https://tinyurl.com/y784w2nb

To Karl Popper is attributed a logical postulate that a hypothesis in the empirical sciences can never be proven or verified, but a hypothesis can be falsified, meaning that it can and should be scrutinized by decisive experiments.

This 'falsifiability' postulate is restated as follows: a hypoethesis can never be independently verified but can be falsified by empirical evidence of experiments.

This is particularly true of hypotheses related to the underlying language and the purport/meaning of Indus Script inscriptions which are read as Meluhha language/speech hypertexts (composed of pictorial motifs and hieroglyphs).

How to validate the decipherment of Indus Script hypertexts in the absence of Rosetta stone or the Canopus Decree (two inscriptions which contained the same message in three scripts including Egyptian hieroglyph)?

One approach is the suggested approach of 'falsifiability' proposed by Karl Popper to falsify a hypothesis that Indus Script is in a Non-Mleccha language. Cypro-Minoan is a non-Meluhha language and this monograph falsifies the hypothesis that the Indus Script hypertexts on four pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa are written in a non-Mleccha language. So,the language is NOT Cypro-Minoan. The language is Meluhha, acording to my hypothesis proven with evidence of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions in 3 volumes.All the 8000+ hypertexts are read as metalwork wealth accounting ledgers rendered in Meluhha speech [Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union)]

![]()

![]()

I present evidence in this monograph that the hypothesis related to any Non-mleccha as the underlying rebus language of Indus Script hypertexts can be 'falsified' by empirical evidence.

The hypothesis that the hypertexts on four tin ingots found in a Haifa shipwreck signified Cypro-Minoan writing has been falsified. After the publication in 1977, of the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck at Haifa, Artzy published in 1983 (p.52), two more ingots found in a car workshop in Haifa which wasusing the ingots for soldering broken radiators. Artzy's finds were identical in size and shape with the previous two; both were also engraved with two marks. In one of the ingots, at the time of casting, a moulded head was shown in addition to the two marks. Artzy compares this head to Arethusa. (Artzy, M., 1983, Arethusa of the Tin Ingot, Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research, 250, p. 51-55). Artzy went on to suggest the ingots may have been produced in Iberia and disagreed with the suggestion that the ingot marks were Cypro-Minoan script. The author Michal Artzy (opcit., p. 55) showed these four signs on the four tin ingots to E. Masson who is the author of Cypro-Minoan Syllabary. Masson’s views are recorded in Foot Note 3: “E. Masson, who was shown all four ingots for the first time by the author, has suggested privately that the sign ‘d’ looks Cypro-Minoan, but not the other three signs.” Thus, three of the four signs were NOT Cypro-Minoan according to the known Cypro-Minoan syllabary.

The thesis of this monograph is that mleccha म्लेच्छ is a form of Proto-Indian आर्य-वाच् (Arya speech) traceable from the metalwork, artisanal, seafarer lexis of Aratta in Gujarat as a representative region of Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union of ancient India) of ca. 4th millennium BCE. This civilizational indicator of language expressions related principally to metalwork, coincides with the participation of Bhāratam Janam (RV 3.53.12) in the Tin-Bronze revolution. Bhāratam Janam linked Eurasia with Ancient Far East (the largest tin-belt of the globe in the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween), as evidenced by the sources of Mon-Khmer languages in Austro-Asiatic framework of speechforms in Munda languages of Bhāratam Janam. The perennial, glacial-sourced Himalayan rivers ground down granite rocks on the river basins and created the cassiterite (tin ore) placer deposits which were mined by tin-panners and mercantile transactions engaged in along the Indian Ocean and Himalayan river waterways by seafaring Meluhha merchants. The thesis is premised on a hypothesis (work in process) that this Ancient Maritime Tin Route pre-dated the Silk Road by about two millennia. This is a work in process because archaeometallurgical investigations are needed to trace the sources of tin used in Eurasia during the millennia of Tin-Bronze revolution from ca. 5th to 2nd millennia BCE. The navigable waterways provided by Himalayan rivers were subject migrations in palaeo-channels, caused by plate tectonic events. The ongoing plate tectonic event is the metaphor of tāṇḍava nr̥tyam,'cosmic dance' which indicates the Indian plate moving northwards at a majestic rate of 6 cm. per year jutting into and lifting up the Eurasian plate by 1cm per year resulting in the Himalayan dynamics.

The earliest literary citations to mleccha as speech/language occur in Manusmṛti, and Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (both texts datable to periods earlier than 3rd cent BCE). The lexis of Aratta can be reconstructed from the lexis of over 25+ ancient languages of Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union) presented in the Indian Lexicon organized in over 1240 semantic clusters. (Note. Please download file of size 29.7 mb).

Such word and expressions recorded in this Indian Lexicon explain rebus the Indus Script hypertexts and meanings inMeluhha speech forms.

மிழலை¹ miḻalai , n. < மிழற்று-. cf. mlīṣṭa. Prattle, lisp; மழலைச்சொல். (சூடா.)மிழற்றல் miḻaṟṟal

![]()

![]() Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum’s surface, Vietnam. Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id.(DEDR 5023) Rebus: mũh, muhã ‘ingot‘ or muhã ‘quantity of metal taken out of furnace’; मूका f. a crucible L. (= or w.r. for मूषा).

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum’s surface, Vietnam. Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id.(DEDR 5023) Rebus: mũh, muhã ‘ingot‘ or muhã ‘quantity of metal taken out of furnace’; मूका f. a crucible L. (= or w.r. for मूषा).

S. kaṅgu m. crane, heron (→ Bal. kang); kaṅká m. heron VS. Rebus: kang ‘brazier, fireplace’ (Kashmiri) kaṅká m. ʻ heron ʼ VS. [← Drav. T. Burrow TPS 1945, 87; onomat. Mayrhofer EWA i 137. Drav. influence certain in o of M. and Si.: Tam. Kan. Mal. kokku ʻ crane ʼ, Tu. korṅgu, Tel. koṅga, Kuvi koṅgi, Kui kohko]Pa. kaṅka — m. ʻ heron ʼ, Pk. kaṁka— m., S. kaṅgu m. ʻ crane, heron ʼ (→ Bal. kang); B. kã̄k ʻ heron ʼ, Or. kāṅka; G. kã̄kṛũ n. ʻ a partic. ravenous bird ʼ; — with o from Drav.: M. kõkā m. ʻ heron ʼ; Si. kokā, pl. kokku ʻ various kinds of crane or heron ʼ, kekī ʻ female crane ʼ, kēki ʻ a species of crane, the paddy bird ʼ (ē?).(CDIAL 2595)![]() Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.![]() maraka 'peacock' Rebus: marakaka loha 'copper alloy, calcining metal'.karibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron'

maraka 'peacock' Rebus: marakaka loha 'copper alloy, calcining metal'.karibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron'

Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id. (DEDR 5023) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot'

kanku 'crane, egret, heron' rebus: kangar 'portable furnace'

arka 'sun' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper', arka 'gold'.![]()

![]() Dong Song drum findings, Vietnam. Dong Song is a pre-historic Bronze Age culture which dominated the Far East as a continuum of the neolithic Hoabinhian stone tool industry of the Far East.

