The science of modern linguistics is built on the pattern of the Indo-European (IE) linguistics, rather to the detriment of the science. The pattern of the IE linguistics carries its reasoning and problems to every other linguistic group, bearing on the relationship between Türkic in English and quite a few other “IE languages”. The problems of the IE linguistic theory are massaged from its inception 200 years ago by self-policing acolytes who nearly always found partial fixes, but a systematic synopsis of the problems and solutions has never existed; to see an impartial critical synopsis of the IE linguistics is an event of the epochal scale. Instead of periodical general review done by any other discipline, this field had discretely circulated dispersed criticisms, citations of diverse opinions, and discussions of some particular aspects, all with an implied premise that the theory is right, albeit requires tweaking. The offered citations on the theme of the sanity of the IE linguistics are extracted from the work of Angela Marcantonio, an editor of a linguistic compendium, who wrote an editorial introduction that laid out IE problems, inventoried positions, analyzed situation, and drew conclusions. The punch line is jesting, it rings “it is hard to pin down what the foundations of the theory are actually supposed to be”. In science, any theory rests on fundamentals. If the fundamentals are not fundamental, the term “theory” is a misnomer for speculation, propaganda, a set of beliefs, and the like craze promoting some cause. The past 200 years have proved that, every imbalance of the IE theory was mitigated by shifting foundation over under. These shiftings, hatched to fix specific problems particular to the IE model, as scientific approaches are useless for the IE linguistics, and even less applicable for the rest of the world's linguistics.

This posting cites the snippets taken from the Angela Marcantonio's Introduction, and as always, the devil is in the details, they need to be traced in the original publications, follow the links for the JIES and JOES publications. Few accents may be added.

Any editorial comment added to the text of the author and highlighted in (blue italics) or blue boxes is posting comment unrelated to the views of the author. The author explicitly does not personally believe that there may be a Turkic substratum to IE, or to Sanskrit, not only because there was no IE, but also because, even if IE had exited, the time and area of the two language groups do not add up, each appearing at the scene of history far apart from one another. The author does not subscribe to any links between the Turkic languages and IE, or Sanskrit.

The origin of the “IE theory” was apt to its time, a biblical model where Noah produced Semitic Shem, African Ham, and Eurasian Japheth, otherwise depicted as a Family Tree. The modern linguistic terminology still uses biblical tales, Semites are from Shem, and Hamites are from Ham. The IE linguistics formed as an obverse side of a racial coin, its dignified theoretical side, while the now eroded reverse side was a practical reality. The biblical model implies that at one remote point in time existed a formed language that split off into various dialects that grew into languages and language families. In most cases, that is a fallacy. The tiny bands of hunter-gatherers needed large tracts to forage, reaching into other's territories and initiating social exchanges. Creolization held the day, or rather many millennia. Then, the “Family Tree” had a shape of a grass lawn with stolons extending from every base and crisscrossing with stolons of their neighbors. After a drought, the surviving islands were restarting the process uncountable number of times. A most aggressive weed propagated and conquered. The emergence of the roving agriculture and animal husbandry tilted creolization toward the more fecund side, the Family Tree took a shape of brush spots in a grassy lawn. Leveling became a greater force in communications, all linguistic aspects were affected by leveling, typology, syntax, morphology, and phonetics. That trend grew with introduction of a 3-field system starting in 800s AD, which reduced agricultural roving, with companion linguistic fallout. The resultant leveling gave Family Tree a shape of groves in brushy tracts surrounded by grassy lawns. The printing presses of the Late Middle Ages made leveling ubiquitous at the expense of minority languages and dialects. At the same time, increased productivity of agriculture allowed rulers to engage in permanent warfare that stirred and dispersed subject population along the path travelled by cattlemen ranchers five millennia earlier. It took another 1000 years for the emergence of linguistics and its biblical-type etiology. Some linguists might have thought of the example of biological evolution. It took another 200 years for some linguists to realize that their model is hopelessly faulty, and come up with an alternate Wave model.

Every and all IE linguistic broodings see the ancient languages as some frozen codified entities, while our recent experience attests that languages are dynamic creatures with definite lifetimes and a spatial differentiation that makes versions separated by a mountain ridge or 200 km distance mutually unintelligible. So people speak 2, 3 languages, or whatever is needed. One of them is an areal pan-language that is used as a first and last resort, a lingua franca. Each language influences the others in all linguistic aspects, that is an areal Sprachbund. There comes a revolution, a new language becomes a pan-language, say, Greek, but the old pan-language keeps living within all languages of the Sprachbund. There comes a revolution, a, say, Latin language becomes a pan-language. Then the new pan-language and local languages evolve, becoming a tool of the literati, who start to codify them, setting rules of right and wrong, and deliberately pushing the wrongs way down. Then comes a linguist that discovers too many synonyms and homonyms, and a general linguistic chaos that needs to be systematized and classified. A linguistic model is born, full of contraventions, but suitable as an unifying force blind to its inner conflicts in all linguistic aspects. Throwing the effects of the layers of non-codified and mutually unintelligible causes into the IE studies makes the confused theory unmanageable. The model bursts from the inside.

One predominating theme of the Introduction is that linguistics is a science with no laws. The laws are created as needed, adjusted as needed, manipulated at will, and have premises as their conclusions. The only reliable element in the study of the linguistic laws is not taught, because it augurs that there are no laws. No law or a defined set of laws can take a student from Anglo-Sax. to English, in reverse, or in any direction. The only utility of the linguistic laws is the self-perpetuating education industry.

Unfortunately, the typology, a most basic property of language is totally unaddressed, as if it is not linguistics but a whimsical idea. In the ratings of importance within linguistics, typology trails endings in some God-forgotten IE language with a dozen of active speakers. That is not to say that the scholarship of 460 IE languages has 460 dictionaries, in fact it is far from that. And typology trails the last of them

One of the leading linguistic parameters is “genetic connection”, like “Noah begot Shem”, used as a premise (i.e. cognates) and as an objective. Genetic connection is a statistical parameter with 2 levels, that of a word, and that of a paradigm (class of all items). On the level of word, a critical threshold must be present, constituting a lexical paradigm; the other paradigms may consist of other shared innate linguistic properties. Aside from its inability to project into the future, what sets the linguistic genetic connection apart from the science is the absence of a demographic aspect. Unlike languages that are carried by warm bodies, the linguistic languages are carried by spirits entitled “demic diffusion”, “elite dominance”, and the like abstractions. The roles of maternal language imbibed with milk, of generations raised by mamas systematically imported from the same group, and other physical processes of systemic recurrent movements (a la colonization of Americas) and incidental impacts (a la nearly instantaneous spread of literacy) with heavy demographic impact are systematically neglected. The distorted vision turns a lively bouquet of a blend of languages brought into the family of any modern language into an unrealistic scheme fit for inclusion into unrealistic “IE theory”. Languages as diverse as analytical English, agglutinative Armenian and Ossetian, and morphologically rich Romance languages are facetiously combined into a single rubbery class.

A reader should keep in mind that the oldest writing in the world belongs to Sumerians, ca. 4,500 BC, and no claims to deeper knowledge are evidentiary supported. We can do many things theoretically, like weighing stars, because we have hard and validatable scientific toolbox, but the intuitive linguistics falls way short from being a science yet.

Is this analysis auguring the wane of the easy come - easy go biblical model and a coming of a real science? Not so fast, first we need an uncomfortable sober-up period, and a shift of the entire IE education industry. As to the nearly sanctified LIV (IE etymological dictionary), a single critical review by non-IE linguists would go a long way toward its credibility.

