90] River near the Jabr Mountain

[91]. In Vendidad 1.16 where the city of Ragha is referred to the Pahlevi commentators add that it is in Ātaro-Pātakān. In Kashmir, there is a village of similar name, Renji in Sopore district

[92]. There are other villages and towns bearing 'Rai' in their names. These are Raipura, Raika Gura, Raika Labanah, Raika Mahuva, Rainawari, and Rai'than. Kashmir bears the villages Raj Pora Thandakasi

[93] Dareja is also mentioned to be where Zarathustra's father lived

[94], hence, Zarathustra lived there too. Today in Kashmir there are the 2 rivers Darga Burzil and Darga Rattu that merge to form the larger Astore River.

[95]- Amui (Amar) is Amartnath in Kashmir

| The sorcerer (Zandak), who is full of death, founded a city of Amui (Amar), and Zardusht, descendant of Spitama, was of that place. | |

—Satroiha-i Airan 59 |

This verse is saying that Zarathustra was of this place, meaning he likely spent a significant portion of his life there. This is also the opinion Carl Bezold and Louis Herbert Gray.

Amarnath pilgrimage is Anantanag district, bordering Baramulla district, where Zarathustra was born.

- Rai is Raihan Bag in Kashmir

| Zarathustra was of that place (Rai.) | |

|

This village is very close to the Urni Jabbar mountain, it is in Uri tehsil and, like the mountain, is in the Badgam district.

- Daitya River is the Jhelum

![]()

Arapath (Diti) rises in Hairbal Ki Galli and flows southward until it merges with Bring, which in turn merges with Lower Jhelum near Danter village.

[97]Scriptures mention the original homeland of the religion and of Zarathustra, but due to placename changes, the exact location has been hard to pinpoint.

Daityas are also mentioned (as are

Danavas) in ancient Mazdaen texts as good beings. It is believed that the homeland of the Aryans is located by the

Daitya River

[98] as said in this

Avesta quote, "

Airyanem Vaejo vanghuydo daityayo", which Darmesteter translates as "

the Airyana Vaejo, by the good (vanghuhi) river Daitya."

[99] In later scriptures, the river is known as 'Veh Daiti' wherein the Veh refers to the Daiti being its tributary. Veh in the Bundahishn is mentioned as the Indus River. Bundahishn mentions that Veh is also called Mehra by Indians, and surely enough Mehra is a town along the Indus. Veyhind (Udabhānḍapur, modern Hund) is also a town reflecting Indus' Veh-name. Further, Vahika was the name of a kingdom around the Indus and its meaning is

Land of the River.[100] (Here was Arattadesa or Panchanada.) Kashmir has a river named

Ditiwhich is said to have been an incarnation of

Diti, mother of the

Daityas.

[101] Daityas have been mentioned in Hindu

Epicsas staunch Asuras. This river is also popularly called as Chandravati, Arapath or Harshapatha.

[102] The Arapath Valley begins where the Arapath (Diti) stream stems out of Jhelum.

[103] Because the Diti becomes the Jhelum at their stem, the Mazdaen scriptures just call the entire Jhelum as Daitya River. They also refer to it as the Veh Daiti because the Jhelum itself merges into the Indus, which the Bundahishn calls 'Veh'. (The entire Jhelum is certainly known by many names in India.

[104].) Just as the Bundahishn calls the Daitya "

the chief of all streams"

[105], scholars note the Jhelum has more streams than any other Indus tributary.

Zarathustra used to bathe in the Dareja affluent of the Daitya. In the same way, Hindus are encouraged to bathe in it among rivers of Kashmir.

| After that on the 14th of the dark-half of the month, one should take bath, before sun-rise, in the cool water of the Vitasta or the Visoka or the Candravati or the Harsapatha or the Trikoti or the Sindhu or the holy Kanakavahini or any other holy river or the water-reservoirs and the lakes. | |

|

King Vishtaspa used to perform sacrifices along the Dareja. In the same way, Hindus are encouraged to perform execute the Rajasuya ceremony along the Diti.

| By bathing in Harsapatha, one is honoured in the world of Sakra and by bathing in Candravati one gets the merit of (giving) ten cows. Holy is the river Harsapatha and so also is Candravati. The wise say that there accrues (the merit of the performance of) Rajasuya at the confluence of these two. | |

|

- Dareja is an affluent of Daitya River

![]()

The (Dareja) Lower Jhelum River coming out of Wulur Lake.

The Dareja is the lower Jhelum from which stretches from Hairbal Ki Galli to Muzaffarabad to join the other part of the Jhelum that stretches Mangla Reservoir to Muzaffarabad. Today this stream is known as the Lower Jhelum.

| For the occurrence of the seventh questioning, which is Amurdad's, the spirits of plants have come out with Zaratust to a conference on the river Dareja's high ground on the bank of the waters of the Daiti. | |

|

| Of those eighteen principal rivers, distinct from the Arag river (Amu Darya) and Vêh river (Indus), and the other rivers which flow out from them, I will mention the more famous: the Arag river, the Vêh river, the Diglat river (Yarkhun) they call also again the Vêh river, the Frât river, the Dâîtîk river (Jhelum), the Dargâm river, the Zôndak river, the Harôî river (Harirud), the Marv river, the Hêtûmand river (Helmand), the Akhôshir river, the Nâvadâ river, the Zîsmand river, the Khvegand river, the Balkh river (Balkhab), the Mehrvâ river they call the Hendvâ river (Indus), the Spêd river, the Rad river which they call also the Koir, the Khvaraê river which they call also the Mesrgân, the Harhaz river, the Teremet river, the Khvanaîdis river, the Dâraga (Jhelum's stream Lower Jhelum) river, the Kâsîk river, the Sêd ('shining') river Pêdâ-meyan or Katru-meyan river of Mokarstân. | |

|

- Bundahishn's Kohistan is Kohistan of Karakoram Range

![]()

Gurjistan is 1 of the ethnic regions of Kashmir, and is mentioned in Mazdaen scriptures as possessing the Daitya River. Here, Gurji is the predominant language.

| The Daitik river (Datya) rises in Airan-vej and flows through Kohistan. | |

—Bundahishn 20.13 |

Kohistan is also referred in the Pazhand transcription of the Bundahishn as Gurjistan.

[108] The Gurjistan that is referred to is the Gurez Valley in Kashmir. Gurez is acknowledged by V. R. Raghavan as to have come from 'Gurj' and 'Gurjur'.