Dong Song drum findings, Vietnam. Dong Song is a pre-historic Bronze Age culture which dominated the Far East as a continuum of the neolithic Hoabinhian stone tool industry of the Far East. ![]() Indus Script hypertexts: 'face'

Indus Script hypertexts: 'face'

mũh

The inscriptions on two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa have been discussed in: Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Vol. 1, Number 11 (2010) — The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” By S. Kalyanaraman (Editor of JIJS: Prof. Nathan Katz)http://www.indojudaic.com/index.php?option=com_contact&view=contact&id=1&Itemid=8 (See embedded document).

milakkhu-rajana 'copper? dye' (Pali) Rebus: மிலேச்சமுகம் milēcca-mukam , n. < mlēccha-mukha. Copper; செம்பு. (யாழ். அக.) மிலைச்சம் milaiccam , n. < mlēccha. Vermilion; சாதிலிங்கம். (சங். அக.) म्लेच्छ 'copper, vermilion' (Monier-Williams) म्लेच्छ-मुख n. = म्लेच्छा*स्य L. = n. " foreigner-face " , copper (so named because the complexion of the Greek and Muhammedan invaders of India was supposed to be copper-coloured) L. (Monier-Williams) म्लेच्छ a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons L.; Rebus: Milakkhu [the Prk. form (A -- Māgadhī, cp. Pischel, Prk. Gr. 105, 233) for P. milakkha] a non -- Aryan Diii. 264; Th 1, 965 (˚rajana "of foreign dye" trsl.; Kern, Toev. s. v. translates "vermiljoen kleurig"). As milakkhukaat Vin iii. 28, where Bdhgh expls by "Andha -- Damil'ādi."; Milakkha [cp. Ved. Sk. mleccha barbarian, root mlecch, onomat. after the strange sounds of a foreign tongue, cp. babbhara & mammana] a barbarian, foreigner, outcaste, hillman S v. 466; J vi. 207; DA i. 176; SnA 236 (˚mahātissa -- thera Np.), 397 (˚bhāsā foreign dialect). The word occurs also in form milakkhu (q. v.); Milāca [by -- form to milakkha, viâ *milaccha>*milacca> milāca: Geiger, P.Gr. 622 ; Kern, Toev. s. v.] a wild man of the woods, non -- Aryan, barbarian J iv. 291 (not with C.=janapadā), cp. luddā m. ibid., and milāca -- puttā J v. 165 (where C. also expls by bhojaputta, i. e. son of a villager)..(Pali) மிலேச்சன் milēccaṉ, n. < milēccha Person speaking barbarous language; திருத்த மற்ற மொழியைப் பேசுவோன். (சீவக. 93, உரை.) மிலேச்சிதம் milēccitam , n. < mlēcchita. (யாழ். அக.) 1. Ungrammatical speech; இலக்கண வழுவான பேச்சு. 2. Non-Sanskritic language; ஸம்ஸ்கிருதமும் அதனுட்பிரிவான பாஷைகளும் அல் லாத பிறபாஷை.

आर्य--वाच् mfn. speaking the Aryan language मनु-स्मृति x , 45.; आर्य a master , an owner L.; a man highly esteemed , a respectable , honourable man पञ्चतन्त्र. शकुन्तला &c.

Source: The Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Manu, Calcutta: Sewell & Debrett, 1796.

Translation by .G.Buhler: X.43. But in consequence of the omission of the sacred rites, and of their not consulting Brahmanas, the following tribes of Kshatriyas have gradually sunk in this world to the condition of Sudras;

X.44. (Viz.) the Paundrakas, the Kodas, the Dravidas, the Kambogas, the Yavanas, the Sakas, the Paradas, the Pahlavas, the Kinas, the Kiratas, and the Daradas.

X.45. All those tribes in this world, which are excluded from (the community of) those born from the mouth, the arms, the thighs, and the feet (of Brahman), are called Dasyus, whether they speak the language of the Mlekkhas (barbarians) or that of the Aryans.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/manu/manu10.htm

Manusmṛti, 'reflections of Manu' is ancient legal text dated to ca. 2nd century BCE, among the many Dharmaśāstras of Hindu dharma. It is also referred to as Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. The Dharmasya Yonih (Sources of the Law) has twenty-four verses.

Manu notes (10.45):

mukhabāhūrupajjānām yā loke jātayo bahih

mlecchavācaś cāryavācas te sarve dasyuvah smr̥tāh

This shows a two-fold division of dialects: arya speech and mleccha speech. The language spoken was an indicator of social identity. In ancient Bhāratiya texts, mleccha, a Prākr̥tam, was recognised as an early speech form, a dialect referred to in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and Mahābhārata, a dialect which required a translator for a Mesopotamian transacting with a sea-faring Meluhha merchant of Saptasindhu region.

Mahābhārata refers to many groups of people such as: Sakas, Huns, Yavanas(Greek), Kambojas, Pahlavas, Bahlikas, Rishikas, Chinas(China). The text describes mleccha with "heads completely shaved or half-shaved or covered with matted locks, [as being] impure in habits, and of crooked faces and noses", as "dwellers of hills" and "denizens of mountain-caves. Mlecchas were born of the cow, Nandini, (belonging to Vasiṣṭha), of fierce eyes, accomplished in smiting looking like messengers of death, and all conversant with the deceptive powers of the Asuras". The text gives the following information regarding mleccha:

Amarakośa describes the Kiratas , Khasas and Pulindas as the Mleccha-jatis. In some ancient texts, Indo-Greeks, Scythians,and Kushanas were also mlecchas The Vāyu, Matsya and Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇas state that the seven Himalayan rivers pass through mleccha countries. Baudhāyana Sutra-s refer to a mleccha as someone "who eats meat or indulges in self-contradictory statements or is devoid of righteousness and purity of conduct." (reference citation not provided).

Ānava with variant pronunciations of words/expressions were located on frontiers of Āryāvarta in regions such as Gāndhāra, Kāśmīra and Kāmbojas.

Such Ānava could be in the lineage of Āmāvasu mentioned in: Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra (BSS) 18.45 and the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 11.5.1 which indicate the wanderings of lineage of Pururavas took place from Kurukshetra. Pururavas and Urvaśi had two sons, Āyu and Āmāvasu. According to the Vādhūla Anvākhyāna 1.1.1, yajña rituals were not performed properly before the attainment of the gandharva fire and the birth of Āyu who ensures the continuation of the human lineage that continues down to the Kuru kings, and beyond.

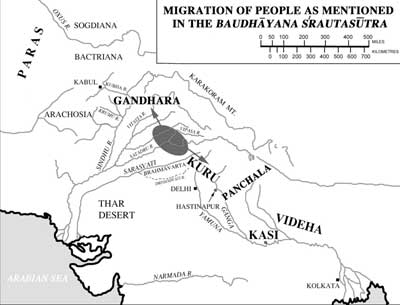

Clearly, Caland interpreted the passage to mean that from a central region, the Arattas, Gandharis and Parsus migrated west, while the Kasi-Videhas and Kuru-Pancalas migrated east. Combined with the testimony of the Satapatha Brahmana (see below), the implication of this version in the Baudhāyana śrautasūtra, narrated in the context of the Agnyadheya rite is that that the two outward migrations took place from the central region watered by the Sarasvati. (Kashikar, Chintamani Ganesh. 2003. Baudhāyana śrautasūtra (Ed., with an English translation). 3 vols. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass/IGNCA).

Ṛgveda hymn 6.61.9,12 says that 5 Aryan groups of people spread beyond the seven sister-rivers (sapta sindhavah)!

In volume III of his translation, on p. 1235, Kashikar translates the relevant sentences of the text BSS 18.44 as follows-

Baudhāyana’s Śrautasūtra 18.4 mentions two migrations of the Vedic people. One was eastward, the Āyava. The other was westward, the Āmāvasa, and this produced the Gāndhāris (Gandhāra and Bactria), the Parśus Persians and the Arattas (of Urartu and/or Ararat on the Caucasus?). Map showing the “seven rivers and Sarasvatī”; various sites with Harappan artefacts far from Saptasindhu; also the two movements eastward by Āyu and westward by Āmāvasu. Read more at: https://www.newsgram.com/vedic-sanskrit-older-than-avesta-baudhayana-mentions-westward-migrations-from-india-dr-n-kazanas

In an obscure study15 of the Urvashi legend in Dutch, he focuses on the version found in Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44-45 and translates the relevant sentences of text as (Caland, Willem. 1903. "Eene Nieuwe Versie van de Urvasi-Mythe". In Album-Kern, Opstellen Geschreven Ter Eere van Dr. H. Kern. E. J. Brill: Leiden, pp. 57-60).

