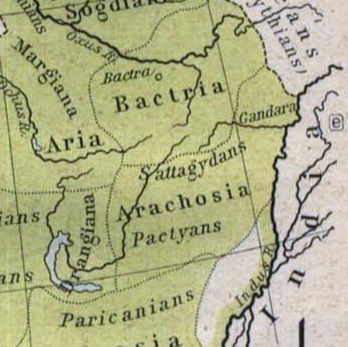

BRONZE AGE, in Iranian archeology a term used informally for the period from the rise of trading towns in Iran, ca. 3400-3300 B.C., to the beginning of the Iron Age, ca. 1400-1300 B.C. It was originally adopted as part of a chronological system based on assumptions about successive changes in the use of raw materials for tool manufacture, but, along with Iron Age and other comparable terms, it has long since lost any precise meaning in relation to technology. More commonly today, however, it simply refers to archeological sites and events regarded as occurring after the Neolithic (more precisely, after the Chalcolithic) era and before the Iron Age, and this sense is the one that has been adopted here. Archeological knowledge of Bronze Age Iran has been derived primarily from intensive regional studies in which systematic surface surveys have been combined with excavation at sites having long, well-defined stratigraphic sequences and with more limited excavations designed to obtain information on specific periods (Figure 29; for an outline of the results of these excavations, a detailed chronology, a discussion of chronological problems, and a full set of references, see Voigt and Dyson). During the Bronze Age the populations of the Iranian plateau, bounded on the east by the Hindu Kush and the Himalayas and on the west by the lowlands of Ḵūzestān and Mesopotamia, prospered greatly, owing to rich natural resources and the overland trade routes between the western lowlands and the Indus valley, central Asia, and Afghanistan. There is evidence that at the end of the 4th millennium B.C. settlements throughout Iran were linked in a common cultural network, the “Proto-Elamite horizon.” Subsequently, however, distinct regional cultural and political systems and a major division between eastern and western Iran developed. As these regions exhibited strong cultural continuity throughout the Bronze Age, cultural development in each will be traced from the Proto-Elamite period.

Southwestern Iran. Modern archeological research on Iran began in the lowlands of Ḵūzestān, known in antiquity as Elam. This region passed from the prehistoric into the protohistoric period in the mid-4th millennium B.C. The most important site in the region is Susa, where in 1897 a French mission began work that continued intermittently until 1977. In the early years large settlement areas were excavated; more recently the focus has been on detailed stratigraphic analysis (see Carter and Stolper). The results of intensive surface surveys on the surrounding Susiana plain have been summarized for this period by J. Alden (1987) and R. Schacht (cf. Wright, for the adjacent Deh Luran [Dehlorān] plain).

At Susa a great many texts in Proto-Elamite script (including both pictograms and numerical symbols) have been found on small clay tablets dated to the end of the 4th millennium (Meriggi, 1971). This script was superseded by cuneiform writing borrowed from Sumer in about 2300 (Carter and Stolper). The pottery of the earliest Proto-Elamite level (Susa III) is quite different from that of the underlying (Susa II) deposits, which are contemporary with the Late Uruk period in Mesopotamia (ca. 3500-3100 B.C.); in contrast, the Susa III pottery has parallels with that of the Jemdet Nasr (Jamdat Naṣr) and Early Dynastic I period in Mesopotamia (ca. 3100-2800 B.C.). Proto-Elamite Susa is estimated to have had a total area of about 11 ha, but the excavated architecture provides little information on community organization. Elsewhere on the Susiana plain there were only small, scattered settlements.

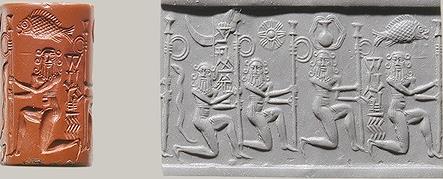

The influence of Susa, revealed through the presence of Proto-Elamite tablets, cylinder seals, products bearing seal impressions, and selected pottery types, extended far to the east and north, where trade in raw materials and manufactured goods among a series of cities and towns was well established by 3100 B.C. The geographic range of this Pro-Elamite network encompassed the plateau as far east as Shahr-i Sokhta (Šahr-e Sūḵta) in Sīstān and Tepe Hissar (Ḥeṣār) on the Damghan (Dāmḡān) plain in the north. The archeological evidence from Proto-Elamite sites differs, and the exact nature of the economic and political ties among them therefore remains problematic. Nevertheless, such settlements as those of Susa III, the Banesh (Baneš) period at Tal-e Malyan (Tall-e Malīān), Sialk (Sīalk) IV:2, Tepe Yahya (Yaḥyā) IVC, and Shahr-i Sokhta I/II produced Proto-Elamite texts and glyptic finds that suggest both shared ideology and economic ties (Carter and Stolper; Alden, 1982; Amiet, Dyson, 1987; Finkbeiner and Rollig; Lamberg-Karlovsky, 1977; idem and Tosi; Weiss and Young).

To the east of Ḵūzestān the prehistoric period is well documented in the Kor river basin of Fārs province. The major excavated Bronze Age sites in this region are Malyan (Sumner) and Darvazeh (Darvāza) Tepe (Jacobs). Surface surveys conducted by Louis Vanden Berghe, William Sumner, and others have shown significant changes in settlement patterns and economic life during this period (Sumner, with references). In the Banesh (Proto-Elamite period) there was a smaller settled population in this region than in previous times, probably as a result of a broad shift from sedentary farming to pastoral nomadism. Malyan itself was a city, with a built-up area of about 50 ha. (In the Late Banesh period this area and about 150 ha of open space were enclosed by a wall.) Excavation has produced evidence of craft specialization, for example, production of small personal ornaments from imported raw materials. A large number of Proto-Elamite tablets, cylinder seals and sealings, and ceramics from Banesh Malyan are directly related to those in Susa III, evidence of strong contact between the two regions. There is, however, no evidence of political domination by Susa, and Sumner has suggested that Malyan was “the seat of a local tribal khan who exercised some form of political authority over the settled population and the pastoral nomads [of Fārs]” (p. 317). During the later 3rd millennium, when Susa and the lowlands were under the domination of Mesopotamian rulers, Ḵūzestān and Fārs showed greater cultural divergence. In Fārs after the Banesh phase there was a “severe depopulation” of the Kor river basin, lasting approximately from 2600 to 2200 B.C. There is no evidence for agricultural settlement, but the area is assumed to have been used by pastoral nomads.

Settlement data from the succeeding Kaftari phase (2200-1600 B.C.) in the Kor river basin suggest a state organization centered on the walled city of Anshan (Tal-i Malyan) and the reestablishment of ties with the lowlands. The rulers of Fārs also played a role in political developments in Mesopotamia: Both the Akkadian king Maništusu (2269-2255 B.C.) and Gudea of Lagash (2143-2124 B.C.) claimed to have defeated Anshan, and subsequently the city became part of the Elamite political sphere (Carter and Stolper, pp. 13-16; Sumner, pp. 316-18). Little is known about Fārs from 1600 to 1300 B.C.; the population again declined, and the remaining settlements were divided into two geographically distinct cultural groups, named Qale (Qaḷʿa) and Shoga Teimuran (Šoga Teymūrān) by William Sumner (Sumner; Jacobs).