[109]Gopat, also known as Gopistan is another name for Kohistan.

| The land of Gopat has a common border with Eran Vez on the banks of the river Datya. | |

|

Subdastan is also a demonym of Kohistan.

| The river Datya comes from Eran Vez and goes to Subdastan. | |

—Bundahishn |

- Bundahishn's Panjistan is Panjistan of Punjab

![]()

Haro River has 2 streams. Zend is its northern branch.

Panjistan is mentioned as possessing the Zend River. The name in present-day is used to refer to a region of northeastern Punjab region. Even the language spoken there is called Panjistani.

The Pahlavi word 'Zend' (referring to a city, not the Zhand Avesta) is the translation of local 'Jand' within the Punjab. There are cities and towns throughout the region named Jand. Hence, the river is called Jand (Zend.)

| The Zend River passes through the mountains of Panjistan, and flows away to the Haro River. | |

—Bundahishn 20.15 |

- Hara Mountains are Himalayas and the river Aravand is Sarasvati

Mountains across the northwestern Himalayas contain 'Hara' within their names, such as Haramukh Mountain

[111] and Haramosh Mountain nearby in Gilgitstan. Hara is the shortened form of the mountain range's name Hara-Berezaiti.

Hara's most sacred peaks are known as Us-Hindava (Pahlevi: Usindam) and the Hukairya (Pahlevi: Hugar.) In the Avesta, Us-Hindava Mountain (which means

Upper Indian Mountain) is also spoken of as Usindam and Usinda Mountain and it receives water from a "

golden channel" from Mt. Hukairya (

Of good deeds[112].)

Hari is the name for a series of mountains as well as villages

[113] that have "Hara" as their names. Today Hara Parvat is revered by Hindus as a sacred mountain.

Further, the Ardvi Sura River that the Avesta writes about, is the

Sarasvati River of the Rig Veda is said to flow from Hara into the Vourukasha Sea

[114] (Indian Ocean.) Sarasvati flowed from Hardikun Glacier (West Harhwal Bandarpanch Masif) and took its coarse into the Indian Ocean. To further, that Avestan Ar was in Kashmir is that it mentions god Sraoesa (Avestan name of Bṛhaspati) living in the Hukairya mountains. There is a

praśasti dedicated to Sarasvati inscribed in Madhya Pradesh, which states that Sarasvati lived in heaven together with Bṛhaspati.

[115]Also, the Avesta speaks of the Aravand River, which is another name for Ardvi Sura, and it is the Avestan translated name of

Amaravati River, Sarasvati's other name.

- Mount Kāf is Mount Meru

Mt. Kāf is the same mountain that

Zarathustra is believed in legends to have gone into recluse. In Mazdaen sources it is usually called Ushidarena. In Hindu sources a Kashmiri mountain called Ushiraka (also referred to as 'Darva' and 'Abhisara') is mentioned as a place where people are sent for solitude. It is also mentioned in Buddhist texts as Ushiraddhaja and Ushira-giri, and as Ushinara-giri in the Kathasaritsagara.

Alberuni mentioned that this is the same mountain that Indians call Lokaloka.

[116]The modern K2 mountain is

Mt. Meru. It is in the boundary between the Karakoram and the Himalayas. The Karakoram (

Black Mountains) are also known as Krishnagiri (

Black Mountains) in Sanskrit. As a lot of places around Kashmir and Balawaristan contain 'giri' or 'gir' within their names.

Scholars like Charles Hamilton Smith and Samuel Kneeland had identified that the Kāf mountain or mountains are just north of the Indus River.

[117] The K2 is just north of Indus River.

- Mount Cinvat is Mount Cṛṅgvāt

A mountain mentioned in Mazdaen scriptures is Cinvat. In Hindu texts there is a mountain associated with Meru because the latter's waters flow through the Cṛṅgvāt (also known as Tri-Cṛṅga.)

The meaning of the Sanskrit word 'Cṛṅgvāt' is

summit peak, and 'Cṛṅgi' is used in general for the placenames of peaks of the Himalayas

[118] and of Sringaverapura (modern Allahabad), Srisringa, Chirtasringa, and Hiranyasringa.

- More identifiers of Kashmir

The Bundahishn divides Kashmir into 2; Inner and Outer. Inner it calls Kashmir-e andaron. Other scholars, such as Dimashql, have noted this distinction as well when writing of the region. Geographer Al-Mas'udi wrote that Inner Kashmir was founded by Kai Kaus. Historically in India Kashmir has been written of as two; Kamraz (Kramarajya) and Maraz (Madvarajya.)

"If India were the original home of Indo-Europeans, it must also be the birth place of Zarathushtra. If the Zoroastrians had migrated out of India, they would have carried memories of the geography they left behind. Avestan literature is not familiar with the Indus. In fact, it believes Indus and Oxus to be the same. In contrast, Avesta itself refers to the features in Afghanistan." - Rajesh Kochhar

[119]

Rajesh Kochhar's statement that Zarathustra would have had to have been born in India for it to have been the Indo-European homeland holds true, because the Avesta indeed mentions toponyms of features in northern India, mainly from Kashmir. The reason why most places in the Avesta are of Afghanistan is because Zarathustra, who was not from the Balkh Kingdom and had migrated there as most scholars agree, had only composed the Gāthās of the Avesta, whereas the rest of it was composed by his converts in Balkh. It is believed that the time gap between the Gāthās and the rest of the Avesta are centuries.

[120] Scholars believe that this can be seen from "

the poor grammatical condition of the language" of the Vendidad portion of the Avesta.

[121] Kochhar also says Mazdaens who migrated would have to carry the memories of India with them, because the first Mazdaens were Zarathustra's family including his cousin Maidhyomaongha, also known as Maidhyoimah or Medhyomah, brother-in-laws Frashaoshtra and Jamaspa,

[122] wife Hvovi, his daughters named Freni, Thriti and Pourushista, and his three sons which migrated with him, Zarathustra was the only compiler of the Avesta out of them. Apart from Zarathustra and his family, the first community of adherents was founded by King Vishtaspa

[123]Interestingly enough, the king converts

[124] after recognizing Zarathustra's holyness, when the prophet healed his paralyzed horse

[125] just like the Sant Kabir and

Sant Namdev [126] brought back a cow to life to earn the faith of kings. So because Kochhar asserts that India must be the Indo-European homeland by meeting his criteria, then India is Airyanem Vaeja.