![]()

![map]()

Sanskrit Speech, of early times evolved into the various local modern Sanskrit-derived languages. " "Correct speech" was a crucial component of being about to take part in the appropriate yajnas (religious rituals and sacrifices). Thus, without correct speech, one could not hope to practice correct religion, either." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mleccha

Mleccha (from Vedic Sanskrit म्लेच्छ mleccha, ම්ලේච්ච meaning "non-Vedic"), are also spelled Mlechchha or Maleccha to indicate the uncouth, misspelt, ungrammatical and incomprehensible or indistinct speech.

Jāti is an extended kinship group which evolved out of the interactions related to the core doctrines. No wonder, Mahāvīra explains jaina ariya dhamma in mleccha (ardhamāgadhi), which differentiates into the present-day language kaleidoscope of Bhārat. It is not a mere accident that the discourses of the Buddha were in Pāli, a lingua franca of the times. Automatic transformation of ardhamāgadhi speech into the languages of the listeners is a way of affirming the nature of the lingua franca, Prākr̥tam, when Mahavira communicates Jaina dhamma as ariya dhamma. There is explicit permission to use Prākr̥tam, as a non-ariya language, that is non-use of grammatically correct Samskr̥tam, to communicate to all people: This is categorically stated in Kundakunda's Samayasāra, verse 8: yatha ṇa vi sakkam aṇajjo an.ajjabhāsam viṇā du gāhedum taha vavahāreṇa viṇā paramatthuva

desaṇam asakkam

This is a crucial phrase, vyavahāra or vavahāra, the spoken tongue in vogue, or the lingua franca, or what french linguists call, parole. The use of vyavahā bhāsa, that is mleccha tongue, was crucial for effectively communicating Mahavira's message on ariya dhamma. The study of Sanskrit and Prakrit as parallel cultural streams, together with yajna and vrata as parallel streams of dharma should be explored further through studies in an institution such as Itihaasa Bharati to unravel the contributions of janajāti to hindu thought, culture and heritage and to constitute a Hindumahāsāgar parivār (Indian Ocean Community).

To Karl Popper is attributed a logical postulate that a hypothesis in the empirical sciences can never be proven or verified, but a hypothesis can be falsified, meaning that it can and should be scrutinized by decisive experiments.

This 'falsifiability' postulate is restated as follows: a hypoethesis can never be independently verified but can be falsified by empirical evidence of experiments.

This is particularly true of hypotheses related to the underlying language and the purport/meaning of Indus Script inscriptions which are read as Meluhha language/speech hypertexts (composed of pictorial motifs and hieroglyphs).

How to validate the decipherment of Indus Script hypertexts in the absence of Rosetta stone or the Canopus Decree (two inscriptions which contained the same message in three scripts including Egyptian hieroglyph)?

One approach is the suggested approach of 'falsifiability' proposed by Karl Popper to falsify a hypothesis that Indus Script is in a Non-Mleccha language. Cypro-Minoan is a non-Meluhha language and this monograph falsifies the hypothesis that the Indus Script hypertexts on four pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa are written in a non-Mleccha language. So,the language is NOT Cypro-Minoan. The language is Meluhha, acording to my hypothesis proven with evidence of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions in 3 volumes.All the 8000+ hypertexts are read as metalwork wealth accounting ledgers rendered in Meluhha speech [Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union)]

I present evidence in this monograph that the hypothesis related to any Non-mleccha as the underlying rebus language of Indus Script hypertexts can be 'falsified' by empirical evidence.

The hypothesis that the hypertexts on four tin ingots found in a Haifa shipwreck signified Cypro-Minoan writing has been falsified. After the publication in 1977, of the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck at Haifa, Artzy published in 1983 (p.52), two more ingots found in a car workshop in Haifa which wasusing the ingots for soldering broken radiators. Artzy's finds were identical in size and shape with the previous two; both were also engraved with two marks. In one of the ingots, at the time of casting, a moulded head was shown in addition to the two marks. Artzy compares this head to Arethusa. (Artzy, M., 1983, Arethusa of the Tin Ingot, Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research, 250, p. 51-55). Artzy went on to suggest the ingots may have been produced in Iberia and disagreed with the suggestion that the ingot marks were Cypro-Minoan script. The author Michal Artzy (opcit., p. 55) showed these four signs on the four tin ingots to E. Masson who is the author of Cypro-Minoan Syllabary. Masson’s views are recorded in Foot Note 3: “E. Masson, who was shown all four ingots for the first time by the author, has suggested privately that the sign ‘d’ looks Cypro-Minoan, but not the other three signs.” Thus, three of the four signs were NOT Cypro-Minoan according to the known Cypro-Minoan syllabary.

I submit in this monograph empirical evidence from three pure tin ingots discovered in a shipwreck in Haifa contain Indus Script hypertexts hose meaning relate the four ingots to the message: ranku dhatu mũh. This message translates inMeluhha Bhāratīya sprachbund as: tin mineral ingot.

The thesis of this monograph is that mleccha म्लेच्छ is a form of Proto-Indian आर्य-वाच् (Arya speech) traceable from the metalwork, artisanal, seafarer lexis of Aratta in Gujarat as a representative region of Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union of ancient India) of ca. 4th millennium BCE. This civilizational indicator of language expressions related principally to metalwork, coincides with the participation of Bhāratam Janam (RV 3.53.12) in the Tin-Bronze revolution. Bhāratam Janam linked Eurasia with Ancient Far East (the largest tin-belt of the globe in the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween), as evidenced by the sources of Mon-Khmer languages in Austro-Asiatic framework of speechforms in Munda languages of Bhāratam Janam. The perennial, glacial-sourced Himalayan rivers ground down granite rocks on the river basins and created the cassiterite (tin ore) placer deposits which were mined by tin-panners and mercantile transactions engaged in along the Indian Ocean and Himalayan river waterways by seafaring Meluhha merchants. The thesis is premised on a hypothesis (work in process) that this Ancient Maritime Tin Route pre-dated the Silk Road by about two millennia. This is a work in process because archaeometallurgical investigations are needed to trace the sources of tin used in Eurasia during the millennia of Tin-Bronze revolution from ca. 5th to 2nd millennia BCE. The navigable waterways provided by Himalayan rivers were subject migrations in palaeo-channels, caused by plate tectonic events. The ongoing plate tectonic event is the metaphor of tāṇḍava nr̥tyam,'cosmic dance' which indicates the Indian plate moving northwards at a majestic rate of 6 cm. per year jutting into and lifting up the Eurasian plate by 1cm per year resulting in the Himalayan dynamics.

The earliest literary citations to mleccha as speech/language occur in Manusmṛti, and Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (both texts datable to periods earlier than 3rd cent BCE). The lexis of Aratta can be reconstructed from the lexis of over 25+ ancient languages of Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union) presented in the Indian Lexicon organized in over 1240 semantic clusters. (Note. Please download file of size 29.7 mb).

Such word and expressions recorded in this Indian Lexicon explain rebus the Indus Script hypertexts and meanings inMeluhha speech forms.