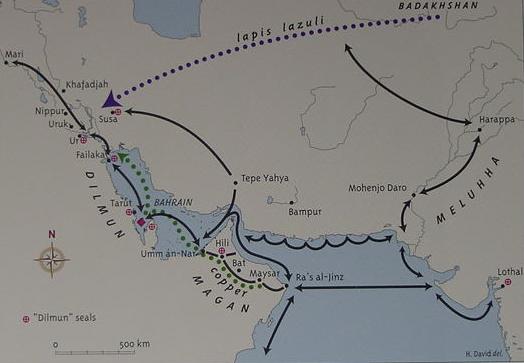

The southeastern plateau. Excavations at Tepe Yahya in Kermān province have uncovered occupation levels dating from the end of the 4th and the 3rd millennium (Lamberg-Karlovsky, 1970, 1977; Potts, 1980); intensive surface surveys have yielded further data (Prickett). In the Proto-Elamite period (IVC) Yahya was a large village or a small town in a sparsely populated region. Excavation has revealed a large building with a number of rooms that contained artifacts associated with economic administration: inscribed Proto-Elamite and blank tablets, seals and sealings, and pottery vessels apparently imported from Elam. This structure has been interpreted as an enclave for foreigners, because contemporary domestic structures on the mound contained artifacts and ceramics typifying a continuous indigenous cultural tradition. During the middle and late 3rd millennium (IVB) Yahya specialized in production of vessels and other small objects from chlorite, a soft stone that is abundant locally (Kohl). These items were exported to Mesopotamia, probably by way of Susa, and to settlements along the Persian Gulf, which conducted a flourishing sea trade extending as far as the Indus valley.

North of Yahya, on a deltaic fan at the western edge of Dašt-e Lūt, Shahdad (Šāhdād, historic Ḵabīṣ) has been explored by means of excavations in a cemetery and a surface survey of the settlement (Hakimi; Salvatore and Vidale). The site was apparently occupied during the Proto-Elamite period, though the evidence has not yet been fully reported. In the second half of the 3rd millennium it was an active production center for artifacts of copper and semiprecious stones like agate, carnelian, and chalcedony. A large cemetery of pit graves yielded metal tools, vessels, and ornaments. Quantities of ceramics bear incised and stamped signs related to the older Proto-Elamite script. Similar pottery with some of the same signs was found in Yahya IVB and A (Potts, 1981). Several cylinder seals from Shahdad, apparently depicting a vegetation goddess, are also paralleled in contemporary levels at Yahya. Unique modeled clay busts of men and women have been compared with the stone sculptures of Early Dynastic II in Mesopotamia (ca. 2700-2600 B.C.). Two types of artifact from the cemetery, compartmented copper stamp seals and miniature columns of limestone, are common at sites of the same period in eastern Iran and central Asia and provide evidence of long distance trade on the eastern plateau. No doubt Shahdad served as a point of departure for the dangerous journey across Dašt-e Lūt to northeastern and eastern Iran.

The farthest eastern extension of the Proto-Elamite network has been documented by a single tablet, seals, and sealings from period I at Shahr-i Sokhta. This site on the Helmand delta, which has been explored by means of surface surveys and extensive excavations of both the settlement and cemetery areas, was founded around 3200 B.C. (Tosi, 1983). By the mid-3rd millennium (periods II-III) it had grown into a major urban center covering 80 ha, surrounded by rural villages each with a surface area of between 0.5 and 2 ha. At the height of its development Shahr-i Sokhta was divided into functional zones, with an area devoted to public and administrative buildings, residential quarters, and a cemetery covering 21 ha. Productive activities were initially scattered but were later concentrated in what may have been a craftsmen’s quarter. Crafts documented at the site include the working of lapis lazuli, turquoise, chalcedony, quartz, and flint, as well as of copper. Pottery was manufactured at a small specialized kiln site (Rūd-e Bīābān) located about 30 km away; the styles of painted pottery were shared with central Asia and Baluchistan. During the mid-3rd millennium Shahr-i Sokhta was apparently the largest settlement on the eastern Iranian plateau. Whether or not a state organization had been achieved remains a matter for speculation. Nevertheless, given the size of the settlement and the complexity of its spatial organization, the presence of a state apparatus in periods II-III seems likely.

The central and northern plateau. The influence of Proto-Elamite Susa can also be seen in the mountains of central western Iran and along the northern east-west overland route via Sialk (near Kashan/Kāšān) to Tepe Hissar. In the central Zagros the best known Bronze Age sequence comes from excavations at Godin (Gowdīn) Tepe in the Kangāvar valley (Young and Levine). In the last quarter of the 4th millennium an enclave of lowland traders (or indigenous administrators with strong ties to the lowlands) had been established there (periods VI-V; see Weiss and Young). A complex of buildings in an open court was surrounded by an oval wall. Within the enclosure such exotic items as tablets (all numerical except for one example inscribed with a single non-numerical character), seals and sealings, and types of ceramic vessels identified with the lowlands were found, as were objects of local manufacture. The latter included pottery typical of preceding occupation levels (period VI) and of contemporary settlements on the surrounding plain and in adjacent valley systems as far north as Bījār and south into Luristan. The oval enclosure at Godin was apparently abandoned in some haste, for numerous pots and other objects were left on the floors of the buildings. Following a brief (?) hiatus the settlement was reoccupied around 2700 B.C. by people with a very different material culture (Godin IV, “Yanik period”; see “Northwestern Iran” below), including dark, burnished pottery with incised and white-filled decoration. These people had apparently migrated to the Kangāvar area (and to the Qazvīn and Malāyer plains) from northwestern Iran and ultimately from across the Caucasus (Burney and Lang, p. 59).

The later Bronze Age is well documented for the Kangāvar region, owing to excavations over a large area at Godin (III: 6-2) and to extensive surface surveying (Henrickson, 1987, with references). Surrounding valleys, including the Māhī Dašt, or Kermānšāh plain, are known only from surface surveys and limited soundings (Henrickson, 1987; Schacht). For Luristan survey data are supplemented by excavations at a series of cemeteries in the Pusht-i Kuh (Pošt-e Kūh; Vanden Berghe); these burial grounds are not associated with settlements and may indicate the presence of nomadic pastoralists in the area. Historical sources from Susa and Mesopotamia attest that in the middle and late 3rd millennium the Zagros valleys were occupied by ethnic groups called Guti and Lulubi and were under the control of the Elamite dynasties of Awan and Shimashki (Carter and Stolper, pp. 10-23; Gadd, pp. 429ff.; Schacht). The archeological evidence (see Henrickson, 1987) indicates that at the beginning of this period, during the occupation of Godin III:6, large parts of the central Zagros shared a distinctive ceramic tradition, with more distant links to Ḵūzestān (Susa IV) and Fārs (Late Banesh). This pattern is generally interpreted as an indication of shared contact and economic (rather than political) ties. When Susa came under the control of the Akkadian dynasty, diverging ceramic styles within the mountains reflect isolation from the lowlands. This isolation appears to have persisted after Susa became part of the Ur III state, though both peaceful and military contacts have been documented in texts. Finally, in the early 2nd millennium settlements like the town designated Godin III:2 were linked in a broad cultural zone, attested by elements of a ceramic style that extended throughout central western Iran. This common style may reflect a degree of economic and political unity as well: It has been suggested that the central Zagros was the location of the kingdom of Shimashki, contemporary with the Sukkalmah dynasty at Susa (Henrickson, 1984). Farther east the Proto-Elamite occupation of Sialk IV:1-2 was contemporary with Godin VI/V, though it lasted into a slightly later period. Like Shahdad, Sialk is located on a deltaic fan at the edge of the central desert. Limited excavations in the ruins of several small mud-brick structures produced diagnostic artifact types (tablets, glyptic, and ceramics) that clearly demonstrate contact with Godin and Susa (Dyson, 1987). As at Godin, however, other elements of material culture show a continuing local cultural tradition. The importance of Sialk within the Proto-Elamite network may have been owing to its proximity to a major source of copper at Anārak; the geographical location of Sialk was equally critical, for it lay on the route from Susa to the north via Fārs (Amiet). Shortly after the beginning of the 3rd millennium Sialk was abandoned; it was not resettled until the Iron Age, late in the 2nd millennium.

