Śiva Sūtras are attributed to the sage Vasugupta of the 9th century C.E.

Śiva Sūtras are 77 brilliant aphorisms (in sections) on consciousness, the central problem of science and mind. -- Subhash Kak.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja), Chola period (880-1279), ca. 11th century Tamil Nadu, India Copper alloy; H. 26 7/8 in. (68.3 cm); Diam. 22 1/4 in. (56.5 cm) Gift of R. H. Ellsworth Ltd., in honor of Susan Dillon, 1987 (1987.80.1)

If a single icon had to be chosen to represent the extraordinarily rich and complex cultural heritage of India, the Shiva Nataraja might well be the most remunerative candidate. It is such a brilliant iconographic invention that it comes as close to being a summation of the genius of the Indian people as any single icon can. Sculptures of Shiva dancing survive from at least as early as the fifth century, but it was under the rule of the great Chola dynasty of southern India (880-1279) that the world-famous iconographic type evolved. The setting of Shiva's dance is the golden hall of Chidambaram, at the center of the universe, in the presence of all the gods. Through symbols and dance gestures, Shiva taught the illustrious gathering that he is Creator, Preserver, and Destroyer. As he danced he held in his upper right hand the "damaru," the hand drum from which issued the primordial vibrating sound of creation. With his lower right hand he made the gesture of "abhaya," removing fear, protecting, and preserving. In his upper left hand he held "agni," the consuming fire of dynamic destruction. With his right foot he trampled a dwarf like figure (apasmara purusha), the ignoble personification of illusion who leads mankind astray. In his dance of ecstasy Shiva raised his left leg, and, in a gesture known as the "gaja hasta," pointed to his lifted leg to provide refuge for the troubled soul. He thus imparted the lesson that through belief in him, the soul of mankind can be transported from the bondage of illusion and ignorance to salvation and eternal serenity. Encircling Shiva is a flaming body halo ("prabhamandala," or surrounding effulgence) that not only establishes the visual limits of this complex and dynamic composition but also symbolizes the boundaries of the cosmos.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/86746598

Section 1. Śāmbhavopāya

Section 2. Śaktopāya

Section 3. Anavopāya

Translations by Subhash Kak and Shailendra Sharma

Section 1. Śāmbhavopāya

चैतन्यमात्मा॥१॥ Consciousness is the Self.

1.

Translation — Consciousness is soul.

Exposition — Consciousness of immense mind, which is manifested by means of body, is the cause of feeling of being. Consciousness of the mind is soul.

2. ज्ञानं बन्धः॥२॥

(Ordinary) knowledge is bounding. (By revealing some it hides more)Translation — Knowledge is bondage.

Exposition — The immense mind, which is manifested by means of the body, adopts physical limitations to know the totality of its own consciousness and also the one who manifests it. Said in other words, it limits itself in a bond with the body for the sake of knowing itself.

3. योनिवर्गः कलाशरीरम्॥३॥

The emanated embodied forms change.Translation — Body is small bit of power of the origin.

Exposition — Body is only a small bit of power of the creator of all.

4. ज्ञानाधिष्ठानं मातृका॥४॥

The basis of knowledge is in the potential. (the womb)Translation — Origin is the basis of knowledge.

Exposition — Body, that functions as a mother for the knowledge is a creator, who awakens the entire consciousness and delivers it in its entire immensity.

5. उद्यमो भैरवः॥५॥

(In) [inspired] activity is Bhairava [annihilating + creating aspect of Śiva, for beginnings must start with ending] Translation — Terrible truth is effort.

Exposition — Effort that a mind needs to perform by means of body for awakening the truth of its own dormant consciousness is terrible. It may be said to be extremely difficult.

6. शक्तिचक्रसन्धाने विश्वसंहारः॥६॥

The world ends with coming together of various energies.Translation — Creation can be annihilated when Sakticakra is sought.

Exposition — Just as infinite energy prevailing inside an atom appears in its vastness when an atom is sought and disintegrated, much the same way, when the consciousness of immense mind, which is capable of knowing everything is sought by means of body and is disintegrated by means of Pranayam, the consciousness is awakened and is then manifested in its entire immensity.

One who successfully performs this practice is at liberty of applying consciousness of his boundlessly awakened mind. He may at his discretion establish a New World or annihilate the existing one.

7. जाग्रत्स्वप्नसुषुप्तभेदे तुर्याभोगसम्भवः॥७॥

In waking, dreaming, or deep sleep, one can have a sense of the fourth (deeper) state.Translation — Experience (Direct perception) of the fourth state is possible by separating the awakened, dream and dormant states of mind.

Exposition — Consciousness of his mind that a common man is capable of applying is awake only in small measures. Thinkers call this as conscious mind or awakened mind. And infinite consciousness of mind that prevails with every embodied being in dormant state and that which causes dream like feeling about it even after its knowledge is called as sub consciousness.

When immensity of mind that appears dream like is awakened by applying consciousness that is awake in small measures, one experiences that fourth state of mind i.e. completely awakened immense consciousness of mind, which is beyond these three (viz. partly awake consciousness, dormant immense consciousness and firm determination to awaken dormant vast consciousness).

8.ज्ञानं जाग्रत्॥८॥

Knowledge is the waking state. Translation — Only awakening is knowledge.

Exposition — A small bit of entire dormant infinite consciousness of mind that is awake, and which thinks the entire dormant consciousness to be dream like is the cause of restraining consciousness within physical limitations.

