https://tinyurl.com/y9rzar7d

Composite animals of Indus Script corpora are hypertexts.

The cipher of the ancient writing system of Indus Script dated to ca. 3300 BCE is structured to function at two levels: 1. mlecchita vikalpa, 'alternative representation of message by mleccha'copper' workers, 'weapons makers'; and 2.vākyapadīya, 'sentences composed of words to convey meaning'.

mlecchita vikapa is characterized by indistinct speech and incorrect, ungrammatical pronunciations, i.e. vernacula, parole. This expression is used by Vātsyāyana to refer to a cipher writing system as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mlecchita_vikalpa

vākyapadīya is meaning conveyed through a sentence composed of pada, 'sign, token, characteristic, word'. भर्तृहरि Bhartṛhari is author of the work, Vākyapadīya, 'treatise on words and sentences.'"The work is divided into three books, the Brahma-kāṇḍa, (or Āgama-samuccaya "aggregation of traditions"), the Vākya-kāṇḍa, and the Pada-kāṇḍa (or Prakīrṇaka "miscellaneous"). He theorized the act of speech as being made up of three stages:

![Image result for composite animal indus script]() A truly fascinating paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at a.harappa.com/...

A truly fascinating paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at a.harappa.com/...

Hypertext includes the following hieroglyphs rendered rebus and read as vākyapadīya, sentence composed of words : The deciphered text is: metal ingots manufactory & trade of magnetite, ferrite ore, metals mint with portable furnace, iron ores, gold, smelters' guild.

The Meluhha rebus words and meanings are given below.

सांगड sāṅgaḍa f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together. Rebus: sangara'trade'

1. zebu पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'

2. human face mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot

3. penance kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakrit) kamaḍha, kamaṭha, kamaḍhaka, kamaḍhaga, kamaḍhaya = a type of penance (Prakrit) Rebus: kamaṭamu, kammaṭamu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammaṭīḍu = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Telugu) kãpṛauṭ jeweller's crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Tamil)

4. elephant karabha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant' kharva 'a nidhi of nine treasures of Kubera'

5. markhor miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.) Rebus: meḍ(Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Mu.) Allograph: meḍ‘body ' (Mu.)

6. young bull kondh ‘young bull’ rebus: kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker, engraver (writer)’ kundana 'fine gold'

7. tiger kul 'tiger' (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.)Pk. kolhuya -- , kulha -- m. ʻ jackal ʼ < *kōḍhu -- ; H.kolhā, °lā m. ʻ jackal ʼ Rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' kolle 'blacksmith' kole.l 'smithy, forge' kole.l 'temple'

8. Cobra hood phaḍa'throne, hood of cobra' rebus: फड, phaḍa'metalwork artisan guild in charge of manufactory'

![]() This hieroglyph on Seal m1179 is a determinative that the message conveyed by 'composite animals' is that the locus is kole.l'temple/' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'.

This hieroglyph on Seal m1179 is a determinative that the message conveyed by 'composite animals' is that the locus is kole.l'temple/' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'.

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 zebu pot]() A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.. पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] '

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.. पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] '

![]()

![]() m1186 Composite animal hieroglyph. Text of inscription (3 lines).

m1186 Composite animal hieroglyph. Text of inscription (3 lines).

![Related image]() m0301

m0301![]() m0302

m0302![]() m0303

m0303![]() m1177

m1177![]() m0299

m0299![Related image]() m0300

m0300![]() m1179 Markhor or ram with human face in composite hieroglyph

m1179 Markhor or ram with human face in composite hieroglyph

![Related image]() m1180

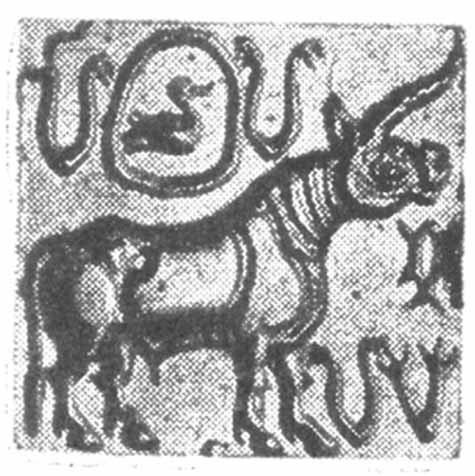

m1180![]() h594 h594. Harappa seal. Composite animal (with elephant trunk and rings (scarves) on shoulder visible).koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.) Rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

h594 h594. Harappa seal. Composite animal (with elephant trunk and rings (scarves) on shoulder visible).koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.) Rebus: koḍ 'workshop'![]() m1175 Composite animal with a two-glyph inscription (water-carrier, rebus: kuti 'furnace'; road, bata; rebus: bata 'furnace')

m1175 Composite animal with a two-glyph inscription (water-carrier, rebus: kuti 'furnace'; road, bata; rebus: bata 'furnace')

![]()

![]() Dwaraka Turbinellapyrum seal

Dwaraka Turbinellapyrum seal

On this seal, the key is only 'combination of animals'. This is an example of metonymy of a special type called synecdoche. Synecdoche, wherein a specific part of something is used to refer to the whole, or the whole to a specific part, usually is understood as a specific kind of metonymy. Three animal heads are ligatured to the body of a 'bull'; the word associated with the animal is the intended message.The ciphertext of this composite animal is to be decrypted by rendering the sounds associated with the animals in the combination: ox, young bull, antelope. The rebus readings are decrypted with metalwork categories: barad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; kondh ‘young bull’ rebus: kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker, engraver (writer)’ kundana 'fine gold'; ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.![]()

The rebus readings of the hieroglyphs are: mẽḍha ‘antelope’; rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) aya 'fish'; rebus: aya 'cast metal' (G.).![]() Fig. 96f: Failaka no. 260

Fig. 96f: Failaka no. 260

Double antelope joined at the belly; in the Levant, similar doubling occurs for a lion.

pr̥ṣṭhá n. ʻ back, hinder part ʼ Rigveda; puṭṭhā m. ʻ buttock of an animal ʼ (Punjabi) Rebus: puṭhā, puṭṭhā m. ʻbuttock of an animal, leather cover of account bookʼ (Marathi) tagara 'antelope' Rebus: damgar 'merchant'. This may be an artistic rendering of a 'descendant' of a ancient (metals) merchant. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2012/05/antithetical-antelopes-of-ancient-near.html Antithetical antelopes of Ancient Near East as hieroglyphs (Kalyanaraman 2012) Hieroglyph: Joined back-to-back: pusht ‘back’; rebus: pusht ‘ancestor’. pus̱ẖt bah pus̱ẖt ‘generation to generation.’

![]() One-horned heifer ligatured to an octopus. This composite glyph occurs on a seal (Mohenjodaro) and also on a copper plate (tablet)(Harappa). This glyph is decoded as: smithy guild in a citadel (enclosure), with a warehouse (granary), beṛhī

One-horned heifer ligatured to an octopus. This composite glyph occurs on a seal (Mohenjodaro) and also on a copper plate (tablet)(Harappa). This glyph is decoded as: smithy guild in a citadel (enclosure), with a warehouse (granary), beṛhī

m297a: Seal h1018a: copper plate

A lexeme for a Gangetic/Indus river octopus is retained as a cultural memory only in Jatki (language of the Jats) of Punjab-Sindh region. The lexeme is veṛhā. A homonym closest to this is beṛā building with a courtyard (WPah.) There are many cognate lexemes in many languages of Bharat constituting a semantic cluster of the linguistic area (as detailed below). The rebus decoding of veṛhā (octopus); rebus: beṛā (building with a courtyard) is a reading consistent with (1) the decoding of the rest of the corpus of epigraphs as mleccha smith guild tokens; and (2) the archaeological evidence of buildings/workers’ platforms within an enclosed fortification on many sites of the civilization.

Many languages of Bharat, that is India, evolved from meluhha (mleccha) which is the lingua franca of the civilization. The language is mleccha vaacas contrasted with arya vaacas in Manusmruti (as spoken tongue contrasted with grammatically correct literary form, arya vaacas). The hypothesis on which decoding of Indus script is premised, is that lexemes of many Indian languages are evidence of the linguistic area of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization; the artefacts with the Indus script (such as metal tools/weapons, Dholavira signboard, copper plates, gold pendant, silver/copper seals/tablets etc.) are mleccha smith guild tokens -- a tradition which continues on mints issuing punch-marked coins from ca. 6th cent. BCE.

veṛhā octopus, said to be found in the Indus (Jaṭki lexicon of A. Jukes, 1900)

L. veṛh, vehṛ m. fencing; Mth. beṛhī granary; L. veṛhā, vehṛā enclosure containing many houses; beṛā building with a courtyard (WPah.) (CDIAL 12130)

koḍ = artisan’s workshop (Kuwi); koḍ ‘horn’ damṛa, koḍiyum ‘heifer’ (G.) rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’; koḍ ‘workshop’ (G.); ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.)

![]() Tell AsmarCylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron'. kāṇḍā 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. karā 'crocodile' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Tell AsmarCylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron'. kāṇḍā 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. karā 'crocodile' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)![]()

One side (m1431B) of a four-sided tablet shows a procession of a tiger, an elephant and a rhinoceros (with fishes (or perhaps, crocodile) on top?).![]()

![]() Inscription on Nausharo pot

Inscription on Nausharo pot

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Kur. xolā tail. Malt. qoli id.(DEDR 2135) The 'tail' atop the reed-structure banner glyph is a phonetic determinant for kole.l 'temple, smithy'. Alternative: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus:pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

Kur. xolā tail. Malt. qoli id.(DEDR 2135) The 'tail' atop the reed-structure banner glyph is a phonetic determinant for kole.l 'temple, smithy'. Alternative: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus:pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

![]() Text 1330 (appears with zebu glyph). Shown as exiting the kole.l 'smithy' arekol 'blaksmiths' and kũderā 'lathe-workers'.

