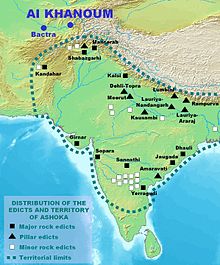

This is a tribute to Paul Bernard, Remy Audouin, Osmund Bopearacchi who have contributed to the identification of worship of Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva कृष्ण-वासुदेव, Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma सङ्कर्षण बलराम, by Greek kings of 2nd century BCE on ancient coins from Al Khanoum, Afghanistan.

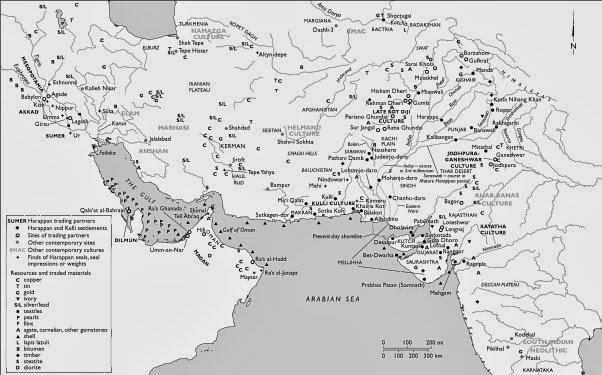

Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva कृष्ण-वासुदेव, Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma सङ्कर्षण बलराम are artisans with expertise in metalwork and farmwork and signifiers of creation of wealth of the nation. Ancient Arthaśāstra (Economic history) in Bhāratīya Itihāsa from 4th millennium BCE, from the time Indus Script signifiers documented wealth-creation has to be retold to explain why Ancient India accounted for 32% of the world GDP (pace Angus Maddison).

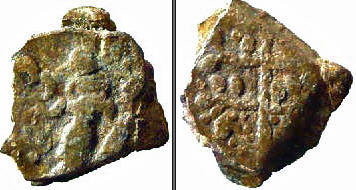

The coins dug up by Paul Bernard and the French archaeological team (embedded summary report) signify Indus Script hypertexts in the context of cataloguing wealth production in mints and metallurgical competence of metalworkers of the Bronze Age. This validates the claim made elsewhere that almost all punch-marked coin symbols are Indus Script hypertexts to signify such wealth accounting ledgers.

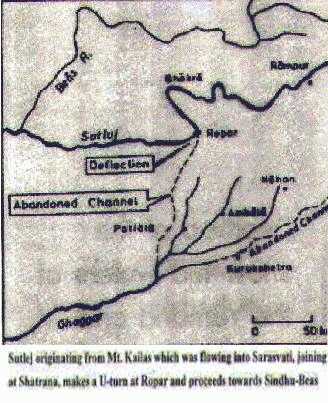

The roles of Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva कृष्ण-वासुदेव, Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma सङ्कर्षण बलराम in Bhāratīya Itihāsa are documented in the ancient text narratives of Mahābhārata. In 200+ ślokas of śalyaparvan, the pariyātrā of Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma is detailed. During this pilgrimage journey for 42 days from Prabhasa (Somnath) to Plakṣapraśravaṇa (Himalayan glacier source of Vedic River Sarasvati near Har-ki-dun), he meets with his youngr brother Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva कृष्ण-वासुदेव. Together they watch the gadāyuddha, between Duryodhana and Bhīma. Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma सङ्कर्षण बलराम informs Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva कृष्ण-वासुदेव that he would not participate in the ongoing war and returns to Dwārakā (Bet Dwāraka) in Gujarat Rann of Kutch. The witnesses to the gadāyuddha are enshrined in a sculptural monument of Angkor Wat. (The monument taken to USA was returned in 2016).

![Image result for angkor wat bhima duryodhana gadayuddha sculpture]()

The reality of Vedic River Sarasvati has been established and Veda roots of the seafaring merchants and artisans have been validated with the discovery.of Binjor yajnakuṇḍa with an aṣṭāśri Yūpa and inscribed Indus Script seals documenting wealth-creating metalwork catalogues.

![]()

![]() Binjor Yūpa, Binjor seal

Binjor Yūpa, Binjor seal

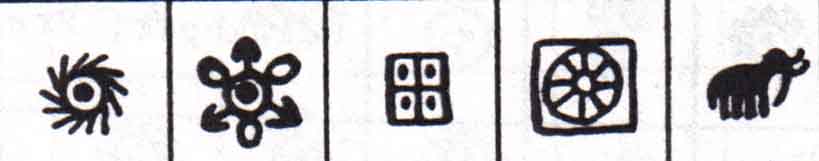

The hypertexts identified from Al Khanoum coins are: 1. phaḍa'cobra hood'; 2. kaṇī 'pupil of eye',kaṇa, °ṇā ʻeye of seed'; 3. hala'ploughshare'.

These are also read as Rajane in Brahmi as on another Agathocles coin:

![File:AgathoklesCoinage.jpg]() Coin of Agathokles, king of Bactria (ca. 200–145 BC). British Museum.

Coin of Agathokles, king of Bactria (ca. 200–145 BC). British Museum.Inscriptions in Greek. Upper left and down: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ (VASILEOS AGATHOKLEOUS)

Rev Lakshmi, a Goddess of abundance and fortune for Hindus & Buddhists, with Brahmi legend Rajane Agathukleyasasa "King Agathocles". ![]()

An six-arched hill symbolsurmounted by a star.Kharoṣṭhī legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Tree-in-railing, Kharoṣṭhīlegend Hirañasame (Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Bopearachchi, p.176) The symbols used together with Kharoṣṭhī legends are Indus script hypertexts: dang 'hill range' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' med 'polar star' rebus: med 'iron'; khaṇḍa 'divisions' rebus: kaṇḍa 'equipment', kolom 'three' kolmo 'rice plant' rebus; kolimi 'smithy. Thus, the hypertexts signify the metallurgical competence of the mint with smithy/forge working in iron and metal implements. Hence, the message 'hiranasame' which means 'wealth like gold' (of the mintwork and products from the mint).![File:Bilingual Coin of Agathocles of Bactria.jpg]() Coin of Agathocles of Bactria.Obv: Arched hills surmounted by a star (Read as Indus Script hypertexts:dang 'hill range' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' med 'polar star' rebus: med 'iron') . Rev: Trisula symbol, Kharoshthi legend HITAJASAME "Good-fame-possessing" (lit. meaning of "Agathocles").Source: From "Coins of the Indo-Greeks", Whitehead, 1914 edition, Public Domain. The mint of Al Khanoum proclaims its wealth-producing metallurgical repertoire on the Indus Script messageon the coin.