9.

Translation — Indecision about dream is ignorance.

Exposition — A feeling that immense consciousness of mind that lies dormant within one self is only a dream and a state of being uncertain about its existence is called as ignorance.

10. .

Translation — To feel, what is there is not there, due to indiscretion is spiritual ignorance.

Exposition — The mind rejecting the existence of its own infinite consciousness by considering it as dream like, although it is dormant within itself, is called as indiscretion.

11.

Translation — One, who can enjoy the three, is great among the heroes.

Exposition — One who awakens the dormant infinite consciousness of the mind, although feeling of its existence is dream like, by means of partly awakened consciousness, or, said differently a great person who makes firm determination for realizing dream, makes awesome efforts, and realizes the dream is the bravest among the braves.

12. .

Translation — Astonishment is the basis for yoga.

Exposition — Even a guess of infinite capacity of mind that lies dormant in an apparently ordinary personality of oneself, strikes wonder and is inspirational for those who are determined to awaken it into practicing yoga.

13.

Translation — Will power is the ultimately beautiful virgin.

Exposition — A strong will power to awaken infinite consciousness of mind that lies dormant within oneself is that most beautiful virgin who is solicited and thereby one begets awakened consciousness as if he begets a son.

14. .

Translation — Visible is the body.

Exposition — The entire visible world that lies within the realm of experiences of this body is the body of Him who manifests this all.

15.

Translation — By concentrating the mind into the core it knows its invisible form and is then established beyond the visible.

Exposition — The sublime consciousness element that is manifested by means of entire visible world is also the cause of manifestation of mind. When mind concentrates into itself with a strong will power, through its own consciousness by means of a body, it experiences its immense invisible existence that lies beyond the physical limits. Subsequently it gets the experience of the existence of the element of conscious void, which lies beyond entire visible world, and is experienced through the medium of vision.

16.

Translation — An investigation of sublime element causes knowledge of one’s abilities.

Exposition — When the existence of sublime conscious void that lies beyond the visible is experienced, the feeling of being begins to grow boundlessly and one knows ones infinite existence.

17.

Translation — Deliberation causes self-realization.

Exposition — When sublime conscious void that remains beyond the body is experienced one is established in pure thought that lies beyond the visible and then self-realization takes place. Pure thought alone is the cause of there being a relation between conscious world and the corporal matter of the visible world.

18.

Translation — Enjoying Samadhi is like enjoying the world.

Exposition — When established in pure thought and having achieved self-realization, one knows the conscious void that supports the entire world. Subsequent to the knowledge of conscious void that manifests and retains the visible world on the support of visible body, there remains no difference between so-called worldly pleasures and the delight of samadhi. This is because the basic cause that is manifested and is experienced in both is one and the same – the awakened consciousness.

19.

Translation — Concentration into the void causes knowledge of creation of body.

Exposition — Supporter of the entire visible world, the conscious void, supports entire corporal matter of the world and fosters it. When mind that is replete with yogic power concentrates upon the consciousness void that contains all activities/motion, it gains the knowledge of creation of the entire visible world.

20.

Translation — By concentrating upon the one that is created, each member of the creation separately as well as their combinations become known.

Exposition — When a self-realized mind is concentrated upon corporal matter of visible world, knowledge of five elements of matter (viz. Earth, Water, Fire, Air & Sky) as separate entities as well as in combinations of various proportions take place.

21.

Translation — When creation and then existence in pure form is known, one masters this cycle.

Exposition — When knowledge of truth is gained that there exists conscious matter, which is manifested on the support of pure thought that is elicited from the conscious void, the cycle of its manifestation, existence for a while and again its assimilation in the conscious void is mastered.

22.

Translation — Exploring the great sound causes experience of the power of creator of this secret sound.

Exposition — When a self-realized mind concentrates on the great sound that pervades the conscious void it knows from whither that great sound originates. It experiences the infinite power of time, the ultimate element, the origin of all, the one that manifests and retains even the consciousness void that in turn manifests, retains and contains all activities of matter, the one who manifest that great sound, the destroyer, the time. All this is manifested only from the womb of time, only time retains it and it is only time that destroys it. When this all is destroyed this is assimilated in time itself only to be manifested later at some other time.

Section 2. Śaktopāya

23.

Translation — Most mysterious is the mind.

Exposition — It is only mind that unveils the knowledge of hidden mysteries.

24.

Translation — Effort is achiever (Sadhak).

Exposition — Effort of the mind for knowing hidden secrets is itself called as achiever. Mind together with the seed of infinite consciousness solicits a body to know itself, as such the mind is the achiever that makes efforts to cause the birth of its own consciousness.

25.

Translation — Existence of the present body itself is a hidden secret.

Exposition — The one who causes the body to exist, the one who makes efforts by taking support of body for the birth of its own consciousness, the one who avails of a body and yet remains hidden, the one who conducts everything by means of body, and the one who has the capacity to know infinite hidden mysteries, is one and the only one – The Mind.

26.

Translation — Dream is realized when growth of consciousness in the womb is distinctive.

Exposition — When mind plants a seed of consciousness in the womb- like body, it grows up and is established in its own infinite magnitude, which in the beginning appears dream- like. Said in other words infinite magnitude of consciousness that looks dream- like, grows up in the body and becomes a reality when it is born.

27.