Text 1330 (appears with zebu glyph). Shown as exiting the kole.l 'smithy' arekol 'blaksmiths' and kũderā 'lathe-workers'.

![]()

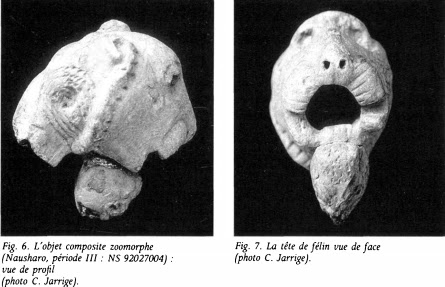

![]() A composite terracotta feline wearing necklace like a woman. kola 'tiger' kola 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Nahali (kol ‘woman’) and Santali (kul ‘tiger’; kol ‘smelter’).

A composite terracotta feline wearing necklace like a woman. kola 'tiger' kola 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Nahali (kol ‘woman’) and Santali (kul ‘tiger’; kol ‘smelter’).

http://www.harappa.com/figurines/index.html kola 'tiger' kola 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan

blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge(DEDR 2133).

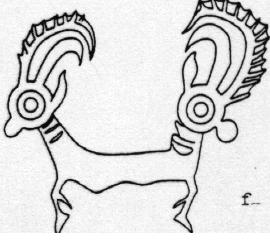

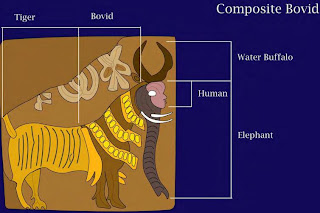

![]() The composite animal (bovid) is re-configured by Huntington. http://huntington.wmc.ohio-state.edu/public/index.cfm Components of the composite hieroglyph on seal M-299. A ligaturing element is a human face which is a hieroglyph read rebus in mleccha (meluhha): mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot (Santali). Using such readings, it has been demonstrated that the entire corpora of Indus writing which now counts for over 5000 inscriptions + comparable hieroglyphs in contact areas of Dilmun where seals are deployed using the characeristic hieroglyphs of four dotted circles and three linear strokes.

The composite animal (bovid) is re-configured by Huntington. http://huntington.wmc.ohio-state.edu/public/index.cfm Components of the composite hieroglyph on seal M-299. A ligaturing element is a human face which is a hieroglyph read rebus in mleccha (meluhha): mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot (Santali). Using such readings, it has been demonstrated that the entire corpora of Indus writing which now counts for over 5000 inscriptions + comparable hieroglyphs in contact areas of Dilmun where seals are deployed using the characeristic hieroglyphs of four dotted circles and three linear strokes.

म्लेच्छा* स्य = mleccha-mukha n. " foreigner-face " , copper (so named because the complexion of the Greek and Muhammedan invaders of India was supposed to be copper-coloured) L.म्लेच्छितक n. the speaking in a foreign jargon (unintelligible to others) Cat.; म्लेच्छन [p= 838,1] n. the act of speaking confusedly or barbarously Dha1tup.; म्लिष्ट [p= 837,3] mfn. spoken indistinctly or barbarously Pa1n2. 7-2 , 18; withered , faded , faint (= म्लान) L.; n. indistinct speech , a foreign language L. म्लेच्छित [p= 838,1] mfn.

= म्लिष्ट Pa1n2. 7-2 , 18 Sch.; n. a foreign tongue L. म्लान n. withered or faded condition , absence of brightness or lustre VarBr2S.; mfn. faded , withered , exhausted , languid , weak , feeble MBh. Ka1v. &c; म्लेच्छ [p= 837,3] any person who does not speak Sanskrit and does not conform to the usual Hindu institutions S3Br. &c (f(ई).) म्लेच्छ--ता f. the condition of barbarian VP. म्लेच्छ--भाषा f. a foreign or barbarous language MBh. म्लेच्छ--वाच् mfn. speaking a barbarous language (i.e. not Sanskrit ; opp. to आर्य-वाच्) Mn. x , 43.

म्लेच्छ--जाति [p= 837,3] m. a man belonging to the म्लेच्छs , a barbarian , savage , mountaineer (as a किरात , शबर or पुलिन्द) MBh. म्लेच्छ--मण्डल n. the country of the म्लेच्छs or barbarian W.

म्लेच्छ a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons L.; म्लेच्छn. copper

L.; n. vermilion L.; म्लेच्छा* ख्य [p= 838,1] n. " called म्लेच्छ " , copper L.

पद n. (rarely m.) a step , pace , stride; a footstep , trace , vestige , mark , the foot itself , RV. &c (पदेन , on foot ; पदे पदे , at every step , everywhere , on every occasion ; त्रीणि पदानि विष्णोः , the three steps or footprints of विष्णु [i.e. the earth , the air , and the sky ; cf. RV. i , 154 , 5 Vikr. i , 19], also N. of a constellation or according to some " the space between the eyebrows " ; sg. विष्णोः पदम् N. of a locality ; पदं- √दा,पदात् पदं- √गम् or √चल् , to make a step , move on ; पदं- √कृ , with loc. to set foot in or on , to enter ; with मूर्ध्नि , to set the foot upon the head of [gen.] i.e. overcome ; with चित्ते or हृदये , to take possession of any one's heart or mind ; with loc. or प्रति , to have dealings with ; पदं नि- √धा with loc. , to set foot in = to make impression upon ; with पदव्याम् , to set the foot on a person's [gen. or ibc.] track , to emulate or equal ; पदम् नि- √बन्ध् with loc. , to enter or engage in)

पद a word or an inflected word or the stem of a noun in the middle cases and before some तद्धितs Pa1n2. 1-4 , 14 &c = पद-पाठ Pra1t.

पद a sign , token , characteristic MBh. Katha1s. Pur.

पद protection L. [cf. Lat. peda ; op-pidum for op-pedum.]

वाच्[p= 936,1] f. (fr. √ वच्) speech , voice , talk , language (also of animals) , sound (also of inanimate objects as of the stones used for pressing , of a drum &c ) RV. &c (वाचम्- √ऋ , ईर् , or इष् , to raise the voice , utter a sound , cry , call); a word , saying , phrase , sentence , statement , asseveration Mn. MBh. &c (वाचं- √वद् , to speak words ; वाचं व्या- √हृ , to utter words ; वाचं- √दा with dat. , to address words to ; वाचा सत्यं- √कृ , to promise verbally in marriage , plight troth); Speech personified (in various manners or forms e.g. as वाच् आम्भृणी in RV. x , 125 ; as the voice of the middle sphere in Naigh.and Nir. ; in the वेद she is also represented as created by प्रजा-पति and married to him ; in other places she is called the mother of the वेदs and wife of इन्द्र ; in VP. she is the daughter of दक्ष and wife of कश्यप ; but most frequently she is identified with भारती or सरस्वती , the goddess of speech ; वाचः साम and वाचो व्रतम् N. of सामन्s A1rshBr. ; वाचः स्तोमः , a partic. एका*हS3rS. )

वाक्य--पदीय [p= 936,2] n. N. of a celebrated wk. on the science of grammar by भर्तृ-हरि (divided into ब्रह्म-काण्ड or आगम-समुच्चय , वाक्य-काण्ड , पद-काण्ड or प्रकीर्णक);वाक्य b [p= 936,2] a periphrastic mode of expression Pa1n2. Sch. Siddh.; a rule , precept , aphorism MW.; a sentence , period Ra1matUp. Pa1n2. Va1rtt. &c; n. (ifc. f(आ).) speech , saying , assertion , statement , command , words (मम वाक्यात् , in my words , in my name) MBh. &c; a declaration (in law) , legal evidence Mn.;an express declaration or statement (opp. to लिङ्ग , " a hint " or indication) Sarvad.; (in logic) an argument , syllogism or member of a syllogism; (in astron.) the solar process in computations MW.

Ligaturing of glyphs on the Indus script is paralleled by sculpted ligatures of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization

Glyphs on Indus script: Ligatured human body, metal wheelwright

There are many variants of this human body glyph (Sign 1, Mahadevan Indus script corpus). There are many composite glyphs with many ligatures to this human body frame.

meḍ ‘body’ (Santali) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron (metal)’ (Ho.) koṭe meṛed= forged iron (Mu.) (cf. glyph: Ka. kōḍu horn)

Vikalpa: kāṭhī = body, person; kāṭhī the make of the body; the stature of a man (G.) Rebus: khātī ‘wheelwright’ (H.)

eṛaka 'upraised arm' (Ta.); Ka.eṟake wing; rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.); eraka ‘metal infusion’ (Tu.)

Characteristic ligatures are: scarf on hair-pigtail, armlets on arms, raised arm, seated (hidden, spy?) on a tree, ligatured to buttocks (back) of a bovine, horned (often with a twig betwixt horns).

All these orthographic glyptic elements can be explained rebus as mleccha smith guild token glyphs, all in the context of a smithy/forge/smithy guild. This decoding is consistent with rebus readings of other glyphs such as ligatured tiger + eagle, tiger+ wings, tiger+ human body.

Some of these ligaturing elements and glyphs can be decoded, read rebus in mleccha lexemes.

Composite animals of Indus Script corpora are hypertexts.