Still farther east, along the northern edge of the desert on the northern east-west route, often called the “high road,” is Tepe Hissar (Schmidt; Dyson and Howard), near Damghan. It is also located on a rich deltaic fan, and its population was able to draw on the natural resources of both mountains and plain. In about 3000 B.C. a Bronze Age town (Hissar Middle and Late II) evolved from the earlier settlement (Hissar I-Early II). It consisted of small houses of mud brick separated by open spaces and unpaved walks. About a third of the town was given over to craft production, especially smelting of copper and production of copper objects and working of large quantities of lapis lazuli, a raw material imported from the area that is now northern Afghanistan. Unoccupied parts of the mounds were used for burials. A major innovation characterized this period of town life: the introduction of reduction kilns for the mass production of burnished gray pottery imitating metal vessel forms. Soon this gray ware had almost entirely replaced painted pottery. Although copper technology was already known in Hissar I, more extensive smelting of copper ores led to an increase in the number and types of metal objects produced in Hissar II. The importation of lapis lazuli and turquoise demonstrates links with the east, but at the same time blank clay tablets of the size and shape characteristic of Proto-Elamite tablets, clay tokens (cones, balls, and other forms), and a single cylinder seal show continuing contact with the west. The large number of burials at Hissar from the middle of the 3rd millennium is evidence of considerable wealth within the community. Although the town was somewhat reduced in area, it contained a special, well-built structure filled with rich materials: copper, gold, and silver vessels and weapons. This building housed a small fire altar in one corner of the main room and may have been a shrine. A compartmented bronze stamp seal with a stepped-square design links it to Altyn Tepe, a contemporary urban center in southern Turkmenia. The building at Hissar was destroyed by fire, clearly as the result of violent attack: Remains of a number of bodies were found sprawled on the floor, and the surrounding debris was filled with stone arrowheads. Little is known about the town at Hissar during the remainder of the Bronze Age. In the last phase of its occupation (III) yellow alabaster or calcite objects increased in quantity. Among them were miniature columns with grooved ends, which have now also been found at Tureng (Tūrang) Tepe in Gorgān, in southern Turkmenia, in Bactria, in Sīstān, and at Shahdad. The contexts of these finds can be interpreted as religious, suggesting that some kind of cult practice linked all of eastern Iran at the end of the 3rd millennium.

North of Hissar, across the Alborz (Elburz) range at the southeast corner of the Caspian plain, lay the town of Tureng Tepe (Deshayes, 1977, with references). Like Hissar it had been founded much earlier and remained occupied into the 2nd millennium B.C. Although the pottery and artifacts of Tureng and Hissar II differ somewhat in style, there are many similarities, and both centers participated in the lapis lazuli trade. The outstanding feature of Bronze Age Tureng was a major terraced mud-brick structure built around 2000 B.C. It was 80 m long and rose 13.50 m into the air, in two stages. It was thus comparable in scale to the contemporary Ur-Nammu ziggurat at Ur. Miniature columns of Hissar type were found on the upper story of this building, together with pottery of the Tureng IIIC1 period. Comparable brick structures have been identified at Altyn Tepe (the High Terrace, 12 m high) and at Mundigak (Mondīgak) in Afghanistan (the Monument Massif of period V). Deshayes concluded that toward the end of the 3rd millennium central Asia and eastern Iran were part of a cultural community that was influenced by Mesopotamia. These terraced structures were certainly cult centers of the type mentioned in the legend “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta” (Jacobsen, 1987, pp. 275-319).

Northwestern Iran. Throughout the Bronze Age northwestern Iran, or Azerbaijan, constituted a separate cultural zone, more closely related to adjacent regions to the north and west than to the Iranian plateau. Although geographically a unit, this region often comprised two separate cultural provinces, northern and southern Azerbaijan, divided by Lake Urmia. For the Bronze Age the key site for northern Azerbaijan is Haftavan (Haftavān) Tepe (Burney, 1976; Edwards); important supplementary data have resulted from earlier excavations at Geoy (Gūy/Gök) Tepe (Burton-Brown, 1951), nearby Gijlar (Gejlār) Tepe (Pecorella and Salvini, 1987), and Yanik Tepe (Burney, 1961, 1962). Late in the 4th millennium people with a distinctive material culture including round houses and burnished dark pottery migrated into the area, apparently from the north; closely related material (the Early Transcaucasian, or Kur-Araxes, assemblage) has also been found in eastern Anatolia (Sagona, 1984). In Iranian Azerbaijan the earliest excavated settlement yielding this kind of material is at Geoy Tepe (K:1), cleared only in a deep sounding. Settlements dated to the 3rd millennium are better documented, for example, the Early Bronze Age I and II occupations at Yanik, Gijlar, and Geoy K:2-3 (Burney and Lang, pp. 59-66). In the 2nd millennium these sites were characterized by a very different ceramic assemblage consisting of monochrome- and polychrome-painted buff wares. At the same time Haftavan (period VIB) was experiencing its greatest prosperity. The town was built on a series of terraces, and there is some evidence of functional differentiation of space (Burney, 1974, 1975). Although there are a few parallels with sites in the southern part of the Urmia basin, these northern sites are most closely related to settlements in the Trans-Caucasus and Anatolia, continuing the pattern established at the beginning of the Bronze Age.

To the south of Lake Urmia only the Ošnū and Soldūz valleys have been well documented archeologically (Dyson, 1983, with references). Following a period of abandonment that appears to have lasted through most of the 4th millennium and well into the 3rd, this region was reoccupied by agricultural groups living in sizable towns like Hasanlu (Ḥasanlū) VII. The distinctive pottery is only distantly related to that of northern Mesopotamia and the central Zagros. In the 2nd millennium the presence at sites like Dinkha (Denḵā) Tepe IV and Hasanlu VI of ceramics typical of the Khabur (Ḵābūr) region in ancient Mesopotamia (modern north Syria) reflects strong economic or political ties with the west, particularly the kingdom of Shamsi-Adad (Kramer, p. 105). Northern Mesopotamia and Syria are easily accessible from the Ošnū valley through the Kelešīn pass, and these Iranian sites may have participated in the tin trade, which was dominated by Assyria in the early 2nd millennium. Massive mud-brick walls at Dinkha suggest an urban settlement, but the architecture and settlement layout of this period are not well known because of limited excavations.