Translation — When existence in an unsupported state that lies beyond death becomes natural, status become Shiva- like.

Exposition — The one, who conceives the conscious seed of mind in the womb, develops and then delivers through the medium of the body, the one, who is born through the medium of death after total development of consciousness beyond all physical limits, no longer needs any support for the birth of consciousness. It then establishes him in his own self without any dependence and attains union with time.

28.

Translation — This is the Great Way.

Exposition — The mind availing of a body and causing it to conceive with the seeds of consciousness, developing the foetus, delivering the totally awakened consciousness through the medium of physical death and subsequently developing consciousness up to a state of no support and uniting such consciousness with the time, this is that Great Way.

29.

Translation — The Cycle of Origin ends.

Exposition — Since mind causes the body to conceive and deliver immense consciousness, the body is the origin of consciousness. Since body delivers the consciousness after developing it, therefore body is the mother of consciousness. When birth of consciousness takes place in its completeness and the consciousness unites with time, the mind no more needs a body, since this no more remains necessary. Therefore, mind taking on a body till the birth of infinite consciousness, leaving a body even before consciousness is fully developed and when body becomes emaciated and ones again assuming a new body, this cycle disappears.

30.

Translation — Body is an offering.

Exposition — Mind availing of a body, developing consciousness using the body as womb and then delivering consciousness through the medium of physical death – in this cycle the body is offered as a sacrifice.

31.

Translation — Knowledge is food.

Exposition — The knowledge that accrues subsequent to mind taking on a body, developing consciousness using the body as a womb and then delivering it through the medium of physical death, this knowledge itself is the food of the mind.

32.

Translation — When existence is annihilated, it comes forth and experiences the dream.

Exposition — When completely developed in the womb of body, consciousness, the daughter of mind as father and body as mother, is born through the medium of death and then a consciousness that is now established without any support unites with the time. When it unites with the time, it is as if its existence becomes no more and knowledge of time that appeared like a dream before birth of developed consciousness unfolds itself after union with the time. In other words we may say that, consciousness, the daughter of mind and body marries with the time itself and after marriage, while living in the heart of her husband, she unites with him.

Section 3. Anavopāya

33.

Translation — Mind is soul.

Exposition — A mind, which takes on a body, plants a seed of consciousness using the body as a womb, develops the foetus completely and causes the birth of infinitely developed consciousness through the medium of physical death, is the one that alone is the feeling of being.

34.

Translation — Knowledge is bondage.

Exposition — The mind that has infinite capacity has to limit itself in physical limits by taking on a body to develop and deliver the consciousness.

35.

Translation — Indiscretion about real truth by the degrees is illusion.

Exposition — Prior to development of consciousness in a body that is but a small grain in the entire manifest world being unable to be judicious about time – the supreme lord, the one who manifests all, and the one who plays with the unexpressed element, the consciousness is illusion. Said differently, to believe what very much is there as not being there is illusion.

36.

Translation — Merger of degrees within body.

Exposition — When complete development of consciousness is attained by means of intense practice of yoga through the medium of body, eventually the fractured consciousness, which in the beginning is experienced piecemeal combines together and unfolds itself in its own complete vastness.

37.

Translation — Gaining Control upon elements, knowing each element separately.

Exposition — When consciousness that is above physical limits is born, knowledge of five elements of the corporal body of the world (viz. Earth, Water, Fire, Air & Sky) is begotten and then these are mastered. Eventually consciousness attains union with time, the time that manifests these elements, that which is the element of all elements, the fancy of the elements and the consciousness becomes time itself. Thereafter the body that delivers infinite consciousness also vanishes because all the five elements (viz. Earth, Water, Fire, Air & Sky) that are the basis of the body are absorbed in their origin.

38.

Translation — Attaining perfection by the envelope of ignorance.

Exposition — Mind takes on a body for causing birth of consciousness. By taking on a body, it presumably falls in an envelope of ignorance. But this body – an envelope of ignorance – itself completes the task of developing consciousness up to its totality in the womb of the body and causes its birth through the medium of physical death.

39.

Translation — Ending ignorance naturally leads to a state of infinite passiveness that endures.

Exposition — After completely developing and delivering consciousness through the medium of body, i.e. envelope of ignorance, the consciousness becomes established in infinity and is united with time. Eventually after uniting with time, having enjoyed everything, a state of passiveness or a state beyond enjoyment remains in natural existence until eternity.

40.

Translation — One who awakens becomes like a son.

Exposition — A great yogi who awakens his entire dormant consciousness through the medium of body and realizes his being in existence without corporal body becomes time conscious. And by knowing time that in the beginning appears dream like he as if becomes an offspring of time and he himself becomes omnipotent and omniscient like time.

41.

Translation — There is a feeling of one being like Shiva.

Exposition — A great person who is successful in delivering consciousness from the womb of the body becomes time conscious, and thus he behooves the son of time and becomes himself like time or Shiva.

42.

Translation — Inner self becomes a stage.

Exposition — A great person who develops consciousness that unites with time, the creator, the supporter and the annihilator of world becomes himself like time. Having united with one who manifests all, the entire world becomes an act being played on the stage of his inner self.

43.

Translation — Senses become witnesses.

Exposition — The great time — conscious person, on the stage of inner self of whom is this entire act of creation being played, all senses of such a great person become the witnesses of this omnipresent play and such time – conscious great person remains in bliss while witnessing everywhere this play of time.