The cipher of the ancient writing system of Indus Script dated to ca. 3300 BCE is structured to function at two levels: 1. mlecchita vikalpa, 'alternative representation of message by mleccha'copper' workers, 'weapons makers'; and 2.vākyapadīya, 'sentences composed of words to convey meaning'.

mlecchita vikapa is characterized by indistinct speech and incorrect, ungrammatical pronunciations, i.e. vernacula, parole. This expression is used by Vātsyāyana to refer to a cipher writing system as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mlecchita_vikalpa

vākyapadīya is meaning conveyed through a sentence composed of pada, 'sign, token, characteristic, word'. भर्तृहरि Bhartṛhari is author of the work, Vākyapadīya, 'treatise on words and sentences.'"The work is divided into three books, the Brahma-kāṇḍa, (or Āgama-samuccaya "aggregation of traditions"), the Vākya-kāṇḍa, and the Pada-kāṇḍa (or Prakīrṇaka "miscellaneous"). He theorized the act of speech as being made up of three stages:

- Conceptualization by the speaker (Paśyantī "idea")

- Performance of speaking (Madhyamā "medium")

- Comprehension by the interpreter (Vaikharī "complete utterance").

Bhartṛhari is of the śabda-advaita "speech monistic" school which identifies language and cognition. According to George Cardona, "Vākyapadīya is considered to be the major Indian work of its time on grammar, semantics and philosophy." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spho%E1%B9%ADa The work is on Sanskrit grammar and linguistic philosophy, is a foundational text in the Indian grammatical tradition, explaining numerous theories related to vāk, 'speech' and sphoṭa 'sound of language'. He identifies varṇasphoṭa, padasphoṭa and vākyasphoṭa 'syllable speech sound', 'word speech sound' and 'sentence speech sound'. Meaning is determined when the full sentence is uttered and heard. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhart%E1%B9%9Bhari

Good examples of these two components of Indus Script cipher -- mlecchita vikalpa and vākyapadīya are Indus Script hypertexts formed as 'composite animals'. The scribe who created these hypertexts signifies vākyasphoṭa 'sentence speech sound' of Mleccha/Meluhha speech which is cognate with literary Samskrtam or Chandas expressions.Hypertext includes the following hieroglyphs rendered rebus and read as vākyapadīya, sentence composed of words : The deciphered text is: metal ingots manufactory & trade of magnetite, ferrite ore, metals mint with portable furnace, iron ores, gold, smelters' guild.

The Meluhha rebus words and meanings are given below.

1. zebu पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: पोळ [ pōḷa ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore'

2. human face mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot

3. penance kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakrit) kamaḍha, kamaṭha, kamaḍhaka, kamaḍhaga, kamaḍhaya = a type of penance (Prakrit) Rebus: kamaṭamu, kammaṭamu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammaṭīḍu = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Telugu) kãpṛauṭ jeweller's crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Tamil)

4. elephant karabha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant' kharva 'a nidhi of nine treasures of Kubera'

5. markhor miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.) Rebus: meḍ(Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Mu.) Allograph: meḍ‘body ' (Mu.)

6. young bull kondh ‘young bull’ rebus: kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker, engraver (writer)’ kundana 'fine gold'

7. tiger kul 'tiger' (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.)Pk. kolhuya -- , kulha -- m. ʻ jackal ʼ < *kōḍhu -- ; H.kolhā, °lā m. ʻ jackal ʼ Rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' kolle 'blacksmith' kole.l 'smithy, forge' kole.l 'temple'

8. Cobra hood phaḍa'throne, hood of cobra' rebus: फड, phaḍa'metalwork artisan guild in charge of manufactory'

This hieroglyph on Seal m1179 is a determinative that the message conveyed by 'composite animals' is that the locus is kole.l'temple/' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'.

This hieroglyph on Seal m1179 is a determinative that the message conveyed by 'composite animals' is that the locus is kole.l'temple/' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge'. A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.. पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] '

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE. Cf. Fig. 2.18, J.M. Kenoyer, 1998, Cat. No. 8.. पोळ [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods, marked with a trident and discus, and set at large. पोळी [ pōḷī ] dewlap. पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'There are many examples of the depiction of 'human face' ligatured to animals:

Ligatured faces: some close-up images.

The animal is a quadruped: pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.)Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali) Allograph: panǰā́r ‘ladder, stairs’(Bshk.)(CDIAL 7760) Thus the composite animal connotes a smithy. Details of the smithy are described orthographically by the glyphic elements of the composition.

Rebus reading of the 'face' glyph: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali)mũh metal ingot (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali)

A remarkable phrase in Sanskrit indicates the link between mleccha and use of camels as trade caravans. This is explained in the lexicon of Apte for the lexeme: auṣṭrika 'belonging to a camel'. The lexicon entry cited Mahābhārata: औष्ट्रिक a. Coming from a camel (as milk); Mb.8. 44.28; -कः An oil-miller; मानुषाणां मलं म्लेच्छा म्लेच्छाना- मौष्ट्रिका मलम् । औष्ट्रिकाणां मलं षण्ढाः षण्ढानां राजयाजकाः ॥ Mb.8.45.25. From the perspective of a person devoted to śāstra and rigid disciplined life, Baudhāyana thus defines the word म्लेच्छः mlēcchḥ : -- गोमांसखादको यस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्वाचारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥ 'A person who eatrs meat, deviates from traditional practices.'

The 'face' glyph is thus read rebus: mleccha mũh 'copper ingot'.

It is significant that Vatsyayana refers to crptography in his lists of 64 arts and calls it mlecchita-vikalpa, lit. 'an alternative representation -- in cryptography or cipher -- of mleccha words.'

The glyphic of the hieroglyph: tail (serpent), face (human), horns (bos indicus, zebu or ram), trunk (elephant), front paw (tiger),

xolā = tail (Kur.); qoli id. (Malt.)(DEDr 2135). Rebus: kol ‘pañcalōha’ (Ta.)கொல் kol, n. 1. Iron; இரும்பு. மின் வெள்ளி பொன் கொல்லெனச் சொல்லும் (தக்கயாகப். 550). 2. Metal; உலோகம். (நாமதீப. 318.) கொல்லன் kollaṉ, n. < T. golla. Custodian of treasure; கஜானாக்காரன். (P. T. L.) கொல்லிச்சி kollicci, n. Fem. of கொல்லன். Woman of the blacksmith caste; கொல்லச் சாதிப் பெண். (யாழ். அக.) The gloss kollicci is notable. It clearly evidences that kol was a blacksmith. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); Koḍ. kollë blacksmith (DEDR 2133). Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge (DEDR 2133) கொல்² kol Working in iron; கொற்றொழில். Blacksmith; கொல்லன். (Tamil) mũhe ‘face’ (Santali); Rebus: mũh '(copper) ingot' (Santali);mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) கோடு kōṭu : •நடுநிலை நீங்குகை. கோடிறீக் கூற் றம் (நாலடி, 5). 3. [K. kōḍu.] Tusk; யானை பன்றிகளின் தந்தம். மத்த யானையின் கோடும் (தேவா. 39, 1). 4. Horn; விலங்கின் கொம்பு. கோட்டிடை யாடினை கூத்து (திவ். இயற். திருவிருத். 21). Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kwṛ (obl. kwṭ-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn (DEDR 2200)Rebus: koḍ = the place where artisans work (G.) kul 'tiger' (Santali); kōlu id. (Te.) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.)Pk. kolhuya -- , kulha -- m. ʻ jackal ʼ < *kōḍhu -- ; H.kolhā, °lā m. ʻ jackal ʼ, adj. ʻ crafty ʼ; G. kohlũ, °lũ n. ʻ jackal ʼ, M. kolhā, °lā m. krōṣṭŕ̊ ʻ crying ʼ BhP., m. ʻ jackal ʼ RV. = krṓṣṭu -- m. Pāṇ. [√kruś] Pa. koṭṭhu -- , °uka -- and kotthu -- , °uka -- m. ʻ jackal ʼ, Pk. koṭṭhu -- m.; Si. koṭa ʻ jackal ʼ, koṭiya ʻ leopard ʼ GS 42 (CDIAL 3615). कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [ kōlhēṃ ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pañcaloha’ (Ta.) Allograph: kōla = woman (Nahali) [The ligature of a woman to a tiger is a phonetic determinant; the scribe clearly conveys that the gloss represented is kōla] karba 'iron' (Ka.)(DEDR 1278) as in ajirda karba 'iron' (Ka.) kari, karu 'black' (Ma.)(DEDR 1278) karbura 'gold' (Ka.) karbon 'black gold, iron' (Ka.) kabbiṇa 'iron' (Ka.) karum pon 'iron' (Ta.); kabin 'iron' (Ko.)(DEDR 1278) Ib 'iron' (Santali) [cf. Toda gloss below: ib ‘needle’.] Ta. Irumpu iron, instrument, weapon. a. irumpu,irimpu iron. Ko. ibid. To. Ib needle. Koḍ. Irïmbï iron. Te. Inumu id. Kol. (Kin.) inum (pl. inmul)iron, sword. Kui (Friend-Pereira) rumba vaḍi ironstone (for vaḍi, see 5285). (DEDR 486) Allograph: karibha -- m. ʻ Ficus religiosa (?) [Semantics of ficus religiosa may be relatable to homonyms used to denote both the sacred tree and rebus gloss: loa, ficus (Santali); loh ‘metal’ (Skt.)]

miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120)bhēḍra -- , bhēṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ lex. [← Austro -- as. J. Przyluski BSL xxx 200: perh. Austro -- as. *mēḍra ~ bhēḍra collides with Aryan mḗḍhra -- 1 in mēṇḍhra -- m. ʻ penis ʼ BhP., ʻ ram ʼ lex. -- See also bhēḍa -- 1, mēṣá -- , ēḍa -- . -- The similarity between bhēḍa -- 1, bhēḍra -- , bhēṇḍa -- ʻ ram ʼ and *bhēḍa -- 2 ʻ defective ʼ is paralleled by that between mḗḍhra -- 1, mēṇḍha -- 1 ʻ ram ʼ and *mēṇḍa -- 1, *mēṇḍha -- 2 (s.v. *miḍḍa -- ) ʻ defective ʼ](CDIAL 9606) mēṣá m. ʻ ram ʼ, °ṣīˊ -- f. ʻ ewe ʼ RV. 2. mēha -- 2, miha- m. lex. [mēha -- 2 infl. by mḗhati ʻ emits semen ʼ as poss. mēḍhra -- 2 ʻ ram ʼ (~ mēṇḍha -- 2) by mḗḍhra -- 1 ʻ penis ʼ?]1. Pk. mēsa -- m. ʻ sheep ʼ, Ash. mišalá; Kt. məṣe/l ʻ ram ʼ; Pr. məṣé ʻ ram, oorial ʼ; Kal. meṣ, meṣalák ʻ ram ʼ, H. mes m.; -- X bhēḍra -- q.v.2. K. myã̄ -- pūtu m. ʻ the young of sheep or goats ʼ; WPah.bhal. me\i f. ʻ wild goat ʼ; H. meh m. ʻ ram ʼ.mēṣāsya -- ʻ sheep -- faced ʼ Suśr. [mēṣá -- , āsyà -- ](CDIAL 10334) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Mu.) Allograph: meḍ ‘body ' (Mu.)

m1186 Composite animal hieroglyph. Text of inscription (3 lines).

m1186 Composite animal hieroglyph. Text of inscription (3 lines).Scarf is ligatured as a pigtail to a standing, horned person wishin a pot decorated with ficus leaves as a torana. Part of the glyphs included in Seal m1186.

Scarf shown ligatured as a pigtail to a horned, standing person. Tablet.

Scarf as a pigtail. A glyphic element ligatured to a horned, kneeling person in front of a horned, standing person (also with scarf as a hieroglyph) within a torana. One side of a tablet.

er-agu = a bow, an obeisance; er-aguha = bowing, coming down (Ka.lex.) er-agisu = to bow, to be bent; tomake obeisance to; to crouch; to come down; to alight (Ka.lex.) cf. arghas = respectful reception of a guest (by the offering of rice, du_rva grass, flowers or often only of water)(S’Br.14)(Skt.lex.) erugu = to bow, to salute or make obeisance (Te.) Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Ka.)erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.) eruvai ‘copper’ (Ta.); ere dark red (Ka.)(DEDR 446). er-r-a = red; (arka-) agasāle, agasāli, agasālavāḍu = a goldsmith (Te.lex.)

Thus, the horned, scarfed, kneeling person is read rebus: eraka dhatu 'copper mineral'.

Decoding 'scarf' glyph: dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu) m. ‘scarf’ (WPah.) (CDIAL 6707)Rebus: dhatu ‘minerals’ (Santali)

"Indus inscriptions resemble the Egyptian hieroglyphs..." (John Marshall, 1931, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization, London, Arthur Probsthain, p.424) Yes, indeed, Indus writing was hieroglyphic and was invented ca. 3500 BCE as the artisans gained the expertise in participating in the bronze age innovations and technologies.

The bronze age necessitated writing system as an essential complementary innovation to categorise, compile, and creat bills of lading as authenticated records of trade transactions -- by account scribes -- of artifacts produced by guilds (workshops) of artisans, miners, lapidaries, turner-carvers.

Hieroglphs on text of inscription read rebus:

Smithy (temple), Copper (mineral) guild workshop, metal furnace (account)

Sign 216 (Mahadevan). ḍato ‘claws or pincers (chelae) of crabs’; ḍaṭom, ḍiṭom to seize with the claws or pincers, as crabs, scorpions; ḍaṭkop = to pinch, nip (only of crabs) (Santali) Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral’ (Santali) Vikalpa: erā ‘claws’; Rebus: era ‘copper’. Allograph: kamaṛkom = fig leaf (Santali.lex.) kamarmaṛā (Has.), kamaṛkom (Nag.); the petiole or stalk of a leaf (Mundari.lex.) kamat.ha = fig leaf, religiosa (Skt.)

Sign 342. kaṇḍa kanka 'rim of jar' (Santali): karṇaka rim of jar’(Skt.) Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe, accountant’ (Te.); gaṇaka id. (Skt.) (Santali) copper fire-altar scribe (account)(Skt.) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) Thus, the 'rim of jar' ligatured glyph is read rebus: fire-altar (furnace) scribe (account)

Sign 229. sannī, sannhī = pincers, smith’s vice (P.) śannī f. ʻ small room in a house to keep sheep in ‘ (WPah.) Bshk. šan, Phal.šān ‘roof’ (Bshk.)(CDIAL 12326). seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. śreṇi in meaning "guild"; Vedic= row] 1. a guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). -- 2. a division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. senā and seniya). (Pali)

'body' glyph. mēd ‘body’ (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.)

aya 'fish' (Mu.); rebus: aya 'iron' (G.); ayas 'metal' (Skt.)

sal stake, spike, splinter, thorn, difficulty (H.); Rebus: sal ‘workshop’ (Santali) *ஆலை³ ālai, n. < šālā.

Varint of 'room' glyph with embedded rimless pot glyph (Sign 243 - Mahadevan corpus).

'Room' glyph. Rebus: kole.l = smithy, temple in Kota village (Ko.) kolme smithy' (Ka.) kol ‘working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.)(DEDR 2133) The ligature glyphic element within 'room' glyph (Variant Sign 243): baṭi 'broad-mouthed, rimless metal vessel'; rebus: baṭi 'smelting furnace'. Thus, the composite ligatured Sign 243 denotes: furnace smithy.

m0301

m0301 m0302

m0302 m0303

m0303 m1177

m1177 m0299

m0299 m0300

m0300 m1179 Markhor or ram with human face in composite hieroglyph

m1179 Markhor or ram with human face in composite hieroglyph m1180

m1180 h594 h594. Harappa seal. Composite animal (with elephant trunk and rings (scarves) on shoulder visible).koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.) Rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

h594 h594. Harappa seal. Composite animal (with elephant trunk and rings (scarves) on shoulder visible).koṭiyum = a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal; koṭ = neck (G.) Rebus: koḍ 'workshop' m1175 Composite animal with a two-glyph inscription (water-carrier, rebus: kuti 'furnace'; road, bata; rebus: bata 'furnace')

m1175 Composite animal with a two-glyph inscription (water-carrier, rebus: kuti 'furnace'; road, bata; rebus: bata 'furnace')

Mohenjodaro seal (m0302).

The composite animal glyph is one example to show that rebus method has to be applied to every glyphic element in the writing system.

The glyphic elements of the composite animal shown together with the glyphs of fish, fish ligatured with lid, arrow (on Seal m0302) are:

--ram or sheep (forelegs denote a bovine)

--neck-band, ring

--bos indicus (zebu)(the high horns denote a bos indicus)

--elephant (the elephant's trunk ligatured to human face)

--tiger (hind legs denote a tiger)

--serpent (tail denotes a serpent)

--human face

All these glyphic elements are decoded rebus:

meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120);

kaḍum ‘neck-band, ring’ Alternative: koṭiyum'ring' rebus: koḍ'workshop'

adar ḍangra ‘zebu’

ibha ‘elephant’ (Skt.); rebus: ib ‘iron’ (Ko.)

kolo ‘jackal’ (Kon.)

moṇḍ the tail of a serpent (Santali) Rebus: Md. moḍenī ʻ massages, mixes ʼ. Kal.rumb. moṇḍ -- ʻ to thresh ʼ, urt. maṇḍ -- ʻ to soften ʼ (CDIAL 9890) Thus, the ligature of the serpent as a tail of the composite animal glyph is decoded as: polished metal (artifact). phaḍa 'hood of cobra' rebus: फड, phaḍa 'metalwork artisan guild in charge of manufactory'

mũhe ‘face’ (Santali); mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

கோடு kōṭu : •நடுநிலை நீங்குகை. கோடிறீக் கூற் றம் (நாலடி, 5). 3. [K. kōḍu.] Tusk; யானை பன்றிகளின் தந்தம். மத்த யானையின் கோடும் (தேவா. 39, 1). 4. Horn; விலங்கின் கொம்பு. கோட்டிடை யாடினை கூத்து (திவ். இயற். திருவிருத். 21).

Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool; kuvaṭu branch of a tree; kōṭṭāṉ, kōṭṭuvāṉ rock horned-owl (cf. 1657 Ta. kuṭiñai). Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kwṛ (obl. kwṭ-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn (DEDR 2200)

meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.)

khāḍ ‘trench, firepit’

aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.) ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)

kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kol ‘alloy of five metals, pancaloha’ (Ta.)

mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)

mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali)

koḍ = the place where artisans work (G.)

Orthographically, the glytic compositions add on the characteristic short tail as a hieroglyph (on both ligatured signs and on pictorial motifs)

xolā = tail (Kur.); qoli id. (Malt.)(DEDr 2135). Rebus: kol ‘pañcalōha’ (Ta.)கொல் kol, n. 1. Iron; இரும்பு. மின் வெள்ளி பொன் கொல்லெனச் சொல்லும் (தக்கயாகப். 550). 2. Metal; உலோகம். (நாமதீப. 318.) கொல்லன் kollaṉ, n. < T. golla. Custodian of treasure; கஜானாக்காரன். (P. T. L.) கொல்லிச்சி kollicci, n. Fem. of கொல்லன். Woman of the blacksmith caste; கொல்லச் சாதிப் பெண். (யாழ். அக.) The gloss kollicci is notable. It clearly evidences that kol was a blacksmith. kola ‘blacksmith’ (Ka.); Koḍ. kollë blacksmith (DEDR 2133). Vikalpa: dumbaदुम्ब or (El.) duma दुम । पशुपुच्छः m. the tail of an animal. (Kashmiri) Rebus: ḍōmba ?Gypsy (CDIAL 5570).