Coin of Agathocles of Bactria.Obv: Arched hills surmounted by a star (Read as Indus Script hypertexts:dang 'hill range' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' med 'polar star' rebus: med 'iron') . Rev: Trisula symbol, Kharoshthi legend HITAJASAME "Good-fame-possessing" (lit. meaning of "Agathocles").Source: From "Coins of the Indo-Greeks", Whitehead, 1914 edition, Public Domain. The mint of Al Khanoum proclaims its wealth-producing metallurgical repertoire on the Indus Script messageon the coin. Coin of Agathocles

'

Obv Balarama-

Samkarshana with Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ.(

VASILEOS AGATHOKLEOUS)

While accepting 'rajane' as a valid Brāhmī reading on the coin, I suggest an alternative reading for the Brahmi syllabic sequence of the word 'rajane'. treating the 3 symbols on the right side of the coin as Indus Script hypertexts, because the symbol for 'ja' is not clear as a symbol on the Al Khanoum coin signifying Śri Kr̥ṣṇa, Śri Balarāma..

![]() The symbol used is more like 'pupil of the eye' (which is NOT a Brahmi syllable)..

The symbol used is more like 'pupil of the eye' (which is NOT a Brahmi syllable)..

The rebus renderings in Indus Script cipher and meanings are:

1. phaḍa'cobra hood' rebus: phaḍa फड 'manufactory, company, guild', paṭṭaḍi'metals workshop'.

2. kaṇī 'pupil of eye', kaṇa, °ṇā ʻeye of seed' PLUS vr̥tta'circle' rebus: kampaṭṭam, kaṇvaṭṭam, 'mint, coiner, coinage' கண்வட்டம் kaṇ-vaṭṭam , n. < id. +. 1. Range of vision, eye-sweep, full reach of one's observation; கண்பார்வைக்குட்பட்ட இடம். தங்கள் கண்வட்டத்திலே உண்டுடுத்துத்திரிகிற (ஈடு, 3, 5, 2). 2. Mint;நாணயசாலை. கண்வட்டக்கள்ளன் (ஈடு.). Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

The hypertext composed of two combined hieroglyphs (spoked wheel with sharp edges or fish-fin endings on spokes) PLUS pupil of eye are read together. The ligatured spoked wheel is: vaṭṭa PLUS arā, i.e. circle PLUS spokes PLUS ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish fin' rebus: kammaṭa,'mint, coiner, coinage'. Thus, together, the unique orthography of the spoked wheel is read as: ayo kammaṭa vaṭṭhara'alloy metal mint, exclusive area of community, enclosed piece of ground earmarked for metal-, mint-work'. वठार (p. 423) vaṭhāra m C A ward or quarter of a town. वाडगें (p. 433) vāḍagēṃ n (Dim. of वाडी) A small yard or enclosure (esp. around a ruined house or where there is no house). वाडा (p. 433) vāḍā m (वाट or वाटी S) A stately or large edifice, a mansion, a palace. Also in comp. as राज- वाडा A royal edifice; सरकारवाडा Any large and public building. 2 A division of a town, a quarter, a ward. Also in comp. as देऊळवाडा, ब्राह्मण- वाडा, गौळीवाडा, चांभारवाडा, कुंभारवाडा (Marathi) Shown together with the pratimā of कृष्ण-वासुदेव , the hypertext is read as: cakrā yudha 'discus weapon' and ayo kammaṭa vaṭṭhara 'alloy mint quarter of town'. For orthographic variants of the spoked-wheel on thousands of punch-marked coins, see: Vajra and Indus Script ivory hypertexts on a seal, ivory artifactshttps://tinyurl.com/y85goask

3. hala'ploughshare' Cognate Meluhha phonetic forms: araka a plough with bullocks, etc. complete. Malt. are a plough. (DEDR 198) hal 'plough' (Santali) phāla [mod. Ind. phār] 'ploughshare'. It is possible that a hieroglyph (apart from the orthographic shape of the plough) which signifies the word is: pāla, 'rice seedling' (Kui). I suggest that on the coin, this symbol signifies phāla 'ploughshare' (which is a semantic expansion of araka, hala'plough handle'). ![]()

![]()

![]() The other hieroglyphs on the Al Khanoum coins of Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva, Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma are: musala 'pestle', śankha 'conch', chhatra'parasol', पट्टा (p. 273) paṭṭā m ( H) A kind of sword. It is long, twoedged, and has a hilt protecting the whole fore arm. Applied also to a wooden sword for practice and sports. This signifier is also read as a semantic determinative rebus: phaḍa फड 'manufactory, company, guild'; paṭṭaḍi 'metals workshop'.

The other hieroglyphs on the Al Khanoum coins of Kr̥ṣṇa Vāsudeva, Sankarṣaṇa Balarāma are: musala 'pestle', śankha 'conch', chhatra'parasol', पट्टा (p. 273) paṭṭā m ( H) A kind of sword. It is long, twoedged, and has a hilt protecting the whole fore arm. Applied also to a wooden sword for practice and sports. This signifier is also read as a semantic determinative rebus: phaḍa फड 'manufactory, company, guild'; paṭṭaḍi 'metals workshop'.

These hypertexts and their meanings are posited and a framework indicated for Economic narrative of wealth-creation in Bhāratīya Itihāsa from 4th millennium BCE.

Pāṇini and Patañjali mention temples which were called prāsāda-s. This word in Pali is pāsāda, pasada as in lohapasada, 'palace of metal'. prāsāda m. ʻ lofty seat or terrace ʼ ŚāṅkhŚr., ʻ lofty mansion ʼ MBh. [√sad?]

Pa. pāsāda -- m. ʻ lofty platform, terrace, high building ʼ; Pk. pāsāya -- m. ʻ palace ʼ; Si. pahaya, pāya ʻ mansion, palace ʼ. (CDIAL 8971)

The right-most glyph on line 2 of the seal impression is a 'plough' circumscribed by four 'splinter' glyphs. The plough is decoded rebus: Glyph: மேழி mēḻi , n. cf. mēdhi. [T. K. M. mēḍi.] 1. Plough; கலப்பை. வினைப்பக டேற்ற மேழி (புறநா. 388). 2. Plough-tail, handle of a plough; கலப்பையின் கைப்பிடி. மேழி பிடிக்குங் கை (திருக்கைவழக்கம், 22).Ta. mēr̤i plough, plough-tail, handle of a plough; mēr̤iyar agriculturalists. Ma. mēr̤i, mēññal ploughtail. Ko. me·y handle of plough. Ka. mēṭi, mēṇi plough-tail. Te. mē̃ḍi, (K.) mēḍi hind part or handle of a plough. Konḍa mēṛi plough handle, plough-tail. Kuwi (F.) mēri plough handle; (Isr.) mēṛi id., plough. (DEDR 5097).Compare with plough used by Sumerians.