The end of the Bronze Age. In the late 1960s, in the absence of regional surveys, careful excavations, and analytical studies of resources, technology and subsistence, the apparent abrupt decline of urban centers in the east, from southern Turkmenia to the Indus valley, was attributed to violent invasion and mass migration. Current research suggests, however, that the decline of urban centers and long-distance trade was a more gradual process, beginning as early as 1850 B.C. and continuing for several centuries at varying rates in different regions (Tosi, 1986). Some areas remained unoccupied, for example, the vicinity of Tepe Sialk, whereas others, like the plain around Hissar, were now abandoned. Gorgān and southern Turkmenia remained inhabited but with greatly reduced populations. The area later known as the Bactrian plain, on the other hand, appears to have been resettled; there towns were replaced by scattered rural villages and administrative centers established along natural water courses or man-made canals (Biscione, 1977).

In the Helmand basin shifting hydrological conditions probably played a role in the abandonment of Shahr-i Sokhta and the immediately surrounding territory. The town appears to have been abandoned gradually, for in each succeeding occupation level more open space occurs until finally, in period IV, only one large building stood on the site. At the same time, however, about forty small nearby villages remained occupied, indicating a change in social and political organization, rather than a depopulation of the area (Tosi, 1980). Subsequently these villages also shifted, probably following the water supply. In southern Baluchistan there is also evidence of continuity of occupation (Jarrige, 1983). The introduction of new crops (rice and sorghum) and of double cropping were among major economic changes that took place late in the 2nd millennium B.C. (Costantini, 1981).

Reconstructions of the linguistic and historical geography of eastern Iran suggest that the area was occupied in the 3rd and 2nd millennia by proto-Indo-Aryan speakers (Burrow, 1973) and that Iranian-speaking groups began to move in between about 1400 B.C. and the early 1st millennium (Gnoli, 1980), three or four centuries after the beginning of the decline of the cities. It is relevant to this problem that horse bones and equestrian figurines have been found for the first time in late 2nd-millennium contexts in southern Baluchistan (Jarrige, 1983). Furthermore, sherds of Andronovo pottery, derived from southern Siberia and traditionally linked by scholars with Iranian tribes, appear for the first time in central Asia at the end of the Bronze Age (i.e., the end of the Namazga/Namāzgāh VI period), half a millennium after the onset of urban decline (Biscione, 1977; L’Asie centrale, 1988).

The transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in western Iran is still extremely difficult to trace and has recently been discussed by Young (1985) and Levine (1988).

Bibliography:

J. Alden, “Trade and Politics in Proto-Elamite Iran,” Current Anthropology 23, 1982, pp. 613-40.

Idem, “The Susa III Period,” in The Archaeology of Western Iran, ed. F. Hole, Washington, D.C., 1987, pp. 157-70.

P. Amiet, “Archaeological Discontinuity and Ethnic Duality in Elam,” Antiquity 53, 1979, pp. 195-204.

L’Asie centrale et ses rapports avec les civilisations orientales des origines à l’âge du fer, Actes du colloque franco-soviétique Paris, 1985, Mémoires de la mission archéologique française en Asie centrale I, Paris, 1988.

R. Biscione, “The Crisis of Central Asian Urbanism in the Second Millennium B.C. and Villages as an Alternate System,” in Le plateau iranien et l’Asie centrale des origins à la conquête islamique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Colloques Internationaux 567, Paris, 1977, pp. 113-28.

C. Burney, “Excavations at Yanik Tepe, North-West Iran,” Iraq 23, 1960, pp. 138-53.

Idem, “Excavations at Yanik Tepe, Azerbaijan, 1961,” Iraq 24, 1962, pp. 134-49.

Idem, “Excavations at Haftavan Tepe 1971.

Third Preliminary Report,” Iran 11, 1973, pp. 153-72.

Idem, “Excavations at Haftavan Tepe 1973. Fourth Preliminary Report,” Iran 13, 1975, pp. 149-54.

Idem, “The Fifth Season of Excavations at Haftavan Tappeh. Brief Summary of Principal Results,” in Proceedings of the IVth Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, 1975, ed. F. Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1976, pp. 257-71.

Idem and D. M. Lang, The Peoples of the Hills, New York, 1972.

T. Burrow, “The Proto-Indoaryans,” JRAS, 1973, pp. 123-40.

T. Burton-Brown, Excavations in Azarbajan, 1948, London, 1951.

E. Carter and M. W. Stolper, Elam. Surveys of Political History and Archaeology, University of California Publications, Near Eastern Studies 25, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984, pp. 103-313.

L. Costantini, “Paleoethnobotany at Pirak,” in South Asian Archaeology 1979, ed. H. Hartel, Berlin, 1981, pp. 271-78.

J. Deshayes, “Tureng Tepe et la période Hissar IIIC,” Ugaritica 6, 1969, pp. 40-163.

Idem, “A propos des terrasses hautes de la fin du IIe millénaire en Iran et en Asie centrale,” in Le plateau iranien et l’Asie centrale des origines à la conquête islamique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Colloques Interationaux 567, Paris, 1977, pp. 95-112.

R. H. Dyson, Jr., “Introduction. The Genesis of the Hasanlu Project,” in M. M. Voigt, Hajji Firuz Tepe, Iran. The Neolithic Settlement, Hasanlu Excavation Reports 1, University Museum Monograph 50, Philadelphia, 1983, pp. xxv-xxviii.

Idem, “The Relative and Absolute Chronology of Hissar II and the Proto-Elamite Horizon of Northern Iran,” in Chronologies de Proche Orient/Chronologies in the Near East. Relative Chronologies and Absolute Chronology 16,000-4,000 B.P. II, ed. O. Aurenche, J. Évin, and F. Hours, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 379, Oxford, 1987, pp. 647-78.

Idem and S. M. Howard, eds., “Reports of the Tappeh Hessar Restudy Project, 1976,” Mesopotamia (forthcoming).

M. R. Edwards, Haftavan, Period VI. Excavations in Azerbaijan (North-western Iran) I, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 192, Oxford, 1981.

U. Finkbeiner and W. Rollig, eds., Ğamda Nasr. Period or Regional Style?, Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients B62, Wiesbaden, 1986.

C. J. Gadd, “The Dynasty of Agade and the Gutian Invasion,” in CAH3 II, pp. 417-61.

G. Gnoli, Zoroaster’s Time and Homeland, Serie Orientale Roma 52, Rome, 1980.

R. Ghirshman, Fouilles de Sialk I, Musée du Louvre, Départment des antiquités orientales, Série Archéologique 4, Paris, 1938.

A. Hakimi, “Découverte d’une civilisation préhistorique à Shahdad au bord ouest du Lut, Kerman,” in Memorial Volume of the VIth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, Oxford, 1972, Tehran, 1978, pp. 131-50.

C. (Kramer) Hamlin, “The Early Second Millennium Ceramic Assemblage at Dinkha Tepe,” Iran 12, 1974, pp. 125-53.

H. Hartel, ed., South Asian Archaeology, 1979, Berlin, 1981.

R. C. Henrickson, “Simaski and Central Western Iran. The Archaeological Evidence,” ZA 74, 1984, pp. 98-122.

Idem, “Godin III and the Chronology of Central Western Iran circa 2600-1400 B.C.,” in The Archaeology of Western Iran, ed. F. Hole, Washington, D.C., 1987, pp. 205-28.