India in general is overlooked by modern scholars who study the Mazdaen scriptures. Of importance is Mithra, who is associated with the Indian Subcontinent. His dominion is geographically described in the Mihir-Yasht as extending from eastern India and the Hapta Hindava to western India and from the Steppes of the north to the Indian Ocean. The Avesta mentions Four Waters, which are four rivers of paradise. Kashmiri poets have written of "

four rivers of paradise" in their works. The Four Waters of paradise according to the Avesta are:

[127]- The Azi

- The Agenayo

- The Dregudaya

- The Mataras

The water of these has a trait that they contain honey or honey-sweet water: "

Two crossing canals that joined in a pond and which symbolized the four rivers of Paradise where milk, honey, wine and water flow."

[128] This same bed of four rivers is the one referred to in the Rig Veda. The Veda mentions waters filled with honey-sweet water as the greatest work of nature: "

The noblest, the most wonderful work of this magnificent one (Indra) is that of having filled the bed of the four rivers with water as sweet as honey."

[129] The river of Kashmir which has four streams is the Jhelum and its four branches are Arapath (the Diti River), Vishau, Rimiyara and Lidar.

[130] As Airyanem Vaeja is said to have been the birthplace of the first set of humans, the Kashmiris too state the human origin story about Kashmir.

"Aryana Vaeja has been placed in Media by inhabitants of Persia and Media. But this is only a transfer...which has nothing primitive and has only originated in consequence of the real site being forgotten."

[131]

Zoroastrianism's scholars have written about the origins of the Mazdaens from India. Max Muller had said that, "

The Zoroastrians were a colony from northern India."

[132] M. Michel Break wrote, "

The Zoroastrians were a colony from Northern India."

[133]Also identified in the Mazdaen scriptures are people such as Yima (

Yama) and Manushchihr (Manu),

[134]who have traditionally been strongly associated with Kashmir. Manushchihr in the Avestan Yasht

[135] is mentioned as "

the holy Manushchihr, the son of Airyu."

| Zardasht is said to have planted, under auspicious circumstances, two cypress-tress, one in Kashmir and the other in Farumad-tus, and the Majusi (Magi) believe that he brought the cypress from paradise when he planted it in those places. | |

—Farhang-i-Jehangiri |

Both the Farhang-i-Jehangiri and the Shahnameh mention that Zarathustra had planted a cypress tree at a place named Kashmar. This place in the prior text is named also as Kashmir. The composers of the Rehbar-i-Din-i-Zarthoshti (Dastur Erachjee Sorabjee Meherji Rana) and Dabistan (Mohsan Fani), believed this to be the Kashmir in India. Though the Kashmar/Kashmir in the story is actually a town in Khorasan, one can see that the etymological derivation of 'Kashmar' is from the more ancient region of Indian Kashmir. It's quite possible that the seeds to grow the tree came from Kashmir. Certainly, cypress tress exist in Kashmir, and the local species is known as Cupressus cashmeriana.

- Zarathustra learning from and preaching to other Vedic scholars

Ancient Greek scholars, such as Clement of Alexandria and Ammianus Marcellinus

[136], had written that Zoroaster had studied with the Brahmans of India. We know from Mazdaen literature that in his youth, Zarathustra's preceptor's name is Burzin Kuru(s), and the Kurus were a dynasty that had then dominated in parts of North India and in Afghanistan. Kashmir of course, is historically known as a part of Deva-Kuru. Further, even today there is the Burzahom Neolithic site next to Baramulla district in Kashmir, and the Draga Burzil stream in Kashmir, only further showing that the name Burzin has a connection to Kashmir. Ammianus had written that the Magi derived some of their most secret doctrines from the "Indian Brachmans" (i.e., Brahmans.)

[137] Arabian writers have given a lot of information concerning the learning which Zoroaster acquired from the Indian Brahmans.

[138] Ammianus also states in his 23rd Book of History that Prince Gushtasp (King Vishtasta's brother) went deep into the secluded areas of northern India and having reached a forest for retreat of the most exalted Brahmans, he learned spiritual knowledge from the Brahmans there and then returned back to his domain to preach this newly acquired wisdom to the Magi.

[139] Par Thomas Maurice believed and wrote that Zarathustra had studied with Brahmans in India.

[140] Kashmiri Brahmans are known synonymously as Kashmiri Pandits or simply as 'Pandits' (

Scholars) and Anquetil du Perron believes that the Mazdaen scripture the Dhup Nihang mentions Mazdaen Pandits. The 8th century CE scripture refers to three Dasturs called 'Pandits' whose names were Bio Pandit, Djsul Pandit and Schobul Pandit.

[141] Their names appear in the prayers of that scripture.

[142] Interestingly enough, the word 'Dastur' is used in Kashmiri to mean

custom.

[143]Furthermore, Ibn al-Athir too and written that Zarathustra had been in India at one point.

[144]According to the

Canda's Persian text, the Changragach Nameh, an Indian Brahman was called to King Gushtasp's palace to discuss with Zarathustra the Mazdaen religion. The Brahman after his discussion had became a preacher of the religion and went back to India where he established followers and

temples.

[145] Changragacha's name bares similarity to a placename, 'Chandrabhāga'. Another known Brahman that was a disciple of Zarathustra was a sage from India named Byas (

in the lineage of Vyas)

[146], and likely Nāidyāongha Gautama (a sage in the lineage of Nodhasa

Gautama.) According to the

Bhaviṣya Purāṇa, the Magi had first settled on the Chandrabhāga.

[147] This account also coincides with Timur's finding "fire-worshipers" in Punjab. Further, Aristoboulos, when visiting Taxila,

[148] had stated that the dead were "

thrown out to be devoured by vultures."

[149] This practice is still observed in parts of western Tibet.

[150] Further, within Taxila had existed a great Jandial fire temple mentioned by Philostratus.

[151] In the 1079 CE century, Sultan Ibrahim the Ghaznavid had attacked a community of Mazdaens at Dehra (probably Dehra Dun.) Then from Timur's invasion of India, among his captives of both Mazdaens and Hindus from Tughlikpur, some were Mazdaens who offered fierce resistance. In 1504 CE, Bedauni mentioned that Sultan Sikander destroyed fire-altars.

[152]- Relationship between the Magi and Indian Hindu Priests

The Magi being Athravans were accepted as Brahmans and they settled in Punjab first when they were brought by

Samba (son of

Kṛṣṇa) and they spread from there to other parts of the Indian Subcontinent including Karnataka and Nepal which are also known as the Magacharya or Maga Brahman today.