Ta. araka a plough with bullocks, etc. complete. Malt. are a plough. (DEDR 198) Ka. maḍike a kind of harrow or rake. Te. maḍãka plough with bullocks complete. (DEDR 4656) Ta. ñāñcil, nāñcil plough. Ma. ñēṅṅōl, nēññil plough-shaft. Ko. ne·lg plough. Ka. nēgal, nēgil, nēgila id. Koḍ. ne·ŋgi id. Tu. nāyerů id. Kor. (T.) nēveri id. Te. nã̄gali, nã̄gelu, nã̄gēlu id. Kol. na·ŋgli, (Kin.) nāŋeliid. Nk. nāŋgar id. Nk. (Ch.) nāŋgar id. Pa. nã̄gil id. Ga. (Oll.) nāŋgal, (S.) nāngal id. Go. (W.) nāṅgēl, (A. SR.) nāngyal, (G. Mu. M. Ko.) nāŋgel, (Y.) nāŋgal, (Ma.) nāŋgili (pl. nāŋgisku) id. (Voc. 1956); (ASu.) nāynāl, (Koya Su.) nāṅēl, nāyṅēl id. Konḍa nāŋgel id. Pe. nāŋgel id. Manḍ. nēŋgel id. Kui nāngeli id. Kuwi (F.) nangelli ploughshare; (Isr.) nāŋgeli plough. / Cf. Skt. lāṅgala-, Pali naṅgala- plough; Mar. nã̄gar, H. nã̄gal, Beng. nāṅgal id., etc.; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11006.(DEDR 2907) lāˊṅgala n. ʻ plough ʼ RV. [→ Ir. dial of Lar in South Persia liṅgṓr ʻ plough ʼ Morgenstierne. -- Initial n -- in all Drav. forms (DED 2368); PMWS 127 derives both IA. and Drav. words from Mu. sources] Pa. naṅgala -- n. ʻ plough ʼ, Pk. laṁgala -- , ṇa°, ṇaṁgara<-> n. (ṇaṁgala -- n.m. also ʻ beak ʼ); WPah.bhad. nã̄ṅgal n. ʻ wooden sole of plough ʼ; B. lāṅal, nā° ʻ plough ʼ, Or. (Sambhalpur) nã̄gar, Bi.mag. lã̄gal; Mth. nã̄gano ʻ handle of plough ʼ; H. nã̄gal, nāgal, °ar m. ʻ plough ʼ, M. nã̄gar, °gor, nāgār, °gor m., Si. nan̆gul, nagala, nagula. -- Gy. eur. nanari ʻ comb ʼ (LM 357) very doubtful.lāṅgalin -- .Addenda: lāṅgala -- : A. lāṅgal ʻ plough ʼ(CDIAL 11006)lāṅgūlá (lāṅgula -- Pañcat., laṅgula -- lex.) n. ʻ tail ʼ ŚāṅkhŚr., adj. ʻ having a tail ʼ MBh., ʻ penis ʼ lex. 2. *lāṅguṭa -- . 3. *lāṅguṭṭa -- . 4. *lāṅguṭṭha -- . 5. *lēṅgula -- . 6. *lēṅguṭṭa -- . [Cf. lañja -- 2. -- Variety of form attests non -- Aryan origin: PMWS 112 (with lakuṭa -- ) ← Mu., J. Przyluski BSL 73, 119 ← Austro<-> as.] 1. Pa. laṅgula -- , na° n. ʻ tail ʼ, Pk. laṁgūla -- , °gōla -- , ṇaṁgūla -- , °gōla -- n.; Paš. laṅgūn n. ʻ penis ʼ; K. laṅgūr m. ʻ the langur monkey Semnopithecus schistaceus ʼ; P. lãgur, lag° m. ʻ monkey ʼ; Ku. lãgūr ʻ long -- tailed monkey ʼ; N. laṅgur ʻ monkey ʼ; B. lāṅgul ʻ tail ʼ, Or. laṅgūḷa, lāṅguḷa; H. lagūl, °ūr m. ʻ tail ʼ, laṅgūr m. ʻ longtailed black -- faced monkey ʼ; Marw. lagul ʻ penis ʼ; G. lãgur, °ul (l?) m. ʻ tail, monkey ʼ, lãguriyũ n. ʻ tail ʼ; Ko. māṅguli ʻ penis ʼ (m -- from māṅgo ʻ id. ʼ < mātaṅga -- ?); Si. nagula ʻ tail ʼ, Md. nagū.2. Or. lāṅguṛa, nā° ʻ tail ʼ, nāuṛa ʻ sting of bee or scorpion ʼ (< *nāṅuṛa?); Mth. lã̄gaṛ, nāgṛi ʻ tail ʼ; M. nã̄goḍā, nã̄gāḍā, nã̄gḍā, nã̄gā m. ʻ scorpion's tail ʼ. 3. Sh.jij. laṅuṭi ʻ tail ʼ, Si. nan̆guṭa, nag°, nakuṭa. -<-> X lamba -- 1: Phal. lamḗṭi, Sh.koh. lamŭṭo m., gur. lamōṭṷ m. 4. Pa. naṅguṭṭha -- n. ʻ tail ʼ. 5. A. negur ʻ tail ʼ, B. leṅguṛ. 6. Aw.lakh. nẽgulā ʻ the only boy amongst the girls fed on 9th day of Āśvin in honour of Devī ʼ. Addenda: lāṅgūlá -- [T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 65, comparing lāṅgula -- ~ Pa. nȧguṭṭha -- with similar aṅgúli -- ~ aṅgúṣṭha -- , derives < IE. *loṅgulo -- (√leṅg ʻ bend, swing ʼ IEW 676)]

1. Md. nagū (nagulek) ʻ tail ʼ (negili ʻ anchor ʼ?). (CDIAL 11009)

ala 3 अल । हलम् (for ala 1 and 2 see al 1 and 2), f. a plough. Cf. āla.-böñü -बा&above;ञू&below; । हलदण्डः f. the main beam of a plough (Śiv. 1531), cf. al-böñü (s.v.); (?) a goad; hal 1 हल् । हलम् m. (sg. abl. hala 1 हल), a plough. A plough and a pestle are the weapons of Balarāma, the brother of Kṛṣṇa (K. 99), and also (Śiv. 13, 116) of the elephant-god Gȧnish or Gaṇēśa. (Kashmiri)

پاله pālaʿh, s.f. (3rd) A kind of plough-share. Pl. يْ ey. See سسپار ; پولک pū-lak, s.m. (2nd) A kind of double wedge for fastening the iron ploughshare to the frame of a plough. Pl. پولکونه pū-lakūnah; S هل hal, s.m. (2nd) The handle of a plough, a plough. Pl. هلونه halūnah. See یویه.(Pashto) Cp. Balūčī nangār] a plough S i.115; iii.155; A iii.64; Sn 77 (yuga˚ yoke & plough); Sn p. 13; J i.57; Th 2, 441 (=sīra ThA 270); SnA 146; VvA 63, 65; PvA 133 (dun˚ hard to plough); DhA i.223 (aya˚); iii.67 (id.).

-- īsā the beam of a plough S i.104 (of an elephant's trunk); -- kaṭṭhakaraṇa ploughing S v.146=J ii.59; -- phāla [mod. Ind. phār] ploughshare (to be understood as Dvandva) DhA i.395. (Pali)

![]() Santali glosses

Santali glosses

The word for 'hoe' in Sumerian: al 'hoe'. "The hoe (al), the implement whose destiny was fixed by father Enlil -- the renowned hoe (al)! Nisaba be praised!"