மிழலை¹ miḻalai , n. < மிழற்று-. cf. mlīṣṭa. Prattle, lisp; மழலைச்சொல். (சூடா.)மிழற்றல் miḻaṟṟal

, n. < மிழற்று-. 1. Speaking; சொல்லுகை. (சூடா.) 2. See மிழலை¹. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Noise of speaking; பேசலானெழு மொலி. (யாழ். அக.)மிழற்று-தல் miḻaṟṟu- , 5 v. tr. 1. To prattle, as a child; மழலைச்சொற் பேசுதல். பண் கள் வாய் மிழற்றும் (கம்பரா. நாட்டு. 10). 2. To speak softly; மெல்லக் கூறுதல். யான்பலவும் பேசிற் றானொன்று மிழற்றும் (சீவக. 1626). Southworth suggests that the name mleccha comes from miḻi- "speak, one's speech", derived from one of the Dravidian languages and related to the etymology of the word Tamiḻ. (Southworth, Franklin C. (1998), "On the Origin of the word tamiz", International Journal of Dravidial Linguistics, 27 (1): 129–132). Given the cognates mleccha and milakkhu (meluhha), it is suggested that the word mleccha is a reference to the speech forms of Bhāratīya sprachbund. That these speakers had exttensive contacts between Hanoi (Vietnam) and Haifa (Israel) is indicated by the evidence of 1. three pure tin ingots with Indus Script inscriptions discovered in a Haifa shipwreck and 2. use of Indus Script hypertexts on Dong Son/Karen Bronze Drums of Ancient Far East (Hanoi).

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum’s surface, Vietnam. Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id.(DEDR 5023) Rebus: mũh, muhã ‘ingot‘ or muhã ‘quantity of metal taken out of furnace’; मूका f. a crucible L. (= or w.r. for मूषा).

Image on the Ngoc Lu bronze drum’s surface, Vietnam. Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id.(DEDR 5023) Rebus: mũh, muhã ‘ingot‘ or muhã ‘quantity of metal taken out of furnace’; मूका f. a crucible L. (= or w.r. for मूषा).káṅkata m. ʻ comb ʼ AV. (CDIAL 2598).

S. kaṅgu m. crane, heron (→ Bal. kang); kaṅká m. heron VS. Rebus: kang ‘brazier, fireplace’ (Kashmiri) kaṅká m. ʻ heron ʼ VS. [← Drav. T. Burrow TPS 1945, 87; onomat. Mayrhofer EWA i 137. Drav. influence certain in o of M. and Si.: Tam. Kan. Mal. kokku ʻ crane ʼ, Tu. korṅgu, Tel. koṅga, Kuvi koṅgi, Kui kohko]Pa. kaṅka — m. ʻ heron ʼ, Pk. kaṁka— m., S. kaṅgu m. ʻ crane, heron ʼ (→ Bal. kang); B. kã̄k ʻ heron ʼ, Or. kāṅka; G. kã̄kṛũ n. ʻ a partic. ravenous bird ʼ; — with o from Drav.: M. kõkā m. ʻ heron ʼ; Si. kokā, pl. kokku ʻ various kinds of crane or heron ʼ, kekī ʻ female crane ʼ, kēki ʻ a species of crane, the paddy bird ʼ (ē?).(CDIAL 2595)

ranku ‘antelope’ rebus: ranku ‘tin’.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE.

Đông Sơn bronze drum mid-1st millennium BCE fabricated by the Đông Sơn culture in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam were produced from about 600 BCE or earlier until the third century CE. maraka 'peacock' Rebus: marakaka loha 'copper alloy, calcining metal'.

maraka 'peacock' Rebus: marakaka loha 'copper alloy, calcining metal'.Kur. mūxā frog. Malt. múqe id. / Cf. Skt. mūkaka- id. (DEDR 5023) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot'

kanku 'crane, egret, heron' rebus: kangar 'portable furnace'

arka 'sun' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper', arka 'gold'.

Indus Script hypertexts: 'face'

Indus Script hypertexts: 'face' mũh

Rebus: mũh, muhã ‘ingot‘ or muhã ‘quantity of metal taken out of furnace’; मूका f. a crucible L. (= or w.r. for मूषा).

dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu 'mineral ore' (that is, cast metal from ore).

ranku 'liquid measure' ranku 'antelope' (Santali) Rebus: Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali) raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf. nāga -- 2 , vaṅga -- 1 ] Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10567)

The inscriptions on two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa have been discussed in: Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Vol. 1, Number 11 (2010) — The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” By S. Kalyanaraman (Editor of JIJS: Prof. Nathan Katz)http://www.indojudaic.com/index.php?option=com_contact&view=contact&id=1&Itemid=8 (See embedded document).

milakkhu-rajana 'copper? dye' (Pali) Rebus: மிலேச்சமுகம் milēcca-mukam , n. < mlēccha-mukha. Copper; செம்பு. (யாழ். அக.) மிலைச்சம் milaiccam , n. < mlēccha. Vermilion; சாதிலிங்கம். (சங். அக.) म्लेच्छ 'copper, vermilion' (Monier-Williams) म्लेच्छ-मुख n. = म्लेच्छा*स्य L. = n. " foreigner-face " , copper (so named because the complexion of the Greek and Muhammedan invaders of India was supposed to be copper-coloured) L. (Monier-Williams) म्लेच्छ a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons L.; Rebus: Milakkhu [the Prk. form (A -- Māgadhī, cp. Pischel, Prk. Gr. 105, 233) for P. milakkha] a non -- Aryan D

आर्य--वाच् mfn. speaking the Aryan language मनु-स्मृति x , 45.; आर्य a master , an owner L.; a man highly esteemed , a respectable , honourable man पञ्चतन्त्र. शकुन्तला &c.

Source: The Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Manu, Calcutta: Sewell & Debrett, 1796.

Translation by .G.Buhler: X.43. But in consequence of the omission of the sacred rites, and of their not consulting Brahmanas, the following tribes of Kshatriyas have gradually sunk in this world to the condition of Sudras;

X.44. (Viz.) the Paundrakas, the Kodas, the Dravidas, the Kambogas, the Yavanas, the Sakas, the Paradas, the Pahlavas, the Kinas, the Kiratas, and the Daradas.

X.45. All those tribes in this world, which are excluded from (the community of) those born from the mouth, the arms, the thighs, and the feet (of Brahman), are called Dasyus, whether they speak the language of the Mlekkhas (barbarians) or that of the Aryans.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/manu/manu10.htm

Manusmṛti, 'reflections of Manu' is ancient legal text dated to ca. 2nd century BCE, among the many Dharmaśāstras of Hindu dharma. It is also referred to as Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. The Dharmasya Yonih (Sources of the Law) has twenty-four verses.

The closing verses of Manusmriti declares,

— Manusmriti 12.125, Calcutta manuscript with Kulluka Bhatta commentary. Manu notes (10.45):

mukhabāhūrupajjānām yā loke jātayo bahih

mlecchavācaś cāryavācas te sarve dasyuvah smr̥tāh

This shows a two-fold division of dialects: arya speech and mleccha speech. The language spoken was an indicator of social identity. In ancient Bhāratiya texts, mleccha, a Prākr̥tam, was recognised as an early speech form, a dialect referred to in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and Mahābhārata, a dialect which required a translator for a Mesopotamian transacting with a sea-faring Meluhha merchant of Saptasindhu region.

Mahābhārata refers to many groups of people such as: Sakas, Huns, Yavanas(Greek), Kambojas, Pahlavas, Bahlikas, Rishikas, Chinas(China). The text describes mleccha with "heads completely shaved or half-shaved or covered with matted locks, [as being] impure in habits, and of crooked faces and noses", as "dwellers of hills" and "denizens of mountain-caves. Mlecchas were born of the cow, Nandini, (belonging to Vasiṣṭha), of fierce eyes, accomplished in smiting looking like messengers of death, and all conversant with the deceptive powers of the Asuras". The text gives the following information regarding mleccha:

- Mleccha who sprang up from the tail of the celestial cow Nandini sent the army of Viswamitra flying in terror.

- Bhagadatta was the king of mlecchas.

- Pāṇḍavas, like Bhima, Nakula and Sahadeva once defeated them.

- Karna during his world campaign conquered many mleccha countries.

- The wealth that remained in the Yāgaśāla of Yudhiṣṭhira after the distribution as gifts to Brāhmaṇa-s was taken away by the mlecchas.

- The mlecchas drove angered elephants on the army of the Pāṇḍavas.