L. Jacobs, Darvazeh Tepe and the Iranian Highlands in the Second Millennium B.C., unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oregon, 1980.

T. Jacobsen, The Harps that Once . . . Sumerian Poetry in Translation, New Haven, 1987.

J.-F. Jarrige, “Continuity and Change in the North Kachi Plain (Baluchistan, Pakistan) at the Beginning of the Second Millennium BC,” in South Asian Archaeology 1983, ed. J. Scholtsmans and M. Taddei, Naples, 1985, pp. 35-68.

P. Kohl, The Seeds of Upheaval. The Production of Chlorite at Tepe Yahya and an Analysis of Commodity Production and Trade in Southwest Asia in the Third Millennium, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1974.

C. Kramer, “Pots and Peoples,” in Mountains and Lowlands. Essays in the Archaeology of Greater Mesopotamia, Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 7, ed. L. D. Levine and T. C. Young, Jr., Malibu, Calif., 1977, pp. 91-112.

C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, Excavations at Tepe Yahya, Iran, 1967-1969. Progress Report 1, American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 27, Cambridge, Mass., 1970.

Idem, “Foreign Relations in the Third Millennium at Tepe Yahya,” in Le Plateau iranien et l’Asie centrale des origines à la conquête islamique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Colloques Internationaux 567, Paris, 1977, pp. 33-44.

Idem and M. Tosi, “Shahr-i Sokhta and Tepe Yahya. Tracks on the Earliest History of the Iranian Plateau,” East and West 23, 1973, pp. 21-53.

L. Levine, “The Iron Age,” in The Archaeology of Western Iran, ed. F. Hole, Washington, D.C., 1987, pp. 229-50.

P. Meriggi, La scrittura proto-elamica, 3 vols., Rome, 1971-74.

E. Negahban, “Preliminary Report of the Excavations of Sagzabad,” in Memorial Volume of the VIth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, Oxford, 1972, Tehran, 1976, pp. 247-72.

P. E. Pecorella and M. Salvini, Tra lo Zagros e l’Urmia. Ricerche storiche ed archeologiche nell’Azerbaigian iraniano, Rome, 1984.

D. Potts, Tradition and Transformation. Tepe Yahya and the Iranian Plateau During the Third Millennium B.C., unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1980.

Idem, “The Potter’s Marks of Tepe Yahya,” Paléorient 7, 1981, pp. 107-22.

M. Prickett, Man, Land and Water. Settlement Distribution and the Development of Irrigation Agriculture in the Upper Rud-i Gushk Drainage, Southeastern Iran, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1996.

A. G. Sagona, The Caucasian Region in the Early Bronze Age, 3 vols., BAR International Series 214, Oxford, 1984.

S. Salvatore and M. Vidale, “A Brief Surface Survey of the Protohistoric Site of Shahdad (Kerman, Iran),” Rivista di archeologia 6, 1982, pp. 5-10.

R. Schacht, “Early Historic Cultures,” in The Archaeology of Western Iran, ed. F. Hole, Washington, D.C., 1987, pp. 171-204.

E. F. Schmidt, Excavations at Tepe Hissar, Damghan 1931-1933, Philadelphia, 1937.

W. M. Sumner, “Tall-e Maljan (Anshan),” RIA VII/3-4, 1988, pp. 306-20.

M. Tosi, “The Archaeology of Early States in Middle Asia,” Oriens antiquus 3-4, 1986, pp. 153-87.

Idem, ed., Prehistoric Sistan I, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, Centro Studi e Scavi Archeologici in Asia Reports and Memoirs 19/1, Rome, 1983.

L. Vanden Berghe, “Pusht-i Kuh, Luristan,” Iran 11, 1973, pp. 207-09.

M. M. Voigt and R. H. Dyson, Jr., “The Chronology of Iran, ca. 8000-2000 B.C.,” inChronologies in Old World Archaeology, 3rd ed., ed. R. Ehrich, Chicago, forthcoming.

H. Weiss and T. C. Young, Jr., “The Merchants of Susa. Godin V and Plateau-Lowland Relations in the Late Fourth Millennium B.C.,” Iran 13, 1975, pp. 1-18.

H. T. Wright, ed., An Early Town on the Deh Luran Plain. Excavations at Tepe Farukhabad, University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology Memoir 13, Ann Arbor, 1981.

T. C. Young, Jr., “Early Iron Age Iran Revisited. Preliminary Suggestions for the Re-Analysis of Old Constructs,” in De l’Indus aux Balkans, Receuil à la mémoire de Jean Deshayes, ed. J.-L. Huot, M. Yon, and Y. Calvet, Paris, 1985, pp. 361-78.

Idem and L. D. Levine, Excavations of the Godin Project. Second Progress Report, Royal Ontario Museum, Art and Archaeology Occasional Paper 26, Toronto, 1974.

Figure 29. Bronze Age sites in Iran and Afghanistan (Robert H. Dyson, Jr., and Mary M. Voigt)

Originally Published: December 15, 1989

Last Updated: December 15, 1989

This article is available in print.

Vol. IV, Fasc. 5, pp. 472-478

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-age

PROTO-ELAMITE HISTORY

By: R. K. Englund

![]() |

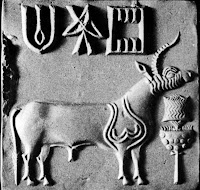

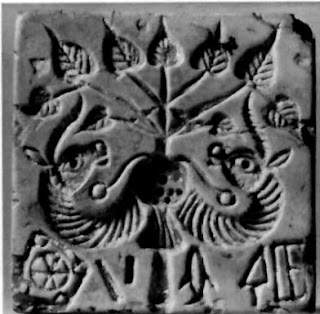

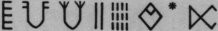

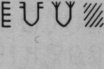

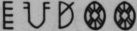

Figure 1. Proto-Elamite administrative account of four sheep herds. (Scheil, 1905, no. 212; scale 1:2) Figure 2. A proto-Elamite account of cereal rations for labor gangs of two superv isors (Scheil, 1905 no. 4997; (Click to enlarge)

Figure 3. Complex rotation of the proto-Elamite account (Scheil, 1905, no. 4997).(Click to enlarge)

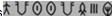

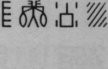

Figure 4. Numerical sign systems attested in the proto-Elamite text corpus (Damerow and Englund, 1989, 18-30; the numbers located above the arrows indicate how many respective units were replaced by the next higher unit). In the capacity system, the basic sign (= "1" in the systems qualifying discrete units) may have represented ca. 25 liters of grain. (Click to enlarge)

. |

"Proto-Elamite" is the term for a writing system in use in the Susiana plain and the Iranian highlands east of Mesopotamia between ca. 3050 and 2900 B.C.E., a period generally considered to correspond to the Jamdat Nasr/Uruk III through Early Dynastic I periods in Mesopotamia. This span is represented in Iran by levels 16-14B in the Acropole at Susa (Le Brun, 1971), as well as Tepe Yahya (Yahyâ) IVC, Sialk (Sîâlk) IV2, and Late Middle Banesh (Baneš). Proto-Elamite tablets are the earliest complex written documents from the region; the script consists of both numerical and ideographic signs, the latter sometimes assumed to represent a genetically related precursor of the Old Elamite language (see iv, below). This supposed precursor language is, however, unknown, and the script itself has been only partially deciphered. Nevertheless, conclusions about the contents of the Proto-Elamite texts can be drawn from contextual analyses and formal similarities to proto-cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia. In particular, the structure of published documents containing accounts and the use of numerical signs and of certain signs for objects in bookkeeping can be somewhat clarified.