44.

Translation — Consciousness becomes sublime when imagination is mastered.

Exposition — Imagination of a great person, who becomes time conscious is completely compliant to him. He has already realized that the most powerful force in this creation is imagination only and controlled force of imagination is called as will power. Practice also begins with imagination and it is only a process of developing confidence in one’s ability of doing something as per one’s imagination. Successful practice that takes place by applying controlled force of imagination is called as power. After becoming powerful, a yogi is established in sublime consciousness, the root of the consciousness that lies beyond sound and sight.

45.

Translation — Siddha (perfect being) has independent existence.

Exposition — The great man who becomes time – conscious by mastering his own imagination acquires independent existence in this world. He knows that all human beings complete the journey of their life by remaining compliant to various imaginations as they don’t master imagination and are not able even to imagine their own sublime existence until they actually realize it. He who uses his body for delivering consciousness becomes time conscious after delivering sublime consciousness through the medium of body and becoming one who has absolute existence and independence.

46.

Translation — As here, so is everywhere.

Exposition — One who applies will power i.e. a controlled flow of imagination, and by using his body as a womb for the conscious seed of the mind delivers sublime conscious presence, he becomes time–conscious and then becomes familiar with all mysteries of universe. Together with a consciousness that has united with time, a super human, during his lifetime becomes time conscious and remains in existence in this visible world. He similarly remains in existence beyond the realm of body and visible world in union with conscious time even after the journey of body is over. For him there remains no difference between existence & non-existence, birth and death, knowing and not knowing because he has realized of their relativity.

47.

Translation — Contemplation of origin.

Exposition — A great man who, by developing and delivering consciousness through medium of his body realizes the time, which creates the universe from its womb, supports it and also absorbs it in himself, the time that is origin of everything. He, while witnessing everywhere the play of time, is positioned in contemplation of entire seed of everything — the time, by becoming time conscious himself.

48.

Translation — Contended by totally knowing heart (is the mind).

Exposition — One who realizes the origin of all by applying controlled force of imagination i.e. will power, masters imagination and by delivering immensely developed consciousness from the womb of his body, he becomes time conscious. He is contended by knowing everything because he has no more yearning for knowledge and he then remains with independent existence in the visible world.

49.

Translation — His achievement is to make rules for himself.

Exposition — One who delivers his consciousness in its entire immensity by developing it through its absolute immensity in his womb of his body, remains established together with the consciousness that has united with time, the origin of all. Having united with him who manifests all, he is at liberty to do anything. He himself authors his own norms of pleasure, follows them himself and also discards those norms himself. Such time conscious super human while being established beyond all norms of visible world is established in himself.

50.

Translation — Existence is eternal but life has end.

Exposition — He, who has realized his existence beyond birth and death, i.e. he, who plants a seed of consciousness in his body using it like a womb, develops the consciousness completely and then delivers it through the medium of death. He experiences his existence in the un-manifested that lies beyond the realm of physical limitations and the limitations of the visible world. Eventually when he has united with the time together with his completely developed consciousness, he no more need to avail of another life, or said differently he doesn’t need to seek a body in order to develop consciousness

51.

Translation — “Ka” group and other words are elementary hints by worshipers of Shiva for the inane ones.

Exposition — Words present us with a great gift of memory. Great persons who worshipped Shiva, i.e. time, for knowing him in his elements, preserved by means of words in the nature of hints all their experiences with compassion, just as they realized him in his elements for all those, who, by understanding these hints would be prepared to use the controlled force of their imagination to know for themselves the great time by means of developing consciousness through the medium of the body.

(Note – “Ka” group here includes all 52 consonants in Sanskrit)

52.

Translation — Fourth, beyond the three should be extracted like essence.

Exposition — A person, who is ambitious of knowing Shiva or The Supreme Time, Mahakal in its element, along his pursuit begins to study and understand those hints that are preserved by ancient time-conscious great persons in memory by means of words. When he begins to understand those hints, he performs extremely hard practice of yoga by means of his body for developing consciousness. Mighty practice of yoga kindles intense fire of yoga in his body and his consciousness begins to stay established in the unmanifest by overcoming physical limits.

First, Study of hints preserved in memory by means of words, second, mighty practice of yoga through the medium of body, subsequent to rudimentary understanding of those hints and third, establishment of consciousness in the un-manifest subsequent to its development and its expansion beyond the physical limits.

Fourth sate i.e. the consequence of the above three is to know time in its element and by uniting with it to become time-conscious oneself. Just as the essence of a substance is extracted in the form of oil, much in the same way the essence of above three states is to be established in the fourth state that lies beyond the above three.

53.

Translation — Absorbed, he enters his own mind.

Exposition — Subsequent to knowing Shiva — the Time, the great person who becomes like Shiva or becomes time-conscious awakens his consciousness completely and by concentrating that into the sublime consciousness that manifests consciousness, he enters into it. In other words it may be said that by awakening his consciousness, he becomes time-conscious and enters into his own mind.

54.

Translation — Behavior becomes like shiva and causes equanimity.

Exposition — He unites with Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal, the soul of all, the time that manifests the entire world, supports it and then absorbs it within itself by destroying it. Then, his conduct is at par with Shiva and such visionary, beholding himself in everything beholds uniformity.

55.

Translation — At the end of middle, birth takes place.