Amarakośa describes the Kiratas , Khasas and Pulindas as the Mleccha-jatis. In some ancient texts, Indo-Greeks, Scythians,and Kushanas were also mlecchas The Vāyu, Matsya and Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇas state that the seven Himalayan rivers pass through mleccha countries. Baudhāyana Sutra-s refer to a mleccha as someone "who eats meat or indulges in self-contradictory statements or is devoid of righteousness and purity of conduct." (reference citation not provided).

Ānava with variant pronunciations of words/expressions were located on frontiers of Āryāvarta in regions such as Gāndhāra, Kāśmīra and Kāmbojas.

Such Ānava could be in the lineage of Āmāvasu mentioned in: Baudhāyana Śrautasūtra (BSS) 18.45 and the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 11.5.1 which indicate the wanderings of lineage of Pururavas took place from Kurukshetra. Pururavas and Urvaśi had two sons, Āyu and Āmāvasu. According to the Vādhūla Anvākhyāna 1.1.1, yajña rituals were not performed properly before the attainment of the gandharva fire and the birth of Āyu who ensures the continuation of the human lineage that continues down to the Kuru kings, and beyond.

Clearly, Caland interpreted the passage to mean that from a central region, the Arattas, Gandharis and Parsus migrated west, while the Kasi-Videhas and Kuru-Pancalas migrated east. Combined with the testimony of the Satapatha Brahmana (see below), the implication of this version in the Baudhāyana śrautasūtra, narrated in the context of the Agnyadheya rite is that that the two outward migrations took place from the central region watered by the Sarasvati. (Kashikar, Chintamani Ganesh. 2003. Baudhāyana śrautasūtra (Ed., with an English translation). 3 vols. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass/IGNCA).

Ṛgveda hymn 6.61.9,12 says that 5 Aryan groups of people spread beyond the seven sister-rivers (sapta sindhavah)!

In volume III of his translation, on p. 1235, Kashikar translates the relevant sentences of the text BSS 18.44 as follows-

"Ayu moved towards the east. Kuru-Pancala and Kasi-Videha were his regions. This is the realm of Ayu. Amavasu proceeded towards the west. The Gandharis, Sparsus and Arattas were his regions. This is the realm of Amavasu."

Baudhāyana’s Śrautasūtra 18.4 mentions two migrations of the Vedic people. One was eastward, the Āyava. The other was westward, the Āmāvasa, and this produced the Gāndhāris (Gandhāra and Bactria), the Parśus Persians and the Arattas (of Urartu and/or Ararat on the Caucasus?). Map showing the “seven rivers and Sarasvatī”; various sites with Harappan artefacts far from Saptasindhu; also the two movements eastward by Āyu and westward by Āmāvasu. Read more at: https://www.newsgram.com/vedic-sanskrit-older-than-avesta-baudhayana-mentions-westward-migrations-from-india-dr-n-kazanas

In an obscure study15 of the Urvashi legend in Dutch, he focuses on the version found in Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44-45 and translates the relevant sentences of text as (Caland, Willem. 1903. "Eene Nieuwe Versie van de Urvasi-Mythe". In Album-Kern, Opstellen Geschreven Ter Eere van Dr. H. Kern. E. J. Brill: Leiden, pp. 57-60).

"Naar het Oosten ging Ayus; van hem komen de Kuru's, Pancala's, Kasi's en Videha's. Dit zijn de volken, die ten gevolge van het voortgaan van Ayus ontstonden. Naar het Westen ging Amavasu; van hem komen de Gandhari's. de Sparsu's en de Aratta. Dit zijn de volken, die ten gevolge van Amavasu's voortgaan ontstonden."

Translated into English (by Koenraad Elst.), this reads –

"To the East went Ayus; from him descend the Kurus, Pancalas, Kasis and Videhas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Ayus's going forth. To the West went Amavasu; from him descend the Gandharis, the Sparsus and the Arattas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Amavasu's going forth."

In his recent study [Tushifumi Goto. 'Pururavas und Urvasi" aus dem neuntdecktem Vadhula-Anvakhyana (Ed. Y. Ikari)'. pp. 79-110 in Tichy, Eva and Hintze, Almut (eds.). Anusantatyai; J. H. Roll: Germany (2000)] of the parallel passages dealing with the Agnyadheya rite, Goto translates the Sutra passage in the following words (p. 101 sqq.) –

""Nach Osten wanderte Ayu [von dort] fort. Ihm gehdie genannt werden: "kurus und pancalas, kazis und videhas."{87} Sie sind die von Ayu stammende Fortfuehrung. {88} Nach Westen gewandt [wanderte] amavasu [fort]. Ihm gehoeren diese: "gandharis, parzus, {88} arattas". Sie sind die von amAvasu stammende [Fortfuehrung]. {90} {87}iti kann hier kaum die die Aufzaehlung abschliessende Partikel (Faelle bei OERTEL Synt. of cases, 1926, 11) sein. In den beiden Komposita koennte der Type ajava'h' [die Gattung von] Ziegen und Schafen' vorliegen: pluralisches Dvandva fuer die Klassifikation, vgl. GOTO Compositiones Indigermanicae, Gs. Schindler (1999) 134 n. 26. {88} Gemeint ist hier wohl die Erbschaft seiner Kolonisation ("Fortwanderung"); mit

bekannter Attraktion des Subj.-Pronomens in Genus und Numerus an das Pr

{89} Mit WITZEL, Fs. Eggermont (1987) 202 n. 99, Persica 9 (1980) 120 n.126 als gandharayas parsavo statt -ya sparsavo aufgefasst, wofuer dann allerdings im rezenten BaudhSrSu die Schreibung gandharayah parsavo zu erwarten wals -SP- ausgesprochen wurde (wie z.B. in der MS, vgl. AiG I 342) und noch kein H (fÔr das erste s) eingefuehrt wurde. -yaspa- entging einer (interpretatorischen) {90} Dahinter steckt wohl die Vorstellung von Ayu' als normales Adjektiv 'lebendig, beweglich' und entsprechend, wie KRICK 214 interpretiert, von amavasu-: "nach Westen [zog] A. (bzw.: er blieb im Westen in der Heimat, wie sein Name 'einer, der Gueter daheim hat' sagt."."

Loosely translated23 into English, this reads –

"From there, Ayu wandered Eastwards. To him belong (the groups called) 'Kurus and Panchalas, Kashis and Videhas' (note 87). They are the branches/leading away (note 88) originating from Ayu. From there, Amavasu turned westwards (wandered forth). To him belong (the groups called) 'Gandharis, Parsus (note 89) Arattas'. They are the branches/leading away originating from Amavasu. (note 90)." {90}: It appears that the notion of 'Ayu' as an normal adjectival sense 'living', 'agile' underlies this name. Correspondingly, Krick 214 interprets Amavasu as – "Westwards [travelled] A. (or: he stayed back in the west in his home, because his name says –'one who has his goods at home')".

A very strong piece of evidence for deciding the correct translation of Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44 is the passage that occurs right after it, i.e., Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.45...From this text, it is clear that Urvasi, Pururava and their two sons were present in Kurukshetra in their very lifetimes. There is no evidence that they traveled all the way from Afghanistan to Haryana (where Kurukshetra is located), nor is there any evidence that she took her sons from Kurukshetra to Afghanistan after disposing off the pitcher. The passage rather only to indicate that the family lived in the vicinity of Kurukshetra region. Therefore, the possibility that Amavasu, one of the two sons of Pururava and Urvasi lived in Afghanistan from where Ayu, the other son, migrated to India is totally negated by this passage. Rather, BSS 18.45 would imply that the descendants of Amavasu, i.e., Arattas, Parsus and Gandharis migrated westwards from the Kurushetra region. (It may be pointed out that in Taittiriya Aranyaka 5.1.1, the Kurukshetra region is said to be bounded by Turghna (=Srughna or the modern village of Sugh in the Sirhind district of Punjab) in the north, by Khandava in the south (corresponding roughly to Delhi and Mewat regions), Maru (= desert, noting that the Thar has advanced eastward into Haryana only in recent centuries) in the west, and 'Parin' (?) in the east. This roughly corresponds to the modern state of Haryana in India)...