Part of yoke of a plough: "Stambha (also spelled as Skambha) - is used to denote pillar or column. In the context of Jain & Hindu mythology, it is believed to be a cosmic column which functions as a bond, which joins the heaven (Svarga) and the earth (Prithvi). A number of Hindu scriptures, including the Atharva Veda, have references to Stambha. In the Atharva Veda, a celestial stambha has been described as an infinite scaffold, which supports the cosmos and material creation." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stambha skambhá1 m. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV. 2. ʻ *pit ʼ (semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1). [√skambh] 1. Pa. khambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Pk. khaṁbha -- m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ; Pr. iškyöp, üšköb ʻ bridge ʼ NTS xv 251; L. (Ju.) khabbā m., mult. khambbā m. ʻ stake forming fulcrum for oar ʼ; P. khambh, khambhā, khammhā m. ʻ wooden prop, post ʼ; WPah.bhal. kham m. ʻ a part of the yoke of a plough ʼ, (Joshi) khāmbā m. ʻ beam, pier ʼ; Ku. khāmo ʻ a support ʼ, gng. khām ʻ pillar (of wood or bricks) ʼ; N. khã̄bo ʻ pillar, post ʼ, B. khām, khāmbā; Or. khamba ʻ post, stake ʼ; Bi. khāmā ʻ post of brick -- crushing machine ʼ, khāmhī ʻ support of betel -- cage roof ʼ, khamhiyā ʻ wooden pillar supporting roof ʼ; Mth. khāmh, khāmhī ʻ pillar, post ʼ, khamhā ʻ rudder -- post ʼ; Bhoj. khambhā ʻ pillar ʼ, khambhiyā ʻ prop ʼ; OAw. khāṁbhe m. pl. ʻ pillars ʼ, lakh. khambhā; H. khām m. ʻ post, pillar, mast ʼ, khambh f. ʻ pillar, pole ʼ; G. khām m. ʻ pillar ʼ, khã̄bhi, °bi f. ʻ post ʼ, M. khã̄b m., Ko. khāmbho, °bo, Si. kap (< *kab); -- X gambhīra -- , sthāṇú -- , sthūˊṇā -- qq.v.2. K. khambürü f. ʻ hollow left in a heap of grain when some is removed ʼ; Or. khamā ʻ long pit, hole in the earth ʼ, khamiā ʻ small hole ʼ; Marw. khã̄baṛo ʻ hole ʼ; G. khã̄bhũ n. ʻ pit for sweepings and manure ʼ.*skambhaghara -- , *skambhākara -- , *skambhāgāra -- , *skambhadaṇḍa -- ; *dvāraskambha -- .Addenda: skambhá -- 1: Garh. khambu ʻ pillar ʼ.(CDIAL 13639) *skambhadaṇḍa ʻ pillar pole ʼ. [skambhá -- 1, daṇḍá -- ]Bi. kamhãṛ, kamhaṛ, kamhaṇḍā ʻ wooden frame suspended from roof which drives home the thread in a loom ʼ. (CDIAL 13642) Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

Hieorglyph:Pa. palla, pāla seedlings. Ga. (S.2) palle rice seedling. Konḍa pala (pl. paleŋ) seedlings for transplantation. Pe. pāṛa seedling. Kui plaha id. Kuwi (Su. Isr.) pāla, (Ṭ.) pala rice seedling. / Cf. Halbi pāla seedling, and Turner, CDIAL, no. 7969, pallava-.

(DEDR 3996) pallava1 m.n. ʻ sprout, twig, blossom ʼ MBh.

Pa. pallava -- n. ʻ sprout ʼ, Pk. pallava -- m. ʻ sprout, leaf ʼ; Phal. palāˊ m. ʻ leaf ʼ; S. palī f. ʻ leaves of gram and peas (used as vegetable) ʼ; L. pallī f. ʻ green leaves of gram (similarly used) ʼ, P. pallhī f.; Ku. pālo ʻ vegetation ʼ, paluwā ʻ new shoots of trees (used as fodder) ʼ; N. pāluwā ʻ sprig, shoot ʼ; B. pālā ʻ twig, bundle of twigs ʼ; Or. pa(h)lā ʻ tiny hut made of leaves ʼ (rather than < pallī -- 1), (Ganjam) ʻ seedling ʼ; Bi. pallā, (SMunger) palaī ʻ leaf of the yoke of a plough ʼ, (N of Ganges) pālo ʻ yoke of a plough ʼ, Mth. pālā (semant. cf. páttra -- in Bi.); OAw. pālava ʻ sprout ʼ; H. pālau, °lā, palhā m. ʻ twig, tender leaves, leaves of jujube tree ʼ (whence ālā -- pālā m. ʻ leaves ʼ), palwā m. ʻ sprouts of sugarcane used for planting ʼ, palaī f. ʻ young branch or spray of a tree ʼ; G. pālav, °lɔ m. ʻ tuft of foliage ʼ, pālũ n. ʻ temporary shed of leaves ʼ, pāl m. ʻ tender shoots ʼ (?); M. pālav, °lā m. ʻ tuft of foliage, sprout ʼ, pālẽ n. ʻ foliage ʼ, pālvā m. ʻ green stick plucked from hedge ʼ, pālvī f. ʻ the sprouting of plants ʼ; Ko. pāllo ʻ sprout, bud ʼ, Si. palla, pl. palu.pallavayati.Addenda: pallava -- 1 [IE. *petlawos: √pet ʻ to spread out ʼ cf. Gk. pe/talon ʻ leaf, metal plate ʼ Burrow Tau vii 458]S.kcch. palī f. ʻ matted foliage of the jujube tree ʼ; WPah.poet. paulo m. ʻ leaf, bud, sprout ʼ, kṭg. paulṭi f. ʻ shoot of a tree ʼ.(CDIAL 7969)

Poughshare: phāˊla1 m. ʻ ploughshare ʼ RV., ʻ mattock ʼ R. [Cf. phala -- 5 n. ʻ ploughshare ʼ lex.: prob. conn. phálati2. Poss. < *spāla -- ~ Ir. *spāra -- in Pers. supār, Sar. spur (EVP 68). If so, it may have been influenced by Mu. or Drav. to account for early ph -- (cmpds. also show -- ph -- , not -- pph -- ): EWA ii 397 with lit. -- √phal]

Pa. Pk. phāla -- m.n. ʻ ploughshare ʼ, Wg. pāl, Kt. pōl, Dm. phal, Tir. phāl, Paš.chil. kuṛ. phāl, ar. āl -- päṛīˊ (halá -- ), Shum. phāl, ā̤l -- phäleik, Gaw. phāl, Kho. phal, Bshk. Tor. phāl, Sv. phal, Phal. phōl, Sh.pales. phāl; K. phāl m. ʻ ploughshare, metal blade of mattock &c. ʼ (cf. phal < phala -- 2); S. phāru m. ʻ ploughshare, steel edge of a tool ʼ; L. phālā m. ʻ ploughshare ʼ, awāṇ. phāl, P. phālā m., °lī f. ʻ small do. ʼ, WPah.bhal. phāl f., jaun. phāwā, (Joshi) fāḷā m., Ku. phālo, gng. phāw, N. phāli, A. B. phāl, Or. phāḷa, (Bastar) phāra, Bi. phār, Mth. phār, °rā, phālā, Bhoj. phār, H. phāl, °lā m., °lī f., phār, °rā m., M. phāḷ m.