Exposition — When consciousness develops completely while developing into the womb of body between birth and death, then along with the end of the body is born a completely developed state of consciousness and the end of the process of taking on a body takes place along with the birth omniscient of consciousness.

56.

Translation — Concentration into the origin of creation causes knowledge of why it is destroyed and created again.

Exposition — He who becomes successful in delivering consciousness through the medium of his body is established in the unmanifest that lies beyond physical limits. And after knowing the reason of creation of the body, he concentrates his awakened consciousness on to the cause of creation of the visible world and thereby he knows the cause of destruction of the entire world as also its subsequent recreation. He then remains united with the creator.

57.

Translation — He becomes like Shiva.

Exposition — The great person, who, by concentrating the total consciousness of his mind that is replete with yogic powers knows why after the creation from the conscious void through the support of corporal matter, there is a merger of entire visible world into the conscious void itself. As a consequence of this knowledge he becomes one with Time — an element, which manifests the void that pervades in the almighty void and, which through the medium of void, manifests this visible world.

58.

Translation — Existence of the body itself is obeisance.

Exposition — Existence of the body of such a great person being visible is itself an obeisance directly towards Shiva or Time. Inspired by this, other persons also become ambitious to completely develop and deliver the immense consciousness of mind through the medium of their own body to know the original cause of the creation.

59.

Translation — Description is remembrance.

Exposition — Exposition of the result of practicing the means of attaining that state by a time-conscious or a Shiva- like person is like remembrance that takes place through the medium of body of such a great person.

60.

Translation — Charity is to give self-knowledge.

Exposition — Existence of the body of a Shiva like, conscious man is an obeisance, exposition by him of the ultimate element is remembrance and inspiring others for self-realization by his own example and bestowing upon them the process of delivering consciousness through the medium of body is like gracing them with self-realization.

61.

Translation — One, who is established here, is the inspiration of knowledge.

Exposition — A great person, who by means of union of his own mind and body delivers immense consciousness in this manner, remains in visible existence and while being a source of inspiration for others he becomes a inspiration for realization.

62.

Translation — Creation is a treasure of one’s own realization.

Exposition — One who knows Him, who manifests the complete world, the essence of all, Shiva — The Supreme Time, Mahakal, in his element by concentrating omnipotent consciousness that is born out of the union of his mind and body, at last gets united with Him. He then beholds himself manifested in the entire creation and the entire visible and invisible creation becomes just like a direct evidence of his realization.

63.

Translation — Absorption (Laya) in a state.

Exposition — He, who himself knows the entire creation by means of manifestation of realization, is established with a consciousness that is in union with all and is eventually absorbed in The Supreme Time, Mahakal who manifested himself through the medium of all. Then, there remains no difference between him and The Supreme Time, Mahakal.

64.

Translation — When this experience happens, resignation sets in.

Exposition — A great man, who becomes united with time, has all his ambitions, wishes and hopes fulfilled and then he becomes resigned even to the feeling of being completely satisfied and is established above all the hopes.

65.

Translation — Imagination then remains beyond delight and distress.

Exposition — When the hope of gaining happiness from the thought of procuring something comes to an end, the great man who has already united with All, knows the basic cause of imagination. He becomes like one who has his consciousness absorbed into Him, who manifest all imagination and remains established as such.

66.

Translation — Sublime state emerges after liberation from it.

Exposition — A great person who is liberated from all thoughts knows their creator, the Time, in its element and he in a state of sublime consciousness, remains visible until the end of the journey of the body and remains invisible after the journey of the body is over. He has already known during his union with time that this entire visible creation as well as invisible creation is but an imagination of Time.

67.

Translation — Realized person is aloof from delusion.

Exposition — A yogi who is able to deliver the daughter of mind (i.e. consciousness), from the womb of body by successfully developing consciousness, is established beyond all imaginations and becomes free from all imaginary delusions. He is able to understand that, imagination may imagine up to any extent, imagination is always distinct from the reality and it is impossible to imagine reality without realizing reality and yet the imagination of knowing reality is the cause of starting action that develops consciousness in the womb of the body. He, who knows this, develops omnipotent consciousness inside the body and delivers it and beyond all attachments and delusions, he, together with omniscient consciousness unites with the Time that manifests all.

68.

Translation — Origin of the effort ends in realizing the invisible.

Exposition — In the beginning a thinker, who is inspired by the thought of knowing the truth of his existence, begins his efforts of knowing the truth. As a result of this he realizes the relationship of the body and the mind for the complete development of consciousness i.e. the daughter of mind, and the body, he is able to imagine Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal, a truth that is invisible and is beyond the realm of imagination. By knowing Shiva in essence, he becomes one who has his consciousness dissolved in time, or we may say that he realizes the invisible that is beyond the visible creation.

69.

Translation — Power of body is an experience of being.

Exposition — Mind, which remains invisible and takes on a body, is itself a means of experiencing the strength that enables one to achieve something by means of the body. Feeling of being originates in the mind. A mind, which plays with the body, and plants a seed of consciousness in the womb of the body and develops it and after the delivery of totally developed consciousness and knowing by using it, the Time that manifests all, the time that is imagination of all imaginations and the essence of all. Eventually by knowing Time he becomes like Shiva.

Those, who consider that this body is passive, do not realize that this is that root, which when sprinkled by mind, blossoms into a creeper on which blooms the flowers of knowledge that arises out of experience.

70.