Locus of Aratta

Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra (with Govindswami's commentary, and a gloss by Chinnaswami Shastri). Chaukhamba Sanskrit Series: Varanasi) First Sūtra 1.1.2.10 defines Aryavarta as the land west of Kalakavana (roughly modern Allahabad), east of 'adarsana' (the spot where Sarasvati disappears in the desert), south of Himalayas and north of the Vindhyas. An alternate definition of Aryavarta in sūtra 1.1.2.11 restricts Aryavarta to the Ganga-Yamuna doab. The text then enumerates the following peoples who are of 'mixed' origins, and therefore whose traditions are not worthy of emulation by the residents of Aryavarta –

"Avanti (-Ujjain), Anga (= area around modern Bhagalpur in Bihar), Magadha, Surashtra (= modern Kathiawar), Upavrta, Sindhu (= modern Sindh), Sauvira (= modern Bahawalpur, and Pakistani Panjab south of Multan) are (i.e., the residents of these regions are) of mixed origin." Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra 1.1.2.14 "Aratta, Karaskara (=Narmada valley?), Pundra (=northern Bengal), Sauvira, Vanga (= southern Bengal), Kalinga – whosoever visits these areas should perform Punastoma or Sarvaprshthi sacrifices as an expiation." Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra 1.1.12.15.

In such an enumeration as in Baudhāyana Dharmasūtra 1.1.2.14, Aratta may also be interpreted as a reference to Gujarat region where the lingua franca was mleccha bhāṣā or mleccha vācas. (cf. Hemacandra's magnum opus deśīnāmamālā).

Aratta is identified as a region on the periphery of Aryavarta (Ganga-Yamuna doab) but close to it. Such a region was peopled by Meluhha (mleccha) speakers who can be distinguished from Arya vācas, speech of residents of Aryavarta. With such a distinction, it is possible to postulate Meluhha (mleccha) as proto-Indo-Aryan or precursor versions ofPrākṛts or deśi. Such Mleccha vācas of 'impure regions' detailed in both the texts identified the Meluhha region and Meluhha artisans/traders had their sea-faring merchandise and donkey caravans along the Tin road of the bronze age extending from Meluhha into the Fertile Crescent. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/proto-indian-meluhha-precursor-of.html

This identification of thelocus of Aratta is consistent with Caland interpretation of the BSS passage to mean that from a central region, the Arattas, Gandharis and Parsus migrated west.

Sanskrit Speech, of early times evolved into the various local modern Sanskrit-derived languages. " "Correct speech" was a crucial component of being about to take part in the appropriate yajnas (religious rituals and sacrifices). Thus, without correct speech, one could not hope to practice correct religion, either." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mleccha

Mleccha (from Vedic Sanskrit म्लेच्छ mleccha, ම්ලේච්ච meaning "non-Vedic"), are also spelled Mlechchha or Maleccha to indicate the uncouth, misspelt, ungrammatical and incomprehensible or indistinct speech.

Jāti is an extended kinship group which evolved out of the interactions related to the core doctrines. No wonder, Mahāvīra explains jaina ariya dhamma in mleccha (ardhamāgadhi), which differentiates into the present-day language kaleidoscope of Bhārat. It is not a mere accident that the discourses of the Buddha were in Pāli, a lingua franca of the times. Automatic transformation of ardhamāgadhi speech into the languages of the listeners is a way of affirming the nature of the lingua franca, Prākr̥tam, when Mahavira communicates Jaina dhamma as ariya dhamma. There is explicit permission to use Prākr̥tam, as a non-ariya language, that is non-use of grammatically correct Samskr̥tam, to communicate to all people: This is categorically stated in Kundakunda's Samayasāra, verse 8: yatha ṇa vi sakkam aṇajjo an.ajjabhāsam viṇā du gāhedum taha vavahāreṇa viṇā paramatthuva

desaṇam asakkam

This is a crucial phrase, vyavahāra or vavahāra, the spoken tongue in vogue, or the lingua franca, or what french linguists call, parole. The use of vyavahā bhāsa, that is mleccha tongue, was crucial for effectively communicating Mahavira's message on ariya dhamma. The study of Sanskrit and Prakrit as parallel cultural streams, together with yajna and vrata as parallel streams of dharma should be explored further through studies in an institution such as Itihaasa Bharati to unravel the contributions of janajāti to hindu thought, culture and heritage and to constitute a Hindumahāsāgar parivār (Indian Ocean Community).

The evidence of four pure tingots with Indus Script hypertexts, with the message of inscription: tin mineral ingot validates that Bhāratīya Meluhha speakers (of Bhāratīya sprachbund) mediated as seafaring merchants and artisans with their counterparts in Mon-Khmer speaker areas of Ancient Far East to make available tin ingots to further advance the Tin Bronze Revolution which was founded ca. 4th millennium BCE.

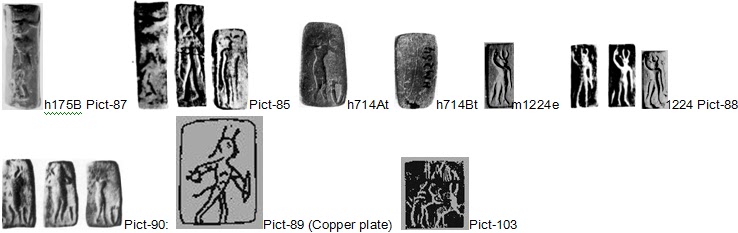

m1429

m1429

Pict-91

Pict-91

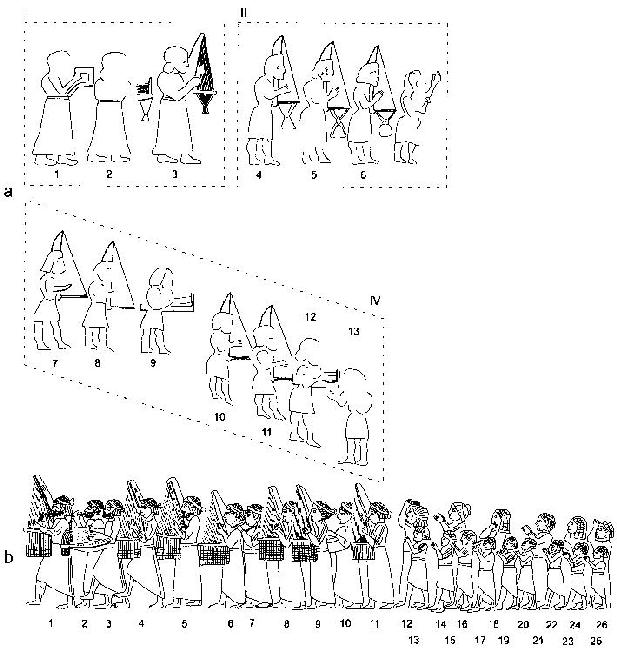

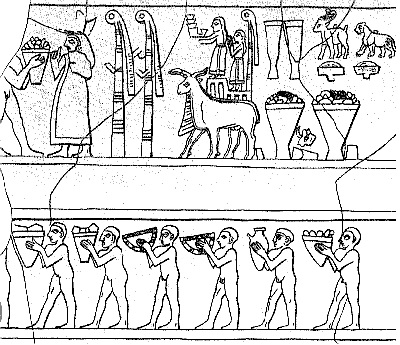

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall head-dress standing within an ornamented arch; there are two stars on either side, at the bottom of the arch.मेढ

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall head-dress standing within an ornamented arch; there are two stars on either side, at the bottom of the arch.मेढ  Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