- Where nations speak Avestan-like languages today

As Zarathustra had spoken Avestan, the language likely would have been spoken in a place where it was popular. Today, Kashmiri (Koshuri) is closest language to Sanskrit and hence to Avestan that is spoken by a linguistic group very similar to Rig Vedic Sanskrit. In addition, languages very close to Sanskrit which are also spoken in regions adjacent to Kashmir, showing only that the Sanskritic-Avestan homeland would at least include Kashmir. The neighboring nations which speak Sanskrit-like languages are the Kalashi, Shina, Gawar Bati, Dameli, Pashayi, Kohistani, Palula and Nuristani. Just as in Avestan, 'zarat' means

golden and 'ustra' refers not only to

camel[153] but also to wild animals such as cows and sheep in general

[154], as well as buffalos. 'Ustra' is used a few times in the

Atharva Veda), displaying the point that camels and buffalos were very familiar and common amongst where the Veda's compilers and where Zarathustra lived.

- Why Zarathustra left for Balkh

![]()

Map from Aelianus'

De natura animalium.

"That this Magian language was Zend is surely no forced hypothesis, since from those Brahmins seated in Bactria, we long after find Zoroaster bringing the same religious system and employing their Zend terms for it: a fact which no one can deny." - John George Cochrane

[155]

![]()

Map of the ancient Silk Route, which connected major cities and peoples of the ancient world.

In ancient time, Indian Brahmans had a great amount of influence over the

kingdoms adjacent to India or ones that extended from India to other places like Gandhara, Kakeya, and Kamboja. The fact that Athravans are the chief priests of Mazdaean in Afghanistan implies that Brahmans were already established in the region before Zarathustra's arrival there. In the

Vedic Era, King Atyarāti Jānaṃtapi conquered Uttara-Kuru (Afghanistan), thus bringing more Indian influence there. In the 3rd century BCE it was Asoka who had it under his dominion, and in the 8th century CE, it was Kashmiri king Lalitaditya Muktapida that had suzerainty over it. Balkh was known to have a Brahmans within the court of its king as well. Historically in India, Brahmans and other spiritual teachers have sought royal patronage to institutionally aid their religions such as in preaching beliefs to society and building temples. They would become rajyagurus (

royal teachers) or rajpurohits (

royal sacerdotal priests.) Zarathustra had become the chief spiritual adviser of the Balkhan court and his family members who were the first Mazdaens and also had similar positions within the court. Ancient Greek historian Aelianus in

De natura animalium,

[156] also mention that there were "Indian Arianians" and there is some suggestion that control of Ariana fluctuated between Indian and Arian Arianians. This infers that Indians in Ariana had political influences.

"A Rishi went to another country, to try and get his name famous there as a Rishi, but he got less celebrated than before (in his own country.) O Rishi, you left your home without a cause."

[157] - A Kashmiri Proverb

Kashmir being

Land of Rishis was abundant in rishis and it was normal for a monarch of ancient Balkh and other regions of Afghanistan to have Brahman teachers or ministers from India. For example, Nagasena had become the preceptor of the Balkhan King Menander, while Aśvaghośa of Balkhan King Kaniṣka

[158]who after his conversation held the Fourth Buddhist Council in Kashmir. Buddhayasas was a Kashmiri and had become the preceptor of Dharmagupta the king of Kashgar in 5th century CE. Gunavarman was a prince of Kashmir but was missionary for much of his life and became the royal adviser to the kings of East China, Java, and Sri Lanka in the 4th century CE. Bilhana was a royal sage of Panchal's King Madanabhirama in the 9th century CE. Even the Hindu Shahi Dynasty was established in the 9th century CE by the Turki Shahi Dynasty's Brahman minister Kallar. Kashmir was influential to both Indian and adjacent regions.

[159] In ancient history, Kashmir has been part of various

kingdoms that had included regions of Afghanistan. Even in the

Buddha's time, Gandhara was a Mahajanapada

[160] and in many periods of history, Kashmir was a part of the Gandharan Kingdom.

The presence of Indian Brahmans in various places, including neighboring ones, such as Gandhara and Balkh, was recorded in ancient times; Edict 13 of the 14 'Rock Edicts of King

Asoka' reads, "

There is no country, except among the Greeks, where these two groups, Brahmans and ascetics are not found and there is no country where people are not devoted to one or another religion..." Along the ancient Silk Route the Kashmiri gateway is at Kunjerab Pass and the Balkhan gateways on the pathway are Balkh and Shahrisabz.

Identification of other places in India

- Ātaro-Pātakān of the Avesta is not the Azerbaijan of Caucasus

Ātaro-Pātakān means Keeper of the Fire, which Sanskrit scriptures have used as 'Pāthaka Pitta'. Pāthakām is Sanskrit has meant to be a canton wherein spefically priests live.

Ātaro-Pātakān is in Dardistan and Swat. It is known for having the Asnavand Mountain and the city of Rak from where Zarathustra's mother was from. In modern Gilgitstan exists the Rakaposh Range where bears the title

Rak. The Avestan Vendidad

[161], it is Rak, whereas in Pahlevi scriptures it's Rag or Arak.

Arrian

[162], Strabo

[163], Pliny

[164], and Justin had stated that Atropatene in Media was named after its Satrap Atropatos declared independence after Alexander's death. He ruled the region under Alexander of Macedon from 328-327 BCE.

Because the Avesta predates Satrap Atropatos, the region of Atropatene is not the Avestan Ātaro-Pātakān (Protector of the Fire.) The Avestan Ātaro-Pātakān is in Persian known by 'Adar-bigan'. Hence, when the kingdom of lower Media took on the name Atropatene, it's Persian-equivalent name also began being used, and in the predominant Turkic language there it became known as Azerbaijan.

That Ātaro-Pātakān borders Airyanem Vaeja is seen in multiple sources, including the Bundahishn.

[165] | Zarathustra's father was of the region Adarbaijan; his mother whose name was Dughdo came from the city of Rai. | |

—Shaharastani |

- Aredvisur (Sataves) River is Sutlej

| And Sataves itself is a gulf (var) and side arm of the wide-formed ocean, for it drives back the impurity and turbidness which come from the salt sea, when they are continually going into the wide-formed ocean, with a might high wind, while that which is clear through purity goes into the Aredvisur sources of the wide-formed ocean. | |

|

Sataves' fluvial properties are also elaborated when Bundahishn and Vendidad Fargard

[167] state that Sataves controls the tides of Vouru-Kasha.

Just as how the Daiti being a tributary of the Indus is called Veh-Daiti, so too is the Aredvisur called the Veh-Aredvisur as the Sutlej is also an Indus tributary.

- Gaokerna is Gokarna

Mazdaean scriptures mention the Gaokerna tree of immortality, which is the same as the Hindu Gokarna.

There are said to be 2 Gokarna places; A northern and a southern.