History of decipherment

Since the first Proto-Elamite documents were discovered at the turn of the century (Scheil, 1900, pp. 130-31; Friberg, I, pp. 22-26) approximately 1,450 Proto-Elamite tablets from Susa have been published. Recent excavations at other sites have proved that the script and numerical systems known from Susa were in use at administrative centers ranging across Persia as far as the Afghan border, including the sites of Sialk, Malyan (Malîân), Yahya, and Shahr-i Sokhta (Šahr-e Sûkhta; Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 1-2; Stolper, 1985, pp. 6-8; Sumner, 1976; Carter and Stolper, p. 253; Nicholas, p. 45). The texts, written on clay tablets, seem without exception to be administrative documents: receipts and transfers of grain, livestock, and laborers; rationing texts; and so on. There are neither literary nor school texts of the sort known as "lexical lists" from contemporary Mesopotamia. The earlier "numerical tablets" from Godin (Gowdîn) Tepe V and Chogha Mish (Chogha Mîš, q.v.), generally dated contemporary with Uruk IVb and level 17 in the Acropole at Susa, lack ideographic signs and are thus not classified as Proto-Elamite (Weiss and Young, pp. 9-10; Porada, p. 58)

Some scholars have attempted to demonstrate a link between the Proto-Elamite and Linear Elamite scripts (see v, below; Hinz, 1975; Meriggi, 1971-74, I, pp. 184-200; Andre‚ and Salvini), but adducing syllabic values proposed for Linear Elamite has not led to successful deciphering of Proto-Elamite. A preliminary graphotactical analysis of the Proto-Elamite texts has also met with only modest success (Meriggi, 1975; idem, 1971-74, I, pp. 172-84; Brice, 1962-63, pp. 28-33; Gelb, 1975). Other scholars have attempted to establish a connection between Proto-Elamite and proto-cuneiform, which first appeared in Uruk IVa (ca. 3200-3100 B.C.E.) and thus seems to predate Proto-Elamite by about a century (Langdon, p. viii; de Mecquenem, p. 147; Gelb, 1952, pp. 217-20; Meriggi, 1969; Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 11-28).

Advances in the decipherment of Proto-Elamite have been hindered to a certain degree by the absence of necessary philological tools. A first step would be a sign list sufficiently dependable and cleansed of redundant variants to offer an approximate idea of the number and frequency of signs in the scribal repertoire, as well as providing a transcriptional instrument for analysis of sign combinations and simple contexts. Such textual work is a pre-requisite for a complete edition of the Proto-Elamite texts.

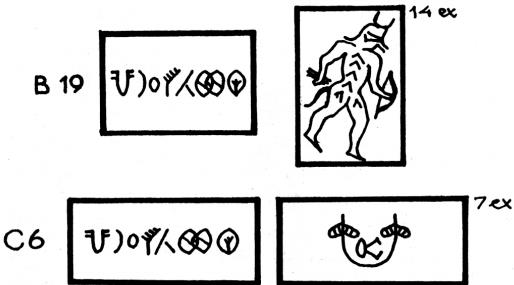

Sign lists provided by early editors (Scheil, 1905; idem 1923; idem, 1935; de Mecquenem; Meriggi, 1971-74) have proved wanting (Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 4-7). The first serious attempt at a formal description and decipherment of Proto-Elamite script was undertaken in the 1960s and early 1970s (Brice, 1962-63; idem, 1963; Meriggi, 1971-74; Vaiman, 1989a). Most recent advances have resulted from a new understanding of the structure of the numerical sign systems, which has provided a powerful tool for semantic identification of a number of ideograms, including those for grain products, animals, and, it seems, human beings (Vaiman, 1989a; Friberg, I; Damerow and Englund, 1989).

Format and semantic hierarchy

Proto-Elamite texts are written on clay tablets similar in general shape and proportions to Mesopotamian clay tablets of the 3rd millennium B.C.E., including Uruk III proto-cuneiform tablets of the later phase. The tablets are thick oblongs, their height and width normally in a ratio of 2:3. Following the convention established in the earliest proto-cuneiform phase, Proto-Elamite scribes used both sides of the tablet. Regardless of the space remaining after two or more entries on the obverse, the scribe usually rotated the tablet around a vertical axis and recorded the totals along the upper edge of the reverse. Larger accounts could have a more complex format (Brice, 1962-63, pp. 20-21; Vaiman, 1989a, pp. 130-32; Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 11-13; Figure 1).

Three features distinguish Proto-Elamite tablets from proto-cuneiform documents, however. First, the Proto-Elamite documents were written in a linear script. Second, the first signs on a tablet, the heading, have approximately the same function as the proto-cuneiform "colophon," which is usually inscribed together with the final total on the reverse of the tablet; Proto-Elamite headings never contain numerical notations, however. Third, each entry normally includes an ideogram followed by a numerical notation, a divergence from the strict sequence of numerical sign followed by ideogram in proto-cuneiform texts.

The heading of a Proto-Elamite tablet generally specifies the purpose and authorizing person or institution; the best known such ideographic designation is the so-called "hairy triangle", which seems to represent a leading institution or possibly kin group in Elam. Qualifying ideograms were inscribed within this sign, apparently to designate subordinate institutions or groups (Dittmann, 1986a, pp. 332-66; Lamberg-Karlovsky, p. 210; Damerow and Englund, 1989, p. 16). Following these introductory sign combinations are the individual entries, in horizontal registers without regard to formal arrangement into columns (Figures 2 & 3). The ideograms in Proto-Elamite text entries seem almost exclusively to denote persons, quantified objects, or both; sign combinations seeming to designate persons invariably precede those designating quantified objectswhen both appear in one notation. A sign or sign combination representing a person or title is often introduced by a sign representing his position. Objects are generally designated by ideograms in combination with qualifiers; as yet, however, there are no statistical means of testing the probability that certain signs functioned as qualifiers of presumed substantives.

In Proto-Elamite documents there can be multiple entries with different levels of internal organization. A text may consist simply of a sequence of entries of exactly the same type; an example would be a list of grain rations for a number of different recipients. A text may also embody a hierarchical order of transmitted information, as in the oft-encountered alternation of two different types of entry, perhaps a number of workers followed by the amount of grain allotted to them. In this instance the two entries may be considered to be combined in a more comprehensive text unit. A text may also, however, be highly structured, with many identifiable levels, reflecting, for instance, the organizational structure of a labor unit (Figures 2-3; Nissen, Damerow, and Englund, pp. 116-21).