Translation — Shiva is the original cause of these three.

Exposition — It is the Shiva that causes the union of mind, body and developed vast consciousness; He is the basis of all their activities. He is manifested in the body through the medium of breaths and in the mind, in the form of consciousness.

71.

Translation — The capacity of body follows the state of realization.

Exposition — By taking support of the soul through the medium of mind and body and after knowing Shiva — The Supreme Time, Mahakal that manifests all by awakening his consciousness, a yogi becomes like Shiva. His body becomes divine and is a clear indication towards Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal. Physical appearance of such a great person is an inspiration for others and is a direct indication towards the great omnipotent time – Shiva himself.

72.

Translation — Mere wishing takes them out.

Exposition — The great yogi, who has successfully developed and delivered consciousness – the daughter of mind, by means of his body and who has been able to know Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal, then becomes capable of leaving his body merely by wishing.

73.

Translation — When established in true knowledge, he is no more; thereby life also is no more.

Exposition — A yogi, who successfully delivers vast dormant consciousness of the mind through the medium of his body, becomes capable of forsaking existence of the body yogically, merely with a wish. Knowing the very cause of the birth and the death and the creation and the destruction of the entire creation, he is able to know his essence, the Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal. When such great time-conscious person leaves his body yogically, his visible physical existence is over and his mind that is the cause of birth of consciousness and the basis of relationship with the body also submerges into its origin.

74.

Translation — Then liberated from the coverings of all elements, he becomes like Maheshwar, the cause of creation and destruction of all.

Exposition — The great person, who is successful in causing birth of consciousness, i.e. the daughter of mind, by completely developing it in the womb of the body, knows in essence as the Shiva — The Supreme Time, Mahakal, and the one who supports, manifests and then destroys the entire creation. He then concentrates his awakened consciousness in Shiva and unites with him and by uniting with The Supreme Lord (Maheshwar) he becomes Supreme Lord himself.

75.

Translation — Prana (Shiva) is naturally related.

Exposition — Shiva creates the entire world, supports it and then destroys it when its time is over. That The Supreme Time, Mahakal manifests itself as Shiva. He is himself the life of the entire world. The life of great persons who realize him through the medium of death gets dissolved in him only. Everything has a natural relation with the Shiva who is, as if not there, although he is there and is experienced in the form of time in the creation.

We experience time all the time and yet it remains beyond all experiences. It is only when the consciousness is totally developed can one realize the time in its truth and can be one with time. The life of all has a natural relationship with the supreme element i.e. Time. Soul is manifested from time only and is absorbed again only in time. Mighty conscious void that supports all is also manifested from The Supreme Time, Mahakal. Void is one with time and time is the essential consciousness of that conscious void and is present in the conscious void. Coitus between the Time and the Conscious Void created the Conscious Matter, which is the body of the visible whose essence is the void that supports all movements of conscious matter that remains untouched by it. Life of matter as well as the conscious void is The Supreme Time, Mahakal itself, and Time is there in everything and yet remains beyond from all forever.

The author of these precepts, who himself realized time, has indicated in the next precept how those great yogis realized the life of all, the Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal, by developing their consciousness in the womb of the body. And then, how they proceeded to develop their consciousness and realized Him, the essence of all.

76.

Translation — Doing Sanyam (i.e. intense meditation) at the inside end of the nostril causes knowledge of mutually opposite activities of “Prana” (incoming and outgoing breath) and “Sushumma” (the lull between the two) and that of positioned “Sushumna”.

Exposition — By means of doing Sanyam into the scull cavity at the meeting point where nasal holes terminate inside the scull bowl with the help of the Khechari mudra, determined to realize Shiva – The Supreme Time, Mahakal, who is there as the essence of the conscious void inside of the scull cavity, and by concentrating the total consciousness in Shiva, one gets the result of realizing Time that is manifested through the medium of void in the form of essence of life.

In the process of realizing this consequence, the mutually opposite states of Prana (known as Prana & Apana) are realized in their truth. After realizing their natural activity that is mutually opposite to each other, becomes quiescent, and yogi experiences the quiet state of life. This quiescent state of Prana (which is described by yogis as admission of Prana in Sushumma) gives direct perception of The Supreme Time, Mahakal and is therefore itself like Time. In this quiescent state of life he directly experiences Shiva – the supreme lord, i.e., the form of Time, as brilliant as sun, the brilliance of brilliances, extremely dazzling, the essence of all and then the yogi knows Him and becomes tranquil.

77.

Translation — All doubts are absorbed into their origin.

Exposition — A yogi who directly observes him, who is the brilliance of all brilliance, the extremely brilliant, the soul of all, the supreme being, the supreme lord Shiva and knows him in his element has his consciousness united with Shiva. All doubts of such a great person, which originated from the womb of Time only, are absorbed again only in Time by being one with Time.