/detail-of-the-standard-of-ur-showing-a-sumerian-harpist-and-a-ruler-about-2600-2400-bc-501585375-589b3c525f9b5874eedd992b.jpg)

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

[quote]

[quote]

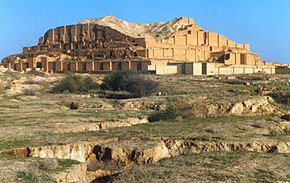

Chapitre 1

Chapitre 1

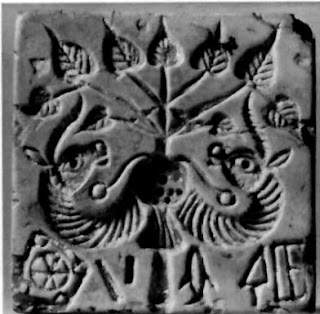

Carved stone tablets with the inscription Om syllables from Om Mani Padme Hum mantra - Everest region, Nepal, Himalayas

Carved stone tablets with the inscription Om syllables from Om Mani Padme Hum mantra - Everest region, Nepal, Himalayas

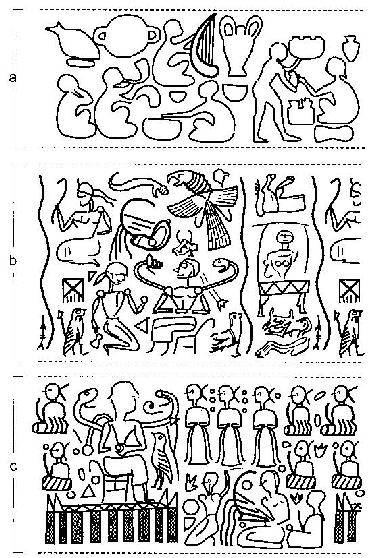

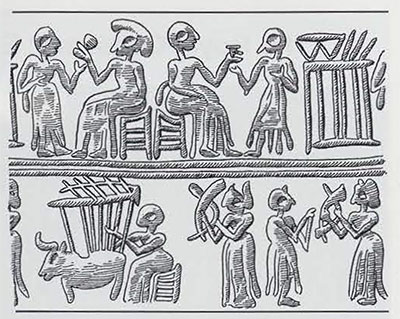

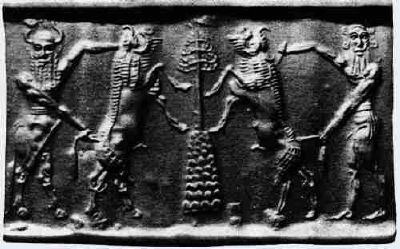

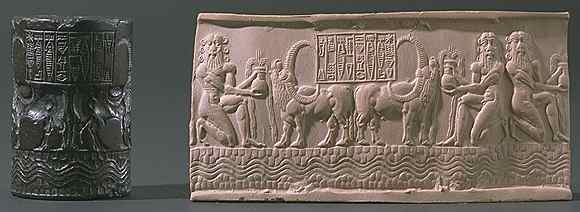

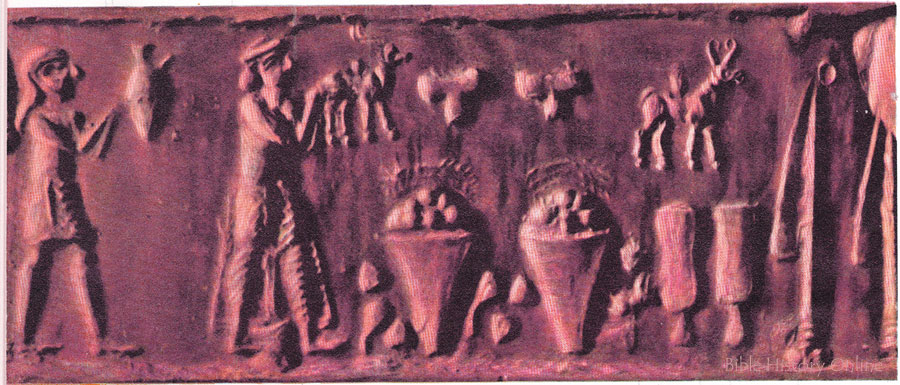

Cylinder seal impression.