Page numbers are shown at the bottom of the page. The posting's notes and explanations, added to the text of the author, are shown in parentheses in (blue italics) or blue boxes. |

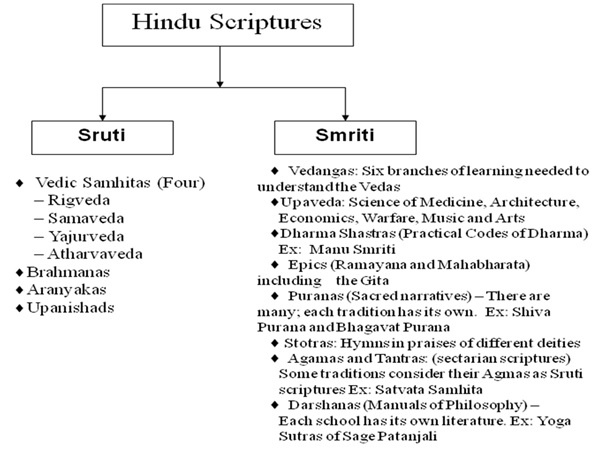

38 1. 1. The purpose of the present volume is to survey the current state of the Indo-European (‘IE’) theory in the light of modern linguistic knowledge. Included in the survey is also extra-linguistic evidence, such as recent archaeological, genetic and palaeo-anthropological findings. Its ultimate purpose is to revisit the validity of the various tenets of the theory. In fact, when scholars refer to the “IE theory”, they may be referring to one of a number of competing, and sometimes contradictory, models. For example, some regard IE as purely a linguistic classification, whilst others regard it as an attempt to reconstruct a ‘real’ pre-historical language. To take another example, some scholars hold that the original IE protolanguage was a morphologically complex language, similar to Sanskrit, whilst others argue it was morphologically simple....in a single volume, these various approaches and views about IE that it clearly and explicitly emerges how surprisingly different and, often, even deeply contradictory, these views and approaches may be. Thus, the IE theory is widely accepted despite the fact that opinions differ enormously on what the theory actually comprises. Opinions may clash even as to the very nature and validity of many of the underlying tenets of the theory – whether explicitly stated or quietly assumed. For example, as mentioned, some scholars regard the subject a ‘pure theory’, which helps to describe correlations between languages, whilst others regard it as a valid means to reconstruct pre-historical facts. Although there seems to be a widely shared assumption that at least a ‘hard core’ of the correlations among the IE languages are ‘compelling’ – that is, too striking to be the result of chance – there may be deep divergences on how to interpret these correlations, as well as on other, less central but equally important aspects of the theory. In other words, contrary to what one would expect, the wide acceptance of the IE linguistic classification does not appear to be accompanied by a parallel acceptance of a coherent and equally agreed set of tenets, a coherent common denominator, consisting of what one could call the ‘hard linguistic evidence’ and the ‘fundamental principles’ upon which the theory, supposedly, is based.

39 ...This, ultimately, amounts to the task of re-assessing the founding principles of the theory. In particular, one might reasonably ask the following questions:

1. How is it possible that such widely differing and often contradictory views are still unresolved today?...

2. Is the IE theory a ‘scientific’ theory, that is, has it been established through “methods of analysis which produce results that are subject to invalidation”1? If so, what precisely is the evidence counter to the model?...

3. As an alternative, some scholars believe that the theory cannot be invalidated and therefore is not a ‘scientific’ theory; nevertheless its validity is simply ‘compelling’. What is the basis for this claim?...The points of views and perspectives... have hardly been dealt with and confronted with one another..., despite being inextricably interdependent. As a consequence, the questions raised in the points (1)-(3) above have hardly been addressed in a targeted and systematic way. ...there are plenty of publications dealing with the issue of the strengths and weaknesses of the methods of historical linguistics... However, these publications hardly ever ponder on whether the acknowledged weaknesses may have a negative impact on the IE theory and, if yes, to what extent. Similarly, there are many publications revolving around “how real(ist) are reconstructions” (Lass 1993), but their scope hardly ever extends to encompass the consequent issue of how to best interpret the IE reconstructed, comparative corpus. On the other hand, there are plenty of publications which... revolve only around the question of the whereabouts of the (assumed) IE proto-community. ...textbooks of IE linguistics (and, often, specialist publications too), hardly ever mention any of these ongoing debates. ...the fact remains that textbooks typically present a highly idealized, monolithic picture of IE: a paradigmatic, problem-free language family, where everything works (especially sound laws, lexical and morphological correspondences), where there are hardly any contradictions or ambiguities in the linguistic or extra-linguistic evidence, or even any significant divergence of views among scholars. ...this idealized picture is in stark contrast with the messy reality – in terms of variation, high level of exception, contradictory evidence, etc. – found in practically all the other language families of the world, as well, admittedly, within branches of IE (such as the Romance and Germanic languages, or the Balto-Slavic continuum, etc.). This in turn has lead several scholars (such as Grace 1990 & 1996) to come up with the rather ‘aberrant’ idea that there must exist in the world two basic types of language families: the ‘the exemplary ones’ (IE and just few others) and the ‘aberrant’ ones (all the rest).

40There are, of course, textbooks that present... the poor quality and /or quantity of the evidence in support of otherwise widely accepted theories. One may compare, for example, Szemerényi’s (1973 & 1996:122 ff.) and Gusmani’s (1979) account of the slippery evidence on which the laryngeal theory is typically based on the Hittite side, or Sihler’s (1995:144 ff.) account of the factual and methodological obscurities found in Verner’s Law, one of the most revered IE sound laws. However,... it is difficult to evaluate their potential impact on the validity of the theory, or simply just to acknowledge them. ...if, at some stage in the history of a theory the amount of evidence counter to the model reaches what is usually called a ‘point of critical mass’, then a revision of the theory might be in order, whether to modify or update its tenets, or, if necessary, to reject it altogether. In other words, minimizing, re-interpreting or adjusting any evidence found to be inconsistent with the model might be misleading, and therefore not desirable. In fact, scholars identifying problems in their area of research may wrongly assume that the matter has been settled beyond doubt in other areas of study, ...in this way, unwillingly, and maybe wrongly, contributing to reinforce the validity of the theory in question.

412. The comparative method and the sound laws2.1. The strengths and weaknesses of the comparative methodThe debate revolving around the issue of the strengths and weaknesses of the comparative method is an intense, long standing debate. In fact, establishing regular sound correspondences is considered by several (many / most?) scholars to be a crucial part of the process of establishing language families (see for example Campbell (1998:315)). ...this debate has hardly ever been associated with a targeted, extensive investigation of the possible impact the weaknesses of the comparative method may have on the validity of IE as a linguistic classification. In particular, the long standing “Lautgesetz controversy” (for which see Wilbur 1977) subsided without resolution, and despite its recent resurfacing in publications dealing with several linguistic areas / families in the world (see for example Ross & Durie (eds, 1996); Blust (1996)2, Aikhenvald & Dixon (eds, 2001), etc.), it is rarely referred to in textbooks of IE. In fact, these usually assume, whether explicitly or implicitly, that the ‘regularity principle’ and the related family tree model have been established in IE beyond doubt, through the support of an extensive amount of data derived from the various IE languages.However, this is not necessarily the case... As a consequence, the reader, including general linguists or even experts in historical linguistics who are not acquainted with the details of IE, may be excused if they are confused as to the actual ‘quality’ and ‘quantity’ of the phonological / lexical correspondences conventionally established for IE. Indeed, within IE too irregularity and exceptions do occur – it would be odd otherwise.

42 However, the vital questions are:

A) How pervasive is this irregularity?