The material is taken from http://www.siddhasiddhanta.com/index.html

http://www.shailendrasharma.org/shiva-sutras

डॉ. नीरज राय

डॉ. नीरज राय

कैसे हुआ शोध

कैसे हुआ शोध

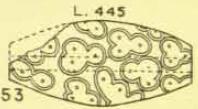

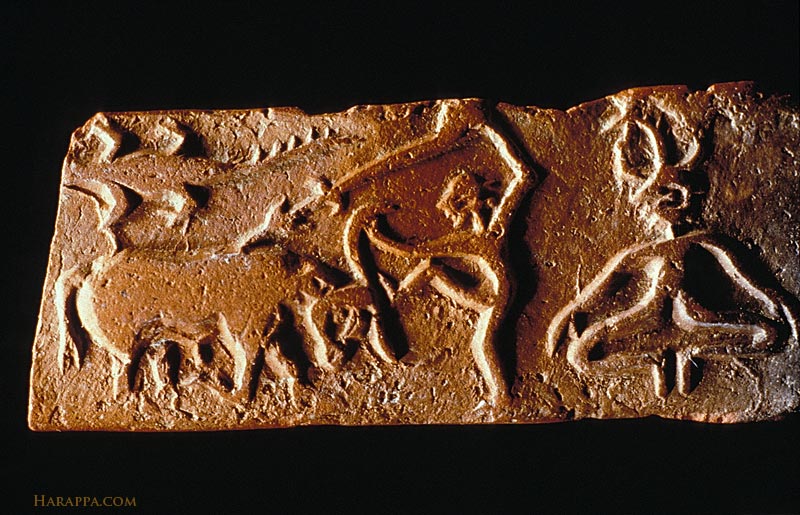

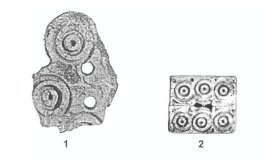

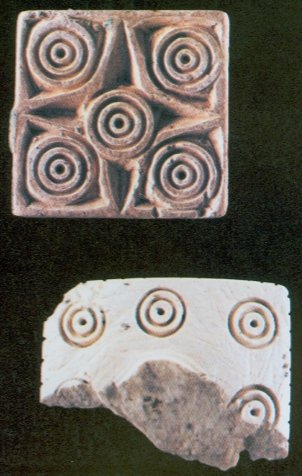

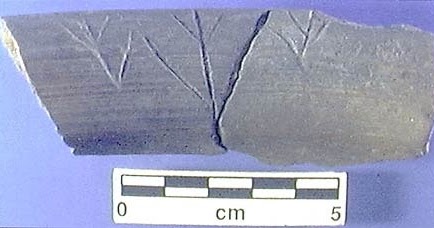

m0489 Obverse side of a two-sided tablet.

m0489 Obverse side of a two-sided tablet.

Sohgaura coper plate inscription. ca. 7th cent.BCE Pre-Mauryan.

Sohgaura coper plate inscription. ca. 7th cent.BCE Pre-Mauryan.

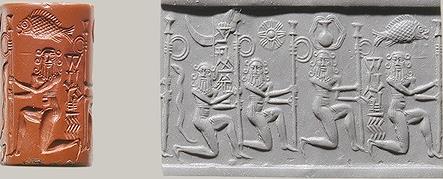

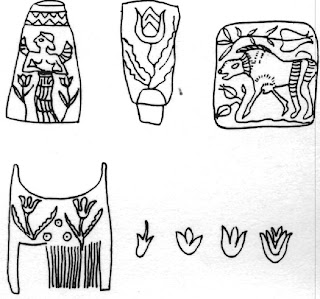

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

paśu'cow' rebus: pasra 'smithy, forge'phaḍaफड ''cobra hood' rebus: फड 'manufactory, company, guild] kolom'three' rebus: kolilmi 'smithy, forge'.

paśu'cow' rebus: pasra 'smithy, forge'phaḍaफड ''cobra hood' rebus: फड 'manufactory, company, guild] kolom'three' rebus: kolilmi 'smithy, forge'.