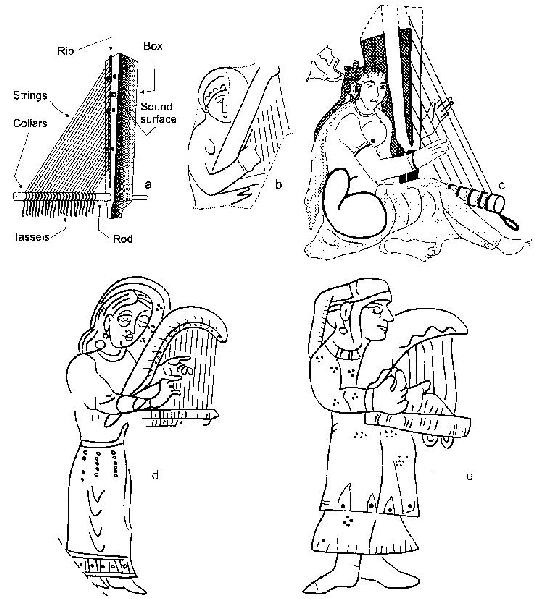

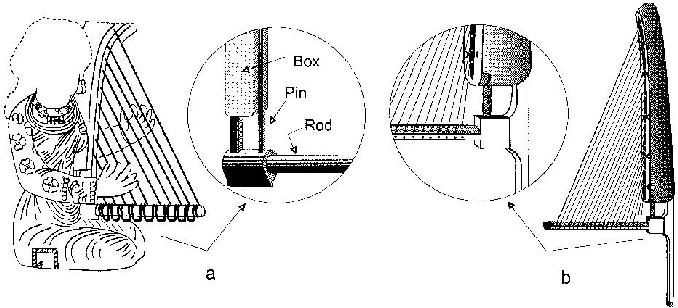

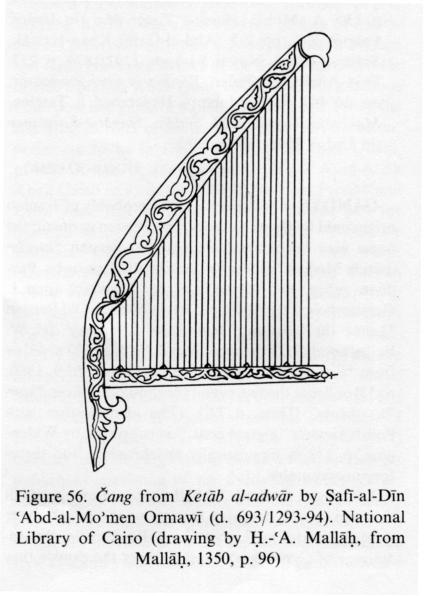

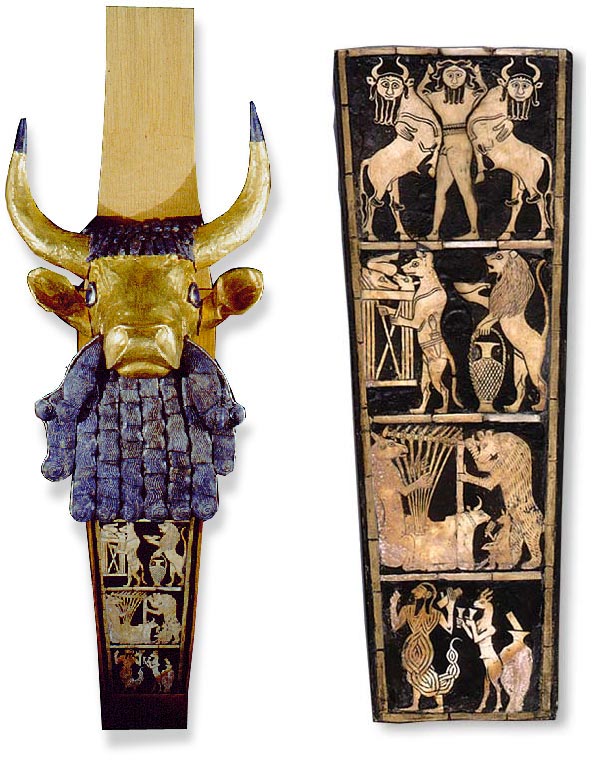

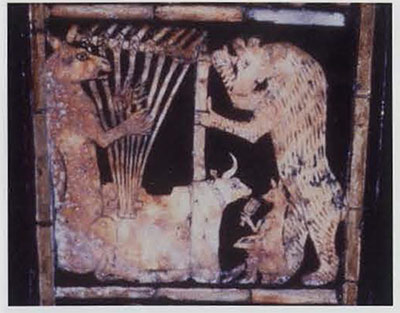

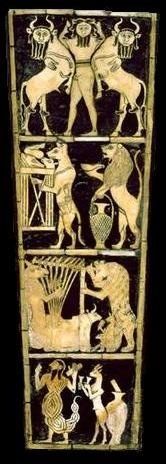

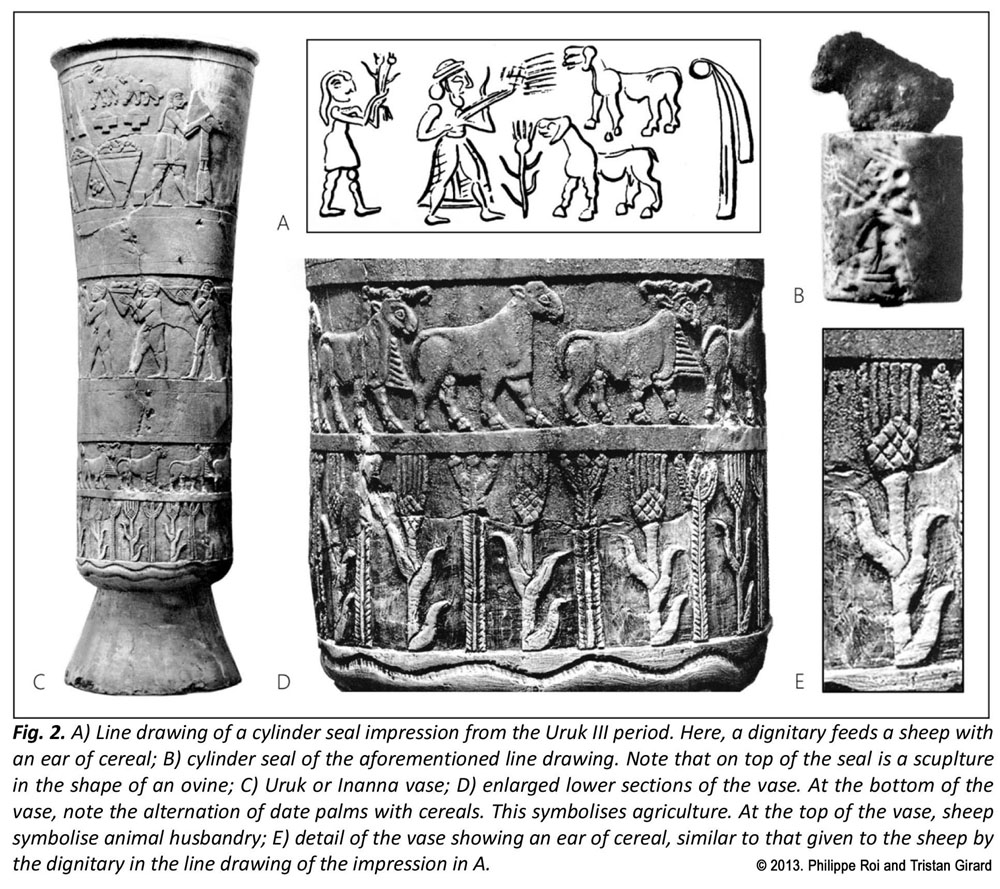

Cylinder seal impression. "Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm. 2550 - 2400 BCE, royal tomb at Ur (cf. pg. 106 of J. Aruz and R. Wallenfels (eds.) 2003 Art of the First Cities).

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm. 2550 - 2400 BCE, royal tomb at Ur (cf. pg. 106 of J. Aruz and R. Wallenfels (eds.) 2003 Art of the First Cities).

![clip_image033[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0334-thumb.jpg?w=71&h=44)

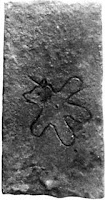

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

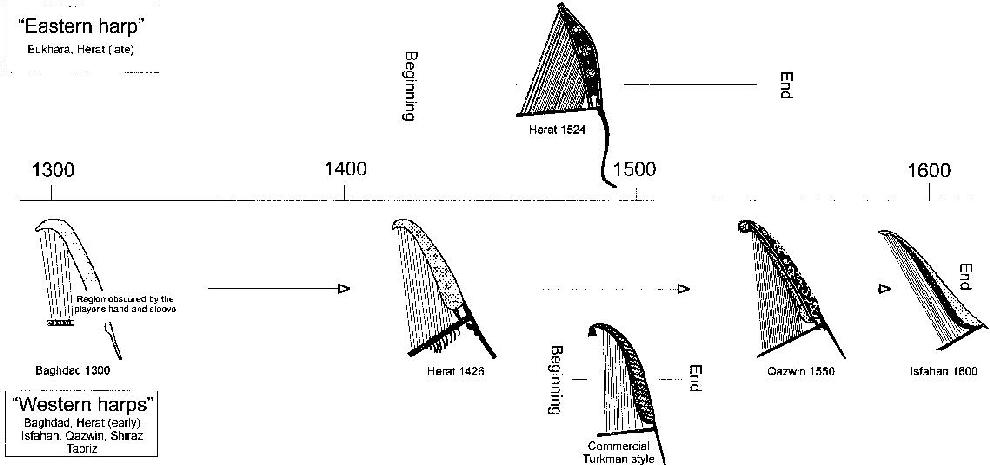

Line drawing of a proto-elamite cylinder seal impression.

Line drawing of a proto-elamite cylinder seal impression.

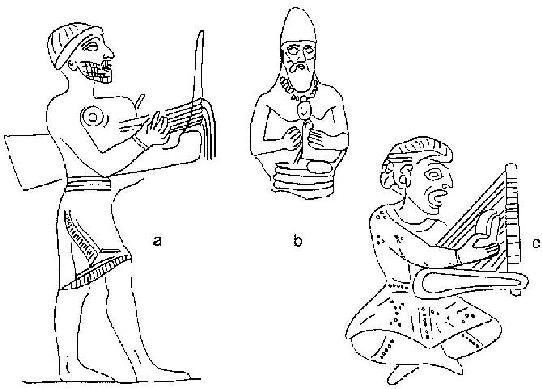

British Museum.

British Museum.  Unprovenienced. Person with a mace.

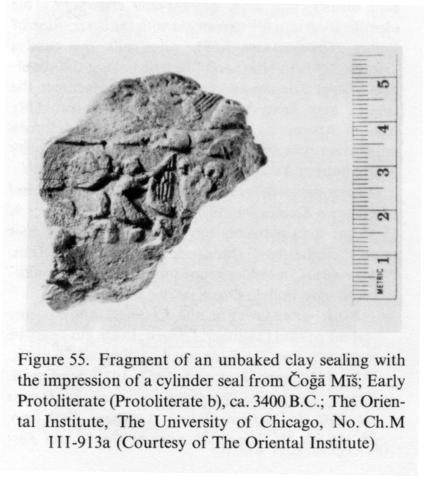

Unprovenienced. Person with a mace. Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Maceheads. Votive?

Maceheads. Votive?