That all entries seem to contain numerical notations suggests that they represent a bookkeeping system, rather than the distinct sentences or other comparable semantic units of a spoken language. This semantic structure is evidence of a close relation between Proto-Elamite and proto-cuneiform texts. Proto-Elamite headings correspond to the "colophons" that often accompany totals on proto-cuneiform texts. Entries in Proto-Elamite documents correspond to the physically encased notations on proto-cuneiform texts; curiously, the hierarchical structure of individual Proto-Elamite entries is not reflected in a syntactical structure, whereas in Mesopotamian texts this hierarchy continues to be represented in some measure by the graphic arrangement of cases and subcases. Despite different graphic forms, Proto-Elamite texts thus exhibit the same general semantic structure as that of proto-cuneiform texts. This relationship must be considered a strong indication of their relative chronology: The more developed linear syntax apparent in Proto-Elamite texts, in which the graphical arrangement of semantic units has been dispensed with, implies that proto-cuneiform is earlier. This conclusion is in full accord with the established stratigraphic correspondences between Susa and Uruk (Dittmann, 1986a, pp. 296-97, 458 table 159e; Dittmann, 1986b, p. 171 n. 1).

Numerical sign systems. Early work on the numerical notations in Proto-Elamite texts was hampered by inadequate identification of individual signs and in particular of sign systems, which were applied in Mesopotamia and Elam to record different types of objects. Initially there was an attempt to combine a large number of what are now recognized as incompatible numerical notations into a single "decimal" system (Scheil, 1905, pp. 115-18; idem, 1923, p. 3). This attempt was abandoned in 1935, when it was recognized that different numerical systems had been in use in Mesopotamia, particularly for enumeration of discrete objects and for measuring grain by capacity (Scheil, 1935, pp. i-vi). It was, however, mistakenly assumed that the sign had the same decimal value 10 x (instead of 6 x) when representing grain measures as when representing numbers of discrete objects (Thureau-Dangin, p. 29; Langdon, pp. v, 63-68; Vaiman, 1989a), which prevented understanding of capacity notations until the late 1970s (Friberg, 1978-79). Although detailed documentation of the various numerical systems has not yet been undertaken, the formal structure of these systems and their dependence upon the older proto-cuneiform systems are now clear (Damerow and Englund, 1987, pp. 117-21, 148-49 n. 12; idem, 1989, pp. 18-30).

As the semantic analysis of Proto-Elamite is largely dependent upon examination of the contexts in which signs are used, the close connection with proto-cuneiform sources in the numerical systems has been helpful in establishing correspondences between Proto-Elamite and proto-cuneiform ideograms. For example, the sexagesimal system used in Meso-potamia for most discrete objects, including domestic and wild animals, human beings, tools, products of wood and stone, and containers (sometimes in standard measures), is also well attested in the Susa administrative texts, though the field of application seems limited to inanimate objects like jars of liquid and arrows (Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 52-53). A decimal system used in Proto-Elamite texts for counting animals and human beings has no proto-cuneiform counterpart.

Bisexagesimal notations qualify barley products, as in contemporary Mesopotamian documents. The numerical system for indicating grain capacity involves signs from the sexagesimal system but with entirely different arithmetical values. This system is well attested in both Proto-Elamite and proto-cuneiform sources and seems to have had the same area of application. In particular, the small units inscribed below are qualifying ideograms for grain products, thus denoting the quantity of grain in one unit of the product. The Proto-Elamite system differs from the proto-cuneiform system in that below the sign only units that are multiples of one another appear (e.g. 1/2, 1/4, 1/8), a simpler system than the somewhat cumbersome use of fractions in proto-cuneiform texts (Damerow and Englund, 1987, pp. 136-41). As with the proto-cuneiform texts, in the Proto-Elamite texts there are numerical systems graphically derived from the basic systems but perhaps applied to different sorts of discrete objects or grain (Figure 3). All these similarities together suggest that the Proto-Elamite systems, with the exception of the decimal system, were borrowed from Mesopotamia; even signs in the decimal system were apparently borrowed from the Mesopotamian bisexagesimal system to represent the higher values 1,000 and 10,000.

Ideograms

Semantic analysis of the objects counted by the decimal system has led to the probable identification of a number of ideograms. The most important are the two signs (Symbol 3) and (Symbol 4) . The graphic form, as well as the association, of the ideogram (Symbol 3) with other signs strongly resembling proto-cuneiform signs known to represent domestic animals, in particular sheep and goats (Symbol 5), suggests the interpretation of this sign as "sheep" (Figure 1). In texts from the essentially rural economy of ancient Persia the large numerical notations qualifying this ideogram and related signs seem to confirm the identification. The fact that the signs are on the whole abstract forms may suggest either a set of symbols for domestic animals common in Mesopotamia and Susiana before the inception of written documents or, more likely, signs borrowed in altered form from Uruk (Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 53-55).

It appears that the very common sign (Symbol 4) was used to qualify personal names. All signs or sign combinations in a text may be introduced by it, though more commonly it introduces only the first entry (Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 53-55). The same sign was used as an ideogram for objects, together with decimal notations commonly used for counting animals. This double function suggests that the sign denotes a category of workers or slaves. The use of the sign in both ways is firmly established in the text illustrated in Figures 2-3 (Damerow and Englund, 1989, pp. 56-57; Nissen, Damerow, and Englund, pp. 116-21). In the same text numbers of objects represented by this ideogram correspond to a regular capacity measure of barley of 1/2 (Symbol 2), parallel to texts known from contemporary Mesopotamia. Finally, the sign is often used parallel to signs that may thus also be interpreted as referring to persons. One of them is a clear graphic equivalent of the proto-cuneiform sign SAL (Symbol 6), so that both the graphic and semantic correspondences of proto-Elamite (Symbol 4) to proto-cuneiform (Symbol 7), meaning "male slave/laborer" (Vaiman, 1989b), seem clear.

Bibliography

![]() | B. Andre‚ and M. Salvini, "Re‚flexions sur Puzur-Inšušinak," Iranica Antiqua 24, 1989, pp. 53-72. |

![]() | W. Brice, "The Writing System of the Proto-Elamite Account Tablets of Susa," Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 45, 1962-63, pp. 15-69. |

![]() | Idem, "A Comparison of the Account Tablets of Susa in the Proto-Elamite Script with Those of Hagia Triada in Linear A," Kadmos 2, 1963, pp. 27-38. |

![]() | E. Carter and M. Stolper, Elam. Surveys of Political History and Archaeology, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984. |

![]() | P. Damerow and R. K. Englund, "Die Zahlzeichensysteme der archäischen Texte aus Uruk," in M. Green and H. Nissen, eds., Zeichenliste der Archäischen Texte aus Uruk, Berlin, 1987, pp. 117-66. |

![]() | Idem, The Proto-Elamite Texts from Tepe Yahya, American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 39, Cambridge, Mass., 1989. |

![]() | R. Dittmann, Betrachtungen zur Frühzeit des Südwest-Iran, Berlin, 1986a. |

![]() | Idem, "Susa in the Proto–Elamite Period and Annotations on the Painted Pottery of Proto-Elamite Khuzestan," in U. Finkbeiner and W. Röllig, eds., G¦amdat Nasár. Period or Regional Style? Wies-baden, 1986b, pp. 332-66. |

![]() | J. Friberg, The Early Roots of Babylonian Mathematics, 2 vols., Göteborg, 1978-79. I. Gelb, A Study of Writing, Chicago, 1952. |

![]() | Idem, "Methods of Decipherment," JRAS, 1975, pp. 95-104. W. Hinz, "Persia ca. 2400-1800 B.C.," in I. Edwards, C. Gadd, and N. Hammond, eds., The Cambridge Ancient History I/2, Cambridge, 1971, pp. 644-80. |