B) Is it really true that the encountered irregularities can, in most cases, be justified through ‘genuine’ linguistic processes, that is, without stretching the explanatory system up to the point of dangerous ‘circularity’, by ‘appending’ ad-hoc justifications?The reader who would expect an answer to these questions which is coherent, unanimous, and, most importantly, decisive – one way or the other – might be disappointed. To show that this is the case, here is a list of the most common justifications put forward to answer question (A):1. Only the ordinary nouns in IE, particularly those referring to objects and concepts of everyday life, display a high degree of irregularity (much higher in any case than verbal roots), but this is only because they belong to the lower level of speech, the lower level stratum of the IE population (Meillet 1934: 396 ff.; Benveniste 1935:175 ff.).2. The irregularities are only, in most cases apparent, in the sense that linguists have not yet found the appropriate explanation to account for them.3. There are some / many / plenty of irregularities (according to interpretations), but there is nothing to be surprised about. We know that sound changes do not proceed so regularly after all, but this does not have a negative impact on the validity of IE, whose establishment, in fact, has not been based (only) on the phonological / lexical correlations, but on the morphological ones. Such a view is embraced, among others, by Harrison (2003:214 ff), Greenberg (1987:18; see also Croft 2005) and, in this volume, by Kazanas. For example, Harrison (2003: 217) states that: “If one can prove that even one single cognate pair holds over two languages, one has proven those languages genetically related”. The (implicit) claim here appears to be that proper lexical ‘correspondences’ are generally hard, if not impossible to attain. Therefore, linguists must come to terms with the fact that also within IE (like within other language families or across macro-families) the correlations among the assumed cognates are not, in the main, as ‘regular and systematic’ as generally claimed.| This is probably the most inept claim of all claims related to linguistics in general. The mechanism of estimating probability of chance lexical coincidences shows that any two languages have a considerable proportion of lexical coincidences with probability exceeding 1, i.e. in each case is at least one and possibly more valid correspondences. Statistical probability drops exponentially with the increase in the number of morphemes in the word. Any two languages can be mechanically compared across entire dictionary, with probability value for chance lexical coincidence established for each lexeme in the language using the frequency parameter of each morpheme in the language being compared. Once the algorithm is established, comparison and results are produced automatically, providing hard and validatable parameters. The process may be performed with any desired accuracy by setting up the width of phonetic and semantic fields. |

43...As to the answer to question (B), we are not aware of any research carried out with the specific purpose of ascertaining whether or not the circularity issue has had a negative impact on the soundness of IE......On the issue of the reliability... of sound laws, ...the following statement made by Clackson (2007: 60-61) with specific reference to the laryngeal theory: “The comparative method does not rely on absolute regularity, and the PIE laryngeals may provide an example of where reconstruction is possible without the assumption of rigid sound-laws”. This statement begs the question of why, when and where, and on the basis of which criteria, scholars may – or may not – assume the existence of “rigid sound-laws”.2. 2. The circularity issueIf – as it seems – the circularity issue has not been solved (yet?), scholars could attempt to set up some sort of qualitative and / or quantitative constraint to the number of the defining parameters a given law may consist of. In practice, however, as far as we are aware, there has never been any such attempt. On the contrary, in the every-day, painstaking practice of establishing sound laws and correspondences, any mismatch in the evidence (ambiguity or absence of the expected outcome, exceptions, etc.) can always “be explained away” through a range of procedures, a range of ‘adjustable parameters’, to be added to the original definition of the law. In other words, instead of casting doubts on the validity of an assumed law (and, if necessary, dropping it) when faced with exceptions and difficulties, typically the practitioner tries to ‘rescue’ the stated law, even at a cost of making recourse to a (virtually unlimited) number of (often ad-hoc) adjustments, such as:

441. re-defining the law

2. identifying a different starting-point of the law

3. assuming borrowing, from other languages, or ‘transitional’ dialects, or even from unknown (phantom), extinct languages /dialects

4. assuming analogical processes

5. re-arranging the stated sequence of rules in a different order

6. postulating a (/another) laryngeal segment

7. stating that the mismatches in the expected outcomes of the law are not significant for calling into question a theory as well established as IE. The obvious consequence of this circularity deeply embedded in the comparative method is that the explanatory system runs into the risk of becoming so powerful, so flexible, that it can be stretched to match almost any data, in this way making it impossible to compare the results it yields against the predictions of the model. In other words, although each single ‘adjustable parameter’ as listed above may in itself reflect a plausible, genuine linguistic process, the overall cumulative effect of many adjustable parameters added to the definition of a given law may endanger the ‘cumulative effect’, the ‘statistical significance’ any established ‘law’, or even ‘tendency’, should display to deserve these names. This is an issue that has hardly ever been properly and systematically addressed...Although the supposedly rigorous, ‘scientific’ nature of the comparative method has often been called into question, and more objective quantitative methods of analysis have been at times adopted within historical linguistics, the statistical significance of the IE comparative corpus itself (both the phonological (/lexical) corpus and the morphological one) has never been tested.......Authors have used the IE family, whose validity is taken for granted, basically as a ‘control case’ for various kinds of statistical tests within historical linguistics, but have not tested the statistical significance of the IE comparative corpus itself.

45...Marcantonio... argues that the great majority of the conventionally stated IE sound laws lack statistical significance and that, therefore, most of the conventionally established correspondences (within the LIV corpus) are simply similarities, most probably in the given sense of ‘chance resemblances’.2. 3. Borrowing vs inheritance...the possibility that the established ‘cognates’ – be they ‘similarities’ or proper ‘correspondences’ – may be due to the common processes of borrowing, diffusion, convergence, or even chance resemblances. As is known, borrowed words tend to integrate into the sound pattern of the receiving language, as well as undergoing the same (more or less regular) changes that inherited words would undergo. Thus, the identification of borrowed elements on the basis of internal, linguistic clues only might not always be easy. Therefore, sound correspondences, whilst fundamental to most approaches in assessing language families, “can be misused”......several semantic fields within the IE basic lexicon..., in addition to being mainly irregular, typically lack a wide distribution across the IE area, being often confined to just two or three contiguous languages... In contrast, the cognate terms for ‘mother’, ‘father’, ‘brother’, ‘daughter’, etc., display a much wider distribution, and a higher degree of regularity. This factor has correctly raised the suspicion that processes of loss (and consequent replacement) of original words, or even processes of chance resemblance, may have been involved in this area. The issue of the wide vs restricted distribution and the (degree of) irregularity of many basic cognates within IE is interpreted differently by different scholars... ...patterns of original words are typically retained, and are therefore easily identifiable even within a context of extensive borrowing...

462. 4. Is the phonological evidence malleable?...one could certainly argue that the conventional, phonological / lexical evidence on which the IE theory is based, to a closer scrutiny, appears to be rather ‘malleable’ – it is certainly not as decisive (one way or the other) as generally claimed. As a matter of fact, it is always possible to find a plausible, although not always testable, justification to any intervening piece of evidence counter to a stated rule or tendency. Similarly, it is also always possible to provide at least two equally plausible, equally well founded explanations for any given linguistic phenomenon.This is also the case within non-controversial areas of IE linguistics, such as the postulation of the so-called ‘Indo-Iranian branch / unity’. One can in fact compare the different interpretations given to this unity – (also) on the basis of phonological /lexical evidence... Schmitt... argues that the data from both Vedic and Sanskrit are not with absolute necessity genuinely antique and that, therefore, Old Indo-Aryan is not as close to PIE as still believed by some scholars...At this point one could object that all these methodological and factual difficulties do not, after all, matter, even if they did impact negatively on the validity of the conventionally established sound laws (and related correspondences and reconstructions). This is because... the lexicon is often considered to be the level of language less (or not at all?) relevant for the purpose of assessing genetic relationships. This would be sound and acceptable if there were indeed a consensus among Indo-Europeanists as well as comparativists in general on the principle that it is morphology the level of language (mostly?) relevant in this context...3. The role of morphology3.1. Is morphology the most reliable indicator of genetic inheritance?| Unlike lexical comparisons, a low-hanging fruit that needs only a dictionary, morphological comparisons require innate knowledge of compared and candidate languages. Within the IE family, morphological comparisons are as problematic as comparisons between morphologically far-away individual families, attesting that IE languages belong to different morphological families. Applying some notion grown from the IE unity concept to anything grown with an alien morphology, where a morphological element from an unsuspected language is treated as a root element of the IE base form, leads to grotesque conclusions and even more grotesque reconstructions, comparisons, and final judgments. In a minimal case, with one-syllable CVC-type word taken as an IE base root, the second consonant may be a bound marker of deverbal concrete noun that points to the origin of the word from a foreign verb never suspected and never investigated by the grotesque-headed linguist uninitiated on the significance of morphological elements outside of the IE unity concept. |