*phālaghara -- ; *ardhaphāla -- , *dārvaphālaka -- , *niṣphālika -- , *baddhaphāla -- , *halaphāla -- .

Addenda: phāˊla -- 1: †*lōhaphāla -- . (CDIAL 9072) †*lōhaphāla -- ʻ ploughshare ʼ. [lōhá -- , phāˊla -- 1]

WPah.kṭg. lhwāˋḷ m. ʻ ploughshare ʼ, J. lohāl m. ʻ an agricultural implement ʼ Him.I 197; -- or < †*lōhahala -- .(CDIAL 11160a)

Point of ploughshare: dhāˊrā2 f. ʻ sharp edge, rim, blade ʼ RV., ʻ edge of mountain ʼ lex.

Pa. Pk. dhārā -- f. ʻ edge of weapon ʼ; NiDoc. cliuradhara ʻ knife -- blade ʼ; Ash. Wg. dā ʻ mountain, pass ʼ, Kt. då (→ Pr. dō NTS xv 257); Dm. dâr ʻ hill ʼ, Paš. dhār, Shum. Niṅg. dār, Woṭ. dār m., Gaw. d'ār f. (→ Kho. dahār ʻ ridge of hill ʼ Rep2 49), Sv. dhārē, Sh. (Lor.) dār ʻ ridge of hill ʼ; K. dār f. ʻ edge or point of weapon or tool ʼ, kash. dhār f. ʻ hill ʼ; S. dhāra f. ʻ edge of weapon or tool ʼ; L. dhār f. ʻ edge ʼ; P. dhār f. ʻ edge of weapon, ridge of mountain ʼ, bhaṭ. dhār ʻ hill ʼ; WPah. bhad. bhal. cur. dhār f. ʻ hill ʼ, khaś. (obl.) dhāra; Ku. dhār ʻ edge, ridge, summit of hill ʼ, dhāri ʻ edge, mouth (of mill) ʼ; N. dhār ʻ edge, blade of knife, cliff ʼ (whence dhārilo ʻ sharp ʼ); A. dhār ʻ edge of weapon, blade ʼ (whence dharāiba ʻ to sharpen ʼ), dhāri ʻ line, row ʼ; B. dhār ʻ edge, sharpness of a blade ʼ, dhāri ʻ edge, edge of mud veranda ʼ; Or. dhāra ʻ blade ʼ; Bi. dhār ʻ edge or point of ploughshare ʼ, dhārī ʻ deep furrow ʼ; Mth. dhār ʻ line ʼ; Bhoj. dhār ʻ curved blade of mattock ʼ; OAw. dhārī ʻ line ʼ; H. dhār f. ʻ edge, line, boundary ʼ, dhārī f. ʻ line, groove ʼ; G. M. dhār f. ʻ edge of tool, brink ʼ; Ko. dhāra ʻ sharpness ʼ; Si. daraya ʻ edge, sharpness ʼ. -- Kal.rumb. dar ʻ ridge -- pole ʼ or poss. < dāˊru -- 2.

*dhārāmr̥ttikā -- ; *ēkkadhāra -- , *caturdhāra -- , tīkṣṇadhāra -- , *tridhāra -- , *dārvadhāraka -- , *dudhāra -- , *pr̥ṣṭhadhāra -- , *māṁsadhārā -- , *sītādhārā -- .

Addenda: dhāˊrā -- 2: WPah.kṭg. (kc.) dhāˋr f. ʻ edge, mountain ridge ʼ, J. dhā'r f.; -- kṭg. dhàrkɔ ʻ steep, curved ʼ; dhàrṭi, dhàṭṭi f. ʻ ridge of a hill ʼ; Md. dāra ʻ edge ʼ ← G. M. dhār f. (CDIAL 6793)

![Image result for sumerian plough]() The seed plough was an invention of the Sumerians and is seen prominent in various cylindrical seals. It was called by Sumerians "gis.apin", (seed plough),

The seed plough was an invention of the Sumerians and is seen prominent in various cylindrical seals. It was called by Sumerians "gis.apin", (seed plough),

Compare with Greek plough.

Nisaba, Master Scribe & Goddess of Grains

![7c - gods teach mankind to plow]() Plough shown on Sumerian cylinder seals.

Plough shown on Sumerian cylinder seals.http://www.mesopotamiangods.com/the-debate-between-the-hoe-and-the-plow-translation/

![Image result for sumerian plough]() Isidore, the farm labourer's plough

Isidore, the farm labourer's plough

Isidore the Farm Labourer, also known as Isidore the Farmer, (Spanish: San Isidro Labrador), (c. 1070 – 15 May 1130) was a Spanish farmworker known for his piety toward the poor and animals. He is the Catholic patron saint of farmers and of Madrid and of La Ceiba, Honduras. His feast day is celebrated on 15 May. Thi plough was discovered by Subhas Chandra Bose (Netaji).

http://warehouse-13-artifact-database.wikia.com/wiki/Isidore_the_Laborer%E2%80%99s_Plough

"William Smith in 1875 decribes the ARATRUM a plow developed in Greece that "was by taking a young tree with two branches proceeding from its trunk in opposite directions, so that whilst in ploughing the trunk was made to serve for the pole, one of the two branches stood upwards and became the tail, and the other penetrated the ground, and, being covered sometimes with bronze or iron, fulfilled the purpose of a share.""

Compare with plough shown on Balarama image on a coin.

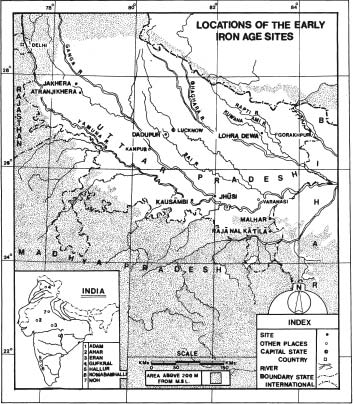

Sankarsana, the wielder of the plough, with the fan-palm as his emblem. Silver drachm of the Greco-Bactrian king Agathocles (190-180 BCE)found in the excavations at Al-Khanuram in Afghanistan.

Modern photo showing an Indian plough.

Harappa. h0146 seal.