The Varaha Purana refers to Gokarna, as a region where the shrine of Lord Gokarna was installed at the confluence of the Sarasvati and the Yamuna.

- Kangdez is Gangdise (beside Kashmir)

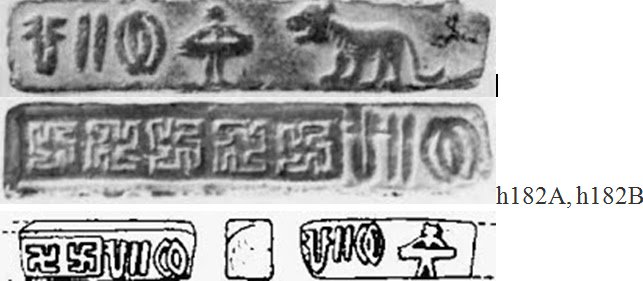

![]()

Detailed map of Tibet showing the mountainous Gangdise region and Mt. Lionbo Kangri A.K.A. Kangdez.

From the geography of Mazdaen scriptures it is easy to determine the location of Airyanem Vaeja in Kashmir because the regions around Airyanem Vaeja are mentioned too. The part of Tibetan Plateau west of the Indus River and Brahmaputra is even today called Gangdise. Mazdaen scriptures and the Shahnameh mention Kangdez.

In the Dadestan-i-Menog-i-Khrad

[168], the location of Kangdez is described as "

Kangdez is entrusted with the eastern quarter, near to Satavayes on the frontier of Airan-vego." Since Kangdez is the Gangdise region, this excerpt also supports Kashmir being Airyanem Vaeja.

Turkish historian Al-Biruni writes that he cannot locate Kangdez and that both Yamakoti and Tara are cities there. Yamakoti is also mentioned in the

Srimad Bhagavatam.

| It is said that Bhadrasva-varṣa extends from the city of Yamakoti up to the Malyavat Mountain. | |

—Srimad Bhagavatam |

The prominent mountain associated with this continent is Malyavat Mountain. It is the modern-day Muztag (7,282m) because the Mahabharata identifies Meru as being between the Malyavat and Gandhamadana.

[169]Apart from the Mt. Meru (Mazdaen Hara), Mt. Kailash is also revered in Mazdayasna as "Kangri". It is the abode of Peshotan (Chitro-maino), son of King Vishtaspa, and Khwarsheed-chihr (Khursheed-chehr), son of Zarathushtra, who will gather their righteous army there before the final battle against Ahriman and his creatures, according to the Bundahishn

[170], Denkard

[171], Zand-i-Wahman Yasn

[172].

Kangdez means "Fortress of Kang." In Ferdowsi's epic Shahnameh, Kangdez is named as Gangdez.

Kangdez's name is related to Kangha mentioned in the Avestan Yasht 5.54, the Aban (Ardvisur) Yasht. Antar Kanga is part of a list of mountains in Yasht 19.4. Antar Kanga is the chief mountain on which Kangdez bases its name, and is the largest mountain in the Gangdise, Mt. Kailash.

- Kangdez is Rasātāla

Just as Vasuki is mentioned as the ruler of

Rasātāla, the children of Vaesaka are mentioned in the Shahnameh as rulers of Kangdez. Just as Vasuki is of a serpent tribe, Vaesakas are written of as worshiping serpents.

| To her did Yoista, one of the Fryanas, offer up a sacrifice with a hundred horses, a thousand oxen, ten thousand lambs on the Pedvaepa of the Rangha. | |

—Aban Yasht 20.81 |

Pedvaepa river, an affluent

[173] of the Ranhā is the Pedak-miyan of the Bundahishn.

| The Pedak-miyan, which is the river Katru-miyan, is that which is in Kangdez. | |

—Bundahishn 20.31 |

- Ranhā is Rasā

- See also: Areas of Asura control

The Avesta mentions Ranhā (Sanskrit: '

Rasā', another name for Rasātāla), which is the "

sixteenth of the best lands created by Ahura Mazda." This land is based around the sources of the Ranhā River which is the Rig Vedic Rasā River. This river is identified with the modern-day

Brahmaputra River because the scriptural traits of the Rasā mentioned align with those of the Brahmaputra. Rasātāla, being populated by many

Daityas (i.e., Ahuras) would be of significance to Mazdaens and it always appears on the lists of 7 main abodes of the Asuras. Here a major battle between Asura and

Deva took place, the battle of

Hiranyakṣa and

Varāhā.

Two Avestan Fragards mention that Ranhā is the largest river that they know. This is true because Ranhā (Brahmaputa) is 3,848km while Veh (Indus) is 3,610km.

Three affluents of the Ranhā are named in the Yashts; Aodhas

[174], Sanaka

[175], and Gaudha

[176]. The Brahmaputra passes through Gauda (Bengal) region and hence, a Ranhā tributary would be named Gaudha. This is likely the Jamuna River.

| We sacrifice unto Mithra, the lord of wide pastures, ....sleepless, and ever awake; Whose long arms, strong with Mithra-strength, encompass what he seizes in the easternmost river and what he beats with the westernmost river ("Hindu"), what is by the Sanaka of the Rangha and what Is by the boundary of the earth. | |

—Khorda Avesta 27.104[177] |

- Frazdanava is Lake Rakshasa Tal

The Frazdanava contains the word Danava, implying its connection with the "Danavo" whom are mentioned as villainous. It is also where King Vishtaspa performs spiritual ceremonies. Danavas in many cases of Indian history were Rakshasas.

This area was sacred for ceremonies not just for King Vishtaspa, but also Indians since it is in the Indian Subcontinent and because rṣis lived here.

| Vaisampayana said,--"Then Maya Danava addressed Arjuna, that foremost of successful warriors, saying,--'I now go with thy leave, but shall come back soon. On the north of the Kailasa peak near the mountains of Mainaka, while the Danavas were engaged in a sacrifice on the banks of Vindu lake, I gathered a huge quantity of delightful and variegated vanda (a kind of rough materials) composed of jewels and gems. | |

|

- Avestan Mainakha is Vedic Mainaka

As the names are almost identical they are the same mountain. The Mahabharata claims it was north of Mt. Kailash.

[178] It is known as Mt. Kangrinboqe Feng (6,656m) in Tibet, north of Mt. Kailash (7,694m.)

- Vouru-Kasha is Indian Ocean

Its other names in Mazdaen scriptures are the Frakhvkard and Varkash. Both the names Vourukash and Varkash are reflective of the other name for Indian Ocean city Bharuch, Varukaksha.