473. 2. The degree of ‘borrowability’ of grammarIn recent years a mounting body of evidence has been accumulating according to which not only grammar is found to be ‘borrowable’, but, given the appropriate historical and social context, it may rate quite high on the scale of borrowability. It could therefore be difficult to determine whether shared grammatical innovations are the result of genetic inheritance or of areal convergence. ...is grammar borrowable to such an extent that historical reconstruction becomes impossible?...

48...within IE studies there is still an open question regarding the nature of the original morphological structure of PIE: was PIE rich in morphology (as is the case, mainly, of Greek and Indo-Iranian), which has then been ‘reduced’ or ‘lost’ in the other languages, or was it rather poor in morphology, in which case the complex morphology of Indo-Iranian and Greek is the result of parallel, shared innovations, rather than of genetic inheritance?...Still on the issue of the ‘borrowability’ of grammar, it has been claimed at times that the IE morphological correlations are, on the whole, similar enough to be considered valid correlations but different enough so as not to raise the suspicion that borrowing might have been involved. However, certain IE grammatical forms typically reported in textbooks as ‘obvious’ examples of genetic inheritance – such as the paradigm of the verb ‘to be’, or ‘to bear, carry’ – are so similar, if not in some forms identical across the area, that the suspicion of borrowing may indeed arise. In fact, one would normally expect much more divergence from a long process of inheritance and development. ...In addition to this, one should take into consideration the numerous morphological correlations which supposedly connect the IE family with other contiguous, but different language families, as argued for by the supporters of the so-called macro-families...| The two suggested examples, the verbs ‘to be’ and ‘to bear, carry’, illustrate the difficulties encountered in concocting and dissecting the IE theory. Both words are not only shared with Türkic, they are shared paradigmatically, attesting to a common genetic connection. Without a demographic aspect, the suspicion of borrowing may indeed arise, and be never solved. Add the demographic aspect, and the linguistic genetic connection becomes a natural result of the demographic preponderance, of the population replacement, subjugation, and amalgamation that supplanted the diverse local languages with a feature typical for the Sprachbunds, an areal feature shared across numerous dissimilar languages. That is a birth of the IE unity that millenniums later occurred, in a vague and mushy form, to the European linguistic explorers. |

Traditionally linguistic kinship was identified on the basis of diagnostic evidence which is grammatical and combines structural paradigmaticity […] and syntagmaticity with concrete morphological forms. The Indo-Europeanists’ intuitive feel for what was diagnostic evidence of relatedness corresponds to a computable threshold of probability of occurrence […]. A grouping can be regarded as established by the comparative method if and only if it rests on individual-identifying evidence | Nichols makes a smooth but loaded connection between intuition and computable science. The role of intuition in science, called “subliminal thinking” in other spheres, is undeniable, in IE linguistics it implies an innate knowledge of native language. The opposite side of that is that a linguist without innate knowledge of the native language has no intuition, and thus can't progress from a superficial knowledge of the language to “computable threshold of probability of occurrence”. The subliminal thinking is also called “vision”, and, unfortunately, Indo-Europeanists without an innate knowledge of the alien language have no vision, they are Indo-Europeanist functionaries, not Indo-Europeanist visionaries. The fate of such functionaries is self-digging predicated by inability to perceive life beyond the horizons of their knowledge or absence thereof. The circularity, speculation, propaganda, beliefs, and other traits of the IE linguistics are logical consequences of a life in an eggshell. |

50The following data, as proposed by Nichols herself (1996a: 47), are among the most quoted ones for the purpose of this discussion (notice that to the Latin and Greek endings reported in this table at least the corresponding Sanskrit endings should be added to complete and strengthen the picture...)| It is not clear why paradigmaticity is of the Latin and Greek, which share a continuous historical and demographical common past, plus the missing Sanskrit, carried from the same Mediterranean area to India. What's wrong with the other 457 IE languages, why are they abandoned, and why not to address all 460 languages claimed by the IE family theory? This kind of evidence does not rate above anecdotal evidence. It is a partial anecdotal evidence that looks at two traits out of extended list of the grammatical traits. It is a selected partial anecdotal evidence because it looks at some selected parameters. Except for a propaganda moment, there is nothing to be the most quoted evidence. As such, it does not reach to the level of phrenology or Biblical Genesis story. It is no different than pulling, say, R1a Y-DNA genetic marker, because it is prominent among Indian brahmans, and pronouncing that all carriers of that haplogroup are Aryans or modern offsprings of the Proto-Aryans. |

51, 52

...Di Giovine... argues that looking at the issue in simple, binary terms of ‘archaism’ vs ‘innovation’ does not lead anywhere, since the status of the IE verbal system is much more intricate and subtle than this dichotomy would lead us to believe. All this, once again, ties in with, and lends support to, the well known fact that a clear-cut IE family tree is still difficult to draw, both at the phonological and morphological level (This problem emerges again in the various IE ‘philogenies’ attained through ‘cladistic’ techniques). ...Drinka insists that areal / contact models of interpretation have to be adopted in addition to, or, actually, incorporated into, the traditional paradigm: only an integrated, three dimensional model (“an amalgamation of family tree and wave models”) can “explain” the nature and distribution of the correlations found among the IE languages...Whatever the case, one has to admit and reflect on the fact that the morphological reconstructions are essentially based on a few core languages, whose morphological correlations – whether the result of archaism, or innovation, or borrowing, or convergence – are nevertheless well attested, whilst “the attribution of the other (so called “IE”) languages to the (“IE”) family is necessarily done on partial evidence”...| The term “necessarily” is a misnomer, since the “partial evidence” is intentionally selected evidence to fit suitable material into the predestined model and ignore the rest of the language, at times including its most basic traits. |

531. a chain of (at times unverifiable) assumptions, including syncretism and reshaping through analogy;

2. a chain of (at times unverifiable) intermediate reconstructions and alternating forms;

3. a chain of minor but frequent (and, at time unverifiable) language-specific sound changes,

4. if any of these procedures fail, there is always the possibility of giving different interpretations to the internal structure, function and origin of the case endings themselves.