Dwaraka Turbinellapyrum seal

Dwaraka Turbinellapyrum sealOn this seal, the key is only 'combination of animals'. This is an example of metonymy of a special type called synecdoche. Synecdoche, wherein a specific part of something is used to refer to the whole, or the whole to a specific part, usually is understood as a specific kind of metonymy. Three animal heads are ligatured to the body of a 'bull'; the word associated with the animal is the intended message.The ciphertext of this composite animal is to be decrypted by rendering the sounds associated with the animals in the combination: ox, young bull, antelope. The rebus readings are decrypted with metalwork categories: barad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; kondh ‘young bull’ rebus: kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker, engraver (writer)’ kundana 'fine gold'; ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'.

Seal. National Museum: 135.

The rebus readings of the hieroglyphs are: mẽḍha ‘antelope’; rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) aya 'fish'; rebus: aya 'cast metal' (G.).

Fig. 96f: Failaka no. 260

Fig. 96f: Failaka no. 260 pr̥ṣṭhá n. ʻ back, hinder part ʼ Rigveda; puṭṭhā m. ʻ buttock of an animal ʼ (Punjabi) Rebus: puṭhā, puṭṭhā m. ʻbuttock of an animal, leather cover of account bookʼ (Marathi) tagara 'antelope' Rebus: damgar 'merchant'. This may be an artistic rendering of a 'descendant' of a ancient (metals) merchant. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2012/05/antithetical-antelopes-of-ancient-near.html Antithetical antelopes of Ancient Near East as hieroglyphs (Kalyanaraman 2012) Hieroglyph: Joined back-to-back: pusht ‘back’; rebus: pusht ‘ancestor’. pus̱ẖt bah pus̱ẖt ‘generation to generation.’

One-horned heifer ligatured to an octopus. This composite glyph occurs on a seal (Mohenjodaro) and also on a copper plate (tablet)(Harappa). This glyph is decoded as: smithy guild in a citadel (enclosure), with a warehouse (granary), beṛhī

One-horned heifer ligatured to an octopus. This composite glyph occurs on a seal (Mohenjodaro) and also on a copper plate (tablet)(Harappa). This glyph is decoded as: smithy guild in a citadel (enclosure), with a warehouse (granary), beṛhīm297a: Seal h1018a: copper plate

A lexeme for a Gangetic/Indus river octopus is retained as a cultural memory only in Jatki (language of the Jats) of Punjab-Sindh region. The lexeme is veṛhā. A homonym closest to this is beṛā building with a courtyard (WPah.) There are many cognate lexemes in many languages of Bharat constituting a semantic cluster of the linguistic area (as detailed below). The rebus decoding of veṛhā (octopus); rebus: beṛā (building with a courtyard) is a reading consistent with (1) the decoding of the rest of the corpus of epigraphs as mleccha smith guild tokens; and (2) the archaeological evidence of buildings/workers’ platforms within an enclosed fortification on many sites of the civilization.

Many languages of Bharat, that is India, evolved from meluhha (mleccha) which is the lingua franca of the civilization. The language is mleccha vaacas contrasted with arya vaacas in Manusmruti (as spoken tongue contrasted with grammatically correct literary form, arya vaacas). The hypothesis on which decoding of Indus script is premised, is that lexemes of many Indian languages are evidence of the linguistic area of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization; the artefacts with the Indus script (such as metal tools/weapons, Dholavira signboard, copper plates, gold pendant, silver/copper seals/tablets etc.) are mleccha smith guild tokens -- a tradition which continues on mints issuing punch-marked coins from ca. 6th cent. BCE.

veṛhā octopus, said to be found in the Indus (Jaṭki lexicon of A. Jukes, 1900)

L. veṛh, vehṛ m. fencing; Mth. beṛhī granary; L. veṛhā, vehṛā enclosure containing many houses; beṛā building with a courtyard (WPah.) (CDIAL 12130)

koḍ = artisan’s workshop (Kuwi); koḍ ‘horn’ damṛa, koḍiyum ‘heifer’ (G.) rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’; koḍ ‘workshop’ (G.); ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.)

vēṣṭá— ‘enclosure’ lex., °aka- m. ‘fence’, Si. veṭya ‘enclosure’; — Pa. vēṭhaka— ‘surrounding’; S. veṛhu m. ‘encircling’; L. veṛh, vehṛ m. ‘fencing, enclosure in jungle with a hedge, (Ju.) blockade’, veṛhā, vehṛā m. ‘courtyard, (Ju.) enclosure containing many houses’; P. veṛhā, be° m. ‘enclosure, courtyard’; Ku. beṛo ‘circle or band (of people)’; A. ber‘wall of house, circumference of anything’; B. beṛ ‘fence, enclosure’, beṛā ‘fence, hedge’; Or. beṛha ‘fence round young trees’, beṛā ‘wall of house’; Mth. beṛ ‘hedge, wall’, beṛhī‘granary’; H. beṛh, beṛ, beṛhā, beṛā m. ‘enclosure, cattle surrounded and carried off by force’; M.veḍh m. ‘circumference’; WPah.kṭg. beṛɔ m. ‘palace’, J. beṛām. ‘id., esp. the female apartments’, kul. beṛā ‘building with a courtyard’; A. also berā ‘fence, enclosure’ (CDIAL 12130 ) वाडी [ vāḍī ] f (वाटी S) An enclosed piece of meaand keepers. dow-field or garden-ground; an enclosure, a close, a paddock, a pingle. 2 A cluster of huts of agriculturists, a hamlet. Hence (as the villages of the Konkan̤ are mostly composed of distinct clusters of houses) a distinct portion of a straggling village. 3 A division of the suburban portion of a city. वाडा [ vāḍā ] m (वाट or वाटी S) A stately or large edifice, a mansion, a palace. Also in comp. as राज- वाडा A royal edifice; सरकारवाडा Any large and public building. 2 A division of a town, a quarter, a ward. Also in comp. as देऊळवाडा,ब्राह्मण- वाडा, गौळीवाडा, चांभारवाडा, कुंभारवाडा. 3 A division (separate portion) of a मौजा or village. The वाडा, as well as the कोंड, paid revenue formerly, not to the सरकार but to the मौजेखोत. 4 An enclosed space; a yard, a compound. 5 A pen or fold; as गुरांचा वाडा, गौळवाडा or गवळीवाडा, धन- गरवाडा. The pen is whether an uncovered enclosure in a field or a hovel sheltering both beasts

It is certain that the design known as the animal file motif is extremely early in Sumerian and Elamitic glyptic; in fact is among the oldest known glyptic designs.

A characteristic style in narration is the use of a procession of animals to denote a professional group. The grouping may connote a smithy-shop of a guild --pasāramu. ![]() Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2, *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri]H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali)

Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2, *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri]H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali)

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’. Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2, *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri]H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali)

Mohenjo-daro seal m417 six heads from a core.śrēṇikā -- f. ʻ tent ʼ lex. and mngs. ʻ house ~ ladder ʼ in *śriṣṭa -- 2, *śrīḍhi -- . -- Words for ʻ ladder ʼ see śrití -- . -- √śri]H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ; Si. hiṇi, hiṇa, iṇi ʻ ladder, stairs ʼ (GS 84 < śrēṇi -- ).(CDIAL 12685). Woṭ. Šen ʻ roof ʼ, Bshk. Šan, Phal. Šān(AO xviii 251) Rebus: seṇi (f.) [Class. Sk. Śreṇi in meaning “guild”; Vedic= row] 1. A guild Vin iv.226; J i.267, 314; iv.43; Dāvs ii.124; their number was eighteen J vi.22, 427; VbhA 466. ˚ -- pamukha the head of a guild J ii.12 (text seni -- ). — 2. A division of an army J vi.583; ratha -- ˚ J vi.81, 49; seṇimokkha the chief of an army J vi.371 (cp. Senā and seniya). (Pali)This denotes a mason (artisan) guild -- seni -- of 1. brass-workers; 2. blacksmiths; 3. iron-workers; 4. copper-workers; 5. native metal workers; 6. workers in alloys.

The core is a glyphic ‘chain’ or ‘ladder’. Glyph: kaḍī a chain; a hook; a link (G.); kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason; kaḍiyaṇa, kaḍiyeṇa a woman of the bricklayer caste; a wife of a bricklayer (G.)

The glyphics are:

1. Glyph: ‘one-horned young bull’: kondh ‘heifer’. kũdār ‘turner, brass-worker’.

2. Glyph: ‘bull’: ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

3. Glyph: ‘ram’: meḍh ‘ram’. Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’

4. Glyph: ‘antelope’: mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’. Vikalpa 1: meluhha ‘mleccha’ ‘copper worker’. Vikalpa 2: meṛh ‘helper of merchant’.

5. Glyph: ‘zebu’: khũṭ ‘zebu’. Rebus: khũṭ ‘guild, community’ (Semantic determinant of the ‘jointed animals’ glyphic composition). kūṭa joining, connexion, assembly, crowd, fellowship (DEDR 1882) Pa. gotta ‘clan’; Pk. gotta, gōya id. (CDIAL 4279) Semantics of Pkt. lexeme gōya is concordant with Hebrew ‘goy’ in ha-goy-im (lit. the-nation-s). Pa. gotta -- n. ʻ clan ʼ, Pk. gotta -- , gutta -- , amg. gōya -- n.; Gau. gū ʻ house ʼ (in Kaf. and Dard. several other words for ʻ cowpen ʼ > ʻ house ʼ: gōṣṭhá -- , Pr. gūˊṭu ʻ cow ʼ; S. g̠oṭru m. ʻ parentage ʼ, L. got f. ʻ clan ʼ, P. gotar, got f.; Ku. N. got ʻ family ʼ; A. got -- nāti ʻ relatives ʼ; B. got ʻ clan ʼ; Or. gota ʻ family, relative ʼ; Bhoj. H. got m. ʻ family, clan ʼ, G. got n.; M. got ʻ clan, relatives ʼ; -- Si. gota ʻ clan, family ʼ ← Pa. (CDIAL 4279). Alternative: adar ḍangra ‘zebu or humped bull’; rebus: aduru ‘native metal’ (Ka.); ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ (H.)