[179]Just as the Indian Ocean in Hindu scriptures is referred to as the "Sea of Salt" so to the Khorda Avesta

[180] calls the Vourukasha, the "

deep sea of salt waters."

Practice of similar customs

![]() Sathya Sai Baba

Sathya Sai Baba with a Mazdaen priest during a child's Navjot ceremony (left), and a Mazdaen priest with a child performing the Navjot ceremony (right.)

There are customs that are typically unique to the Mazdaens, but were practiced in India. Some of the customs within the Mazdaen community are similar to those of the Hindu Brahmans. For example, the Navjot and vegetarianism.

Spiritual initiation

"The investure with the Kosti, as described in the Yesht Sade, and alluded to in several places of the Vendidad, appears to be nothing more than the Kaksha, or girdle of the Hindus, blended with some notion of the cord, or Upavita." -

The Quarterly Oriental magazine, review and register[181]

Navjot which means

new birth is the initiation of a Mazdaen and they are given a sacred thread to wear similar to that of the

Yajnopavita ceremony for many Hindus.

Just as the Mazdaen ceremony marks a 'new birth', the Hindu one also does the same. Hence, anyone who receive the Hindu ceremony is called a 'dwija' (twice-born.)

Vegetarianism

![]()

A medieval painting of Gayomard and living beings, displaying that humans and animals lived in harmony.

A large section of Parsis

[182] are vegetarian and during weddings/navjyots, there is always a "Parsi vegetarian" menu. There are four days in a month where all Mazdaens, even the non-vegetarians are expected not to eat meat in a practice called parhezi which means

abstinence. They are Bahman, Mohar, Ghosh, and Ram roj. Meat is also not eaten for three days after a relative passes away.

| Be plant-eaters ('urwar khwarishn', i.e., vegetarian), O you people, so that you may live long. And stay away from the body of useful animals. As well, deeply reckon that Ohrmazd the Lord, has for the sake of benefiting useful animals created many plants. | |

—High Priest Atrupat-e Emetan (Adarbad, son of Emedan) who officiated after the Arab invasion states in the 11th century CE, Book 6, Denkard |

Third century CE Greek biographer, noted in the prologue to his Biography

[183] that the Magi priests of Persia "

dress in white, make their bed on the ground and have vegetables, cheese and coarse bread..."

The modern Ilm-i Khshnum movement in India advocated vegetarianism too.

Dr. Kenneth S. Guthrie believed that Zarathustra promoted vegetarianism.

[184]Usage of plants in worship

Both Mazdaens and Hindus use plants in their worship. During group and individual praying, Mazdaens hold a plant. Also, in the Haoma ceremony of Mazdaens, they use the ephedra in the ritual.

[185]Venerating the same persons

In Mazdayasna, Ahura Mazda is the Supreme Lord and the other supernatural beings are yazatas.

[186] As there are several with a similar name in both Mazdayasna and Hinduism, there are also others whose names are different but are the same persons, such as Sraoesa, who is

Bṛhasa of Hinduism.

- Varuna

- See also: Varuna

"Ahura Mazda has created asha, purity, or rather the cosmic order; he has crested the moral and the material world constitution; he has made the universe; he has made the law; he is, in a word, creator (datar), sovereign (ahura), omniscient (mazdao), the god of order (ashavan). He corresponds exactly to Varuna, the highest god of Vedism."

[187] - Arthur Lenormant

In the Rig Veda, though Varuna remains a god, his influence lessened as many gods took the side of Indra as their king and many humans took him as their chief god.

| Many a year I have lived with them; I shall now accept Indra and abjure the Father Varuna, along with his fire and his soma (haoma) has retreated. The old regime has changed. I shall accept the new order. | |

—Rig Veda 10.12.4 |

| Varuna | Ahura Mazda |

| "I made to flow the moisture-shedding waters." | "Rain down upon the earth to bring food to the faithful and fodder to the beneficial cow." |

| Rig Veda | Vendidad |

The Vendidad is called in Pahlevi the Zhand-I Jvit Dev Dat. Here the 'Dev Dat' portion of the title refers to the conch of Ahura Mazda. The Dev Dat is mentioned in Hindu scriptures as the conch of Varuna.

There is a strong connection in Hindu scriptures between Varuna and Asuras. For example, the Mahabharata mentions that he receives homage in his palace by asuras. He is also said to live in the ocean with Nagas, and his residence there is known as Asuranam Bandhanam. Then according to the Valmiki Ramayana, Ravana had invaded Rasātāla where lived Varuna, his sons, Nagas, and Daityas. According to the Srimad Bhagavatam

[188],

Hiranyaksha visted Varuna to seek his advice on whether to fight Vishnu or not (in which Varuna advised the Daitya king to do so to earn Vishnu's grace by being slain by him.) Hiranyaksha there had called Varuna "

Adhiraja" (

Supreme Lord!) The Mahabharata claims that Varuna governs Rasātāla, 1 of the major strongholds of the Asuras. Hiranyapur, another stronghold (where Prahlad Maharaj governed from) was also affiliated with him. Further, Varuna is the one of the few gods that have Asuras as administrators. Varuna's are Meghavasas in his assembly, and another named Sunabha.

| O Yudhishthira, without anxiety of any kind, wait upon and worship the illustrious Varuna. And, O king, Vali the son of Virochana, and Naraka the subjugator of the whole Earth; Sanghraha and Viprachitti, and those Danavas called Kalakanja; and Suhanu and Durmukha and Sankha and Sumanas and also Sumati; and Ghatodara, and Mahaparswa, and Karthana and also Pithara and Viswarupa, Swarupa and Virupa, Mahasiras; and Dasagriva, Vali, and Meghavasas and Dasavara; Tittiva, and Vitabhuta, and Sanghrada, and Indratapana--these Daityas and Danavas, all bedecked with ear-rings and floral wreaths and crowns, and attired in the celestial robes, all blessed with boons and possessed of great bravery, and enjoying immortality, and all well of conduct and of excellent vows, wait upon and worship in that mansion the illustrious Varuna, the deity bearing the noose as his weapon. | |

—Section IX, Mahabharata[189] |

While the Rig Veda directly calls gods out as Asuras, it also indirectly refers to Varuna as an "

Asura of heaven"

[190], and latter verse heaven itself is called 'asura'

[191]. Also in a verse in which Asura is mentioned, it reads, "

our father pours down the waters."

[192] Further, the RV says that Agni is born from his (the Asura's) womb.

[193] This is important in showing that Agni is a child of Varuna just as the Holy Fire (Atar) is mentioned as the son of Ahura Mazda in the Avesta.