54 3. 5. Counter evidence within morphologyIt has been argued above that the morphological evidence on which the IE theory is founded appears to be rather ‘malleable’, this problem being caused by the general lack of criteria and guidelines on how to evaluate morphological correlations. This in turn means that it is equally difficult, if not impossible, to identify evidence potentially counter to the model (with perhaps the only exception of the evidence from languages in contact that wholesale morphological paradigms can be borrowed). For example, the absence of the fundamental IE category of feminine gender in Anatolian23 could be considered a paradigmatic example of the inability on behalf of the IE theory (and the methods of historical linguistics in general) to make very clear-cut, testable predictions. There have been no claims (as far as we know) that the absence of this ‘diagnostic’ category should be classified and set apart as potential evidence counter to the IE origin of Anatolian (Hittite, for example, has no nominal declension corresponding to the feminine stems). Quite the contrary, efforts have been devoted only to finding traces of the feminine gender here and there or to justify its absence in the most plausible, natural way... The same could be argued with regard to one of the most puzzling aspects of Hittite verbal morphology, the ‘qi-conjugation’, which, admittedly, does not easily slot into any reconstructed category of IE (although there are claimed to be some good lexical correspondences between verbs adopting this conjugation and verbal roots in other IE languages...). The situation does not appear to be much different at the level of morpho-phonology, as is evident from the state of the research regarding the IE Ablaut (vowel alternation / apophony) (A vowel whose quality or length is changed to indicate linguistic distinctions (such as sing sang sung song). Here, the scanty and irregular distribution of vowel alternations across the IE area has generated an array of complex, sophisticated explanations, none of which however appears to be either testable or satisfactory... Carruba suggests that the original function of Ablaut is to be sought in the ‘deixis’ – a rather archaic, elementary function, but a very productive one within IE.

55 He ascribes the poor attestation of coherent patterns of vowel alternations across the IE area to the very ancient origin of phenomenon itself. This is certainly a plausible explanation; however, again, there may be alternative explanations. For example, it could be argued that the Ablaut present in Sanskrit (and partially in Greek), does not represent a phenomenon to be traced back to the IE proto-language, but on the contrary, a language-specific phenomenon. ...Sanskrit would be the only IE language that has roots and a “proper vowel gradation”. ...‘statistical significance’ (or lack of it) of the present vs perfect vowel alternation...3. 6. Is there hard core evidence at the foundation of Indo-European?Bearing in mind the shortcomings of the morphological correlations as discussed above, it is understandable how several scholars, such as Campbell (2003a & b) and Morpurgo Davies (Cambridge Seminar 2005; see note [19]) have reiterated and emphasized the role of the phonological (/lexical) correspondences for the purpose of assessing genetic relations. One could compare also the case of Proto-Dravidian, where it is the lexicon that has seen the greatest amount of relevant, comparative work, as illustrated by Steever (1996). As a matter of fact, phonology has at times offered us the possibility of testing the validity of the comparative method, in the sense that some predictions made by the comparative analysis have subsequently been proven correct in connection with the discovery of new linguistic material. For example, new evidence from Hittite and Linear B Mycenaean has confirmed the validity of earlier reconstructions, in this way also allowing us to redefine the processes which lead to the attested languages...

56These are undoubtedly remarkable discoveries, and fine analyses. However, the data and analyses under discussion are not void of difficulties... Furthermore, one could observe that the more linguistic material, the more comparanda one brings into the equation whilst doing comparison, the easier it is to find a phonological /lexical (as well as morphological) match with a given form or reconstruction. As Campbell (1998: 277) puts it, referring to the issue of mass-comparison and macro-families: “The potential for accidental matching increases dramatically … when one increases the pool of words from which potential cognates are sought or when one permits the semantics of compared forms to vary even slightly”... Hock (1993:221ff.) observes the following: “Preliminary results [of an experiment in which English, Finnish and Hindi are compared] suggest that enlarging the data base does not improve the reliability of the method. In fact, if there is any change at all it may consist in a slight increase of false friends”. On the other hand, Hock (ibidem) also recognizes that working through a comparison of only a small number of languages (three in the specific case), may be equally misleading.Finally, one could always argue that a few instances of fulfilled predictions – the occurrence of the right, predicted reflex at the right place – are not enough to prove the supposed predictive nature of all the conventionally established IE laws.As to the laryngeal theory, it is undeniable that it represents one of the most outstanding examples of a successful theory within historical linguistics. As Andersen (2007)30 puts it: “From a purely algebraic theory in Saussure; given putative phonetic justification by Hermann Moeller; then actually justified by the discovery of some of the posited segments in Anatolian; found to correlate with the 'prothetic vowels' and 'Attic reduplication' in Greek, and of 'final lengthening' in Homer; and then with the Baltic and Slavic distinction between acute and circumflex long vowels and diphthongs”.

57Nevertheless, the laryngeal theory is not uncontroversial, at least with regard to the number of laryngeal segments to be postulated. ...However, the main problem associated with the laryngeal is that the advantages attained by making recourse to the laryngeal theory are counterbalanced by a number of disadvantages. For example, Winter (1990: 20-1) referring to Saussure’s original idea of the ‘coefficient sonantique’ and subsequent developments, describes one of the known ‘disadvantages’ of the laryngeal theory as follows: "We attempt to simplify our statements by subsuming overtly differing phenomena under one common formula which may or may not require positing directly unattested elements conditioning the differences [….]. This analysis had the tremendous advantage that now all subtypes of ablaut in Proto-Indo-European could be treated alike and that canonical forms of roots could be set up; along with this, however, went the disadvantage that the Proto-Indo-European system of vowels apparently had to be reduced in an unreasonable way."Sihler (1995:111 ff.), who reconstructs an Ablaut system “considerably leaner” than others thanks to the support of the laryngeal theory, appears to (implicitly at least) identify another, major ‘disadvantage’. In fact, he states that the economy of his model is achieved by “a complication elsewhere in the system”, because his reconstruction also requires “a number of sound laws” applying to the postulated laryngeals. Here, the fundamental questions (which have not been asked yet, to our knowledge) are:

a) how many more sound laws do we need to make the laryngeal system work?

b) is this extra number of segments and required operating rules added to the system as high as to nullify the otherwise attained benefits?

58Thus, if we accept the analyses, objections and counter objections expounded thus far, it is still not clear what exactly the uncontroversial, hard core evidence that lies at the foundation of the IE theory is supposed to be....Last, but not least, one should take into consideration also those further limitations of the comparative method as pointed out in recent years by scholars such as Dixon (1997), Aikhenvald & Dixon (2001) and Nichols (1992, 1993/1995, 1996b, 1997 & 1998); see also Andersen (2006). These are:

a) the inability of the method to get at a more remote linguistic prehistory than the generally assumed 8000/6000 years);

b) its inability to account for the actual distribution of the degree of linguistic ‘diversity’ vs linguistic ‘uniformity’ found in the world....4. Is there a pre-historical reality behind reconstructed Indo-European?4. 1. Conventionalism vs realismThe ‘conventionalist’ vs ‘realist’ approach to linguistic reconstruction, and related concept of proto-language (in general as well as within IE), is another long standing debate within historical linguistics, and one for which, yet again, there does not appear to be much of a consensus... It is true that between the extreme conventionalist approach on the one side and the full realistic approach on the other there are plenty of more moderate, intermediate positions. Nevertheless, it appears that the fully realistic approach, which in turn is based on the controversial method of palaeo-linguistics, is the one that has so far attracted many supporters, and not only among archaeologists (such as Mallory (1989 & 2001) and Renfrew [1987, 1990]), but also among linguists.For example, in his criticism to the thesis by Gimbutas (1970) regarding the location of the IE home land, Schmitt (1974: 283) observes that “[with] the methods of linguistic paleontology anything can be proved as Proto-Indo-European, but it can not be proved as typically Proto-Indo-European”. Thus, Schmitt appears to have confidence in the validity of the realist approach, although he has doubts regarding the factual interpretation of single reconstructions and the hasty conclusions reached about the reconstruction of single ‘pre-historical facts’. It could be said that in this case too (like in the case of the ‘regularity principle’) it is not always made explicit what the motivations are, what the evidence is, that provides the basis for the choice of one approach, or the other.| The case with Gimbutas theory is illustrating. The archeologist confused two demographic movements, the westward movement of the Türkic Kurgan people, marked by male R1b Y-DNA, with the eastward movement of a hodge-podge of the European people, marked by a soup of the European male Y-DNA, groups G, J, I, and R1a. The two counterflows were separated in time by a full millennia, first the westward expansion of the Kurgan people (First Wave in Gimbutas' nomenclature), and then the eastward flight of the “Old Europeans”. Naturally, the European traces overlaid those of the Kurgans. Thus, in the late archeologist's eyes, the European farmers gained the attributes of the Kurgan nomads, and from a mass of cart-riding refugees turned into Kurgan rider conquerrors of Europe. Gimbutas was right in detecting European farmers in the Eastern Europe of the time, but wrong in the interpretation of a transit point as a (linguistically) Indo-European homeland. The European refugees ended up as upper castes in India (R1a), a variegated human mass in the Caucasus (G, J), and repatriants to the Europe (I). |

| Di Giovine is right, the IE verbs are akin to Belgian verbs, they originated in two (actually, many more) different phylа, and just happened to occupy the same spatial and temporal location. If a potato salad is taken as a model for the IE verbs, and scholars would study the amalgamated salad vegetables, they would come to the same conclusions as did Di Giovine: potatoes and cucumbers are not compact, and they even do not speak the same vegetable language at all. They must be cooked differently, they complement each other, and they can be swallowed in a single bite. |