6. The sixth animal can only be guessed. Perhaps, a tiger (A reasonable inference, because the glyph ’tiger’ appears in a procession on some Indus script inscriptions. Glyph: ‘tiger?’: kol ‘tiger’.Rebus: kol ’worker in iron’. Vikalpa (alternative): perhaps, rhinoceros. gaṇḍa ‘rhinoceros’; rebus:khaṇḍ ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’. Thus, the entire glyphic composition of six animals on the Mohenjodaro seal m417 is semantically a representation of a śrḗṇi, ’guild’, a khũṭ , ‘community’ of smiths and masons.

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

A cylinder seal showing hieroglyphs of crocodile, elephant and rhinoceros was found in Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. This is an example of Meluhha writing using hieroglyphs to denote the competence of kāru ‘artisan’ -- kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri); kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) He was also ibbo 'merchant' (Hieroglyph: ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron') and maker of metal artifacts: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’ (kāṇḍā mṛga 'rhinoceros' (Tamil).

Tell AsmarCylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron'. kāṇḍā 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. karā 'crocodile' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Tell AsmarCylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron'. kāṇḍā 'rhinoceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. karā 'crocodile' Rebus: khar 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Glazed steatite . Cylinder seal. 3.4cm high; imported from Indus valley. Rhinoceros, elephant, crocodile (lizard? ).Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. IM 14674; Frankfort, 1955, No. 642; Collon, 1987, Fig. 610. ibha‘elephant’Rebus: ibbo ‘merchant’, ib ‘iron’காண்டாமிருகம் kāṇṭā-mirukam , n. [M. kāṇṭāmṛgam.] Rhinoceros; கல்யானை. Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’.kāru ‘crocodile’ Rebus: kāru ‘artisan’. Alternative: araṇe ‘lizard’ Rebus: airaṇ ‘anvil’.

kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Te.) కారు mosale ‘wild crocodile or alligator. S. ghaṛyālu m. ʻ long — snouted porpoise ʼ; N. ghaṛiyāl ʻ crocodile’ (Telugu)ʼ; A. B. ghãṛiyāl ʻ alligator ʼ, Or. Ghaṛiāḷa, H. ghaṛyāl, ghariār m. (CDIAL 4422) கரவு² karavu, n. < கரா. Cf. grāha. Alligator; முதலை. கரவார்தடம் (திவ். திருவாய். 8, 9, 9). கரா karā, n. prob. Grāha. 1. A species of alligator; முதலை. கராவதன் காலினைக்கதுவ (திவ். பெரியதி. 2, 3, 9). 2. Male alligator; ஆண்முதலை. (பிங்.) கராம் karām n. prob. Grāha. 1. A species of alligator ; முதலைவகை. முதலையு மிடங்கருங் கராமும் (குறிஞ்சிப். 257). 2. Male alligator; ஆண் முதலை. (திவா.)

karuvu n. Melting: what is melted (Te.)कारु [ kāru ] m (S) An artificer or artisan. 2 A common term for the twelve बलुतेदार q. v. Also कारुनारु m pl q. v. in नारुकारु. (Marathi) कारिगर, कारिगार, कारागीर, कारेगार, कारागार [ kārigara, kārigāra, kārāgīra, kārēgāra, kārāgāra ] m ( P) A good workman, a clever artificer or artisan. 2 Affixed as an honorary designation to the names of Barbers, and sometimes of सुतार, गवंडी, & चितारी. 3 Used laxly as adj and in the sense of Effectual, availing, effective of the end. बलुतें [ balutēṃ ] n A share of the corn and garden-produce assigned for the subsistence of the twelve public servants of a village, for whom see below. 2 In some districts. A share of the dues of the hereditary officers of a village, such as पाटील, कुळकरणी &c. बलुतेदार or बलुता [ balutēdāra or balutā ] or त्या m (बलुतें &c.) A public servant of a village entitled to बलुतें. There are twelve distinct from the regular Governmentofficers पाटील, कुळकरणी &c.; viz. सुतार, लोहार, महार, मांग (These four constitute पहिली or थोरली कास or वळ the first division. Of three of them each is entitled to चार पाचुंदे, twenty bundles of Holcus or the thrashed corn, and the महार to आठ पाचुंदे); कुंभार, चाम्हार, परीट, न्हावी constitute दुसरी orमधली कास or वळ, and are entitled, each, to तीन पाचुंदे; भट, मुलाणा, गुरव, कोळी form तिसरी or धाकटी कास or वळ, and have, each, दोन पाचुंदे. Likewise there are twelve अलुते or supernumerary public claimants, viz. तेली, तांबोळी, साळी, माळी, जंगम, कळवांत, डवऱ्या, ठाकर, घडशी, तराळ, सोनार, चौगुला. Of these the allowance of corn is not settled. The learner must be prepared to meet with other enumerations of the बलुतेदार (e. g. पाटील, कुळ- करणी, चौधरी, पोतदार, देशपांड्या, न्हावी, परीट, गुरव, सुतार, कुंभार, वेसकर, जोशी; also सुतार, लोहार, चाम्हार, कुंभार as constituting the first-class and claiming the largest division of बलुतें; next न्हावी, परीट, कोळी, गुरव as constituting the middle class and claiming a subdivision of बलुतें; lastly, भट, मुलाणा, सोनार, मांग; and, in the Konkan̤, yet another list); and with other accounts of the assignments of corn; for this and many similar matters, originally determined diversely, have undergone the usual influence of time, place, and ignorance. Of the बलुतेदार in the Indápúr pergunnah the list and description stands thus:--First class, सुतार, लोहार, चाम्हार, महार; Second, परीट, कुंभार, न्हावी, मांग; Third, सोनार, मुलाणा, गुरव, जोशी, कोळी, रामोशी; in all fourteen, but in no one village are the whole fourteen to be found or traced. In the Panḍharpúr districts the order is:--पहिली or थोरली वळ (1st class); महार, सुतार, लोहार, चाम्हार, दुसरी or मधली वळ(2nd class); परीट, कुंभार, न्हावी, मांग, तिसरी or धाकटी वळ (3rd class); कुळकरणी, जोशी, गुरव, पोतदार; twelve बलुते and of अलुते there are eighteen. According to Grant Duff, the बलतेदार are सुतार, लोहार, चाम्हार, मांग, कुंभार, न्हावी, परीट, गुरव, जोशी, भाट, मुलाणा; and the अलुते are सोनार, जंगम, शिंपी, कोळी, तराळ or वेसकर, माळी, डवऱ्यागोसावी, घडशी, रामोशी, तेली, तांबोळी, गोंधळी. In many villages of Northern Dakhan̤ the महार receives the बलुतें of the first, second, and third classes; and, consequently, besides the महार, there are but nine बलुतेदार. The following are the only अलुतेदार or नारू now to be found;--सोनार, मांग, शिंपी, भट गोंधळी, कोर- गू, कोतवाल, तराळ, but of the अलुतेदार & बलुते- दार there is much confused intermixture, the अलुतेदार of one district being the बलुतेदार of another, and vice lls. (The word कास used above, in पहिली कास, मध्यम कास, तिसरी कास requires explanation. It means Udder; and, as the बलुतेदार are, in the phraseology of endearment or fondling, termed वासरें (calves), their allotments or divisions are figured by successive bodies of calves drawing at the कास or under of the गांव under the figure of a गाय or cow.) (Marathi)kruciji ‘smith’ (Old Church Slavic)

Crocodile hieroglyph in combination with other animal hieroglphs also appears on a Mohenjo-daro seal m0489 in the context of an erotic Meluhha hieroglyph: a tergo copulation hieroglyph

m0489a,b,c Mohenjo-daro prism tablet

A standing human couple mating (a tergo); one side of a prism tablet from Mohenjo-daro (m489b). Other motifs on the inscribed object are: two goats eating leaves on a platform; a cock or hen (?) and a three-headed animal (perhaps antelope, one-horned bull and a short-horned bull). The leaf pictorial connotes on the goat composition connotes loa; hence, the reading is of this pictorial component is: lohar kamar = a blacksmith, worker in iron, superior to the ordinary kamar (Santali.)]

kāruvu ‘crocodile’ Rebus: ‘artisan, blacksmith’. pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Telugu) Thus, the depiction of animals in epigraphs is related to, rebus: pasra = smithy (Santali)

pisera_ a small deer brown above and black below (H.)(CDIAL 8365).

ḍān:gra = wooden trough or manger sufficient to feed one animal (Mundari). iṭan:kārri = a capacity measure (Ma.) Rebus: ḍhan:gar ‘blacksmith’ (Bi.)