Ahura Mazda's connection to Vahiśta goes back to Varuna's relation to Vasiśṭha from Hindu scriptures. For example, The Ramayana mentions that Vasiśṭha was a son of Varuna through Urvashi born at Varunalaya (modern Barnala, Punjab.) He was also said to have turned his son Vahiśta into a scholar by simply accompanying him on a boat trip. Varuna had taught what is called "Bhrgu-Varuni Vidya" to his son Bhrgu of which the essence was "Brahm (God) is nothing but joy."

The name 'Zarathustra' means

Golden buffalo, which is because the animals involved in sacrifices to Varuna were usually buffaloes

[194]. This is akin to Hindus being named after a vehicle of god, such as Basava or Nandi, the bull of Shiva. These names reflect devotion and subordination as servants of gods.

- Kavi Uṣana

An Ahura of Mazdayasna is known as an Asura in Hinduism. It is then no surprise that we also find

Śukra Acharya or Kavi Uṣana, the Guru of the Asuras, being venerated as one of the most holy beings. His connection to Varuna in Hindu scriptures is that he is Varuna's devotee in many instances as seen in Satapatha Brahmana

[195]. In the Avesta he is known as Us and later in the Bahram Yasht as Kavi Uṣa.

[196] | This one is known to me here, who alone heard our precepts: Zarathustra, the Holy, he asks from Us, Mazda, and Asha, assistance for announcing, I will make him skilful of speech. | |

—Yasna 29, Avesta |

Kavi Uṣa is also called Kava Uṣan and Ashvarechao, which means

full of radiance just like how his Hindu name Śukra means

radiant and how scriptures like the Yoga Vasiśṭha

[197] describes him as "

radiant young Śukra", or Ramayana

[198] describes "

Śukra, radiant as the sun, departed."

The Avesta doesn't refer to him as Śukra because that name is reserved as an epithet for Ahura Mazda, who is invoked as, "

athra sukhra Mazda"

[199] (Kavi Uṣana has

many titles.)

Uṣana is also given importance because he

descends from Angiras. Mahabharata reads that Kavyas descendants from Kavi.

[200] Manu Smriti establishes a Kavi as a descendant of Angiras.

[201] Like how Uṣana is a regent constellation in Hindu

astrology, he is a star included among the Great Bear constellation, in the Hapto-iringas of the Avesta.

[202]- King Ram

- See also: Rama

Mazdaen scriptures mention a righteous monarch named Ram, whom it addressed Ram Khshatra. Though it doesn't dive into details about the yazata, it usually mentions him together with Mithra. In Hinduism, he is known a Raja Ram, a noble king, "Arya that cared for the equality of all", descendant of Mitra.

| Rama, descendant of the sun ("Mitra"), became friends ("mitra") with Sugriva, son of the sun ("Mitra.") | |

—Ramayana, 15.26 |

There is even one passage in the Avesta that mentions Ram together with Vahiśta, which is symbolic of the relationship in the

Ramayana that Ram has with his guru Vasiśṭha

[203]. It also shows the relationship between Mithra and yazata Ram.

| We sacrifice unto Mithra, the lord of wide pastures; we sacrifice unto Rama Hvastra.

We sacrifice unto Asha-Vahiśta and unto Atar, the son of Ahura Mazda. | |

—Khorda Avesta 2.7 |

[204]Sacredness of the sun

The sun is like fire, a holy symbol of Ahura Mazda. The Avesta declares:

| This Mithra, the lord of the wide pastures, I have created as worthy of sacrifice, as I, Ahura Mazda, am myself. | |

—Avesta |

[205]Mitra is a god often paired with Varuna in Vedic hymns. There are many Hindus today who worship God Almighty in the form of the sun and they are known as

Sauras. The Māga Brahmaṇas are very closely associated with the sun-worship in Hinduism.

Just as the Rig Veda declares that the sun is the "

Eye of Varuna"

[206], the Avesta

[207] it also declares that

Mitra is the eye of Ahura Mazda.

[208]Prayer terminology

Just as Hindus include the word namo in their mantras, such as 'Namo Varunaya'

[209][210] or 'Namo Jinanam', Mazdaens too apply the term in the phrases 'Namo Ahurai Mazdai', 'Namo Zarathushtrahe Spitaamahe', 'Namo Amesha Spenta' and 'Namo Heomae'.

'Nemase-te' is another term used by Mazdaens which is the equivalent of Sanskritic Namaste.

'Neueediem' has the Sanskritic equivalent 'nivedayami', which has been used in Hindu verses like "Om Owing Saraswatai nivedayami."

Praying ceremony for departed ancestors

Both Mazdaens and Hindus offer prayers for their ancestors, and the procession meant solely for their well-being is known as the 'Dhup Nirang' (Gujarati for

ritual of offering of frankincense) or 'Nirang-e Rawan-e Guzashtagan' (Persian for

Ceremony for the souls of departed ones) amongst Mazdaens

[211] and as 'Śrāddha' amongst Hindus.

Corresponding festivals of Mazdaens and Kashmiri Hindus

Just as Mazdaens celebrate Ahura Mazda (

Varuna) and King Jamshed, so too do Kashmiri Hindus. The Mazdaen calender new year, celebration Nuvruz, is the same festival as that of the Kashmiri Hindus, Navreh.

[212]During the festivity of Tararatrih, on the 14th of the dark half of Magha, King

Yama is worshiped.

[213] On Varuna Panchami, Varuna is worshiped.

[214] Varuna is worshiped again on the 5th day of the festivity of Yatrotsava, whereby Hindus are encouraged to visit his 'abodes' or temples.

[215]Celebrating god Mitra has historically also been a part of Kashmiri culture. Till the 11th century CE, the Kashmiri Pandits celebrated Mitra (Mithra) Punim, on the fourteenth or full moon night of the bright fortnight (Śukla Pakṣa) of the Hindu autumn month of Ashvin or Ashwayuja. Similarly, the Mazdaens celebrate Yalda as the birth of Mithra.

[216]Usage of fire in ceremonies

![]()

Ateshgah of Baku fire temple in Baku, Azerbaijan which was utilized by Hindu priests from India.

Fire is used in processions of both Mazdaens and Hindus. Their temples use fire altars for performing the rituals. Fire altars have been discovered in the Indus Valley city of Kalibangan in northern Rajasthan state, showing that even the ancient society then revered fire as sacred.