2. Why, how, when and in which direction did the original proto-community disintegrate and migrate / spread, so as to bring about the distribution of the IE languages as we found them in historical times?

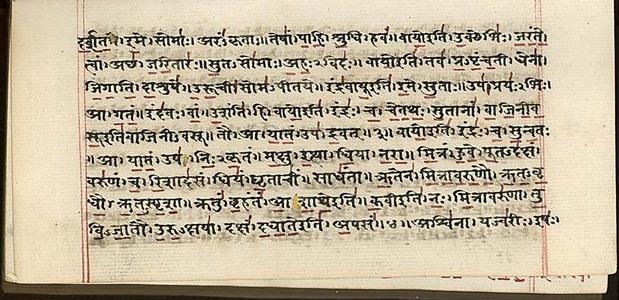

3. How old is Old Indo-Aryan? Is it as old as the traditional IE theory claims (about 1700/1500 BC), in line with the ‘migrationist’ model, or is it much older than that, in line with the ‘indigenist’ model? In turn, these questions are connected with the following major issue (already touched upon above):

4. Is Old Indo-Aryan the most archaic, and therefore, the most important language for the purpose of reconstruction?The issues raised in points (3) and (4) are of particular relevance, not only because they are strictly connected to the home land issue, but also because the assumption of the great antiquity of (Vedic) Sanskrit is (or, at least, it has been) one of the pillar tenets at the foundation of the IE theory, and related traditional reconstructions. As we have seen above (par. 3. 3.), this tenet is now under attack, since several scholars believe that the Greco-Aryan morphological paradigm represents in fact innovation, and not archaism. As to the more specific issue of the archaicity of Sanskrit, Schmitt in this volume calls into question this traditional view, arguing that:

60“the archaism particularly of the Old Avestan language makes it only too clear that, despite the old age of the earliest Vedic texts, the Old Indo-Aryan language is not the only fundament of the IE proto-language […] and that its data are not with absolute necessity genuinely antique; therefore Old Indo-Aryan (both Vedic and Sanskrit) is not so close to PIE as many people think”.On the other hand, Kazanas... supports the traditional way of thinking as well as the indigenist model claiming exactly the opposite: Old-Indo-Aryan is indeed the oldest language within the family (actually, much older than conventionally assumed), as well as the closest language to PIE, even though a PIE language cannot be reconstructed. In turn Drinka, in her contribution to this volume, rejects the indigenist / ‘Out-of -India’ model, arguing against it (mainly) on the basis of those very “archaic” morphological isoglosses Indo-Aryan shares with some IE languages and those very “innovative features” it shares instead only with Iranian and Greek.4. 3. Sanskrit and the South Asia linguistic areaThis already articulated debate is in turn connected with the other, equally tangled issue of how to interpret the lexical, phonological, structural and even morphological correlations that have been identified as existing between the Old (and Modern) Indo-Aryan languages and the other non IE languages of India, such as (mainly) Dravidian and Munda. In fact, these (and other) various languages / language families of India are widely claimed to form what is usually referred to as the ‘South Asia linguistic area’, for which see Steever (1993:10 & 1996:11 ff.); Masica (1976) and Emeneau (1956, 1971 & 1980). In particular, on the basis of (supposed) lexical borrowing from Dravidian into Indo-Aryan and from the modern geographical distribution of the Dravidian languages, it is often claimed that Dravidian and Indo-Aryan must have been in contact – since prehistoric times– in those extreme northwestern areas of India first inhabited by the Indo-Aryans...Thus, the relevant question here, the question which has been hotly debated and whose resolution, if ever attained, could help to break the deadlock of the indigenist vs migrationist model – together with the issue of the degree of antiquity of Sanskrit – is the following: Are the non IE features present in Old-Indo-Aryan the result of sub-stratum, super-stratum, ad-stratum, convergence, or even genetic inheritance?...Several scholars... have compiled long lists of (Rig-) Vedic words believed to be of Dravidian or, more generally of non-Aryan origin. Other scholars, particularly Hock (1996: 36 ff.), have drawn attention to the fact that the situation is not that clear-cut after all. In fact, in many instances it is difficult to trace back the origin of the lexical as well as structural similarities observed in this intricate linguistic area, and to sort out whether they are attributable to borrowing, convergence, or chance resemblances. On the other hand... Indian scholars... challenge the traditional classification of Sanskrit as an IE language, observing that under a different socio-politico-cultural context, the similarities under discussion could have been interpreted differently...The following selection of Turkisms and Türkic substrate in English cites instances when IE etymology appeals to Sanskrit to establish IE attribution. Selection provides some statistical insight, it plucked 60 Turkisms out of the body of 700 entries, giving about 10% of Türkic content in Sanskrit. In respect to Sanskrit, the sampling is random, since the content of Turkisms in English is independent from the content of Turkisms in Sanskrit, or of Sanskrit loanwords in Türkic. The number 10% is however a very rough approximation, being dependent on the number of factors that influenced the sources. First and foremost is the poor appearance of Sanskrit cognates in the IE etymological exercises: the citing is spotty, only to the degree needed to establish connection to a predestined target; just that variable may underrepresent reality by a factor of 2 or 3, potentially raising proportion to 20-30%. Then there is a loose treatment of semantics, when Sanskritisms are cited inappropriately (Cf. janiṣ is cited for both “queen” and “wife”, the “wipes off”̣ is cited for “milk”, “bewail” for “call”, the avasám “food” for “oat”, etc.); that is falsely inflating the proportion. The presence of Sanskritisms in Türkic also inflates the proportion, since although they entered English as Turkisms, etymologically they originated with Sanskrit; these are terms of Buddhist lexicon that grew on the Indian soil and were brought to English at about the turn of the eras as the Türkic substrate. These cases are few, but with the small sample of 60 items they need to be considered. Then there is a case of erroneous attribution to Turkisms; the questionable cases also inflate the proportion by as much as 1/3. Adjusted for these factors, the proportion of Turkisms in Sanskrit may be reasonably assessed as to be close to 15%. The presence of the basic vocabulary that could not have been introduced by the demographically inferior Indo-Saka, Indo-Scythians, Huns, Kushans, Ephthalites, and later migrants, attests to a time depth of these loanwords ascending to the middle of the 2nd mill. BC, the time of the initial migration of the Indo-Aryan farmers to the South-central Asia.