![]() m0357

m0357

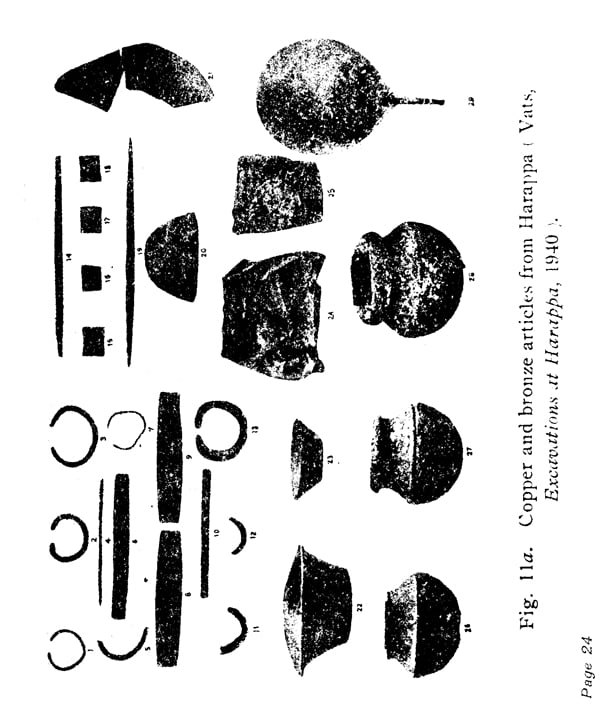

m0357 Text 1401 The 'fish' on this text and on a tablet (together with crocodile) seem to focus on the fins of fish and hence, signify. khambhaṛā ʻfinʼ rebus: kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Reading of Text 1401: karaNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNi 'supercargo' bhaTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' goTa 'round' rebus: khoTa 'ingot' PLUS kolom 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' tutha 'goad' rebus: tutha 'pewter' PLUS kolom 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' khambhaṛā ʻfinʼ rebus: kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint PLUS ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'.

Last three hieroglyphs as a distinct string: tutha 'goad' rebus: tutha 'pewter' PLUS kolom 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge' khaNDa 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implements' arA 'spoke' rebus: Ara 'brass' eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper'.

Excavations at Ai-Khanum, Afghanistan, conducted by P. Bernard and a French archeological expedition, dug up six rectangular bronze coins issued by the Indo-Greek ruler Agathocles (180?-?165 BCE).

![Retour au fascicule]() Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan). [II. Les monnaies indo-grecques.]

Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan). [II. Les monnaies indo-grecques.]

[article]

II. Les monnaies indo-grecques.

![]() Cakra, vajra.

Cakra, vajra.

![]() Bowman shown on Bhaja cave verandah is an Indus Script hypertext to sigify a mint.,kāmaḍum=a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo bowman; an archer(Skt.)rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

Bowman shown on Bhaja cave verandah is an Indus Script hypertext to sigify a mint.,kāmaḍum=a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo bowman; an archer(Skt.)rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

%A3%E1%B9%87u_and_%C5%9Aiva_Images_in_India_Numismatic_and_Sculptural_Evidence

This monograph demonstrates using thousands of punch-marked and early coins of Ancient Bharata that the Harappa Script tradition of data archiving metalwork catalogues continues into the historical periods. Hence, all the symbols used on ancient coins of Bharata are Harappa Script hieroglyphs read rebus in Meluhha to signify metalwork.

Source: http://vidyaonline.org/dl/cultddk.pdf

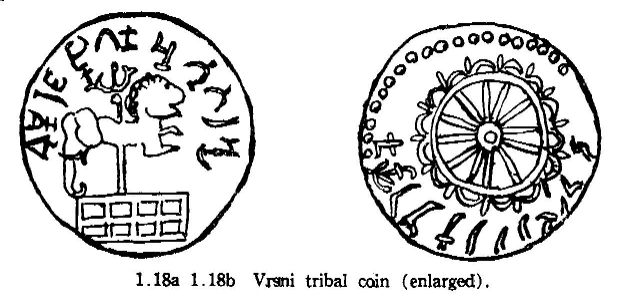

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/10/vrishni-janapada-coin-with-hieroglyphs.htmlवृष्णि is a term in Rigveda. A Vrishni silver coin from Alexander Cunningham's Coins of Ancient India: From the Earliest Times Down to the Seventh Century (1891) (loc.cit., Lahiri, Bela (1974). Indigenous States of Northern India (Circa 200 B.C.E to 320 C.E.), Calcutta: University of Calcutta, pp.242 3). वृष्णि [p=

1013,2] वृष्ण्/इ or व्/ऋष्णि, mfn. manly , strong , powerful , mighty RV.m. a ram VS. TS. S3Br.m. a bull L.m. a ray of light L.m. N. of शिव MBh.m. of विष्णु-कृष्ण L.m.of इन्द्र L.m. of अग्नि L.m. pl. N. of a tribe or family (from which कृष्ण is descended , = यादव or माधव ; often mentioned together with the अन्धकs) MBh. Hariv. &cn. N. of a सामन् A1rshBr. (Monier-Williams) An identical ancient silver coin (perhaps produced from the same ancient mint) of Vrishni janapada ca. 10 CE with kharoṣṭhī, Brahmi inscriptions and Harappa Script hieroglyphs was sold in an auction in Ahmedabad (August 2016) for Rs. 27 lakhs. In fact, the treasure is priceless and defines the heritage of Bhāratam Janam, 'metalcaster folk' dating back to the 7th millennium of Vedic culture. It signifies a spoked wheel which is the centre-piece of Bharat's national flag. सांगड sāṅgaḍa 'joined animal', rebus: sangaDa ‘lathe’ sanghaṭṭana ‘bracelet’ rebus 1: .sanghāṭa ‘raft’ sAngaDa ‘catamaran, double-canoe’rebusčaṇṇāḍam (Tu. ജംഗാല, Port. Jangada). Ferryboat, junction of 2 boats, also rafts. 2 jangaḍia 'military guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' ചങ്ങാതം čaṇṇāδam (Tdbh.; സംഘാതം) 1. Convoy, guard; responsible Nāyar guide through foreign territories. rebus 3: जाकड़ ja:kaṛ जांगड़ jāngāḍ‘entrustment note’ जखडणें tying up (as a beast to a stake) rebus 4: sanghāṭa ‘accumulation, collection’ rebus 5. sangaDa ‘portable furnace, brazier’ rebus 6: sanghAta ‘adamantine glue‘ rebus 7: sangara ‘fortification’ rebus 8: sangara ‘proclamation’ 9: samgraha, samgaha 'arranger, manager'.

On the VRSNi coin, tiger and elephant are joined to create a composite hyperext. This is Harappa Script orthographic cipher.

Hieroglyph: ढाल (p. 204) ḍhāla f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain: also a flag flying on forts &c. v दे. ढाल्या (p. 204) ḍhālyā a ढाल That bears the ढाल or grand flag of an army.

Rebus/Hieroglyph: ढाल (p. 204) ḍhāla f (S through H) A shield. ढालपट्टा (p. 204) ḍhālapaṭṭā m (Shield and sword.) A soldier's accoutrements comprehensively. ढाल्या (p. 204) ḍhālyā a ढाल Armed with a Shield.ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā -- .1. Tir. (Leech) "dàl"ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B. ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f.Addenda: ḍhāla -- . 2. *ḍhāllā -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. -- a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f.(CDIAL 5583) தளவாய் taḷa-vāy, n. prob. தளம்³ + வாய். [T. daḷavāyi, K. dalavāy.] Military commander, minister of war; படைத்தலைவன். ஒன்ன லரைவென்று வருகின்ற தளவாய் (திருவேங். சத. 89).

Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati) ढाळ (p. 204) Cast, mould, form (as of metal vessels, trinkets &c.)

This Indus Script cipher signifies that an ox-hide ingot of Ancient Near East was called ḍhāla 'a large metal ingot' -- a parole (speech) word from Indian sprachbund (language union or speech linguistic area) of the Bronze Age.

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'blacksmith' kolhe 'smelter'

The pellet border is composed of: goṭā 'seed', round pebble, stone' rebus: goṭā ''laterite, ferrite ore''gold braid' खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down). The railing for the pillar is Vedi, sacred fire-altar for Soma samsthā Yāga. There is evidence dated to ca. 2500 BCE for the performance of such a yajna in Binjor (4MSR) on the banks of Vedic River Sarasvati. The fire-altar yielded an octagonal pillar, which is detailed in ancient Vedic texts as a proclamation of Soma samsthā Yāga.

![]() Three hour-glass shaped vajra-s are shown in a cartouche below the yupa on the coin. Normally Vajrapani is shown such a vajra which has octagonal edges. kolom'three' rebus: kolimi, kole.l 'smithy, forge' kole.l 'temple'

Three hour-glass shaped vajra-s are shown in a cartouche below the yupa on the coin. Normally Vajrapani is shown such a vajra which has octagonal edges. kolom'three' rebus: kolimi, kole.l 'smithy, forge' kole.l 'temple'

It is a record of the performance of a Soma samsthā Yāga. It is Vrishni Janapada coin of ca. 10 CE.Cakra, pavi in Vedic tradition is also

a vajra. Rudra is vajrabāhu 'vajra weapon wielder'; said also of Agni and Indra.

वज्र [p=913,1] mn. " the hard or mighty one " , a thunderbolt (esp. that of इन्द्र , said to have been formed out of the bones of the ऋषि दधीच or दधीचि [q.v.] , and shaped like a circular discus , or in later times regarded as having the form of two transverse bolts crossing each other thus x ; sometimes also applied to similar weapons used by various gods or superhuman beings , or to any mythical weapon destructive of spells or charms , also to मन्यु , " wrath "RV. or [with अपाम्] to a jet of water AV. &c ; also applied to a thunderbolt in general or to the lightning evolved from the centrifugal energy of the circular thunderbolt of इन्द्र when launched at a foe ; in Northern Buddhist countries it is shaped like a dumb-bell and called Dorje ; » MWB. 201 ; 322 &c ) RV. &c; a diamond (thought to be as hard as the thunderbolt or of the same substance with it) , Shad2vBr. Mn. MBh. &c; m. a kind of column or pillar VarBr2S.; m. a kind of hard mortar or cement (कल्क) VarBr2S. (cf. -लेप); n. a kind of hard iron or steel L. On some sculptural friezes, three tigers or three elephants carry the wheel hypertext to signify iron working in smithy/forge: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS karabha, ibha 'elephant' rebus:karba, ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant' PLUS kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'.

Art historian and scholar of Bauddham studies, Huntington has identified the following characteristic, common features on the hypertext signified on these coins. I suggest that conclusions indicated by Huntington need to be revised in the context of life-activities of the artisans related to mint-metalwork signified on sculptural hypertexts and Punch-marked coin hypertexts.

Magadha janapada, Silver karshapana, c. 4th century BCE

Weight: 3.45 gm., Dim: 25 x 23 mm.

Five punches: sun, 6-arm, and three others / Banker's mark

Ref: GH 48.

karibha 'elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron' eraka 'knave of wheel' rebus: erako 'moltencast, copper'; arA 'spokes, rebus: Ara 'brass' khaNDa 'division'

rebus: kaNDa 'implements' arka 'sun' rebus: arka, eraka 'copper'. Six-spoked hypertext emanating from

dotted circle is: dhAu 'element, mineral ferrite' PLUS muhA 'furnace quantity, ingot' PLUS kANDa 'arrow'

rebus: kaNDa 'implements;. Thus, the five PMC hypertexts signify mintwork with iron, molten cast copper,

iron implements, ingots, furnace work.

On some sculptural friezes, the 'fish-fin' hypertext is ligatured to the tip of the spokes of the wheel emanating

from the dotted circle. This signifies: ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'metal' aya 'iron'.

PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage'.

![]()

![]() Bhaja Chaitya ca. 100 BCE. Hieroglyphs are: fish-fin pair; pine-cone; yupa: kandə ʻpine' rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements, fire-altar' khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' (Lahnda CDIAL 13640) Ta. kampaṭṭam, kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. Yupa: Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). Rebus: kāṇḍa,'implements'.

Bhaja Chaitya ca. 100 BCE. Hieroglyphs are: fish-fin pair; pine-cone; yupa: kandə ʻpine' rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements, fire-altar' khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' (Lahnda CDIAL 13640) Ta. kampaṭṭam, kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. Yupa: Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). Rebus: kāṇḍa,'implements'.

Ligature to 'mintwork' signifier is also shown on the wheel sculptural friezes of Amaravati -- spokes are ligatured on their tips with 'fish-fins' joined together:ayo kammaTa 'iron mintwork' ayo 'fish' PLUS khambhaṛā 'fish-fin'.;

![]() Amaravati sculpturel friezes: cakra with ligatures.

Amaravati sculpturel friezes: cakra with ligatures.![]() Elaborate orthography on sanchi stupa relates the spoked wheel to 'fish-fin' hypertext (mintwork) and also to tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'.

Elaborate orthography on sanchi stupa relates the spoked wheel to 'fish-fin' hypertext (mintwork) and also to tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'.

1. dotted circle

2. arrow (three)

3. twist (three) Some examples replace the 'twist' with 'buns-shaped ingots'. Thus, total six hypertexts emanate from dotted circle as spokes.

Four components of hypertext are read rebus in Meluhha:

1. Dotted circle is a Harappa Script hieroglyph and signifies a 'strand' of rope. dhāī˜ 'strand' rebus: dhāu'soft red stone, element'(ferrite ore)

Thus, together, the hypertext of dotted circle linked to six spokes as the चषालः caṣāla or cakra signifies a weapon with multiple prongs orthographed by sculptors and mintworkers who punched symbols on punch-marked coins. The arrows and twists thus signify: implements and furnaced ingots of dhatu'(ferrite) minerals'.

![]() Santali glosses

Santali glosses

Hieroglyph: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773).

Rebus: Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ(CDIAL 6773)

![]() British Museum. 2nd cent. Hoshiarpur, Punjab.