Ceremonies

"Although sacrifices are reduced to a few rites in the Parsi religion now-a-days, we may discover, on comparing them with the sacrificial customs of the Brahmans, a great similarity in the rites of the two religions." - Martin Haug

[217]

In addition to the ceremonies of Navjot and praying for ancestors, there are other similar ones for the Mazdaens and Hindus.

|

| Afrigan | Apri | The ceremony is meant to invite persons; during Afrigan a deceased person or an angel, and during the Apri a god. |

| Darun | Darsha Purnama | During the Darun, sacred bread is offered, whereas on the Darsha Purnama the sacrificial cakes are offered. |

| Gahanbar | Chaturmasya Ishti | Gahanbar involves offering sacrifices 6 times a year, whereas the Chaturmasya entails sacrifices given 4 times. |

| Yajishn (Ijashne) | Jyotishthoma | The both, the twigs of sacrificial plant ('Homa'/'Soma') itself are brought to the sacred spot where the procession occurs and the juice is extracted during the recital of prayers. The Yajishn (Ijashne) implements a plant that grows in Iran whereas the Jyotishthoma implements the Putika. |

Mouth covering of priests

Mazdaen priests wear the padam over their mouth just as many Jain monks wear the mohapatti. The purpose of the Mazdaen clad is to prevent pollution through the products of the mouth when handling the sacred fire.

Purification before worship

Because yazatas (venerable spirits) are pure, to pray to them it is encouraged that the worshiper be clean, and so devotees wash their hands and faces.

Hindus, although they pray in several occasions and environments, normally they perform puja in the morning after having bathed.

Mazdaens are in most temples required to remove their footwear because the temple is very sacred and because of its sanctity it is not to be contaminated with either spiritual or material filth.

Hindu temples too require the visitor to remove footwear for the same reason.

Astrology

Zarathustra has been written in Mazdaen scriptures of having practiced the science and the Kitāb al-mawalid (also known as the Kitāb Zardusht), an astrological scripture, is attributed to a 'Zardusht' in the scripture itself, and certain modern scholars believe that this Zardusht may in fact be the original Zarathustra.

Just as several Brahman priests of India have historically practiced astrology, and to this day many still do, the priests in Zarathustra's time applied the science too. When Zarathustra was in the womb, his mother had a frightful dream, so she consulted an astrologer that assured her she had no reason to fear for his birth and he predicted the baby's glorious future.

[218]Hindu astrological similarities to that of Mazdaen texts translated by Theophilus have been noticed by Pengree who believe this was likely because Hindu Brhadyatra and other works by Varahamihira were translated into Persian, which were the ones Theophilus had read.

[219]Sky burials

In one period of history, even feeding corpses to vultures as opposed to either cremating them or burying them was the norm in parts of the Punjab region. Aristoboulos, when visited Taxila,

[220] had stated that the dead were "

thrown out to be devoured by vultures."

[221] This practice is still observed in parts of western Tibet which is modern-day Avestan Ranha or Vedic Rasātāla.

Raghunath Rai discusses that leaving corpses for birds and beasts was historically one way that Indians since ancient times had disposed of the dead.

[222] He also leads to the conclusion that this was practiced by Indus Valley Civilization residents of Mohenjo Daro because skeletons have been found in public places and within a room.

In the Mahabharata King Astaka mentions three different kinds of corpse-disposal; cremation (dahyate), burial (nikhanyate), and decay (nighrsyate).

[223] Vidura then mentions 2 modes; cremation on a funeral pyre or the body is left for birds to consume.

[224] King Virata after he was slaughtered by the Kauravas had his corpse offered to vultures by Dronacharya.

Even in South India, decomposition by vultures wasn't unheard of in certain places. The author of the Manimekalai writes of exposure of the corpse to be devoured by vultures and jackals as 1 of 5 decomposition methods.

[225]Zarathustra as a cave mendicant

Ancient Greek writers Eubulus, Porphry and Dio Chrysostom had written of Zarathustra's time living in a mountainous cave wherein he is said to have lived for ten years. The way in which he lived is of a similar description to that of Brahmans of that time. This was "

Mount Kāf [which is the] mountain Usihdatar,..."

[226]The

Vessantara Jātaka gives this description of Brahman ascetics: "

looking like a Brahman with his matted hair and garment of animal skin with his hook and sacrificial ladle, sleeping on the ground and reverencing the sacred fire".

Why Zarathustra wore knotted-hair and a turban

![]()

Kashmiri Pandits in traditional white phiran (tops), shall, and turban wear sporting a beard. This strikingly resembles Zarathustra's fashion.

The turban is mentioned in the Atharva Veda as an ushnisha.

[227]Vasiśṭha is associated with the turban more than other Vedic sages. In the village of Vashisht in Himachal Pradesh during the birthday of Vasiśṭha his statue in the main temple of the village is adorned with a white dhoti and turban.

[228]In the Rig Veda and Kathaka Grhya Sutra, Vasiśṭha wears a kapardin or knotted-hair.

Applying ash to forehead

Mazdaean many times in their ceremonies apply Rakhya ash from a ceremonial fire on their foreheads just as Hindus many times in rituals mark foreheads with

tilaks of either ash or paint.

Bull statues in front of temples

Some Mazdaean temples have Bahman Ameshaspand winged-bulls at temple entrances just as many Hindu temples have Nandi (or Vasava) bulls at entrances.

Depicting figures as animal-headed

![]()

Lion-headed Zurvan from Mithraic Mazdaen temple.

Like many Hindu icons, in Mazdaen ones too, gods are depicted as animal-headed sometimes.

Social classification

Whether castes in any Mazdaen society, apart from the Brahman one (Athravan), existed or not is certain. However, we know that the laborforce of society in Mazdaean scriptures is categorized like the one that exists in India; Athravan/Sodalen (Priest), Rathaestar/Ritter (Warrior), and Vastrya-fsuyant/Varazana/Dragu/Driyu (Agriculturalist.) In fact, Zarathustra's 3 sons were said to be the heads of these classes ('pistra') — Isatvastra of the priests, Urvatatnara of the warriors, and Khvarechithra of the agriculturalists. Eventually, a Huiti (Artisan) class came to be recognized.

The Mahabharata mentions that in

Sakadwipa (Iranian Plateau and Central Asia but more specifically, Balkh) there are four castes; "

They are the Mrigas (Brahmans), the Masakas (Kshatriyas), the Manasas (Vaisyas), and the Mandagas (Sudras.)"

[229]Symbolisms

Dualism

- See also: Dvaita

Mazdayasna views the universe as a place of mingling between Asha (good) and Druj (evil.) Known in Sanskrit as

Dvaita, it relates to how the universe is divided into matter and spirit. Matter is ignorance and an illusion (

Maya) and corrupts souls, while spirit is holy and true.