| English | Sanskrit, Avesta (Av.) | Türkic | English | Sanskrit, Avesta (Av.) | Türkic |

|---|

| 1 | anger (v.) | aihus, aihas, Av. azah- “need” | özak (adj.) | I (arch. ic) | ah(am) | ič (es) | | 2 | at(prepos.) | adhi “near” | at- (v.) | juice | yus- “broth” | jü | | 3 | aurora | eos, usah ausra “dawn” | yaruk | kin | janati “begets, bears”, janah “race”, jatah “born” | kin/kun/kün | | 4 | axle | aksah | i:k | lull (v.) | lolati | ulï- (v.) | | 5 | bake (v.) | pakvah “cooked” | bukaç | mantra | mantra-s “sacred message or text, charm, spell, counsel” | maŋra- (v.) | | 6 | band (v. & n.) | bandhah | ba- (v.) | me (pron.) | Skt., Av. mam | min (pron.) | | 7 | be (v.) | bhavah “becoming”, bhavati “becomes, happens” | buol- (v.) | mead | madhu “honey, honey drink, wine”, Av. maδu | mir | | 8 | bear (v.) | bhárāmi | ber- (v.) | milk | marjati “wipes off” | meme | | 9 | bode (v.) | bodhi | bodi | mind | matih “thought, mind” | ming | | 10 | bow | bhujati | boq-(v.) | oat | avasám “food” | ot | | 11 | bursary | buddha sangha, | bursaŋ | ogle (v.) | akshi “eye” | ög- (v.) | | 12 | call | garhati “bewail, criticize” | qol | otter | udrah, Av. udra | ätär | | 13 | candle | cand- “to give light, shine”, candra- “shining, glowing, moon” | kandil | pot | patra “bowl” | patır | | 14 | cap | kaput- “head” | kap | purge (v.) | pavate “purifies, cleanses”, putah “pure” | pür- (v.) | | 15 | cow | gaus | coy | queen | janiṣ “wife, woman”, gna “goddess”, Av. jainish “wife”, gǝna-, ɣǝna, ɣna, ǰaini “woman, wife” | yeŋä | | 16 | crust | krud- “make hard, thicken” | kairy | regal (adj.) | raj- “king, leader” | arïɣ (adj.) | | 17 | day | dah “to burn” | dün | sapphire | sanipriya “dark precious stone” | sepahir | | 18 | din | dhuni “roar” | tоŋ | sari | sati “garment, petticoat” | sarïl (v.) | | 19 | ea (OE) | ap “water” | aq- (v.) | sew (v.) | sivyati “to sew” | sač- | | 20 | Earth | thira | Yer | sinew | snavah, Av. snavar “sinew” | siŋir | | 21 | eye | akshi | ög- (v.) | sip (v.) | sabar- “sap, milk, nectar” | syp (v.) | | 22 | fart | pard | burut- (v.) | smile (v. and n.) | smayatē, smayati, smēras, smitas | semeye (v.) | | 23 | fire (v. & n.) | pu | bur- | son | sunus | song | | 24 | fissure | bhinadmi | öz | stair | stighnoti “mounts, rises, steps” | šatu | | 25 | foot | pad-, Av. pad- | but | suture | sutram “thread” | sač | | 26 | chintz | chint | čit | tree | dru “tree, wood” | terek | | 27 | cook | pakvah “cooked” | kok- (v.) | turf | darbhah “bale of grass” | ter- (v.) | | 28 | gene | janati “begets, bears”, janah “race”, janman- “birth, origin”, jatah “born” | ken- | ululate (v.) | lolati | ulï- (v.) | | 29 | go (v.) | gjihite “goes away” | git | was | vasati | var- (v.) | | 30 | herd | sardhah | kert | wife | janiṣ “wife, woman”, gna “goddess” | ebi |

|

| The last comment (Clackson 2007: 3) says it all: Catholics have to be convinced of the absence of Catholicism, idealists have to be convinced of the absence of their ideals, and IE linguists have to be convinced of the absence of IE family. That simple. That reminds us that after the the sputnik's flight around the Earth, and after the Apollo's flights to the Moon, a sizable community trusted their leaders that that is all Hollywood trickery staged in Universal City to debase the faithful. Anybody can see that the Earth is flat: put a ball on the football field, and it does not roll off. |

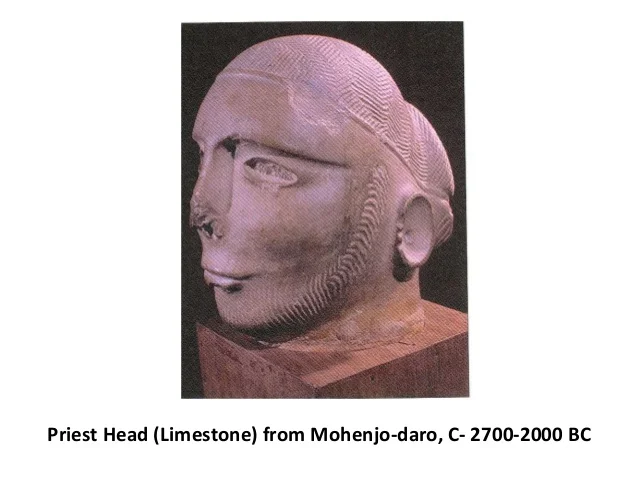

62...the explanation of the spread of the Indo-European languages as “the spread of the culture of a concrete group of people from a cradle […] has not been proved by anthropology and archaeology as yet”... ...“all attempts to reconstruct the old culture of the Indo-Europeans as existing in a concrete cradle, by the means of ‘linguistic paleontology’ are wrong”....scholars are faced here with yet another area of IE studies where the ‘evidence’ (or lack of it) is malleable and un-decisive. As a matter of fact, Häusler himself believes that “the IE linguistic community must have existed at some point in ancient times, since the linguistic classification has been fairly safely established, even if this (assumed) linguistic community is not at all retrievable by the means of archaeological and anthropological research”... Whatever the case, the fact remains that, thus far, the required, supporting (one way or the other) archaeological and palaeo-anthropological evidence has not been found.Since the 2009 publication of this work, and its cited publications of 1997, 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2004, things have changed. A new method was developed and validated in genetics to date haplogroups assembled on a phylogenic diagram. The method allowed to trace migration flows from Central Europe to Eastern Europe, and on to South-central Asia. These migrations were validated over and over by independent sampling and independent analyses. The peoples' movement is beyond doubts; the doubts relate to the cultural and technological innovations carried by the migrant peoples, their definitions, their propagation, and their timing. The paleogenetic revolution brings to reality the innate beliefs of the IE Theory and Out-of-India pundits. Both sides are right in accusing the other party to be laughably wrong.Further clarifications on the migration of the Indo-Aryan farmers will be produced by analyses of phylogenic trees for accompanying haplogroups complimentary to the well-understood R1a group, particularly the Y-DNA of the upstream groups R and R1, and the pre-exodus Central European haplogroups I, J, and G. Some branches of the above haplogroups, taken from the same sample material, must return the date already received for the R1a haplogroup, first to corroborate the dating determined for the R1a haplogroup's Indo-Aryan branch, and secondly to narrow the spectrum of the haplogroups that the Indo-Aryan farmers brought over to the Hindustan peninsula.