![]() | Idem, "Problems of Linear Elamite," JRAS 1975, pp. 106-15. C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, "Third Millennium Structure and Process. From the Euphrates to the Indus and the Oxus to the Indian Ocean," Oriens Antiquus25, 1986, pp. 189-219. |

![]() | S. Langdon, Pictographic Inscriptions from Jemdet Nasr, Oxford Editions of Cuneiform Texts 7, Oxford, 1928. |

![]() | A. Le Brun, "Recherches stratigraphiques a l'Acropole de Suse, 1969-1971," |

![]() | CDAFI 1, 1971, pp. 163-216. |

![]() | R. de. Mecquenem, Î, Me‚moires de la De‚le‚gation en Perse 31, Paris, 1949. |

![]() | P. Meriggi, "Altsumerische und proto-elamische Bilderschrift," ZDMG Suppl. 1, 1969, pp. 156-63. |

![]() | Idem, La scrittura proto-elamica, 3 vols., Rome, 1971-74. |

![]() | Idem, "Comparaisons des systemes ide‚o-graphiques mino-myce‚nien et proto-e‚lamique," in M. Ruipe‚rez, ed.,Acta Mycenaea II, Minos 12, 1972, pp. 9-17. |

![]() | Idem, "Der Stand der Erforschung des Proto-elamischen," JRAS, 1975, p. 105. |

![]() | I. Nicholas, "Investigating an Ancient Suburb," Expedition 23, 1981, pp. 39-47. |

![]() | H. Nissen, P. Damerow, and R. Englund, Frühe Schrift und Techniken der Wirtschaftsverwaltung im alten Vorderen Orient, 2nd ed., Bad Salzdetfurth, Germany, 1991. |

![]() | E. Porada, "Iranian Art and Archaeology. A Report of the Fifth International Congress, 1968," Archaeology 22, 1969, pp. 54-65. |

![]() | E. Reiner, "The Elamite Language," in B. Spuler, ed., Altkleinasiatische Sprachen, Leiden, 1969, pp. 54-118. |

![]() | V. Scheil, Textes e‚lamites-se‚mitiques, Me‚moires de la De‚le‚gation en Perse 2, Paris, 1900. |

![]() | Idem, Documents en e‚criture proto-e‚lamite, Me‚moires de la De‚le‚gation en Perse 6, Paris, 1905. |

![]() | Idem, Textes de comptabilite‚ proto-e‚lamites, Me‚moires de la De‚le‚gation en Perse 17, Paris, 1923. |

![]() | Idem, Textes de comptabilite‚ proto-e‚lamites, Me‚moires de la De‚le‚gation en Perse 26, Paris, 1935. |

![]() | M. Stolper, "Proto-Elamite Texts from Tall-i Malyan," Kadmos 24, 1985, pp. 1-12. |

![]() | W. Sumner, "Excavations at Tall-i Malyân (Anshan) 1974," Iran 14, 1976, pp. 103-15. |

![]() | F. Thureau-Dangin, "Tablettes a signes picturaux," RA 24, 1927, pp. 23-29. |

![]() | A. Vaiman, "Die Bezeichnung von Sklaven und Sklavinnen in der protosumerischen Schrift," tr. T. Götzett, inBaghdader Mitteilungen 20, 1989a, pp. 121-33. |

![]() | Idem, "Über die Beziehungen der protoelamischen zur protosumeriscnen Schrift," tr. I Damerow, in Baghdader Mitteilungen 20, 1989b, pp. 101-14. |

![]() | H. Weiss and T. C. Young, Jr., "The Merchants of Susa. Godin V and Plateau-Lowland Relations in the Late Fourth Millennium B.C.," Iran 13, 1975, pp. 1-17. |

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/History/Elamite/proto_elam_history.htm

cf. Mirrored at http://cdli.ucla.edu/staff/englund/publications/englund1998a.pdf

See: http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=proto-elamite

Susa. "Copper came from Magan and later Dilmun through the Persian Gulf (Tallon). Tin reached Mesopotamia through Susa and probably also through some route(s) through the central or northern Zagros to Assur (Larsen; Cleziou and Berthoud; Tallon). The Habur ware assemblage at Dînkhâ Tappa (q.v.; Hasanlû VI) in northwestern Persia reflects strong contact with northern Mesopotamia in the early second millennium (Hamlin). " Henrickson, Robert C., Economy of Ancient Iran, Economy in Pre-Achaemenid Iran http://flh.tmu.ac.ir/hoseini/mad-hakha/articles-1/79.htm

Bharhut. Coping rail.

Bharhut. Coping rail.

Bharhut

Bharhut

Flip horizontal

Flip horizontal

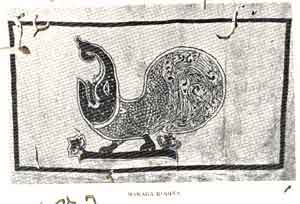

Besnagar. Makara dhvaja with makara.on capital of pillar.

Besnagar. Makara dhvaja with makara.on capital of pillar.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

Bedse caves

Bedse caves

Most of Hasankeyf in Batman province, Turkey, will be underwater once Ilisu dam is completed. Photograph: Zuma Press, Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

Most of Hasankeyf in Batman province, Turkey, will be underwater once Ilisu dam is completed. Photograph: Zuma Press, Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

The American scientists Jeffrey C Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W Young, who have won this year’s prize. Illustration: NobelPrize.org

The American scientists Jeffrey C Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W Young, who have won this year’s prize. Illustration: NobelPrize.org

eruvai 'eagle' rebus: eruvai 'copper'

eruvai 'eagle' rebus: eruvai 'copper'

Article Info

Article Info

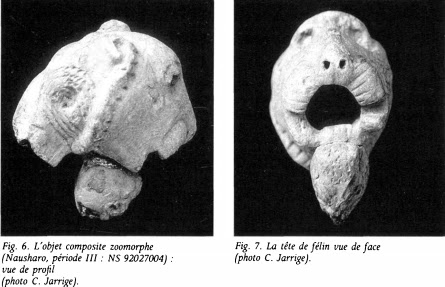

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.

A hieroglyph with the most frequent occurrence on Indus Script Corpora.

A hieroglyph with the most frequent occurrence on Indus Script Corpora.

.png)

m1429 prism tablet. Boat glyph as a Sarasvati hieroglyph on a tablet.Three sided molded tablet. One side shows a flat bottomed boat with a central hut that has leafy fronds at the top of two poles. Two birds sit on the deck and a large double rudder extends from the rear of the boat. On the second side is a snout nosed gharial with a fish in its mouth. The third side has eight glyphs of the Indus script.

m1429 prism tablet. Boat glyph as a Sarasvati hieroglyph on a tablet.Three sided molded tablet. One side shows a flat bottomed boat with a central hut that has leafy fronds at the top of two poles. Two birds sit on the deck and a large double rudder extends from the rear of the boat. On the second side is a snout nosed gharial with a fish in its mouth. The third side has eight glyphs of the Indus script.

Steppe eagle Aquila nipalensis

Steppe eagle Aquila nipalensis

m0309 Mohenjo-daro seal (Tree and a person on a tree branch)

m0309 Mohenjo-daro seal (Tree and a person on a tree branch)

Harappa tablet h188A, B

Harappa tablet h188A, B