ḍān:gra = wooden trough or manger sufficient to feed one animal (Mundari). iṭan:kārri = a capacity measure (Ma.) Rebus: ḍhan:gar ‘blacksmith’ (Bi.)

pattar ‘goldsmiths’ (Ta.) patra ‘leaf’ (Skt.)

r-an:ku, ran:ku = fornication, adultery (Telugu); rebus: ranku ‘tin’ (Santali)

Rebus readings of Meluhha hieroglyphs:

Hieroglhyphs: elephant (ibha), boar/rhinoceros[kāṇḍā mṛga 'rhinoceros' (Tamil)], tiger (kol), tiger face turned (krammara), young bull calf (khōṇḍa) [खोंड m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi)], antelope, ḍangur ʻbullockʼ, melh ‘goat’ (Brahui)

Rebus mleccha glosses: Ib 'iron' ibbo 'merchant'; kāṇḍā, 'tools, pots and pans, metalware'; kol 'worker in iron, smithy'; krammara, kamar 'smith, artisan', kõdā 'lathe-turner' [B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or. kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ‘lathe’) (CDIAL 3295)], khũṭ ‘guild, community’, ḍāṅro ’blacksmith’ (Nepalese) milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) [Meluhha!]

Iron (ib), carpenter (badhi), smithy (kol ‘pancaloha’), alloy-smith (kol kamar)

tam(b)ra copper, milakkhu copper, bali (iron sand ore), native metal (aduru), ḍhangar ‘smith’.

Smithy with an armourer

http://www.harappa.com/indus/32.html Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Terracotta sealing from Mohenjo-daro depicting a collection of animals and some script symbols. In the centre is a horned crocodile (gharial) surrounded by other animals including a monkey.

In these seals of Mohenjo-daro ‘horned crocodile’ hieroglyph is the center-piece surrounded by hieroglyphs of a pair of bullocks, elephant, rhinoceros, tiger looking back and a monkey-like creature.

Obverse of m1395 and m0441 had the following images of a multi-headed tiger.

Ta. kōṭaram monkey. Ir. kōḍa (small) monkey; kūḍag monkey. Ko. ko·ṛṇ small monkey. To. kwṛṇ monkey. Ka. kōḍaga monkey, ape. Koḍ. ko·ḍë monkey. Tu. koḍañji, koḍañja, koḍaṅgů baboon. (DEDR 2196). kuṭhāru = a monkey (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker), also an inscriber or writer.

Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn; Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr horn Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-)( (DEDR 2200) Paš. kōṇḍā ‘bald’, Kal. rumb. kōṇḍa ‘hornless’.(CDIAL 3508). Kal. rumb. khōṇḍ a ‘half’ (CDIAL 3792).

Rebus: koḍ 'workshop' (Gujarati) Thus, a horned crocodile is read rebus: koḍ khar 'blacksmith workshop'. khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) kāruvu ‘crocodile’ Rebus: ‘artisan, blacksmith’.

Hieroglyph: Joined animals (tigers): sangaḍi = joined animals (M.) Rebus: sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ (Lahnda)(CDIAL 12845) sang संग् m. a stone (Kashmiri) sanghāḍo (G.) = cutting stone, gilding; sangatarāśū = stone cutter; sangatarāśi = stone-cutting; sangsāru karan.u = to stone (S.), cankatam = to scrape (Ta.), sankaḍa (Tu.), sankaṭam = to scrape (Skt.) kol 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Thus, the multi-headed tiger is read rebus: kol sangaḍi 'fortified place for metal (& ore stone) workers'.

The following glyphics of m1431 prism tablet show the association between the tiger + person on tree glyphic set and crocile + 3 animal glyphic set.

Mohenjo-daro m1431 four-sided tablet. Row of animals in file (a one-horned bull, an elephant and a rhinoceros from right); a gharial with a fish held in its jaw above the animals; a bird (?) at right. Pict-116: From R.—a person holding a vessel; a woman with a platter (?); a kneeling person with a staff in his hands facing the woman; a goat with its forelegs on a platform under a tree. [Or, two antelopes flanking a tree on a platform, with one antelope looking backwards?]

One side (m1431B) of a four-sided tablet shows a procession of a tiger, an elephant and a rhinoceros (with fishes (or perhaps, crocodile) on top?).

koḍe ‘young bull’ (Telugu) खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf. Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (B.)कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali)[fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Te.)] baṭṭai quail (N.Santali) Rebus: bhaṭa = an oven, kiln, furnace (Santali)

ayo 'fish' Rebus: ayas 'metal'. kaṇḍa 'arrow' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. ayaskāṇḍa is a compounde word attested in Panini. The compound or glyphs of fish + arrow may denote metalware tools, pots and pans.kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron, alloy of 5 metals - pancaloha'. ibha 'elephant' Rebus ibbo 'merchant'; ib ‘iron'. Alternative: కరటి [ karaṭi ] karaṭi. [Skt.] n. An elephant. ఏనుగు (Telugu) Rebus: kharādī ‘ turner’ (Gujarati) kāṇḍa 'rhimpceros' Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’. The text on m0489 tablet: loa 'ficus religiosa' Rebus: loh 'copper'. kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. Thus the display of the metalware catalog includes the technological competence to work with minerals, metals and alloys and produce tools, pots and pans. The persons involved are krammara 'turn back' Rebus: kamar 'smiths, artisans'. kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron, working in pancaloha alloys'. పంచలోహము pancha-lōnamu. n. A mixed metal, composed of five ingredients, viz., copper, zinc, tin, lead, and iron (Telugu). Thus, when five svastika hieroglyphs are depicted, the depiction is of satthiya 'svastika' Rebus: satthiya 'zinc' and the totality of 5 alloying metals of copper, zinc, tin, lead and iron.

Glyph: Animals in procession: खांडा [khāṇḍā] A flock (of sheep or goats) (Marathi) கண்டி¹ kaṇṭi Flock, herd (Tamil) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’.

m0489A One side of a prism tablet shows: crocodile + fish glyphic on the top register. Glyphs: crocodile + fish Rebus: ayakāra ‘blacksmith’ (Pali)

Glyph: Animals in procession: खांडा [khāṇḍā] A flock (of sheep or goats) (Marathi) கண்டி¹ kaṇṭi Flock, herd (Tamil) Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, and metal-ware’.

It is possible that the broken portions of set 2 (h1973B and h1974B) showed three animals in procession: tiger looking back and up + rhinoceros + tiger.

Reverse side glyphs:

eraka ‘nave of wheel’. Rebus: era ‘copper’. āra 'spokes' Rebus: āra 'brass'.

Animal glyph: elephant ‘ibha’. Rebus ibbo, ‘merchant’ (Gujarati).

Composition of glyphics: Woman with six locks of hair + one eye + thwarting + two pouncing tigers (jackals)+ nave with six spokes. Rebus: kola ‘woman’ + kaṇga ‘eye’ (Pego.), bhaṭa ‘six’+ dul‘casting (metal)’ + kũdā kol (tiger jumping) or lo ‘fox’ (WPah.) rebus: lōha ʻmetalʼ (Pali) + era āra (nave of wheel, six spokes), ibha (elephant). Rebus: era ‘copper’; kũdār dul kol ‘turner, casting, working in iron’;kan ‘brazier, bell-metal worker’; ibbo ‘merchant’.

The glyphic composition read rebus: copper, iron merchant with taṭu kanḍ kol bhaṭa ‘iron stone (ore) mineral ‘furnace’.

lōpāka m. ʻa kind of jackalʼ Suśr., lōpākikā -- f. lex. 1. H. lowā m. ʻfoxʼ.2. Ash. ẓōki, žōkī ʻfoxʼ, Kt. ŕwēki, Bashg. wrikī, Kal.rumb. lawák: < *raupākya -- NTS ii 228; -- Dm. rɔ̈̄pak ← Ir.? lōpāśá m. ʻfox, jackalʼ RV., lōpāśikā -- f. lex. [Cf. lōpāka -- . -- *lōpi -- ] Wg. liwášä, laúša ʻfoxʼ, Paš.kch. lowóċ, ar. lṓeč ʻjackalʼ (→ Shum. lṓeč NTS xiii 269), kuṛ. lwāinč; K. lośu, lōh, lohu, lôhu ʻporcupine, foxʼ.1. Kho. lōw ʻfoxʼ, Sh.gil. lótilde;i f., pales. lṓi f., lṓo m., WPah.bhal. lōī f., lo m.2. Pr. ẓūwī ʻfoxʼ.(CDIAL 11140-2).Rebus:lōhá ʻred, copper -- colouredʼ ŚrS., ʻmade of copperʼ ŚBr., m.n. ʻcopperʼ VS., ʻironʼ MBh. [*rudh -- ] Pa. lōha -- m. ʻmetal, esp. copper or bronzeʼ; Pk. lōha -- m. ʻironʼ, Gy. pal. li°, lihi, obl. elhás, as. loa JGLS new ser. ii 258; Wg. (Lumsden) "loa"ʻsteelʼ; Kho. loh ʻcopperʼ; S. lohu m. ʻironʼ, L. lohā m., awāṇ. lōˋā, P. lohā m. (→ K.rām. ḍoḍ. lohā), WPah.bhad. lɔ̃u n., bhal. lòtilde; n., pāḍ. jaun. lōh, paṅ. luhā, cur. cam. lohā, Ku. luwā, N. lohu, °hā, A. lo, B. lo, no, Or. lohā, luhā, Mth. loh, Bhoj. lohā, Aw.lakh. lōh, H. loh, lohā m., G. M. loh n.; Si. loho, lō ʻ metal, ore, iron ʼ; Md. ratu -- lō ʻ copper lōhá -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) lóɔ ʻironʼ, J. lohā m., Garh. loho; Md. lō ʻmetalʼ. (CDIAL 11158).

Glyph: ‘woman’: kola ‘woman’ (Nahali). Rebus kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

Glyph: ‘impeding, hindering’: taṭu (Ta.) Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral’ (Santali) Ta. taṭu (-pp-, -tt) to hinder, stop, obstruct, forbid, prohibit, resist, dam, block up, partition off, curb, check, restrain, control, ward off, avert; n. hindering, checking, resisting; taṭuppu hindering, obstructing, resisting, restraint; Kur. ṭaṇḍnā to prevent, hinder, impede. Br. taḍ power to resist. (DEDR 3031)

Allograph: ‘notch’: Marathi: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon).