Probably the most important finding of the haplogroup dating methodology is the finding corroborating postulations of the “Circumpontic” hypothesis (Merpert, 1974, 1976) and “Kurgan theory” (Gimbutas, 1964, 1974, 1977, 1980) about the importance of the Eastern Europe in the evolution of the “Indo-European” languages within the framework of the “Indo-European homeland”, albeit without their fancied allusions to the “Indo-Europeans”, but with evolutionary perspective on the migratory processes that had the Eastern Europe as one of the staging stations for the asynchronous counter flows from the Central Europe to the South-central Asia (3rd mill. BC) and from Asia to the Atlantic (starting at 5th-4th mill BC). Unwittingly, Gimbutas had conflated separate migratory events in opposite directions and a millennium apart. The horse was domesticated in the Northern Kazakhstan, a nomadic wave that brought domesticated horse to the Eastern Europe created conditions underlying the Gimbutas'“Kurgan theory”. The migration stipulated within the “Anatolian” (or “Neolithic Gap”) theory (Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, 1980, Renfrew, 1987, Safronov, 1989, Gray and Atkinson, 2003) is a specific episode of the Eastern European parallel path traversing Anatolia to reach the Balkans and Iberia, the “Anatolian theory's” Urheimat results conflict with Anatolia's role as a migratory corridor for particular migrants at a particular time. Within a larger framework, having accounted for the ample reverse migrations, and freed from the parochial biases of the “Indo-European homeland”, the theories' data is largely consistent with the linguistic and migratory processes. |

| The genetic conclusions (unlike their historical interpretations) drawn before 2010 suffer not from incorrect data, but from an absence of reliable dating theory and practice. There, again, a blind trust of other discipline's authorities, who happened to act on intuition instead of empiric data solely because no reliable scientific methods exist yet, raises a cottage industry of patriotic contenders. |

63, 645. Introduction to the chapters (in alphabetical order) (Introduction to the chapters illustrates points of the general observations with specific contents of the contributors. Although immensely interesting in their depth and detail, they are not cited in this posting)

65, 66, 67, 68, 69

Chapter X. The main thesis of Angela Marcantonio’s chapter: Evidence that most Indo-European lexical reconstructions are artefacts of the linguistic method of analysis, is that the methods of historical linguistics, including the comparative method, can be so flexible – by their very nature – that they can be stretched to account for almost any data. This means that the explanatory system runs the risk of becoming dangerously circular, and, therefore, of yielding misleading results – in this case within the field of IE studies. Over the course of about two hundred years of everyday practice of reconstruction within IE the encountered counter-evidence has been typically ‘explained away’ through all sorts of (often ad-hoc) justifications, so that today one can find hardly any evidence counter to the model. The Author examines this ‘explaining away’ process critically, by asking the question: have we fitted the IE data to the model, or have we made the model so flexible that it can fit almost any data, including potential counter evidence? Marcantonio analyzes the full comparative corpus of the verbal root reconstructions contained in the most recent IE etymological dictionary (LIV), by adopting simple, quantitative methods of analysis. She argues that the great majority of these reconstructed roots lack the required ‘statistical significance’, the required ‘cumulative effect’. As a consequence, the cognates relating to these roots are to be interpreted as ‘similarities’, rather than ‘correspondences’; in turn, these similarities can be interpreted as instances of ‘chance resemblances’....Marcantonio also argues that adding laryngeal segments to the process of reconstruction (whatever the rights and wrongs of the laryngeal theory may be), dangerously increases the explanatory power of the comparative method, in this way further contributing to the flexibility of the overall explanatory model....

70, 716. ConclusionThe reader has seen... a variety of views about IE, ranging from the belief that it represents the language of a real pre-historical community; through the thesis that it is only a model to embody linguistic correlations; all the way to statistical evidence that (many) linguistic correlations themselves may be merely an artefact of the method of analysis. In fact, when the various components of the theory are brought together so that they can be seen holistically, it is hard to pin down what the foundations of the theory are actually supposed to be.For example, one of the founding principles of the traditional version of the theory was the assumption that morphological paradigms cannot be borrowed, and therefore it is possible to trace genetic inheritance through them. However, we have seen evidence of wholesale paradigm borrowing, based on studies of languages in contact. In any case, some scholars now hold that morphology is less relevant than other factors – but it is at present unclear whether, or how, these other factors may be verified or falsified...

72-87References(all references are intentionally omitted in this posting. Refer to copyright holders www.jies.org, http://www.federatio.org/joes/EurasianStudies_0115.pdf for omitted information)

|

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.

"

"

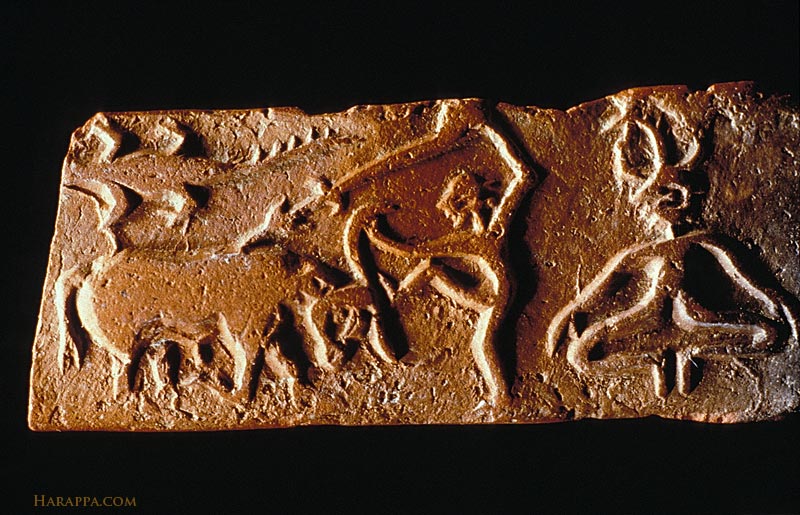

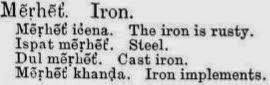

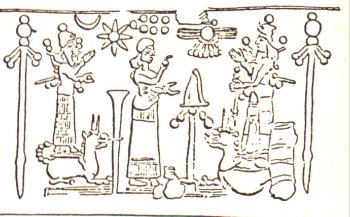

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

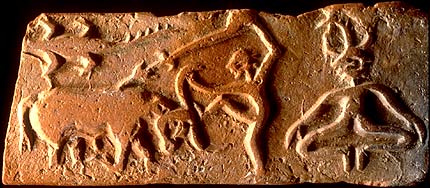

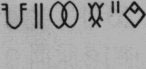

Seal. Kalibangan K-50

Seal. Kalibangan K-50

![[âIMG]](http://murugan.org/research/valluvan3_files/image003.jpg)

: rim of jar Rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇi supercargo' karNika 'helmsman, merchantman, scribe, account'

: rim of jar Rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇi supercargo' karNika 'helmsman, merchantman, scribe, account'

(E. Douglas van Buren.

(E. Douglas van Buren.

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

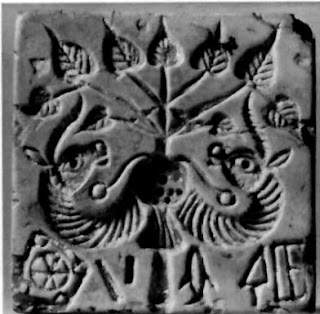

One side of a triangular terracotta tablet (Md 013); surface find at Mohenjo-daro in 1936. Dept. of Eastern Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

One side of a triangular terracotta tablet (Md 013); surface find at Mohenjo-daro in 1936. Dept. of Eastern Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

m0453 . Scarf as pigtail of seated person.Kneeling adorant and serpent on the field.

m0453 . Scarf as pigtail of seated person.Kneeling adorant and serpent on the field. Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

m1181. Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated on a hoofed platform.

m1181. Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated on a hoofed platform.

Pot with a bull and pipal

Pot with a bull and pipal

This unique well and associated bathing platform was discovered in the course of building a catchment drain around the site. It was reconstructed on the ground floor of Mohenjo-daro site museum.

This unique well and associated bathing platform was discovered in the course of building a catchment drain around the site. It was reconstructed on the ground floor of Mohenjo-daro site museum.

(Mohenjo-daro DK 6847, Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.295, Mackay 1938: pl. XCIV, 430; pl. XCIX, 686a).

(Mohenjo-daro DK 6847, Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.295, Mackay 1938: pl. XCIV, 430; pl. XCIX, 686a).