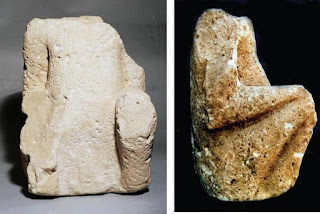

Lime stone sculpture

Lime stone sculpture

The stern man (top) and lady (bottom) of L-Area

The stern man (top) and lady (bottom) of L-Area

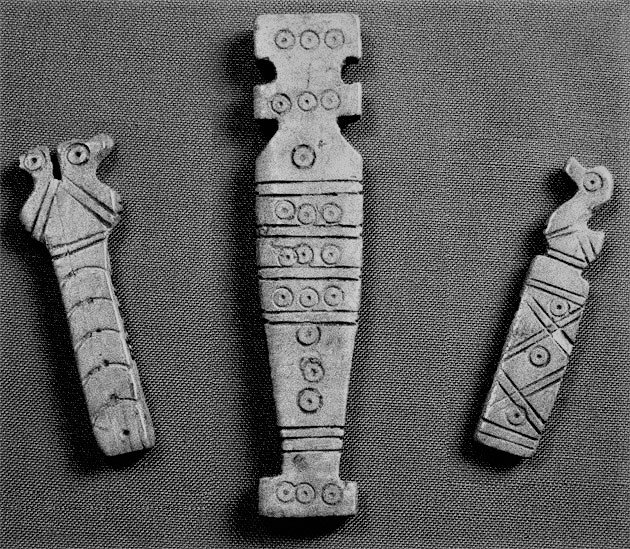

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

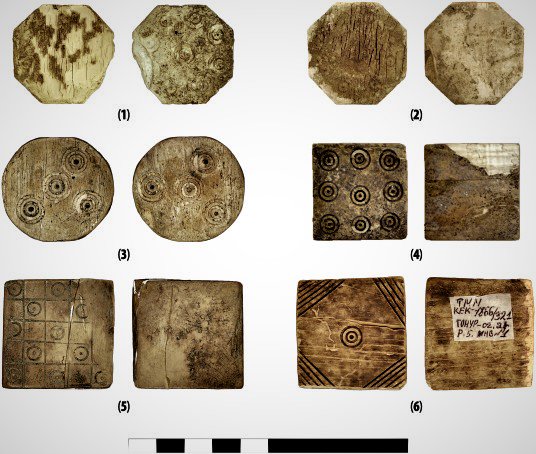

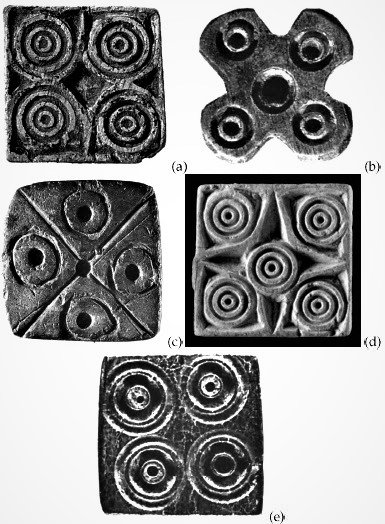

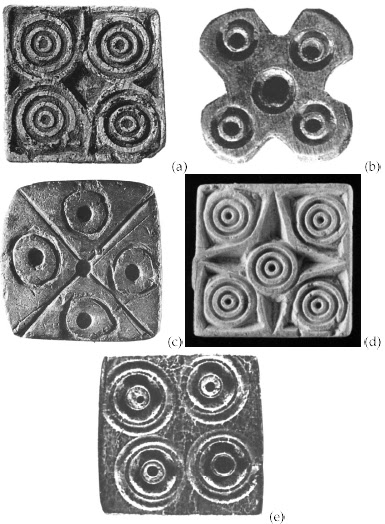

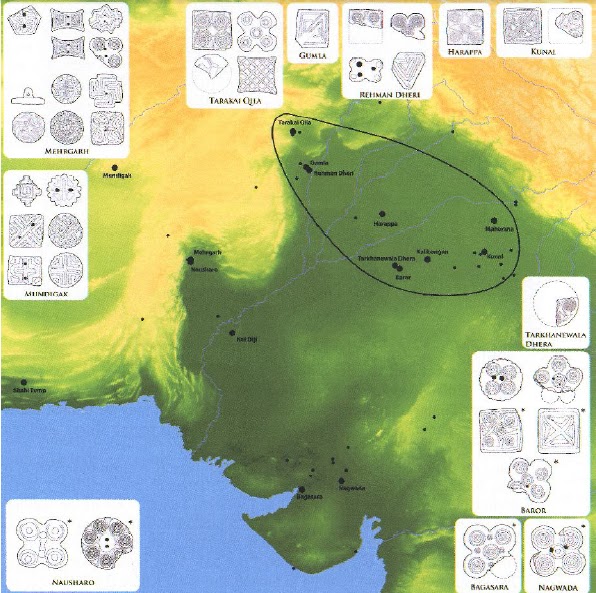

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p=

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p=

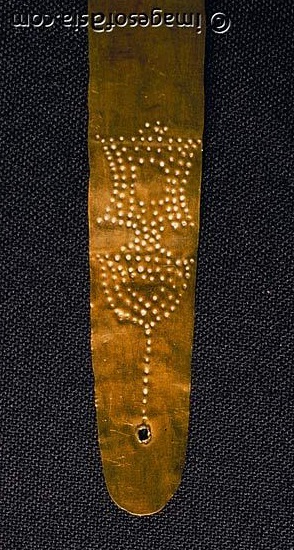

Gold f

Gold f

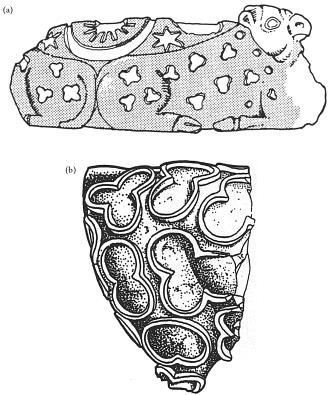

Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).

Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).

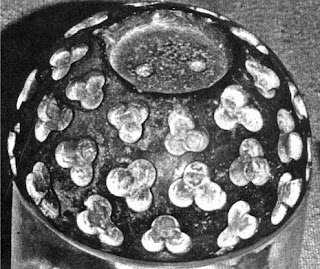

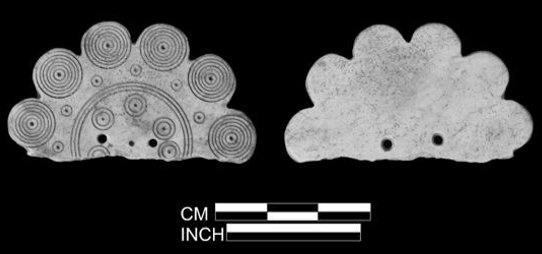

--510x286.jpg) Found in a tomb in Tell Abraq

Found in a tomb in Tell Abraq

Focus on the center-piece: brazier PLUS eye PLUS eyelid PLUS horns of markhor:

Focus on the center-piece: brazier PLUS eye PLUS eyelid PLUS horns of markhor:

Dholavira. Stone statue.

Dholavira. Stone statue.