Glyph: ‘full stretch of one’s arms’: kāḍ 2 काड् । पौरुषम् m. a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length) (Rām. 632, zangan kaḍun kāḍ, to stretch oneself the whole length of one's body. So K. 119). Rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’. Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298). mayponḍi kanḍ whetstone; (Ga.)(DEDR 4628). (खडा) Pebbles or small stones: also stones broken up (as for a road), metal. खडा [ khaḍā ] m A small stone, a pebble. 2 A nodule (of lime &c.): a lump or bit (as of gum, assafœtida, catechu, sugar-candy): the gem or stone of a ring or trinket: a lump of hardened fæces or scybala: a nodule or lump gen. CDIAL 3018 kāṭha m. ʻ rock ʼ lex. [Cf. kānta -- 2 m. ʻ stone ʼ lex.] Bshk. kōr ʻ large stone ʼ AO xviii 239. கண்டு³ kaṇṭu , n. < gaṇḍa. 1. Clod, lump; கட்டி. (தைலவ. தைல.99.) 2. Wen; கழலைக்கட்டி. 3. Bead or something like a pendant in an ornament for the neck; ஓர் ஆபரணவுரு. புல்லிகைக்கண்ட நாண் ஒன்றிற் கட்டின கண்டு ஒன்றும் (S.I.I. ii, 429). (CDIAL 3023) kāṇḍa cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion with gaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. joint of stalk, lump. काठः A rock, stone. kāṭha m. ʻ rock ʼ lex. [Cf. kānta -- 2 m. ʻ stone ʼ lex.]Bshk. kōr ʻ large stone ʼ AO xviii 239.(CDIAL 3018). অয়সঠন [ aẏaskaṭhina ] as hard as iron; extremely hard (Bengali)

Glyph: ‘one-eyed’: काण a. [कण् निमीलने कर्तरि घञ् Tv.] 1 One-eyed; अक्ष्णा काणः Sk; काणेन चक्षुषा किं वा H. Pr.12; Ms.3.155. -2 Perforated, broken (as a cowrie) <kaNa>(Z) {ADJ} ``^one-^eyed, ^blind''. Ju<kaNa>(DP),,<kana>(K) {ADJ} ``^blind, blind in one eye''. (Munda) Go. (Ma.) kanḍ reppa eyebrow (Voc. 3047(a))(DEDR 5169). Ka. kāṇ (kaṇḍ-) to see; Ko. kaṇ-/ka·ṇ- (kaḍ-) to see; Koḍ. ka·ṇ- (ka·mb-, kaṇḍ-) to see; Ta. kāṇ (kāṇp-, kaṇṭ-) to see; Kol.kanḍt, kanḍakt seen, visible. (DEDR 1443). Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. (DEDR 1159a) Rebus ‘brazier, bell-metal worker’: கன்னான் kaṉṉāṉ , n. < கன்¹. [M. kannān.] Brazier, bell-metal worker, one of the divisions of the Kammāḷa caste; செம்புகொட்டி. (திவா.) Ta. kaṉ copper work, copper, workmanship; kaṉṉāṉ brazier. Ma. kannān id. (DEDR 1402). கன்¹ kaṉ , n. perh. கன்மம். 1. Workmanship; வேலைப்பாடு. கன்னார் மதில்சூழ் குடந்தை (திவ். திருவாய். 5, 8, 3). 2. Copper work; கன்னார் தொழில். (W.) 3. Copper; செம்பு. (ஈடு, 5, 8, 3.) 4. See கன்னத்தட்டு. (நன். 217, விருத்.) கன்² kaṉ , n. < கல். 1. Stone; கல். (சூடா.) 2. Firmness; உறுதிப்பாடு. (ஈடு, 5, 8, 3.)

kã̄ḍ 2 काँड् m. a section, part in general; a cluster, bundle, multitude (Śiv. 32). kã̄ḍ 1 काँड् । काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed, grass, or the like, straw. In the compound with dan 5 (p. 221a, l. 13) the word is spelt kāḍ.

kō̃da कोँद । कुलालादिकन्दुः f. a kiln; a potter's kiln (Rām. 1446; H. xi, 11); a brick-kiln (Śiv. 133); a lime-kiln. -bal -बल् । कुलालादिकन्दुस्थानम् m. the place where a kiln is erected, a brick or potter's kiln (Gr.Gr. 165). -- । कुलालादिकन्दुयथावद्भावः f.inf. a kiln to arise; met. to become like such a kiln (which contains no imperfectly baked articles, but only well-made perfectly baked ones), hence, a collection of good ('pucka') articles or qualities to exist.

kāru ‘crocodile’ (Telugu). Rebus: artisan (Marathi) Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) kola ‘tiger’ Rebus: kol ‘working in iron’. Heraka ‘spy’ Rebus: eraka ‘copper’. khōṇḍa ‘leafless tree’ (Marathi). Rebus: kõdār’turner’ (Bengali)

Looking back: krammara ‘look back’ Rebus: kamar ‘smith, artisan’.

One side of a triangular terracotta tablet (Md 013); surface find at Mohenjo-daro in 1936. Dept. of Eastern Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Hieroglyph: kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakrit) kamaḍha, kamaṭha, kamaḍhaka, kamaḍhaga, kamaḍhaya = a type of penance (Prakrit)

Rebus: kamaṭamu, kammaṭamu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammaṭīḍu = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Telugu) kãpṛauṭ jeweller's crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Tamil)

kamaṭhāyo = a learned carpenter or mason, working on scientific principles; kamaṭhāṇa [cf. karma, kām, business + sthāna, thāṇam, a place fr. Skt. sthā to stand] arrangement of one’s business; putting into order or managing one’s business (Gujarati)

The composition of two hieroglyphs: kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) + kamaḍha 'a person seated in penance' (Prakrit) denote rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri); kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) + kamaṭa 'portable furnace'; kampaṭṭam 'coinage, coin, mint'. Thus, what the tablet conveys is the mint of a blacksmith. A copulating crocodile hieroglyph -- kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) + kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) -- conveys the same message: mint of a blacksmith kāru kampaṭṭa 'mint artisan'.

m1429B and two other tablets showing the typical composite hieroglyph of fish + crocodile. Glyphs: crocodile + fish ayakāra ‘blacksmith’ (Pali) kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) aya 'fish' (Munda) The method of ligaturing enables creation of compound messages through Indus writing inscriptions. kārua wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri); kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi).

Kashmiri glosses:

Pali: ayakāra ‘iron-smith’. ] Both ayaskāma and ayaskāra are attested in Panini (Pan. viii.3.46; ii.4.10). WPah. bhal. kamīṇ m.f. labourer (man or woman) ; MB. kāmiṇā labourer (CDIAL 2902) N. kāmi blacksmith (CDIAL 2900).

Kashmiri glosses:

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17).

khāra-basta khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji or -güjü - लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu - लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 - लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wānवान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil.

khāra-basta khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji or -güjü - लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu - लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 - लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wānवान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil.

Thus, kharvaṭ may refer to an anvil. Meluhha kāru may refer to a crocodile; this rebus reading of the hieroglyph is.consistent with ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali) [fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Telugu)]

Hieroglyph: mlekh 'goat' Rebus: milakkhu 'copper' mleccha 'copper'; ayo 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron'; ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

loa, ficus (Santali); loh ‘metal’ (Samskritam)

kol 'tiger' Rebus: kolhe 'smelters'; kol 'working in iron'

eraka 'wing' Rebus: eraka 'copper'

ayo 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

Indus inscription on a Mohenjo-daro tablet (m1405) including ‘rim-of-jar’ glyph as component of a ligatured glyph (Sign 15 Mahadevan)This tablet is a clear and unambiguous example of the fundamental orthographic style of Indus Script inscriptions that: both signs and pictorial motifs are integral components of the message conveyed by the inscriptions. Attempts at ‘deciphering’ only what is called a ‘sign’ in Parpola or Mahadevan corpuses will result in an incomplete decoding of the complete message of the inscribed object.

This inscribed object is decoded as a professional calling card: a blacksmith-precious-stone-merchant with the professional role of copper-miner-smelter-furnace-scribe.

m1405At Pict-97: Person standing at the center points with his right hand at a bison facing a trough, and with his left hand points to the ligatured glyph.

The inscription on the tablet juxtaposes – through the hand gestures of a person - a ‘trough’ gestured with the right hand; a ligatured glyph composed of ‘rim-of-jar’ glyph and ‘water-carrier’ glyph (Glyph 15) gestured with the left hand.

Water-carrier glyph kuṭi ‘water-carrier’ (Telugu); Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) kuṭi ‘hut made of boughs’ (Skt.) guḍi temple (Telugu) [The bull is shown in front of the trough for drinking; hence the semantics of ‘drinking’.]

The most frequently occurring glyph -- rim of jar -- ligatured to Glyph 12 becomes Glyph 15 and is thus explained as a kanka, karṇaka: ‘furnace scribe’ and is consistent with the readings of glyphs which occur together with this glyph. Kan-ka may denote an artisan working with copper, kaṉ (Ta.) kaṉṉār ‘coppersmiths, blacksmiths’ (Ta.) Thus, the phrase kaṇḍ karṇaka may be decoded rebus as a brassworker, scribe. karṇaka ‘scribe, accountant’.

The inscription of this tablet is composed of four glyphs: bison, trough, shoulder (person), ligatured glyph -- Glyph 15(rim-of-jar glyph ligatured to water-carrier glyph).

Each glyph can be read rebus in mleccha (meluhhan).