British Museum. 2nd cent. Hoshiarpur, Punjab.![]()

Republic of the Vrishni Peoples (10-40AD), Silver Drachm, MIGIS Type 928 variation, 2.15g. Obv: Standard, topped by a Nandipada finial and an elephant's head and forepart of a leaping lion below it, in an ornamental railing; Brahmi legend (Vŗ)shņi Rajaña Ganasya Tratarasya (वृ)ष्णी राजञ गणस्य त्रतरस्य reading anticlockwise outwards below. Rev: Ornate 14-spoked wheel with scalloped outer rim; Kharoshthi legend from 3 o'clock to 9 o'clock "The Vrishnis were known to Panini and to Kautilya; the latter describes them as a Sangha. In the Mahabharata they are counted amongst the Vratya brotherhood of Kshatriyas. As one of the Yadava clans they are closely associated with Krishna in myth and lore. It is said that they migrated to Dwaraka from Mathura, after Krishna's capital was besieged by the demon Kalayavana. The reference to 'Yavana' here and the subsequent migration from Mathura may have had some historical basis" The coins of the Vrishnis are by far the rarest of the so-called 'Tribal' coins of India. Only one silver specimen, from the Alexander Cunningham collection, is known to exist in the British Museum and has been published by Mitchiner as Type 928 in MIGIS. http://classicalnumismaticgallery.com/advancesearch.aspx ![]()

The ring-stones of Al Khanoum palace are comparable to the ring-stones of Dholavira

![Image result for dholavira ringstones]() Ringstones, Dholavira.

Ringstones, Dholavira.

Hala gets repeated as Indus Script hypertext on cast coins. On the coin on the right, three hieroglyphs are signified, one below the other: snake, pupil of the eye; plough

![]() Hala shape also occurs on punch-marked coins, together with sun hieroglyph.

Hala shape also occurs on punch-marked coins, together with sun hieroglyph.

![]()

![]()

The hala shown on this coin also appears on Vasudeva coin. See the hieroglyph on the Vasudeva coin (right bottom)

Mirror: https://www.academia.edu/25807197/Emergence_of_Vi%E1%B9%A3%E1%B9%87u_and_%C5%9Aiva_Images_in_India_Numismatic_and_Sculptural_Evidence

![]()

![]() Source: https://www.academia.edu/25807197/Emergence_of_Viṣṇu_and_Śiva_Images_in_India_Numismatic_and_Sculptural_Evidence

Source: https://www.academia.edu/25807197/Emergence_of_Viṣṇu_and_Śiva_Images_in_India_Numismatic_and_Sculptural_Evidence

![]() Krishna कृष्ण-वासुदेव as warrior and king. Earliest extant image on coin, from the borderlands, northwest India. Krishna (कृष्ण-वासुदेव) in Bactrian garb on silver coin of Vaishnava King Agathocles (~180 BCE). With शङ्ख, चक्र, छत्र.

Krishna कृष्ण-वासुदेव as warrior and king. Earliest extant image on coin, from the borderlands, northwest India. Krishna (कृष्ण-वासुदेव) in Bactrian garb on silver coin of Vaishnava King Agathocles (~180 BCE). With शङ्ख, चक्र, छत्र.![]() Balarāma in the bronze coin of Emperor Moasa (Maues) with the characteristic हल and मुसल. Takshashila, Northwest India, ~70 BCE.

Balarāma in the bronze coin of Emperor Moasa (Maues) with the characteristic हल and मुसल. Takshashila, Northwest India, ~70 BCE.![]() The earliest known representation of Balarāma (बलराम), elder brother of Krishna. Silver coin of Agathocles (~180 BCE). Notice हल, मुसल, छत्र

The earliest known representation of Balarāma (बलराम), elder brother of Krishna. Silver coin of Agathocles (~180 BCE). Notice हल, मुसल, छत्र

Pāṇini, 5th century BCE, says images used in shrines. Mahābhāṣya, 2nd Century BCE, mentions temples to Rāma, Kṛṣṇa, Śiva, and Viṣṇu.![]()

![Indus Seals (2600-1900 Bce) Beyond Geometry: A New Approach to Break an Old Code by [Talpur, Parveen]](http://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61kqE6XlJZL.jpg)

Target Online publication November 2017 ISBN 9781108160186

Target Online publication November 2017 ISBN 9781108160186

'ra'

'ra'

'na' (Brāhmī syllabic symbols)

'na' (Brāhmī syllabic symbols)

Plough shown on Sumerian cylinder seals.

Plough shown on Sumerian cylinder seals. Isidore, the farm labourer's plough

Isidore, the farm labourer's plough

Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan). [II. Les monnaies indo-grecques.]

Trésor de monnaies indiennes et indo-grecques d'Aï Khanoum (Afghanistan). [II. Les monnaies indo-grecques.]

Location of Rasal Jinz in Oman, Persian Gulf

Location of Rasal Jinz in Oman, Persian Gulf

Pot with zebu, bos indicus tied to a post. Indus Script hieroglyph.

Pot with zebu, bos indicus tied to a post. Indus Script hieroglyph.

On this coin of Agathocles, Zeus is seen wielding vajra, 'thunderbolt' weapon of Rudra and Indra in Veda tradition.

On this coin of Agathocles, Zeus is seen wielding vajra, 'thunderbolt' weapon of Rudra and Indra in Veda tradition.

Bactria: Agathocles, AE dichalkon, c. 185-170 BCE

Bactria: Agathocles, AE dichalkon, c. 185-170 BCE._Circa_220-185_BC.jpg/600px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_220-185_BC.jpg)

lōhakāri

lōhakāri

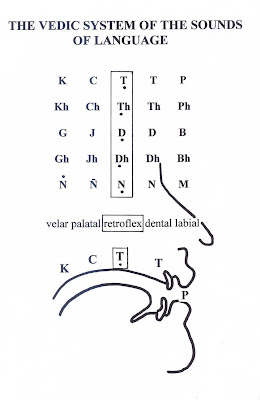

Courtesy: Frits Staal's lecture. See: Scripts of India.

Courtesy: Frits Staal's lecture. See: Scripts of India.

AE tetradrachm or unit, c. first quarter of 2nd. Century

AE tetradrachm or unit, c. first quarter of 2nd. Century

Amaravati sculptural frieze. For

Amaravati sculptural frieze. For

Oesho or Śiva with bull

Oesho or Śiva with bull

Various swords. Ancient India. https://www.pinterest.se/pin/7881368078200571/

Various swords. Ancient India. https://www.pinterest.se/pin/7881368078200571/

Chanhudaro seal 23 See decipherment at

Chanhudaro seal 23 See decipherment at

Zinc smelters. Zawar mines.

Zinc smelters. Zawar mines.

Gela shipwreck finds.

Gela shipwreck finds.

is paramātman.

is paramātman.

Tympanum of Dong Son Bronze drum made using cire perdue technique of metal casting.

Tympanum of Dong Son Bronze drum made using cire perdue technique of metal casting.

Location of Bharatpur bird sanctuary mentioned by Jayasree Saranathan.

Location of Bharatpur bird sanctuary mentioned by Jayasree Saranathan.

TOP COMMENT

ð ð Great work by Government..... Pidi-tards (Congis), Aaptards, Commis and Libtards have buried Indian historical sites over the past 7 decades !Saimenon